Abstract

The nematode Caenorhabditis. elegans has served as a fruitful setting for cell death research for over three decades. A conserved pathway of four genes, egl-1/BH3-only, ced-9/Bcl-2, ced-4/Apaf-1, and ced-3/caspase, coordinates most developmental cell deaths in C. elegans. However, other cell death forms, programmed and pathological, have also been described in this animal. Some of these share morphological and/or molecular similarities with the canonical apoptotic pathway, while others do not. Indeed, recent studies suggest the existence of an entirely novel mode of programmed developmental cell destruction that may also be conserved beyond nematodes. Here we review evidence for these noncanonical pathways. We propose that different cell death modalities can function as backup mechanisms for apoptosis, or as tailor-made programs that allow specific dying cells to be efficiently cleared from the animal.

Keywords: cell death, apoptosis, necrosis, linker, elegans, morphology

1. INTRODUCTION

Cell death, programmed or otherwise, is a ubiquitous biological phenomenon. Programmed cell death is required for development, homeostasis, and the response to pathological insults in virtually all animals, from sponges to humans[1]. In humans, disease processes are often accompanied by either causal or incidental cell death[2]. Thus, a broad understanding of cell death programs may yield insights into, and possibly treatments for, human pathologies.

The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans has proven to be an invaluable tool for dissecting programmed cell death mechanisms. Several aspects of this organism make it well suited for cell death research. Like other nematodes, C. elegans has an essentially invariant cell lineage[3], where death features prominently as a common fate. Dying cells are easy to observe in intact, developing animals, which are small and possess a transparent cuticle. Simple genetics and animal husbandry[4], efficient RNA interference[5], and a fully sequenced and heavily annotated genome[6] have enabled investigators to identify genes involved in the control and execution of developmental programmed cell death and to uncover mutations and conditions leading to pathological cellular demise.

A molecular description of apoptotic cell death emerged from studies of C. elegans in the 1980s and 90s. Horvitz and colleagues identified mutants that define four core apoptotic genes [7]: the BH3-only-like gene egl-1, the Bcl-2-like ced-9, the Apaf-1-like ced-4, and the caspase ced-3[8]. Mutations in these genes abolish the death of almost all cells fated to die, and their roles in cell death are largely conserved in all metazoans examined. Most somatic C. elegans cells destined to die specifically induce egl-1 transcription[9]. EGL-1 protein then binds to CED-9[10], disrupting its interaction with CED-4[11,12], thereby freeing CED-4 to activate CED-3, promoting cell death[7,13].

Despite the great success of these early genetic studies, which relied on tracking the survival of groups of cells, they did not initially identify programs unique to individual cells. Partially redundant pathways would have also been more difficult to detect, as mutations in individual components would likely yield only weak defects. Later genetic screens in many labs, seeking mutations affecting the deaths of individual or small groups of cells, uncovered new forms of cell death that deviate partially or entirely from the canonical molecular pathway for apoptosis. Here we discuss these recent studies.

2. PATHOLOGICAL CELL DEATH INDUCED BY GENOME LESIONS AND ENVIRONMENTAL STRESS

2.1 ION CHANNEL MUTATIONS

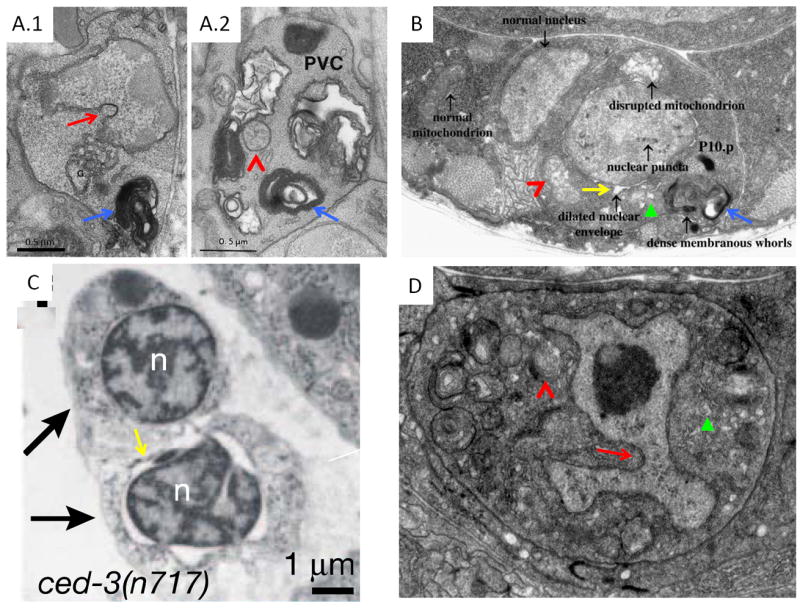

Genetic studies in C. elegans identified three proteins, MEC-4[14], DEG-1[15], and UNC-8[16], whose activation by gain-of-function mutations inappropriately promotes neuronal death. Electron microscope reconstructions demonstrate that dying neurons accumulate progressively larger vacuoles and electron-dense membranous whorls, as well as what appear to be nuclear chromatin clumps. Changes in nuclear shape are also evident (Fig. 1.A) [17]. Late in the process, organelle swelling and lysis can be seen.

Figure 1.

Different cell death pathways share morphological features. A. PVM neuron (A.1) of a mec-4(gf) mutant and PVC neuron (A.2) of a deg-1(gf) mutant, Reproduced with permission from [17]. B. P10.p cell in a lin-33(gf) animal. Reproduced with permission from [47]. C. Shed cells (arrows) in a ced-3(n717) embryo. Reproduced with permission from [56]. D. Dying linker cell. Reproduced with permission from [90]. Nuclear indentations, red arrows. Membranous whorls, blue arrows. Dilated ER, green arrowheads. Dilated nuclear envelope, yellow arrows. Dilated mitochondria, red carrats. Dark intranuclear structure in D is the linker cell nucleolus.

The three affected proteins are ENaC-type cation channels, the so-called degenerins, that conduct predominantly sodium[18], but also calcium[19], and cell death inducing mutations increase their open channel probability [20]. Thus, abnormal ion homeostasis is likely the initiating insult that leads to cell swelling and death. Gain-of-function mutations in the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor DEG-3[21], another cation channel, also have similar effects.

While the mechanistic details of this pathological cell death process are still not entirely worked out, a prominent role for intracellular calcium release has been suggested. Mutants in the C. elegans homolog of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) calcium-binding chaperone, calreticulin, attenuate MEC-4(gf)-mediated neuronal cell death[22]. Similarly, mutations in calnexin, another ER calcium-binding protein, in ITR-1, the C. elegans ER IP3 receptor, and in the ryanodine receptor ER release channel, UNC-68, also attenuate cell death (Fig. 2), as does the calcium chelator EGTA. Cell death can be restored in these suppressed animals by thapsigargin, which blocks the ER calcium influx pump and causes calcium release from the ER. Thapsigargin treatment also results in occasional cell death in wild-type animals, suggesting that cytosolic calcium elevation may be sufficient to promote cell death. Consistent with this idea, the deg-3(gf) mutations, which likely cause cytosolic calcium increase without the need for additional ER calcium, cannot be suppressed by mutations that block ER calcium release[22]. Additionally, heat shock is also able to induce calcium-dependent necrosis, perhaps by denaturing crucial regulators of calcium homeostasis[23].

