Abstract

This paper examines the residential location and school choice responses to the desegregation of large urban public school districts. We decompose the well documented decline in white public enrollment following desegregation into migration to suburban districts and increased private school enrollment, and find that migration was the more prevalent response. Desegregation caused black public enrollment to increase significantly outside of the South, mostly by slowing decentralization of black households to the suburbs, and large black private school enrollment declines in southern districts. Central district school desegregation generated only a small portion of overall urban population decentralization between 1960 and 1990.

School desegregation was one of the most dramatic social experiments of the 20th century. Although there is growing evidence that desegregation was beneficial for black students (Jonathan Guryan (2004), Byron F. Lutz (2005), David Weiner, Byron F. Lutz and Jens O. Ludwig (2009), Rucker C. Johnson (2010), and Sarah J. Reber (2010, forthcoming)), it also had a number of unintended consequences. This paper examines several of these unintended consequences: the resorting of households within metropolitan areas (MSAs) and shifts in rates of private school attendance. We decompose the well documented decline in white enrollment in desegregated central city public schools into corresponding reductions in the residential population of central school district regions and increases in the private school enrollment of these regions’ residents. These are the first such decompositions produced using a national sample. We also provide some of the first estimates of how black families adjusted their school attendance patterns in response to desegregation.

Our analysis is not only of significant historical interest, it also informs the current debate on the efficacy of school district integration policies. With the 2007 Supreme Court decision striking down public school desegregation policies in Seattle, WA, and Louisville, KY, understanding the effects of school desegregation has considerable contemporary policy relevance. Indeed, Gary Orfield and Susan E. Eaton (1996), Charles T. Clotfelter, Helen F. Ladd and Jacob L. Vigdor (2006) and Lutz (2005) demonstrate that the release of school districts from court supervision that started in the early 1990s has led to resegregation in many cases. Furthermore, Jeffrey M. Weinstein (2010) provides evidence that recent redistricting in the Charlotte-Mecklenburg, North Carolina public school district following the end of court-ordered desegregation induced sizable responses in residential location choices. Understanding the mechanisms by which the original orders of the 1960s and 1970s led to declines in white public school enrollment and increases in black enrollment may be useful in understanding the effects of changes in school assignment policies currently under consideration.

Our analysis also informs the debate about the causes of urban decentralization. Population decentralization within urban areas has been a stark feature of the landscape in the United States since World War Two. Nathaniel Baum-Snow (2007) documents that between 1950 and 1990 the aggregate population living in the 139 largest central cities declined by 17 percent despite large gains in MSA populations. Leah P. Boustan (2010), William J. Collins and Robert A. Margo (2007) and William H. Frey (1992) provide evidence that whites likely made up a disproportionate fraction of this aggregate decline. Indeed, among the 92 large urban school districts examined in this paper, the aggregate white population fell by 13 percent between 1960 and 1990 while the aggregate black population grew by 54 percent over the same period. Peter Mieszkowski and Edwin S. Mills (1993) cite reductions in the quality of local public goods in central cities relative to suburbs as a potentially important explanation for suburbanization. However, other than Julie Berry Cullen and Steven D. Levitt (1999) and this paper, there is little direct empirical evidence on the extent to which changes in local public goods in central cities have generated population decentralization in urban areas.

In order to perform this analysis, we construct a unique data set on the evolution over time of population and enrollment counts by race, school type and detailed spatial location. Four cross-sections of tract level data from the decennial census assigned to school districts using Geographic Information Systems (GIS) software are the building blocks used to construct the relevant data sets used for our analysis. We interpret these data sets using an empirical model which exploits variation across MSAs in the timing of court-ordered school desegregation.

The results suggest that the 6 to 12 percent decline in white public school enrollment due to desegregation, also documented using different data sets by Reber (2005), James S. Coleman, Sara D. Kelly and John A. Moore (1973) and others, manifested itself primarily as migration to suburban districts. However, when we allow for regional variation in the response, we find fairly robust evidence of an increase in private school attendance outside the South while we find no evidence of such a response inside the South. We emphasize, however, that our private school estimates for the South are sufficiently imprecise that we cannot statistically distinguish between estimated effects for the South and the Non-South.

Consistent with the existing evidence that desegregation improved public school quality for black students, we demonstrate that black public enrollment significantly increased by 13 to 20 percent outside the South as a result of desegregation. This coincided with a 6 to 12 percent increase in the black populations of non-southern districts. In addition, private school enrollment of black central district residents declined by more than 40 percent in the South as a result of desegregation.

We also produce spatially disaggregated results which document responses to desegregation as functions of residential location within central school districts. Theories of land use and local public goods motivate this spatial analysis and provide two primary testable predictions. First, models of Charles M. Tiebout (1956) sorting typically assume that the marginal utility of local public goods like school quality is increasing in income. As a result, the highest income individuals in the central district are the most sensitive to changes in school quality associated with desegregation. Because these individuals are most likely to reside near central district fringes (see Appendix Figure A2), we expect responses in public enrollment to be greatest in the outer portions of these regions. Similarly, the magnitudes of total population responses should be greater at central district peripheries. Second, these models predict that those choosing private school live closer to the city center than those choosing public school conditional on income. This ordering comes about because private school attendees achieve the same utility as their public school counterparts with the same income by paying for private school tuition partly with the commuting cost savings from living closer to work.1 Thus, one may expect the most intense response of private school enrollment to desegregation to occur closer to city centers than the most intense responses for public enrollment and total population. We test these two predictions and generally confirm them. The public school and total population changes produced by desegregation largely occurred in the outer portions of central districts while shifts in private school enrollment primarily occurred in the more inner regions of central districts.

Overall, our results indicate that even though the magnitudes of population shifts due to desegregation are not large enough to be responsible for a significant fraction of aggregate population decentralization, they are essential for understanding observed changes in the spatial distribution of the population by race. Had desegregation not occurred, central cities would have populations with a larger fraction of white residents, especially in their more peripheral regions. Moreover, desegregation is important for understanding patterns of private versus public school enrollment for both races.

This paper proceeds as follows. Section II describes the historical context, the data and our empirical strategy. In Section III we present our main results. First, we decompose the effects of school desegregation on central district public enrollment by race into private enrollment and migration responses by region. We then examine the spatial distribution of responses to school desegregation within central school districts. Finally, Section IV concludes.

II. Historical Context and Data

A. Trends in Urban Decentralization by Race

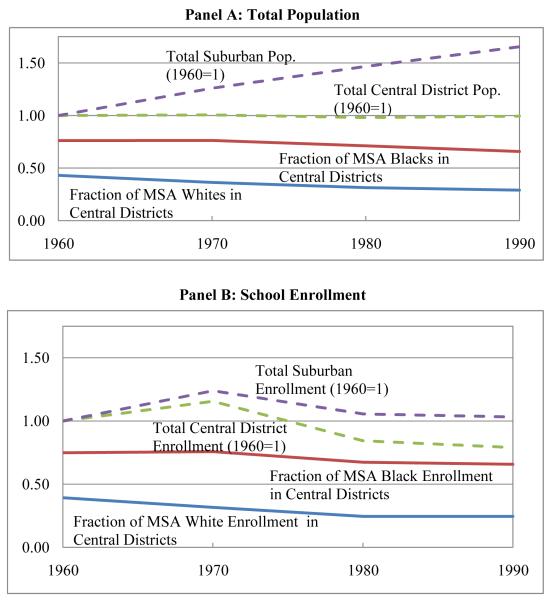

Figure 1 presents data showing the extent of urban population decentralization that occurred between 1960 and 1990. Panel A shows how various components of aggregate white and black MSA populations evolved over time and Panel B shows how white and black K-12 enrollment in MSAs evolved over time. In order to be consistent with the analysis to come, we present statistics using central city school districts, henceforth “central districts,” to represent central urban areas and areas within the central districts’ MSAs, but located outside of central districts, to represent suburbs. We only include the 92 MSAs in our sample with central districts that experienced major court-ordered school desegregation between 1960 and 1990.

Figure 1. Trends in Metropolitan Area Residential Location Patterns by Race.

