Summary

Members of the SH2 domain family modulate signal transduction by binding to short peptides containing phosphorylated tyrosines. Each domain displays a distinct preference for the sequence context of the phosphorylated residue. We have developed a new high-density peptide chip technology that allows probing the affinity of most SH2 domains for a large fraction of the entire complement of tyrosine phosphopeptides in the human proteome. Using this technique we have experimentally identified thousands of putative SH2- peptide interactions for more than 70 different SH2 domains. By integrating this rich data set with orthogonal context-specific information, we have assembled an SH2 mediated probabilistic interaction network, which we make available as a community resource in the PepSpotDB database. A new predicted dynamic interaction between the SH2 domains of the tyrosine phosphatase SHP2 and the phosphorylated tyrosine in the ERK activation loop was validated by experiments in living cells.

Keywords: SH2, protein interaction domains, protein networks, domain recognition specificity

Introduction

Post-translational modifications (PTMs) and modular protein domains underlie a dynamic protein interaction networks and represent one of the key organizing principles in cellular systems (Pawson, 2004). In particular kinases modulate cell response to growth signals by adding phosphate groups to short linear sequence motifs in their substrates. These phosphorylated residues, in turn, serve as docking sites for proteins containing phospho-binding modules such as the SH2, PTB and BRCT domains (Yaffe, 2002). The SH2 domain family includes a total of 120 domains in 110 proteins and, as such, represents the largest class of pTyr recognition domains (Liu et al., 2006). The peptide recognition preference of each member of this large domain family has been the subject of a number of studies with genome wide perspective. The pioneering work of Cantley’s group exploited oriented peptide libraries to characterize the preference for specific residues in the positions flanking the phosphorylated tyrosine in the targets of 14 SH2 domains (Songyang et al., 1993). Machida and collaborators used a far western approach and a new strategy termed “reverse phase protein array” to profile nearly the full complement of the SH2 domain family (Machida et al., 2007). This strategy allowed to classify SH2 domains according to their ability to bind classes of phosphorylated proteins, but lacked sufficient resolution to precisely define recognition specificity and to permit to identify the targets of each SH2 containing protein. Another approach exploited OPAL, a variant of the oriented peptide library approach, to derive position specific scoring matrices for 76 of the 120 human SH2 domains (Huang et al., 2008). Finally the full complement of human SH2 domains was arrayed on glass chips and probed with a collection of phospho-tyrosine peptides from the ErbB receptor family (Jones et al., 2006). This latter strategy offers the advantage of directly addressing the interactions with specific phosphopeptides from the human proteome and of being amenable to quantitative analysis. However, the throughput of its present implementation does not permit screening of the entire human phosphoproteome. These approaches have represented a considerable advancement in our understanding of the recognition specificity within this domain family and taken together they have contributed to characterize approximately two thirds of the SH2 domains.

We have addressed the problem from a different angle by developing and exploiting a new technology that permits to probe the recognition specificity of each phosphotyrosine binding domain on a high density peptide chip containing nearly the full complement of tyrosine phosphopeptides in the human proteome. In addition we integrate this in vitro experimental data with orthogonal genome wide datasets to propose an SH2 mediated probabilistic interaction network taking into account in vitro affinity data and in vivo contextual evidence. Finally, we have captured from the published literature more than 800 experimental evidences pertaining to SH2 recognition specificity and we have used this information as a gold standard to benchmark our predictors.

Our strategy combines harnessing the strengths of a new powerful experimental assay and integrating its quantitative output with a wide range of orthogonal genome wide context information. The raw experimental data and the probabilistic network can be accessed and explored in the context of the SH2 domain interaction curated from literature in a new publicly available resource: the PepSpot database http://mint.bio.uniroma2.it/PepspotDB/.

Results and Discussion

Phosphotyrosine peptide chips: a nearly complete complement of the human phosphotyrosine proteome

The SPOT synthesis approach (Frank, 1992) is based on the ability to synthesize a few thousands oligopeptides in an ordered array on a cellulose membrane. This approach has been extensively used to study protein interactions when one of the partners can be represented as a short unconstrained peptide. For this project we have moved forward the approach by increasing by approximately one order of magnitude the number of peptides that can be tested in a single experiment (Fig. 1). This is based on the ability to 1) synthesize several thousand peptides by spatially addressed SPOT synthesis, 2) punch-press the peptide spots into wells of microtiter plates, 3) release peptides from resulting cellulose-discs and 4) print them onto aldehyde modified glass surfaces resulting in high density peptide chips displaying the probes in three identical replicates.

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of the strategy to draw an SH2 mediated protein interaction network.

See also supplementary Figure S1 and Supplementary Table S1.

The tyrosine phosphopeptide chip (pTyr-chip) used in this work was initially designed to represent most of the phospho-proteome known when this project had started. At that time the PhosphoELM (Diella et al., 2008) and Phosphosite (Hornbeck et al., 2004) databases contained 2198 tyrosine phosphopeptides. This collection of experimentally determined phosphopeptides was completed with approximately 4000 additional peptides having a high probability of being phosphorylated according to the NetPhos predictor (Blom et al., 1999). Overall 6202 phosphopeptides, thirteen residues long with the pTyr in the middle position, were printed in triplicates with appropriate controls (Supplementary Table S1). Each pTyr-chip can be used to profile the recognition specificity of a phospho-tyrosine binding domain fused to a tag and revealed with an anti tag fluorescent antibody.

Profiling the recognition specificity of the SH2 domain family

The pTyr-chips were used to profile a collection of 99 human SH2 domains fused to GST (Supplementary Table S2) (Machida et al., 2007). Experimental reproducibility ranged from 0.7 to 0.99 Pearson’s correlation coefficient (PCC), with most results being well over 0.95, when two replica arrays are compared (intra-chip reproducibility), and of approximately 0.95 in two independent experiments carried out with two different preparations of the same domain (inter-chip reproducibility) (see supplementary Figures S1 and supplementary Table S3).

Among the 99 domains in the collection 26 did not express as a soluble product and 3 gave a poor signal in the peptide chip assay. Only experiments with replica arrays having a Pearson’s correlation coefficient higher than 0.7 were considered for further analysis. Overall 70 domains gave a satisfactory result by this approach. The specificity of 15 of them had never been described before.