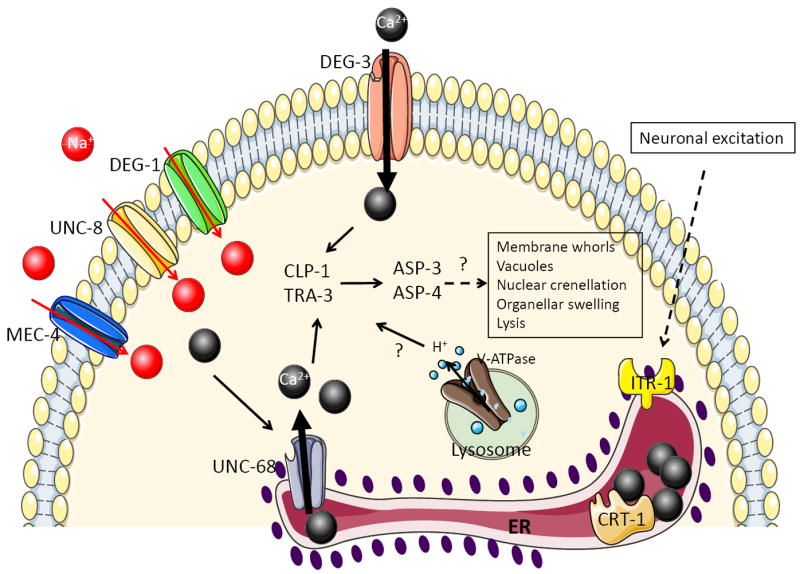

Figure 2.

Mechanisms of ion channel mutation induced death in C. elegans.

While calcium has many functions in the cell, its requirement for the activation of cytosolic calpain and cathepsin proteases may play at least some role in cell degeneration[24]. Overexpression of these proteases is sufficient to cause death with similar morphology, and RNAi-mediated knockdown of the calpains CLP-1 and TRA-3, or the cathepsins ASP-3 and ASP-4 inhibits cell death progression in mec-4(gf) mutants. While double calpain or double cathepsin knockdowns enhances cell survival in this background, reducing expression of one of each does not, suggesting that calpains and cathepsins might function in a linear pathway in which elevated cytosolic calcium activates calpains, which, in turn, promote cathepsin activation and cell demise (Fig. 2). However, this model has not been rigorously tested.

Several other cytoplasmic cathepsins exist in C. elegans that do not seem to affect activated-channel induced neuronal death. Whether this requirement for select proteases reflects cell-type-specific expression of these proteins or substrate specificity is not clear.

Calcium may not be the only ion involved in degenerin-induced cell death. Mutations in subunits of the vacuolar-H+-ATPase (V-ATPase) ameliorate both degenerin-mediated and thapsigargin-induced death[25], suggesting that cytosol acidification could function downstream of calcium elevation to promote cell death (Fig. 2). Treating C. elegans with weak lysotropic bases or impairing lysosomal biogenesis can also attenuate calcium-dependent cell death, suggesting a possible role for this organelle in cytosol acidification [26]. How protons may affect cytosolic protease activation, if at all, is not known, but lysosomes might also contribute to cellular demise by leaking their normally sequestered acid hydrolases into the cytoplasm.

Neuronal cell death accompanied by cell swelling can also be induced in C. elegans by constitutive activation of the Gαs protein [27,28], which functions through the adenylyl cyclase ACY-1 to transmits signals from metabotropic neurotransmitter receptors. This death is weakly dependent on the voltage-gated calcium channel subunit UNC-36 and on the vesicular glutamate transporter EAT-4[27], suggesting that neuronal activity may modulate sensitivity to pathological cell death. Indeed, deletion of the C. elegans glutamate transporter glt-3, which presumably leads to higher extracellular glutamate levels, cooperates with Gαs overexpression to enhance neuronal cell death[29].

The studies of degenerative cell death in C. elegans neurons raise the possibility that similar processes contribute to human nervous system pathologies. For example, as in C. elegans, neuronal cell death induced in a mouse stroke model depends on both calcium and low pH. However, in this system, acid seems to function upstream of calcium release[30]. Glutamate-induced toxicity, thought to be an important facet of cell death induction in stroke, may also promote cell death through neuronal second messengers[31].

2.2 NAD METABOLISM DEFECTS

While neuronal cell death has featured prominently in studies of degenerative cell death in C. elegans, the degeneration of non-neuronal cells in response to specific gene mutations has also been described. In pnc-1 mutant larvae, the uterine uv1 cells die with a vacuolated morphology through a process requiring calpains and aspartyl proteases[32]. Cell death seems to be a response to overabundance of nicotinamide (NAM), which PNC-1, a nicotinamidase homolog, converts to nicotinic acid. Indeed, feeding animals NAM also promotes uv1 vacuolation and death[33]. Why uv1 cells are sensitive to NAM accumulation is not understood. One possibility is that NAM levels alter the generation and/or function of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD), a key respiration intermediate. However, muscle cells whose energy requirements are likely much higher, remain intact in pnc-1 mutants[33]. Boosting EGF signaling, which promotes uv1 specification, suppresses cell death, suggesting that an EGF-repressible NAD consumer, or its product, may be involved. However, if and how such an NAD consumer causes calpain and/or aspartyl protease activation is unclear.

How vacuoles accumulate within neuronal or non-neuronal C. elegans cells undergoing degenerative cell death is not well understood. Notably, expressing human caspase-3 in C. elegans body wall muscle can promote vacuole formation in these cells as well, rather than the more classical, refractile appearance induced in other cells[34]. Thus, it is possible that both apoptotic and degenerative cell death regulators in C. elegans engage common targets. Identification of such targets would be required to confirm this idea.

2.3 CELL DIFFERENTIATION MUTATIONS

In vertebrates and in Drosophila, cell death is often induced in response to a failure in cell fate specification or differentiation[35], perhaps as a result of disturbances in proteostasis[36,37]. This may also be the case in C. elegans. For example, LIN-26, a Zn-finger transcription factor, normally promotes hypodermal and glial cell fate. A reduction-of-function mutation in this gene results not only in excess neuron production, but also in vacuolation and death of hypodermal and glial cells[38]. While the mechanism promoting cell demise in this case is not known, it is independent of the ced-3 caspase (M. Labouesse, personal communication).

Developmental failure also seems to lead to cell death in animals carrying mutations in the unc-83 and unc-84 genes, which encode KASH and SUN domain proteins, respectively, that anchor the nucleus to the cytoskeleton[39]. In these mutants, nuclei of the P epithelial blast cells fail to migrate ventrally along with the rest of the cell body, resulting in elongated cells that eventually die in a ced-3-independent manner[40,41]. Unlike hypodermal cell death in lin-26 mutants, dying cells in unc-83/84 mutants are not vacuolated, instead adopting a refractile appearance common to naturally dying cells in C. elegans. Double mutants of unc-84 and genes that block P cell migration do not exhibit P cell death[40]. Furthermore, failure of nuclear migration is not generally lethal to cells, since, in unc-83 mutants, other cells exhibit nuclear migration failure without death[41]. These observations suggest that the disconnect between cell migration and nuclear migration must trigger a cell-specific response that leads to death. Genetic screens for cell death suppressors could reveal the key players in this pathological process, and should reveal whether it is possible to interrupt cell death without restoring nuclear migration.

While cell death in response to failed differentiation in C. elegans is ced-3-independent, and likely caspase independent, this is not the case in other animals[42-45]. The source of this difference is not clear, but suggests that at least in somatic cells in C. elegans, caspases and other apoptotic genes respond mainly to programmed stimuli. C. elegans germ cells can engage caspases in response to irradiation and other DNA lesions[46], suggesting that damage responses in this tissue may be more akin to generalized responses in vertebrates.