Note: The top two lines in Panel A show the evolution of aggregate suburban and central district white plus black populations over time in our sample of 92 MSAs. We index year 1960 values to 1. The bottom two lines show the evolution of the fraction of the white and black populations living in central districts. Panel B presents analogous results for the population enrolled in school (K-12).

As has been documented elsewhere, Panel A shows that MSA populations decentralized in each decade between 1960 and 1990. While the white plus black suburban population (dark dashed line) increased in every decade during this period, aggregate white plus black central district population (light dashed line) remained essentially constant. Panel B also shows divergence in the levels of suburban and central district student populations in each decade. However, the high post-WWII fertility rates generated increases in the student populations of both locations between 1960 and 1970 with declines each decade thereafter.

An additional set of facts evident in Figure 1 Panel A has not received as much attention in the economics literature and is thus of particular note. Although central cities were becoming blacker over time, whites and blacks were exiting central cities at similar paces, though the decentralization of blacks did not begin until after 1970. Comparison of the solid lines in Panel A reveals that between 1960 and 1990, the fraction of MSA whites living in central districts declined from 0.43 to 0.29 while that for blacks declined from 0.76 to 0.66. The higher U.S. population growth and urbanization rates of blacks than whites explains how these similar rates of decentralization occurred at the same time as declining central district white populations and increasing central district black populations. Between 1960 and 1990, the U.S. white population grew by 26 percent while the U.S. black population grew by 59 percent. For MSAs in our sample, these numbers are 29 percent and 78 percent respectively.2 Panel B demonstrates that the same conclusions about decentralization by race also hold true for enrolled students.

Although the total black plus white suburban population grew much more rapidly than did the central district population between 1960 and 1990 (at 66 percent and −1 percent, respectively), the similar rates of white and black suburbanization revealed in Figure 1 suggest that this decentralization is not easily explained by racial differences in location patterns. However, inspection of spatially disaggregated data reveals that race-specific factors likely did have some influence on residential location patterns. Specifically, racial sorting at borders between central districts and suburban districts strengthened over time as the peripheral regions of central districts became less white at a quicker pace than immediately adjacent inner regions of the suburbs (see Online Appendix Figure A1). This increased sorting may reflect changes in location incentives for blacks and whites because of race or some other variable correlated with race. Our examinations of income profiles by race as functions of location reveal no discernable discontinuity at central district borders (see Online Appendix Figure A2). Therefore, we conclude that race-specific explanations like school desegregation likely caused these observed changes in residential location patterns

B. Empirical Strategy

In 1954, the Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (347 U.S. 483) stated that segregated schools were unconstitutional. However, the ruling did not impose a mechanism for desegregating the nation’s schools and only limited integration occurred in the 1950s. Many smaller school districts, particularly in the South, desegregated in the 1960s after the Federal Government threatened to withhold Title I financial assistance to districts that continued to discriminate by race (Elizabeth U. Cascio et al., 2008, 2010). However, large school districts, including those located in central cities, were much slower to engage in more than token desegregation. Most large districts did not engage in significant desegregation until forced to do so by separate federal court orders. Heterogeneity across districts in when desegregation court cases were first filed and in the length of time it took these cases to proceed through the judicial system represents plausibly exogenous variation in the timing of school desegregation. It is this variation that we employ to examine the effects of desegregation on residential location patterns and private school choice.

Equation (1) presents our base regression specification for estimating the effects of school desegregation on outcomes of interest.

| (1) |

In this equation, j indexes MSA in region r and t indexes time. Drjt is an indicator for the central school district being desegregated by the courts at time t and yrjt is the outcome of interest. We examine the effects of desegregation on public school enrollment by race, private school enrollment by race and population by race in central districts. Our sample is restricted to urban areas which experienced desegregation. As a result, identification of the parameter of interest, c, requires only that the timing of desegregation be uncorrelated with time-varying unobserved factors that themselves generate outcomes of interest. If the sample included districts which were not desegregated, the identifying assumption would be more restrictive and require that both when and if an area was desegregated be uncorrelated with trends in these unobserved factors that generate outcomes.

Our assumption of pseudo-random timing of desegregation orders conditional on MSA and time-region fixed effects is supported by the fact that following the Brown decision, the NAACP pursued a legal strategy of filing cases where they were most likely to succeed in order to build up a set of legal precedents favorable to desegregation, rather than filing them where the benefit to blacks would be the greatest (Jack Greenberg, 1994).3 In addition, there was variation across districts in the total length of time between the initial filing of cases and final implementation of a major court-ordered desegregation plan. Similar districts had desegregation orders implemented in different years only because of differences in the length of the appeals process. Nonetheless, it remains possible that the timing of desegregation was influenced by factors which also affect location patterns by race. For instance, if areas with more intense housing discrimination tended to desegregate earlier than other areas and also had different location patterns by race, we might spuriously attribute the location pattern to desegregation. The MSA fixed effects are intended to account for such fixed factors that differ across metropolitan areas and may be associated with the timing of school desegregation.

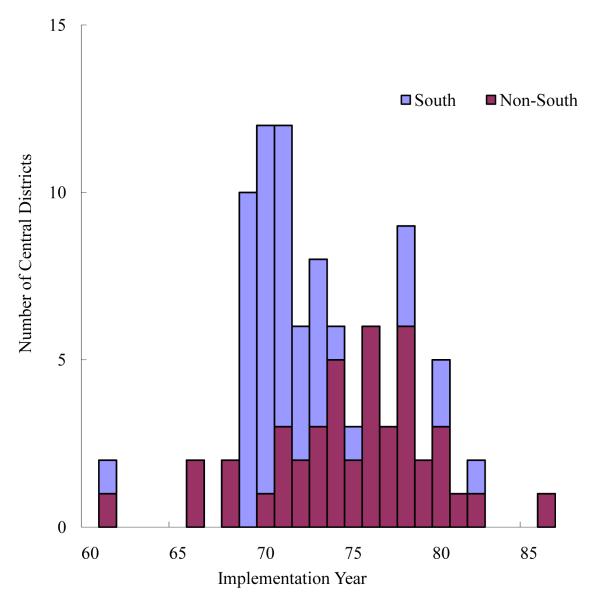

Figure 2 presents a histogram of the timing of central district school desegregation by region. It shows that districts in the South were likely to desegregate earlier than districts in other regions. Indeed, this observation is consistent with the evolution of legal doctrine. The 1968 Green decision (Green v. New Kent County, Virginia, 391 U.S. 430), which established specific factors with which to judge a district’s compliance with the Brown decision, produced a surge of desegregation litigation in the South. The Keyes decision (Keyes v. Denver School District, 413 U.S. 189), issued in 1973, stipulated that court-ordered desegregation could proceed in areas that had de facto segregation resulting from past state action. As a result, desegregation began on a large scale outside the South, where school segregation largely arose from residential housing patterns, not legal mandate. In addition, it is possible that southern and non-southern urban areas decentralized at different times or at different paces because of unobserved factors correlated with the timing of desegregation orders. Such factors include the size of central district geography, the availability of outside options including private schools and suburban districts, income levels, and the extent of housing market discrimination and residential segregation. As such, we allow the year effects in Equation (1), βrt, to differ for the South Census Region.4

Figure 2. Timing of School Desegregation.

Note: The sample includes the 92 central school districts from the Welch and Light (1987) study that experienced major court-ordered desegregation between 1960 and 1990.

We estimate additional specifications as robustness checks that include MSA-specific linear trends or a set of baseline MSA and central district characteristics interacted with year as additional controls. The MSA-specific trends are intended to capture secular trends in outcomes that are specific to MSAs but not related to desegregation. However, if the effect of desegregation evolves over time – i.e. if the treatment effect is more complex than an intercept shift – the trend terms may partially absorb the treatment effect and bias the estimated effect of desegregation downward. One alternative approach would be to explicitly estimate a dynamic treatment effect. Unfortunately, given that we have only four cross-sections of data, attempts to simultaneously identify dynamic treatment effects and MSA specific secular trends generate imprecise estimates. If such dynamic treatment effects exist, estimated coefficients on desegregation indicators in the specification with MSA-specific trends likely represent lower bounds on the true average causal effects of desegregation.

