Abstract

Purpose:

To evaluate the positive predictive value (PPV) of bilateral whole-breast ultrasonography (BWBU) for detection of synchronous breast lesions on initial diagnosis of breast cancer and evaluate factors affecting the PPV of BWBU according to varying clinicoimaging factors.

Methods:

A total of 75 patients who had synchronous lesions with pathologic confirmation at the initial diagnosis of breast cancer during January 2007 and December 2007 were included. The clinical factors of the patients were evaluated. One observer retrospectively reviewed the imaging studies of the index breast cancer lesion and the synchronous lesion. The PPV for additional biopsy was calculated for BWBU and various clinical and imaging factors affecting the PPV for BWBU were evaluated.

Results:

The overall PPV for additional biopsy was 25.7% (18 of 70). The PPV for synchronous lesions detected both on mammography and BWBU, and detected only on BWBU, was 76.9% (10 of 13) and 14.3% (7 of 49), respectively. There was no clinical factor affecting the PPV for BWBU. Among the imaging factors, ipsilateral location of the synchronous lesion to the index lesion (P=0.06) showed a marginal statistically significant correlation with malignancy in the synchronous breast lesion. A mass with calcification on mammography presentation (P<0.01), presence of calcification among the ultrasonography findings (P<0.01), and high Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System final assessment (P<0.01) were imaging factors that were associated with malignancy in the additional synchronous lesion.

Conclusion:

BWBU can detect additional synchronous malignancy at the diagnosis of breast cancer with a relatively high PPV, especially when mammography findings are correlated with ultrasonographic findings.

Keywords: Ultrasonography, mammary; Breast neoplasms; Perioperative period; Neoplasm staging; Predictive value of tests

Introduction

As a result of greater awareness of breast cancer by the physician and the patient with expansion of breast cancer screening, more of these tumors are detected in the earlier stages [1]. Women who require surgical treatment of early stage breast cancer may prefer to undergo breast-conserving therapy, as oncologic breast surgery can have a profound impact on a woman’s body image and sense of self. Detection of synchronous breast cancers on initial diagnosis is critical for determining eligibility for breast conserving surgery [2].

Mammography is the only proven efficacious radiographic screening technique for detection of breast cancer; however, the sensitivity of mammography has been reported to be lower in women with dense breasts than in women with primarily fatty breasts (62.2% vs. 88.2%) [3,4]. Furthermore, detection of synchronous malignancy is more challenging because the additionally detected breast cancer lesions are known to be smaller and less suspicious than the index cancer [5]. Bilateral wholebreast ultrasonography (BWBU) has been used to overcome these limitations of mammography and has been reported to be an efficacious imaging modality in identifying mammographically occult breast cancer in preoperative staging [6]. Hence, the roles of various other imaging modalities are under study for detection of breast cancer lesions not detected on mammography or clinical breast examination [7]. To our knowledge, there has been no published study regarding the positive predictive value (PPV) of BWBU in detection of synchronous breast lesions in a large population.

The purpose of our study was to evaluate the PPV of BWBU on detection of synchronous breast lesions on initial diagnosis of breast cancer and also evaluate factors affecting the PPV of BWBU according to various clinical and imaging factors.

Materials and Methods

Our institutional review board approved this study and waived the informed consent requirement because this was a retrospective study.

Patients

Between January 2007 and December 2007, 694 women recently diagnosed with breast cancer at our institution (n=346) or another hospital (n=348) were reviewed in this study. All of the patients underwent mammography before BWBU. The patients with additional breast lesions with suspicious radiological findings other than the primary breast cancer lesion that underwent imagingguided biopsy or surgical resection after imaging-guided localization were reviewed in the study.

Image evaluation and diagnostic strategy for additional lesions

Mammograms were obtained with dedicated equipment, a Selenia Full-Field Digital Mammography System (Lorad/Hologic, Danbury, CT, USA). Standard craniocaudal and mediolateral oblique views were routinely obtained and additional mammographic views were obtained as needed. If recent mammograms taken from another hospital were available at the time of BWBU, routine mammograms were not performed in our institution.

