Abstract

SAMHD1 is a human restriction factor that prevents efficient infection of macrophages, dendritic cells and resting CD4+ T cells by HIV-1. Here we explored the antiviral activity and biochemical properties of human SAMHD1 polymorphisms. Our studies focused on human SAMHD1 polymorphisms that were previously identified as evolving under positive selection for rapid amino acid replacement during primate speciation. The different human SAMHD1 polymorphisms were tested for their ability to block HIV-1, HIV-2 and equine infectious anemia virus (EIAV). All studied SAMHD1 variants block HIV-1, HIV-2 and EIAV infection when compared to wild type. We found that these variants did not lose their ability to oligomerize or to bind RNA. Furthermore, all tested variants were susceptible to degradation by Vpx, and localized to the nuclear compartment. We tested the ability of human SAMHD1 polymorphisms to decrease the dNTP cellular levels. In agreement, none of the different SAMHD1 variants lost their ability to reduce cellular levels of dNTPs. Finally, we found that none of the tested human SAMHD1 polymorphisms affected the ability of the protein to block LINE-1 retrotransposition.

Keywords: SAMHD1, SNPs, HIV-1, Vpx, dNTPs, LINE-1

INTRODUCTION

Efficient infection of human primary macrophages, dendritic cells and resting CD4+ T-cells by simian immunodeficiency virus (SIVmac) requires the accessory protein Vpx (Arfi et al., 2008; Baldauf et al., 2012; Descours et al., 2012; Goujon et al., 2008; Goujon et al., 2003; Goujon et al., 2007; Spragg and Emerman, 2013). Vpx is essential for both SIV infection of primary macrophages and viral pathogenesis in vivo (Belshan et al., 2006; Fletcher et al., 1996; Gibbs et al., 1995; Hirsch et al., 1998). Vpx is incorporated into viral particles suggesting that it might be acting immediately after viral fusion (Jin et al., 2001; Kappes et al., 1993; Park and Sodroski, 1995; Selig et al., 1999; Yu et al., 1988). Viral reverse transcription is prevented in primary macrophages when cells are infected with either Vpx-deficient SIVmac or HIV-2 (Bergamaschi et al., 2009; Fujita et al., 2008; Goujon et al., 2007; Kaushik et al., 2009; Srivastava et al., 2008). Interestingly, Vpx also increases the ability of HIV-1 to efficiently infect macrophages, dendritic cells and resting CD4+ T cells when Vpx is incorporated into HIV-1 particles or supplied in trans (Baldauf et al., 2012; Descours et al., 2012; Goujon et al., 2008; Sunseri et al., 2011; Yu et al., 1991). Recent work identified SAMHD1 as the protein that blocks infection of SIVΔVpx, HIV-2ΔVpx and HIV-1 before reverse transcription in macrophages, dendritic cells and resting CD4+ T cells (Baldauf et al., 2012; Berger et al., 2011; Descours et al., 2012; Hrecka et al., 2011; Laguette et al., 2011). Mechanistic studies have suggested that Vpx induces the proteasomal degradation of SAMHD1 (Berger et al., 2011; Hrecka et al., 2011; Laguette et al., 2011). In agreement, the C-terminal region of SAMHD1 contains a Vpx binding motif, which is important for the ability of Vpx to degrade SAMHD1 (Ahn et al., 2012; Fregoso et al., 2013; Laguette et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2012). Some Vpx proteins target the N-terminal region of SAMHD1 suggesting more than one mechanism for degradation (Fregoso et al., 2013; Wei et al., 2014). SAMHD1 is a dGTP-regulated deoxynucleotide triphosphohydrolase (dNTPs) that decreases the overall cellular levels of dNTPs (Goldstone et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2012; Lahouassa et al., 2012; Powell et al., 2011).

SAMHD1 is comprised of the sterile alpha motif (SAM) and histidine-aspartic (HD) domains. The HD domain of SAMHD1 is a dGTP-regulated deoxynucleotide triphosphohydrolase that decreases the cellular levels of dNTPs (Goldstone et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2012; Lahouassa et al., 2012; Powell et al., 2011). The sole HD domain is sufficient to potently restrict infection by different viruses (White et al., 2013a). The HD domain is also necessary for the ability of SAMHD1 to oligomerize and to bind RNA (White et al., 2013a). The decrease in dNTP levels in myeloid cells correlates with the inability of lentiviruses to undergo reverse transcription.

Recent findings have suggested that the antiviral activity of SAMHD1 is regulated by phosphorylation (Cribier et al., 2013; Welbourn et al., 2013; White et al., 2013b). Interestingly, an antivirally active SAMHD1 is unphosphorylated on T592. By contrast, SAMHD1 phosphorylated on T592 is antivirally inactive. These findings showed that contrary to what happen in cycling cells, SAMHD1 is unphosphorylated in non-cycling cells. These results proposed an explanation for the reason that SAMHD1 is expressed in cycling and non-cycling cells, but it only exhibits antiviral activity in non-cycling cells.

The human population contains several SAMHD1 polymorphisms; however, the ability of human SAMHD1 polymorphisms to block HIV-1 infection is not known. Here we investigated the ability of the different human SAMHD1 polymorphisms for their ability to block HIV-1 and equine infectious anemia virus (EIAV) infection. Furthermore, we tested the different human SAMHD1 polymorphisms for oligomerization, RNA binding, Vpx-mediated degradation, subcellular localization, and ability to decrease the cellular levels of dNTPs.

RESULTS

Identification of human SAMHD1 polymorphisms

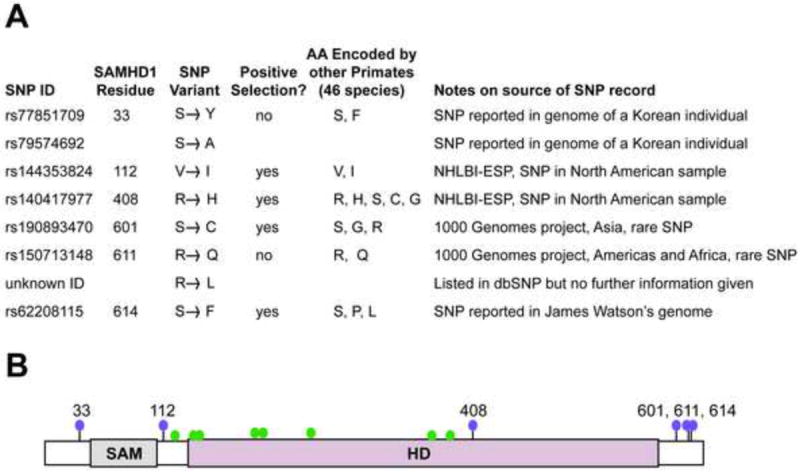

We wished to functionally assess the impact of SAMHD1 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) circulating in the human population. As of June 2012, there were non-synonymous SNPs reported in 26 codon positions in SAMHD1. From these, we focused on SNPs reported at three codon positions (408, 601, 614) that were previously identified as evolving under positive selection for rapid amino acid replacement during primate speciation (Fig. 1A) (Laguette et al., 2012; Lim et al., 2012). We also focused on SNPs at two codons (33, 611) where more than one human SNP has been reported in the same codon (Fig. 1A). SNPs in codons under positive selection, and in codons where multiple SNPs are co-circulating, have previously been found to be functionally relevant in restriction factor genes (Johnson and Sawyer, 2009; Meyerson and Sawyer, 2011). This is presumably because both patterns might arise if selection is acting to retain new variants that arise in populations. We also aligned SAMHD1 protein sequences from 46 non-human primate species, and list the alternate amino acids encoded at each of these positions in different primate species (Fig. 1A). The human SNPs observed at sites 112, 408, and 611 re-sample amino acids encoded by other primate species, another pattern that has been observed at positions of functional significance in restriction factors (Meyerson and Sawyer, 2011)

Figure 1. Human SAMHD1 SNPs tested in this study.

(A) The tested SNPs are listed. Some of these SNPs (408, 601, 614) fall in codons that have previously been identified as evolving under positive selection for rapid amino acid change during primate speciation (Laguette et al., 2012; Lim et al., 2012). Two codon positions (33 and 611) each bear two unique SNPs reported in the human population. The two SNPs at position 33 are different in that one is a nucleotide change affecting the first position of the codon, and the other is a change affecting the second position of the codon. In the case of 611, both SNPs are reported to affect the second position of the codon, although validation is uncertain for one of these SNPs (R611L). An alignment of SAMHD1 protein sequences from 46 non-human primate species was used to determine the amino acids encoded at these positions by non-human primates. Notes address the source of each SNP reported. NHLBI-ESP stands for “National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Exome Sequencing Project.” (B) A domain diagram of SAMHD1 shows the SAM and HD domains. Purple balls indicate the position of the SNPs in panel A, which were tested in this study. As a reference green balls indicate amino acid positions where non-synonymous point mutations are linked to Aicardi–Goutières syndrome (Rice et al., 2009).

