Abstract

1α,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 [1,25(OH)2D3] has been demonstrated to inhibit the growth of cancer cells. However, carboplatin is the most widely used chemotherapeutic agent to treat cancer. We hypothesized that vitamin D may enhance the antiproliferative effects of carboplatin, and tested this hypothesis in ovarian cancer SKOV-3 cells treated with carboplatin and 1,25(OH)2D3. Cell viability was determined by Cell Counting Kit-8, while cell cycle distribution, apoptosis, reactive oxygen species (ROS) and mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) were analyzed by flow cytometry. In these experiments, 1,25(OH)2D3 and carboplatin each provided dose-dependent suppression of SKOV-3 growth, and synergy was demonstrated between 10 nM 1,25(OH)2D3 and carboplatin. The proportion of cells in G0/G1 phase was markedly reduced by the drug combination, while the proportion of cells in G2/M phase was increased. Apoptosis did not increase in ovarian cancer cells treated with 10 nM 1,25(OH)2D3 alone; however, 1,25(OH)2D3 evidently enhanced carboplatin-induced apoptosis. Similarly, ROS production was evidently higher and MMP was lower in cells treated with the two drugs than in those treated with each drug alone. The results suggested that 1,25(OH)2D3 suppresses SKOV-3 growth and enhances the antiproliferative effect of carboplatin. The drugs function synergistically by inducing cell cycle arrest, increasing apoptosis and ROS production, and reducing MMP.

Keywords: 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3; carboplatin; ovarian cancer; SKOV-3 cells

Introduction

Ovarian cancer is a serious global threat to female health and is a leading cause of cancer-related mortality in females, often due to late-stage recognition and aggressive tumor relapse (1). High patient morbidity is attributable in part to the recurrent growth of residual ovarian tumor cells that become resistant to standard chemotherapeutic treatments, and then aggressively proliferate and spread or metastasize to multiple sites. In total, 70% of females diagnosed with ovarian cancer present with advanced malignant disease and usually undergo surgery followed by a combination of paclitaxel and platinum-based chemotherapy (2,3). However, recurrences occur in the majority of patients, and only ~30% of patients with distant metastases survive five years following diagnosis (4,5). Failure of chemotherapy in recurrent ovarian cancer is usually due to the development of resistance to one or the two main classes of chemotherapy agents used to treat ovarian cancer (6–8). Novel therapeutic approaches are therefore necessary for the management of advanced and recurrent ovarian cancer.

Platinating agents, such as carboplatin, are potent chemotherapeutic agents widely used for the adjuvant treatment of primary ovarian cancer and metastatic disease. The drug induces the formation of DNA adducts, G2 phase cell cycle arrest and the subsequent triggering of apoptosis. However, the efficacy of carboplatin is limited by drug resistance and side-effects, including nephrotoxicity, myelosuppression and neurotoxicity (9,10). The mechanisms underlying the development of resistance to platinating agents, particularly carboplatin, include the repair of DNA lesions, translesion DNA synthesis, altered drug transport, increased antioxidant production and reduction of apoptosis (11–13). Altered gene expression affecting cellular transport, DNA repair, apoptosis and cell-cell adhesion are the mechanisms of platinum resistance that have been observed in patient samples (14,15). Therapeutic success may therefore be improved if tumor cells can be sensitized to carboplatin treatment with a combination therapy.

1α,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 [1,25(OH)2D3] is the most active metabolite of vitamin D3. It is a scarce natural product that is synthesized predominantly in the skin from 7-dehydrocholesterol by exposure to ultraviolet sunlight. Although its classical role as the major regulator of calcium homeostasis and bone formation/resorption has been recognized for some time (16), more recent findings suggest that 1,25(OH)2D3 is an important modulator of cellular proliferation and differentiation in a variety of benign and malignant cells. 1,25(OH)2D3 also exhibits anti-invasion, antiangiogenesis and antimetastatic activity in vivo (17–21) and acts as a chemopreventive agent in animal models of lung, colorectal and breast cancer (22–24).

The aim of this study was to determine whether 1,25(OH)2D3 enhances the cytostatic effects of carboplatin in SKOV-3 cells and to characterize the mechanism of its effect.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and agents

The human ovarian serous papillary cystadenocarcinoma SKOV-3 cell line was purchased from the Type Culture Collection of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (TCCCAS; Shanghai, China) and was verified as mycoplasma free. Authenticity of the cell line was confirmed by the TCCCAS. The SKOV-3 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin and 5 mg/ml streptomycin. These agents and trypsin-EDTA solution were purchased from Invitrogen Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA, USA). 1,25(OH)2D3 and carboplatin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) and Qilu Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Jinan, China), respectively. 1,25(OH)2D3 was dissolved in ethanol and stored in a concentrated solution (10−5 mol/l) at −80°C. The 1,25(OH)2D3 was freshly diluted in RPMI 1640 prior to each experiment. The ethanol concentrations in each experiment were ≤0.1%. The carboplatin solution was prepared with sterile distilled water and fresh stocks were prepared on the day of each experiment, and dilutions were prepared with RPMI 1640.

