Abstract

Auxin is a key regulator of plant growth and development, orchestrating cell division, elongation and differentiation, embryonic development, root and stem tropisms, apical dominance, and transition to flowering. Auxin levels are higher in undifferentiated cell populations and decrease following organ initiation and tissue differentiation. This differential auxin distribution is achieved by polar auxin transport (PAT) mediated by auxin transport proteins. There are four major families of auxin transporters in plants: PIN-FORMED (PIN), ATP-binding cassette family B (ABCB), AUXIN1/LIKE-AUX1s, and PIN-LIKES. These families include proteins located at the plasma membrane or at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), which participate in auxin influx, efflux or both, from the apoplast into the cell or from the cytosol into the ER compartment. Auxin transporters have been largely studied in the dicotyledon model species Arabidopsis, but there is increasing evidence of their role in auxin regulated development in monocotyledon species. In monocots, families of auxin transporters are enlarged and often include duplicated genes and proteins with high sequence similarity. Some of these proteins underwent sub- and neo-functionalization with substantial modification to their structure and expression in organs such as adventitious roots, panicles, tassels, and ears. Most of the present information on monocot auxin transporters function derives from studies conducted in rice, maize, sorghum, and Brachypodium, using pharmacological applications (PAT inhibitors) or down-/up-regulation (over-expression and RNA interference) of candidate genes. Gene expression studies and comparison of predicted protein structures have also increased our knowledge of the role of PAT in monocots. However, knockout mutants and functional characterization of single genes are still scarce and the future availability of such resources will prove crucial to elucidate the role of auxin transporters in monocots development.

Keywords: IAA, PIN, ABCB, AUX/LAX, PILS, PAT

INTRODUCTION

Plants exhibit an astonishing variety of shapes and develop multicellular bodies able to live for hundreds of years and reach considerable size. They rely on continuous growth and are able to regenerate organs from undifferentiated meristematic cells populations. Plant growth and organ differentiation, as well as response to environmental stimuli, are regulated, among other factors, by endogenous compounds called phytohormones. They control the plant developmental program by regulating cell division and expansion, tissue differentiation, and senescence. Phytohormones can act within the cell of origin or move to other sites in the plant, where they are perceived as a signal by hormone receptors (Davies, 2004).

The plant hormone auxin was first isolated as Indol-3-acetic acid (IAA) by Went (1926), as he studied the tropic response of Avena sativa coleoptiles. Subsequently, during the first half of the twentieth century, other four phytohormones were identified, including abscisic acid, cytokinins, gibberellins, and ethylene (Kende and Zeevaart, 1997). More recently, several additional compounds have been recognized as hormones including brassinosteroids (BR), jasmonate (JA), salicylic acid (SA), nitric oxide (NO), and strigolactones (SLs) (Tarkowská et al., 2014). Auxin is a regulator of many aspects of plant development, including cell division, elongation, differentiation, embryonic development, root and stem tropisms, apical dominance, and flower formation (Young et al., 1990; Woodward and Bartel, 2005; Tanaka et al., 2006; Möller and Weijers, 2009; Leyser, 2010; Müller and Leyser, 2011; Christie and Murphy, 2013; Gallavotti, 2013; Geisler et al., 2014). Besides IAA, which is the most abundant natural form of auxin, several auxin-like molecules have been identified. While 4-chloroindole-3-acetic acid (4-Cl-IAA), indole-3-butyric acid (IBA), and phenylacetic acid (PAA) are all found in plants, 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) and naphthalene-1-acetic acid (NAA) are synthetic compounds that have biological activity similar to IAA (Bertoni, 2011; Simon and Petrášek, 2011).

Local biosynthesis, degradation and conjugation contribute to the modulation of IAA homeostasis at the cellular level. Availability of free IAA inside the cell is also controlled by auxin transport, which occurs in two distinct pathways: a passive diffusion through the plasma membrane (PM) and an active cell-to-cell transport, depending on the protonation state of IAA. IAA is a weak acid with a dissociation constant of pK = 4.8. In a neutral or basic environment IAA- will be the most abundant form (99.4% ionized at pH = 7.0), whereas in the acidic extracellular space IAAH is predominant (about 20% protonated at pH = 5.5) (Delbarre et al., 1996; Estelle, 1998; Kramer and Bennett, 2006). IAAH can enter into the cell through the PM by passive diffusion or active transport by PM importers. Once inside the cytoplasm, which has a neutral pH, IAA- becomes the predominant form and it cannot freely move out of the cell unless actively transported by efflux carrier proteins (Figure 1). The differential localization of transporters at specific sites on the PM creates a directional auxin flow that eventually establishes a polar auxin transport (PAT) stream through adjacent cells. Four classes of auxin transporters have been identified: the PIN-FORMED (PIN) exporters, the ATP-binding cassette (ABC)-B/multi-drug resistance/P-glycoprotein (ABCB/MDR/PGP) subfamily of ABC transporters, the AUXIN1/LIKE-AUX1 (AUX/LAX) importers, and the newly described PIN-LIKES (PILS) proteins.