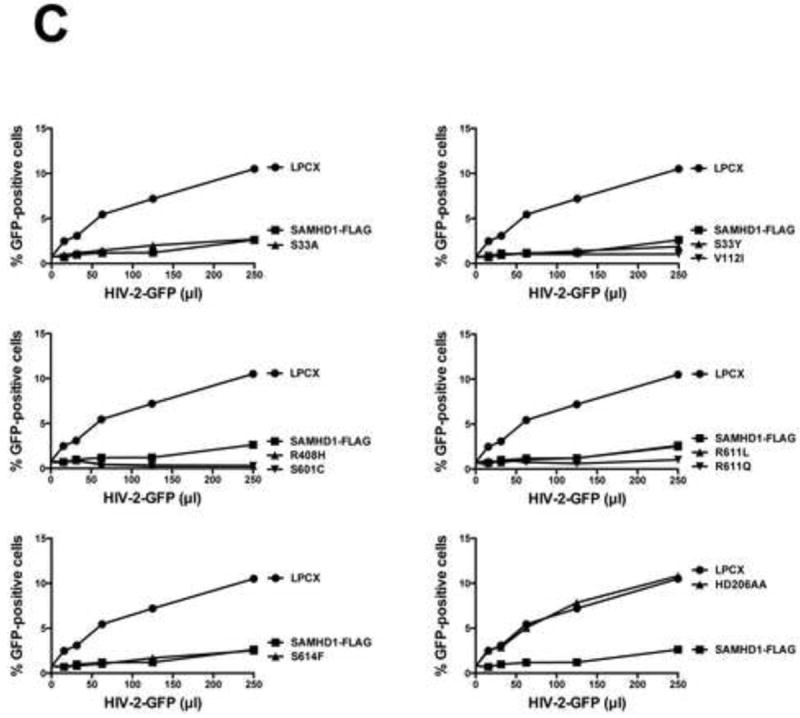

Ability of human SAMHD1 polymorphisms to block HIV-1 infection

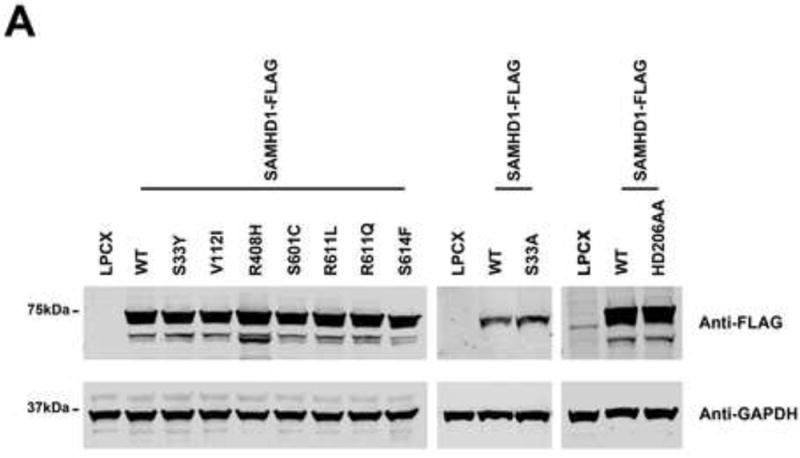

To evaluate the ability of human SAMHD1 polymorphisms to block HIV-1 infection, we inserted the SNPs changes in a SAMHD1-FLAG construct. Subsequently, we stably expressed the human SAMHD1-FLAG polymorphisms in the human monocytic cell line U937, as previously described (Brandariz-Nunez et al., 2012; White et al., 2013a; White et al., 2013b). U937 stably expressing the different human SAMHD1-FLAG polymorphisms were differentiated by treatment with Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (Schwende et al., 1996), and the expression level of human SAMHD1-FLAG polymorphisms was determined by western blotting using anti-FLAG antibodies (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2. Ability of human SAMHD1 polymorphisms to restrict HIV-1 infection.

PMA-treated human monocytic U937 cells stably expressing the indicated human SAMHD1 polymorphisms (A) were challenged with increasing amounts of HIV-1-GFP (B) or HIV-2-GFP (C). As a control, U937 cells stably transduced with the empty vector LPCX were challenged with HIV-1-GFP. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments and a representative experiment is shown. WT, wild type.

Next, we tested the ability of the different human SAMHD1 polymorphisms to restrict HIV-1 infection. For this purpose, we challenged PMA-treated U937 cells expressing the different SAMHD1 variants using an HIV-1 virus expressing GFP as a reporter of infection (HIV-1-GFP). Interestingly, all tested human SAMHD1 polymorphisms showed potent restriction of HIV-1 (Fig. 2B and Table 1). As a control, we challenged cells expressing the SAMHD1-HD206AA variant, which does not block HIV-1 infection, by using increasing amounts of HIV-1-GFP(Hrecka et al., 2011; Laguette et al., 2011). Similar experiments were performed using an HIV-2 virus expressing GFP as a reporter of infection (HIV-2-GFP)(Fig. 2C). These results indicated that human SAMHD1 polymorphisms do not change the ability of SAMHD1 to block HIV-1 or HIV-2 infection.

Table 1.

Human SAMHD1 polymorphisms.

| SAMHD1 Variant | HIV-1 Restrictiona | EIAV Restrictionb | Oligomerizationc | RNA Bindingd | Vpx Degradatione | Localizationf | Cellular dATP Levelg | LINE-1 Retrotranspositionh |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | + | + | + | + | + | N | Low | No |

| S33A | + | + | + | + | + | N | Low | ND |

| S33Y | + | + | + | + | + | N | Low | No |

| V112I | + | + | + | + | + | N | Low | No |

| R408H | + | + | + | + | + | N | Low | No |

| S601C | + | + | + | + | + | N | Low | No |

| R611L | + | + | + | + | + | N | Low | No |

| R611Q | + | + | + | + | + | N | Low | No |

| S614F | + | + | + | + | + | N | Low | No |

WT, wild lype

ND, not determined

Restriction was measured by infecting cells expressing the indicated human SAMHD1 polymorphism with HIV-1-GFP or EIAV-GFP. After 48 h, the percentage of GFP-positive cells (infected cells) was determined by flow cytometry. “+” indicates inhibition of infection similar to the one imposed by wild type SAMHD1.

Human SAMHD1-FLAG polymorphisms were assayed for association with wild-type SAMHD1-HA as described in Materials and Methods. “+” indicates similar oligomerization to the one observed for wild-type SAMHD1.

Human SAMHD1-FLAG polymorphisms were assayed for RNA binding as described in Materials and Methods. “+” indicates similar RNA binding to the one observed for wild type SAMHD1.

Vpx-dependent degradation of each human SAMHD1 polymorphism was determined as described in Materials and Methods. “+” indicates similar Vpx-mediated SAMHD1 degradation to the one observed for wild type SAMHD1.

The subcellular localization of human SAMHD1 polymorphisms was determined as described in Materials and Methods. For each experiment, 200 cells were counted. “N” indicates nuclear localization.

The cellular dATP levels of U937 cells stably expressing the different human SAMHD1 polymorphisms were determined as described in Materials and Methods.” Low” indicates similar dATP levels to the one observed for U937 cells stably expressing wild type SAMHD1.

The ability of LINE-1 to retrotranspose was measured using an EGFP-based reporter assay as described in Materials and Methods. “No” indicates that retrotransposition has not occurred in the presence of the indicated SAMHD1 variant.

