Abstract

Background

Although dietary supplements are commonly taken to avoid chronic disease, long-term health consequences of many compounds are unknown.

Methods

We assessed the use of vitamin and mineral supplements in relation to total mortality in 38 772 older women in the Iowa Women's Health Study, mean age 61.6 years at baseline in 1986. Supplement use was self-reported in 1986, 1997 and 2004. Through December 31, 2008, 15 594 deaths (40.2%) were identified through the State Health Registry of Iowa and the National Death Index.

Results

In multivariable adjusted proportional hazards regression models, the use of multivitamins (Hazard Ratio (HR), 1.06 [95% CI, 1.02-1.10], Absolute Risk Increase (ARI), 2.4%), vitamin B6 (HR, 1.10 [95% CI, 1.01-1.21], ARI, 4.1%), folic acid (HR, 1.15 [95% CI, 1.00-1.32], ARI, 5.9%), iron (HR, 1.10 [95% CI, 1.03-1.17], ARI, 3.9%), magnesium (HR, 1.08 [95% CI, 1.01-1.15], ARI, 3.6%), zinc (HR, 1.08 [95% CI, 1.01-1.15], ARI, 3.0%) and copper (HR, 1.45 [95% CI, 1.20-1.75], ARI, 18.0%) were associated with increased risk of total mortality when compared with corresponding nonusers, while calcium was inversely related (HR, 0.91 [95% CI, 0.88-0.94], Absolute Risk Reduction (ARR), 3.8%). Findings for iron and calcium were replicated in separate shorter-term analyses (10-year, 6-year and 4-year follow-up) each with about 15% dead, starting in 1986, 1997, and 2004.

Conclusion

In older women several commonly used dietary vitamin and mineral supplements may be associated with increased total mortality risk, most strongly supplemental iron, while calcium, in contrast to many studies, was associated with decreased risk.

Keywords: Cohort, Iowa Women's Health study, minerals, supplement, total mortality, vitamins, women

Introduction

In the United States the use of dietary supplements has increased substantially over the past several decades1,2,3, reaching approximately one-half of adults in 2000 and annual sales of over $20 billion.1,3 We reported that 66% of women participating in the Iowa Women's Health Study (IWHS) used at least one dietary supplement daily in 1986 at average age 62 years, while in 2004, the proportion increased to 85%.2 Moreover, 27% of women reported using four or more supplemental products in 2004.2 At the population level, dietary supplements contributed substantially to the total intake of several nutrients, particularly in the elderly.1, 2

Supplemental nutrient intake is clearly of benefit in the face of deficiency conditions.4 However, in well-nourished populations, supplements are often intended to attain benefit against chronic diseases. Epidemiological studies assessing supplement use and total mortality risk have been inconsistent.5-9 Several randomized clinical trials (RCT), concentrating mainly on calcium, vitamins B, C, D, and E, have not shown beneficial effects of dietary supplements on total mortality10,11, and, in contrast, some have suggested possibility of harm.12,13 Meta-analyses concur in finding no decreased risk and potential harm.14,15 Supplements are widely used and further studies about their health effects are needed. Also, little is known about the long-term effects of multivitamin use and less commonly used supplements such as iron and other minerals.

The aim of the present study was to assess the relation between supplement use and total mortality in older women of the IWHS. Our hypothesis2 was that the use of dietary supplements would not be associated with reduced rate of total mortality.

Methods

The IWHS was designed to examine associations between several host, dietary, and lifestyle factors and the incidence of cancer in postmenopausal women.16 At the study baseline in 1986, 41 836 women aged 55–69 years completed a 16-page self-administered questionnaire. Of these women, 99% were white and 99% postmenopausal. Respondents were slightly younger, had lower body mass index (BMI, weight/height 2) and more likely live in rural areas than non-respondents.17 IWHS was approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board, and return of the questionnaire was considered informed consent, concordant with prevailing practice in 1986.

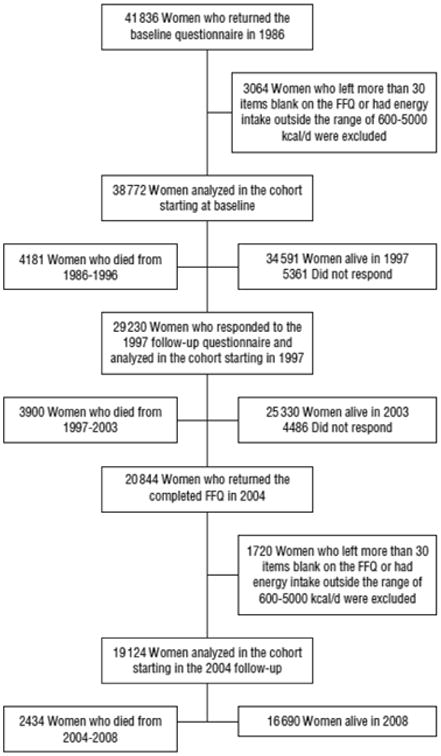

We included 38 772 women, excluding from all analyses those who did not adequately complete a questionnaire including food frequency and supplement use at baseline in 1986.2 For the analyses starting in 1997, 29 230 women who filled out the supplement use questionnaire (diet data were not assessed) were included. Starting analysis in 2004, 19 124 women were included. Study flow is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Description of the Iowa Women's Health Study.

Supplement Use and dietary information

Food intake was assessed at baseline and in 2004 follow-up using two nearly identical versions of the validated 127-food-item Harvard food frequency questionnaire (FFQ).18,19 Food-composition values were obtained from the Harvard University Food Composition Database derived from US Department of Agriculture sources, supplemented with manufacturer information, and updated to reflect marketplace changes.

Supplement use was queried in 1986, 1997, and 2004, and included the 15 supplements assessed at all three surveys; multivitamins, vitamins A, beta-carotene, B6, folic acid, B-complex, C, D, E, minerals iron, calcium, copper, magnesium, selenium, and zinc. Different forms of vitamin D, cholecalciferol (D3) or ergocalciferol (D2), were not distinguished. At the baseline and 2004 follow-up surveys, the supplement related questions were a part of the FFQ. In the 1997 follow-up survey the supplement questions were asked without querying diet. Dose was assessed for vitamins A, B6, C, D, E, calcium, iron, selenium, and zinc with five supplement-specific response options, uniformly across three surveys except that no dose information was collected for vitamin B6 at baseline or for vitamin D in 2004.