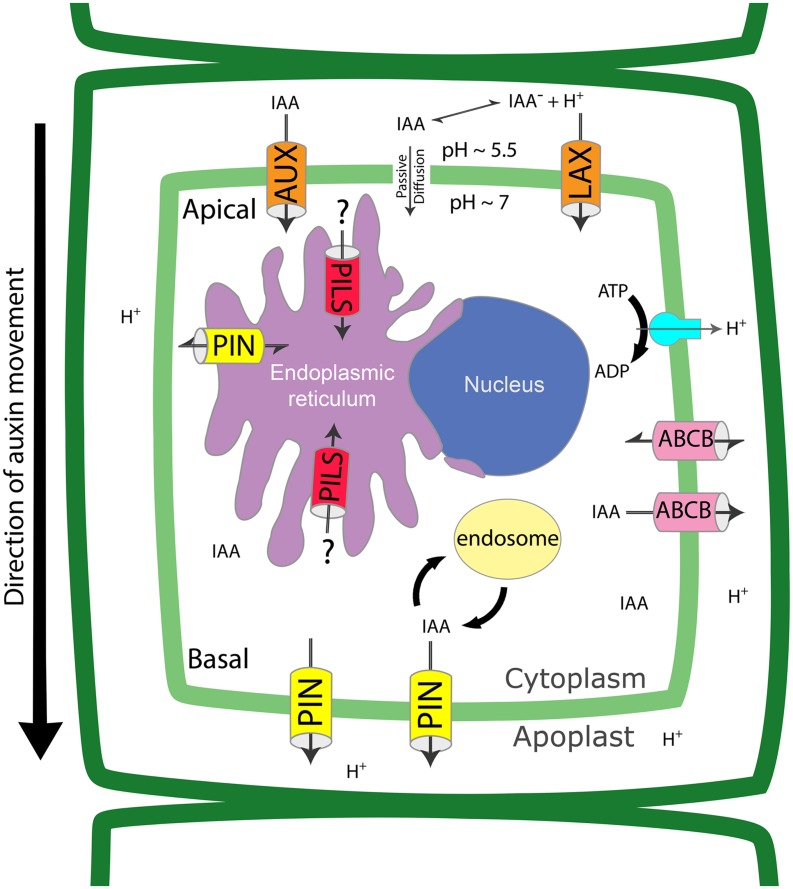

FIGURE 1.

Auxin transport proteins regulate intracellular and cell to cell auxin fluxes. Auxin (IAA) crosses the plasma membrane through passive diffusion, as protonated form, or through PM transporters, as deprotonated form. PINs are efflux carriers located at the PM and ER and can be re-inserted in the lipid bilayer by recycling via the endocytic pathway. AUX/LAXs and PILs are influx carriers located at PM and ER, respectively. ABCBs are located at the PM and use energy from ATP to traslocate IAA. The coordinated localization of the different transporters determines the overall directionality of the auxin flux and contributes to the regulation of intracellular auxin levels.

Despite the fact that auxin was first isolated and studied in the monocot A. sativa, characterization of auxin transport proteins derives mostly from forward genetic studies of mutants with defects in development, organ morphogenesis, and gravitropism in the dicot Arabidopsis thaliana. In recent years, the number of studies on the biological role of PAT in monocots has increased. This has been facilitated by the lower cost of deep sequencing of whole plant genomes and transcriptomes and by the availability of tools such as transgenic lines carrying proteins with fluorescent tags, which are used in subcellular localization studies and PAT fluxes modeling (Mohanty et al., 2009; Egan et al., 2012; Yu et al., 2012). In this work, we present a comprehensive description of monocots auxin transporters and provide, where possible, functional comparison between monocot and Arabidopsis proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

