Abstract

To better understand methamphetamine (MA) use patterns and the process of recovery, qualitative interviews were conducted with adult MA users (n=20), comparing a sample that received substance abuse treatment with those who had not received treatment. Respondents provided detailed information on why and how they changed from use to abstinence, and factors they considered to be barriers to abstinence. Audio recordings and transcripts were reviewed for common themes. Participants reported a range of mild/moderate to intensely destructive problems, including loss of important relationships and profound changes to who they felt they were at their core, e.g., “I didn’t realize how dark and mean I was... I was like a different person.” Initial abstinence was often facilitated by multiple external forces (e.g., drug testing, child custody issues, prison, relocation), but sustained abstinence was attributed to shifts in thinking and salient realizations about using. The treatment group reported using more and different resources to maintain their abstinence than the no treatment group. Findings indicate individualized interventions and multiple, simultaneous approaches and resources were essential in reaching stable abstinence. Understanding long-term users’ experiences with MA use, addiction and abstinence can inform strategies for engaging and sustaining MA users in treatment and recovery.

Keywords: Methamphetamine, abstinence, relapse, recovery, qualitative analysis

Research on addiction recovery indicates there are multiple pathways to achieving sustained abstinence, with influences varying across individuals, substances and contexts; and although drug treatment may be an important contributing factor, it represents only one of the paths to recovery (German et al. 2006; Laudet,Savage & Mahmood 2002). Klingemann (2012) suggests recovery from alcohol dependence appears over time as an interplay between individual actions, societal reactions and positive and negative life events, while subjective accounts of recovery maintenance are being continuously constructed and reconstructed. Klingemann further argues that individuals implement a wide range of recovery maintenance strategies, including experiencing a new quality of social relationships and pursuing meaningful activities, with the change process contingent upon the subjective weighing of specific maintenance factors and the importance attributed to their interplay.

In a study by Best et al. (2008), reasons for initiating drug abstinence among heroin users included “being tired of the lifestyle” and personal health or psychological crises, however, factors associated with sustained recovery were primarily social. Similarly, a study of users of heroin and cocaine indicates social support and having ties to employed persons were related to reduced drug use (Williams & Latkin 2007). Although, social support did not protect against having strong drug network influences, suggesting interventions need to focus both on strengthening social support and disassociating from drug-using ties.

According to Teruya & Hser (2010), “Turning point,” a key concept in the life course approach, emphasizes the long-term developmental patterns of continuity and change in relation to transitions in social roles (e.g., parent, employee, drug offender) over the life span, and may be particularly beneficial in the study of changes in drug use behaviors. This approach takes into account multiple factors contributing toward abstinence, persistence, or relapse. The life course approach often begins with a particular event, experience, or awareness that results in changes in the direction of a pathway or trajectory over the long-term. Similarly, awareness of life purpose, defined as the subjective reason for a person’s existence derived from their beliefs and values used to produce and manage life goals (Lyons, Deane & Kelly 2010), and commitment to abstinence are motivational constructs that predict reductions in drug and alcohol use; Laudet, Savage & Mahmood (2002) have proposed that these mechanisms underlie recovery. Spiritual/religious orientation and change, forgiveness of self, and self-help participation also have been reported to be important aspects of recovery and play a significant role in the restoration of health (Robinson et al. 2011; Galanter et al. 2007). Accordingly, Laudet, Savage & Mahmood (2002) describe the complex nature of these motivational constructs of recovery as the product of relationships among internal and external circumstances. As improvements begin to occur in key areas of functioning, the individual may come to see that abstinence has benefits, and abstinence is required for these benefits to endure and accrue.

Related to methamphetamine (MA), a study involving Filipino American MA users suggests individuals become involved in social networks that facilitate their use, and recovery occurs when users change their social networks and stop using drugs as a means of coping with social class disadvantages. The realization that their networks have enabled and reinforced their drug usage serves as a major turning point in helping them ‘‘break free’’ from the social ties that foster continued use (Laus 2012). Other factors, including users’ perceptions of the functionality of MA may also provide an important key to understanding reasons for its use (Lende et al. 2007). In a study of 48 MA users in Thailand, all were introduced to MA by people close to them and reported trying it for reasons including curiosity, a way to lose weight, to enhance work, and to “forget life’s problems” (Sherman et al. 2008).