The baseline MSA and central district characteristics interacted with year are intended to control for the possibility that trends in outcomes may be driven by initial factors, such as percent black enrollment in the central district or central district size, that were correlated with the timing of desegregation orders. For instance, higher 1960 black enrollment shares may have hastened the outflow of whites while the longer commute times associated with larger central districts may have impeded this outflow.5

Although these are important checks on the validity of the estimates from our primary specification, it is unsurprising that these robustness check estimates are sometimes imprecise given how saturated the specifications are and our sample size.

To study the spatial distribution of each response to desegregation, we index central district location to be between 0 and 1 in order to make MSAs of different structures and sizes comparable. Location 0 indicates central business districts and location 1 indicates the furthest census tracts from CBDs. The index represents the point in the cumulative distribution function of 1990 black plus white population with tracts ordered by CBD distance. We use census tract data from 1960, 1970, 1980 and 1990 to estimate parameters of this empirical model.

We augment equation (1) by interacting the treatment variable with a set of segmented location indicator variables to capture spatial profiles. Experimentation with specification reveals that splitting the data into four location segments of width 0.25 allows us to efficiently capture the spatial distribution of treatment effects while maintaining power. Because many census tracts contain 0 counts of some outcomes of interest in some years, we utilize a fixed-effects Poisson model.6 This model allows the coefficients to be interpreted as partial elasticities. For each of four location segments s in South and Non-South regions r separately, we thus estimate relevant parameters of the equation

| (2) |

where i indexes census tract in MSA j in region r at time t. The 8 parameters of interest are γrs: four segments each for the South and Non-South. We weight by the inverse of the number of observations in each MSA/segment in order to give equal weight to each MSA and make these estimates comparable to those that come from central district level data. To handle potential spatial correlation in the error term, we bootstrap standard errors using 500 replications sampling MSA clusters with replacement. This bootstrapping procedure is likely to overstate standard errors because it allows the error term within each MSA across space and time to be arbitrarily correlated.

C. Measuring Desegregation

We count a district as being desegregated in the year a major court-ordered school desegregation plan was implemented and thereafter. Usually the court-ordered plan was implemented in September, though in some cases implementation may have occurred before then. In the decennial census we observe residential location as of April 1st and attendance by school type between February 1st and April 1st. Therefore, there is some question as to whether we should instead count a district as being desegregated starting in the year after implementation. Because we do not want to miss responses to plans implemented or announced early in the year, we consider the central district residents exposed to desegregation as of April 1st in the year of implementation. Specification checks on the regression results presented below reveal very similar estimated effects of desegregation when central district residents are instead counted as being exposed as of April 1st in the year after implementation.

Our indicator measure of desegregation is not comprehensive. First, in almost all instances desegregation began on a voluntary basis prior to court intervention. For instance, virtually all southern districts had engaged in at least some desegregation by 1966 (Casico, Lewis and Reber, 2008), although only 2 percent of the southern districts in our sample had experienced major court-ordered desegregation by that time. Second, the amount of desegregation achieved by the courts varied from school district to school district. Nevertheless, we believe that our indicator measure is the best available to us for three reasons. First and most important, court-ordered desegregation was clearly initiated and enforced by an outside body and it is therefore more plausibly exogenous than other more voluntary forms of desegregation. Second, the date of court-ordered desegregation is well measured. Third, for the large districts in our sample, court-ordered desegregation typically induced the single largest decline in racial segregation that the district experienced. In acknowledgement of the drawbacks of our primary desegregation measure, Section III.D presents instrumental variable estimates of the effects of changes in racial contact due to school desegregation on outcomes of interest.

Using the dissimilarity index as an outcome in Equation (1) and data from 1970, 1980 and 1990, we find that court-ordered desegregation in central districts was effective at increasing racial integration. The dissimilarity index ranges from 0 to 1, with 1 denoting complete segregation. The index can be interpreted as the fraction of black students who would need to be reassigned to a different school for perfect integration to be achieved given a district’s overall racial composition. An increase in racial integration causes a decrease in the dissimilarity index. Similar to Reber (2005), we find that desegregation significantly reduced the dissimilarity index an average of 15 points, a bit less than one standard deviation and equal to 21 percent of the index’s mean, where the mean and standard deviation are based on the 1970 cross section. Analogous results are produced by using the white-black exposure index as an alternative outcome. The exposure index gives the percent of black students in the average white student’s school and is thus a measure of interracial contact. Desegregation significantly increased the exposure of whites to blacks by 0.09, equal to around one-half of a standard deviation and one-third of the index’s mean.7

The spatial structure and desegregation environment of suburban districts are likely to influence the benefit to households from moving to or from the suburbs after desegregation is implemented in central districts. Unfortunately, we do not observe the desegregation histories of the suburbs which surround the central districts in our sample. The analysis in Cascio et al. (2008) suggests that virtually all suburban districts in the South underwent meaningful desegregation by 1970, either voluntarily or by court-order. Although we are unaware of any data on the subject, meaningful desegregation activity was likely less intense in non-southern suburban districts because they are much smaller and numerous than southern districts and are more likely to be overwhelmingly white.

We do observe the racial composition of publicly enrolled students in most individual suburban school districts as of 1970. Using these data, we calculate a proxy for the exposure of whites to blacks in the suburbs of each MSA in our sample which both contain a suburban region and have sufficient suburban data in 1970. We make the very conservative assumption that each suburban school district is perfectly integrated, or that its dissimilarity index is 0, and therefore that the suburban exposure index for whites to blacks equals the average percent of enrollment which is black across suburban school districts weighted by the number of white public school students in each district. The results of this exercise indicate that in 1970, only 7 of the 77 MSAs for which we could build data had greater exposure of whites to blacks in the suburbs than the central district. San Jose, which was only 2 percent black, was the only one outside the South. By this conservative measure, whites could reduce their exposure to blacks on average by 0.15 in the South and 0.26 outside the South by moving from a desegregated central district to the suburbs. Because these numbers almost certainly understate the reduction in exposure, given the assumption of perfect suburban integration, it is safe to assume that in most metro areas in the South and Non-South alike, relocation to the suburbs was an avenue for whites to substantially reduce their exposure to blacks in school.

D. Remaining Data

Our empirical analysis benefits from a unique data set that includes information from the decennial Censuses of Population 1960-1990. The data set includes information on school enrollment by school type and additional demographic information by race for those living in central school districts and MSA remainders. Our sample is comprised of 48 MSAs in the South Census Region and 44 in other regions with central school districts identified by Finish R. Welch and Audrey L. Light (1987) as having experienced a major court-ordered desegregation plan between 1960 and 1990.8 We define central districts as those school districts that included the central business districts of the largest census defined central city as of 1960 in each MSA nationwide. The sample includes all 56 central districts of over 50,000 students with minority enrollment between 20 and 80 percent in 1968 other than New York City, which did not have a major desegregation order. The remaining 36 districts, which had enrollment over 15,000 and were between 10 and 90 percent minority in 1968, were randomly sampled with enrollment and region sampling weights.9

In order to limit the possibility that school district boundaries were drawn in response to pressure for desegregation, we utilize 1970 school district geographies.10 The “69-70 School District Geographic Reference File” (Bureau of Census, 1970) relates census tract and school district geographies. For each census tract in the country, it provides the fraction of the population that is in each school district. Using this information, we aggregate census tracts to 1970 district geographies with Geographic Information Systems (GIS) software. We assign census tracts from 1960, 1980 and 1990 to school districts using this resulting digital map based on their centroid locations.

