Abstract

Aging is a dominant risk factor for most forms of cardiovascular disease. Impaired angiogenesis and endothelial dysfunction likely contribute to the increased prevalence of both cardiovascular diseases and their adverse sequelae in the elderly. Angiogenesis is both an essential adaptive response to physiological stress and an endogenous repair mechanism after ischemic injury. In addition, induction of angiogenesis is a promising therapeutic approach for ischemic diseases. For these reasons, understanding the basis of age-related impairment of angiogenesis and endothelial function has important implications for understanding and managing cardiovascular disease. In this review we discuss the molecular mechanisms that contribute to impaired angiogenesis in the elderly and potential therapeutic approaches to improving vascular function and angiogenesis in aging patients.

Keywords: Aging, Angiogenesis

Introduction

Perhaps because of its inevitability, aging is the risk factor most likely taken for granted despite its potent impact on cardiovascular disease, which generally outweighs all the other risk factors combined. Yet the obviousness of this association masks a more subtle question: why is aging associated with cardiovascular disease? Clearly one contributor is that aging provides greater cumulative exposure to harmful stimuli such as oxidized lipids or hemodynamic stress. Even here, the exact mechanisms linking such exposures to cardiovascular disease are often incompletely understood. However, recent work suggests pathways and processes intrinsic to the aging process also play important roles in cardiovascular diseases associated with aging. For example, pathways central to vessel formation, such as HIF-1α, PGC-1α, and eNOS, interact with multiple aging-related pathways (Figure 1). These include telomerase, sirtuins, and the p16/p19 regulators of cell senescence. The current review focuses on how aging impairs angiogenesis. Since the elderly are at higher risk for ischemic injury and other diseases where angiogenesis is crucial to the healing response, this impairment increases end-organ damage and contributes to adverse clinical outcomes in the elderly. Thus understanding the mechanisms underlying aging-impaired angiogenesis could have important clinical implications.

Figure 1.

Overview of Angiogenic Pathways. Some of the major pathways regulating angiogenesis are depicted. In response to a range of stimuli (such as hypoxia and exercise), tissue responded with enhanced expression of secreted, angiogenic peptides such as VEGF (intended here to represent the broader family of such peptides). Pathways that are important in aging (such as sirtuins, p16/p19, and telomerase) have important effects on both these angiogenic pathways. The angiogenic peptides act through eNOS-dependent and –independent mechanisms to regulate endothelial growth and chemotaxis to enhance angiogenesis. NO itself regulates some of these processes while also acting on vascular smooth muscle cells to modulate vascular tone and consequently flow which also affects vessel development

Overview of Angiogenesis

Blood vessel growth in the adult is categorized into three related processes. Angiogenesis is the growth of small capillary size vessels1, while arteriogenesis is the growth of larger supplying vessels2. Vasculogenesis refers to the process whereby progenitor cells form vascular structures de novo3. Blood vessel growth occurs in response to both physiological and pathological stimuli1. Physiological angiogenesis occurs in response to exercise to accommodate the increased oxygen and metabolic demands of the active muscle tissue and to supply the hypertrophied muscle4,5. Angiogenesis accompanies both physiological and pathological cardiac hypertrophy, and an imbalance between blood vessel and cardiac muscle growth has been suggested to be a key event leading to cardiac failure6.

Initiation of the angiogenesis and formation of early vascular structures appears dependent on endothelial cells7. The number and functional capacity of circulating endothelial or vascular progenitor cells also appears to influence angiogenesis8, and correlate with vascular outcomes more generally9. The nature and exact roles of circulating progenitors are still being evaluated, and it remains unclear whether they are essential for the angiogenesis or simply a marker of vascular health or regenerative capacity10.

Angiogenesis is also essential for recovery after tissue damage. It occurs in healing wounds, and in combination with arteriogenesis is important in recovery after cardiac and skeletal muscle ischemia. However, angiogenesis can also contribute to pathologic events such as tumor growth and neovessel growth in atherosclerotic plaques11. As discussed below, aged individuals appear to simultaneously have impaired physiological angiogenesis and to be at higher risk for processes associated with pathological vessel formation. Identification of distinct regulatory mechanisms controlling beneficial or physiological angiogenesis and pathological angiogenesis would be of great interest.

Pathways to angiogenesis

Stimuli such as hypoxia or the increased metabolic demands associated with exercise work through multiple pathways to regulate angiogenesis, in many instances through modulation of secreted angiogenic peptides, such as VEGF (Figure 1). Hypoxia increases expression of transcription factors or co-activators such as Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1α (HIF1α) and PCG-1α that in turn induce production of angiogenic growth factors12–14. The responsible mechanisms have perhaps been best elucidated for HIF1α. Hypoxia induces prolyl hydroxylation of HIF1α, which stabilizes the protein15, which translocates to the nucleus inducing transcription of angiogenic growth factors such as VEGF-A13. The transcriptional co-activator, PGC-1α, has been shown recently to mediate a HIF1-independent pathway of angiogenesis that also occurs in response to hypoxia but is regulated at the level of PGC-1α transcription4. Interestingly, PGC-1-driven angiogenesis appears to be particularly important in exercise-induced angiogenesis16. Elucidating exactly how the HIF1- and PGC-1-regulated angiogenic pathways are integrated in different pathophysiological contexts will be of great interest. As noted below, impairment of both these pathways may contribute to reduced angiogenesis in the elderly.

Angiogenesis in the Elderly

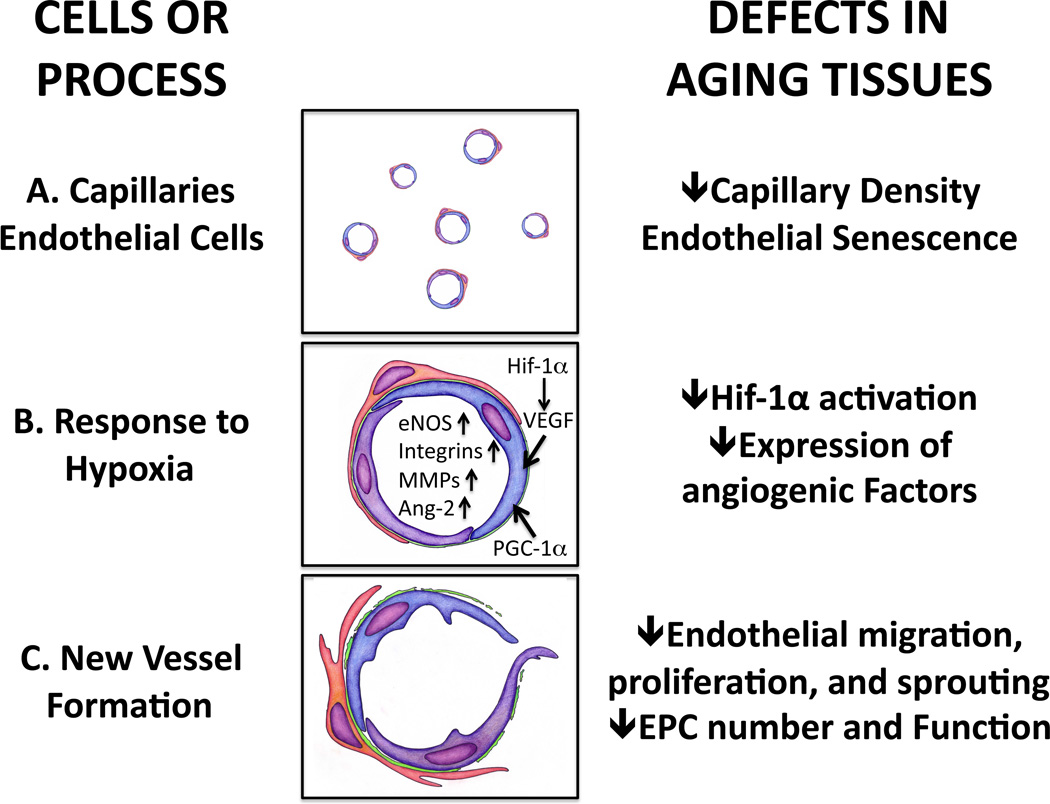

Recovery after ischemia or infarction in any organ requires blood vessel growth17. The incidence of stroke, claudication, and myocardial ischemia or infarction all increase in elderly patients, and they have worse outcomes when ischemia or infarction does occur. For example, after acute limb ischemia, the elderly have both higher mortality and an increased rate of limb amputation18. Elderly patients have reduced capillary density19–21, and reduced angiogenesis in response to ischemia (Figure 2). In addition to reducing the endogenous angiogenic response, aging may also limit the response to exogenous interventions such as the angiogenic growth factors delivered in clinical trials22. While preclinical trials are generally conducted in young and otherwise healthy animals, the clinical targets for such interventions are often elderly patients with multiple co-morbid diseases, many of which further negatively impact vessel formation. This may help explain why promising preclinical results often fail to translate into clinical benefits.