Motivations for using MA among HIV positive men who have sex with men centered around sexual enhancement and self-medication of negative affect associated with being HIV positive, including social rejection, negative self-perceptions and fear of dying (Semple, Patterson & Grant 2002). Among suburban adults who used MA, a qualitative study indicates use is often initiated and continued for functional purposes, and continued dysfunctional use was related to coping with the stress of loss of work, broken relationships, and other stressors of a suburban lifestyle. The pressure of keeping the family and home up to the standard expected in suburban neighborhoods appeared to be particularly stressful for young people who were just starting families in a difficult economic environment (Boeri, Harbry & Gibson, 2009).

To better understand MA use patterns and the process of recovery, this study explored factors that may facilitate or impede abstinence, from the perspectives of adults with long histories of primary MA use. These factors may vary between populations treated and untreated for substance abuse; consequently, the study examines MA users who had and had not received formal substance abuse treatment at the time of study enrollment. The qualitative interviews included questions on both facilitators of, and barriers to abstinence. However, respondents were encouraged to spontaneously focus their discussions on related issues and concerns that were most salient to them. As a result, much of the data from these interviews center around facilitators, as respondents discussed these topics in greater detail, describing diverse experiences and motivations to explain why and how they were able to initiate and maintain abstinence.

Methods

Participants

Qualitative interviews were conducted with a subset (n=20) of individuals who participated in a long-term follow up study of MA use; these 20 participants had at least six months of consecutive abstinence from MA use at some point between their baseline and eight-year follow-up interview. In earlier phases of the study, two samples of adult MA users were recruited: (1) a sample who received treatment for MA abuse (n=351), and (2) a sample who had not participated in formal substance abuse treatment (n=298). The treated sample was recruited from a stratified random sample of 1995–1997 treatment admission records in Los Angeles County and first interviewed in 1999–2001. Description of the treated sample and study procedures can be found in Brecht et al. (2004). In 2001–04, follow-up interviews were conducted with the treated sample, and the not treated sample was recruited and interviewed. The not-treated sample was recruited using community approaches including an acquaintance sampling approach, key informants, and extensive outreach in a range of Los Angeles county community venues to achieve socio-demographic and MA use behavior diversity.

In 2009–12, eight-year follow-up interviews were conducted with the treated and not treated samples. Natural History Interviews (McGlothlin, Anglin & Wilson 1977; Murphy et al. 2010) were conducted at baseline and follow-up, assessing a comprehensive array of sociodemographic, criminal, and physical and mental health characteristics; in addition, detailed life-course data on substance use and treatment were collected using a timeline follow-back approach with recall anchored by subjects’ critical life events. A total of 460 of the 649 respondents who completed the baseline interview also completed the eight-year follow up interview. Overall 87% of participants were located, and 76% of surviving participants completed the eight-year follow up.

In order to identify a diverse range of participant experiences for this qualitative analysis in the present study, a targeted sampling strategy was used to select a subset of respondents from those who completed the eight-year follow-up interview. The sample examined in this analysis (n=20) was 65% male; 35% African American, 35% White, 25% Hispanic and 5% multi-ethnic; the average age was 46.2 (SD=9.5); 45% received treatment and 55% had not received treatment prior to initial study recruitment. On average, participants had 12.2 (SD=8.7) cumulative lifetime years of MA use (i.e., years of use were not necessarily uninterrupted). At the eight year follow-up interview, they had an average of 7.0 (SD=6.7) years of uninterrupted MA abstinence; 35% (n=7) had 0 to 2 years of abstinence (shorter-term abstinence), and 65% (n=13) had four or more years of abstinence (long-term abstinence); 3 participants had used MA in the past month, 2 had used in the past year and the remaining 15 had been continuously abstinent for more than one year. In order to select respondents able to discuss facilitators of MA abstinence, selection criteria included at least six months of continuous MA abstinence at any time between their baseline and eight-year follow up interviews.

