Abstract

We hypothesized that presence of the s allele in the promoter region of the serotonin transporter (5-HTTLR) would moderate the effect of early cumulative SES risk on epigenetic change among African American youth. Contrasting hypotheses regarding the shape of the interaction effect were generated using vulnerability and susceptibility frameworks and applied to data from a sample of 388 African American youth. Early, cumulative SES risk assessed at 11–13 years based on parent report interacted with presence of the s allele to predict differential methylation assessed at age 19. Across multiple tests, a differential susceptibility perspective rather than a diathesis stress framework best fit the data for genes associated with depression, consistently demonstrating greater epigenetic response to early cumulative SES risk among s allele carriers. A pattern consistent with greater impact among s allele carriers also was observed using all CpG sites across the genome that were differentially affected by early cumulative SES risk. We conclude that the s allele is associated with increased responsiveness to early cumulative SES risk among African American youth, leading to epigenetic divergence for depression-related genes in response to exposure to heightened SES risk among s allele carriers in a “for better” or “for worse” pattern.

Keywords: methylation, genetics, depression, 5-HTTLPR, SES risk

Poverty and economic hardship have a range of long-term effects on child development (Conger, Wallace, Sun, Simons, McLoyd, & Brody, 2002), resulting in both physiological effects (Evans, Chen, Miller, & Seeman, 2012) as well as a range of social and family consequences (Maholmes & King, 2012). It is particularly noteworthy, therefore, that African American youth living in the Southern coastal plain are exposed to one of the most economically disadvantaged areas in the United States. As a consquence, substantial socio-economic status (SES) risk is experienced by a large percentage of youth at developmentally sensitive stages. This places them at risk for having shorter life expectancy (Braveman, Cubbin, Egerter, Williams, & Pamuk, 2010), and a range of health effects across the lifespan (Starfield, Robertson, & Riley, 2002). Although the mechanism conferring these adverse effects is not yet well understood, it has been proposed that effects may result, in part, from the ability of the early social environment to restructure the functioning of the human genome, resulting in long-term changes in transcriptional responses to future social stressors, and creating differential risk for adverse outcomes (Cole, 2011).

In addition to its practical importance, SES risk also provides a scientifically attractive index because measurement is based on relatively objective indicators that can be assessed prospectively and this source of stress is often relatively stable across childhood, with robust effects on a range of outcomes. Similarly, because of its potential relevance for regulating transcriptional response and its relative ease of measurement, DNA methylation has emerged as a potential mechanism of interest in accounting for gene by environment (GxE) effects. Using animal models, methylation also has been shown to be responsive to experimental manipulation via change in social status (Tung, Barreiro, Johnson, Hansen, Michopoulos, Toufexis, … Gilad, 2012) and parenting behavior (Champagne, Bagot, van Hasselt, Ramakers, Meaney, de Kloet, …Krugers, 2008; Trollope, Gutierrez-Mecinas, Mifsud, Collins, Saunderson, & Reul, 2011), further suggesting its potential developmental significance. Similarly for humans, evidence is emerging demonstrating that methylation is responsive to experimental manipulation of stress (Unternaehrer, Luers, Mill, Demster, Meyer,…Meinlschmidt , 2012). Accordingly, examination of the impact of genetic variability on epigenetic response to the environment may be facilitated by attention to cumulative SES risk as a stressor and DNA methylation as an index of epigenetic response.

One potential genetic moderator of interest is variation in the promoter of the serotonin transporter gene (SLC6A4), also referred to as the 5-HTT-linked polymorphic region (i.e., the 5-HTTLPR) which has long been viewed as a potential moderator of environmental stress (cf., Caspi, Hairiri, Holmes, Uher, & Moffitt, 2010). Perhaps more than any other candidate genotype, the 5HTTLPR has sponsored debate and interest regarding the nature of its effects (susceptibility vs. vulnerability; e.g., Belsky & Pluess, 2009), as well as the consistency and replicability of its effects and its mechanism(s) of effect (e.g. Caspi et al., 2010). Of particular interest has been the continuing debate regarding the potential moderating effect of 5-HTTLPR on life stress in the prediction of depression (Caspi, Sugden, Moffitt, Taylor, Craig, Harrington,..., & Poulton,2003; Risch, Herell, Lehner, Liang, Eaves, Hoh, … Merikangas, 2009). Unfortunately, examination of genetic moderation of environmental stress on depression is hampered by several methodological problems including the likelihood that there are biological mediators of stress effects on depression, such as epigenetic change, that have not been adequately characterized (see Szyf & Bick, 2013). Because such epigenetic mediators might be more directly, and strongly, affected by GxE effects than is depression, they have the potential to help clarify the nature of GxE effects. Accordingly, it is of particular interest to examine the 5-HTTLPR as a potential moderator of the long-term impact of early cumulative SES risk on epigenetic change, particularly epigenetic change in depression related genes. To the extent that the interaction of variation in the 5-HTTLPR with early cumulative SES risk can influence epigenetic change in depression related genes, this provides a plausible biological mechanism of long-term effect on depressive symptoms. Similarly, if effects are present for other developmentally important gene pathways, this would suggest relevance for a broader range of developmental outcomes.

The Role of the 5-HTTLPR in response to early, cumulative SES risk

The serotonin transporter gene, SLC6A4, is a key regulator of serotonergic neurotransmission, localized to 17p13. It consists of 14 exons and a single promoter. Variation in the promoter region of the gene, the 5-HTTLPR, results in two main variants, a short (s) and a long (l) allele. The s variant has 12 copies, and the l variant has 14 copies, of a 22-bp repeat element. Among African Americans, a non-negligible portion of the population carries an extra-long variant that has 16 copies. The s variant is associated with lower serotonin transporter transcription and reduced efficiency of serotonin reuptake, supporting its potential relevance for a range of serotonergic-linked outcomes (Carver, Johnson, & Joormann, 2008; Carver, Johnson, Joormann, LeMoult, & Cuccaro, 2011). Recent gene expression research indicates that the extra-long variant is not associated with reduced expression (Vijayendran, Cutrona, Beach, Brody, Russell, & Philibert, 2012), suggesting that contrasting the response of those carrying one or more short alleles to all others is appropriate in an African American Sample.

Evidence across multiple species and multiple methods indicates that genetic variation in the serotonin transporter is related to differential response to stress (Caspi et al., 2010), and encourages attention to the developmental implications of variation at the 5-HTTLPR in the context of elevated early cumulative SES risk. The s allele appears to be associated with increased connectivity between the amygdala and other brain regions (Heinz, Braus, Smolka, Wrase, Puls, Hermann, . . . Büchel, 2005), amplification of response to verbal and nonverbal threats (Isenberg, Silbersweig, Engelien, Emmerich, Malavade, Beattie, . . . Stern, 1999), and enhanced reactivity to punishment cues (Battaglia, Ogliari, Zanoni, Citterio, Pozzoli, Giorda, . . . Marino, 2005; Hariri & Holmes, 2006), and observational fear conditioning (Crişan, Pană, Vulturar, Heilman, Szekely, Drugă, et al., 2009). Because SES related risks are associated with reduced occupational and educational opportunity, frequent housing adjustments, changes in employment status for parents, as well as chronic exposure to interpersonal and institutional racism (Dressler, Oths, & Gravlee, 2005), greater activation in response to a range of perceived threats could be particularly consequential for youth exposed to elevated early cumulative SES risk. Underscoring the importance of perceived threat, children suffering from asthma who were from low SES backgrounds were more likely to interpret ambigous situations as threatening. However, gene expression was more strongly associated with the perception of threat than with SES itself (Chen, Miller, Walker, Arevalo, Sung, & Cole, 2008). Finally, s allele carriers may be disposed to rumination, directing preferential attention toward threat-related stimuli and disengaging from such stimuli with greater difficulty (Beevers, Wells, Ellis, & McGeary, 2009; Osinsky, Reuter, Küpper, Schmitz, Kozyra, Alexander, & Hennig, 2008). Taken together, this literature is consistent with the proposition that s allele carriers should be more hypervigilant and more reactive to early cumulative SES-associated risk than carriers of the l or vl genotype, and so may show stronger or more prolonged physiological and psychological response to high levels of early cumulative SES risks in childhood, leading to a greater impact of early cumulative SES risk on genomewide methylation and depression pathway specific methylation.

