Abstract

Twelve embryogenesis abundant protein (LEA) genes (named ThLEA-1 to -12) were cloned from Tamarix hispida. The expression profiles of these genes in response to NaCl, PEG, and abscisic acid (ABA) in roots, stems, and leaves of T. hispida were assessed using real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). These ThLEAs all showed tissue-specific expression patterns in roots, stems, and leaves under normal growth conditions. However, they shared a high similar expression patterns in the roots, stems, and leaves when exposed to NaCl and PEG stress. Furthermore, ThLEA-1, -2, -3, -4, and -11 were induced by NaCl and PEG, but ThLEA-5, -6, -8, -10, and -12 were downregulated by salt and drought stresses. Under ABA treatment, some ThLEA genes, such as ThLEA-1, -2, and -3, were only slightly differentially expressed in roots, stems, and leaves, indicating that they may be involved in the ABA-independent signaling pathway. These findings provide a basis for the elucidation of the function of LEA genes in future work.

1. Introduction

Adverse environmental conditions, such as salt, drought, and high temperatures, severely limit the growth and geographical distribution of many plants. At the same time, plants have evolved many mechanisms to tolerate these adverse conditions [1–5], and the regulation of gene expression is critical for these processes [6]. Late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) genes play important roles in stress tolerance, especially in drought stress. In wheat, there are several genes which are responsible for drought stress tolerance and produce different types of enzymes and proteins, for instance, late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) protein, responsive to abscisic acid (Rab), rubisco, helicase, proline, glutathione-S-transferase (GST), and carbohydrates during drought stress [7]. The LEA proteins to be firstly identified were from cotton, and they were highly synthesized during the later stages of embryogenesis [8].

To date, hundreds of LEAs have been cloned from different plant species [9]. Some LEA genes are highly induced by various abiotic or biotic stress treatments including salt [10, 11], drought or osmotic stress [12, 13], heat [14], cold [15, 16], and wounding [17]. In addition, the expression of LEA genes are also modulated by abscisic acid (ABA) [10, 18] and ethylene [17]. Transformed plants that overexpress LEA genes show improved tolerance to salt stress [19, 20], water deficit or drought conditions [10, 21], and cold [16, 22], but they are hypersensitive to ABA [23].

However, to date the true functions of LEAs are not fully understood. Therefore, analyzing the expression patterns of LEA genes will be beneficial to understanding their role in stress responses. Tamarix hispida, a woody halophyte, is widely distributed in drought-stricken areas and saline or saline-alkali soil in Central Asia and China. This species is highly tolerant to salt, drought, and high temperature, which makes it the desirable tree special to study the salt tolerance mechanism and clone the genes involved in salt tolerance.

In the present study, 12 ThLEA genes were cloned from T. hispida, and the expression patterns of these genes were determined in response to salt (NaCl), drought (PEG), and abscisic acid (ABA) treatments in the roots, stems, and leaves by using real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Our study may provide the fundament data for studying the function of LEA genes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Treatments

Seedlings of T. hispida were grown in pots with a mixture of turf peat and sand (2 : 1 v/v) in a greenhouse at 70–75% relative humidity, light/dark cycle of 14/10 h, and the temperature of 24°C. Two-month-old seedlingswere used for experimental analyses. The seedlings were watered at the roots with one of the following solutions: 0.4 M NaCl, 20% (w/v) PEG6000, or 100 μM ABA for 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 h. In controls, the seedlings were watered with the same volume of fresh water. Following these treatments, the leaves, stems, and roots from at least 20 seedlings were harvested and pooled, frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C for RNA preparation. Three samples were used for real-time RT-PCR biological repeats.

2.2. Cloning of the LEA Genes from T. hispida

In a previous study, 11 cDNA libraries of T. hispida treated with NaHCO3 were constructed using Solexa technology, which were the 8 libraries, respectively, from roots of T. hispida treated with NaHCO3 for 0, 12, 24, and 48 h (2 libraries were built from each treatment as biological replication) and 3 libraries from leaves of T. hispida treated with NaHCO3 for 0, 12, and 24 h. In total 94,359 nonredundant unigenes of >200 nt in length were generated using the SOAP de novo software. Subsequently, these unigenes were searched against the Nr database and the Swiss-Prot database using blastx (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) with a cut-off E-value of 10−5 [24, 25]. The unigenes representing the “LEA” genes were queried and identified from these libraries according to the functional annotation. Then, primers for the LEA genes were designed according to these sequences. RT-PCR and resequencing were used to confirm the LEA sequences.