Cell viability assay

The viability of SKOV-3 cells was determined by Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan). Briefly, cells at the exponential phase were collected, transferred to 96-well plates (2,000 cells/well) and cultured overnight. The plating medium was removed and replaced with a medium containing the appropriate concentration of vehicle (0.1% ethanol), 1,25(OH)2D3 (0.1, 1, 5, 10, 50, 100, 200 and 500 nM) or carboplatin (0.2, 2, 20, 40, 80 and 160 mg/l). The combined effects were evaluated by incubation with 1,25(OH)2D3 and carboplatin. Cells were allowed to grow for an additional 72 h, then 10 μl of CCK-8 solution was added and the cells were incubated for 1 h. Absorbance (Abs) was measured at 450 nm in a microplate reader (BioTec Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA) and growth inhibition was calculated as the percentage difference of the treated cells versus the vehicle controls, according to the following formula: Inhibition rate (%) = [(Abs of vehicle control cells - Abs of treated cells)/Abs of vehicle control cells] × 100. Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

Data were analyzed using KaleidaGraph (Synergy Software, Reading, PA, USA) to determine the drug IC50 value. The combined index (CI) was used to evaluate the drug combination assays according to the following formula (25): CI = DA/IC50,A + DB/IC50,B, where DA is the IC50 of drug A when A was combined with B, DB is the IC50 of drug B when A was combined with B, IC50,A is the IC50 of drug A, and IC50,B is the IC50 of drug B. Each CI was calculated from the mean affected fraction at each drug ratio concentration in triplicate. CI>1, CI=1, and CI<1 indicated antagonism, additive effect or synergy, respectively (26).

Cell cycle analysis

SKOV-3 cells were grown to 50% confluence in 35-mm dishes and treated with the vehicle control, 10 nM 1,25(OH)2D3, 40 mg/l carboplatin, or a combination of the two drugs for 72 h. The cells were harvested by pooling the floating cells with the trypsinized monolayers and were pelleted by centrifugation at 179 × g for 5 min. Following fixation with cold 75% ethanol, the cells were resuspended in a solution of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4) containing 25 mg/ml propidium iodide (PI; Sigma-Aldrich), 0.1 mM EDTA (Invitrogen Life Technologies) and 0.01 mg/ml DNase-free RNase (Invitrogen Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, OR, USA). The samples were incubated for 15 min at room temperature prior to cell cycle analysis using a FC500 flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA). Statistics were performed on 20,000 events per sample using MultiCycle DNA Content and DNA cell cycle analysis software (MutiCycle AV for Windows; Phoenix Flow System, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

Apoptosis assay

The number of apoptotic cells was determined using the Alexa Fluor 488 Annexin V/Dead Cell apoptosis kit (Invitrogen Life Technologies). Following treatment, the cells were harvested and washed with PBS, then suspended in PBS with PI and Annexin V. The cell suspensions were incubated in the dark for 15 min at 37°C and then analyzed on a FC500 flow cytometer.

Confocal laser-scanning microscopy was performed using an SP-2 confocal laser-scanning microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) equipped with an oil immersion objective (63X). Nuclear images were obtained at an excitation wavelength of 405 nm of 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI).

Measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP)

MMP was measured using JC-1 dye (Invitrogen Life Technologies), a cationic dye that aggregates in the mitochondria of healthy cells; at high concentrations, JC-1 monomers (green fluorescence) form aggregates (red fluorescence). The ratio of the green/red fluorescence is independent of mitochondrial shape, density or size, and depends only on the membrane potential. MMP analysis was performed as previously described (27). Briefly, SKOV-3 cells were treated for 72 h, then harvested and stained with 10 μM JC-1 at 4°C for 1 h prior to flow cytometry analysis. JC-1 was excited with the 488-nm argon laser (Beckman Coulter) and JC-1 green and red fluorescence was recorded using 530 nm ± 15 nm and a 590 nm ± 15 nm band pass filter channels. A minimum of 20,000 cells within the gated region were analyzed. The cell sorting gates used were FL-2 versus FL-1 blotting (28). The ratio of the fluorescence intensity at 590 nm to that at 530 nm (FL-2:FL-1 ratios) was considered the relative MMP value. Data are presented as the mean of three experiments.

Measurement of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS)

Intracellular ROS was measured by a cell-permeating probe, 5-[and-6]-chloromethyl-2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate, acetyl ester (CM-H2DCFDA, Invitrogen Molecular Probes), as previously described (29). CM-H2DCFDA is a non-polar compound that is hydrolyzed upon cell entry, forming a non-fluorescent derivative that can be converted into a fluorescent product in the presence of a true oxidant. Mean fluorescence intensity was used as measure of ROS level as determined by flow cytometer. Cells were treated for 72 h, washed and loaded with 10 μM CM-H2DCFDA for 1 h. Green fluorescence intensity was used as a measure of relative intracellular ROS by flow cytometry at 530 nm. A total of 20,000 cells within the gated region were analyzed. Data are presented as the mean of three experiments

