The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) was enacted on March 23, 2010 and has important implications for stroke care. The ACA is a comprehensive reform, though the signature component is the expansion of health insurance primarily by expanding Medicaid eligibility and by providing subsidies for consumers to purchase private insurance in online marketplaces called exchanges. While many ACA provisions went into effect with its passage or have been phased in over the last several years, the Medicaid expansion and insurance exchanges went into effect more recently in January 2014. In this paper, we begin by describing the working age stroke population. We then discuss the health insurance provisions of the ACA, which largely target the working age stroke population, and implications for racial/ethnic and geographic disparities. We then focus on how the ACA may impact stroke prevention, treatment and post-acute care. We conclude by discussing how health system reform under the ACA could affect stroke patients.

Stroke among Working Age Americans

Working age Americans, those 19-64 years, are experiencing stable or increasing stroke incidence even as overall stroke incidence is decreasing over time.1, 2 While racial and ethnic stroke disparities are present overall, the largest disparities are found among working age Americans.1, 2 To provide national estimates of stroke hospitalizations and insurance status among the working age population we used data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), a nationally representative sample of hospitalizations (see supplemental materials for methods details).

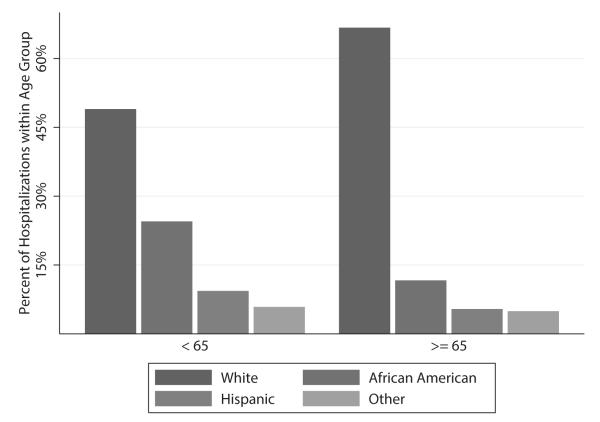

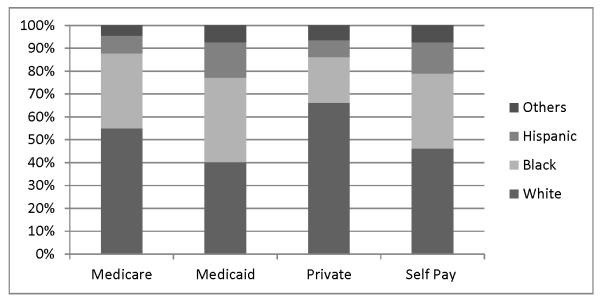

In 2010, about 230,000 or 37% of all stroke hospitalizations were among patients less than 65 years of age. Of the working age stroke hospitalizations, 20% were among patients who had Medicaid and 14% were among uninsured. Disparities in stroke hospitalizations and insurance status, particularly among African Americans, are striking. First, hospitalizations among the working age are more frequent in African Americans (26.5%) than would be expected on the basis of their population representation in the under 65 population (12.5%) (Figure1).3 Stroke hospitalizations in working age African Americans (10.1% of all stroke hospitalizations) comprise a greater proportion of all stroke hospitalizations than those over the age of 65 (8.3% of all stroke hospitalizations); a striking finding given the increase in stroke risk with advancing age. In addition, racial and ethnic minorities comprise 60% of Medicaid hospitalizations and 54% of the uninsured hospitalizations among the working age population (Figure 2). Among working age African Americans, 17% of stroke hospitalizations are among uninsured individuals and 27% are among Medicaid recipients. These proportions are similar in Hispanics where 18% of stroke hospitalizations are among the uninsured and 30% are among Medicaid recipients. Limitations to the race/ethnic comparisons should be noted given that 4 states or 11% of the hospitalizations do not provide race/ethnic data in the 2010 NIS and thus were excluded from the race/ethnic analyses.

