Abstract

Our previous work has shown that polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMN) require cellular ATP release and autocrine purinergic signaling for their activation. Here we studied in a mouse model of cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) whether sepsis affects this purinergic signaling process and thereby alters PMN responses after sepsis. Using high performance liquid chromatography, we found that plasma ATP, ADP, and AMP concentrations increased up to 6 fold during the first 8 h after CLP, reaching top levels that were significantly higher than those in sham control animals without CLP. While leukocyte and PMN counts in sham animals increased significantly after 4 h, these blood cell counts decreased in sepsis animals. CD11b expression on the cell surface of PMN of septic animals was significantly higher compared to sham and untreated control animals. These findings suggest increased PMN activation and sequestration of PMN from the circulation after sepsis. Plasma ATP levels correlated with CD11b expression, suggesting that increased ATP concentrations in plasma contribute to PMN activation. We found that treatment of septic mice with the ATP receptor antagonist suramin diminished CD11b expression, indicating that plasma ATP contributs to PMN activation by stimulating P2 receptors of PMN. Increased PMN activation can protect the host from invading microorganisms. However, increased PMN activation can also be detrimental by promoting secondary organ damage. We conclude that pharmacological targeting of P2 receptors may allow modulation of PMN responses in sepsis.

Keywords: Cecal ligation and puncture, CD11b expression, purinergic signaling, P2 receptor antagonist, suramin

INTRODUCTION

While PMN have a pivotal role in host defense by eliminating bacterial pathogens, overwhelming PMN activation can be harmful to the host by causing collateral tissue damage. Sepsis and the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) are associated with excessive PMN activation. In patients with severe sepsis, uncontrolled PMN activation can cause secondary tissue damage and multi-organ dysfunction, including acute lung injury(1, 2), cardiovascular instability, and deterioration of renal function (3). Despite strict adherence to established treatment protocols such as the “Surviving Sepsis Campaign” guidelines (4), sepsis has remained a major problem that afflicts millions worldwide each year and results in the death of one in three patients (5). Targeting PMN activation is considered a potential therapeutic strategy to reduce host tissue damage and organ failure in sepsis patients (6).

We have previously shown that activated PMN release a portion of their cellular ATP and that the released ATP is required to for autocrine feedback mechanisms via purinergic receptors that are indispensable for PMN activation (7). In mammals, nineteen different purinergic receptor subtypes have been identified that include four adenosine (P1) receptor subtypes, seven P2X receptor subtypes, and eight P2Y receptor subtypes (8). In PMN, P2Y2 receptors play a central role in cell activation (8). PMN and other immune cell populations depend on ATP release and autocrine feedback via these purinergic receptors for proper cell activation and for their effective function in immune defense (9–12). However, in trauma patients, large amounts of additional ATP can be released from damaged cells. Under these circumstances, ATP can serve as a ‘danger’ or ‘find-me’ signal emitted by stressed and injured tissues that allows recognition and elimination of damaged cells and initiation of wound repair (13, 14). Here we studied the effect of excessive extracellular ATP concentrations on the autocrine purinergic signaling systems that regulate PMN activation.

Extracellular ATP can be hydrolyzed to adenosine by various ectonucleotidase families that are found on the cell surfaces of virtually all mammalian cell types in tissue-specific distribution patterns (9, 10). Adenosine receptors have wide-ranging biological functions and, like ATP, adenosine is an important extracellular signaling molecule that regulates immunological processes including PMN function (15). A2a receptors are the most abundantly expressed purinergic receptor subtype in PMN (16). A2a receptors belong to the Gs protein coupled receptors that trigger intracellular cAMP accumulation and thereby can inhibit PMN functions (15, 17). Because of its inhibitory effects on PMN, extracellular adenosine is considered an innate anti-inflammatory mediator that reduces PMN activation and secondary tissue damage (18).

