Abstract

Background

Metabolic bone disease and bariatric surgery have long been interconnected. The objective of this study is to better understand the mechanisms of bone mass loss after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) surgery. We evaluated mineral homeostasis and bone mass in diet-induced obese (DIO) rats after RYGB or sham surgery.

Methods

Twelve DIO male Sprague Dawley rats underwent RYGB (n = 8) or sham (n = 4) surgery at 21 weeks of age. Postoperatively, animals ate an ad libitum 40% fat, normal calcium diet and were euthanized 22 weeks later. Serum and urine chemistries, insulin, leptin, bone turnover markers (BTM), and calciotropic and gut hormones were measured before and 22 weeks after surgery. Femurs were analyzed using microcomputed tomography (µCT).

Results

Compared to sham, RYGB animals had lower serum bicarbonate, calcium, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, insulin, and leptin levels with higher serum parathyroid hormone, peptide YY, and urinary calcium at 43 weeks of age. Sham control rats gained weight and had coupled decreases in formation (P1 NP and OC) and unchanged resorption (CTX) BTMs. Comparatively, RYGB animals had higher serum CTX and OC but even lower P1 NP levels than controls. µCT revealed lower trabecular bone volume, number, and thickness and lower cortical bone volume, thickness, and moment of inertia relative to controls.

Conclusion

In rats with DIO, long-term RYGB-associated bone resorption appears to be driven in part by vitamin D malabsorption and secondary hyperparathyroidism. Other mechanisms, such as chronic acidosis, changes in fat-secreted hormones, and persistently elevated gut-derived hormone peptide YY, may also contribute to observed bone mass differences. Further investigation of these potential contributors to bone loss may lead to new targets for skeletal maintenance after RYGB.

Keywords: Morbid obesity, Gastric bypass surgery, Bone turnover markers, Bone resorption, Metabolic bone disease, Metabolic acidosis, Peptide YY

Obesity in the US is an overwhelming clinical problem, and most medical weight loss results are either temporary or completely ineffective. Bariatric surgery, in particular, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) has proven to be the only effective, long-term weight reduction treatment option curing diabetes and hypertension and lowering both cardiovascular and overall mortality [1,2]. These successes have led to a 6-fold increase in bariatric surgery over the last 10 years (36,700 procedures in 2000 rising to 220,000 procedures in 2009) with estimates that over 1.5 million Americans now have bypassed intestinal tracts [1,3]. Despite significant success in achieving weight management goals, RYGB surgery has been linked to abnormalities in mineral homeostasis and skeletal disease. For instance, 3 small prospective bone mineral density (BMD) studies in RYGB patients reported femoral neck, spine, and hip BMD losses of 7–10% from baseline within the first year of RYGB [4–6]. One recent population-based study found that bariatric surgery, >90% of which was RYGB, was associated with a 2.3-fold increased risk of fracture compared to an age- and sex-matched cohort [7].

Although several mechanisms have been suggested to account for these findings, clinical efforts to monitor BMD and lower fracture risk are limited because of lack of standardized supplementation regimens and high prevalence of baseline vitamin D deficiency in the morbidly obese [8]. Bariatric procedures in diet-induced obese (DIO) rats have shown similar weight loss patterns and neuropeptide changes as in humans, validating this model for investigating effects of RYGB on different systems [9,10]. We hypothesized that RYGB in DIO rats may provide insights into potential bone loss mechanisms and evaluated the long-term effect on bone mass as well as on mineral homeostasis, leptin, gut peptides, and acid/base status.

Materials and methods

Animals and surgical protocols

Protocols were approved by the University of Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee in accordance with guidelines established by the National Institutes of Health. Male Sprague Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) were housed in individual cages at a constant temperature of 21–23°C with a 12-hour light-dark cycle. To produce DIO, 3-week-old male pups were given ad lib access for 18 weeks to a 5.2 kcal/gm, 60% fat diet (D12492, Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ) containing .6% calcium, .6% phosphorus, and 1000 IU/kg of vitamin D3. Once DIO was established, rats were randomly assigned to RYGB (n = 8) or sham procedure (control, n = 4). RYGB was performed as previously described [11]. Briefly, a 4-mm enterotomy was made 35 cm proximal to the ileocecal valve (common channel). The bowel was transected 10 cm proximal to this point (Roux limb). An interrupted end-to-side hand-sewn anastomosis of the biliopancreatic limb (25–35 cm length) to the enterotomy was performed using polydioxanone suture. After sparing gastric artery and vagal nerves, a stapler (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Cincinnati, OH) was used to create a small stomach pouch. A 4-mm anterolateral gastrotomy was performed, and the gastrojejunostomy was hand sewn. Sham animals received similar incisions, stomach mobilization, operative time, and closure as RYGB animals.