Figure 2.

A schematic representation of normal vascular function and angiogenesis and the effects of aging.) Normal capillary density in young individuals allows dynamic regulation of blood flow according to metabolic needs of the tissue. Aging impairs capillary density as well as flow-mediated vasodilation and eNOS function.) Hypoxia stimulates Hif-1α activation and production of growth factors in ischemic cells. Secreted growth factors form a gradient in ischemic tissues guiding growth of blood vessels. Angiogenic growth factors activate endothelial cells and stimulate production of growth factors, their receptors, matrix metalloproteinases that degrade the capillary basement membrane and extracellular matrix and expression of integrins. VEGF upregulates and activates eNOS leading to vasodilation. Aging impairs HIF1α activation, growth factor production and inhibits matrix metalloproteinase activity by increasing Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinase (TIMP) expression. ROS stress in aging endothelial cells impairs eNOS activation and bioavailability of NO is reduced due to uncoupling of eNOS function and increased destruction of NO.) Endothelial cells proliferate, migrate into extracellular matrix and form vascular structures. Senescent endothelial cells have lower proliferative capacity due to eNOS deficiency, decreased telomerase activity and DNA damage, reduced growth factor production and oxidative stress. Endothelial migration is impaired leading to reduced tube formation. Bone marrow-derived and tissue resident progenitor cells promote angiogenesis by secreting growth factors and by directly incorporating into forming blood vessels. Aging impairs recruitment of progenitor cells from bone marrow and their survival and function. Pericyte function is impaired in aging tissues destabilizing vessels.

Recent evidence suggests multiple pathways can drive blood vessel growth and there may be important differences between angiogenesis that occurs in different contexts. This could help explain apparent discrepancies between the degree of angiogenesis impairment in distinct settings. For example, angiogenesis is impaired in the elderly in response to ischemia or infarction23,24 but may be intact in the response to exercise19,25. Conversely, the elderly are at increased risk for most forms of neoplasia, which often depends on angiogenesis. However, such clinical observations obviously reflect multiple complex processes including those driving tumor formation itself, and some have suggested that reduced angiogenic capacity may actually limit growth of some tumors in the elderly26. Clarifying these issues will ultimately require a deeper understanding of the role of specific angiogenic pathways in each of these settings. Currently, however, it is clear that aging impacts virtually all the angiogenic pathways identified to date.

Intersections between mechanisms of aging and angiogenesis

To a remarkable degree, the pathways integral to aging intersect with and modulate those regulating angiogenesis. One might ask why this should be the case and, of course, it’s impossible to answer such questions definitively. However, from a teleological perspective, it seems likely that angiogenic pathways evolved to support tissues during periods of growth and/or high metabolic demand. Downregulating the growth of blood vessels in less active tissues that are not growing could help match blood supply with metabolic needs. The maladaptive consequences of this overall for an aged individual, particularly in the context of chronic diseases such as atherosclerosis or ischemic injury, would have little influence on reproductive success and therefore not be subject to negative evolutionary selection. Thus it is perhaps not surprising that aging-related pathways have an important impact on angiogenesis.

Cellular senescence

Senescent cells cease to proliferate and undergo other functional changes in association with aging. In senescent endothelial cells, reduced proliferation may limit the capacity to form new vascular structures and decreases in endothelial function may contribute to atherosclerotic plaque formation. Interestingly, initial signs of endothelial senescence can even be found in the young27. The life span and proliferative capacity of endothelial cells can be modified by external stimuli28. Enhancing endothelial proliferation and angiogenesis may provide a therapeutic strategy for ischemic complications of atherosclerosis, but could increase the susceptibility to malignancies.

Specific pathways linked to regulation of cellular senescence include cyclin dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors and regulation of telomere length. These pathways likely interact on multiple levels, and both appear to regulate angiogenesis.

CKD inhibitors

The cyclin dependent kinase inhibitors, p16(Ink4a), p19(Arf), and p21, function upstream of the tumor suppressor gene, p53, among other pathways, and have been implicated in senescence of endothelial cells and endothelial precursor cells29,30. These molecules arrest the cell cycle in G1 preventing replication. Mutations in these genes have been observed in malignancies31. Aging and many known inducers of cellular senescence such as reactive oxygen species increase p16 activity32. Inhibiting p16 and related proteins has been proposed as a strategy to escape cellular senescence and loss of proliferative capacity33. In aging, increased p19(Arf) expression suppresses VEGF-A production34, while exogenous VEGF-A down-regulates p16 and p21, restoring the proliferative capacity of senescent endothelial cells35. In population genetic studies, one of the loci most robustly linked to coronary disease phenotypes is at chromosome 9p21, where p16/19 are the closest expressed sequences36–38. However, whether the 9p21 sequence variants contribute to vascular disease through p16/p19 and/or affecting cellular senescence remains unclear.

Telomere length: Telomeres are chromatin structures at the ends of chromosomes that protect these regions from recombination and degradation. Telomeres get progressively shorter as cells divide, eventually contributing to genomic instability, replicative senescence, and apoptosis39. Telomerase is an enzyme that consists of a RNA component (TERC) and a telomerase reverse transcriptase component (TERT). Its activity elongates telomeric DNA and protects cells from replicative senescence40. In human cells, telomerase activity is high during embryogenesis and in some cells with high proliferative capacity but is low or undetectable in most somatic cells41. Telomere attrition correlates with reduced proliferative capacity in human endothelial cells42,43, and telomere shortening is associated with atherosclerosis44,45. Although the causality of telomere shortening and development of cardiovascular disease has not been established, diminished angiogenic response in TERC-null mice with critically short telomeres suggests that telomere exhaustion may contribute to age-dependent impairment of angiogenesis46. Telomere shortening can also be induced by various cellular insults such as reactive oxygen species47.

Gene transfer of TERT, the reverse transcriptase component of the telomerase, reduces replicative senescence in many cell types including endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells. Ectopic over-expression of TERT was shown to protect human endothelial cells from senescence and maintain their angiogenic phenotype48. TERT expression also improves eNOS function in senescent endothelial cells49. TERT gene transfer has been used to improve the proliferative and migratory capacity of endothelial precursor cells50 and leads to formation of more durable vascular structures in vivo51. Thus impaired telomerase activity and reduced telomere length appear to be important contributors to endothelial senescence and likely impaired angiogenesis in the elderly. Interestingly, telomerase overexpression has been shown to suppress p16 and p21 activity52.

In a fascinating series of experiments, DePinho and colleagues have explored the role of TERT in a variety of aging phenotypes as well as the capacity for TERT expression to rescue these phenotypes53,54. TERT−/− mice were intercrossed producing generations of telomerase deficient mice with progressive reductions in telomere length. While the first intercrossed generation had largely intact telomeres, the fourth generation of intercrossed TERT−/− mice had severe telomere dysfunction54. Interestingly, these mice developed multisystem organ dysfunction, including spontaneous cardiomyopathy54. Network analyses revealed profound repression of PGC-1α- and β-dependent gene expression. As noted elsewhere, PGCs play an important role in angiogenesis and it is tempting to speculate that this may contribute to the phenotypes observed. However, PGC-1α is also crucial to cardiac mitochondrial biogenesis and maintenance of cardiac function under stressed conditions55,56. The more severe phenotype observed in the fourth generation TERT−/− than PGC-1α−/− mice may reflect the additional p53-dependent pathways being activated in this setting54.

In separate experiments, DePinho and colleagues engineered mice with tamoxifen-inducible TERT fused to the mutant estrogen receptor (mER) under the transcriptional control of the endogenous TERT promoter. In the absence of tamoxifen TERT-mER is inactive and homozygous mice have short, dysfunctional telomeres and progressive end-organ degeneration53, similar to the TERT−/− mice54. Tamoxifen treatment of TERT-mER mice induced TERT reactivation which reduced DNA damage and eliminated degenerative phenotypes in many organs53. Cardiovascular phenotypes at baseline or in response to TERT activation have not yet been reported in this model but will be of great interest.