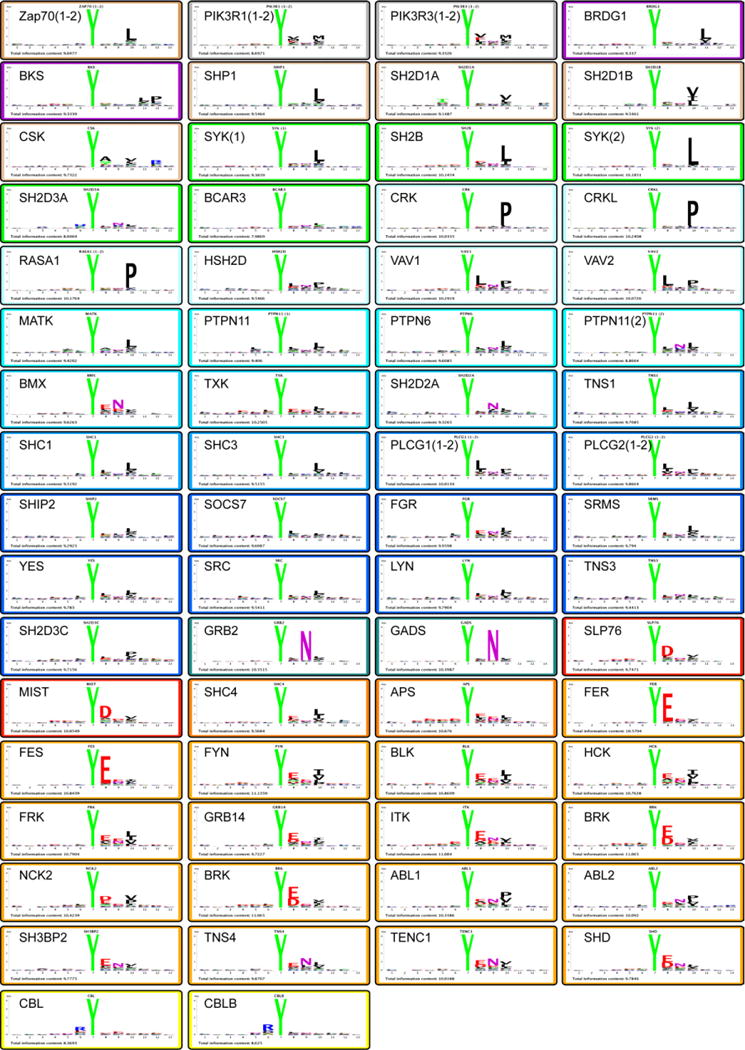

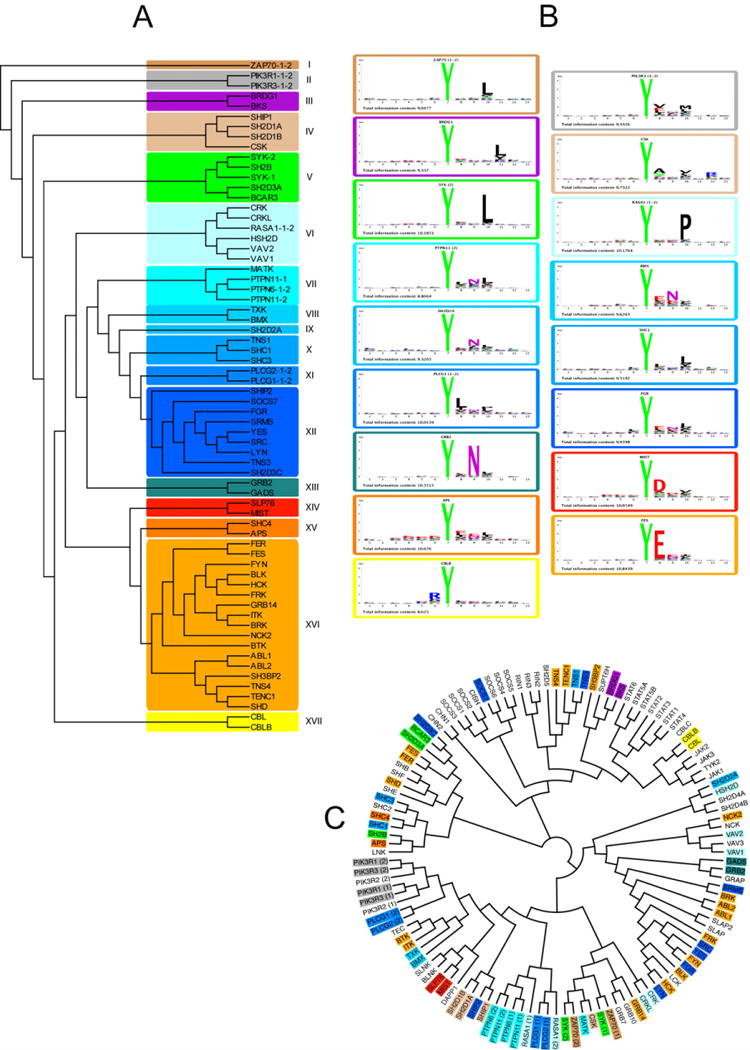

The sequences of the peptides whose binding signal exceeded the average signal by more than two standard deviations (Z score >2) were aligned and used to draw sequence logos illustrating the preferred binding motif of each domain (Figure 2). Differently from what has been recently described for PDZ, SH3 and WW domains (Gfeller et al., 2011) we could not find evidence for multiple specificities for any of the characterized SH2 domains. The results of the profiling experiments were used to cluster the domains according to their preference for phosphotyrosine sequence context (Fig. 3 A). Based on the resulting tree, we arbitrarily define 17 specificity classes characterized by representative amino acid sequence Logos (Figure 3 B). In Figure 3 C we have drawn a second tree where SH2 domains are clustered according to homology in their primary sequence. Specificity class membership is illustrated by background colors matching the colors in panel A. Although closely related domains tend to be member of the same class, the correlation between sequence homology over the whole domain and peptide recognition specificity is overall poor (PCC=0.30, See supplementary Fig. S2). This is consistent with the results of Machida and collaborators (Machida et al., 2007) who failed to identify a correlation between domain sequence and band patterns in far-western type experiments. Attempts to identify diagnostic residues that would help assigning uncharacterized domains to specificity classes by the MultiHarmony software (Brandt et al., 2010) have not been successful. The finding that little divergence in sequence homology can account for relatively large changes in binding specificity is consistent with the reported observations that a few amino acid changes are sufficient to induce a specificity shift in peptide recognition modules such as SH2, SH3 and PDZ (Ernst et al., 2009; Marengere et al., 1994; Panni et al., 2002) and have implications for the interpretation of the observed rapid evolution of protein interaction networks (Kiemer et al 2007) (Kiemer and Cesareni, 2007).

Figure 2. Sequence logos representing the recognition specificity of the SH2 domain family.

For each SH2 domain, the peptides whose binding signal was higher than the average signal plus two standard deviations were aligned on the phosphorylated tyrosine. These peptides were used to draw the peptide logos by a Logo drawing tool implemented in the PepSpot database (see Extended Results in Supplementary materials). Domain Logos of the same specificity class are framed in identical colors. The Logo total information content is also indicated in each frame (See also Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 3. Classification of SH2 domain specificity.

To draw the recognition specificity tree in A we computed the amino acid frequency at each of the13 positions of the SH2 binding peptides to compile a 73 (SH2 domains) × 240 (12 positions × 20 amino acids) matrix describing the domain specificity as amino acid frequencies at each of the 12 positions. We excluded from the analysis the peptide position corresponding to the invariant phosphotyrosine. This matrix was used as input for EPCLUST (http://www.bioinf.ebc.ee/EP/EP/EPCLUST/) to cluster the domains by using the algorithm “linear coefficient based distance, Pearson centered”. We next chose an arbitrary branch depth to identify the 17 specificity classes highlighted with different colors in the figure. B) Amino acid logos for one representative domain for each specificity class. C) The SH2 domain sequences were aligned with the ClustalW algorithm (4) and the homology tree was drawn with the FigTree program, (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree1). Each domain name is highlighted with a background color corresponding to the specificity class in A (See supplementary Table S3).

Liu and collaborators have proposed that non-permissive amino acid residues, opposing binding, could play a role in shaping SH2 domain recognition specificity (Liu et al., 2010). We have confirmed that some SH2 ligands dislike specific residues at specific positions (Supplementary Fig. S3). However, our comprehensive analysis has failed to confirm that negative selection could play a prominent role in modulating peptide recognition specificity within the defined specificity classes.