Although the dietary supplement part of the FFQ used in the study was not separately validated19, evaluations with similar instruments have reported validity correlations ∼0.8.20

Ascertainment and classification of mortality

Deaths through December 31, 2008 were identified annually through the State Health Registry of Iowa or National Death Index for subjects who did not respond to the follow-up questionnaires or who had emigrated from Iowa. Underlying cause of death was assigned by state vital registries via the International Classification of Disease (ICD). We defined 1) all cardiovascular disease (CVD) by ICD-9 codes 390-459 or ICD-10 codes I00-I99, 2) cancer by codes 140-239 or C00-D48, 3) “other cause of death” for all other deaths, excluding 231 injury, accident and suicide deaths as it is unlikely that supplement use would be causally related to these outcomes. Follow-up duration was calculated as the time from the baseline date to the date of death, or to the earlier of the last follow-up contact or 31 December 2008.

Other Measurements

The baseline questionnaire included questions concerning potential confounders, including age, height, education, place of residence (live on a farm/rural area other than farm/city), diabetes, high blood pressure, weight, hormone replacement therapy, physical activity, and smoking. As previously described,2 physical activity was characterized as participating in moderate or vigorous activities < a few times a month, a few times a month/once a week, or ≥2 times a week. Waist and hip circumferences were measured by each participant using a fixed protocol.20

The 1986 and 2004 questionnaires included the same questions and in a similar form, except that education, place of residence, waist and hip circumferences were not re-assessed. The 1997 questionnaire included in common with the 1986 and 2004 questionnaires only questions regarding diabetes, weight, high blood pressure, hormone replacement therapy and smoking. Neither blood lipids nor blood pressure were measured at any survey.

Statistical analyses

Analyses were performed using PC-SAS, version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, US). Continuous variables were compared using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and categorical variables using chi-square tests. Cumulative mortality rates by supplement use were examined. Absolute risk increase (ARI) and reduction (ARR) were calculated by multiplying the absolute risk in the reference group by the multivariable-adjusted hazard ratio change in the comparison group. Cox proportional hazards regression analyses were used to explore the relation between supplement use and outcomes. In the minimally adjusted model, we adjusted the association for age and energy intake, while in the multivariable model 2 we additionally adjusted for education, place of residence, diabetes, high blood pressure, body mass index, waist-hip-ratio, hormone replacement therapy, physical activity, and smoking. For model 3 we added alcohol, saturated fatty acid (SAFA), whole grain product, fruit and vegetable intake.

Additional analyses were performed over shorter follow-up interval in each of which about 15% of deaths occurred: from 1986 until the end of 1996, from 1997 until the end of 2003, and from 2004 until the end of 2008. Data including supplement use from the corresponding interval questionnaire were used whenever available. Covariate adjustment was as above. For analyses starting in 1997 current covariate data were available for diabetes, high blood pressure, BMI, hormone replacement therapy, and smoking while for analyses starting in 2004 current data were available for all covariates except education, place of residence and waist-hip-ratio. When current data were unavailable, 1986 information was used.

Results

Among the 38 772 women aged 61.6±4.2 followed from the 1986 questionnaire data, 15 594 deaths accrued (40.2%) during the mean follow-up time of 19.0 years. Mean BMI was 27.0±5.1 kg/m2 and 36.8% reported high blood pressure, 6.8% diabetes and 15.1% current smoking. At baseline, the supplement users were more likely to be non-diabetic, have lower BMI and waist-to-hip ratio, to be nonsmoking, more educated, physically more active, and to use estrogen replacement therapy, and were less likely to live on a farm and have high blood pressure compared to nonusers (Table 1). In addition, supplement users were more likely to have lower intakes of energy, total fat and SAFA, and have higher intakes of protein, carbohydrates, monounsaturated fatty acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids, alcohol, whole grain foods, fruits and vegetables. Similar patterns were seen in the 2004 questionnaire among 19 124 women (Table 1) and for individual supplements, e.g. supplemental iron and calcium (eTable 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of women who responded to questionnaires in 1986 (n = 38 772) and in 2004 (n = 19 124), according to use of any of 15 supplements at the time of the given questionnaire: the Iowa Women's Health Study.

| Characteristic | Baseline, 1986 | Follow-up, 2004 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supplement users (n =24 329) |

Supplement nonusers (n =14 443) |

P1 | Supplement users (n = 16 278) |

Supplement nonusers (n =2846) |

P1 | |

| Age (y) | 61.6 ± 4.2 | 61.5 ± 4.2 | .11 | 82.3 ± 3.9 | 82.6 ± 4.0 | .004 |

| Current smoker (%) | 14.0 | 17.1 | <.001 | 3.3 | 4.8 | <.001 |

| Live on a farm (%)2 | 18.1 | 21.0 | <.001 | 21.1 | 21.7 | .46 |

| Current hormone replacement therapy (%) | 13.5 | 7.2 | <.001 | 9.7 | 4.8 | <.001 |

| Education (%)2 | <.001 | <.001 | ||||

| 1-8 years | 7.4 | 9.2 | 6.0 | 9.4 | ||

| 9-12 years | 9.5 | 11.0 | 7.5 | 9.8 | ||

| High school graduate | 41.0 | 43.9 | 41.3 | 43.4 | ||

| Beyond high school | 42.1 | 36.0 | 45.2 | 37.5 | ||

| High blood pressure (%) | 35.7 | 38.6 | <.001 | 43.7 | 43.9 | .85 |

| Diabetes (%) | 6.0 | 8.2 | <.001 | 8.6 | 12.0 | <.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2)3 | 26.9 ± 4.9 | 27.5 ± 5.3 | <.001 | 26.6 ±4.7 | 27.6 ±5.1 | <.001 |

| Waist-to-hip ratio2 | 0.83 ± 0.08 | 0.85 ± 0.09 | <.001 | 0.82 ±0.08 | 0.84 ±0.08 | <.001 |

| Physical activity index | <.001 | <.001 | ||||

| < a few times a month | 17.9 | 25.5 | 26.3 | 40.1 | ||

| a few times a month or once a week | 26.6 | 29.5 | 18.8 | 19.1 | ||

| 2 or more times a week | 55.5 | 45.1 | 55.0 | 40.7 | ||

| Diet | ||||||

| Energy intake (kcal/d) | 1784 ± 579 | 1883 ± 624 | <001 | 1942 ± 708 | 1925 ± 747 | .23 |

| Protein (E%) | 18.1 ±3.2 | 17.9 ±3.2 | <001 | 17.9 ±3.4 | 17.5 ±3.3 | <.001 |

| Carbohydrates (E%) | 49.1 ±7.7 | 48.2 ±7.7 | <001 | 49.9 ±8.3 | 49.5 ±8.2 | .018 |

