Abstract

The yeast Exo1p nuclease functions in multiple cellular roles: resection of DNA ends generated during recombination, telomere stability, DNA mismatch repair, and expansion of gaps formed during the repair of UV-induced DNA damage. In this study, we performed high-resolution mapping of spontaneous and UV-induced recombination events between homologs in exo1 strains, comparing the results with spontaneous and UV-induced recombination events in wild-type strains. One important comparison was the lengths of gene conversion tracts. Gene conversion events are usually interpreted as reflecting heteroduplex formation between interacting DNA molecules, followed by repair of mismatches within the heteroduplex. In most models of recombination, the length of the gene conversion tract is a function of the length of single-stranded DNA generated by end resection. Since the Exo1p has an important role in end resection, a reduction in the lengths of gene conversion tracts in exo1 strains was expected. In accordance with this expectation, gene conversion tract lengths associated with spontaneous crossovers in exo1 strains were reduced about twofold relative to wild type. For UV-induced events, conversion tract lengths associated with crossovers were also shorter for the exo1 strain than for the wild-type strain (3.2 and 7.6 kb, respectively). Unexpectedly, however, the lengths of conversion tracts that were unassociated with crossovers were longer in the exo1 strain than in the wild-type strain (6.2 and 4.8 kb, respectively). Alternative models of recombination in which the lengths of conversion tracts are determined by break-induced replication or oversynthesis during strand invasion are proposed to account for these observations.

Keywords: mitotic recombination, DNA repair, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, gene conversion tract length, ultraviolet light

THE 5′–3′ exonuclease Exo1p was first described in Schizosaccharomyces pombe (Szankasi and Smith 1992) and has been extensively characterized in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Tran et al. 2004). Exo1p is involved in multiple cellular pathways, including DNA mismatch repair, telomere processing in response to telomere damage, and DNA lesion bypass. Its most relevant function to the research described below is in the processing of broken DNA ends. Following double-strand break (DSB) formation in meiosis and mitosis, the broken ends are processed by degradation of the 5′ ends. For ends generated in mitosis, this resection process is initiated by removal of a small number of nucleotides by Sae2p and Mre11p/Rad50p/Xrs2p, followed by more extensive resection by two pathways, one involving Exo1p and the other utilizing Sgs1p/Top3p/Rmi1p and Dna2p (Mimitou and Symington 2008; Zhu et al. 2008). Strains lacking Exo1p are still capable of extensive resection of DNA ends, although the rate of resection is slower than in wild-type strains.

The effect of Exo1p on the frequency of meiotic and mitotic recombination has been examined in several studies employing different methods with variable results. Diploids that lack Exo1p have a reduced frequency of meiotic crossovers and reduced gene conversion at some loci (Kirkpatrick et al. 2000; Tsubouchi and Ogawa 2000). The extent and/or rate of end processing are reduced in both meiotic (Tsubouchi and Ogawa 2000; Keelagher et al. 2011) and mitotic (Mimitou and Symington 2008; Zhu et al. 2008) cells. In mitotic cells, loss of Exo1p lowered the frequency of single-strand annealing up to sixfold in some genetic assays (Fiorentini et al. 1997), but had little effect in physical assays of single-strand annealing (Mimitou and Symington 2008; Zhu et al. 2008). Loss of Exo1p elevated the frequency of gap repair as detected in a plasmid assay (Symington et al. 2000; Guo and Jinks-Robertson 2013). Part of this elevation reflects Exo1p-mediated destruction of the transforming plasmid (Guo and Jinks-Robertson 2013). In summary, in most assays of recombination, loss of Exo1p has a relatively small effect, presumably because of the functional redundancy in end processing represented by the Sgs1p/Top3p/Rmi1p and Dna2p pathway. Most previous studies of the effects of the exo1 mutation on mitotic recombination were done using duplicated genes or plasmid–chromosome recombination in haploids. In our analysis, we examine the effects of Exo1p on spontaneous and UV-induced events occurring between homologs in a diploid.

In addition to its role in end resection, Exo1p is involved in expanding the 30-nucleotide gaps that remain following the removal of UV-induced pyrimidine dimers (Giannattasio et al. 2010). Giannattasio et al. proposed that Exo1p (in competition with DNA polymerases that fill in the 30-base gaps) can expand the short gaps to ∼1 kb, triggering the G1/S checkpoint. Below, we show that exo1 strains have reduced levels of UV-induced recombination events.

The frequency and map positions of recombination events were examined in a diploid heterozygous for ∼55,000 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) distributed throughout the genome (Lee et al. 2009). Crossovers and gene conversion events occurring between homologs can be detected as loss of heterozygosity (LOH), using oligonucleotide-containing microarrays (described further below). Some of the patterns of LOH observed in previous studies (St. Charles et al. 2012; St. Charles and Petes 2013; Yin and Petes 2013) are shown in Figure 1.

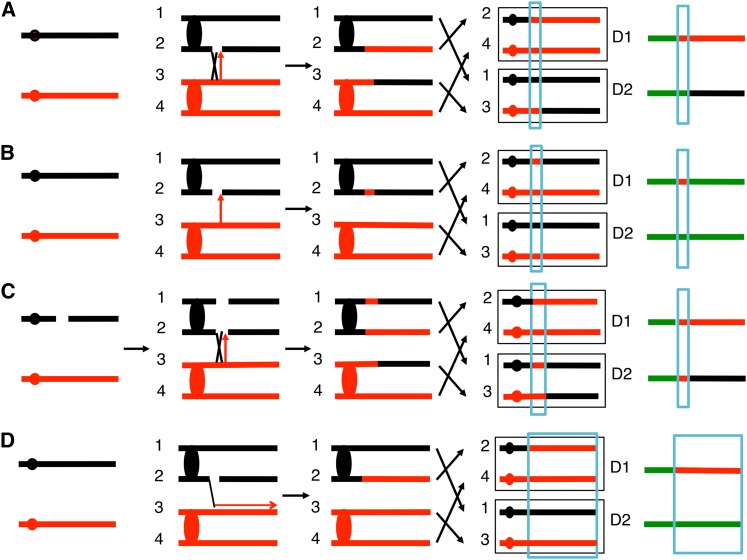

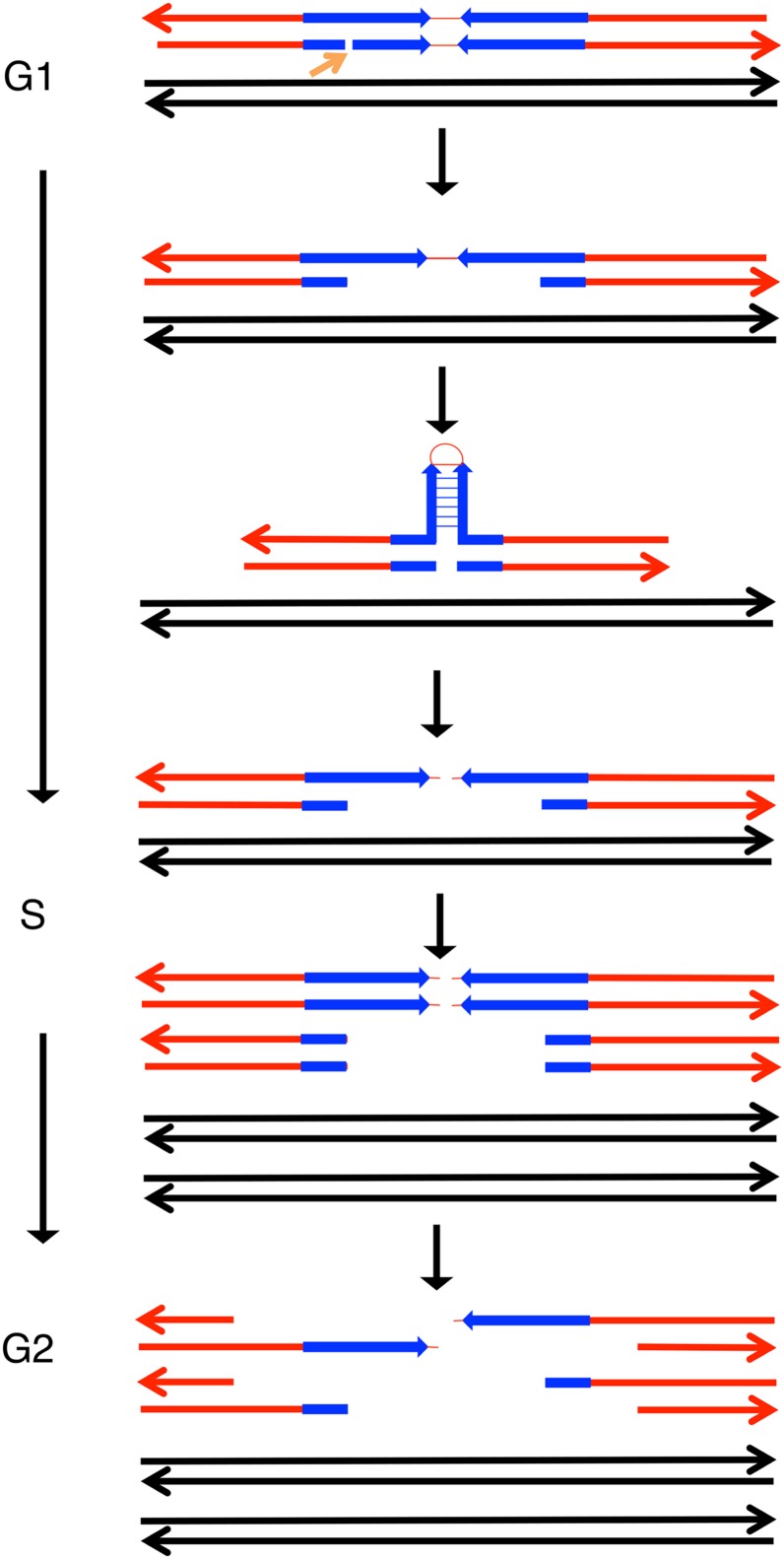

Figure 1.