In addition to the cell autonomous effects of senescence, the presence of senescent cells appears to have broader negative effects contributing to organ dysfunction in aging. Van Deursen and colleagues engineered a genetic mouse model called INK-ATTAC that enabled them to remove senescent p16(Ink4a)-expressing cells in response to treatment with a specific drug57. They used this model in combination with mice hypomorphic BubR1, a component of the mitotic checkpoint, which have a premature aging phenotype and shortened lifespans58. Of note, the BubR1 hypomorphs have vascular phenotypes similar to those associated with aging in humans including arterial thinning with fibrosis as well as impaired vasodilation and NOS activity consistent with endothelial dysfunction59. Removal of senescent cells from the BubR1 hypomorphs delayed onset and progression of age-related phenotypes in multiple tissues including adipose, skeletal muscle, and eye57. This suggests senescent cells are causally involved in the development of aging-associated tissue dysfunction, and their adverse effects extend beyond dysfunction of the senescent cells themselves.

Oxidative stress

Oxidative stress is increased in aging, which is associated with increases in oxidatively damaged proteins, lipids and DNA (reviewed in60). Multiple mechanisms contribute to the increase in oxidative stress seen in aging including increased production and imbalances in endogenous antioxidant/oxidant pathways. Mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species is increased in aging animals61, which may reflect mitochondrial dysfunction from multiple causes including age-related accumulation of mitochondrial mutations62.

Oxidative stress affects blood vessel growth on multiple levels. Redox imbalance can lead to both telomere-dependent and -independent cellular senescence, reducing proliferative capacity and altering endothelial cell function. Superoxide, the initial oxygen free radical generated by mitochondria, inhibits angiogenesis through multiple mechanisms, including acting as a nitric oxide (NO) scavenger and inhibiting eNOS activity (reviewed in63). Thus increased superoxide in aged endothelium impairs both endothelium-dependent vasodilation64 and collateral vessel formation65. Thus as noted at multiple other points in this review, eNOS acts as a central integrator of signaling pathways related to aging and angiogenesis, as well as atherosclerosis (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

eNOS has a central role in vascular function and angiogenesis. Shear stress, VEGF, estrogen and increase in intracellular calcium concentration stimulate eNOS activation in healthy endothelial cells. eNOS plays multiple functions in blood vessel function and angiogenesis. eNOS is an important mediator of endothelial cell proliferation, recruitment and function of endothelial progenitor cells, mediator of endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation and inhibitor of platelet aggregation. In addition, eNOS has been shown to play a role in induction of telomerase activity and mitochondrial biogenesis. Aging reduces eNOS expression, activation and NO bioavailability. Reduced telomerase activity, SIRT1 expression, reduced estrogen stimulation and oxidative stress contribute to eNOS dysfunction.

Reactive oxygen species generated by the NADPH family of oxidases also modulate cell signaling and appear necessary for VEGF-induced angiogenesis66–68. However, excessive production of ROS inhibits endothelial cell proliferation69. In some settings, ROS can induce hyperstimulation of endothelial cells by inducing VEGF production and amplifying its intracellular effects by increasing expression of its downstream signaling targets, increasing phoshorylation of Akt and eNOS68. For example, in a model of prohibitin-1 deficiency, ROS stress was shown to lead to hyperactivation of Akt and Rac1 leading to cytoskeletal rearrangements and decreased endothelial cell migration and endothelial tube formation and in vivo angiogenesis70. Oxidative stress decreased telomerase activity and increased telomere erosion and the premature onset of replicative senescence in human endothelial cells71.

Antioxidants have demonstrated beneficial effects in a variety of experimental models although clinical trials exploiting this approach in cardiovascular disease have been universally negative72,73. Thioredoxin overexpression in the mitochondria of endothelial cells has been shown to improve endothelial cell function and reduce atherosclerosis74. ROS scavenging has also been used as a strategy to prevent telomere-dependent cellular senescence. Asc2P, an oxidation-resistant form of vitamin C, was shown to slow down telomere shortening and extend the lifespan of endothelial cells in vitro75. Treatment of endothelial cells with the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine delays replicative senescence by inhibiting TERT nuclear export and preserving TERT activity76. Aspirin may also have antioxidant effects that mitigate telomerase downregulation77, in addition to its well-recognized effects on prostaglandin synthesis and platelets. In humans, vitamin C has been shown to reverse the attenuation of vascular reactivity induced by angiotensin II78, although it has not been demonstrated to improve cardiovascular outcomes. Genetic deletion of p66shc, a cytoplasmic signal transducer involved in the transmission of mitogenic signals from activated receptors to Ras, protects cells from oxidative stress and extends life span in mice79. Interestingly, SIRT1 represses p66shc expression80. Deletion of p66shc also protects against aging-related vascular dysfunction81 and atherosclerosis82. Once again, regulation of eNOS activation appears to play an important role in these effects83. Together these data support a role for aging-related oxidative stress in impaired vascular function and angiogenesis in the elderly. However, it should be noted that these data come from experimental models and thus far have failed to translated into clinically effective therapeutic strategies72,73.

Nitric oxide

Nitric oxide (NO) is an essential mediator of blood vessel reactivity and angiogenesis (Figure 3). It regulates both the endogenous angiogenic response to ischemia and angiogenesis induced by exogenously administered VEGF-A84,85, and is involved in endothelial progenitor cell (EPC) mobilization and function86. In normal blood vessels, shear stress is an important stimulus for NO production by endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) in endothelial cells87. Although initially discovered because of its endothelial-dependent induction of vasodilation through its effects the underlying smooth muscle cell layer, NO has many important functions in the vasculature. It affects telomerase activity88, inhibits platelet aggregation, and suppresses smooth muscle cell proliferation89. Reduced NO has also been suggested to enhance sensitivity to apoptotic stimuli in endothelial cells85.

In healthy endothelial cells, NO is produced by eNOS while inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) is activated in a variety of pathological conditions90. Many molecules along the complex process of eNOS activation and NO production91 are affected by aging and oxidative stress. eNOS protein expression is reduced92 and activation by cellular localization, binding to intracellular activating proteins93, dimerization94 and phosphorylation93,95, 96 are all decreased in aging cells leading to reduced production of NO.

Redox imbalance in aging endothelial cells can lead to uncoupling of eNOS function97,98. In an oxidative environment, NO can form peroxynitrite from its reaction with superoxide anion and further increase oxidative stress99,100. Tetrahydrobiopterin, a cofactor for eNOS, is reduced in aged endothelium which may further reduce NO relative to superoxide anion101, contributing to endothelial dysfunction and reduced vascular reactivity. In addition, compensatory upregulation of iNOS in senescent cells may further increase ROS production102. The central role of eNOS and NO in regulation of endothelial function and angiogenesis underscores the importance of all these adverse effects of aging (Figure 3).

HIF1α

As noted, ischemia-induced angiogenesis is impaired in aging103,104. It seems likely that impaired HIF1α activity is an important contributor to this, although the precise mechanisms are complex and incompletely understood. Exogenous HIF1α delivery is being explored as a therapeutic strategy for ischemia105, underscoring the importance of understanding aging-associated changes in this pathway. In mice, adenoviral expression of constitutively active HIF1α improved perfusion after ischemia in older animals to levels similar to those in young mice, suggesting the downstream mechanisms are intact in aging animals106. Interesting, exercise appears to restore HIF1α activity and ischemia-induced neovascularization in aged animals through a PI3-kinase-dependent mechanism107. In sedentary animals, multiple mechanisms likely contribute to reduced HIF1α activity in aging tissues. Increased endogenous glucocorticoid levels have been shown to decrease the transcription of HIF1α108. Importin-1α levels are also decreased leading to decreased nuclear transport of HIF1α104. The role of SIRT1 in this context is complex. HIF1α is deacetylated and inactivated by SIRT1109. Hypoxia leads to downregulation of SIRT1, providing another mechanism for enhancing HIF1 activity in this setting109. Based on this alone, one might expect that aging-associated decreases in SIRT1 would paradoxically enhance angiogenesis. As discussed below, we do not have a direct experimental answer to this question. However, it is important to keep in mind that the final role of SIRT1 reflects the potentially distinct effects of multiple SIRT1 targets (including eNOS) in different cell lineages. Thus while reduced HIF1α activity is likely a contributor to impaired angiogenesis in aging, an integrated model of the roles of HIF-1-dependent and –independent pathways in distinct contexts (ischemia, exercise, neoplasia) will ultimately be required to resolve some of these apparent discrepancies.

Reduced production or response to vascular growth factors

Vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A) is required for embryonic blood vessel growth and is a major regulator of both physiological and pathological angiogenesis in adult tissues110. VEGF-A has also been shown to be essential for exercise-induced angiogenesis in skeletal muscle111. VEGF production is reduced in aged animals and expression levels of VEGF receptors are lower112. In humans, VEGF mRNA and protein levels are lower in aged individuals at baseline, after exercise113 and after ischemia in comparison to younger controls114. Several other growth factor pathways have also been shown to be impaired in senescent endothelial cells including expression of Platelet-Derived Growth Factor (PDGF)115 and the response to basic Fibroblast Growth Factor bFGF116. Although the levels of angiopoietin-1 and -2 are unchanged, Tie-2 receptor expression appears be decreased in aging skeletal muscles112. Impaired HIF1α activation is likely the main reason for reduced VEGF expression while mechanisms underlying altered expression of other growth factors are largely unknown.