Diet protocols and weight distribution

After the procedure, rats were allowed 2 weeks for return of bowel function and were then randomized to ad lib 40% fat diets without changing mineral or vitamin D content (D11021101, Research Diets) providing 4.6 kcal/gm. Weekly weights and daily food and water intake were recorded. Whole body adiposity was assessed with a Minispec lean fat analyzer (Bruker Optics, The Woodlands, TX) using previously validated time-domain nuclear magnetic resonance methodology [11].

Serum and urine collections

Twenty-four hour urine collections were obtained at baseline and every 5 weeks after surgery in metabolic cages for measurement of calcium and creatinine content [11]. Preoperative dorsal tail blood was collected after a 2-hour fast. At euthanasia, intracardiac blood was collected after 2-hour fast under isoflurane anesthesia. Blood was analyzed for calcium, chloride, sodium, potassium, and bicarbonate (total CO2) on an automated system (Dimension Xpand Clinical Chemistry Analyzer, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Inc., Indianapolis, IN). Anion gap was calculated by subtracting the serum concentrations of chloride and bicarbonate (anions) from the concentrations of sodium and potassium (cations). Serum was stored at −20°C until further use. Femurs were dissected free of excess tissue and placed in cooled 40% ethanol.

Serum 25(OH)D (DiaSorin, Stillwater, MN), rat intact parathyroid hormone (PTH; Alpco Diagnostics; Salem, NH), N-terminal pro peptide of type I procollagen (P1 NP) and carboxy-terminal cross-linked telopeptide of type 1 collagen (CTX) both from Immunodiagnostic Systems Ltd (Scottsdale, AZ) were measured with commercially available kits according to manufacturer instructions. Serum insulin, leptin, gastric inhibitory polypeptide, peptide YY, and pancreatic polypeptide were measured in duplicate using the Milliplex Rat Gut Hormone Panel (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) on the Luminex xMAP platform. Osteocalcin (OC) was measured by radioimmunoassay [12].

Microcomputed tomography analysis

Femurs in ethanol were scanned using a Scanco microCT-35 (Scanco Medical AG, Brutisellen, Switzerland) at 50 keV and 200 mA using a .5-mm aluminum filter with an isotropic voxel size of 10 µm connected to an HP Integrity 64-bit server running the Open Virtual Memory System.

Statistical analysis

To detect a 10–20% difference in bone mass, we estimated needing 4 control and 8 RYGB animals to establish effect at P < .01 with a power of 80%. Pre- and postoperative values for each measure were compared using paired Student t test or one-way ANOVA (Statistical Analysis Software Version 9.2; Cary, NC). P < .05 was accepted for significant differences. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