We use census tract and county tabulations from 1960 to 1990 to build census tract, central district and 1999-definition MSA demographic data over time. We only observe spatially disaggregated data for 78 districts in 1960 and 89 districts in 1970. The spatially disaggregated tract level geography allows us to analyze the extent to which effects of desegregation differ across space within central districts. We define each MSA’s central business district (CBD) as the centroid of the set of CBD census tracts reported in the 1982 Economic Census. A more complete explanation of the data construction is in the Data Appendix. Summary statistics and sample characteristics of the district and tract data sets are in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary Statistics

| 1960 | 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Central District Means and Standard Deviations | ||||

| Log (White Public Enrollment) | 10.52 (0.72) |

10.59 (0.71) |

10.07 (0.75) |

9.94 (0.82) |

| Log (White Private Enrollment) | 8.66 (1.40) |

8.67 (1.28) |

8.60 (1.05) |

8.47 (0.96) |

| Log (Black Public Enrollment) | 9.00 (1.20) |

9.53 (1.16) |

9.52 (1.10) |

9.59 (1.03) |

| Log (Black Private Enrollment) | 6.05 (1.75) |

6.02 (1.58) |

6.40 (1.51) |

6.49 (1.43) |

| Log(Total White Population) | 12.35 (0.82) |

12.34 (0.76) |

12.28 (0.74) |

12.25 (0.78) |

| Log(Total Black Population) | 10.56 (1.20) |

10.78 (1.18) |

11.00 (1.11) |

11.13 (1.05) |

| Fraction of Metropolitan Land Area in the Central District |

0.20 (0.29) |

0.20 (0.29) |

0.20 (0.29) |

0.20 (0.29) |

| Number of Districts in the Metropolitan Area |

35.21 (46.04) |

34.25 (43.23) |

33.97 (42.56) |

|

| Desegregated Districts | 0 | 28 | 88 | 92 |

| Desegregated Districts (5+) | 0 | 4 | 69 | 92 |

| Panel B: Mean Central District Private School Enrollment Shares | ||||

| White Private Share | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.22 | 0.21 |

| White Private Share - South | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.18 |

| White Private Share - Non-South | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Black Private Share | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Black Private Share - South | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| Black Private Share - Non-South | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| Panel C: Census Tract Sample | ||||

| Total Tracts | 8,044 | 9,555 | 10,293 | 10,758 |

| Desegregated Tracts | 0 | 1,802 | 9,328 | 10,758 |

| Desegregated Tracts (5+) | 0 | 416 | 6,543 | 10,758 |

| Central Districts With Tract Data | 78 | 89 | 92 | 92 |

III. Results

A. Whites

Table 2, Panel A, presents our estimates of the effects of desegregation on white public school enrollment in central districts. Consistent with Reber’s (2005) results using district reported enrollment data, our preferred Specification 1 indicates that desegregation orders decreased white enrollment by an average of 12 percent in central districts. In Specification 2 the coefficient attenuates to 0.06 with the inclusion of MSA-specific linear time trends and is only marginally significant. In Specification 3 the coefficient of interest declines by only 0.02 with inclusion of MSA and central district baseline characteristics measured in 1960 or 1970 interacted with year effects. Thus, these characteristics appear to have a low correlation with the timing of desegregation orders conditional on MSA and year-south fixed effects. Specification 4 allows the effect of desegregation to vary by the length of time a district has been desegregated. The point estimates suggest that the long-run impact of desegregation is a bit smaller than the short-run impact. The long-run impact is defined as exposure to desegregation for at least five years and is calculated as the sum of the two coefficients. However, the decline in the response after five years of 0.04 is not statistically significant.11

Table 2.

Impacts of School Desegregation on Outcomes for Whites

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: ln(white public enrollment in central district) | |||||

| Desegregated | −0.12** (0.05) |

−0.06* (0.03) |

−0.10*** (0.04) |

−0.12*** (0.05) |

−0.12* (0.07) |

| Desegregated (5+) | 0.04 (0.05) |

||||

| Placebo Desegregated | −0.00 (0.08) |

||||

| Panel B: ln(white private enrollment in central district) | |||||

| Desegregated | 0.03 (0.07) |

0.08 (0.07) |

0.05 (0.08) |

0.03 (0.07) |

0.06 (0.09) |

| Desegregated (5+) | 0.01 (0.09) |

||||

| Placebo Desegregated | 0.06 (0.10) |

||||

| Panel C: ln(white population of central district) | |||||

| Desegregated | −0.06* (0.03) |

−0.02 (0.02) |

−0.05* (0.03) |

−0.07** (0.03) |

−0.06 (0.05) |

| Desegregated (5+) | 0.06 (0.04) |

||||

| Placebo Desegregated | 0.01 (0.07) |

||||

| MSA & Year-South FE | X | X | X | X | X |

| MSA Specific Linear Trends | X | ||||

| MSA Characteristics * Year Effects | X | ||||

Note: The sample includes the 92 central school districts with a major desegregation order between 1960 and 1990. Each regression has 368 observations. Dependent variables are in panel headings. Desegregated is an indicator equaling one in years in which the district is under a desegregation plan. Placebo Desegregated equals one if the district was to be desegregated in one or two years. Desegregated (5+) equals one in the 5th year of desegregation and beyond. For Specification 3, MSA characteristics measured as of 1960 are percent black public enrollment in the central district, log median black income in the central district, log median white income in the central district and percent of MSA employment in manufacturing. MSA characteristics measured as of 1970 are number of districts in the MSA and log central district area. Log MSA area is also included and measured as of 1999. Standard errors are clustered at the central district level.

Specification 5 presents a falsification exercise. A placebo treatment variable is added to the model which equals one when a district is one or two years away from being desegregated. If school desegregation was implemented in areas where white flight from public schools was already occurring, rather than being causally related to white flight, the coefficient on the placebo variable should be negative and significant. Instead, the estimated placebo coefficient is equal to −0.00 and is imprecisely estimated. Moreover, the estimated parameter of interest does not change with its inclusion. The 0 placebo coefficient estimate provides suggestive evidence that the specification with the MSA-specific trends (Specification 2) likely generates attenuated coefficients on the desegregation indicator. Specifically, it suggests that the trend terms are at least partially identified off of post-desegregation movements in outcomes, movement that could be causally related to desegregation. If trends were spuriously inflating the estimated effect of desegregation, the placebo coefficient should be negative.

Panel B presents estimates of the effect of desegregation on central city white private school enrollment. These estimates are positive but imprecisely estimated. The response of total central district school enrollment (public plus private) to desegregation can be calculated as averages of the coefficients in Panels A and B weighted by public and private enrollment shares.12 As we report in Panel B of Table 1, an average of 17 percent of white students living in central districts in 1960 were attending private schools in our sample. Thus, the estimates from Specification 1 suggest that total white school enrollment in central districts fell by about 9 percent (−.12*0.83+0.03*0.17) due to desegregation. We use a similar calculation to decompose the white public enrollment reduction into flows to private schools and migration out of central districts. Based on Specification 1, only 5 percent ([0.03*0.17]/[−0.12*0.83]) of the white students leaving central district public schools due to desegregation moved to central district private schools with the remaining 95 percent migrating out of central districts.

Panel C presents estimates of the impact of desegregation on total white central district population. These estimates capture the extent to which changes in school attendance patterns spill over into changes in total population. The estimate from our base specification, Specification 1, suggests that desegregation induced 6 percent of the white population to exit central districts on average. This estimate is robust to controls for baseline characteristics interacted with year effects but attenuates to a statistically insignificant −0.02 with inclusion of MSA-specific linear trends. Viewed jointly, the three panels of Table 2 indicate that white flight from desegregated central district public schools manifested itself largely as migration to suburban school districts and perhaps partly as increases in private school enrollment.

In Table 3 we allow the effects of desegregation to vary by region. There are a number of reasons why the effect of desegregation in the South may have differed from the effect in the rest of the country. The South differs from other regions along many observable dimensions: It has lower average income and a substantially higher fraction of the population which is black. As suggested by the different forms that racial segregation took – de jure in the south and de facto elsewhere – preferences over interracial contact may also have varied by region. The structure of MSAs in the South is also quite different from that in other regions. The average number of school districts in southern MSAs is 12 relative to 60 in other regions and each of the 20 MSAs in our sample with fewer than 5 school districts is in the South.

Table 3.