While the growth factor response to ischemia seems to be impaired, exercise induces apparently normal or even enhanced growth factor production in aging tissues. Swimming increases VEGF, Flt-1 and Flk-1 levels and increase capillary density in aged rat myocardium similar to young controls117. Prior exercise improves recovery after hind limb ischemia in old rats by increasing HIF1α and VEGF-A expression leading to increase in capillary density in the ischemic limb118.

Sirtuins

Sirtuins (SIRT1-7) are nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+)-dependent histone deacetylases originally identified as important contributors to the extended lifespan seen with caloric restriction. There are seven mammalian homologues of the yeast gene originally identified and sirtuins have been implicated in a wide variety of important biological processes from cellular stress resistance and genomic stability to energy metabolism119,120. Sirtuin over-expression or small molecule activators prolong the life span of several species121–125. Although some of the earliest results have recently been questioned126, a robust literature points to important effects of sirtuins in mammalian biology and pathophysiology119,120, 123 as well as their beneficial effects in cardiovascular disease and inflammation127. Sirtuins function as cellular sensors of redox imbalance by sensing NAD+/NADH balance. Caloric restriction and exercise increase this ratio and activate SIRT1 while hypoxia down-regulates its activity, and inversely, in oxidative stress SIRT1 inactivates HIF1α109, which may be beneficial in cancer but could be maladaptive in ischemic injury.

SIRT1 has been shown to have direct effects on endothelial cells and blood vessel growth. Loss of SIRT1 leads to premature endothelial cell senescence in vitro while its over-expression protected cells from senescence-associated morphological and molecular changes128. Caloric restriction induces eNOS expression, which appears required for induction of mitochondrial biogenesis and SIRT1 expression129. SIRT1, in turn, deacetylates and activates eNOS130, providing a positive feedback loop linking SIRT1 and eNOS, a central regulator of both angiogenesis and atherosclerosis. Consistent with this, endothelial-specific overexpression of SIRT1 mitigates atherogenesis in ApoE−/− mice131. In contrast, more general SIRT1 overexpression was reported to worsen atherosclerosis in LDLR−/− mice through effects on hepatic lipid metabolism132, suggesting the atherogenic lipid profile overcomes the protective effects of endothelial SIRT1 expression. Although angiogenesis was not examined in these studies, it might well parallel the observed changes in atherosclerosis. Taken together, these studies suggest sirtuins provide an important link between intrinsic mechanisms of aging and impaired angiogenesis.

Systemic factors

Although this review focuses on the processes and pathways intrinsic to vascular cells that impair angiogenesis in the elderly, systemic factors also play an important role in this context. Although beyond the scope of this review, established risk factors for vascular disease including hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, smoking, and hypertension all have adverse effects on endothelial or progenitor cell function, and angiogenesis, independent of aging133–135. It seems likely that in the context of aging negative synergy between these factors and the considerations discussed earlier further compromise angiogenesis. Hemodynamic influences are also important in angiogenesis particularly after the initial formation of neovessels. Blood flow is required for vessel lumen formation and recruitment of perivascular cells and subsequent secretion of basement membrane and vessel stabilization. The expanding microvascular bed decreases blood pressure downstream leading to increased blood flow. The diminished vascular reactivity seen commonly in the elderly and in disease states in larger upstream arteries may further compromise angiogenesis by reducing flow-mediated stabilization and result in decreased microvessel density.

Endocrinological changes seen in aging are also important modulators of angiogenesis. Important changes include reductions in growth hormone and IGF-1, and estrogens, that may further impair the regenerative capacity of the cardiovascular system136. Endogenous production of glucocorticoids is increased 20–50% in aging individuals due to blunting of the glucocorticoid feedback inhibition of ACTH, and has been shown to inhibit angiogenesis108. Menopause results in a dramatic increase in cardiovascular disease risk in women. Estrogen has been shown to be involved in virtually every aspect of the angiogenesis process. Estrogen maintains and stimulates nitric oxide production137 mitigating endothelial dysfunction138. Estrogen increases telomerase activity protecting both endothelial and smooth muscle cells as well as endothelial progenitor cells from senescence139,140, promotes EPC migration and proliferative capacity141 and protects EPCs from angiotensin II-induced oxidative damage142. Estrogen induces telomerase activity by activating the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway and stimulating nitric oxide production in endothelial cells143. Androgens have also been shown to stimulate VEGF production and induce angiogenesis by stimulating erythropoietin production144. However, it is worth noting that randomized controlled trials of hormone-replacement therapy in post-menopausal women have not demonstrated the expected reduction in cardiovascular events and in some cases appear to increase adverse outcomes145. Interestingly subgroup analyses suggest the effects may vary with age of the recipient146.

Therapeutic implications

As many have noted, aging is generally considered preferable to the most obvious alternative. However, new insights into general mechanisms of aging or specific links between aging and vascular health could provide opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Clinically this possibility will only become more important as populations age.

In the context of angiogenesis, some of the potential therapeutic targets are not specific to aging. For example, as alluded to throughout the text, nitric oxide synthesis lies at the intersection of many important endothelial functions that are impaired both with aging and disease (Figure 3) and thus presents an attractive target for intervention147. Exogenous eNOS over-expression restores vascular reactivity148 and enhances angiogenesis149. However a variety of technical challenges currently limit the clinical applicability of vascular gene therapy approaches. Several molecules related to eNOS activation and NO production have been shown to increase NO production and can be administered systemically. Statins increase NO both through increasing tetrahydrobiopterin, a cofactor for production of NO by nitric oxide synthases150 and through activation of the serine-threonine kinase, Akt, which phosphorylates and activation eNOS151. Dietary supplementation with L-arginine, the substrate for NO synthesis, rescues the angiogenic response in hypercholesterolemic animals152 and nitrite supplementation in drinking water was shown to prevent endothelial dysfunction in aged mice153. Scavenging peroxynitrite by antioxidant ebselen was able to both prevent and reverse endothelial cell senescence in vitro154. Physical exercise has been shown to improve vascular reactivity and to prevent eNOS uncoupling by inducing endogenous tetrahydrobiopterin97, increasing activating eNOS phosphorylation (Ser1177) and decreasing inactivating phosphorylation (Thr495)155.

Exogenous delivery of angiogenic agents could circumvent the diminished molecular response to ischemia in aged individuals. Administration of exogenous VEGF-A protein or transcriptional activation of VEGF-A restored angiogenesis in old animals23,156, 157. In addition to enhancing sprouting angiogenesis, VEGF treatment has other beneficial effects in aging tissues. Pretreatment with a combination of growth factors including PDGF-AB, Angiopoietin-1 and VEGF improved the EPC-mediated vasculogenic responses in aged mice115. VEGF delivery also increases expression of TERT in a nitric oxide dependent mechanism possibly enhancing the proliferative capacity of endothelial cells158. High doses of exogenously delivered growth factors may also overcome other aging-related pathological conditions limiting endogenous blood vessel growth such as diabetes and hypercholesterolemia159. Unfortunately, clinical results based on growth factor delivery have been disappointing160–162. In part, these results may reflect the challenges of extrapolating from experiments generally performed in young, healthy animals to clinical trials in elderly patients with multiple other risk factors and comorbid diseases that impair angiogenic capacity133. Of course, other considerations including choice of growth factor(s), therapeutic agent (protein vs. viral vector), and delivery methods (intravenous vs. direct intramuscular injection) are likely also important163.

As noted above, sirtuin activators are being pursued in a variety of systemic diseases and there is reason to believe they may enhance function of endothelial cells and might prove a useful adjunct to enhance angiogenesis in the elderly.

In the meantime, minimizing exposures to injurious stimuli through appropriate lifestyle choices are an important avenue of mitigating risk and enhancing angiogenesis. In some cases, these may also have aging-related mechanisms that contribute. For example, smoking and obesity correlate with shorter telomeres while moderate exercise appears to protect from telomere-dependent cellular aging164–166. In fact, exercise has been shown to enhance virtually all of the steps impaired in angiogenesis in the elderly through a variety of mechanisms providing one more rationale to encourage continued exercise training in patients generally and the aged in particular (Table).

Table.