BWBU was performed using ATL HDI 5000 and 3000 (Philips Medical Systems, Bothell, WA, USA) ultrasonography units with 10-MHz linear array transducers by 5 full-time board-certified radiologists, all having at least several years of experience in performing breast ultrasonography (2-11 years). The radiologists performing BWBU knew the results of any mammograms and previous sonograms. Ultrasonography was performed with the patient in the supine position with the arms raised. If necessary, the patient was shifted into an appropriate contralateral posterior oblique position so that the lateral and inferior parts of the breasts could be scanned. Scanning was performed in the radial and antiradial planes, as well as in the longitudinal and transverse planes [8]. Scanning of both axillas started from the lower part of the axilla and continued upward toward the axillary fossa. The examination took approximately 15 minutes (range, 10 to 20 minutes).

All additional synchronous breast lesions detected on ultrasonography with a Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) category higher than 4 were sampled for biopsy with a ultrasonographic (US)-guided 14-gauge automatic core-needle biopsy (CNB). When there were two or more suspicious synchronous breast lesions, the most suspicious lesion or the lesion that could alter the surgical method was selected for biopsy. All additional synchronous breast lesions detected only on mammography as suspicious calcifications and not identified on ultrasonography were sampled for biopsy under mammography-guided localization.

Retrospective image review and data analysis

We defined the index lesion as the mass that was either detected by the patient as a palpable lump, the mass that was first detected by imaging modalities such as mammography, or that was categorized as the highest final assessment by BI-RADS when two or more lesions were detected simultaneously in screening BWBU in a patient with dense breasts on a mammogram. A synchronous lesion was defined as a lesion that showed suspicious findings other than the index lesion detected in the same initial BWBU exam that appeared more than 2 cm from the index lesion.

Clinical information on the patients was collected by retrospective chart review. The age of the patient at diagnosis of breast cancer, family history of breast cancer, and menopause status were reviewed. The mammographic and ultrasonographic images of the index and synchronous lesion were retrospectively reviewed by one radiologist (MJK). The index and synchronous lesions detected on mammography were described as a mass only, mass with calcification, or calcification only. For the ultrasonographic images, the size of each lesion was measured, and the locations of the synchronous additional lesions were categorized as ipsilateral or contralateral to the index lesion. All index and additional synchronous lesions were described according to the BI-RADS lexicon [9]. The BI-RADS final assessment given for the index lesion and the additional lesion according to the mammographic and ultrasonographic findings were based on the category classifications of the original radiology reports.

The PPV was determined according to the clinicoradiologic features of the index and additional lesions. The Student t-test was used for comparison of continuous variables and the chi-squared test was used for categorical data. Logistic regression was used to construct a multivariate model of independent factors associated with the risk of additional synchronous breast lesions’ malignancy. Statistical significance was assigned to P-values less than 0.05. Data was analyzed using the SPSS ver. 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

