Summary

Few studies have examined host-pathogen interactions in wildlife from an immunological perspective, particularly in the context of seasonal and longitudinal dynamics. In addition, though most ecological immunology studies employ serological antibody assays, endpoint titer determination is usually based on subjective criteria and needs to be made more objective.

Despite the fact that anthrax is an ancient and emerging zoonotic infectious disease found worldwide, its natural ecology is not well understood. In particular, little is known about the adaptive immune responses of wild herbivore hosts against Bacillus anthracis.

Working in the natural anthrax system of Etosha National Park, Namibia, we collected 154 serum samples from plains zebra (Equus quagga), 21 from springbok (Antidorcas marsupialis), and 45 from African elephants (Loxodonta africana) over 2-3 years, resampling individuals when possible for seasonal and longitudinal comparisons. We used enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays to measure anti-anthrax antibody titers and developed three increasingly conservative models to determine endpoint titers with more rigorous, objective mensuration.

Between 52-87% of zebra, 0-15% of springbok, and 3-52% of elephants had measurable anti-anthrax antibody titers, depending on the model used. While the ability of elephants and springbok to mount anti-anthrax adaptive immune responses is still equivocal, our results indicate that zebra in ENP often survive sublethal anthrax infections, encounter most B. anthracis in the wet season, and can partially booster their immunity to B. anthracis.

Thus, rather than being solely a lethal disease, anthrax often occurs as a sublethal infection in some susceptible hosts. Though we found that adaptive immunity to anthrax wanes rapidly, subsequent and frequent sublethal B. anthracis infections cause maturation of anti-anthrax immunity. By triggering host immune responses, these common sublethal infections may act as immunomodulators and affect population dynamics through indirect immunological and co-infection effects.

In addition, with our three endpoint titer models, we introduce more mensuration rigor into serological antibody assays, even under the often-restrictive conditions that come with adapting laboratory immunology methods to wild systems. With these methods we identified significantly more zebras responding immunologically to anthrax than have previous studies using less comprehensive titer analyses.

Keywords: antibody persistence, bacteria, ecological immunology, ELISA, endoparasites, host-parasite interactions, microbiology, microparasites, seroconversion dynamics, serology

Introduction

Anthrax, a zoonotic bacterial disease, occurs nearly worldwide and threatens human health, biodiversity, economics, and agricultural security (Turnbull 2008). While the disease primarily affects herbivores, humans and some carnivores are also susceptible (Turnbull et al. 2004). The disease has been known since antiquity, but it has been increasingly reported from new areas, and evidence suggests that outbreaks are increasing in frequency and severity (Clegg et al. 2006; Wafula et al. 2007) and are spreading to locations and populations previously free of the disease (Clegg et al. 2007; Muoria et al. 2007). Managing such outbreaks has become a global priority, and requires filling in the fundamental gaps in our understanding of natural anthrax ecology. Our research aims to shed light on these ecological patterns from the perspective of host susceptibility.

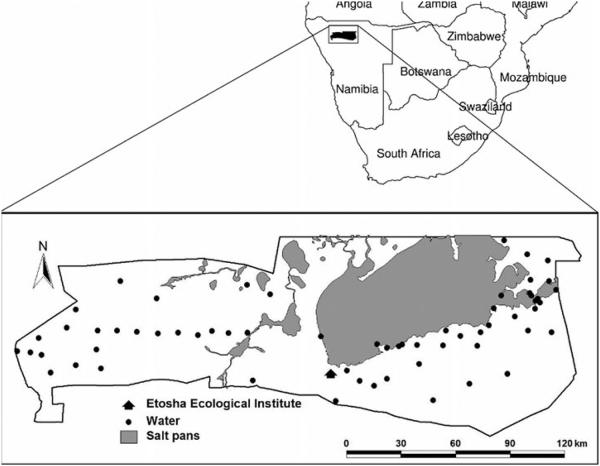

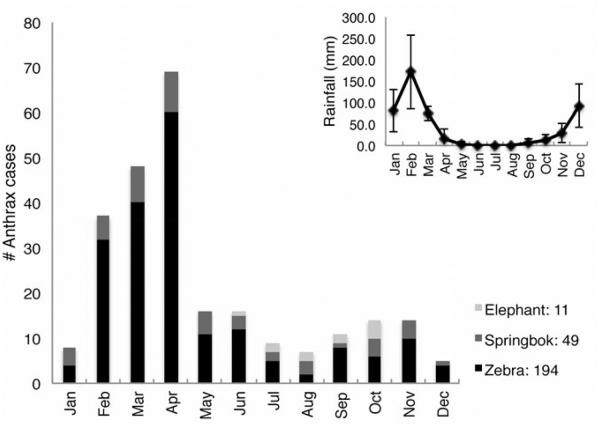

Etosha National Park (ENP) in Namibia (Fig. 1) experiences regular anthrax outbreaks that were first documented in 1964 (Ebedes 1976) and that have been recorded since 1968 by the Etosha Ecological Institute (EEI) (Turner et al. 2013). ENP’s open habitats are dominated by plains ungulates, three of which, plains zebra (Equus quagga), springbok (Antidorcas marsupialis), and blue wildebeest (Connochaetes taurinus) experience yearly anthrax outbreaks; these three species are responsible for 97% of anthrax deaths in the park, despite making up only 55% of the park’s population of large herbivores (Lindeque and Turnbull 1994). Although sporadic cases of anthrax occur year-round in ENP, outbreaks primarily occur in plains ungulates at the end of the wet season (Fig. 2) (Lindeque 1991), unlike in other systems (e.g. Gainer and Saunders 1989; Hampson et al. 2011). Anthrax in ENP affects both sexes similarly, even when adjusted for population sex ratios (Lindeque 1991; Z. Havarua, unpublished data), and does not appear to involve invertebrate mechanical vectors (Lindeque 1991). Elephants (Loxodonta africana) also experience anthrax infections in the park, with increased incidence at the beginning of the wet season (Lindeque 1991) (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Etosha National Park in northern Namibia. Most animal sampling occurred in the plains within a 20-60km radius from the Etosha Ecological Institute. Perennial watering points are marked with black circles.

Figure 2.

Total culture-confirmed anthrax cases for elephant, springbok, and plains zebra by month for 2008-2010 (years of this study). The graph insert indicates mean monthly rainfall ± standard deviation in the Okaukuejo region for this same time period.

Anthrax is caused by Bacillus anthracis, a large, gram-positive bacterium that undergoes vegetative reproduction in infected hosts but otherwise exists in a very hardy, long-lived, infectious spore form in the environment. Most evidence suggests that anthrax can only be transmitted environmentally through the spore form (Hanna & Ireland 1999), usually via ingestion of a large spore dose (Watson & Keir 1994). Within hosts, spores germinate into fast-multiplying vegetative forms that produce three soluble toxic factors, including protective antigen (PA) that complexes with the other two factors and allows them to enter host cells (Mogridge, Cunningham & Collier 2002). The collective actions of these toxins results in the peracute-to-acute death of susceptible hosts with an overwhelming septicemia of up to 109 bacterial cells per milliliter of blood (Collier & Young 2003).

Humoral immunity, particularly against the PA toxin, plays a very important role in a host’s fight against anthrax; several studies have demonstrated that the magnitude of a host’s anti-PA IgG antibody titer is correlated with level of protection against the disease (Reuveny et al. 2001; Marcus et al. 2004). Most carnivores that regularly ingest anthrax carcasses mount strong adaptive immune responses to anthrax that can be naturally boostered with frequent pathogen contact (Turnbull et al. 1992; Lembo et al. 2011; Bellan et al. 2012). Herbivores, however, while capable of forming anti-PA antibodies with vaccination, often require rigorous vaccination booster schedules to counter their initial low immune responses (Turnbull 2008). The few previous studies of natural immunity against anthrax in wildlife and livestock have indicated that, with the exception of some bovids, many wild herbivores may not develop and maintain measurable anti-anthrax antibody titers at all (Turnbull et al. 1992; Turnbull et al. 2001; Lembo et al. 2011). As measuring anti-PA titers is the most diagnostically reliable way to determine prior exposure to sublethal anthrax infection (Turnbull et al. 1992), these studies are interpreted as implying that most herbivores in these endemic disease systems are anthrax naïve and, on exposure to a large dose of B. anthracis, contract fulminant infection and die (Watson & Keir 1994).