2.4 lin-24/lin-33 MUTANTS

Dominant mutations in two genes, lin-24 and lin-33, promote the inappropriate deaths of Pn.p cells, daughter cells of the P cells affected by unc-83 and unc-84 mutations[47]. Dying cells assume a refractile, non-vacuolated appearance under Differential Interference Contrast (DIC) optics. Electron microscopy revealed that dying cells exhibit electron-dense nuclear puncta, but otherwise normal nucleoplasm, dilation of the nuclear envelope, dense membranous cytoplasmic whorls, and disrupted mitochondria (Fig 1.B). Some dying cells can recover and reacquire normal morphology, while others can recover but possess a small nucleus. Pn.p cell fate is also affected in these mutants, but whether fate changes result from developmental cues missed because of injury or are independent defects is not clear.

Programmed cell death in C. elegans is usually an all-or-none process, however, recovery from death is also seen in animals doubly mutant for weak mutations in ced-3 and genes promoting apoptotic cell corpse engulfment. In these animals, progeny of Pn.p cells begin to undergo normal developmental cell death, acquire a refractile appearance, only to recover and inappropriately survive[48]. This phenomenon is only seen in engulfment mutant backgrounds, demonstrating that engulfment can modulate cell susceptibility to death. Indeed, one C. elegans cell, B.al/rapaav, always survives in engulfment-defective mutants, despite additional dependence on ced-3 caspase activity for death[48], and, rarely, cells in animals lacking all four C. elegans caspase-related genes die and are engulfed[49], hinting perhaps at a role for engulfment in cell death. Remarkably, cell death in dominant lin-24/33 mutants can also be attenuated by mutations in engulfment genes[47]. While ced-3 caspase does not seem to play a role in lin-24/33 mediated cell death, mutations in egl-1/BH3-only and ced-4/Apaf-1 weakly interfere with the process. The sites of action of lin-24/33 or any of the modifying genes in the context of Pn.p cell death are not known.

Deleting lin-24, lin-33, or both has no obvious effects on C. elegans development, or cell survival. However, loss of function of either gene prevents Pn.p cell death by dominant mutations in the other, suggesting that the encoded proteins may function in a complex. LIN-24 protein contains a domain similar to bacterial toxins, and both loss- and gain-of-function alleles alter this conserved domain[47]. The predicted LIN-33 protein does not resemble other known genes. Bacterial toxins homologous to LIN-24 kill eukaryotic cells by forming oligomeric pores in the plasma membrane, a mechanism shared with the membrane attack complex of the vertebrate blood complement system[50] as well as with the perforins of cytotoxic T lymphocytes and NK cells[51]. One possibility, therefore, might be that LIN-24/33 mutant proteins are inappropriately released from neighboring cells to promote Pn.p cell death by poking holes in their membranes. Engulfment mutants might suppress death by preventing contact between Pn.p cells and their killer neighbors. It is equally plausible that LIN-24/33 function in the dying cell to introduce membrane pores, and that engulfing cells, sensing membrane perturbations, finish off the weakened Pn.p cells.

2.5 A LATENT APOPTOTIC PATHWAY IN Pn.p CELLS?

That apoptotic genes modulate lin-24/33 dependent Pn.p cell death suggests that this death process may be mechanistically related to apoptosis. Support for this notion comes from studies of loss-of-function mutations in the gene pvl-5. Animals carrying such mutations exhibit inappropriate Pn.p cell death, which occurs at the same developmental time as lin-24/33-mediated deaths. Dying cells in pvl-5(lf) animals can recover, and recovered cells frequently exhibit an ovoid morphology and shrunken nucleus as in lin-24/33 mutants[52]. Intriguingly, pvl-5-mediated cell death requires ced-3 caspase and can be suppressed by ced-9(gf) mutations, suggesting inappropriate initiation of an apoptosis-related pathway in Pn.p cells.

Nonetheless, pvl-5 and lin-24/33 mediated Pn.p cell deaths are not identical. pvl-5 mutations can cause Pn.p cell vacuolation not reported in lin-24/lin-33 mutants. Moreover, the cell fate defects resulting from the two lesions are likely to be different: lin-24/33 mutants lack the hermaphrodite vulva, which is normally generated by Pn.p cell descendents, whereas pvl-5 mutants exhibit a protruding vulva defect. Furthermore, while lin-24/lin-33-mediated death is weakly suppressed by mutations in all core cell death genes except for ced-3, pvl-5(lf)-mediated Pn.p cell death is suppressed by ced-9(gf), but not by egl-1 or ced-4 loss-of-function mutations. Finally, pvl-5 mutants suffer a small number of ced-3-dependent ectopic cell deaths in cells other than the Pn.p cells, a defect not reported for lin-24/33 mutants. The molecular identity of the pvl-5 gene is not known, but it maps to a different chromosome from lin-24 and lin-33. How pvl-5 regulates ced-3 function is also not understood.

In Pristionchus pacificus and other nematodes more distantly related to C. elegans, some or all Pn.p cells that are not destined to contribute to vulva formation die by ced-3-dependent apoptosis[53,54]. All Pn.p cells have the capacity to die in Pristionchus, as mutants in the Hox gene Ppa-lin-39 are vulvaless because all Pn.p cells die. Cell death is blocked, and vulva formation is restored in animals also carrying Ppa-ced-3 mutations. A genetic screen for Ppa-lin-39 suppressors recovered 22 alleles of Ppa-ced-3, but only two alleles of other genes. This may suggest that in Pristionchus Pn.p cells, ced-3 caspase is the main cell death effector, a profile resembling that of pvl-5-induced cell death, although differences in gene mutability could also account for this mutational profile.

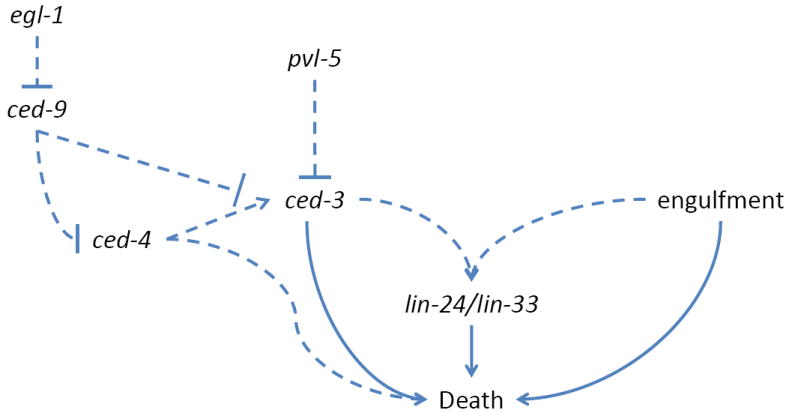

Taken together, these studies suggest that C. elegans lin-24/33 and pvl-5 mutations may uncover a silenced apoptotic program that is still functional in other nematodes (Fig. 3). However, the differential requirement for ced-3 and ced-4 in these death processes remains puzzling. RNAi against icd-1, the beta subunit of the nascent polypeptide associated complex (β-NAC), causes widespread ectopic cell death during C. elegans development[55]. As in lin-24/33 mutants, loss of ced-4, but not of ced-3, suppresses icd-1(RNAi)-mediated death, and other C. elegans caspases play only minor roles in this process[49]. One must, therefore, entertain the possibility that ced-4 can promote cell death in the absence of caspases.

Figure 3.

Possible Pn.p cell death pathways in Pn.p cells. Dashed arrows indicate tentative relevant genetic interactions.