Beneficial effects of exercise related to angiogenesis

| Vascular reactivity | Increased flow-mediated vasodilation, eNOS/NO production | Luk (2011)167 Sindler (2009)97 Calvert (2011)155 |

| Activation of angiogenesis | Increased HIF1α, PGC-1α, VEGF | Cheng (2010)107 Iemitsu (2006)117 Leosco (2007)118 |

| Cellular senescence | Decreased p16/p19 Increased telomerase activity |

Song (2010)164 Puterman (2010)165 Ludlow (2008)166 |

| Progenitor cells | Increased Mobilization Improved Function |

Schlager (2011)168 Van Craenenbroeck (2010)169 |

| Oxidative stress | Reduced | Pierce (2011)181 |

Exercise mitigates many of the aging-related molecular defects seen in endothelial cells and angiogenesis.

Concluding remarks

A variety of systemic and intrinsic changes seen with aging limit vascular homeostasis and angiogenesis in the elderly. These changes should be considered when designing therapeutic strategies for cardiovascular diseases. Lower basal capillary density in aged tissues and diminished vascular reactivity predispose tissues to ischemia, and reduced responsiveness to angiogenic stimuli and proliferative capacity of endothelial cells pose limitations to tissue recovery and repair. Current treatment strategies focus on mitigating the effects of established vascular risk factors but ongoing research may yield approaches specifically targeting pathways intrinsic to aging with an impact on angiogenesis.

Acknowledgment

Sources of Funding:

This work was supported in part by grants from the NIH (AR), a Leducq Foundation Network of Research Excellence (AR), and a Leducq Foundation Career Development Award (JL).

Nonstandard Abbreviations

- ACTH

Adrenocorticotropic hormone

- Asc2P

ascorbic acid 2-phosphate

- Akt

serine-threonine kinase also known as Protein Kinase B

- bFGF

Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor

- CDK

cyclin dependent kinase

- DNA

deoxyribonucleic acid

- eNOS

endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase

- EPC

Endothelial Progenitor Cell

- Flk-1

Fetal Liver Kinase 1 also known as vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGFR-2)

- Flt-1

fms-related tyrosine kinase 1, also known as vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 (VEGFR-1)

- Hif-1α

Hypoxia Inducible Factor -1 alpha

- IGF

Insulin-like Growth Factor

- iNOS

Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase

- mRNA

messenger ribonucleic acid

- NADP(H)

Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate

- NO

Nitric Oxide

- PGC-1α

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha

- PDGF

Platelet Derived Growth Factor

- p16(ink4a)

Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A

- p19(Arf)

Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A

- p21

(Cdc42/Rac)-activated kinase 3

- p53

tumor protein 53

- p66shc

Src homology 2 domain-containing-transforming protein C1A

- Rac1

Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1

- Ras

'Rat sarcoma', a family of small GTPase proteins

- ROS

Reactive Oxygen Species

- SIRT1-7

family of sirtuin homologs for the yeast Sir2 (silent mating type information regulation 2) gene