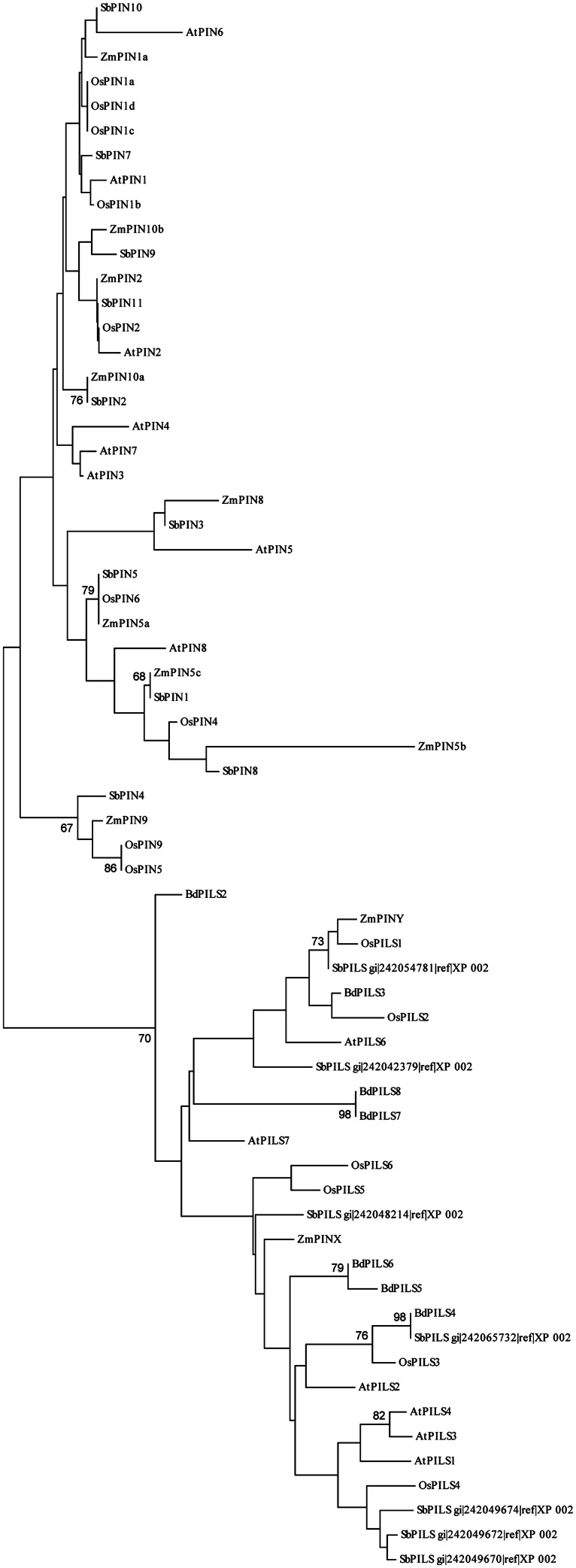

PIN and PILS protein sequences of Arabidopsis, rice, maize sorghum, and Brachypodium (gene accession numbers are listed in Table S1) were aligned using the CustalW 2.0 software (Larkin et al., 2007). The alignment file was used to generate an unrooted tree with MEGA 6.0 (Tamura et al., 2013), applying the Neighbor-joining method, the Poisson model and 500 bootstrap replications. Bootstrap analysis values >60 are indicated at each node.

PINs

PINs are the most studied family of auxin transporters in plants. PIN genes are present in eight copies in Arabidopsis and encode integral membrane proteins with two conserved domains formed by transmembrane helices, typically five at both the N and C termini, and a less conserved central hydrophilic loop of variable length (Křeček et al., 2009; Ganguly et al., 2012). Their subcellular localization has been correlated with the length of the hydrophilic domain. In Arabidopsis, PIN1, -2, -3, -4, and -7 have a longer loop (ranging in size from 298 to 377 amino acid residues), PIN5 and -8 have a shorter loop (27–46 residues) and PIN6 contains an intermediate form (Křeček et al., 2009; Ganguly et al., 2010; Viaene et al., 2013). “Long” PINs are generally inserted into the PM while “short” PINs are located in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and they are thought to contribute to intracellular auxin homeostasis (Mravec et al., 2009; Ding et al., 2012; Cazzonelli et al., 2013). More recently, it has been demonstrated that PIN5 is also PM localized, depending on the cell type and developmental stage, and that PIN5, -6, and -8 function in polar cell-to-cell transport of auxin by regulating coordinated influx and efflux of IAA into and out of the ER (Bender et al., 2013; Sawchuk et al., 2013; Ganguly et al., 2014).