| Total fat (E%) | 33.6 ±5.8 | 34.6 ±5.7 | <001 | 33.9 ±6.4 | 34.9 ±6.5 | <.001 |

| SAFA (E%) | 11.7 ±2.5 | 12.2 ±2.6 | <001 | 11.6 ±2.6 | 12.0 ±2.7 | <.001 |

| MUFA (E%) | 12.7 ±2.5 | 13.2 ±2.5 | <001 | 12.8 ±2.7 | 13.1 ±2.8 | <.001 |

| PUFA (E%) | 6.1 ±1.6 | 6.0 ±1.6 | <001 | 6.0 ±1.6 | 5.9 ±1.5 | .32 |

| Alcohol (g/d) | 3.9 ±8.9 | 3.6 ±8.9 | .004 | 2.3 ±6.4 | 1.7 ±5.9 | <.001 |

| Fruits (serv/d) | 2.7 ±1.6 | 2.5 ±1.6 | <001 | 3.1 ±2.1 | 2.8 ±2.0 | <.001 |

| Vegetables (serv/d) | 3.7 ±2.2 | 3.6 ±2.1 | <001 | 3.5 ±2.3 | 3.3 ±2.4 | <.001 |

| Whole grain (serv/d) | 1.7 ±1.3 | 1.5 ±1.2 | <001 | 1.7 ±1.3 | 1.4 ±1.2 | <.001 |

P-value from t tests for continuous variables or from chi-square test for categorical variables.

Baseline values

Body mass index (BMI) was computed as the ratio of weight in kilograms to the square of heightin meters (kg/m2).

Self-reported use of dietary supplements increased substantially between 1986 and 2004. 2 In 1986, 1997, and 2004, 62.7%, 75.1%, and 85.1% of the women, respectively, reported using at least one supplement daily. The most commonly used supplements were calcium, multivitamins, vitamin C and E (eTable 2) and supplement combinations were calcium and multivitamins, calcium, multivitamins and vitamin C, and calcium and vitamin C.

At baseline, in Cox proportional hazards models with full follow-up time and adjusted for age and energy intake, self-reported use of vitamin B-complex, vitamins C, D, and E, and calcium had significantly lower risk of total mortality when compared to nonusers, while copper was associated with a higher risk (Table 2). With further adjustment (Model 2) only the use of calcium retained significantly lower risk of mortality (HR, 0.92, ARR, 3.5%), while the other inverse associations were attenuated to non-significance. In contrast, further adjustment for non-nutritional factors strengthened several associations to significance that had HR >1 in the minimal model: multivitamins (HR, 1.06, ARI, 2.2%), B6 vitamin (HR, 1.09, ARI, 3.5%), folic acid (HR, 1.12], ARI, 4.8%), copper (HR, 1.42, ARI, 16.8%), iron (HR, 1.09, ARI, 3.8%), magnesium (HR, 1.08, ARI, 3.4%), and zinc (HR, 1.05, ARI, 2.1%). Further adjustment for nutritional factors (Model 3) affected the associations only slightly: multivitamins (HR, 1.06, ARI, 2.4%), B6 vitamin (HR, 1.10, ARI, 4.1%), folic acid (HR, 1.15], ARI, 5.9%), calcium (HR, 0.91, ARR, 3.8%), copper (HR, 1.45, ARI, 18.0%), iron (HR, 1.10, ARI, 3.9%), magnesium (HR, 1.08, ARI, 3.6%), and zinc (HR, 1.08, ARI, 3.0%).

Table 2.

Adjusted hazard ratios (95% CI) for the use of supplements and risk of total mortality women aged 55-69 at baseline, Iowa Women's Health Study. 1

| Users | Non-users | Age and energy adjusted | Multivariable adjusted2 | Multivariable adjusted3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cases/total | cases/total | HR | (95% CI) | HR | (95% CI) | HR | (95% CI) | |

| Multivitamin | 5218/12 769 | 10 161/25 474 | 1.02 | (0.99-1.05) | 1.06 | (1.02-1.09)* | 1.06 | (1.02-1.10)* |

| Vitamin A | 1159/2843 | 13 694/34 263 | 0.99 | (0.93-1.05) | 1.05 | (0.98-1.11) | 1.06 | (0.99-1.13) |

| Beta-carotene | 149/378 | 15 445/38 394 | 1.00 | (0.85-1.17) | 1.07 | (0.91-1.26) | 1.10 | (0.93-1.30) |

| Vitamin B6 | 530/1269 | 15 064/37 503 | 1.04 | (0.95-1.13) | 1.09 | (1.00-1.19) | 1.10 | (1.01-1.21) |

| Folic acid | 220/509 | 15 374/38 263 | 1.09 | (0.95-1.24) | 1.12 | (0.98-1.29) | 1.15 | (1.00-1.32) |

| Vitamin B-complex | 1199/3174 | 14 395/35 598 | 0.93 | (0.87-0.98) | 0.99 | (0.93-1.05) | 1.00 | (0.94-1.06) |

| Vitamin C | 4293/10 905 | 10 812/26 806 | 0.96 | (0.93-0.99) | 1.01 | (0.97-1.05) | 1.01 | (0.97-1.05) |

| Vitamin D | 1575/4082 | 13 327/33 105 | 0.92 | (0.87-0.96)* | 1.00 | (0.95-1.05) | 1.00 | (0.95-1.06) |

| Vitamin E | 2125/5403 | 12 771/31 177 | 0.94 | (0.90-0.99) | 1.00 | (0.95-1.05) | 1.01 | (0.96-1.05) |

| Calcium | 6454/17 428 | 8847/20 735 | 0.83 | (0.80-0.85)* | 0.92 | (0.89-0.95)* | 0.91 | (0.88-0.94)* |

| Copper | 108/229 | 15 486/38 543 | 1.31 | (1.08-1.58)* | 1.42 | (1.17-1.72)* | 1.45 | (1.20-1.75)* |

| Iron | 1117/2738 | 13 801/34 443 | 1.03 | (0.97-1.09) | 1.09 | (1.03-1.17) | 1.10 | (1.03-1.17) |

| Magnesium | 568/1410 | 15 026/37 362 | 0.97 | (0.91-1.03) | 1.08 | (0.99-1.18) | 1.08 | (1.01-1.15) |

| Selenium | 490/1251 | 14 328/35 788 | 0.97 | (0.89-1.06) | 1.07 | (0.97-1.17) | 1.09 | (0.99-1.19) |

| Zinc | 1064/2635 | 13 790/34 398 | 0.97 | (0.91-1.03) | 1.05 | (0.99-1.12) | 1.08 | (1.01-1.15) |

Note: 15 594 deaths in 38 772 women at risk; numbers differ due to missing information for specific supplements.