Data collection

Face-to-face individual qualitative interviews were conducted at or after the eight-year follow up interview in July 2012 through November of 2012. Respondents provided detailed information on why and how they changed from MA use to abstinence and factors that facilitated abstinence and factors that they considered to be barriers to abstinence. Interviews lasted approximately 30 minutes and were digitally recorded and professionally transcribed. Interview questions were open-ended, for example, “What made you realize you wanted to stop using MA?” and “What made it hard to stop?” Respondents were first asked to describe what was going on in their lives around the time they stopped using MA. In an effort to encourage respondents to spontaneously discuss topics that were most salient to them, the interviewer maintained the focus of the interview on the barriers and facilitators mentioned by the respondent. Interviewers used follow-up questions and probes to explore the topics that emerged during the course of the interviews. Respondents were paid $40 for their participation, and most were interviewed by the same trained interviewer who conducted their eight-year follow-up interview. The Institutional Review Board at the University of California, Los Angeles approved study procedures.

Analysis

Two researchers listened to each interview recording multiple times, took notes, and read and re-read the transcripts to identify major themes, commonalities, and differences that emerged directly from the data. Line-by-line reviews of the transcripts and notes were conducted to identify first-level codes for descriptors of important themes pertaining to facilitators of, and barriers to MA abstinence. Data corresponding to each first-level code were reviewed, and sub-codes were established to divide the first-level codes into more specific categories. The results correspond to the emergent categories. Interviewers asked follow-up questions during the interviews when any inconsistencies or confusion arose in respondents’ narratives until issues were clarified. During the coding process, discrepancies in coding categories were discussed by the researchers until agreement was achieved.

To assess prevalence of identical or comparable responses, percentages of respondents mentioning each theme are presented in the findings. To examine whether treatment status may be related to abstinence facilitators and barriers, codes are presented overall and for those who did and did not receive treatment prior to study recruitment. This approach allowed the key themes to emerge directly from the respondents’ experiences and shows the prevalence and variability of themes across respondents and across treatment status. The average number of facilitators and barriers per respondent was calculated for the sample overall and by treatment status. Direct quotations drawn from the transcripts explicate each theme.

Results

Overall, a range of experiences with MA was reported, from mild/moderate problems to intensely destructive, including loss of important relationships and profound changes to who respondents felt they were at their core, e.g., “I didn’t realize how dark and mean I was… I was like a different person” (African American man, age 48, treatment). Serious problems occurring shortly before initiating abstinence from MA use were commonly reported (e.g., homelessness, criminal involvement, intolerable anxiety, paranoia, hallucinations). On the other hand, some respondents also described memories of the fun, camaraderie and good times they had while using MA. For example, a respondent reported, “… there’s a euphoria that comes with it, and a very devil-may-care attitude about it. Sometimes I have missed the carefreeness of it… I’m not gonna lie… you hear me say, ‘Oh, that was misery,’ but there was a lot of pleasure in it too” (Mexican-American man, age 55, treatment).

Facilitators of MA Abstinence

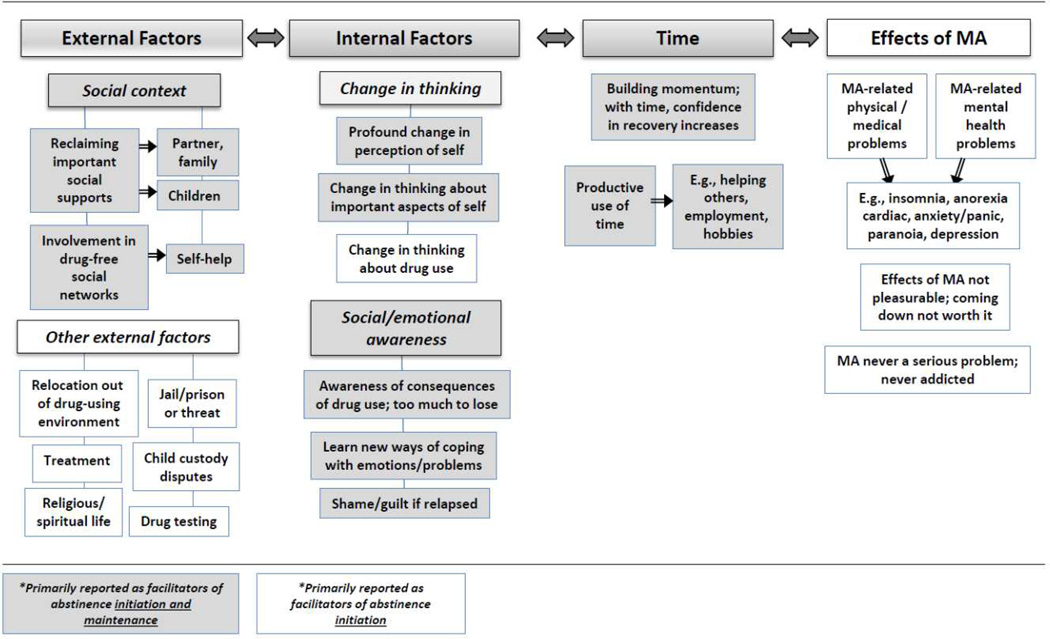

Figure 1 maps coded responses of facilitators of abstinence to four major themes and several sub-themes, and identifies which themes and sub-themes were primarily reported as facilitators of abstinence initiation only, and which were facilitators of both abstinence initiation and maintenance.

Figure 1.

Interrelated themes identified as facilitators of initiating and maintaining MA abstinence

External factors

Many participants reported initial abstinence was facilitated by multiple external forces (e.g., frequent drug testing, threat of loss of children, prison, relocation). Several of these themes were reported by half or more of the sample, including pressure/concerns from family members, and treatment participation (see Table 1 for description and examples of themes, and Table 2 for counts and percentages of themes reported). Three of the 11 respondents who never received treatment prior to study recruitment had entered treatment since their baseline interview and reported that it helped to facilitate their MA abstinence. Thus, half of the total sample (n=10) reported treatment facilitated abstinence. Two respondents in the treatment sample did not report treatment facilitated their abstinence. Concerns and pressure from family members was the most commonly reported theme among respondents with short-term abstinence (71%, n=5). Similarly, 57% (n=4) of those with short-term abstinence reported external pressures (e.g., prison) prompted their abstinence: “My last prison run was just the end of it. I couldn’t take it anymore… there was some life-threatening things that happened during my last term in prison. I just couldn’t do it anymore (White man, age 48, Treatment).

Table 1.

Themes and example quotes of facilitators of methamphetamine (MA) abstinence

|

Table 2.

Facilitators of methamphetamine (MA) abstinence by treatment status*

| Facilitator, n (%) | No treatment (N=11) |

Treatment (N=9) |

Total (N=20) |

|---|---|---|---|

| External factors: | |||

| Social context: | |||

| Concerns about their children | 4 (36%) | 3 (33%) | 7 (35%) |

| Concerns/pressure from other family members and/or partner | 7 (64%) | 6 (67%) | 13 (65%) |

| Self-help, AA, NA participation | 1 (9%) | 6 (67%) | 7 (35%) |

| Non-drug-using social network (other than self-help) | 3 (27%) | 5 (56%) | 8 (40%) |

| Other external facilitators: | |||

| Treatment | 3 (27%) | 7 (78%) | 10 (50%) |

| Church, spiritual connection, forgiveness, prayer | 4 (36%) | 4 (44%) | 8 (40%) |

| External pressures (mandatory drug tests, jail, threat of jail) | 5 (45%) | 6 (67%) | 11 (55%) |

| Relocation out of drug-using environment | 3 (27%) | 1 (11%) | 4 (20%) |

| Internal factors: | |||

| Shift in thinking: | |||

| About drug use | 2 (18%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (10%) |

| About priorities and/or important aspects of self | 3 (27%) | 4 (44%) | 7 (35%) |

| Profound change in perception of self | 2 (18%) | 3 (33%) | 5 (25%) |

| Social and emotional awareness: | |||

| Learned new ways of coping with emotions/problems | 1 (9%) | 6 (67%) | 7 (35%) |

| Awareness of consequences of drug use | 4 (36%) | 3 (33%) | 7 (35%) |

| Feelings of shame/guilt if resumed drug use | 0 (0%) | 3 (33%) | 3 (15%) |

| Time | |||

| Building momentum over time | 2 (18%) | 6 (67%) | 8 (40%) |

| Productive use of time overall | 8 (73%) | 7 (78%) | 15 (75%) |

| Specifically helping others with abstinence | 2 (18%) | 3 (33%) | 5 (25%) |

| Physical and psychological effects of MA | |||

| Physical health concerns | 4 (36%) | 4 (44%) | 8 (40%) |

| Mental health concerns | 5 (45%) | 4 (44%) | 9 (45%) |

| MA use was never serious problem/never felt addicted | 4 (36%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (20%) |