Artificial neural network predictors of SH2 binding

The pTyr-chip used in this work was initially designed to contain most of the human phosphotyrosine-peptides that were known at the start of this project. However, the recent developments of mass spectrometry based technology has caused an explosion of information and the collection of phosphorylated peptides contained in databases (Diella et al., 2008; Hornbeck et al., 2004) now significantly exceeds the number of experimentally verified peptides represented in our array. Thus, in order to be able to offer a resource that could reliably infer the SH2 ligands of any recently discovered phosphopeptide we developed artificial neural network (ANN) predictors (NetSH2) for each of the 70 profiled SH2 domains (see Methods).

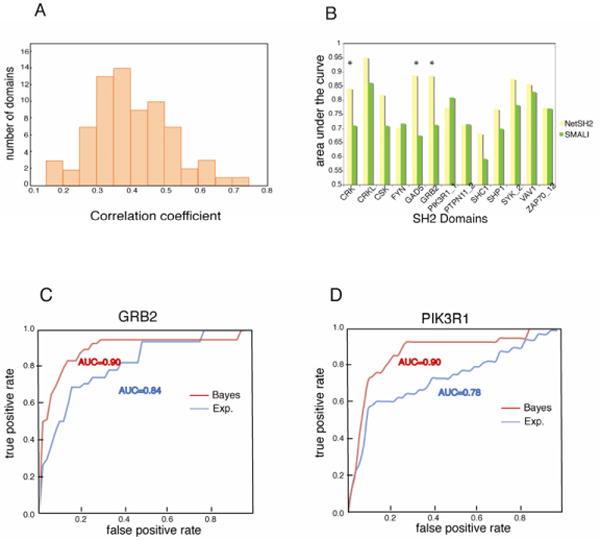

To utilize all the information from pTyr-chips, the peptide sequences and normalized log-ratio intensities were used as input for the ANN. In this way we trained the ANNs to predict if a given peptide is a weak or a strong binder of a specific SH2 domain. In total 70 predictors were trained with an average Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.4 (Fig. 4). These predictors have been integrated in the Netphorest community resource (Miller et al., 2008).

Figure 4. Benchmarking NetSH2 predictors.

a) Distribution of the Pearson Correlation Coefficients of the 70 NetSH2 predictors. b) Comparison of the area under the curve (AROC) of thirteen pairs of predictors tested against a literature curated dataset. Green bars represent the AROC of the SMALI PSSM predictors while yellow bars are the AROC of the NetSH2 predictors presented here. * denotes a p value <0.05 (see methods). c, d) Receiver operating characteristic curve obtained by plotting true positives versus false positives at varying experimental (blue) or Bayesian (red) score using as gold standard a set of experimentally validated interactions extracted from the literature. The number of the gold standard interactions for PI3K and GRB2 were 31 and 24 respectively (See supplementary Figure S4 and supplementary Table.

Benchmarking the SH2 ANN predictors (NetSH2)

An independent large-scale effort has investigated the substrate specificities of SH2 domains using oriented peptide libraries (Huang et al., 2008). The results are available in a resource, termed SMALI (scoring matrix-assisted ligand identification), which uses position specific scoring matrices (PSSMs) to predict ligands of 76 different SH2 domains. The main difference between PSSMs and ANNs is that the latter can capture nonlinear correlations between residues. In order to compare the performance of SMALI to the ANN developed here, we compiled an independent benchmark data set of the known in vivo ligands of SH2 domains. For this purpose the information from the MINT database (Ceol et al., 2012) was supplemented with new interactions captured by extensive search and curation of published information (see Methods). The integrated interaction list (See supplementary Table S4 and Supplementary Figure S4) was used as the ‘positive’ benchmarking dataset, while the ‘negative’ dataset consisted of phospho-tyrosine peptides from the phospho-ELM database (Diella et al., 2008) that had not been shown to bind any SH2 domain. After discarding benchmark peptides that were more than 90% identical to the ANN training data (see Methods), we evaluated the performance of each predictor based on their receiver operating characteristic curves, which show sensitivity as function of false-positive rate. We summarized each curve in a single number, the area under the ROC curve (AROC), which is a convenient performance measure, since it does not depend on defining a threshold to separate positive predictions from negative ones. Provided that at least eight positive example were left, we were able to benchmark 13 ANN and SMALI predictors with an average AROC of 0.81 and 0.74, respectively (Fig. 4b). Since random performance corresponds to an AROC of 0.5, both methods perform well in predicting in vivo ligands of SH2 domains, even though the data used to develop the methods were based on in vitro screens. However, NetSH2 has a competitive advantage, since it is based on a larger experimental dataset and exploits a higher-order machine learning, which in part can capture the complexity in the interaction motifs that guide SH2-ligand binding.

Functional prediction by integration of contextual information

While the artificial neural network predictors NetSH2 accurately capture and model the actual binding site in a narrow sequence window, they do not take into consideration evidence of the functional relevance of the inferred SH2 mediated complex in a physiological context. Thus, we integrated an additional prediction layer to accommodate functional information (Linding et al., 2007). To this end we developed a “functional” confidence score obtained by integrating, by a Naïve Bayes approach, different contextual evidence. The contextual features that were considered included i) cellular co-localization ii) tissue co-expression, iii) predicted order/disorder, iv) degree of conservation of the sequence of the peptide target in related species and v) graph distance between the supposedly interacting proteins in the human interactome. All the considered features contributed to a different extent to the performance of the predictor (see supplementary Figure S5). The efficiency of the Bayesian predictors, as compared with the ANN predictor, was evaluated by drawing ROC curves and by calculating the Area under the ROC (AROC). Although this analysis is statistically meaningful only for the few SH2 domains for which the “gold standard” of bona fide in vivo interactors is sufficiently large, we can conclude that, in general, the Bayesian predictor performs better or equally well as the experimental score. The results of this analysis for two different domains are displayed in Figure 4 (panel c, d). In the case of PIK3R1 and GRB2, the Bayesian predictors clearly outperform the “experimental” predictors (p-values 0.0006 and 0.1 respectively). Bayesian functional scores were calculated for all possible SH2 domain-phosphopeptide pairs: a total of 955,010 scores were stored in PepspotDB, along with the information that was used to calculate the score.

PepspotDB: a database for the storage and analysis of experiments based on peptide chip technology

The SH2 interactome project yielded a large number of experimental and computationally derived data points. To cope with the associated data management challenge and facilitate the fruition of the data and the integration with published information in a single integrated resource we have developed a new publicly accessible databases, called PepspotDB (http://mint.bio.uniroma2.it/PepspotDB/home.seam) (See also supplementary Table S6).

PepspotDB contains five main data types: (a) raw and processed experimental data points; (b) Neural Network predictions; (c) literature curated interactions; (d) Bayesian context scores. In addition, PepspotDB is tightly integrated with the protein-protein interaction database MINT (Licata et al., 2012). All the Neural Network binding predictions on a set of ~13,600 phosphopeptides retrieved from the PhosphoSite (Hornbeck et al. 2004) and Phospho.ELM databases (Diella et al., 2008) are also stored in the PepspotDB. Among the nearly one million possible combinations of the 70 SH2 containing proteins and 13600 phosphorylated tyrosine peptides, some 10,580 interactions are supported by some signal observed in the peptide chip experiment and 49,175 are computationally predicted by the Neural Network algorithm, the overlap being 4,207 interactions. This latter set of domain-peptide interactions with both experimental and computational support is enriched in interactions confirmed by published experiments (p-value < 1.11·10−16 by the hypergeometric test) and can thus be deemed high-confidence.