Several auxin transporters show polar localization in the cell, but it is only in the case of PIN proteins that polar targeting occurs more frequently (Figure 1). Shifting PIN polarity results in the alteration of PAT which leads to developmental defects in Arabidopsis (Löfke et al., 2013). The polar localization of PIN proteins is established by cycling between the PM and endosomal compartments such as the trans-Golgi network/early endosomes (TGN/EE). PIN recycling can take place via endocytosis of clathrin-coated vesicles and depends on phosphorylation and ubiquitination (Robert et al., 2010; Kleine-Vehn et al., 2011; Löfke et al., 2013). Unphosphorylated PINs, or those dephosphorylated by the PP2A/PP6 phosphatase, are recycled to the PM by the brefeldin A (BFA)-sensitive ADP-ribosylation factor-guanine nucleotide exchange factor (ARF-GEF) GNOM. Phosphorylation of PIN proteins by the protein kinase PINOID (PID) results in their GNOM-independent recycling to the PM on the opposite side of the cell (Friml et al., 2004; Dhonukshe et al., 2010). Monoubiquitination and subsequent polyubiquitination of PIN proteins induce their endocytosis, followed by trafficking from the TGN/EE to late endosomes, from where the SNX1/BLOC-1 complex mediates transfer to multivesicular bodies (MVBs) for vacuolar degradation (Habets and Offringa, 2014). Recently, another Arabidopsis kinase, D6 PROTEIN KINASE (D6PK), has been demonstrated to regulate PIN phosphorylation and, together with PID, D6PK promotes PINs-mediated auxin transport at the PM by maintaining their phosphorylation status. D6PK PM localization is essential to establish and maintain PIN phosphorylation, and d6pk mutants have defects in both negative gravitropism and phototropism due to impaired auxin transport (Zourelidou et al., 2009; Willige et al., 2013; Barbosa et al., 2014).

Phylogenetic studies on the origin and evolution of PIN proteins have demonstrated that their general structure is highly conserved across the plant kingdom and suggest that the last common ancestor of land plants had at least one “long” (canonical) PIN protein (Carraro et al., 2012; Bennett et al., 2014). Strong selective pressure maintained PINs function as auxin carriers while they underwent sub- and neo-functionalization with substantial modification to protein structure, possibly due to selective loss of phosphorylation sites in their central loop (Dhonukshe et al., 2010; Fozard et al., 2013; Bennett et al., 2014). This generated several clades of non-canonical proteins with shorter and divergent structure, leading to altered localization and biological function. Monocot PIN families are often enlarged due to whole genome duplications and the retention of multiple copies of similar proteins. Both Oryza sativa and Zea mays contain four PIN1 copies and present at least one monocot-specific gene, PIN9, which is divergent in sequence and expression pattern from the closest dicot PINs (Xu et al., 2005; Forestan et al., 2012; Bennett et al., 2014; Clouse and Carraro, 2014). The PIN9 protein profile prediction shows an intermediate hydropathic profile in between the “long” and the “short” PINs.

AtPIN1 is expressed early during embryonic development and later both in the primary root and in the inflorescence stem. Disruption of AtPIN1 expression leads to the formation of naked, pin-shaped inflorescences and abnormalities in the number, size, shape, and position of lateral organs (Okada et al., 1991; Gälweiler et al., 1998). As suggested by the pin1 phenotype, PIN1 plays an important role in establishing the plant developmental plan and is involved in floral bud formation, phyllotaxis (the arrangement of leaves and flowers around the stem), vascular development, vein formation, embryogenesis, lateral organ formation, anther development, and root negative phototropism (Gälweiler et al., 1998; Benková et al., 2003; Reinhardt et al., 2003; Weijers et al., 2005; Feng et al., 2006; Scarpella et al., 2006; Lampugnani et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2014). Arabidopsis pin2 was the first pin mutant identified in a screen for agravitropic seedlings by Bell and Maher (1990). Initially, it was called agr1, and the gene responsible for the phenotype was cloned independently by four research groups and named AGR1/EIR1/PIN2/WAV6 (Chen et al., 1998; Luschnig et al., 1998; Müller et al., 1998; Utsuno et al., 1998). AtPIN2 functions in auxin-regulated root gravitropic response and its expression levels and polar cellular localization are altered by salt stress (Abas et al., 2006; Sun et al., 2008). AtPIN3 is expressed during embryo development and the Atpin3 mutant shows reduced growth, and decreased apical hook formation (Friml et al., 2002b; Zádníková et al., 2010). It has been shown that AtPIN3 plays an important role in root gravitropism, as in vertically grown seedlings AtPIN3 is positioned symmetrically at the PM in the columella cells, but rapidly re-localizes laterally to the lower PM of the statocytes following gravistimulation. AtPIN3 relocalization determines the direction of the auxin flux, which leads to asymmetric auxin accumulation and subsequent differential cell growth (Friml et al., 2002b). AtPIN3 is also involved in root negative phototropic response, as blue-light induced AtPIN3 polarization is needed for asymmetric auxin distribution (Zhang et al., 2013).