Given the longevity of the infectious spore form and the lack of definitive evidence for epidemiologically significant vegetation reproduction of B. anthracis outside of a vertebrate host (Hanna & Ireland 1999; but see Saile & Koehler 2006 and Dey, Hoffman, and Glomski 2012), it remains unclear why sporadic or cyclic outbreaks of the disease should occur rather than a more constant incidence of anthrax cases. Given the endemic nature of anthrax in ENP and the fact that anthrax deaths do occur throughout the year in this system, it appears that animals can come into contact with B. anthracis spores in all seasons. This then raises the questions of whether exposure varies with season, host susceptibility changes with season, or hosts are able to survive some anthrax infections. We were thus motivated to more closely examine the immune dynamics of anthrax in the wild, using anti-PA antibody titers both to gauge anti-anthrax immune responsiveness in plains zebra, African elephants, and springbok in ENP, and as a signature of the incidence of sublethal anthrax infections in this system.

Additionally, we approached the problem of assessing antibody titers using a common immunology assay protocol (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, ELISA) in a more comprehensive and objective way. Serology via ELISA, the “bread and butter” of ecological immunology studies, can be used both to characterize the prevalence of infectious agents in wildlife systems, as well as to measure host immune function. ELISA methods, however, while long-established in laboratory studies, are often not as straightforward in wildlife research: positive controls, quantitatively titrated or not, are often impossible to come by; often only a few negative controls can be obtained from zoo collections; and determination of endpoint titers is usually not quantitative, with methods for determining titers varying greatly in their subjectivity, sensitivity, specificity, and statistical rigor. We have attempted with our current study to address these concerns.

Methods

Study Area and Species

This study was conducted in Etosha National Park (ENP), a 22,915 km2 fenced conservation area in northern Namibia, located between 18°30’S-19°30’S and 14°15’E-17°10’E (Fig. 1). Rainfall in ENP is highly seasonal: the rainy season lasts from November through April, with the greatest rainfall occurring during January and February (Gasaway, Gasaway & Berry 1996; Auer 1997) (Fig. 2). The only perennial water available to the park’s wildlife is found in man-made boreholes, or in natural artesian or contact springs (Auer 1997).

Zebra and springbok are the two most abundant plains ungulate species in ENP, with populations of approximately 13,000 (95% CI rounded to nearest 100: 10,900-15,000) and approximately 15,600 (95% CI rounded: 13,200-17,900). Elephants have a population of approximately 2,600 (95% CI rounded: 1,900-3,300) (EEI unpublished data 2005).

Animal Capture and Sampling

Between 2008 and 2010, samples were obtained from all three study species. With a capture team, we immobilized animals through the use of reversible anesthetics injected remotely via Pneu-Darts (Pneu-Dart Inc., Williamsport, Pennsylvania, USA). Animals were fitted with VHF (very high frequency) tracking collars (LoxoTrack, Aeroeskoebing, Denmark) or VHF-GPS/GSM (global positioning system/global system for mobile communications) collars (Africa Wildlife Tracking, Pretoria, Republic of South Africa) during the first immobilization to enable resampling of animals over several seasons. Anesthesia was reversed immediately upon collection of all samples. Animals were first immobilized and sampled on the plains within an approximately 20km radius of Okaukuejo (60km for elephants) (Fig. 1); in subsequent seasons, zebra were sampled between Okaukuejo and 100km to the east in Halali, whereas springbok and elephants were sampled again in the original area. Only adult animals were sampled for all species. We lost two zebra to predation over the course of our study (both tested negative for anthrax), with no other animal deaths. All animals were safely handled under animal handling protocol AUP R217-0509B (University of California, Berkeley).

A total of 154 serum samples were collected from zebra (10 males, 144 females), 44 from elephants (24 males, 20 females), and 21 from springbok (12 males, 9 females). Serum was kept at −20°C for up to six months, and were thereafter stored at −80°C until analyzed. Zebra were sampled over five seasons total, two wet and three dry, with several individuals sampled between two and five times total (Table 1). Springbok were sampled over two seasons, one wet and one dry, and elephants were sampled over four seasons, one wet and three dry, with several animals resampled once (Table 1).

Table 1.

Capture seasons and timing for zebra, springbok, and elephant. “#New”: new individuals and their samples; “#Re-S”: animals resampled at least once in that season. #Re-S x2, 3, 4, or 5 are the total numbers of animals for each species resampled 2, 3, 4, or 5 times.

| Species | Capture Season |

Nominal Season |

Date (Mo/Yr) |

#New | # Re- S |

# Re-S x2 |

# Re-S x3 |

# Re-S x4 |

# Re-S x5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zebra | S1 | Wet | 3-4/08 | 45 | 0 | ||||

| S2 | Dry | 10-11/08 | 14 | 22 | |||||

| S3 | Wet | 4-5/09 | 6 | 29 | |||||

| S4 | Dry | 9-11/09 | 4 | 9 | |||||

| S5 | Dry | 8/10 | 0 | 25 | |||||

| Totals | 5 | 69 | 85 | 20 | 11 | 12 | 2 | ||

|

| |||||||||

| Springbok | S1 | Dry | 8-9/09 | 13 | 0 | ||||

| S2 | Wet | 4-5/10 | 0 | 8 | |||||

| Totals | 2 | 13 | 8 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

|

| |||||||||

| Elephant | S1 | Dry | 10/08 | 10 | 0 | ||||

| S2 | Dry | 7-10/08 | 18 | 0 | |||||

| S3 | Wet | 3/10 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| S4 | Dry | 8/10 | 5 | 11 | |||||

| Totals | 4 | 34 | 12 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

Anti-PA ELISAs

We adapted the ELISA procedure to measure serum anti-PA antibody titers from Pitt et al. 2001, Marcus et al. 2004, and Turnbull et al. 2008. Each well of a 96 well ELISA plate was coated with PA at a concentration of 0.375μl. Wells were blocked with a mixture of PBS, 0.5ml/l Tween-20, and 10% (w/v) skim milk powder (Oxoid Laboratory Preparations; Basingstoke, Hampshire, England) (PBSTM).

Serial, two-fold dilutions were made (1:4-1:8192) to the ends of rows in duplicate for all samples and negative controls in PBSTM. We used goat-anti-horse IgG-heavy and light chain horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugate for zebra and rabbit-anti-goat IgG-heavy and light chain HRP conjugate for springbok (Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX), similar to methods of previous studies (Turnbull et al. 2004; Turnbull et al. 2008). As there are no domestic species closely related to elephants, Bethyl Laboratories manufactured goat-anti-elephant IgG heavy-and-light chain secondary antibodies for this study. TMB substrate (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories; Gaithersburg, MD) was added and the reaction was stopped after 30 minutes with 2N sulfuric acid. Well absorbance was read as optical density (OD) at 450nm on a SpectraMax M2 Microplate Reader using SoftMax Pro software v5.3 (Molecular Devices; Sunnyvale, CA).