PepspotDB comes with a rich web application providing a user friendly interface for easy information retrieval. The information provided with each retrieved interaction includes: experimental, computational and contextual evidence supporting the interaction, cross-references to MINT records describing an interaction between the domain containing protein and the peptide containing protein, and links to published articles reporting the currently displayed domain-peptide interaction. Query results can be downloaded in text format for further analysis. See supplementary material for a more detailed description of the database and a guide to its use.

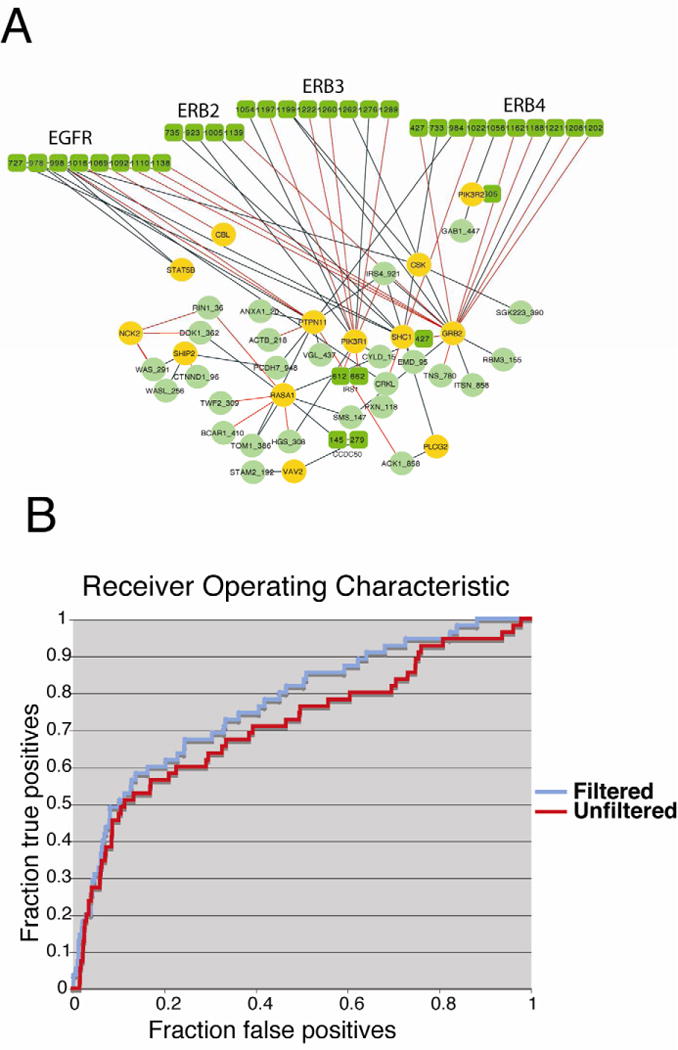

Experimental validation by phosphopeptide pull down

In order to validate the prediction based on peptide chip experiments we used 57 synthetic phosphopeptides linked to magnetic beads to affinity purify ligand proteins from extracts of HeLa cells stimulated with EGF. To increase the statistical significance of the analysis we integrated already published data (25 phosphopeptide baits) (Schulze et al., 2005) with new experiments (32 phosphopeptide baits). This bait collection contains a large fraction of peptides (Supplementary Table S5) that are phosphorylated on tyrosines upon stimulation of receptor kinases of the EGFR family. Affinity purified proteins were identified by liquid chromatography coupled to high-resolution mass spectrometry. The recovered proteins mostly contain SH2 domains with a few exceptions. Overall these pull down experiments define a network of 47 proteins linked by 85 interactions (Figure 5A). Differently from “traditional” protein interaction graphs, many proteins in this graph are represented as covalently linked nodes, where each node is an independent binding domain (Santonico et al., 2005). This representation is made possible by the resolution of the interaction information obtained by this approach and allows to distinguish whether the interactions engaged by a highly connected protein are mutually exclusive or rather involve different binding regions and are mutually compatible.

Figure 5. Comparison between experimentally verified and predicted interactions.

A) The graph represents all the interactions detected by pull down experiments. Proteins are labeled with their gene names. SH2 containing proteins are represented as yellow circles while proteins containing target phosphopeptides are in green. Proteins containing multiple SH2 target sites are represented as covalently linked multiple nodes labeled with the coordinates of the phosphorylated tyrosines. Interactions that are also supported by the Neural Network predictors (z score >2) are drawn in red. B) Receiver operating characteristic curve obtained by plotting true positives and false positives at varying neural network score. The red curve is obtained by using a ranked list limited to predictions of interactions with SH2 domains that have ever been identified in HeLa cells. (See also supplementary Figure S4 and S5 and supplementary Tables S4,S5,S6).

Only 45 of the 125 SH2 containing proteins have ever been identified by LC-MS experiments in HeLa cells (Blagoev et al., 2004; Wisniewski et al., 2009) (Supplementary Table S6). For 28 of these we had an SH2 specific neural network predictor that could be used to rank the SH2 domains according to their preference for the phosphopeptide baits. Approximately 33% of the interactions determined experimentally were ranked high by the predictors developed in this work, z-score higher than 2 (red edges in the graph in Figure 5A). To measure the performance of our predictors by a more general approach, we plotted a receiver operating characteristic curve using the experimentally derived SH2 containing proteins as positive instances and the remaining as negative ones. The area under the curve (AROC) was 0.81 with a precision (true/false positives) of approximately 0.11 at a recall of 50% (Figure 3B). However, there are a number of reasons why the performance of our predictors is underestimated by this analysis. First, some of the interactions that are predicted by the neural network might have been missed by the affinity purification experiment because of the low abundance of the corresponding SH2 protein partners. In addition some of the proteins may bind to the bead-linked phospho-peptide by a domain that is different from SH2. For instance the protein SHC1 has a second domain (PTB) that binds phosphopeptides containing the NPxpY motif. Indeed more than 50% of the phosphopeptides that affinity purified SHC1 contain this or related motifs. Finally some of the interactions detected by pull down could be indirect. For instance SHC1 and GRB2 form a relatively stable complex upon EGF induction. The SH2 domain of GRB2 binds peptides containing a typical pYxN motif. The observation that SHC1 was detected in most of the pull downs obtained with peptides containing the pYxN GRB2 motif, despite having a different recognition specificity, suggest that SHC1 binds this phosphopeptide beads via a GRB2 bridge. Conversely a SHC1 bridge could explain the indirect binding of GRB2 to peptides containing a NPxpY motif. These considerations explain the relatively poor performance of our SHC1 (and to a lesser extent GRB2) SH2 domain predictor.

The EGF dynamic network

Protein interaction networks are typically pictured as static graphs lacking a time dimension. However, most biological processes are dynamic and protein concentrations and modifications change in time responding to external or internal molecular cues. For instance, after addition of growth factors such as EGF the signal is propagated from the receptor on the membrane to the nucleus via a cascade of modifications, mostly additions and removal of phosphate groups, which in turn promote the association and dissociation of enzymes and adaptors containing phosphopeptide binding domains. Olsen and colleagues (Olsen et al., 2006) have reported the global in vivo phosphorylation dynamics following activation of the EGF receptor in HeLa cells. Overall they have identified 6600 phosphorylation sites on 2244 proteins containing at least one phosphorylated Ser, Thr or Tyr. Of the 293 phospho-tyrosine peptides, identified on 243 proteins, 53 change dynamically their phosphorylation state after incubation with EGF. We have combined this dynamic dataset with our proteome wide prediction of the SH2 target sites to come up with a description of the dynamic association and dissociation of proteins following the activation of the tyrosine kinase signaling cascade.