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS, version 13.0 for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. One-way analysis of variance was used to evaluate differences between the groups. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Dose-response of SKOV-3 cells to 1,25(OH)2D3 and carboplatin

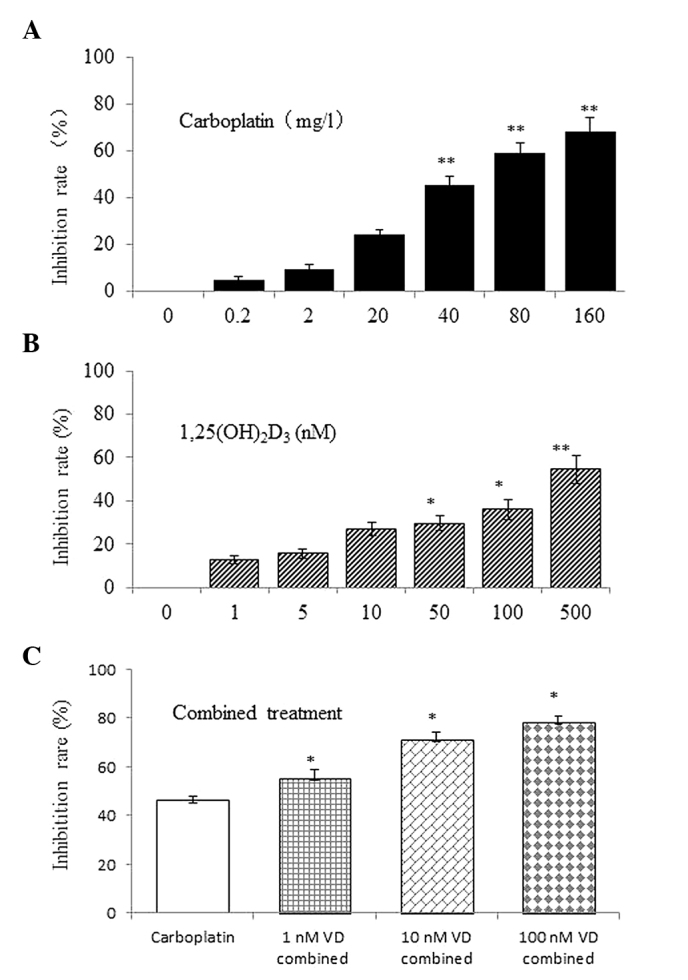

Initial experiments were performed to determine the range of drug concentrations that would elicit growth inhibition in ovarian cancer cells. SKOV-3 cells were incubated with graded 1,25(OH)2D3 (0.1, 1, 5, 10, 50, 100, 200 and 500 nM) and carboplatin (0.2, 2, 20, 40, 80, and 160 mg/l). In the cell viability assay, 1,25(OH)2D3 inhibited growth in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1A). Carboplatin also suppressed the viability of SKOV-3 cells in a similar manner (Fig. 1B). The differences between the vehicle control and test groups were statistically significant (P<0.05). Based on 10–90% inhibition rates of cell growth in the KaleidaGraph program, the IC50 values of 1,25(OH)2D3 and carboplatin were 420.45 nM (R2=0.9904) and 54.6 mg/l (R2=0.9923), respectively.

Figure 1.

1,25(OH)2D3 and/or carboplatin inhibition of SKOV-3 cell growth. Growth inhibition increased with increasing doses of (A) carboplatin and (B) 1,25(OH)2D3 over 72 h. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01, vs. the vehicle control. (C) Growth inhibition also increased with combined 1,25(OH)2D3 and carboplatin treatment. *P<0.05, vs. single-drug treatment. 1,25(OH)2D3, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3.

Combined administration of 1,25(OH)2D3 and carboplatin

To determine whether the drugs work synergistically, SKOV-3 cells were treated with carboplatin in the presence of 1,25(OH)2D3. The growth inhibition was significantly greater with the combined treatment (Fig. 1C) and greater synergy was achieved at 40 mg/l carboplatin in combination with 10 nM 1,25(OH)2D3 (CI=0.57). The IC50 of carboplatin evidently decreased with increasing 1,25(OH)2D3 concentrations (Table I).

Table I.

Effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 and carboplatin combination on the growth of SKOV-3 cells.

IC50 (half the inhibitory concentration) of 1,25(OH)2D3 was 420.45 nM.

CI>1, antagonism; CI=1, additive effect; and CI<1, synergy.

It was not possible to calculate the CI with a concentration of 0 nm 1,25(OH)2D3.

CI, combined index; 1,25(OH)2D3, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3.