Patterns of LOH resulting from crossovers, BIR events, and gene conversions. The homologs derived from W303a and YJM789 are shown in red and black, respectively. Ovals and circles indicate centromeres. In A–D, the initiating DSB is on the YJM789-derived homolog. The green, red, and black lines on the right summarize patterns of heterozygosity and homozygosity in the daughter cells after the recombination event. In this depiction, green, red, and black signify heterozygosity, homozygosity for SNPs derived from the W303a homolog, and homozygosity for SNPs derived from the YJM789 homolog, respectively. (A) Crossover initiated with an SCB associated with a 3:1 gene conversion. The blue rectangle outlines the conversion event. (B) Gene conversion (3:1) unassociated with a crossover, initiated by an SCB. (C) Mitotic crossover and an associated 4:0 conversion event. Replication of a chromosome broken in G1 results in two broken sister chromatids. The repair of this DSCB (one repair event associated with a crossover) generates the observed LOH pattern. (D) BIR event initiated by an SCB.

If a single chromatid is broken in S or G2, the resulting crossover leads to LOH from the position of the DSB to the end of the chromosome; the two daughter cells (D1 and D2) have reciprocal patterns of LOH (Figure 1A). Crossovers in mitosis are frequently associated with gene conversion, a region of DNA transferred nonreciprocally between the two homologs (Lee et al. 2009). The conversion tract (outlined in blue in Figure 1) results in the two daughter cells having a switch from heterozygous SNPs to homozygous SNPs at slightly different transition points with the difference defining the length of the conversion tract. Within the boxed region in Figure 1A, since three of the four chromosomes in the daughter cells have the “red” form of the SNP and one has the “black” form, this type of conversion is called “3:1.” Below, we describe 3:1 conversion events as single-chromatid breaks (SCBs), as presented previously (Yin and Petes 2013). As shown in the right side of Figure 1, we can depict the two chromosomes in each daughter cell as a single line with green, red, and black segments indicating heterozygous SNPs, SNPs homozygous for the red allele, and SNPs homozygous for the black allele, respectively.

Figure 1B shows the pattern of interstitial LOH generated by a 3:1 gene conversion unassociated with a crossover. Previously, we found that spontaneous crossovers were frequently associated with 4:0 conversion tracts (Lee et al. 2009; St. Charles et al. 2012; St. Charles and Petes 2013). In this class of events (Figure 1C), both daughter cells have a chromosome region that is homozygous for the same allele (the red allele in Figure 1). This pattern requires the repair of two sister chromatids broken at the same position, and we suggested that chromosome breakage in G1 of the cell cycle, followed by DNA replication, would produce such a situation (Lee et al. 2009). We also observed conversion tracts that contained a 3:1 section adjacent to a 4:0 section (3:1/4:0 hybrid tracts). These hybrid tracts are also likely to represent the repair of two broken sister chromatids with the extent of the repair being different for the two events. Both 4:0 and hybrid tracts are called double-sister chromatid breaks (DSCBs). Among spontaneous crossovers, about two-thirds were DSCBs, and about half of UV-treated cells (15 J/m2 treatment of synchronized G1 cells) had DSCBs. Thus, in S. cerevisiae, a substantial fraction of events that lead to LOH reflect DSCBs rather than breaks made during DNA synthesis (Lee and Petes 2010).

Another pattern of LOH is that produced by break-induced replication (BIR) (Figure 1D). In this mechanism, the chromosome fragment located centromere distal to the break is lost. The end of the centromere-proximal fragment invades the homolog, copying its sequences to the chromosome terminus (Llorente et al. 2008). As a consequence of BIR, one daughter cell has an LOH event extending to the telomere, and the other remains heterozygous.

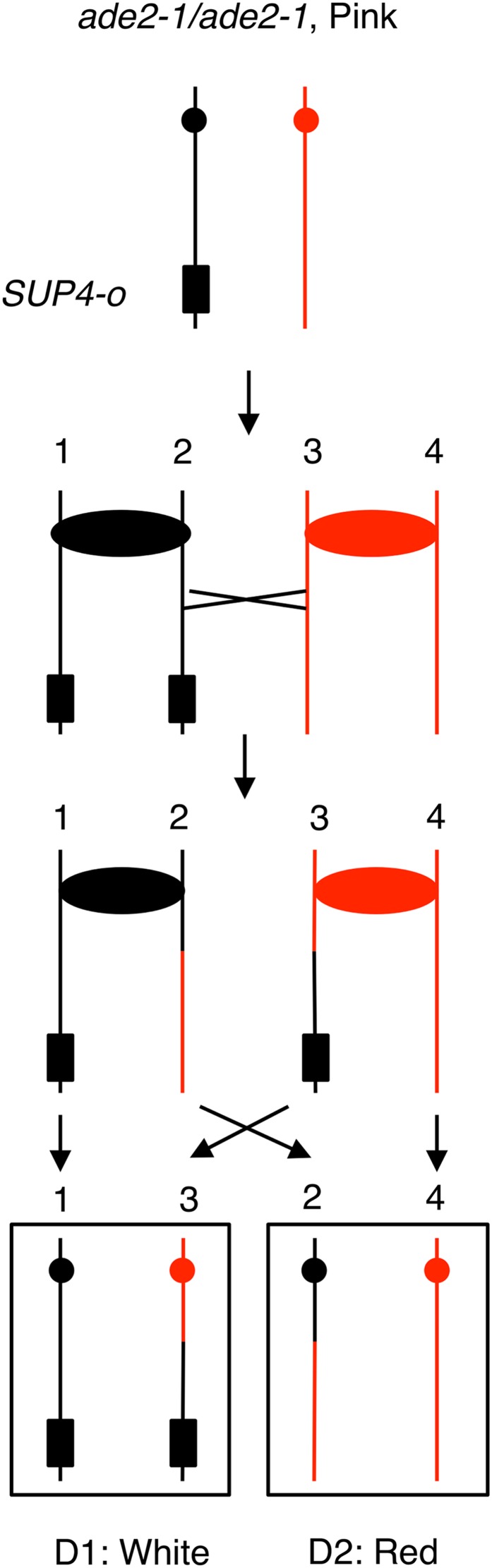

To distinguish among the patterns of LOH shown in Figure 1 and to map the positions of the LOH, we used diploids generated by crossing two sequence-diverged haploids, W303a and YJM789 (St. Charles and Petes 2013; Yin and Petes 2013). This diploid, in addition to being heterozygous for SNPs located throughout the genome, contained markers on either chromosome V (YYy29.8) or chromosome IV (YYy34) that allowed identification of reciprocal crossovers (Figure 2). The diploids are homozygous for ade2-1, an ochre mutation. In the presence of zero, one, and two copies of the ochre suppressor SUP4-o, the diploids form red, pink, and white colonies, respectively (Barbera and Petes 2006). The SUP4-o gene is integrated near the telomeres of chromosomes V (YYy29.8) and IV (YYy34) in the strains used in our study. In these diploids, crossovers between the centromere and the heterozygous SUP-o marker produce red/white sectored colonies. Only half of the crossover events are detectable by this system (Chua and Jinks-Robertson 1991), since cosegregation of two recombined chromosomes into one daughter cell and two unrecombined chromosomes into the other daughter does not lead to LOH.

Figure 2.

Colony-sectoring assay for detecting mitotic crossovers. The diploids in our study are homozygous for the ade2-1 ochre mutation. Diploids with this mutation form red, pink, or white colonies, depending on whether they contain zero, one, or two copies of the SUP4-o ochre suppressor tRNA gene, respectively. In our experiments, the diploids were heterozygous for the SUP4-o that was located near the end of either the left arm of chromosome V or the right arm of chromosome IV. These diploids form pink colonies. However, a crossover between SUP4-o and the centromere results in a red/white sectored colony. Note that only half of the crossovers are detected by the sectoring assay. If chromatids 1 and 4, and 2 and 3, cosegregate, a sectored colony is not formed.