Despite the growing evidence that ATP and adenosine receptors are important regulators of PMN function, little information is available about the role of plasma ATP and adenosine in the activation of PMN during sepsis. In this study, we found that sepsis causes a profound increase in plasma ATP, that this increase corresponds to an increase in PMN activation, and that inhibition of P2 receptors with suramin reduces PMN activation in response to sepsis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse sepsis model

The use of laboratory animals was in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. A mouse model of sepsis was established by performing cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) as previously described (19). Briefly, adult male C57BL/6J wild-type mice (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA), 8–10 weeks old, weighing 20–25 g were subjected to general anesthesia with 1–2% Isoflurane using a precision vaporizer (V-1 Table Top System; Vet Equip, Pleasanton, CA). CLP was performed by placing a 1-cm midline abdominal incision. The exposed cecum was ligated with 4-0 silk at the distal side to the ileocecal valve, avoiding intestinal obstruction. The cecum was punctured twice with a 22-G needle, returned into the abdomen, and the abdominal wall was closed in layers. After full recovery from anesthesia, the mice were returned to their cages and allowed access to standard diet and water ad libitum. Leukocyte counts in heparinized blood samples were determined with a Hemovet cell counter (Drew Scientific, Oxford, CT); PMN counts were determined by Giemsa staining (Hema 3 Stat Pack; Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) and manually enumerating PMN under a microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). For determination of plasma nucleotide concentrations and PMN activation, animals were anesthetized and blood collected via axial vessels.

Treatment with suramin

The ATP receptor antagonist suramin was obtained from Calbiochem (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and used at a concentration of 1 mM in normal saline. This solution was administered subcutaneously as a bolus injection at a dose of 4 μl/g body weight during the surgical procedure prior to cecal puncture. This dose was based on our previous in vitro work (5). At this dose, suramin did not appear to have any noticeable toxic effects as tested in a pilot experiment with control animals.

HPLC analysis of plasma ATP levels

The concentrations of ATP, ADP, AMP, and adenosine in mouse plasma were assessed by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) as previously described (20). Briefly, heparinized blood was immediately chilled by placing the tubes on ice for 15 min. The samples were transferred to Eppendorf centrifuge tubes and gently centrifuged in an Eppendorf centrifuge for 10 min at 2,000 rpm and 0°C. Cells were discarded and plasma samples were centrifuged again to remove platelets and remaining cells (5,000 rpm, 5 min, 0°C). The resulting plasma samples (200 μl) were treated with 10 μl of an 8 M perchloric acid solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min at 0°C to precipitate proteins. In order to neutralize the pH of the resulting solutions and to remove lipids, supernatants (80 μl) were treated with 4 M K2HPO4 (8 μl) and tri-N-octylamine (50 μl). These samples were mixed with 50 μl of 1,1,2-trichloro-trifluoroethane and centrifuged (13,000 rpm, 10 min, 0°C) and this last lipid extraction step was repeated once. The resulting supernatants were subjected to the following procedure to generate fluorescent etheno-adenine products: 150 μl supernatant (or nucleotide standard solution) was incubated at 72°C for 30 min with 250 mM Na2HPO4 (20 μl) and 1 M chloroacetaldehyde (30 μl; Sigma-Aldrich) in a final reaction volume of 200 μl resulting in the formation of 1,N6-etheno derivatives as previously described (20). Samples were placed on ice, alkalinized with 0.5 M NH4HCO3 (50 μl), and analyzed using a Waters HPLC system (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) consisting of a gradient system described previously, a Waters autosampler, and a Waters 474 fluorescence detector (16).

Neutrophil activation

PMN activation was assessed by measuring the abundance of CD11b on the cell surface of Ly-6G positive cells using a flow cytometer. Briefly, 100 μl of heparinized whole mouse blood was diluted with 100 μl of HBSS (Thermo Scientific, Agawam, MA), incubated for 20 min on ice and in the dark with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-mouse CD11b antibodies (clone M1/70.15; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-mouse Ly-6G antibodies (clone RB6-8C5; eBioscience, San Diego, CA). Red blood cells were lysed for 4 min on ice with RBC Lysis Buffer (eBioscience) and the remaining cells were washed twice with HBSS, fixed with FACS sheath fluid (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) containing 0.5% formaldehyde, and analyzed with a FACSCalibur flow cytometry (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM unless stated otherwise. Statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics (IBM Japan, Tokyo, Japan) using 2-tailed unpaired Student’s t tests or Mann-Whitney test for comparisons of two groups. Spearman’s rank correlation was performed as indicated; P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

