Abstract

AMPK (AMP-dependant protein kinase)-mTORC1 (mechanistic target of rapamycin in complex 1)-p70S6K1 (ribosomal protein S6 kinase 1 of 70 kDa) signaling plays a crucial role in muscle protein synthesis (MPS). Understanding this pathway has been advanced by the application of the Western blot (WB) technique. However, because many components of the mTORC1 pathway undergo numerous, multisite posttranslational modifications, solely studying the phosphorylation changes of mTORC1 and its substrates may not adequately represent the true metabolic signaling processes. The aim of this study was to develop and apply a quantitative in vitro [γ-32P] ATP kinase assay (KA) for p70S6K1 to assess kinase activity in human skeletal muscle to resistance exercise (RE) and protein feeding. In an initial series of experiments the assay was validated in tissue culture and in p70S6K1-knockout tissues. Following these experiments, the methodology was applied to assess p70S6K1 signaling responses to a physiologically relevant stimulus. Six men performed unilateral RE followed by the consumption of 20 g of protein. Muscle biopsies were obtained at pre-RE, and 1 and 3 h post-RE. In response to RE and protein consumption, p70S6K1 activity as assessed by the KA was significantly increased from pre-RE at 1 and 3 h post-RE. However, phosphorylated p70S6K1thr389 was not significantly elevated. AMPK activity was suppressed from pre-RE at 3 h post-RE, whereas phosphorylated ACCser79 was unchanged. Total protein kinase B activity also was unchanged after RE from pre-RE levels. Of the other markers we assessed by WB, 4EBP1thr37/46 phosphorylation was the only significant responder, being elevated at 3 h post-RE from pre-RE. These data highlight the utility of the KA to study skeletal muscle plasticity.

Keywords: mTORC1, p70S6K1, AMPK, resistance exercise

the ampk (amp-dependant protein kinase)-mTORC1 (mechanistic target of rapamycin in complex 1)-p70S6K1 (ribosomal protein S6 kinase 1 of 70 kDa) cascade is a key regulatory signaling axis controlling a plethora of human metabolic events such as skeletal muscle protein synthesis (MPS) (11), glucose disposal (18, 29), and fatty acid metabolism (26). Our understanding of how the AMPK-mTORC1-p70S6K1 pathway responds to physiological perturbation such as exercise (11) and nutrition (9) has been advanced by the application of the phosphorylation-specific Western blot (WB) technique. This technique assesses the phosphorylation of a kinase or a kinase target on serine, threonine, and tyrosine residues, and infers the activity of a kinase on the basis of the magnitude of phosphorylation as determined by densitometry. The WB technique is highly advantageous because it offers the capacity to measure phosphorylation changes in many targets in a cost-effective way. However, in some cases, the WB technique possesses a limited dynamic range that can lead to type II statistical errors (18). Furthermore, differences in methodological approaches to the WB are known to lead to different statistical outcomes for the same data sets (14). Another consideration is that p70S6K1 has a constitutively low baseline phosphorylation. As such, when changes in p70S6K1 phosphorylation to anabolic stimulation are represented as a fold or percentage change, this low baseline phosphorylation results in an inflated response that is not representative of a physiological change in activity (21, 27). Hence, our understanding of how various stimuli such as exercise and nutrition affect p70S6K1 signaling is in part confined to both the limitations and assumptions of the WB technique.

In a recent commentary, Murphy and Lamb (24) describe a fully quantitative approach to WB. These authors show that by using calibration curves for each gel, a quantitative assessment of changes in protein expression can be made. However, conducting calibration curves for the analysis of posttranslational modifications (PTM) such as phosphorylation would be contingent upon 100% of the recombinant protein modified specifically at the specific PTM residue. Furthermore, the use of such calibration curves on every gel would prove costly when analyzing numerous samples, thus undermining the financial viability of the WB technique. As such, the use of the WB to assess changes in the phosphorylation of a kinase as a proxy of kinase activity remains a challenge.

The in vitro [γ-32P] ATP kinase assay (KA) is the gold standard for assessing kinase activity (16). This methodology involves immunoprecipitating the kinase of interest from homogenized tissue. The activity of the kinase is then assessed in vitro against a kinase-specific or kinase family-specific substrate. Gamma (γ)-32P ATP is subsequently used to measure the incorporation of phosphate into the substrate via liquid scintillation counting, thus enabling a quantitative assessment of activity. The dual layer of specificity and quantitative nature of the KA may obviate some of the methodological shortcomings associated with using the WB (14) and its use to assess AMPK activity in response to exercise is now a feature in the human exercise sciences (10, 37, 40). A semiquantitative p70S6K1 KA does exist for use in rodent tissue (21), and a quantitative p70S6K1 KA has previously been used in cell culture studies (33). However, no study has described a fully quantitative KA methodology for the assessment of p70S6K1 activity in human skeletal muscle.

Therefore, the primary aim of this methodological study was to develop and validate a fully quantitative p70S6K1 KA methodology to assess p70S6K1 activity in human skeletal muscle in response to resistance exercise (RE) and protein feeding. Because muscle tissue availability is often a major limitation to routine analytical procedures, a secondary aim was to simultaneously assess AMPK activity and another regulator of mTOR (mechanistic target of rapamycin), protein kinase B (PKB), from the same muscle biopsy sample as p70S6K1. In this regard, we also aimed to validate a serial immunoprecipitation (IP) protocol to enable the dual assessment of p70S6K1 and PKB, from the same muscle homogenate. It is hoped that these methodological developments will enhance our capacity to accurately delineate the molecular mechanisms that regulate human skeletal muscle plasticity.

METHODS

Materials

Unless otherwise stated, all materials were from Fisher Scientific (Loughborough, UK). All antibodies, unless otherwise stated, were used at a concentration of 1:1,000, and were from New England Biolabs (Herts, UK). Selected primary antibodies were mTORser2448 (#2974), total mTOR (#2983), acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC)ser79 (#3661), total ACC (#3676), total glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (#2118), regulatory-associated protein of mTOR (Raptor)ser792 (#2083), total GRB10 (#3702), p70S6K1thr389 (#11759; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), total p70S6K1 (#2708), PKBthr308 (#2965), total PKB (#4691), proline-rich Akt/PKB substrate 40 kDa (PRAS40)thr246 (#2997) and total PRAS40 (#2691), 4EBP1thr37/46 (#2855), and total 4EBP1 (#9644). Secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody was purchased from ABCAM (#6721). Prepoured gels for WB were 4–20% Tris-Glyc Criterion gradient gels from BioRad (Herts, UK). AMPK α1- and α2-specific antibodies were produced by GL Biochem (Shanghai, China) against the following antigens: α1, CTSPPDSFLDDHHLTR; and α2, CMDDSAMHIPPGLKPH (38).