Results

Weight loss and fat distribution

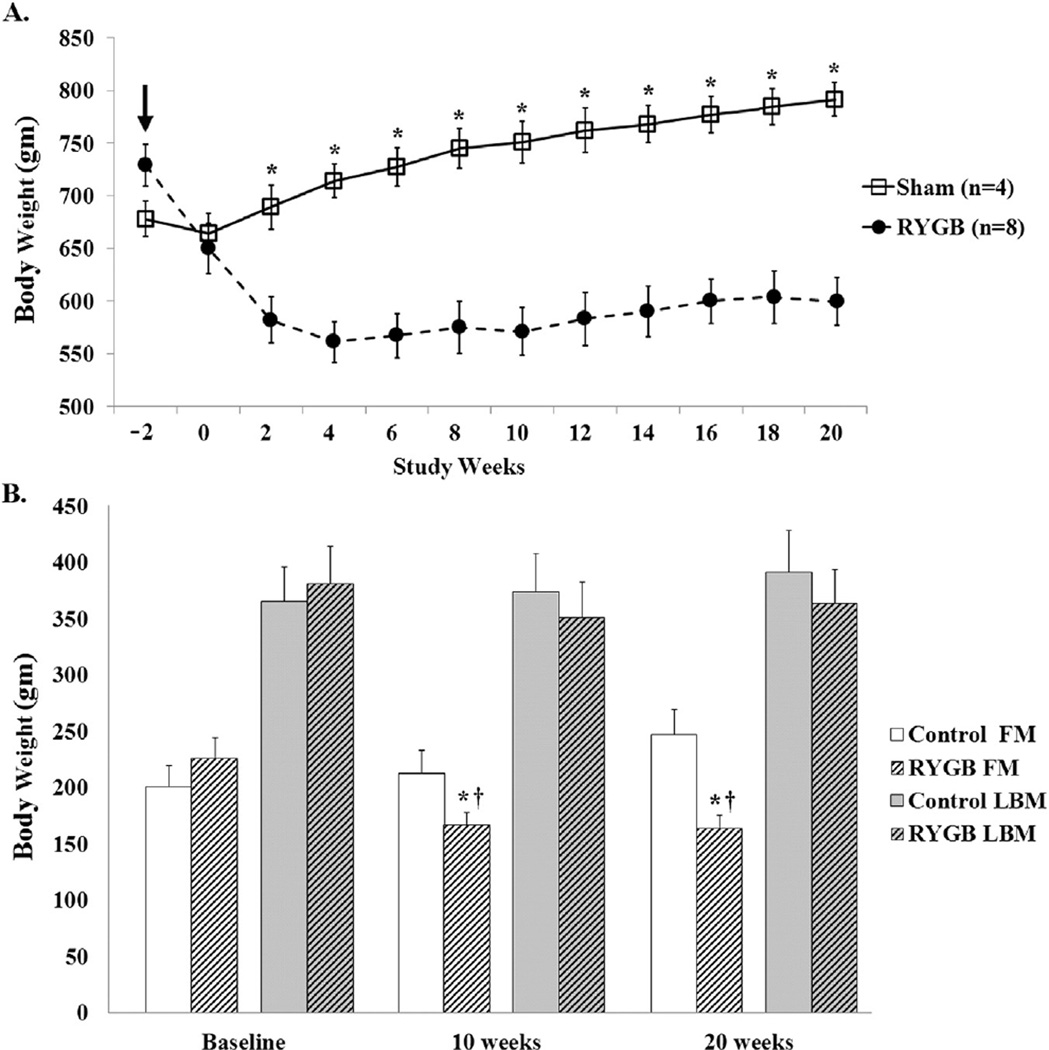

No differences were observed between DIO rats that received RYGB or sham operations in baseline weight (Fig. 1A), fat mass (FM), or lean body mass (LBM) (Fig. 1B). Significant differences in weight between groups were evident throughout postoperative time-point weeks 3–20 (Fig. 1A). Mean food intake for RYGB animals was similar to controls by postoperative week 7 (data not shown). At time-points 10 and 20 weeks after surgery, RYGB animals had lower total body FM loss compared to controls (Fig. 1B). LBM was slightly, but not significantly, lower at 10 and 20 weeks postoperatively in RYGB compared to control animals (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Total weight, FM, and LBM in obese male rats after RYGB surgery or sham control. (A) Control and RYGB animal weights plotted over time in weeks, starting on procedure day (arrow) with 2 weeks allotted for return of bowel function. Total weight became significantly different between control and RYGB animals 3 weeks after surgery. (B) LBM and FM were measured at baseline and time-point 10 and 20 weeks using nuclear magnetic resonance methodology. RYGB animals had significantly lower FM at 10 and 20 weeks after surgery compared to both baseline and control animals. Data shown as mean values ± SEM. *P < .05 between groups; †P < .05 within group.

Circulating measures of bone and mineral homeostasis

No differences were noted in baseline laboratory tests between RYGB and control rats (Table 1). Over the 22-week postoperative course, there were significant decreases in serum calcium, bicarbonate, and 25(OH)D in RYGB rats, producing mild hypocalcemia, acidosis, and vitamin D deficiency after surgery. Serum PTH rose significantly in both groups from baseline but was not significantly greater between controls or RYGB after surgery (Table 1). BTMs showed significant decreases in serum P1 NP, CTX, and OC in sham-operated rats (Table 1). After RYGB, serum P1 NP levels fell and were significantly lower than sham. In contrast, serum CTX and OC levels did not change in RYGB rats, remaining significantly greater (versus controls) for CTX but not OC at 44 weeks.