2.3. Sequence Alignments and Phylogenetic Analysis

Firstly, the open reading frames (ORFs) of all the LEA unigenes (named as ThLEA-1 to -12) were identified using the ORF finder tools from the NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gorf/gorf.html). Subsequently, the LEAs with complete ORFs were subjected to molecular weight (MW) and isoelectronic point (pI) predictions using the Compute pI/Mw tool (http://www.expasy.org/tools/protparam.html). Subcellular location predictions for these genes were undertaken using the Target P1.1 Server (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TargetP/). All the LEA proteins from T. hispida and 51 Arabidopsis LEA proteins were subjected to phylogenetic analysis by constructing a phylogenetic tree by the neighbor-joining (NJ) method in ClustalX.

2.4. RNA Extraction and Reverse Transcription (RT)

Total RNA was isolated from the roots, stems, and leaves using the CTAB method. Total RNA was digested with DNase I (Promega) to remove any residual DNA. Approximately 1 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA in a 10 μL volume using oligodeoxythymidine and 6-bp random primers following the PrimeScript RT reagent kit (TaKaRa) protocol. The synthesized cDNAs were diluted 10-fold with sterile water and used as templates for real-time RT-PCR.

2.5. Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR

Real-time RT-PCR was carried out in an Opticon machine (Biorad, Hercules, CA) using a real-time PCR MIX Kit (SYBR Green as the fluorescent dye, TOKOBO) and the primers used are shown in Table 1. The alpha tubulin (FJ618518), beta tubulin (FJ618519), and actin (FJ618517) genes were used as internal controls (reference genes) to normalize the total RNA amount present in each reaction. The reaction mixture (20 μL) contained 10 μL of SYBR Green Real-Time PCR Master Mix (Toyobo), 0.5 μM of forward and reverse primer, and 2 μL of cDNA template (equivalent to 20 ng of total RNA). The amplification was performed using the following cycling parameters: 94°C for 30 s, followed by 45 cycles of 94°C for 12 s, 60°C for 30 s, 72°C for 40 s, and then at 81°C for 1 s for plate reading. A melting curve was generated for each sample at the end of each run to assess the purity of the amplified product. Real-time RT-PCR was carried out in triplicate to ensure the reproducibility of the results. The expression levels were calculated from the threshold cycle according to 2−ΔΔCt [26].

Table 1.

Primers used for quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis.

| Gene | GenBank accession number | Forward primer (5′-3′) | Reverse primer (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ThLEA-1 | KF801660 | CAGCGAAGTTTGGATGGAATG | ACCTGTCGCCAATCAGAAGAT |

| ThLEA-2 | KF801661 | CACACAATAGAAACCGTAGAG | CCTCCATGGTCTCCTTAACT |

| ThLEA-3 | KF801662 | CGAGATCCTTGGTGGAGCTCG | TCACGTATGTGTCATGACTAC |

| ThLEA-4 | KF801663 | GTGGCTATCTCGATTCGTAGT | GCAACAGACACCAACCAAGAT |

| ThLEA-5 | KF801664 | GTTCGCAGCAGGAAAGAGCAG | ACTCCGTCAACACGGTACTACT |

| ThLEA-6 | KF801665 | GTTGAGGATGTGGATATCAAG | CGAGTTCATAATCGATATCC |

| ThLEA-7 | KF801666 | TCATGATATTGGTGAGAAG | AGTGGTATCTTAACAGTCTCT |

| ThLEA-8 | KF801667 | GATGACGACACATGATGAAGC | AGCCTCCACAGTCCCTTCCGT |

| ThLEA-9 | KF924555 | GTGGTTGTGGAGATGAACGGAG | GGTAGCAGCATCATCAGCAATG |

| ThLEA-10 | KF924556 | AGAGTCAGCAACCGATACAGC | TCTCTGCCTTGCTGATTCCTC |

| ThLEA-11 | KF924557 | ACGGAGGAAGCTAGGCACGAAG | CTGCTGCGTCCTTGTATTCC |

| ThLEA-12 | KF924558 | CAAGATGCAGGAGGTGGTGAT | ATCTGCTATTCTTCTGCCTGT |

| Actin | FJ618517 | AAACAATGGCTGATGCTG | ACAATACCGTGCTCAATAGG |

| α-Tubulin | FJ618518 | CACCCACCGTTGTTCCAG | ACCGTCGTCATCTTCACC |

| β-Tubulin | FJ618519 | GGAAGCCATAGAAAGACC | CAACAAATGTGGGATGCT |

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of ThLEAs

In total, 12 unique ThLEAs (ThLEA-1-8, respectively, with the GenBank numbers KF801660 to KF801667; ThLEA-9-12, respectively, with the GenBank numbers KF924555 to KF924558) that are expressed differentially in response to at least one stress were identified from the T. hispida cDNA libraries. Among these, eight ThLEA proteins had complete ORFs that encoded deduced polypeptides of 114–584 amino acids with predicted molecular masses of 12.29–65.4 kDa and pIs of 4.75–9.6 (Table 2). Subcellular locations were predicted from protein sequence analysis using the targetP algorithm. The results suggested that ThLEA-3 may be located in the chloroplast, ThLEA-2 and -4 may be secreted proteins, and the locations of the other five ThLEA genes with full ORFs may be classified as “other.”

Table 2.

Characteristics of the 8 ThLEAs from T. hispida that had full ORFs.

| Gene name | Deduced number of amino acids | MW (kDa) | pI | Predicted subcellular localization∗ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ThLEA-1 | 584 | 65.40 | 8.18 | Other |

| ThLEA-2 | 435 | 46.70 | 8.67 | Secreted |

| ThLEA-3 | 462 | 51.31 | 8.02 | Chloroplast |

| ThLEA-4 | 212 | 23.55 | 9.60 | Secreted |

| ThLEA-5 | 114 | 12.29 | 5.54 | Other |

| ThLEA-6 | 151 | 16.31 | 4.97 | Other |

| ThLEA-7 | 318 | 35.31 | 4.75 | Other |

| ThLEA-8 | 171 | 17.49 | 8.02 | Other |

*Subcellular localization was predicted from protein sequence analysis using the targetP algorithm.

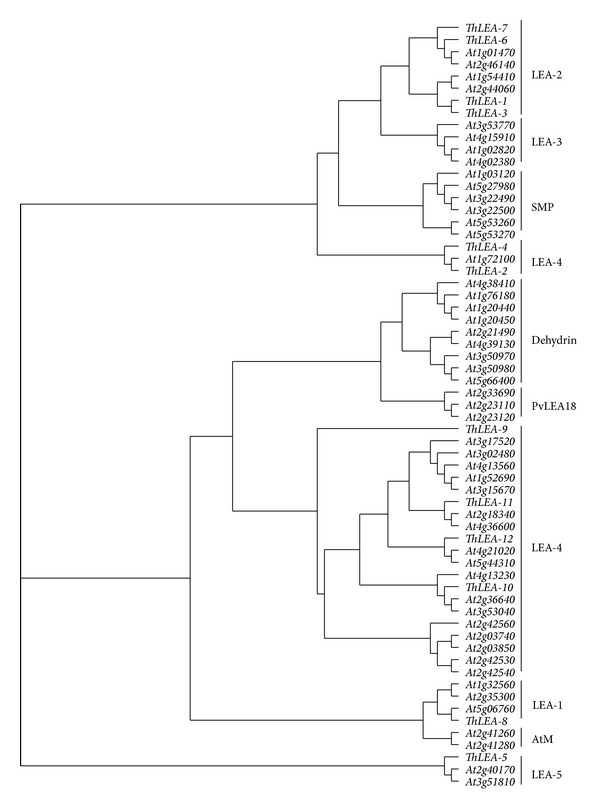

Hunault and Jaspard [9] identified 51 LEA protein encoding genes in Arabidopsis genome and classified them into nine distinct groups (LEA-1, -2, -3, -4, -5, Atm, SMP, dehydrin, and PvLEA18). According to this classification, the phylogenetic relationships showed that ThLEA-1, -3, -6, and -7 are in the LEA-2 group and ThLEA-2, -4, -9, -10, -11, and -12 are in the LEA-1 group, while ThLEA-8 and -5 are in the Atm and LEA-5 groups, respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree of the 12 ThLEAs and 51 Arabidopsis LEAs based on sequence alignments of the predicted proteins. All the 12 ThLEA proteins from T. hispida and 51 Arabidopsis LEA proteins were subjected to phylogenetic analysis by constructing a phylogenetic tree by the neighbor-joining (NJ) method in ClustalX. According to the classification of Hunault and Jaspard [9], the LEA proteins were classified into nine groups.

3.2. Relative Transcript Abundances of ThLEAs under Normal Growth Conditions

In order to study the tissue specificity of ThLEA gene expression, the relative transcript abundances of the ThLEA genes in T. hispida roots, stems, leaves, and seeds under normal growth conditions were monitored by real-time RT-PCR. The transcript level of the actin gene was assigned as 100, while the transcript levels of ThLEA genes were plotted relative to transcript level of actin gene (Table 3). The results indicated that ThLEA-4 is the gene with the highest expression in stems and leaves and in the roots only ThLEA-10 had greater expression, while the transcript levels of ThLEA-5 and -6 were very low in all four tissues (roots, stems, leaves, and seeds). The expressions of ThLEA-8 and -12 were very high in seeds while those were very low in the other three tissues. In the roots, the transcript level of ThLEA-6 was lowest and only 0.1 (equivalent to 1/1000 of actin). Meanwhile, in stems and leaves, the transcript level of ThLEA-12 was lowest and less than 1/1000 of actin. Moreover, the transcript level of the ThLEA genes highly differed among each other and also strongly differed among the four tissues. For instance, ThLEA-10, -11, and -12 were expressed mainly in the roots and seeds, and their transcript levels were all exceeded 1220-fold in the seeds. ThLEA-2 and -9 were expressed mainly in the stems and seeds, while ThLEA-1, -3, and -7 showed relatively high transcript level in the leaves.

Table 3.

Relative transcript abundance of the 12 ThLEAs in different tissues of T. hispida. The transcript levels of the 12 ThLEA genes were plotted relative to expression of the actin gene. Transcript levels of the actin gene in roots, stems, leaves, and seeds were all assigned as 100.

| Gene | Relative abundance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roots | Stems | Leaves | Seeds | |