Tissue Culture Experiments

C2C12 myoblasts were grown to confluence on T75 plates in growth media [(GM) 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Dundee Cell Products, Dundee, UK), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) in high-glucose DMEM (Invitrogen)]. Confluent myoblasts were then transferred to differentiation media [(DM) 2% donor horse serum (Dundee Cell Products), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen) in high-glucose DMEM (Invitrogen)]. Prior to the addition of inhibitors cells were serum- and amino acid-starved in PBS with 5 mM glucose (Invitrogen) for 3 h. Starved cells were then pretreated with an inhibitor [100 nM rapamycin (Sigma Aldrich), 10 μM LY294002 (Cell Signaling) or vehicle control (0.1% DMSO)] for 1 h prior to serum and amino acid stimulation by the addition of GM supplemented with or without inhibitors. After 30 min of stimulation cells were lysed on ice in 1 ml of radio immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer [50 mmol/l Tris·HCl pH 7.5, 50 mmol/l NaF, 500 mmol/l NaCl, 1 mmol/l sodium vanadate, 1 mmol/l EDTA, 1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100, 5 mmol/l sodium pyrophosphate, 0.27 mmol/l sucrose, and 0.1% (vol/vol) 2-mercaptoethanol and Complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche)] and then stored at −80°C. HEK293 cell lysates overexpressing either the α1 or the α2 subunit of AMPK were a gift from Professor Grahame Hardie (Division of Cell Signaling and Immunology, University of Dundee).

p70S6K1−/− tissues.

All animal experiments on p70S6K1−/− and littermate controls (wild type; WT) were approved by and conducted in accordance with the Direction Départementale des Services Vétérinaires, Préfecture de Police, Paris, France (authorization 75–1313). Mice (p70S6K1−/−) were generated as previously described (26a). The mice were housed in plastic cages and maintained at 22°C with a 12-h dark/12-h light cycle and had free access to food. Starved mice were WT; p70S6K1−/− mice had food withdrawn overnight and were then refed standard chow for 4 h. Animals were killed by cervical dislocation, and tibialis anterior muscles were rapidly dissected, blotted dry, and snap-frozen in liquid N2.

Mouse ex vivo and in vivo insulin stimulations.

All animal experiments were approved by and conducted in accordance with the Animal Care Program at the University of California, San Diego, for the ex vivo insulin stimulations; and the Animal Care Program at the University of California, Davis, for the in vivo insulin stimulations. Ex vivo insulin stimulations were carried out as follows: 6 male C57/Bl6 mice were fasted for 4 h and anesthetized (150 mg/kg nembutal) via ip injection. Paired extensor digitorum longus muscles were excised and incubated at 35°C for 30 min in oxygenated (95% O2, 5% CO2) flasks of Krebs-Henseleit buffer (KHB) containing 0.1% BSA, 2 mM sodium pyruvate, and 6 mM mannitol. One muscle per pair was incubated in KHB without insulin, and the contralateral muscle was incubated in KHB with insulin [60 μU/ml (0.36 nM); Humulin R, Eli Lilly]. After 50 min, muscles were blotted on ice-cold filter paper, trimmed, freeze-clamped, and then stored at −80°C (n = 6). In vivo insulin stimulations were carried out as follows: 2 female C57/Bl6 mice were fasted for 4 h and anesthetized with 2% isoflourane vaporized in 100% O2. One mouse was ip injected with 100 mU/kg of insulin (Humulin R, Eli Lilly). After 30 min the muscles from the lower limb were dissected and snap-frozen in liquid N2. The control mouse went through the same procedure except that it was injected with 0.9% saline.

Human Experimental Study

Participants.

Six healthy, moderately trained men [mean ± SD: age, 23 ± 2 yr; body mass, 76 ± 5 kg; height, 179 ± 5 cm; unilateral 1 repetition maximum (1 RM) leg press, 128 ± 8 kg; 1 RM leg extension, 54 ± 3 kg] were recruited to participate in this study. All participants engaged in resistance training approximately two times per week and played team sports recreationally. Prior to the commencement of the experiment each participant provided written informed consent after all procedures and risks were fully explained in lay terms. Participants also were required to satisfy a routine physical activity readiness questionnaire. The study procedures were approved by the Research Institute for Sport and Exercise Sciences Ethics Committee, Liverpool John Moores University, and conformed to the standards as outlined in the most recent version of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study design.

Seven days after confirmation of unilateral 1 RM for leg press and leg extension, six healthy, moderately trained men reported to the laboratory at ∼7:00 a.m. in a 10-h postabsorptive state. Each participant's height and body mass were recorded, after which they rested (∼30 min) in a semisupine position on a bed, and a resting biopsy was obtained. Immediately after the biopsy participants were transported by wheelchair to the resistance-training laboratory where they performed a bout of unilateral RE. Immediately following the bout of unilateral RE, participants were required to consume 20 g of pure egg white powder in a 500-ml solution. Participants were then transported back to the resting laboratory and rested again in a semisupine position during which additional muscle biopsies were obtained at 1 and 3 h post-RE.

Resistance exercise protocol.

Testing (1 RM) was conducted as previously described (34). On the day of the experimental trial participants performed a bout of unilateral RE consisting of four sets of 10 repetitions at 70% 1 RM of leg press, followed by leg extension performed at the same intensity with their dominant limb. Recovery time between exercises and sets was 3 min and 2 min, respectively. Participants were provided with verbal cues to ensure correct exercise technique. Each repetition consisted of a 1-s concentric action, 0-s pause, then a 1-s eccentric action as previously reported (4).

Study controls.

Participants were required to record dietary intake for 3 days prior to the initial single 1 RM testing session, and to repeat this pattern of consumption for the 3 days preceding the day of the experimental trial. For 3 days prior to both 1 RM testing and the experimental trial, participants also were asked to refrain from any form of vigorous exercise. These controls were implemented in an attempt to prevent any nutritional or exercise-induced changes in protein activity that might adversely affect the results of the study.

Skeletal muscle biopsies.

Skeletal muscle biopsies were obtained on the exercising limb at pre-RE, 1 h post-RE, and 3 h post-RE using a Bard Monopty Disposable Core Biopsy Instrument (12 gauge × 10 cm length; Bard Biopsy Systems, Tempe, AZ). For each biopsy, the lateral portion of the vastus lateralis was cleaned before an incision into the skin and fascia was made under local anesthetic (MD92672; 0.5% marcaine without adrenaline). A sample of muscle (∼30 mg) was extracted, rinsed with ice-cold saline, blotted dry, and any visible fat or connective tissue was removed. Muscle samples were then snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for further analysis.