Crossovers identified as red/white sectored colonies were subsequently mapped by SNP microarrays (St. Charles et al. 2012). Each of 13,000 SNPs is represented by four 25-base oligonucleotides, two identical to the Watson and Crick strands of the W303a-derived SNP and two identical to the Watson and Crick strands of the YJM789-derived SNP. If a SNP is heterozygous in genomic DNA isolated from a red or white sector, it will hybridize to the SNP-specific oligonucleotide to about the same extent as a control heterozygous diploid. LOH is detected by an increased ability of the genomic DNA isolated from a sector to hybridize to the SNPs identical to one parental haploid (W303a or YJM789) and a decreased ability to hybridize to the SNPs of the other parental strain (other details in Materials and Methods). This analysis was used to examine spontaneous and UV-induced recombination events in the exo1 diploid, allowing us to define the location of recombination events, the types of gene conversion tracts, and the length distribution of conversion events. We show that the loss of Exo1p reduces the rate of UV-induced, but not spontaneous, recombination events and that the lengths of crossover-associated conversion events are reduced in the exo1 strain. We also show that a hotspot for spontaneous mitotic recombination events associated with very long conversion events in wild-type cells is absent in the exo1 diploid.

Materials and Methods

Strains

Data comparisons from four isogenic diploid strains were used in our study. All strains were derived from crosses of the two sequenced-diverged haploids W303a and YJM789 (Lee et al. 2009) and were deleted for the MATα to allow their G1 synchronization with α-factor. The diploids PG311 and YYy29.8 had a heterozygous SUP4-o marker near the left telomere of chromosome V, and JSC25 and YYy34 had SUP4-o located near the right telomere of chromosome IV. As explained in the text, the SUP4-o marker allows the detection of crossovers.

The wild-type diploid PG311 has the genotype MATa/MATα::NAT ade2-1/ade2-1, can1-100/can1::SUP4-o GAL2/gal2his3-11,15/HIS3leu2-3,112/LEU2RAD5/RAD5trp1-1/TRP1ura3-1/ura3 V9229::HYG/V9229 V261553::LEU2/V261553 (Lee et al. 2009). The exo1 diploid YYy29.8 is isogenic with PG311 except that the MATα gene in the YYy29.8 strain was disrupted with KANMX instead of NAT. The wild-type diploid JSC25 has the genotype MATa/MATα::HYG ade2-1/ade2-1 can1-100::NAT/CAN1::NAT GAL2/gal2his3-11,15/HIS3leu2-3,112/LEU2RAD5/RAD5trp1-1/TRP1ura3-1/ura3 IV1510386::KANMX-can1-100/IV1510386::SUP4-o (St. Charles and Petes 2013). YYy34.2 and YYy34.9 are isogenic exo1 derivatives of JSC25 except that the MATα gene in the YYy34 strains was disrupted with URA3 instead of HYG. The details of the constructions of YYy29.8 and YYy34 are in Supporting Information, Table S6.

Media and genetic methods

Standard YPD media were used for all experiments except for the sectoring assays that utilized MAB6 solid medium (SD-Arg with 10 mg/ml adenine). For the UV-induced sectoring experiments, cells were synchronized in G1 by α-factor as previously described (Lee and Petes 2010). After removing the α-factor, cells were immediately plated on MAB6 plates and irradiated with 15 J/m2 of ∼254 nm UV, using a TL-2000 UV Translinker. The plates were covered with foil to prevent photoreactivation and incubated for 2 days at 30°. To examine the frequency of spontaneous sectors, we suspended single colonies grown on YPD plates in water and then diluted the suspension to a concentration of ∼500–1500 cells per plate. After 3 days of growth on MAB6 solid medium at room temperature, the colonies were screened for red/white sectors. We used standard protocols for transformation and DNA isolation.

SNP microarray analysis

LOH events were analyzed by SNP microarrays as described previously (St. Charles et al. 2012; St. Charles and Petes 2013). These arrays (produced by Agilent) contain four homolog-specific SNPs (W303a or YJM789 specific and Watson or Crick specific) for each of 13,000 SNPs distributed throughout the genome. About 1% of the genome (primarily repetitive regions near the telomere) is not represented on the microarray. The coordinates and sequences of the oligonucleotides on the arrays are described in St. Charles et al. (2012) and St. Charles and Petes (2013). DNA was isolated from each sector as described by St. Charles et al. (2012). The details for labeling DNA samples, hybridizing them to the SNP microarray, and analyzing the resulting hybridization patterns are provided in detail in St. Charles et al. (2012). In brief, DNA from the experimental strain (for example, a white sector) was labeled with Cy5-dUTP, and DNA from the control strain JSC24-2 heterozygous for all SNPs (Yin and Petes 2013) was labeled with Cy3-dUTP. The two samples were mixed and hybridized to the SNP microarray. The microarrays were scanned at wavelengths of 635 and 532 nm, using the GenePix scanner and the GenePix software. The resulting information was exported to text files and examined by R software. The critical data were the ratio of hybridization for the experimental and control samples for each SNP on the array. A ratio of ∼1:1 for the experimental and control samples to the four nucleotides representing a particular SNP indicates heterozygosity. A ratio of ∼1.5:0.2 or 0.2:1.5 indicates LOH for the SNP. For example, if there is an LOH event in which W303a-derived sequences were duplicated, both W303a-specific oligonucleotides would have a high ratio of hybridization compared to the control, and both YJM789-derived oligonucleotides would have a low ratio.

Statistical analyses

Fisher’s exact tests and chi-square tests were done using Excel or the VassarStat Web site (http://vassarstats.net/). The Mann–Whitney test was done using the R “wilcox.test” function. We calculated 95% confidence intervals using table B11 of Altman (1991).

Results

Deletion of EXO1 reduces the level of UV-induced crossovers, but elevates the level of spontaneous crossovers

In previous studies, we measured the frequency of UV-induced crossovers in a wild-type diploid with the SUP4-o gene on chromosome V [PG311 (Yin and Petes 2013)]; the distance between CEN5 and SUP4-o is ∼120 kb. A UV dose of 15 J/m2 resulted in 68 red/white sectored colonies from a total of 7194 colonies (9.5 ± 2.2 × 10−3, ± indicating 95% confidence limits). As discussed above, this frequency represents about half the rate of CEN5-SUP4-o crossovers and is ∼8500-fold higher than the rate observed in untreated cells. The isogenic exo1 diploid YYy29.8 had a sectoring frequency of 5.5 ± 1.9 × 10−3 (32 sectored colonies of 5840 total). This reduction is significant by Fisher’s exact test (P = 0.01). We also measured the frequency of UV-induced sectored colonies in isogenic wild-type (JSC25) and exo1 (YYy34) strains in which the SUP4-o marker was near the telomere of chromosome IV. The frequencies of crossovers in this 1.1-Mb interval were 9.0 ± 2.4 × 10−2 [127 sectored colonies of 1420 total (Yin and Petes 2013)] and 3.6 ± 1.0 × 10−2 (52 sectored colonies of 1465 total) in the wild-type and exo1 strains, respectively. This reduction is significant with a P-value of 0.0001.

Although the absence of Exo1p reduced the frequency of UV-induced crossovers, the rate of spontaneous crossovers was elevated by the exo1 mutation about threefold. On the right arm of chromosome IV, the sectoring frequencies were 3.1 ± 1.0 × 10−5 (55 sectored colonies of 1,761,664) and 1.3 ± 0.5 × 10−4 (23 sectored colonies of 178,055) for the wild-type (St. Charles and Petes 2013) and exo1 mutant strains, respectively. This elevation in frequency by the exo1 mutation is significant (P = 0.0001).

Analysis of classes of LOH events in UV-treated exo1 diploids

To distinguish among the various classes of LOH events (Figure 1) induced by UV (15 J/m2) in the exo1 diploid YYy29.8, we mapped LOH events in both sectors of 16 red/white sectored colonies. We used microarrays that assay LOH for the entire genome, allowing us to diagnose the selected event on the left arm of chromosome V as well as unselected events on other chromosomes. Although screening for red/white colonies excludes the possibility of observing BIR on chromosome V, we can detect BIR for unselected events. In addition to the selected event on V, we observed an average of 4.3 unselected LOH events per sectored colony. This frequency is reduced from that observed in a wild-type diploid irradiated with the same UV dose [8.1 LOH events per colony (Yin and Petes 2013)], as expected from the reduced frequency of selected crossovers described above. In Table S1, we depict all LOH events (selected and unselected) derived from UV treatment of G1-synchronized YYy29.8 cells. Table S2 has the Saccharomyces Genome Database (SGD) coordinates of the transitions between heterozygous and homozygous SNPs for these events.