Functional Impact of Changes in Methylation

Changes in methylation can exert an effect on phenotypes by changing the accessibility of the protein coding portion of genes, or by changing the accessibility of promoter regions of genes, rendering them more or less available for genetic transcription, and so potentially changing function or developmental trajectory. Conversely, changes in methylation may change functioning of particular genes or cellular processes by facilitating or inhibiting the production of interfering proteins, which may also have potential regulatory impact. From the standpoint of understanding long-term changes in behavioral tendencies or health outcomes, patterns of methylation associated with early cumulative SES risks are of particular interest because some alterations in methylation may remain stable over a relatively long time in humans (Eckhardt Lewin,Cortese, Rakyan, Attwood, Burger, … Beck, 2006), making individual differences in methylation a potential biological marker of specific early environmental contributions to later outcomes (Fraga, Ballestar, Paz, Ropero, Setien, Ballestar, ….Esteller, 2005).

To the extent that epigenetic change results from the interaction of genotype with early cumulative SES risk, methylation should provide a sensitive index of GxE effects, and perhaps result in more replicable patterns (cf. Kinnally Capitanio, Leibel, Deng, LeDuc, Haghighi, et al., 2010) than can be observed using downstream behavioral phenotypes, like depression, that may depend critically on additional subsequent developmental and environmental processes. If so, examination of epigenetic change potentially may be able to tease apart subtle differences in patterns of effects (cf. Koenen, Uddin, Chang, Aiello, Wildman, Goldman, et al., 2011), such as the differences in patterns predicted by vulnerability and susceptibility frameworks. An added benefit is that a focus on epigentic change may decrease concerns about measurement and methodological confounds that sometimes render self-reported behavioral outcomes less compelling as critical tests of theory. Therefore, examination of hypothesized effects of interactions between early cumulative SES risk and 5-HTTLPR on the methylation of particular genetic pathways relevant to depression, and to developmental outcomes more broadly, may provide a useful supplement to a focus on behavioral outcomes, while also providing potential clues regarding etiology.

Vulnerability vs. Susceptibility

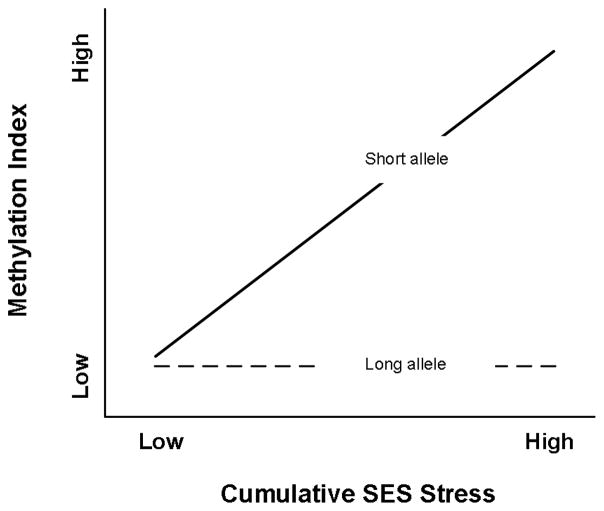

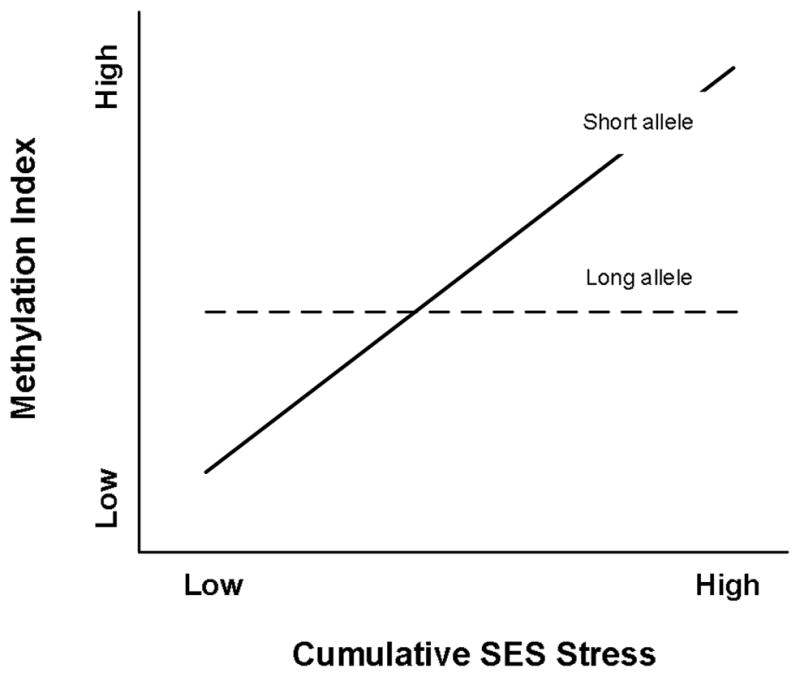

The observations reviewed above regarding the impact of the s allele on response to stress suggest a “vulnerability” or “diathesis-stress” model for understanding the impact of variation at 5-HTTLPR on response to conditions of high adversity. A genetic vulnerability model of 5-HTTLPR effects posits that s allele carriers are less resilient to high levels of stress, placing them at increased risk of adverse outcomes, perhaps including enhanced epigenetic change, in the context of elevated early cumulative SES stress. From a vulnerability perspective, there would be no reason to expect differences to emerge in the absence of heightened stress. Recently, however, an alternative to the vulnerability framework has been proposed in the form of a “susceptibility” framework. Although related, and generating several overlapping predictions, genetic susceptibility models differ from genetic vulnerability models in one key respect: they predict differential response to low-stress, positive environments as well. A susceptibility model of the impact of variation at 5-HTTLPR on epigenetic outcomes would posit that carriers of the s allele are genetically predisposed to be more susceptible than others to a range of environment influences. Accordingly, compared to others, s allele carriers would be expected to demonstrate greater propensity for epigenetic change in response to elevated early cumulative SES risk, a prediction that overlaps with those from a vulnerability model. In addition, s allele carriers would also be expected to demonstrate a significant difference in the opposite direction in response to lower-stress, positive early environments, leading to a “for better or worse” pattern of outcomes (Belsky & Puess, 2009; Boyce & Ellis, 2005). The difference between these two models is illustrated in Figures 1 and 2. Both vulnerability and susceptibility perspectives predict an interaction between 5-HTTLPR and early cumulative SES, and both predict greater impact of variation in early cumulative SES risk among s allele carriers. However, only the susceptibility model suggests that genotype will also be associated with significant differences in methylation at low levels of early, cumulative SES risk, and that the direction of difference between s carriers and those with only l or vl alleles when exposed to low levels of early cumulative SES risk will be the reverse of that seen at high levels of early cumulative SES risk.

Figure 1.

Prototypical Vulnerability Effect. No Difference in Outcome at Low Stress but Divergence at High Stress

Figure 2.

Prototypical Susceptibility Effect. Difference in Outcome at Low Stress and Divergence at High Stress, But in Opposite Directions

Quantification of Comparisons of Vulnerability and Susceptibility

Quantification of the differences between vulnerability and susceptibility models has been the focus of recent methodological work, resulting in suggestions that comparisons of vulnerability and susceptibility models should provide four key pieces of information. Such comparisons should: 1) provide significance tests for the interaction term in addition to visual inspection of the interaction plot, 2) report regions of significant difference between the simple slopes in addition to reporting the simple slopes and the significance of the simple slopes, 3) report the proportion of the area between the regression lines uniquely attributable to susceptibility effects in order to characterize the relative importance of susceptibility effects compared to vulnerability effects, and 4) introduce regression terms that directly examine potential nonlinearity and rule out nonlinear effects or significant interaction effects that might masquerade as crossover effects (Roissman, Newman, Fraley, Haltigan, Groh & Haydon, 2012).

Effect on the Depression Pathway

Prior work has identified a large set of genes associated with depression in at least one study (the KEGG pathways data bases; Kanehisa & Goto, 2000). In preliminary research we examined the impact of early cumulative SES risk on CpG sites across this pathway (Beach, Brody, Lei, Kim, Cui, & Philibert, 2013). A set of 50 CpG sites on the depression pathway were associated significantly with the main effect of early cumulative SES risk. An index reflecting degree of methylation across these 50 CpG sites fully mediated the impact of early cumulative SES risk on depressive symptoms in young adulthood (see Beach et al., 2013 for details). This “main effect” pathway linking early cumulative SES risk to depression provides an interesting starting point for the exploration of moderating effects of the 5-HTTLPR on epigenetic change. It provides a “main effect” that is neutral with regard to the presence or direction of any interaction with genotype. In addition, it provides a direction of “negative effect” from early cumulative SES risk to later depressive symptoms, providing interpretive advantages. Specifically, examination of the impact of the s allele on methylation across this “main effect” index can be evaluated both for direction and pattern of impact as well as for magnitude of impact.