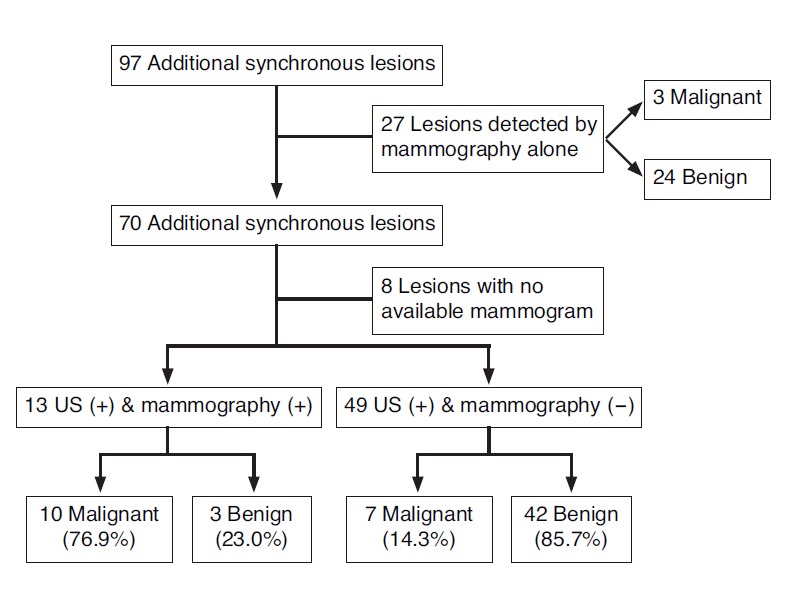

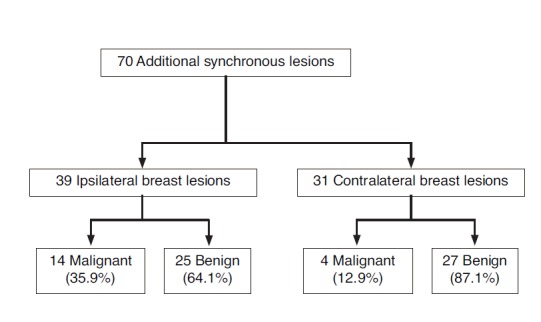

Among the 694 patients diagnosed with breast cancer, 75 patients (10.8%) had 97 additional breast lesions that underwent further pathologic confirmation through US-guided CNB (n=70) and mammography-guided localization and excision biopsy (n=27). These 27 cases detected only on mammography were excluded from the data analysis. Among the 27 cases, three lesions (11.1%) were pathologically confirmed as malignant and 24 lesions (88.9%) as benign. Among 70 cases by US-guided core-needle biopsy in 54 women, 18 lesions (25.7%) were diagnosed as malignant and 52 lesions (74.3%) as benign; the overall PPV for additional biopsy was 25.7%. Among the 70 lesions, 13 lesions were seen in both US and mammography with a PPV for biopsy of 76.9% (10/13), 49 (70%) were detected only in US with a PPV of 14.3% (7/49), and the remaining 8 lesions could not be correlated with mammography because there were no available mammograms (Fig. 1). Thirty-nine synchronous breast lesions were found ipsilateral to the index lesion and 31 lesions were found contralateral to the index lesion; the PPV for ipsilateral and contralateral lesions were 35.9% and 12.9%, respectively (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Diagram of pathologic diagnosis of synchronous lesions according to variable imaging modalities. US, ultrasonography.

Fig. 2.

Diagram of pathologic diagnosis of additional synchronous lesions according to the location of the index lesion.

Pathology of synchronous lesions according to the clinical factors of patients

The 54 patients in the study ranged in age from 30 to 74 years. The patients with additional benign synchronous breast lesions had a mean age of 44.7 years (range, 30 to 74 years), and the patients with additional malignant synchronous breast lesions had a mean age of 45.4 years (range, 30 to 74 years) (Table 1). There was no statistical significance between the patients age and the PPV for additional synchronous malignant lesions (P=0.63). Six of the 54 patients had a family history of breast cancer; 3 patients had a family history of their sisters with breast cancer, 2 patients in their mothers, and 1 patient in her aunt. Two patients with a family history of breast cancer had additional synchronous malignant breast lesions; however, there was no statistical significance between a patient’s family history and the PPV for additional synchronous malignant lesions (P=0.79). Correlation between the menopause status of the patient and additional synchronous malignant lesions also did not show statistical significance (P=0.30).

Table 1.

Clinical factors of 54 patients with synchronous lesions by bilateral whole-breast ultrasonography

| Clinical factor | Histopathologic outcome |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Additional synchronous benign breast lesion (n=38) | Additional synchronous malignant breast lesion (n=16) | P-value | |

| Age (yr), mean±SD (range) | 44.7±9.10 (30-74) | 45.4±9.97 (30-74) | 0.63 |

| Family history of breast cancer | 4 | 4 | 0.79 |

| Menopause | 0.30 | ||

| Premenopause | 30 | 11 | |

| Menopause | 5 | 5 | |

| Unknown | 3 | 3 | |

Pathology of synchronous lesions according to the imaging factors of index lesions

The imaging factors of 54 index lesions according to the pathology of 70 synchronous breast lesions did not show any imaging factor of the index lesion that correlated significantly with the pathology of a synchronous breast lesion (Table 2).

Table 2.