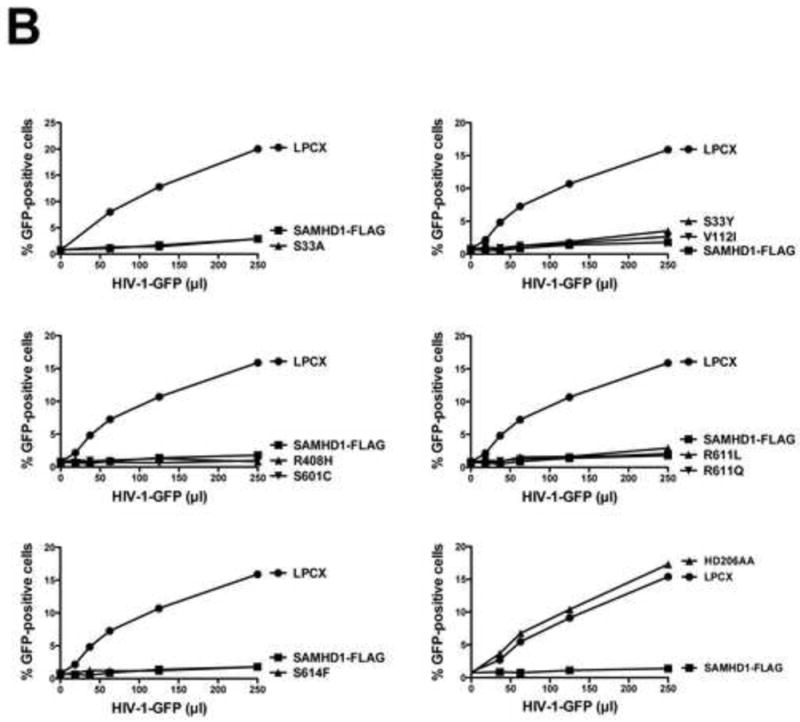

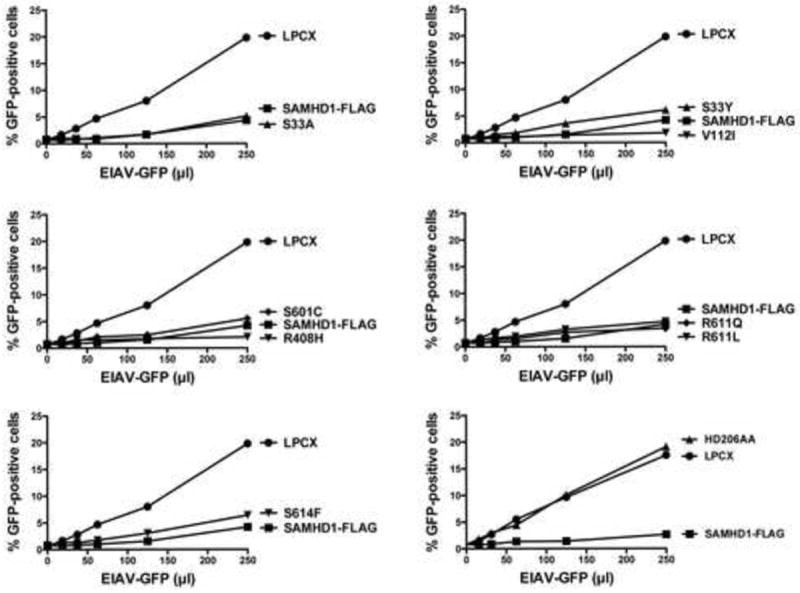

Ability of human SAMHD1 polymorphisms to block equine infectious anemia virus (EIAV) infection

SAMHD1 has the ability to block EIAV infection to a less extent when compared to HIV-1 (White et al., 2013a); therefore, we decided to test the ability of human SAMHD1 polymorphisms to block EIAV-GFP infection. Because the ability of SAMHD1 to block EIAV-GFP is less potent when compared to HIV-1(White et al., 2013a), the goal of these experiments is to investigate whether these polymorphisms exhibit more subtle changes in restriction. Similarly, PMA-treated U937 cells expressing the different human SAMHD1-FLAG polymorphisms were challenged with increasing amounts of EIAV-GFP, as described (Diaz-Griffero et al., 2008). As shown in Figure 3, all tested human SAMHD1 polymorphisms blocked the infection ability of EIAV-GFP. As a control, we challenged cells expressing the SAMHD1-HD206AA variant, which does not block HIV-1 infection(Hrecka et al., 2011; Laguette et al., 2011), by using increasing amounts of EIAV-GFP. These results are in agreement with the hypothesis that human SAMHD1 polymorphisms are not affected in their ability to block HIV-1 infection.

Figure 3. Ability of human SAMHD1 polymorphisms to restrict equine infectious anemia virus (EIAV) infection.

PMA-treated Human monocytic U937 cells stably expressing the indicated mutant and wild type SAMHD1 proteins were challenged with increasing amounts of EIAV-GFP. As a control, U937 cells stably transduced with the empty vector LPCX were challenged with EIAV-GFP. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments and a representative experiment is shown.

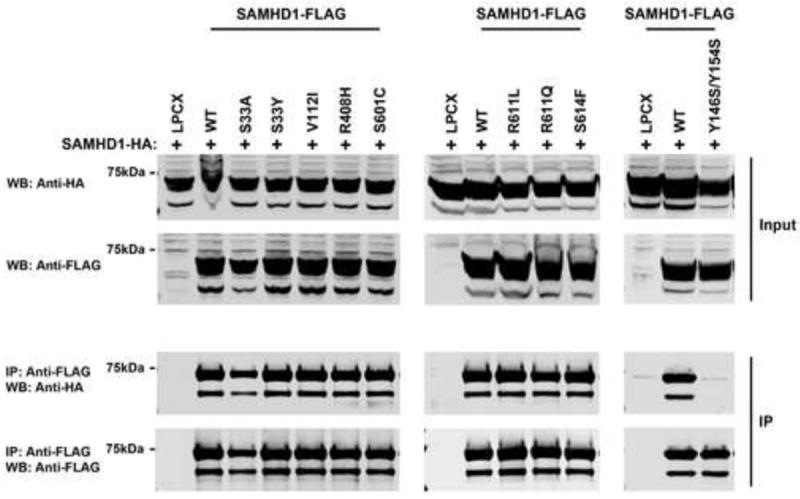

Oligomerization of human SAMHD1 polymorphisms

We have previously demonstrated the ability of SAMHD1 to oligomerize in mammalian cells (White et al., 2013a), which is in agreement with biochemical data suggesting that SAMHD1 is a tetramer (Brandariz-Nunez et al., 2013; Goldstone et al., 2011; Ji et al., 2013; Yan et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2013). For this purpose, we tested the ability of the different human SAMHD1-FLAG polymorphisms to oligomerize with wild type SAMHD1-HA. As shown in Figure 4, all the tested human SAMHD1 polymorphisms were intact for their ability to form oligomers. As a control, we tested the oligomerization ability of the SAMHD1-Y146S/Y154S variant, which is defective for oligomerization(Brandariz-Nunez et al., 2013). These results indicated that all tested human SAMHD1 polymorphisms are not defective for oligomerization.

Figure 4. Oligomerization of the different human SAMHD1 polymorphisms.

Human 293FT cells were cotransfected with a plasmid expressing wild type SAMHD1-HA with either plasmids expressing wild type or the indicated SAMHD1-FLAG variant. Cells were lysed 24 h after transfection and analyzed by Western blotting using anti-HA and anti-FLAG antibodies (Input). Subsequently, lysates were immunoprecipitated by using anti-FLAG agarose beads, as described in Materials and Methods. Anti-FLAG agarose beads were eluted using FLAG peptide, and elutions were analyzed by Western blotting using anti-HA and anti-FLAG antibodies (IP). Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments and representative data is shown. WB, Western blot; IP, Immunoprecipitation; WT, wild type

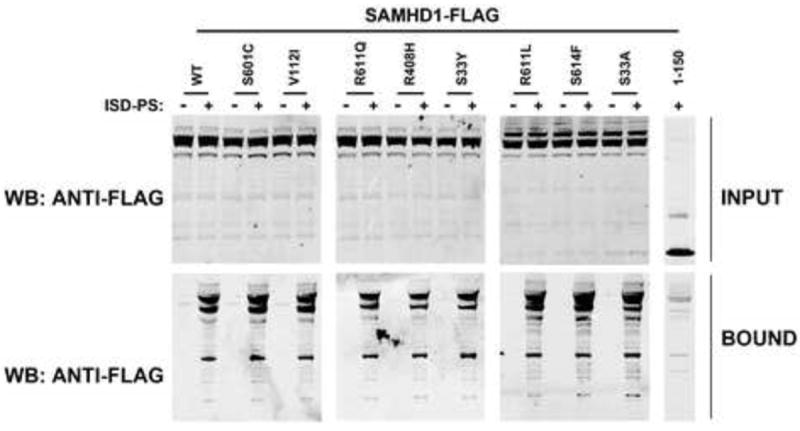

Capability of human SAMHD1 polymorphisms to bind RNA

Others and we have demonstrated the ability of SAMHD1 to bind RNA (Goncalves et al., 2012; White et al., 2013b). Next we tested the ability of human SAMHD1 polymorphisms to bind the interferon-stimulatory DNA sequence containing a phosphorothioate backbone (ISD-PS), which is an RNA analog. As a control, we tested the ability of the SAMHD1 deletion construct 1-150, which is defective on its ability to bind RNA(White et al., 2013a). As shown in Figure 5, all tested human SAMHD1 polymorphisms interacted with ISD-PS when compared to wild-type SAMHD1.