| MA was no longer pleasurable/was unpleasant | 3 (27%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (15%) |

| Physical effects of coming down from MA not worth it | 3 (27%) | 1 (11%) | 4 (20%) |

| Average (SD) number of facilitators reported: | 6.6 (1.9) | 9.1 (2.3) | 7.8 (3.3) |

The sample was regular MA users with 6 or more months of MA abstinence; 45% received treatment for primary MA use and 55% never received drug treatment at study intake.

Internal factors

Sustained abstinence was more often attributed to internal factors, such as a shift in thinking and greater awareness of the personal and interpersonal consequences of their drug use; e.g., an African American woman age 42 who attended treatment and with sustained abstinence indicated that her shift in thinking allowed her to accept help from others and to listen to her children express how her drug use affected them; she reported, “it’s a work in progress… getting my children’s trust back.”

Time

Likewise, time and building momentum (i.e., abstinence is facilitated by incremental successes over time) were important themes facilitating initiation and maintenance of MA abstinence; 85% (n=11) of those with 4 or more years of abstinence indicated this factor facilitated abstinence, e.g., a respondent described how his lifestyle has completely changed with long-term MA abstinence, “I go to the gym every day now, except the weekends. Since I moved back up here, we’ve been raising chickens, the garden, the crops… It’s a lot of work… but a lot less stressful (White man, age 31, No treatment).

Effects of MA

Almost half the sample overall (45%, n=9) reported mental health concerns prompted their MA abstinence; 62% (n=8) of those with long-term abstinence reported this was a facilitator (as did only one with short-term abstinence), e.g., a Mexican American woman (age 42, Treatment) reported, “I was probably losing my mind. I was mentally just deteriorating from the MA… major hallucinations, very, very depressed.”

Differences by treatment status

The treatment group (i.e., those who received treatment prior to recruitment) reported an average of 9.1 factors that facilitated their MA abstinence, whereas the no treatment (prior to study recruitment) group reported 6.6 facilitators. More respondents in the treatment group than the no treatment group reported facilitators including self help, having learned new ways of coping, building momentum and feelings of shame/guilt if relapsed. Conversely, more respondents in the no treatment group than the treatment group mentioned as facilitators that MA was never a serious problem and MA was no longer pleasurable.

Barriers to Abstinence

Table 3 shows percentages of themes related to barriers to MA abstinence for the sample overall and by treatment status at study enrollment. Barriers to abstinence showed considerable variation among individuals in this sample overall, and barriers for some appear to be facilitators for others.

Table 3.

Themes related to barriers to methamphetamine (MA) abstinence by treatment status

| Barrier to abstinence, n (%) | No treatment (N=11) |

Treatment (N=9) |

Total (N=20) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social context: | |||

| Friends or partner using | 5 (45%) | 3 (33%) | 8 (40%) |

| Partner/family “enabled” MA use (e.g., partner provided money, ignored drug use) | 2 (18%) | 3 (33%) | 5 (25%) |

| Resided in a drug-using environment | 4 (36%) | 1 (11%) | 5 (25%) |

| Physical and psychological effects of MA | |||

| “Self-medicated”/used MA to cope with feelings or stress | 5 (45%) | 6 (67%) | 11 (55%) |

| Wanted/needed energy (e.g., to work, clean house) | 4 (36%) | 1 (11%) | 5 (25%) |

| For fun (e.g., adventure, excitement, euphoria) | 9 (82%) | 4 (44%) | 13 (65%) |

| Craving/addiction | 4 (36%) | 7 (78%) | 11 (55%) |

| Coming down is so hard, so kept using | 1 (9%) | 1 (11%) | 2 (10%) |

| Shift in thinking about self and/or MA use: | |||

| Self-doubt, identity as a MA user (e.g., it’s what I know best) | 2 (18%) | 3 (33%) | 5 (25%) |

| Reality testing (e.g., this time it will be different) | 3 (27%) | 1 (11%) | 4 (20%) |

| Other barriers: | |||

| Alcohol use (loosens inhibitions) | 2 (18%) | 2 (22%) | 4 (20%) |

| Having money | 1 (9%) | 1 (11%) | 2 (10%) |

| Psychosocial problems prior to drug use | 1 (9%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (5%) |

| No longer involved with Dept of Family Services | 1 (9%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (5%) |

| Having more free time | 1 (9%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (5%) |

| Average (SD) number of barriers reported: | 4.1 (2.2) | 3.7 (2.1) | 3.9 (3.9) |

