Summary

Iron (Fe) and copper (Cu) homeostasis are tightly linked across biology. In previous work, Fe deficiency interacted with Cu regulated genes and stimulated Cu accumulation.

The C940-fe (fefe) Fe uptake mutant of melon (Cucumis melo) was characterized, and the fefe mutant was used to test whether Cu deficiency could stimulate Fe uptake. Wild type and fefe mutant transcriptomes were determined by RNA-seq under Fe and Cu deficiency.

FeFe regulated genes included core Fe uptake, metal homeostasis, and transcription factor genes. Numerous genes were regulated by both Fe and Cu. The fefe mutant was rescued by high Fe or by Cu deficiency, which stimulated ferric-chelate reductase activity, FRO2 expression, and Fe accumulation. Accumulation of Fe in Cu deficient plants was independent of the normal Fe uptake system. One of the four FRO genes in the melon and cucumber (Cucumis sativus) genomes was Fe regulated, and one was Cu regulated. Simultaneous Fe and Cu deficiency synergistically upregulated Fe uptake gene expression.

Overlap in Fe and Cu deficiency transcriptomes highlights the importance of Fe– Cu crosstalk in metal homeostasis. The fefe gene is not orthologous to FIT, thus identification of this gene will provide clues to help understand regulation of Fe uptake in plants.

Keywords: copper (Cu), ferric-chelate reductase, fefe mutant, iron (Fe), iron–copper crosstalk, melon (Cucumis melo), metal homeostasis

Introduction

Iron (Fe) and copper (Cu) are trace metals that are required by plants for their roles in redox metabolism, such as mitochondrial respiration, photosynthesis, and nitrogen fixation (Puig et al., 2007; Burkhead et al., 2009; Hansch & Mendel, 2009; Pilon et al., 2011). Excess Fe or Cu leads to oxidative stress and damage from reactive oxygen species (Halliwell & Gutteridge, 1992). However, Fe and Cu are both involved in protection from reactive oxygen species (Hansch & Mendel, 2009) as components of peroxidases, catalase, and superoxide dismutases (SODs). Iron-containing SODs (FeSODs) and Cu-containing SODs (CuSODs) are functionally interchangeable, but are products of different genes (Kliebenstein et al., 1998; Alscher et al., 2002; Myouga et al., 2008; Pilon et al., 2011).

Iron deficiency responses include increased expression of certain genes to increase Fe uptake and to make cellular adjustments to maintain homeostasis. The bHLH transcription factor FIT is required for normal regulation of Fe uptake genes in Arabidopsis (Colangelo & Guerinot, 2004; Jakoby et al., 2004), including the ferricchelate reductase FRO2, the primary Fe transporter IRT1, and another Fe transporter, NRAMP1. The FIT protein interacts with other Fe regulated bHLH proteins, such as bHLH100, bHLH101, bHLH038, and bHLH039 (Yuan et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2013), and these proteins also have regulatory roles independent of FIT (Sivitz et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2013). Several metal homeostasis genes respond to both Fe and Cu, such as the metal transporters COPT2 and ZIP2, and the ferric-chelate reductase FRO3 (Sancenon et al., 2003; Wintz et al., 2003; Colangelo & Guerinot, 2004; Mukherjee et al., 2006; Buckhout et al., 2009; del Pozo et al., 2010; Garcia et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2010; Stein & Waters, 2012; Waters et al., 2012). Similarly, Cu deficiency results in upregulated ferric-chelate reductase activity in roots (Norvell et al., 1993; Welch et al., 1993; Cohen et al., 1997; Romera et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2004). Arabidopsis FRO4 and FRO5 are upregulated by Cu deficiency but not by Fe deficiency (Bernal et al., 2012), and provide low-level but significant ferric-chelate reductase activity.

Changes in availability of one mineral nutrient often results in changes in homeostasis of other minerals. For example, Fe deficiency caused changes in expression of genes related to potassium and phosphate (Wang et al., 2002) and sulfate (Paolacci et al., 2013) homeostasis. Fe homeostasis interacts with Zn tolerance (Pineau et al., 2012), and Cu deficiency interacts with phosphate signaling (Perea-García et al., 2013) and cadmium tolerance (Gayomba et al., 2013). Copper concentration was higher in Fe deficient leaves (Welch et al., 1993; Chaignon et al., 2002; Waters et al., 2012; Waters & Troupe, 2012). Several Cu responsive genes and microRNAs had altered abundance under Fe deficiency in Arabidopsis thaliana (Stein & Waters, 2012; Waters et al., 2012). This suggested that a specific role for accumulation of Cu under Fe deficiency is the replacement of FeSOD, which decreases under Fe deficiency (Kurepa et al., 1997; Waters et al., 2012), with CuSOD, whose transcripts increase in Fe deficient leaves (Waters et al., 2012). Supporting this hypothesis, counteraction of oxidative stress was impaired when formation of functional CuSOD protein was blocked under Fe deficiency (Waters et al., 2012). Increasing evidence points to the importance of Fe–Cu crosstalk in metal homeostasis (Bernal et al., 2012; Waters et al., 2012; Perea-García et al., 2013).

Mutant lines with altered metal homeostasis are valuable tools to study molecular and physiological responses to metal stress. The fefe mutation originated spontaneously in the melon (Cucumis melo) variety Edisto, and was crossed into the variety Mainstream to generate the C940-fe germplasm (Nugent & Bhella, 1988; Nugent, 1994). The fefe mutant lacks ferric-chelate reductase activity and rhizosphere acidification (Jolley et al., 1991), two of the important mechanisms of the reductive strategy of Fe uptake in dicots and non-grass monocots. The fefe mutant has chlorotic leaves typical of Fe deficiency, which can be corrected by application of external Fe. These signs point to fefe as a regulator of Fe uptake, but the mutant was not fully physiologically characterized to determine if the mutation is specific to root function. Additionally, gene expression levels in fefe had not been characterized.

Our overall objective in this study was to use the fefe mutant to increase understanding of Fe uptake regulation and to explore Fe–Cu crosstalk through characterization of transcriptomes of Fe and Cu deficient plants. Our specific goals were to: physiologically characterize the fefe mutant; use the fefe mutant to test whether Cu deficiency can interact with the Fe regulatory pathway to stimulate Fe accumulation; and determine transcriptomes in wild type (WT) and fefe plants in control and Fe or Cu deficient conditions to identify genes that are regulated by one or both metals. Here, we show that the fefe defect caused loss of normal regulation of Fe accumulation, was specific to roots, and could be rescued by Cu deficiency, which stimulated Fe uptake. Furthermore, we uncovered new synergistic interactions between Fe and Cu deficiencies on Fe uptake processes.

Materials and Methods

Plant growth and materials

Seeds were purchased for cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) cv Ashley (Jung Seed Co., Randolph, WI, USA) and melon (Cucumis melo L.) cv Edisto (Victory Seed Company, Molalla, OR, USA). Seeds of ‘snake melon’ (PI 435288) were obtained from the USDA National Plant Germplasm System. Seeds of C940-fe (fefe) melon (Nugent, 1994) were a generous gift from Michael A. Grusak, USDA-ARS Children’s Nutrition Research Center, Houston, TX, USA.

Plants were grown in a continuously aerated nutrient solution with the following composition: 0.8 mM KNO3, 0.4 mM Ca(NO3)2, 0.3 mM NH4H2PO4, 0.2 mM MgSO4, 20 μM Fe(III)-EDDHA (Sprint 138, Becker-Underwood, Ames, IA, USA), 25 μM CaCl2, 25 μM H3BO3, 2 μM MnCl2, 2 μM ZnSO4, 0.5 μM CuSO4, 0.5 μM Na2MoO4 and 1 mM MES buffer (pH 5.5) or, if indicated, HEPES buffer (pH 7.1). Fe was omitted or supplied as indicated for Fe supply treatments, and Cu was omitted or supplied as indicated for Cu supply treatments. For N source experiments, the same micronutrients described above were used, with a macronutrient solution of: 0.7 mM K2SO4, 0.1 mM KH2PO4, 0.1 mM KCl, 0.5 mM MgSO4, and 1 mM CaCl2. Nitrogen was added at a final concentration of 2.5 mM as (NH4)2SO4 or KNO3.

Melon and cucumber seeds were sprouted on germination paper in a 30°C incubator until transplanting to hydroponics after 4 d. Seedlings were placed in sponge holders in lids of black plastic containers, 4 plants per 750 ml solution. Plants were grown in a growth chamber with a mix of incandescent and fluorescent light at 300 μmol m−2 s−1. For cucumber, plants were pretreated in standard solution for 5 d before nutrient treatments for 3 d. For the -Cu fefe mutant rescue and WT controls, seedlings were grown without Cu from initial planting for 9 d. Plants for the +/- Cu RNA-seq experiment (Edisto and fefe) were collected at 9 d. For the +/- Fe RNA-seq experiment, wild-type (Edisto and snake melon) and fefe mutants were pretreated for 9 d on -Cu solution, and only fefe mutants that had green leaves were used for treatments of 3 d duration. The purpose for the -Cu pretreatment was to use only healthy fefe plants so that the transcriptome would reflect the Fe regulated genes in fefe rather than secondary effects of severe Fe deficiency.

For grafting experiments, melon seeds were germinated and planted as described above. After 2 d growth in the growth chamber in complete nutrient solution, seedlings were removed from sponge holders and stems were cut at an angle above the crown. Root stocks and scions were joined with a silicon grafting clip, plants were returned to hydroponics containers, and placed in a high humidity chamber under dimmed lighting (150 μmol m−2 s−1) for 7 d while the grafted tissues fused. Plants were then moved to a growth chamber for 3 d before Fe treatments were applied for 3 d. To avoid potential variation resulting from the circadian clock, sampling for ferric-chelate reductase activity or RNA was always performed between the hours of 14:00 and 16:00.

Ferric-chelate reductase activity

Root ferric reductase assays were performed for 30–60 min on individual roots, using 30 ml of an assay solution of 0.1 mM ferrozine (3-(2-Pyridyl)-5,6-diphenyl-1,2,4-triazine-4′,4′-disulfonic acid sodium salt, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA), 0.1 mM Fe(III)-EDTA and 1 mM MES buffer (pH 5.5) (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ, USA). Reduced Fe was calculated using absorbance at 562 nm using the extinction coefficient 28.6 mM−1 cm−1.