Figure 5. Human SAMHD1 polymorphisms binding to nucleic acids.

Human 293T cells were transfected with plasmid expressing the indicated Human SAMHD1 polymorphisms. Lysed cells 24 h after transfection (INPUT) were incubated with ISD-PS immobilized in StrepTactin Superflow affinity resin. Similarly, eluted proteins from the resin were visualized by Western blotting using anti-FLAG antibodies (BOUND). Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments and a representative experiment is shown. ISD-PS, interferon-stimulatory DNA sequence containing a phosphorothioate backbone; WB, Western blot; WT, wild type.

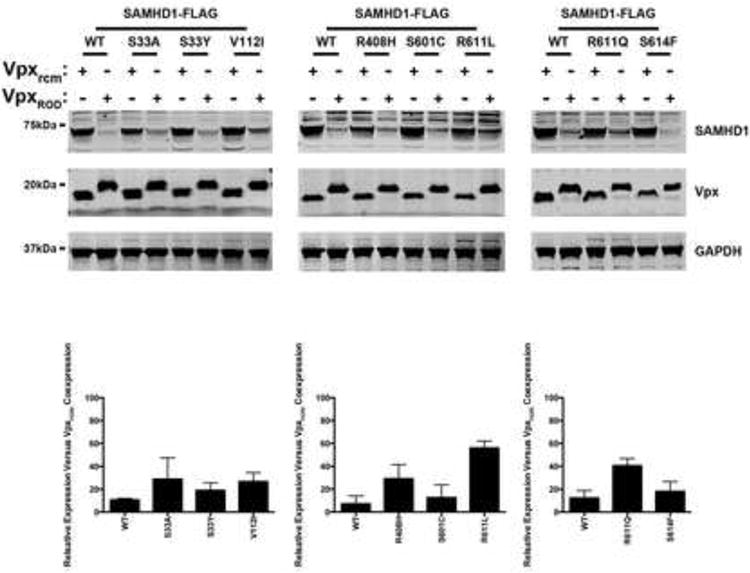

Ability of Vpx to degrade human SAMHD1 polymorphisms

Because the viral protein Vpx from different viruses induces the degradation of SAMHD1, we tested the ability of Vpx from HIV-2ROD (VpxROD) to degrade the different human SAMHD1 polymorphisms, as previously described (White et al., 2013b). For this purpose, we cotransfected the different human SAMHD1 polymorphisms together with VpxROD and measure the expression level of SAMHD1 (Fig. 6). As a control, we cotrans-fected the different human SAMHD1 polymorphisms with Vpx SIVrcm (Vpxrcm), which is unable to induce the degradation of human SAMHD1 (Brandariz-Nunez et al., 2012). As shown in Figure 6, all the tested human SAMHD1 polymorphisms were degraded by VpxROD (Table 1). These results indicated that human SAMHD1 polymorphisms are not defective in their ability to be degraded by Vpx.

Figure 6. Vpx-dependent degradation of single nucleotide polymorphisms of SAMHD1.

HeLa cells were cotransfected with plasmids expressing the indicated SAMHD1 variants and HA-tagged Vpx from HIV-2ROD (VpxROD) or SIVRCM (Vpxrcm). Thirty-six hours post-transfection cells were harvested, and the expression levels of SAMHD1 and Vpx were analyzed by Western blotting using anti-FLAG and anti-HA antibodies. As a loading control, cell extracts were Western blotted using antibodies against GAPDH. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments and a representative experiment is shown. SAMHD1 degradation is expressed as percentage of remaining SAMHD1 protein (lower panels), and a standard deviation is shown.

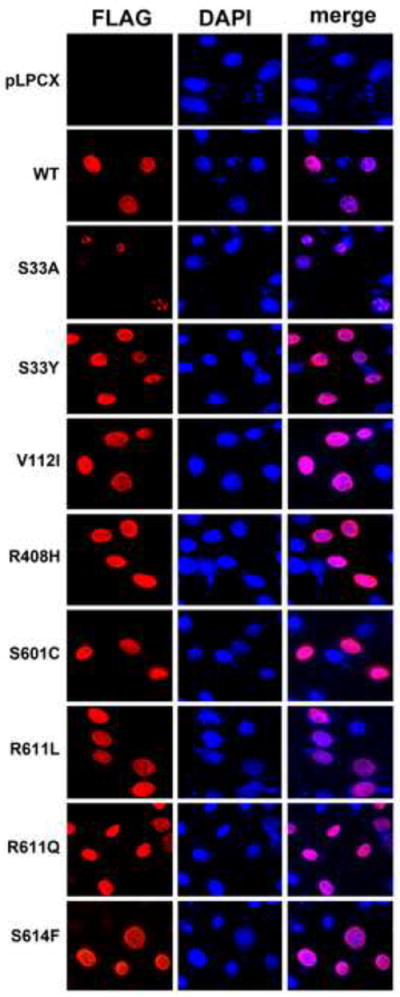

Subcellular localization of human SAMHD1 polymorphisms

SAMHD1 is a nuclear protein that exhibits a nuclear localization signal on residues 11KRPR14 (Brandariz-Nunez et al., 2012; Hofmann et al., 2012; Rice et al., 2009; Wei et al., 2012). Next we tested the subcellular localization of human SAMHD1 polymorphisms in HeLa cells by immunofluorescence, as previously described (Brandariz-Nunez et al., 2012). For this purpose, we transiently transfected the different human SAMHD1-FLAG polymorphisms in HeLa cells and performed immunofluorescence staining using anti-FLAG antibodies. As control, we stained the cellular nuclei using DAPI. As shown in Figure 7, all tested human SAMHD1 polymorphisms localized to the nucleus (Table 1). These experiments suggested that the different human SAMHD1 polymorphisms are not affected for their ability to localize in the nuclear compartment.

Figure 7. Intracellular distribution of human SAMHD1 polymorphisms in HeLa cells.

HeLa cells expressing the indicated human SAMHD1 polymorphism were fixed and immunostained using antibodies against FLAG (red). Cellular nuclei were stained by using DAPI(blue). Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments and a representative experiment is shown. WT, wild type.

Level of cellular dNTPs in U937 cells stably expressing the different human SAMHD1 polymorphisms

Previous observations have suggested that SAMHD1 decreases the intracellular pool of deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs) (Goldstone et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2012; Lahouassa et al., 2012; Powell et al., 2011; White et al., 2013a). To test whether the different human SAMHD1 proteins are affected on their ability to decrease the cellular levels of dNTPs, we measured the levels of dATP, dTTP and dGTP in U937 cells stably expressing the different human SAMHD1 polymorphisms. As shown in Figure 8, all tested human SAMHD1 polymorphisms were able to decrease the cellular levels of dNTPs.

Figrue 8. Cellular dATP, dTTP and dGTP levels in U937 cells stably expressing the different human SAMHD1 polymorphisms.

Quantification of dATP, dTTP and dGTP levels on PMA-treated U937 cells expressing the indicated human SAMHD1 polymorphism was performed by a primer extension assay as described in Materials and Methods. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments and standard deviation is shown. WT, wild type.