Figure 1.

The percent of stroke admissions by race and ethnicity among working age stroke patients and those 65 years or older.

Figure 2.

Insurance status among working age stroke survivors

Using data from the 2012 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), similar patterns are seen among community-dwelling stroke survivors in the US, (see supplemental materials for methods details). Of the 3.17 million community-dwelling adult stroke survivors represented in NHIS, 1.29 million (41%) are under the age of 65. Sixty six percent of working age stroke survivors are non-Hispanic white, 24% are African American and 10% are Hispanic, while 16% are uninsured and 26% are Medicaid recipients. Disability is common among working age stroke survivors. Fifteen percent of working age stroke survivors need help with activities of daily living (bathing, dressing, eating, getting around inside their home) and 25% need help with instrumental activities of daily living (everyday household chores, doing necessary business, shopping, or getting around for other purposes). The ACA has important implications for all phases of stroke care given that a significant proportion of working age stroke patients are uninsured at the time of their stroke and a significant proportion of stroke survivors remain uninsured.

Health Insurance Expansion

Lack of insurance is associated with decreased access to primary care physicians4 and among stroke survivors with decreased access to specialists, medications and rehabilitation compared to those with private insurance.5, 6 Presumably, in part due to lack of access to medical care, stroke incidence is higher, treatment is suboptimal and mortality is increased in the uninsured compared with the insured.6-8 The ACA, by expanding Medicaid and mandating insurance coverage through health care exchanges, is reducing the number of uninsured Americans. Medicaid is likely to play an increasingly large role in stroke care. Medicaid is jointly financed by state and federal governments and has historically provided insurance coverage for children and low income families, pregnant women and the disabled. A major change implemented under the ACA is that nonelderly Americans without children will now be Medicaid eligible whereas prior to the ACA they would not have been in the majority of states.

Under the ACA, working age adults with incomes less than 138% of the federal poverty level (currently $16,105 for an individual and $32,913 for a family of four) will be eligible for Medicaid.9 The magnitude of the Medicaid expansion will vary by state as the Supreme Court ruling in 2012 gave states the opportunity to decline to participate. As of early 2014, 27 states, including Washington DC, have opted to expand Medicaid and 24 states (including large states such as Texas and Florida) have chosen not to expand Medicaid. The Medicaid expansion is projected to reach 10.3 million Americans in participating states, and this number is projected to extend to 14 million if all states participate.10 Furthermore given the publicity of the ACA, improved Medicaid enrollment strategies and the individual mandate, it is anticipated that as many as 9 million Americans who were previously eligible for Medicaid but unenrolled will now sign up.11

The health insurance exchange provides another pathway to gain insurance coverage. It is estimated that 16 million uninsured Americans will purchase insurance through the health insurance exchange by 2019 and that over 80% will receive tax incentives for doing so.12 In fact, over 8 million Americans have already purchased insurance through the exchange.13 Unlike Medicaid expansion which is optional to the states, every state will have a health insurance exchange for the individual and small group markets. States have the option of running their exchange or ceding control to the federal government. Uninsured Americans who have earnings above 100% of the federal poverty level but below 400% of the federal poverty level ($46,680 for an individual and $95,400 for a family of four) will qualify for tax credits to purchase health insurance on the exchange.9 When the Supreme Court struck down mandatory Medicaid expansion, an unintended coverage gap was created in states that are not expanding Medicaid. In those states, uninsured Americans with incomes below 100% of the federal poverty level will not receive Medicaid and are not eligible for tax credits to purchase insurance on the exchange.

The ACA also addresses insurance coverage of plans offered on the health insurance exchange and to new Medicaid enrollees. The ACA mandates that these insurance plans meet a standard of comprehensive benefits and services defined across the Institute of Medicine’s 10 categories of benefits, termed essential health benefit package.14 Each state has determined which essential health services within these 10 benefit categories will be obligatory for their state. The 10 essential health benefits categories will also extend to those newly enrolled in Medicaid under the ACA but not those who are eligible for Medicaid under the traditional Medicaid eligibility criteria.