- TERC

telomerase RNA component

- TERT

telomerase reverse transcriptase

- Tie-2

TEK tyrosine kinase endothelial-2

- VEGF-A

Vascular Endothelial Factor-A

- VEGF-D

Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor-D

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: None

References

- 1.Carmeliet P. Angiogenesis in health and disease. Nat Med. 2003;9:653–660. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scholz D, Cai W, Schaper W. Arteriogenesis, a new concept of vascular adaptation in occlusive disease. Angiogenesis. 2001;4:247–257. doi: 10.1023/a:1016094004084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jin S, Patterson C. The opening act: Vasculogenesis and the origins of circulation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:623–629. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.161539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arany Z, Foo S, Ma Y, Ruas J, Bommi-Reddy A, Girnun G, Cooper M, Laznik D, Chinsomboon J, Rangwala S, Baek K, Rosenzweig A, Spiegelman B. Hif-independent regulation of vegf and angiogenesis by the transcriptional coactivator pgc-1alpha. Nature. 2008;451:1008–1012. doi: 10.1038/nature06613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yan Z, Okutsu M, Akhtar Y, Lira V. Regulation of exercise-induced fiber type transformation, mitochondrial biogenesis, and angiogenesis in skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol. 2011;110:264–274. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00993.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Isner J, Losordo D. Therapeutic angiogenesis for heart failure. Nat Med. 1999;5:491–492. doi: 10.1038/8374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eilken H, Adams R. Dynamics of endothelial cell behavior in sprouting angiogenesis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:617–625. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ballard VLT, Edelberg JM. Stem cells and the regeneration of the aging cardiovascular system. Circulation Research. 2007;100:1116–1127. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000261964.19115.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirton J, Xu Q. Endothelial precursors in vascular repair. Microvasc Res. 2010;79:193–199. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosenzweig A. Circulating endothelial progenitors--cells as biomarkers. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1055–1057. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe058134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khurana R, Simons M, Martin J, Zachary I. Role of angiogenesis in cardiovascular disease: A critical appraisal. Circulation. 2005;112:1813–1824. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.535294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fong G. Mechanisms of adaptive angiogenesis to tissue hypoxia. Angiogenesis. 2008;11:121–140. doi: 10.1007/s10456-008-9107-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pugh C, Ratcliffe P. Regulation of angiogenesis by hypoxia: Role of the hif system. Nat Med. 2003;9:677–684. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee S, Wolf P, Escudero R, Deutsch R, Jamieson S, Thistlethwaite P. Early expression of angiogenesis factors in acute myocardial ischemia and infarction. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:626–633. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003023420904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Safran M, Kaelin WJ. Hif hydroxylation and the mammalian oxygen-sensing pathway. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:779–783. doi: 10.1172/JCI18181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chinsomboon J, Ruas J, Gupta R, Thom R, Shoag J, Rowe G, Sawada N, Raghuram S, Arany Z. The transcriptional coactivator pgc-1alpha mediates exercise-induced angiogenesis in skeletal muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:21401–21406. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909131106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carmeliet P, Jain R. Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of angiogenesis. Nature. 2011;473:298–307. doi: 10.1038/nature10144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ouriel K, Veith F. Acute lower limb ischemia: Determinants of outcome. Surgery. 1998;124:336–341. discussion 341-332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gavin TP, Ruster RS, Carrithers JA, Zwetsloot KA, Kraus RM, Evans CA, Knapp DJ, Drew JL, McCartney JS, Garry JP, Hickner RC. No difference in the skeletal muscle angiogenic response to aerobic exercise training between young and aged men. The Journal of Physiology. 2007;585:231–239. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.143198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parizkova J, Eiselt E, Sprynarova S, Wachtlova M. Body composition, aerobic capacity, and density of muscle capillaries in young and old men. J Appl Physiol. 1971;31:323–325. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1971.31.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coggan A, Spina R, King D, Rogers M, Brown M, Nemeth P, Holloszy J. Skeletal muscle adaptations to endurance training in 60- to 70-yr-old men and women. J Appl Physiol. 1992;72:1780–1786. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.72.5.1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gupta R, Tongers J, Losordo D. Human studies of angiogenic gene therapy. Circ Res. 2009;105:724–736. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.200386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rivard A, Fabre JE, Silver M, Chen D, Murohara T, Kearney M, Magner M, Asahara T, Isner JM. Age-dependent impairment of angiogenesis. Circulation. 1999;99:111–120. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Swift M, Kleinman H, DiPietro L. Impaired wound repair and delayed angiogenesis in aged mice. Lab Invest. 1999;79:1479–1487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rossiter HB. Age is no barrier to muscle structural, biochemical and angiogenic adaptations to training up to 24 months in female rats. The Journal of Physiology. 2005;565:993–1005. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.080663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pili R, Guo Y, Chang J, Nakanishi H, Martin G, Passaniti A. Altered angiogenesis underlying age-dependent changes in tumor growth. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:1303–1314. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.17.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gates P, Strain W, Shore A. Human endothelial function and microvascular ageing. Exp Physiol. 2009;94:311–316. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2008.043349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Freedman D. Senescence and its bypass in the vascular endothelium. Front Biosci. 2005;10:940–950. doi: 10.2741/1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Collins C, Sedivy J. Involvement of the ink4a/arf gene locus in senescence. Aging Cell. 2003;2:145–150. doi: 10.1046/j.1474-9728.2003.00048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang D, Liu L, Zheng X. Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p16(ink4a) and telomerase may co-modulate endothelial progenitor cells senescence. Ageing Res Rev. 2008;7:137–146. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lundberg A, Hahn W, Gupta P, Weinberg R. Genes involved in senescence and immortalization. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2000;12:705–709. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00155-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dai J, Zhu X, Yoder M, Wu Y, Colman R. Cleaved high-molecular-weight kininogen accelerates the onset of endothelial progenitor cell senescence by induction of reactive oxygen species. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:883–889. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.222430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huschtscha L, Reddel R. P16(ink4a) and the control of cellular proliferative life span. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20:921–926. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.6.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kawagishi H, Nakamura H, Maruyama M, Mizutani S, Sugimoto K, Takagi M, Sugimoto M. Arf suppresses tumor angiogenesis through translational control of vegfa mrna. Cancer Res. 2010;70:4749–4758. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watanabe Y, Lee S, Detmar M, Ajioka I, Dvorak H. Vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor (vpf/vegf) delays and induces escape from senescence in human dermal microvascular endothelial cells. Oncogene. 1997;14:2025–2032. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Samani NJ, Erdmann J, Hall AS, Hengstenberg C, Mangino M, Mayer B, Dixon RJ, Meitinger T, Braund P, Wichmann HE, Barrett JH, Konig IR, Stevens SE, Szymczak S, Tregouet DA, Iles MM, Pahlke F, Pollard H, Lieb W, Cambien F, Fischer M, Ouwehand W, Blankenberg S, Balmforth AJ, Baessler A, Ball SG, Strom TM, Braenne I, Gieger C, Deloukas P, Tobin MD, Ziegler A, Thompson JR, Schunkert H. Genomewide association analysis of coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:443–453. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Helgadottir A, Thorleifsson G, Manolescu A, Gretarsdottir S, Blondal T, Jonasdottir A, Jonasdottir A, Sigurdsson A, Baker A, Palsson A, Masson G, Gudbjartsson D, Magnusson K, Andersen K, Levey A, Backman V, Matthiasdottir S, Jonsdottir T, Palsson S, Einarsdottir H, Gunnarsdottir S, Gylfason A, Vaccarino V, Hooper W, Reilly M, Granger C, Austin H, Rader D, Shah S, Quyyumi A, Gulcher J, Thorgeirsson G, Thorsteinsdottir U, Kong A, Stefansson K. A common variant on chromosome 9p21 affects the risk of myocardial infarction. Science. 2007;316:1491–1493. doi: 10.1126/science.1142842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McPherson R. Chromosome 9p21 and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1736–1737. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr1002359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fuster JJ, Andres V. Telomere biology and cardiovascular disease. Circulation Research. 2006;99:1167–1180. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000251281.00845.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blasco M. Telomeres and human disease: Ageing, cancer and beyond. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:611–622. doi: 10.1038/nrg1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chiu C, Dragowska W, Kim N, Vaziri H, Yui J, Thomas T, Harley C, Lansdorp P. Differential expression of telomerase activity in hematopoietic progenitors from adult human bone marrow. Stem Cells. 1996;14:239–248. doi: 10.1002/stem.140239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chang E, Harley C. Telomere length and replicative aging in human vascular tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:11190–11194. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.11190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hastings R, Qureshi M, Verma R, Lacy P, Williams B. Telomere attrition and accumulation of senescent cells in cultured human endothelial cells. Cell Prolif. 2004;37:317–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2004.00315.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Samani N, Boultby R, Butler R, Thompson J, Goodall A. Telomere shortening in atherosclerosis. Lancet. 2001;358:472–473. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05633-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Minamino T, Miyauchi H, Yoshida T, Ishida Y, Yoshida H, Komuro I. Endothelial cell senescence in human atherosclerosis: Role of telomere in endothelial dysfunction. Circulation. 2002;105:1541–1544. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000013836.85741.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Franco S, Segura I, Riese H, Blasco M. Decreased b16f10 melanoma growth and impaired vascularization in telomerase-deficient mice with critically short telomeres. Cancer Res. 2002;62:552–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Erusalimsky J, Skene C. Mechanisms of endothelial senescence. Exp Physiol. 2009;94:299–304. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2008.043133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang J, Chang E, Cherry A, Bangs C, Oei Y, Bodnar A, Bronstein A, Chiu C, Herron G. Human endothelial cell life extension by telomerase expression. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:26141–26148. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.37.26141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Matsushita H, Chang E, Glassford A, Cooke J, Chiu C, Tsao P. Enos activity is reduced in senescent human endothelial cells: Preservation by htert immortalization. Circ Res. 2001;89:793–798. doi: 10.1161/hh2101.098443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Murasawa S, Llevadot J, Silver M, Isner J, Losordo D, Asahara T. Constitutive human telomerase reverse transcriptase expression enhances regenerative properties of endothelial progenitor cells. Circulation. 