Pathology of synchronous lesions according to imaging factors of 54 index lesions

| Characteristic | Histopathologic outcome |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Benign a)(n=52) | Malignant b)(n=18) | P-value | |

| Size (mm), mean±SD (range) | 20±9.8 (4-40) | 17±9.5 (5-41) | 0.23 |

| Mammography presentation c) | 0.46 | ||

| Negative | 8 | 1 | |

| Mass only | 24 | 8 | |

| Mass with microcalcifications | 11 | 5 | |

| Calcifications only | 1 | 2 | |

| Not available | 7 | 1 | |

| Ultrasonogrphic findings | |||

| Shape c) | 0.93 | ||

| Round | 6 | 3 | |

| Oval | 13 | 4 | |

| Irregular | 31 | 10 | |

| Orientation | 0.84 | ||

| Parallel | 14 | 5 | |

| Non-parallel | 36 | 12 | |

| Margin | 0.17 | ||

| Well-circumscribed | 4 | 4 | |

| Indistinct | 4 | 3 | |

| Angular | 7 | 0 | |

| Microlobulated | 20 | 5 | |

| Spiculated | 15 | 5 | |

| Boundary | 0.42 | ||

| Abrupt | 31 | 13 | |

| Echogenic halo | 19 | 4 | |

| Echogenicity | 0.44 | ||

| Anechoic | 0 | 0 | |

| Hyperechoic | 2 | 1 | |

| Complex | 0 | 0 | |

| Hypoechoic | 36 | 12 | |

| Isoechoic | 12 | 4 | |

| Acoustic attenuation | 0.87 | ||

| None | 38 | 12 | |

| Enhancement | 8 | 3 | |

| Shadowing | 4 | 2 | |

| Calcification | 0.39 | ||

| None | 20 | 6 | |

| With calcification | 30 | 11 | |

| Final assessment | 0.63 | ||

| Category 4a | 6 | 2 | |

| Category 4b | 10 | 2 | |

| Category 4c | 15 | 3 | |

| Category 5 | 19 | 10 | |

Additional synchronous benign breast lesion.

Additional synchronous malignant breast lesion.

Imaging features of 3 index breast lesions were not included because they were previously excised (2 in additional benign and one in additional malignant).

Pathology of synchronous lesions according to the location and imaging factors of synchronous lesions

With regard to the location of synchronous lesions to the index lesion, an ipsilateral location of a synchronous lesion showed marginal significance for correlating with a malignant pathology (P=0.06). Among the imaging factors of 70 synchronous breast lesions, a mass with calcification presented on mammography (P<0.01), the presence of calcification among the ultrasonographic findings (P<0.01), and a high BI-RADS final assessment (P<0.01) were imaging factors with statistical significance for the additional synchronous lesion to be malignant (Table 3). On multivariable logistic regression analysis, these factors showed statistical significance; a mass with calcification mammography presentation (odds ratio [OR], 2.95; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.11 to 8.32), presence of calcification (OR, 3.36; 95% CI, 0.14 to 82.92), and higher BI-RADS assessment of the synchronous additional lesion (OR, 6.30; 95% CI, 0.70 to 55.01) were found to be statistically significant independent factors associated with malignancy of the synchronous lesion.

Table 3.

Pathology of synchronous lesions according to location and imaging factors of 70 additional breast lesions seen on ultrasonography

| Characteristic | Histopathologic outcome |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Benign a)(n=52) | Malignant b)(n=18) | P-value | |