These major expansions of eligibility and coverage of services have the potential to increase the number of people with access to stroke care. However, differences in how these reforms are implemented in each state may exacerbate existing race/ethnic and geographic stroke disparities.

Medicaid Expansion and Racial/Ethnic and Geographic Disparities

About one third of Medicaid eligible, uninsured adults live in states that will not expand Medicaid, many of whom will fall into the Medicaid coverage gap described above.15 Decisions to forego Medicaid expansion will likely have an impact on stroke survivors as uninsured working age stroke survivors are more likely to reside in a non Medicaid expanding state than an expanding state.16 Racial and ethnic minorities are also disproportionally impacted by state decisions on Medicaid expansion. For example, 40% of Medicaid eligible uninsured adult African Americans live in states that are not expanding Medicaid (primarily concentrated in Florida, Texas and Georgia).15 Given that the most pronounced racial/ethnic disparities in stroke incidence are among those under the age of 65,1, 2 the lack of access to insurance under the ACA in this population raises the possibility of exacerbating pre-existing stroke disparities.

These effects are likely to be particularly pronounced in the stroke belt. The eight states in the stroke belt (AL, AR, GA, LA, MS, NC, SC, TN) have higher stroke mortality and a trend toward greater stroke incidence than the remainder of the US.17 This region of the country also has high rates of poverty, obesity and decreased life expectancy compared to other regions of the country.18 With the exception of Arkansas, the stroke belt states are not expanding their Medicaid programs. Furthermore the stroke belt states are among the states with the highest demand for neurologists.19 Thus, to the extent that current geographic stroke disparities are due to limited access to medical care, these disparities may be exacerbated rather an ameliorated by variable Medicaid expansion.

Insurance and Stroke Prevention

The early results of the Oregon Health Study provide evidence on the effects of expanding access to insurance. In 2008, Oregon conducted a lottery to expand their Medicaid to a small proportion of uninsured, non-disabled adults similar to the population set to receive Medicaid under the ACA. If selected by the lottery, the person and their family had the opportunity to enroll in Oregon Medicaid.20 Results from the first two years show that obtaining Medicaid coverage increased access to and utilization of medical care, as well as decreased depressive symptoms.4 However, there were no differences in prevalence, diagnosis, or treatment of stroke risk factors including, blood pressure and cholesterol and no change in the Framingham risk score among those who did and did not receive Medicaid coverage.4 The significance of these findings has been hotly debated with detractors of this study contending that the experiment was under-powered to find clinically meaningful effects and that it was unrealistic to identify effects in this relatively healthy population on such a short time scale. Alternatively, it may be that improving access and increasing utilization of medical care in newly eligible Medicaid populations does not lead to improved cardiovascular risk factor detection and treatment. Prior macro-level data from state policy comparisons of Medicaid expansion has suggested that over longer timescales Medicaid coverage is associated with reduced mortality.21 So, while Medicaid expansion will almost certainly increase access to and utilization of medical care, its effects on outcomes such as stroke prevention is less certain and merit close attention.

Disproportionate Share Hospitals and Stroke Treatment

Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) payments are a subsidy from the federal government to hospitals to offset uncompensated care. DSH payments are intended for safety net hospitals, defined as hospitals that care for a disproportionately large number of uninsured and Medicaid beneficiaries.22 Two-thirds of safety net hospitals are in the south suggesting they may have an important role in caring for stroke patients given geographic disparities in stroke.23

The coverage expansion provisions of the ACA will decrease the number of uninsured Americans, resulting in hospitals providing less uncompensated care, and thus less need for DSH payments.24 DSH payment reductions were scheduled to start in October, 2013, both in states that are and are not expanding their Medicaid populations but payments have been extended to October, 2015.25 Careful attention to DSH payment cuts and their allocations is needed to ensure that access to and quality of stroke care does not decrease due to closure of or lack of resources at safety net hospitals, particularly in states not expanding Medicaid. DSH payment cuts may also increase racial/ethnic and geographic disparities given the states that are not expanding Medicaid.