2002;106:1133–1139. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000027584.85865.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang J, Nagavarapu U, Relloma K, Sjaastad M, Moss W, Passaniti A, Herron G. Telomerized human microvasculature is functional in vivo. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:219–224. doi: 10.1038/85655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Veitonmaki N, Fuxe J, Hultdin M, Roos G, Pettersson R, Cao Y. Immortalization of bovine capillary endothelial cells by htert alone involves inactivation of endogenous p16ink4a/prb. FASEB J. 2003;17:764–766. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0599fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jaskelioff M, Muller FL, Paik J-H, Thomas E, Jiang S, Adams AC, Sahin E, Kost-Alimova M, Protopopov A, Cadiñanos J, Horner JW, Maratos-Flier E, DePinho RA. Telomerase reactivation reverses tissue degeneration in aged telomerase-deficient mice. Nature. 2011;469:102–106. doi: 10.1038/nature09603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sahin E, Colla S, Liesa M, Moslehi J, Müller FL, Guo M, Cooper M, Kotton D, Fabian AJ, Walkey C, Maser RS, Tonon G, Foerster F, Xiong R, Wang YA, Shukla SA, Jaskelioff M, Martin ES, Heffernan TP, Protopopov A, Ivanova E, Mahoney JE, Kost-Alimova M, Perry SR, Bronson R, Liao R, Mulligan R, Shirihai OS, Chin L, DePinho RA. Telomere dysfunction induces metabolic and mitochondrial compromise. Nature. 2011;470:359–365. doi: 10.1038/nature09787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Arany Z, He H, Lin J, Hoyer K, Handschin C, Toka O, Ahmad F, Matsui T, Chin S, Wu PH, Rybkin II, Shelton JM, Manieri M, Cinti S, Schoen FJ, Bassel-Duby R, Rosenzweig A, Ingwall JS, Spiegelman BM. Transcriptional coactivator pgc-1 alpha controls the energy state and contractile function of cardiac muscle. Cell Metab. 2005;1:259–271. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Arany Z, Novikov M, Chin S, Ma Y, Rosenzweig A, Spiegelman BM. Transverse aortic constriction leads to accelerated heart failure in mice lacking ppar-gamma coactivator 1alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:10086–10091. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603615103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Baker DJ, Wijshake T, Tchkonia T, LeBrasseur NK, Childs BG, van de Sluis B, Kirkland JL, van Deursen JM. Clearance of p16ink4a-positive senescent cells delays ageing-associated disorders. Nature. 2011;479:232–236. doi: 10.1038/nature10600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baker DJ, Jeganathan KB, Cameron JD, Thompson M, Juneja S, Kopecka A, Kumar R, Jenkins RB, de Groen PC, Roche P, van Deursen JM. Bubr1 insufficiency causes early onset of aging-associated phenotypes and infertility in mice. Nat Genet. 2004;36:744–749. doi: 10.1038/ng1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Matsumoto T, Baker DJ, d'Uscio LV, Mozammel G, Katusic ZS, van Deursen JM. Aging-associated vascular phenotype in mutant mice with low levels of bubr1. Stroke. 2007;38:1050–1056. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000257967.86132.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Muller FL, Lustgarten MS, Jang Y, Richardson A, Van Remmen H. Trends in oxidative aging theories. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43:477–503. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sohal RS, Sohal BH. Hydrogen peroxide release by mitochondria increases during aging. Mech Ageing Dev. 1991;57:187–202. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(91)90034-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee HC, Chang CM, Chi CW. Somatic mutations of mitochondrial DNA in aging and cancer progression. Ageing Res Rev. 2010;9(Suppl 1):S47–S58. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Giacco F, Brownlee M. Oxidative stress and diabetic complications. Circ Res. 2010;107:1058–1070. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.223545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Csiszar A, Ungvari Z, Edwards J, Kaminski P, Wolin M, Koller A, Kaley G. Aging-induced phenotypic changes and oxidative stress impair coronary arteriolar function. Circ Res. 2002;90:1159–1166. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000020401.61826.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Carrao AC, Chilian WM, Yun J, Kolz C, Rocic P, Lehmann K, van den Wijngaard JP, van Horssen P, Spaan JA, Ohanyan V, Pung YF, Buschmann I. Stimulation of coronary collateral growth by granulocyte stimulating factor: Role of reactive oxygen species. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:1817–1822. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.186445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ushio-Fukai M, Tang Y, Fukai T, Dikalov SI, Ma Y, Fujimoto M, Quinn MT, Pagano PJ, Johnson C, Alexander RW. Novel role of gp91(phox)-containing nad(p)h oxidase in vascular endothelial growth factor-induced signaling and angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2002;91:1160–1167. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000046227.65158.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tojo T, Ushio-Fukai M, Yamaoka-Tojo M, Ikeda S, Patrushev N, Alexander RW. Role of gp91phox (nox2)-containing nad(p)h oxidase in angiogenesis in response to hindlimb ischemia. Circulation. 2005;111:2347–2355. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000164261.62586.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ushio-Fukai M, Alexander RW. Reactive oxygen species as mediators of angiogenesis signaling: Role of nad(p)h oxidase. Mol Cell Biochem. 2004;264:85–97. doi: 10.1023/b:mcbi.0000044378.09409.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zanetti M, Zwacka R, Engelhardt J, Katusic Z, O'Brien T. Superoxide anions and endothelial cell proliferation in normoglycemia and hyperglycemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:195–200. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.21.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.CAI H. Hydrogen peroxide regulation of endothelial function: Origins, mechanisms, and consequences. Cardiovascular Research. 2005;68:26–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kurz D, Decary S, Hong Y, Trivier E, Akhmedov A, Erusalimsky J. Chronic oxidative stress compromises telomere integrity and accelerates the onset of senescence in human endothelial cells. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:2417–2426. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yusuf S, Dagenais G, Pogue J, Bosch J, Sleight P. Vitamin e supplementation and cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. The heart outcomes prevention evaluation study investigators. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:154–160. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001203420302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sesso H, Buring J, Christen W, Kurth T, Belanger C, MacFadyen J, Bubes V, Manson J, Glynn R, Gaziano J. Vitamins e and c in the prevention of cardiovascular disease in men: The physicians' health study ii randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;300:2123–2133. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang H, Luo Y, Zhang W, He Y, Dai S, Zhang R, Huang Y, Bernatchez P, Giordano F, Shadel G, Sessa W, Min W. Endothelial-specific expression of mitochondrial thioredoxin improves endothelial cell function and reduces atherosclerotic lesions. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:1108–1120. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Furumoto K, Inoue E, Nagao N, Hiyama E, Miwa N. Age-dependent telomere shortening is slowed down by enrichment of intracellular vitamin c via suppression of oxidative stress. Life Sci. 1998;63:935–948. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(98)00351-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Haendeler J, Hoffmann J, Diehl J, Vasa M, Spyridopoulos I, Zeiher A, Dimmeler S. Antioxidants inhibit nuclear export of telomerase reverse transcriptase and delay replicative senescence of endothelial cells. Circ Res. 2004;94:768–775. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000121104.05977.F3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bode-Boger S, Martens-Lobenhoffer J, Tager M, Schroder H, Scalera F. Aspirin reduces endothelial cell senescence. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;334:1226–1232. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hirooka Y, Eshima K, Setoguchi S, Kishi T, Egashira K, Takeshita A. Vitamin c improves attenuated angiotensin ii-induced endothelium-dependent vasodilation in human forearm vessels. Hypertens Res. 2003;26:953–959. doi: 10.1291/hypres.26.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Migliaccio E, Giorgio M, Mele S, Pelicci G, Reboldi P, Pandolfi P, Lanfrancone L, Pelicci P. The p66shc adaptor protein controls oxidative stress response and life span in mammals. Nature. 1999;402:309–313. doi: 10.1038/46311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhou S, Chen HZ, Wan YZ, Zhang QJ, Wei YS, Huang S, Liu JJ, Lu YB, Zhang ZQ, Yang RF, Zhang R, Cai H, Liu DP, Liang CC. Repression of p66shc expression by sirt1 contributes to the prevention of hyperglycemia-induced endothelial dysfunction. Circ Res. 2011;109:639–648. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.243592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Francia P, delli Gatti C, Bachschmid M, Martin-Padura I, Savoia C, Migliaccio E, Pelicci PG, Schiavoni M, Luscher TF, Volpe M, Cosentino F. Deletion of p66shc gene protects against age-related endothelial dysfunction. Circulation. 2004;110:2889–2895. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000147731.24444.4D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Napoli C, Martin-Padura I, de Nigris F, Giorgio M, Mansueto G, Somma P, Condorelli M, Sica G, De Rosa G, Pelicci P. Deletion of the p66shc longevity gene reduces systemic and tissue oxidative stress, vascular cell apoptosis, and early atherogenesis in mice fed a high-fat diet. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:2112–2116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0336359100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yamamori T, White AR, Mattagajasingh I, Khanday FA, Haile A, Qi B, Jeon BH, Bugayenko A, Kasuno K, Berkowitz DE, Irani K. P66shc regulates endothelial no production and endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation: Implications for age-associated vascular dysfunction. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;39:992–995. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Murohara T, Asahara T, Silver M, Bauters C, Masuda H, Kalka C, Kearney M, Chen D, Symes J, Fishman M, Huang P, Isner J. Nitric oxide synthase modulates angiogenesis in response to tissue ischemia. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:2567–2578. doi: 10.1172/JCI1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Papapetropoulos A, Garcia-Cardena G, Madri J, Sessa W. Nitric oxide production contributes to the angiogenic properties of vascular endothelial growth factor in human endothelial cells. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:3131–3139. doi: 10.1172/JCI119868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ozuyaman B, Ebner P, Niesler U, Ziemann J, Kleinbongard P, Jax T, Godecke A, Kelm M, Kalka C. Nitric oxide differentially regulates proliferation and mobilization of endothelial progenitor cells but not of hematopoietic stem cells. Thromb Haemost. 2005;94:770–772. doi: 10.1160/TH05-01-0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Davis M, Cai H, Drummond G, Harrison D. Shear stress regulates endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression through c-src by divergent signaling pathways. Circ Res. 2001;89:1073–1080. doi: 10.1161/hh2301.100806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hayashi T, Matsui-Hirai H, Miyazaki-Akita A, Fukatsu A, Funami J, Ding Q, Kamalanathan S, Hattori Y, Ignarro L, Iguchi A. Endothelial cellular senescence is inhibited by nitric oxide: Implications in atherosclerosis associated with menopause and diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:17018–17023. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607873103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Higashi Y, Noma K, Yoshizumi M, Kihara Y. Endothelial function and oxidative stress in cardiovascular diseases. Circ J. 2009;73:411–418. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-08-1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Forstermann U, Sessa W. Nitric oxide synthases: Regulation and function. Eur Heart J. 2011 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sessa WC. Enos at a glance. Journal of Cell Science. 