| ThLEA-1 | 6.8 | 11.6 | 36.2 | 10 |

| ThLEA-2 | 5.3 | 26.4 | 12.1 | 230 |

| ThLEA-3 | 8.2 | 23.2 | 64.8 | 4 |

| ThLEA-4 | 188.1 | 365.6 | 355.5 | 161 |

| ThLEA-5 | 1.5 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 20 |

| ThLEA-6 | 0.1 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 3 |

| ThLEA-7 | 0.8 | 19.5 | 27.9 | 10 |

| ThLEA-8 | 8.5 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 770 |

| ThLEA-9 | 17.7 | 61.7 | 26.2 | 180 |

| ThLEA-10 | 198.3 | 2.0 | 5.1 | 1240 |

| ThLEA-11 | 161.8 | 4.1 | 23.7 | 6050 |

| ThLEA-12 | 9.9 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1220 |

3.3. The Expression Profiles of ThLEAs in Response to NaCl, PEG, and ABA Treatments

3.3.1. NaCl Stress

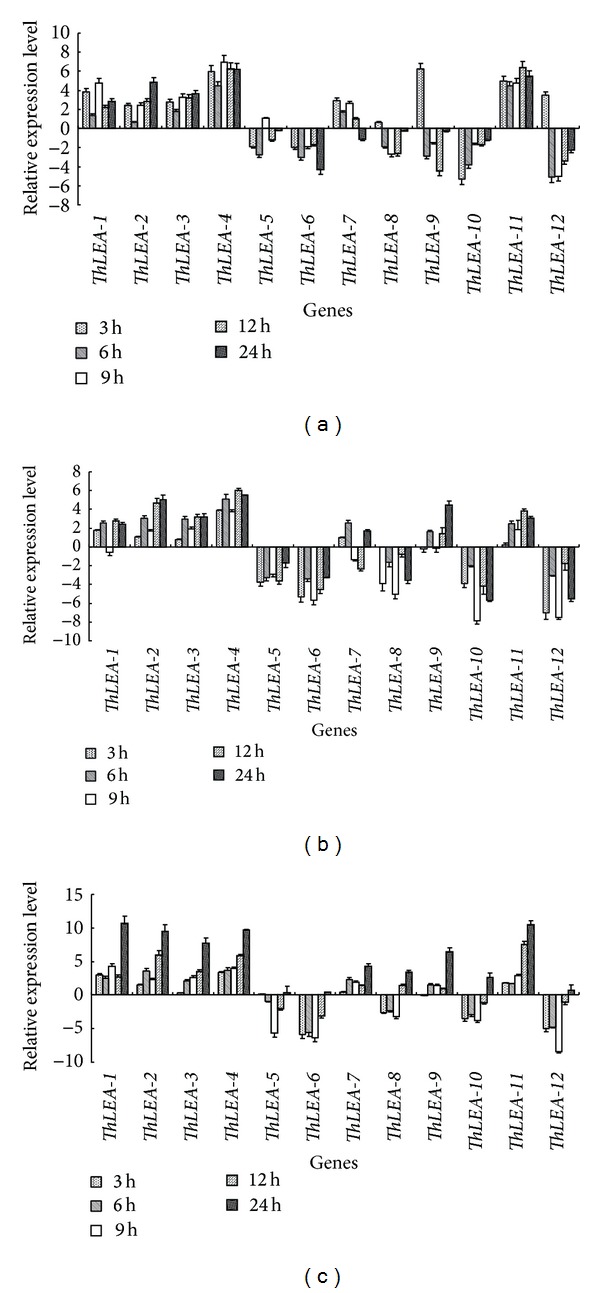

The transcript patterns of all of the ThLEA genes were quite similar among the roots, stems, and leaves under NaCl stress. Furthermore, ThLEA-2, -3, -4, and -11 were induced (>2-fold) during NaCl stress period. ThLEA-7 was also upregulated during most treatment period, and six ThLEA genes reached their peak expression level in the leaves at 24 h of stress. The most highly induced gene was ThLEA-1, which was induced 1596-fold. However, ThLEA-5, -6, -8, -10, or -12 were highly downregulated at almost each stress time point. Except for ThLEA-5, the other four downregulated genes reached lowest transcript levels at 9 h in stems and leaves. Interestingly, distinct from these genes, the transcript pattern of ThLEA-9 was different among the three tissues. In the roots, it was induced at 3 h but downregulated at the other time points, while in stems and leaves it was mainly upregulated. Similar with the other upregulated ThLEAs, ThLEA-9 reached greatest expression at 24 h in the leaves (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Expression analysis of the 12 ThLEAs in response to 0.4 M NaCl stress. Relative expression level = transcription level under stress treatment/transcription level under control conditions. All relative expression levels were log2 transformed and error bars (SD) were obtained from multiple replicates of the real-time RT-PCR. (a), (b), (c): expression of ThLEAs in roots, stems, and leaves, respectively.

3.3.2. PEG Stress

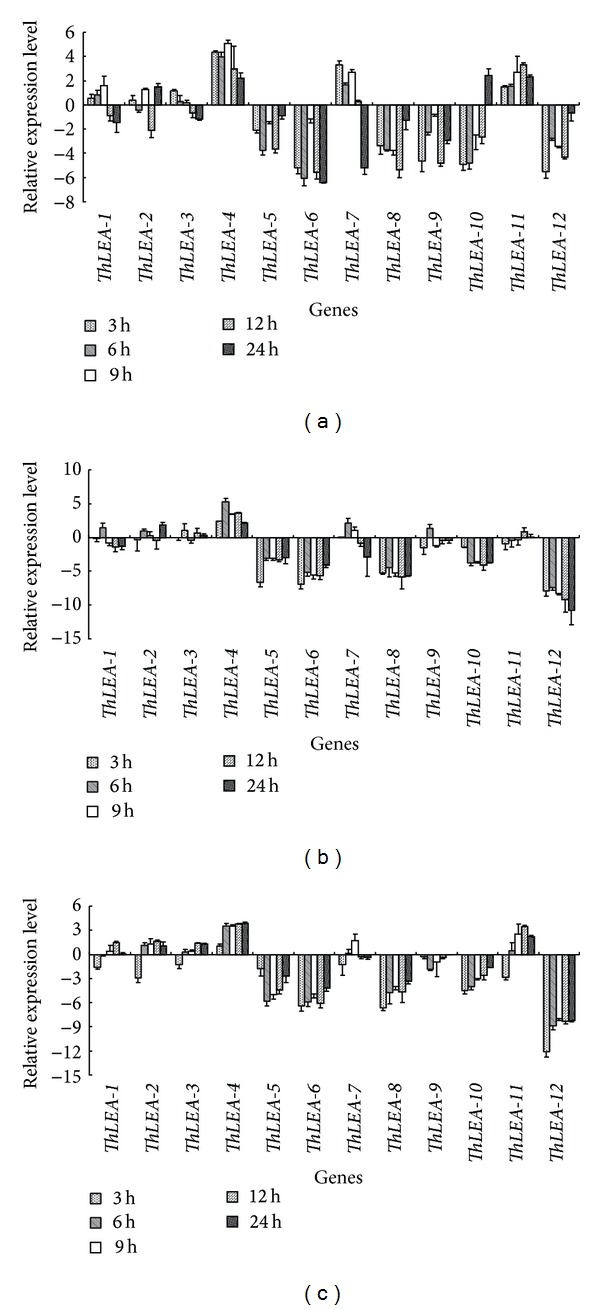

Consistent with NaCl stress, the transcript patterns of these ThLEA genes under PEG stress were divided into two distinct groups (Figure 3). One group was composed of ThLEA-1, -2, -3, -4, and -11, and these genes were mainly upregulated. The second group included ThLEA-5, -6, -8, -9, -10, and -12 that were largely downregulated during the PEG treatment period.

Figure 3.

Expression analysis of the 12 ThLEAs in response to 20% PEG6000 stress. Relative expression level = transcript level under stress treatment/transcript level under control conditions. All relative expression levels were log2 transformed and error bars (SD) were obtained from multiple replicates of the real-time RT-PCR. (a), (b), (c): expression of ThLEAs in roots, stems, and leaves, respectively.