We obtained 6 serum samples from plains zebra from the Woodland Park Zoo (Seattle, Washington), and 4 serum samples from African elephants and 7 serum samples from domestic goats (as the phylogenetically closest available proxies for springbok) from the Oakland Zoo (Oakland, California) for use as negative controls. We discarded 3 goat samples from further analysis due to extreme hemolysis in these samples. While the number of negative controls we obtained is small, it is not uncommon for ELISA studies to use one only negative control sample (e.g. Work et al. 2000; Reuveny et al. 2001), to simply use background absorbance values as control values rather than a dedicated negative control (e.g. Aloni-Grinstein et al. 2005), or to use no obvious negative controls at all (e.g. Turnbull et al. 1992; Svensson, Sinervo, and Comendant 2001). The highest reported number of negative control samples that we have found in previous studies was five (Schwanz et al. 2011), and thus our control numbers are reasonable and representative of the typical availability of negative control samples for both laboratory and wildlife work.

Using the preceding ELISA procedure, negative controls were first analyzed individually in duplicate, two-fold serial dilution titration series (1:4-1:8192). We chose a middle-responding control zebra as the negative control for all subsequent zebra sample ELISAs; this control essentially represented the mean of the negative control samples. We also accounted for variation between negative controls in subsequent analyses (see Rule 3 below). While all of the elephant negative controls and all goat negative controls were also not significantly different from each other in their respective analyses, we combined all elephant controls, and all goat controls in equal parts into separate, mixed samples to be used as subsequent master negative controls; doing so, rather than choosing one random control, is likely more effective for precluding questions about the choice of control comparators.

ELISA Endpoint Titer Determination

Previous ecological immunology and anthrax serology studies have used a variety of methods for determining ELISA endpoint titers, with varying degrees of subjectivity. While some studies benefit from the availability of quantitative kits for the antibodies in question, most involve the development of novel, more qualitative assays using available materials. Some studies have had access to positive controls, and have used these to determine sample endpoint titers in varying ways. However, we were unable to obtain positive controls from vaccinated animals for our assays – a common limitation in wildlife disease immunology studies – and therefore developed novel endpoint titer determination protocols based solely on more readily available negative control samples from zoo animals.

Endpoint titer determination using only negative controls as comparisons has been fraught with subjectivity with methods varying widely among published research. Studies have determined positive titers in a variety of ways, for example by using subjective, pre-determined OD cutoffs (e.g. Chabot et al. 2004); using two- or three-fold differences above negative control or background ODs as cutoffs (e.g. Aloni-Grinstein et al. 2005); determining positive samples as those above mean negative control OD plus two or three standard deviations (e.g. Reuveny et al. 2001); or by comparing samples with competitively inhibited titrations and using a pre-determined comparative cutoff (e.g. Turnbull et al. 2008). Frey, Di Canzio, and Zurakowski (1998) addressed some of these problems by establishing a method for determining ELISA endpoint titers based on the t-distribution of negative control readings. Their method increased sensitivity for detecting weak immune responses, and established good statistical power even with relatively low numbers (5-30) of negative controls. We expand on these methods here to make them even more relevant to ecological immunology studies, in which there are often much larger amounts of variation than in laboratory studies, even amongst negative controls.

We addressed the following issues:

-

1)

Even when different ELISA plates are run concurrently, there is often great enough inter-plate variability that differences between low responders and negative controls may be lost against background variation. This was addressed by running a negative control sample on every plate.

-

2)

The degree of binding in ELISA may vary substantially across a range of sera dilutions.

-

3)

There can be high background noise particularly when crude antigens are used to coat ELISA plates (Frey, Di Canzio & Zurakowski 1998). Issues 2 and 3 were addressed by running the negative control, in replicate on each plate, in the same serial dilution titration series as is used for the experimental samples; while Frey et al. suggested this step be tried in a pilot experiment, we believe that the background noise and variability in ecological samples makes it imperative that this step be included at all times, on all plates.

-

4)

Negative control sera may only be available in very small amounts.

-

5)

Plate “real estate” is limited, and reagents may be as well. Issues 4 and 5 were addressed by examining the titrated response curves of all negative controls (in duplicate) prior to the experimental assays, and then either combining the low-to-middle-responding negative controls into a 1:1 pooled negative control mixture or by choosing one middle-responding abundant sample at random for use as the negative control for all subsequent plates. This required only two rows of space out of eight on a 96 well plate.

We then established three rules for endpoint titer determination:

Rule 1: Liberal cutoff. The titer is the highest dilution in the titration series for which the mean sample OD for that dilution is greater than the mean negative control OD titration curve from all plates. This is similar to some cutoff rules used in previous studies (e.g. Aloni-Grinstein et al. 2005; Reuveny et al. 2001), though is likely more sensitive, but potentially less specific, than rules using mean negative control OD±2 or 3SD and improves by capturing the “moving target” of dilution dynamics.

Rule 2: Medium-conservative cutoff. The within-plate inter-duplicate standard deviation is estimated as:

where d = 1:22, 1:23, …, 1:213; rd,i,1 and rd,i,2 are the duplicate optical densities of the i-th sample at dilution d; and n is the number of samples (indexed by i). The endpoint titer is the last dilution at which

where is the mean sample OD at a dilution, and is the mean negative control OD at a dilution buffered by a 95% confidence interval determined by the inter-duplicate error at that dilution, across all samples. We recommend doing these calculations after all experimental samples have been analyzed, and re-calculating all titers if additional samples are run.

Rule 3: Ultra-conservative cutoff. The inter-negative control standard deviation is estimated as:

where d is as above, rd,1, …, rd,n are the optical densities of each of the unique negative control animals run on the negative control-only plate; is the mean optical density at dilution d across all negative control samples run on the negative control-only plate; and n is the number of unique negative control animals run on the negative control-only plate (indexed by i). The endpoint titer is the last dilution at which

where is as above, and is the mean negative control OD at a dilution buffered by a 95% confidence interval determined by the inter-negative control error at that dilution, across all samples. This rule is usually more conservative than Rule 2 due to the fact that variation between ODs of different negative control samples is often greater than variation between ODs of the same sample run in duplicate.

Titer Patterns With Age and Season

Generalized estimating equation (GEE) models were developed using R v2.15.2 and the geepack package (R Core Development Team, Vienna Austria; Højsgaard, Halekoh & Yan 2006) to examine the influences of age, rainfall, and capture area on anti-PA titers in resampled zebra. For all models, a working correlation matrix with a first-order autoregressive relationship was used because, while individual immune factors are likely correlated through time, these correlations should decrease between later time points and earlier samplings (Zuur et al. 2009).

In the Seasonal model, the presence or absence of an anti-PA titer via Rule 2 was included as the dependent variable, and capture area (Okaukuejo or Halali), animal age in days, and season type (wet or dry) were included as independent variables. Age was determined to half a year (converted to days) by using the methods of Smuts 1974.

In the Rainfall model the presence or absence of an anti-PA titer via Rule 2 was included as the dependent variable, and capture area, animal age in days, and cumulative rainfall one and two months prior to sampling were included as independent variables. This model was developed separately to avoid collinearity between season and rainfall parameters. Cumulative rainfall prior to sampling was determined by summing daily rainfall amounts (in mm) over the 30 or 60 days prior to each individual capture event. Previous ENP studies determined that gastrointestinal helminth infection intensity in zebras is significantly related to rainfall one and two months prior (Turner 2009). As parasite infection peaks occur only a few weeks prior to anthrax outbreaks in these hosts (W.C. Turner, unpublished data), these measures of rainfall were used here both as finer-scaled representations of season, and as potential proxies for other seasonal effects on anthrax exposure. In both Seasonal and Rainfall models, the dependent outcome was anti-PA seropositivity, modeled as a Bernoulli outcome linked to independent variables via a logit link function.

The GEE models were developed by using a backwards stepwise refinement method based on comparing the quasi-likelihood under the independence model criterion (QIC) values between maximal models and models with variables removed (Pan 2001). The QIC is analogous to Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) for GEEs, which are not strictly likelihood-based. After stepwise selection of the main terms, interaction terms between the remaining explanatory variables were added, and models were further subjected to backwards stepwise selection. Models were validated by plotting Pearson’s residuals against fitted values to look for residual patterns, examining residual histograms to assess the normality of error distributions, and plotting residuals against each explanatory variable to test for homogeneity of error variances (Zuur et al. 2009). For the final, best-fit models, Wald chi-squared tests were used to determine the significance of each estimated parameter.

Results

Prevalence of Anti-PA Antibodies

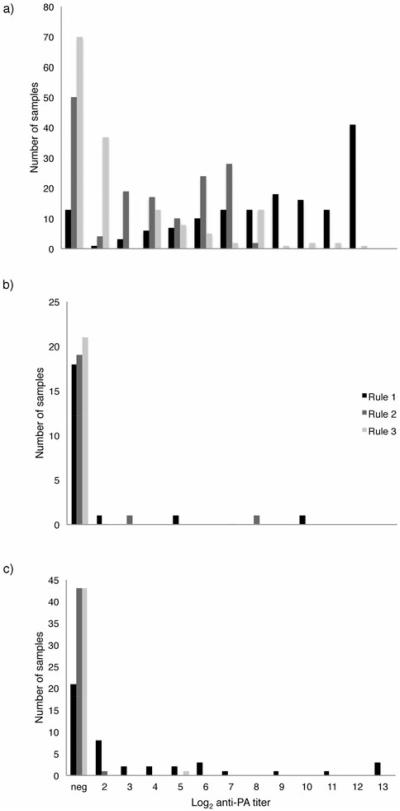

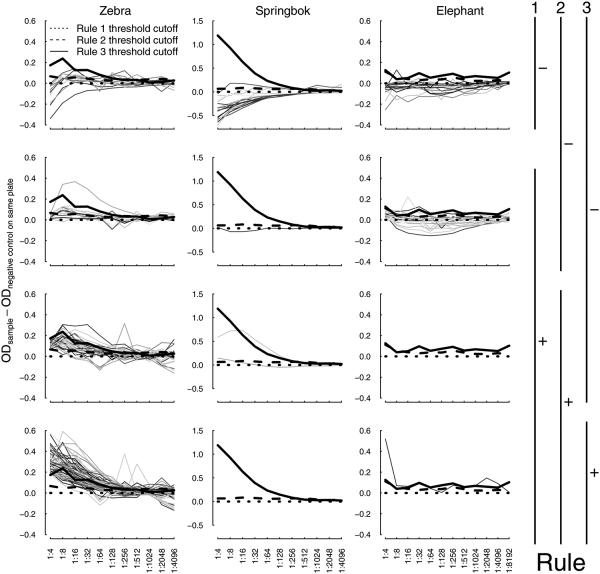

Prevalence of anti-PA antibodies in the three study species varied with the ELISA endpoint titer rule used (Table 2; Figs. 3 and 4). While few springbok and elephants showed positive titers for the more conservative rules, seropositivity prevalence among unique zebras (i.e. resampled animals were included only once in the aggregate and determined to be positive if they exhibited positive titers at least once) ranged from 52-87% across the three endpoint determination rules (Table 2). Due to the lower apparent sensitivity with Rule, and because Rule 2 appeared to be sensitive enough to capture a large number of positive zebra titers in our assay while still employing a conservative assessment rubric, we used zebra titers generated with Rule 2 calculations for further analyses.

Table 2.

Prevalence (%) of antibodies against B. anthracis PA toxin in zebra, springbok, and elephant as determined by three endpoint titer rules. “All”: all samples tested from that species, including resampled individuals. “Unique”: resampled animals were included only once in the aggregate and determined to be positive if they exhibited positive titers at least once. Numbers in parentheses: number seropositive.

| Species | N | Rule 1 | Rule 2 | Rule 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| All | Unique | All | Unique | All | Unique | All | Unique | |

| Zebra | 154 | 69 | 91.6 (141) | 86.9 (60) | 67.5 (104) | 62.3 (43) | 54.5 (84) | 52.2 (36) |

| Springbok | 21 | 13 | 14.3 (3) | 15.4 (2) | 9.5 (2) | 7.7 (1) | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Elephant | 44 | 33 | 52.3 (23) | 51.5 (17) | 2.3 (1) | 3.0 (1) | 2.3 (1) | 3.0 (1) |

Figure 3.

Antibody endpoint titers to B. anthracis PA toxin in a) plains zebra, b) springbok, and c) elephant, determined by each of the three titer cutoff rules. Titers are shown as log2 of the reciprocal of dilution cut-off for clarity.

Figure 4.

Optical density titer cutoff rules by species. Colored lines represent the difference between the optical densities (OD) of a sample Etosha animal (averaged between duplicates) and the OD of the negative control sample (averaged between duplicates) run on the same plate. The thick black lines show the threshold cutoffs for these differences that determined the titer assigned to an animal. Each sample’s OD curve appears only once in this figure (i.e. there are 154 colored lines in the left column representing each unique zebra serum sample). Any animals whose OD curve was never greater than the negative control on its plate are considered seronegative by all three Rules and appear only in the top row. Animals are considered positive by Rules 1, 2, and 3 when their OD curve was greater than the negative control (dotted line), greater than the negative control plus the 1.96 times the standard deviation between duplicate samples (dashed line), or greater than the negative control plus 1.96 times the standard deviation amongst the negative control population (run on separate plates; solid line), respectively. Thus, animals that are positive by Rule 3, the most conservative criterion, appear only in the bottom (fourth) row. The third row shows the animals that are positive by both Rules 1-2 but not Rule 3 and, similarly, the second row shows animals that are positive by Rule 1 but not by Rules 2-3.

Prevalences of anti-PA antibodies in unique springbok ranged from 0-15% (Table 2), with Rule 1 yielding 1.5 times as many seropositive animals as Rule 2. Prevalence of anti-PA seropositivity in unique elephants ranged from 3-52% (Table 2). Given the presence of some seropositive animals via Rule 2, we are confident that at least some of the positive animals via Rule 1 were true positives. While understanding that Rule 1 may also be less specific, we focus further elephant titer analyses on Rule 1 results to allow greater resolution of our examinations of longitudinal titer changes. While we could not compare sex ratios of animals with positive titers for zebra and springbok due to small sample sizes (too few zebra males; too few seropositive springbok), we compared prevalence and magnitude of anti-PA titers in elephant bulls and cows. Prevalence in males (47.8%) and females (47.6%) did not differ, nor did the magnitude of titers between the sexes (Wilcoxon U=90, N1=11, N2=10, p=0.139).

Changes in Anti-PA Titers Over Time

Eleven resampled zebra seroconverted positively (i.e. changed from having no titer to having a measurable titer) and 13 seroconverted negatively (i.e. changed from having a measurable titer to having no measurable titer) during the course of our study (Fig. 5). For zebra sampled four or five times over the two-year study period, we found that few animals maintained relatively stable titers over several seasons, with the majority of titers increasing or decreasing substantially within each sampling interval (Fig. 5). As our sampling intervals were coarse (between three and eight months for individual recaptures), we were not able to determine exactly when a negatively seroconverting animal lost its measurable titer. However, because both measurable titer increases and decreases occurred frequently and rapidly between our sampling intervals, we were confident that animals did not maintain titers for significantly longer than these time periods without additional B. anthracis exposure. Thus, examining animals that seroconverted negatively over the course of one sampling interval, we found that mean time to negative seroconversion was less than 6.3 ± 1.3 months (mo) (mean ± SD; N=9), with a range of less than 3.5-7.4mo.