Social context

Some respondents reported the same general barrier/facilitator, but very different experiences, for example regarding living in a sober living home: “I was in some ridiculous sober living home that was horrible because they just took our GR money, and they didn’t mind if you got high” (African American man, age 41, No treatment). Another respondent described his experience in sober living, “…there wasn’t substance use allowed at all… and I took a ten-week course in property management, got my accreditation with that, and for the past eight-and-a-half years, I’ve been basically managing apartments, and got my life back on track” (White man, age 44, No treatment). While one respondent felt that attending self-help meetings was discouraging and “made me want to use,” another respondent reported self-help participation was critical to his recovery.

The impact of respondents’ drug-using social networks on ability to remain abstinent was mentioned by respondents in both the treatment and no treatment group. A woman in the treatment group described the difficulty of letting go of that network: “When you’re doing drugs, you have a group of people that you get loaded with, you associate with, you buy from, you hang around… You have a certain type of camaraderie with people that do the same thing you do. That’s just like a person that, say you’re on the running team, and you run because you like that rush you get from running. All of a sudden, you’re injured and you can’t run with this group of people anymore. You miss that camaraderie of you guys meeting up on a Saturday morning, running through the beach, and all of a sudden, you don’t have that anymore.”

Physical and psychological effects of MA

The most commonly reported themes related to barriers to MA abstinence were desire to use for fun, to self-medicate/cope with stressors, and craving/addiction. Among those with long-term abstinence, 69% reported barriers to abstinence were desire to use for fun (n=9) and craving/addiction (n=9). Among those with short-term abstinence, the most commonly reported barriers were desire to use for fun (57%, n=4) and to self-medicate/cope with stress (57%, n=4).

Shift in thinking about self and/or MA use

Likewise, respondents indicated that self-doubt and “putting myself down” perpetuated their use; however, another respondent reported that her use of MA was causing her to lose self-confidence and this realization prompted her to stop using MA.

Differences by treatment status

On average each respondent regardless of treatment status reported about 4 barriers. Nearly all (82%, n=9) of the no treatment group reported that a desire to use for fun was a barrier to abstinence, compared to less than half (44%, n=4) of the treatment group. In contrast, most of the treatment group (78%, n=7) reported craving/addiction was a barrier, compared to 36% (n=4) of the no treatment group. Other factors mentioned to a greater extent by the no treatment group were reality testing (e.g., “to see what would happen;” “to test the waters again”), for energy, and living in an environment with other drug users.

Discussion

Overall, our study findings are consistent with a study of alcohol and heroin users, indicating recovery experiences vary widely and are associated with supportive peer groups and more engagement in meaningful activities (Best et al. 2012). Similar to a study of alcohol dependence (Klingemann 2012), a wide range of recovery maintenance strategies was identified, and as reported by Mitchell et al. (2011), many respondents described their experience with abstinence and recovery as an accumulation of positive changes (i.e., “building momentum” and achieving incremental successes over time). Similar proportions of the treatment and no treatment samples endorsed specific themes as important facilitators of abstinence, including supportive social networks, productive use of time, physical and mental health concerns and external pressures. For both groups, initial abstinence was often facilitated by multiple external forces (e.g., drug testing, child custody issues, prison, relocation), but sustained abstinence was more frequently attributed to shifts in thinking and salient realizations about using.

Several interesting distinctions emerged between the respondents who received treatment and those who did not; for example more of the treated sample reported learning new ways of coping and building momentum as facilitators. In contrast, more respondents in the no treatment group mentioned as facilitators that MA was never a serious problem and MA was no longer pleasurable. These differences suggest some MA users who do not access treatment may use and abstain from MA for reasons they perceive to be less problematic than reasons reported by many of those who received treatment.