Muscle tissue processing.

Approximately 30 mg of human skeletal muscle tissue (∼5 mg of mouse skeletal muscle tissue) was homogenized by scissor mincing on ice in RIPA buffer [50 mmol/l Tris·HCl pH 7.5, 50 mmol/l NaF, 500 mmol/l NaCl, 1 mmol/l sodium vanadate, 1 mmol/l EDTA, 1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100, 5 mmol/l sodium pyrophosphate, 0.27 mmol/l sucrose, and 0.1% (vol/vol) 2-mercaptoethanol and Complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche)] followed by shaking at 1,000 rpm on a shaking platform for 60 min at 4°C. Debris was removed by centrifugation at 4°C for 15 min at 13,000 g. The supernatant was then removed, and protein concentration was determined using the bicinchoninic acid protein assay according to the manufacturer's instructions (Sigma Aldrich, UK).

Western blotting.

For WB, 300 μg of supernatant was made up in Lamelli sample buffer, and 5–15 μg of total protein was loaded per well with the same amount of protein loaded in all wells for each gel, and run at 150 V for 1 h 15 min. Proteins were then transferred onto Whatman Immunobilon Nitrocellulose membranes (Fisher Scientific, Loughborough, UK) at 30 V overnight on ice. Membranes were blocked in 3% BSA-Tris-buffered saline (containing vol/vol 0.1% Tween 20) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by incubation in primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. Membranes underwent three 5-min washes in TBST followed by incubation in the appropriate secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Membranes were again washed three times for 5 min followed by incubation in enhanced chemiluninescence reagent (BioRad, Herts, UK). A BioRad ChemiDoc (Herts, UK) was used to visualize and quantify protein expression. All phospho proteins were normalized to the corresponding total proteins after stripping the phospho antibody for 30 min at 50°C in stripping buffer (65 mM Tris·HCl, 2% SDS vol/vol, 0.8% mercaptoethanol vol/vol) and reprobing with the primary antibody for the corresponding total protein. All phospho proteins were normalized to the expression of the corresponding total with the exception of phosphorylated Raptorser792, which was normalized to the expression of GAPDH.

[γ-32P] ATP kinase assays.

All KA were carried out by IP either for 2 h at 4°C or overnight at 4°C in homogenization buffer {AMPK [50 mM Tris·HCl pH 7.25, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaF, 5 mM NaPPi, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1 mM benzamidine, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 5 μg/ml soybean trypsin inhibitor, 1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100] and p70S6K1/panPKB [50 mM Tris·HCl pH 7.5, 0.1 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, 1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100, 50 mM NaF, 5 mM NaPPi, 0.27 M sucrose, 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM Na3(OV)4, and 1 Complete (Roche) protease inhibitor tablet per 10 ml]}. Protein G sepharose (2.5 μl per IP) was used to precipitate the immune complexes. Immune complexes were washed twice in assay-specific high-salt washes (homogenization buffers as above with 0.5 M NaCl added) followed by one wash in assay-specific assay buffer (see below). Prior to carrying out the activity assay the immune-bead-complex was suspended in a total of 10 μl of assay buffer for p70S6K1 and panPKB assays, and 20 μl of assay buffer for AMPK assays. All assays were carried out in a 50-μl reaction. Assays were started every 20 s by the addition of a hot assay mix, which consisted of assay buffer [PKB/p70S6K1 (50 mM Tris·HCl pH 7.4, 0.03% Brij35, and 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol), AMPK (50 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 1 mM DTT, and 0.02% Brij35)], ATP-MgCl2 (100 μM ATP + 10 mM MgCl2 for p70S6K1/panPKB, and 200 μM ATP + 50 μM MgCl2 for AMPK), 32γ-ATP [specific activities as follows; panAMPK (0.25 × 106 cpm/nmol), panPKB (0.5 × 106 cpm/nmol), p70S6K1 (1 × 106 cpm/nmol)], and finally synthetic peptide substrates [Crosstide for panPKB (GRPRTSSFAEG at 30 μM), S6tide for p70S6K1 (KRRRLASLR at 30 μM), and AMARA for AMPK (AMARRAASAAALARRR at 200 μM)]. Assays were stopped at 20-s intervals by spotting onto squares of p81 chromatography paper (Whatman; GE Healthcare, UK) and immersing in 75 mM phosphoric acid. Papers (p81) were washed three times for 5 min in 75 mM phosphoric acid and once in acetone. They were then dried and immersed in Gold Star LT Quanta scintillation fluid (Meridian Biotechnologies, Chesterfield, UK) and counted in a Packard 2200CA TriCarb scintillation counter (United Technologies). Assay results were quantified in nmol·min−1·mg−1 (U/mg). Blanks for background subtractions were carried out with immunoprecipitated kinases with no peptide included in the assay reaction. For the AMPK antibody validation assays the AMPK α1 antibody (5 μg) was used to immunoprecipitate AMPK α1 complexes from 100 μg of lysate in duplicate, whereas AMPK α2 antibody (5 μg) was used to immunoprecipitate AMPK α2 complexes from 100 μg of lysate. These lysates were from HEK cells overexpressing either AMPK α1 or AMPK α2, and were a kind gift from Prof. Grahame Hardie (University of Dundee). Assays were carried out for 15 min. For p70S6K1 antibody validation, 2 μg of p70S6K1 antibody was used to immunoprecipitate p70S6K1 from 250 μg of muscle lysate from WT starved/refed and p70S6K1−/− refed mice. Activities assays for panPKB and p70S6K1 were carried out on cell lysates by IP from 200 μg of cell lysate. The IP step was performed with 2 μg each of PKBα/β/γ antibodies (DSTT, Dundee University) or 2 μg of p70S6K1 antibody (H-9; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Heidelberg, Germany), respectively. Antibodies were used with 2.5 μl of protein G sepharose per IP to immunoprecipitate for 2 h at 4°C. p70S6K1 and panPKB were assayed for 45 min and 20 min, respectively.

Time-dependent saturation assays.

Three human skeletal muscle biopsy samples were pooled and homogenized. Homogenate was aliquoted to 2.4 mg for panPKB assays, 6 mg for p70S6K1 assays, and 0.6 mg for AMPK assays. Antibodies of PKBα/β/γ (72 μg each) were used to immunoprecipitate panPKB, 48 μg of p70S6K1 antibody was used to immunoprecipitate p70S6K1, and 60 μg each of AMPK α1 and α2 were used to immunoprecipitate panAMPK. Following IP, each of these immune complexes were aliquoted into 12 aliquots for activity assays; 9 of the aliquots were used for activity assays for the time course of 7.5, 15, and 30 min for AMPK; 15, 30, and 60 min for panPKB and p70S6K1. The three remaining aliquots were used for no-peptide controls to generate assay-specific blanks. Each assay represented an IP from 50 μg of lysate for panAMPK, 200 μg of lysate for panPKB, and 500 μg of lysate for p70S6K1.