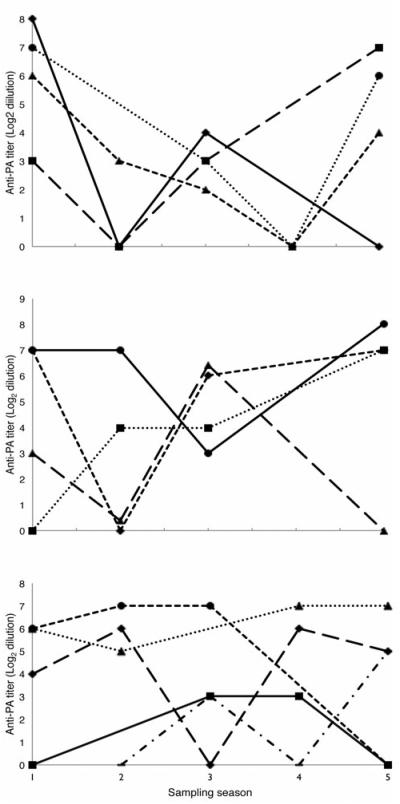

Figure 5.

Change over time of zebra antibody titers to B. anthracis PA toxin. Titers are shown as the log2 of the reciprocal of the dilution endpoint as determined by Rule 2. Only individuals sampled 4 or 5 times are shown, with each plot showing 4-5 different animals for 13 zebra total across the 3 plots. Sampling seasons 1, 2, 3, and 4 are roughly 6 months apart from each other, whereas S5 is approximately 12 months after S4. Overlapping portions of some plots have been jittered slightly for clarity.

Of the three seropositive springbok via Rule 1, only one was resampled while also negatively seroconverting from one season to the next, sometime over the course of 7.8mo. Three elephants negatively seroconverted over a mean time of less than 17.5 ± 4.6mo and range of 12.6-21.7mo. Given the low sample size of resampled springbok and elephants, the low number of sampling times, and the long sampling intervals, these are obviously coarse estimates of negative seroconversion times for these species.

Relationships Between Anti-PA Titers, Season, and Age in Zebra

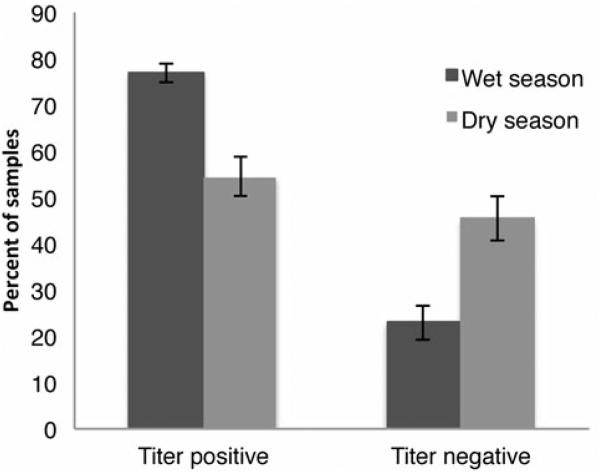

The best fitting Seasonal GEE model contained season and age, though only season was significant (odds of having a positive titer estimated to be 0.9998 smaller for every additional day of age, 95% CI (0.9995, 1.00003); Wald statistic=0.76, p=0.382); the wet season was significantly correlated with higher anti-PA seropositivity (odds ratio 2.31, 95% CI (1.66, 3.21); Wald statistic=6.52, p=0.011, ΔQIC=2.00 between models with season and age and with only season), with a seropositivity of 76% and 58% in the wet and dry seasons, respectively (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Percent (± 95% CI) of zebra samples with positive antibody titers or no titers against B. anthracis PA toxin, compared between wet and dry seasons.

The best fitting Rainfall GEE model contained cumulative rainfall one month prior to capture, cumulative rainfall two months prior to capture (hereafter simply “Rain1” and “Rain2”), and age. Rain1 was significantly, negatively associated with anti-PA titer (odds of having a positive versus negative titer is estimated to be 0.964 smaller for every mm of extra Rain1, 95% CI (0.951, 0.977); Wald statistic=7.90, p=0.005), while Rain2 was significantly, positively associated with anti-PA titer (odds ratio 1.016, 95% CI (1.011, 1.022); Wald statistic=9.53, p=0.002, ΔQIC=2.00 between models with rainfalls and age and with only rainfalls). Age was not significant in this model (odds ratio 0.9998, 95% CI (09996, 1.00003); Wald statistic=0.73, p=0.392). The best fitting Rainfall model had a slightly improved QIC over the best fitting Seasonal model (ΔQIC=1.00).

Discussion

Hosts in ENP Experience Sublethal Anthrax Infections

Our data show that, regardless of which of our rules are used for ELISA endpoint antibody titer calculations, zebra in ENP experience sublethal anthrax infections and survive, bearing the immune signatures of these infections. Using anti-PA titers as a proxy for sublethal anthrax infection occurrence, and given the fact that anthrax is not a chronic disease (Hugh-Jones & de Vos 2002), the cumulative incidence of sublethal anthrax in the ENP zebra population over the three years of this study can be estimated to be at least 62% (Table 2). Given that we observed positive and negative seroconversions for several zebra between sampling occasions roughly six months apart, many more positive seroconversions were likely missed. Thus, we believe this estimate is biased downward and gives a lower bound for the actual incidence of sublethal anthrax infections in these hosts.

In addition, we found that zebras are more likely to have measurable anti-PA antibody titers in wet seasons compared to in dry seasons, perhaps indicating that anthrax exposure rates differ between seasons (see discussion below). However, when actual amounts of rainfall are taken into account in our system, a more complex picture emerges. While more cumulative rainfall in the two months prior to sampling predicts higher anti-PA antibody titers, more rainfall in the one month prior to sampling predicts lower anti-PA antibody titers. This may be at least in part due to a time lag effect of rainfall, and changes in foraging behavior and animal movement with changes in rainfall. Additionally, given the strong correlation between rainfall and GI parasite infection intensities in this system, the time lag between GI parasite peaks and anthrax deaths in the wet season (W. Turner, unpublished data), and the fact that GI parasites can be strongly immunomodulatory and predispose hosts to bacterial coinfections (Chen et al. 2005), it is likely that there are coinfection and immunomodulatory effects here not being accounted for here.

Our antibody titer results in elephants and springbok are somewhat equivocal; however, the fact that we did see at least one animal of each of these species with a measurable titer indicates that both elephants and springbok are also capable of mounting adaptive immune responses against anthrax, and that they experience and survive anthrax infection upon occasion. As approximately half of elephant samples showed measurable anti-PA titers under Rule 1 (Table 2), with some titers being quite high (Figs. 3 and 4), it is likely that Rule 2 was simply not sensitive enough in this case to detect all of the true positive titers. As such, it is likely that the cumulative incidence of sublethal anthrax in elephants over the course of this study was somewhere in between that estimated by Rule 2 (3%) and that estimated by Rule 1 (about 50%).

Comparison to Previous Studies

The results of our study differ from those of the few other previous wildlife anthrax serology studies. Out of 131 herbivore sera from ENP tested previously, only eight (three springbok, one giraffe, four black rhino) had positive, measurable anti-PA titers, and no zebras (N=24) and no elephants (N=12) tested with positive titers (Turnbull et al. 1992). That study, however, used a competitive inhibition ELISA to measure anti-PA antibodies; this requires enough antibody so that there will, at some point in the dilution curves, exist a bound antibody excess compared to soluble antigen. Thus, this assay may not be sensitive enough to detect lower responders. In addition, this assay uses each animal as its own control and comparison, which is not as rigorous as comparing samples to a designated control.