Mineral analysis

Iron and Cu concentrations were determined by ICP-MS as described previously (Waters & Troupe, 2012). To calculate total mineral quantity in each plant part and the sum of all parts, Fe and Cu contents were calculated by multiplying concentration by organ DW. Briefly, plant tissues were dried for at least 48 h at 60°C in a drying oven. Tissues were weighed and digested overnight at room temperature in 3 ml concentrated HNO3. Samples were then heated at 100°C for 2 h, followed by addition of 3 ml H2O2, then heated stepwise to 165°C until dryness. Residues were resuspended in 5 ml 1% HNO3 before ICP-MS.

cDNA identification

Primers for full-length cucumber IRT1 (Waters et al., 2007) were used with melon cDNA as a template to amplify a PCR product that was cloned and sequenced. The melon cDNA was 96% identical to cucumber IRT1. This transcript was Fe regulated as expected and was designated CmIRT1. A full-length ferric reductase cDNA was identified from Fe deficient roots by a degenerate primer RACE PCR strategy as described previously (Waters et al., 2002) and designated CmFRO1. Following release of the cucumber genome, three additional FRO genes were identified by BLAST; FRO2, Cucsa.108040.1; FRO4, Cucsa.260380.1 (http://www.phytozome.net), and FRO3, Csa008439 (http://www.icugi.org). Of these melon FRO genes, FRO1 is the ortholog of Arabidopsis FRO2. A FIT homolog (Csa015217) was identified by a BLAST search against the cucumber genome, version 1 (http://www.icugi.org/cgibin/ICuGI/genome/home.cgi?ver=1&organism=cucumber). Primers designed to amplify the full cDNA also amplified a single cDNA from melon, which was 97% identical at the nucleotide level and was Fe regulated, and was designated CmFIT.

Real time RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from roots using the Plant RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). RNA quality and concentration was determined by UV spectrophotometry. 1 μg of DNase-treated RNA (RNase-free DNase I, New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) was used for cDNA synthesis, using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (ABI, Foster City, CA, USA) with random hexamers at 2.5 μM final concentration. cDNA corresponding to 1.5–2.5 ng of total RNA was used in a 15 μl real-time PCR reaction performed in a MyIQ (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) thermal cycler using GoTaq qPCR MasterMix (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and 0.2 μM gene-specific primers (Supporting Information Table S1). The following standard thermal profile was used for all PCRs: 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 8 min; 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 56°C or 65°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 15 s. The Ct values for all genes were calculated using BioRad IQ5 System Software version 2.0 (BioRAD, Hercules, CA, USA). Gene expression was determined by normalizing to the Ct value of ubiquitin using the Livak method (Livak & Schmittgen, 2001), with the equation Relative Expression= 2−ΔΔCt, where ΔΔCt = (Cttarget gene (treatment 1) - Cttarget gene (control treatment)) - (CtUBQ (treatment 1) - CtUBQ (control treatment)).

Next Generation Sequencing and bioinformatics

Sources of RNA samples were described above. RNA-seq was performed using an Illumina HiSeq 2000 instrument. Barcoded libraries were constructed from 3 μg of root total RNA, with three biological replicate libraries per treatment. Replicates were run in separate lanes, with a total of six samples from different treatments in each lane. The reads are available as NCBI BioProject: PRJNA244361 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/244361). Because there is high synteny between melon and cucumber, and orthologues of these species are highly co-linear within large segments of chromosomes (Huang et al., 2009; González et al., 2010), the cucumber transcriptome was used as the reference for read mapping. The cucumber transcriptome sequence reference (cucumber_v2.cds.gz) was obtained from the cucurbit genomics database (ftp://www.icugi.org/pub/genome/cucumber/v2/). Sequencing reads from each sample were mapped to the reference database using BOWTIE2 (Langmead & Salzberg, 2012) with --local -N 1 options and cleaving 15 bp from each end of the reads. The BOWTIE2 output bam files were converted to sam format using SAMtools (Li et al., 2009). Perl scripts were written to extract read counts from the sam files and to create a read count data matrix. The data matrix was imported into R and analyzed using the Bioconductor package edgeR (Robinson et al., 2010). Read counts in each library were normalized to account for the library size using the calcNormFactors function, and tag-wise dispersions were estimated by using an empirical Bayes estimate, which is dependent on the initial dispersion estimates, through the estimateGLMTagwiseDisp and estimateGLMTrendedDisp functions, respectively. Differential expression was called for genes with an FDR moderated q-value (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995) less than 0.05, and also showed a 1.0 log fold change in expression and greater than 20 reads in at least one treatment.

Results

Physiological characterization the fefe mutant

When grown in standard nutrient solution, fefe cotyledons are green, but the first true leaf is chlorotic. We first corroborated previous reports (Nugent & Bhella, 1988; Nugent, 1994) that additional Fe supply could reverse leaf chlorosis. When three to five 2 μl droplets of 5 mM Fe(III)-EDDHA were applied to the second true leaf, that leaf and the emerging third true leaf had become green 36 h later (Fig. S1). Other forms of Fe also led to re-greening of fefe leaves, including ferric-EDTA, ferric citrate, ferric ammonium sulfate, and ferric nitrate, demonstrating that additional Fe was sufficient for reversal of the phenotype. A second test was to increase Fe availability in hydroponics by manipulating the nutrient solution in two ways. First, we used MES or HEPES buffer to maintain the solution at pH 5.0 or 7.1, respectively, while supplying either 1 μM or 20 μM Fe. In the WT these treatments had no discernible effect on leaf color (Fig. S1). The first leaf of fefe was chlorotic in all treatments except the low pH and high Fe combination. A second manipulation of the nutrient solution was to grow plants with either nitrate (NO −3) or ammonium (NH +4) as the sole N source. On NO −3, fefe plants had the usual chlorotic first leaf, whereas on NH +4, the first true leaf was green. Uptake of NH +4 uses a H+ antiport mechanism (von Wiren et al., 2000), resulting in net efflux of H+ into the nutrient solution, which in this case lowered the pH to below 4.0 and shifted Fe to the more readily available ferrous form. These manipulations support the idea that the defect in fefe is specific to Fe uptake.

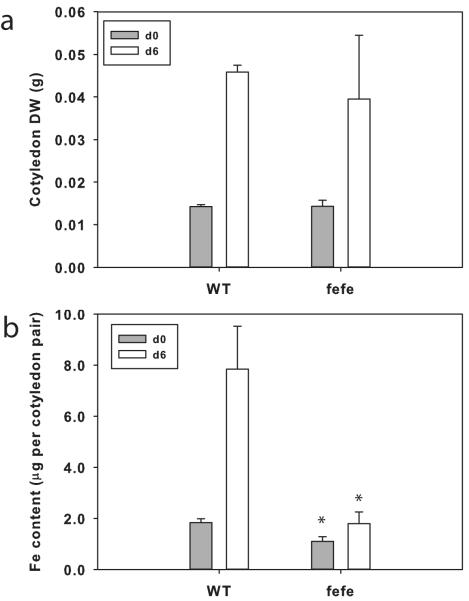

In previous work we showed that cucumber cotyledons grow (e.g. increase in DW) and accumulate Fe and certain other minerals over the first few days after germination (Waters & Troupe, 2012). To test whether fefe accumulated Fe or utilized Fe stored in cotyledons, we measured DW and Fe content of cotyledons in WT and the fefe mutant (Fig. 1). Cotyledons of fefe at germination were of similar size to WT (Fig. 1a), and had slightly less Fe content (Fig. 1b). Cotyledons of fefe grew similarly to those of WT, as evidenced by increased DW from germination to 6 d later. However, WT cotyledons gained over 5 μg of Fe, while fefe cotyledons did not gain significant amounts of Fe, nor did they decrease in Fe, demonstrating that fefe seedlings did not accumulate Fe from the nutrient solution during early growth.

Fig. 1.

Accumulation of iron (Fe) during seedling early growth of Cucumis melo. (a) Dry weight (DW) of wild type (WT) and fefe mutant cotyledon pairs (± SD) at planting (d0, closed bars) and after 6 d growth on complete nutrient solution (10 μM Fe, 0.5 μM Cu; open bars). (b) Fe content of cotyledon pairs (± SD) of WT and fefe mutant cotyledons at planting (d0; closed bars) and after 6 d growth (open bars) on complete solution. Significant difference between WT and fefe: *, P<0.05.

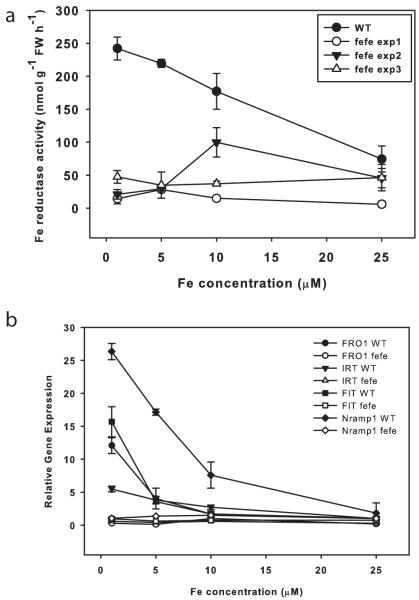

To corroborate previous reports that fefe roots do not induce ferric-chelate reductase activity, mutant and WT plants were grown on a range of Fe concentrations. WT roots had high ferric-chelate reductase activity at low Fe supply, but fefe had low activity at all Fe concentrations (Fig. 2a), demonstrating that inducible ferric-chelate reductase activity is diminished in fefe. However, on some occasions ferric-chelate reductase activity was somewhat elevated in fefe (e.g. Expt 2, 10 μM), which indicated that the ferric-chelate reductase protein is functional, but is not properly regulated. This led to the question of whether the fefe defect is specific to ferric reductase, or if other Fe uptake components are not expressed normally. To address this, we identified orthologs of Arabidopsis FRO2, IRT1, Nramp1, and FIT in melon and designed primers to measure transcript abundance by real-time RT-PCR. These genes were upregulated in low Fe conditions in WT, but not in fefe (Fig. 2b), suggesting that the fefe defect could be in the FIT gene, since melon FIT should regulate melon FRO1 (the Arabidopsis FRO2 ortholog) and IRT1 as in Arabidopsis and tomato (Ling et al., 2002; Colangelo & Guerinot, 2004). Sequencing of FRO1 and IRT1 cDNAs, and genomic DNA of FIT in both WT and fefe mutants did not reveal any polymorphisms that would result in premature stop codons or frame shifts, or amino acid changes that would be expected to abolish protein function, suggesting that the fefe gene is a regulator of Fe uptake that acts upstream of the primary Fe uptake genes and the FIT transcription factor.

Fig. 2.

The fefe mutant of Cucumis melo does not upregulate iron (Fe) uptake genes. (a) Root ferric-chelate reductase activity (± SD) after 3 d of treatment. Figure shows a representative experiment of wild type (WT) and three separate experiments of fefe roots over a range of Fe concentrations. (b) Quantitative real-time RT-PCR for FRO1, FIT, Nramp1, and IRT1 in WT and fefe mutant roots. Relative expression as normalized to ubiquitin and WT at 25 μM Fe.

As further characterization of the fefe mutant, we determined whether the defect was localized to roots or shoots. Reciprocal grafting was conducted with fefe and the parental wild type Edisto roots or shoots, and as controls each genotype was grafted to itself. Grafted plants with fefe roots were chlorotic, with either fefe or Edisto shoots, whereas fefe shoots were of a normal green color if grafted to WT rootstock (Fig. 3). Also, fefe roots of these plants did not induce ferric-chelate reductase activity regardless of shoot genotype. These results indicate that the fefe defect is in a regulatory component of the root system, and could result from an inability to receive a signal from the shoots, or from a signal transduction defect resulting in failure to respond and activate physiological and gene expression responses.

Fig. 3.