| Size (mm), mean±SD (range) | 7.8±3.9 (4-21) | 8.7±3.8 (4-17) | 0.36 |

| Location related to index lesion | 0.06 | ||

| Ipsilateral | 25 | 14 | |

| Contralateral | 27 | 4 | |

| Mammography presentation | <0.01 | ||

| Negative | 42 | 7 | |

| Mass only | 1 | 1 | |

| Mass with microcalcifications | 0 | 5 | |

| Calcifications only | 2 | 4 | |

| Not available | 7 | 1 | |

| Ultrasonographic findings | 13 | 4 | |

| Shape | 0.22 | ||

| Round | 12 | 8 | |

| Oval | 23 | 6 | |

| Irregular | 17 | 4 | |

| Orientation | 0.32 | ||

| Parallel | 32 | 8 | |

| Non-parallel | 20 | 10 | |

| Margin | 0.53 | ||

| Well-circumscribed | 4 | 1 | |

| Indistinct | 12 | 4 | |

| Angular | 7 | 0 | |

| Microlobulated | 23 | 10 | |

| Spiculated | 6 | 3 | |

| Boundary | 0.40 | ||

| Abrupt | 47 | 18 | |

| Echogenic halo | 5 | 0 | |

| Echogenicity | 0.82 | ||

| Anechoic | 0 | 0 | |

| Hyperechoic | 1 | 0 | |

| Complex | 0 | 0 | |

| Hypoechoic | 27 | 9 | |

| Isoechoic | 24 | 9 | |

| Acoustic attenuation | 0.53 | ||

| None | 48 | 18 | |

| Enhancement | 4 | 0 | |

| Shadowing | 0 | 0 | |

| Calcification | <0.01 | ||

| None | 50 | 10 | |

| With calcification | 2 | 8 | |

| Final assessment | <0.01 | ||

| Category 4a | 46 | 9 | |

| Category 4b | 4 | 2 | |

| Category 4c | 2 | 6 | |

| Category 5 | 0 | 1 | |

Additional synchronous benign breast lesion.

Additional synchronous malignant breast lesion.

Discussion

Breast conservation therapy is the preferred method of treatment for women with stage I or II breast cancer instead of mastectomy and conservation surgery with radiation therapy [10]. Holland et al. [11] found a total of 43% (121 out of 282) additional tumor foci in mastectomy specimens more than 2 cm away from the index cancer. Moreover, contralateral synchronous breast cancers are known to lower the survival rate compared to unilateral breast cancer [12,13]. Therefore, the exact characterization of synchronous lesions other than the primary cancer lesion at the time of initial diagnosis is crucial for surgical planning as well as establishing the prognosis of the patient [2]. Although mammography is the only proven efficacious radiographic screening technique for detection of breast cancer, whole breast ultrasonography is considered an adjunct to mammography in the preoperative staging of breast cancer [13]. Buchberger et al. [14] verified the role of ultrasonography in detection of mammographically and clinically occult carcinoma with 28 malignant lesions only found on ultrasonography among a total of 103 malignancies. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the role of ultrasonography in the preoperative staging of patients with breast cancer in identifying any synchronous breast lesions for accurate breast cancer staging and optimize treatment planning.

Our results show the overall PPV of biopsies for additional synchronous lesions in patients with breast cancer on BWBU to be 25.7% regardless of mammographic findings and the PPV for lesions detected only on ultrasonography to be 14.3%. These results are lower than previously reported PPV values of 30%-40% for ultrasonographic screening in high-risk patients [14,15]. These results could be explained by the fact that each subtle but suspicious lesion (70 lesions in 54 patients) identified in preoperative ultrasonography for breast cancer needed to be confirmed by biopsy, and we might lower the threshold of the category for lesions because we were already aware that about 11.4% additional breast lesions in breast cancer patients show malignancy more frequently than expected, even though they appear to be probably benign, through our own experience and the literature [2]. Meticulous evaluation of the remaining breast lesions was inevitable, and any subtle but suspicious findings lead the radiologist to consider the lesion to be a suspicious finding and perform biopsy for pathologic confirmation with the long-term experience of preoperative ultrasonography. This could have played a role lowering the PPV, compared with the results of other studies with high risk patients [7]. The PPV according to the final assessment was 16.4% (9/55), 33.3% (2/6), 75.0% (6/8), and 100.0% (1/1) for categories 4a, 4b, 4c, and 5 lesions, which is consistent with a previous report based on ultrasonographic findings [16], which still means that the BIRADS category can predict malignancy for the synchronous breast lesions in patients with breast cancer. However, we did not reclassify the ultrasonographic findings of additional nodules to check how many cases would have undergone biopsy or follow-up among patients who had undergone routine screening.

The clinical factors of the patients did not show statistical significance in detection of additional synchronous malignancy in patients with breast cancer. The age of the patient, family history of breast cancer, and menopause status were evaluated as clinical factors. Advanced age of the patient, family history of breast cancer, and natural menopause after age 45 are well known risk factors of breast cancer [17]. However, our results showed that these clinical risk factors were not related to an additional synchronous breast cancer lesion; as our study population is small, further investigation with a larger population is needed.