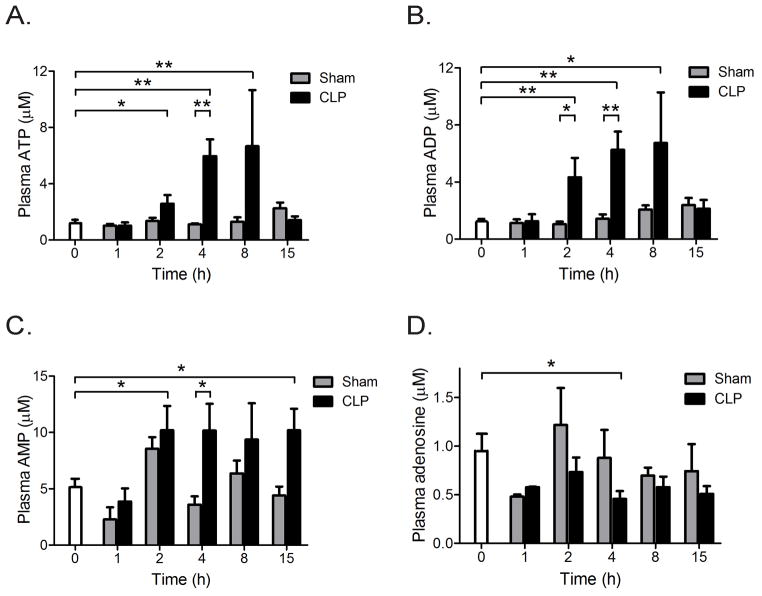

Plasma ATP increases during sepsis

Plasma ATP concentrations in mice were assessed at different time points before and after surgery without or with CLP to induce poly-microbial sepsis. In CLP animals, the average plasma ATP levels rose over time and peaked 8 h after CLP (Fig. 1A). These ATP concentrations were ~6 times higher than those in sham animals. The highest plasma ATP concentrations measured were ~10 μM. Previous studies have shown that such ATP concentrations have profound co-stimulatory effects on human PMN (16). In addition to ATP, we found that the concentrations of ADP and AMP were also significantly elevated in CLP animals when compared to sham controls (Figs. 1B&C). However, the average adenosine concentrations in CLP animals were similar to those in the sham control group and appeared to decline over time in sham and CLP animals (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1. Increased plasma nucleotide concentrations in a mouse sepsis model.

Mice were subjected to sham surgery or cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) to induce sepsis. Plasma concentrations of ATP (A), ADP (B), AMP (C), and adenosine (D) were assessed by HPLC before (0 h) and at the indicated time points after sham surgery or CLP (n=7 for each data point, mean ± SEM, Unpaired t-test, *p<0.05, **p<0.01).

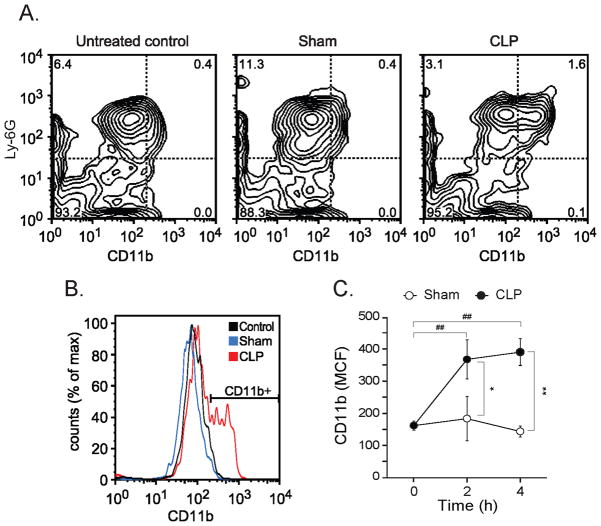

Sepsis causes profound PMN activation

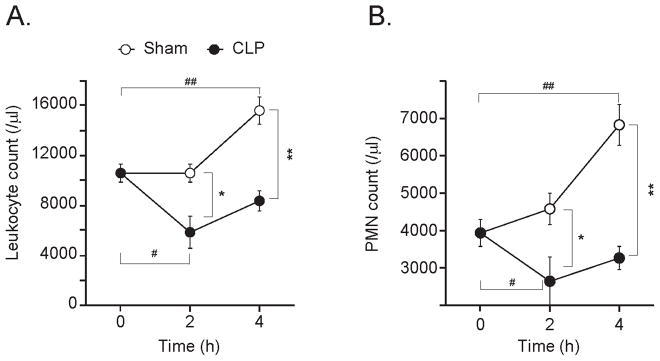

Blood leukocyte and PMN counts in the sham group but not in the CLP group were significantly higher than in untreated controls (Fig. 2). In septic mice, leukocyte and PMN counts were lower than in untreated controls and sham animals. These findings are consistent with post-surgical inflammation and leukocytosis in sham mice. The decrease in leukocyte and PMN counts in CLP mice is consistent with increased PMN adherence the endothelium and sequestration to the site of infection in the abdomen.