The fefe defect is localized to the roots of Cucumis melo as determined by grafting. (a) Shoot phenotype of grafted plants. Upper left, fefe scion grafted to fefe rootstock, upper right, fefe scion grafted to WT (Edisto) rootstock, lower left, wild type (WT) scion grafted to WT rootstock, lower right, WT scion grafted to fefe rootstock. (b) Root ferric-chelate reductase activity after transferring individual plants shown in (a) to -Fe solution for 3 d. x-axis indicates scion first and rootstock second.

Can Cu deficiency stimulate Fe accumulation?

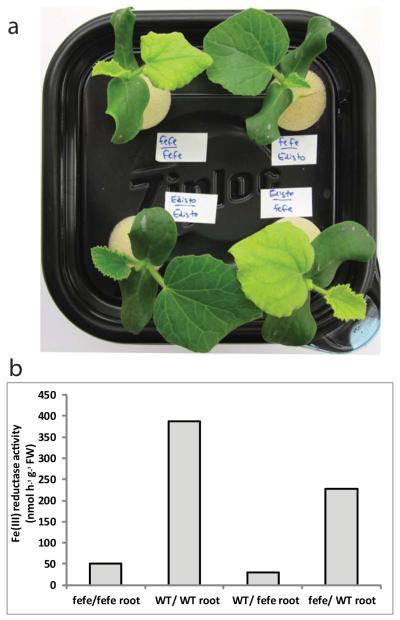

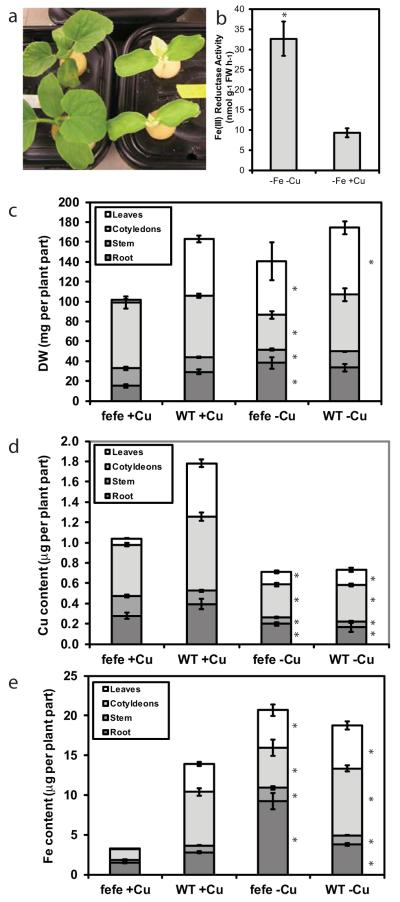

Since low Fe supply caused plants to accumulate additional Cu in leaves (Welch et al., 1993; Chaignon et al., 2002; Waters et al., 2012; Waters & Troupe, 2012), we hypothesized that under low Cu supply there would be a higher demand for Fe, which should lead to increased Fe uptake and rescue the fefe phenotype. This hypothesis was correct, as fefe plants grown without Cu (+Fe, −Cu) recovered within 9 d and had a green first leaf phenotype, while plants grown on complete solution (+Fe, +Cu) had the typical yellow first leaf (Fig. 4a). We then asked whether ferric-chelate reductase activity was increased in the fefe plants under Cu deficiency. When rescued fefe plants (green first leaf) were transferred to −Fe−Cu or −Fe+Cu treatments for 3 d, an approx.. 3-fold increase in root ferric-chelate reductase activity was observed in the -Cu treatment (Fig. 4b), although total activity was substantially lower than typically seen in WT Fe deficient roots. We also dissected fefe and WT plants grown with or without Cu for 12 d for mineral content analysis to determine the total quantity of Fe and Cu in the plants. The biomass of the plant parts showed that fefe affected growth of the first leaf primarily (Fig. 4c). On -Cu treatments, Cu content (Fig. 4d) was similar in both genotypes, and lower than plants on the +Cu treatment. In control solution, the total plant Cu content was lower in fefe than WT, primarily resulting from smaller leaves. There was no difference in Cu content between fefe and WT in the -Cu treatment. Total Fe content was much lower in fefe plants grown in complete solution, and this was most pronounced in leaves (Fig. 4e). The fefe and WT plants had a similar total quantity of Fe when Cu was withheld and fefe had recovered, demonstrating that Fe accumulation was stimulated by Cu deficiency. WT plants also accumulated more Fe under -Cu then +Cu conditions (Fig. 4e), even though DW was similar (Fig. 4c). Thus, the stimulation of Fe accumulation by Cu deficiency in the whole plant, which by definition would require increased uptake, occurred in both WT and fefe mutant plants.

Fig. 4.

Copper (Cu) deficiency of Cucumis melo stimulates iron (Fe) uptake and rescues the fefe phenotype. (a) Photograph of fefe plants grown without Cu (left) and on complete nutrient solution (right). (b) Root ferric-chelate reductase activity (± SD) after transferring rescued fefe plants to -Fe-Cu or -Fe+Cu solution for 3 d. (c–e) Stacked bar graphs of (c) dry weight (DW), (d) Cu content, and (e) Fe content of plant parts for fefe and wild type (WT) plants (± SE) grown with or without Cu. Significant difference between +Cu and -Cu treatments: *, P<0.05.

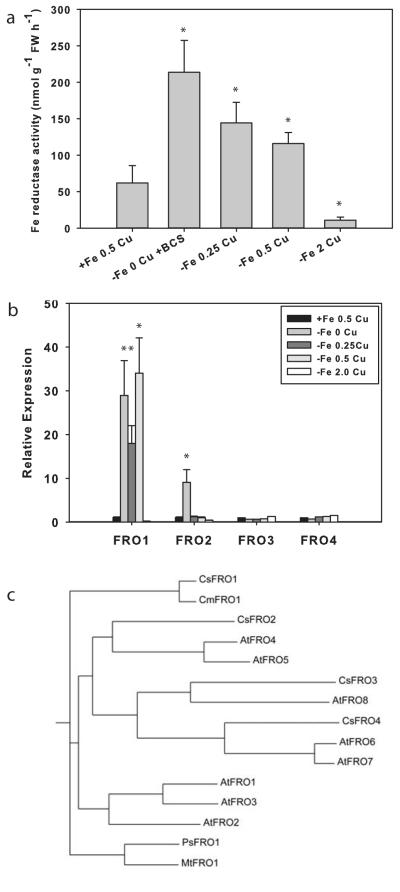

Because both WT and fefe plants accumulated additional Fe under Cu deficiency, and Cu deficient fefe plants had increased ferric-chelate reductase activity (Fig. 4), we determined which FRO gene(s) responded to each metal. We first addressed this question in cucumber since the cucumber and melon genomes are highly homologous (Huang et al., 2009; González et al., 2010), and the cucumber genome has been sequenced (Huang et al., 2009) and annotated. Plants were treated with complete or -Fe solutions with a range of Cu concentrations, because ferric-chelate reductase activity is sensitive to Cu supply (Waters & Armbrust, 2013). Root reductase activity was highest in -Fe-Cu roots, and was slightly lower as Cu was supplied at 0.25 and 0.5 μM (Fig. 5a). Expression of FRO1, the primary ferric-chelate reductase (Waters et al., 2007), was elevated at 0, 0.25, and 0.5 μM Cu (Fig. 5b). Ferric-chelate reductase activity decreased as Cu supply increased, and did not tightly correspond to FRO1 expression, which did not decrease at 0.5 μM Cu. However, at 2.0 μM Cu, both root ferric-chelate reductase activity and FRO1 expression were abolished, and had lower values than those of control (+Fe, 0.5 μM Cu) roots. The -Fe 2.0 μM Cu treated roots may have been suffering from Cu toxicity, as Cu is toxic at lower levels in Fe deficient roots (Waters & Armbrust, 2013). The other three FRO genes in the cucumber genome have not been previously characterized. FRO3 and FRO4 were not elevated over control in any of the treatments, suggesting that they are not regulated by Fe or Cu status. However, FRO2 was upregulated in the -Fe-Cu treatment, but not in the -Fe+Cu treatments, demonstrating that FRO2 is regulated by Cu status. This gene is also most closely related to Arabidopsis FRO4 and FRO5 (Fig. 5c), which are Cu regulated Cu(II) reductases involved in Cu uptake (Bernal et al., 2012).

Fig. 5.

Iron (Fe) and copper (Cu) regulation of cucumber (Cucumis sativus) FRO genes. (a) Root ferric-chelate reductase activity (± SD) after 3 d of treatment for control (+Fe, 0.5 μM Cu) and -Fe with a range of Cu supply. (b) Quantitative real-time RT-PCR of expression (± SD) of four cucumber FRO genes from the plants in (a). Significant difference between control and treatments: *, P<0.05. (c) Phylogenetic tree drawn from ClustalW alignment of FRO protein sequences from cucumber (Cs), melon (Cm), Arabidopsis (At), Pisum sativum (Ps), and Medicago truncatula (Mt).