The relationship of a synchronous lesion to its index lesion was evaluated, and an ipsilateral location of the synchronous lesion showed marginal statistical significance for detection of additional synchronous malignancy. Previous studies also showed a higher PPV for additional lesions in an ipsilateral location [2]; therefore, the threshold for category 4 should be set more sensitive than for patients at a normal risk level when additional lesions are found ipsilaterally to the index lesion. In this study, none of the other imaging findings of the index lesion helped suggest malignancy of the synchronous lesion, and thorough inspection of the synchronous lesion itself is most important.

The PPV of biopsy for additional synchronous lesions detected both on mammography and ultrasonography (76.9%) was much higher than that detected only on ultrasonography (14.3%). At our institution, ultrasonography is performed just after review of the mammogram, which are interpreted together because missed cancers on the mammogram have been well known to be detected in about half of cases during retrospective review [18]. Even if the radiologist who reviews a mammogram does not find any abnormality prospectively, the radiologist might have searched for any subtle abnormality on the mammogram when a ultrasonographic lesion was detected, and then the abnormality could be mentioned. Only in cases showing no abnormality on the mammogram even during retrospective review, was the mammogram diagnosed as negative. Likewise, careful inspection of the area where an abnormality was detected on mammography was conducted on ultrasonography by the operator. Such a situation may have resulted in a relatively low incidence and low PPV of mammographically occult synchronous cancers detected only on ultrasonography.

Our study results showed that the PPV for additional lesions seen only on ultrasonography (14.3%) was higher than that of lesions detected only on mammography (11.1%), although statistical evaluation for significance was not performed and the analysis for the cases detected only on mammography was excluded in this study (Fig. 1). The PPV for lesions detected on mammography was lower than the Bi-RADS recommendation rate of 20%. These lesions correspond to synchronous additional lesions seen as calcifications on mammography but not detected on ultrasonography and a similar lower PPV has been reported previously for lesions only seen on mammography as calcifications [13]. The PPV for lesions detected only on ultrasonography also did not meet the biopsy recommendation rate by BI-RADS, and the large number of category 4a lesions with only subtle findings could have been attributed to these results. The PPV of 14.3% for additional lesions seen only on ultrasonography, although the threshold for category 4 was set sensitively since the operator was aware of the index cancer, suggest preoperative BWBU to be a clinically significant imaging modality additional to mammography for detection of additional lesions in breast cancer patients.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be another adjunct imaging modality in detection of additional synchronous malignancy in patients with breast cancer. An annual MRI is recommended in addition to mammography to women at very high risk of breast cancer in the United States with a high sensitivity in detection of malignancy [19,20]. However, only a limited number of patients actually underwent breast MRI in our study, and the high cost, requirement of contrast injection, and limited availability were the main reasons why MRI is not a well-established imaging modality. Further study is needed for evaluation of the role of MRI in detection of additional synchronous malignancy in patients with breast cancer, and the role of BWBU and MRI should be compared in order to use these imaging modalities as a screening tool in patients with breast cancer.

There were some limitations to our study. First, our study population with additional breast lesions that were pathologically confirmed in newly diagnosed breast cancer patients was small. Second, the study was conducted at a single site with only a limited number of radiologists and included mainly Asian women. Third, the clinical and imaging factors were only evaluated with respect to synchronous lesions detected on ultrasonography. Other imaging modalities such as mammography and MRI were not evaluated according to clinical and imaging factors. Furthermore, the negative predictive value was not evaluated. Furthermore, we did not suggest a standard for category 4 lesions to prevent unnecessary biopsies. In addition, the mammography was reviewed prior to the performance of US, which can affect the results of BWBU. Finally, the mammographic findings of synchronous lesions were retrospectively reviewed with the information of BWBU, which can also affect the mammographic interpretation of synchronous lesions.