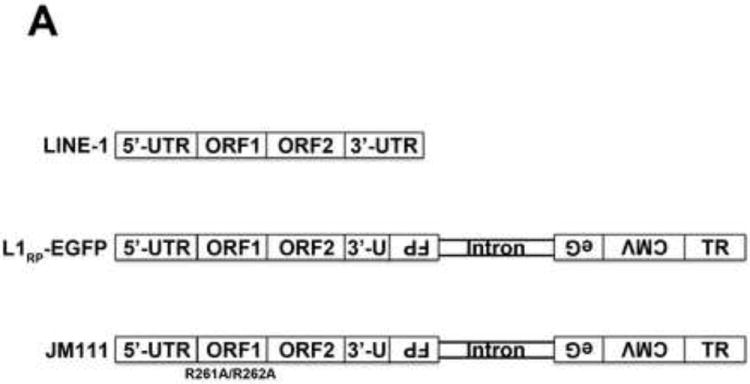

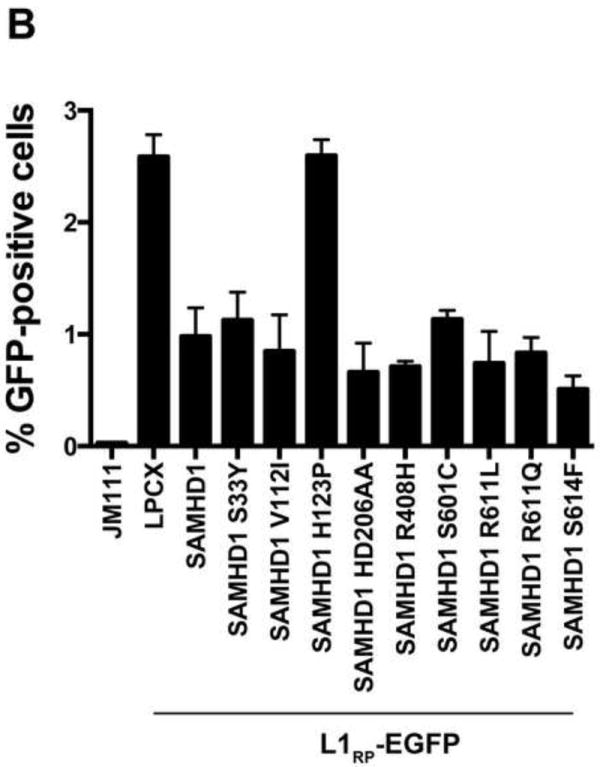

Ability of human SAMHD1 polymorphisms to modulate LINE-1 retrotransposition

Previous investigations have reported the ability of SAMHD1 to negatively modulate retrotransposition of the long interspersed element 1 (LINE-1)(Zhao et al., 2013). Here we tested the ability of the different human SAMHD1 polymorphisms to negatively modulate the LINE-1 retrotransposition. For this purpose, we used a reporter assay to measure LINE-1 retrotransposition in human HEK293T cells (Goodier et al., 2013). We used the LINE-1 construct 99-PUR-RPS-EGFP (L1RP-EGFP), which contains an EGFP reporter gene interrupted by an intron in the opposite transcriptional orientation (Figure 9A). The EGFP cassette is inserted into the 3’UTR of a retrotransposition-component L1 (L1RP). EGFP is expressed only when the intron of the LINE-1 transcript is removed by splicing, and the resulting transcript is reverse transcribed and subsequently integrated into the genomic DNA. After integration the EGFP gene will be expressed from its CMV promoter (Figure 9A). As a control, we will use the same L1RP EGFP construct containing two missense mutations on the ORF1 (JM111)(Figure 9A) (Moran et al., 1996). As shown in Figure 9B, all tested SAMHD1 polymorphisms negatively modulated LINE-1 retrotransposition when compared to wild type SAMHD1. As control, we used the SAMHD1 variant H123P, which does not inhibit LINE-1 retrotrans-position (Zhao et al., 2013). These results indicated that all the tested SAMHD1 polymorphisms negatively modulated LINE-1 retrotransposition.

Figrue 9. Modulation of LINE-1 retrotransposition by human SAMHD1 SNPs.

(A) Schematic representation of the different vectors used in the LINE-1 enhanced-GFP(EGFP)-based reporter assay. LINE-1, 99-PUR-RPS-EGFP (L1RP-EGFP) and JM111 (JM111) are shown. The 99-PUR-RPS-EGFP contains combined promoters from both CMV and the 5’-UTR of the LINE-1. An antisense cassette of EGFP containing an inserted intron sequence was cloned near the 3’ end of the L1 3’ UTR. JM111, the negative control for retrotransposition, contains the double mutation R261A/R262A in ORF1, which has been shown to abolish the retrotransposition activity of LINE-1. The occurrence of retrotransposition is detected by expression of EGFP in human HEK293T cells. (B) The ability of the indicated SAMHD1 variants to inhibit retrotransposition was measured by cotransfecting the LINE-1 reporter vector, 99 PUR RPS EGFP (L1RP-EGFP), together with the different FLAG-tagged SAMHD1 variants into HEK293T cells. Five days post-transfection, the occurrence of retrotransposition was determined by expression of EGFP measured by flow cytometry. As control, we have cotransfected the empty vector LPCX in HEK 293T cells as described in the Materials and Methods. The defective LINE-1 construct, JM111, was used for determining the background levels of EGFP. The SAMHD1 mutant H123P was used as a positive control. Experiments were performed in triplicates and a standard deviation is shown.

DISCUSSION

This work explores the different features of human SAMHD1 polymorphisms. We have focused our experiments on studying human polymorphisms on residues that have been positively selected during primate speciation (Laguette et al., 2012; Lim et al., 2012). We initially tested for the ability of these polymorphisms to block HIV-1 and HIV-2 infection. None of the tested SAMHD1 polymorphisms lost the ability to block HIV-1 or HIV-2 infection. To further understand the anti-viral activity of these variants, we tested for their ability to block EIAV, a virus restricted by SAMHD1 to a lesser extent when compared to HIV-1. Interestingly, we found that all tested SAMHD1 polymorphisms block EIAV infection. Overall these results suggested that all tested human SAMHD1 polymorphisms are not affected for their anti-retroviral properties. One caveat of these experiments is that we are overexpressing the different SAMHD1 variants, which raises the possibility that at endogenous levels this protein might have different anti-retroviral properties.

Next we thoroughly characterize the biochemical properties of the different SAMHD1 polymorphisms. As we have previously described, we have established an assay to detect oligomerization of SAMHD1 proteins in mammalian cells (Brandariz-Nunez et al., 2013; White et al., 2013a; White et al., 2013b). Our results indicated that all human SAMHD1 polymorphisms retained their oligomerization properties. Because SAMHD1 has the ability to bind RNA in vitro (Goncalves et al., 2012; White et al., 2013a), we tested the ability of SAMHD1 variants to bind RNA. All tested human SAMHD1 polymorphisms retained the ability to bind RNA in vitro.

Because Vpx triggers the degradation of SAMHD1 (Hrecka et al., 2011; Laguette et al., 2011), we tested the ability of Vpx to induce the degradation of the different human SAMHD1 polymorphisms. All tested human SAMHD1 polymorphisms were degraded by Vpx. Similarly we tested the nuclear localization of the different human SAMHD1 variants. In agreement with our body of work, none of the studied human SAMHD1 variants lost nuclear localization.

We and others have previously reported that the ability of SAMHD1 to decrease the cellular levels of dNTPs is necessary but not sufficient to restrict HIV-1(Cribier et al., 2013; Welbourn et al., 2013; White et al., 2013b). If these functions were independent, SAMHD1 polymorphisms where the ability to decrease the cellular levels of dNTPs is lost were expected to emerge. However, we did not observe these in the studied polymorphisms. The fact that we did not find SAMHD1 polymorphisms that are affected in dNTPase activity but not on HIV-1 restriction is in agreement with our hypothesis that dNTPase activity is necessary but not sufficient for restriction.

We also tested the ability of the different SAMHD1 variants to decrease the cellular levels of dNTPs. None of the tested human SAMHD1 polymorphisms decreased the cellular levels of dNTPs. Finally, we tested the ability of the different human SAMHD1 polymorphisms to negatively modulate LINE-1 retrotransposition. In agreement with previous findings suggesting that SAMHD1 negatively modulate LINE-1 retrotransposition (Zhao et al., 2013), we found that all tested human SAMHD1 polymorphisms negatively modulate LINE-1 retrotransposition. Overall our work demonstrated that all the human SAMHD1 polymorphisms studied here did not show any defect on antiviral activity, oligomerization, binding to RNA, Vpx-mediated degradation, subcellular localization, dNTPase activity, and inhibition of LINE-1 retrotransposition.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Identification of human SNPs

SNPs were identified in the dbSNP database at NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/), and cross-checked against data in the 1000 Genomes project (http://www.1000genomes.org/). S601C was observed only one time, in the genome of an Asian individual. R611Q was observed one time in an African individual, and one time in an individual from the Americas. Except for these two SNPs, both included in the 1000 Genomes project, information on the geographic distribution of other SNPs is unknown. Efforts to obtain further information regarding the source of the R611L SNP record at NCBI were not fruitful. Non-human primate SAMHD1 sequences were downloaded from Genbank.

Cell lines and Plasmids

Human U937 (ATCC#CRL-1593) cells were grown in RPMI suplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum and 1% (v/v) penicilin/streptomycin. Human HeLa cells (ATCC# CCL-2) were grown on DMEM suplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% (w/v) penicilin/streptomycin. LPCX-SAMHD1-FLAG plasmids expressing the codon optimized SAMHD1 fused to either FLAG epitope were previously described (Brandariz-Nunez et al., 2012). The plasmids expressing human SAMHD1 polymorphisms were created using specific primers and pLPCX-SAMHD1-FLAG as template.