AtPIN4, as well as AtPIN7, are involved in auxin controlled embryo, primary root, and apical hook development (Friml et al., 2002a, 2003; Vieten et al., 2005; Kleine-vehn et al., 2010; Zádníková et al., 2010). AtPIN7 also undergoes relocalization similar to AtPIN3 in response to gravistimulation in a subgroup of the columella cells (Rosquete et al., 2013). AtPIN5 is involved in auxin homeostasis, and it has been demonstrated that it can export auxin from yeast cell (Mravec et al., 2009). AtPIN6 is involved in stamen development, and microarray and reporter assays have demonstrated that it is necessary for nectaries development (Bender et al., 2013). Expression analysis of pPIN6::PIN6-GFP lines during leaf development has demonstrated that AtPIN6 localizes to the ER and expression is initiated in broad sub-epidermal domains that later on narrow to sites of vein formation (Bender et al., 2013; Sawchuk et al., 2013). Moreover, AtPIN6 is implicated in processes such as shoot apical dominance, lateral root primordia development, adventitious root formation, root hair outgrowth, and root waving where it regulates auxin homeostasis (Cazzonelli et al., 2013). AtPIN8 is expressed in the male gametophyte, and has a crucial role in pollen development and functionality (Ding et al., 2012). AtPIN8, together with AtPIN5 and AtPIN6, also take part into leaf vein network patterning by regulating intracellular auxin transport between the cytoplasm and the ER lumen. Their action is exerted coordinately with AtPIN1, in order to modulate intracellular auxin levels in extending veins (Sawchuk et al., 2013).

PINs IN Oryza sativa

Rice has 12 PINs (Table S1) and OsPIN1 was first described by Xu et al. (2005). Transmembrane motif analysis of the deduced amino acid sequence shows that OsPIN1 is a “long” (canonical) PIN protein, which harbors a long hydrophilic loop and two transmembrane regions composed of five helices each. Protein structure, phylogenetic, and functional analysis identify OsPIN1 as the closest ortholog of AtPIN1 (Xu et al., 2005; Carraro et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2014a). The three OsPIN1s, -a, -b, and -c are expressed in roots, stem base, stem and, at a lower level, in leaves and young panicles. In these last two organs, OsPIN1c expression is lower than in the other tissues (Xu et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2009). Over-expression of OsPIN1 in 35S::OsPIN1 transgenic plants increases primary root length and lateral root number. Suppression of OsPIN1 expression obtained by RNA interference (RNAi) reduces the number of adventitious roots and increases the number of tillers and the tiller angle. Thus, OsPIN1 is involved in auxin transport in primary and adventitious roots, which are more abundant in rice compared to Arabidopsis. The role of OsPIN1 in PAT was confirmed by treating wild type plants collars with 1-N-Naphthylphthalamic acid (NPA), which blocks initiation and growth of adventitious and lateral roots, while application of the auxin NAA rescues the RNAi-induced phenotype (Xu et al., 2005). OsPIN2 is the most recently characterized PIN gene of rice and shows a different expression pattern compared to OsPIN1 (Chen et al., 2012). Wang et al. reported that OsPIN2 is highly expressed in roots and at the base of the stem, less in young panicles and exhibits no expression in adult stem and leaves (Wang et al., 2009). Over-expression of OsPIN2 results in a larger tiller angle, reduced plant height and an increase in tillers number compared to wild type. OsPIN2 over-expression increases auxin transport from the shoot to the root–shoot junction and transgenic plants are less sensitive to root growth inhibition by NPA (Chen et al., 2012). Overall, the results indicate that OsPIN2 acts in a specific auxin-dependent pathway which includes OsPIN1b and OsTAC1 (TILLER ANGLE CONTROL 1), and controls rice shoot rather than root architecture (Chen et al., 2012). Three OsPIN5 homologs are present on chromosomes 1, 8, and 9 of rice. The expression patterns of OsPIN5a and OsPIN5c are very similar: while only weakly expressed in roots, they show very high expression levels in leaves, shoot apex, and panicle. Small amounts of OsPIN5b transcript are detected in the shoot apex, roots of 6-week-old plants and 4-week-old callus tissue (Wang et al., 2009; Miyashita et al., 2010). One AtPIN8 homolog has been identified in rice but it has not been characterized yet (Miyashita et al., 2010). OsPIN9 is highly expressed in adventitious root primordia and pericycle cells at the base of the stem (Wang et al., 2009). OsPIN9 expression levels in roots are decreased by IAA and increased by cytokinin [6-benzylaminopurine (6-BA)] application (Wang et al., 2009; Shen et al., 2010). Expression analysis shows that OsPIN10a is present in the stem, leaves, and young panicle, but not in the roots. OsPIN10b is mainly expressed in leaves but also at the stem base and in lateral root primordia and both genes are up-regulated by IAA, 6-BA, and JA treatments (Wang et al., 2009).