In conclusion, BWBU can detect additional synchronous malignancy at the diagnosis of breast cancer with a relatively high PPV, especially when mammography findings are correlated with ultrasonographic findings.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Perez CA. Breast conservation therapy in patients with stage T1-T2 breast cancer: current challenges and opportunities. Am J Clin Oncol. 2010;33:500–510. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3181d31f15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim SJ, Ko EY, Shin JH, Kang SS, Mun SH, Han BK, et al. Application of sonographic BI-RADS to synchronous breast nodules detected in patients with breast cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:653–658. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robertson CL. A private breast imaging practice: medical audit of 25,788 screening and 1,077 diagnostic examinations. Radiology. 1993;187:75–79. doi: 10.1148/radiology.187.1.8451440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pinsky RW, Helvie MA. Mammographic breast density: effect on imaging and breast cancer risk. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8:1157–1164. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim MJ, Kim EK, Kwak JY, Park BW, Kim SI, Oh KK. Bilateral synchronous breast cancer in an Asian population: mammographic and sonographic characteristics, detection methods, and staging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190:208–213. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gordon PB, Goldenberg SL. Malignant breast masses detected only by ultrasound: a retrospective review. Cancer. 1995;76:626–630. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950815)76:4<626::aid-cncr2820760413>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim MJ, Kim EK, Kwak JY, Park BW, Kim SI, Sohn J, et al. Sonographic surveillance for the detection of contralateral metachronous breast cancer in an Asian population. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:221–228. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.4048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stavros AT, Thickman D, Rapp CL, Dennis MA, Parker SH, Sisney GA. Solid breast nodules: use of sonography to distinguish between benign and malignant lesions. Radiology. 1995;196:123–134. doi: 10.1148/radiology.196.1.7784555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liberman L, Menell JH. Breast imaging reporting and data system (BI-RADS) Radiol Clin North Am. 2002;40:409–430. doi: 10.1016/s0033-8389(01)00017-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winchester DP, Cox JD. Standards for diagnosis and management of invasive breast carcinoma. American College of Radiology. American College of Surgeons. College of American Pathologists. Society of Surgical Oncology. CA Cancer J Clin. 1998;48:83–107. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.48.2.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holland R, Veling SH, Mravunac M, Hendriks JH. Histologic multifocality of Tis, T1-2 breast carcinomas. Implications for clinical trials of breast-conserving surgery. Cancer. 1985;56:979–990. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850901)56:5<979::aid-cncr2820560502>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heron DE, Komarnicky LT, Hyslop T, Schwartz GF, Mansfield CM. Bilateral breast carcinoma: risk factors and outcomes for patients with synchronous and metachronous disease. Cancer. 2000;88:2739–2750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moon WK, Noh DY, Im JG. Multifocal, multicentric, and contralateral breast cancers: bilateral whole-breast US in the preoperative evaluation of patients. Radiology. 2002;224:569–576. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2242011215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buchberger W, DeKoekkoek-Doll P, Springer P, Obrist P, Dunser M. Incidental findings on sonography of the breast: clinical significance and diagnostic workup. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;173:921–927. doi: 10.2214/ajr.173.4.10511149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crystal P, Strano SD, Shcharynski S, Koretz MJ. Using sonography to screen women with mammographically dense breasts. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:177–182. doi: 10.2214/ajr.181.1.1810177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoon JH, Kim MJ, Moon HJ, Kwak JY, Kim EK. Subcategorization of ultrasonographic BI-RADS category 4: positive predictive value and clinical factors affecting it. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2011;37:693–699. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steiner E, Klubert D, Knutson D. Assessing breast cancer risk in women. Am Fam Physician. 2008;78:1361–1366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corsetti V, Ferrari A, Ghirardi M, Bergonzini R, Bellarosa S, Angelini O, et al. Role of ultrasonography in detecting mammographically occult breast carcinoma in women with dense breasts. Radiol Med. 2006;111:440–448. doi: 10.1007/s11547-006-0040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stoutjesdijk MJ, Boetes C, Jager GJ, Beex L, Bult P, Hendriks JH, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging and mammography in women with a hereditary risk of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:1095–1102. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.14.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saslow D, Boetes C, Burke W, Harms S, Leach MO, Lehman CD, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines for breast screening with MRI as an adjunct to mammography. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:75–89. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.2.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]