An alternative approach to the comparison of susceptibility vs. vulnerability models is examination of an “interaction” index created from all CpG sites on the depression pathways that demonstrate a significant association with the interaction term, thereby capturing the full conditional effect of cumulative SES risk that varies by genotype. Although a negative (i.e., depressogenic) direction of effect cannot be specified a prioiri, it is possible to construct an interaction index that reflects the differential effect of cumulative SES risk on methylation of CpG sites on depression related genes for those with an s allele. This “interaction index” allows for an examination of the overall shape of the epigenetic “interaction effect,” contrasting impact for s allele carriers to that observed for those with only l or vl alleles. Because they represent independent tests of the shape of the interaction, consistent patterns between “main effect” and “interaction effect” indices suggests robustness of conclusions. Finally, because the 5-HTTLPR may have broader implications for developmental outcomes, it is useful to conduct exploratory analyses on a genome-wide basis to test the hypothesis that s allele carriers will show increased impact of early cumulative SES risk at the genome-wide level of analysis and that these effects may have broader developmental significance. Effects can be clarified further through characterization of the genetic pathways that are differentially changed.

Specific Hypotheses

Based on the foregoing considerations, we hypothesized that genetic variation at the 5-HTTLPR would act as either a vulnerability or a susceptibility factor in relation to the epigenetic impact of early cumulative SES risk. In particular, it was expected that variation at the 5-HTTLPR would interact with early cumulative SES risk to create differential methylation of the CpG sites on the depression “main effect” pathway, resulting in a stronger effect on the overall pathway, as well as a stronger effect of early cumulative SES risk on methylation when examined on a locus-by-locus basis. Further, we hypothesized that graphical representation would indicate either relatively equal effects of variation at 5-HTTLPR at low vs. high cumulative SES, indicating increased susceptibility among “s” allele carriers, or that it would indicate significant impact of variation at 5-HTTLPR only at high cumulative SES, indicating increased “vulnerability.” Second, we hypothesized that that variation at the 5-HTTLPR would interact with early cumulative SES risk to create differential DNA methylation of the depression “interaction effect” index, and would replicate the shape of the “main effect” pathway, confirming either vulnerability or susceptibility patterns. Specifically, we anticipated converging support for either increased susceptibility or increased vulnerability among “s” allele carriers. We also expected to replicate findings for increased magnitude of effect on methylation among s allele carriers relative to others. Third, we hypothesized that interaction of early cumulative SES risk with 5-HTTLPR on methylation across the genome would reflect differential change in pathways having neurodevelopmental significance and that s allele carriers would again show enhanced impact of the environmental variable on epigenetic reprogramming, this time at the genomewide level.

Method

Participants

African American primary caregivers in rural Georgia from each of N = 388 families participated in data collection and provided parental assessments of the economic circumstances of the family. Youth in the target age range were selected and provided genetic and epigenetic assessments. Target youth mean age was 11.7 years at the first assessment, 15.6 years at the time of genotyping base on Oragene collection, and 19.2 years at the time of epigenetic assessment based on a blood draw. The 388 families participating in the current study resided in nine rural counties in Georgia in which poverty rates are among the highest in the nation and unemployment rates are above the national average (Proctor & Dalaker, 2003). At the first assessment, primary caregivers in the sample worked an average of 39.9 hours per week, and 42.3% lived below federal poverty standards; the proportion was 56.3% at the time of epigenetic assessment. The increase in poverty is attributable to worsening economic conditions in the region. Of the youth in the sample, 55% were female. When targets were 11 years old, 78.8% of the caregivers had completed high school or earned a GED and median monthly family income was $1,710. Median monthly income was $1,648 at the age 19 data collection. The families, on average, could be characterized as working poor.

The analytic sample was drawn from a larger, ongoing data collection involving 667 families who had been recruited from lists of fifth-grade students provided by local schools (see Brody, Murry, Gerrard, Gibbons, Molgaard, McNair, et al., 2004 for a full description). Due to budgetary constraints we selected subsamples for biological assessment from the set of all youth available at the age 18 and 19 data collections (N = 561, a retention rate of 84%). We selected a random subsample of 500 to be assessed on a range of biological measures other than blood draws, and a subsample of these (N =399) were selected to participate in blood draws to allow methylation analyses. The 388 youth included in the current analyses participated in the blood draw and had complete data on all measures.

The full count (and proportion) of each genotype at the 5-HTTLPR is as follows: s,s- 21(0.054); s,l-127 (0.327); s,vl -4 (.01); l,l- 220 (.567); l,vl- 14 (.036); vl,vl- 2 (.005). The distribution of s vs. l alleles did not deviate from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (chi-square = .22, ns), suggesting no problem with differential allele drop out. Consistent with prior research (Brody, Beach, Chen, Obasi, Philibert, Kogan, et al., 2011; Hariri, Drabant, Munoz, Kolachana, Mattay, Egan, et al., 2005), genotyping results were used to form two groups of participants: those with only long allele or very long alleles (i.e., l,l, l,vl, vl,vl; coded as 0, n = 236, 60.8%) and those with either one or two copies of the short allele (i.e., s,s, s,l, s,vl; coded as 1, n = 152, 39.2%).

Procedure

All data were collected in participants’ residences using a standardized protocol that lasted approximately 2 hours at each wave of data collection. Two African American field researchers worked separately with the primary caregiver and the target youth. Interviews were conducted privately, with no other family members present or able to overhear the conversation. Primary caregivers consented to their own and the youths’ participation in the study, and the youths assented to their own participation and consented when they participated as adults.

Measures

Preadolescent early, cumulative SES risk

Three waves of data collected from primary caregivers when the target youths were 11, 12, and 13 years of age were used to establish level of early, cumulative SES risk across six indicators, with each indicator scored dichotomously (0 if absent, 1 if present; see Evans, 2003; Kim & Brody, 2005; Rutter, 1993; Sameroff, 1989; Werner & Smith, 1982; Wilson, 1987). Early cumulative SES risk was defined as the average number of risk factors across the three assessments, yielding an index with a theoretical range of 0 to 6 (m = 2.33, sd = 1.35). The six risk indicators were: (a) family poverty, defined as being below the poverty level, taking into account both family income and number of family members, (b) primary caregiver noncompletion of high school or an equivalent, (c) primary caregiver unemployment, (d) single-parent family structure, (e) family receipt of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, and (f) income rated by the primary caregiver as not adequate to meet all needs.

Genotyping

Most participants’ DNA (N = 343) was obtained at age 16 using Oragene DNA kits (Genotek; Calgary, Alberta, Canada). Participants rinsed their mouths with tap water, then deposited 4 ml of saliva in the Oragene sample vial. The vial was immediately sealed, inverted to allow mixing with stabilizing agents, and shipped via courier to a central laboratory in Iowa City, where samples were prepared according to the manufacturer’s specifications. Genotype at the 5-HTTLPR was determined for each sample as described previously (Bradley, Dodelzon, Sandhu, & Philibert, 2005) using the primers F-GGCGTTGCCGCTCTGAATGC and R-GAGGGACTGAGCTGGACAACCAC, standard Taq polymerase and buffer, standard dNTPs with the addition of 100 μM 7-deaza GTP, and 10% DMSO. The resulting polymerase chain reaction products were electrophoresed on a 6% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel, and products were visualized using silver staining. Two individuals blind to the study hypotheses and other information about the participants called the genotypes. For the N = 45 participants who were not successfully genotyped at age 16 using the Oragene method, genotypes were assayed in the same manner except using blood drawn at age 19.

Characterization of Methylation

Certified phlebotomists went to each participant’s home to draw a blood sample comprised of 4 tubes of blood for a total of 30 ml of whole blood. After the blood was drawn into serum separator tubes, it was shipped the same day to the Psychiatric Genetics Lab at the University of Iowa for preparation. After receipt of the blood at the University of Iowa, each tube was inspected to insure anticoagulation, and alloquots of blood were diluted 1:1 with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) pH 8.0. Mononuclear cell pellets were then separated from the remainder of the diluted blood specimen by centrifugation with ficoll at 400 g x 30 min., the mononuclear cell layer was removed from the tube using a transfer pipette, resuspended in a PBS solution, and briefly centrifuged again. The resulting cell pellet was resuspended in a 10% DMSO/RPMI solution and frozen at -80°C until use. Typical DNA yield for each pellet was between 10–15 μg of DNA.