2004;117:2427–2429. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Barton M, Cosentino F, Brandes R, Moreau P, Shaw S, Luscher T. Anatomic heterogeneity of vascular aging: Role of nitric oxide and endothelin. Hypertension. 1997;30:817–824. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.30.4.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yoon H, Cho S, Ahn B, Yang S. Alterations in the activity and expression of endothelial no synthase in aged human endothelial cells. Mech Ageing Dev. 2010;131:119–123. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kim J, Bugaj L, Oh Y, Bivalacqua T, Ryoo S, Soucy K, Santhanam L, Webb A, Camara A, Sikka G, Nyhan D, Shoukas A, Ilies M, Christianson D, Champion H, Berkowitz D. Arginase inhibition restores nos coupling and reverses endothelial dysfunction and vascular stiffness in old rats. J Appl Physiol. 2009;107:1249–1257. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.91393.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Smith A, Visioli F, Frei B, Hagen T. Age-related changes in endothelial nitric oxide synthase phosphorylation and nitric oxide dependent vasodilation: Evidence for a novel mechanism involving sphingomyelinase and ceramide-activated phosphatase 2a. Aging Cell. 2006;5:391–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bach M, Sadoun E, Reed M. Defects in activation of nitric oxide synthases occur during delayed angiogenesis in aging. Mech Ageing Dev. 2005;126:467–473. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sindler A, Delp M, Reyes R, Wu G, Muller-Delp J. Effects of ageing and exercise training on enos uncoupling in skeletal muscle resistance arterioles. J Physiol. 2009;587:3885–3897. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.172221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yang Y, Huang A, Kaley G, Sun D. Enos uncoupling and endothelial dysfunction in aged vessels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H1829–H1836. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00230.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.van der Loo B, Labugger R, Skepper JN, Bachschmid M, Kilo J, Powell JM, Palacios-Callender M, Erusalimsky JD, Quaschning T, Malinski T, Gygi D, Ullrich V, Lüscher TF. Enhanced peroxynitrite formation is associated with vascular aging. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1731–1744. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.12.1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Beckman J, Beckman T, Chen J, Marshall P, Freeman B. Apparent hydroxyl radical production by peroxynitrite: Implications for endothelial injury from nitric oxide and superoxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:1620–1624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.4.1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Vasquez-Vivar J, Kalyanaraman B, Martasek P, Hogg N, Masters B, Karoui H, Tordo P, Pritchard KJ. Superoxide generation by endothelial nitric oxide synthase: The influence of cofactors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:9220–9225. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chou T, Yen M, Li C, Ding Y. Alterations of nitric oxide synthase expression with aging and hypertension in rats. Hypertension. 1998;31:643–648. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.31.2.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Rivard A, Berthou-Soulie L, Principe N, Kearney M, Curry C, Branellec D, Semenza GL, Isner JM. Age-dependent defect in vascular endothelial growth factor expression is associated with reduced hypoxia-inducible factor 1 activity. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:29643–29647. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001029200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ahluwalia A, Narula J, Jones M, Deng X, Tarnawski A. Impaired angiogenesis in aging myocardial microvascular endothelial cells is associated with reduced importin alpha and decreased nuclear transport of hif1 alpha: Mechanistic implications. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2010;61:133–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rajagopalan S, Olin J, Deitcher S, Pieczek A, Laird J, Grossman P, Goldman C, McEllin K, Kelly R, Chronos N. Use of a constitutively active hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha transgene as a therapeutic strategy in no-option critical limb ischemia patients: Phase i dose-escalation experience. Circulation. 2007;115:1234–1243. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.607994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bosch-Marce M, Okuyama H, Wesley J, Sarkar K, Kimura H, Liu Y, Zhang H, Strazza M, Rey S, Savino L, Zhou Y, McDonald K, Na Y, Vandiver S, Rabi A, Shaked Y, Kerbel R, Lavallee T, Semenza G. Effects of aging and hypoxia-inducible factor-1 activity on angiogenic cell mobilization and recovery of perfusion after limb ischemia. Circ Res. 2007;101:1310–1318. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.153346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Cheng X, Kuzuya M, Kim W, Song H, Hu L, Inoue A, Nakamura K, Di Q, Sasaki T, Tsuzuki M, Shi G, Okumura K, Murohara T. Exercise training stimulates ischemia-induced neovascularization via phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/akt-dependent hypoxia-induced factor-1 alpha reactivation in mice of advanced age. Circulation. 2010;122:707–716. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.909218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Weinstein R, Wan C, Liu Q, Wang Y, Almeida M, O'Brien C, Thostenson J, Roberson P, Boskey A, Clemens T, Manolagas S. Endogenous glucocorticoids decrease skeletal angiogenesis, vascularity, hydration, and strength in aged mice. Aging Cell. 2010;9:147–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00545.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lim J, Lee Y, Chun Y, Chen J, Kim J, Park J. Sirtuin 1 modulates cellular responses to hypoxia by deacetylating hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha. Mol Cell. 2010;38:864–878. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ferrara N. Vegf-a: A critical regulator of blood vessel growth. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2009;20:158–163. doi: 10.1684/ecn.2009.0170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wagner P, Olfert I, Tang K, Breen E. Muscle-targeted deletion of vegf and exercise capacity in mice. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2006;151:159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wagatsuma A. Effect of aging on expression of angiogenesis-related factors in mouse skeletal muscle. Exp Gerontol. 2006;41:49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ryan NA. Lower skeletal muscle capillarization and vegf expression in aged vs. Young men. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2006;100:178–185. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00827.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Croley A, Zwetsloot K, Westerkamp L, Ryan N, Pendergast A, Hickner R, Pofahl W, Gavin T. Lower capillarization, vegf protein, and vegf mrna response to acute exercise in the vastus lateralis muscle of aged vs. Young women. J Appl Physiol. 2005;99:1872–1879. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00498.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Xaymardan M, Zheng J, Duignan I, Chin A, Holm J, Ballard V, Edelberg J. Senescent impairment in synergistic cytokine pathways that provide rapid cardioprotection in the rat heart. J Exp Med. 2004;199:797–804. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Garfinkel S, Hu X, Prudovsky I, McMahon G, Kapnik E, McDowell S, Maciag T. Fgf-1-dependent proliferative and migratory responses are impaired in senescent human umbilical vein endothelial cells and correlate with the inability to signal tyrosine phosphorylation of fibroblast growth factor receptor-1 substrates. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:783–791. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.3.783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Iemitsu M. Exercise training improves aging-induced downregulation of vegf angiogenic signaling cascade in hearts. AJP: Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2006;291:H1290–H1298. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00820.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Leosco D, Rengo G, Iaccarino G, Sanzari E, Golino L, De Lisa G, Zincarelli C, Fortunato F, Ciccarelli M, Cimini V, Altobelli G, Piscione F, Galasso G, Trimarco B, Koch W, Rengo F. Prior exercise improves age-dependent vascular endothelial growth factor downregulation and angiogenesis responses to hind-limb ischemia in old rats. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:471–480. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.5.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Finkel T, Deng C, Mostoslavsky R. Recent progress in the biology and physiology of sirtuins. Nature. 2009;460:587–591. doi: 10.1038/nature08197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Haigis MC, Sinclair DA. Mammalian sirtuins: Biological insights and disease relevance. Annu Rev Pathol. 2010;5:253–295. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Tissenbaum H, Guarente L. Increased dosage of a sir-2 gene extends lifespan in caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2001;410:227–230. doi: 10.1038/35065638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Viswanathan M, Guarente L. Regulation of caenorhabditis elegans lifespan by sir-2.1 transgenes. Nature. 2011;477:E1–E2. doi: 10.1038/nature10440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Baur J, Pearson K, Price N, Jamieson H, Lerin C, Kalra A, Prabhu V, Allard J, Lopez-Lluch G, Lewis K, Pistell P, Poosala S, Becker K, Boss O, Gwinn D, Wang M, Ramaswamy S, Fishbein K, Spencer R, Lakatta E, Le Couteur D, Shaw R, Navas P, Puigserver P, Ingram D, de Cabo R, Sinclair D. Resveratrol improves health and survival of mice on a high-calorie diet. Nature. 2006;444:337–342. doi: 10.1038/nature05354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Wood J, Rogina B, Lavu S, Howitz K, Helfand S, Tatar M, Sinclair D. Sirtuin activators mimic caloric restriction and delay ageing in metazoans. Nature. 2004;430:686–689. doi: 10.1038/nature02789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Howitz K, Bitterman K, Cohen H, Lamming D, Lavu S, Wood J, Zipkin R, Chung P, Kisielewski A, Zhang L, Scherer B, Sinclair D. Small molecule activators of sirtuins extend saccharomyces cerevisiae lifespan. Nature. 2003;425:191–196. doi: 10.1038/nature01960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Burnett C, Valentini S, Cabreiro F, Goss M, Somogyvari M, Piper M, Hoddinott M, Sutphin G, Leko V, McElwee J, Vazquez-Manrique R, Orfila A, Ackerman D, Au C, Vinti G, Riesen M, Howard K, Neri C, Bedalov A, Kaeberlein M, Soti C, Partridge L, Gems D. Absence of effects of sir2 overexpression on lifespan in c. Elegans and drosophila. Nature. 2011;477:482–485. doi: 10.1038/nature10296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Stein S, Matter CM. Protective roles of sirt1 in atherosclerosis. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:640–647. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.4.14863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Ota H, Akishita M, Eto M, Iijima K, Kaneki M, Ouchi Y. Sirt1 modulates premature senescence-like phenotype in human endothelial cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;43:571–579. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Nisoli E, Tonello C, Cardile A, Cozzi V, Bracale R, Tedesco L, Falcone S, Valerio A, Cantoni O, Clementi E, Moncada S, Carruba MO. Calorie restriction promotes mitochondrial biogenesis by inducing the expression of enos. Science. 2005;310:314–317. doi: 10.1126/science.1117728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Mattagajasingh I, Kim C-S, Naqvi A, Yamamori T, Hoffman TA, Jung S-B, DeRicco J, Kasuno K, Irani K. Sirt1 promotes endothelium-dependent vascular relaxation by activating endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:14855–14860. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704329104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Zhang Q-J, Wang Z, Chen H-Z, Zhou S, Zheng W, Liu G, Wei Y-S, Cai H, Liu D-P, Liang C-C. Endothelium-specific overexpression of class iii deacetylase sirt1 decreases atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein e-deficient mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;80:191–199. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Qiang L, Lin HV, Kim-Muller JY, Welch CL, Gu W, Accili D. Proatherogenic abnormalities of lipid metabolism in sirt1 transgenic mice are mediated through creb deacetylation. Cell Metab. 2011;14:758–767. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]