Fig. 2. Circulating leukocyte and PMN counts.

The total numbers of leukocytes (A) and PMN (B) in heparinized mouse blood were assessed at the indicated times before (time=0 h) and at the indicated times after sham surgery (open circles) or CLP (closed circles). Each points represents values of 10 animals (n=10; mean ± SEM, Mann-Whitney test, *p<0.05, **p<0.01 comparing groups, #p<0.05, ##p<0.01 compared to controls at 0 h).

In support of this notion, we found that PMN in CLP animals were significantly more activated than PMN in untreated control mice and in sham animals (Fig. 3). Whole blood samples were stained with antibodies that recognize the PMN marker Ly-6G and the adhesion and activation marker CD11b. CD11b expression of Ly-6G positive cells was analyzed by flow cytometry (Fig. 3A&B). Four hours after the onset of sepsis, PMN of CLP animals expressed significantly higher levels of CD11b compared to untreated controls and sham animals (Fig. 3C). In addition, a significantly larger portion (~30%) of PMN in CLP mice showed elevated CD11b expression when compared to untreated and sham controls (data not shown). Taken together, these findings indicate robust PMN activation in septic mice but not in sham controls.

Fig. 3. CLP induces PMN activation.

PMN activation was assessed 4 h after surgery without or with CLP by determining the abundance of CD11b on the surface of Ly-6G-positive neutrophils (MCF). Panels A&B show representative flow cytometry results of untreated control mice, sham animals, and CLP animals. Panel C shows CD11b (MCF) data of sham and CLP group at the indicated time points (n=12 per group, mean ± SEM, Mann-Whitney test, *p<0.05, **p<0.01 comparing groups, ##p<0.01 compared to controls at 0h).

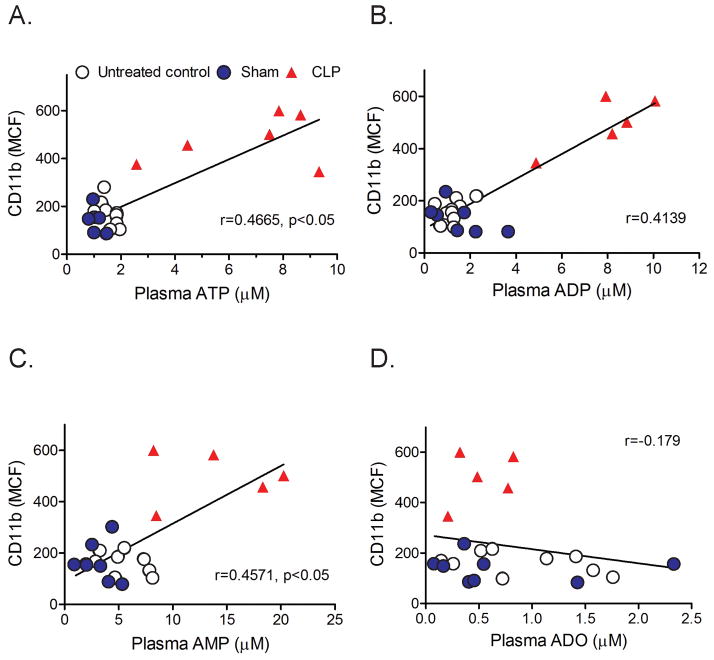

PMN activation correlates with plasma ATP concentrations

Our previous work has shown that ATP release from stimulated PMN and autocrine feedback via P2Y2 receptors on the cell surface of PMN are essential for neutrophil activation (7). These autocrine purinergic signaling mechanisms are susceptible to influence by exogenous ATP, for example by ATP released from damaged cells or injured tissues. Therefore, circulating ATP in sepsis animals could contribute to the activation PMN in these animals. Comparisons of CD11b expression and plasma ATP concentrations revealed significant positive correlations which suggest that plasma ATP levels contribute to PMN activation in CLP animals (Fig. 4A, suppl. Fig. 1). Not only concentrations of ATP but also of its metabolites ADP and AMP showed positive correlations with CD11b expression (Fig. 4B&C, suppl. Fig. 1). Our findings suggest that ATP in plasma of septic animals promotes PMN activation in response to sepsis.

Fig. 4. PMN activation correlates with circulating plasma ATP levels.

Activation of PMN (CD11b expression of Ly-6G-positve cells) was assessed in untreated control (open circles) or in sham (closed blue circles) or CLP animals (red triangles) 4 h after surgery. Data are plotted over the corresponding plasma ATP (panel A), ADP (panel B), AMP (panel C), and adenosine (panel D) concentrations (n=7 in each group, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient).