For the serial IP validation, lower limb muscles from a 4-h fasted (Con) and an insulin-stimulated mouse [Ins (4-hr fasted + 100 mU insulin/kg for 30 min)] were homogenized and aliquoted into 6 × 200-μg aliquots each. IPs were set up to immunoprecipitate panPKB (3.2 μg of each PKB antibody) from three Con and three Ins aliquots, whereas the other aliquots had p70S6K1 immunoprecipitated (4 μg of p70S6K1 antibody) prior to immunoprecipitating with panPKB as before. Activity assays for panPKB were carried out as before following IP.

For p70S6K1/panPKB KA in human tissue, 500 μg of lysate was aliquoted, and p70S6K1 was immunoprecipitated with 4 μg of p70S6K1 and 2.5 μl of protein G sepharose (GE Healthcare) for 2 h at 4°C. The p70S6K1 KA was carried out for 45 min. Two hundred micrograms of the post-IP supernatant was then used for PKB IP. Two micrograms each of PKBα/β/γ antibodies (DSTT, Dundee University) were used with 2.5 μl of protein G sepharose to immunoprecipitate PKB at 4°C for 2 h. KA for panPKB were carried out as previously described for a 30-min assay. Following homogenization, 50 μg of lysate was aliquoted for AMPK activity assays. AMPK activity assays were carried out by IP with complexes in AMPK IP buffer (homogenization buffer as above). Immunoprecipitates were then washed, and AMPK activity was determined against AMARA peptide as previously described in a 20-min assay.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism Software version 6.0 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). Differences in kinase signaling activity and phosphorylation (i.e., p70SK61thr389, PKBthr308, AMPK activity) were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA and, when appropriate, a Tukey's post hoc analysis. Post hoc sample size calculations were conducted using GPower 3.0.8 software on the basis of an estimated effect size of 0.53, a 1-β error probability of 0.8, and a significance level < 0.05. All data unless otherwise stated are presented as means ± SE, and P < 0.05 indicates statistical significance.

RESULTS

Antibody/Assay Validation

panAMPK.

Total (or pan) AMPK activity is measured by immunoprecipitating both catalytic subunits of AMPK (AMPK α1 and AMPK α2). We commissioned our own AMPK α1 and AMPK α2 antibodies (GL Biochem, China) against the following antigens: α1, CTSPPDSFLDDHHLTR; and α2, CMDDSAMHIPPGLKPH (38). To confirm that our AMPK antibodies were specific for AMPK α1 and AMPK α2 and therefore capable of immunoprecipitating total AMPK when the antibodies are combined, we carried out a validation experiment (Fig. 1A). Cell lysates overexpressing either AMPK α1 or AMPK α2 underwent an IP with either the AMPK α1 or AMPK α2 antibody. AMPK α1 immunoprecipitated substantial activity from the AMPK α1 overexpressing cell lysates—approximately 10-fold more activity than the AMPK α2 antibody immunoprecipitated. The reverse experiment demonstrated a similar result, in that AMPK α2 immunoprecipitated approximately 10-fold more activity from the AMPK α2 overexpressing cell lysates than did the AMPK α1 antibody. These data demonstrate the specificity of our AMPK α1 and α2 antibodies. To further prove that these antibodies are immunoprecipitating active endogenous AMPK complexes, we carried out a positive control experiment by treating C2C12 myotubes with 100 μM 2,4-dinitrophenol [a known AMPK activator (39)] for 30 min, and followed this with panAMPK activity assays. This treatment resulted in a an approximately fourfold increase in panAMPK activity (Fig. 1B), concurrent with a substantial increase in phosphorylation of AMPK at Thr172 (Fig. 1B, inset).

Fig. 1.

Antibody and assay validation. A: AMPK α1 and AMPK α2 activity assays derived from immune complexes from cells overexpressing either AMPK α1 or AMPK α2. B: panAMPK activation in response to energy stress in C2C12 myotubes. C2C12 myotubes were serum-starved for 2 h prior to stimulation with 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP) (100 μM) for 30 min (n = 2 in duplicate). C: panPKB activation by serum stimulation and inhibition by LY294002 (10 μM). C2C12 myotubes were serum-starved for 3 h and preincubated with either vehicle (no treatment control; NTC) or LY294002 [10 μM (stimulated + LY; S+LY)] for 1 h (n = 3 in duplicate), then they were stimulated for 30 min in 20% fetal bovine serume (FBS) (S, stimulated). *Significantly different from NTC and S+LY. D: p70S6K1 activation by serum + amino acid stimulation and inhibition by rapamycin (100 nM). C2C12 myotubes were serum and amino acid-starved for 3 h in PBS + 5 mM glucose and preincubated with either vehicle (NTC) or rapamycin [100 nM (stimulated + rapamycin; S+R) for 1 h (n = 2 in triplicate)], then they were stimulated for 30 min in 20% FBS + DMEM (stimulated; S). E: p70S6K1 activity in response to overnight starvation (WT-S) and 4 h of refeeding (WT-R), and 4 h of refeeding in p70S6K1−/− mice. F: antibody saturation curve for p70S6K1 antibody in 500 μg of pooled human lysate. Insets are representative Western blots. All data expressed as means ± SD. ND, nondetectable.

panPKB.

Total (or pan) PKB activity can be assessed by utilizing recombinant glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3) as a substrate and then running a standard WB with a phosphorylated GSK3 antibody to determine phosphate incorporation (3). However, this approach again relies upon densitometry analysis and makes comparisons across large sample sets difficult. Therefore, we utilized a filter binding assay that also allowed for quantitative scintillation counting. We used antibodies and a peptide substrate (6) that have been previously well characterized (6, 22). However, to confirm that we were detecting panPKB activity with the immune complex we carried out a positive control experiment (Fig. 1C). We serum-stimulated C2C12 myotubes that had been treated with or without the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (35). Serum stimulation led to an approximate fivefold increase in panPKB activity, whereas the inhibition of PI3K with LY294002 significantly inhibited panPKB activity. The changes in activity were reflected by changes in phosphorylation (Fig. 1C, inset).

p70S6K1.