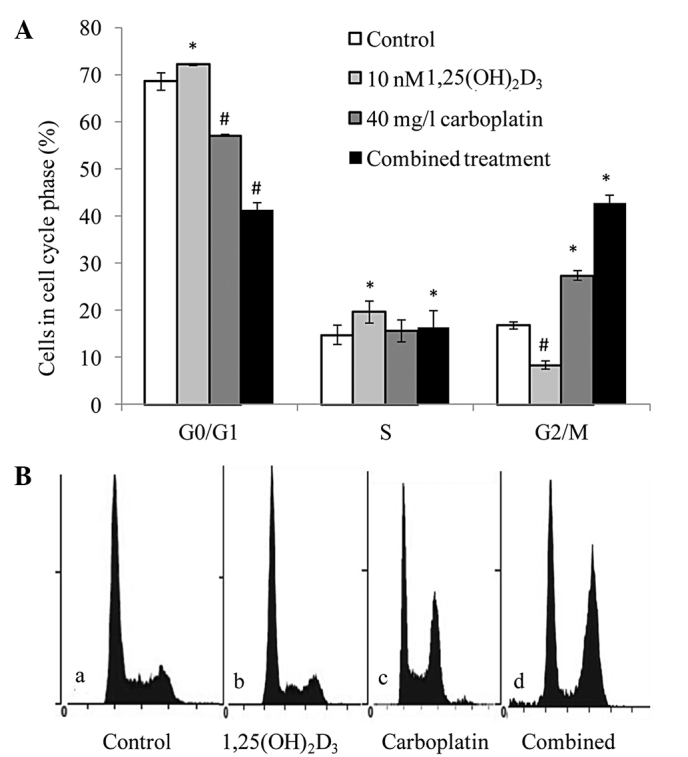

Cell cycle analysis

To determine whether 1,25(OH)2D3 enhancement of the antiproliferative activity of carboplatin was due to alterations in the cell cycle, the cell cycle distribution of SKOV-3 cells treated with the vehicle control, 10 nM 1,25(OH)2D3, 40 mg/l of carboplatin and the drugs in combination were compared. Compared with the vehicle control, 1,25(OH)2D3 significantly increased the percentage of cells in G0/G1 phase, accompanied by a reduction of cells in G2/M phase. The reverse effect occurred with carboplatin; a decrease in cells in G0/G1 phase and an increase in cells in G2/M phase was observed. However, the percentage of cells in S phase changed very little. Following treatment with 10 nM 1,25(OH)2D3 and 40 mg/l carboplatin, the distribution of G0/G1-phase cells in SKOV-3 cells was further reduced, while cells in G2/M phase evidently increased (Fig. 2A and B). Therefore, it was concluded that the combined treatment had a similar effect as carboplatin treatment alone, but this observation regarding cell cycle arrest requires more consideration.

Figure 2.

Combined effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 and carboplatin on cell cycle distribution. (A) G2/M cell cycle arrest in SKOV-3 cells treated with 1,25(OH)2D3 and carboplatin versus the untreated cells. */#P<0.05, vs. the vehicle controls. (B) Flow cytometric analysis: a, control group; b, 10-nM 1,25(OH)2D3 group; c, 40-mg/l carboplatin group; and d, combined treatment group. Similar results were obtained in all three experiments. 1,25(OH)2D3, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3.

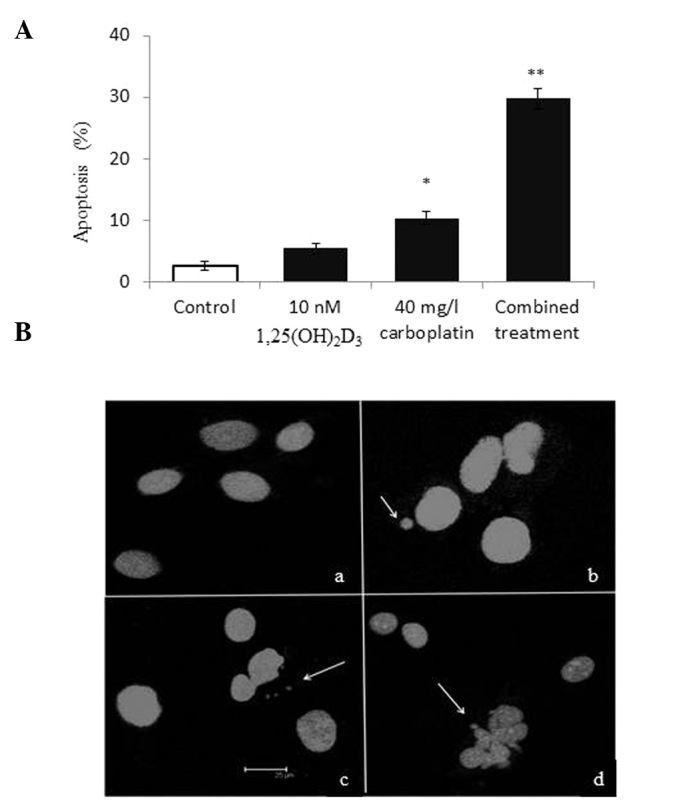

Apoptosis in combination treatment of 1,25(OH)2D3 and carboplatin

Apoptosis was assessed to identify the mechanism of growth inhibition by the combined treatment of 1,25(OH)2D3 and carboplatin in ovarian cancer cells. Apoptosis was increased in SKOV-3 cells treated with 40 mg/l carboplatin, but the increase was not significant in cells treated with 10 nM 1,25(OH)2D3 (a dose of 100 nM did increase apoptosis, data not shown) compared with the control group. However, apoptosis was evidently increased by combined treatment (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, confocal laser-scanning microscopy with DAPI staining demonstrated that cells treated with the two drugs exhibited apoptotic nuclei with DNA fragmentation, chromatin condensation and formation of apoptotic bodies (Fig. 3B), and that cells treated with single drugs contained fewer apoptotic nuclei than cells treated with both drugs.