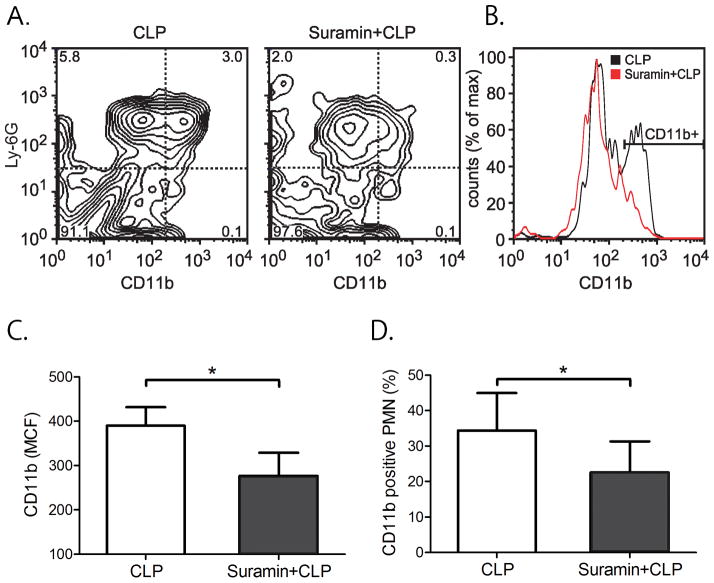

Suramin reduces PMN activation in sepsis

The data above suggested that extracellular ATP promotes PMN activation in sepsis. This process likely involves the stimulation of P2Y2 receptors, which are the most abundant ATP receptor subtype expressed in PMN. Thus, we hypothesized that the P2 receptor antagonist suramin should be able to reduce PMN activation in our mouse sepsis model. To test this possibility, we treated mice with suramin prior to CLP. Suramin was administered subcutaneously as a bolus injection of 4 μl per gram bodyweight of a 1 mM suramin stock solution. Animals were euthanized after 4 h and blood was collected to assess PMN activation by measuring CD11b expression of Ly-6G-positve cells. Suramin treatment caused a significant reduction in PMN activation compared to untreated CLP animals that received vehicle instead of suramin (Fig. 5A&B). Suramin treatment reduced CD11b expression by ~ 30% compared to untreated CLP mice. Suramin reduced both, the average CD11b expression of individual PMN (MCF) and the percentage of CD11b-positive cells (Fig. 5C&D).

Fig. 5. Suramin reduces PMN activation after sepsis.

Mice were subjected to CLP with or without suramin treatment. PMN activation was assessed by determining CD11b expression of Ly-6G-positive neutrophils 4 h after CLP. Panels A&B show representative data while panels C&D show CD11b expression data of Ly-6G-positive neutrophils with 4 animals in each group (n=4, mean ± SEM, unpaired t test, *p<0.05).

DISCUSSION

This study revealed that sepsis is associated with a marked increase in circulating ATP concentrations and that these ATP levels contribute to PMN activation in a mouse sepsis model. Sepsis is a complex pathological process. The clinical consequences of sepsis depend on many factors including the type of bacteria, the bacterial load and site of infection, the effectiveness of the host’s immune defense against the invading bacteria, and the extent of collateral tissue damage caused by PMN and other immune cells in their fight against the invaders (5). The balance between these diverse processes ultimately determines the severity and outcome of sepsis. While PMN form the first line of defense against invading pathogens, they can contribute to morbidity and mortality by promoting pathophysiological processes that damage host organs and cause multiple organ failure syndrome during sepsis (5, 21). Despite the complexity of these events, inhibition of excessive PMN activation is thought to benefit sepsis victims by reducing secondary organ damage.

Our previous work has shown that autocrine and paracrine purinergic signaling mechanisms have a central role in regulating PMN activation (7). ATP can be released from cells as a consequence of cell damage, hypoxia, osmotic stimulation, or mechanical stress (10, 20, 22, 23). Recent animal studies have shown that ATP is released from inflamed tissues, resulting in the accumulation of extracellular ATP at concentrations sufficient to stimulate P2 receptors (24). Thus, ATP released into the circulation can influence the autocrine purinergic signaling mechanisms that govern PMN activation (7). Our current study revealed that a large amount of circulating ATP is generated during sepsis and that this ATP promotes PMN activation. This suggests that systemic ATP levels have a critical role in regulating PMN activation during sepsis by stimulating P2 receptors of PMN. This mechanism could be akin to mechanisms described in NALP3 inflammasome activation that involve P2X7 receptors and result in the production of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 by macrophages (25, 26).