Genome wide DNA methylation was assessed using the Illumina (San Diego, CA) HumanMethylation450 Beadchip under a subcontract to the University of Minnesota Genome Center (Minneapolis, MN) using coded DNA specimens. Two replicate samples of an internal control DNA were included in each plate to aid in assessment of batch and chip variation and to ensure correct handling of specimens. The average correlation coefficient between the replicate samples was greater than 0.99. DNA from the subjects were randomly assigned to “slides” holding DNA for 12 subjects, with groups of 8 slides representing the samples from a single 96 well plate that had been bisulfite converted in a single batch. The resulting data were inspected for complete bisulfite conversion and beta values (i.e. average methylation) for each CpG residue was determined using the GenomeStudio V2009.2; Methylation module Version 1.5.5, Version 3.2 (Illumina, San Diego). The resulting data were cleaned to remove those beta values whose detection p-values, an index of the likelihood that the observed sequence represents random noise, were greater than 0.05, using a PERL based algorithm. Data were inspected for outliers or confounds by plate and chip variables. With respect to this sample, >99.76 % of the 485,577 probes yielded statistically reliable data. Beta values were exported into Microsoft Excel, and initial analyses were conducted in R. To remove non-informative CpG sites as well as CpG sites of reduced potential predictive validity (Plume, Beach, Brody, Philibert; 2012), all CpG sites with average methylation less than 5% (47275 CpG sites) or greater than 95% (11632 CpG sites) were removed from the data set. This resulted in a data set of 426,670 informative CpG sites, with methylation values between 5% and 95%, from which data for our genome-wide analyses and our analyses of depression pathways was drawn.

Depression Pathway

To create the depression-related gene pathway score, we identified all genes associated with depression using the KEGG databases (Kanehisa & Goto, 2000). Because individual genes are of small effect and may be conditioned by other genes and risk factors, we followed the approach suggested in the KEGG database and included all genes appearing in GWAS and other investigations reporting a positive association, regardless of replication status. The depression pathway was identified as having 222 genes, 208 of which were assessed by the Illumina array. The association of methylation with cumulative SES-related risk was examined for all CpG sites on the 208 depression-related genes, allowing characterization of significance level and direction of association. Using the R-2.13.1 software package, with log10-transformed methylation values as the dependent measure, and no control variables, all CpG sites that were significantly associated with cumulative SES-related risk at the p < .01 level were included in the depression-SES pathway index, allowing identification of CpG sites that were elevated above the median in the direction of the association, and assignment of 0 vs 1 for each CpG site identified. For each CpG site significantly associated with SES-related risk, if the association was positive all those scoring above the median had pathway scores incremented by 1, if the association was negative all those scoring below the median had pathway scores incremented by 1. This yielded for each person the number of CpG sites that had been methylated in the direction associated with greater cumulative SES related risk. Summing across CpG sites resulted in an index score with a potential range of 0 to 50; the observed range was 1 to 47 (M = 24.619, SD = 10.79).

To create an index of association with the interaction term, all CpG sites that were significantly associated (p < .01) with the interaction of cumulative SES risk and presence of an s allele were included in the depression-interaction pathway (N = 300). This index is a count of CpG sites associated with cumulative SES risk. When cumulative SES risk was positively associated with methylation among s allele carriers, individuals above the mean of the distribution had index scores incremented by “1” and otherwise “0.” Conversely, for CpG sites that were negatively associated with cumulative stress among s allele carriers, index scores were incremented by “1” when the methylation value for the individual was below the mean, and “0” otherwise. Accordingly, the theoretical range of the “interaction pathway” score was 0 – 300 and the observed range was 11 – 289. Higher index scores were obtained by individuals who most closely conformed to the high cumulative SES risk, s allele, methylation prototype.

Results

Comparisons of s and l alleles

As an initial step in the analyses, we examined whether there were any significant differences between s allele carriers and other youth with regard to economic risks and related variables. As can be seen in Table 1, there were no significant differences between the two groups, although there was a trend for less parental unemployment among the s allele carriers.

Table 1.

T-tests and Descriptive Statistics Comparing Components of the Cumulative Risk Index for s allele carriers vs. those with no s allele.

| 5-HTTLPR | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| “S” allele (n =152 ) | “no S” allele (n =236) | ||||

|

|

|||||

| Variables | M | SD | M | SD | t-value |

| Age at the first assessment | 11.63 | .36 | 11.67 | .35 | −1.21 |

| Hours work per week | 39.97 | 11.16 | 39.89 | 10.89 | .064 |

| Percent female | .50 | .50 | .58 | .49 | −1.55 |

| Family incomes | 2071.52 | 1570.09 | 2039.71 | 1399.43 | .20 |

| Poverty 150% below limit | .71 | .46 | .67 | .47 | .88 |

| Parent unemployment | .18 | .38 | .25 | .43 | −1.63 |

| Single-parent family | .59 | .49 | .59 | .49 | .036 |

| TANFa receipt | .07 | .26 | .08 | .27 | −.29 |

| Parent education < high school | .53 | .50 | .51 | .50 | .35 |

| Inadequate income for needs | .37 | .48 | .33 | .47 | .82 |

Note. All components are not significantly different based on Student t-test (p < .05).

TANF = Temporary Assistance for Needy Families.

Effects on the “Main Effect” Depression Pathway

We next examined the impact of the interaction between presence of an s allele and presence of early cumulative SES risk on methylation of CpG sites on genes in the depression “main effect” pathway. In preliminary work (Beach et al., 2013), we found that higher values on the index were associated with greater earlier cumulative SES risk and with greater young adult depressive symptoms.

The impact of 5-HTTLPR on the association of early cumulative SES risk with level of the “main effect” methylation index is reported in Table 2. On step one, we regressed the depression “main effect” index score for each participant on early cumulative SES risk and 5-HTTLPR genotype (“s” allele carrier = 1 vs. “other = 0”), as well as age and gender. We then examined the moderating effect of variation at the 5-HTTLPR by entering the product of cumulative SES risk, centered, and 5-HTTLPR genotype on a second step. We used bootstrapping methods to determine standard errors, allowing simultaneous estimates of all effects and avoiding the assumption of a standard normal distribution when calculating p-values. We used 1000 resamples of the data, and used bias corrected and accelerated bootstrap confidence intervals (95%) to adjust for any bias in the sampling distribution. As can be seen in Table 2, the main effect for early cumulative risk was significant on step one, b = 3.487, β = .323, p = .0001; and the interaction with 5-HTTLPR genotype was significant on step two, b = 2.901, β = .167, p < .005.

Table 2.

Bootstrapping Regression Models with Robust Standard Errors Explicating the Impact of Cumulative Socio-economic Status Risk, 5-HTTLPR, and their Interaction on Methylation of the “Main-Effect” Depression pathway, controlling for Age and Gender.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Unstandardized b [95% CI] | Unstandardized b [95% CI] | Unstandardized b [95% CI] | |

| Main Effect | |||

| Cumulative SES risk (Ages 10 to 13) | 3.487** | 2.364** [.926, 3.802] | 2.429** [.950, 3.907] |

| Cumulative SES risk Squared | −.190 [−1.366, .986] | ||

| 5-HTTLPR (1 = ss, sl) | −.265 [−2.321, 1.792] | −.287 [−2.315, 1.740] | .260 [−2.455, 2.976] |

| Two-way Interaction | |||

| Cumulative SES risk × 5-HTTLPR | 2.901** [.855, 4.948] | 2.799** [.736, 4.862] | |

| Cumulative SES risk squared × 5-HTTLPR | −.559 [−2.429, 1.311] | ||

| Control Variables | |||

| Age | .930 [−.754, 2.614] | .911 [−.743, 2.565] | .914 [−.736, 2.546] |

| Gender | −1.508 [−3.618, .601] | −1.364 [−3.437, .709] | −1.350 [−3.427, .726] |

| Constant | 25.396** [23.842, 26.950] | 25.329** [23.762, 26.896] | 25.514** [23.618, 27.411] |

| R-Square | .118 | .135 | .138 |

Note. Bootstrap = 1000 replications; Average Risk index (W1-W3) is standardized by z-transformation, and age is measured by men-centering; CI = confidence interval; W1 = Wave 1; W2 = Wave 2; W3 = Wave3.

p ≤ .01;

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .10 (two-tailed test).

N = 385.

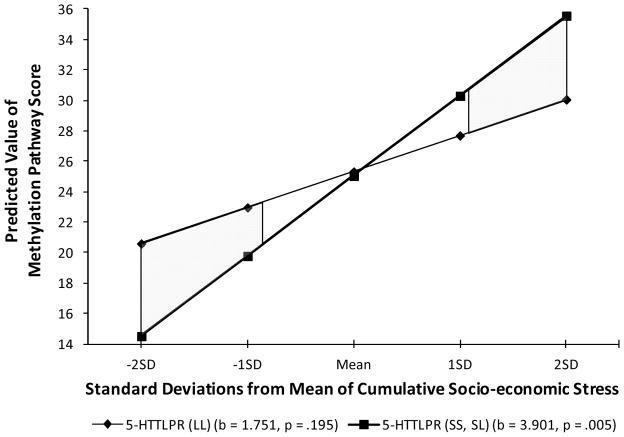

To explicate the significant interaction and identify regions of significant difference, we first examined simple slopes. As can be seen in Figure 3, the simple slopes conformed to expectations of greater impact of cumulative SES risk among s allele carriers. The significant interaction effect is the result of a steeper, and significant slope for the association of early cumulative SES risk with the depression “main effect” index among those carrying the s allele (b = 3.901, p = .005), but a less steep and non-significant slope among those with only “l” or “vl” alleles (b = 1.751, NS). In addition, there is a crossover effect of the sort predicted by the susceptibility model. That is, s allele carriers experiencing low levels of cumulative SES risk demonstrated less methylation in the “depressogenic” direction than did those carrying only l and vl alleles. Conversely, s allele carriers experiencing higher levels of early cumulative SES risk demonstrated greater methylation in the depressogenic direction than did those carrying only l and vl alleles. Although the simple slopes are in the same direction for s allele carriers and those carrying only l and vl alleles, there is a significantly greater effect of early cumulative SES risk on the overall “main effect” index among s allele carriers.