While Lembo et al. (2011) found some measurable anti-PA titers in Serengeti buffalo and wildebeest, they found no positive titers in zebras (N=85). Lack of assay sensitivity for low responders may have been an issue; their study used a new, commercially available anti-PA antibody kit (QuickELISA anthrax PA kit immunoassay, Immunetics, Inc., Boston, MA), which, while promising, has yet to be validated for many species (Lembo et al. 2011). The real difference in titers, however, likely lies in the fact that anthrax is less ubiquitous in the Serengeti ecosystem than it is in ENP. The Serengeti study only detected 283 suspected (non-culture-confirmed) anthrax positive cases (34 of them zebra) over 14 years, whereas we found 254 culture-confirmed anthrax carcasses in our three study species (of 270 for all host species) over our three-year study period (194 of them zebras) (Fig. 2). Thus, the environmental level of B. anthracis in the Serengeti ecosystem may be significantly lower than that in ENP, resulting in their herbivores encountering and ingesting significantly fewer B. anthracis spores than do ENP herbivores.

Surviving Anthrax Exposure

A full plasma cell/antibody memory response requires at least three to six days to mature (Marcus et al. 2004), which is usually too slow to be effective against a fulminant anthrax infection that can subacutely kill the host. Innate immune cells such as macrophages and neutrophils likely play a large role in preventing at least lower doses of anthrax from becoming established in susceptible hosts (Cote, Van Rooijen & Welkos 2006). In addition, evidence from imaging studies indicates that B. anthracis spores germinate and establish infections at the initial site of inoculation, and do not spread systemically until nearly 1.5-2 days after infection (Glomski et al. 2007). This delay may give the immune system enough time to prevent dissemination and fulminant infection.

Adaptive immune mechanisms, including low anti-PA titers prior to memory maturation, may also be protective early in low-dose anthrax infection. PA has been detected on the surfaces of B. anthracis spores as early as one hour into the germination process, and anti-PA antibodies have been found to bind strongly to the surface of spores (Welkos et al. 2001; Cote et al. 2005). This early antibody binding has direct consequences for the fate of the spore: it increases the rate of macrophage phagocytosis of spores, and enhances the rate of intracellular spore germination, which is essential as macrophages can only kill germinating spores (Welkos et al. 2001).

Maintaining Immunity to Anthrax

While all three study species mounted measurable adaptive immune responses against anthrax toxin, these responses were short-lived. The average time to loss of titer in zebra of approximately less than six months is not surprising, given that anthrax vaccines must be boostered at least annually in humans and livestock (Turnbull et al. 1992; Turnbull 2008). While our sampling time intervals only allowed us to detect negative seroconversion within an 8-12 month scale for springbok and elephants, the evidence suggests that anti-anthrax adaptive immunity in these hosts may also be short-lived.

While the best models as chosen by QIC included the negative effect of animal age on seropositivity, the effect of age was not statistically significant as determined by Wald confidence intervals. Though this effect was too noisy or too weak to be significant at our sample size, we believe this indicates that animals may be unlikely to maintain a positive titer trajectory as they age due to low-dose exposures that are too temporally inconsistent in the face of rapidly waning immunity. However, we did find evidence for at least short-term maturation of the anti-anthrax immune response in several animals, indicating the presence of a natural booster effect with subsequent infections and that memory responses are useful and successful in fighting off anthrax (Bellan et al. 2012; Figs. 5 and 6). Evidence from laboratory studies indicates that a maturing memory response can, in fact, occur even with extremely low initial doses of B. anthracis, and that these memory responses can be protective even in the face of higher subsequent B. anthracis dose challenge (Marcus et al. 2004). In that study, some animals vaccinated with moderate doses also showed full survival after a subsequent large B. anthracis dose, even though their titers had decreased to non-detectable levels in the months prior to challenge.

These findings may have important implications for wild herbivores becoming infected with low doses of B. anthracis; by doing so, they may be effectively “vaccinating” themselves against anthrax, and even low anti-PA titers may be more protective against subsequent infection than has been previously thought. Given the fact that very low infections with B. anthracis might be defeated by a host without creating an immune signature (e.g. Aloni-Grinstein et al. 2005 had to booster guinea pigs three times with an oral anthrax vaccine to obtain measurable titers), the first anti-PA titer in our study animals may represent multiple previous, undetected infections.

Species Differences in Anthrax Immunity

While the species variation in anthrax titer prevalence in this study (Table 2) may be due, in part, to differences in antibody reagents used for each species assay, it also likely reflects some ecological, life history-related, or immunological species differences. Springbok in ENP do experience anthrax outbreaks in the wet season, but at much lower observable numbers than do zebra (Lindeque 1991; Fig. 2). Although lower observed mortality rates could be due in part to a detection bias precipitated by smaller body size and quicker consumption after death, it is likely also due to different infection rates between the two species. Rainfall and vegetation greening effects have previously been found to be important in predicting anthrax outbreaks in a North American anthrax system, though no underlying mechanisms connecting rainfall and outbreaks were postulated in this study (Blackburn and Goodin 2013). Interestingly, a recent study in ENP found that increased rainfall caused ungulates to ingest more soil in the wet season, likely due, at least in part, to loosening of soil around plant roots (Turner et al. 2013). However, while soil ingestion increased significantly during the wet season compared to in the dry for both zebra and springbok, zebra ingested seven times more soil per day than did springbok. Thus, springbok likely have less overall contact with B. anthracis spores than do zebras, likely due to the predominance of browsing in springbok and grazing in zebras (Gordon & Prins 2008). In addition, we found that zebras are significantly more likely to have a positive anti-PA titer in the wet season compared to in the dry season (Fig. 6), indicating that they are likely encountering more B. anthracis at this time, perhaps due to soil ingestion. Zebras, as hindgut fermenters, also eat significantly more per body weight than do ruminants such as springbok (Gordon & Prins 2008), which may also increase their spore exposure rate. In addition, zebra are significantly more water-dependent than are the more arid-adapted springbok; zebra in ENP drink from water sources nearly every day (R. Zidon, unpublished data), whereas springbok drink less often and can sometimes obtain all of their water needs from nutritional sources (Nagy & Knight 1994; Auer 1997). While waterborne spread is unlikely to cause fulminant anthrax infection (Durrheim et al. 2009), the low concentrations of B. anthracis spores found in up to 26% of ENP watering sources may be enough to “booster” zebras more often than springbok with sublethal anthrax infections (Lindeque & Turnbull 1994).

Recent work by Beyer et al. (2012) revealed that zebras, springbok, and elephants in ENP are infected with and die from the same strains of anthrax, so outbreak timing differences in elephants are not microbiological in nature. Elephant movement patterns in ENP, however, are quite different from those of the plains herbivores; when the majority of zebras and springbok are congregating in the wet season in the area surrounding Okaukuejo, elephants are very scarce on the Okaukuejo plains (J. W. Kilian, unpublished data). Elephants return to these plains, where the majority of anthrax outbreaks have occurred throughout known ENP history, in the dry season. Recent zebra deaths in this area during the previous season may create potent locally infectious zones (LIZs) of concentrated B. anthracis; even if these spore sinks become dispersed over the landscape with time, it is likely that these LIZs remain for at least the next several months for elephants to contact (Lindeque 1991; Bellan et al. 2013). As elephants are mostly browsers (Codron et al. 2006), they, like springbok, may not ingest B. anthracis as much and as often as do zebras, thereby resulting in lower anti-PA titers compared to those in zebras and potentially less protection against subsequent doses. These combined factors may help account for the differences in elephant anti-anthrax titer prevalence, as well as the differences in outbreak timing in this species compared to in other ENP hosts. Similar to zebras, however, elephants are quite water-dependent, with home range sizes determined by water hole density (Young and Van Aarde 2010) and elephants ingesting large quantities of water at a time. Thus, it might be predicted that exposure to low doses of spores in drinking water would also prompt titer development in elephants. The lower seroprevalence in elephants compared to in zebras in this study may thus indicate that water exposure does not play an important role in sublethal anthrax exposure in ENP, or that elephant immune responses to anthrax differ greatly from those of zebras.