We found in our mouse sepsis model that plasma ATP concentrations correlate with PMN activation and that blocking P2 receptors with suramin diminishes PMN activation. Although further studies are required to define the sources of ATP in the plasma of sepsis animals, it is intriguing to speculate that bacteria themselves or the inflammatory responses triggered by them may contribute to these increased plasma ATP levels. This may help trigger the very response that leads to PMN-induced clearance of invading bacteria. However, the same mechanism could also exacerbate the collateral damage caused by PMN resulting in end organ damage after sepsis. P2Y2 receptors, the predominant P2 receptor subtype in PMN has an EC50 of 0.23 ± 0.01 μM ATP (27). Therefore, the plasma ATP concentrations we found in septic mice (up to ~ 12 μM) are well within the range that can activate these receptors. By contrast, P2X7 receptors require much higher ATP concentrations (>100 μM) for half maximal receptor stimulation (28). Thus the circulating ATP concentrations in septic mice are more likely to exert their immunomodulatory effects via P2Y2 receptors rather than the P2X7 receptors involved in inflammasome activation.

As mentioned above, P2Y2 receptors are the predominant ATP receptors in human PMN (27). P2Y2 receptor expression can be up-regulated in a variety of pathophysiological conditions associated with inflammation and tissue damage resulting in altered PMN responses (29). Our previous work has shown that inhibition of P2Y2 receptors blocks degranulation, oxidative burst, and chemotaxis (7). Furthermore, we found that neutrophil recruitment and organ damage in P2Y2 receptor KO mice was reduced when compared to wild type controls subjected to CLP (19). These findings suggest that blocking PMN can be a double-edged sword that can either benefit or harm the host. Suramin, is a non-specific P2 receptor antagonist with a reported IC50 value of 48 μM for P2Y2 receptors (30). We found that suramin inhibited PMN activation in our sepsis model. However, suramin can also block P2 receptors of other inflammatory cells and thereby elicit complex effects on the host response to sepsis (31). The Ly-6G antibody used in our study can also bind to monocytes. Therefore, the observations made in our study may also reflect in part the response of monocytes to plasma ATP concentrations.

Extracellular ATP can be hydrolyzed by several families of ectonucleotidases including CD39 (ENTPD1; ecto-nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 1) and CD73 (ecto-5′-nucleotidase) that catalyze the conversion of ATP and ADP to AMP and adenosine, respectively (32, 33). Thus, these ectonucleotidases have key roles in regulating extracellular ATP concentrations. Our current results show that plasma concentrations of ATP, ADP, and AMP are elevated in the plasma of septic mice (Fig. 1) and that these elevated nucleotide levels go hand-in-hand with enhanced PMN activation (Fig. 4). Under normal physiological circumstances, plasma ATP levels are tightly maintained at low levels by ectonucleotidases such as CD39 (32). However, various pathological conditions can affect this ATP scavenging system, potentially resulting in altered immune responses (34, 35). The role of this ATP scavenging system in the regulation of the host response to sepsis remains to be defined.

In summary, we conclude that high levels of circulating ATP can promote PMN activation which may benefit the host immune defense. However, excessive PMN activation may also contribute to host tissue damage. Taken together with our previous work, our current findings suggest that PMN responses can be modulated with therapeutic strategies that target the autocrine purinergic signaling mechanisms of PMN. Additional studies are needed to determine whether and how these purinergic signaling mechanisms can be targeted in order to benefit patients with sepsis.

Supplementary Material

The percentages of activated PMN (percent of CD11b positive and Ly-6G-positve cells) were assessed in untreated control (open circles) or in sham (closed blue circles) or CLP animals (red triangles) 4 h after surgery with or without CLP. Data are plotted over the corresponding plasma ATP (panel A), ADP (panel B), AMP (panel C), and adenosine (panel D) concentrations (n=7 in each group, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (23792086; to Y.S.) and by grants from the National Institutes of Health (GM-51477, GM-60475, AI-072287, AI-080582; to W.G.J.).