PINs IN Zea mays

The PIN family in maize includes 12 members characterized by often overlapping but sometimes organ-specific expression domains (Forestan et al., 2010). ZmPINs consist of both “long” (ZmPIN1a, -b, -c, -d, ZmPIN2, ZmPIN10a, -b) and “short” forms (ZmPIN5a, -b, -c, ZmPIN8), with ZmPIN9 having a protein structure in between the two classes (Forestan et al., 2012; Table S1). The ZmPIN1 homologs were among the first identified in maize and are expressed at the PM, supposedly functioning in PAT at different stages of plant development. The ZmPIN1a, -b, and -c loci are located in duplicated regions on chromosomes 9, 5, and 4, respectively, and, along with ZmPIN1d, are characterized by a six exons/five introns gene structure. This gene organization is similar to that of AtPIN1 and OsPIN1. The proteins encoded by ZmPIN1a, -b, -c, and -d present higher sequence similarity to AtPIN1 than other PINs from Arabidopsis and they should be considered as different orthologs of AtPIN1. In monocot species such as maize, the presence of paralogs encoding protein isoforms derived from duplication and neo-functionalization cannot be ruled out, but so far there is no conclusive evidence in the case of ZmPINs. ZmPIN1a, -b, -c are ubiquitously expressed but differentially modulated in maize vegetative and reproductive tissues and during kernel development. ZmPIN1 plays an important role during embryogenesis, where detectable hormone activity inside the developing maize embryo appears much later than in Arabidopsis (Forestan et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2014). In situ hybridization showed that ZmPIN1a localizes in the root apical meristem (RAM) and the calyptrogen, which is a specialized layer of meristematic cells that continuously generate replacements for the root cap cells that die during primary root growth. Immunolocalization experiments locate ZmPIN1 in the central cylinder, vasculature, and cortex of the primary root (Carraro et al., 2006; Forestan et al., 2012). NAA application to a ZmPIN1a-YFP reporter line causes a more diffuse localization of ZmPIN1a and leads to changes in root anatomy, reducing the size of both root cap and meristem and developing of a pluristratified epidermis (Forestan et al., 2012). ZmPIN1a also interacts with KNOTTED1 (KN1) in shaping leaves and leaf veins patterns and regulates PAT during ear, tassel, and spikelet differentiation (Carraro et al., 2006; Gallavotti et al., 2008; McSteen, 2010; Bolduc et al., 2012). ZmPIN1a was shown to rescue the Atpin1 phenotype and the application of NPA to plants at different stages of development leads to PAT disruption related defects (Gallavotti et al., 2008; Gallavotti, 2013). ZmPIN1b is mainly expressed in the epidermis, root cap, and vasculature. ZmPIN1c localizes in the epidermis and vasculature of the root central cylinder, while ZmPIN1d is specifically expressed in the tassel, ear, and in the fifth node of adult plants. ZmPIN1d is also expressed in the L1 layer of the shoot apical meristem (SAM) and inflorescence meristem during the transition to flowering (Forestan et al., 2012). ZmPIN2 is expressed in the root tip, male and female inflorescences and is involved in kernel development (Forestan et al., 2012). Interestingly, ZmPIN2 is up-regulated in the roots of the brachytic2 mutant, which is characterized by reduced shoot-ward auxin transport at the root apex and reduced root gravitropic growth (McLamore et al., 2010). ZmPIN5a is highly expressed in roots and ZmPIN5b is expressed in the 5th node of the stalk. ZmPIN8 is up-regulated during the early phase of kernel development and in the 7th and 8th internodes. ZmPIN9 is expressed in the root epidermis and pericycle and NAA treatment increases its transcript levels in the root segment just before the root apex. There are two PIN10 homologs in maize, ZmPIN10a and ZmPIN10b. Both genes are expressed in the male inflorescence, with ZmPIN10a also up-regulated during the early phases of kernel development (Forestan et al., 2012).