Figure 3.

Combined effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 and carboplatin on apoptosis in SKOV-3 cells. (A) Apoptosis increased following the combined treatment of 1,25(OH)2D3 and carboplatin versus the untreated cells. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01, vs. the vehicle controls. (B) Nuclei of SKOV-3 cells (stain, 4′6-diamidino-2-phenylindole): a, control group; b, 10-nM 1,25(OH)2D3 group; c, 40-mg/l carboplatin group; and d, combined treatment group. Arrows indicate the fragmented DNA from the nuclei. 1,25(OH)2D3, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3.

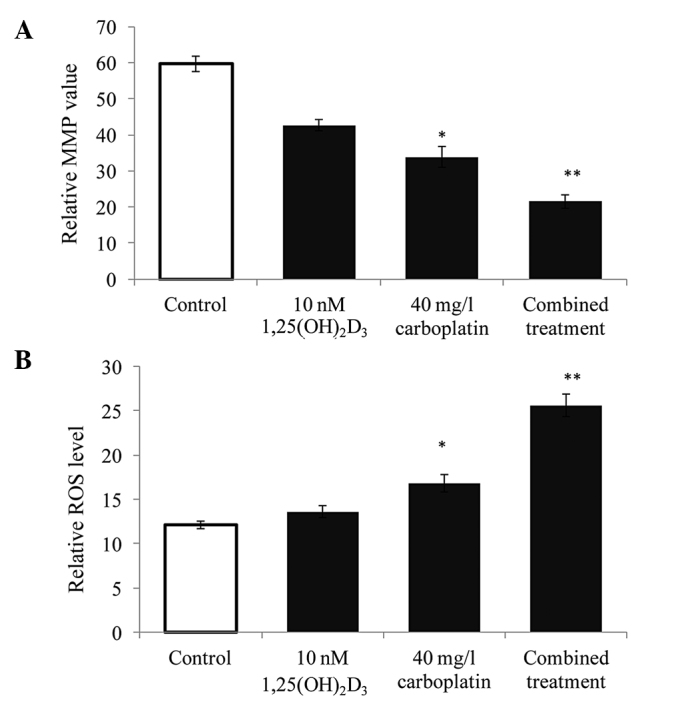

MMP change following combination treatment

Depolarization of MMP is a characteristic feature of apoptosis; hence, treated cells were examined for a drop in MMP. MMP was not found to significantly reduce with 10 nM of 1,25(OH)2D3 in SKOV-3 cells, but MMP dropped in cells treated with 40 mg/l carboplatin. The maximal effect was obtained with combined 1,25(OH)2D3 and carboplatin treatment (Fig. 4A). Each drug alone inhibited growth, increased apoptosis and reduced MMP. Thus, 1,25(OH)2D3 further reduces the MMP of ovarian cells induced by carboplatin; however, 10 nM of 1,25(OH)2D3 alone did not reduce MMP.

Figure 4.

Combined effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 and carboplatin on ROS production and MMP loss in SKOV-3 cells. (A) MMP was reduced in SKOV-3 cells following combination treatment versus the controls. (B) ROS production increased in SKOV-3 cells following the combined treatment versus the untreated controls. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01, vs. the vehicle controls. 1,25(OH)2D3, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3; ROS, reactive oxygen species; MMP, mitochondrial membrane potential.

ROS production following combined treatment

Oxidative stress appears to be critical for tumor therapy, as ROS overproduction corresponds to an increase in apoptosis. In order to assess whether the growth suppression of 1,25(OH)2D3 and carboplatin is due to ROS production, ROS were measured as detected by CM-H2DCFDA and expressed as the mean fluorescence by flow cytometry in comparison with the vehicle controls. The ROS levels in cells treated with 40 mg/l carboplatin were evidently increased, while those of cells treated with 10 nm 1,25(OH)2D3 were not found to significantly increase in comparison with the vehicle control. Although carboplatin treatment alone increases ROS production, the combined treatment produced a clear increase in ROS levels compared with the vehicle control (Fig. 4B). Thus, the growth inhibition of ovarian cancer cells can be induced by the increase of ROS triggered by the combined treatment.

Discussion

The primary actions of 1,25(OH)2D3 are mediated through the nuclear vitamin D receptor (VDR), a member of the steroid/thyroid hormone superfamily of ligand-activated transcription factors. VDR has been found in rat ovaries by immunohistochemistry (30), as well as hen ovaries by ligand binding assays (31), indicating that the ovary is a target organ for vitamin D. Studies have also shown that VDR is expressed in gynecologic neoplasms, such as ovarian cancer (32,33), which suggests that 1,25(OH)2D3 may be effective against ovarian cancer. The correlation between vitamin D and the risk of ovarian cancer has also received unprecedented attention. Several ecological studies have reported that ovarian cancer mortality inversely correlates with sun exposure, which initiates vitamin D production in the skin (34,35). Other studies of dietary intake of vitamin D have also observed an inverse correlation with ovarian cancer risk (36,37). Therefore, the inverse correlation between vitamin D level and ovarian cancer-related mortality suggests that the insufficiency of 1,25(OH)2D3 may contribute to ovarian cancer initiation and/or progression.