Figure 3.

The moderating role of variation at the 5-HTTLPR on the association of early cumulative SES risk with the “main effect” methylation index for the depression pathway (50 CpG sites). Higher scores reflect methylation in the direction mediating the effect of SES on future depressive symptoms. Shaded regions reflect significant differences between the regression lines.

In keeping with evolving methodological guidelines, we further compared vulnerability vs. susceptibility models by highlighting regions of significant difference between the two simple regression lines. These are shown as shaded areas between the simple regression lines in Figure 3, and indicate substantial and symmetrical regions of significant difference at both ends of the early cumulative SES risk continuum. We also computed the Proportion of Interaction (PoI) index to compare the proportion of significantly different effects uniquely attributable to effects at both ends of the early cumulative SES risk continuum. The resulting ratio of smaller region to total shaded region was .45, close to the maximum potential value of .5, suggesting a relatively robust finding in favor of the susceptibility model. Finally, as can be seen in Table 2 (step 3), we repeated the regression analyses introducing non-linear effects and found these effects to be non-significant.1,2,3 Specifically, the quadratic term formed by early cumulative SES risk squared and the interaction of the quadratic term with 5-HTTLPR genotype were both non-significant. Despite this, the previously significant interaction effect of genotype with early cumulative SES risk remained significant after introduction of the non-linear terms, suggesting that it is not attributable to underlying curvilinear effects.

We next examined the impact of 5-HTTLPR genotype on the association of early cumulative SES risk and methylation on a locus-by-locus basis across the main-effect index. For 42 out of 50 CpG sites, the absolute value of the correlation of cumulative risk with methylation was greater for s allele carriers than for those carrying only l or vl alleles. Accordingly, the interaction effect reflected relatively greater impact of cumulative SES risk on DNA methylation among s allele carriers at the aggregate level as well as at the level of individual CpG sites. .

A second stage in our examination of whether the effect of early cumulative SES risk on depression pathway methylation was moderated by 5-HTTLPR was to test whether the pattern reported above could be replicated using all CpG sites on depression associated genes for which methylation level was significantly associated with the interaction of early cumulative SES risk and 5-HTTLPR. A series of regression analyses was used to examine the 4,661 CpG sites on depression-related genes, introducing the interaction of genotype and early cumulative risk on a second step, after first entering genotype, early cumulative SES risk, age, and gender. The 300 CpG sites for which a nominally significant (p < .01) interaction effect emerged, controlling for main effects, were used to form the “interaction index” examined next.

The “interaction index” was comprised of (n=300) CpG sites scored as “1” for CpG sites that were positively associated with cumulative stress for s allele carriers and for which the individual was above the mean of the distribution and otherwise “0.” Conversely, CpG sites that were negatively associated with cumulative stress for s allele carriers were scored “1” when the methylation value for the individual was below the mean, and scored “0” otherwise. Higher index scores were obtained by individuals who most closely conformed to the high risk, s allele methylation prototype.

To examine the shape of the interaction effect across depression related genes, we regressed the depression “interaction index” score for each participant on early cumulative SES risk and the 5-HTTLPR genotype, as well as the control variables of age and gender on step one. We then examined the moderating effect of variation at the 5-HTTLPR by entering the interaction of cumulative risk and genotype on the second step of the regression. As before, we used bootstrapping methods to allow simultaneous estimates of all effects and to avoid reliance on assumptions of a standard normal distribution when calculating p-values. We used 1000 resamples of the data, and used bias corrected and accelerated bootstrap confidence intervals (95%) to adjust for any bias in the sampling distribution. As can be seen in Table 3, the main effect for early cumulative SES risk was significant on step one, b = 7.479, β = .103, p = .046; and the interaction with presence of an s allele at the 5-HTTLPR genotype was also significant on step two, b = 39.003, β = .333, p < .0001.

Table 3.

Bootstrapping Regression Models with Robust Standard Error Explicating the Impact of Cumulative Socio-economic Status Risk, 5-HTTLPR, and their Interaction on Methylation of the “Interaction-Effect” Depression Pathway, controlling for Age and Gender

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Unstandardized b [95% CI] | Unstandardized b [95% CI] | Unstandardized b [95% CI] | |

| Main Effect | |||

| Cumulative SES risk (Ages 10 to 13) | 7.479* [.135, 14.822] | −7.615 [−16.849, 1.618] | −9.004† [−18.619, .611] |

| Cumulative SES risk Squared | 3.975 [−4.028, 11.978] | ||

| 5-HTTLPR (1 = ss, sl) | −.612 [−15.747, 14.524] | −.919 [−15.456, 13.618] | 6.239 [−13.041, 25.520] |

| Two-way Interaction | |||

| Cumulative SES risk × 5-HTTLPR | 39.003** [25.074, 52.931] | 40.221** [26.044, 54.397] | |

| Cumulative SES risk squared ×5-HTTLPR | −7.218 [−21.282, 6.846] | ||

| Control Variables | |||

| Age | 2.214 [−9.495, 13.924] | 1.959 [−9.257, 13.174] | 2.374 [−8.952, 13.701] |

| Gender | 11.256 [−3.739, 26.251] | 13.193† [−1.108, 27.493] | 13.729† [−.609, 28.068] |

| Constant | 136.785** [125.964, 147.607] | 135.880** [125.278, 146.482] | 131.658** [118.442, 144.873] |

| R-Square | .017 | .084 | .088 |

Note. Bootstrap = 1000 replications; Average Risk index (W1-W3) is standardized by z-transformation, and age is measured by mean-centering; CI = confident interval; W1 = Wave 1; W2 = Wave 2; W3 = Wave3.

p ≤ .01;

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .10 (two-tailed test).

N = 385.

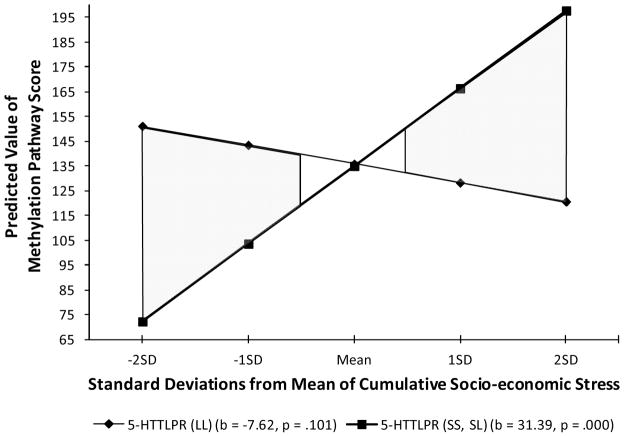

Figure 4 explicates the interaction effect. As can be seen, s allele carriers showed, on average, a greater response to early cumulative SES risk. The significant interaction effect is the result of a steeper, and significant slope for the association of early cumulative SES risk with the depression “interaction index” among those carrying the s allele (b = 31.39 , p = 0001.), but a less steep and non-significant slope among those with only “l” or “vl” alleles (b = 7.62, NS). In addition, there was a crossover pattern (i.e., the pattern indicative of “susceptibility” effects). To further clarify the comparison of vulnerability vs. susceptibility models we highlighted regions of significance, showing substantial regions of significant effects at both ends of the early, cumulative risk continuum. We also computed the Proportion of Interaction (PoI) index. The resulting value of .49 suggests a robust finding in favor of susceptibility. Finally, we repeated the analyses including potential non-linear effects as before and again found them to be non-significant. Specifically, there was no significant effect of a quadratic term for early cumulative SES risk, nor did the quadratic term interact significantly with the 5-HTTLPR genotype.

Figure 4.

The moderating role of variation at the 5-HTTLPR on the association of early cumulative SES risk with the “interaction-related” methylation index for the depression pathway (300 CpG sites). Higher scores reflect methylation in the direction of a positive association for s allele carriers. Shaded regions reflect significant differences between the regression lines.