Conclusions

In summary, zebra in ENP often become infected with, and survive, B. anthracis infection. This is the first study to demonstrate that zebra can mount protective immune responses against B. anthracis. In the process, these hosts can build up their immunity to B. anthracis over time, at least over the short term. Zebra appear to have a higher exposure to B. anthracis in the wet season, though factors other than season alone also likely affect the complex immune dynamics of anthrax in these hosts. Elephants and springbok in ENP also appear to experience sublethal anthrax infections, though at lower rates than do zebras. Though adaptive immunity to anthrax wanes rapidly in all three of our study species, there is evidence that subsequent sublethal B. anthracis infections that occur frequently enough can act as immune boosters that result in maturation of the anti-PA response in these hosts. This antibody maturation response also serves as an immune signature indicating that even susceptible hosts in an anthrax-endemic system survive multiple anthrax infections over their lifetimes.

These results show that, rather than being an all-or-nothing disease, anthrax often occurs as a sublethal infection in susceptible herbivorous hosts in an endemic anthrax system. Plains herbivore populations in ENP are not food limited, and it has been hypothesized that, alongside predation, anthrax is a main population-limiting factor in this system (Gasaway, Gasaway & Berry 1996). Indeed, recent evidence suggests that observed mortalities likely severely underestimate true outbreak size in zebras (Bellan et al. 2013). Our findings of high rates of sublethal anthrax infections in these hosts supports the hypothesis that anthrax in endemic systems plays a larger role in population dynamics than has been previously appreciated.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Namibian Ministry of Environment and Tourism for permission to do this research, and the staff in the Directorate of Scientific Services at the Etosha Ecological Institute for logistical support and assistance. We thank Mark Jago, Conrad Brain, Peter Morkel, Ortwin Aschenborn, Martina Küsters, Shayne Kötting, Gabriel Shatumbu, Wilferd Versfeld, Marthin Kasaona, Royi Zidon, and Werner Kilian for their assistance with sample collection. We thank Bryan Krantz for providing PA for the ELISAs. This research was supported by Andrew and Mary Thompson Rocca Scholarships, a Carolyn Meek Memorial Scholarship, UCB Graduate Division Grants, a James S. McDonnell grant, USDI Fish and Wildlife Service Grant 98210-8-G745 to WMG, and NIH grant GM83863 to WMG.

Footnotes

Data accessibility

Data available from the Dryad Digital Repository: http://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.73f23

References

- Aloni-Grinstein R, Gat O, Altboum Z, Velan B, Cohen S, Shafferman A. Oral spore vaccine based on live attenuated nontoxinogenic Bacillus anthracis expressing recombinant mutant protective antigen. Infection and Immunity. 2005;73:4043–4053. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.7.4043-4053.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auer C. Chemical quality of water at waterholes in the Etosha National Park. Madoqua. 1997;20:121–128. [Google Scholar]

- De Beer Y, Van Aarde RJ. Do landscape heterogeneity and water distribution explain aspects of elephant home range in southern Africa’s arid savannas? Journal of Arid Environments. 2008;72:2017–2025. [Google Scholar]

- Bellan SE, Cizauskas CA, Miyen J, Ebersohn K, Küsters M, Prager KC, Van Vuuren M, Sabeta C, Getz WM. Black-backed jackal exposure to rabies virus, canine distemper virus, and Bacillus anthracis in Etosha National Park, Namibia. Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 2012;48:371–81. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-48.2.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellan SE, Gimenez O, Choquet R, Getz WM. A hierarchical distance sampling approach to estimating mortality rates from opportunistic carcass surveillance data. Methods in Ecology and Evolution. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bigalke RC, Van Hensbergen HJ. Some behavioral considerations in springbok management. In: Skinner JD, Dott HM, editors. Proceedings of a Workshop on Springbok. The Zoological Society of Southern Africa and The Eastern Cape Game Management Association; Graaff Reinet, South Africa: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn J, Goodin D. Differentiation of springtime vegetation indices associated with summer anthrax epizootics in west Texas, USA, deer. Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 2013;49:699–703. doi: 10.7589/2012-10-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabot DJ, Scorpio A, Tobery SA, Little SF, Norris SL, Friedlander AM. Anthrax capsule vaccine protects against experimental infection. Vaccine. 2004;23:43–47. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Louie S, Mccormick B, Allan W, Shi HN, Walker WA. Concurrent infection with an intestinal helminth parasite impairs host resistance to enteric Citrobacter rodentium and enhances Citrobacter-induced colitis in mice. Infection and Immunity. 2005;73:5468–5481. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.9.5468-5481.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cizauskas CA, Bellan SE, Turner WC, Vance RE, Getz WM. Frequent and seasonally variable sublethal anthrax infections are accompanied by short-lived immunity in an endemic system. Dryad Digital Repository. 2014 doi: 10.1111/1365-2656.12207. DOI: 10.5061/dryad.73f23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clegg SB, Turnbull PCB, Foggin CM, Lindeque PM. Massive outbreak of anthrax in wildlife in the Malilangwe Wildlife Reserve, Zimbabwe. Veterinary Record, 2007;160:113–118. doi: 10.1136/vr.160.4.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clegg SB, Wildlife Anthrax Epizootic Workshop Working Group Preparedness for anthrax epizootics in wildlife areas. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2006;12 [Google Scholar]

- Codron J, Lee-Thorp JA, Sponheimer M, Codron D, Grant RC, De Ruiter DJ. Elephant (Loxodonta africana) diets in Kruger National Park, South Africa: Spatial and landscape differences. Journal of Mammalogy. 2006;87:27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Collier RJ, Young JAT. Anthrax Toxin. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 2003;19:45–70. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.111301.140655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cote CK, Van Rooijen N, Welkos SL. Roles of macrophages and neutrophils in the early host response to Bacillus anthracis spores in a mouse model of infection. Infection and Immunity. 2006;74:469–480. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.1.469-480.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cote CK, Rossi CA, Kang AS, Morrow PR, Lee JS, Welkos SL. The detection of protective antigen (PA) associated with spores of Bacillus anthracis and the effects of anti-PA antibodies on spore germination and macrophage interactions. Microbial Pathogenesis. 2005;38:209–225. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey R, Hoffman P, Glomski I. Germination and amplification of anthrax spores by soil-dwelling amoebas. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2012;78:8075–8081. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02034-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durrheim DN, Freeman P, Roth I, Hornitzky M. Epidemiologic questions from anthrax outbreak, Hunter Valley, Australia. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2009;15:840–842. doi: 10.3201/eid1505.081744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebedes H. Anthrax epizootics in Etosha National Park. Madoqua. 1976;10:99–118. [Google Scholar]

- Frey a, Di Canzio J, Zurakowski D. A statistically defined endpoint titer determination method for immunoassays. Journal of Immunological Methods. 1998;221:35–41. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(98)00170-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gainer RS, Saunders JR. Aspects of the epidemiology of anthrax in Wood Buffalo National Park and environs. Canadian Veterinary Journal. 1989;30:953–956. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasaway WC, Gasaway KT, Berry HH. Persistent low densities of plains ungulates in Etosha National Park, Namibia: testing the food-regulating hypothesis. Canadian Journal of Zoology. 1996;74:1556–1572. [Google Scholar]