2.6. CELL SHEDDING IN CASPASE MUTANTS

In embryos lacking all four C. elegans caspases, six cells are shed from the anterior sensory depression and the ventral pocket[56]. These cells express egl-1, but are still shed in egl-1(lf), ced-9(gf), and ced-4(lf) mutants as well. In wild-type embryos, shed cells die normally and are engulfed by neighboring cells. Mutations in the MELK kinase PIG-1 and in its activating kinase PAR-4/LKB1 prevent shed cell accumulation. These observations have led to the hypothesis that cell shedding is a cell death program that functions in parallel to CED-3 caspase, perhaps as a backup program, and that PIG-1 is a key activator of this program. Perhaps the strongest evidence in favor of this model is that shed corpses exhibit some features reminiscent of apoptosis (Fig. 1.C).

Cell shedding does not appear to take place in wild-type animals and pig-1 expression is not sufficient to promote cell death. These and other results have raised the possibility that cell shedding may not be a cell death program per se, but a passive result of ced-3 caspase loss[57]. The transcriptome of dying cells may be under reduced selective pressure, and, if so, dying cells may be poorly differentiated. Indeed, while inappropriately surviving cells in ced-3 mutants can acquire fates of their sister cells or their progeny, differentiation reporters are weakly expressed in many of these surviving cells[7], and fate acquisition is often incomplete[58]. It is possible, therefore, that in ced-3 mutants, these six inappropriately surviving cells have poor expression of cell adhesion proteins, and are passively extruded from the animal in response to movements of adjacent cells. pig-1 mutations could, in this model, enhance the differentiation of the “undead” cells towards their adhesive sister cell fate, thereby preventing shedding. PIG-1 has been implicated in the control of asymmetric cell division[59,60] and plays important roles in cell fate specification throughout the embryo[61]. In the context of cell shedding, pig-1 mutants inappropriately express the α-catenin HMP-1 on the surface of would-be shed cells, and one of these cells expresses reporters specific for its sister cell progeny, the excretory cell[56].

If pig-1 does regulate a novel cell death process, the expectation would be that its role and its targets in all dying cells be the same. Whether this is the case is unclear, however, pig-1 mutations also affect the death and specification of the sister cell of the M4 pharyngeal neuron[62], and this cell is not shed and remains adhesive in ced-3 mutants[58].

3. DEVELOPMENTAL CELL DEATHS THAT DO NOT FOLLOW THE CANONICAL APOPTOTIC PATHWAY

3.1 GERMLINE CELL DEATH

In adult C. elegans hermaphrodites, about half of female germ cells die by apoptosis before developing into mature oocytes[63]. Unlike dying somatic cells, whose identities are invariant, germ cells, which occupy a syncytium and appear identical, seem to die stochastically. Competence to die is imparted by ephrin and Ras/MAPK signaling, probably originating from surrounding sheath cells, resulting in germ cell exit from meiotic pachytene[64,65].

While germline cell death requires ced-3, ced-4, and ced-9, it is independent of egl-1 and is not blocked by a gain-of-function mutation in ced-9 that prevents somatic cell death[63]. Mutations in the Pax2-related genes egl-38 and pax-2 promote excess germ cell death. Genetically, egl-38 and pax-2 seem to function upstream of ced-9, a model supported by the observation that EGL-38 and PAX-2 proteins bind to regulatory sequences near the ced-9 gene. It is therefore possible that in the germline, Pax2 proteins substitute for EGL-1. Nonetheless, in the soma, egl-1 transcription is induced in dying cells. This does not seem to be the case for egl-38 and pax-2[66], suggesting that these genes may act permissively to set ced-9 levels in germ cells. Thus, other inputs into the apoptotic pathway may control the decision to promote germ cell death. The involvement of genes acting in gonadal sheath cells in germ cell death competence[67,68] raises the possibility that regulation of germ cell death could have cell-autonomous and non-autonomous components, which would allow the animal to make decisions about germ cell death based on both the overall state of the animal[69-73] as well as the integrity of individual germ cell genomes[74].

3.2 TAIL-SPIKE CELL DEATH

The genetic requirements for germ cell death are mirrored, in part, in the C. elegans tail-spike cell. This binucleate cell, which arises by cell fusion, sends a slender posterior process that seems to serve as a scaffold for molding the C. elegans tail. ced-3 and ced-4 are absolutely required for tail-spike cell death, but egl-1 plays only a minor role, and a gain-of-function mutation in ced-9 has no effect[75]. Studies of ced-3 transcription revealed that its expression is induced in the tail-spike cell about 25 minutes before morphological signs of cell death are apparent. The homeodomain transcription factor PAL-1 promotes ced-3 expression in the tail-spike cell by binding to three redundant sites upstream of the ced-3 gene. These results suggest that transcriptional induction of ced-3, and not of egl-1, may be the key regulatory event promoting tail-spike cell death.

Additional layers of control also exist. A recent study demonstrated that tail-spike cell death requires the F-box protein DRE-1. Genetic and molecular evidence supports the idea that DRE-1 functions in a Skp/Cullin/F-box (SCF) complex in parallel to EGL-1 and likely upstream of CED-9. An attractive model is that DRE-1 substitutes for EGL-1 by inactivating CED-9 through ubiquitination and degradation, thereby creating a permissive environment for newly translated CED-3. Support for this model comes from studies of human FBX010 and BCL2, proteins similar to DRE-1 and CED-9, respectively. In a subset of B-cell lymphomas, FBX010 expression can promote BCL2 degradation. Furthermore, in these same lines, FBX010 expression promotes cell death[76].

Mutations in FBX010 are found in some patients with B-cell lymphomas, and expression of the gene is reduced in many others. Furthermore, RNAi against FBX010 in tumor cells promotes their survival[76]. These results suggest that FBX010 may function as a tumor suppressor gene. Mutations in Cdx2, the human homolog of C. elegans pal-1 promote intestinal tumors[77], suggesting that this gene is a tumor suppressor as well. These observations raise the intriguing possibility that while tail-spike cell death control exhibits non-canonical features in C. elegans, similar regulatory mechanisms may play integral roles in controlling tumorigenesis in humans.

3.3 SEX-SPECIFIC DEATH OF CEM NEURONS

The sexually dimorphic CEM cells survive in males, differentiating into neurons that help orchestrate the male’s complex mating behavior[78]. In hermaphrodites, which do not exhibit this behavior, the neurons die[79]. CEM cell death requires all four core cell death genes. Yet, as in the germline and tail-spike cells, CEM cell death regulation appears to require transcriptional activation of the ced-3 caspase gene. Although egl-1 expression is still induced in CEM neurons, this induction is not always sufficient to promote CEM death. In males carrying mutations in unc-86, a gene encoding a POU homeodomain transcription factor, egl-1 expression is unaltered, but CEMs fail to die. Genetics and expression studies revealed that UNC-86 protein, LRS-1, a tRNA synthetase, and UNC-132, a novel protein, control CEM demise by promoting ced-3 transcription [80,81]. Nonetheless, whether ced-3 or egl-1 transcription is the rate-determining step in CEM cell death remains unclear.

ced-3 transcription in CEMs seems to be counteracted by CEH-30, a BarH1-related transcription factor. CEH-30 functions genetically downstream of egl-1 and ced-9[80,82]. A ceh-30 gain-of-function allele alters an intronic consensus sequence for binding by TRA-1A, a Gli-related protein that is an effector of the sex determination machinery promoting hermaphrodite identity[83,84]. This observation suggests that TRA-1A normally represses ceh-30 in hermaphrodites.