Transcriptomic characterization of Fe and Cu regulated genes

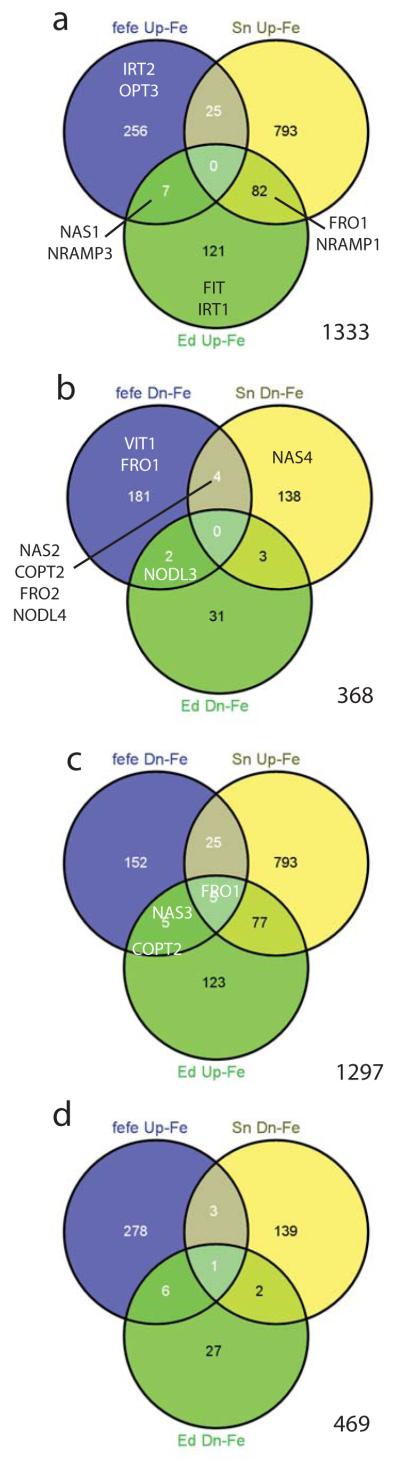

Since Fe homeostasis is disrupted in the fefe mutant and the fefe phenotype is rescued by Cu deficiency, we next performed RNA-seq transcriptome analysis of fefe and WT roots under control (+Fe, +Cu) conditions and Fe and Cu deficiency. To determine Fe deficiency differentially expressed genes, we used the fefe mutant and two WT lines, Edisto and snake melon. The total number of Fe deficiency upregulated genes (1333) combined from all three genotypes (Fig. 6) exceeded the number of downregulated genes (368). 91% of upregulated genes and 98% of the Fe deficiency downregulated genes had differential expression in roots of only one genotype, similar to a previous microarray study with three accessions of Arabidopsis (Stein & Waters, 2012). Of Fe deficiency upregulated genes (Fig. 6a), none were upregulated in all three genotypes, and 7 and 25 were upregulated in fefe and Edisto, and fefe and snake melon roots, respectively (Table S2). 82 genes were upregulated in the two wild types but not in fefe (Table S3). These genes reflect loss of regulation in fefe and likely include most or all of the fefe regulated transcriptome. The genes that were upregulated by Fe deficiency in only one genotype are shown in Table S4. Of the Fe deficiency downregulated genes (Fig. 6b), none were down in roots of all three genotypes, while 2 and 4 were downregulated in fefe and Edisto, and fefe and snake melon, respectively, and 3 that were downregulated in both WTs (Table S5). Genes that were downregulated in Fe deficient roots in only one genotype are shown in Table S6. We also noted that many genes that were upregulated in one or both of the two WTs were significantly downregulated in fefe (Fig. 6c). This opposite regulation pattern was present for 5 genes that were upregulated in both WTs, and for 25 and 5 that were upregulated in snake melon and Edisto, respectively (Table S7). For the other opposite expression pattern, genes upregulated in fefe and downregulated in the wildtypes (Fig. 6d), one gene was downregulated for both WTs and upregulated in fefe, and 3 and 6 were downregulated in snake melon and Edisto, respectively (Table S7).

Fig. 6.

Venn diagrams for iron (Fe) regulated genes in fefe and two wild-type (WT) Cucumis melo accessions, Edisto (Ed) and snake melon (sn). Genes of interest are shown in the appropriate set or overlap of sets. (a) Genes upregulated under Fe deficiency, (b) genes downregulated under Fe deficiency, (c) genes downregulated in fefe and upregulated in WTs, (d) genes upregulated in fefe and downregulated in WTs.

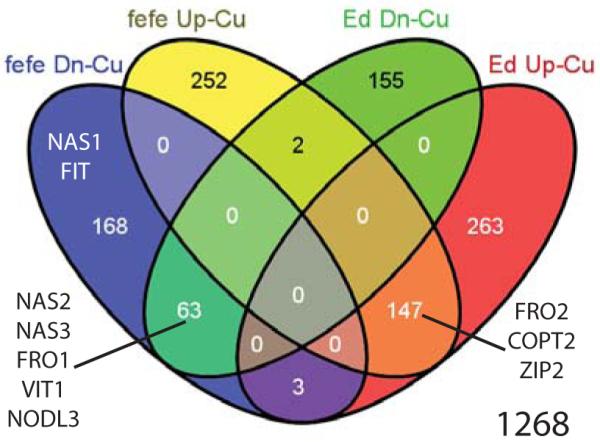

We also used RNA-seq to quantify changes in root transcript abundance in fefe and the WT Edisto in response to 9 d of Cu deficiency (Fig. 7). In common to both WT and fefe, 147 genes were upregulated and 63 were downregulated (Table S8). Of Cu deficiency regulated genes, 16.6% had the same expression pattern in both mutant and WT, which was substantially greater than the 1.5% of Fe regulated genes that were in common between fefe and Edisto specifically (Fig. 6), suggesting that the root Cu transcriptome is not as drastically affected by the fefe mutation as the root Fe transcriptome. Additionally, only 5 genes had opposite regulation patterns (e.g. upregulated in one genotype and downregulated in the other) under Cu deficiency (Table S8). Supplementary table are presented for genes that were upregulated (Table S9) or downregulated (Table S10) in only one genotype.

Fig. 7.

Venn diagram of genes upregulated (Up) or downregulated (Dn) under copper (Cu) deficiency in fefe or wild type (WT) Edisto (Ed) Cucumis melo roots. Genes of interest are shown in the appropriate set or overlap of sets.

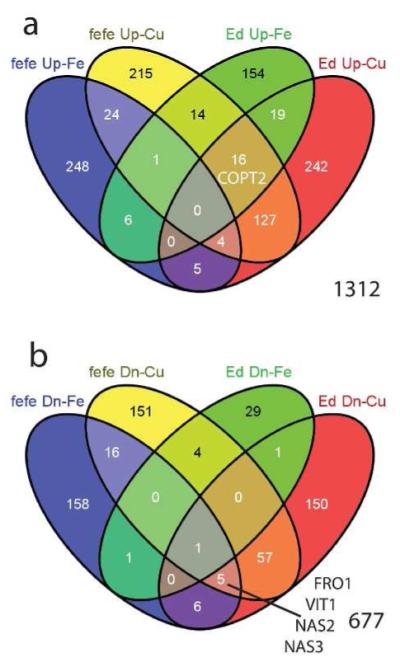

We next compared the Fe and Cu deficiency differentially expressed genes to determine which genes were regulated by both metals in roots (Fig. 8). We identified 83 genes of 1312 (6.3%) that were upregulated by both Fe and Cu in various combinations (Fig. 8a, Table S11). 29 of 677 genes (4.2%) were downregulated by Fe and/or Cu deficiency in either or both fefe and Edisto (Fig. 8b, Table S12). To determine potential effects of Fe and Cu deficiencies on metal homeostasis, we focused on genes from known metal-related gene families. Cucumber coding sequence annotations from the ICuGI database, based on the closest Arabidopsis thaliana BLAST hit, were organized by gene family. Normalized read counts for each significantly upregulated or downregulated gene are presented in Table 1. Notably, several genes of the classical Strategy I Fe deficiency response (orthologs of FRO2, IRT1, Nramp1, and FIT) were upregulated in one or both WTs, but were not upregulated or were downregulated in fefe. Of note, the IRT gene in melon that was most orthologous to AtIRT1 function was most homologous to Arabidopsis AtIRT2 sequence.

Fig. 8.

Venn diagrams to identify number of overlapping genes in iron (Fe) and copper (Cu) regulated genes of Cucumis melo roots. (a) Genes upregulated in fefe and Edisto (Ed) under Fe deficiency and/or Cu deficiency, (b) genes downregulated in fefe and Edisto (Ed) under Fe deficiency and/or Cu deficiency. Genes of interest are shown in the appropriate set or overlap of sets.

Table 1.

Gene expression in wild type (WT) melon (Cucumis melo) and fefe roots. RNA-seq reads were mapped to cucumber transcripts (Cucumber Locus ID)

| Normalized Read Counts | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| logFC (−Fe/+Fe) | logFC (− Cu/+Cu) |

fefe | WT (Edisto) |

WT (snake) |

fefe | WT (Edisto) |

|||||||||||

| Melo n Gen e Nam e |

Cucumbe r Locus ID |

Top Arabidopsis thaliana Hit | fefe | WT (Ed ) |

WT (sn ) |

fefe | WT (Ed ) |

+F e |

− Fe |

+F e |

− Fe |

+F e |

− Fe |

+C u |

− Cu |

+C u |

− Cu |

| Ferric Reductase/oxidase family | |||||||||||||||||

| AT5G47910.1 RBOHD | |||||||||||||||||

| Csa3M84 5500.1 |

AT5G47910.1 RBOHD (RESPIRATORY BURST OXIDASE HOMOLOGUE D); NAD(P)H oxidase |

1.1 | 1.2 | 1.7 | 13 46 |

19 76 |

36 50 |

66 71 |

75 16 |

15 84 7 |

60 58 |

11 25 6 |

10 66 |

30 05 |

|||

| FRO 1 |

Csa5M17 5770.1 |

AT1G23020.1 FRO3; ferric- chelate reductase |

- 1.7 |

4.3 | 2.7 | - 5.0 |

- 3.3 |

50 0 |

15 4 |

41 0 |

80 58 |

29 1 |

18 13 |

17 37 |

44 | 11 47 |

12 3 |

| FRO 2 |

Csa3M18 3380.1 |

AT5G23980.1 FRO4 (FERRIC REDUCTION OXIDASE 4); ferric- chelate reductase |

- 2.1 |

- 2.6 |

3.8 | 2.6 | 28 61 |

66 3 |

10 04 |

16 78 |

10 5 |

17 | 20 1 |

24 24 |

18 94 |

93 37 |

|

| Csa1M42 3270.1 |

AT2G24520.1 AHA5 (Arabidopsis H(+)-ATPase 5); ATPase |

1.1 | 65 72 |

80 12 |

50 25 |

10 30 3 |

45 60 |

73 87 |

42 29 |

32 79 |

62 39 |

44 69 |

|||||

|

Metal

Transporters |

|||||||||||||||||

| Nra mp3 |

Csa2M42 3700.1 |

AT2G23150.1 NRAMP3 (NATURAL RESISTANCE- ASSOCIATED MACROPHAGE PROTEIN 3); inorganic anion transmembrane transporter/ manganese ion transmembrane transporter/ metal ion transmembrane transporter |

1.1 | 1.2 | 61 11 |

13 05 5 |

12 41 |

27 13 |

16 09 |

22 36 |

24 68 |

17 11 |

99 4 |

70 9 |

|||

| Nra mp1 |

Csa6M38 2880.1 |

AT1G80830.1 NRAMP1 (NATURAL RESISTANCE- ASSOCIATED MACROPHAGE PROTEIN 1); inorganic anion transmembrane transporter/ manganese ion transmembrane transporter/ metal ion transmembrane transporter |

3.7 | 1.7 | 17 4 |

84 | 77 5 |

97 03 |

16 88 |

54 38 |

16 7 |

89 | 30 78 |

12 80 |

|||

| IRT1 | Csa1M70 7110.1 |

AT4G19680.2 IRT2; iron ion transmembrane transporter/ zinc ion transmembrane transporter |

1.4 | - 2.5 |

38 6 |

24 8 |

42 8 |

11 17 |

24 6 |

47 3 |

80 1 |

12 8 |

61 4 |

39 5 |

|||

| IRT2 | Csa6M51 7980.1 |

AT4G19690.2 IRT1 (iron- regulated transporter 1); cadmium ion transmembrane transporter/ copper uptake transmembrane transporter/ iron ion transmembrane transporter/ manganese ion transmembrane transporter/ zinc ion transmembrane transporter |

3.0 | 12 | 10 3 |

3 | 4 | 6 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||||

| ZIP2 | Csa7M16 2550.1 |

AT5G59520.1 ZIP2; copper ion transmembrane transporter/ transferase, transferring glycosyl groups / zinc ion transmembrane transporter |

1.3 | 2.2 | 14 0 |

72 | 54 | 46 | 78 | 81 | 42 | 85 | 43 | 17 0 |

|||

| ZIP5 | Csa4M61 8490.1 |

AT1G05300.1 ZIP5; cation transmembrane transporter/ metal ion transmembrane transporter |