Traditionally, p70S6K1 activity assays are carried out with recombinant S6 as a substrate (21) wherein the radioactively labeled substrate is run on a gel before being exposed to radiography film. This assay is more difficult to accurately quantitate with large sample numbers due to the necessity to expose all samples to SDS-PAGE. Furthermore, this method still requires the use of densitometry analysis that can be subjective, leading to variable outputs depending upon the method of quantification (14). However, several laboratories have utilized a scintillation assay to quantitatively assess p70S6K1 activity (7, 33). To utilize a quantitative p70S6K1 activity assay that can be applied more easily to large sample numbers we employed a similar assay protocol with a peptide substrate analog of S6 corresponding to amino acids 230–238 on human 40S ribosomal protein S6 (KRRRLASLR) (12). This approach allowed for the use of filter paper capture of the labeled peptide that can then be quantitatively analyzed via scintillation counting. To confirm that this method did not alter the output of the assay we carried out a validation experiment in C2C12 myoblasts (Fig. 1D). We used serum and amino acid stimulation as a positive control with rapamycin (specifically inhibits mTORC1 activity) as a control to confirm that serum and amino acid-induced activation of kinase activity was in fact p70S6K1-specific. We showed that serum and amino acid stimulation induces an approximately 10-fold increase in activity, whereas rapamycin completely blocks this activation (Fig. 1D) and the phosphorylation of p70S6K1thr389 (Fig. 1D, inset). These data demonstrate the mTORC1 dependence of the kinase activity we measured. To further validate that no other contaminating kinases could be contributing activity in our assay we also ran the assay from starved/refed WT mice and refed p70S6K1−/− mice. We found approximately 19-fold more activity in refed mouse muscle vs. starved mouse muscle, and we could not detect any activity in the p70S6K1−/− mice. These data highlight the specificity of our assay to p70S6K1. Prior to moving the assay into human tissue we first needed to define the amount of antibody required to saturate p70S6K1 in human skeletal muscle. This would ensure that all the p70S6K1 in the lysate was immunoprecipitated, thus improving consistency across sample sets. We used increasing amounts of antibody to immunoprecipitate p70S6K1 from 500 μg of protein lysate extracted from pooled human muscle biopsy material from at least three volunteers. We found that despite increasing amounts of IgG-heavy chain (from the p70S6K1 antibody), the amount of p70S6K1 that was immunoprecipitated from 500 μg of protein lysate was saturated by 2 μg of antibody. We therefore used 4 μg of p70S6K1 antibody for every 500 μg of protein lysate to ensure that our antibody was always in excess.

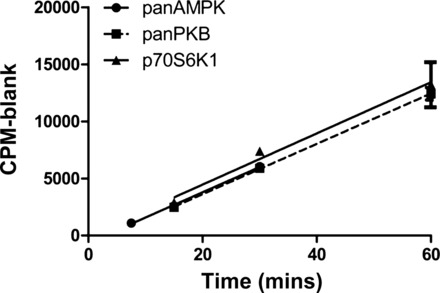

Time-Dependent Saturation Curves

To select the most appropriate duration for each assay in human biopsy samples we carried out a time-dependant saturation curve for each assay from a pool of human muscle biopsies (Fig. 2). We carried out the AMPK assays for 7.5, 15, and 30 min, whereas PKB and p70S6K1 assays were carried out for 15, 30, and 60 min. These assays revealed linearity across the time course for each assay, indicating that assays carried out for anywhere between 7.5 and 30 min for panAMPK, and 15–60 min for panPKB and p70S6K1, would be within the linear range for time.

Fig. 2.

Saturation time course of activity assays carried out from pooled human skeletal muscle protein lysate. R2 values are as follows: AMPK = 0.969; panPKB = 0.982; and p70S6K1 = 0.856. All data are expressed as means ± SD.

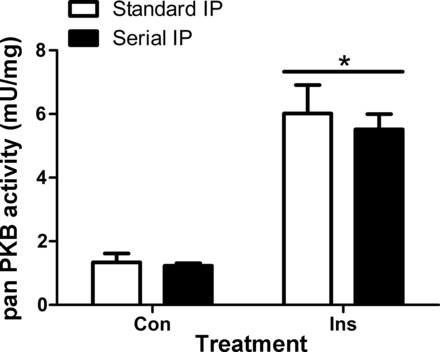

Validation of the Serial IP

To economize on tissue with human muscle samples, panPKB and p70S6K1 activity assays were carried out via serial IP with p70S6K1 immunoprecipitated first. To confirm that this serial IP process did not affect PKB activity we performed a validation of this procedure in response to maximal insulin stimulation (Fig. 3). Serially immunoprecipitating panPKB after p70S6K1 had no significant effect upon panPKB activity compared with a standard IP (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Serial immunoprecipitation (IP) validation. IPs were set up to immunoprecipitate panPKB alone or p70S6K1 immunoprecipitated prior to immunoprecipitating with panPKB. *Significantly different from both control (Con) conditions. All data are expressed as means ± SE.

Application of the [γ-32P] ATP KA in a Physiological Context in Human Skeletal Muscle

We next determined whether we could measure the activity of panAMPK, panPKB, and p70S6K1 from the same human skeletal muscle sample following a well-defined anabolic stimulus in humans (23). In our study we identified a significant increase in p70S6K1 activity from pre-RE at 1 and 3 h post-RE (P < 0.05; Fig. 4C). However, there was no significant change in panPKB activity at any time point (Fig. 4B). Finally, panAMPK activity was significantly repressed (P < 0.05; Fig. 4A) at 3 h post-RE compared with pre-RE. To confirm that we were able to detect physiologically relevant changes in panPKB activity, we assessed the activation of panPKB in response to a physiologically relevant (0.36 nM) insulin stimulus in ex vivo mouse skeletal muscle (Fig. 4B, inset). Indeed, we detected a significant increase in panPKB activity in response to 50 min of insulin stimulation, thus confirming that this assay is capable of detecting changes in panPKB activity in a physiological context.

Fig. 4.

Application of three kinase assays in human skeletal muscle in response to a physiological anabolic stimulus of resistance exercise combined with feeding 20 g of protein (n = 6). A: panAMPK activity was determined from 50 μg of lysate in a 20-min reaction against the synthetic substrate AMARA. B: panPKB activity serially immunoprecipitated after p70S6K1 IP. Inset: panPKB activity response to a physiological insulin stimulation of 0.36 nM for 50 min in ex vivo mouse skeletal muscle (n = 6). panPKB activity was determined from 200 μg of lysate in a 30-min reaction against the synthetic peptide substrate Crosstide. C: p70S6K1 activity was determined from 500 μg of lysate in a 45-min reaction against the synthetic peptide substrate S6K1tide. Pre-RE indicates biopsy taken prior to resistance exercise and feeding, 1 h post-RE indicates the biopsy taken 1 h following combined resistance exercise and feeding, 3 h post-RE indicates biopsy taken 3 h following combined resistance exercise and feeding. *Significantly different from Con or Pre-RE (P < 0.05). All data are expressed as means ± SE.

