Abstract

RNA transcripts are generally classified into polyA-plus and polyA-minus subgroups due to the presence or absence of a polyA tail at the 3′ end. Even though a number of physiologically and pathologically important polyA-minus RNAs have been recently identified, a systematic analysis of the expression and function of these transcripts in adipogenesis is still elusive. To study the potential function of the polyA-minus RNAs in adipogenesis, a dynamic expressional profiling was performed in the induced differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells. In addition to identifying thousands of novel intergenic transcripts, differentiation-synchronized expression was characterized for many of them. Among these, several large intergenic transcripts were found to be upregulated by more than 19-fold during differentiation. Further study demonstrated a fat tissue-specific expression pattern for these regions and identified an adipogenesis-associated long non-coding RNA. Collectively, these lines of evidence contribute to the characterization of a super-long intergenic transcript functioning in adipogenesis.

Keywords: large intergenic non-coding RNA, polyA-minus RNA, adipogenesis, obesity, high-throughput sequencing

Introduction

Obesity, the excess accumulation of adipose tissue in the body, is a major public health problem in developed and developing countries.1,4 To confront this challenge, a thorough understanding of the differentiation process as well as the regulation mechanisms is of critical importance.5-8 To characterize the essential factors in this process, extensive investigations have been performed in the past decades, using various in vitro and in vivo model systems. Among these, the mouse pre-adipocyte 3T3-L1 cell line, which was established in 1974, is the best characterized and most useful in vitro model.9 Using a standard hormone cocktail, this cell line is readily induced into adipogenesis and finally differentiates into mature adipocytes during a course of ~21 d. With the help of this and other model systems, a number of regulatory factors have been characterized in adipogenesis, such as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) and CCAT/enhancer-binding protein α (C/EBPα).5-8,10,11 This list is however far from complete because only limited numbers of downstream genes have been characterized as being regulated by these two so-called master regulators in adipogenesis.

Owing to the recent progress in nucleic acid-based high-throughput technology, this situation has been changing. In a number of genome-wide profiles of PPARγ binding sites and chromatin states in adipogenesis, tens of thousands of potential transcription sites have been identified.12-15 Further ChIP-seq studies indicated that over 70% of them are located in intronic as well as intergenic regions, strongly suggesting that these non-coding RNAs are integrated in the regulation pathway PPARγ.12,15

To further characterize the essential factors, in particular the large intergenic transcripts in adipogenesis, we performed a large-scale investigation of polyA-minus transcripts during the induced differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells, a well-established in vitro model system for adipogenesis, and the most characterized model system is the induced differentiation of pre-adipocyte 3T3-L1 cells. Upon defined hormonal induction, the cells are induced into adipogenesis and progress to a terminal stage where most cells are filled with lipid droplets and respond to physiological signals.

Results

Induced adipogenesis model system

To this end, MDI-induced differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells was performed and the expression of polyA-minus RNAs was profiled at three critical time points during the process, so as to reveal its dynamic properties. The first RNA sample was taken one day before the induction and the other two samples were subsequently taken at day 14 and day 21 after the treatment, representing pre-adipocytes, differentiating adipocytes and mature adipocytes respectively.

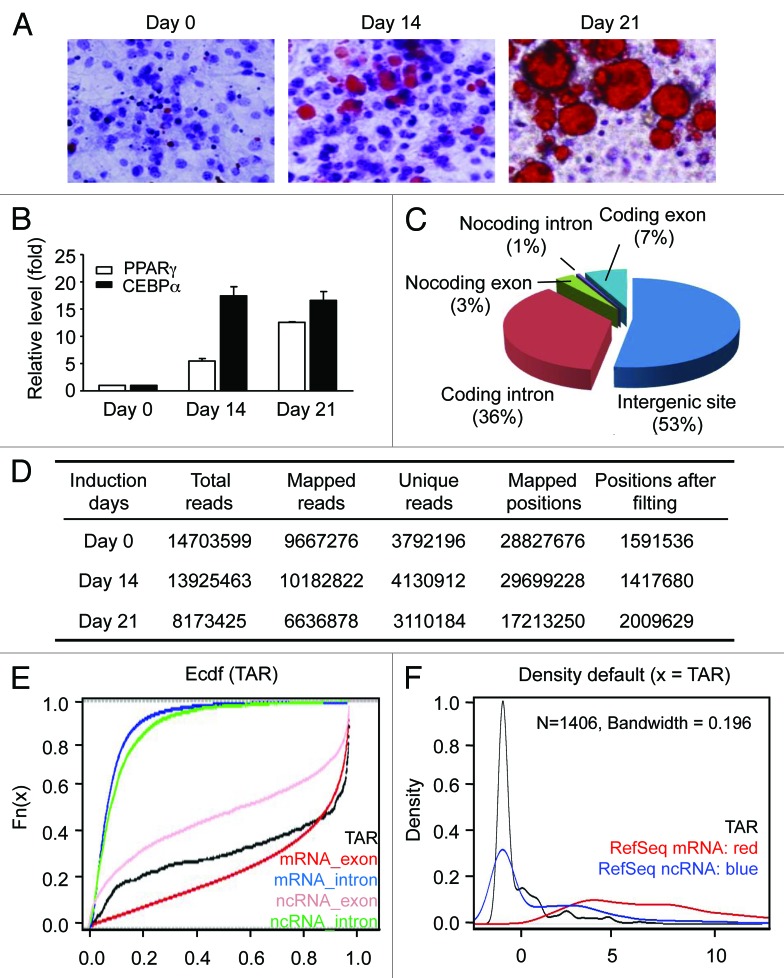

To monitor the progress of differentiation, the production and accumulation of lipid were examined by Oil Red O staining (Fig. 1A), and the expressional levels of PPARγ and CEBPα were measured by quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 1B). At day 21, more than 54% of cells are found with lipid accumulation (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1D), and led to elevated expression of PPARγ and CEBPα. Consistent with previous reports,16-20 a synchronous differentiation process was demonstrated in the study, showing that the model system fulfills the functional criteria of adipocyte differentiation.

Figure 1. In vitro adipogenesis and RNA sequencing. (A) Oil Red O staining of 3T3-L1 cells during adipogenesis. After the induction of differentiation (day 0), cultured cells are sampled at the indicated time points and stained with Oil Red O. For each time point, the numbers of the lipid-accumulated and lipid-unaccumulated cells were determined by visual check. The ratios of lipid-accumulated cells vs. lipid-unaccumulated cells are 0, 0.32 and 1.22 for day 0, day 14 and day 21. (B) Expression levels of PPARγ and CEBPα measured by RT-qPCR. Expression is plotted as fold-change relative to day 0 (mean ± sd). (C) Reads-mapping in different RNA categories. (D) RNA-seq data location and classification on mice genome (MM9). (E) Conservation analysis. Mean phastCons score, an empirically cumulative distribution of mean phastCons value, is used to evaluate the conservation of TARs. RefSeq mRNA exon, red; RefSeq mRNA intron, blue; RefSeq non-coding RNA intron, pink and RefSeq non-coding RNA intron, green. X axis indicates phastCons score and Y axis indicates the cumulative frequency. (F) Coding potential analysis. CPC (coding potential calculator) are used to evaluate the coding potential of TARs. The density plot of the CPC coding potential score is showed in red for RefSeq mRNA, in blue for RefSeq ncRNA and in black for novel intergenic TARs. X axis indicates CPC coding potential score and Y axis indicates the density.

Enrichment of polyA-minus transcripts and RNA-seq

To systematically discover essential polyA-minus RNAs in 3T3-L1 differentiation, a negative selection protocol was used to first isolate them from total RNA samples (Fig. S1A).21 With this, the abundant 18s and 28s rRNAs were depleted by sequence-specific and biotinylated DNA oligonucleotides, followed by removal of polyA-plus as well as small RNA transcripts using oligo(dT) probe and size fractionation. For proof of the depletion, the remaining amounts of rRNAs and mRNAs were visually checked (Fig. S1B) and then quantified by RT-qPCR (Fig. S1C). While no discernible rRNA bands were seen in the gels, quantitative measurements indicated that less than 2%, 7% and 13% of the original β-actin, 18s and 28s rRNA, respectively, remained in the processed samples, demonstrating efficient RNA depletion (Fig. S1).

Using this approach, polyA-minus RNA fractions were isolated from total RNA samples obtained from 3T3-L1 cells at three differentiation stages (days 0, 14 and 21 after induction). From those, RNA-seq libraries were generated by RNA fragmentation, random hexamer-primed cDNA synthesis, linker ligation and PCR amplification. Using an Illumina genome analyzer platform, each library was sequenced in an independent lane.

Reads mapping and bioinformatics analyses

In total, 36.8 million reads of 40 nt were obtained, comprising 14.7 million from pre-adipocytes, 13.9 million from differentiated adipocytes and 8.2 million from mature adipocytes (Fig. 1D). Seventy-six percent of the reads (28 million) were mapped to the reference mouse genome (NCBI37/mm9), using TopHat.22 These reads were then filtered against rRNAs and other repeated sequences, and finally resulted in a high-confidence set comprising 5.02 million uniquely mapped reads. Seven percent of the high-confidence reads was mapped to the exons of Refseq genes, while the others mapped to non-coding genome regions. Reads mapped to the non-coding regions were further classified into subgroups located in the introns of Refseq genes (36%), known non-coding genes (4%) and intergenic regions (53%) (Fig. 1C).

To further evaluate the experiment procedure and the data analysis, reads-mapping to several known polyA-minus transcripts were examined. Hist2h4 encodes a 348-bp histone transcript lacking a polyA tail, while MALAT-1 encodes a tumor-associated long intergenic non-coding RNA of 6.9 kb. Reads-mapping revealed a concentrated distribution on these two transcription regions, but not on the flanking areas (Fig. S2). These results therefore confirmed the enrichment process on the one hand, and on the other hand, indicated that the reads originated from authentic RNA transcripts. Distinct from the regulated nature of many polyA-minus transcripts, relatively consistent expressional levels were found for histone transcripts across the course of differentiation, reflecting their essential roles in the cells.

The reads mapped to intergenic regions were of particular interest, because they might represent novel transcription regions in adipogenesis. As the first step to characterize these regions, their evolutionary conservation and coding potential were analyzed. Similar to the previously identified large intergenic non-coding RNAs,23-24 intermediate conservation levels and low coding potential relative to the other transcript categories were found for these regions (Fig. 1E and F).25-31

Regulated expression profiles

To accurately define the boundaries of these intergenic transcription regions, reads-assembly was performed using two parameters: the maximum spacing between two neighboring reads, and the minimum number of mapped reads within a genomic region. Taking the stringent criteria of maximum spacing of 150 nucleotides and 10 mapped reads, a set of 1,406 independent transcriptionally active regions (TARs) was confidently identified (Table S1).

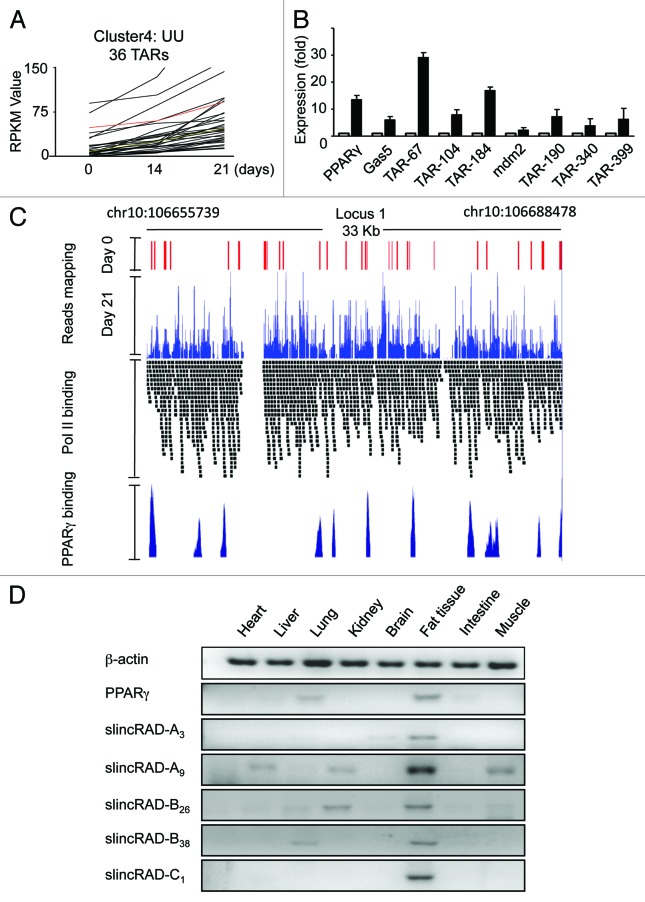

A remarkable property of RNA-seq is that it allows for precise quantification of transcriptional activity on a genome-wide scale. To this end, the expressional levels of the TARs were calculated in terms of RPKM (reads per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads). When the expression levels were profiled relative to the differentiation stages, a dynamic pattern was revealed. Compared with their levels in pre-adipocytes, 179 TARs were upregulated and 61 were downregulated in differentiating adipocytes. After the cells progressed further to mature adipocytes, 698 TARs were upregulated and 106 were downregulated relative to their expression levels in differentiating adipocytes. The distinct expression patterns categorized these TARs into several subgroups, suggesting their diverse functions in adipogenesis (Fig. S3). Considering their induction property during the process, the upregulated subgroup was selected to be further studied (Fig. 2A). The relevance of a number of randomly selected TARs to adipogenesis was further demonstrated by the consistent expression profiles resulting from RT-qPCR (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. Regulated expression of TARs. (A) Expressional profiles of a subgroup of TARs. X axis, the three time points of RNA-seq samples; Y axis, the RPKM value of the TARs. In this subgroup, 36 TARs are continuously upregulated from day 0 to day 14, and to day 21. UU indicates the expression level of the TARs is upregulated from one time point to the next. (B) Expression levels measured by qRT-PCR. The expression levels of several TARs ranging from 500–1,200 bp are quantified at days 0 and 21. Open bars, expression levels on day 0; filled bars, expression levels on day 21. For each TAR, the data are first normalized to an internal control, and then to its respective level on day 0. The expression level of PPARγ is included as a differentiation control, and another annotated non-coding RNA, GAS5, is included as a processing control. (C) Distribution of RNA-seq reads. The sites for PPARγ binding and Pol II occupancy in an identified large intergenic transcription region are presented. RNA-seq data and reference data15,25 are viewed in UCSC genome browser for the RNA-seq reads locus on day 0 (red peak) and day 21 (blue peak) locus on PolII tracks (black band) and PPARγ tracks (dark blue peak). (D) Tissue-specific expression profile. Expression levels of a few TARs are determined by RT-PCR in mouse heart, liver, lung, kidney, brain, fat, skeletal muscle and intestine. slincRAD-A is represented by TAR-slincRAD-A3 (TAR-61) and TAR-slincRAD-A9 (TAR-67), slincRAD-B is represented by TAR-slincRAD-B26 (TAR-104) and TAR-slincRAD-B38 (TAR-116) and slincRAD-C is represented by TAR-slincRAD-C1 (TAR-157). β-actin and PPARγ are included as RNA quality and differentiation controls.

Fat tissue-specifically intergenic transcription regions in mature adipocytes

Further investigation was then focused on the previously uncharacterized TARs. Chromosome-wide distribution showed that in mature adipocytes, 10% of the TARs (146 TARs) were mapped to chromosome 10. And to our surprise, 94% of them clustered in three large intergenic transcription locus, spanning a genomic region of 10.3 Mb in total (Figs. 2C and 3B; Figs. S6 and S7). The first locus spans a genomic region of 33 kb (chr10:106655739-106688478) and is composed of 11 TARs; the second locus spans a region of 91.2 kb (chr10:116823862-116915327) and is composed of 42 TARs; and the third locus spans a region of 13.6 kb (chr10:117,026,569-117038309) and is composed of three TARs. During the course of differentiation, the expression levels of these loci were upregulated more than 19-fold in terms of RPKM, suggesting critical roles in adipogenesis as well as in mature adipocytes.

Figure 3. Characterization of super-large intergenic RNA transcription. (A) Developmentally orchestrated expression of three long intergenic transcription regions. Expression levels of the representative TARs in three large intergenic transcription loci (slincRAD-A, slincRAD-B and slincRAD-C) are examined in the presence or absence of MDI induction. Treated and untreated cells are harvested at the time points indicated, and their RNA levels are measured by qRT-PCR. The data are normalized to the expression level at day 0 and presented as mean ± sd. PPARγ is included as differentiation control. Error bars are plotted for all samples at all the time points; however, some of them are too small to be seen. (B) Co-repression assay leads to the identification of the full-length slincRAD gene. siRNAs targeting different genomic loci are individually transfected into cultured 3T3-L1 cells one day before MDI induction. Two days after the second transfection, cells are harvested and the expression levels of the TARs are determined using RT-qPCR. Left panel, positions of the siRNAs; right panel, expression levels of the TARs normalized to Lamin A/C control and presented as mean ± SD; low panel, genomic configuration of slincRAD. (C) Using RT-PCR, the presence of slincRAD transcripts is examined in polyadenylated and non-polyadenylated RNA fractions. β-actin and PPARγ are presented as polyadenylated RNA controls. slincRAD-A is represented by TAR-slincRAD-A3 (TAR-61), slincRAD-B is represented by TAR-slincRAD-B38 (TAR-116). (D) Transcription orientation of slincRAD determined by strand-specific RT-PCR. (E) Nuclear distribution of slincRAD RNAs. RT-PCR was performed with nuclear and cytoplasmic RNA fraction respectively. As a snRNA control, U6 expressed in nuclear RNA fraction specifically, and β-actin and MALAT1 mainly distributed in both cytoplasm and nucleus. slincRAD-A is represented by TAR-slincRAD-A3 (TAR-61), slincRAD-B is represented by TAR-slincRAD-B38 (TAR-116), and slincRAD-C is represented by TAR-slincRAD-C1 (TAR-157). (F) Silencing activity of siRNAs targeting potential transcripts derived from the plus and minus genome region of slincRAD. The data are normalized to a sequence irrelevant siRNA (NC-siRNA).

Upregulation of the TARs in adipogenesis in vitro led us to speculate that they might also be implicated in the development of fat tissue in vivo. Therefore, the expression levels of a few selected TARs were measured in diverse mouse tissues (Fig. 2D; Fig. S4), using RT-qPCR. Three male BALB/c mice of eight to 10 wk and weighed 18–22 g at the time of the study were used. RNA samples were extracted from the pooled tissues obtained from the mice and used in the assay. As expected, a fat tissue-specific expression profile was shown for the tested TARs (Fig. 2D). Interestingly, this unique pattern was also shared by PPARγ, which leads further support to their roles in fat tissue development.

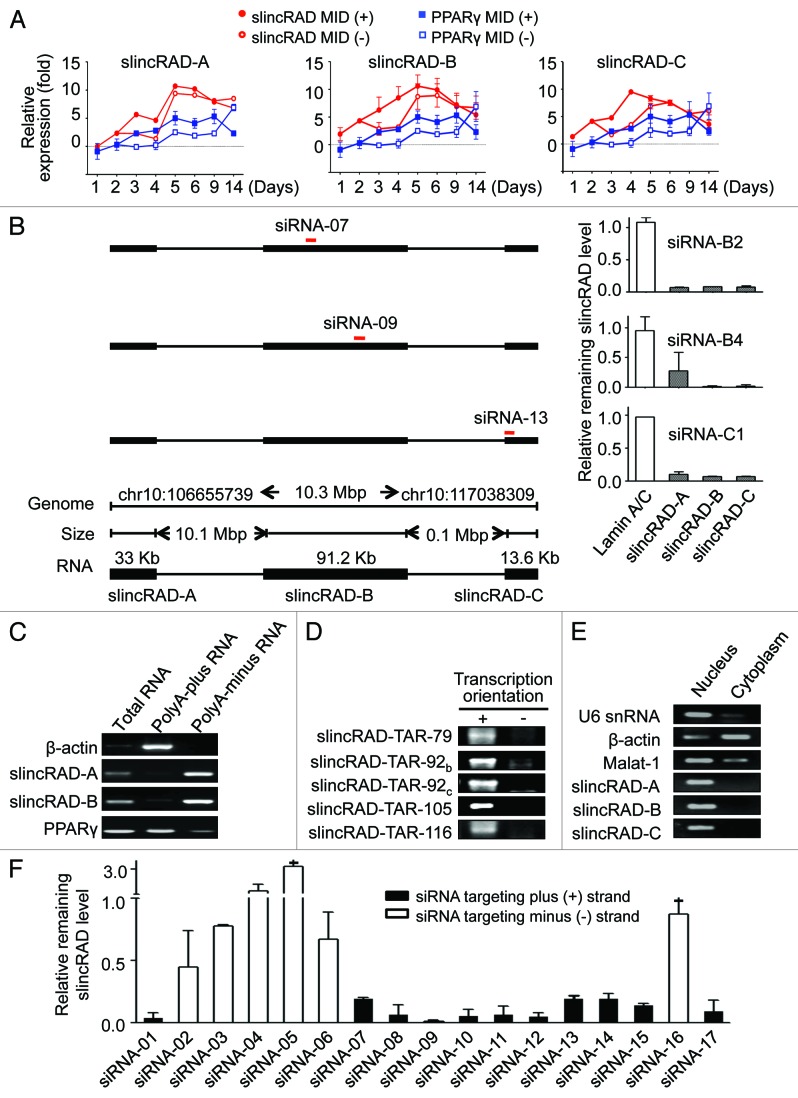

To closely monitor the expression regulation of these regions during early differentiation, a few representative TARs were selected and their expression levels were measured at eight time points, starting from day 0. Using quantitative RT-PCR, their expression levels were measured in both MDI-treated and -untreated cells, and the changes in expression were calculated relative to day 0 (Fig. 3A). Consistent with our and others’ studies,32 the levels of PPARγ increased steadily at the initiation stage and displayed a dynamic regulation. As expected, this regulation profile was shared by the tested TARs. This confirmed our earlier observations and further suggested a co-regulation of these transcripts.

Co-regulation of these transcripts as well as their genomic proximity led us to speculate that they may derive from a single transcript. To test this hypothesis, a number of siRNAs were designed to target different TARs of the three large intergenic transcription loci. When a siRNA targeting a specific TAR within a transcription locus was used, expression levels of TARs in the other transcription loci were also examined, together with the desired target. Interestingly, parallel repression of all three transcription loci were observed for 11 active siRNAs, indicating that these TARs are derived from a single super-long intergenic RNA transcript with a calculated size of 136 kb, which plays a critical role in adipogenesis (Fig. 3B; Fig. S5). This gene was therefore named “slincRAD” to indicate that it is a super-long intergenic non-coding RNA functioning in adipocyte differentiation.

To further verify that slincRAD transcripts are indeed non-polyadenylated, oligo-dT pull-down assays were performed to separate the polyadenylated and non-polyadenylated RNA fractions from 3T3-L1 total RNA. The presence of slincRAD in these two fractions was examined using RT-PCR, showing that slincRAD transcripts are distributed mostly in the non-polyadenylated RNA fraction (Fig. 3C).

Transcription orientation and subcellular localization of slincRAD

To determine the transcription orientation of slincRAD, a number of PCR primer sets were designed across the whole length of the transcript. Transcription from the genome plus-strand was detected by reverse transcription using downstream primer, followed by PCR amplification using both upstream and downstream primers. In the same way, transcription from the genome minus-strand was detected by reverse transcription using upstream primer. As shown in Figure 3D, transcription from the plus-strand was detected by all the PCR sets, while only one assay detected a weak transcription from the minus-strand. In addition to the strand-specific RT-PCR assays, strand-specific siRNAs were also designed to target the plus- or the minus-strand. Cell assays showed that siRNAs targeting the plus-strand transcription, but not the minus-strand transcription effectively repressed the expression of slincRAD (Fig. 3F). These data therefore led to the conclusion that slincRAD RNA is transcribed from the plus strand of chromosome 10 in mouse.

In contrast to mRNAs and small non-coding RNAs that function mainly in the cytoplasm, super-long RNAs such as Air or Xist function mainly within the nucleus, exerting their physiological activities by chromatin modification and transcriptional regulation. To characterize the cellular distribution of slincRAD RNA, the nuclear and cytoplasmic RNA fractions were individually isolated, using an RNA purification kit from Ambion. By means of previously established RT-PCR assays, the abundance of slincRAD was measured in RNA samples from nucleus and cytoplasm, showing that slincRAD RNAs are distributed mainly in the nucleus (Fig. 3E).

Functions of slincRAD in adipogenesis and potential roles in human pathogenesis

To address whether PPARγ also functions to regulate the expression of slincRAD, the genomic locations of PPARγ-binding sites were extracted from public data sets12-15 and mapped relative to slincRAD. The results showed that ~20% of the TARs lay in close proximity to the binding sites of PPARγ within a flanking range of 5 kb (Fig. 2C; Figs. S6 and S7). Furthermore, a total of 7,218 PPARγ binding sites were captured on day 6 after MDI treatment in one of the study,15 which translates into an average of 0.027 binding sites per 10 kb genome sequence. However, more than 40 PPAR binding sites are found to locate in slincRAD transcript region of 138 kb, on average 2.89 binding sites per 10 kb sequence. These data together suggest that the expression of slincRAD is likely under the regulation of PPARγ, the master regulator of adipogenesis.

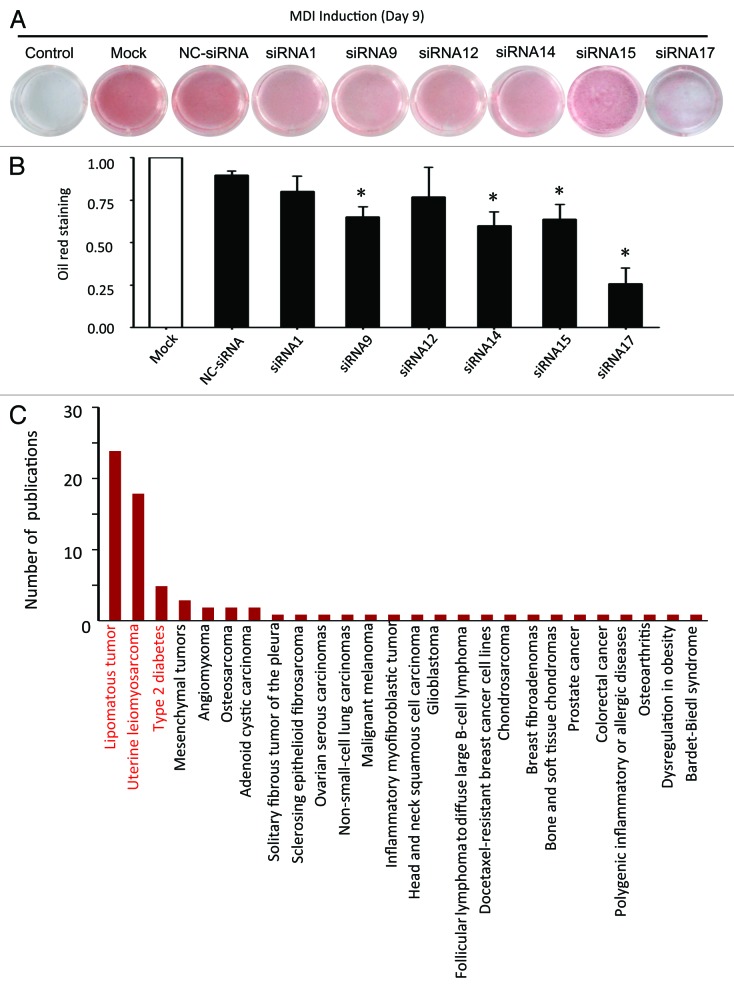

These lines of evidence led to a speculation that slincRAD might be involved in the induced differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells. To this end, its influence on adipogenesis was evaluated by gene-silencing assay, using slincRAD-specific siRNAs. Six effective siRNAs were used to silence slincRAD expression in cultured 3T3-L1 cells, and their effects on lipid accumulation were visualized by Oil Red O staining. In brief, 3T3-L1 cells were grown in DMEM culture medium and subjected to twice siRNA transfection, before and after MDI treatment. Nine days later, the cells were harvested and subjected to Oil Red O staining to visualize cellular accumulation of lipid (Fig. 4A), a well-documented adipogenesis index. Quantitative analysis indicated that in comparison to the untreated control and scramble siRNA-treated cells, some siRNAs potently decreased the amount of lipid accumulation in differentiated adipocytes (Fig. 4B), while the proliferation of the cells was not affected (Fig. S8). In particular, siRNA-17 treatment caused a 70% reduction in lipid accumulation.

Figure 4. Function analyses of slincRAD. (A) Oil Red O staining of siRNA-treated and untreated cells. In brief, 3T3-L1 cells were grown in DMEM culture medium and subjected to the first siRNA transfection two days before MDI treatment (day 1). At the same day of MDI treatment, a second transfection of the same siRNA was performed. At day 9, the cells were harvested and subjected to Oil Red O staining, to visualize the lipid accumulation within the cells. Control, cells without MDI induction and siRNA treatment; Mock, cells with only MDI induction; NC-siRNA, cells with MDI induction and a sequence irrelevant siRNA treatment; siRNA1-siRNA17, cells treated with MDI induction and slincRAD-specific siRNA treatment. (B) Quantification of Oil Red O staining. The images of Oil Red O staining cells are taken and the staining intensities are quantified by means of examining their gray scale, using ImageJ (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/). To remove the background staining, the staining intensity of untreated cells is first subtracted from that of MDI-treated cells. The intensities of siRNA-treated cells are then normalized to the intensities of the mock treatment, and further normalized to the number of the cells to show the effect of siRNA treatment on cell differentiation. The statistics are calculated with t-tests (*, p < 0.05 relative to NC-siRNA control). (C) A literature search on the homologous human genomic region of slincRAD is performed and results in 81 hit publications. These publications are presented in term of the underlying human disorders. X axis, human disorders; Y axis, the number of the publications.

In addition to lipid accumulation, the differentiation process was further confirmed by the changes of a master adipogenesis marker, PPARγ. In which, a randomly picked siRNA targeting slincRAD, as well as a scramble siRNA, were transfection into cultured cells and their effects on PPARγ levels during the differentiation were examined by RT-qPCR (Fig. S9). The results showed that, in addition to delay the differentiation progress as indicated by lipid accumulation (Fig. 4A and B), siRNA-14 treatment led to reduced levels for both PPARγ and slincRAD, in comparison to the scramble siRNA treatment. Taken together, these results demonstrate that slincRAD is a contributing factor in adipogenesis.

To further pursue its implications in human pathogenesis, a comparative genomics approach was used. Even though lncRNA genes evolve fast in sequence level, their genome loci are mostly conserved.33 Therefore, the homologous human genomic region of mouse slincRAD was determined, and its potential involvement in human pathogenesis was characterized by literature search. To do this, we first identified the flanking protein-coding genes of slincRAD in mouse genome: the upstream protein-coding gene is Cpsf6 and the downstream gene is Cpm. Then, their homologous human counterparts were determined to be located at q15 in chromosome 12 of human genome. Using these flanking genes as landmarks, homologous genomic region of slincRAD was identified in human (Fig. S10). To further characterize potential involvement of the human homologous region in pathogenesis, a literature search was performed in NCBI database. In total, 81 publications investigating this region were retrieved. As shown in Figure 4C, the identified human homologous region is extensively implicated in human pathogenesis and associated with the development or malfunction of fat tissue, such as lipomatous tumor, uterine leiomyo-osteosarcoma and type II diabetes (Fig. 4C), therefore disclosing a relationship between slincRAD and human pathogenesis.

Discussion

The genome is expressed through transcription, generating different classes of RNA species. A major goal of transcriptome studies is to identify all the transcripts at the sequence level and characterize their physiological and pathological activities; this has been very successful for the polyA-plus fraction due to the presence of 3′ polyA tails. However, only limited knowledge has been accumulated for the polyA-minus RNA fraction, even though their prevalence in eukaryotic cells has been demonstrated by increasing evidence. This situation is largely attributed to the technical difficulty involved in the isolation and characterization of polyA-minus transcripts. Unlike polyA-plus RNAs, there is no known consensus sequence or common structure for polyA-minus RNAs. To overcome this obstacle, a negative selection strategy was recently developed to enrich polyA-minus transcripts by systematically depleting the abundant rRNAs and mRNAs. Taking advantage of this method, the expression and regulation of polyA-minus transcripts in adipocyte differentiation were systematically investigated in the present study, using a RNA-seq platform. By coupling the ribo-depletion procedure with massive-scale RNA sequencing technology, our approach offers the possibility of detecting previously uncharacterized actively transcribed genomic regions.

Focusing on the polyA-minus transcriptome in adipogenesis, we generated RNA-seq libraries from cultured 3T3-L1 cells at different stages of differentiation, namely pre-adipocytes, differentiated adipocytes and mature adipocytes. Sequencing these libraries using an Illumina genome analyzer platform led to the identification of 11.03 million uniquely mapped reads in total, enabling us to systematically identify and characterize polyA-minus transcripts during the process. These reads were then mapped to the mouse genome and filtered against rRNAs and other repeated sequences, finally resulting in a high-confidence data set comprising 5.02 million uniquely mapped reads. As expected, ~93% of the reads were mapped to non-coding genome regions, such as the introns of Refseq genes, known non-coding genes and intergenic regions. Reads mapped to the intergenic regions were of particular interest to us, because they might represent novel transcription positions in adipogenesis. Using a stringent criterion for independent transcriptional regions, a set of 1,406 novel intergenic transcriptionally active regions were identified. In mature adipocytes, 10% of the TARs were unexpectedly mapped to chromosome 10. And more surprisingly, 94% of these reads clustered in three large intergenic transcription regions, covering a genomic span of 10.3 Mb.

In addition to identifying thousands of intergenic transcription regions, this comprehensive data enabled us to further capture the dynamic changes of polyA-minus transcripts as development proceeded. This property might also apply to other differentiation and developmental processes. This is an intriguing finding in light of the fact that numerous lncRNAs have been shown to interact with repressive chromatin-modifying complexes. The polyA-minus RNAs expressed at the early stage of differentiation might also have important roles in cell fate decisions, differentiation and organogenesis.

In summary, we generated RNA-seq libraries from cultured 3T3-L1 cells at different differentiation stages, focusing on the polyA-minus RNAs. By using an Illumina genome analyzer platform, sequencing these libraries identified a set of 1,406 novel intergenic TARs. In mature adipocytes, 10% of the TARs were surprisingly mapped to chromosome 10 in the mouse genome. And more interestingly, 90% of the TARs that mapped to chromosome 10 clustered in three large intergenic transcription loci, spanning 10.3 Mb. Further studies of these TARs led to the identification of a super-long intergenic transcript named slincRAD, which was shown to be involved in adipogenesis and fat tissue-related pathogenesis. In addition, our study provided a comprehensive annotation of polyA-minus RNA transcripts during adipogenesis. Their dynamic changes suggest that they are implicated in either the differentiation regulation or functionality of fat tissue, revealing novel insights into the mechanisms of in vitro and in vivo adipogenesis. Furthermore, our study provides a generally applicable strategy to characterize novel noncoding RNAs in various biological processes.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

Animals were maintained in the Center for Experimental Animals (an AAALAC accredited experimental animal facility) at Peking University. All procedures involving animals were performed in accordance with protocols approved by the Committee for Animal Research of Peking University, and conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH publication No. 86-23, revised 1985).

Oligonucleotides

DNA oligonucleotides were from Invitrogen. RNA oligonucleotides were from RiboBio.

Cell culture and MDI treatment

3T3-L1 pre-adipocytes were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% bovine serum. Adipogenesis was induced as previously described. In brief, 2 d after the cells reached confluence (day 1), they were induced to differentiate by changing the culture medium to DMEM supplemented with 0.5 mM 3-isobutyl-1-methyxanthine (Sigma), 1 μM dexamethasone (Sigma) and 167 nM insulin (Sigma). At the end of day 2, culture medium was replaced with DMEM supplemented only with 167 nM insulin; at the end of day 4, insulin was withdrawn and the cells were allowed to grow in DMEM throughout the rest of the experiment. At each time point, the cells were collected by washing three times with ice-cold PBS and then stored at -80°C until further processing.

Oil Red O staining

Oil Red O staining was performed to monitor the progression of adipocyte differentiation as described.26 Briefly, cells on days 0, 14 and 21 were washed three times with ice-cold PBS and fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde for 2 min, then incubated with Oil Red O reagent for 1 h at room temperature and washed with water. Oil red O reagent (0.5%) was prepared in isopropanol by mixing with water at a 3:2 ratio and filtering through a 0.45-μm filter. The stained fat droplets in the cells were visualized by light microscopy and photographed. To quantitatively analyze the Oil Red O staining, images are taken and the intensities are quantified by means of examining their gray scale, using ImageJ (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/). To remove the background staining, the staining intensity of untreated cells is first subtracted from that of MDI-treated cells. The intensities of siRNA-treated cells are then normalized to the intensities of the mock treatment, and further normalized to the number of the cells to show the effect of siRNA treatment on cell differentiation.

PolyA-minus RNA preparation and RNA sequencing

Total RNAs were isolated from cultured cells using an RNApureTM kit (Biomed). Eight micrograms of purified RNAs was subjected to sequential depletion of rRNA, mRNA and short RNA species with an rRNA depletion kit (Jianchengda Inc.), resulting in a pool of polyA-minus RNAs. The cDNA libraries were prepared starting from 2 µg of polyA-minus RNAs using random hexamer priming (Invitrogen). It must be noted that the reverse-transcribed double-stranded cDNA fragments do not preserve information about the strand specificity of the original transcript. The Illumina sequencing libraries were prepared according to the single-end sample preparation protocol. The libraries were sequenced using the 1G Illumina genome analyzer.

Bioinformatics analysis

The obtained reads were first mapped on the mouse reference genome (mm9) using the TopHat program (v1.2.0). Reads mapped to house-keeping genes were then filtered against the RepeatMask and Ensembl gene sets, which resulted in the identification of novel intergenic transcription regions. For each transcription region, an RPKM value was calculated to quantify its expressional abundance and variations, using cufflinks v1.0.3.

To evaluate the evolutionary conservation of TARs, the phastcons scoring method developed by UCSC was used. Phastcons is based on the whole genome alignment of 30 vertebrates and gives every nucleotide a score to reflect its probability of belonging to a conserved element. To evaluate the coding potential of each transcription region, a CPC (coding potential calculator) assay was performed.

qRT-PCR assay

cDNA was synthesized with SuperScript II (Invitrogen) and qPCR was performed using SYBR Green PCR mix. Relative expression values were calculated (ΔΔCT method) using GAPDH or β-actin as an internal control.

RNAi assay

To knock down slincRAD, siRNAs were individually transfected in the following steps: Cells were seeded at a density of 10,000 cells/well in 1 ml of growth medium one day before transfection. Individual siRNA targeting slincRAD or scrambled control siRNA was transfected, using lipofectamine2000 (Invitrogen). Lipofectamine/siRNA complexes were formed in 0.2 ml of serum-free Opti-MEM reduced serum medium (GIBCO) for 10 min at room temperature and then added to each well. Cells were cultured for two more days until they reached confluence and subjected to MDI treatment (day 1). At the same day, a second transfection was performed.

Author please add in-text citation for Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1. RT-PCR primer sets.

| β-actin | Forward primer: 5′-GAAGAGCTATGAGCTGCCTGA |

| Reverse primer: 5′-CTCATCGTACTCCTGCTTGCT | |

| PPARγ | Forward primer: 5′-AAGAGCTGACCCAATGGTTG |

| Reverse primer: 5′-ACCCTTGCATCCTTCACAAG | |

| CEBPα | Forward primer: 5′-GCTTTTTGCACCTCCACCTA |

| Reverse primer: 5′-CTCTGGGATGGATCGATTGT | |

| 18s rRNA | Forward primer: 5′-CGGCTACCACATCCAAGGAA |

| Reverse primer: 5′-GCTGGAATTACCGCGGCT | |

| 28s rRNA | Forward primer: 5′-TCATCAGACCCCAGAAAAGG |

| Reverse primer: 5′-GATTCGGCAGGTGAGTTGTT | |

| MALAT-1 | Forward primer: 5′-CACTTGTGGGGAGACCTTGT |

| Reverse primer: 5′-TGTGGCAAGAATCAAGCAAG | |

| GAS5 | Forward primer: 5′-GTTGAAAGGACAGTGCCACA |

| Reverse primer: 5′-TTCAGACTTCCCACCCACTC | |

| TAR-61 | Forward primer: 5′-TCTGAATTGCCCATCTCTCC |

| Reverse primer: 5′-CGTGCCTATGTTCCAATATCC | |

| TAR-67 | Forward primer: 5′-CAACACGTCTCAGTCTTTTTGC |

| Reverse primer: 5′-ATGGACAGCCTCAGCCTAAA | |

| TAR-79 | Forward primer: 5′- AGAGCAGCTCAGTTTCAAACAA |

| Reverse primer: 5′- TGAAATGATGGCTGGTGAAA | |

| TAR-92a | Forward primer: 5′-CATGGCCTTGACAAGTTTGA |

| Reverse primer: 5′- ATTGCAGTAGCCCGTAATGG | |

| TAR-92b | Forward primer: 5′-CGATGTCCCAAAGGAAACAC |

| Reverse primer: 5′- ACTTCCGTATCGGGGAGACT | |

| TAR-104 | Forward primer: 5′-ACAAGAAGAAGAGGCGGTCA |

| Reverse primer: 5′-GAGGCCAGCAAGATCAGAAC | |

| TAR-105 | Forward primer: 5′-CTCAAATAATGGCGGTGCTT |

| Reverse primer: 5′- TTGGTATGCGTGCTCTTCAG | |

| TAR-115 | Forward primer: 5′-GCCTCTGGGGGAATACAAAT |

| Reverse primer: 5′- CCCACCAGGGTTCTCAGTAA | |

| TAR-116 | Forward primer: 5′- GCCACAGCACTAGGGAAGAC |

| Reverse primer: 5′- ACAGTCATGCGTGAAAGCAG | |

| TAR-157 | Forward primer: 5′- TACCATGTCGGTCCCATTTT |

| Reverse primer: 5′- TGTGCCAAGTCTTCAGGTTG | |

| TAR-184 | Forward primer: 5′-TGAGTTCCCAAAGGACAAGG |

| Reverse primer: 5′-CGGCTAATGCTTTCTTCCTG | |

| mdm2: | Forward primer: 5′-CCACCACACAACCTAGCTGA |

| Reverse primer: 5′-GCCTTTGCATGTATTTTAAGTGA | |

| TAR-190 | Forward primer: 5′-CCTGCCCTTCACAAAGAAAA |

| Reverse primer, 5′-GAACTTTGAAGGCCGAAGTG | |

| TAR-340 | Forward primer, 5′-AAACTGTTTGATCCCGCAAA |

| Reverse primer, 5′-TGCCTTTAGATATGGCACTAGGA | |

| TAR-399 | Forward primer, 5′-ATGGCCCAAATTGTTTGCTA |

| Reverse primer, 5′-GCACAAAAATGATCCCTCAGA |

Table 2. siRNA sets.

| Orientation named | Full-length named | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| siRNA-01 | slincRAD-B1-siRNA | sense strand: 5′-CAACUAGGCUUCACAAAUAtt-3′ |

| antisense strand: 5′-UAUUUGUGAAGCCUAGUUGtt-3′ | ||

| siRNA-02 | slincRAD-B2-siRNA | sense strand: 5′-GGGAAUUACUCAGGAAGAUtt-3′ |

| antisense strand: 5′-AUCUUCCUGAGUAAUUCCCtt-3′ | ||

| siRNA-03 | slincRAD-B3-siRNA | sense strand: 5′-CCUGAGUAAUUCCCUUUAUtt-3′ |

| antisense strand: 5′-AUAAAGGGAAUUACUCAGGtt-3′ | ||

| siRNA-04 | slincRAD-B4-siRNA | sense strand: 5′-CCACGGGAAAUAACUCUUUtt-3′ |

| antisense strand: 5′-AAAGAGUUAUUUCCCGUGGtt-3′ | ||

| siRNA-05 | slincRAD-B5-siRNA | sense strand: 5′-CCGUGUUCCAUACAGUUAAtt-3′ |

| antisense strand: 5′-UUAACUGUAUGGAACACGGtt-3′ | ||

| siRNA-06 | slincRAD-B6-siRNA | sense strand: 5′-GGAAGAUUCCCUCUGCGUUtt-3′ |

| antisense strand: 5′-AACGCAGAGGGAAUCUUCCtt-3′ | ||

| siRNA-07 | slincRAD-B7-siRNA | sense strand: 5′-GCAAAUGCCUGCUGACUAAtt-3′ |

| antisense strand: 5′-UUAGUCAGCAGGCAUUUGCtt-3′ | ||

| siRNA-08 | slincRAD-B8-siRNA | sense strand: 5′-CCAGUAAUGGUGCGUGCAAtt-3′ |

| antisense strand: 5′-UUGCACGCACCAUUACUGGt-3′t | ||

| siRNA-09 | slincRAD-B9-siRNA | sense strand: 5′-GCGUGGAUGUGGAGAAAGAtt-3′ |

| antisense strand: 5′-UCUUUCUCCACAUCCACGCt-3′t | ||

| siRNA-10 | slincRAD-B10-siRNA | sense strand: 5′-CAUCAAAGGCUUAAAGAUAtt-3′ |

| antisense strand: 5′-UAUCUUUAAGCCUUUGAUGtt-3′ | ||

| siRNA-11 | slincRAD-B11-siRNA | sense strand: 5′-GCUCUGGAGUGUUGUUUAAtt-3′ |

| antisense strand: 5′-UUAAACAACACUCCAGAGCtt-3′ | ||

| siRNA-12 | slincRAD-C12-siRNA | sense strand: 5′-CCUAGCAGAAACUAAACUUtt-3′ |

| antisense strand: 5′-AAGUUUAGUUUCUGCUAGGtt-3′ | ||

| siRNA-13 | slincRAD-C1-siRNA | sense strand: 5′-GCAGCUGAGCAGUGAUCUUtt-3′ |

| antisense strand: 5′-AAGAUCACUGCUCAGCUGCtt-3′ | ||

| siRNA-14 | slincRAD-C2-siRNA | sense strand: 5′-GGAAGAGGAUGACUAGGAAtt-3′ |

| antisense strand: 5′-UUCCUAGUCAUCCUCUUCCtt-3′ | ||

| siRNA-15 | slincRAD-C3-siRNA | sense strand: 5′-GGAUUAGUGUGGCAGAUUAtt-3′ |

| antisense strand: 5′-UAAUCUGCCACACUAAUCCtt-3′ | ||

| siRNA-16 | slincRAD-C4-siRNA | sense strand: 5′-GCUAAUCUGCCACACUAAUtt-3′ |

| antisense strand: 5′-AUUAGUGUGGCAGAUUAGCtt-3′ | ||

| siRNA-17 | slincRAD-C5-siRNA | sense strand: 5′-CCACUACCCGCCAUGAUUUtt-3′ |

| antisense strand: 5′-AAAUCAUGGCGGGUAGUGGtt-3′ |

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Basic Research Program of China (2011CBA01102), Beijing Natural Science Foundation (5132015), National High-tech R&D Program of China (2012AA022501), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Y2100681), Guangdong Science and Technology Department (2011B090400478) and Hangzhou Science and Technology Bureau (20110733Q21).

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- lncRN

long non-coding RNA

- lincRNA

long intergenic non-coding RNA

- RPKM

reads per kilo bases per million reads

- PPARγ

peroxisome proliferators activated receptor gamma

- C/EBPα

CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha

- TAR

transcriptionally active region

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Buckle P, Buckle J. Obesity, ergonomics and public health. Perspect Public Health. 2011;131:170–6. doi: 10.1177/1757913911407267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guilherme A, Virbasius JV, Puri V, Czech MP. Adipocyte dysfunctions linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:367–77. doi: 10.1038/nrm2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kahn SE, Hull RL, Utzschneider KM. Mechanisms linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2006;444:840–6. doi: 10.1038/nature05482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haemer M, Cluett S, Hassink SG, Liu L, Mangarelli C, Peterson T, et al. Building capacity for childhood obesity prevention and treatment in the medical community: call to action. Pediatrics. 2011;128(Suppl 2):S71–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0480G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chawla A, Lazar MA. Peroxisome proliferator and retinoid signaling pathways co-regulate preadipocyte phenotype and survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1786–90. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.5.1786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tontonoz P, Hu E, Graves RA, Budavari AI, Spiegelman BM. mPPAR gamma 2: tissue-specific regulator of an adipocyte enhancer. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1224–34. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.10.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elbrecht A, Chen Y, Cullinan CA, Hayes N, Leibowitz Md, Moller DE, et al. Molecular cloning, expression and characterization of human peroxisome proliferator activated receptors gamma 1 and gamma 2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;224:431–7. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clarke SL, Robinson CE, Gimble JM. CAAT/enhancer binding proteins directly modulate transcription from the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma 2 promoter. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;240:99–103. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo X, Liao K. Analysis of gene expression profile during 3T3-L1 preadipocyte differentiation. Gene. 2000;251:45–53. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(00)00192-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ibarrola N, Raghothama C, Pandey A. Proteomic analysis of the adipocyte secretome. In: Berdanier, CD and Moustaid-Moussa, N, eds. Genomics and Proteomics in Nutrition. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc, 2004: 393-411. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee HK, Lee BH, Park SA, Kim CW. The proteomic analysis of an adipocyte differentiated from human mesenchymal stem cells using two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Proteomics. 2006;6:1223–9. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lefterova MI, Zhang Y, Steger DJ, Schupp M, Schug J, Cristancho A, et al. PPARgamma and C/EBP factors orchestrate adipocyte biology via adjacent binding on a genome-wide scale. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2941–52. doi: 10.1101/gad.1709008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mercer TR, Dinger ME, Mattick JS. Long non-coding RNAs: insights into functions. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:155–9. doi: 10.1038/nrg2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mikkelsen TS, Xu Z, Zhang X, Wang L, Gimble JM, Lander ES, et al. Comparative epigenomic analysis of murine and human adipogenesis. Cell. 2010;143:156–69. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nielsen R, Pedersen TA, Hagenbeek D, Moulos P, Siersbaek R, Megens E, et al. Genome-wide profiling of PPARgamma:RXR and RNA polymerase II occupancy reveals temporal activation of distinct metabolic pathways and changes in RXR dimer composition during adipogenesis. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2953–67. doi: 10.1101/gad.501108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Payne VA, Au WS, Gray SL, Nora ED, Rahman SM, Sanders R, et al. Sequential regulation of diacylglycerol acyltransferase 2 expression by CAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta (C/EBPbeta) and C/EBPalpha during adipogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:21005–14. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702871200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qiao L, Zou C, Shao P, Schaack J, Johnson PF, Shao J. Transcriptional regulation of fatty acid translocase/CD36 expression by CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:8788–95. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800055200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rahman A, Kumar SG, Kim SW, Hwang HJ, Baek YM, Lee SH, et al. Proteomic analysis for inhibitory effect of chitosan oligosaccharides on 3T3-L1 adipocyte differentiation. Proteomics. 2008;8:569–81. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shao D, Lazar MA. Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma, CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha, and cell cycle status regulate the commitment to adipocyte differentiation. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:21473–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.34.21473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu Z, Xie Y, Bucher NL, Farmer SR. Conditional ectopic expression of C/EBP beta in NIH-3T3 cells induces PPAR gamma and stimulates adipogenesis. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2350–63. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.19.2350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang F, Yi F, Zheng Z, Ling Z, Ding J, Guo J, et al. Characterization of a carcinogenesis-associated long non-coding RNA. RNA Biol. 2012;9:110–6. doi: 10.4161/rna.9.1.18332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trapnell C, Pachter L, Salzberg SL. TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1105–11. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ji P, Diederichs S, Wang W, Böing S, Metzger R, Schneider PM, et al. MALAT-1, a novel noncoding RNA, and thymosin beta4 predict metastasis and survival in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Oncogene. 2003;22:8031–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wagner LA, Christensen CJ, Dunn DM, Spangrude GJ, Georgelas A, Kelley L, et al. EGO, a novel, noncoding RNA gene, regulates eosinophil granule protein transcript expression. Blood. 2007;109:5191–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-027987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siersbæk R, Nielsen R, John S, Sung MH, Baek S, Loft A, et al. Extensive chromatin remodelling and establishment of transcription factor ‘hotspots’ during early adipogenesis. EMBO J. 2011;30:1459–72. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soukas A, Socci ND, Saatkamp BD, Novelli S, Friedman JM. Distinct transcriptional profiles of adipogenesis in vivo and in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:34167–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104421200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guttman M, Amit I, Garber M, French C, Lin MF, Feldser D, et al. Chromatin signature reveals over a thousand highly conserved large non-coding RNAs in mammals. Nature. 2009;458:223–7. doi: 10.1038/nature07672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ulitsky I, Shkumatava A, Jan CH, Sive H, Bartel DP. Conserved function of lincRNAs in vertebrate embryonic development despite rapid sequence evolution. Cell. 2011;147:1537–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khalil AM, Guttman M, Huarte M, Garber M, Raj A, Rivea Morales D, et al. Many human large intergenic noncoding RNAs associate with chromatin-modifying complexes and affect gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:11667–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904715106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siepel A, Bejerano G, Pedersen JS, Hinrichs AS, Hou M, Rosenbloom K, et al. Evolutionarily conserved elements in vertebrate, insect, worm, and yeast genomes. Genome Res. 2005;15:1034–50. doi: 10.1101/gr.3715005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kong L, Zhang Y, Ye ZQ, Liu XQ, Zhao SQ, Wei L, et al. CPC: assess the protein-coding potential of transcripts using sequence features and support vector machine. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(Web Server issue):W345-9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zuo Y, Qiang L, Farmer SR. Activation of CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein (C/EBP) alpha expression by C/EBP beta during adipogenesis requires a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma-associated repression of HDAC1 at the C/ebp alpha gene promoter. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:7960–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510682200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yazgan O, Krebs JE. Noncoding but nonexpendable: transcriptional regulation by large noncoding RNA in eukaryotes. Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;85:484–96. doi: 10.1139/O07-061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prokesch A, Hackl H, Hakim-Weber R, Bornstein SR, Trajanoski Z. Novel insights into adipogenesis from omics data. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16:2952–64. doi: 10.2174/092986709788803132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.