It should be noted that, unlike the analyses with the “main effect” index, the “interaction index” is scored in a manner that ensures a more positive association between the index score and early cumulative SES risk for s allele carriers. However, it should also be noted that this need not translate into an advantage in favor of the susceptibility model relative to the vulnerability model, nor does it necessarily produce greater absolute correlations for s allele carriers. Acordingly, examination of the relative strength of associations at the level of individual CpG sites produced an additional useful consistency check. Across the 300 CpG sites on the interaction pathway, 277 CpG sites demonstrated a significantly greater absolute correlation for s allele carriers than for youth with only l or vl alleles. Accordingly, the results replicate the pattern observed in the main effect pathway analysis, suggesting that genotype at the 5-HTTLPR is consequential for shape of epigenetic impact of early cumulative SES risk on the depression pathway, that the presence of an s allele confers greater impact of early cumulative SES risk on epigenetic change, and that the susceptibility model better captures the pattern of moderation than does the vulnerability model, with effects present across a majority of CpG sites on the pathway.

To complete our examination of 5-HTTLPR effects on depression pathway methylation we also examined the effect of carrying an s allele on the relative impact of early, cumulative SES risk on methylation on each of the 4,661 CpG sites on the depression pathway (i.e., not just those that were significantly associated with main or interaction effects). Specifically, we examined whether the pattern of differences in absolute correlation values across the entire pathway was consistent with a greater impact of early cumulative risk among carriers of the s allele than for those who did not have an s allele. Of 4,661 CpG sites examined, 3,528 demonstrated greater absolute correlations between early cumulative risk and methylation for s allele carriers, representing a significant deviation from the null expectation that there would be equal numbers of CpG sites with greater and lesser impact for each genotype.

Finally, to investigate whether there was a pattern of increased impact among s allele carriers on a genome-wide basis, and whether the effect of carrying the s allele was consistent with the expectation of enhanced impact on developmentally important processes among s allele carriers, we conducted genomewide analyses to identify all CpG sites associated with the interaction effect at the p<.01 level. Using a series of regressions to examine each loci across the filtered data set, and using the same analytic approach as for the previous analyses, with main effects entered prior to the centered interaction effect, we identified 25,601 CpG sites out of the set of 426,670 total filtered CpG sites that were significantly (nominally) associated at the p<.01 level with the interaction of early cumulative SES risk and genotype controlling main effects, age and sex.

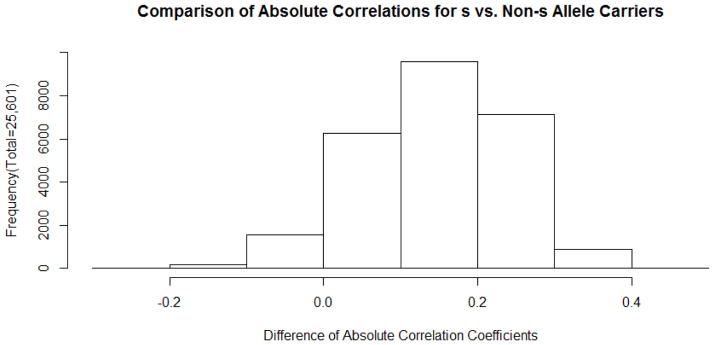

Among the set of 25,601 significantly associated CpG sites, we examined whether the magnitude of association was greater for s allele carriers than for those carrying only l or vl alleles. For each CpG site we examined the difference between s allele carriers vs. those carrying only l or “vl” alleles in the absolute value of the correlation of cumulative risk with methylation. In 23,864 CpG sites the s allele carriers demonstrated greater absolute impact of cumulative risk on degree of methylation than their l or “vl” allele counterparts, deviating sharply from expectations under the null hypothesis. Conversely, only 1,737 CpG sites showed the reverse pattern with s allele carriers demonstrating a smaller association of early cumulative SES risk with degree of methylation. The strong shift toward greater impact among s allele carriers genomewide can be seen in the histogram in Figure 5. The height of the bars in the histogram indicates the number of CpG sites for which the difference in magnitude of correlations is within each given range. As can be seen, the modal difference is between .1 and .2, and the median value is .149.

Figure 5.

Histogram of differences in correlation magnitude for s allele carriers versus others across the 25,601 CpG sites demonstrating a significant interaction of variation at the 5-HTTLPR with cumulative SES risk. Median value is .149, indicating greater magnitude for s allele carriers.

The six-fold greater number of significant CpG sites associated with the interaction effect genomewide relative to chance suggested the potential value of further characterization of the effect within a gene pathway analytic framework. To examine significantly enriched pathways using controls for multiple comparisons, we examined the significantly associated CpG sites in GoMiner™ using default settings (i.e., 0.05 settings for reports and all gene ontology as the root category setting) and using the 25,601 CpG sites identified in the genomewide analyses as the “changed” gene set (Zeeberg, Feng, Wang, Wang, Fojo, Sunshine, et al., 2003).

The top 30 pathways are reported in Table 4, with nominal and false discovery rate (FDR) corrected values reported. As can be seen, there was a systematic patterning in the methylation data reflecting the influence of the interaction between genotype and early cumulative SES risk on a number of key developmental epigenetic pathways.

Table 4.

The Top 30 Most Differentially Regulated Gene Ontology Pathways for interaction effect of Early Cumulative Stress with 5-HTT

| Genes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO Category | Category Name | Total | Changed | Log10 P- Value | FDR |

| GO:0030154 | cell differentiation | 2825 | 1532 | −21.2044 | 0 |

| GO:0007399 | nervous system development | 1905 | 1070 | −20.5701 | 0 |

| GO:0048869 | cellular developmental process | 2894 | 1562 | −20.5269 | 0 |

| GO:0043005 | neuron projection | 603 | 384 | −18.3279 | 0 |

| GO:0032502 | developmental process multicellular organismal | 4935 | 2533 | −18.2893 | 0 |

| GO:0007275 | development | 4513 | 2329 | −17.9512 | 0 |

| GO:0009653 | anatomical structure morphogenesis | 2302 | 1253 | −17.7078 | 0 |

| GO:0048731 | system development | 3782 | 1975 | −17.5666 | 0 |

| GO:0023052 | Signaling | 4769 | 2443 | −16.8903 | 0 |

| GO:0048856 | anatomical structure development | 4238 | 2186 | −16.4639 | 0 |

| GO:0048468 | cell development | 1586 | 888 | −16.4326 | 0 |

| GO:0022008 | Neurogenesis | 1226 | 703 | −16.0295 | 0 |

| GO:0048699 | generation of neurons | 1153 | 665 | −15.9134 | 0 |

| GO:0042995 | cell projection | 1124 | 650 | −15.8964 | 0 |

| GO:0030182 | neuron differentiation | 1082 | 626 | −15.3683 | 0 |

| GO:0044459 | plasma membrane part | 2338 | 1252 | −14.6631 | 0 |

| GO:0045202 | Synapse | 494 | 312 | −14.27 | 0 |

| GO:0023060 | signal transmission | 3620 | 1871 | −14.1181 | 0 |

| GO:0023046 | signaling process | 3624 | 1872 | −14.0017 | 0 |

| GO:0005515 | protein binding | 8633 | 4224 | −13.9081 | 0 |

| GO:0032989 | cellular component morphogenesis | 965 | 559 | −13.8783 | 0 |

| GO:0000902 | cell morphogenesis | 882 | 515 | −13.6359 | 0 |

| GO:0007154 | cell communication regulation of multicellular | 2062 | 1106 | −13.115 | 0 |

| GO:0051239 | organismal process cell morphogenesis involved in | 1615 | 884 | −13.0582 | 0 |

| GO:0000904 | differentiation | 747 | 442 | −12.9906 | 0 |

| GO:0048666 | neuron development | 857 | 499 | −12.9368 | 0 |

| GO:0009887 | organ morphogenesis | 995 | 568 | −12.4929 | 0 |

| GO:0030030 | cell projection organization | 931 | 533 | −12.0308 | 0 |

| GO:0044463 | cell projection part | 540 | 329 | −11.9901 | 0 |

| GO:0031175 | neuron projection development | 736 | 431 | −11.7343 | 0 |

Note. FDR= false discovery rate. Total of 518 Differentially Regulated Gene Ontology

Pathways based on FDR<0.01.

Among the top 10 pathways showing differential impact as a function of the 5-HTTLPR were nervous system development, cellular developmental process, neuron projection, developmental process, multicellular organismal development, anatomical structure morphogenesis, and system development. Accordingly, the GoMiner™ analyses suggest both coherent patterning of methylation effects associated with the 5-HTTLPR by early cumulative SES risk interaction effect as well as a concentrated impact on development.