Western Blotting

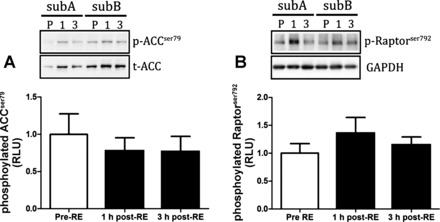

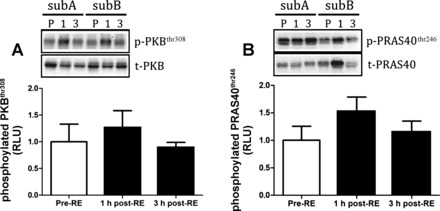

Following the assessment of kinase activity as markers of anabolic responses in humans we next measured the phosphorylation of proteins that are typically used as surrogate readouts of anabolic signaling activity. The responses of kinases as determined by WB are shown in Fig. 5 (AMPK readouts), Fig. 6 (PKB readouts), and Fig. 7 (mTORC1 readouts). In response to RE and nutrition, there were no significant changes in phosphorylated mTORser2448 (Fig. 7A), ACCser79 (Fig. 5A), Raptorser792 (Fig. 5B), p70S6K1thr389 (Fig. 7B), PKBthr308 (Fig. 6A), and PRAS40thr246 (Fig. 6B). However, phosphorylated 4EBP1thr37/46 was significantly elevated at 3 h post-RE compared with pre-RE (P < 0.05; Fig. 7C). Representative WB images appear as insets above each graph.

Fig. 5.

Markers of AMPK activity in response to a physiological anabolic stimulus of resistance exercise combined with feeding 20 g of protein. Protein phosphorylation of ACCser79 (A) and Raptorser792 (B) obtained at pre-RE, and 1 and 3 h post-RE. All data are expressed as means ± SE.

Fig. 6.

Markers of panPKB activity in response to a physiological anabolic stimulus of resistance exercise combined with feeding 20 g of protein. Protein phosphorylation of PKBthr308 (A) and PRAS40thr246 (B). All data are expressed as means ± SE.

Fig. 7.

Markers of mTORC1 activation in response to a physiological anabolic stimulus of resistance exercise combined with feeding 20 g of protein. mTORser2448 (A), p70S6K1thr389 (B), and 4EBP1thr37/46 (C). *Significantly different from pre-RE (P < 0.05). All data are expressed as means ± SE.

DISCUSSION

The main aim of the present methodological study was to develop and validate a quantitative p70S6K1 KA for use in human skeletal muscle biopsy samples. Second, we aimed to examine the physiological context of alterations in p70S6K1 activity by examining parallel alterations in PKB and AMPK activity in response to acute RE and protein feeding (23). For the first time we demonstrated that combined RE and protein feeding significantly increases p70S6K1 activity by approximately twofold, as determined by the KA with a similar, approximate twofold but nonsignificant change in p70S6K1thr389 phosphorylation. In addition, we observed a suppression of AMPK activity that was not apparent when assessing ACCser79 phosphorylation, a known readout of AMPK activity (36). Furthermore, we demonstrate the capacity to achieve a dual measure of panPKB and p70S6K1 activity from the same sample via a serial IP protocol. This study therefore highlights the potential application of the KA described in this investigation to study the molecular signaling responses of skeletal muscle to RE and nutrition.

Although we observed a significant increase in p70S6K1 activity to RE and protein feeding, we detected no significant changes in the phosphorylation of p70S6K1thr389. This finding is unexpected, given previous reports of significant, approximate twofold (5) and 12-fold (2) increases in phosphorylated p706K61thr389 to an acute bout of RE and protein feeding. Although the lack of detectable change in phosphorylated p70S6K1thr389 in our investigation appears to be related to low statistical power. Indeed, a post hoc sample size calculation from the present study determined that a participant sample of 12 would have been necessary to detect a statistically significant difference in phosphorylated p70S6K1thr389 between pre-RE and 1 h post-RE and protein ingestion. However, by utilizing the KA, we were able to detect a modest increase in p70S6K1 activity from pre-RE at 1 and 3 h post-RE and feeding. Thus these data highlight not only the precision but also the utility of this p70S6K1 KA to assess p70S6K1 activity to anabolic stimulation.

Due to issues associated with ethical practice and participant compliance in human research, muscle tissue availability is often a limiting factor. In this investigation we provided a validated, serial IP protocol for the dual assessment of p70S6K1 and panPKB activity from a single muscle homogenate. We showed that this serial IP protocol has no effect on panPKB activity, hence economizing on muscle tissue requirements. When applying this protocol to study panPKB responses of human skeletal muscle to RE and feeding, we showed no change in panPKB activity at any time point, a finding that corroborates previous reports (25, 28, 32). However, it is important to note that the panPKB KA described in this methodological investigation failed to provide information regarding PKB isoform-specific effects that could be useful in understanding cell growth and metabolism (30). The development of such a methodology is therefore a topic for future work.

The increase in p70S6K1 activity in our investigation was associated with a decrease in AMPK activity. These data are similar to findings showing that RE (1) or feeding (13) also repress AMPKthr172 phosphorylation, but these findings are incongruent with previous work that demonstrated RE increases AMPK α2 activity 1 h post-RE (10). However, in that study, RE was not followed by feeding, and one possibility is that the protein feeding in our study may have overridden RE-induced increases in AMPK activity, perhaps via restoration of the AMP:ATP ratio (15). Alternatively, it is known that p70S6K1 can inhibit AMPK via phosphorylation at Ser491 in mouse hypothalamic cells (8), although this latter hypothesis has yet to be observed in human skeletal muscle. A reduction in AMPK activity also is known to relieve inhibition on mTOR-p70S6K1 signaling (17), which could partially explain the sustained increase in p70S6K1 activation at 3 h post-RE and feeding in our investigation. Interestingly, the significant reduction in AMPK activity in our study was not mirrored by a reduction in ACCser79 phosphorylation (P = 0.70). We chose to assess the phosphorylation of ACCser79 as a readout of AMPK activity because phosphorylated AMPKthr172 possesses a low dynamic range that renders phosphorylated AMPKthr172 on this residue a poor surrogate of true AMPK activity (18). Therefore, the decrease in AMPK activity paralleled with a nonsignificant change in ACCser79 phosphorylation further emphasizes the potential application of the KA to assess RE and nutrition-induced changes in signaling.