Table 1.

Baseline and 20 week postsurgery serum and urine laboratory values from sham control and RYGB rats

| Baseline (age 23 wk) | Postop (age 44 wk) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | RYGB | P value | Control | RYGB | P value | |

| Circulating measures of bone and mineral homeostasis | ||||||

| Serum Ca+ (mg/dL) | 10.8 ± .2 | 10.7 ± .1 | .46 | 10.4 ± .2 | 9.7 ± .2* | .008 |

| Serum CO2 (mmol/l) | 25.8 ± .7 | 26.5 ± .5 | .89 | 25.8 ± .7 | 21.4 ± 1.0 | .012 |

| Anion gap (meq/L) | 10.5 ± .3 | 10.3 ± .2 | .84 | 10.4 ± .2 | 15.1 ± .5* | .001 |

| PTH (pg/mL) | 208 ± 45 | 199 ± 19 | .41 | 336 ± 19 | 464 ± 48 | .08 |

| 25(OH)D (ng/mL) | 20.3 ± 1.1 | 22.3 ± 1.3 | .18 | 18.1 ± 3.7 | 8.9 ± 2.4* | .03 |

| P1 NP (ng/mL) | 3.40 ± .5 | 4.75 ± .5 | .07 | 1.38 ± .1* | 0.83 ± .2* | .04 |

| CTX (pg/mL) | 47.9 ± 16.5 | 57.6 ± 5.7 | .25 | 18.9 ± 2.8 | 58.1 ± 12.5 | .03 |

| OC (ng/mL) | 40.2 ± 3.1 | 39.4 ± 3.2 | .44 | 28.7 ± 3.4* | 37.6 ± 3.1 | .06 |

| Serum gastrointestinal and fat hormones | ||||||

| Insulin (pg/mL) | 442 ± 50 | 721 ± 148 | .22 | 1474 ± 339* | 173 ± 31* | <.001 |

| Leptin (ng/mL) | 14.2 ± 1.8 | 22.0 ± 3.7 | .19 | 10.5 ± 4.2 | 5.3 ± 1.9* | .21 |

| GIP (pg/mL) | 72.0 ± 3.3 | 72.4 ± 13.6 | .98 | 38.1 ± 3.4 | 34.4 ± 4.8 | .62 |

| Peptide YY (pg/mL) | 40.4 ± 3.8 | 41.3 ± 3.7 | .88 | 41.4 ± 6.6 | 97.5 ± 8.1* | .001 |

| PP (pg/mL) | 27.5 ± 3.9 | 24.0 ± 3.4 | .54 | 25.0 ± 2.7 | 15.1 ± 3.2 | .07 |

| Urinary calcium excretion | ||||||

| Urine calcium (mg/dL) | 6.8 ± .9 | 4.9 ± .6 | .32 | 5.5 ± .4 | 5.3 ± .6 | .89 |

| Ca/Cr | .115 | .094 | .37 | .085 | .126 | .19 |

25(OH)D = 25-hydroxy vitamin D; Ca/Cr = calcium to creatinine ratio; CTX = carboxy-terminal cross-linked telopeptide of type 1 collagen; GIP = gastric inhibitory polypeptide; OC = osteocalcin; P1 NP = N-terminal pro peptide of type I procollagen; PP = pancreatic polypeptide; PTH = parathyroid hormone.

Data presented as mean ± SEM. Bold, significant difference between control and RYGB (P value listed).

P ≤ .05 within groups (baseline versus postop).

Serum gastrointestinal and fat hormones

Over the 22 postoperative weeks, there were significant decreases in serum insulin in RYGB rats, whereas serum insulin markedly increased in controls (P < .001). Serum leptin decreased nonsignificantly (P = .21), and peptide YY increased (P = .001) in RYGB rats over this period, which was not seen in control animals. Thus, postsurgery RYGB rats had lower serum insulin and greater serum peptide YY levels than controls.