P<0.0033 (the p-value which meets the Bonferroni criterion for 15 tests, with overall significance level = 0.05).

Adjusted for age, education, place of residence, diabetes, high blood pressure, body mass index, waist-hip-ratio, hormone replacement therapy, physical activity, smoking, intake of energy.

Adjusted for age, education, place of residence, diabetes, high blood pressure, body mass index, waist-hip-ratio, hormone replacement therapy, physical activity, smoking, intakes of energy, alcohol, saturated fatty acids, whole grain products, fruits and vegetables.

In sensitivity analyses excluding those who had CVD or diabetes (n = 5772) or cancer (n = 3523) at baseline the results were not materially changed. For example, for iron the multivariable adjusted HR for total mortality was 1.13 (95% CI, 1.05-1.22). As for total mortality, most supplements were unrelated to or showed higher cause-specific mortality, although risk patterns varied across causes (Table 3).

Table 3.

Adjusted hazard ratios (95% CI) for the use of supplements and risk of disease specific mortality women aged 55-69 at baseline, Iowa Women's Health Study.

| CVD MORTALITY | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Users | Non-users | Age and energy adjusted | Multivariable adjusted | |||

| Supplement | cases/total | cases/total | HR | (95% CI) | HR | (95% CI) |

| Multivitamin | 1864/12 769 | 3782/25 475 | 0.98 | (0.92-1.03) | 1.03 | (0.97-1.09) |

| A-vitamin | 406/2843 | 5027/34 263 | 0.94 | (0.85-1.04) | 1.02 | (0.92-1.13) |

| Beta-carotene | 54/378 | 5667/38 394 | 0.99 | (0.76-1.29) | 1.14 | (0.87-1.50) |

| B6-vitamin | 189/1269 | 5532/37 503 | 1.01 | (0.87-1.16) | 1.07 | (0.92-1.24) |

| Folic acid | 85/509 | 5636/38 263 | 1.14 | (0.92-1.41) | 1.24 | (0.99-1.54) |

| B-complex | 405/3174 | 5316/35 598 | 0.85 | (0.77-0.94) | 0.91 | (0.82-1.01) |

| C-vitamin | 1518/10 905 | 4017/26 806 | 0.91 | (0.86-0.97) | 0.98 | (0.92-1.04) |

| D-vitamin | 577/4082 | 4890/33 105 | 0.90 | (0.83-0.98) | 0.99 | (0.91-1.09) |

| E-vitamin | 771/5403 | 4678/31 774 | 0.93 | (0.86-1.00) | 1.00 | (0.92-1.08) |

| Calcium | 2282/17 428 | 3319/20 735 | 0.78 | (0.74-0.82) | 0.87 | (0.82-0.92) |

| Copper | 39/229 | 5682/38 543 | 1.32 | (0.96-1.81) | 1.50 | (1.09-2.06) |

| Iron | 410/2738 | 5069/34 443 | 1.02 | (0.92-1.13) | 1.11 | (1.00-1.23) |

| Magnesium | 226/1410 | 5495/37 362 | 1.08 | (0.94-1.23) | 1.16 | (1.01-1.34) |

| Selenium | 171/1251 | 5249/35 788 | 0.93 | (0.79-1.08) | 1.03 | (0.88-1.20) |

| Zinc | 373/2635 | 5081/34 398 | 0.91 | (0.82-1.01) | 1.03 | (0.92-1.14) |

| CANCER MORTALITY: | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Users | Non-users | Age and energy adjusted | Multivariable adjusted | |||

| Supplement | cases/total | cases/total | HR | (95% CI) | HR | (95% CI) |

| Multivitamin | 1749/12 769 | 3094/25 475 | 0.98 | (0.92-1.04) | 1.00 | (0.94-1.07) |

| A-vitamin | 349/2843 | 4324/34 263 | 1.10 | (0.99-1.22) | 1.16 | (1.04-1.29) |

| Beta-carotene | 42/378 | 4881/38 394 | 1.15 | (0.87-1.50) | 1.19 | (0.89-1.58) |

| B6-vitamin | 167/1269 | 4756/37 503 | 1.06 | (0.91-1.24) | 1.14 | (0.97-1.34) |

| Folic acid | 68/509 | 4855/38 263 | 1.08 | (0.85-1.38) | 1.08 | (0.84-1.40) |

| B-complex | 389/3174 | 3174/35 598 | 0.99 | (0.89-1.09) | 1.06 | (0.95-1.18) |

| C-vitamin | 1406/10 905 | 3344/26 806 | 0.96 | (0.90-1.02) | 0.99 | (0.93-1.06) |

| D-vitamin | 477/4082 | 4208/33 105 | 0.95 | (0.87-1.05) | 1.03 | (0.93-1.13) |

| E-vitamin | 683/5403 | 4007/31 774 | 0.93 | (0.85-1.01) | 0.98 | (0.90-1.07) |

| Calcium | 2138/17 428 | 2690/20 735 | 0.81 | (0.77-0.86) | 0.89 | (0.83-0.94) |

| Copper | 31/229 | 4892/38 543 | 1.34 | (0.96-1.87) | 1.44 | (1.02-2.01) |

| Iron | 350/2738 | 4328/34 443 | 1.02 | (0.91-1.14) | 1.06 | (0.95-1.19) |

| Magnesium | 155/1410 | 4768/37 362 | 1.03 | (0.89-1.20) | 1.14 | (0.98-1.33) |

| Selenium | 151/1251 | 4506/35 788 | 1.02 | (0.87-1.19) | 1.12 | (0.95-1.32) |

| Zinc | 344/2635 | 4320/34 398 | 0.99 | (0.89-1.11) | 1.09 | (0.97-1.22) |

| MORTALITY FROM OTHER CAUSES EXCEPT INJURY OR ACCIDENT | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Users | Non-users | Age and energy adjusted | Multivariable adjusted | |||

| Supplement | cases/total | cases/total | HR | (95% CI) | HR | (95% CI) |

| Multivitamin | 1175/12 769 | 2078/25 475 | 1.12 | (1.06-1.19) | 1.17 | (1.10-1.24) |

| A-vitamin | 259/2843 | 2868/34 263 | 0.94 | (0.84-1.05) | 0.99 | (0.89-1.11) |

| Beta-carotene | 25/378 | 3284/38 394 | 0.89 | (0.66-1.21) | 0.99 | (0.72-1.35) |