PINs IN Sorghum bicolor

In Sorghum bicolor, PINs have been identified and their expression pattern described, but results from functional analysis are still missing (Shen et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2011). The nomenclature for sorghum PIN genes does not match the one followed for Arabidopsis, rice, and maize therefore, we include the gene identifier together with the common name (Table S1). In sorghum, “long” PIN proteins have a conserved canonical architecture, with two hydrophobic domains divided by a hydrophilic loop (Zazímalová et al., 2007; Shen et al., 2010). Their chromosomal distribution, expression profile and up- or down-regulation following treatment with auxin transport inhibitors [NPA, 1-naphthoxyacetic acid (1-NOA) and 2,3,5-triiodobenzoic acid (TIBA)] have been described (Shen et al., 2010). The SbPIN1 (Sb02g029210) transcript, similar to ZmPIN5c, is predicted to localize to the tonoplast and to be constitutively expressed in all tissues (Shen et al., 2010). SbPIN2 (Sb03g029320), one of the sorghum proteins predicted to be located at the PM, shows high sequence similarity to ZmPIN10a. SbPIN3 (Sb03g032850), similar to At/Os/ZmPIN8, is highly expressed in flowers (Shen et al., 2010). SbPIN4 (Sb03g037350) is the sorghum gene that shares most similarity with ZmPIN9 and it is also highly expressed in roots, although not exclusively (Shen et al., 2010). However, its expression is down-regulated by IAA application and increased by BR, while ZmPIN9 is up-regulated by auxin treatments (Shen et al., 2010; Forestan et al., 2012). SbPIN5 (Sb03g043960), similar to Zm/OsPIN5a, is expressed at low levels in untreated plants while IAA treatment suppresses expression in leaves and roots (Shen et al., 2010). The gene named SbPIN6 (Sb04g028170) encodes a “long” form similar to PIN1 proteins (Wang et al., 2011). The gene named SbPIN8 (Sb07g026370) is the most similar to ZmPIN5b having a predicted protein structure of a “short” PIN (Shen et al., 2010). Protein sequence alignment and expression pattern of SbPIN9 (Sb10g004430) suggest homology to ZmPIN10b. The SbPIN11 (Sb10g026300) sequence is orthologous to Zm/OsPIN2 and is more expressed in roots and seedling shoots.

PINs IN Brachypodium distachyon

In the genome of the grass Brachypodium distachyon there are both “long” and “short”/“intermediate” PIN forms (Bennett et al., 2014; O’Connor et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2014a). Two PIN1 paralogs have been identified: BdPIN1a (Genebank ID XM_003563990.1) and BdPIN1b (Genebank ID XM_003570618.1). BdPIN1a and BdPIN1b are highly expressed in internal tissues, with BdPIN1b spanning a broader domain. Transgenic Brachypodium lines carrying pPIN1a:PIN1a-YFP and pPIN1b:PIN1b-YFP constructs show expression in developing spikelets, suggesting a role in vascular patterning (O’Connor et al., 2014). The newly identified “Sister-of-PIN1” (SoPIN1)/PIN11 clade contains Brachypodium genes that are divergent in sequence from BdPIN1s and have no representatives in Brassicaceae. SoPIN1 is highly expressed in the stem epidermis and is consistently polarized toward regions of high expression of the DR5 auxin-signaling reporter, which suggests a role in the localization of new primordia (O’Connor et al., 2014).