Both RE and protein ingestion are known to increase MPS via mTOR-p70S6K1 signaling (9, 11, 20). However, in response to RE and protein ingestion, we detected no significant change in the phosphorylation status of Raptorser792, PRAS40thr246, or mTORser2448. This finding was surprising because there was a significant increase in the phosphorylation of the mTOR substrate 4EBP1thr37/46 at 3 h post-RE and protein feeding. Others have also shown no change in mTORser2448 phosphorylation to a 48-g whey bolus at both 1 and 3 h postfeeding despite increases in phosphorylated p70S6K1thr389 and 4EBP1thr37/46 (3). Furthermore, it is also known that mutation of the ser2448 residue on mTOR fails to significantly affect p70S6K1 activity in cell-based systems (31). It therefore appears that mTORser2448 phosphorylation does not offer the most accurate readout of mTORC1 activity. Hence, studies that aim to infer changes in mTORC1 activity to anabolic stimulation using the WB technique may be better served by assessing changes in the phosphorylation of the mTOR substrates 4EBP1 and p70S6K1 rather than mTORser2448 phosphorylation itself.

In summary, this study provides a novel, fully quantitative methodology to assess p70S6K1-specific activity in human skeletal muscle. In addition, we provide a validated serial IP protocol that enables the dual assessment of PKB and p70S6K1 activity from a single skeletal muscle biopsy sample. Given that the number and yield of human muscle biopsies present major limitations to routine analytical procedures, being able to assess the activity of three key kinases from the same muscle sample represents an attractive measurement strategy. However, it is important to acknowledge that this KA provides no information pertaining to the posttranslational modification of a protein such as phosphorylation. Indeed, it is important to recognize that phosphorylation is a critical regulatory step in protein function (19). Finally, it is important to acknowledge that the suitability of the KA is to provide a quantitative measurement of endogenous kinase activity, which would complement WB approaches to study protein PTM. In this manner, the KA would then allow a researcher to assess the physiological relevance of multisite PTM. Given the critical role of protein kinases in the regulation of MPS, the next logical step is therefore to combine the KA, WB, and direct measures of MPS to provide a more in-depth insight into changes in skeletal muscle signaling in response to perturbations such as age, exercise, and disease.