In this study, 1,25(OH)2D3 was demonstrated to inhibit ovarian cancer SKOV-3 cell growth in a dose-dependent manner. It also markedly enhanced the inhibitory effects of carboplatin on ovarian cancer cells at a concentration of 10 nM 1,25(OH)2D3. While this has been viewed as the major anticancer effect for 1,25(OH)2D3, its mechanism remains uncertain.

Cell-cycle perturbation is central to chemotherapy-mediated antiproliferative activity in tumor cells, and combined treatment with 1,25(OH)2D3 and carboplatin in the current study led to a significant increase in the percentage of G2/M-phase cells and an evident decrease in G0/G1-phase cells. Moffatt et al (38) also demonstrated that, over time, combined 1,25(OH)2D3 and carboplatin increases the percentage of prostate cancer cells in G2/M phase. The authors found this trend to correlate with an apparent decrease in the amount of cells in G1 phase. Studies of ovarian cells have suggested that 1,25(OH)2D3 causes cell cycle arrest at the G1/S and G2/M checkpoints. In addition, these studies have shown that the proliferation of ovarian cancer OVCAR3 cells is suppressed by 1,25(OH)2D3 (33) and that 1,25(OH)2D3 arrests ovarian cancer cells in G2/M phase by a mechanism that involves GADD45 (39). They have also indicated that 1,25(OH)2D3 arrests ovarian cancer cells in the G1 phase by increasing the abundance of p27, an inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinase activity (40). 1,25(OH)2D3 enhanced the effects of platinum agents by inhibiting the growth of the breast cancer cell line, MCF-7 (41). Additionally, in vivo evidence for the positive interaction between 1,25(OH)2D3 and platinum compounds has been obtained in a murine squamous cell carcinoma model system (42). These studies have shown that 1,25(OH)2D3 causes cell cycle arrest and growth suppression in ovarian cancer cells.

The results of the current study indicated that 1,25(OH)2D3 enhances the growth-inhibitory effect of carboplatin by increasing the rate of apoptosis. Furthermore, 1,25(OH)2D3 induced apoptosis, possibly due to increased ROS production, which directly induces single- and double-strand breaks, abasic sites and DNA fragmentation, all of which lead to apoptosis. Koren et al (43) reported that 1,25(OH)2D3 induces ROS production in MCF-7 cells and suggested a compensatory mechanism in which growth arrest is induced by oxidative stress, while antioxidant activities are increased. 1,25(OH)2D3 was not found to act synergistically with anticancer cytokines in the tumor milieu, which is mediated by ROS (44). In the present study, 10 nM 1,25(OH)2D3 was not found to induce ROS production alone, but to enhance ROS production in ovarian cancer cells treated with carboplatin. These studies have demonstrated that the anticancer activity of 1,25(OH)2D3 is associated with the pro-oxidant action of 1,25(OH)2D3 its in MCF-7 cells, which may be the result of increased intracellular ROS. However, overproduction of ROS through endogenous or exogenous sources may induce DNA damage, the accumulation of which may lead to multistep carcinogenesis (45). Thus, the antioxidative effects of vitamin D have been suggested by epidemiological surveys and numerous in vitro and in vivo laboratory studies (46,47). The antioxidative effect of vitamin D strengthens its roles in cancer chemoprevention and adds to a growing list of the beneficial effects of vitamin D in cancer (48).