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Perl M, Hohmann C, Denk S, Kellermann P, Lu D, Braumuller S, Bachem MG, Thomas J, Knoferl MW, Ayala A, Gebhard F, Huber-Lang MS. Role of activated neutrophils in chest trauma-induced septic acute lung injury. Shock. 2012;38(1):98–106. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318254be6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lange M, Szabo C, Traber DL, Horvath E, Hamahata A, Nakano Y, Traber LD, Cox RA, Schmalstieg FC, Herndon DN, Enkhbaatar P. Time profile of oxidative stress and neutrophil activation in ovine acute lung injury and sepsis. Shock. 2012;37(5):468–72. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31824b1793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC, Abraham E, Angus D, Cook D, Cohen J, Opal SM, Vincent JL, Ramsay G. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(4):1250–6. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000050454.01978.3B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, Annane D, Gerlach H, Opal SM, Sevransky JE, Sprung CL, Douglas IS, Jaeschke R, Osborn TM, Nunnally ME, Townsend SR, Reinhart K, Kleinpell RM, Angus DC, Deutschman CS, Machado FR, Rubenfeld GD, Webb SA, Beale RJ, Vincent JL, Moreno R. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(2):580–637. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827e83af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Angus DC, van der Poll T. Severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(9):840–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1208623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Botha AJ, Moore FA, Moore EE, Sauaia A, Banerjee A, Peterson VM. Early neutrophil sequestration after injury: a pathogenic mechanism for multiple organ failure. J Trauma. 1995;39(3):411–7. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199509000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Y, Yao Y, Sumi Y, Li A, To UK, Elkhal A, Inoue Y, Woehrle T, Zhang Q, Hauser C, Junger WG. Purinergic signaling: a fundamental mechanism in neutrophil activation. Sci Signal. 2010;3(125):ra45. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Junger WG. Immune cell regulation by autocrine purinergic signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11(3):201–12. doi: 10.1038/nri2938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bours MJ, Swennen EL, Di Virgilio F, Cronstein BN, Dagnelie PC. Adenosine 5′-triphosphate and adenosine as endogenous signaling molecules in immunity and inflammation. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;112(2):358–404. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schenk U, Westendorf AM, Radaelli E, Casati A, Ferro M, Fumagalli M, Verderio C, Buer J, Scanziani E, Grassi F. Purinergic control of T cell activation by ATP released through pannexin-1 hemichannels. Sci Signal. 2008;1(39):ra6. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.1160583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woehrle T, Yip L, Elkhal A, Sumi Y, Chen Y, Yao Y, Insel PA, Junger WG. Pannexin-1 hemichannel-mediated ATP release together with P2X1 and P2X4 receptors regulate T-cell activation at the immune synapse. Blood. 2010;116(18):3475–84. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-277707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yip L, Woehrle T, Corriden R, Hirsh M, Chen Y, Inoue Y, Ferrari V, Insel PA, Junger WG. Autocrine regulation of T-cell activation by ATP release and P2X7 receptors. FASEB J. 2009;23(6):1685–93. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-126458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elliott MR, Chekeni FB, Trampont PC, Lazarowski ER, Kadl A, Walk SF, Park D, Woodson RI, Ostankovich M, Sharma P, Lysiak JJ, Harden TK, Leitinger N, Ravichandran KS. Nucleotides released by apoptotic cells act as a find-me signal to promote phagocytic clearance. Nature. 2009;461(7261):282–6. doi: 10.1038/nature08296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chekeni FB, Elliott MR, Sandilos JK, Walk SF, Kinchen JM, Lazarowski ER, Armstrong AJ, Penuela S, Laird DW, Salvesen GS, Isakson BE, Bayliss DA, Ravichandran KS. Pannexin 1 channels mediate ‘find-me’ signal release and membrane permeability during apoptosis. Nature. 2010;467(7317):863–7. doi: 10.1038/nature09413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fredholm BB, APIJ, Jacobson KA, Klotz KN, Linden J. International Union of Pharmacology. XXV. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53(4):527–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Y, Corriden R, Inoue Y, Yip L, Hashiguchi N, Zinkernagel A, Nizet V, Insel PA, Junger WG. ATP release guides neutrophil chemotaxis via P2Y2 and A3 receptors. Science. 2006;314(5806):1792–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1132559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cronstein BN. Adenosine, an endogenous anti-inflammatory agent. J Appl Physiol. 1994;76(1):5–13. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.76.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sitkovsky MV, Ohta A. The ‘danger’ sensors that STOP the immune response: the A2 adenosine receptors? Trends Immunol. 2005;26(6):299–304. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inoue Y, Chen Y, Hirsh MI, Yip L, Junger WG. A3 and P2Y2 receptors control the recruitment of neutrophils to the lungs in a mouse model of sepsis. Shock. 2008;30(2):173–7. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e318160dad4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lazarowski ER, Tarran R, Grubb BR, van Heusden CA, Okada S, Boucher RC. Nucleotide release provides a mechanism for airway surface liquid homeostasis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(35):36855–64. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405367200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alves-Filho JC, de Freitas A, Spiller F, Souto FO, Cunha FQ. The role of neutrophils in severe sepsis. Shock. 2008;30 (Suppl 1):3–9. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181818466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wood RE, Wishart C, Walker PJ, Askew CD, Stewart IB. Plasma ATP concentration and venous oxygen content in the forearm during dynamic handgrip exercise. BMC Physiol. 2009;9:24. doi: 10.1186/1472-6793-9-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trautmann A. Extracellular ATP in the immune system: more than just a “danger signal”. Sci Signal. 2009;2(56):pe6. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.256pe6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bours MJ, Dagnelie PC, Giuliani AL, Wesselius A, Di Virgilio F. P2 receptors and extracellular ATP: a novel homeostatic pathway in inflammation. Front Biosci (Schol Ed) 2011;3:1443–56. doi: 10.2741/235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qu Y, Ramachandra L, Mohr S, Franchi L, Harding CV, Nunez G, Dubyak GR. P2X7 receptor-stimulated secretion of MHC class II-containing exosomes requires the ASC/NLRP3 inflammasome but is independent of caspase-1. J Immunol. 2009;182(8):5052–62. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qu Y, Franchi L, Nunez G, Dubyak GR. Nonclassical IL-1 beta secretion stimulated by P2X7 receptors is dependent on inflammasome activation and correlated with exosome release in murine macrophages. J Immunol. 2007;179(3):1913–25. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.3.1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abbracchio MP, Burnstock G, Boeynaems JM, Barnard EA, Boyer JL, Kennedy C, Knight GE, Fumagalli M, Gachet C, Jacobson KA, Weisman GA. International Union of Pharmacology LVIII: update on the P2Y G protein-coupled nucleotide receptors: from molecular mechanisms and pathophysiology to therapy. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58(3):281–341. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peng W, Cotrina ML, Han X, Yu H, Bekar L, Blum L, Takano T, Tian GF, Goldman SA, Nedergaard M. Systemic administration of an antagonist of the ATP-sensitive receptor P2X7 improves recovery after spinal cord injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(30):12489–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902531106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Degagne E, Grbic DM, Dupuis AA, Lavoie EG, Langlois C, Jain N, Weisman GA, Sevigny J, Gendron FP. P2Y2 receptor transcription is increased by NF-kappa B and stimulates cyclooxygenase-2 expression and PGE2 released by intestinal epithelial cells. J Immunol. 2009;183(7):4521–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muller CE. P2-pyrimidinergic receptors and their ligands. Curr Pharm Des. 2002;8(26):2353–69. doi: 10.2174/1381612023392937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ben Yebdri F, Kukulski F, Tremblay A, Sevigny J. Concomitant activation of P2Y(2) and P2Y(6) receptors on monocytes is required for TLR1/2-induced neutrophil migration by regulating IL-8 secretion. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39(10):2885–94. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yegutkin GG. Nucleotide- and nucleoside-converting ectoenzymes: Important modulators of purinergic signalling cascade. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1783(5):673–94. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hasko G, Linden J, Cronstein B, Pacher P. Adenosine receptors: therapeutic aspects for inflammatory and immune diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7(9):759–70. doi: 10.1038/nrd2638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Imai M, Kaczmarek E, Koziak K, Sevigny J, Goepfert C, Guckelberger O, Csizmadia E, Schulte Am Esch J, 2nd, Robson SC. Suppression of ATP diphosphohydrolase/CD39 in human vascular endothelial cells. Biochemistry. 1999;38(41):13473–9. doi: 10.1021/bi990543p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robson SC, Kaczmarek E, Siegel JB, Candinas D, Koziak K, Millan M, Hancock WW, Bach FH. Loss of ATP diphosphohydrolase activity with endothelial cell activation. J Exp Med. 1997;185(1):153–63. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.1.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The percentages of activated PMN (percent of CD11b positive and Ly-6G-positve cells) were assessed in untreated control (open circles) or in sham (closed blue circles) or CLP animals (red triangles) 4 h after surgery with or without CLP. Data are plotted over the corresponding plasma ATP (panel A), ADP (panel B), AMP (panel C), and adenosine (panel D) concentrations (n=7 in each group, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient).