Abstract

Attachment of ubiquitin (Ub) and ubiquitin-like proteins (Ubls) to cellular proteins regulates numerous cellular processes including transcription, the cell cycle, stress responses, DNA repair, apoptosis, immune responses, and autophagy, to name a few. The mechanistically parallel but functionally distinct conjugation pathways typically require the concerted activities of three types of protein: E1 Ubl-activating enzymes, E2 Ubl carrier proteins, and E3 Ubl ligases. E1 enzymes initiate pathway specificity for each cascade by recognizing and activating cognate Ubls, followed by catalyzing Ubl transfer to cognate E2 protein(s). Under certain circumstances, the E2 Ubl complex can direct ligation to the target protein, but most often requires the cooperative activity of E3 ligases. Reviewed here are recent structural and functional studies that improve our mechanistic understanding of E1-, E2-, and E3-mediated Ubl conjugation.

Keywords: ubiquitin, ubiquitin-like protein, E1, E2, E3, ligase

INTRODUCTION

Posttranslational modification of target protein substrates by ubiquitin-like proteins (Ubls) affects nearly every aspect of cellular regulation. Depending on the ubiquitin (Ub) linkage, polyUb chains can target proteins for degradation via the 26S proteasome or can act as scaffolds for protein complex formation. In contrast, conjugation with a single Ub (mono) can regulate protein activity or localization. Both mono and chain conjugates of the small ubiquitin-like modifier protein (SUMO) are associated with regulation of protein activity, complex formation, nuclear or cytoplasmic protein localization, and transcription. The Ubl Nedd8 is primarily conjugated to cullin proteins to activate them for Ub conjugation, and the Ubls interferon-stimulated gene 15 (ISG15) and FAT10 play roles in the innate immune response. Other notable Ubl proteins are Atg8 and Atg12, which function in autophagy.

Ubls are conjugated to target substrates via the activities of three proteins: the E1 activating enzyme, E2 Ubl carrier proteins (Ubcs), and E3 Ubl ligases (Figure 1a). E1 catalyzes adenylation of the Ubl C-terminal glycine; followed by nucleophilic attack of the resulting Ubl-adenylate by a conserved active-site cysteine residue on the E1, thereby forming an E1~Ubl thioester.1 A second Ubl adenylation completes formation of the E1 ternary complex. The E1 ternary complex catalyzes thioester transfer of the Ubl from the E1 cysteine to a conserved active-site cysteine on the E2. E3 commonly binds the E2~Ubl and a target substrate to facilitate bond formation, although in some cases the E2~Ubl can direct conjugation. Conjugation to target proteins occurs most often on lysine residues, but it can also occur on the N-terminus, cysteine residues, or serine residues. The energy currency of these pathways, originating from adenosine triphosphate (ATP), is the thioester bond, which maintains a stable high-energy complex (7) that requires protein members of these cascades to facilitate destabilization and conjugate formation. Structural and functional insights into mechanisms for any Ubl pathway bear relevance to other Ubl pathways because their constituents share highly conserved domain structures, functions, and mechanisms. Here we review recent publications that have significantly advanced our mechanistic understanding of the steps involved in Ubl conjugation.

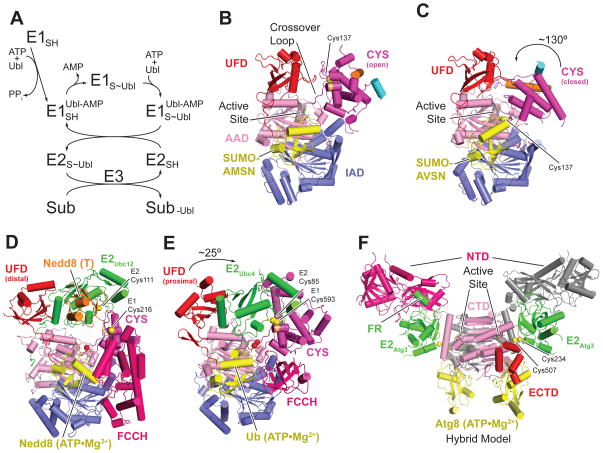

Figure 1.

E1 ubiquitin-like protein (Ubl) activating enzymes. (a) Ubl conjugation cascade. (b) Small ubiquitin-like modifier protein (SUMO)-adenylate bound to SUMO E1 in the open conformation (PDB ID: 3KYC). Two helices within the CYS domain have been colored orange and cyan to illustrate the CYS domain movement relative to panel c. (c) SUMO-adenylate-SUMO E1 tetrahedral intermediate complex in the closed conformation (PDB ID: 3KYD). Two helices within the CYS domain have been colored orange and cyan to illustrate the CYS domain movement relative to panel b. (d) Nedd8 E1 with E2Ubc12, Nedd8 adenylate and Nedd8 thioester bound (PDB ID: 2NVU). (e) E1–E2Ubc4 cross-linked complex with ubiquitin (Ub) bound to the adenylation site (PDB ID: 4II2). (f) Model of E1Atg7–E2Atg3 cross-linked structure with UblAtg8 bound, generated by alignment of molecules with the following PDB IDs: 3VH2, 3VH4, and 4GSL. E1 and E2 active-site cysteines are shown as yellow spheres, and magnesium ions are shown as red spheres. Molecular images generated with PyMOL (see Reference 92).

Abbreviations: AAD, active adenylation domain; CTD, C-terminal domain; CYS, second catalytic cysteine half-domain (with active-site cysteines); ECTD, extreme C-terminal domain; FCCH, first catalytic cysteine half-domain; IAD, inactive adenylation domain; NTD, N-terminal domain; PDB, Protein Data Bank; UFD, ubiquitin fold domain.

E1 UBIQUITIN-LIKE PROTEIN ACTIVATING ENZYMES

Members of the E1 activating enzyme family share considerable sequence, structural, and mechanistic homology, as reviewed recently (93, 104). For historic reasons, canonical members of the E1 family include Uba1 (involved in Ub activation), UbE1l (involved in ISG15 activation), the heterodimeric complex Uba2/SAE1 (involved in SUMO activation), and Uba3/NAE1 (involved in Nedd8 activation), among others. These enzymes share a conserved domain architecture consisting of two pseudosymmetric adenylation domains that form a composite active site responsible for ATP•Mg2+ and Ubl binding, a second catalytic cysteine (CYS) domain that harbors the active-site cysteine needed for E1~Ubl thioester bond formation, and the Ub fold domain (UFD) that interacts with E2 proteins (Figure 1) (40, 56, 60). Noncanonical E1 family members include the sulfur-fixing bacterial proteins MoeB and ThiF. These proteins are symmetric dimers that include two composite active sites formed by dimerization of the conserved adenylation domain but that lack the CYS and UFD (28, 54). Instead, these enzymes rely on protein cofactors to donate a sulfur atom to form a thiocarboxylate adduct. Since the E1 reviews from the Schulman (93) and Haas (104) groups were published, several advances have revealed insights into E1 activation.

Canonical E1 Activating Enzymes

Prior to 2010, a major question regarding E1 mechanism was as follows: How does the E1 catalytic cysteine attack the adenylated C-terminal Ubl residue given that its position is ~30 Å from the adenylation site in previously reported E1 structures (Figure 1b)? This issue was resolved in part by utilizing synthetic adenylate analogs linked to SUMO and Ub to create structural analogs of the Ub/Ubl-adenylate. These adducts inhibit corresponding E1s, and the installation of an electrophilic trap at a position analogous to the carbonyl carbon of the C-terminal glycine successfully captured a cross-linked thioether E1 adduct that mimicks the tetrahedral intermediate during thioester bond formation (62). Subsequent structural studies using SUMO E1 with SUMO adenylate analogs revealed a new closed conformation wherein the E1 CYS domain rotates 130°, transiting the catalytic cysteine to a position proximal to the SUMO C-terminal adenylate analog that remains coordinated within a remodeled adenylate active site (Figure 1c) (70).

Several changes to structural motifs and subdomains conserved in canonical E1s accompany movement of the CYS domain. Approximately half of the adenylation active site comprises key residues that alter conformations or are entirely replaced by CYS domain residues that are required for thioester bond formation. In addition, the crossover loop that passes above and contacts the Ubl C-terminus, which contributes to Ubl specificity, is shifted by 125°. A number of secondary structural elements present in the open conformation, including the helix that contains the E1 catalytic cysteine, become disordered or adopt new structures in the closed conformation. Finally, residues in the E1 CYS domain that cover the active-site cysteine become disordered, uncovering the cysteine to access the C-terminal adenylate.

In one study, Olsen et al. (70) showed that no residues capable of general acid-base chemistry are observed proximal to the E1 catalytic cysteine, however the N-terminal end of helix 2 is positioned below the adenylate linkage and may stabilize the oxyanion transition state intermediate via the N-terminal dipole. The authors further describe how these coordinated domain movements and disassembly of the adenylation active site may drive the reaction forward. This new E1 conformation explains data for the mechanism-based inhibitor of the Nedd8 E1, MLN4924, one of the few active drug leads for targeting Ub or Ubl pathways (31). The E1 binds the nucleotide analog MLN4924 and catalyzes the formation of a Nedd8–MLN4924 adenylate mimetic, which similar to the Nedd8-adenylate intermediate, binds the E1 with an impressive affinity but prevents further turnover. Surprisingly, the Nedd8–MLN4924 adduct is formed when a nucleophilic center on MLN4924 attacks the E1~Nedd8 thioester linkage, presumably by adopting a closed conformation (8, 70).

A second major question in the field of E1 research pertains to the following: How do the E1 and E2 active-site cysteine residues come together to facilitate E1–E2 thioester transfer, given the ~23 Å gap observed in the doubly loaded Nedd8 E1 with bound E2Ubc12 (Figure 1d) (40). Insights into conformational changes and surfaces required for thioester transfer come from the structure of an E1–E2Ubc4/Ub/ATP•Mg2+ complex generated by targeted disulfide bond formation between the E1 and E2 cysteine residues (71). The viability and pertinence of a disulfide cross-linking strategy is suggested by the observation that under oxidative stress, the Uba2 subunit of SUMO E1 becomes cross-linked to E2Ubc9 via a disulfide bond between the catalytic cysteine residues (6). The structure (Figure 1e) shows the E2 coordinated by the UFD via the N-terminal face of the E2 (helix A and β1-β2 loop) and by the CYS domain via the surface surrounding the E2 active-site cysteine. A ~25° rotation of the UFD brings the E2 from a previously observed distal position (40) to a proximal position in the cross-linked structure. Residues that cover the E1 cysteine are again displaced, this time to accommodate incoming E2 (Figure 1d,e). Mutational analyses in thioester transfer and cross-linking assays suggest the proximal conformations for E1 and E2 in this complex likely reflect conformations required for thioester transfer. While no thioester-linked Ubl is present in this structure, modeling and functional assays suggest that the E1 thioester-linked Ub is pushed forward upon E2 ingress and juxtaposition of the cysteines. The absence of residues capable of general acid-base chemistry within E1–E2–Ubl composite active site suggests rate enhancement and transition state stabilization may be accomplished by optimal positioning of the reacting species (71).

The vast array of structurally conserved Ubl, E1, and E2 paralogs raises a longstanding issue regarding mechanisms that ensure Ubl pathway specificity. Distinct E1s initiate each Ubl pathway via cognate Ubl recognition and activation. Recent reviews about E1 summarize known mechanisms for E1–Ubl specificity within Ub, Nedd8, SUMO, and ISG15 pathways (93, 104). The discovery of Uba6, an E1 with apparent dual specificity for Ub and FAT10, calls into question some of the basic tenets of specificity. Gavin and colleagues (34, 104) address this issue using kinetic analyses and show that Uba6 activates Ub with kinetic parameters similar to other E1s. However, Uba6 exhibits a 360-fold higher affinity for FAT10 than for Ub, and this difference likely allows Uba6 to become specific for FAT10 upon tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα)- and interferon gamma (IFNγ)-induced expression of FAT10 (34). It will be interesting to determine whether or not (a) activation of FAT10 or Ub by Uba6 influences E2, (b) E2s charged with FAT10 versus Ub influence E3 specificity, or (c) other E1s share the ability to activate noncognate Ubls under differing physiological conditions.

A second facet of specificity is achieved during E1-catalyzed E1–E2 thioester transfer. Tökgoz et al. (109) demonstrate that Uba1 binds to Ub-specific E2s with similar affinities and catalyzes thioester transfer with nearly identical kcat values, suggesting shared binding modes and similar transition states. N-terminal E2 acidic residues implicated in binding E1 are proximal to the E2/UFD surface as observed in the E1–E2 cross-linked crystal structure, but these residues do not directly contact the E1 UFD (71). In addition, mutation of these E2 residues diminishes E2 thioester formation even when the UFD is removed, suggesting an alternative function beyond UFD binding (109). UFD deletion reduces the catalytic efficiency of E1, suggesting that E2/UFD interactions play a role in catalysis. Tokgöz et al. (109) further suggest that the UFD functions not only as a positive interaction module but also as a specificity filter to exclude noncognate E2 pairings. Modeling of UFD/E2 pairings from available crystal structures is consistent with this interpretation, at least in the context of E2/UFD pairings for Ub, SUMO, and Nedd8 (71). What remains unclear is how the Ub E1 recognizes the dozen or more E2 proteins it charges, given the low sequence conservation observed for interfacial residues in the E1–E2 cross-linked complex (71).

The Autophagy-Related E1, Atg7

Atg7 is the E1 activating enzyme for two autophagy-related Ubl proteins, Atg8 and Atg12, that catalyzes the Ubl thioester transfer to their respective cognate E2s, Atg3 and Atg10 (35). Three studies (38, 69, 107) have demonstrated that, similar to the noncanonical E1s ThiF and MoaD (28, 54), Atg7 forms a homodimer through the conserved adenylate domain (Figure 1f). Atg7 lacks a CYS domain but instead utilizes a CYS loop. In the absence of E2 or Ubl, the CYS loop adopts a closed conformation (107) that is remodeled upon Ubl binding (38, 69) or when E1–E2 active sites are cross-linked (43). In contrast to other E1s, Atg7 has an extreme C-terminal domain (ECTD) that forms a four-helix pad beyond the adenylate domain and adjacent to the Ubl binding site (Figure 1f) (38, 69, 107). The ECTD domain buttresses the UblAtg8 and is important for transfer of the UblAtg8 thioester to E2Atg3 (38, 69). Atg7 has an additional unique feature in that it includes an ellipsoid N-terminal domain (NTD) (69, 107) that extends away from the adenylate homodimer and resembles a gliding bird (Figure 1f) (43, 69).

Additional structures demonstrate the importance of the “under-wing” surface for binding E2Atg3 and E2Atg10 (Figure 1f) (43, 118). Although both E2s bind similar regions of Atg7, they utilize unique insertions: E2Atg3 has a flexible region (FR) in a position where E2Atg10 has an extended β-strand and β-hairpin insertion. These insertions within the conserved E2 tertiary structure interact with the Atg7NTD in distinct ways using partially overlapping surfaces (Figure 1f) (43). This E1 mechanism is also unique in that thioester transfer proceeds in trans from the active-site cysteine of one protomer to the NTD-bound E2 of the other (43, 69, 107, 118).

The issue of specificity arises again in this system. Two groups (43, 118) have shown that under certain conditions, Atg7 catalyzes Ubl thioester transfer to noncognate E2. E2Atg3 exhibits higher affinity for Atg7 and can displace E2Atg10 owing to competing interactions for overlapping binding sites (38, 43, 107, 118). Structural features of the ECTD suggest that it contributes to Ubl specificity. In addition, the ~20 C-terminal residues, which are disordered in all available structures, are important for E2Atg3~Atg8 thioester formation and Atg8 conjugation because E2Atg3 binds the Atg8-interacting motif (AIM) on Atg8 (38, 69). E2Atg3 and Atg7 bind Atg8 via the AIM site, suggesting that this motif may not be available to establish E2 specificity when bound to E1 (38). Modeling Atg8 and the most apparently active conformation of the CYS loop onto the E2Atg3–Atg7 cross-linked structure suggests that the E2 may recognize unique CYS loop conformations in the context of the correct Ubl (43). It also remains possible that editing occurs in a post–thioester transfer step or that the pathways are not as rigid as previously thought (35).

E2 UBIQUITIN-LIKE PROTEIN CONJUGATING ENZYMES

Dynamics of the E2~Ubl Thioester and E2 Active Site Formation

Accumulating data suggest the E2 is not a passive cofactor for E3 ligases; rather, it is an active participant in the process of catalyzing isopeptide bond formation and imparts specificity toward the incoming substrate. Early insights into lysine recognition by and substrate specificity of E2 can be gleaned from the structural and functional characterization of E2Ubc9, the sole E2 in the SUMO pathway. This E2 can conjugate SUMO to target lysine residues in the absence of E3 when the lysine is within a ψ–K–x–D/E consensus motif (4, 90). Structural studies show that residues surrounding the E2 active site are important both for positioning the incoming lysine in an optimal geometry for conjugation and for providing a chemical environment that lowers the pKa of the lysine to promote nucleophilic attack (4, 122). In E2Ubc9, the critical residues are Tyr87, Cys93, Asn85, and Asp127 (human numbering) (4, 122). Conservation of this active-site geometry is observed in E2Ubc5 (22, 23, 72, 78, 79), E2Ubc13 (3, 29), E2Ubc1 (83), E2Ubc2 (51), E2Ube2S (114), and E2Cdc34 (13). The highly conserved Asn residue within the His-Pro-Asn (HPN) motif was suggested to stabilize the oxyanion intermediate formed during nucleophilic attack (29). More recently, Berndsen et al. (3) observed that the N79A and N79D mutations of E2Ubc13 lead to a reduced catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) (3 M−1s−1 and 4 M−1s−1, respectively, versus 22 M−1s−1 for wild type), suggesting that Asn79 stabilizes the active site but not the oxyanion charge. The E2 proteins involved in autophagy, Atg3 and Atg10, share conserved but distinct E2 active-site geometries in which a Tyr and His/Asn residue pair play key organizing roles (43, 119).

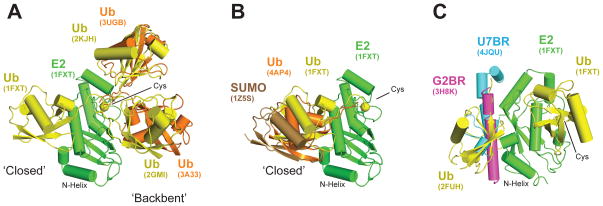

In addition to the covalent bond between E2~Ubl within a thioester complex, other noncovalent interactions play an important role in active site organization, Ubl activation, and Ubl discharge to substrate. Wickliffe et al. (114) demonstrate the interaction between the conserved (L8, I44, V70) hydrophobic patch of donor Ub and the E2Ube2S surface composed of α-helices A, B, and C is important for efficient Ub discharge (but not for lysine specificity), a requirement also observed for E2Ube2R1 and E2UbE2G2. Saha et al. (87) observe a similar interaction between the same surface of donor Ub and analogous regions of E2Cdc34 and E2Ubc5. Pruneda et al. (80) and Page et al. (73) used NMR and small-angle light scattering to explore the range of motions observed for thioester mimetic E2–Ubl complexes in crystal structures and in solution, and in doing so, they identified a range of Ubl motions relative to E2 from “backbent” to open to closed (Figure 2a). In contrast to E2Ubc5, which samples multiple conformations within this spectrum, E2Ubc13 alternates between closed and backbent conformations. The closed conformation is similar to that observed in the E2Ubc9/E3/substrate–SUMO complex (81) (see below) and modeled E2–Ubl donor interactions (87, 114). The propensity for some E2~Ubl thioester complexes to adopt the closed conformation primed for discharge may explain why, in the absence of E3, some E2s discharge Ubl to a substrate more readily than do others.

Figure 2.

Dynamics of E2~Ubl regulation. (a) E2 alignment of E2–Ubl thioester mimetic structures. For clarity, only E2Ubc1 (from PDB ID: 1FXT) is shown; the varied Ub positions are shown for the indicated PDB IDs. (b) E2 alignment of E3-bound E2–Ubl thioester mimetics (E2Ubc1–Ub from 1FXT is included for reference). E3 species have been removed for clarity. (c) Alignment of backside-binding E2 regulators on E2Ubc1–Ub (PDB ID: 1FXT). The E2 catalytic cysteine (Cys) is shown as a yellow sphere.

Abbreviations: PDB, Protein Data Bank; Ub, ubiquitin; Ubl, ubiquitin-like protein.

Lysine Specificity

The modification of specific lysine residues relies on their proper positioning within the E2 active site. The E2 active site orients the lysine nucleophile and the thioester bond in an optimal configuration to promote isopeptide bond formation. The following examples illustrate this further. Studies investigating E2Ubc1-catalyzed Lys48 linkage demonstrate that E2Ubc1 lacks an analogous residue to Tyr87 of E2Ubc9. Modeling and functional assays suggest that the acceptor Ub (the incoming substrate) participates in substrate-assisted catalysis by providing the analogous structural element via the Ub Tyr59 side chain. Several Ub E2s that lack a tyrosine residue at this position replace its functionality with a leucine residue that projects into the same space (83, 122). Assays of Ub Lys11 chain formation by E2Ube2S show that Lys6 on the acceptor Ub is recognized by Glu131 on E2Ube2S and contributes to chain elongation. In another instance of substrate-assisted catalysis, Glu34 from the acceptor Ub plays a structurally analogous role to that of Asp127 in E2Ubc9. Consistent with Lys11 specificity, other Ub lysine residues are not adjacent to similarly positioned aspartic acid/glutamic acid residues (114). Similarly, Ub Glu64 likely contributes to lysine specificity or recognition within the E2Ubc13/E2variantMms2 complex (29), and the acidic loop in E2Cdc34 contributes to Lys48 specificity (75). These examples show how cognate pairing between E2 and its target substrate promotes lysine selection and bond formation: Both proteins provide residues that create the active-site environment and that have interactions beyond the active site. Some authors have proposed that the environment surrounding target lysine residues and the resulting varied rates of conjugation may establish the timing of ubiquitination and the subsequent degradation of specific targets for E2s that function with the cullin-based skip-cullin F-box (SCF) and Anaphase Promoting Complex (APC/C) E3 ligases (85, 106, 117).

Ubl/E2 Backside Binding and Chain Formation

Noncovalent interactions between a Ubl and the backside of an E2 have been observed for Ub and E2Ubc5 (9) and for SUMO and E2Ubc9 (Figure 2c) (12, 27, 50). Disruption of noncovalent SUMO/E2Ubc9 interactions alters the rate of SUMO chain formation (12, 50) and hinders yeast growth, especially when challenged by DNA damage (27). Similarly, disruption of Ub/E2Ubc5 interactions disrupts Ub chain formation (9). In both cases, the mechanism behind reduced chain formation rates is not clear. Klug et al. (49) observed that (a) E2Ubc9 Lys154 can be modified with SUMO in vitro and in vivo and (b) loss of Lys154 modification leads to diminished polySUMO conjugate formation during meiosis. Biochemical studies suggest that the E2Ubc9–SUMO conjugate interacts with another E2Ubc9~SUMO thioester via noncovalent backside interactions that assist in forming chains by positioning the donor SUMO, but the exact mechanism and geometry of this complex awaits further structural analysis.

E2 Regulation

Consistent with their central role in Ubl conjugation, E2 proteins are subject to regulation. Serine 120 of Rad6/Ubc2 (human Ubc9 D127) is phosphorylated in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells in a cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) 1/2–dependent manner (91). Kinetic analysis of Ser120D (a phosphomimetic) indicates subtle effects on E1 binding and thioester transfer, whereas Ser120A and Ser120D cause pronounced defects in polyUb chain formation. Defects associated with Ser120A suggest that the serine side chain plays an important role in maintaining the E2 active site (as discussed above), whereas Ser120D defects suggest that Ser120 phosphorylation could effectively shut down Ubc2-dependent conjugation (51). E2 binding domains (Figure 2c), such as the gp78 E2Ube2g2 binding region (G2BR), can interact with the backside surface of E2. These interactions may cause conformational changes in loops that occlude the E2 active site and slow E1-catalyzed thioester transfer but that enhance affinity to and activity with the gp78 really interesting new gene (RING) domain (16). Binding of the gp78 RING domain disrupts G2BR binding to promote multiple turnovers (15). In contrast, the Ubc7p-binding region (UB7R) in Cue1p, another E2 backside surface binding domain, elicits conformational changes in the E2 active site that enhance the rate of E1 thioester transfer and that of Lys48-specific Ub chain formation (67). Another mechanism to regulate E2 is found in a peroxisomal E2 that has a unique disulfide bond between Cys105 (within an HCN motif, a conserved variation of the HPN motif) and Cys146. Although disulfide bond formation does not alter the overall E2 fold, reduction of this bond causes a narrowing of the E2 active site and a reduction in activity. These phenomena suggests that redox potential may regulate a subset of E2s (116). Finally, recent studies identified small-molecule Cdc34 inhibitors that bind away from the active site but that allosterically inactivate E2-mediated conjugation (13). It is not clear whether naturally occurring metabolites bind to this conserved E2 cavity, but it is attractive to consider this as a possible mechanism to modulate E2 activities.

E3 UBIQUITIN-LIKE PROTEIN LIGASES

E3 ligases represent the most diverse and evolutionarily refined activators of E2~Ubl mediated conjugation. E3 ligases bind the E2~Ubl thioester and activate the complex for discharge of Ubl to available nucleophiles including water, reducing agent, Tris, hydroxylamine, free lysine, or target substrates, especially in the absence of substrate specificity and regulatory domains. Different ligases accomplish this activation though a variety of domain and motif assemblies to direct bond formation.

The RING domain is a small globular fold stabilized by two zinc ions coordinated by eight cysteine or histidine residues, and it directly recruits E2 proteins (19). Two evolutionary variations on the RING domain include the U-box domain, which adopts a structurally homologous fold stabilized by side chain interactions in lieu of zinc ion–mediated cross bracing (1), and the Siz-Protein Inhibitor of Activated STAT (PIAS) RING (SP-RING) domain, which adopts a similar fold using one element stabilized by a zinc ion and another stabilized by side chain interactions (123). RING-like domains are typically observed appended to various domain architectures; many of these domain architectures include substrate-recognition domains, regulatory domains, and, in some cases, oligomerization domains.

Members of a second major class of E3 ligases share a common homologous to E6-associated protein C-terminus (HECT) domain. This E2 activating module promotes E2–E3 thioester transfer of Ub to an active-site cysteine within the HECT domain prior to substrate ligation. Appended N-terminal domains bind and position target substrates for conjugation.

RING-in-between-RING (RBR) proteins, a third class of E3 ligases, have posed an enigma to the field. The presence of a conserved RING fold (RING1) appended to additional Zn2+ coordinating domains led many to predict behaviors and activities consistent with those of other RING ligases. While exploring the apparent higher reactivity of E2UbcH7 for free cysteine compared with free lysine, Wenzel and colleagues (11, 96, 112) tested the functionality of E2UbcH7 with HECT domain E3s and RBR member HHARI. In a surprising turn, these authors determined that the RBR proteins HHARI and Parkin function via E2–E3 thioester transfer to a conserved cysteine residue in the RING2 domain, analogous to the behavior of HECT E3 ligases (112). Subsequent studies demonstrate anther RBR protein, HOIP (103), shares this unanticipated mechanism of function seen with Parkin and HHARI (25, 82, 101, 110, 111).

The following sections explore the mechanistic details revealed by studies addressing the SUMO-specific RanBP2 ligase, monomeric and dimeric RING-like domain ligases, cullin/RING domain ligases, RBR domain ligases, and, finally, HECT domain ligases. Because the activating module of RanBP2 (IR1-M-IR2) promotes target conjugation in the absence of contacts to the target substrate, RanGAP1, RanBP2 represents a natural transition from E2s and is discussed first.

RanBP2 (IR1-M-IR2)

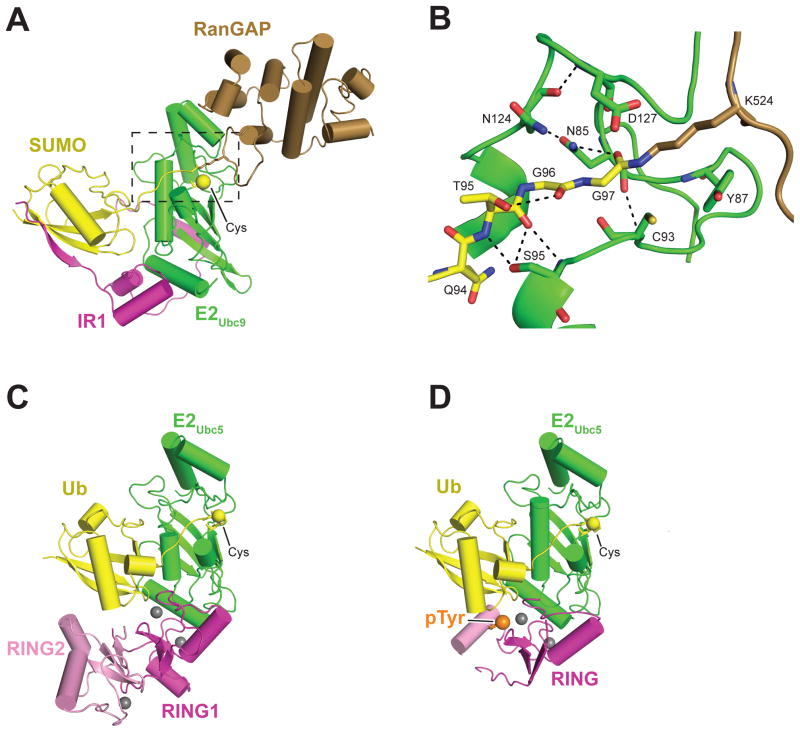

The RanBP2 nucleoporin protein is not related to RING or HECT E3 ligases, but it harbors an internal IR1–M–IR2 repeat that possesses E3 ligase activity and is responsible for tethering SUMO1-modified RanGAP1 at the vertebrate nuclear pore complex (NPC) (32, 76, 88, 89). The first structure of an intact quaternary complex between an E3, E2, and a Ubl-conjugated substrate was revealed through characterization of a IR1/E2Ubc9/RanGAP1–SUMO1 product complex that was captured in a conformation proposed to resemble the substrate complex prior to conjugation (Figure 3a). This structure illustrates how internal repeat (IR) elements interact with E2Ubc9 and SUMO1, scaffolding the closed and active conformation in the absence of contacts to the target substrate. The C-terminal tail of SUMO is extended, and the thioester is optimally positioned for attack by the incoming lysine residue (Figure 3b). Superposition on previous RING/E2 complexes suggests that IR1 and RING domains interact with similar E2 surfaces, leading Reverter & Lima (81) to propose that other E3 ligases would employ a similar mechanism to activate the E2~Ubl by templating the closed configuration primed for discharge.

Figure 3.

E3 ligases templating E2–Ubl into closed and active conformations. (a) SUMO ligase IR1 bound to E2Ubc9 and SUMO conjugated to RanGAP, (PDB ID: 1Z5S) (b) Zoom into the E2Ubc9 active site indicated by the box in panel a. (c) The RNF4 RING dimer with E2Ubc5–Ub thioester mimetic bound. The second E2Ubc5–Ub species is not shown for clarity (PDB ID: 4AP4). (d) CBL-B RING domain alone bound to E2Ubc5–Ub thioester mimetic (PDB ID: 3ZNI). Phosphorylated tyrosine (pTyr) is shown as an orange sphere. Zinc ions are represented by gray spheres, and the E2 catalytic cysteine (Cys) is shown as yellow sphere. Abbreviations: C, cysteine; D, aspartic acid; G, glycine; K, lysine; N, asparagine; PDB, Protein Data Bank; Q, glutamine; RING, really interesting new gene; RNF4, ring finger protein 4; S, serine; SUMO, small ubiquitin-like modifier protein; T, threonine; Ub, ubiquitin; Ubl, ubiquitin-like protein; Y, tyrosine.

Several studies have sought to determine how RanBP2 functions simultaneously as an E3 ligase and in tethering RanGAP1–SUMO1 at the NPC (76, 77, 81, 108, 127). Recent structures of RanGAP1–SUMO1/Ubc9/IR1 and RanGAP1–SUMO2/Ubc9/IR1 reveal determinants of SUMO1 specificity, as RanBP2 interacts with SUMO1 more extensively than does SUMO2 (33). Although IR2 exhibits some ligase activity with SUMO1 specificity, Gareu et al. (33) propose that IR1 is the dominant ligase for RanPB2 because IR1 maintains ligase activity in the presence of excess RanGAP1–SUMO1/Ubc9. These data are consistent with ligase activity resulting from dynamic exchange between IR1 interactions with RanGAP1–SUMO1/Ubc9 and Ubc9~SUMO1 (33). Werner et al. (113) have recently observed similar activities for IR1 and IR2, as well as that IR1 forms a more stable complex with RanGAP1–SUMO1/Ubc9 than does IR2. Because all detectable RanBP2 in cells is in complex with RanGAP1–SUMO1/Ubc9, these authors (113) propose the active ligase is created by a dynamic Ubc9~SUMO1/IR2 interaction that depends on a static complex between RanGAP1–SUMO1/Ubc9 and IR1. Structural characterization of an intact IR1–M–IR2 domain in complex with all of the constituents is needed to understand this system in greater detail.

Really Interesting New Gene (RING) Domain Ligase Complexes

Structures of RING domains bound to E2 proteins such as E2UbcH7/cCbl (126), E2Ubc5b/CNOT4 (20), E2Ubc5b/cIAP2 (63), and E2Ubc13/TRAF6 (121) reveal a conserved mode of E2/RING interaction. An analogous interface has been observed for E2/U-box domain interactions in E2Ubc13/CHIP (124) and E2Ubc5/E4B (2) complexes. E3 binding to E2 was predicted to allosterically activate the E2 active site (42, 99), and a network of residues in E2Ubc5 links the E3 binding interface to the E2 active site(72). However, the picture of E3-mediated activation is incomplete without considering the contribution of the thioester-linked Ubl, given that the E2~Ubl thioester is the true substrate. This contribution is highlighted by the importance of the noncovalent interactions between E2 and Ubl and the observed tighter binding to E3 for E2~Ubl compared with E2 alone (97, 102). Thus, the discussion below focuses on recent structures of RING/U-box domains bound to E2–Ubl thioester mimetics.

Structures with RING/U-box domains bound to E2–Ubl thioester analogs provide a unifying picture for E3-mediated E2~Ubl activation (22, 23, 78, 79). The RING/E2–Ubl homodimer structures recapitulate previously observed interactions between the RING domain and E2. Importantly, these structures reveal new and conserved contacts to the Ub protein that are mediated by adjacent residues in the same RING domain, as well as additional contacts contributed by the opposing RING domain. These contacts effectively template the E2–Ubl complex into the activated closed conformation (Figure 3c) (22, 78, 79) and thus explain the requirement for heterodimerization and homodimerization for many RING E3s (37, 57). Given structural conservation across the RING E3 ligase superfamily, these structures suggest a common mechanism for multimeric RING E3s and provide a rationale for the cooperative allostery observed for E2~Ub binding to the tripartite motif (TRIM) family of RING ligases (105).

A structure of the functionally monomeric RING protein CBL-B shows a similar arrangement for the bound E2–Ub thioester mimetic, except that buttressing support to Ub is mediated by a phosphorylated tyrosine on an α-helix beyond the RING domain (Figure 3d). The phosphorylated tyrosine is central to a network of interactions between the α-helix on which it is located, Ub, and the RING domain, again serving to template the E2~Ub into a closed activated conformation (23). This structure shows that monomeric RING domains function in an analogous manner to dimeric RING domains, thereby lending further credence to the proposed model for the SP-RING domain SUMO ligase Siz1 (123). In all of these structures, the tail of the Ub is fully extended and coordinated via an interaction network between the Ub tail residues, Gln92 of E2Ubc5, and a basic residue within a highly conserved Y–x–(K/R) motif present in RING/U-box domains (22, 23, 78, 79). Solution-based studies show that RING binding selects and stabilizes the closed conformation from the spectrum of open E2–Ubl conformations (Figure 2a,b) (100).

Cullin/Really Interesting New Gene (RING) Ligase Activation

The cullin/RING E3 ligase (CRL) family is a multiprotein complex that comprises a central cullin subunit interacting with both RING and substrate adaptor domains. Cullin subunits are curved elongated proteins that bind, through their N-terminal domains, a number of substrate-recognition modules (e.g., Fbox, VHL, SOCS box, DWD, BTB), often through adapter proteins (e.g., Skip1, Elongins, DDB1). The cullin C-terminal domain coordinates a single monomeric RING domain (Rbx1/Roc1/Hrt1). The CRLs represent a large protein family that regulates critical cellular functions, all of which are beyond the scope of this review. We encourage the reader to consult other reviews detailing the CRL family (17, 39), the assembly of CRLs (128), and their regulation (18, 26, 66, 74). The following section summarizes structural and mechanistic details of CRL activation by the Ubl Nedd8, RING domain dynamics, and interaction with the E2~Ubl.

The first published structure of a CRL complex detailed its overall architecture. Enigmatically, however, the E2 active site, determined on the basis of models of other RING/E2 structures, was ~50 Å away from the proposed substrate binding site (125). Conjugation of Nedd8 to a conserved lysine residue in cullin activates Ub conjugation both directly (5, 86) and indirectly through displacement of the inhibitor protein Lag2/CAND1 (59, 98). The RING domain Rbx1 is essential for Nedd8 conjugation to cullins both in vitro and in vivo (46). Subsequent studies identified Dcn1, which contains Ub-association (UBA) and potentiatior of Nedd8 (PONY) domains, as a Nedd8 ligase (53). The PONY domain binds cullin and the Nedd8-specific E2Ubc12, enhancing Nedd8 conjugation (52).

Scott et al. (95) showed that the PONY domain stimulates Nedd8 conjugation, but not ubiquitination, and stimulation of Nedd8 conjugation by E2Ubc12~Nedd8 requires the unique and conserved N-terminal extension of E2Ubc12. The crystal structure of the PONY domain/cullin complex, along with modeling of E2Ubc12 onto the RING domain, predicts that the N-terminus of E2Ubc12 binds to a conserved pocket in the Dcn1 PONY domain. Consistent with this role, Dcn1 causes a 5-fold increase in the Km for E2Ubc12 and a 35-fold increase in kcat. Interaction between the E2Ubc12 N-terminus and Dcn1 is mediated by a constitutive acetylation of the Ubc12 initiator methionine, which is buried in a hydrophobic pocket in Dcn1 (94). Acetylation is also required for interactions with the Nedd8-specific protein E2UBE2F and other Dcn1-like proteins (68).

The ECTD of Cul1 locks the RING domain in an inhibited state through extensive interactions. Deletion of the ECTD mimics Nedd8 conjugation mediated increases in ligase activity (120, 125), suggesting that Nedd8 modification releases inhibitory interactions between the ECTD and the RING domain (120). The crystal structure of Nedd8–Cul1CTD/Rbx1 reveals pronounced rearrangements of the individual domains in comparison with the arrangements observed in previous cullin/RING domain complexes. Importantly, the RING domain is freed from the ECTD and observed in two distinct conformations well away from Cul1. Linker length, spacing, and flexibility are all necessary for the RING domain to adopt the proper configuration for catalysis (24). Nedd8-dependent remodeling of cullin/RING domain interactions also dismantles the binding surface for the inhibitory protein Cand1, illustrating opposing roles for Nedd8 and Cand1 in CRL regulation (24, 36). The structure of the Cul1CTD/Rbx1 complex, which models an activated complex through deletion of the ECTD, finds the RING domain in yet another conformation, and modeling of E2Ubc12 onto this RING domain brings the E2 active-site cysteine within a few angstroms of the conserved lysine for Nedd8 modification. This and further functional assays suggest that additional remodeling of the ECTD may be required for full activation after Nedd8 conjugation (10). Understanding whether the CRL buttresses Nedd8 and/or Ub to promote a closed E2~Ubl conformation awaits further structural characterization.

RING-in-Between-RING (RBR) Ligases

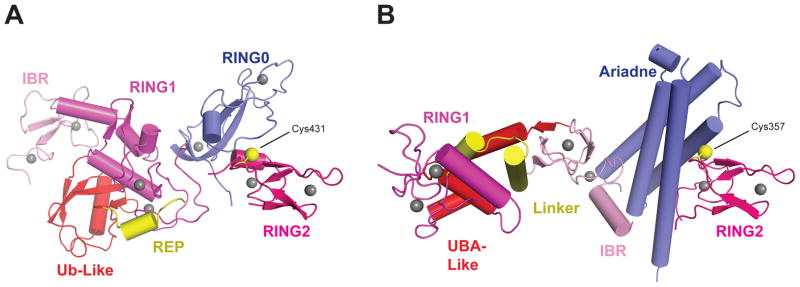

Recent structures for RBR members Parkin and HHARI reveal details about how these proteins function (Figure 4)(25, 82, 101, 110, 111). RBR proteins share a common primary structural arrangement of RING1-in-between- RING2 domains. In both Parkin and HHARI, RING1 binds the E2~Ub complex via the canonical E2/RING domain interface, and RING2 harbors the catalytic cysteine. Three crystal structures of Parkin show nearly identical folds for the individual RBR domains in similar autoinhibited tertiary structures (Figure 4a). Likewise, the crystal structure of HHARI shows that its individual RBR domains exhibit folds similar to those in Parkin, but HHARI adopts a different autoinhibited configuration (Figure 4b). The RING0 domain (unique to Parkin) packs between the RING1 and RING2 domains, burying the E3 active-site cysteine and distancing it from the predicted E2~Ub binding site. Further inhibition is imparted by a repressor element of Parkin (REP) motif that occludes the E2 binding surface (82, 101, 110, 111). In HHARI, the Ariadne domain plays an analogous role to that of the Parkin RING0 domain, occluding access to the active cysteine and partitioning the E2~Ub binding site. However, the RING1 domain appears free to bind E2 (25). Modeling of Parkin disease mutations onto the structures indicates three types of mutations: those that disrupt Zn2+ coordination or domain folding, those that disturb domain-domain or protein-protein interactions, and those that alter the active site. Destabilizing inhibitory packing arrangements functionally activate these enzymes in vitro and in vivo (14, 25, 82, 110, 111).

Figure 4.

Structures of the RBR E3 Ligases Parkin and HARI in Autoinhibited State. (a) Structure of Parkin (PDB IDs: 4K95 and 4K7D). (b) Structure of HHARI (PDB ID: 4KBL). Zinc ions are represented by gray spheres and the catalytic cysteines (Cys) on the RING2 domains are shown as yellow spheres. Abbreviations: IBR, in-between-RING; REP, repressor element helix; RING, really interesting new gene; UBA, ubiquitin associated domain; Ub-Like, ubiquitin-like.

The Cys430, His433, and Glu444 active-site residues in Parkin are functionally important, and their mutation greatly reduces Ub discharge, chain formation, and reactivity toward Ub-based suicide inhibitors (82, 101, 110, 111). Modification of the Parkin active site with Ub suicide inhibitors over a range of pH values indicates that His433 is important for deprotonation, whereas Glu444 and Thr443 support structural integrity of the active site (82, 101). Similarly, the HOIP active-site residues Cys885, His887, and Gln896 are necessary for Ub conjugation (111), and HHARI utilizes Cys357, His359, and Asn358. As Duda et al. (25) point out, HHARI lacks some of the structural elements that other RING domains utilize to activate and pin the E2~Ubl closed; this also appears to be true for Parkin. Further structural work is needed to elucidate the activated conformations for these E3 ligases.

Homologous to E6-AP C-Terminus (HECT) Domain--Based Ligases

HECT ligases share a common catalytic HECT domain, as illustrated by E6-associated protein (E6AP), which is composed of an N-lobe required for interaction with the E2UbcH7 (41) and a C-lobe that possesses the catalytic cysteine (Figure 5a). Kim et al. (47) show that E6AP catalyzes formation of Lys48-linked polyUb chains, whereas Rsp5 forms Lys63-linked chains. Linkage specificity appears to be inherent to the HECT domain independent of target substrate or E2 species, and may be mediated via mechanisms analogous to E2 active site coordination of select lysine residues to promote nucleophilic attack. Determinants for lysine specificity are further parsed to 60 C-terminal residues, which include three β-strands, the active-site cysteine loop, and the terminal α-helix. On the basis of biochemical evidence, Kim et al. (47) conclude that the thioester-linked Ub is the donor in a distal addition chain-elongation mechanism.

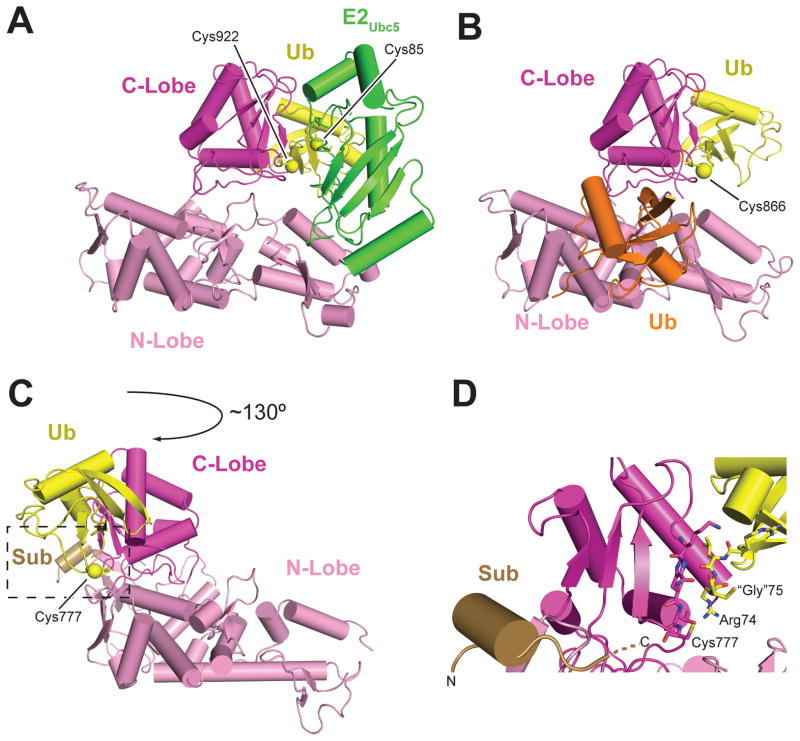

Figure 5.

Homologous to E6-AP C-terminus (HECT) domain conformations. (a) Nedd4 HECT domain with E2Ubc5–Ub thioester mimetic bound (PDB ID: 3JW0). (b) Disulfide cross-linked Nedd4 HECT domain and a Ub E3 thioester mimetic complex with noncovalent ubiquitin bound (PDB ID: 4BBN). (c) Cross-linked complex between the Rsp5 WW3 and HECT domains, Ub, and the Sna3 substrate peptide (PDB ID: 4LCD). (d) Zoomed in view of the HECT active site indicated by the box in panel c. E2 and E3 catalytic cysteines are shown as yellow spheres. “Gly” refers to the anticipated position of glycine 75 in ubiquitin, which has been mutated to cysteine in this structure for crystallization purposes. Abbreviations: Arg, arginine; Cys, cysteine; Gly, glycine; PDB, Protein Data Bank; Sub, substrate; Ub, ubiquitin.

The crystal structure of a catalytically inactive HECT domain from Nedd4L in complex with an E2Ubc5–Ub thioester mimetic shows E2 binding to the analogous site as that for E2UbcH7. However, the Ub moiety in this case binds the C-lobe, pulling the Ub C-terminal glycine within a few angstroms of the E3 active site (Figure 5a). The E2UbcH7 and E2Ubc5–Ub bound structures show similar conformations of the N-lobe, but with a shift of the C-lobe from a distal position away from bound E2 to one in which the cysteine residues are ~8 Å apart (Figure 5a), suggesting a conformation poised for E2–E3 thioester transfer. Mutating the C-lobe/Ub interface greatly reduces E3~Ub thioester formation, as do E2/E3 interface mutations. Nedd4L His920, Thr921, Phe923, Ubc5, Asn77, and Leu119 immobilize the Ub tail, whereas the active-site cysteine may form an electrostatic network with the Asn79, Asn80, and Ser85 (Cys85 in the active protein) residues in E2Ubc5. Mutation of these residues results in reduced E3 thioester formation (45). In both the disulfide-linked HECT–Ub structure (thioester mimetic) and the structure of a chemically cross-linked Rsp5WW3-HECT–Ub–Sna3C (target substrate) complex, the Ub is bound by the C-lobe. The Ub tail is cradled between the N- and C-lobes in an extended conformation stabilized by an intermolecular β-strand (analogous to the closed E2–Ubl complex described above), suggesting an ideal conformation for nucleophilic attack (Figure 5b–d) (44, 65).

For Nedd4-like family members the last residue is a strictly conserved acidic residue critical for polyUb chain formation but not for thioester formation. Data suggest that this residue loops back and participates in the E3 active site. This residue is not conserved in E6AP, and deletion of the analogous position in E6AP does not affect its activity; however, transplanting the last four residues of Nedd4 to E6AP alters the fidelity of Lys48 linkage specificity (65). In the Rsp5WW3-HECT–Ub–Sna3C complex, the N- and C-lobes pack together extensively, mediated in part by the “–4 Phe” interacting with Phe505 and Phe506 on the N-lobe. Mutating this interface disrupts HECT-mediated Ub discharge. Modeling suggests that the following Rsp5 active-site residues are important: Phe778 (for lysine orientation or deprotonation) and His775 and Thr776 (for thioester orientation). The Rsp5 WW3 domain binds the Sna3 PPxY motif, and activity assays indicate that this interaction optimally positions a substrate lysine 10–15 residues C-terminal of the PPxY motif (44).

Rochi, Klein, and Haas (84) present a kinetic study of E6AP activity that supports an alternative interpretation of the observed crystal structures that includes a binding model with two E2~Ub active sites. Inhibition studies with E2UbcH7–Ub (thioester analog) versus free and inactive E2UbcH7C86A suggest the presence of a second E2 binding site, and substrate inhibition at high UbcH7~Ub thioester concentrations further supports this two-site model. Considering further kinetic data, Ronchi et al. (84) propose an ordered mechanism involving E2UbcH7~Ub binding at site 1 (previously unobserved), followed by E2–E3 thioester transfer and subsequent binding of another UbcH7~Ub at site 2 (observed in structures). Ronchi et al. (84) observe E6AP to be capable of binding and elongating free polyUb chains, and they confirm the five C-terminal residues of E6AP as being important for polyUb chain synthesis but dispensable for E3 thioester formation. The authors (84) acknowledge that their kinetic study does not elucidate whether the mechanism of chain elongation proceeds by proximal or distal addition, but the presence of two E2~Ub binding sites and the synthesis of free chains may suggest a proximal mechanism built upon an E2 or E3 active-site cysteine.

Three crystal structures (for Nedd4, Nedd4L, and Rsp5) show a conserved Ub binding interface containing the HECT domain N-lobe(48, 64, 65). Ub binding at this interface is compatible with HECT E3 disulfide-linked Ub and E2 binding via the interface described above (Figure 5) (48, 65). Disruption of this noncovalent Ub interaction impairs polyUb chain formation and ubiquitination of substrates by diminishing chain elongation without decreasing E3 thioester formation. The Lys63 linkage specificity of Nedd4L is not altered by disrupting this interaction, nor is Ub positioned with Lys63 proximal to the E3 active site, suggesting that this noncovalent bound Ub is neither the donor nor acceptor Ub (64). Perhaps the interaction is important for securing the growing Ub chain. Even though lysine and substrate specificity appear to be inherent to the C-terminal region of the HECT domain, the kinetics suggest that the E2 plays a role in chain formation following E2–E3 thioester transfer, as evidenced by differences among the kcat of the rate-limiting step of chain elongation associated with different E2s (84). Future studies with these and other HECT domain members are required to unravel the mechanisms employed for chain elongation.

UBL REGULATION THROUGH CONFORMATIONAL CHANGES

Ubl conjugation enzymes undergo large and small conformational changes to accomplish their tasks (61). The E1 catalytic cycle is facilitated through the mechanical link between Ubl adenylation, E1 thioester bond formation, and E1–E2 thioester transfer, which requires large conformational changes. Although the E2 fold does not change conformation on a global scale, interactions with activators and regulators can alter active-site residues to regulate activity. However, the E2~Ubl complex adopts many conformations that must be closed by E3 ligases or other factors to activate it for conjugation. E3 ligase activity is also conformationally regulated. The CBL ligase undergoes conformational transitions as substrate binding releases the RING domain for E2 access, and phosphorylation of tyrosine residue(s) results in a conformational change that positions the E2~Ub thioester toward the substrate (21). Even with the conformational changes observed upon Nedd8 modification of cullins, the substrate and E2~Ub complex are still several angstroms apart. Liu et al. (58) observe that the cullins are dynamic scaffolds, each of which has unique flexibility that may accommodate specific spacing between the substrate and the E2~Ubl thioester. Nedd8 modification may also affect the degree of flexibility, effectively unlocking the cullin for activity (86). The RBR ligases adopt autoinhibited conformations in isolation and association between HOIL, HOIP and Sharpin within the linear ubiquitin assembly complex (LUBAC) regulates the activity of these ligases (103). Parkin also seems to require large-scale conformational changes for activation. The ligase PINK1 is capable of activating the Parkin~Ub thioester intermediate, suggesting that phosphorylation may play a role in domain rearrangement and activation. Disruption of the autoinhibited conformation of Parkin leads to a constitutively active protein implicated in Parkinson’s disease (55) in a manner dependent on Parkin’s N-terminal Ubl domain (14). HECT domain ligases are also observed in autoinhibited configurations in the context of the full-length proteins, and these autoinhibited conformations can be alleviated by protein-protein interactions or by phosphorylation (30, 115).

Our structural understanding of the mechanisms underlying Ubl conjugation has progressed, but the development of methods to trap and characterize physiologically relevant complexes remains a challenge for the field, particularly given the transient natures of these complexes and conformations. Future research will need to focus on determinants of specificity given the tertiary conservation among E1, E2, and E3 members. Of particular interest are how the Ub E1 activating enzyme balances specificity with plasticity to recognize approximately two dozen Ub-specific E2s and how Ubl E3 ligases select particular charged E2s to facilitate target substrate recognition, lysine selection, and specificity. These studies will require sophisticated techniques to trap relevant intermediates before, during, and after conjugation.

SUMMARY POINTS.

E1 activating enzymes cycle through conformational changes during E1 thioester formation and E1–E2 thioester transfer. E1 is a validated target for small molecules that inhibit Ubl pathways.

E2 proteins harbor active-site residues necessary for activating the E2~Ubl thioester and for promoting Ubl discharge. Noncovalent interactions between E2 and its cognate Ubl promote the closed activated conformation.

The E2 active-site conformation and activity are subject to allosteric regulation by E3 ligases, regulators, and modifications.

RanBP2 and RING domain E3 ligases are allosteric activators of the E2~Ubl complex by templating a closed conformation primed for nucleophilic attack.

E3 ligases that harbor active-site cysteine residues and catalyze E2–E3 thioester transfer mediate E2~Ubl activation during the transfer and E3~Ubl activation for substrate conjugation. HECT ligases coordinate and position Ub in a conformation similar to that of the closed E2~Ubl complex.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award number R01GM065872 to C.D.L.

Footnotes

We use the following convention for identifying the types of complexes formed through ought this discussion: A dash (−) indicates a covalent linkage (other than thioester), a tilde (~) indicates a thioester covalent bond, and a slash (/) indicates noncovalent interactions between delineated proteins.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. C.D.L is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors are not aware of any affiliations, memberships, funding, or financial holdings that might be perceived as affecting the objectivity of this review.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Aravind L, Koonin EV. The U box is a modified RING finger---a common domain in ubiquitination. Curr Biol. 2000;10:R132–34. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00398-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benirschke RC, Thompson JR, Nomine Y, Wasielewski E, Juranic N, et al. Molecular basis for the association of human E4B U box ubiquitin ligase with E2-conjugating enzymes UbcH5c and Ubc4. Structure. 2010;18:955–65. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berndsen CE, Wiener R, Yu IW, Ringel AE, Wolberger C. A conserved asparagine has a structural role in ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes. Nat Chem Biol. 2013;9:154–56. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernier-Villamor V, Sampson DA, Matunis MJ, Lima CD. Structural basis for E2-mediated SUMO conjugation revealed by a complex between ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme Ubc9 and RanGAP1. Cell. 2002;108:345–56. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00630-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boh BK, Smith PG, Hagen T. Neddylation-induced conformational control regulates cullin RING ligase activity in vivo. J Mol Biol. 2011;409:136–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bossis G, Melchior F. Regulation of SUMOylation by reversible oxidation of SUMO conjugating enzymes. Mol Cell. 2006;21:349–57. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bracher PJ, Snyder PW, Bohall BR, Whitesides GM. The relative rates of thiol-thioester exchange and hydrolysis for alkyl and aryl thioalkanoates in water. Orig Life Evol Biosph. 2011;41:399–412. doi: 10.1007/s11084-011-9243-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brownell JE, Sintchak MD, Gavin JM, Liao H, Bruzzese FJ, et al. Substrate-assisted inhibition of ubiquitin-like protein-activating enzymes: the NEDD8 E1 inhibitor MLN4924 forms a NEDD8-AMP mimetic in situ. Mol Cell. 2010;37:102–11. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brzovic PS, Lissounov A, Christensen DE, Hoyt DW, Klevit RE. A UbcH5/ubiquitin noncovalent complex is required for processive BRCA1-directed ubiquitination. Mol Cell. 2006;21:873–80. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calabrese MF, Scott DC, Duda DM, Grace CR, Kurinov I, et al. A RING E3-substrate complex poised for ubiquitin-like protein transfer: structural insights into cullin-RING ligases. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:947–49. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Capili AD, Edghill EL, Wu K, Borden KL. Structure of the C-terminal RING finger from a RING-IBR-RING/TRIAD motif reveals a novel zinc-binding domain distinct from a RING. J Mol Biol. 2004;340:1117–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Capili AD, Lima CD. Structure and analysis of a complex between SUMO and Ubc9 illustrates features of a conserved E2-Ubl interaction. J Mol Biol. 2007;369:608–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ceccarelli DF, Tang X, Pelletier B, Orlicky S, Xie W, et al. An allosteric inhibitor of the human cdc34 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme. Cell. 2011;145:1075–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chaugule VK, Burchell L, Barber KR, Sidhu A, Leslie SJ, et al. Autoregulation of Parkin activity through its ubiquitin-like domain. EMBO J. 2011;30:2853–67. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Das R, Liang YH, Mariano J, Li J, Huang T, et al. Allosteric regulation of E2:E3 interactions promote a processive ubiquitination machine. EMBO J. 2013;32:2504–16. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Das R, Mariano J, Tsai YC, Kalathur RC, Kostova Z, et al. Allosteric activation of E2-RING finger-mediated ubiquitylation by a structurally defined specific E2-binding region of gp78. Mol Cell. 2009;34:674–85. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deshaies RJ. SCF and Cullin/Ring H2-based ubiquitin ligases. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1999;15:435–67. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.15.1.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deshaies RJ, Emberley ED, Saha A. Control of cullin-ring ubiquitin ligase activity by nedd8. Subcell Biochem. 2010;54:41–56. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-6676-6_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deshaies RJ, Joazeiro CA. RING domain E3 ubiquitin ligases. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:399–434. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.101807.093809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dominguez C, Bonvin AM, Winkler GS, van Schaik FM, Timmers HT, Boelens R. Structural model of the UbcH5B/CNOT4 complex revealed by combining NMR, mutagenesis, and docking approaches. Structure. 2004;12:633–44. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dou H, Buetow L, Hock A, Sibbet GJ, Vousden KH, Huang DT. Structural basis for autoinhibition and phosphorylation-dependent activation of c-Cbl. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:184–92. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dou H, Buetow L, Sibbet GJ, Cameron K, Huang DT. BIRC7-E2 ubiquitin conjugate structure reveals the mechanism of ubiquitin transfer by a RING dimer. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:876–83. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dou H, Buetow L, Sibbet GJ, Cameron K, Huang DT. Essentiality of a non-RING element in priming donor ubiquitin for catalysis by a monomeric E3. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:982–86. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duda DM, Borg LA, Scott DC, Hunt HW, Hammel M, Schulman BA. Structural insights into NEDD8 activation of cullin-RING ligases: conformational control of conjugation. Cell. 2008;134:995–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duda DM, Olszewski JL, Schuermann JP, Kurinov I, Miller DJ, et al. Structure of HHARI, a RING-IBR-RING ubiquitin ligase: autoinhibition of an Ariadne-family E3 and insights into ligation m\Mechanism. Structure. 2013;21:1030–41. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duda DM, Scott DC, Calabrese MF, Zimmerman ES, Zheng N, Schulman BA. Structural regulation of cullin-RING ubiquitin ligase complexes. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2011;21:257–64. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duda DM, van Waardenburg RC, Borg LA, McGarity S, Nourse A, et al. Structure of a SUMO-binding-motif mimic bound to Smt3p-Ubc9p: conservation of a non-covalent ubiquitin-like protein-E2 complex as a platform for selective interactions within a SUMO pathway. J Mol Biol. 2007;369:619–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duda DM, Walden H, Sfondouris J, Schulman BA. Structural analysis of Escherichia coli ThiF. J Mol Biol. 2005;349:774–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eddins MJ, Carlile CM, Gomez KM, Pickart CM, Wolberger C. Mms2-Ubc13 covalently bound to ubiquitin reveals the structural basis of linkage-specific polyubiquitin chain formation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:915–20. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gallagher E, Gao M, Liu YC, Karin M. Activation of the E3 ubiquitin ligase Itch through a phosphorylation-induced conformational change. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:1717–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510664103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garber K. Missing the target: ubiquitin ligase drugs stall. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:166–67. doi: 10.1093/jnci/97.3.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gareau JR, Lima CD. The SUMO pathway: emerging mechanisms that shape specificity, conjugation and recognition. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:861–71. doi: 10.1038/nrm3011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gareau JR, Reverter D, Lima CD. Determinants of small ubiquitin-like modifier 1 (SUMO1) protein specificity, E3 ligase, and SUMO-RanGAP1 binding activities of nucleoporin RanBP2. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:4740–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.321141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gavin JM, Chen JJ, Liao H, Rollins N, Yang X, et al. Mechanistic studies on activation of ubiquitin and di-ubiquitin-like protein, FAT10, by ubiquitin-like modifier activating enzyme 6, Uba6. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:15512–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.336198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Geng J, Klionsky DJ. The Atg8 and Atg12 ubiquitin-like conjugation systems in macroautophagy. ‘Protein modifications: beyond the usual suspects’ review series. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:859–64. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goldenberg SJ, Cascio TC, Shumway SD, Garbutt KC, Liu J, et al. Structure of the Cand1-Cul1-Roc1 complex reveals regulatory mechanisms for the assembly of the multisubunit cullin-dependent ubiquitin ligases. Cell. 2004;119:517–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hashizume R, Fukuda M, Maeda I, Nishikawa H, Oyake D, et al. The RING heterodimer BRCA1-BARD1 is a ubiquitin ligase inactivated by a breast cancer-derived mutation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:14537–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000881200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hong SB, Kim BW, Lee KE, Kim SW, Jeon H, et al. Insights into noncanonical E1 enzyme activation from the structure of autophagic E1 Atg7 with Atg8. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:1323–30. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hua Z, Vierstra RD. The cullin-RING ubiquitin-protein ligases. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2011;62:299–334. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042809-112256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang DT, Hunt HW, Zhuang M, Ohi MD, Holton JM, Schulman BA. Basis for a ubiquitin-like protein thioester switch toggling E1-E2 affinity. Nature. 2007;445:394–98. doi: 10.1038/nature05490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang L, Kinnucan E, Wang G, Beaudenon S, Howley PM, et al. Structure of an E6AP-UbcH7 complex: insights into ubiquitination by the E2-E3 enzyme cascade. Science. 1999;286:1321–26. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5443.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Joazeiro CA, Wing SS, Huang H, Leverson JD, Hunter T, Liu YC. The tyrosine kinase negative regulator c-Cbl as a RING-type, E2-dependent ubiquitin-protein ligase. Science. 1999;286:309–12. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5438.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaiser SE, Mao K, Taherbhoy AM, Yu S, Olszewski JL, et al. Noncanonical E2 recruitment by the autophagy E1 revealed by Atg7-Atg3 and Atg7-Atg10 structures. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:1242–49. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kamadurai HB, Qiu Y, Deng A, Harrison JS, Macdonald C, et al. Mechanism of ubiquitin ligation and lysine prioritization by a HECT E3. Elife. 2013;2:e00828. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kamadurai HB, Souphron J, Scott DC, Duda DM, Miller DJ, et al. Insights into ubiquitin transfer cascades from a structure of a UbcH5B~ubiquitin-HECT(NEDD4L) complex. Mol Cell. 2009;36:1095–102. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kamura T, Conrad MN, Yan Q, Conaway RC, Conaway JW. The Rbx1 subunit of SCF and VHL E3 ubiquitin ligase activates Rub1 modification of cullins Cdc53 and Cul2. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2928–33. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.22.2928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim HC, Huibregtse JM. Polyubiquitination by HECT E3s and the determinants of chain type specificity. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:3307–18. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00240-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim HC, Steffen AM, Oldham ML, Chen J, Huibregtse JM. Structure and function of a HECT domain ubiquitin-binding site. EMBO Rep. 2011;12:334–41. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Klug H, Xaver M, Chaugule VK, Koidl S, Mittler G, et al. Ubc9 sumoylation controls SUMO chain formation and meiotic synapsis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell. 2013;50:625–36. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Knipscheer P, van Dijk WJ, Olsen JV, Mann M, Sixma TK. Noncovalent interaction between Ubc9 and SUMO promotes SUMO chain formation. EMBO J. 2007;26:2797–807. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kumar B, Lecompte KG, Klein JM, Haas AL. Ser(120) of Ubc2/Rad6 regulates ubiquitin-dependent N-end rule targeting by E3α/Ubr1. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:41300–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.169136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kurz T, Chou YC, Willems AR, Meyer-Schaller N, Hecht ML, et al. Dcn1 functions as a scaffold-type E3 ligase for cullin neddylation. Mol Cell. 2008;29:23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kurz T, Ozlu N, Rudolf F, O’Rourke SM, Luke B, et al. The conserved protein DCN-1/Dcn1p is required for cullin neddylation in C. elegans and S. cerevisiae. Nature. 2005;435:1257–61. doi: 10.1038/nature03662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lake MW, Wuebbens MM, Rajagopalan KV, Schindelin H. Mechanism of ubiquitin activation revealed by the structure of a bacterial MoeB-MoaD complex. Nature. 2001;414:325–29. doi: 10.1038/35104586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lazarou M, Narendra DP, Jin SM, Tekle E, Banerjee S, Youle RJ. PINK1 drives Parkin self-association and HECT-like E3 activity upstream of mitochondrial binding. J Cell Biol. 2013;200:163–72. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201210111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee I, Schindelin H. Structural insights into E1-catalyzed ubiquitin activation and transfer to conjugating enzymes. Cell. 2008;134:268–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Linke K, Mace PD, Smith CA, Vaux DL, Silke J, Day CL. Structure of the MDM2/MDMX RING domain heterodimer reveals dimerization is required for their ubiquitylation in trans. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:841–48. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu J, Nussinov R. Flexible cullins in cullin-RING E3 ligases allosterically regulate ubiquitination. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:40934–42. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.277236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu Y, Mimura S, Kishi T, Kamura T. A longevity protein, Lag2, interacts with SCF complex and regulates SCF function. EMBO J. 2009;28:3366–77. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lois LM, Lima CD. Structures of the SUMO E1 provide mechanistic insights into SUMO activation and E2 recruitment to E1. EMBO J. 2005;24:439–51. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lorenz S, Cantor AJ, Rape M, Kuriyan J. Macromolecular juggling by ubiquitylation enzymes. BMC Biol. 2013;11:65. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-11-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lu X, Olsen SK, Capili AD, Cisar JS, Lima CD, Tan DS. Designed semisynthetic protein inhibitors of Ub/Ubl E1 activating enzymes. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:1748–49. doi: 10.1021/ja9088549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mace PD, Linke K, Feltham R, Schumacher FR, Smith CA, et al. Structures of the cIAP2 RING domain reveal conformational changes associated with ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2) recruitment. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:31633–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804753200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Maspero E, Mari S, Valentini E, Musacchio A, Fish A, et al. Structure of the HECT:ubiquitin complex and its role in ubiquitin chain elongation. EMBO Rep. 2011;12:342–49. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Maspero E, Valentini E, Mari S, Cecatiello V, Soffientini P, et al. Structure of a ubiquitin-loaded HECT ligase reveals the molecular basis for catalytic priming. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:696–701. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Merlet J, Burger J, Gomes JE, Pintard L. Regulation of cullin-RING E3 ubiquitin-ligases by neddylation and dimerization. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:1924–38. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-8712-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Metzger MB, Liang YH, Das R, Mariano J, Li S, et al. A structurally unique E2-binding domain activates ubiquitination by the ERAD E2, Ubc7p, through multiple mechanisms. Mol Cell. 2013;50:516–27. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Monda JK, Scott DC, Miller DJ, Lydeard J, King D, et al. Structural conservation of distinctive N-terminal acetylation-dependent interactions across a family of mammalian NEDD8 ligation enzymes. Structure. 2013;21:42–53. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Noda NN, Satoo K, Fujioka Y, Kumeta H, Ogura K, et al. Structural basis of Atg8 activation by a homodimeric E1, Atg7. Mol Cell. 2011;44:462–75. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Olsen SK, Capili AD, Lu X, Tan DS, Lima CD. Active site remodelling accompanies thioester bond formation in the SUMO E1. Nature. 2010;463:906–12. doi: 10.1038/nature08765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Olsen SK, Lima CD. Structure of a ubiquitin E1-E2 complex: insights to E1-E2 thioester transfer. Mol Cell. 2013;49:884–96. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Özkan E, Yu H, Deisenhofer J. Mechanistic insight into the allosteric activation of a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme by RING-type ubiquitin ligases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:18890–95. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509418102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Page RC, Pruneda JN, Amick J, Klevit RE, Misra S. Structural insights into the conformation and oligomerization of E2~ubiquitin conjugates. Biochemistry. 2012;51:4175–87. doi: 10.1021/bi300058m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Petroski MD, Deshaies RJ. Function and regulation of cullin-RING ubiquitin ligases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:9–20. doi: 10.1038/nrm1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Petroski MD, Deshaies RJ. Mechanism of lysine 48-linked ubiquitin-chain synthesis by the cullin-RING ubiquitin-ligase complex SCF-Cdc34. Cell. 2005;123:1107–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pichler A, Gast A, Seeler JS, Dejean A, Melchior F. The nucleoporin RanBP2 has SUMO1 E3 ligase activity. Cell. 2002;108:109–20. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00633-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pichler A, Knipscheer P, Saitoh H, Sixma TK, Melchior F. The RanBP2 SUMO E3 ligase is neither HECT- nor RING-type. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:984–91. doi: 10.1038/nsmb834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Plechanovova A, Jaffray EG, Tatham MH, Naismith JH, Hay RT. Structure of a RING E3 ligase and ubiquitin-loaded E2 primed for catalysis. Nature. 2012;489:115–20. doi: 10.1038/nature11376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pruneda JN, Littlefield PJ, Soss SE, Nordquist KA, Chazin WJ, et al. Structure of an E3:E2~Ub complex reveals an allosteric mechanism shared among RING/U-box ligases. Mol Cell. 2012;47:933–42. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pruneda JN, Stoll KE, Bolton LJ, Brzovic PS, Klevit RE. Ubiquitin in motion: structural studies of the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme~ubiquitin conjugate. Biochemistry. 2011;50:1624–33. doi: 10.1021/bi101913m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Reverter D, Lima CD. Insights into E3 ligase activity revealed by a SUMO-RanGAP1-Ubc9-Nup358 complex. Nature. 2005;435:687–92. doi: 10.1038/nature03588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Riley BE, Lougheed JC, Callaway K, Velasquez M, Brecht E, et al. Structure and function of Parkin E3 ubiquitin ligase reveals aspects of RING and HECT ligases. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1982. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rodrigo-Brenni MC, Foster SA, Morgan DO. Catalysis of lysine 48-specific ubiquitin chain assembly by residues in E2 and ubiquitin. Mol Cell. 2010;39:548–59. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ronchi VP, Klein JM, Haas AL. E6AP/UBE3A ubiquitin ligase harbors two E2~ubiquitin binding sites. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:10349–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.458059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sadowski M, Suryadinata R, Lai X, Heierhorst J, Sarcevic B. Molecular basis for lysine specificity in the yeast ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme Cdc34. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:2316–29. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01094-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Saha A, Deshaies RJ. Multimodal activation of the ubiquitin ligase SCF by Nedd8 conjugation. Mol Cell. 2008;32:21–31. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Saha A, Lewis S, Kleiger G, Kuhlman B, Deshaies RJ. Essential role for ubiquitin-ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme interaction in ubiquitin discharge from Cdc34 to substrate. Mol Cell. 2011;42:75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Saitoh H, Pu R, Cavenagh M, Dasso M. RanBP2 associates with Ubc9p and a modified form of RanGAP1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3736–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Saitoh H, Sparrow DB, Shiomi T, Pu RT, Nishimoto T, et al. Ubc9p and the conjugation of SUMO-1 to RanGAP1 and RanBP2. Curr Biol. 1998;8:121–24. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sampson DA, Wang M, Matunis MJ. The small ubiquitin-like modifier-1 (SUMO-1) consensus sequence mediates Ubc9 binding and is essential for SUMO-1 modification. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:21664–69. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100006200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sarcevic B, Mawson A, Baker RT, Sutherland RL. Regulation of the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme hHR6A by CDK-mediated phosphorylation. EMBO J. 2002;21:2009–18. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.8.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Schrödinger LLC. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. 2010 Version 1.3r1. http://www.pymol.org/pymol.