Stroke Survivors: Medicaid, Essential Health Benefits and Post-acute Care

Post-stroke rehabilitation/post-acute care (PAC) is associated with improved functional outcomes among stroke survivors.26 Insurance status plays a large role in utilization of PAC. Uninsured stroke survivors are less likely to utilize institutional PAC (subacute nursing facility or inpatient rehabilitation facility) than stroke survivors with private insurance.5 Whereas stroke survivors with Medicaid are more likely to utilize institutional PAC, they disproportionally utilize the less intense PAC setting, subacute nursing facilities, than those with private insurance.5 Both Medicaid policy and essential health benefit coverage have the potential to shift this insurance based discrepancy in utilization of PAC.

Developing disability, defined as the inability to participate in substantial gainful activities for 12 months,27 increases access to health insurance for many Americans. Disabled stroke survivors can become eligible for insurance as a consequence of their stroke in one of two ways. First, disabled stroke survivors with low income and assets less than $2000 are eligible for supplemental security income (SSI), which is a fixed monthly amount. In most states, receipt of SSI automatically qualifies disabled stroke survivors for Medicaid after a disability assessment which occurs within 90 days of the application. Disabled stroke survivors who do not meet these financial criteria are eligible for social security disability insurance (SSDI). SSDI provides partial replacement income based on previous income for working age disabled Americans to receive a monthly payment. If approved, stroke survivors receive their first SSDI benefit 5 months after their disability was determined to begin and 2 years from the start of their SSDI they gain Medicare coverage. Some working age stroke survivors will be eligible for both Medicaid and Medicare due to their disability and low income/assets. However, a portion of stroke survivors with SSDI will remain uninsured during the over 2 years until their Medicare benefits are activated.28

The ACA does not change the definition of disability, SSI or SSDI. However, in states that expand Medicaid, more stroke survivors will be eligible for Medicaid based on income alone and thereby avoid the delay required for disability assessment.29 The ACA also gives states the discretion to broaden the use of presumptive eligibility to include all qualifying adults, as well as to allow hospitals to determine Medicaid eligibility based not only on income but also disability during hospital stay.30 This has the potential to increase the enrollment of eligible stroke survivors into Medicaid based on both income and disability, decrease time to obtain insurance and subsequently may allow for more options in PAC.

Insurance coverage of PAC is variable. Currently, state Medicaid policies have varied coverage of inpatient rehabilitation facilities ranging from full coverage, to need for pre-approval to no coverage. Rehabilitative and habilitative services and devices is one of the 10 essential health benefits. Given that states can define the specifics of their essential health benefits plan, it is likely that this varied coverage of inpatient rehabilitation facilities will continue in the essential health benefit packages under the ACA. Enrolling stroke survivors into Medicaid, particularly those who are uninsured at the time of their stroke, or into health care exchange policies that cover post-stroke rehabilitation may result in increased access to PAC and ultimately to reduced post-stroke disability. This is particularly promising for racial/ethnic minorities as disproportionate access to PAC may be contributing to their increased post-stroke disability compared to non-Hispanic Whites.31-33

Beyond Insurance Expansion. Implications for Medicare enrollees: Bundled Care

In addition to expanding the number of people with health insurance, the ACA seeks to improve healthcare quality and curb costs through health system reform. One possible way to achieve this goal is by supporting the creation of Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) and/or episode-based bundled payments which may represent standalone programs or may be incorporated into the traditional fee-for-service Medicare.34 ACOs are voluntary partnerships between hospitals and physician groups who work together to manage the care of patients across settings. ACOs are reimbursed per person for a set time period of medical care. In 2011, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation established the Pioneer ACOs while the ACA established the Medicare Shared Savings Program and the Advanced Payment Program. All programs care for traditional fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries in ACOs and then after achieving quality standards share in the cost savings.35 In the first year, all 32 Pioneer ACOs met quality measures including improved blood pressure control and 40% had cost savings.36 Results are not available for the shared savings program or the advanced payment program.

A complimentary approach to incentivizing high quality, less fragmented care may be payment by episodes of care where each hospital stay is its own payment bundle.37 Ultimately, it is likely that a single Medicare payment will cover not just a stroke hospitalization, but also PAC and short-term clinical follow-up. Currently, the ACA authorized Bundled Payments for Care Improvement initiative is underway to explore key components of the episode, including the inclusion of post-acute care and episode timeframes.38 Results will be forthcoming.

Both ACOs and episode based bundled payments have important implications for stroke given that stroke is one of Medicare’s top 5 most expensive admissions in part due to the high utilization of PAC among stroke survivors.37 PAC is of particular interest to Medicare given that it spent $62.1 billion or 11% of the total program on PAC in 2012 and it is the largest driver of geographic variation in Medicare spending.39,40 Thus, determining the specifics of ACOs and episode-based bundled payments will be important for stroke survivors. For example, determining whether subacute nursing facilities are part of the stroke survivors ACO or an alternate ACO affects whether the stroke survivors ACO has a vested financial interest in care coordination.41 In episode-based bundled payment, determining whether to include PAC and the duration of the episode have important consequences. If PAC is not included in the bundled payment episode, it may lead to stroke patient care being shifted from the hospital setting to the PAC setting similar to that seen when Medicare changed to a prospective payer system in the 1980’s.34 Alternatively, if the benefits of inpatient rehabilitation facilities on functional outcomes and long-term costs are not fully realized by the ACO, stroke patients may be shifted from costly inpatient rehabilitation facilities to less intense and less costly subacute rehabilitation facilities. Conversely, if PAC is objectively accounted for than this may align the incentives to optimize transitions of care and post-stroke recovery. Research is urgently needed to determine the content and duration of episodic payment bundles for stroke survivors.

Determining how best to incorporate neurologist and vascular neurologist care into these new health system models presents another challenge. There is currently a projected shortage in the neurology workforce due in combination to the aging US population and the projected increased healthcare utilization as a result of the ACA.19 The shortage of neurologists extends to vascular neurologists with shortages particularly notable in rural areas and underserved urban communities.42 Expansion of telemedicine for acute stroke patients may partially address the shortage of vascular neurologists; however telemedicine has not been commonly applied to other hospital and outpatient stroke care. Possible approaches to improving vascular neurology access include televisits, group medical visits or expanding the vascular neurology workforce.42, 43

Health Reform: The opportunity

The decline in stroke incidence and stroke mortality over the last decade represents an enormous step forward, but these gains have not fully extended to people of working age or to racial/ethnic minorities.1, 2, 44 To the extent that lack of insurance and access to medical care contribute to this disparity, the ACA may attenuate these differences particularly in states where Medicaid coverage is fully expanded. By recognizing the opportunities that the ACA holds, the stroke community is in a position to truly reduce stroke incidence and improve stroke care and PAC utilization. To do so, careful attention to the effects of the shifting policy landscape and the specific needs of Americans at risk for stroke and stroke survivors must be considered and brought to the attention of policy-makers at the state and federal levels to optimize care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: NIH/NINDS K23 NS073685 (Skolarus), NIH/NINDS K08NS082597 (Burke)

Footnotes

Disclosures: none

References

- 1.Kissela BM, Khoury JC, Alwell K, Moomaw CJ, Woo D, Adeoye O, et al. Age at stroke: Temporal trends in stroke incidence in a large, biracial population. Neurology. 2012;79:1781–1787. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318270401d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morgenstern LB, Smith MA, Sánchez BN, Brown DL, Zahuranec DB, Garcia N, et al. Persistent ischemic stroke disparities despite declining incidence in mexican americans. Annals of neurology. 2013;74:778–785. doi: 10.1002/ana.23972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bureau USC [Accessed April 24, 2014];Population: Estimates and projections by age, sex, race/ethnicity. https://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/cats/population/estimates_and_projections_by_age_sex_raceethnicity.html.