Impacts of School Desegregation on Outcomes for Whites by Region

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: ln(white public enrollment in central district) | ||||

| (Deseg)*(South) | −0.14** (0.07) |

−0.04 (0.05) |

−0.10 (0.06) |

−0.14** (0.07) |

| (Deseg)*(Non-South) | −0.08* (0.05) |

−0.10*** (0.04) |

−0.10* (0.05) |

−0.08 (0.05) |

| (Deseg 5+)*(South) | 0.08 (0.11) |

|||

| (Deseg 5+)*(Non-South) | 0.00 (0.06) |

|||

| Panel B: ln(white private enrollment in central district) | ||||

| (Deseg)*(South) | −0.04 (0.10) |

0.07 (0.10) |

0.04 (0.13) |

−0.04 (0.10) |

| (Deseg)*(Non-South) | 0.16** (0.08) |

0.11** (0.05) |

0.07 (0.07) |

0.17** (0.09) |

| (Deseg 5+)*(South) | 0.03 (0.22) |

|||

| (Deseg 5+)*(Non-South) | −0.04 (0.07) |

|||

| Panel C: ln(white population of central district) | ||||

| (Deseg)*(South) | −0.12*** (0.04) |

−0.03 (0.03) |

−0.08* (0.04) |

−0.13*** (0.04) |

| (Deseg)*(Non-South) | 0.04 (0.04) |

−0.00 (0.01) |

−0.01 (0.03) |

0.04 (0.05) |

| (Deseg 5+)*(South) | 0.11 (0.07) |

|||

| (Deseg 5+)*(Non-South) | 0.01 (0.04) |

|||

| MSA & Year-South FE | X | X | X | X |

| MSA Specific Linear Trends | X | |||

| MSA Characteristics * Year Effects | X | |||

In the South, our baseline specification indicates a large public enrollment decline of 14 percent (Panel A) due to desegregation. There is no evidence for a private school response. The relevant point estimate in Panel B is small and very imprecise, suggesting that most of the students who exited central district public schools choose to attend a suburban school. The large total population decline estimate of 12 percent (Panel C) is consistent with this interpretation. While the private school results are consistently imprecise across the additional specifications, the inclusion of the MSA-specific trends in Specification 2 greatly attenuates both the public school and total population estimates.

Outside of the South, the baseline specification produces evidence that desegregation reduces central city public enrollment by 8 percent (Panel A). However, unlike for the South, there is strong evidence of a large private school response of 16 percent (Panel B).13 Given that an average of 24 percent of whites attended private school outside of the South in 1960, these estimates suggest a total central district (public plus private) enrollment decline of only 2 percent and that 63 percent of the students who left central district public schools subsequently enrolled in private school. The lack of evidence for a total population decline (Panel C) bolsters the contention that private schools were an important destination for whites exiting non-southern desegregated central city public districts. Specifications 2 and 3 respectively suggest that 35 percent and 22 percent of the decline in central district public enrollment flowed into private schools. Although these are smaller percentages than indicated by Specification 1, they remain consistent with private schools having been an important margin of adjustment to desegregation outside of the South.14

To the best of our knowledge, the private school estimates in Tables 2 and 3 are the first of the causal connection between court-ordered desegregation and white private school enrollment produced using a national sample.15 A lack of nationwide data on private school enrollment by race at the district level likely has prevented a systematic exploration of the link between court-ordered desegregation and white private school enrollment up to this point. Our unique data set allows us to fill this gap in the literature.

The desegregation literature has generally concluded that private schools represented an important outlet for southern whites wishing to avoid desegregated schools. This conclusion is based on several facts (Clotfelter, 2004a). First, white private school enrollment has increased in the South since 1960 while it has fallen in the rest of the country. Desegregation is often cited as an explanation for this regional divergence because it produced a much greater change in public school racial composition in the South than it did elsewhere. Second, there are several well documented cases of white flight to private school in response to desegregation in the South, for instance Mississippi’s “segregation academies” and Virginia’s “massive resistance.” Finally, the large average size of southern school districts meant that migration to alternative public school districts was usually costly, making private schools a relatively more attractive option.

While the results of this paper lend no support to the hypothesis that whites used private schools to avoid court-ordered desegregation in the South, they do not invalidate the hypothesis either. Our point estimate for the South is sufficiently imprecise that we cannot reject a positive response of white private enrollment to desegregation in central districts: The upper bound of the white private school enrollment estimate’s 95% confidence interval from Specification 1 is a sizeable 16 percent increase. Nor are we able to statistically distinguish between the private school response in the South and the private school response elsewhere. Furthermore, the sample used here is comprised of large urban centers. White flight to private school may have been more prevalent in non-urban areas of the South because the large, generally county-wide, school districts in the non-metropolitan South make avoiding desegregation through residential relocation difficult. Indeed, the most direct evidence that desegregation increased private school enrollment in the South by Clotfelter (1976) and Reber (forthcoming) are focused on the mostly rural states of Mississippi and Louisiana. Finally, Clotfelter (2004a, 2004b) demonstrates that the contribution of private schools to overall school segregation is substantially greater in the non-metropolitan South than in the South’s urban areas.

We have provided some evidence that at least in the South there was white flight from central districts after they desegregated. Using the entire MSA as the geography for which we measure outcomes, we find small and imprecisely estimated coefficients. (See Online Appendix Table A3.) These results suggest that the whites who departed central districts in response to desegregation moved to the suburbs within the same MSA. Estimates of the effects of central district desegregation on suburban white population and public enrollment are generally positive but with large standard errors such that none is statistically significant (unreported). Given the explosive growth of the suburbs evident in Figure 1, it may be more difficult to generate precise estimates for the suburbs than it is for the central districts. We would have liked to report more spatially disaggregated results which focus on effects in inner suburbs because these areas are likely close substitutes for central districts. Unfortunately many suburbs were not tracted in 1960 and 1970 making such estimates imprecise and unstable.

B. Blacks

Guryan (2004) and Lutz (2005) present evidence that school desegregation reduced dropout rates for blacks, suggesting that desegregation generated an improvement in school quality experienced by blacks. Moreover, Reber (2010, forthcoming) documents that desegregation increased the educational resources provided to black students and increased their test scores and Weiner, Lutz and Ludwig (2009) demonstrate that desegregation decreased rates of criminal offending by black youth. The natural implication is that blacks should seek to attend newly integrated school systems. Table 4 Panel A provides evidence to this effect. Although there is no evidence of black public enrollment increases due to desegregation when desegregation is coded as a single indicator variable equaling one in any year in which public schools were desegregated (Specification 1), we do find evidence of a 14 percent increase in black enrollment in the long-run, defined as at least five years after implementation of desegregation (Specifications 2 and 3). This result is robust both to inclusion of MSA-specific linear trends (Specification 4) and 1960 MSA characteristic–year interactions (Specification 5). It is also robust to alternative specification of the distributed lag (unreported). Finally, the results of the placebo falsification check are encouraging.

Table 4.

Impacts of School Desegregation on Outcomes for Blacks

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: ln(black public enrollment in central district) | ||||||

| Desegregated | 0.02 (0.03) |

−0.00 (0.03) |

||||

| Desegregated (5+) | 0.14*** (0.03) |

0.14*** (0.03) |

0.09*** (0.03) |

0.12*** (0.03) |

0.14*** (0.04) |

|

| Placebo Desegregated | 0.02 (0.03) |

|||||

| Panel B: ln(black private enrollment in central district) | ||||||

| Desegregated | −0.20 (0.14) |

−0.16 (0.13) |

||||

| Desegregated (5+) | −0.18* (0.10) |

−0.22** (0.10) |

−0.24*** −0.1 |

−0.28*** (0.11) |

−0.20** (0.10) |

|

| Placebo Desegregated | 0.06 (0.16) |

|||||

| Panel C: ln(black population of central district) | ||||||

| Desegregated | 0.01 (0.03) |

−0.01 (0.03) |

||||

| Desegregated (5+) | 0.08*** (0.03) |

0.08*** (0.03) |

0.04* (0.02) |

0.06** (0.02) |

0.08*** (0.03) |

|

| Placebo Desegregated | 0.02 (0.03) |

|||||

| MSA & Year-South FE | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| MSA Specific Linear Trends | X | |||||

| MSA Characteristics * Year Effects | X | |||||

Note: See note to Table 2 for an explanation of the sample and variables. Sample size is 368 in Panels A and C and 367 in Panel B because San Jose had 0 black private school students in 1970.