- 93.Schulman BA, Harper JW. Ubiquitin-like protein activation by E1 enzymes: the apex for downstream signalling pathways. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:319–31. doi: 10.1038/nrm2673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Scott DC, Monda JK, Bennett EJ, Harper JW, Schulman BA. N-terminal acetylation acts as an avidity enhancer within an interconnected multiprotein complex. Science. 2011;334:674–78. doi: 10.1126/science.1209307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Scott DC, Monda JK, Grace CR, Duda DM, Kriwacki RW, et al. A dual E3 mechanism for Rub1 ligation to Cdc53. Mol Cell. 2010;39:784–96. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Shimura H, Hattori N, Kubo S, Mizuno Y, Asakawa S, et al. Familial Parkinson disease gene product, parkin, is a ubiquitin-protein ligase. Nat Genet. 2000;25:302–5. doi: 10.1038/77060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Siepmann TJ, Bohnsack RN, Tokgîz Z, Baboshina OV, Haas AL. Protein interactions within the N-end rule ubiquitin ligation pathway. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:9448–57. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211240200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Siergiejuk E, Scott DC, Schulman BA, Hofmann K, Kurz T, Peter M. Cullin neddylation and substrate-adaptors counteract SCF inhibition by the CAND1-like protein Lag2 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 2009;28:3845–56. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Skowyra D, Koepp DM, Kamura T, Conrad MN, Conaway RC, et al. Reconstitution of G1 cyclin ubiquitination with complexes containing SCFGrr1 and Rbx1. Science. 1999;284:662–65. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5414.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Soss SE, Klevit RE, Chazin WJ. Activation of UbcH5c~Ub is the result of a shift in interdomain motions of the conjugate bound to U-box E3 ligase E4B. Biochemistry. 2013;52:2991–99. doi: 10.1021/bi3015949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]