CEM neurons and the tail-spike cell survive for an extended duration after they are generated and before succumbing to cell death. Likewise, both cell types actively control transcription of ced-3. This correlation raises the possibility that in these long-lived cells destined to die, there is a need to replenish CED-3 protein to promote cell death. Indeed, ced-3 transcriptional reporter studies suggest that while the gene is widely expressed, its transcription is mainly confined to early embryogenesis[85], before most cell death takes place. Thus, cells that are longer lived may need to re-express the gene to promote their demise.

3.4 THE USE OF ALTERNATE CASPASES IN DYING CELLS

The C. elegans genome contains three caspase-encoding genes in addition to ced-3: csp-1, csp-2, and csp-3[86]. While CSP-1 protein has caspase activity in vitro[86], and its overexpression can promote cell death in C. elegans[49], neither csp-2 nor csp-3 seem to encode catalytically active enzymes. CSP-2 has a catalytic cysteine, but lacks conserved residues surrounding the active site, and CSP-3 lacks the large caspase subunit and its active site.

csp-1 may play a minor role in somatic cell death. While mutants in the gene have no obvious cell death defects, enhanced cell survival is observed in conjunction with weak mutations in ced-3 caspase[49]. Enhancement is cell-specific, as only some cells destined to die, such as the sister of the pharyngeal M4 neuron, are affected. The activity of CSP-1 does not appear to be regulated by CED-4, as ced-4 lesions do not inhibit ectopic cell death mediated by CSP-1. It seems, therefore, that if CSP-1 has a role in cell death, it may respond to different cues than CED-3.

Loss-of-function mutations in the csp-2 and csp-3 genes have been reported to enhance cell death in the germline[87] and soma[88] respectively, although this observation has been challenged[49]. A suggested mechanism for these effects is that these caspase-related proteins bind CED-3 or CSP-1 to inhibit their activities[87,88]. However, given the weak cell death effects of mutants in these genes, testing models regarding their activities remains challenging.

5. NON-APOPTOTIC, CASPASE-INDEPENDENT LINKER CELL DEATH

The male-specific linker cell leads the developing male gonad on a stereotyped elongation path and, upon its death, permits the lumen of the vas deferens to fuse with the cloaca to allow sperm exit[89]. Linker cell death is independent of all C. elegans caspases and other apoptotic cell death genes[7,49,90], and also seems to proceed independently of genes controlling apoptotic cell engulfment and proteases involved in other cell death forms in C. elegans[90]. While linker cell death was initially thought to proceed non-autonomously, through engulfment by the U.l/rp cell[79,89], recent studies demonstrate important cell autonomous components involved in the process[90,91].

Consistent with the unique genetic requirements, dying linker cells are morphologically distinct from apoptotic cells in which chromatin condensation and cytoplasmic shrinkage are generally evident. Dying linker cells maintain open chromatin, and display progressive nuclear envelope crenellation leading to formation of a flower-shaped nucleus never observed outside this setting in C. elegans. Mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) swelling is also observed (Fig 1.D)[90].

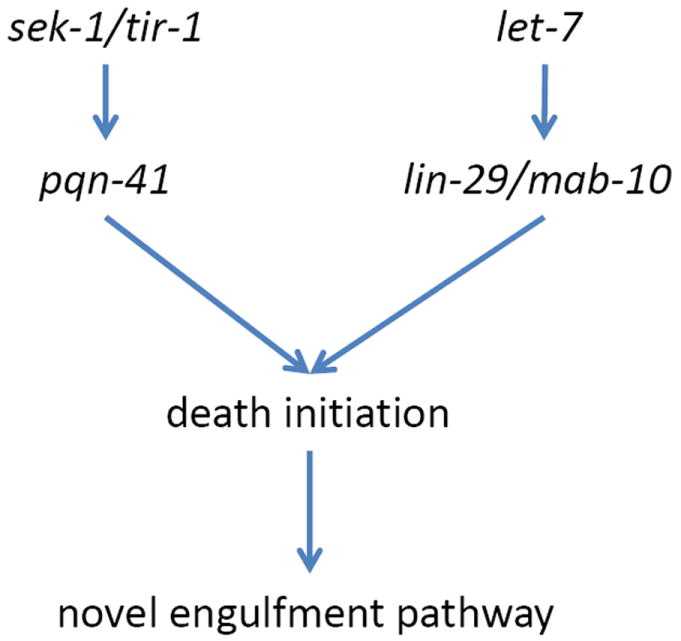

The death of the linker cell requires both temporal and spatial cues. Mutations in the microRNA gene let-7 and the Zn-finger transcription factor gene lin-29 block linker cell death. These genes are components of a developmental timing program, the heterochronic pathway, that communicates the developmental stage of animals to individual cells within the animal. LIN-29 functions together with the MAB-10 transcriptional cofactor[92], and both proteins are present in the nucleus of the linker cell during its migration and death (Fig. 4). Mutation in the him-4 gene, encoding a secreted immunoglobulin family member, reroute the linker cell migration path, so that cells often end up in the head, instead of the tail. While most linker cells die on time even in the head, about 13% of him-4 mutants exhibit linker cell survival, suggesting that local spatial cues may be important for linker cell death. Our recent studies suggest a role for Wnt signaling in transducing such a spatial cue, (M. Kinet and S. Shaham, unpublished observations).

Figure 4.

Genetics of linker cell death. Arrows, plausible genetic interactions.

Dying linker cells morphologically resemble cells that die during normal vertebrate development. For example, approximately half of the cells initially present in the developing chick ciliary ganglion die during development. Electron microscopy fails to reveal apoptotic features in dying cells., but does uncover cells with swollen mitochondria and ER[93]. Nuclear crenellation can also be observed in these cells, becoming more pronounced when ganglion neurons are deprived of their target organ[93]. Developmental death of spinal motor neurons proceeds, slowed but unabated, in the absence of caspase-3 or caspase-9, and dying cells exhibit open chromatin, swollen ER and mitochondria, and cytoplasmic vacuolation[94]. Crenellated nuclei and swollen ER and mitochondria are also observed in dying neurons of patients with poly-glutamine expansion diseases, such as Huntington’s disease and some spinocerebellar ataxias, as well as in mouse models for those disease[91]. Strikingly, the gene pqn-41, which encodes a protein containing a 427 amino-acid C-terminal domain rich in glutamines, is required for linker cell death. pqn-41 seems to function in the same pathway as the conserved MAPKK SEK-1 and its adapter protein TIR-1 to promote linker cell death (Fig. 4) [91]. pqn-41 is not required for other cell deaths in C. elegans, and ectopic expression of the rescuing PQN-41C isoform does not precociously kill the linker cell or other cells, suggesting that it must function with other components to promote linker cell death.

Recently, the TIR-1 homologs dSarm and Sarm have been implicated in distal neurite degeneration following axotomy in Drosophila and mice, respectively[95]. That the same protein promotes degenerative processes in all three species is intriguing, and bolsters the possibility of a connection between linker cell death and cell death processes in humans. Further, excitotoxic injury to mouse retinal ganglion cells induced by kainate treatment also requires Sarm[96], suggesting mechanistic commonalities between excitotoxic necrotic death and other degenerative deaths that may explain some of the observed morphological parallels . Nonetheless, it is still too early to tell whether the morphological and molecular similarities between linker cell death, normal vertebrate cell death, polyglutamine-mediated cell death, and axon degeneration represent true conservation or happenstance.