- 1.0 |

83 | 81 | 40 2 |

45 7 |

17 3 |

16 2 |

25 | 31 | 14 0 |

55 | ||||

| COP T2 |

Csa1M52 6820.1 |

AT3G46900.1 COPT2; copper ion transmembrane transporter/ high affinity copper ion transmembrane transporter |

- 2.5 |

1.8 | - 1.6 |

1.4 | 1.7 | 27 8 |

49 | 57 | 19 4 |

47 | 15 | 87 | 18 4 |

17 9 |

51 5 |

| Csa3M69 6860.1 |

AT3G08040.1 FRD3 (FERRIC REDUCTASE DEFECTIVE 3); antiporter/ transporter |

- 3.9 |

- 2.4 |

65 | 50 | 3 | 19 | 17 9 |

12 | 20 | 3 | 6 | 14 | ||||

| Csa7M42 8170.1 |

AT3G08040.1 FRD3 (FERRIC REDUCTASE DEFECTIVE 3); antiporter/ transporter |

1.3 | 14 25 |

13 22 |

79 2 |

18 60 |

12 69 |

13 90 |

15 43 |

77 4 |

22 11 |

14 17 |

|||||

| Csa3M18 0310.1 |

AT4G23030.1 MATE efflux protein-related |

1.0 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 2.8 | 74 | 70 | 15 8 |

31 6 |

30 4 |

62 0 |

74 1 |

14 64 |

70 | 42 3 |

||

| Csa2M40 4760.1 |

AT1G65730.1 YSL7 (YELLOW STRIPE LIKE 7); oligopeptide transporter |

1.0 | 11 29 |

63 3 |

16 60 |

13 35 |

23 45 |

46 11 |

33 2 |

33 3 |

60 2 |

43 6 |

|||||

| Csa2M40 4780.1 |

AT1G48370.1 YSL8 (YELLOW STRIPE LIKE 8); oligopeptide transporter |

1.0 | 71 | 44 | 12 4 |

10 8 |

18 3 |

36 6 |

27 | 31 | 47 | 43 | |||||

| Csa3M23 8100.1 |

AT5G53550.1 YSL3 (YELLOW STRIPE LIKE 3); oligopeptide transporter |

- 1.2 |

1.1 | 1.7 | 41 6 |

28 9 |

15 5 |

11 4 |

31 8 |

14 0 |

14 9 |

27 2 |

14 4 |

40 4 |

|||

| Csa1M32 9900.1 |

AT5G53550.1 YSL3 (YELLOW STRIPE LIKE 3); oligopeptide transporter |

- 1.5 |

10 3 |

37 | 19 | 14 | 37 | 44 | 8 | 14 | 16 | 25 | |||||

| OPT 3 |

Csa1M18 0750.1 |

AT4G16370.1 ATOPT3 (OLIGOPEPTIDE TRANSPORTER); oligopeptide transporter |

2.1 | 32 99 |

14 59 2 |

45 7 |

87 2 |

48 4 |

74 2 |

14 48 |

74 0 |

20 1 |

24 1 |

||||

| Nicotianamine synthase family | |||||||||||||||||

| NAS 1 |

Csa2M03 4520.1 |

AT5G04950.1 NAS1 (NICOTIANAMINE SYNTHASE 1); nicotianamine synthase |

2.4 | 2.0 | - 2.7 |

50 1 |

27 31 |

21 | 86 | 17 | 9 | 16 6 |

22 | 42 | 18 | ||

| NAS 2 |

Csa1M42 3010.1 |

AT1G56430.1 NAS4 (NICOTIANAMINE SYNTHASE 4); nicotianamine synthase |

- 5.3 |

- 1.4 |

- 5.1 |

- 4.4 |

13 9 |

3 | 52 2 |

21 0 |

57 | 21 | 80 | 2 | 10 57 |

50 | |

| NAS 3 |

Csa2M03 4530.1 |

AT1G56430.1 NAS4 (NICOTIANAMINE SYNTHASE 4); nicotianamine synthase |

- 1.8 |

2.2 | - 3.5 |

- 3.2 |

15 0 |

44 | 27 1 |

12 15 |

60 2 |

46 9 |

32 4 |

23 | 52 0 |

54 | |

| NAS 4 |

Csa1M56 1410.1 |

AT1G56430.1 NAS4 (NICOTIANAMINE SYNTHASE 4); nicotianamine synthase |

- 2.2 |

- 3.3 |

- 1.7 |

16 9 |

81 | 75 | 39 | 80 | 17 | 92 | 8 | 54 | 14 | ||

| VIT1 family | |||||||||||||||||

| VIT1 | Csa5M55 0240.1 |

AT2G01770.1 VIT1 (vacuolar iron transporter 1); iron ion transmembrane transporter |

- 3.4 |

- 1.8 |

- 1.3 |

90 | 9 | 56 7 |

34 7 |

12 9 |

13 1 |

17 8 |

42 | 24 4 |

89 | ||

| NO DL1 |

Csa1M28 8020.1 |

AT4G30420.1 nodulin MtN21 family protein |

- 1.8 |

1.1 | 34 6 |

98 | 16 59 |

22 05 |

10 93 |

23 24 |

10 4 |

11 8 |

65 | 36 | |||

| NO DL2 |

Csa3M83 5770.1 |

AT5G40240.1 nodulin MtN21 family protein |

1.1 | 10 1 |

13 5 |

38 | 47 | 41 | 87 | 66 | 79 | 37 | 26 | ||||

| NO DL3 |

Csa6M41 1280.1 |

AT3G25190.1 nodulin, putative | - 4.6 |

- 1.8 |

- 1.4 |

- 1.0 |

62 | 3 | 29 5 |

80 | 12 4 |

68 | 15 3 |

48 | 92 8 |

39 2 |

|

| NO DL4 |

Csa7M32 5150.1 |

AT3G43660.1 nodulin, putative | - 2.7 |

- 1.3 |

35 | 5 | 37 | 27 | 27 | 11 | 31 | 24 | 64 | 64 | |||

|

Ferr

itin |

|||||||||||||||||

| Csa5M21 5130.1 |

AT2G40300.1 ATFER4 (ferritin 4); binding / ferric iron binding / oxidoreductase/ transition metal ion binding |

- 1.2 |

42 2 |

32 0 |

95 0 |

40 7 |

81 7 |

92 3 |

52 5 |

37 1 |

57 4 |

54 9 |

|||||

|

Transcription

factors |

|||||||||||||||||

| Csa1M07 4400.1 |

AT4G20970.1 basic helix-loop- helix (bHLH) family protein |

2.6 | 2.4 | 69 | 44 2 |

95 | 18 6 |

15 0 |

20 1 |

65 | 27 2 |

14 4 |

24 3 |

||||

| Csa1M58 9140.1 |

AT5G56960.1 basic helix-loop- helix (bHLH) family protein |

1.3 | 1.2 | 94 | 22 7 |

21 2 |

17 8 |

51 8 |

11 94 |

15 | 12 | 23 | 10 | ||||

| Csa2M19 3320.1 |

AT5G43650.1 basic helix-loop- helix (bHLH) family protein |

1.3 | 2.2 | 2.8 | 12 | 8 | 15 8 |

38 7 |

25 9 |

11 40 |

25 | 14 8 |

5 | 15 | |||

| Csa2M35 4790.1 |

AT4G33880.1 basic helix-loop- helix (bHLH) family protein/RSL2 |

4.9 | 4.5 | 10 | 2 | 2 | 57 | 1 | 23 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 1 | ||||

| Csa3M11 9500.1 |

AT1G01260.1 basic helix-loop- helix (bHLH) family protein |

1.0 | 1.3 | 62 7 |

67 6 |

13 42 |

24 32 |

15 69 |

30 72 |

15 73 |

22 62 |

42 6 |

91 4 |

||||

| Csa3M17 8580.1 |

AT5G51780.1 basix helix-loop- helix (bHLH) family protein |

2.0 | 37 | 25 | 10 | 14 | 39 | 15 5 |

1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||||

| Csa3M89 3390.1 |

AT5G65640.1 bHLH093 (beta HLH protein 93); DNA binding / transcription factor |

- 1.6 |

- 1.0 |

59 4 |

76 2 |

13 62 |

94 9 |

30 43 |

24 98 |

11 4 |

31 | 13 5 |

56 | ||||

| Csa4M64 2470.1 |

AT2G14760.1 basic helix-loop- helix protein / bHLH protein |

1.9 | 12 | 8 | 18 | 64 | 0 | 13 | 12 | 6 | 3 | 1 | |||||

| Csa5M42 0280.1 |

AT1G66470.1 basic helix-loop- helix (bHLH) family protein |

1.1 | 30 9 |

16 4 |

66 | 60 | 44 | 89 | 59 | 23 | 46 | 24 | |||||

| FIT | Csa6M14 8260.1 |

AT2G28160.1 FRU (FER-LIKE REGULATOR OF IRON UPTAKE); DNA binding / transcription factor |

1.9 | - 1.1 |

10 45 |

64 9 |

10 9 |

40 4 |

19 5 |

33 7 |

80 9 |

32 5 |

27 0 |

18 7 |

|||

| Csa6M49 7100.1 |

AT2G22750.2 basic helix-loop- helix (bHLH) family protein |

1.6 | 5 | 4 | 39 | 73 | 14 2 |

42 6 |

5 | 18 | 2 | 1 | |||||

| Csa6M49 7110.1 |

AT4G37850.1 basic helix-loop- helix (bHLH) family protein |

1.8 | 3.1 | 2.2 | 68 | 30 | 71 6 |

86 5 |

42 8 |

14 13 |

10 8 |

80 1 |

21 | 80 | |||

| Csa6M49 7120.1 |

AT4G37850.1 basic helix-loop- helix (bHLH) family protein |

30 | 16 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 11 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 7 | ||||||

| Csa3M116 720.1 |

AT2G44840.1 ERF13 (ETHYLENE-RESPONSIVE ELEMENT BINDING FACTOR 13); DNA binding / transcription factor |

2.4 | 2.7 | 3.8 | 6 | 2 | 91 | 23 1 |

12 0 |

60 3 |

67 | 34 5 |

3 | 32 | |||

| Csa3M11 6730.1 |

AT2G44840.1 ERF13 (ETHYLENE-RESPONSIVE ELEMENT BINDING FACTOR 13); DNA binding / transcription factor |

2.3 | 2.1 | 4 | 2 | 31 | 58 | 35 | 16 4 |

42 | 14 5 |

2 | 15 | ||||

| Csa5M15 5570.1 |

AT1G12610.1 DDF1 (DWARF AND DELAYED FLOWERING 1); DNA binding / sequence-specific DNA binding / transcription factor |