3.3.3. ABA Treatment

After application of exogenous ABA, ThLEA-1, -2, and -3 were only slightly differentially regulated in the roots, stems, and leaves, indicating that they may be regulated via the ABA-independent signaling pathway. However, the genes that were downregulated by PEG and/or NaCl stress were also highly downregulated by ABA treatment. In contrast, ThLEA-4, -7, and -11 were mainly upregulated, especially ThLEA-4, whose transcript levels in the stem at 6 h were increased by 38-fold compared with the control (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Expression analysis of the 12 ThLEAs in response to 100 μM ABA treatment. Relative expression level = transcript level under stress treatment/transcript level under control conditions. All relative expression levels were log2 transformed and error bars (SD) were obtained from multiple replicates of the real-time RT-PCR. (a), (b), (c): expression of ThLEAs in roots, stems, and leaves, respectively.

4. Discussion

In the present study, 12 ThLEA genes were identified from Tamarix RNA-seq data base, and the transcript abundance of each gene was assessed in normal growth conditions by real-time RT-PCR. Furthermore, NaCl and PEG were used to simulate salinity and drought conditions, respectively, and the expression levels of the ThLEA genes were investigated in roots, stems, and leaves in response to these stress environments.

Many studies have shown that members of the plant LEA family displayed tissue-specific expression and are involved in various processes in plant growth and development. For example, in Arabidopsis, 22 of the 51 LEA genes (43%) showed high expression levels (relative expression >10) in the nonseed organs in the absence of a stress or hormone treatment [27]. The OsLEA3-2 gene is not expressed in vegetative tissues under normal conditions and it is thought to play an important role in the maturation of the embryo [10]. Moreover, the transcripts of MsLEA3-1 were strongly enriched in leaves compared with roots and stems of mature alfalfa plants [20]. Expression profiles of the 12 ThLEA genes in different tissues of T. hispida were determined under normal growth conditions and this showed that most of the ThLEAs were expressed in various organs and tissues. However, they displayed different expression levels between the different tissue types and this may reflect the complexity of functions performed by this gene family [28]. Among the 12 ThLEAs, ThLEA-10, -11, and -12 were mainly expressed in the roots, suggesting that these genes may play roles in root stress response. ThLEA-2 and -9 were highly expressed in the stem, while ThLEA-1, -3, and -7 may play important roles in the leaves as these genes are highly and specifically expressed in leaves. Moreover, ThLEA-4 has very high expression level in the roots, stems, and leaves, suggesting that it might play important roles in all of these tissues. The expression levels of ThLEA-5, -6, -8, and -12 were very low in each of the tissues examined, indicating that these genes may play a relatively unimportant role in these tissues under normal growth conditions.

There is increasing evidence suggesting that LEA genes are associated with abiotic stress tolerance, particularly in plant responses to dehydration, salt, and cold stresses [18, 29]. In Arabidopsis, of the 22 genes highly expressed in nonseed tissues, 12 were induced by more than 3-fold in response to cold, drought, and salt stresses [27]. In sweet potato plants, IbLEA14 expression was strongly induced by dehydration and NaCl [30]. In the present study, half of the 12 ThLEA genes (ThLEA-1, -2, -3, -4, -7, and -11) were induced under salt and drought stress, indicating that these genes might play important roles in response to salt and drought stresses in T. hispida. Bies-Ethève et al. [31] reported that LEA genes from the same group do not show identical expression profiles and regulation of LEA genes that show apparently similar expression patterns does not systematically involve the same regulatory pathway. Consistent with this, the six upregulated ThLEAs in T. hispida belong to two LEAs groups (LEA-2 and LEA-4), while LEAs in the same group (such as LEA-4) showed completely different expression patterns.

There are ABA-dependent and ABA-independent regulatory networks controlling plant responses to abiotic stresses. LEA genes are often considered as being ABA-regulated and previous studies have shown that some ThLEA genes can be induced by exogenous ABA [10, 30]. However, our study shows that some ThLEA genes, including ThLEA-1, -2, and -3, were highly induced by abiotic stresses but were not regulated by ABA. Consistent with this, Bies-Ethève et al. [31] reported that most of the LEA genes in Arabidopsis seedlings show no response at all following exogenous ABA treatment. Hundertmark and Hincha [27] deduced the presence of different signal transduction pathways in different Arabidopsis tissues (vegetative plants and seeds) by comparing the expression of LEA genes after ABA treatment. In contrast, we found that expression patterns were highly similar in the three tissues examined after ABA treatment. Expression analyses showed that nine ThLEA genes in three tissues of T. hispida were upregulated or downregulated by ABA, which suggests that these ThLEA genes are regulated by ABA-dependent stress resistance pathways. These findings demonstrate that the ThLEA genes involved in salt and drought stress resistance in T. hispida are probably regulated by two different pathways (ABA-dependent and ABA-independent). Further studies are required to elucidate the functions of the ThLEAs in response to the abiotic stress and to fully characterize the signaling pathways that regulate their expression.