Why does the linker cell not die by apoptosis? The cell is larger than other cells that succumb to apoptosis and likely harbors extensive functional machinery required for its long migration and the concomitant morphological stages through which it must progress[97]. For these reasons, the linker cell might require an alternate program to deal with its degradation. A similar idea has been invoked for the degeneration of Drosophila salivary glands, although in this case cell death remains caspase-dependent[98]. Alternatively, the linker cell death program may ensure that the cell will be engulfed by a specific phagocyte. Supporting this idea, the engulfment of dying linker cells is independent of genes required for apoptotic corpse engulfment[90]. Furthermore, the engulfing U.l/rp cell does not cluster CED-1∷GFP at membranes making contact with the linker cell, as is the case for apoptotic cells. CED-1∷GFP does surround mistargeted dying linker cells in him-4 mutants, suggesting that the cell can be engulfed by this mechanism, and that other cells may not express the physiological engulfment program utilized by the U.l/rp cells. Mistargeted him-4 cell corpses often persist much longer than wild-type corpses[90], suggesting that the ced-1-mediated engulfment process used at these locations is not as efficient as the physiological program engulfing the dying linker cell. Supporting this notion, CED-1∷GFP surrounding mistargeted linker cell corpses can be incomplete[90], a phenomenon never seen in apoptotic corpse engulfment but reminiscent of the incomplete engulfment seen in ced-1 mutants[99]. Corpses of cells in animals with ablated U.l/rp cells also persist in the terminal vas deferens (M. Abraham and S. Shaham, unpublished observations), appearing to block sperm exit, suggesting that terminal vas deferens cells are not competent for engulfment using either canonical or linker cell processes.

The cell-specific competence for expressing the physiological engulfment program combined with the selective efficiency between specific death and engulfment programs suggests a strategy for targeting specific cells to specific phagocytes. Such a strategy may have specific anatomical imperatives in the worm, but, in animals with cellular immune systems, it is the rule rather than the exception.

6. CONCLUSION

C. elegans has been appropriately lauded as a system for studying programmed cell death, as studies in this organism laid the foundations for understanding the conserved process of apoptosis. C. elegans has also been used to study cell death induced by environmental toxicants[100,101], excellent studies in their own right with clear relevance to humans but outside of the scope of our present discussion. Here we have reviewed experiments suggesting that this animal still has much to offer in the context of programmed cell death research. From the identification of a novel morphologically conserved developmental cell death program, to the characterization of different degenerative processes, C. elegans continues to be an exciting venue for uncovering basic mechanisms that control cell viability normally and in pathological states. Several of the seemingly disparate cell death phenomena described in this review share common threads, either morphological (Fig. 1) or molecular. As our understanding of cell death processes expands, additional interconnections may emerge, providing insight into what key cellular aspects must be dismantled for cells to give up the ghost.

Highlights.

The core apoptotic pathway can be regulated at any step.

Death processes share morphological features and possibly downstream effectors.

Linker cell death is a novel death program possibly relevant to human biology.