GRANTS

This work was partially funded by a Capital Investment Award (University of Stirling) to D.L.H., a Society for Endocrinology Young Investigator Award to D.L.H., and an American College of Sports Medicine Research Endowment to D.L.H.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: C.M., B.D., G.L.C., D.P.M.M., I.T.C., A.P., J.P.M., and D.L.H. conception and design of research; C.M., A.T.W., C.T., I.T.C., S.S., J.P.M., and D.L.H. performed experiments; C.M., A.T.W., B.D., G.L.C., D.P.M.M., A.P., S.S., J.P.M., and D.L.H. analyzed data; C.M., A.T.W., A.P., J.P.M., and D.L.H. interpreted results of experiments; C.M. and D.L.H. prepared figures; C.M. and D.L.H. drafted manuscript; C.M., A.T.W., C.T., B.D., G.L.C., D.P.M.M., A.P., S.S., J.P.M., and D.L.H. edited and revised manuscript; C.M., A.T.W., C.T., B.D., G.L.C., D.P.M.M., I.T.C., A.P., S.S., J.P.M., and D.L.H. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank G. Dreczkowski, L. Macnaughton, S. Jeromeson, and F. Scott for their technical assistance, and Dr. K. Baar for sending us the in vivo insulin-stimulated mouse tissue. We also extend our appreciation to members of the Health and Exercise Sciences Research Group, University of Stirling, for their comments during preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Apró W, Wang L, Pontén M, Blomstrand E, Sahlin K. Resistance exercise induced mTORC1 signaling is not impaired by subsequent endurance exercise in human skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 305: E22–E32, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Areta JL, Burke LM, Ross ML, Camera DM, West DW, Broad EM, Jeacocke NA, Moore DR, Stellingwerff T, Phillips SM, Hawley JA, Coffey VG. Timing and distribution of protein ingestion during prolonged recovery from resistance exercise alters myofibrillar protein synthesis. J Physiol 591: 2319–2331, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atherton PJ, Etheridge T, Watt PW, Wilkinson D, Selby A, Rankin D, Smith K, Rennie MJ. Muscle full effect after oral protein: time-dependent concordance and discordance between human muscle protein synthesis and mTORC1 signaling. Am J Clin Nutr 92: 1080–1088, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burd NA, West DW, Staples AW, Atherton PJ, Baker JM, Moore DR, Holwerda AM, Parise G, Rennie MJ, Baker SK, Phillips SM. Low-load high volume resistance exercise stimulates muscle protein synthesis more than high-load low volume resistance exercise in young men. PLoS One 5: e12033, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Churchward-Venne TA, Burd NA, Mitchell CJ, West DW, Philp A, Marcotte GR, Baker SK, Baar K, Phillips SM. Supplementation of a suboptimal protein dose with leucine or essential amino acids: effects on myofibrillar protein synthesis at rest and following resistance exercise in men. J Physiol 590: 2751–2765, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cross DA, Alessi DR, Cohen P, Andjelkovich M, Hemmings BA. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 by insulin mediated by protein kinase B. Nature 378: 785–789, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cuenda A, Cohen P. Stress-activated protein kinase-2/p38 and a rapamycin-sensitive pathway are required for C2C12 myogenesis. J Biol Chem 274: 4341–4346, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dagon Y, Hur E, Zheng B, Wellenstein K, Cantley LC, Kahn BB. p70S6 kinase phosphorylates AMPK on serine 491 to mediate leptin's effect on food intake. Cell Metab 16: 104–112, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dickinson JM, Fry CS, Drummond MJ, Gundermann DM, Walker DK, Glynn EL, Timmerman KL, Dhanani S, Volpi E, Rasmussen BB. Mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 activation is required for the stimulation of human skeletal muscle protein synthesis by essential amino acids. J Nutr 141: 856–862, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dreyer HC, Fujita S, Cadenas JG, Chinkes DL, Volpi E, Rasmussen BB. Resistance exercise increases AMPK activity and reduces 4E-BP1 phosphorylation and protein synthesis in human skeletal muscle. J Physiol 576: 613–624, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drummond MJ, Fry CS, Glynn EL, Dreyer HC, Dhanani S, Timmerman KL, Volpi E, Rasmussen BB. Rapamycin administration in humans blocks the contraction-induced increase in skeletal muscle protein synthesis. J Physiol 587: 1535–1546, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flotow H, Thomas G. Substrate recognition determinants of the mitogen-activated 70K S6 kinase from rat liver. J Biol Chem 267: 3074–3078, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujita S, Dreyer HC, Drummond MJ, Glynn EL, Cadenas JG, Yoshizawa F, Volpi E, Rasmussen BB. Nutrient signalling in the regulation of human muscle protein synthesis. J Physiol 582: 813–823, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gassmann M, Grenacher B, Rohde B, Vogel J. Quantifying Western blots: pitfalls of densitometry. Electrophoresis 30: 1845–1855, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hardie DG, Ross FA, Hawley SA. AMPK: a nutrient and energy sensor that maintains energy homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 13: 251–262, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hastie CJ, McLauchlan HJ, Cohen P. Assay of protein kinases using radiolabeled ATP: a protocol. Nat Protoc 1: 968–971, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inoki K, Zhu T, Guan KL. TSC2 mediates cellular energy response to control cell growth and survival. Cell 115: 577–590, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jensen TE, Rose AJ, Hellsten Y, Wojtaszewski JF, Richter EA. Caffeine-induced Ca2+ release increases AMPK-dependent glucose uptake in rodent soleus muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 293: E286–E292, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kang SA, Pacold ME, Cervantes CL, Lim D, Lou HJ, Ottina K, Gray NS, Turk BE, Yaffe MB, Sabatini DM. mTORC1 phosphorylation sites encode their sensitivity to starvation and rapamycin. Science 341: 1236566, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kubica N, Bolster DR, Farrell PA, Kimball SR, Jefferson LS. Resistance exercise increases muscle protein synthesis and translation of eukaryotic initiation factor 2Bepsilon mRNA in a mammalian target of rapamycin-dependent manner. J Biol Chem 280: 7570–7580, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacKenzie MG, Hamilton DL, Murray JT, Taylor PM, Baar K. mVps34 is activated following high-resistance contractions. J Physiol 587: 253–260, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McNeilly AD, Williamson R, Balfour DJ, Stewart CA, Sutherland C. A high-fat-diet-induced cognitive deficit in rats that is not prevented by improving insulin sensitivity with metformin. Diabetologia 55: 3061–3070, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moore DR, Robinson MJ, Fry JL, Tang JE, Glover EI, Wilkinson SB, Prior T, Tarnopolsky MA, Phillips SM. Ingested protein dose response of muscle and albumin protein synthesis after resistance exercise in young men. Am J Clin Nutr 89: 161–168, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murphy RM, Lamb GD. Important considerations for protein analyses using antibody based techniques: down-sizing western blotting up-sizes outcomes. J Physiol 591: 5823–5831, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Neil TK, Duffy LR, Frey JW, Hornberger TA. The role of phosphoinositide 3-kinase and phosphatidic acid in the regulation of mammalian target of rapamycin following eccentric contractions. J Physiol 587: 3691–3701, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Neill HM, Holloway GP, Steinberg GR. AMPK regulation of fatty acid metabolism and mitochondrial biogenesis: implications for obesity. Mol Cell Endocrinol 366: 135–151, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26a.Pende M, Um SH, Mieulet V, Sticker M, Goss VL, Mestan J, Mueller M, Fumagalli S, Kozma SC, Thomas G. S6K1(−/−)/S6K2(−/−) mice exhibit perinatal lethality and rapamycin-sensitive 5′-terminal oligopyrimidine mRNA translation and reveal a mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent S6 kinase pathway. Mol Cell Biol 24: 3112–3124, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Philp A, Hamilton DL, Baar K. Signals mediating skeletal muscle remodeling by resistance exercise: PI3-kinase independent activation of mTORC1. J Appl Physiol 110: 561–568, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rasmussen BB. The missing Akt in the mechanical regulation of skeletal muscle mTORC1 signalling and growth. J Physiol 589: 1507, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richter EA, Hargreaves M. Exercise, GLUT4, and skeletal muscle glucose uptake. Physiol Rev 93: 993–1017, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schultze SM, Jensen J, Hemmings BA, Tschopp O, Niessen M. Promiscuous affairs of PKB/AKT isoforms in metabolism. Arch Physiol Biochem 117: 70–77, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sekulic A, Hudson CC, Homme JL, Yin P, Otterness DM, Karnitz LM, Abraham RT. A direct linkage between the phosphoinositide 3-kinase-AKT signaling pathway and the mammalian target of rapamycin in mitogen-stimulated and transformed cells. Cancer Res 60: 3504–3513, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spangenburg EE, Le Roith D, Ward CW, Bodine SC. A functional insulin-like growth factor receptor is not necessary for load-induced skeletal muscle hypertrophy. J Physiol 586: 283–291, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tang X, Wang L, Proud CG, Downes CP. Muscarinic receptor-mediated activation of p70 S6 kinase 1 (S6K1) in 1321N1 astrocytoma cells: permissive role of phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Biochem J 374: 137–143, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Verdijk LB, van Loon L, Meijer K, Savelberg HH. One-repetition maximum strength test represents a valid means to assess leg strength in vivo in humans. J Sports Sci 27: 59–68, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vlahos CJ, Matter WF, Hui KY, Brown RF. A specific inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, 2-(4-morpholinyl)-8-phenyl-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one (LY294002). J Biol Chem 269: 5241–5248, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Winder WW, Wilson HA, Hardie DG, Rasmussen BB, Hutber CA, Call GB, Clayton RD, Conley LM, Yoon S, Zhou B. Phosphorylation of rat muscle acetyl-CoA carboxylase by AMP-activated protein kinase and protein kinase A. J Appl Physiol 82: 219–225, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wojtaszewski JF, Mourtzakis M, Hillig T, Saltin B, Pilegaard H. Dissociation of AMPK activity and ACCbeta phosphorylation in human muscle during prolonged exercise. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 298: 309–316, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woods A, Salt I, Scott J, Hardie DG, Carling D. The alpha1 and alpha2 isoforms of the AMP-activated protein kinase have similar activities in rat liver but exhibit differences in substrate specificity in vitro. FEBS Lett 397: 347–351, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamaguchi S, Katahira H, Ozawa S, Nakamichi Y, Tanaka T, Shimoyama T, Takahashi K, Yoshimoto K, Imaizumi MO, Nagamatsu S, Ishida H. Activators of AMP-activated protein kinase enhance GLUT4 translocation and its glucose transport activity in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 289: E643–E649, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu M, Stepto NK, Chibalin AV, Fryer LG, Carling D, Krook A, Hawley JA, Zierath JR. Metabolic and mitogenic signal transduction in human skeletal muscle after intense cycling exercise. J Physiol 546: 327–335, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]