Generation of U937 cells stably expressing SAMHD1 variants

Retroviral vectors encoding wild type or mutant SAMHD1 proteins fused to FLAG were created using the LPCX vector (Clontech). Recombinant viruses were produced in 293T cells by co-transfecting the LPCX plasmids with the pVPack-GP and pVPack-VSV-G packaging plasmids (Clontech). The pVPack-VSV-G plasmid encodes the vesicular stomatitis virus G envelope glycoprotein, which allows efficient entry into a wide range of vertebrate cells (Yee et al., 1994). Transduced human monocytic U937 cells were selected in 0.4 μg /ml puromycin (Sigma).

Protein analysis

Cellular proteins were extracted with radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer as previously described (Lienlaf et al., 2011). Detection of proteins by Western blotting was performed using anti-FLAG (Sigma) or anti-GAPDH (Ambion) antibodies. Secondary antibodies against rabbit and mouse conjugated to Alexa Fluor 680 were obtained from Li-Cor. Bands were detected by scanning blots using the Li-Cor Odyssey Imaging System in the 700 nm channel.

Infection with retroviruses expressing the green fluorescent protein (GFP)

Recombinant retroviruses expressing GFP, pseudotyped with the VSV-G glycoprotein, were prepared as described (Diaz-Griffero et al., 2008). For infections, 6 × 104 cells were seeded in 24-well plates and treated with 10ng/ml phorbol-12-myristate-3-acetate (PMA) for 16 hours. PMA stock solution was prepared in DMSO at 250 μg/ml. Subsequently, cells were incubated with the indicated retrovirus for 48 hours at 37°C. The percentage of GFP-positive cells was determined by flow cytometry (Becton Dickinson). Viral stocks were titrated by serial dilution on dog Cf2Th cells.

SAMHD1 oligomerization assay

Approximately 1.0 × 107 human 293T cells were cotransfected with plasmids encoding SAMHD1 variants tagged with FLAG and HA. After 24 hours, cells were lysed in 0.5 ml of whole-cell extract (WCE) buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 280 mM NaCl, 0.5% IGEPAL, 10% glycerol, 5mM MgCl2, 50 μg/ml ethidium bromide, 50 U/ml benzonase [Roche]). Lysates were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 1 h at 4°C. Post-spin lysates were then pre-cleared using protein A-agarose (Sigma) for 1 h at 4°C; a small aliquot of each of these lysates was stored as Input. Pre-cleared lysates containing the tagged proteins were incubated with anti-FLAG-agarose beads (Sigma) for 2 h at 4°C. Anti-FLAG-agarose beads were washed three times in WCE buffer, and immune complexes were eluted using 200 μg of FLAG tripeptide/ml in WCE buffer. The eluted samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting using either anti-HA or anti-FLAG antibodies (immunoprecipitates).

Nucleic-acid binding assay

Nucleic-acid binding assay was performed as previously described (Goncalves et al., 2012; White et al., 2013a). In brief, the synthetic DNA phosphorothioate-containing interferon-stimulatory DNA (ISD-PS), which is an RNA analog, was synthesized with a 5′-biotin tag using the following primers: ISD sense 5′-tacagatctactagtgatctatgactgatctgtacatgatctaca-3′, and ISD antisense 5′-tgtagatcatgtacagatcagtcatagatcactagtagatctgta-3′ Sense and antisense primers were incubated at 65 °C for 20 minutes, and primers were allowed to anneal by cooling down to room temperature. Anealed primers were immobilized on a Ultralink Immobilized Streptavidin Plus Gel (Pierce). Cells were lysed using TAP lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 0.2% NP-40, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 25 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, protease inhibitors) and lysates were cleared by centrifugation. Cleared lysates (Input) were incubated with immobilized nucleic acids at 4°C on a rotary wheel for 2h in the presence of 10 μg/ml of Calf-thymus DNA (Sigma) as a competitor. Unbound proteins were removed by three consecutive washes in TAP lysis buffer. Bound proteins to nucleic acids (Bound) were eluted by boiling samples in Laemmli sample buffer (63 mM Tris HCl, 10% Glycerol 2% SDS, 0.0025% Bromophenol Blue) and analyzed by Western blotting using anti-FLAG antibodies (Sigma).

Assay to meassure SAMHD1 degradation by Vpx

8.0 × 106 HeLa cells were transfected in suspension using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Transfection mixtures conatined 0.25 μg of a plasmid expressing each human SAMHD1-FLAG polymorphism and 20 μg of plasmids expressing either VpxROD-HA or Vpxrcm-HA. The transfection mixture was plated in a 10 cm plate for 24 h. Subsequently, cells were incubated in complete media [DMEM suplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% (w/v) penicilin/streptomycin] for an additional 24 h. Cells lyzates were analyzed for expressiong of SAMHD1-FLAG and Vpx-HA by Western blotting using anti-FLAG and anti-HA antibodies.

Transfections and subcellular localization by Immunofluorescence microscopy

Transfections of cell monolayers were performed using Lipofectamine Plus reagent (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Transfections were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Indirect immunofluorescence microscopy was perfomed as previously described (Diaz-Griffero et al., 2002). Transfected monolayers grown on coverslips were washed twice with PBS1X (137 NaCl mM, KCl 2.7 mM, Na2HPO4 • 2 H2O 10 mM, KH2PO4 mM) and fixed for 15 min in 3.9 % paraformaldehyde in PBS1X. Fixed cells were washed twice in PBS1X, permeabilize for 4 min in permeabilizing buffer (0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS), and then blocked in PBS1X containing 2% bovine serum albumin(blocking buffer) for 1h at room temperature. Cells were then incubated for 1h at room temperature with primary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer. After three washes with PBS, cells were incubated for 30 min in secondary antibodies and 1μg of DAPI (49, 69-diamidino-2-phenylindole)/ml. Samples were mounted for fluorescence microscopy by using the ProLong Antifade Kit (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Images were obtained with a Zeiss Observer.Z1 microscope using a 63X objective, and deconvolution was performed using the software AxioVision V4.8.1.0 (Carl Zeiss Imaging Solutions).

Cellular dNTPs quantification by a primer extension assay

2-3 × 106 cells were collected for each cell type. Cells were washed twice with 1x PBS, pelleted and resuspended in ice cold 65% methanol in Millipore grade water. Cells were vortexed for 2 minutes and incubated at 95°C for 3 minutes. Cells were centrifuged at 14000 rpm for 3 minutes and the supernatant was transferred to a new tube for the complete drying of the methanol by using a speed vac. The dried samples were resuspended in Millipore grade water. An 18-nucleotide primer labeled at the 5′ end with a-32P (5′-GTCCCTGTTCGGGCGCCA-3′) was annealed at a 1:2 ratio respectively to four different 19-nucleotide templates (5′-NTGGCGCCCGAACAGGGAC-3′), where ‘N’ represents nucleotide variation at the 5′ end. Reaction condition contains 200 fmoles of template primer, 2 μl of 0.5 mM dNTP mix for positive control or dNTP cell extract, 4 μl of excess HIV-1 RT, 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, and 10 μM oligo(dT) to a final volume of 20uL. The reaction was incubated at 37°C for 5 minutes before being quenched with 10uL of 40 mM EDTA and 99% (vol/vol) formamide at 95°C for 5 minutes. The extended primer products were resolved on a 14% urea-PAGE gel and analyze using a phosphoimager. The extended products were quantified using QuantityOne software to quantify percent volume of saturation. The quantified dNTP content of each sample was accounted for based on its dilution factor, so that each sample volume was adjusted to obtain a signal within the linear range of the assay (Kim et al., 2012; Lahouassa et al., 2012).

LINE-1 Retrotransposition Assay

2.5 × 105 293T cells/well were seeded in 6-well plates. The following day, 1.0 mg of 99-PUR-RPS-EGFP(L1RP-EGFP) was co-transfected with 0.5mg of empty vector (LPCX) or SAMHD1 variant (three replicate wells). Five days post-transfection, cells having a retrotransposition event, and hence expressing EGFP, were assayed by flow cytometry. Gating exclusions were based on background fluorescence of plasmid 99-PUR-JM111-EGFP(JM111), which has a double-point mutation in ORF1 that abolishes retrotransposition (R261A/R262A). Within each experiment, results were normalized to fluorescence of 99-PUR-RPS-EGFP co-transfected with LPCX empty vector.

Highlights.

Human SAMHD1 single-nucleotide polymorphisms block HIV-1 and HIV-2 infection.