To this end we downloaded from the HomoMINT database (Chatr-aryamontri et al., 2007; Persico et al., 2005) all the interactions where one of the partners is a protein participating in the EGF pathway according to the Reactome database (Vastrik et al., 2007). Only interactions with a MINT confidence score (Chatr-Aryamontri et al., 2008) higher than 0.4 were considered. This network represents the basal static interactions in the cell. We next downloaded from the PepSpot database all the interactions between SH2 domain containing proteins and the tyrosine containing peptides whose phosphorylation varies with time after EGF stimulation. Interactions with a “final posterior probability” higher than 0.3, according to the Bayesian model developed here, were taken into consideration. This inferred dynamic network was superimposed onto the static literature-derived network. For network legibility all the proteins linked to the network by a single edge were removed. The predicted changes occurring in the dynamic interactome are illustrated in Figure 6A where the proteins containing SH2 domains are in orange and the interactions mediated by peptides whose phosphorylation levels change after EGF stimulation are in red. Five minutes after receptor stimulation several EGFR peptides are phosphorylated and act as receptors for SH2 containing proteins. Many of these interactions are predicted to vanish at time 20 minutes while new ones, mediated by peptides that are phosphorylated late, appear. Some of the inferred interactions such as the ones between the receptor and GRB2, SHC1, PLCG or PI3K have already plenty of support in the literature. Some others have never been reported and might represent new functionally important protein links.

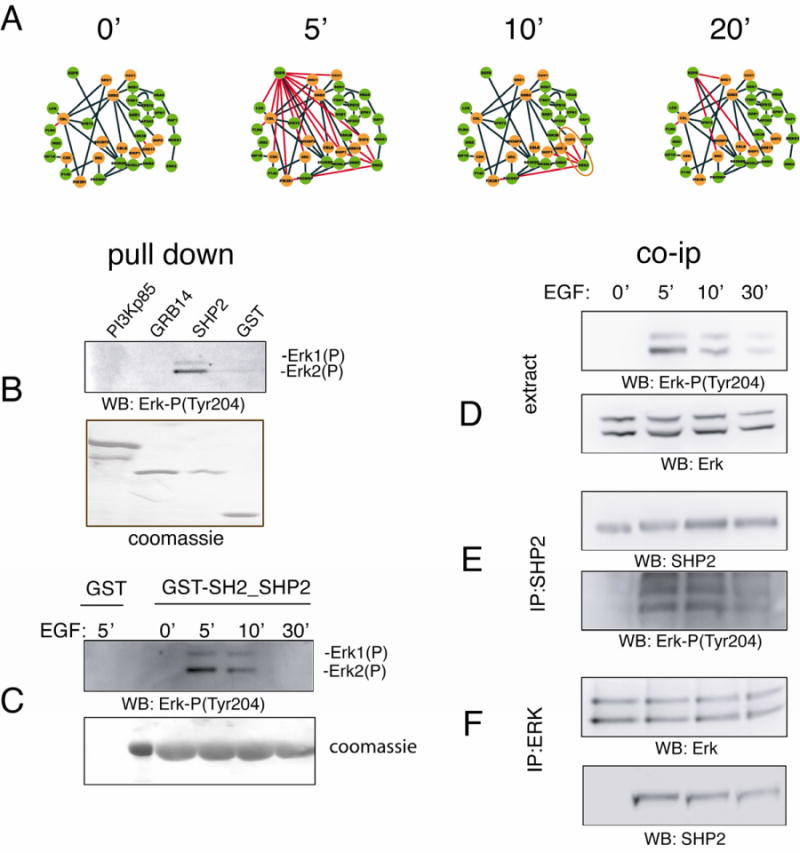

Figure 6. Dynamic EGF network.

The four time-resolved graphs in panel A combine the information about the i) kinetic of tyrosine peptide phosphorylation following incubation with EGF (Olsen et al., 2006), ii) protein protein interaction data mined from the literature and iii) the prediction of SH2 phosphopeptide interactions. Edges representing dynamic interactions mediated by SH2 domains are in red while orange and green circles represent proteins containing or not containing SH2 domains respectively. B) GST fusions of three different SH2 domains (PI3K, GRB14 and SHP2) were used in pull down experiments after incubation of 500 μg of a HeLa cell extract preincubated for 5 minutes with EGF. Affinity purified proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and, after staining with blu coomassie, transferred to membranes and revealed with anti-phospho ERK antibodies. C) After 16 hours starvation (time 0), HeLa cells were induced with EGF for 5, 10 and 30 minutes. Protein extracts were incubated with the tandem SH2 domains of SHP2 expressed as a GST-fusion protein. The affinity purified SH2 ligands were resolved by SDS-PAGE and revealed with anti phospho ERK antibody. D) After starvation, HeLa cells were treated with EGF for 5, 10 and 30 minutes. Cellular lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The blot was incubated with anti phospho ERK and anti ERK antibodies. E) The whole protein extract (1mg) of HeLa cells treated with EGF, was immunoprecipitated with anti SHP2 antibody. Beads were washed with lysis buffer and the immunoprecipitation (IP) was revealed with anti phospho ERK and anti SHP2 antibodies. F) HeLa cells were starved (0′ min) or induced for 5, 10 and 30 minutes with EGF. After cell lysis, 1 mg of protein extract was immunoprecipitated with anti ERK antibody and protein complexes (IP) were separated by SDS-PAGE and revealed with anti ERK and anti SHP2 antibodies.

We focused on the interactions mediated by the SH2 domains of the phosphatase SHP2/PTPN11. SHP2 is known to be activated by binding to phosphorylated GAB1 (Holgado-Madruga et al., 1996). This interaction releases the auto-inhibitory binding between the N-terminal SH2 domain and the phosphatase domain and activates the phosphatase enzymatic activity and via an incompletely understood mechanism promotes a sustained activation of ERK. Our dynamic network recapitulates the interaction between the SH2 domains of SHP2 and GAB1 but in addition predicts a previously unrecognized interaction between the SH2 domains of SHP2 and the phosphorylated Tyr204 in the activation loop of ERK1/2. The results of the pull down and co-immunoprecipitation experiments in Figure 6B clearly show that SHP2 forms a dynamic complex with ERK, starting 5 minutes after incubation with EGF. After 30 minutes we observe a sharp decrease in the amount of immunoprecipitated ERK, which parallels the reduction in ERK phosphorylation levels.

The validation of the predicted dynamic interaction of SHP2 with ERK1/2 attests that the new experimental data presented here, combined with orthogonal genome wide context information, contributes useful hints of new interactions to be experimentally tested for functional relevance. The PepSpotDB provides easy access to these data and related predictions and thus represent a useful resource to shed light on mechanisms that rely on the formation of complexes mediated by phosphotyrosine-peptides.

Experimental Procedures

Peptide arrays

The thirteenmer phosphotyrosine peptides were selected by combining the 2198 peptides that were annotated in the PhosphoELM (Diella et al., 2008) and Phosphosite databases (Hornbeck et al., 2004) at the time we started this project and approximately 4000 additional peptides from the human proteome that received a high score by the NetPhos predictor (Blom et al., 1999). Overall 6202 phosphopeptides, thirteen residues long, were synthesized and printed in triplicate identical arrays with appropriate controls (Supplementary Table S1).