Results in Table 4 Panel B indicate that desegregation dramatically reduced private school enrollment of blacks living in central districts. This response commenced immediately following the announcement of desegregation orders but also may have strengthened considerably with time. Our point estimates indicate a 16 percent immediate decline in black private enrollment following desegregation with an additional 18 percent decline 4 years later (Specification 2). These individual estimates are not precise although the total long-run effect, the sum of these two coefficients, is statistically significant. We can more precisely estimate that after five years of desegregation black private enrollment declined by 20 to 28 percent (Specifications 3 to 6). While these are very large responses, they come off a relatively small base of black private school students. In 1960, an average of only 7 percent of black students living in central districts in our sample attended private school. Combining this number with the estimates from Specification 3 suggests that 12 percent of the black flow into desegregated central district public schools came from private schools. The possibility that blacks exited private schools in order to enroll in desegregated public schools, while quite plausible given the documented increase in public school quality caused by desegregation, has received little consideration in the literature.

Table 4 Panel C presents evidence that desegregation increased the total black population of central districts by 8 percent. The specification with MSA-specific trends generates a marginally significant coefficient of 0.04 that we view as a lower bound on the true causal effect. Investigation of various distributed lag specifications (unreported) reveals that these increases in black population occurred concurrently with the increases in public enrollment documented in Panel A.

Black responses to desegregation display striking regional heterogeneity. Table 5 Panel A shows that the increase in black enrollment in desegregated schools is almost entirely a non-southern phenomenon. Specification 2 indicates that this black enrollment increase outside the South commenced five years after desegregation orders were implemented. We estimate that black public enrollment ultimately increased by 13 to 20 percent outside the South. In contrast, the southern point estimates are about 0 and statistically distinguishable from the Non-South estimates.

Table 5.

Impacts of School Desegregation on Outcomes for Blacks by Region

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: ln(black public enrollment in central district) | |||||

| (Deseg)*(South) | −0.03 (0.04) |

−0.03 (0.04) |

|||

| (Deseg)*(Non-South) | 0.11** (0.05) |

0.02 (0.04) |

|||

| (Deseg 5+)*(South) | 0.00 (0.04) |

0.00 (0.04) |

0.01 (0.05) |

0.02 (0.05) |

|

| (Deseg 5+)*(Non-South) | 0.20*** (0.04) |

0.20*** (0.04) |

0.13*** (0.04) |

0.17*** (0.04) |

|

| Panel B: ln(black private enrollment in central district) | |||||

| (Deseg)*(South) | −0.40** (0.18) |

−0.38** (0.17) |

|||

| (Deseg)*(Non-South) | 0.13 (0.18) |

0.21 (0.16) |

|||

| (Deseg 5+)*(South) | −0.42* (0.22) |

−0.45** (0.23) |

−0.42** (0.19) |

−0.62*** (0.22) |

|

| (Deseg 5+)*(Non-South) | −0.16* (0.09) |

−0.10 (0.10) |

−0.15 (0.09) |

−0.11 (0.12) |

|

| Panel C: ln(black population of central district) | |||||

| (Deseg)*(South) | −0.01 (0.03) |

−0.01 (0.03) |

|||

| (Deseg)*(Non-South) | 0.04 (0.04) |

−0.02 (0.04) |

|||

| (Deseg 5+)*(South) | −0.00 (0.05) |

−0.01 (0.05) |

0.00 (0.04) |

−0.02 (0.06) |

|

| (Deseg 5+)*(Non-South) | 0.12*** (0.03) |

0.11*** (0.03) |

0.06** (0.02) |

0.09*** (0.02) |

|

| MSA & Year-South FE | X | X | X | X | X |

| MSA Specific Linear Trends | X | ||||

| MSA Characteristics * Year Effects | X | ||||

Unlike the public enrollment results, Panel B indicates that the decline in private school enrollment due to desegregation was much larger in the South than elsewhere. By our estimates, after 5 years of desegregation black private enrollment in the South declined by 40 to 80 percent, with the 80 percent estimate obtained by adding the two south coefficients in Specification 2 together. Consistent with evidence in Table 4 Panel B, Specification 2 indicates that the response started immediately after desegregation and increased with time.16 We find little evidence that desegregation caused declines in black private enrollment outside the South. In Specifications 1, 2 and 5 the south estimates are statistically different from the non-south estimates. (In Specification 2 the south and non-south deseg(5+) coefficients cannot be distinguished from each other, but the long-run effects can be distinguished.) Because so few blacks were in private schools in 1960 – an average of 4 percent in the South and 11 percent elsewhere – it is not surprising that these private school results are not closely related to the total public enrollment results in Panel A.

Consistent with the results in Panel A, Panel C documents that the increase in black central district population due to desegregation, estimated to be 6 to 11 percent (Specifications 2 to 5), also occurred only outside of the South and started about five years after desegregation plan implementation. However, the non-south estimate is statistically different from that for the South only in specification 3.17

Unlike for whites, estimated effects of desegregation for blacks are often statistically distinguishable across regions. We therefore explore if these regional differences are explained by characteristics observed in our data. Inclusion of the desegregation treatment variable interacted with baseline MSA characteristics does not significantly reduce regional gaps in the effects of desegregation and the interaction coefficients are typically imprecisely estimated (unreported). Thus, we conclude that unobserved differences between MSAs in the South and other regions are primarily responsible for the differences in treatment effects of desegregation for blacks. These unobserved characteristics may be pure region effects related to tastes or more easily quantifiable factors which are not available in our data. Our examination of suburban black outcomes turns up similarly inconclusive evidence as that for suburban white outcomes.

C. Results by Age Group

The underlying process that we postulate generates the observed relationship between school desegregation, white flight and black inflows from and to central districts operates through public school quality. Therefore, we should see that responses are greater for school age children and their parents than for other age groups.18 We investigate this possibility by estimating the effects of school desegregation on population by age, using the same specifications as in Specification 1 of Table 2 for whites and Specification 3 of Table 4 for blacks.19

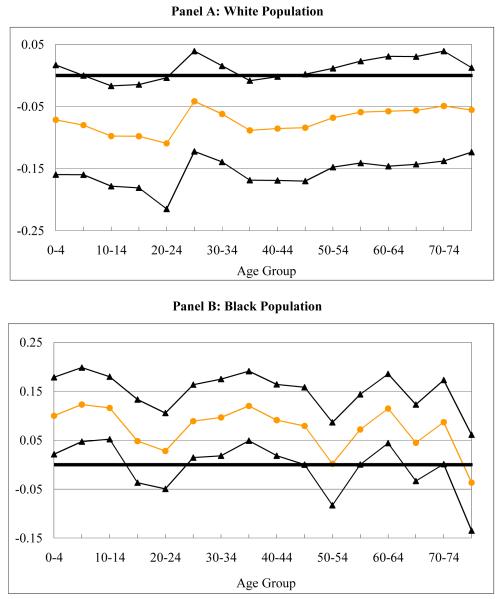

Figure 3 depicts estimated impacts of desegregation on central district population by age and race. Panel A shows that white flight was most pronounced among those aged 5-24, roughly the age of children in school, and 35-44, roughly the age of parents with children in school. These estimates are statistically significant and are equal to about −0.10 for the young group and −0.09 for the parental group. Estimates for other age groups range from −0.05 to −0.08 but are not statistically significant.

Figure 3. Impacts of School Desegregation on Total Population by Age.

Note: Graphs show 95% confidence intervals around point estimates of the effects of desegregation on population by race and age in central districts. Each point estimate is the coefficient on the desegregation dummy variable from separate regressions of log total population for each age group listed on the x-axis on independent variables in Table 2 Specification 1 for whites and Table 4 Specification 3 for blacks.