SAMHD1 polymorphisms do not affect its ability to block LINE-1 retrotransposition.

SAMHD1 polymorphisms decrease the cellular levels of dNTPs.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by an NIH R01 AI087390 to F.D.-G. We are grateful to John L. Goodier from the Kazazian lab for providing plasmids for the LINE-1 reporter assay. S.L.S. was funded by an NIH R01-GM-093086 award.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahn J, Hao C, Yan J, DeLucia M, Mehrens J, Wang C, Gronenborn AM, Skowronski J. HIV/simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) accessory virulence factor Vpx loads the host cell restriction factor SAMHD1 onto the E3 ubiquitin ligase complex CRL4DCAF1. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:12550–12558. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.340711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arfi V, Riviere L, Jarrosson-Wuilleme L, Goujon C, Rigal D, Darlix JL, Cimarelli A. Characterization of the early steps of infection of primary blood monocytes by human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 2008;82:6557–6565. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02321-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldauf HM, Pan X, Erikson E, Schmidt S, Daddacha W, Burggraf M, Schenkova K, Ambiel I, Wabnitz G, Gramberg T, Panitz S, Flory E, Landau NR, Sertel S, Rutsch F, Lasitschka F, Kim B, Konig R, Fackler OT, Keppler OT. SAMHD1 restricts HIV-1 infection in resting CD4(+) T cells. Nat Med. 2012 doi: 10.1038/nm.2964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belshan M, Mahnke LA, Ratner L. Conserved amino acids of the human immunodeficiency virus type 2 Vpx nuclear localization signal are critical for nuclear targeting of the viral preintegration complex in non-dividing cells. Virology. 2006;346:118–126. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergamaschi A, Ayinde D, David A, Le Rouzic E, Morel M, Collin G, Descamps D, Damond F, Brun-Vezinet F, Nisole S, Margottin-Goguet F, Pancino G, Transy C. The human immunodeficiency virus type 2 Vpx protein usurps the CUL4A-DDB1 DCAF1 ubiquitin ligase to overcome a postentry block in macrophage infection. J Virol. 2009;83:4854–4860. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00187-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger A, Sommer AF, Zwarg J, Hamdorf M, Welzel K, Esly N, Panitz S, Reuter A, Ramos I, Jatiani A, Mulder LC, Fernandez-Sesma A, Rutsch F, Simon V, Konig R, Flory E. SAMHD1-deficient CD14+ cells from individuals with Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome are highly susceptible to HIV-1 infection. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002425. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandariz-Nunez A, Valle-Casuso JC, White TE, Laguette N, Benkirane M, Brojatsch J, Diaz-Griffero F. Role of SAMHD1 nuclear localization in restriction of HIV-1 and SIVmac. Retrovirology. 2012;9:49. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-9-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandariz-Nunez A, Valle-Casuso JC, White TE, Nguyen L, Bhattacharya A, Wang Z, Demeler B, Amie S, Knowlton C, Kim B, Ivanov DN, Diaz-Griffero F. Contribution of oligomerization to the anti-HIV-1 properties of SAMHD1. Retrovirology. 2013;10:131. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-10-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cribier A, Descours B, Valadao AL, Laguette N, Benkirane M. Phosphorylation of SAMHD1 by Cyclin A2/CDK1 Regulates Its Restriction Activity toward HIV-1. Cell Rep. 2013;3:1036–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Descours B, Cribier A, Chable-Bessia C, Ayinde D, Rice G, Crow Y, Yatim A, Schwartz O, Laguette N, Benkirane M. SAMHD1 restricts HIV-1 reverse transcription in quiescent CD4+ T-cells. Retrovirology. 2012;9:87. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-9-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Griffero F, Hoschander SA, Brojatsch J. Endocytosis is a critical step in entry of subgroup B avian leukosis viruses. J Virol. 2002;76:12866–12876. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.24.12866-12876.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Griffero F, Perron M, McGee-Estrada K, Hanna R, Maillard PV, Trono D, Sodroski J. A human TRIM5alpha B30.2/SPRY domain mutant gains the ability to restrict and prematurely uncoat B-tropic murine leukemia virus. Virology. 2008;378:233–242. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher TM, 3rd, Brichacek B, Sharova N, Newman MA, Stivahtis G, Sharp PM, Emerman M, Hahn BH, Stevenson M. Nuclear import and cell cycle arrest functions of the HIV-1 Vpr protein are encoded by two separate genes in HIV-2/SIV(SM) Embo J. 1996;15:6155–6165. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fregoso OI, Ahn J, Wang C, Mehrens J, Skowronski J, Emerman M. Evolutionary toggling of Vpx/Vpr specificity results in divergent recognition of the restriction factor SAMHD1. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003496. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita M, Otsuka M, Miyoshi M, Khamsri B, Nomaguchi M, Adachi A. Vpx is critical for reverse transcription of the human immunodeficiency virus type 2 genome in macrophages. J Virol. 2008;82:7752–7756. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01003-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs JS, Lackner AA, Lang SM, Simon MA, Sehgal PK, Daniel MD, Desrosiers RC. Progression to AIDS in the absence of a gene for vpr or vpx. J Virol. 1995;69:2378–2383. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2378-2383.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstone DC, Ennis-Adeniran V, Hedden JJ, Groom HC, Rice GI, Christodoulou E, Walker PA, Kelly G, Haire LF, Yap MW, de Carvalho LP, Stoye JP, Crow YJ, Taylor IA, Webb M. HIV-1 restriction factor SAMHD1 is a deoxynucleoside triphosphate triphosphohydrolase. Nature. 2011;480:379–382. doi: 10.1038/nature10623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goncalves A, Karayel E, Rice GI, Bennett KL, Crow YJ, Superti-Furga G, Burckstummer T. SAMHD1 is a nucleic-acid binding protein that is mislocalized due to aicardi-goutieres syndrome-associated mutations. Hum Mutat. 2012 doi: 10.1002/humu.22087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodier JL, Cheung LE, Kazazian HH., Jr Mapping the LINE1 ORF1 protein interactome reveals associated inhibitors of human retrotransposition. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:7401–7419. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goujon C, Arfi V, Pertel T, Luban J, Lienard J, Rigal D, Darlix JL, Cimarelli A. Characterization of simian immunodeficiency virus SIVSM/human immunodeficiency virus type 2 Vpx function in human myeloid cells. J Virol. 2008;82:12335–12345. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01181-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goujon C, Jarrosson-Wuilleme L, Bernaud J, Rigal D, Darlix JL, Cimarelli A. Heterologous human immunodeficiency virus type 1 lentiviral vectors packaging a simian immunodeficiency virus-derived genome display a specific postentry transduction defect in dendritic cells. J Virol. 2003;77:9295–9304. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.17.9295-9304.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goujon C, Riviere L, Jarrosson-Wuilleme L, Bernaud J, Rigal D, Darlix JL, Cimarelli A. SIVSM/HIV-2 Vpx proteins promote retroviral escape from a proteasome-dependent restriction pathway present in human dendritic cells. Retrovirology. 2007;4:2. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch VM, Sharkey ME, Brown CR, Brichacek B, Goldstein S, Wakefield J, Byrum R, Elkins WR, Hahn BH, Lifson JD, Stevenson M. Vpx is required for dissemination and pathogenesis of SIV(SM) PBj: evidence of macrophage-dependent viral amplification. Nat Med. 1998;4:1401–1408. doi: 10.1038/3992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann H, Logue EC, Bloch N, Daddacha W, Polsky SB, Schultz ML, Kim B, Landau NR. The Vpx lentiviral accessory protein targets SAMHD1 for degradation in the nucleus. J Virol. 2012 doi: 10.1128/JVI.01657-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hrecka K, Hao C, Gierszewska M, Swanson SK, Kesik-Brodacka M, Srivastava S, Florens L, Washburn MP, Skowronski J. Vpx relieves inhibition of HIV-1 infection of macrophages mediated by the SAMHD1 protein. Nature. 2011;474:658–661. doi: 10.1038/nature10195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji X, Wu Y, Yan J, Mehrens J, Yang H, DeLucia M, Hao C, Gronenborn AM, Skowronski J, Ahn J, Xiong Y. Mechanism of allosteric activation of SAMHD1 by dGTP. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:1304–1309. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin L, Zhou Y, Ratner L. HIV type 2 Vpx interaction with Gag and incorporation into virus-like particles. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2001;17:105–111. doi: 10.1089/08892220150217193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson WE, Sawyer SL. Molecular evolution of the antiretroviral TRIM5 gene. Immunogenetics. 2009;61:163–176. doi: 10.1007/s00251-009-0358-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappes JC, Parkin JS, Conway JA, Kim J, Brouillette CG, Shaw GM, Hahn BH. Intracellular transport and virion incorporation of vpx requires interaction with other virus type-specific components. Virology. 