Urinary calcium

Compared to preoperative baseline samples, RYGB animals postsurgery had increased urinary calcium excretion at 5 weeks (15.7 ± 2.1 mg/dL versus 7.1 ± 1.2 mg/dL, P < .01) and 10 weeks (16.2 ± 1.7 mg/dL versus 6.7 ±.9 mg/dL, P < .01), but this was not sustained through week 15 (7. ± 1 .9 mg/dL versus 7.4 ± 1.3 mg/dL, P = .79) or week 20 (Table 1). In controls, urinary calcium excretion after surgery did not differ significantly from baseline samples.

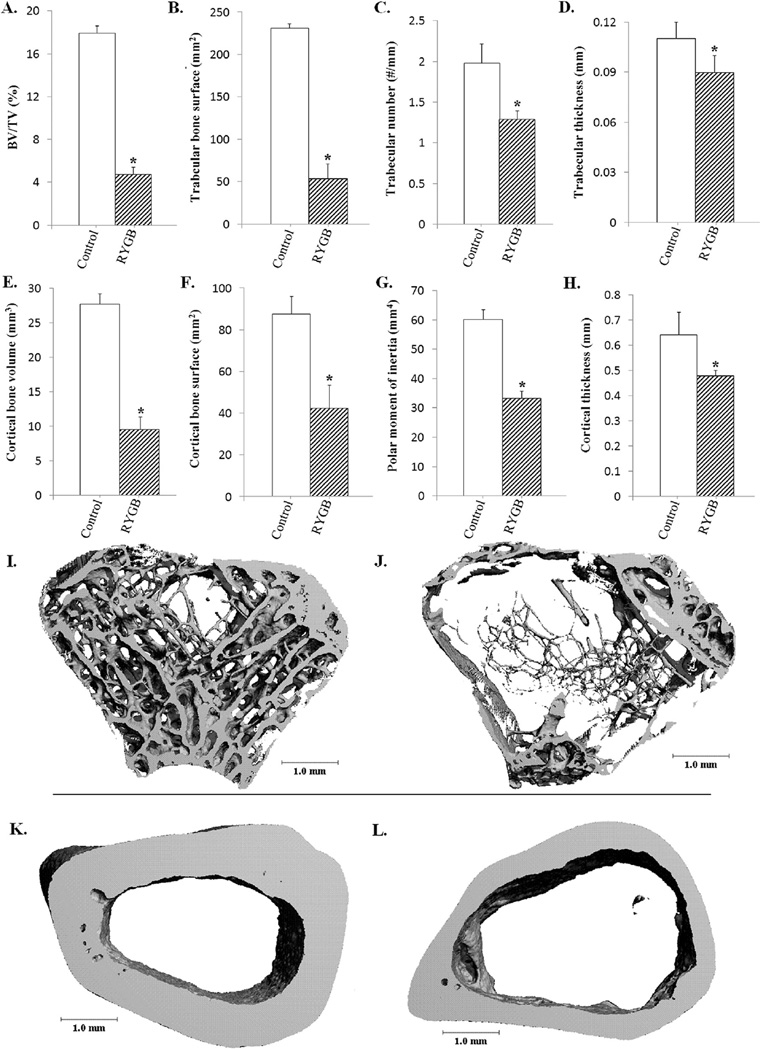

Microcomputed tomography

RYGB animals showed significantly lower trabecular bone volume/total volume, bone surface, trabecular number, and trabecular thickness than controls (Fig. 2, panels A–D, I, J). Cortical bone parameters in RYGB compared to control rats showed reduced bone volume, surface, polar moment of inertia, and thickness (Fig. 2, panels E–H, K, L). Additionally, RYGB animals had lower endosteal (14.4 ± .84 mm versus 18.2 ± 1.2 mm, P = .03) and periosteal circumferences (17.4 ± 1.2 mm versus 22.2 ± 1.7 mm, P = .005) compared to control rats (data not shown), suggesting that the reduction in cortical bone was related to diminished circumferential expansion, not simply due to increased endosteal resorption.

Figure 2.

RYGB leads to decreased bone mineral density compared to controls 20 weeks after surgery. Quantitative µCT (RYGB n = 4, control n = 2) demonstrated a significant decrease in bone volume/total volume in RYGB rats compared with controls (panel A; P < .001). In RYGB rats, trabecular bone surface (panel B, P = .001), number (panel C, P = .01), and thickness (panel D, P < .05) were all significantly decreased compared with age-matched, sham-control rats. Additionally, cortical BV (panel E; P = .002), bone surface (panel F; P = .03), polar moment of inertia (panel G; P = .001), and thickness (panel H, P = .03) were all lower in RYGB versus sham control rats. These differences are illustrated in µCT images of the trabecular (I, control; J, RYGB) and cortical (K, control; L, RYGB) compartments. *P < .05 between groups.