Amino-oxy-acetylated peptides were synthesized on cellulose membranes in a parallel manner using SPOT synthesis technology according to (Frank, 1992; Wenschuh et al., 2000). Following side chain deprotection the solid phase bound peptides were transferred into 96 well microtiter filtration plates (Millipore, Bedford, USA) and treated with 200 μL of aqueous triethylamine (2.5 % by vol) in order to cleave the peptides from the cellulose membrane. Peptide-containing triethylamine solution was filtered off and used for quality control by LC-MS. Subsequently, solvent was removed by evaporation under reduced pressure. Resulting peptide derivatives (50 nmol) were re-dissolved in 25 μL of printing solution (70% DMSO, 25% 0.2 M sodium acetate pH 4.5, 5 % glycerol; by vol.) and transferred into 384-well microtiter plates. Different printing procedures (non-contact printing vs contact-printing) were tested for production of final peptide chips. The best results were reached using contact printing with ceramic pin tools (48 in parallel) on aldehyde modified slides (enhanced surface; Erie Scientific). Printed peptide microarrays were kept at room temperature for 5 hours, quenched for 1 hour with buffered ethanolamine, washed extensively with water followed by ethanol, and dried using microarray centrifuge. Resulting peptide microarrays were stored at 4 °C.

A large manually curated data set of human SH2 mediated interactions

Since the discovery that SH2 domains mediate binding to peptides containing phosphorylated tyrosines (Anderson et al., 1990; Moran et al., 1990), several reports appeared in the literature over the years describing the sequence of peptide ligands for several SH2 domains. We have made an effort to recapture this valuable information, to organize it in a computer readable format and to store it in a database. To this end we have developed a simple text mining approach to recover from the Medline database abstracts containing the text SH2 and a Y followed by a number in a protein interaction textual context. The recovered abstracts were examined by expert curators and whenever the abstract hinted that the manuscript was reporting evidence for an interaction between an SH2 domain and a specific phosphorylated peptide, the manuscript was read through to extract the relevant information. Approximately 50 % of the abstracts recovered by text mining were deemed relevant by the curators.

When this work was in the process, we learned of a similar effort by Gong and collaborators (Gong et al., 2008). The data curated by this group, including 489 SH2 related articles, is available in a public database. 141 of the articles in our curation effort were not present in the PepCyber database while 124 were in common. Among the entries in this latter collection we found 20 discrepancies in the information extracted by the curators. These entries were re-examined and the discrepancies fixed. Finally the PepCyber database contained 365 articles that were not yet curated in our effort. We analyzed these 365 articles and for 135 of them we couldn’t find any experimental evidence supporting an interaction between an SH2 domain and a specific phosphorylated peptide. The remaining 230 articles were re-curated by MINT curators according to the PSI-MI standards and controlled vocabularies (Hermjakob et al., 2004) (See Vent diagram in supplementary Fig. S4).

Training and benchmarking artificial neural networks (NetSH2)

In order to build predictors to infer if a given peptide is weak or a strong ligand of a particular SH2 domain, we employed ANNs of the standard three-layer feed forward type and encoded the amino acids as previously described (Nielsen et al., 2003). Only peptides with a length of 13 and with the phospho-tyrosine residue centrally placed were taken into account. To avoid over fitting the data set was homology reduced using CD-HIT (Li and Godzik, 2006) with default values and 90% sequence identity threshold. These operations reduced the total data set from 6202 peptides to 3896. For each SH2 domains we normalized the log-ratio intensity values to range between 0 and 1, where higher numbers correlate with stronger binding affinity. The data set was divided into four subsets by random partitioning. We trained an ANN on two subsets, determined the optimal network architecture and training parameters on the third subset, and obtained an unbiased performance estimate from the fourth subset. This was repeated in a round-robin fashion to utilize all data for training, test, and validation. For each test set the number of hidden neurons in the ANN (0, 2, 4, 6, 10, 15, 20, and 30) were optimized according to the Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC). The reported PCC performance measure of each ANN was based on the independent validation subsets.

To validate the performance of developed ANNs we used the data set of known in vivo ligands of SH2 domains specifically curated for this work (refer to the ‘gold standard’ data set). This training-independent data set served as the positive instances, while the negatives were compiled of 1307 phospho-tyrosine peptides from phospho.ELM (Diella et al., 2008) that have not previously been shown to bind any SH2 domains. In order not to validate on instances that are identical or highly similar in sequence to what was used to train the ANNs, we used the BLAST algorithm to discard benchmark peptides that were more than 90% identical to the training set. To compare the performance of the ANNs with previously published methods, we ran the benchmark data set through the SMALI method that employs position specific scoring matrices to predict ligands of SH2 domains (Huang et at., 2008). We tested each predictor on its respective validation set and calculated the area under the receiver operating characteristics curve (AROC) for the SH2 domains for which we had at least eight positive instances in the benchmark data set. To test if the observed performance of the PSSMs was significantly different from the ANNs, we constructed bootstrap estimates of the uncertainty associated with each AROC by resampling of the score distributions for positive and negative examples.

Contextual score ranking interactions according to likelihood of functional significance

The Bayesian model supporting the contextual score is based on a number of independent genome wide features describing the probability that the peptide is exposed or in a disordered part of the parent protein, that the SH2 domain protein and its predicted partner are expressed in the same tissues, that they are close in the protein interaction network and conserved in evolution. Finally, we have added the neural network score as a property in the Bayesian inference scheme to give an overall probability of interaction between the SH2 domain and the protein from which the peptide in question was derived.

For each set of possible interactors (SH2 domain containing protein and peptide containing protein), we retrieved information that could help determine whether that particular interaction is likely to take place under physiological conditions.

The “tissue-specific expression” data was taken from Su et al. (Su et al., 2004), and the sub-cellular localization was extracted partly from CellMINT (manuscript in preparation) and partly from GO annotations. Both these sets of data were scored by counting the number of co-occurences of organelle terms and dividing by the highest number of occurrences for either the SH2 domain containing protein or the peptide containing protein, thus obtaining a score between 0 and 1.

“Structural disorder” was determined using IUPred by running the prediction method on the full sequences and then cutting out the relevant part (Dosztanyi et al., 2005). A score between 0 and 1 was obtained by taking the average score of all the residues constituting the peptide.

“Degree of conservation” of the binding site in related species was evaluated by inspecting it in multiple alignments of orthologs and paralogs from ENSEMBL (Flicek et al.). The relevant peptides were cut out of the related sequences and evaluated for binding by the neural networks. The score contribution for each orthologous sequence with the particular domain was calculated by multiplying the neural network score with the overall sequence distance from the original sequence obtained from a neighbour-joining tree. This procedure was followed to award binding site conservation in distant sequences more than that in close sequences. The scores obtained from all the orthologous sequences were added up to produce a single score for each binding site/SH2 domain combination.

Conservation score = sigma_i(dist_sequence(i) * ANN_sequence(i)), where i runs through all orthologous sequences in the alignment for that particular peptide. Finally, the “raw neural network scores” were incorporated in the Bayesian framework as a feature on its own.

To assess the importance of contextual evidence, we applied the Naïve Bayes algorithm:

This computes the probability of interaction given the evidence (P(I|E)). The components of this calculation are the probabilities of seeing each piece of evidence given interaction (PEx|I) and the probability of seeing this evidence in the full set of combinations of domain containing proteins and peptides P(Ex). In practice, this latter probability is calculated by evaluating both the probability of the evidence given interaction and the probability of the evidence given non-interaction (see supplementary Figure S5).

The parameters for the model are determined from a set of known SH2 interactions that was collected and curated manually, deemed ‘the foreground set’, as well as the full range of possible combinations of SH2 domain containing protein and peptides (‘the background set’), assuming that most of these combinations are non-interacting in vivo.