5. Conclusion

In summary, we identified 12 ThLEA genes from T. hispida, which belong to three groups. The LEA-1 group includes ThLEA-2, -4, -9, -10, -11, and -12 proteins, the LEA-2 group contains ThLEA-1, ThLEA-3, ThLEA-6, and ThLEA-7, and ThLEA-8 and -5 are in the Atm and LEA-5 groups. The ThLEA genes displayed tissue-specific expression patterns under normal growth conditions. ThLEA-10, -11, and -12 were expressed mainly in the roots and seeds. ThLEA-2 and -9 were preferentially expressed in the stems and seeds, while ThLEA-1, -3, and -7 showed high transcript level in the leaves. Furthermore, real-time RT-PCR analysis showed that the ThLEA genes were regulated by salt and drought stresses. ThLEA-1, -2, -3, -4, -7, and -11 were mainly induced by salt and drought stress. But ThLEA-5, -6, -8, -9, -10, and -12 were largely downregulated during the NaCl and PEG treatment. After the application of exogenous ABA, the expression levels of all ThLEA genes (except for the ThLEA-1, -2, and -3) were obviously different under the ABA treatment. Our studies will contribute to a better understanding of the functions of ThLEA genes involved in stress response in T. hispida.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Key Laboratory of Forest Genetics & Biotechnology (Nanjing Forestry University), Ministry of Education (FGB200902), and The Program for Young Top-Notch Talents of Northeast Forestry University (PYTT-1213-09).

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

Authors' Contribution

Caiqiu Gao and Yali Liu have the same contribution to this paper.