- 4.Baicker K, Taubman SL, Allen HL, Bernstein M, Gruber JH, Newhouse JP, et al. The oregon experiment — effects of medicaid on clinical outcomes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;368:1713–1722. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1212321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skolarus L, Meurer W, Burke J, Bettger JP, Lisabeth L. Effect of insurance status on postacute care among working age stroke survivors. Neurology. 2012;78:1590–1595. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182563bf5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levine DA, Neidecker M, Kiefe CI, Karve S, Williams L, Allison JJ. Racial/ethnic disparities in access to physician care and medications among us stroke survivors. Neurology. 2011;76:53–61. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318203e952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fowler-Brown A, Corbie-Smith G, Garrett J, Lurie N. Risk of cardiovascular events and death--does insurance matter? J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:502–507. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0127-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shen JJ, Washington EL. Disparities in outcomes among patients with stroke associated with insurance status. Stroke. 2007;38:1010–1016. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000257312.12989.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. [Accessed February 10, 2014];Hhs releases poverty guidelines for 2014. http://capsules.kaiserhealthnews.org/index.php/2014/01/hhs-releases-poverty-guidelines-for-2014.

- 10. [Accessed February 6, 2014];Number of uninsured eligible for medicaid under the aca. http://kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/number-of-uninsured-eligible-for-medicaid-under-the-aca/

- 11.Sommers BD, Epstein AM. Why states are so miffed about medicaid — economics, politics, and the “woodwork effect”. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365:100–102. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1104948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. [Accessed August 19, 2013];A profile of health insurance exchange enrollees. http://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/8147.pdf.

- 13. [Accessed April 24, 2014];The white house blog. http://www.whitehouse.gov/blog/2014/04/17/president-obama-8-million-people-have-signed-private-health-coverage.

- 14. [Accessed August 1, 2013];Comparing medicaid and exchanges: Benefits and costs for individuals and families. Congressional research service. http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R42978.pdf.

- 15. [Accessed January 15, 2014];The impact of the coverage gap in states not expanding medicaid by race and ethnicity. http://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/8527-the-impact-of-the-coverage-gap-in-states-not-expanding-medicaid.pdf.

- 16.Decker SL, Kenney GM, Long SK. Characteristics of uninsured low-income adults in states expanding vs not expanding medicaid. [published online ahead of print date] JAMA Internal Medicine. 2014 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howard VJ, Kleindorfer DO, Judd SE, McClure LA, Safford MM, Rhodes JD, et al. Disparities in stroke incidence contributing to disparities in stroke mortality. Annals of Neurology. 2011;69:619–627. doi: 10.1002/ana.22385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moses H, Matheson DH, Dorsey ER, George BP, Sadoff D, Yoshimura S. The anatomy of health care in the united states. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2013;310:1947–1963. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dall TM, Storm MV, Chakrabarti R, Drogan O, Keran CM, Donofrio PD, et al. Supply and demand analysis of the current and future us neurology workforce. Neurology. 2013;81:470–478. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318294b1cf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finkelstein A, Taubman S, Wright B, Bernstein M, Gruber J, Newhouse JP, et al. The oregon health insurance experiment: Evidence from the first year*. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2012;127:1057–1106. doi: 10.1093/qje/qjs020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sommers BD, Baicker K, Epstein AM. Mortality and access to care among adults after state medicaid expansions. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367:1025–1034. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1202099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spivey M, Kellermann AL. Rescuing the safety net. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;360:2598–2601. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0900728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andrews RMSD, Fraser I, Friedman B, Houchens RL. Serving the uninsured: Safety-net hospitals, 2003. Agency for healthcare research and quality; rockville, md: Jan, 2007. Hcup fact book. No. 8. (publication no. 07-0006.) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neuhausen K, Spivey M, Kellermann AL. State politics and the fate of the safety net. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;369:1675–1677. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1310572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. [Accessed February 20, 2014];Cmcs informational bulletin. Medicaid provisions in recently passed federal budget legislation. http://www.voryshcadvisors.com/files/2013/12/CIB-12-27-13.pdf.