| B6-vitamin | 123/1269 | 3186/37 503 | 1.04 | (0.89-1.21) | 1.08 | (0.92-1.27) |

| Folic acid | 55/509 | 3254/38 263 | 1.06 | (0.84-1.35) | 1.11 | (0.87-1.43) |

| B-complex | 276/3174 | 3033/35 598 | 0.95 | (0.86-1.06) | 1.02 | (0.92-1.14) |

| C-vitamin | 952/10 905 | 2236/26 806 | 1.01 | (0.95-1.08) | 1.08 | (1.01-1.15) |

| D-vitamin | 340/4082 | 2800/33 105 | 0.87 | (0.79-0.96) | 0.96 | (0.87-1.06) |

| E-vitamin | 504/5403 | 2649/31 774 | 0.96 | (0.89-1.04) | 1.02 | (0.94-1.11) |

| Calcium | 1469/17 428 | 1772/20 735 | 0.90 | (0.85-0.95) | 1.00 | (0.95-1.07) |

| Copper | 24/229 | 3285/38 543 | 1.21 | (0.85-1.73) | 1.32 | (0.92-1.90) |

| Iron | 247/2738 | 2885/34 443 | 1.03 | (0.92-1.14) | 1.10 | (0.98-1.23) |

| Magnesium | 108/1410 | 3201/37 362 | 0.85 | (0.73-1.00) | 0.95 | (0.80-1.12) |

| Selenium | 116/1251 | 3009/35 788 | 0.95 | (0.81-1.12) | 1.08 | (0.91-1.27) |

| Zinc | 246/2635 | 2876/34 398 | 1.00 | (0.89-1.11) | 1.08 | (0.97-1.22) |

Adjusted for age, education, place of residence, diabetes, high blood pressure, body mass index, waist-hip-ratio, hormone replacement therapy, physical activity, smoking, intakes of energy, alcohol, saturated fatty acids, whole grain products, fruits and vegetables.

In multivariable adjusted analyses across the shorter follow-up intervals beginning with the baseline and each respective follow-up questionnaire (Table 4), the most consistent findings were for supplemental iron (HRs 1.20, 1.43, and 1.56, ARIs 2.2%, 5.5%, and 6.6%, respectively), and calcium (HRs 0.89, 0.90, and 0.88, ARRs 1.4%, 1.5%, and 1.8%). Supplemental folic acid tended toward higher risk, significant only in the last interval (HR: 1.28, 1.19, and 1.27, ARIs 3.0%, 2.6%, and 3.4%).

Table 4.

Adjusted hazard ratios (95% CI) for the use of supplements and risk of total mortality women aged 55-69 at baseline, Iowa Women's Health Study.

| Users | Non-users | Age and energy adjusted | Multivariable adjusted1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cases/total | cases/total | HR | (95% CI) | HR | (95% CI) | |

| Multivitamin | ||||||

| FU from 1986 until 1996 | 1366/12 769 | 2764/25 474 | 0.98 | (0.92-1.04) | 1.02 | (0.96-1.10) |

| FU from 1997 until 2003 | 1787/13 674 | 2005/14 174 | 0.91 | (0.86-0.97) | 0.97 | (0.90-1.04) |

| FU from 2004 until 2008 | 1394/12 022 | 943/6577 | 0.83 | (0.76-0.90) | 0.94 | (0.86-1.03) |

| Vitamin A | ||||||

| FU from 1986 until 1996 | 310/2843 | 3675/34 263 | 1.00 | (0.89-1.12) | 1.07 | (0.95-1.21) |

| FU from 1997 until 2003 | 291/2218 | 3053/ 23 028 | 0.95 | (0.84-1.08) | 0.99 | (0.87-1.13) |

| FU from 2004 until 2008 | 151/1126 | 2105/16 990 | 1.04 | (0.87-1.23) | 1.12 | (0.94-1.34) |

| Beta-carotene | ||||||

| FU from 1986 until 1996 | 41/378 | 4140/38 394 | 1.02 | (0.75-1.39) | 1.09 | (0.79-1.51) |

| FU from 1997 until 2003 | 159/1261 | 3741/27 143 | 0.93 | (0.79-1.09) | 1.02 | (0.86-1.21) |

| FU from 2004 until 2008 | 47/469 | 2389/18 655 | 0.82 | (0.61-1.09) | 0.96 | (0.72-1.29) |

| Vitamin B6 | ||||||

| FU from 1986 until 1996 | 140/1269 | 4041/37 503 | 1.02 | (0.86-1.21) | 1.14 | (0.96-1.36) |

| FU from 1997 until 2003 | 364/2613 | 3000/22 723 | 1.02 | (0.91-1.14) | 1.05 | (0.93-1.18) |

| FU from 2004 until 2008 | 156/1487 | 1487/16 525 | 0.83 | (0.70-0.98) | 0.87 | (0.73-1.04) |

| Folic acid | ||||||

| FU from 1986 until 1996 | 66/509 | 4115/38 263 | 1.21 | (0.95-1.54) | 1.28 | (0.99-1.65) |

| FU from 1997 until 2003 | 146/ 951 | 3754/27 453 | 1.16 | (0.98-1.37) | 1.19 | (0.99-1.42) |

| FU from 2004 until 2008 | 198/1321 | 2238/17 803 | 1.21 | (1.04-1.41) | 1.27 | (1.09-1.50) |

| Vitamin B-complex | ||||||

| FU from 1986 until 1996 | 299/3174 | 3882/35 598 | 0.87 | (0.77-0.98) | 0.99 | (0.87-1.11) |

| FU from 1997 until 2003 | 236/1791 | 3664/26 613 | 0.95 | (0.83-1.08) | 0.99 | (0.86-1.14) |

| FU from 2004 until 2008 | 159/1421 | 2277/17 703 | 0.86 | (0.73-1.02) | 0.95 | (0.80-1.13) |

| Vitamin C | ||||||

| FU from 1986 until 1996 | 1098/10 905 | 2949/26 806 | 0.91 | (0.85-0.98) | 0.99 | (0.92-1.06) |

| FU from 1997 until 2003 | 1069/9016 | 2326/16 593 | 0.84 | (0.78-0.91) | 0.86 | (0.79-0.93) |

| FU from 2004 until 2008 | 635/5640 | 1604/12 396 | 0.90 | (0.82-0.99) | 0.97 | (0.88-1.07) |

| Vitamin D | ||||||

| FU from 1986 until 1996 | 401/4082 | 3594/33 105 | 0.88 | (0.80-0.98) | 1.01 | (0.91-1.13) |