References

- 1.Ameisen JC. On the origin, evolution, and nature of programmed cell death: a timeline of four billion years. Cell Death Diff. 2002;9:367–393. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Aster JC. Robbins & Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sulston JE, Schierenberg E, White JG, Thomson JN. The embryonic cell lineage of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1983;100:64–119. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974;77:71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kamath RS, Martinez-Campos M, Zipperlen P, Fraser AG, Ahringer J. Effectiveness of specific RNA-mediated interference through ingested double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genome Biol. 2001;2 doi: 10.1186/gb-2000-2-1-research0002. RESEARCH0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.C. elegans Sequencing Consortium. Genome sequence of the nematode C. elegans: a platform for investigating biology. Science. 1998;282:2012–2018. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellis HM, Horvitz HR. Genetic control of programmed cell death in the nematode C. elegans. Cell. 1986;44:817–829. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horvitz HR, Shaham S, Hengartner MO. The genetics of programmed cell death in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1994;59:377–385. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1994.059.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nehme R, Conradt B. egl-1: a key activator of apoptotic cell death in C. elegans. Oncogene. 2008;27(Suppl 1):S30–40. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conradt B, Horvitz HR. The C. elegans protein EGL-1 is required for programmed cell death and interacts with the Bcl-2-like protein CED-9. Cell. 1998;93:519–529. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81182-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang X, Chang HY, Baltimore D. Essential role of CED-4 oligomerization in CED-3 activation and apoptosis. Science. 1998;281:1355–1357. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan N, Chai J, Lee E-S, Gu L, Liu Q, He J, et al. Structure of the CED-4-CED-9 complex provides insights into programmed cell death in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2005;437:831–837. doi: 10.1038/nature04002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xue D, Shaham S, Horvitz HR. The Caenorhabditis elegans cell-death protein CED-3 is a cysteine protease with substrate specificities similar to those of the human CPP32 protease. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1073–1083. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.9.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Driscoll M, Chalfie M. The mec-4 gene is a member of a family of Caenorhabditis elegans genes that can mutate to induce neuronal degeneration. Nature. 1991;349:588–593. doi: 10.1038/349588a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chalfie M, Wolinsky E. The identification and suppression of inherited neurodegeneration in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1990;345:410–416. doi: 10.1038/345410a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shreffler W, Magardino T, Shekdar K, Wolinsky E. The unc-8 and sup-40 genes regulate ion channel function in Caenorhabditis elegans motorneurons. Genetics. 1995;139:1261–1272. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.3.1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hall DH, Gu G, García-Añoveros J, Gong L, Chalfie M, Driscoll M. Neuropathology of degenerative cell death in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci. 1997;17:1033–1045. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-03-01033.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hong K, Driscoll M. A transmembrane domain of the putative channel subunit MEC-4 influences mechanotransduction and neurodegeneration in C. elegans. Nature. 1994;367:470–473. doi: 10.1038/367470a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bianchi L, Gerstbrein B, Frøkjær-Jensen C, Royal DC, Mukherjee G, Royal MA, et al. The neurotoxic MEC-4(d) DEG/ENaC sodium channel conducts calcium: implications for necrosis initiation. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:1337–1344. doi: 10.1038/nn1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Y, Matthewman C, Han L, Miller T, Miller DM, Bianchi L. Neurotoxic unc-8 mutants encode constitutively active DEG/ENaC channels that are blocked by divalent cations. J Gen Physiol. 2013;142:157–169. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201310974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Treinin M, Chalfie M. A mutated acetylcholine receptor subunit causes neuronal degeneration in C. elegans. Neuron. 1995;14:871–877. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90231-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu K, Tavernarakis N, Driscoll M. Necrotic cell death in C. elegans requires the function of calreticulin and regulators of Ca(2+) release from the endoplasmic reticulum. Neuron. 2001;31:957–971. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00432-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kourtis N, Nikoletopoulou V, Tavernarakis N. Small heat-shock proteins protect from heat-stroke-associated neurodegeneration. Nature. 2012;490:213–218. doi: 10.1038/nature11417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Syntichaki P, Xu K, Driscoll M, Tavernarakis N. Specific aspartyl and calpain proteases are required for neurodegeneration in C. elegans. Nature. 2002;419:939–944. doi: 10.1038/nature01108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Syntichaki P, Samara C, Tavernarakis N. The vacuolar H+ -ATPase mediates intracellular acidification required for neurodegeneration in C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1249–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Artal-Sanz M, Samara C, Syntichaki P, Tavernarakis N. Lysosomal biogenesis and function is critical for necrotic cell death in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Cell Biol. 2006;173:231–239. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200511103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berger AJ, Hart AC, Kaplan JM. G alphas-induced neurodegeneration in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci. 1998;18:2871–2880. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-08-02871.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Korswagen HC, Park JH, Ohshima Y, Plasterk RH. An activating mutation in a Caenorhabditis elegans Gs protein induces neural degeneration. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1493–1503. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.12.1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mano I, Driscoll M. Caenorhabditis elegans glutamate transporter deletion induces AMPA-receptor/adenylyl cyclase 9-dependent excitotoxicity. J Neurochem. 2009;108:1373–1384. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xiong Z-G, Zhu X-M, Chu X-P, Minami M, Hey J, Wei W-L, et al. Neuroprotection in ischemia: blocking calcium-permeable acid-sensing ion channels. Cell. 2004;118:687–698. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou X, Ding Q, Chen Z, Yun H, Wang H. Involvement of the GluN2A and GluN2B subunits in synaptic and extrasynaptic N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor function and neuronal excitotoxicity. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:24151–24159. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.482000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang L, Hanna-Rose W. EGF signaling overcomes a uterine cell death associated with temporal mis-coordination of organogenesis within the C. elegans egg-laying apparatus. Dev Biol. 2006;300:599–611. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vrablik TL, Huang L, Lange SE, Hanna-Rose W. Nicotinamidase modulation of NAD+ biosynthesis and nicotinamide levels separately affect reproductive development and cell survival in C. elegans. Development. 2009;136:3637–3646. doi: 10.1242/dev.028431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chelur DS, Chalfie M. Targeted cell killing by reconstituted caspases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S a. 2007;104:2283–2288. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610877104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raymond CS, Murphy MW, O’Sullivan MG, Bardwell VJ, Zarkower D. Dmrt1, a gene related to worm and fly sexual regulators, is required for mammalian testis differentiation. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2587–2595. doi: 10.1101/gad.834100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hetz C. The unfolded protein response: controlling cell fate decisions under ER stress and beyond. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:89–102. doi: 10.1038/nrm3270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arrigo AP. In search of the molecular mechanism by which small stress proteins counteract apoptosis during cellular differentiation. J Cell Biochem. 2005;94:241–246. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Labouesse M, Sookhareea S, Horvitz HR. The Caenorhabditis elegans gene lin-26 is required to specify the fates of hypodermal cells and encodes a presumptive zinc-finger transcription factor. Development. 1994;120:2359–2368. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.9.2359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McGee MD, Rillo R, Anderson AS, Starr DA. UNC-83 IS a KASH protein required for nuclear migration and is recruited to the outer nuclear membrane by a physical interaction with the SUN protein UNC-84. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:1790–1801. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-09-0894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Malone CJ, Fixsen WD, Horvitz HR, Han M. UNC-84 localizes to the nuclear envelope and is required for nuclear migration and anchoring during C. elegans development. Development. 1999;126:3171–3181. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.14.3171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Starr DA, Hermann GJ, Malone CJ, Fixsen W, Priess JR, Horvitz HR, et al. unc-83 encodes a novel component of the nuclear envelope and is essential for proper nuclear migration. Development. 2001;128:5039–5050. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.24.5039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Böhmer RM. Interaction of serum and colony-stimulating factor for survival of a factor-dependent hemopoietic progenitor cell line. J Cell Physiol. 1989;139:531–537. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041390312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Howard MK, Burke LC, Mailhos C, Pizzey A, Gilbert CS, Lawson WD, et al. Cell cycle arrest of proliferating neuronal cells by serum deprivation can result in either apoptosis or differentiation. J Neurochem. 1993;60:1783–1791. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb13404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kulkarni GV, McCulloch CA. Serum deprivation induces apoptotic cell death in a subset of Balb/c 3T3 fibroblasts. J Cell Sci. 1994;107(Pt 5):1169–1179. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.5.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang X, Castilla LH, Xu X, Li C, Gotay J, Weinstein M, et al. Angiogenesis defects and mesenchymal apoptosis in mice lacking SMAD5. Development. 1999;126:1571–1580. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.8.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Derry WB, Putzke AP, Rothman JH. Caenorhabditis elegans p53: role in apoptosis, meiosis, and stress resistance. Science. 2001;294:591–595. doi: 10.1126/science.1065486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Galvin BD, Kim S, Horvitz HR. Caenorhabditis elegans genes required for the engulfment of apoptotic corpses function in the cytotoxic cell deaths induced by mutations in lin-24 and lin-33. Genetics. 2008;179:403–417. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.087221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reddien PW, Cameron S, Horvitz HR. Phagocytosis promotes programmed cell death in C. elegans. Nature. 2001;412:198–202. doi: 10.1038/35084096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Denning DP, Hatch V, Horvitz HR. Both the caspase CSP-1 and a caspase-independent pathway promote programmed cell death in parallel to the canonical pathway for apoptosis in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 9(2013):e1003341. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Anderluh G, Lakey JH. Disparate proteins use similar architectures to damage membranes. Trends Biochem Sci. 2008;33:482–490. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chávez-Galán L, Arenas-Del Angel MC, Zenteno E, Chávez R, Lascurain R. Cell death mechanisms induced by cytotoxic lymphocytes. Cell Mol Immunol. 2009;6:15–25. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2009.