1.0 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 2 | 2 | 29 2 |

57 5 |

32 8 |

34 0 |

20 1 |

69 3 |

2 | 68 | |||

| Csa7M16 9070.1 |

AT4G39250.1 ATRL1 (ARABIDOPSIS RAD-LIKE 1); DNA binding / transcription factor |

5.0 | - 6.3 |

1 | 1 | 2 | 66 | 10 | 13 | 1 | 0 | 25 | 0 | ||||

| Csa3M18 0260.1 |

AT4G25490.1 CBF1 (C- REPEAT/DRE BINDING FACTOR 1); DNA binding / transcription activator/ transcription factor |

- 1.6 |

1.1 | 1.0 | 3.6 | 30 | 9 | 81 | 16 8 |

15 3 |

14 7 |

18 55 |

30 44 |

10 2 |

10 60 |

||

| Csa3M71 0870.1 |

AT1G80840.1 WRKY40; transcription factor |

1.3 | 1.2 | 3.4 | 25 5 |

17 9 |

12 44 |

25 45 |

23 33 |

57 75 |

31 29 |

58 44 |

24 8 |

23 03 |

|||

| Csa7M07 3700.1 |

AT4G34410.1 RRTF1 ({REDOX RESPONSIVE TRANSCRIPTION FACTOR 1); DNA binding / transcription factor |

1.4 | 2.1 | 1.6 | 4.1 | 2 | 2 | 19 | 47 | 21 | 90 | 26 9 |

67 0 |

9 | 13 6 |

||

| Csa2M29 7760.1 |

AT5G50080.1 DNA binding / transcription factor |

1.5 | 1.2 | 15 0 |

96 | 24 9 |

68 8 |

16 9 |

38 3 |

71 | 32 | 86 | 52 | ||||

| Csa3M40 5510.1 |

AT5G48150.1 PAT1 (phytochrome a signal transduction 1); signal transducer/ transcription factor |

1.3 | 1.5 | 3.6 | 24 8 |

26 4 |

55 8 |

13 49 |

14 42 |

39 93 |

46 08 |

74 12 |

28 1 |

31 95 |

|||

| Csa6M42 5790.1 |

AT3G44260.1 CCR4-NOT transcription complex protein, putative |

1.3 | 1.6 | 3.0 | 65 | 57 | 26 9 |

29 5 |

10 24 |

24 43 |

10 30 |

26 23 |

10 4 |

70 1 |

|||

Significant log fold-change (logFC) is shown for fefe, Edisto (Ed) and snake melon (sn) for Fe treatments, and for Edisto and fefe for Cu treatments. Normalized read counts for each transcript are also shown.

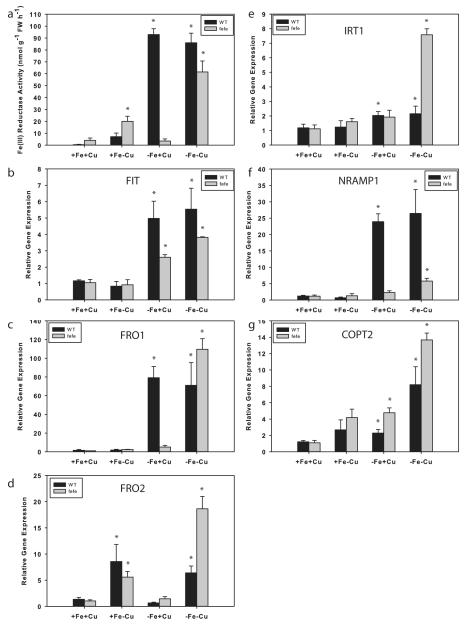

Synergy between Fe and Cu regulation of Fe uptake genes

We next examined Fe and Cu regulation of root ferric-chelate reductase activity and used real-time RT-PCR to measure expression of the melon IRT1, FRO1, FRO2, FIT, Nramp1, and COPT2 genes to determine whether the combination of Fe and Cu deficiencies acted synergistically. WT and fefe plants grown on control (+Fe+Cu) solution had low ferric-chelate reductase activity (Fig. 9a), and baseline gene expression (Fig. 9b–g). As before, fefe roots did not increase ferric-chelate reductase activity under -Fe+Cu conditions, and did not have elevated FRO1 expression, while WT roots had high ferric-chelate reductase activity and high expression of FRO1. Under the +Fe-Cu treatment, ferric-chelate reductase activity was elevated in both fefe and WT, and FRO2 expression was increased in both fefe and WT roots, similar to the cucumber results (Fig. 5). FIT expression increased in both genotypes under -Fe+Cu treatment but not in the +Fe-Cu treatment (Fig. 9b), suggesting that FRO2 expression was responsible for most of the ferric-chelate reductase activity in Cu deficient roots in a FIT-independent manner. This also suggested that fefe roots can sometimes increase FIT expression, but this alone is not enough to induce FRO1 (Fig. 9c) or root ferric chelate reductase activity. Ferric-chelate reductase activity was highly elevated under the simultaneous -Fe-Cu treatment in both WT and fefe, and FIT and FRO1 expression were elevated in fefe. Both WT and fefe also had upregulated FRO2 expression in the -Fe-Cu treatment. These results show that fefe is unable to upregulate FRO1 normally, that is, under Fe deficiency, but can upregulate FRO1 under simultaneous Fe and Cu deficiency. Also, these results demonstrate that FRO2 is a Cu regulated gene that encodes a protein with ferric-chelate reductase activity, and is regulated by Cu. IRT1 was slightly (~2-fold) upregulated in the +Fe-Cu and -Fe+Cu treatments (Fig. 9e), and more highly under simultaneous Fe and Cu deficiency, especially in fefe. Nramp1 was upregulated only in WT roots by Fe deficiency (Fig. 9f), and only in fefe by simultaneous Fe and Cu deficiency. COPT2 was upregulated in both genotypes in response to both Fe deficiency, and responded strongly to simultaneous Fe and Cu deficiencies (Fig. 9g).

Fig. 9.

Regulation of melon (Cucumis melo) root ferric-chelate reductase activity and iron (Fe) uptake gene expression by Fe and copper (Cu). (a) Ferric-chelate reductase activity (± SD) in roots after 3 d treatment with 10 μM Fe and 0.5 μM Cu (+Fe+Cu), -Fe+Cu, +Fe-Cu, or -Fe-Cu solutions. Wild type (WT), black bars; fefe mutant, grey bars. Gene expression in roots of the plants above, for (b) FIT, (c) FRO1, (d) FRO2, (e) IRT1, (f) NRAMP1, and (g) COPT2. Significant difference between control (+Fe+Cu) and treatments: *, P<0.05.

Discussion

The overall objective of this study was to use the fefe mutant as a tool to increase understanding of Fe uptake regulation and how Fe–Cu crosstalk influences Fe uptake regulation. Here, we showed that the fefe lesion is specific to roots and FeFe is required for normal expression of Fe uptake genes, but is not homologous to FIT. Thus, fefe likely encodes a transcription factor or signaling molecule that functions upstream of FIT and Fe uptake gene regulation. We also demonstrated Cu-regulated, fefe-independent Fe accumulation, by showing that Cu deficiency stimulates FRO2 expression and plant Fe accumulation in quantities sufficient to reverse the fefe phenotype, but not upregulation of FIT or FRO1. Simultaneous Fe and Cu deficiencies acted synergistically in the fefe mutant to restore ferric-chelate reductase activity and allow expression of FRO1.

The fefe gene is upstream of Fe uptake genes

We showed that Fe applied to leaves, or increased Fe supply to roots could rescue the fefe phenotype (Fig.S1), which suggested that the fefe defect results in Fe deficiency specifically. Using grafting, it was clear that fefe shoots functioned normally, but the roots did not respond to Fe deficiency (Fig. 3). This indicates that the fefe defect does not affect shoot-to-root communication processes (Vert et al., 2003; Garcia et al., 2013), at least at the shoot origin of such a signal, although it is possible that fefe roots receive a signal that they are unable to perceive or respond to. Another possibility was that lack of energy resulting from the low photosynthetic capacity of the chlorotic fefe leaves rendered it unable to produce or send a root-to-shoot signal. By growing fefe plants in conditions to allow green leaves before Fe deficiency treatments, we ruled out this possibility.

The bHLH transcription factors FER in tomato (Ling et al., 2002) and FIT in Arabidopsis (Colangelo & Guerinot, 2004) are required for upregulation of Fe uptake genes under Fe deficiency. Here, we showed that, like FER and FIT, the fefe mutation also affected expression of Fe uptake genes. In addition, fefe did not properly regulate the expression of melon FIT and a number of other genes that were Fe regulated in one or both WT genotypes (Table 1, Figs 2, 9). The upregulation of FIT under Fe deficiency was abolished in the fefe mutant in Fig. 2 and the RNA-seq experiments (Table 1), but there was some upregulation of FIT in Fig. 9. This is similar to Arabidopsis FIT expression, where in some experiments FIT transcripts are increased under Fe deficiency (Colangelo & Guerinot, 2004; Buckhout et al., 2009; Garcia et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2010), and in others they are not (Dinneny et al., 2008; Long et al., 2010; Ivanov et al., 2012; Stein & Waters, 2012). Regardless, the apparent increased FIT expression alone was insufficient to increase FRO1 (orthologous to FRO2 in A.t) and IRT expression (Fig. 9 and Colangelo & Guerinot, 2004; Yuan et al., 2008). FIT protein activity is not entirely dependent on transcriptional control, as short-lived ‘active’ forms of FIT protein have been described, and this post-translational control for the protein depends on Fe status (Meiser et al., 2011; Sivitz et al., 2011). Sequencing of the fefe FIT locus and RNA-seq sequences of WT and fefe FIT transcripts, as well as some level of FIT upregulation in fefe in Fig. 9 ruled out FIT as the mutant gene in fefe. Together, these results show that the fefe mutant has a defect in regulation of root Fe uptake responses that is upstream of known Fe uptake genes and potentially upstream of or in a partner of FIT, making this a valuable mutation for furthering our understanding of Fe uptake regulation. So far, subgroup Ib bHLH transcription factors bHLH038, bHLH039 (Yuan et al., 2008) and bHLH100 and bHLH101 (Wang et al., 2013) have been shown to physically interact with FIT, but single mutants of these genes have no discernable phenotype (Wang et al., 2007; Sivitz et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2013), while the fefe phenotype is severe. Thus, it is likely that the fefe gene is not homologous to these partner bHLHs, or there is less redundancy in the melon genome for subgroup Ib bHLH genes.