The black estimates shown in Figure 3 Panel B indicate in-migration in response to desegregation was greatest for those aged 0-14, 25-49 and 55-74. Each of these groups has a precisely estimated population increase of around 12 percent after 5 years of desegregation. In contrast to whites, blacks in other age groups have much smaller estimated responses

D. The Effects of Racial Dissimilarity on Outcomes

While the reduced form effects of school desegregation presented above are informative, it is potentially even more informative to directly measure responses to changes in the racial composition of schools. As discussed is Section II, court-ordered desegregation boosted racial integration by different amounts across school districts because it was achieved in many different ways and was applied in many different initial school assignment environments. In particular, the extent of voluntary desegregation prior to court intervention varied. To this end, we estimate the effects of racial dissimilarity in regressions analogous to those in Tables 2 through 5 using our desegregation indicator as an instrument for the dissimilarity index. Estimation of the effects of racial dissimilarity comes with some difficulties, foremost of which is that we do not observe school racial composition for many districts before the late 1960s and there is some missing data thereafter as well. The Data Appendix details how we impute some of the missing data and infer values for 1960 using information from Cascio et al. (2008). In addition, it is potentially problematic to interpret these results as strictly causal estimates of the impact of the dissimilarity index. In addition to increasing racial integration, desegregation may have induced other changes, such as increases in public school spending (Reber 2010, Johnson 2010) and decreases in criminal offending (Weiner, Lutz and Ludwig, 2009). The dissimilarity index coefficients from the IV specifications may partially reflect these other changes.20 Nonetheless, we believe the IV specifications are useful because they force the effect of desegregation to operate through the hypothesized primary mechanism: changes in school quality resulting from abrupt shifts in racial segregation.

Table 6 presents IV estimates of the effects of racial dissimilarity on our six outcomes of interest. As in Tables 4 and 5, the treatment for blacks is lagged by 5 years. We utilize two instruments: the desegregation indicator and this indicator interacted with a West Census Region indicator. Our data suggest that court-ordered desegregation was relatively less effective at decreasing black-white dissimilarity in the West Census Region and thus including this interaction term results in more precise second-stage estimates.21 For whites, the first-stage coefficient on the segregation indicator is −0.17 (s.e. 0.04) and the coefficient on the segregation*west term is 0.20 (s.e. 0.13). The first-stage F-statistic on this instrument set is 10.0.

Table 6.

IV Impacts of the Dissimilarity Index

| ln(Public Enrollment) |

ln(Private Enrollment) |

ln(Pop- ulation) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Panel A: Whites | |||

| Dissimilarity Index | 0.73** (0.33) |

0.19 (0.50) |

0.49* (0.28) |

| Dissimilarity Index * South | 0.99* (0.52) |

0.86 (0.67) |

0.96** (0.43) |

| Dissimilarity Index * Non-South | 0.30 (0.25) |

−0.97*** (0.33) |

−0.33 (0.26) |

| Panel B: Blacks | |||

| Dissimilarity Index (5+) | −0.40** (0.17) |

1.63*** (0.46) |

−0.14 (0.13) |

| Dissimilarity Index (5+) * South | −0.03 (0.14) |

2.02*** (0.75) |

0.01 (0.19) |

| Dissimilarity Index (5+) * Non-South | −0.76*** (0.24) |

1.31*** (0.48) |

−0.28 (0.19) |

| MSA & Year-South & West FE | X | X | X |

Note: Entries give coefficients and standard errors from IV regressions of central district outcomes listed in the column headings on the dissimilarity index. Within each column-panel combination, the results of two regressions are displayed: one which does not allow for regional heterogeneity and one that does permit regional heterogeneity. The desegregation indicator and the desegregation indicator interacted with an indicator for the West Census Region enter as instruments for the dissimilarity index in the first-stage (not shown). In Panel B, the dissimilarity index is measured 4 years prior to outcomes and is instrumented with the desegregation (5+) indicator used in Tables 4 and 5 and the desegregation (5+) indicator interacted with an indicator for the West Census region. For the regressions allowing regional heterogeneity, the segregation indicator is interacted with South and Non-South indicators. (The West interaction is also included and there are therefore three instruments and two first-stages in these specifications.) Standard errors are clustered at the MSA level. There are 313 observations in Panel A and 305 observations in Panel B. See the Data Appendix for information on the construction of the dissimilarity index variable. The first-stage F-statistics are 10.0 (Panel A, no regional heterogeneity), 9.1 (Panel A, South), 11.4 (Panel A, Non-South), 16.8 (Panel B, no regional heterogeneity), 10.8 (Panel B, South) and 11.4 (Panel B, Non-South).

Panel A displays the second-stage results for whites. For each outcome, the results of specifications with and without regional heterogeneity are displayed. The estimated effects of dissimilarity are very consistent with the results in Tables 2 and 3. For instance, the estimate in the first row of Specification 1 suggests that a decrease in the dissimilarity index of 0.15, or about the typical change in dissimilarity achieved by court-ordered desegregation, would reduce white public school enrollment by about 11 percent, similar to the estimates in Panel A of Table 2. The black IV estimates, presented in Panel B, are also generally consistent with the reduced form effects of desegregation in Tables 4 and 5 with a few differences. There is less evidence of a total black population effect and the implied increase in non-south black public enrollment of 0.11, is smaller than that in Table 5 of around 0.20. IV estimates also show stronger evidence of a black private school response outside of the South.22

E. The Spatial Distribution of Responses to Desegregation

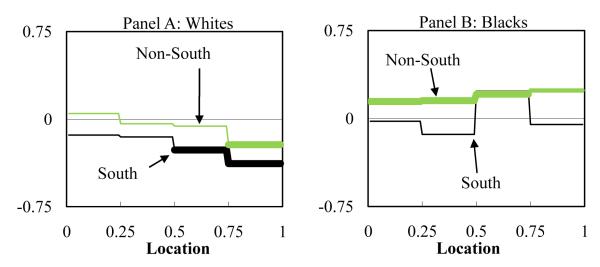

In this subsection we explore the spatial dimension of responses to desegregation. Specifically, we test the two hypothesis discussed in the introduction, both motivated by standard models of Tiebout sorting and land use. The first hypothesis predicts that the public enrollment and population responses will be most intense in the outer regions of the central city where the wealthiest individuals tend to reside. These individuals likely place high marginal values on local public goods such as schooling and will therefore be the most responsive to changes in the perceived quality of education services. The second hypothesis predicts that the greatest private school enrollment response will occur closer to city centers than those of public enrollment and total population. Individuals who choose private schooling tend to live near the city center, holding income constant, so they can be compensated for tuition payments with shorter commutes. We first estimate the effects of school desegregation on white and black public school enrollment as functions of location using Equation 2.23 When white outcomes are used, Drjt equals one if the central district has been desegregated at time t. Consistent with the evidence in Tables 4 and 5, Drjt equals one if desegregation occurred at least five years earlier when one of the outcomes for blacks is the dependent variable.

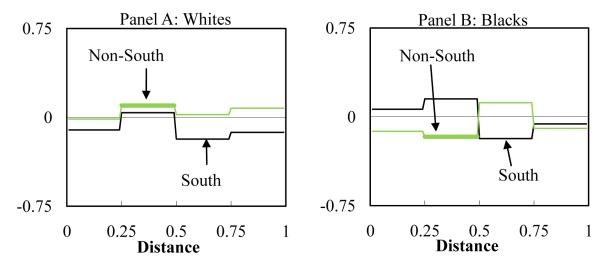

Figure 4 presents the public enrollment results. It graphs the estimated effects of desegregation in the South and other regions separately. Medium thickness portions of the plots indicate statistical significance at the 10 percent level and the thickest line portions are significant at the 5 percent level. Panel A shows that desegregation caused white enrollment in the outer fourth of central districts to fall significantly by about 22 percent outside the South and 38 percent in the South. In the third segment of southern central districts we estimate that desegregation caused a 26 percent decline in white enrollment. Estimated enrollment effects of desegregation are not statistically significant in other region-location combinations, though point estimates are monotonically decreasing in CBD distance for both regions. These results are consistent with the estimates reported in Table 2 indicating a 12 percent decline in total central district white enrollment as a result of desegregation. They also suggest that the larger enrollment decline in the South reported in Table 3 is partly accounted for by the fact that the enrollment response extended closer to the CDB in the South than it did elsewhere.

Figure 4.

Impacts of School Desegregation on Public School Enrollment

Estimated effects for blacks outside the South, shown in Panel B, are largely a mirror image of those for southern whites. Black public school enrollment outside the South increased by an estimated 24 percent in the outer segment after exposure to desegregation for four years, monotonically decreasing to 15 percent in the first segment, roughly the same size effect as found in Table 4. The estimates for black public enrollment in the South are uniformly imprecise, consistent with the failure to find evidence of a response for this outcome with the non-spatial approach.