One important observation from this study is that 1,25(OH)2D3 enhances the carboplatin-induced apoptosis of ovarian cells and is associated with the loss of MMP. Chen et al (49) also demonstrated that ergocalciferol, vitamin D2, causes HL-60 cell apoptosis via a drop in MMP. 1,25(OH)2D3 has also been found to augment the loss of MMP induced by TNF (50). Another finding has suggested that 1,25(OH)2D3 sensitizes breast cancer cells to ROS-induced death by influencing the caspase-dependent and -independent modes of cell death, upstream of mitochondrial damage (51). Therefore, 1,25(OH)2D3 enhances the anticancer effects of carboplatin through production of ROS and loss of MMP. Other studies have found that 1,25(OH)2D3 induces ovarian cancer cell apoptosis by downregulating telomerase, thus modulating telomere integrity or perhaps via a telomerase-independent mechanism (52). This result also indicates that 1,25(OH)2D3 may induce ovarian cancer cell apoptosis through various mechanisms.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that 1,25(OH)2D3 is a potent inhibitor of ovarian cancer cell growth in vitro, and enhances the therapeutic effects of carboplatin by altering the cell cycle and increasing apoptosis through changes in ROS and MMP. These findings suggest the potential utility of combining 1,25(OH)2D3 with cytotoxic agents for the treatment of ovarian cancer.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Scientific Funding of China (grant nos. 81072286 and 81372979), and in part by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2007. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:43–66. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGuire WP, Hoskins WJ, Brady MF, et al. Cyclophosphamide and cisplatin compared with paclitaxel and cisplatin in patients with stage III and stage IV ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199601043340101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ozols RF, Bundy BN, Greer BE, et al. Gynecologic Oncology Group. Phase III trial of carboplatin and paclitaxel compared with cisplatin and paclitaxel in patients with optimally resected stage III ovarian cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3194–3200. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mutch DG. Gemcitabine combination chemotherapy of ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;90:S16–S20. doi: 10.1016/s0090-8258(03)00339-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ozols RF. Systemic therapy for ovarian cancer: current status and new treatments. Semin Oncol. 2006;33(Suppl 6):S3–S11. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bookman MA, Brady MF, McGuire WP, et al. Evaluation of new platinum-based treatment regimens in advanced-stage ovarian cancer: a Phase III Trial of the Gynecologic Cancer Intergroup. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1419–1425. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stordal B, Pavlakis N, Davey R. A systematic review of platinum and taxane resistance from bench to clinic: an inverse relationship. Cancer Treat Rev. 2007;33:688–703. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Markman M, Webster K, Zanotti K, et al. Survival following the documentation of platinum and taxane resistance in ovarian cancer: a single institution experience involving multiple phase 2 clinical trials. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;93:699–701. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pavelka M, Lucas M, Russo N. On the hydrolysis mechanism of the second-generation anticancer drug carboplatin. Chemistry. 2007;13:10108–10116. doi: 10.1002/chem.200700887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agarwal R, Kaye SB. Ovarian cancer: strategies for overcoming resistance to chemotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:502–516. doi: 10.1038/nrc1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng TC, Manorek G, Samimi G, et al. Identification of genes whose expression is associated with cisplatin resistance in human ovarian carcinoma cells. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2006;58:384–395. doi: 10.1007/s00280-005-0171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rabik CA, Dolan ME. Molecular mechanisms of resistance and toxicity associated with platinating agents. Cancer Treat Rev. 2007;33:9–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberts D, Schick J, Conway S, et al. Identification of genes associated with platinum drug sensitivity and resistance in human ovarian cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:1149–1158. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peters D, Freund J, Ochs RL. Genome-wide transcriptional analysis of carboplatin response in chemosensitive and chemoresistant ovarian cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:1605–1616. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-04-0311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnatty SE, Beesley J, Paul J, et al. ABCB1 (MDR 1) polymorphisms and progression-free survival among women with ovarian cancer following paclitaxel/carboplatin chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:5594–5601. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walters MR. Newly identified actions of the vitamin D endocrine system. Endocrinol Rev. 1992;13:719–764. doi: 10.1210/edrv-13-4-719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saunders DE, Christensen C, Williams JR, et al. Inhibition of breast and ovarian carcinoma cell growth by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 combined with retinoic acid or dexamethasone. Anticancer Drugs. 1995;6:562–569. doi: 10.1097/00001813-199508000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Majewski S, Szmurlo A, Marczak M, et al. Inhibition of tumor cell-induced angiogenesis by retinoids, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and their combination. Cancer Lett. 1993;75:35–39. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(93)90204-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koli K, Keski-Oja J. 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and its analogues down-regulate cell invasion-associated proteases in cultured malignant cells. Cell Growth Differ. 2000;11:221–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evans SR, Shchepotin EI, Young H, et al. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 synthetic analogs inhibit spontaneous metastases in a 1,2-dimethylhydrazine-induced colon carcinogenesis model. Int J Oncol. 2000;16:1249–1254. doi: 10.3892/ijo.16.6.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peterlik M, Grant WB, Cross HS. Calcium, vitamin D and cancer. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:3687–3698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akhter J, Chen X, Bowrey P, et al. Vitamin D3 analog, EB1089, inhibits growth of subcutaneous xenographs of the human colon cancer cell line, LoVo, in nude mouse model. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:317–321. doi: 10.1007/BF02050422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.VanWeelden KV, Flanagan L, Binderup L, et al. Apoptotic regression of MCF-7 xenografts in nude mice treated with the vitamin D3 analog, EB1089. Endocrinology. 1998;139:2102–2110. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.4.5892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mehta RG, Mehta RR. Vitamin D and cancer. J Nutr Biochem. 2002;13:252–264. doi: 10.1016/s0955-2863(02)00183-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chou TC, Talalay P. Quantitative analysis of dose-effect relationships: the combined effects of multiple drugs or enzyme inhibitors. Adv Enzyme Regul. 