References

- 1.Shao HB, Chu LY, Shao MA, Jaleel CA, Hong-mei M. Higher plant antioxidants and redox signaling under environmental stresses. Comptes Rendus—Biologies. 2008;331(6):433–441. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shao H, Chu L, Jaleel CA, Zhao C. Water-deficit stress-induced anatomical changes in higher plants. Comptes Rendus—Biologies. 2008;331(3):215–225. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ni FT, Chu LY, Shao HB, Liu ZH. Gene expression and regulation of higher plants under soil water stress. Current Genomics. 2009;10(4):269–280. doi: 10.2174/138920209788488535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shao H, Chu L, Jaleel CA, Manivannan P, Panneerselvam R, Shao M. Understanding water deficit stress-induced changes in the basic metabolism of higher plants-biotechnologically and sustainably improving agriculture and the ecoenvironment in arid regions of the globe. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology. 2009;29(2):131–151. doi: 10.1080/07388550902869792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cao H, Zhang Z, Xu P, et al. Mutual physiological genetic mechanism of plant high water use efficiency and nutrition use efficiency. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces. 2007;57(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2006.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mazzucotelli E, Mastrangelo AM, Crosatti C, Guerra D, Stanca AM, Cattivelli L. Abiotic stress response in plants: When post-transcriptional and post-translational regulations control transcription. Plant Science. 2008;174(4):420–431. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nezhadahmadi A, Prodhan ZH, Faruq G. Drought tolerance in wheat. The Scientific World Journal. 2013;2013:12 pages. doi: 10.1155/2013/610721.610721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dure L, III, Greenway SC, Galau GA. Developmental biochemistry of cottonseed embryogenesis and germination: changing messenger ribonucleic acid populations as shown by in vitro and in vivo protein synthesis. Biochemistry. 1981;20(14):4162–4168. doi: 10.1021/bi00517a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hunault G, Jaspard E. LEAPdb: a database for the late embryogenesis abundant proteins. BMC Genomics. 2010;11(1, article 221) doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duan J, Cai W. OsLEA3-2, an abiotic stress induced gene of rice plays a key role in salt and drought tolerance. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045117.e45117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Y, Li Y, Lai J, et al. Ectopic expression of a LEA protein gene TsLEA1 from Thellungiella salsuginea confers salt-tolerance in yeast and Arabidopsis. Molecular Biology Reports. 2012;39(4):4627–4633. doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-1254-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olvera-Carrillo Y, Campos F, Reyes JL, Garciarrubio A, Covarrubias AA. Functional analysis of the group 4 late embryogenesis abundant proteins reveals their relevance in the adaptive response during water deficit in arabidopsis. Plant Physiology. 2010;154(1):373–390. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.158964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cui S, Hu J, Guo S, et al. Proteome analysis of Physcomitrella patens exposed to progressive dehydration and rehydration. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2012;63(2):711–726. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naot D, Ben-Hayyim G, Eshdat Y, Holland D. Drought, heat and salt stress induce the expression of a citrus homologue of an atypical late-embryogenesis of Lea5 gene. Plant Molecular Biology. 1995;27(3):619–622. doi: 10.1007/BF00019327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ukaji N, Kuwabara C, Takezawa D, Arakawa K, Fujikawa S. Cold acclimation-induced WAP27 localized in endoplasmic reticulum in cortical parenchyma cells of mulberry tree was homologous to group 3 late-embryogenesis abundant proteins. Plant Physiology. 2001;126(4):1588–1597. doi: 10.1104/pp.126.4.1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.NDong C, Danyluk J, Wilson KE, Pocock T, Huner NPA, Sarhan F. Cold-regulated cereal chloroplast late embryogenesis abundant-like proteins. Molecular characterization and functional analyses. Plant Physiology. 2002;129(3):1368–1381. doi: 10.1104/pp.001925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zegzouti H, Jones B, Marty C, et al. ER5, a tomato cDNA encoding an ethylene-responsive LEA-like protein: characterization and expression in response to drought, ABA and wounding. Plant Molecular Biology. 1997;35(6):847–854. doi: 10.1023/a:1005860302313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dalal M, Tayal D, Chinnusamy V, Bansal KC. Abiotic stress and ABA-inducible Group 4 LEA from Brassica napus plays a key role in salt and drought tolerance. Journal of Biotechnology. 2009;139(2):137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.RoyChoudhury A, Roy C, Sengupta DN. Transgenic tobacco plants overexpressing the heterologous lea gene Rab16A from rice during high salt and water deficit display enhanced tolerance to salinity stress. Plant Cell Reports. 2007;26(10):1839–1859. doi: 10.1007/s00299-007-0371-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bai Y, Yang Q, Kang J, Sun Y, Gruber M, Chao Y. Isolation and functional characterization of a Medicago sativa L. gene, MsLEA3-1. Molecular Biology Reports. 2012;39(3):2883–2892. doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-1048-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park BJ, Liu Z, Kanno A, Kameya T. Increased tolerance to salt- and water-deficit stress in transgenic lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) by constitutive expression of LEA. Plant Growth Regulation. 2005;45(2):165–171. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao X, Zhan L, Zou X. Improvement of cold tolerance of the half-high bush Northland blueberry by transformation with the LEA gene from Tamarix androssowii . Plant Growth Regulation. 2011;63(1):13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao P, Liu F, Ma M, et al. Overexpression of AtLEA3-3 confers resistance to cold stress in Escherichia coli and provides enhanced osmotic stress tolerance and ABA sensitivity in Arabidopsis thaliana. Molekuliarnaia Biologiia. 2011;45(5):851–862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang C, Gao C, Wang L, Zheng L, Yang C, Wang Y. Comprehensive transcriptional profiling of NaHCO3-stressed Tamarix hispida roots reveals networks of responsive genes. Plant Molecular Biology. 2014;84(1-2):145–157. doi: 10.1007/s11103-013-0124-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang L, Wang C, Wang D, Wang Y. Molecular characterization and transcript profiling of NAC genes in response to abiotic stress in Tamarix hispida . Tree Genetics & Genomes. 2014;10:157–171. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hundertmark M, Hincha DK. LEA (Late Embryogenesis Abundant) proteins and their encoding genes in Arabidopsis thaliana . BMC Genomics. 2008;9, article 118 doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paponov IA, Paponov M, Teale W, et al. Comprehensive transcriptome analysis of auxin responses in Arabidopsis. Molecular Plant. 2008;1(2):321–337. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssm021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boudet J, Buitink J, Hoekstra FA, et al. Comparative analysis of the heat stable proteome of radicles of Medicago truncatula seeds during germination identifies late embryogenesis abundant proteins associated with desiccation tolerance. Plant Physiology. 2006;140(4):1418–1436. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.074039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park S, Kim Y, Jeong JC, et al. Sweetpotato late embryogenesis abundant 14 (IbLEA14) gene influences lignification and increases osmotic- and salt stress-tolerance of transgenic calli. Planta. 2011;233(3):621–634. doi: 10.1007/s00425-010-1326-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bies-Ethève N, Gaubier-Comella P, Debures A, et al. Inventory, evolution and expression profiling diversity of the LEA (late embryogenesis abundant) protein gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana . Plant Molecular Biology. 2008;67(1-2):107–124. doi: 10.1007/s11103-008-9304-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]