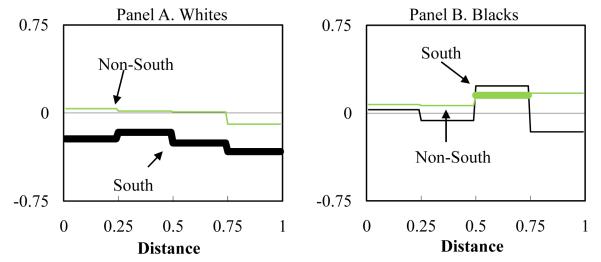

Figure 5 shows the spatial results for white and black private school enrollment. It shows that desegregation led to a statistically significant increase of 10 percent in white private school enrollment in the second segment of central districts outside the South. No other white private enrollment estimates are statistically significant. Panel B shows that the only segment in which black private enrollment significantly declined due to desegregation is the second segment outside the South, by 17 percent. Black private enrollment is the only outcome for which the results using the spatially disaggregated data do not match those using aggregate central district data.24 Consistent with theory, our results indicate that private enrollment increases for whites and declines for blacks due to desegregation occurred in regions closer to CBDs than did public enrollment responses.

Figure 5. Impacts of School Desegregation on Private School Enrollment.

Note: Each graphed line segment is a coefficient from a separate Poisson regression described in Equation (2) in the text. Samples include only the census tracts from 1960-1990 that fall within indicated distance intervals. The horizontal axis indicates location within central districts indexed as the cumulative distribution function of 1990 population with respect to CBD distance. Thickness of the lines show statistical significance. Thin lines are not statistically different from 0, medium thickness are significant at the 10% level and bold lines are significant at the 5% level. Standard errors are calculated based on 500 bootstrap replications sampling using MSA clusters with replacement. Table 1 Panel C presents sample attributes of the census tract data.

Figure 6 shows analogous results for total white and black populations. The results are similar to those in Figure 4. While white population significantly declines as a result of desegregation in all South central district locations, estimates are greatest in absolute value in the third and fourth segments at −.26 and −.33 respectively. Though as with public enrollment, the greatest white population response to desegregation outside the South is in the outer segment at minus 10 percent, it is not statistically significant. Consistent with estimated responses in black public enrollment, black population responses to five years of desegregation outside the South are largest in the third and fourth segments at around 0.15, though only the third segment’s estimate is precise. Of the sixteen race-region-segment combinations, none have estimated public enrollment declines as a result of school desegregation that are statistically different from the associated estimated population declines. Indeed, the magnitudes of point estimates for the two outcomes are remarkably similar.

Figure 6. Impacts of School Desegregation on Total Population.

Note: See the notes to Figures 4 and 5 for an explanation of the distance metric, sample and estimation method.

Although our spatial data permit analyzing some suburbs, we restrict our attention to central districts. Attempts to measure spatially disaggregated suburban responses to desegregation yield estimates that are sensitive to minor changes in specification or indexing scheme. Thin data in 1960 and 1970 and measurement error in tract assignment to suburban districts likely account for these unstable estimates. Furthermore, it is not clear what would be the most appropriate suburban tract indexing scheme.

IV. Conclusions

This paper provides new evidence on the mechanisms by which school desegregation in large urban districts led to public enrollment declines for whites and increases for blacks. We demonstrate that white enrollment declines primarily produced an outflow into suburban public schools. Outside of the South, private school attendance was also an important part of the white behavioral response to desegregation, while our white private school estimates for the South are too imprecise to draw any conclusions. Black public enrollment and population increases as results of desegregation did not occur until several years thereafter, primarily occurred outside of the South, and came primarily in the form of residential relocation into central districts.

Overall, our estimates indicate that while desegregation caused whites to exit the outer regions of central districts in large numbers, and induced a corresponding in-migration of blacks, school desegregation was not one of the main forces driving urban population decentralization because these two effects offset each other. To arrive at this conclusion, we take estimates from Table 3 Specification 1 and add back the number of white residents and public school students estimated to be lost from central districts in the South and other regions due to school desegregation. Similarly, we take estimates from Table 5 Specification 3 to subtract off the blacks that we estimate moved to central districts because of desegregation.

Even without court-ordered desegregation, our calculations indicate that aggregate central district white population would have fallen by 10 percent between 1960 and 1990 rather than the decline of 13 percent actually observed. These changes should be viewed relative to the 26 percent increase in white population nationwide during this period. Our estimates also indicate that aggregate central district black population would have increased by 44 percent rather than the 54 percent increase actually experienced in central districts. Put together, these changes imply a counterfactual increase in central district population of 12 percent relative to the 11 percent increase actually experienced. It is clear from these numbers that school desegregation was not a particularly important force in generating observed changes in overall urban residential location patterns over the past 50 years. We emphasize, however, that school desegregation was important in generating changes in the racial composition of central districts and also influenced patterns of private school attendance.

Supplementary Material

Table A1: Sample Districts and Attributes

Table A2: Impacts of Desegregation on Total Enrollment

Table A3: Impacts of Desegregation on MSA Level Outcomes

Figure A1: Fraction White by Residential Location Note: Graph shows the average ratio of residential white to white plus black population as a function of CBD distance across metropolitan areas in our sample for which census tract data are available. The sample includes the 64 metropolitan areas with central districts that were tracted in 1960 and experienced major desegregation orders. Metropolitan areas with fewer than 6 suburban tracts in any year are excluded. Each metropolitan area is weighted equally at all locations on the graph. The horizontal axis shows locations indexed as the cumulative distribution functions of 1990 population with respect to CBD distance inside and outside of central districts.

Figure A2: Income by Race and Residential Location Note: Graphs show median family or per capita income by race as a function of CBD distance across metropolitan areas. See the notes to Figure A1 for explanations of the sample, distance metric and weighting.

Acknowledgments

We thank Samuel Brown, Brian McGuire and Daniel Stenberg for excellent research assistance. We have benefitted from discussions at the Economic History Association Meetings, the North American Regional Science Council Meetings, the Lincoln Land Institute Urban Economics conference and in seminars at the University of Chicago, UCLA, UC Berkeley, Michigan State, Northwestern, Brown, McGill, Cornell, the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia and Clark University.

Data Appendix

Our sample is comprised of the 92 metropolitan areas (MSAs) with central school districts identified by Welch and Light (1987) as having a major court-ordered desegregation plan implemented between 1960 and 1990. We define central districts as those school districts that included the central business district of the largest census defined central city as of 1960 in each MSA nationwide. The sample includes all 56 central districts of over 50,000 students with minority enrollment between 20 and 80 percent in 1968 other than New York City, which did not have a major desegregation order. The remaining 36 central districts in our sample, which had enrollment over 15,000 and were between 10 and 90 percent minority in 1968, were randomly sampled with sampling weights proportional to enrollment and stratified by census region.

Welch and Light investigated desegregation histories of 33 additional districts that we do not use because they do not contain the central business district of a MSA. We merge this information on major plan implementation year with district level enrollment data from the Common Core of Data and the data set used by Welch and Light from the Office of Civil Rights. The enrollment data is used to calculate dissimilarity and exposure indices. Welch and Light (1987) report the year in which school desegregation was implemented for each school district. We observe only the year, not the month, of desegregation and must therefore make an assumption as to when in the year desegregation begins. Typically desegregation would have begun in the fall of the implementation year, meaning a desegregation plan implemented in 1970 would have taken force at the start of the 1970-1971 school year, though in some cases implementation may have begun earlier. In order to be conservative, we assume that desegregation begins at the start of the year. The census is mostly completed in late March with questions about school enrollment asking whether the individual has attended school at any time since February 1st. Therefore, implementations occurring in the same year as a census year would have had up to three months to have an effect on studied outcomes. In addition, outcomes may have been influenced by the announcement of impending desegregation. We choose this timing so as to capture the full potential response to desegregation. However, results are very similar if implementation is counted as taking hold beginning in the fall of the implementation year.