Cu deficiency stimulates Fe uptake

Under Cu deficiency, FeSOD genes and miR398 transcripts are upregulated, and CuSOD genes are downregulated (Yamasaki et al., 2007; Abdel-Ghany & Pilon, 2008; Bernal et al., 2012). We showed an opposite regulatory pattern under Fe deficiency, which led to the Fe/Cu tradeoff hypothesis, that Fe deficiency upregulates Cu accumulation to supply Cu for CuSOD proteins to replace downregulated FeSOD proteins (Waters et al., 2012). Here, we hypothesized that Cu deficiency might stimulate Fe uptake, and the results supported this hypothesis (Fig. 4). We showed that Cu deficiency stimulated the accumulation of Fe in WT and fefe plants and rescued the fefe phenotype, and also resulted in increased FRO2 expression and ferric-chelate reductase activity (Figs 5, 9). These results corroborate earlier work that showed Cu deficiency induced ferric-chelate reductase activity (Norvell et al., 1993; Welch et al., 1993; Cohen et al., 1997; Romera et al., 2003), and expands that work by demonstrating Cu regulation of the FRO2 genes of cucumber and melon (Figs 5, 9, Table 1), which are most closely related to Cu regulated Arabidopsis FRO4 and FRO5 genes (Bernal et al., 2012). This is in contrast to regulation of the FRO1 gene, which was upregulated by Fe deficiency but not Cu deficiency. Since the fefe mutant has a root localized defect (Fig. 3) that prevented normal upregulation of FIT, FRO1, and IRT1 (Figs 2, 9, Table 1) and normal accumulation of Fe under standard conditions (Figs S1, 1, 4), rescue of this mutant by withholding Cu further supports that Fe uptake is increased under Cu deficiency, consistent with the Fe/Cu tradeoff hypothesis. Cu deficient WT melon plants also accumulated additional Fe (Fig. 4), showing that this phenomenon is not limited to the fefe mutant.

Cu and Fe deficiency effects on metal homeostasis genes

As indicated by differential expression of key metal homeostasis genes (Table 1) under Fe and Cu deficiency, it is clear that deficiency of either Fe or Cu affected overall metal homeostasis. One nicotianamine synthase (NAS) gene was downregulated under Fe deficiency, and all three NAS genes were downregulated under Cu deficiency. Nicotianamine is an intracellular metal chelator that has been implicated in homeostasis of Fe and Cu (Takahashi et al., 2003; Curie et al., 2009; Klatte et al., 2009). It is not clear if the localization of expression of these three NAS genes overlap, or if they are preferentially expressed in certain cell types or organelles. Yellow-stripe-like (YSL) and MATE genes (e.g. FRD3) are potentially involved in intraplant translocation (DiDonato et al., 2004; Green & Rogers, 2004; Waters et al., 2006), and changes in expression of YSL3 and MATE orthologs could result in altered distribution of Fe and Cu under metal deficiency to help plant adaptation to stress. Such redistribution has been observed for Cu and Fe (Ravet et al., 2011; Bernal et al., 2012; Page et al., 2012). Under Cu deficiency, Cu uptake genes FRO2, COPT2, and ZIP2 were upregulated, while Fe uptake genes FRO1 and IRT1 had decreased expression. This suggests that Fe uptake by Cu deficient melon does not use the primary Fe uptake system, although it is not obvious from the root gene expression data which specific genes could play this role.

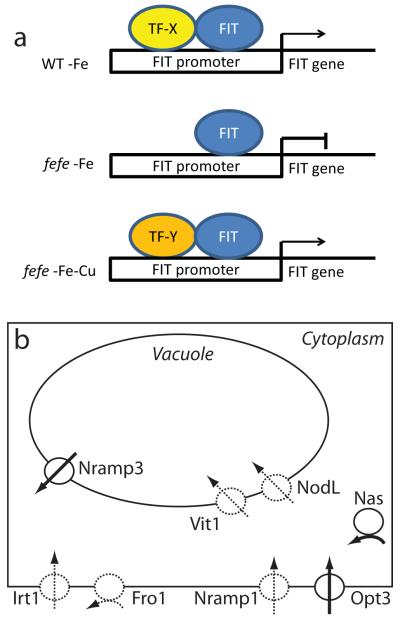

Analysis of fefe provides new insights into Fe and Cu homeostasis

Gene expression levels in the fefe mutant provide new insight into Fe and Cu homeostasis. First, FRO2 can still be upregulated by Cu deficiency in fefe (Fig. 9). Regulation of FIT and FRO1 was defective under Fe deficient conditions (Figs 2, 9, Table 1). Under simultaneous Fe and Cu deficiency, ferric-chelate reductase activity and expression of FIT, FRO1, FRO2, IRT1, and COPT2 were synergistically upregulated in fefe (Fig. 9). It is not clear how this synergistic regulation occurs, but high expression of FIT in fefe suggests that the FIT protein could be involved. One possibility is that a bHLH protein that multimerizes with FIT under Fe deficiency is defective in fefe, but an alternative bHLH protein becomes present under Cu deficiency (Fig. 10a) and allows FIT expression or activation of FIT and expression of FIT target genes. Several bHLH genes were upregulated in Cu deficient melon roots (Table 1) and some bHLH transcripts were also Cu regulated in Arabidopsis (Yamasaki et al., 2009; Bernal et al., 2012).

Fig. 10.

Models of effects of the fefe mutation of Cucumis melo. (a) Model of potential FIT regulation under single iron (Fe) or copper (Cu) deficiencies, or simultaneous Fe and Cu deficiency. In wild type (WT), FIT upregulates its own expression with a required partner bHLH protein, which is missing or mutated in fefe. A substitute partner protein is upregulated by Cu deficiency, which allows the fefe mutant to transcribe FIT and activate FIT targets. (b) Model of metal homeostasis alterations in fefe roots based on transcript abundance. Dashed lines represent lower expression relative to WT, solid lines represent higher expression relative to WT. Transport of Fe into a generic cell is represented for Fro1, Irt1, Nramp1, and Opt3 proteins, transport of Fe into the vacuole is represented by Vit1 and NodL proteins, transport out of a vacuole is represented by Nramp3 protein, and cytoplasmic synthesis of nicotianamine is represented by Nas protein.

Altered transcript abundance (regardless of fold-changes) for metal homeostasis genes in fefe (Table 1) indicate potential alterations in cellular metal metabolism. A model of these alterations is shown in Fig. 10, where loss of expression of Fe uptake genes (FRO1, IRT1, and Nramp1) leads to higher expression of OPT3, potentially to increase Fe uptake, and higher NAS1 expression to produce increased nicotianamine. This model also includes altered expression of vacuolar Fe transporters, with the efflux transporter Nramp3 (Lanquar et al., 2005) more highly expressed, and the influx transporters VIT1 (Kim et al., 2006) and NODL (Gollhofer et al., 2011) at lower abundance, since Fe would be moved out of the vacuole in Fe deficient plants, rather than into the vacuole for storage.

Conclusions and future directions

The Fe/Cu tradeoff hypothesis is that when Fe or Cu is limiting, accumulation of the other metal is stimulated to compensate. This hypothesis was supported by increased Cu accumulation under Fe deficiency (Waters et al., 2012), and results here showed that a fefe-independent, Cu-regulated Fe uptake system is present in melon plants. Thus, there are unidentified specific Fe and Cu uptake systems that fulfill this demand, rather than the normal uptake systems acting non-specifically. The fefe mutant is a potential tool to identify the Cu-regulated Fe uptake system. The fefe mutant could also further understanding of Fe uptake regulation, since the fefe protein is likely to be upstream of FIT in the Fe signaling pathway, or works as a partner with the FIT protein. We are actively working to identify the fefe gene in melon by positional cloning. The specific mechanism of Fe sensing and signaling of Fe status is unknown, so discovery of the fefe gene will facilitate understanding of Fe signaling.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Grace Troupe and Colin Nogowski for technical assistance, and Raghuprakash Kastoori Ramamurthy for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported in part by a USDA-NIFA grant (2014-67013-21658) to B.M.W. The University of Nebraska Medical Center DNA Sequencing Core receives partial support from the NCRR (1S10RR027754-01, 5P20RR016469, RR018788-08) and the National Institute for General Medical Science (NIGMS, 8P20GM103427, GM103471-09). This publication’s contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or NIGMS.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article.

Please note: Wiley Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting information supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the New Phytologist Central Office.

References

- Abdel-Ghany SE, Pilon M. MicroRNA-mediated systemic down-regulation of copper protein expression in response to low copper availability in Arabidopsis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283:15932–15945. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801406200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alscher RG, Erturk N, Heath LS. Role of superoxide dismutases (SODs) in controlling oxidative stress in plants. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2002;53:1331–1341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological) 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal M, Casero D, Singh V, Wilson GT, Grande A, Yang H, Dodani SC, Pellegrini M, Huijser P, Connolly EL, et al. Transcriptome sequencing identifies SPL7-regulated copper acquisition genes FRO4/FRO5 and the copper dependence of iron homeostasis in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell. 2012;24:738–761. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.090431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckhout TJ, Yang TJW, Schmidt W. Early iron-deficiency-induced transcriptional changes in Arabidopsis roots as revealed by microarray analyses. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:147. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhead JL, Reynolds KAG, Abdel-Ghany SE, Cohu CM, Pilon M. Copper homeostasis. New Phytologist. 2009;182:799–816. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaignon V, Di Malta D, Hinsinger P. Fe-deficiency increases Cu acquisition by wheat cropped in a Cu-contaminated vineyard soil. New Phytologist. 2002;154:121–130. [Google Scholar]

- Chen YX, Shi JY, Tian GM, Zheng SJ, Lin Q. Fe deficiency induces Cu uptake and accumulation in Commelina communis. Plant Science. 2004;166:1371–1377. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen CK, Norvell WA, Kochian LV. Induction of the root cell plasma membrane ferric reductase. An exclusive role for Fe and Cu. Plant Physiology. 1997;114:1061–1069. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.3.1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colangelo EP, Guerinot ML. The essential basic helix-loop-helix protein FIT1 is required for the iron deficiency response. The Plant Cell. 2004;16:3400–3412. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.024315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curie C, Cassin G, Couch D, Divol F, Higuchi K, Jean M, Misson J, Schikora A, Czernic P, Mari S. Metal movement within the plant: contribution of nicotianamine and yellow stripe 1-like transporters. Annals of Botany. 2009;103:1–11. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcn207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Pozo T, Cambiazo V, González M. Gene expression profiling analysis of copper homeostasis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2010;393:248–252. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.01.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiDonato RJ, Jr., Roberts LA, Sanderson T, Eisley RB, Walker EL. Arabidopsis Yellow Stripe-Like2 (YSL2): a metal-regulated gene encoding a plasma membrane transporter of nicotianamine-metal complexes. Plant Journal. 2004;39:403–414. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinneny JR, Long TA, Wang JY, Jung JW, Mace D, Pointer S, Barron C, Brady SM, Schiefelbein J, Benfey PN. Cell identity mediates the response of Arabidopsis roots to abiotic stress. Science. 2008;320:942–945. doi: 10.1126/science.1153795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia MJ, Lucena C, Romera FJ, Alcantara E, Perez-Vicente R. Ethylene and nitric oxide involvement in the up-regulation of key genes related to iron acquisition and homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2010;61:3885–3899. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia MJ, Romera FJ, Stacey MG, Stacey G, Villar E, Alcantara E, Perez-Vicente R. Shoot to root communication is necessary to control the expression of iron-acquisition genes in Strategy I plants. Planta. 2013;237:65–75. doi: 10.1007/s00425-012-1757-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gayomba SR, Jung H-i, Yan J, Danku J, Rutzke MR, Bernal M, Kramer U, Kochian L, Salt D, Vatamaniuk OK. The CTR/COPT-dependent copper uptake and SPL7-dependent copper deficiency responses are required for basal cadmium tolerance in A. thaliana. Metallomics. 2013;5:1262. doi: 10.1039/c3mt00111c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollhofer J, Schläwicke C, Jungnick N, Schmidt W, Buckhout TJ. Members of a small family of nodulin-like genes are regulated under iron deficiency in roots of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry. 2011;49:557–564. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González V, Rodríguez-Moreno L, Centeno E, Benjak A, Garcia-Mas J, Puigdomènech P, Aranda M. Genome-wide BAC-end sequencing of Cucumis melo using two BAC libraries. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:1–11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green LS, Rogers EE. FRD3 controls iron localization in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology. 2004;136:2523–2531. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.045633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell B, Gutteridge JMC. Biologically relevant metal ion-dependent hydroxyl radical generation. FEBS Letters. 1992;307:108–112. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80911-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansch R, Mendel RR. Physiological functions of mineral micronutrients (Cu, Zn, Mn, Fe, Ni, Mo, B, Cl) Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2009;12:259–266. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Li R, Zhang Z, Li L, Gu X, Fan W, Lucas W, Wang X, Xie B, Ni P, et al. The genome of the cucumber, Cucumis sativus L. Nature Genetics. 2009;41:1275–1283. doi: 10.1038/ng.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov R, Brumbarova T, Bauer P. Fitting into the harsh reality: regulation of iron-deficiency responses in dicotyledonous plants. Molecular Plant. 2012;5:27–42. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssr065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakoby M, Wang HY, Reidt W, Weisshaar B, Bauer P. FRU (BHLH029) is required for induction of iron mobilization genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Letters. 2004;577:528–534. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.10.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolley VD, Brown JC, Nugent PE. A genetically related response to iron deficiency stress in muskmelon. Plant and Soil. 1991;130:87–92. [Google Scholar]