Discussion

The goal of the current investigation was to examine several interrelated questions regarding the potential impact of genetic variation at 5-HTTLPR on long-term vulnerability to depression and neurodevelopmental outcomes in response to early cumulative SES risk. Because the long-term effects of early cumulative SES risk are well known and the assessment of such risk is based on relatively objective indicators, this investigation provides a useful context for exploration of claims regarding the magnitude, shape, and generality of the impact of genetic variability at the 5-HTTLPR on epigenetic change. We focused on epigenetic change in depression related genes as an outcome of interest because this contributes directly to the continuing discussion of the nature, consistency, and mechanisms of 5-HTTLPR effects. The findings were consistent with the expectation of enhanced impact of early, cumulative SES risk among carriers of the s allele. The effect was examined in several ways and consistent patterns were observed. Whether examining the main effect pathway (i.e. the 50 CpG sites identified previously on the basis of significant main effects and association with young adult depression), or examining the interaction pathway (i.e., the 300 CpG sites that were significantly associated with the interaction effect across the depression pathway), the full set of all 4,661 CpG sites sampled from depression related genes, or all CpG sites across the genome associated with differential impact of early cumulative SES risk, there was evidence of increased impact of early, cumulative SES risk on methylation among s allele carriers relative to those with only l or vl alleles. Accordingly, the finding that the s allele of the 5-HTTLPR is associated with increased impact of early cumulative SES risk on methylation appears robust.

We also used the methylation data to construct indices to compare susceptibility and vulnerability models at the level of epigenetic change among depression associated genes. Consistent support was found for the susceptibility model relative to the vulnerability model. For both the main effect index and the interaction effect index, we found evidence of crossover effects.4 The effect of early cumulative risk on methylation was significant among s allele carriers but not among those who did not carry an s allele. In addition, for both indices, regions of significant difference were identified at both ends of the early cumulative SES risk continuum, the proportion of the interaction effect uniquely associated with susceptibility was substantial, and there was no evidence of confounding by non-linear effects. Accordingly, for the depression pathway indices, each of the four types of evidence currently recommended for comparison of vulnerability and susceptibility models supported the susceptibility perspective.

Using GoMiner™, we conducted gene pathway analyses using the information from the 25,601 probes that were nominally differentially methylated at the p<0.01 level due to the interaction of the 5-HTTLPR and early cumulative SES risk. A theme of the most significantly differentially methylated pathways was that neuronal and developmental pathways were differentially influenced by early cumulative SES risk depending on the presence of the s allele. As shown by the pattern of differences in absolute correlations, these differences once again reflected the stronger impact of early cumulative SES risk among s allele carriers. Overall, 518 gene pathways survived FDR correction for the interactive effect of 5-HTT and cumulative SES risk on genome-wide methylation, suggesting that the impact of the “s” allele on response to early cumulative risk may extend well beyond its effects on depression-related genes. However, caution is required in the interpretation of the GoMiner™ results, as the approach used in these analyses focuses on number of genes enriched relative to the genome as a whole, discarding potentially important information about degree of change and number or pattern of CpG sites affected. More importantly, the approach also assumes the independence of affected genes and pathways, an assumption that is likely violated in most cases for analyses of patterns of methylation. Thus, the GoMiner results may best be viewed as providing an indication of the relative likelihood of differentially affected gene pathways rather than providing an absolute p-value for individual pathways.

The current study was designed to detect small to medium effect sizes (e.g., r-square = .05). For an effect of this size, the current sample (N = 385) provides power > .90. In the current analyses, both the main effect of cumulative SES risk (β = .219) and its interaction with 5HTTLPR (β = .167) had medium to large effects in the prediction of the “main effect” index reported in Table 2. In addition, the effect size associated with the interaction of cumulative SES risk and with 5HTTLPR (β = .333) was large for the analysis reported in table 3 (i.e., the “interaction” index). Power calculations using Monte Carlo simulation procedures (Muthen and Muthen, 2002) indicated that we had power > .90 to detect these effects. Similarly, in the context of separately testing vulnerability and susceptibility components of the model in figures 3 and 4, power was estimated to be > .80. Conversely, consistent with the broader literature on genetic main effects, the main effect of variation at 5HTTLPR is quite small (β = −.013 and β = −.006), yielding a power estimate of .079 to detect the effect in the context of table 1 and .066 in table 2 for a sample of this size. Accordingly, the current sample would be underpowered to detect the main effect of genotype on indices of methylation, but appears to be adequately powered to detect the interaction effects of cumulative SES risk and genotype. At the same time, the current sample is substantially underpowered for genomewide examination of effects on individual CpG sites due to the need to correct for multiple comparisons, and this is one reason it is not attempted in the current manuscript. Recent reviews have questioned the role of 5-HTTLPR in the prediction of depression and other forms of psychopathology (Risch et al., 2009). In particular, it has been noted that there have been a number of non-replications of studies using complex phenotypes, like depression, as the outcome variable and complex stressors, such as “life stress” or “early adversity,” as the environmental variable. In the current report we focus on a simple and relatively objective childhood stressor, early cumulative SES risk, and a simple biological dependent variable, DNA methylation. Because the main effect of early cumulative SES risk on a range of outcomes is not in dispute, we are able to focus on whether variation in the 5-HTTLPR acts as a vulnerability or susceptibility factor in the context of a well-known childhood stressor. In addition, a focus on DNA methylation has several advantages in the context of testing the susceptibility hypothesis. Most notably, because it does not involve self-report, it is immune to concerns regarding reactivity and self-report biases. Accordingly, the current report's focus on epigenetic change provides an alternative to self-reported symptoms and behavior in tests of the effect of the s allele’ at the 5-HTTLPR and whether it acts as a susceptibility or vulnerability factor. Second, because methylation changes may be functional, observed differences also have the potential to illuminate potential etiological pathways. Third, because epigenetic change may influence activity in a number of genetic pathways, it provides a context for exploration of broader patterns of epigenetic influence.

The pattern of results is clear in supporting the role of 5-HTTLPR as a susceptibility factor in response to variation in exposure to early cumulative SES risk. In a relatively impoverished sample with high representation of working poor we find that presence of the 5-HTTLPR s allele is associated with significantly different and greater impact of early cumulative SES risk on gene methylation. It is worth noting that the sampling strategy conforms to calls for strategies that increase the potential power to detect GxE effects by focusing on samples with optimal distribution of exposure variables (Caspi, et al., 2010). However, it should be noted as well that the CpG sites examined are a small sub-sample of all potential methylation sites, creating potential for future tests with more comprehensive coverage to lead to different results or to identify subsets of CpG sites that respond differently.

Several limitations of the current investigation are important to note. First, these findings are based on a relatively small sample size with limited statistical power, particularly with regard to determination of genome-wide levels of significance. We observed differential association between cumulative SES risk and methylation for carriers of s and l alleles at multiple CpG sites, but none of the associations at individual CpG sites reached the level of statistical significance required to confirm the association as genomewide significant. Consequently, our conclusions reflect inferences for sets of CpG sites rather than individual CpG sites. A focus on sets of CpG sites across functionally related genes, as illustrated in the current report, provides a potentially useful framework for future research by behavioral researchers working with modest sample sizes. Finally, because DNA methylation patterns exert different effects on gene transcription depending on where they are located, it cannot be assumed that all significant methylation effects had similar associations with gene transcription of the affected gene. Accordingly, the connection between observed changes in pathway methylation and gene activity remains to be confirmed for most of the genes examined (see Plume et al., 2012).

There are also several challenges to the identification of mechanisms of change using the current data. First, there is the potential problem of tissue-specificity of epigenetic control (e.g., Davies, Volta, Podsley, Lumon, Dixon, Lovestone , et al., 2012). In particular, we cannot assume that methylation patterns observed in lymphocytes are similar in all respects to the patterns likely to be observed in other tissues of particular interest, such as specific types of brain tissue. Clearly, some methylation patterns are likely to be tissue specific because of the important role of DNA methylation in the specialization of tissue type. However, Rollins, Martin, Morgan, and Vawter (2010) have shown that peripheral measures of gene expression predicts central expression for genes expressed similarly in each cell type. Shumay, Logan, and Volkow (2012) found that methylation of MAOA in white blood cells predicted brain MAOA levels, suggesting that peripheral measures of methylation can predict brain endophenotype. Likewise, Davies et al. (2012) found sufficient correspondence in intra-individual variation across brain and blood to indicate the utility of peripheral tissues in epidemiological studies. Accordingly, for CpG sites on sets of genes that are similarly expressed, patterns of methylation may be more similar than different across different tissue types. Nonetheless, the degree to which, and the circumstances under which, methylation patterns observed using lymphocytes reflects methylation in particular regions of interest in the brain will require additional direct investigation.