Assembly of the EGF dependent dynamic network

The EGF dependent dynamic network is a graph with a temporal dimension. This is assembled via the following steps.

We first downloaded from the MINT database all the interactions involving as a partner one of the proteins that participate in signal transduction in the EGF pathway, as described in the Reactome pathway database. Only interactions with a MINT confidence score greater than 0.4 were considered. Next we inferred all the possible interactions between SH2 containing proteins and the peptides described by Olsen et al as phosphorylated in tyrosines following EGF stimulation.

Phosphotyrosine peptide pull-downs and mass spectrometric analysis

SILAC Cell Culture and Lysis

Adherent human cervix carcinoma cells (HeLa, ATCC® Number: CCL-2) were SILAC encoded in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium deficient in arginine (Arg) and lysine (Lys), and supplemented with 10% dialyzed fetal calf serum and antibiotics. One cell population was supplied with normal L-Arg and L-Lys (“Light SILAC”), and the other one with the stable isotope-labeled heavy analogues 13C615N4-L-Arginine and 13C615N2-L-Lysine (“Heavy SILAC”). After five cell doublings the cells were lyzed in an ice-cold buffer consisting of 1% NP-40, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mM dithiothreitol, protease inhibitor mixture (Roche complete tablets), and 1 mM sodium ortho-vanadate as tyrosine phosphatase inhibitor. Following centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 15 min the supernatant was used for peptide affinity pulldown experiments.

Peptide Synthesis

Peptides were synthesized as pairs in phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated forms on a solid-phase peptide synthesizer using an amide resin (Intavis, Germany) as previously described (Hanke and Mann, 2009). Briefly, an amino acid sequence stretch of 13 residues surrounding the central in vivo tyrosine phosphorylation site that we have previously identified by mass spectrometry (Olsen et al., 2006) were synthesized with an N-terminal SerGly-linker and a N-amino modified desthiobiotin moiety for coupling to streptavidin-coated beads and efficient elution via biotin. The purity of the all synthetic peptides was confirmed by mass spectrometric analysis.

Peptide Pull-down

Peptide pull-downs were performed automatically on a TECAN pipetting robot using the peptide pull-down protocol previously described (Schulze et al., 2005). The synthetic peptides were bound to streptavidin-coated magnetic beads (Dynal MyOne, Invitrogen), and cell lysate corresponding to 1 mg of protein (~5 mg/ml protein) was added to 75 μl of beads containing an estimated amount of 2 nmol of synthetic peptide. Heavy SILAC-labeled lysate was incubated with the phosphorylated version of the peptide, whereas light SILAC-labeled lysate was added to the non-phosphorylated counterpart. After rotation at 4 °C for four hours, the beads were washed for at three times by with lysis buffer. Beads from each peptide pair were combined and bound proteins were eluted using 20 mM biotin. Eluted proteins were then precipitated by adding 5 volumes of ethanol together with sodium acetate and 20-μg glycoblue (Ambion).

In-solution Protein Digestion

The precipitated proteins were resuspended in 20 μl of 6 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0 and reduced by adding 1 μg of dithiothreitol for 30 min, followed by alkylation of cysteines by incubating with 5-μg iodoacetamide for 20 min. Digestion was started by adding endoproteinase Lys-C (Wako). After three hours samples were diluted with four volumes of 50 mM NH4HCO3, and trypsin (Promega) was added for overnight incubation. Proteases were applied in a ratio of 1:50 to protein material, and all steps were carried out at room temperature. Digestion was stopped by acidifying with trifluoroacetic acid, and the samples were loaded onto homemade StageTips packed with reversed-phase-C18 disks, (Empore, 3M, MN) for desalting, and concentration prior to LC-MS-analysis.

Nanoflow LC-MS/MS

Digested peptide mixtures were separated by online reversed phase nanoscale capillary liquid chromatography and analyzed by electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. Experiments were performed with an Easy-nLC nanoflow system (Proxeon Biosystems) connected to an LTQ-Orbitrap XL or 7T-LTQ-FT Ultra mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany) equipped with a nanoelectrospray ion source (Proxeon Biosystems, Odense, Denmark). Binding and chromatographic separation of the peptides took place in a 15 cm fused silica emitter (75-μm inner diameter) in-house packed with reversed-phase ReproSil-Pur C18-AQ 3-μm resin (Dr. Maisch GmbH, Ammerbuch-Entringen, Germany). The mass spectrometer was operated in the data-dependent mode to automatically switch between high-resolution orbitrap full scans (R=60K at m/z = 400) and LTQ ion trap CID of the top ten most abundant peptide ions. All full scans were automatically recalibrated in real time using the lock-mass option.

Peptide and protein identification and quantification

Peptide and proteins were identified by using Mascot and the MaxQuant software suite (Cox and Mann, 2008) and filtered for an estimated False discovery rate of less than one percent. All SILAC pairs were quantified by MaxQuant and the corresponding protein ratios were calculated from the median of all peptide ratios and normalized such that the median of all peptide ratios (log-transformed) were zero.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

We describe the recognition specificity of 70 SH2 domains.

Recognition specificity diverges faster than sequence.

PepSPOT: a database of protein interactions mediated by SH2 domains.

Acknowledgments

Tony Pawson has provided some SH2 expression plasmids. Claudia Dall’Armi has prepared some SH2 domains. This work was supported by the EU FP6 Interaction Proteome integrated project, the by FP7 Affinomics project and by the Italian foundation for Cancer Research (AIRC). MT was supported by a donation by Cesira Perazzi. Work at CPR is supported by a grant from the Novo Nordisk Foundation.

Abbreviations

- PTM

Post-translational modification

- GST

Gluthatione S-Transferase

- PCC

Pearson correlation coefficient

- ANN

artificial neural networks

- PSSM

position specific scoring matrices

- ROC

Receiver Operating Characteristic

- AROC

Area under the ROC

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Anderson D, Koch CA, Grey L, Ellis C, Moran MF, Pawson T. Binding of SH2 domains of phospholipase C gamma 1, GAP, and Src to activated growth factor receptors. Science. 1990;250:979–982. doi: 10.1126/science.2173144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blagoev B, Ong SE, Kratchmarova I, Mann M. Temporal analysis of phosphotyrosine-dependent signaling networks by quantitative proteomics. Nat Biotech. 2004;22:1139–1145. doi: 10.1038/nbt1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom N, Gammeltoft S, Brunak S. Sequence and structure-based prediction of eukaryotic protein phosphorylation sites. J Mol Biol. 1999;294:1351–1362. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt BW, Feenstra KA, Heringa J. Multi-Harmony: detecting functional specificity from sequence alignment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W35–40. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceol A, Chatr Aryamontri A, Licata L, Peluso D, Briganti L, Perfetto L, Castagnoli L, Cesareni G. MINT, the molecular interaction database: 2009 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D532–539. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatr-Aryamontri A, Ceol A, Licata L, Cesareni G. Protein interactions: integration leads to belief. Trends Biochem Sci. 2008;33:241–242. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatr-aryamontri A, Ceol A, Palazzi LM, Nardelli G, Schneider MV, Castagnoli L, Cesareni G. MINT: the Molecular INTeraction database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D572–574. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J, Mann M. MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:1367–1372. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diella F, Gould CM, Chica C, Via A, Gibson TJ. Phospho.ELM: a database of phosphorylation sites–update 2008. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D240–244. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosztanyi Z, Csizmok V, Tompa P, Simon I. IUPred: web server for the prediction of intrinsically unstructured regions of proteins based on estimated energy content. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3433–3434. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst A, Sazinsky SL, Hui S, Currell B, Dharsee M, Seshagiri S, Bader GD, Sidhu SS. Rapid evolution of functional complexity in a domain family. Sci Signal. 2009;2:ra50. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flicek P, Amode MR, Barrell D, Beal K, Brent S, Chen Y, Clapham P, Coates G, Fairley S, Fitzgerald S, et al. Ensembl 2012. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D222–9. [Google Scholar]