- Glomski IJ, Piris-Gimenez A, Huerre M, Mock M, Goossens PL. Primary involvement of pharynx and Peyer’s patch in inhalational and intestinal anthrax. PLoS Pathogens. 2007;3:e76. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon IJ, Prins HHT. The Ecology of Browsing and Grazing. Springer; Berlin, Germany: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hampson K, Lembo T, Bessell P, Auty H, Packer C, Halliday J, Beesley CA, Fyumagwa R, Hoare R, Ernest E, Mentzel C, Metzger KL, Mlengeya T, Stamey K, Roberts K, Wilkins PP, Cleaveland S. Predictability of anthrax infection in the Serengeti, Tanzania. Journal of Applied Ecology. 2011;48:1333–1344. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2664.2011.02030.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna PC, Ireland JAW. Understanding Bacillus anthracis pathogenesis. Trends in Microbiology. 1999;7:180–182. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(99)01507-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Højsgaard S, Halekoh U, Yan J. The R package geepack for generalized estimating equations. Journal of Statistical Software, 2006;15:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Hugh-Jones ME, De Vos V. Anthrax and wildlife. Revue Scientifique et Technique Office International des Epizooties. 2002;21:359–383. doi: 10.20506/rst.21.2.1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang TJ, Fenton MJ, Weiner MA, Hibbs S, Basu S, Baillie L, Cross AS. Murine macrophages kill the vegetative form of Bacillus anthracis. Infection and Immunity. 2005;73:7495–7501. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.11.7495-7501.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leggett K. Daily and hourly movement of male desert-dwelling elephants. The African Journal of Ecology. 2009;48:197–205. [Google Scholar]

- Lembo T, Katie H, Auty H, Bessell P, Beesley CA, Packer C, Halliday J, Fyumagwa R, Hoare R, Ernest E, Mentzel C, Mlengeye T, Stamey K, Wilkins PP, Cleaveland S. Serologic surveillance of anthrax in the Serengeti Ecosystem, Tanzania, 1996–2009. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2011;17:387–394. doi: 10.3201/eid1703.101290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindeque PM. Factors affecting the incidence of anthrax in the Etosha National Park, Namibia. Council for National Academic Awards; England: 1991. PhD Dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Lindeque PM, Turnbull PC. Ecology and epidemiology of anthrax in the Etosha National Park, Namibia. The Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research. 1994;61:71–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus H, Danieli R, Epstein E, Velan B, Shafferman A, Reuveny S. Contribution of immunological memory to protective immunity conferred by Bacillus anthracis protective antigen-based vaccine. Infection and Immunity. 2004;72:3471–3477. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.6.3471-3477.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogridge J, Cunningham K, Collier RJ. Stoichiometry of anthrax toxin complexes. Biochemistry. 2002;41:1079–82. doi: 10.1021/bi015860m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muoria PK, Muruthi P, Kariuki WK, Hassan BA, Mijele D, Oguge NO. Anthrax outbreak among Grevy’s zebra (Equus grevyi) in Samburu, Kenya. African Journal of Ecology. 2007;45:483–489. [Google Scholar]

- Nagy KA, Knight MH. Energy, water, and food use by springbok antelope (Antidorcas marsupialis) in the Kalahari Desert. Journal of Mammalogy. 1994;75:860–872. [Google Scholar]

- Pan W. Akaike’s information criterion in generalized estimating equations. Biometrics. 2001;57:120–125. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2001.00120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt MLM, Little SF, Ivins BE, Fellows P, Barth J, Hewetson J, Gibbs P, Dertzbaugh M, Friedlander AM. In vitro correlate of immunity in a rabbit model of inhalational anthrax. Applied Microbiology. 2001;19:4768–4773. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(01)00234-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Development Team . R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2012. ISBN 3-900051-07-0, URL http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Reuveny S, White MD, Adar YY, Kafri Y, Altboum Z, Gozes Y, Kobiler D, Shafferman A, Velan B. Search for correlates of protective immunity conferred by anthrax vaccine. Infection and Immunity. 2001;69:2888–2893. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.5.2888-2893.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saile E, Koehler TM. Bacillus anthracis multiplication, persistence, and genetic exchange in the rhizosphere of grass plants. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2006;72:3168–3174. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.5.3168-3174.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwanz LE, Brisson D, Gomes-Solecki M, Ostfeld RS. Linking disease and community ecology through behavioural indicators: Immunochallenge of white-footed mice and its ecological impacts. The Journal of Animal Ecology. 2011;80:204–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2010.01745.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smuts GL. Age determination in Burchell’s zebra (Equus burchelli antiquorum) from the Kruger National Park. Journal of the South African Wildlife Management Association. 1974;4:103–115. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson E, Sinervo B, Comendant T. Condition, genotype-by-environment interaction, and correlational selection in lizard life history morphs. Evolution. 2001;55:2053–2069. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2001.tb01321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull PCB. Anthrax in Humans and Animals. 4th. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull PCB, Diekmann M, Kilian JW, Versfeld W, De Vos V, Arntzen L, Wolter K, Bartels P, Kotze A. Naturally acquired antibodies to Bacillus anthracis protective antigen in vultures in southern Africa. Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research. 2008;75:95–102. doi: 10.4102/ojvr.v75i2.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull PCB, Doganay M, Lindeque PM, Aygen B, McLaughlin J. Serology and anthrax in humans, livestock and Etosha National Park wildlife. Epidemiology and Infection. 1992;108:299–313. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800049773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull PCB, Hutson RA, Ward MJ, Jones MN, Quinn CP, Finnie NJ, Duggleby CJ, Kramer JM, Melling J. Bacillus anthracis but not always anthrax. Journal of Applied Bacteriology. 1992;72:21–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1992.tb04876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull PC, Rijks J, Thompson I, Hugh-Jones M, Elkin B. Presented at: 4th International Anthrax Conference; 2001 Jun 10-13. Annapolis; Maryland, USA: 2001. Seroconversion in bison (Bison bison) in northwest Canada experiencing sporadic and epizootic anthrax. [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull PCB, Tindall BW, Coetzee JD, Conradie CM, Bull RL, Lindeque PM, Huebschle OJB. Vaccine-induced protection against anthrax in cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) and black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis) Vaccine. 2004;22:3340–3347. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner WC. The ecology of orally ingested parasites in ungulates of Etosha National Park. University of California at Berkeley; Berkeley, California, USA: 2009. PhD Dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Turner WC, Imologhome P, Havarua Z, Kaaya GP, Mfune JKE, Mpofu IDT, Getz WM. Soil ingestion, nutrition and the seasonality of anthrax in herbivores of Etosha National Park. Ecosphere. 2013;4:art13. [Google Scholar]

- Wafula MM, Atimnedi P, Charles T. Managing the 2004/05 anthrax outbreak in Queen Elizabeth and Lake Mburo National Parks, Uganda. African Journal of Ecology. 2007;46:24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Watson A, Keir D. Information on which to base assessments of risk from environments contaminated with anthrax spores. Epidemiology and Infection. 1994;113:479–490. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800068497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner ZP, Boyer AE, Gallegos-Candela M, Cardani AN, Barr JR, Glomski IJ. Debridement increases survival in a mouse model of subcutaneous anthrax. PloS ONE. 2012;7:e30201. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welkos S, Little S, Friedlander A, Fritz D. The role of antibodies to Bacillus anthracis and anthrax toxin components in inhibiting the early stages of infection by anthrax spores. Microbiology. 2001;147:1677–1685. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-6-1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Work TM, Balazs GH, Rameyer RA, Chang SP, Berestecky J. Assessing humoral and cell-mediated immune response in Hawaiian green turtles, Chelonia mydas. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology. 2000;74:179–194. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2427(00)00168-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young KD, Van Aarde RJ. Density as an explanatory variable of movements and calf survival in savanna elephants across southern Africa. The Journal of Animal Ecology. 2010;79:662–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2010.01667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuur A, Ieno E, Walker N, Saveliev A, Smith G. Mixed Effects Models and Extensions in Ecology with R. Springer Science+Business Media; LLC, New York, NY: 2009. pp. 1–574. [Google Scholar]