The numbers of unselected LOH events in the crossover (terminal reciprocal LOH), BIR (terminal nonreciprocal LOH), gene conversion unassociated with a crossover (interstitial LOH), chromosome loss (LOH for one homolog), translocation (terminal duplication or deletion), and interstitial deletion categories are in Table 1 for the wild-type and exo1 strains; data for the wild-type strain are from Yin and Petes (2013). The distribution of crossovers, BIR, and gene conversion events in the two strains are not significantly different (P = 0.77). In Table 1, we also show the numbers of LOH events after correcting for undetectable outcomes (Table 1 legend). If we separate the LOH events into those that involve recombination between homologs and those that do not (chromosome loss, translocations, and interstitial deletions), there are significantly more of the second class in the exo1 strain than in the wild-type strain (P = 0.003).

Table 1. Numbers of different types of unselected LOH events in wild-type and exo1 strains treated with UV.

| Strain (genotype) | CO (corrected) | BIR | Conversions unassociated with CO (corrected) | Chromosome loss | Translocationa | Interstitial deletion | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PG311 (wild type) | 60 (120) | 21 | 300 (240) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 381 |

| YYy29.8 (exo1) | 11 (22) | 5 | 50 (39) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 69 |

We show the different types of unselected LOH events in the sectored colonies treated with 15 J/m2 in G1-synchronized cells. We examined 16 sectored colonies of YYy29.8 and 47 sectored colonies of PG311. The proportions of CO (crossover), BIR, and conversions unassociated with CO do not differ significantly in the exo1 and wild-type strains. As described in the text, only half of reciprocal crossovers are detectable because segregation of two recombined chromosomes into one daughter cell and two unrecombined chromosomes into the other daughter is undetectable. In addition, if there is a gene conversion event associated with the crossover following this type of segregation, it would result in an interstitial LOH event, mimicking a gene conversion. Thus, we correct the number of gene conversion events unassociated with a crossover by subtracting the number expected for “hidden” crossovers.

One of the strains derived from YYy29.8 had an unselected terminal duplication of chromosome I sequences (SGD coordinates 181,850–184,217) from the YJM789-derived homolog and a terminal deletion of chromosome XI sequences (SGD coordinates 576,427–578,510) from the W303a-derived homolog. In our related studies (Argueso et al. 2008; McCulley and Petes 2010), strains with this LOH pattern had nonreciprocal translocations, reflecting a break in one chromosome with loss of the centromere-distal fragment and repair of the centromere-containing portion of the broken chromosome by a BIR event involving a nonhomolog (generating the duplication). Since we did not confirm the existence of a translocation by other methods, our assignment of this event as a translocation is tentative.

As described in the Introduction, the patterns of LOH observed in sectored colonies can usually be classified as events involving one broken sister chromatid (SCB) or two broken sister chromatids (DSCB). One event that cannot be assigned as an SCB or a DSCB is a crossover unassociated with gene conversion. We refer to such events as “simple crossovers.” Based on the patterns shown in Table S1, we show in Table 2 the numbers of simple crossovers and SCB and DSCB events, following UV treatment of the exo1 strain YYy29.8 and the wild-type strain PG311 (Yin and Petes 2013); Table 2 includes both selected and unselected events. The ratio of SCB to DSCB events was not significantly different in the wild-type and exo1 strains (P = 0.07). The number of simple crossovers relative to the other classes, however, was significantly elevated in the exo1 strain relative to wild type (P = 0.0003). This finding is likely related to the shorter conversion events associated with crossovers in the exo1 strain as discussed below.

Table 2. Numbers of simple crossovers and SCB and DSCB events in wild-type and exo1 strains treated with UV.

| Strain (genotype) | Simple crossovers | SCB with CO | DSCB with CO | SCB without CO | DSCB without CO | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PG311 (wild type) | 12 | 35 | 57 | 167 | 133 | 404 |

| YYy29.8 (exo1) | 12 | 10 | 5 | 31 | 19 | 77 |

We summarize selected and unselected events detected by the analysis of the genomes of sectored colonies induced by UV. There were a total of 27 crossovers in YYy29.8, 16 selected crossovers on chromosome V and 11 unselected. Of the 104 crossovers in PG311, 44 were selected on chromosome V and the remainder were unselected. The data for PG311 are from Yin and Petes (2013). The determination of SCB and DSCB events was based on the patterns of gene conversion (Table S1). In general, 3:1 conversions are classified as SCBs and 4:0 or 3:1/4:0 hybrid tracts are classified as DSCBs.

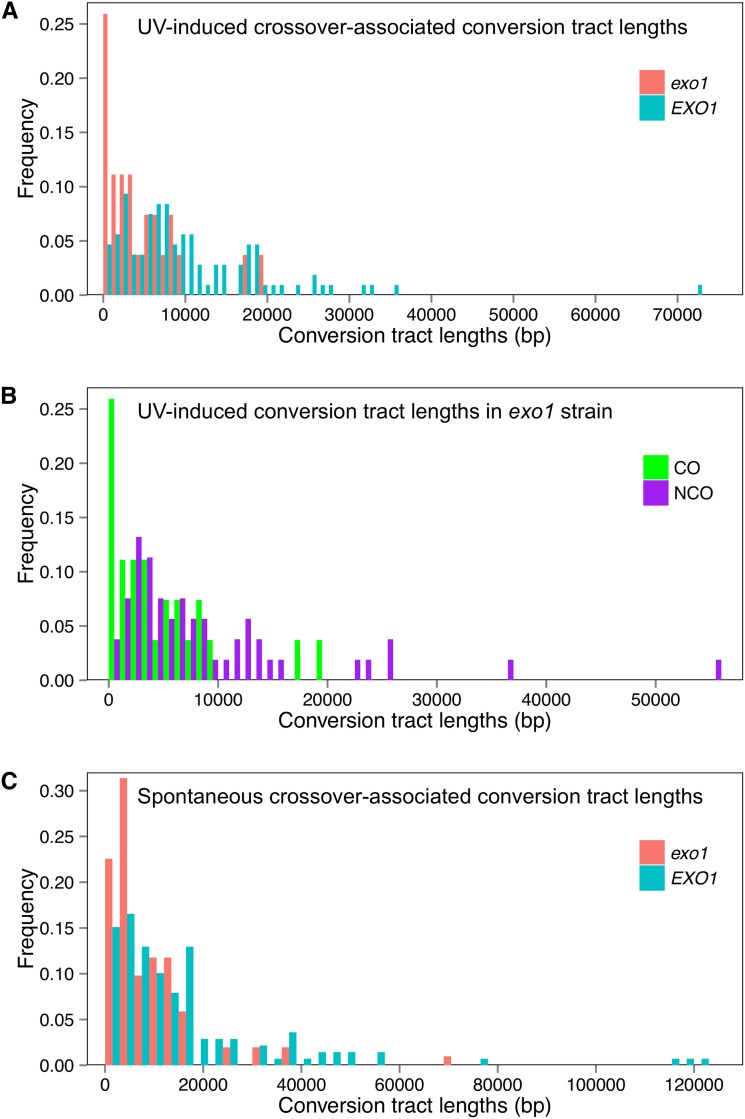

The data of Table S2 can be used to calculate gene conversion tract lengths for the UV-treated strains. For interstitial LOH events, the tract length was calculated as the average of the maximum tract length (the distance between the heterozygous SNPs flanking the LOH region) and the minimum tract length (the distance between the first and last homozygous SNP in the conversion tract). For conversions associated with crossovers, the length was the average between the maximum tract length (the distance between the last heterozygous SNP before the conversion tract and the SNP that has the reciprocal LOH pattern indicative of the crossover) and the minimum length (the distance between the first and last homozygous SNPs of the tract). For crossovers with no detectable conversion, we estimated the length of the conversion tract as half the distance between the heterozygous and homozygous SNPs most closely flanking the crossover transition. The median lengths of the crossover-associated conversions for the wild-type and exo1 strains were 7.6 kb [95% confidence limits of 6.4–9.6 kb (Yin and Petes 2013)] and 3.2 kb (1.3–6 kb), respectively; the P-value for the comparison of these lengths is 8 × 10−5 (Mann–Whitney test). Figure 3A is a histogram of these data.

Figure 3.

Conversion tract lengths in wild-type and exo1 strains. Based on the location of LOH regions, we measured conversion tract length in exo1 strains, both spontaneous events and events induced by UV. These data were compared with measurements performed in wild-type strains (St. Charles and Petes 2013; Yin and Petes 2013). (A) Comparison of UV-induced crossover-associated gene conversion tracts in wild-type and exo1 strains. A total of 107 and 27 conversion tracts were examined in the wild-type and exo1 strains, respectively. (B) Comparison of UV-induced conversion tracts in the exo1 strain. Twenty-seven of the conversion tracts were crossover associated and 54 were unassociated with crossovers. (C) Comparison of spontaneous crossover-associated conversion tracts in wild-type and exo1 strains. One hundred two conversion tracts were analyzed in the exo1 strain and 139 were examined in the wild-type strain.