| FU from 1997 until 2003 | 379/3003 | 2976/22 231 | 0.95 | (0.85-1.06) | 1.02 | (0.90-1.14) |

| FU from 2004 until 2008 | 258/2343 | 2178/16 781 | 0.83 | (0.72-0.95) | 0.90 | (0.78-1.03) |

| Vitamin E | ||||||

| FU from 1986 until 1996 | 535/5403 | 3443/31 177 | 0.90 | (0.82-0.98) | 1.01 | (0.92-1.11) |

| FU from 1997 until 2003 | 1064/8724 | 2379/17 074 | 0.88 | (0.82-0.95) | 0.92 | (0.85-1.00) |

| FU from 2004 until 2008 | 680/6307 | 1596/11 910 | 0.83 | (0.76-0.91) | 0.94 | (0.85-1.04) |

| Calcium | ||||||

| FU from 1986 until 1996 | 1600/17 428 | 2505/20 735 | 0.75 | (0.71-0.80) | 0.89 | (0.83-0.95) |

| FU from 1997 until 2003 | 1743/14 248 | 1733/ 11 869 | 0.84 | (0.78-0.89) | 0.90 | (0.83-0.97) |

| FU from 2004 until 2008 | 1289/11 600 | 1005/6785 | 0.77 | (0.71-0.84) | 0.88 | (0.81-0.97) |

| Copper | ||||||

| FU from 1986 until 1996 | 30/229 | 4151/38 543 | 1.28 | (0.89-1.83) | 1.43 | (0.98-2.07) |

| FU from 1997 until 2003 | 57/438 | 3843/ 27 966 | 0.93 | (0.71-1.22) | 1.02 | (0.77-1.35) |

| FU from 2004 until 2008 | 24/255 | 2412/18 869 | 0.71 | (0.47-1.08) | 0.83 | (0.55-1.27) |

| Iron | ||||||

| FU from 1986 until 1996 | 324/2738 | 3675/34 443 | 1.11 | (0.99-1.24) | 1.20 | (1.07-1.35) |

| FU from 1997 until 2003 | 448/2395 | 2943/23 070 | 1.42 | (1.28-1.57) | 1.43 | (1.28-1.59) |

| FU from 2004 until 2008 | 334/1645 | 1915/16 305 | 1.67 | (1.48-1.89) | 1.56 | (1.38-1.77) |

| Magnesium | ||||||

| FU from 1986 until 1996 | 156/1410 | 4025/37 362 | 1.02 | (0.87-1.20) | 1.23 | (1.04-1.45) |

| FU from 1997 until 2003 | 212/1606 | 2688/26 798 | 0.98 | (0.85-1.13) | 1.08 | (0.93-1.25) |

| FU from 2004 until 2008 | 142/1273 | 2294/17 851 | 0.91 | (0.77-1.09) | 1.05 | (0.88-1.25) |

| Selenium | ||||||

| FU from 1986 until 1996 | 127/1251 | 3834/35 788 | 0.94 | (0.79-1.12) | 1.11 | (0.92-1.33) |

| FU from 1997 until 2003 | 205/1624 | 3157/23 711 | 0.97 | (0.84-1.12) | 1.09 | (0.94-1.27) |

| FU from 2004 until 2008 | 94/913 | 2135/16 931 | 0.82 | (0.67-1.02) | 0.95 | (0.76-1.18) |

| Zinc | ||||||

| FU from 1986 until 1996 | 279/2635 | 3705/34 398 | 0.96 | (0.85-1.08) | 1.11 | (0.98-1.26) |

| FU from 1997 until 2003 | 353/2989 | 3023/22 433 | 0.85 | (0.76-0.95) | 0.90 | (0.80-1.02) |

| FU from 2004 until 2008 | 190/1599 | 2034/16 247 | 0.93 | (0.80-1.08) | 1.03 | (0.88-1.21) |

Adjusted for age, education, place of residence, diabetes, high blood pressure, body mass index, waist-hip-ratio, hormone replacement therapy, physical activity, smoking, intakes of energy, alcohol, saturated fatty acids, whole grain products, fruits and vegetables. Updated data covariates were used in the interval analyses if information was available. For 1997 analyses updated covariate data were available for diabetes, high blood pressure, BMI, hormone replacement therapy, and smoking while for 2004 analyses updated data were available for all covariates except education, place of residence and waist-hip-ratio.

Dose response associations could be computed for selected supplements. The inverse association with calcium was lost at its highest dose (Table 5). For supplemental iron a dose response relationship was observed from 1986 in full follow-up. In the dose-response interval analyses, significantly increased risk was seen at progressively lower doses as the women aged through baseline in 1986, to baseline in 1997, to baseline in 2004. For vitamins A, C, E and D, and minerals selenium and zinc no dose-response was found. These dose response associations persisted after excluding women with a history of CVD, diabetes, or cancer at baseline.

Table 5.

Multivariable adjusted1 hazard ratios (95% CI) for the dose of calcium iron and zinc supplements and risk of total mortality women aged 55-69 at baseline, Iowa Women's Health Study.

| Dose | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | HR | Cases | HR | 95% CI | Cases | HR | 95% CI | Cases | HR | 95% CI | Cases | HR | 95% CI | |

| Calcium | Non-users | >0-400 mg/d | >400-900 mg/d | >900-1300 mg/d | >1300 mg/d | |||||||||

| FU from 86 until 08 | 8847 | 1 | 1345 | 0.91 | (0.85-0.96) | 2973 | 0.91 | (0.87-0.95) | 1229 | 0.86 | (0.81-0.91) | 504 | 1.01 | (0.92-1.11) |

| FU from 86 until 96 | 2505 | 1 | 323 | 0.84 | (0.74-0.95) | 709 | 0.83 | (0.76-0.90) | 304 | 0.84 | (0.74-0.94) | 137 | 1.03 | (0.86-1.23) |

| FU from 97 until 03 | 1733 | 1 | 254 | 0.85 | (0.73-0.98) | 601 | 0.80 | (0.72-0.89) | 268 | 0.84 | (0.73-0.97) | 109 | 0.91 | (0.74-1.12) |

| FU from 04 until 08 | 1003 | 1 | 98 | 0.88 | (0.70-1.09) | 520 | 0.83 | (0.74-0.93) | 309 | 0.83 | (0.72-0.95) | 111 | 0.92 | (0.75-1.13) |

| Iron | Non-users | >0-50 mg/d | >50-200 mg/d | >200-400 mg/d | >400 mg/d | |||||||||

| FU from 86 until 08 | 13 | 1 | 527 | 1.02 | (0.93-1.12) | 222 | 1.08 | (0.94-1.24) | 118 | 1.35 | (1.12-1.63) | 47 | 1.57 | (1.17-2.11) |

| FU from 86 until 96 | 3675 | 1 | 144 | 1.09 | (0.92-1.30) | 59 | 1.12 | (0.86-1.46) | 37 | 1.41 | (1.01-1.96) | 16 | 1.70 | (1.02-2.83) |

| FU from 97 until 03 | 2943 | 1 | 115 | 1.13 | (0.92-1.39) | 74 | 1.69 | (1.33-2.14) | 59 | 1.30 | (0.97-1.74) | 14 | 1.91 | (1.06-3.45) |

| FU from 04 until 08 | 1913 | 1 | 71 | 1.66 | (1.28-2.14) | 71 | 1.85 | (1.43-2.39) | 58 | 1.67 | (1.25-2.22) | 17 | 2.01 | (1.19-3.40) |