Discussion

RYGB surgery is the most common bariatric procedure performed in the US. Mechanisms leading to post-RYGB decreases in bone mass are poorly understood, but several have been proposed. First, voluntary weight loss of as little as 10% can alone produce 1–2% bone loss, due to mechanical unloading, and may be further compounded by reduced calcium intake during the ensuing dietary caloric restriction [13,14]. Second, malabsorption of calcium and fat-soluble vitamin D as well as decreased intestinal surface area can result in decreased intestinal calcium absorption, elevations in serum PTH (i.e., secondary hyperparathyroidism [sHPT]), and eventually increased skeletal calcium mobilization [15]. Not surprisingly, bariatric and endocrine professional societies have recommended universal supplementation to counter this calcium imbalance [16,17]. In support of these guidelines, 3 studies with 12–18 months follow-up in RYGB patients on higher than standard supplements (1500–2400 mg calcium and 1200–1600 IU vitamin D daily) demonstrated that serum PTH levels correct with adequate supplementation [6,18,19]. However, despite aggressive attention to sHPT prevention, the negative effect of RYGB on bone, reflected in changes in BTMs, were independent of 25(OH) D or PTH levels in all 3 studies [6,18,19]. Consequently, other factors unrelated to serum levels of calcium, vitamin D, or PTH may contribute to post-RYGB skeletal loss, including changes in fat mass, acid-base, and/or circulating hormones.

The DIO rat model allows us to study many of these factors because genetic background, gender, age, light exposure, and diet can be controlled. Our RYGB animals had greater weight and fat mass loss, lower 25(OH)D, and higher PTH levels, increased bone resorption (elevated CTX) and bone formation (higher OC) compared to sham controls —findings similar to reports in patients after RYGB [15,19–23]. Corresponding impressive loss of trabecular and cortical bone was noted by µCT, another finding similar to BMD changes seen in RYGB patients [6,18,19]. In these important respects, this model mimics mineral changes and bone loss seen after human RYGB. We noted a 50% increase in control serum PTH over time. PTH has been reported to increase as high as 5-fold in 18-month-old, ad libitum fed rats compared to their 6-week-old counterparts, presumably from age-related decline in renal function and gut calcium absorption [24]. Although mild age-related PTH elevations can also be seen in humans, it is usually not as dramatic nor does it occur in biphasic fashion as rodents [24].

Two other groups have published skeletal results in the RYGB rat model. Stemmer et al. [25] reported vitamin D deficiency and lower serum calcium but normal serum PTH in overweight male Long Evans rats 60 days after RYGB. Abegg et al. [26] also reported vitamin D deficiency but normal serum calcium and PTH levels in 450–500 gm male Wistar rats 14 weeks after RYGB. The sHPT we observed could be because of the older age of our rats (43 versus 24 wk), higher dietary fat content (40% fat versus 10% fat in the study by Abegg et al. [26]), and greater fat mass loss (210 gm versus 80 gm). Despite these differences, all 3 studies confirm persistently elevated markers of bone resorption and negative effects on BMD by µCT. Studies by us and Abegg et al.[26] found that OC, a noncollagenous protein produced by mature osteoblasts during mineralization and remodeling, remained elevated postoperatively with respect to controls. This is compatible with the high level of resorption marker (i.e., serum CTX) because it is expected that formation and resorption be coupled. However, P1 NP, a marker that directly reflects type 1 collagen synthesis (a necessary step in bone matrix synthesis), decreased in our rat model and that of Stemmer et al [25]. It is unclear why there is a difference between OC and P1 NP, since both are viewed as formation markers. Some investigators have suggested that OC fragments can be released during high turnover states [27], and such fragments may in fact reflect increased resorption rather than increased formation. Alternatively, lower P1 NP may reflect a lack of sufficient substrate to completely synthesize collagen or a true uncoupling of bone formation and resorption, which has been described in a 6-month study of 25 female patients before and after RYGB [28]. Further efforts are needed to determine whether this BTM variability is biological or technical in origin.