Regarding barriers to abstinence, there appeared to be similarities and differences between the treatment and no treatment groups. While each group reported approximately four specific barriers on average, the no treatment group reported a higher rate of using for fun, whereas the treatment group reported a higher rate of using due to craving/addiction. This may reflect a difference in actual or perceived severity of MA use between the two groups, with a greater proportion of the treatment group expressing what may be a more serious clinical problem (“craving/addiction” versus “having fun”). Regarding similarities, participants in both groups expressed involvement in a drug-using social network as a significant barrier to abstinence, and respondents poignantly described the difficulty of letting go of this network. Similarly, in a study of suburban adults, MA use was often predicated on camaraderie or identity-formation with drug-using groups composed of peers, family members or coworkers, and for the majority of MA users, the entire drug trajectory is intertwined with, and impacted by, sociality (Boshears, Boeri & Harbry 2011).

The importance of the use of peer support, self-help and sober social networks was also clearly emphasized as facilitating abstinence, predominantly by the treatment group. This resource may be of particular importance due to its association with greater self-determination and community affiliation, as indicated in a study by Boisvert et al. (2008). The study reports homeless drug users who participated in a peer-supported community program expressed these attributes, reaching out and supporting each other, and taking proactive steps to direct and influence their own recovery process. Similarly, participants in our study expressed how supporting others was an important component of their own recovery. Moreover, achieving recovery from MA appears to be, in many ways, a unique and personal experience for these individuals, many of whom expressed self-determination in lining up the resources they needed to maintain abstinence and continue the positive changes they had initiated.

Research has documented cases of individuals who have recovered from a variety of drug problems without treatment, e.g., ‘maturing out’ from drug use with the assumption of new life roles (Cunningham 2000). Although the majority of the no treatment sample remained without treatment during the eight-year follow up period, a subset of these individuals reported similar barriers to MA abstinence and utilized many of the same resources as the treatment sample to initiate and maintain their abstinence. Individuals who did not access treatment continued to rely on other important social, internal and external resources to facilitate their abstinence. Results reflecting our no treatment sample are consistent with a study of rural MA users who reported quitting or reducing their MA use due to health, legal, and/or family issues, and used strategies including willpower, self-isolation and staying busy; only 3 of 24 respondents quit or reduced their use as a result of utilizing drug treatment programs (Sexton et al. 2008).

Results of this study should be interpreted within several constraints. Data are self-reported and retrospective, and thus may be affected by respondents’ ability to remember and accurately report information. However, as a component of the parent study, respondents had recently completed the Natural History Interview, a type of timeline follow-back approach with recall anchored by subjects’ critical life events (Murphy et al. 2010); interviewers utilized this timeline to facilitate recall during the qualitative interview. The study sample was primarily drawn from Los Angeles County, California. Therefore, findings may not apply to MA users in other geographical locations. The open-ended format of the study may have resulted in greater contributions to the dataset from respondents who were more expressive and motivated to discuss their thoughts and experiences.

Despite these limitations, this study provides further understanding of why people continue and discontinue MA use, from the perspectives of those who lived the experience, building on previous research (Klingemann 2012; Boeri, Harbry & Gibson 2009; Sexton et al. 2008). Unlike previous studies, our findings examine the experiences of people with long histories of MA use, showing similarities and differences of those who have and have not received treatment. A significant proportion of individuals in our sample shared experiences that suggested they were chronically and seriously impaired due to their MA addiction, while others seemed to be able to control or discontinue their use prior to experiencing substantial impairments. These insights may be helpful to researchers, treatment providers and MA users to better understand the array of factors that facilitate and impede abstinence, and the long-term resources needed to promote and sustain recovery. Findings indicate individualized interventions and multiple, simultaneous approaches and resources are needed in reaching stable abstinence. Understanding long-term users’ experiences with MA addiction, relapse, and abstinence can inform strategies for engaging and sustaining MA users in treatment and recovery. Future work should longitudinally examine facilitators and barriers to abstinence from MA and other substances, in an effort to develop interventions early in the course of substance use careers.