- 26.Kramer AM, Steiner JF, Schlenker RE, Eilertsen TB, Hrincevich CA, Tropea DA, et al. Outcomes and costs after hip fracture and stroke. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;277:396–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Social security administration [Accessed April 25, 2014]; http://www.ssa.gov/redbook/eng/definedisability.htm#a0=0.

- 28.Dale SB, Verdier JM, Fund C. Elimination of medicare’s waiting period for seriously disabled adults: Impact on coverage and costs. Commonwealth Fund, Task Force on the Future of Health Insurance; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Musumeci M. [Accessed April 22, 2014];The affordable care act’s impact on medicaid eligibility, enrollment, and benefits for people with disabilities. http://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/8390-02-the-affordable-care-acts-impact-on-medicaid-eligibility.pdf.

- 30. [Accessed January 29, 2014];Health affairs policy brief: Hospital presumptive eligibility. http://www.healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief.php?brief_id=106.

- 31.Differences in disability among black and white stroke survivors--united states, 2000-2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54:3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Freburger JK, Holmes GM, Ku L-JE, Cutchin MP, Heatwole-Shank K, Edwards LJ. Disparities in postacute rehabilitation care for stroke: An analysis of the state inpatient databases. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2011;92:1220–1229. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lisabeth LD, Sánchez BN, Baek J, Skolarus LE, Smith MA, Garcia N, et al. Neurological, functional, and cognitive stroke outcomes in mexican americans. Stroke. 2014;45:1096–1101. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.003912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen C, Ackerly D. Beyond acos and bundled payments: Medicare’s shift toward accountability in fee-for-service. JAMA. 2014;311:673–674. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. [Accessed January 29, 2014];Summary of final rule provisions for accountable care organizations under the medicare shared savings program. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/sharedsavingsprogram/Downloads/ACO_Summary_Factsheet_ICN907404.pdf.

- 36. [Accessed January 29, 2014];Pioneer accountable care organizations succeed in improving care, lowering costs. http://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Press-Releases/2013-Press-Releases-Items/2013-07-16.html.

- 37.Cutler DM, Ghosh K. The potential for cost savings through bundled episode payments. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;366:1075–1077. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1113361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. [Accessed January 29, 2014];Bundled payments for care improvement (bpci) initiative: General information. http://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/Bundled-Payments/index.html.

- 39.(MedPAC) MPAC [Accessed January 29, 2014];Heatlh care spending and the medicare program. http://www.medpac.gov/documents/Jun13DataBookEntireReport.pdf.

- 40.Newhouse JP, Garber A, Graham RP. Interim report of the committee on geographic variation in health care spending and promotion of high-value health care: Preliminary committee observations. National Academies Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McWilliams JM, Chernew ME, Zaslavsky AM, Landon BE. Post-acute care and acos — who will be accountable? Health Services Research. 2013;48:1526–1538. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leira EC, Kaskie B, Froehler MT, Adams HP. The growing shortage of vascular neurologists in the era of health reform: Planning is brain. Stroke. 2013;44:822–827. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.000466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miller D, Zantop V, Hammer H, Faust S, Grumbach K. Group medical visits for low-income women with chronic disease: A feasibility study. Journal of Women’s Health. 2004;13:217–225. doi: 10.1089/154099904322966209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Towfighi A, Ovbiagele B, Saver JL. Therapeutic milestone: Stroke declines from the second to the third leading organ- and disease-specific cause of death in the united states. Stroke. 2010;41:499–503. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.571828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.