These limitations notwithstanding, the current results suggest that methylation is an excellent vehicle for studying potential long-term developmental effects of early stressors. It appears possible that some long-term effects of early stressors may be mediated by their impact on changes in methylation patterns across the genome that result in shifts in developmental processes or that directly influence later behavioral and health outcomes. The current study supports continued exploration of epigenetic change as a mechanism accounting for GxE effects on development and long-term effects. Better understanding the role of epigenetic change in functional genetic pathways will require additional investigation at multiple levels of analysis with a particular focus on the time course of methylation change, the extent to which particular patterns are fixed or malleable, and investigation of the time frame over which change may be reversible. It will be important to identify appropriate ages for detection of particular outcomes. For example, whereas detection of associations between methylation and some outcomes, like depression, might be readily observed in young adulthood, other outcomes may not be readily observed until later in life. Likewise, it will be important to better specify sets of genes or gene pathways most directly related to behavioral phenotypes and outcomes of interest. In brief, although epigenetic change appears to be a promising mechanism for future exploration, it will require better incorporation into a broad developmental psychopathology framework to reach its full potential.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Award Number 5R01HD030588-16A1 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and Award Number 1P30DA027827 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

It is possible that non-linearity could be introduced if a more extreme range of values were examined. Indeed it seems likely that non-linearity will always be critically dependent on the range of environments examined as well as the scoring of the dependent variable. In the current sample, early cumulative SES risk was pronounced and resulted in a roughly equal number of youth who were profoundly and not profoundly affected by SES stress.

It is also worth noting that interactions reflecting vulnerability (but not susceptibility) effects can be eliminated or substantially reduced by transforming the dependent variable. Accordingly, interaction tests using transformed data may provide an alternative way of controlling for cryptic non-linearity.

We also ran the analyses for the “main effect” index including sex as a predictor and allowing it to interact with all other variables. In that analysis there was a significant three-way interaction of Sex x Cumulative SES risk x 5HTT, which indicated that effects were in the same direction for males and females, but stronger for males. However, this pattern was not replicated in the subsequent analysis using the “interaction-effect” index; for that analyses there were no significant interactions with sex. Nor was the stronger effect for males observed in the genomewide examination. In that analysis, the moderating effect of the s-allele was more pronounced for females than males, although once again it was in the same direction.

It is of potential theoretical interest to compare models of absolute vs. relative deprivation to examine whether susceptibility effects for cumulative SES risk depend on having a substantial proportion of the population under the poverty level, as was the case in the current sample, or whether susceptibility effects emerge as well due to variation in circumstances within populations with higher average SES and fewer individuals below the poverty level.

References

- Battaglia M, Ogliari A, Zanoni A, Citterio A, Pozzoli U, Giorda R, Marino C. Influence of the serotonin transporter promoter gene and shyness on children's cerebral responses to facial expressions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:85–94. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach SRH, Brody GH, Lei MK, Kim S, Cui J, Philibert RA. Effects of cumulative early socio-economic stress on epigenetic reprogramming and depression among African American young adults. University of Georgia; 2013. Unpublished Manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Beevers CG, Wells TT, Ellis AJ, McGeary JE. Association of the serotonin transporter gene promoter region (5-HTTLPR) polymorphism with biased attention for emotional stimuli. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118:670–681. doi: 10.1037/a0016198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Pluess M. Beyond diathesis-stress: Differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135(6):885–908. doi: 10.1037/a0017376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce WT, Ellis BJ. Biological sensitivity to context: I. An evolutionary-developmental theory of the origins and functions of stress reactivity. Development and Psychopathology. 2005;17(2):271–301. doi: 10.1017/S0954579405050145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley SL, Dodelzon K, Sandhu HK, Philibert RA. Relationship of serotonin transporter gene polymorphisms and haplotypes to mRNA transcription. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 2005;136:58–61. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, Willaims DR, Pamuk E. Socioeconomic disparities in health in the United States: What the patterns tell us. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;1000:S186–S196. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.166082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Beach SRH, Chen YF, Obasi E, Philibert RA, Kogan SM, Simons RL. Perceived discrimination, serotonin transporter linked polymorphic region status, and the development of conduct problems. Development and Psychopathology. 2011;23:617–627. doi: 10.1017/S0954579411000046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Murry VM, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Molgaard V, McNair LD, Neubaum-Carlan E. The Strong African American Families program: Translating research into prevention programming. Child Development. 2004;75:900–917. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Johnson SL, Joormann J. Serotonergic function, two-mode models of self-regulation, and vulnerability to depression: What depression has in common with impulsive aggression. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;134:912–943. doi: 10.1037/a0013740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Johnson SL, Joormann J, LeMoult J, Cuccaro ML. Childhood adversity interacts separately with 5-HTTLPR and BDNF to predict lifetime depression diagnosis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011;132:89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Hariri AR, Holmes A, Uher R, Moffitt TE. Genetic sensitivity to the environment: The case of the serotonin transporter gene and its implications for studying complex diseases and traits. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167:509–527. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09101452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, Taylor A, Craig IW, Harrington H, Poulton R. Influence of life stress on depression: moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science. 2003;301:386–389. doi: 10.1126/science.1083968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen E, Miller GE, Walker HA, Arevalo JM, Sung CY, Cole SW. Genome-wide transcriptional profiling linked to social class in asthma. Thorax. 2008;64:38–43. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.095091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole SW. Social regulation of human gene expresssion. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2011;18(3):132–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01623.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Wallace LE, Sun Y, Simons RL, McLoyd VC, Brody GH. Economic pressure in African American families: A replication and extension of the family stress model. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:179–193. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.38.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crişan LG, Pană S, Vulturar R, Heilman RM, Szekely R, Drugă B, Miu AC. Genetic contributions of the serotonin transporter to social learning of fear and economic decision making. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2009;4:399–408. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsp019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champagne DL, Bagot RC, van Hasselt F, Ramakers G, Meaney MJ, de Kloet ER, …Krugers H. Maternal care and hippocampal plasticity: Evidence for experience-dependent structural plasticity, altered synaptic functioning, and differential responsiveness to glucocorticoids and stress. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;4, 28(23):6037–6045. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0526-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies MN, Volta M, Podsley R, Lumon K, Dixon A, Lovestone S, Mill J. Functional annotation of the human brain methylome identifies tissue specific epigenetic variation across brain and blood. Genome Biology. 2012;13:R43. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-6-r43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dressler WW, Oths KS, Gravlee CC. Race and ethnicity in public health research: Models to explain health disparities. Annual Review of Anthropology. 2005;34:231–252. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anthro.34.081804.120505. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt F, Lewin J, Cortese R, Rakyan VK, Attwood J, Burger M, Beck S. DNA methylation profiling of human chromosomes 6, 20 and 22. Nature Genetics. 2006;38(12):1378–85. doi: 10.1038/ng1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW. A multimethodological analysis of cumulative risk and allostatic load among rural children. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:924–933. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.5.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, Chen E, Miller G, Seeman T. How Poverty Gets Under the Skin: A Life Course Perspective. In: Maholmes V, King RB, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Poverty and Child Development. Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fraga MF, Ballestar E, Paz MF, Ropero S, Setien F, Ballestar ML, Esteller M. Epigenetic differences arise during the lifetime of monozygotic twins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2005;102(30):10604–10609. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500398102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariri AR, Drabant EM, Munoz KE, Kolachana BS, Mattay VS, Egan MF, Weinberger DR. A susceptibility gene for affective disorders and the response of the human amygdala. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:146–152. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.2.146. Retrieved from http://archpsyc.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/abstract/62/2/146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariri AR, Holmes A. Genetics of emotional regulation: The role of the serotonin transporter in neural function. Trends in Cognitive Science. 2006;10:182–191. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz A, Braus DF, Smolka MN, Wrase J, Puls I, Hermann D, Büchel C. Amygdala-prefrontal coupling depends on a genetic variation of the serotonin transporter. Nature Neuroscience. 2005;8:20–21. doi: 10.1038/nn1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isenberg N, Silbersweig D, Engelien A, Emmerich S, Malavade K, Beattie B, Stern E. Linguistic threat activates the human amygdala. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1999;19:10456–10459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10456. Retrieved from http://www.pnas.org/content/96/18/10456.abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Research. 2000;28(1):27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Brody GH. Longitudinal pathways to psychological adjustment among Black youth living in single-parent households. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:305–313. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinnally EL, Capitanio JP, Leibel R, Deng L, LeDuc C, Haghighi F, Mann JJ. Epigenetic regulation of serotonin transporter expression and behavior in infant rhesus macaques. Genes, Brain, and Behavior. 2010;9(6):575–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2010.00588.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]