Previously, we showed that RYGB rats have lower urine pH and higher urine calcium postoperatively versus controls [11] and now describe low serum bicarbonate with anion gap acidosis 22 weeks postoperatively. Abegg et al. [26] also noted mild elevations in serum lactate levels and anion gap metabolic acidosis by venous blood gas as a potential cause of persistent hypercalciuria in their RYGB model. Both of these studies suggest that chronic metabolic acidosis could play a larger role in bone disease than previously expected after this procedure.

This is the first longitudinal description of insulin, leptin, and gut-derived hormones in association with bone parameters after RYGB. Insulin is necessary to maintain normal bone mass [29]. Although comparative studies between RYGB and other restrictive bariatric procedures have failed to show differences between bone loss and acute insulin signaling, chronic insulin changes may play a role in bone remodeling [26]. Leptin, a fat-secreted hormone, has complex effects, but its decline after human RYGB correlates closely with the decline in BMD [18]. Our model fits with human data, where BMD decreases commensurately with serum leptin levels. Lastly, peptide YY, a gut-derived, satiety hormone produced by the lower GI tract, is increased postprandially after RYGB surgery and associated with bone loss in a variety of studies in adolescents [30,31]. Conflicting findings in knockout mice on the exact role of this hormone in bone metabolism imply that further investigation of peptide YY and bone loss after RYGB is needed [32].

This study has several limitations. (1) Due to the consequences of gastric bypass, serum albumin levels, not measured in this study, may have decreased and affected proper interpretation of total calcium. (2) Multiple comparisons and small experimental numbers limit study power. (3) Although the diet of the typical RYGB patient has been estimated to contain up to 37% fat, standard rat chow ranges from 10–14% fat, so high dietary fat intake likely compounds the effects of fat malabsorption. (4) Pair-feeding was not done, so differences in caloric intake between groups may have affected results. Food intake in sham controls exceeded that of RYGB until 7 weeks after surgery (when food intake became similar). (5) The differences in peptide YY, insulin, and PTH between groups do not confirm a causal relationship to the observed bone loss.

Conclusion

Our data in a DIO model post-RYGB suggest that bone loss occurs through several mechanisms: vitamin D and calcium malabsorption, acid/base dysregulation, and effects on adipose- and gut-derived hormones. In addition to augmented bone resorption, our data raise the possibility of suppression of bone formation after RYGB. These abnormalities may represent future targets for bone loss prevention strategies in humans undergoing RYGB and deserve further research.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by NIH K08 DK089000-04, P30-AR46032, R03 DK100732-01, AUA Foundation Rising Star in Urology Research Award in conjunction with Astellas Global Development, Inc., Veterans Affairs Grant IK2 CX000549-03, and Ethicon Endo-Surgery.