1993;193:222–233. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushik R, Zhu X, Stranska R, Wu Y, Stevenson M. A cellular restriction dictates the permissivity of nondividing monocytes/macrophages to lentivirus and gammaretrovirus infection. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;6:68–80. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B, Nguyen LA, Daddacha W, Hollenbaugh JA. Tight Interplay among SAMHD1 Protein Level, Cellular dNTP Levels, and HIV-1 Proviral DNA Synthesis Kinetics in Human Primary Monocyte-derived Macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:21570–21574. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C112.374843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laguette N, Rahm N, Sobhian B, Chable-Bessia C, Munch J, Snoeck J, Sauter D, Switzer WM, Heneine W, Kirchhoff F, Delsuc F, Telenti A, Benkirane M. Evolutionary and functional analyses of the interaction between the myeloid restriction factor SAMHD1 and the lentiviral Vpx protein. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;11:205–217. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laguette N, Sobhian B, Casartelli N, Ringeard M, Chable-Bessia C, Segeral E, Yatim A, Emiliani S, Schwartz O, Benkirane M. SAMHD1 is the dendritic- and myeloid-cell-specific HIV-1 restriction factor counteracted by Vpx. Nature. 2011;474:654–657. doi: 10.1038/nature10117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahouassa H, Daddacha W, Hofmann H, Ayinde D, Logue EC, Dragin L, Bloch N, Maudet C, Bertrand M, Gramberg T, Pancino G, Priet S, Canard B, Laguette N, Benkirane M, Transy C, Landau NR, Kim B, Margottin-Goguet F. SAMHD1 restricts the replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by depleting the intracellular pool of deoxynucleoside triphosphates. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:621. doi: 10.1038/ni.2236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lienlaf M, Hayashi F, Di Nunzio F, Tochio N, Kigawa T, Yokoyama S, Diaz-Griffero F. Contribution of E3-ubiquitin ligase activity to HIV-1 restriction by TRIM5alpha(rh): structure of the RING domain of TRIM5alpha. J Virol. 2011;85:8725–8737. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00497-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim ES, Fregoso OI, McCoy CO, Matsen FA, Malik HS, Emerman M. The ability of primate lentiviruses to degrade the monocyte restriction factor SAMHD1 preceded the birth of the viral accessory protein Vpx. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;11:194–204. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyerson NR, Sawyer SL. Two-stepping through time: mammals and viruses. Trends Microbiol. 2011;19:286–294. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran JV, Holmes SE, Naas TP, DeBerardinis RJ, Boeke JD, Kazazian HH., Jr High frequency retrotransposition in cultured mammalian cells. Cell. 1996;87:917–927. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81998-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park IW, Sodroski J. Amino acid sequence requirements for the incorporation of the Vpx protein of simian immunodeficiency virus into virion particles. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1995;10:506–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell RD, Holland PJ, Hollis T, Perrino FW. Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome gene and HIV-1 restriction factor SAMHD1 is a dGTP-regulated deoxynucleotide triphosphohydrolase. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:43596–43600. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C111.317628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice GI, Bond J, Asipu A, Brunette RL, Manfield IW, Carr IM, Fuller JC, Jackson RM, Lamb T, Briggs TA, Ali M, Gornall H, Couthard LR, Aeby A, Attard-Montalto SP, Bertini E, Bodemer C, Brockmann K, Brueton LA, Corry PC, Desguerre I, Fazzi E, Cazorla AG, Gener B, Hamel BC, Heiberg A, Hunter M, van der Knaap MS, Kumar R, Lagae L, Landrieu PG, Lourenco CM, Marom D, McDermott MF, van der Merwe W, Orcesi S, Prendiville JS, Rasmussen M, Shalev SA, Soler DM, Shinawi M, Spiegel R, Tan TY, Vanderver A, Wakeling EL, Wassmer E, Whittaker E, Lebon P, Stetson DB, Bonthron DT, Crow YJ. Mutations involved in Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome implicate SAMHD1 as regulator of the innate immune response. Nat Genet. 2009;41:829–832. doi: 10.1038/ng.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwende H, Fitzke E, Ambs P, Dieter P. Differences in the state of differentiation of THP-1 cells induced by phorbol ester and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. J Leukoc Biol. 1996;59:555–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selig L, Pages JC, Tanchou V, Preveral S, Berlioz-Torrent C, Liu LX, Erdtmann L, Darlix J, Benarous R, Benichou S. Interaction with the p6 domain of the gag precursor mediates incorporation into virions of Vpr and Vpx proteins from primate lentiviruses. J Virol. 1999;73:592–600. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.592-600.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spragg CJ, Emerman M. Antagonism of SAMHD1 is actively maintained in natural infections of simian immunodeficiency virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316839110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava S, Swanson SK, Manel N, Florens L, Washburn MP, Skowronski J. Lentiviral Vpx accessory factor targets VprBP/DCAF1 substrate adaptor for cullin 4 E3 ubiquitin ligase to enable macrophage infection. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000059. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunseri N, O’Brien M, Bhardwaj N, Landau NR. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 modified to package Simian immunodeficiency virus Vpx efficiently infects macrophages and dendritic cells. J Virol. 2011;85:6263–6274. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00346-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W, Guo H, Gao Q, Markham R, Yu XF. Variation of two primate lineage-specific residues in human SAMHD1 confers resistance to N terminus-targeted SIV Vpx proteins. J Virol. 2014;88:583–591. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02866-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W, Guo H, Han X, Liu X, Zhou X, Zhang W, Yu XF. A novel DCAF1-binding motif required for Vpx-mediated degradation of nuclear SAMHD1 and Vpr-induced G2 arrest. Cellular microbiology. 2012;14:1745–1756. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2012.01835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welbourn S, Dutta SM, Semmes OJ, Strebel K. Restriction of virus infection but not catalytic dNTPase activity are regulated by phosphorylation of SAMHD1. J Virol. 2013 doi: 10.1128/JVI.01642-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White TE, Brandariz-Nunez A, Valle-Casuso JC, Amie S, Nguyen L, Kim B, Brojatsch J, Diaz-Griffero F. Contribution of SAM and HD domains to retroviral restriction mediated by human SAMHD1. Virology. 2013a;436:81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White TE, Brandariz-Nunez A, Valle-Casuso JC, Amie S, Nguyen LA, Kim B, Tuzova M, Diaz-Griffero F. The Retroviral Restriction Ability of SAMHD1, but Not Its Deoxynucleotide Triphosphohydrolase Activity, Is Regulated by Phosphorylation. Cell Host Microbe. 2013b;13:441–451. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J, Kaur S, Delucia M, Hao C, Mehrens J, Wang C, Golczak M, Palczewski K, Gronenborn AM, Ahn J, Skowronski J. Tetramerization of SAMHD1 Is Required for Biological Activity and Inhibition of HIV Infection. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:10406–10417. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.443796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee JK, Friedmann T, Burns JC. Generation of high-titer pseudotyped retroviral vectors with very broad host range. Methods Cell Biol. 1994;43(Pt A):99–112. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60600-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu XF, Ito S, Essex M, Lee TH. A naturally immunogenic virion-associated protein specific for HIV-2 and SIV. Nature. 1988;335:262–265. doi: 10.1038/335262a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu XF, Yu QC, Essex M, Lee TH. The vpx gene of simian immunodeficiency virus facilitates efficient viral replication in fresh lymphocytes and macrophage. J Virol. 1991;65:5088–5091. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.9.5088-5091.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, de Silva S, Wang JH, Wu L. Co-evolution of primate SAMHD1 and lentivirus Vpx leads to the loss of the vpx gene in HIV-1 ancestor. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e37477. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao K, Du J, Han X, Goodier JL, Li P, Zhou X, Wei W, Evans SL, Li L, Zhang W, Cheung LE, Wang G, Kazazian HH, Jr, Yu XF. Modulation of LINE-1 and Alu/SVA retrotransposition by Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome-related SAMHD1. Cell Rep. 2013;4:1108–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu C, Gao W, Zhao K, Qin X, Zhang Y, Peng X, Zhang L, Dong Y, Zhang W, Li P, Wei W, Gong Y, Yu XF. Structural insight into dGTP-dependent activation of tetrameric SAMHD1 deoxynucleoside triphosphate triphosphohydrolase. Nature communications. 2013;4:2722. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]