In previous studies of UV-induced recombination in a wild-type strain, we found that the conversion tracts associated with crossovers were significantly longer than those that were unassociated with crossovers, 7.6 kb (6.4–9.6 kb) and 4.8 kb (4.1–5.6 kb), respectively [P = 1 × 10−6 (Yin and Petes 2013)]. Unexpectedly, in the UV-treated exo1 strain, the conversion tracts associated with crossovers were significantly (P = 0.007) shorter than those unassociated with crossovers, 3.2 kb (1.3–6 kb) and 6.2 kb (3.9–8.5 kb), respectively. Possible explanations for this difference are outlined in the Discussion. Figure 3B is a histogram that shows the distribution of crossover-associated and crossover-unassociated conversion tract lengths in UV-treated exo1 cells.

Analysis of classes of spontaneous LOH events in exo1 diploids

The frequency of spontaneous sectored colonies in the CEN5-SUP4-o interval in wild-type strains is very low, ∼1 × 10−6 (Lee et al. 2009). Consequently, we examined spontaneous LOH events in the exo1 strain YYy34 that has the SUP4-o marker near the end of chromosome IV, allowing detection of events in a 10-fold larger interval. Since unselected spontaneous events are rare (St. Charles et al. 2012), we restricted our analysis to the selected event on IV by using chromosome IV-specific SNP microarrays (St. Charles and Petes 2013). We examined recombination in 102 red/white sectored colonies. The depictions of these LOH events are in Table S3 with the coordinates specifying recombination breakpoints in Table S4.

The numbers of simple crossovers and SCB and DSCB events in YYy34 and the isogenic wild-type strain JSC25 are in Table 3. As observed for the UV-induced events, the ratio of SCBs and DSCBs is not significantly different for YYy34 and JSC25 (P = 0.06), but the ratio of simple crossovers to other events is significantly higher in the exo1 strain (P = 0.01). This difference is consistent with the observation that the crossover-associated conversion tracts in the exo1 strain were about half the size of the conversion tracts in the wild-type strains, 5.5 kb (4.5–7.3 kb) and 10.6 kb [8.2–13.6 kb (St. Charles and Petes 2013)], respectively (P = 3 × 10−5). Short conversion tracts would be less likely to be detected using the SNP microarrays and, therefore, would be expected to result in more simple crossovers. The comparison of the lengths of conversion tracts associated with spontaneous crossovers for the wild-type and exo1 strains is in Figure 3C.

Table 3. Numbers of spontaneous simple crossovers and SCB and DSCB events in wild-type and exo1 strains.

| Strain (genotype) | Simple crossovers | SCB with CO | DSCB with CO | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JSC25 (wild type) | 18 | 31 | 90 | 139 |

| YYy34 (exo1) | 27 | 29 | 46 | 102 |

We summarize the analysis of conversions associated with spontaneous crossovers in JSC25 and YYy34. The data for the wild-type strain are from St. Charles and Petes (2013). The determination of SCB and DSCB events was based on the patterns of gene conversion in Table S3.

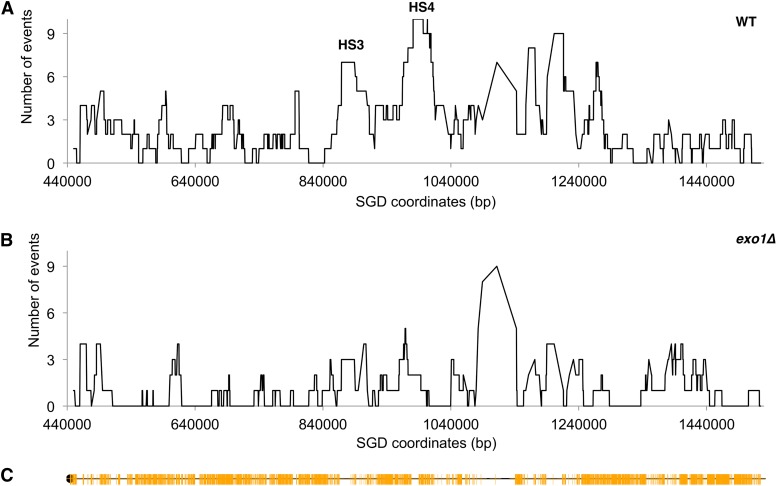

Figure 4 shows the location of spontaneous recombination events on chromosome IV in the wild-type (Figure 4A, data from St. Charles and Petes 2013) and exo1 (Figure 4B) strains. In Figure 4, the y-axis indicates the number of times SNPs on the right arm of chromosome IV were involved in a recombination event, and the x-axis shows the SGD coordinates of SNPs. The peak marked HS4 (hotspot 4) in the wild-type strain is an inverted pair of 6-kb retrotransposons (Ty elements) located between SGD coordinates 981 and 993 kb that is involved in ∼7% of the crossovers in wild type. Recombination at HS4 is significantly (P = 0.02) reduced in the exo1 strain. In addition, there is less recombination at HS3 (a second pair of closely spaced retrotransposons located between SGD coordinates 872 and 884 kb) in the exo1 strain compared to wild type, although this reduction is not statistically significant. Below, we present models that are relevant to the role of Exo1p in generating recombinogenic DNA lesions at HS3 and HS4.

Figure 4.

Distribution of spontaneous crossovers on the right arm of chromosome IV in wild-type and exo1 strains. We show the frequency with which SNPs on the right arm of chromosome IV were involved in a conversion/crossover in the strains JSC25 [wild type (St. Charles and Petes 2013)] and YYy34 (exo1). More than 100 crossovers were mapped in each strain. (A) Crossovers and associated conversions in the wild-type strain. HS3 and HS4 are hotspots for recombination, each containing inverted pairs of Ty elements. (B) Crossovers and associated conversions in the exo1 strain. (C) Location of SNPs used in mapping. Each yellow line shows a SNP position. Note that there is a region of ∼65 kb that contains only one SNP.

Discussion

Our studies show several interesting phenotypes in strains that lack Exo1p, including (1) a reduction of UV-induced crossovers but an elevation in spontaneous crossovers, (2) loss of a spontaneous crossover hotspot caused by inverted retrotransposons, and (3) conversion events associated with crossovers are shorter than those unassociated with crossovers. Each of these properties is discussed below. All of the UV-induced recombination events examined in our study were derived from cells selected to have a crossover on chromosome V. Although we cannot exclude the possibility that the selection of such sectored colonies influences the types of events that we recover in UV-treated cells, the types of spontaneous recombination events analyzed in wild-type strains selected for crossovers on two different homologs (chromosomes V and IV) were very similar (Lee et al. 2009; St. Charles and Petes 2013).

Effect of the exo1 mutation on the rate of UV-induced and spontaneous crossovers

Although loss of Exo1p reduced the frequency of UV-induced crossovers two- to threefold in our assay, the relative frequencies of crossovers, BIR events, and conversions were similar to those observed for wild type (Table 1). In addition, as observed previously for wild-type cells (Yin and Petes 2013), a substantial fraction (about one-third) of the UV-induced conversion events in exo1 strains reflected repair of two sister chromatids broken at approximately the same position (DSCB events). We interpret this result as indicating that high doses of UV in G1-synchronized cells result in recombinogenic DSBs (Yin and Petes 2013). We emphasize that other types of UV-related DNA lesions may be more common than DSBs in unreplicated chromosomes. For example, DNA molecules with single-stranded nicks could be replicated to generate single chromatid breaks (Galli and Schiestl 1999). Such lesions are likely to be responsible for the SCB events that we observed. Based on previous studies (Kadyk and Hartwell 1992), many of the SCB lesions are usually repaired by sister-chromatid recombination, an event that is not detectable by our analysis.

On the basis of previous results (Giannattasio et al. 2010; Ma et al. 2013; Yin and Petes 2013), we proposed several mechanisms by which Exo1p would have a role in production of UV-associated DSBs in G1-synchronized cells (Yin and Petes 2013). One possibility is that the DSB reflects two closely spaced 30-base gaps resulting from removal of dimers on opposite strands. Expansion of one of these short gaps into a longer gap that overlaps with the gap on the opposite strand would result in a DSB. Previously, we calculated that a dose of 15 J/m2 would result in ∼35 closely opposed (≤75 bp) pairs of lesions, assuming a random distribution (Yin and Petes 2013). However, Lam and Reynolds (1987) observed that UV-induced lesions <15 bases apart were observed at a frequency that was higher than expected for a random distribution. By either estimation, there appear to be a sufficient number of closely opposed lesions to generate the observed recombination events.

The reduction in the frequency of UV-induced crossovers in our system in the exo1 mutant could reflect either a reduction in the frequency of recombinogenic lesions or less efficient processing of these lesions into a crossover between homologs. Since all types of recombination events (crossovers, noncrossovers, and BIR events) are reduced by the exo1 mutation by approximately the same extent, we favor the possibility that recombinogenic lesions are reduced by loss of Exo1p, although we cannot rule out the second possibility. The observation that loss of Exo1p reduces, but does not eliminate, mitotic crossovers could reflect redundancy in gap processing by the Sgs1p/Top3p/Rmi1p and Dna2p pathway. Ma et al. (2013) interpreted the reduction in sister-chromatid recombination events observed in UV-treated G2-synchronized exo1rad30 cells as a reduction in recombinogenic lesions; in their experiments, however, they suggested that the recombinogenic lesion was a large single-stranded gap rather than a DSB. In meiosis, Exo1p affects both resection of Spo11p-generated chromosome ends and resolution of double Holliday junctions into crossovers without an effect on noncrossovers (Zakharyevich et al. 2010). Since we see a reduction in crossovers, noncrossovers, and BIR events, the reduction in UV-induced mitotic events is not likely to reflect the same resolution role as observed in meiosis.

In contrast to the reduction in UV-induced crossovers, we observed an elevation in the frequency of spontaneous crossovers in the exo1 strain relative to the wild type. This result argues that Exo1p is not required for processing spontaneous DNA damage into recombinogenic lesions. Because of the multiple cellular roles of Exo1p and the possibly diverse sources of spontaneous DNA damage, we cannot assign a unique explanation for the modest hyper-Rec phenotype. One possibility is that the reduction reflects the role of Exo1p in inhibiting recombination between diverged DNA sequences (Nicholson et al. 2000). Alternatively, since Exo1p mediates an error-free pathway in postreplication repair (Karras et al. 2013), loss of Exo1p could channel more lesions into interhomolog exchanges.

Genomic locations of UV-induced and spontaneous recombination events in exo1 strains

The map positions (SGD coordinates) of UV-induced events in the exo1 strain YYy29.8 are given in Table S2. The events are distributed widely over the chromosomes with no strong hotspots, similar to observations of UV-induced recombination events in wild-type strains (Yin and Petes 2013). All chromosomes have at least one event, and the number of events per chromosome is correlated with the size of the chromosome (r2 = 0.73; P = 0.001). We also analyzed the LOH regions to find out whether various chromosome elements [for example, centromeres, transfer RNA (tRNA) genes, G-quadruplex sequences, etc.] were overrepresented at the breakpoints between the heterozygous markers immediately flanking the LOH regions for conversions unassociated with crossovers and between the heterozygous and homozygous regions for crossovers; these breakpoints are likely to include the regions of the chromosome that underwent the recombinogenic DNA lesion. The details of the analysis are summarized in File S1, and the results are in Table S5. After correction of the P-values for multiple comparisons (Hochberg and Benjamini 1990), none were significant at a value of 0.05.

We also examined the distribution of spontaneous recombination events in the exo1 strain YYy34 on the right arm of chromosome IV. The most obvious difference between the wild-type and exo1 strains in this distribution was the absence of the HS3 and HS4 peaks in the exo1 strain (Figure 4). The HS3 and HS4 hotspots in the wild-type strain have two important properties: they are G1 specific and they involve breakage of the W303a-derived homology (St. Charles and Petes 2013). We found that the W303a-derived homolog has an inverted pair of Ty elements spaced ∼50 bp apart at HS4, whereas the YJM789-derived homolog has only a portion of one Ty element at the allelic position (St. Charles and Petes 2013). Since deletion of one of the Ty elements or increasing the distance between the elements results in loss of HS4 activity in the wild-type strain, we suggested that the recombinogenic effect of HS4 likely reflected formation of a secondary structure in unreplicated DNA (St. Charles and Petes 2013). One mechanism for producing a DSB in G1 is to expand a nick on one strand into a gap, allowing for formation of a “hairpin” on the ungapped strand (Figure 5). Cleavage of the unpaired bases at the tip of the hairpin would result in a G1-specific DSB. The role of Exo1p in this process could be in the formation of the gap and/or the processing of the broken ends to allow invasion of the homolog that lacks Ty elements. An interesting feature of the conversion events associated with HS4 in wild-type strains is that median conversion tract length is ∼50 kb, much larger than that observed for other spontaneous G1 gene conversions [14 kb (St. Charles and Petes 2013)].

Figure 5.

Role of Exo1p in regulating HS4 hotspot activity. The HS4 G1-specific hotspot for spontaneous mitotic recombination contains two closely linked Ty elements. Since deletion of one of the elements or expansion of the distance between the elements results in loss of hotspot activity, we previously suggested that the recombinogenic effects of HS4 likely involve the formation of a hairpin or cruciform structure (St. Charles and Petes 2013). The two Ty elements of HS4 (shown in blue) are present on the W303a-derived homolog (red) but not the YJM789-derived homolog (black). One scenario for production of a DSB in G1 is that a nick on one strand of the inverted repeat (shown by the arrow) is expanded into a gap by Exo1p, allowing formation of a hairpin. A subsequent nick of the sequences at the tip of the hairpin would produce a DSB. The resulting broken ends would require extensive resection (another function of Exo1p) to allow pairing with the YJM789-derived homolog.

We also examined the spontaneous crossovers in the exo1 strain for over- or underrepresentation of chromosome elements (Table S5). Although no element was significantly elevated, we found a significant underrepresentation of tandem repeats in the LOH regions in the exo1 strain. A similar underrepresentation was found previously for spontaneous crossovers in the wild-type strain (St. Charles and Petes 2013). Chromosome IV has 98 different tandem repeats (Tandem-repeat Database; https://tandem.bu.edu/cgi-bin/trdb/trdb.exe?taskid=0) with repeat units varying in size between 1 and 213 bp with the number of repeats per array varying between 2 and 33 copies. It is possible that a subset of these repeats has a chromatin modification or other property that renders them resistant to recombinogenic DNA lesions.

Relationship between resection of DNA ends and the length of conversion tracts

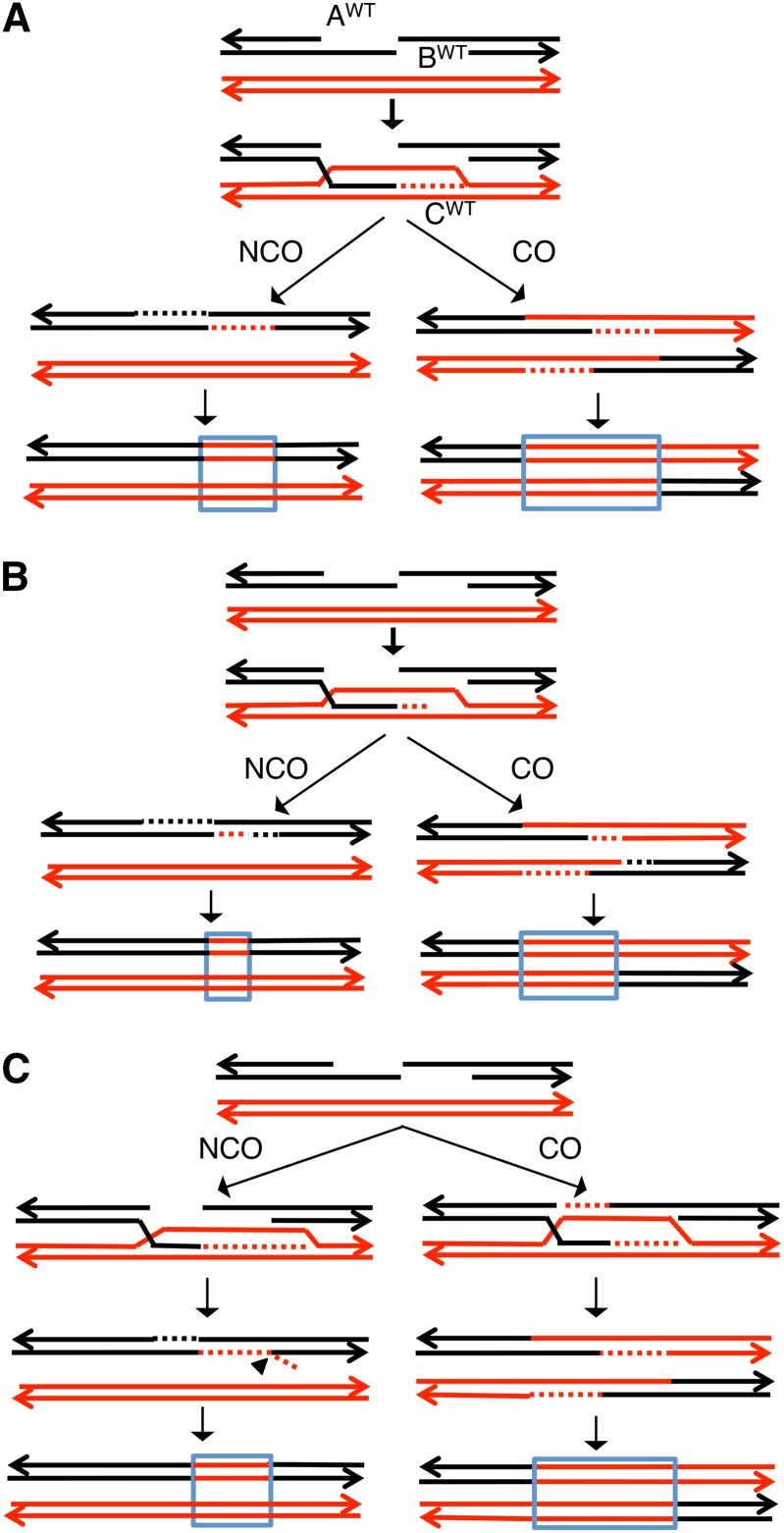

In depictions of the double-strand break repair model, the extent of the gene conversion tract is usually shown as equivalent to the extent of end resection (Figure 6A). For a recombination event in a wild-type strand, we indicate the resection length of the invading chromosome end as AWT and the resection length of the other end as BWT, and the simplest assumption is that AWT = BWT. Further, we hypothesize that amount of DNA synthesized by the invading end (CWT) is equivalent to the resection length. With these assumptions, one would expect that the length of gene conversion tracts unassociated with crossovers would be half of that associated with crossovers. In addition, we would expect both types of conversion tracts would be shorter in the exo1 strain because of less resection. If AWT and BWT are not equal, nonetheless, the conversion tracts unassociated with crossovers would be expected to be shorter than those associated with crossovers.

Figure 6.

Patterns of crossover-associated and crossover-unassociated conversion tracts based on current models of recombination. Black and red lines show DNA strands of the two homologs with arrows marking the 3′ ends. Dotted lines show repair-associated DNA synthesis. For all of the models, we assume that conversion events unassociated with crossovers (NCO) occur as a consequence of SDSA, and events associated with crossovers (CO) reflect resolution of Holliday junctions. We assume that the two broken ends are resected to the same extent (AWT = BWT), although our conclusions do not require this assumption (details in text). CWT shows the length of DNA synthesized by the invading strand. In heteroduplexes with one black strand and one red strand, we show correction of the mismatches to generate two red strands. The resulting conversion tracts are outlined in blue. (A) The length of DNA synthesized by the invading strand (CWT) equals the amount of resection, and AWT = BWT. The expected conversion tract length for events associated with crossovers is about twice that for events unassociated with crossovers. (B) If CWT < AWT and BWT, then the relative length of the crossover-associated tract compared to the crossover-unassociated tract is greater than in A. (C) If CWT > AWT and BWT, one possibility is that, during the SDSA event, the 3′ end of the reinvading strand is displaced. Removal of this end by a branch-processing enzyme such as Rad1p/Rad10p (Mazón et al. 2012) would result in a conversion tract in the NCO pathway that is the same length as in A.

A number of studies have shown that the relationship between end resection and conversion tract length is more complicated than illustrated in Figure 6A. For example, although mre11 strains (which have reduced extents of end resection) have reduced conversion tract lengths in plasmid–chromosome gap-repair assays (Symington et al. 2000; Krishna et al. 2007), conversion tract lengths involving homologs are unaffected by the mre11 mutation (Krishna et al. 2007). In addition, the yku70 mutation, which leads to increased resection, does not result in longer conversion tract lengths in recombination events between homologs (Krishna et al. 2007). Note that the effect of these mutants on resection could be lesion specific (Symington and Gautier 2011). Finally, in studies of plasmid–chromosome recombination in an assay involving 800 bp of homology, Guo and Jinks-Robertson (2013) found that conversion tracts unassociated with crossovers had the same lengths in wild-type and exo1sgs1 strains.

Variants of the model shown in Figure 6A in which the length of DNA synthesized by the invading end is not identical to the length of resection have been recently described (Mazón et al. 2012; Guo and Jinks-Robertson 2013). In Figure 6B, we show a model in which the invading strand disassociates from the template chromosome after synthesizing a segment that is shorter than the gap resulting from resection. By this model, the conversion tracts unassociated with crossovers would be shorter than those associated with crossovers as in Figure 6B, but the lengths of the conversion tracts would not necessarily be affected by the exo1 mutation. This model, however, does not explain our analysis of UV-induced events. In the wild-type strain, the conversion tracts unassociated with crossovers (4.8 kb) are greater than half the size of those associated with crossovers (7.6 kb), and the conversion tracts unassociated with crossovers in the exo1 strain (6.2 kb) are longer than those associated with crossovers (3.2 kb).

It was shown recently that the amount of DNA synthesized from the invading end could exceed the length of the resected gap (Mazón et al. 2012). The subsequent Synthesis-Dependent Strand Annealing (SDSA) event leads to a single-stranded 3′ “tail” that was processed by the Rad1–Rad10 nuclease (Figure 6C). By this mechanism, the extent of the heteroduplex would be regulated by the length of resection as in Figure 6A. Similar to the other models in Figure 6, this model is not consistent with our observations in the exo1 strain. One difference between the experiments of Mazón et al. and our experiments is that the system used by Mazón et al. involves the interactions of ectopic repeats in which flanking heterology limits the size of the conversion tract.

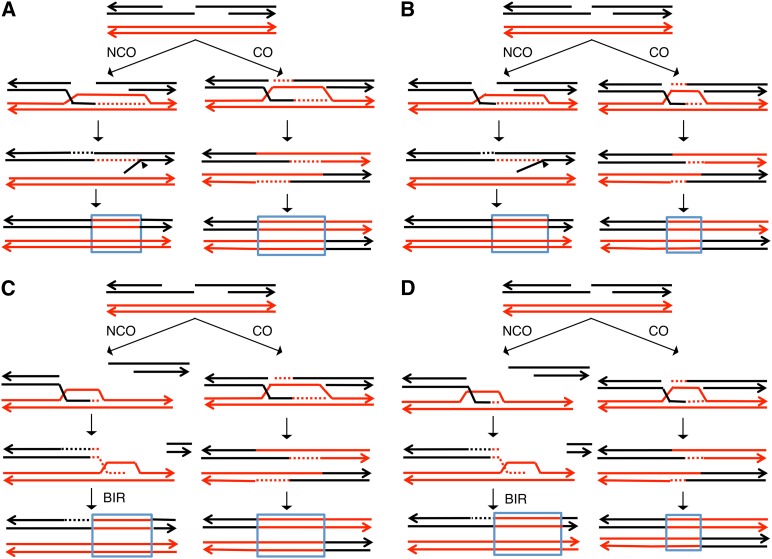

We propose two new models to explain our data (Figure 7). Both require the assumption that the conversion events associated with crossovers are fundamentally different from those unassociated with crossovers. We suggest that the conversion events associated with crossovers are limited by the length of the resection tract, consistent with the observation that the conversion events associated with crossovers in wild type are significantly longer than those observed in the exo1 strain. In contrast, for the models shown in Figure 7, the lengths of the conversion tracts that are unassociated with crossovers are not limited by resection. In the first model (Figure 7A, wild type; and Figure 7B, exo1), the invading strand synthesizes a region of DNA longer than the gap resulting from end processing. When the invading strand is displaced by SDSA, the displaced end reinvades the processed black chromosome, producing a displaced 5′ end. This end could be removed by Rad27p or a related flap-processing enzyme. By this model, the conversion events unassociated with crossovers can be longer than conversions associated with crossovers (Figure 7B). The processing of a 5′ flap was previously proposed as a step in meiotic recombination (Osman et al. 2003), although in this model, the flap was generated during resolution of a recombination intermediate into a crossover rather than as a step in producing a conversion event unassociated with a crossover.

Figure 7.

Two models for the formation of long gene conversion tracts that are unassociated with crossovers. The data that require explanation are (1) crossover-associated conversion events are shorter in the exo1 strain than in wild type and (2) crossover-unassociated conversions are longer than crossover-associated conversions in the exo1 strain. The labels are the same as in Figure 6. The observations can be explained by an oversynthesis model (A and B) or by a BIR model (C and D). (A) UV-induced conversion in the wild-type strain (oversynthesis model). The synthesis from the invading strand is more extensive than the amount of DNA resected in the NCO pathway. The reinvasion during SDSA displaces the 5′ end of invaded homolog, and the resulting single-stranded branch is removed (shown by a triangle). In the CO pathway, the heteroduplex region is limited by resection. (B) UV-induced conversion in the exo1 strain (oversynthesis model). The conversion tract in the NCO pathway is similar to that observed in wild type, whereas the conversion tract for the CO pathway is shorter due to less resection. (C) UV-induced conversion in the wild-type strain (BIR model). In the NCO pathway, the conversion is a consequence of BIR. Following copying of the red chromosome, the invasion is reversed, and the end generated by BIR reassociates with the broken black chromosome. In this model, the conversion tract is not a consequence of repair of mismatches in a heteroduplex. The conversion events in the CO pathway occur by the same mechanism as in A and B. (D) UV-induced conversion in the exo1 strain (BIR model). As in C, the BIR event generating the conversion tract in the NCO pathway is not limited by resection, unlike the conversion tract in the CO pathway.