References

- Best D, Ghufran S, Day E, Ray R, Loaring J. Breaking the habit: a retrospective analysis of desistance factors among formerly problematic heroin users. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2008;27(6):619–624. doi: 10.1080/09595230802392808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best D, Gow J, Knox T, Taylor A, Groshkova T, White W. Mapping the recovery stories of drinkers and drug users in Glasgow: quality of life and its associations with measures of recovery capital. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2012;31(3):334–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2011.00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeri MW, Harbry L, Gibson D. A qualitative exploration of trajectories among suburban users of methamphetamine. Journal of Ethnographic and Qualitative Research. 2009;3(3):139–151. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boshears P, Boeri M, Harbry L. Addiction and sociality: Perspectives from methamphetamine users in suburban USA. Addiction Research and Theory. 2011;19(4):289–301. doi: 10.3109/16066359.2011.566654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisvert RA, Martin LM, Grosek M, Clarie AJ. Effectiveness of a peer-support community in addiction recovery: participation as intervention. Occupational Therapy International. 2008;15(4):205–220. doi: 10.1002/oti.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brecht M-L, O’Brien A, von Mayrhauser C, Anglin MD. Methamphetamine use behaviors and gender differences. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29(1):89–106. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(03)00082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham JA. Remissions from drug dependence: is treatment a prerequisite? Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;59(3):211–213. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00123-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanter M, Dermatis H, Bunt G, Williams C, Trujillo M, Steinke P. Assessment of spirituality and its relevance to addiction treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007;33(3):257–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German D, Sherman SG, Sirirojn B, Thomson N, Aramrattana A, Celentano DD. Motivations for methamphetamine cessation among young people in northern Thailand. Addiction. 2006;101(8):1143–1152. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klingemann JI. Mapping the maintenance stage of recovery: a qualitative study among treated and non-treated former alcohol dependents in Poland. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2012;47(3):296–303. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agr163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laudet AB, Savage R, Mahmood D. Pathways to long-term recovery: a preliminary investigation. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2002;34(3):305–311. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2002.10399968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laus V. An Exploratory Study of Social Connections and Drug Usage Among Filipino Americans. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10903-012-9720-5. (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lende D, Leonard T, Sterk C, Elifson K. Functional methamphetamine use: The insider’s perspective. Addiction Research and Theory. 2007;15(5):465–477. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons GCB, Deane FP, Kelly PJ. Forgiveness and purpose in life as spiritual mechanisms of recovery from substance use disorders. Addiction Research and Theory. 2010;18(5):528–543. [Google Scholar]

- McGlothlin WH, Anglin MD, Wilson BD. A follow-up of admissions to the California Civil Addict Program. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1977;4(4):179–199. doi: 10.3109/00952997709002759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell SG, Morioka R, Schacht Reisinger H, Peterson JA, Kelly SM, Agar MH, Brown BS, O'Grady KE, Schwartz RP. Redefining retention: Recovery from the patient's perspective. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2011;43(2):99–107. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2011.587392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy DA, Hser Y, Huang D, Brecht ML, Herbeck DM. Self-report of longitudinal substance use: a comparison of the UCLA Natural History Interview and the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Drug Issues. 2010;40(2):495–516. doi: 10.1177/002204261004000210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson EAR, Krentzman AR, Webb JR, Browler KJ. Six-month changes in spirituality and religiousness in alcoholics predict drinking outcomes at nine months. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72(4):660–668. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semple SJ, Patterson TL, Grant I. Motivations associated with methamphetamine use among HIV+ men who have sex with men. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;22(3):149–156. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00223-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sexton RL, Carlson RG, Leukefeld CG, Booth BM. Trajectories of methamphetamine use in the rural South: A longitudinal qualitative study. Human Organization. 2008;67(2):181–193. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman SG, German D, Sirirojn B, Thompson N, Aramrattana A, Celentano DD. Initiation of methamphetamine use among young Thai drug users: a qualitative study. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;42(1):36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teruya C, Hser YI. Turning points in the life course: Current findings and future directions in drug use research. Current Drug Abuse Review. 2010;3(3):189–195. doi: 10.2174/1874473711003030189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams CT, Latkin CA. Neighborhood socioeconomic status, personal network attributes, and use of heroin and cocaine. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;32(6 Suppl):S203–S210. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]