- Frank R. Spot-synthesis: an easy technique for the positionally addressable, parallel chemical synthesis on a membrane support. Tetrahedron. 1992;48:9217–9232. [Google Scholar]

- Gfeller D, Butty F, Wierzbicka M, Verschueren E, Vanhee P, Huang H, Ernst A, Dar N, Stagljar I, Serrano L, et al. The multiple-specificity landscape of modular peptide recognition domains. Mol Syst Biol. 2011;7:484. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong W, Zhou D, Ren Y, Wang Y, Zuo Z, Shen Y, Xiao F, Zhu Q, Hong A, Zhou X, et al. PepCyber:P~PEP: a database of human protein protein interactions mediated by phosphoprotein-binding domains. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D679–683. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanke S, Mann M. The phosphotyrosine interactome of the insulin receptor family and its substrates IRS-1 and IRS-2. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8:519–534. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800407-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermjakob H, Montecchi-Palazzi L, Bader G, Wojcik J, Salwinski L, Ceol A, Moore S, Orchard S, Sarkans U, von Mering C, et al. The HUPO PSI’s molecular interaction format–a community standard for the representation of protein interaction data. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:177–183. doi: 10.1038/nbt926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holgado-Madruga M, Emlet DR, Moscatello DK, Godwin AK, Wong AJ. A Grb2-associated docking protein in EGF- and insulin-receptor signalling. Nature. 1996;379:560–564. doi: 10.1038/379560a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornbeck PV, Chabra I, Kornhauser JM, Skrzypek E, Zhang B. PhosphoSite: A bioinformatics resource dedicated to physiological protein phosphorylation. Proteomics. 2004;4:1551–1561. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Li L, Wu C, Schibli D, Colwill K, Ma S, Li C, Roy P, Ho K, Songyang Z, et al. Defining the specificity space of the human SRC homology 2 domain. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7:768–784. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700312-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RB, Gordus A, Krall JA, MacBeath G. A quantitative protein interaction network for the ErbB receptors using protein microarrays. Nature. 2006;439:168–174. doi: 10.1038/nature04177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiemer L, Cesareni G. Comparative interactomics: comparing apples and pears? Trends in Biotechnology. 2007;25:448–454. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Godzik A. Cd-hit: a fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1658–1659. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licata L, Briganti L, Peluso D, Perfetto L, Iannuccelli M, Galeota E, Sacco F, Palma A, Nardozza AP, Santonico E, et al. MINT, the molecular interaction database: 2012 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D857–861. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linding R, Jensen LJ, Ostheimer GJ, van Vugt MA, Jorgensen C, Miron IM, Diella F, Colwill K, Taylor L, Elder K, et al. Systematic discovery of in vivo phosphorylation networks. Cell. 2007;129:1415–1426. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu BA, Jablonowski K, Raina M, Arce M, Pawson T, Nash PD. The human and mouse complement of SH2 domain proteins-establishing the boundaries of phosphotyrosine signaling. Mol Cell. 2006;22:851–868. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu BA, Jablonowski K, Shah EE, Engelmann BW, Jones RB, Nash PD. SH2 domains recognize contextual peptide sequence information to determine selectivity. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9:2391–2404. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.001586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machida K, Thompson CM, Dierck K, Jablonowski K, Karkkainen S, Liu B, Zhang H, Nash PD, Newman DK, Nollau P, et al. High-throughput phosphotyrosine profiling using SH2 domains. Mol Cell. 2007;26:899–915. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marengere LE, Songyang Z, Gish GD, Schaller MD, Parsons JT, Stern MJ, Cantley LC, Pawson T. SH2 domain specificity and activity modified by a single residue. Nature. 1994;369:502–505. doi: 10.1038/369502a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller ML, Jensen LJ, Diella F, Jorgensen C, Tinti M, Li L, Hsiung M, Parker SA, Bordeaux J, Sicheritz-Ponten T, et al. Linear motif atlas for phosphorylation-dependent signaling. Sci Signal. 2008;1:ra2. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.1159433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran MF, Koch CA, Anderson D, Ellis C, England L, Martin GS, Pawson T. Src homology region 2 domains direct protein-protein interactions in signal transduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:8622–8626. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen M, Lundegaard C, Worning P, Lauemoller SL, Lamberth K, Buus S, Brunak S, Lund O. Reliable prediction of T-cell epitopes using neural networks with novel sequence representations. Protein Sci. 2003;12:1007–1017. doi: 10.1110/ps.0239403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen JV, Blagoev B, Gnad F, Macek B, Kumar C, Mortensen P, Mann M. Global, in vivo, and site-specific phosphorylation dynamics in signaling networks. Cell. 2006;127:635–648. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panni S, Dente L, Cesareni G. In vitro evolution of recognition specificity mediated by SH3 domains reveals target recognition rules. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:21666–21674. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109788200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson T. Specificity in signal transduction: from phosphotyrosine-SH2 domain interactions to complex cellular systems. Cell. 2004;116:191–203. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persico M, Ceol A, Gavrila C, Hoffmann R, Florio A, Cesareni G. HomoMINT: an inferred human network based on orthology mapping of protein interactions discovered in model organisms. BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;6(Suppl 4):S21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-S4-S21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santonico E, Castagnoli L, Cesareni G. Methods to reveal domain networks. Drug Discov Today. 2005;10:1111–1117. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03513-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze WX, Deng L, Mann M. Phosphotyrosine interactome of the ErbB-receptor kinase family. Mol Syst Biol. 2005;1:2005 0008. doi: 10.1038/msb4100012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Songyang Z, Shoelson SE, Chaudhuri M, Gish G, Pawson T, Haser WG, King F, Roberts T, Ratnofsky S, Lechleider RJ, et al. SH2 domains recognize specific phosphopeptide sequences. Cell. 1993;72:767–778. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90404-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su AI, Wiltshire T, Batalov S, Lapp H, Ching KA, Block D, Zhang J, Soden R, Hayakawa M, Kreiman G, et al. A gene atlas of the mouse and human protein-encoding transcriptomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:6062–6067. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400782101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vastrik I, D’Eustachio P, Schmidt E, Joshi-Tope G, Gopinath G, Croft D, de Bono B, Gillespie M, Jassal B, Lewis S, et al. Reactome: a knowledge base of biologic pathways and processes. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R39. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-3-r39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenschuh H, Volkmer-Engert R, Schmidt M, Schulz M, Schneider-Mergener J, Reineke U. Coherent membrane supports for parallel microsynthesis and screening of bioactive peptides. Biopolymers. 2000;55:188–206. doi: 10.1002/1097-0282(2000)55:3<188::AID-BIP20>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisniewski JR, Zougman A, Nagaraj N, Mann M. Universal sample preparation method for proteome analysis. Nat Meth. 2009;6:359–362. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe MB. Phosphotyrosine-binding domains in signal transduction. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:177–186. doi: 10.1038/nrm759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.