For the alternative model (Figure 7C, wild type; and Figure 7D, exo1), crossover-associated conversions follow the same pathway as in Figure 7, A and B. The conversions that are unassociated with crossovers, however, are generated by BIR. Following conservative DNA synthesis (Donnianni and Symington 2013; Saini et al. 2013) of a segment of the invaded chromosome, we suggest that the invading DNA molecule dissociates, rejoining the broken end. To be consistent with our data, the length of the conversion tract formed by BIR must be longer than the length of the processed ends. The primary difference between conversion tracts of the two models in Figure 7 is that the tracts shown in Figure 7, A and B, are a consequence of mismatch repair in long heteroduplexes whereas those of Figure 7, C and D, result from conservative DNA synthesis during BIR (Donnianni and Symington 2013; Saini et al. 2013).

Although the suggestion that the heteroduplex regions of crossover-associated and crossover-unassociated conversion events are formed differently may appear problematical, studies of meiotic recombination events in yeast provide a precedent. Meiotic conversion events of the two types are under different genetic regulation (Allers and Lichten 2001; Börner et al. 2004) and involve the resolution of different types of intermediates. In summary, our observations of UV-induced gene conversion events in wild type and exo1 strongly suggest a fundamental difference in mechanisms by which conversion tracts are generated for crossover and noncrossover pathways.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Petes and Jinks-Robertson laboratories for useful discussions and L. Symington, S. Jinks-Robertson, and S. Andersen for comments on the manuscript. This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grants GM24110 and GM52319.

Footnotes

Communicating editor: J. A. Nickoloff

Literature Cited

- Allers T., Lichten M., 2001. Differential timing and control of noncrossover and crossover recombination in meiosis. Cell 106: 47–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman D. G., 1991. Practical Statistics for Medical Research. Chapman & Hall, London/New York. [Google Scholar]

- Argueso J. L., Westmoreland J., Mieczkowski P. A., Gawel M., Petes T. D., et al. , 2008. Double-strand breaks associated with repetitive DNA can reshape the genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105: 11845–11850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbera M. A., Petes T. D., 2006. Selection and analysis of spontaneous reciprocal cross-overs in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103: 12819–12824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Börner G. V., Kleckner N., Hunter N., 2004. Crossover/non-crossover differentiation, synaptonemal complex formation, and regulatory surveillance at the leptotene/zygotene transition of meiosis. Cell 117: 29–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua P., Jinks-Robertson S., 1991. Segregation of recombinant chromatids following mitotic crossing over in yeast. Genetics 129: 359–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnianni R. A., Symington L. S., 2013. Break-induced replication occurs by conservative DNA synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110: 13475–13480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorentini P., Huang K. N., Tishkoff D. X., Kolodner R. D., Symington L. S., 1997. Exonuclease I of Saccharomyces cerevisiae functions in mitotic recombination in vivo and in vitro. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17: 2764–2773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galli A., Schiestl R. H., 1999. Cell division transforms mutagenic lesions into deletion-recombinogenic lesions in yeast cells. Mutat. Res. 429: 13–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannattasio M., Follonier C., Tourriere H., Puddu F., Lazzaro F., et al. , 2010. Exo1 competes with repair synthesis, converts NER intermediates to long ssDNA gaps, and promotes checkpoint activation. Mol. Cell 40: 50–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X., Jinks-Robertson S., 2013. Roles of exonucleases and translesion synthesis DNA polymerases during mitotic gap repair in yeast. DNA Repair 12: 1024–1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochberg Y., Benjamini Y., 1990. More powerful procedures for multiple significance testing. Stat. Med. 9: 811–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadyk L. C., Hartwell L. H., 1992. Sister chromatids are preferred over homologs as substrates for recombinational repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 132: 387–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karras G. I., Fumasoni M., Sienski G., Vanoli F., Branzei D., et al. , 2013. Noncanonical role of the 9–1-1 clamp in the error-free DNA damage tolerance pathway. Mol. Cell 49: 536–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keelagher R. E., Cotton V. E., Goldman A. S. H., Borts R. H., 2011. Separable roles of Exonuclease I in meiotic DNA double-strand break repair. DNA Repair 10: 126–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick D. T., Ferguson J. R., Petes T. D., Symington L. S., 2000. Decreased meiotic intergenic recombination and increased meiosis I nondisjunction in exo1 mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 156: 1549–1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna S., Wagener B. M., Liu H. P., Lo Y.-C., Sterk R., et al. , 2007. Mre11 and Ku regulation of double-strand break repair by gene conversion and break-induced replication. DNA Repair 6: 797–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam L. H., Reynolds R. J., 1987. DNA sequence dependence of closely spaced cyclobutyl pyrimidine dimers induced by UV radiation. Mutat. Res. 178: 167–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee P. S., Petes T. D., 2010. From the Cover: mitotic gene conversion events induced in G1-synchronized yeast cells by gamma rays are similar to spontaneous conversion events. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107: 7383–7388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee P. S., Greenwell P. W., Dominska M., Gawel M., Hamilton M., et al. , 2009. A fine-structure map of spontaneous mitotic crossovers in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS Genet. 5: e1000410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llorente B., Smith C. E., Symington L. S., 2008. Break-induced replication: What is it and what is it for? Cell Cycle 7: 859–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma W., Westmoreland J. W., Resnick M. A., 2013. Homologous recombination rescues ssDNA gaps generated by nucleotide excision repair and reduced translesion synthesis in yeast G2 cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110: E2895–E2904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazón G., Lam A. F., Ho C. K., Kupiec M., Symington L. S., 2012. The Rad1-Rad10 nuclease promotes chromosome translocations between dispersed repeats. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19: 964–971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCulley J., Petes T. D., 2010. Chromosome rearrangements and aneuploidy in yeast strains lacking both Tel1p and Mec1p reflect deficiencies in two different mechanisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107: 11465–11470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimitou E. P., Symington L. S., 2008. Sae2, Exo1 and Sgs1 collaborate in DNA double-strand break processing. Nature 455: 770–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson A., Hendrix M., Jinks Robertson S., Crouse G. F., 2000. Regulation of mitotic homeologous recombination in yeast. Functions of mismatch repair and nucleotide excision repair genes. Genetics 154: 133–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman F., Dixon J., Doe C. L., Whitby M. C., 2003. Generating crossovers by resolution of nicked Holliday junctions: a role for Mus81-Eme1 in meiosis. Mol. Cell 12: 761–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saini N., Ramakrishnan S., Elango R., Ayyar S., Zhang Y., et al. , 2013. Migrating bubble during break-induced replication drives conservative DNA synthesis. Nature 502: 389–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St. Charles J., Petes T. D., 2013. High-resolution mapping of spontaneous mitotic recombination hotspots on the 1.1 Mb arm of yeast chromosome IV. PLoS Genet. 9: e1003434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St. Charles J., Hazkani-Covo E., Yin Y., Andersen S. L., Dietrich F. S., et al. , 2012. High-resolution genome-wide analysis of irradiated (UV and gamma-rays) diploid yeast cells reveals a high frequency of genomic loss of heterozygosity (LOH) events. Genetics 190: 1267–1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symington L. S., Gautier J., 2011. Double-strand break end resection and repair pathway choice. Annu. Rev. Genet. 45: 247–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symington L. S., Kang L. E., Moreau S., 2000. Alteration of gene conversion tract length and associated crossing over during plasmid gap repair in nuclease-deficient strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 28: 4649–4656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szankasi P., Smith G. R., 1992. A DNA exonuclease induced during meiosis of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J. Biol. Chem. 267: 3014–3023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran P. T., Erdeniz N., Symington L. S., Liskay F. M., 2004. EXO1: a multi-tasking eukaryotic nuclease. DNA Repair 3: 1549–1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsubouchi H., Ogawa H., 2000. Exo1 roles for repair of DNA double-strand breaks and meiotic crossing over in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 11: 2221–2233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y., Petes T. D., 2013. Genome-wide high-resolution mapping of UV-induced mitotic recombination events in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS Genet. 9: e1003894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakharyevich K., Ma Y., Tang S., Hwang P. Y., Boiteux S., et al. , 2010. Temporally and biochemically distinct activities of Exo1 during meiosis: double-strand break resection and resolution of double Holliday junctions. Mol. Cell 40: 1001–1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z., Chung W. H., Shim E. Y., Lee S. E., Ira G., 2008. Sgs1 helicase and two nucleases Dna2 and Exo1 resect DNA double-strand break ends. Cell 134: 981–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.