Adjusted for age, education, place of residence, diabetes, high blood pressure, body mass index, waist-hip-ratio, hormone replacement therapy, physical activity, smoking, intakes of energy, alcohol, saturated fatty acids, whole grain products, fruits and vegetables. Updated data covariates were used in the interval analyses if information was available. For 1997 analyses updated covariate data were available for diabetes, high blood pressure, BMI, hormone replacement therapy, and smoking while for 2004 analyses updated data were available for all covariates except education, place of residence and waist-hip-ratio.

For supplemental iron we also studied consistency of reported use across surveys and total mortality among 16 841 women who answered all three questionnaires. Compared to non-users, the multivariable adjusted HRs and 95% CIs were 1.35 (95% CI, 1.20-1.52) for use reported at 1 survey, 1.62 (95% CI, 1.30-2.01) for use reported at 2 surveys, and 1.60 (95% CI, 1.04-2.46) for use reported at all 3 surveys.

Comment

In agreement with our hypothesis, most of the supplements studied were not associated with reduced total mortality rate in older women. In contrast, we found that several commonly used dietary vitamin and mineral supplements, including multivitamins, vitamins B6 and folic acid, and minerals iron, magnesium, zinc and copper were associated with higher risk of total mortality. Of particular concern, supplemental iron was strongly and dose-dependently associated with increased total mortality risk. The association was also consistent across shorter intervals, strengthened with multiple usage reports and with increasing age at reported use. Supplemental calcium was consistently inversely related with the mortality, however, with no clear dose-response.

Previous studies have provided little support for our finding suggesting beneficial effects of calcium on total mortality. In a recent meta-analysis of prospective cohorts and RCTs, vitamin D supplementation, but not calcium, was found to be associated with a non-significant reduction in CVD mortality.21 The pooled HR for the CVD risk of RCTs was 0.90 (95% CI, 0.77-1.05) for vitamin D and 1.14 (95% CI, 0.92-1.41) for calcium, respectively. In our analyses we found no evidence for benefit of vitamin D against total mortality.

The evidence regarding possible harmful effect of supplemental iron is limited. Pocobelli et al.6 found that men in the highest category of average 10-year dose of supplemental iron had a 27% increased risk of total mortality when compared to non-users in age and sex adjusted models. The association was, however, attenuated after multivariable adjustment. High iron stores, measured as serum ferritin, have been found to be related with increased risk of CVD in one22, 23, but not in the majority of the studies.24 Although we did not study the possible mechanism, iron is suggested to catalyze reactions that produce oxidants, and thus promote oxidative stress.25 However, we cannot rule out the possibility that the increase in total mortality was caused by illness for which use of iron supplements was indicated. Chronic disease, major injury and/or surgery may cause anemia which is then treated with supplemental iron. However, we could find no evidence for such reverse causality. Iron supplementation was related to future mortality even 19 years later in women free of heart disease, diabetes, and cancer, baseline covariates of iron use were not greatly different from those of other supplements, and progressively lower doses were associated with excess risk as the women aged.

Increased blood homocysteine (Hcy) concentrations are considered to be modifiable risk factor for CVD.26 In RCTs, folic acid, vitamin B6 and B12 or their combinations have decreased blood Hcy concentrations, but failed to reduce the risk of CVD.14,27 In contrast, use of B-vitamins has been found to be related with an increased risk in some studies.13 Ebbing et al.13 found that the combination of folic acid and B12 supplementation increased the risk of mortality from all-causes and cancer in an RCT setting.

We are not aware of long-term RCTs studying the effects of daily multivitamins on total mortality, while the epidemiological studies have not provided evidence of benefit.5,7-9 Observational findings on the antioxidant supplements selenium, beta-carotene, and vitamins A, C, and E and total mortality have been inconsistent5,6,9, although the use of vitamin C and E have been found to related with reduced risk of all cause mortality in several studies.5,9 For supplemental vitamin A and beta-carotene, observational studies have not provided evidence of benefit for total mortality.6 In RCTs the supplementation of selenium, beta-carotene, or vitamins A, C or E has not been found to be beneficial relative to total mortality in well-nourished populations,10,11 and some studies suggest harm.12,13

Strengths of the current study include the large sample size and longitudinal study design. In addition, the use of dietary supplements was queried three times, at baseline in 1986, 1997 and 2004. The use of repeated measures enabled studying the consistency of the findings and decreased the risk that the exposure was misclassified.

Our study has also limitations. An intermediate event such as CVD or cancer can induce a change in supplement use and confound the exposure-outcome association. In our data, the use of supplements was not modified by a pre-baseline diagnosis of CVD, diabetes, or cancer. Furthermore, intermediate cancer did not alter the supplement taking pattern. It is possible that despite extensive adjustment, residual confounding remained. The use of dietary supplements is related to healthier lifestyle1,2, thus leading to apparently inverse associations with total mortality. The associations found after adjustment for lifestyle factors are more accurate from a perspective of a causal relationship. At the same time, we cannot completely exclude the possibility that some supplements were taken for good cause in response to symptoms or clinical disease. We did not have data about nutritional status or detailed information of supplement used. Also, the study population consisted of only of Caucasian women and thus generalization to other populations, ethnic groups or men could be questioned. Since our primary hypothesis concerning supplement use and total mortality with covariate adjustment included 15 separate tests, a conservative Bonferroni approach would require a p-value of 0.05/15 = 0.0033. However, many of the additional statistical tests were confirmatory, strengthening confidence that findings were not explainable by chance.