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Joshi P, Eisenmann DM. The Caenorhabditis elegans pvl-5 gene protects hypodermal cells from ced-3-dependent, ced-4-independentcell death. Genetics. 2004;167:673–685. doi: 10.1534/genetics.103.020503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sommer RJ, Sternberg PW. Apoptosis and change of competence limit the size of the vulva equivalence group in Pristionchus pacificus: a genetic analysis. Curr Biol. 1996;6:52–59. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sommer RJ, Eizinger A, Lee KZ, Jungblut B, Bubeck A, Schlak I. The Pristionchus HOX gene Ppa-lin-39 inhibits programmed cell death to specify the vulva equivalence group and is not required during vulval induction. Development. 1998;125:3865–3873. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.19.3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bloss TA, Witze ES, Rothman JH. Suppression of CED-3-independent apoptosis by mitochondrial betaNAC in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2003;424:1066–1071. doi: 10.1038/nature01920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Denning DP, Hatch V, Horvitz HR. Programmed elimination of cells by caspase-independent cell extrusion in C. elegans. Nature. 2012;488:226–230. doi: 10.1038/nature11240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chien S-C, Brinkmann E-M, Teuliere J, Garriga G. Caenorhabditis elegans PIG-1/MELK acts in a conserved PAR-4/LKB1 polarity pathway to promote asymmetric neuroblast divisions. Genetics. 2013;193:897–909. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.148106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Avery L, Horvitz HR. A cell that dies during wild-type C. elegans development can function as a neuron in a ced-3 mutant. Cell. 1987;51:1071–1078. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90593-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cordes S, Frank CA, Garriga G. The C. elegans MELK ortholog PIG-1 regulates cell size asymmetry and daughter cell fate in asymmetric neuroblast divisions. Development. 2006;133:2747–2756. doi: 10.1242/dev.02447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ou G, Stuurman N, D’Ambrosio M, Vale RD. Polarized myosin produces unequal-size daughters during asymmetric cell division. Science. 2010;330:677–680. doi: 10.1126/science.1196112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Morton DG, Hoose WA, Kemphues KJ. A genome-wide RNAi screen for enhancers of par mutants reveals new contributors to early embryonic polarity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2012;192:929–942. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.143727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hirose T, Horvitz HR. An Sp1 transcription factor coordinates caspase-dependent and -independent apoptotic pathways. Nature. 2013;500:354–358. doi: 10.1038/nature12329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gumienny TL, Lambie E, Hartwieg E, Horvitz HR, Hengartner MO. Genetic control of programmed cell death in the Caenorhabditis elegans hermaphrodite germline. Development. 1999;126:1011–1022. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.5.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li X, Johnson RW, Park D, Chin-Sang I, Chamberlin HM. Somatic gonad sheath cells and Eph receptor signaling promote germ-cell death in C. elegans. Cell Death Diff. 2012;19:1080–1089. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Church DL, Guan KL, Lambie EJ. Three genes of the MAP kinase cascade, mek-2, mpk-1/sur-1 and let-60 ras, are required for meiotic cell cycle progression in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development. 1995;121:2525–2535. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.8.2525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Park D, Jia H, Rajakumar V, Chamberlin HM. Pax2/5/8 proteins promote cell survival in C. elegans. Development. 2006;133:4193–4202. doi: 10.1242/dev.02614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ito S, Greiss S, Gartner A, Derry WB. Cell-nonautonomous regulation of C. elegans germ cell death by kri-1. Curr Biol. 2010;20:333–338. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Morthorst TH, Olsen A. Cell-nonautonomous inhibition of radiation-induced apoptosis by dynein light chain 1 in Caenorhabditis elegans. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e799. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Angelo G, Van Gilst MR. Starvation protects germline stem cells and extends reproductive longevity in C. elegans. Science. 2009;326:954–958. doi: 10.1126/science.1178343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Aballay A, Ausubel FM. Programmed cell death mediated by ced-3 and ced-4 protects Caenorhabditis elegans from Salmonella typhimurium-mediated killing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S a. 2001;98:2735–2739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041613098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Salinas LS, Maldonado E, Navarro RE. Stress-induced germ cell apoptosis by a p53 independent pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans. Cell Death Diff. 2006;13:2129–2139. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Andux S, Ellis RE. Apoptosismaintains oocyte quality in aging Caenorhabditis elegans females. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000295. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sendoel A, Kohler I, Fellmann C, Lowe SW, Hengartner MO. HIF-1 antagonizes p53-mediated apoptosis through a secreted neuronal tyrosinase. Nature. 2010;465:577–583. doi: 10.1038/nature09141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Silva N, Adamo A, Santonicola P, Martinez-Perez E, La Volpe A. Pro-crossover factors regulate damage-dependent apoptosis in the Caenorhabditis elegans germ line. Cell Death Diff. 2013;20:1209–1218. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Maurer CW, Chiorazzi M, Shaham S. Timing of the onset of a developmental cell death is controlled by transcriptional induction of the C. elegans ced-3 caspase-encoding gene. Development. 2007;134:1357–1368. doi: 10.1242/dev.02818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chiorazzi M, Rui L, Yang Y, Ceribelli M, Tishbi N, Maurer CW, et al. Related F-box proteins control cell death in Caenorhabditis elegans and human lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:3943–3948. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217271110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Barros R, Freund J-N, David L, Almeida R. Gastric intestinal metaplasia revisited: function and regulation of CDX2. Trends Mol Med. 2012;18:555–563. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2012.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.White JQ, Nicholas TJ, Gritton J, Truong L, Davidson ER, Jorgensen EM. The sensory circuitry for sexual attraction in C. elegans males. Curr Biol. 2007;17:1847–1857. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sulston JE, Horvitz HR. Post-embryonic cell lineages of the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1977;56:110–156. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(77)90158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Peden E, Kimberly E, Gengyo-Ando K, Mitani S, Xue D. Control of sex-specific apoptosis in C. elegans by the BarH homeodomain protein CEH-30 and the transcriptional repressor UNC-37/Groucho. Genes Dev. 2007;21:3195–3207. doi: 10.1101/gad.1607807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nehme R, Grote P, Tomasi T, Löser S, Holzkamp H, Schnabel R, et al. Transcriptional upregulation of both egl-1 BH3-only and ced-3 caspase is required for the death of the male-specific CEM neurons. Cell Death Diff. 2010;17:1266–1276. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Schwartz HT, Horvitz HR. The C. elegans protein CEH-30 protects male-specific neurons from apoptosis independently of the Bcl-2 homolog CED-9. Genes Dev. 2007;21:3181–3194. doi: 10.1101/gad.1607007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hodgkin J. A genetic analysis of the sex-determining gene, tra-1, in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes Dev. 1987;1:731–745. doi: 10.1101/gad.1.7.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zarkower D, Hodgkin J. Molecular analysis of the C. elegans sex-determining gene tra-1: agene encoding two zinc finger proteins. Cell. 1992;70:237–249. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90099-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shaham S, Reddien PW, Davies B, Horvitz HR. Mutational analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans cell-death gene ced-3. Genetics. 1999;153:1655–1671. doi: 10.1093/genetics/153.4.1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shaham S. Identification of multiple Caenorhabditis elegans caspases and their potential roles in proteolytic cascades. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:35109–35117. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.52.35109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Geng X, Zhou QH, Kage-Nakadai E, Shi Y, Yan N, Mitani S, et al. Caenorhabditis elegans caspase homolog CSP-2inhibits CED-3 autoactivation and apoptosis in germ cells. Cell Death Diff. 2009;16:1385–1394. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Geng X, Shi Y, Nakagawa A, Yoshina S, Mitani S, Shi Y, et al. Inhibition of CED-3 zymogen activation and apoptosis in Caenorhabditis elegans by caspase homolog CSP-3. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:1094–1101. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kimble J, Hirsh D. The postembryonic cell lineages of the hermaphrodite and male gonads in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1979;70:396–417. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(79)90035-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Abraham MC, Lu Y, Shaham S. A morphologically conserved nonapoptotic program promotes linker cell death in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Cell. 2007;12:73–86. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Blum ES, Abraham MC, Yoshimura S, Lu Y, Shaham S. Control of Nonapoptotic Developmental Cell Death in Caenorhabditis elegans by a Polyglutamine-Repeat Protein. Science. 2012;335:970–973. doi: 10.1126/science.1215156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Harris DT, Horvitz HR. MAB-10/NAB acts with LIN-29/EGR to regulate terminal differentiation and the transition from larva to adult in C. elegans. Development. 2011;138:4051–4062. doi: 10.1242/dev.065417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pilar G, Landmesser L. Ultrastructural differences during embryonic cell death in normal and peripherally deprived ciliary ganglia. J Cell Biol. 1976;68:339–356. doi: 10.1083/jcb.68.2.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Oppenheim RW, Flavell RA, Vinsant S, Prevette D, Kuan CY, Rakic P. Programmed cell death of developing mammalian neurons after genetic deletion of caspases. J Neurosci. 2001;21:4752–4760. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-13-04752.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Osterloh JM, Yang J, Rooney TM, Fox AN, Adalbert R, Powell EH, et al. dSarm/Sarm1 is required for activation of aninjury-induced axon death pathway. Science. 2012;337:481–484. doi: 10.1126/science.1223899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Massoll C, Mando W, Chintala SK. Excitotoxicity upregulates SARM1 protein expression and promotes Wallerian-like degeneration of retinal ganglion cells and their axons. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:2771–2780. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-10973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kato M, Sternberg PW. The C. elegans tailless/Tlx homolog nhr-67 regulates a stage-specific program of linker cell migration in male gonadogenesis. Development. 2009;136:3907–3915. doi: 10.1242/dev.035477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Martin DN, Baehrecke EH. Caspases function in autophagic programmed cell death in Drosophila. Development. 2004;131:275–284. doi: 10.1242/dev.00933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zhou Z, Hartwieg E, Horvitz HR. CED-1 is a transmembrane receptor that mediates cell corpse engulfment in C. elegans. Cell. 2001;104:43–56. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00190-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Nass R, Hall DH, Miller DM, Blakely RD. Neurotoxin-induced degeneration of dopamine neurons in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S a. 2002;99:3264–3269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042497999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Nass R, Blakely RD. The Caenorhabditis elegans dopaminergic system: opportunities for insights into dopamine transport and neurodegeneration. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2003;43:521–544. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.43.100901.135934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]