1984;22:27–55. doi: 10.1016/0065-2571(84)90007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soriano AF, Helfrich B, Chan DC, et al. Synergistic effects of new chemopreventive agents and conventional cytotoxic agents against human lung cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 1999;59:6178–6184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smiley ST, Reers M, Mottola-Hartshorn C, et al. Intracellular heterogeneity in mitochondrial membrane potentials revealed by a J-aggregate-forming lipophilic cation JC-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3671–3675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.9.3671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sung DK, Chang YS, Kang S, et al. Comparative evaluation of hypoxic-ischemic brain injury by flow cytometric analysis of mitochondrial membrane potential with JC-1 in neonatal rats. J Neurosci Methods. 2010;193:232–238. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2010.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turturro F, Friday E, Welbourne T. Hyperglycemia regulates thioredoxin-ROS activity through induction of thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP) in metastatic breast cancer-derived cells MDA-MB-231. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:96. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson JA, Grande JP, Windebank AJ, Kumar R. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D(3) receptors in developing dorsal root ganglia of fetal rats. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1996;92:120–124. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(95)00204-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dokoh S, Donaldson CA, Marion SL, et al. The ovary: a target organ for 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Endocrinology. 1983;112:200–206. doi: 10.1210/endo-112-1-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ahonen MH, Zhuang YH, Aine R, et al. Androgen receptor and vitamin D receptor in human ovarian cancer: growth stimulation and inhibition by ligands. Int J Cancer. 2000;86:40–46. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(20000401)86:1<40::aid-ijc6>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saunders DE, Christensen C, Lawrence WD, et al. Receptors for 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in gynecologic neoplasms. Gynecol Oncol. 1992;44:131–136. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(92)90028-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garland CF, Garland FC, Gorham ED, et al. The role of vitamin D in cancer prevention. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:252–261. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.045260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grant WB. An estimate of premature cancer mortality in the U.S. due to inadequate doses of solar ultraviolet-B radiation. Cancer. 2002;94:1867–1875. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bidoli E, La Vecchia C, Talamini R, et al. Micronutrients and ovarian cancer: a case-control study in Italy. Ann Oncol. 2001;12:1589–1593. doi: 10.1023/a:1013124112542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salazar-Martinez E, Lazcano-Ponce EC, Gonzalez Lira-Lira G, et al. Nutritional determinants of epithelial ovarian cancer risk: a case-control study in Mexico. Oncology. 2002;63:151–157. doi: 10.1159/000063814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moffatt KA, Johannes W, Miller GJ. 1Alpha,25dihydroxyvitamin D3 and platinum drugs act synergistically to inhibit the growth of prostate cancer cell lines. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:695–703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang F, Li P, Fornace AJ, Jr, et al. G2/M arrest by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in ovarian cancer cells mediated through the induction of GADD45 via an exhonic enhancer. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:48030–48040. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308430200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li P, Li C, Zhao X, et al. p27(Kip1) stabilization and G(1) arrest by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) in ovarian cancer cells mediated through down-regulation of cyclin E/cyclin-dependent kinase 2 and Skp1-Cullin-F-box protein/Skp2 ubiquitin ligase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:25260–25267. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311052200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cho YL, Christensen C, Saunders DE, et al. Combined effects of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and platinum drugs on the growth of MCF-7 cells. Cancer Res. 1991;51:2848–2853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Light BW, Yu W, McElwain MC, et al. Potentiation of cisplatin antitumor activity using a vitamin D analogue in a murine squamous cell carcinoma system. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3759–3764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koren R, Hadari-Naor I, Zuck E, et al. Vitamin D is a prooxidant in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1439–1444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wiseman H. Vitamin D is a membrane antioxidant. Ability to inhibit iron-dependent lipid peroxidation in liposomes compared to cholesterol, ergosterol and tamoxifen and relevance to anticancer action. FEBS Lett. 1993;326:285–288. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81809-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Poulsen HE, Prieme H, Loft S. Role of oxidative DNA damage in cancer initiation and promotion. Eur J Cancer Prev. 1998;7:9–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marchionatti AM, Picotto G, Narvaez CJ, et al. Antiproliferative action of menadione and 1,25(OH)2D3 on breast cancer cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2009;113:227–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koren R, Rocker D, Kotestiano O, et al. Synergistic anticancer activity of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) and immune cytokines: the involvement of reactive oxygen species. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2000;73:105–112. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(00)00068-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bao BY, Ting HJ, Hsu JW, Lee YF. Protective role of 1 alpha, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 against oxidative stress in nonmalignant human prostate epithelial cells. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:2699–2706. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen WJ, Huang YT, Wu ML, et al. Induction of apoptosis by vitamin D2, ergocalciferol, via reactive oxygen species generation, glutathione depletion, and caspase activation in human leukemia cells. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:2996–3005. doi: 10.1021/jf0730744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weitsman GE, Ravid A, Liberman UA, Koren R. Vitamin D enhances caspase-dependent and independent TNF-induced breast cancer cell death: the role of reactive oxygen species. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;1010:437–440. doi: 10.1196/annals.1299.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weitsman GE, Koren R, Zuck E, et al. Vitamin D sensitizes breast cancer cells to the action of H2O2: mitochondria as a convergence point in the death pathway. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;39:266–278. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jiang F, Bao J, Li P, et al. Induction of ovarian cancer cell apoptosis by 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 through the down-regulation of telomerase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:53213–53221. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410395200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]