References

- 1.Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;292:1724–1737. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.14.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sjostrom L, Narbro K, Sjostrom CD, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:741–752. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blackburn GL. The 2008 Edward E. Mason Founders lecture: interdisciplinary teams in the development of "best practice" obesity surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4:679–684. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coates PS, Fernstrom JD, Fernstrom MH, Schauer PR, Greenspan SL. Gastric bypass surgery for morbid obesity leads to an increase in bone turnover and a decrease in bone mass. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:1061–1065. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carrasco F, Ruz M, Rojas P, et al. Changes in bone mineral density, body composition and adiponectin levels in morbidly obese patients after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2009;19:41–46. doi: 10.1007/s11695-008-9638-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fleischer J, Stein EM, Bessler M, et al. The decline in hip bone density after gastric bypass surgery is associated with extent of weight loss. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:3735–3740. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakamura KM, Haglind EG, Clowes JA, et al. Fracture risk following bariatric surgery: a population-based study. Osteoporos Int. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s00198-013-2463-x. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ernst B, Thurnheer M, Schmid SM, Schultes B. Evidence for the necessity to systematically assess micronutrient status prior to bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2009;19:66–73. doi: 10.1007/s11695-008-9545-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bueter M, Ashrafian H, Frankel AH, Tam FW, Unwin RJ, le Roux CW. Sodium and water handling after gastric bypass surgery in a rat model. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2011;7:68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2010.03.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stylopoulos N, Hoppin AG, Kaplan LM. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass enhances energy expenditure and extends lifespan in diet-induced obese rats. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17:1839–1847. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canales BK, Ellen J, Khan SR, Hatch M. Steatorrhea and hyperoxaluria occur after gastric bypass surgery in obese rats regardless of dietary fat or oxalate. J Urol. 2013;190:1102–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.02.3229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gundberg CM, Hauschka PV, Lian JB, Gallop PM. Osteocalcin: isolation, characterization, and detection. Methods Enzymol. 1984;107:516–544. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(84)07036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salamone LM, Cauley JA, Black DM, et al. Effect of a lifestyle intervention on bone mineral density in premenopausal women: a randomized trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70:97–103. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/70.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uusi-Rasi K, Sievanen H, Kannus P, Pasanen M, Kukkonen-Harjula K, Fogelholm M. Influence of weight reduction on muscle performance and bone mass, structure and metabolism in obese premenopausal women. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2009;9:72–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson JM, Maher JW, Samuel I, Heitshusen D, Doherty C, Downs RW. Effects of gastric bypass procedures on bone mineral density, calcium, parathyroid hormone, and vitamin D. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9:1106–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2005.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heber D, Greenway FL, Kaplan LM, Livingston E, Salvador J, Still C. Endocrine and nutritional management of the post-bariatric surgery patient: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:4823–4843. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mechanick JI, Kushner RF, Sugerman HJ, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, The Obesity Society, and American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery medical guidelines for clinical practice for the perioperative nutritional, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of the bariatric surgery patient. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17(Suppl 1):S1–S70. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bruno C, Fulford AD, Potts JR, et al. Serum markers of bone turnover are increased at six and 18 months after Roux-en-Y bariatric surgery: correlation with the reduction in leptin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:159–166. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sinha N, Shieh A, Stein EM, et al. Increased PTH and 1.25(OH)(2)D levels associated with increased markers of bone turnover following bariatric surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19:2388–2393. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clements RH, Yellumahanthi K, Wesley M, Ballem N, Bland KI. Hyperparathyroidism and vitamin D deficiency after laparoscopic gastric bypass. Am Surg. 2008;74:469–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ott MT, Fanti P, Malluche HH, et al. Biochemical evidence of metabolic bone disease in women following Roux-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Obes Surg. 1992;2:341–348. doi: 10.1381/096089292765559936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wucher H, Ciangura C, Poitou C, Czernichow S. Effects of weight loss on bone status after bariatric surgery: association between adipokines and bone markers. Obes Surg. 2008;18:58–65. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9258-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gomez JM, Vilarrasa N, Masdevall C, et al. Regulation of bone mineral density in morbidly obese women: a cross-sectional study in two cohorts before and after bypass surgery. Obes Surg. 2009;19:345–350. doi: 10.1007/s11695-008-9529-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalu DN, Hardin RH, Cockerham R, Yu BP. Aging and dietary modulation of rat skeleton and parathyroid hormone. Endocrinology. 1984;115:1239–1247. doi: 10.1210/endo-115-4-1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stemmer K, Bielohuby M, Grayson BE, et al. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery but not vertical sleeve gastrectomy decreases bone mass in male rats. Endocrinology. 2013;154:2015–2024. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-2130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abegg K, Gehring N, Wagner CA, et al. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery reduces bone mineral density and induces metabolic acidosis in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2013;305:R999–1009. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00038.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seibel MJ. Biochemical markers of bone turnover: part I: biochemistry and variability. Clin Biochem Rev. 2005;26:97–122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Riedt CS, Brolin RE, Sherrell RM, Field MP, Shapses SA. True fractional calcium absorption is decreased after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:1940–1948. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fulzele K, Riddle RC, DiGirolamo DJ, et al. Insulin receptor signaling in osteoblasts regulates postnatal bone acquisition and body composition. Cell. 2010;142:309–319. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Valderas JP, Irribarra V, Boza C, et al. Medical and surgical treatments for obesity have opposite effects on peptide YY and appetite: a prospective study controlled for weight loss. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:1069–1075. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Russell M, Stark J, Nayak S, et al. Peptide YY in adolescent athletes with amenorrhea, eumenorrheic athletes and non-athletic controls. Bone. 2009;45:104–109. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.03.668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wong IP, Driessler F, Khor EC, et al. Peptide YY regulates bone remodeling in mice: a link between gut and skeletal biology. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40038. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040038. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0040038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]