- Kim SA, Punshon T, Lanzirotti A, Li LT, Alonso JM, Ecker JR, Kaplan J, Guerinot ML. Localization of iron in Arabidopsis seed requires the vacuolar membrane transporter VIT1. Science. 2006;314:1295–1298. doi: 10.1126/science.1132563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klatte M, Schuler M, Wirtz M, Fink-Straube C, Hell R, Bauer P. The analysis of Arabidopsis nicotianamine synthase mutants reveals functions for nicotianamine in seed iron loading and iron deficiency responses. Plant Physiology. 2009;150:257–271. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.136374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliebenstein DJ, Monde R-A, Last RL. Superoxide dismutase in Arabidopsis: an eclectic enzyme family with disparate regulation and protein localization. Plant Physiology. 1998;118:637–650. doi: 10.1104/pp.118.2.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurepa J, Bueno P, Kampfenkel K, VanMontagu M, VandenBulcke M, Inze D. Effects of iron deficiency on iron superoxide dismutase expression in Nicotiana tabacum. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry. 1997;35:467–474. [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nature Methods. 2012;9:357–U354. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanquar V, Lelièvre F, Bolte S, Hamès C, Alcon C, Neumann D, Vansuyt G, Curie C, Schröder A, Krämer U, et al. Mobilization of vacuolar iron by AtNRAMP3 and AtNRAMP4 is essential for seed germination on low iron. Embo Journal. 2005;24:4041–4051. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling HQ, Bauer P, Bereczky Z, Keller B, Ganal M. The tomato fer gene encoding a bHLH protein controls iron-uptake responses in roots. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2002;99:13938–13943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212448699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long TA, Tsukagoshi H, Busch W, Lahner B, Salt DE, Benfey PN. The bHLH transcription factor POPEYE regulates response to iron deficiency in Arabidopsis roots. The Plant Cell. 2010;22:2219–2236. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.074096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meiser J, Lingam S, Bauer P. Posttranslational regulation of the iron deficiency basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor FIT is affected by iron and nitric oxide. Plant Physiology. 2011;157:2154–2166. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.183285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee I, Campbell NH, Ash JS, Connolly EL. Expression profiling of the Arabidopsis ferric chelate reductase (FRO) gene family reveals differential regulation by iron and copper. Planta. 2006;223:1178–1190. doi: 10.1007/s00425-005-0165-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myouga F, Hosoda C, Umezawa T, Iizumi H, Kuromori T, Motohashi R, Shono Y, Nagata N, Ikeuchi M, Shinozaki K. A heterocomplex of iron superoxide dismutases defends chloroplast nucleoids against oxidative stress and is essential for chloroplast development in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell Online. 2008;20:3148–3162. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.061341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norvell WA, Welch RM, Adams ML, Kchian LV. Reduction of Fe(III), Mn(III) and Cu(II) chelates by roots of pea (Pisum sativum L.) or soybean (Glycine max) Plant and Soil. 1993;156:123–126. [Google Scholar]

- Nugent P. Iron chlorotic melon germplasm C940-fe. Hortscience. 1994;29:50–51. [Google Scholar]

- Nugent PE, Bhella H. A new chlorotic mutant of muskmelon. Hortscience. 1988;23:379–381. [Google Scholar]

- Page MD, Allen MD, Kropat J, Urzica EI, Karpowicz SJ, Hsieh SI, Loo JA, Merchant SS. Fe sparing and Fe recycling contribute to increased superoxide dismutase capacity in iron-starved Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. The Plant Cell. 2012;24:2649–2665. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.098962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paolacci AR, Celletti S, Catarcione G, Hawkesford MJ, Astolfi S, Ciaffi M. Iron deprivation results in a rapid but not sustained increase of the expression of genes involved in iron metabolism and sulfate uptake in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) seedlings. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology. 2013;56:88–100. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perea-García A, Garcia-Molina A, Andrés-Colás N, Vera-Sirera F, Pérez-Amador MA, Puig S, Peñarrubia L. Arabidopsis copper transport protein COPT2 participates in the cross talk between iron deficiency responses and low-phosphate signaling. Plant Physiology. 2013;162:180–194. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.212407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilon M, Ravet K, Tapken W. The biogenesis and physiological function of chloroplast superoxide dismutases. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta-Bioenergetics. 2011;1807:989–998. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pineau C, Loubet S, Lefoulon C, Chalies C, Fizames C, Lacombe B, Ferrand M, Loudet O, Berthomieu P, Richard O. Natural variation at the FRD3 MATE transporter locus reveals cross-talk between Fe homeostasis and Zn tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genetics. 2012;8:e1003120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puig S, Andres-Colas N, Garcia-Molina A, Penarrubia L. Copper and iron homeostasis in Arabidopsis: responses to metal deficiencies, interactions and biotechnological applications. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2007;30:271–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.01642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravet K, Danford FL, Dihle A, Pittarello M, Pilon M. Spatiotemporal analysis of copper homeostasis in Populus trichocarpa reveals an integrated molecular remodeling for a preferential allocation of copper to plastocyanin in the chloroplasts of developing leaves. Plant Physiology. 2011;157:1300–1312. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.183350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romera FJ, Frejo VM, Alcántara E. Simultaneous Fe- and Cu-deficiency synergically accelerates the induction of several Fe-deficiency stress responses in Strategy I plants. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry. 2003;41:821–827. [Google Scholar]

- Sancenon V, Puig S, Mira H, Thiele DJ, Penarrubia L. Identification of a copper transporter family in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Molecular Biology. 2003;51:577–587. doi: 10.1023/a:1022345507112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivitz A, Grinvalds C, Barberon M, Curie C, Vert G. Proteasome-mediated turnover of the transcriptional activator FIT is required for plant irondeficiency responses. The Plant Journal. 2011;66:1044–1052. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivitz AB, Hermand V, Curie C, Vert G. Arabidopsis bHLH100 and bHLH101 control iron homeostasis via a FIT-independent pathway. PloS one. 2012;7:e44843. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein RJ, Waters BM. Use of natural variation reveals core genes in the transcriptome of iron-deficient Arabidopsis thaliana roots. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2012;63:1039–1055. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M, Terada Y, Nakai I, Nakanishi H, Yoshimura E, Mori S, Nishizawa M. Role of nicotianamine in the intracellular delivery of metals and plant reproductive development. Plant Cell. 2003;15:1263–1280. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vert GA, Briat JF, Curie C. Dual regulation of the Arabidopsis high-affinity root iron uptake system by local and long-distance signals. Plant Physiology. 2003;132:796–804. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.016089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Wiren N, Gazzarrini S, Gojont A, Frommer WB. The molecular physiology of ammonium uptake and retrieval. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2000;3:254–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HY, Klatte M, Jakoby M, Baumlein H, Weisshaar B, Bauer P. Iron deficiency-mediated stress regulation of four subgroup Ib BHLH genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta. 2007;226:897–908. doi: 10.1007/s00425-007-0535-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N, Cui Y, Liu Y, Fan H, Du J, Huang Z, Yuan Y, Wu H, Ling H-Q. Requirement and functional redundancy of Ib subgroup bHLH proteins for iron deficiency responses and uptake in Arabidopsis thaliana. Molecular plant. 2013;6:503–513. doi: 10.1093/mp/sss089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y-H, Garvin DF, Kochian LV. Rapid induction of regulatory and transporter genes in response to phosphorus, potassium, and iron deficiencies in tomato roots. Evidence for cross talk and root/rhizospheremediated signals. Plant Physiology. 2002;130:1361–1370. doi: 10.1104/pp.008854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters BM, Armbrust LC. Optimal copper supply is required for normal plant iron deficiency responses. Plant Signaling & Behavior. 2013;8:e26611. doi: 10.4161/psb.26611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters BM, Blevins DG, Eide DJ. Characterization of FRO1, a pea ferricchelate reductase involved in root iron acquisition. Plant Physiology. 2002;129:85–94. doi: 10.1104/pp.010829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters BM, Chu HH, DiDonato RJ, Roberts LA, Eisley RB, Lahner B, Salt DE, Walker EL. Mutations in Arabidopsis Yellow Stripe-Like1 and Yellow Stripe-Like3 reveal their roles in metal ion homeostasis and loading of metal ions in seeds. Plant Physiology. 2006;141:1446–1458. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.082586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters BM, Lucena C, Romera FJ, Jester GG, Wynn AN, Rojas CL, Alcantara E, Perez-Vicente R. Ethylene involvement in the regulation of the H+- ATPase CsHA1 gene and of the new isolated ferric reductase CsFRO1 and iron transporter CsIRT1 genes in cucumber plants. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry. 2007;45:293–301. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters BM, McInturf SA, Stein RJ. Rosette iron deficiency transcript and microRNA profiling reveals links between copper and iron homeostasis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2012;63:5903–5918. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters BM, Troupe GC. Natural variation in iron use efficiency and mineral remobilization in cucumber (Cucumis sativus) Plant and Soil. 2012;352:185–197. [Google Scholar]

- Welch RM, Norvell WA, Schaefer SC, Shaff JE, Kochian LV. Induction of iron(III) and copper(II) reduction in pea (Pisum sativum L.) roots by Fe and Cu staus: Does the root-cell plasmalemma Fe(III)-chelate reductase perform a general role in regulating cation uptake? Planta. 1993;1993:555–561. [Google Scholar]