Among the elderly, the use of dietary supplements is widespread1-3 and supplements are often used with the intention of attaining health benefits against chronic diseases. While we cannot rule out benefits of supplement taking, such as improved quality of life, our study raises a concern for the long term safety of supplement use. Also, cumulative effects of widespread supplement use together with food fortification have raised concern about exceeding upper recommended levels and thus long-term safety. 1 While it is not advisable to make a causal statement of excess risk based on these observational data, it is noteworthy that dietary supplements, unlike drugs, do not require rigorous RCT testing, and observational studies are often the best available method for assessing the safety of long-term use. Based on existing evidence, we see little justification for the general and widespread use of dietary supplements. We would prefer that they be used with good medically-based cause, such as symptomatic nutrient deficiency disease.

In conclusion, in this large prospective cohort of older women, we found that most dietary supplements were unrelated to mortality. However, several commonly used dietary vitamin and mineral supplements were associated with increased risk of total mortality, most strongly supplemental iron, while calcium showed some evidence of lower risk.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was partially supported by grant R01 CA39742 from the National Cancer Institute and by grants from the Academy of Finland (JM, 131209), Finnish Cultural Foundation (JM) and Fulbright (Research Grant for a Junior Scholar) (JM).

Role of the Sponsors: The sponsors did not play a role in the conception, design or conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author contributions: JM had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. DRJ, KR and LH collected the data, obtained the funding, and provided administrative, technical, or material support. JM and DRJ analyzed and interpreted the data, drafted the manuscript, and provided statistical expertise. JM, KR, LH, KP and DRJ and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Financial Disclosures: DRJ is an unpaid member of the Scientific Advisory Board of the California Walnut Commission. All other authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- 1.NIH State-of-the-Science Conference Statement on Multivitamin/Mineral Supplements and Chronic Disease Prevention. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:364–371. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-5-200609050-00136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park K, Harnack L, Jacobs DR. Trends in Dietary Supplement Use in a Cohort of Postmenopausal Women from Iowa. Am J epidemiol. 2009;169(7):887–892. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Radimer K, Bindewald B, Hughes J, Ervin B, Swanson C, Picciano MF. Dietary supplement use by US adults: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999-2000. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(4):339–349. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silver HJ. Oral strategies to supplement older adults' dietary intakes: comparing the evidence. Nutr Rev. 2009;67:21–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watkins ML, Erickson JD, Thun MJ, Mulinare J, Heath CW., Jr Multivitamin use and mortality in a large prospective study. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152(2):149–162. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pocobelli G, Kristal AR, Patterson RE, et al. Total mortality risk in relation to use of less-common dietary supplements. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91(6):1791–1800. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neuhouser ML, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Thomson C, et al. Multivitamin use and risk of cancer and cardiovascular disease in the Women's Health Initiative cohorts. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(3):294–304. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park SY, Murphy SP, Wilkens LR, Henderson BE, Kolonel LN. Multivitamin use and the risk of mortality and cancer incidence: the multiethnic cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(8):906–14. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pocobelli G, Peters U, Kristal AR, White E. Use of supplements of multivitamins, vitamin C, and vitamin E in relation to mortality. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170(4):472–83. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sesso HD, Buring JE, Christen WG, et al. Vitamins E and C in the prevention of cardiovascular disease in men: the Physicians' Health Study II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;12(1):2123–2133. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee IM, Cook NR, Manson JE, Buring JE, Hennekens CH. Beta-carotene supplementation and incidence of cancer and cardiovascular disease: the Women's Health Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91(24):2102–2106. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.24.2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Albanes D, Heinonen OP, Huttunen JK, et al. Effects of alpha-tocopherol and beta-carotene supplements on cancer incidence in the Alpha-Tocopherol Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;62(6 Suppl):1427S–1430S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/62.6.1427S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ebbing M, Bønaa KH, Nygård O, Arnesen E, Ueland PM, Nordrehaug JE, Rasmussen K, Njølstad I, Refsum H, Nilsen DW, Tverdal A, Meyer K, Vollset SE. Cancer incidence and mortality after treatment with folic acid and vitamin B12. JAMA. 2009;302(19):2119–2126. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bazzano LA, Reynolds K, Holder KN, He J. Effect of folic acid supplementation on risk of cardiovascular diseases: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2006;296(22):2720–2726. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.22.2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bjelakovic G, Nikolova D, Gluud LL, Simonetti RG, Gluud C. Mortality in randomized trials of antioxidant supplements for primary and secondary prevention: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2007;297(8):842–857. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.8.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Folsom AR, Kushi LH, Anderson KE, et al. Associations of general and abdominal obesity with multiple health outcomes in older women: the Iowa Women's Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(14):2117–2128. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bisgard KM, Folsom AR, Hong CP, et al. Mortality and cancer rates in nonrespondents to a prospective study of older women: 5-year follow-up. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;139(10):990–1000. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Willett WC, Sampson L, Brown ML, et al. The use of a self-administered questionnaire to assess diet four years in the past. Am J Epidemiol. 1988;127(1):1888–1899. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Munger RG, Folsom AR, Kushi LH, Kaye SA, Sellers TA. Dietary assessment of older Iowa women with a food frequency questionnaire: nutrient intake, reproducibility, and comparison with24-hour dietary recall interviews. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;136(2):192–200. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murphy SP, Wilkens LR, Hankin JH, et al. Comparison of two instruments for quantifying intake of vitamin and mineral supplements: a brief questionnaire versus three 24-hour recalls. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156(7):669–675. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang L, Manson JE, Song Y, Sesso HD. Systematic review: Vitamin D and calcium supplementation in prevention of cardiovascular events. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(5):315–323. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-5-201003020-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salonen JT, Nyyssonen K, Korpela H, et al. High stored iron levels are associated with excess risk of myocardial infarction in eastern Finnish men. Circulation. 1992;86(3):803–811. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.3.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salonen JT, Nyyssonen K, Salonen R. Body iron stores and risk of coronary heart disease. (Letter) N Engl J Med. 1994;331(17):1159–1160. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199410273311714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Danesh J, Appleby P. Coronary heart disease and iron status: meta-analyses of prospective studies. Circulation. 1999;99(7):852–854. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.7.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jomova K, Valko M. Advances in metal-induced oxidative stress and human disease. Toxicology. 2011;283(2-3):65–87. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Humphrey LL, Fu R, Rogers K, Freeman M, Helfand M. Homocysteine level and coronary heart disease incidence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(11):1203–1212. doi: 10.4065/83.11.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clarke R, Halsey J, Lewington S, Lonn E, Armitage J, Manson JE, et al. Effects of lowering homocysteine levels with B vitamins on cardiovascular disease, cancer, and cause-specific mortality: Meta-analysis of 8 randomized trials involving 37 485 individuals. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(18):1622–31. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.