ABCBs

The ABC superfamily of membrane proteins includes more than a hundred different members in plants (Kang et al., 2011). The subfamily B (ABCB) includes homologs of the mammalian MDRs/PGPs, several of which are involved in auxin transport (Geisler and Murphy, 2006; Cho and Cho, 2013). ABCB transporters are integral membrane proteins that actively transport chemically diverse substrates across the lipid bilayers of cellular membranes (Figure 1). The core unit of a functional ABC transporter consists of four domains: two nucleotide-binding domains (NBDs) and two transmembrane domains (TMDs). The two NBDs unite to bind and hydrolyze ATP, providing the driving force for transport, while the TMDs are involved in substrate recognition and translocation across the membrane (Jasinski et al., 2003; Higgins and Linton, 2004; Bailly et al., 2011). Arabidopsis has 22 ABCBs and the first ABCBs characterized as functioning in IAA traslocation were identified in seedlings (Sidler et al., 1998; Noh et al., 2001). ABCB1, ABCB4, ABCB14, ABCB15, ABCB19, and ABCB21 are associated with auxin transport, although not exclusively (Geisler and Murphy, 2006; Titapiwatanakun and Murphy, 2009; Kaneda et al., 2011; Kamimoto et al., 2012; Cho and Cho, 2013). To date, the best-characterized ABCBs are AtABCB1, AtABCB4, and AtABCB19. They all function in auxin driven root development and require the activity of the immunophilin TWISTED DWARF1 (TWD1)/FKBP42 to be correctly inserted at the PM (Wu et al., 2010). AtABCB1/PGP1 was the first plant MDR-like gene cloned from Arabidopsis and it is localized at the PM in the root and the shoot apex of seedlings (Dudlers and Hertig, 1992; Noh et al., 2001). The Atpgp1 original mutant exhibits only a subtle phenotype compared to wild type plants, but a new allele designated as atpgp1-2, shows a shorter hypocotyl and dwarf phenotype under long-day conditions (Geisler et al., 2005; Ye et al., 2013). Disruption of AtABCB19/AtMDR1 expression results in partial dwarfism and reduced PAT in hypocotyls and inflorescences (Noh et al., 2001). AtABCB19 functions together with AtABCB1 in long distance transport of auxin along the plant main axis in coordination with AtPIN1, and regulates root and cotyledon development and tropic bending response (Lin and Wang, 2005; Bandyopadhyay et al., 2007; Rojas-Pierce et al., 2007; Nagashima et al., 2008; Lewis et al., 2009; Christie et al., 2011). AtABCB4 is a root-specific transporter involved in auxin transport during root gravitropic bending, root elongation, and lateral root formation (Santelia et al., 2005; Terasaka et al., 2005; Kubeš et al., 2011; Cho et al., 2012). This transporter is substrate-activated and functions as an auxin importer at low substrate concentration, switching to auxin export as the availability of auxin increases (Yang and Murphy, 2009; Kubeš et al., 2011). AtABCB21 encodes a protein that is the closest homolog to AtABCB4 and is expressed in the aerial parts of the seedling and in the root pericycle cells. Just like AtABCB4, AtABCB21 functions as a facultative importer/exporter that controls cellular auxin levels (Kamimoto et al., 2012). AtABCB14 was first described as a malate importer that functions in the control of stomata aperture according to CO2 levels (Lee et al., 2008). More recently, AtABCB14 and 15 have been shown to be active in the vascular tissue of the primary stem, which shows anatomical alterations in abcb14 and abcb15 mutants. Since IAA transport along the inflorescence is reduced in both mutants, it was proposed that AtABCB14 as well as AtABCB15 participate in auxin transport (Kaneda et al., 2011).

ABCBs IN Oryza sativa

Homologs of ABCBs have been described in monocots. In rice, Garcia et al. identified 24 putative ABCB sequences, with OsABCB22 and OsABCB14/16 being homologs of AtABCB19 and AtABCB1, respectively (Garcia et al., 2004; Knöller et al., 2010). OsABCB14 is expressed in all plant organs, including roots, stem, leaves, nodes, root-stem transition region, filling seeds, panicle, and flowers (Xu et al., 2014). Spatial expression analysis shows that OsABCB14 expression is higher in root tips than in the basal root zone. Knockout mutants of OsABCB14 have decreased PAT rates, conferring insensitivity to 2,4-D and IAA. A role for OsABCB14 in auxin uptake and iron (Fe) homeostasis has been demonstrated. Acropetal auxin transport in rice abcb14 plants root system is significantly lower than in wild type. The iron concentrations in shoots, roots, and seeds are significantly enhanced, and the expression level of iron deficiency-responsive genes was significantly upregulated in rice abcb14 mutants (Xu et al., 2014). Recent evidence also suggests that N-glycosylation of ABCB proteins in rice might be important for root development. In an EMS-generated mutant line for OsMOGS, which encodes a mannosyl-oligosaccharide glucosidase, root PAT is altered due to under-glycosylation of OsABCB2 and OsABCB14 (Wang et al., 2014b).

ABCBs IN Zea mays AND Sorghum bicolor

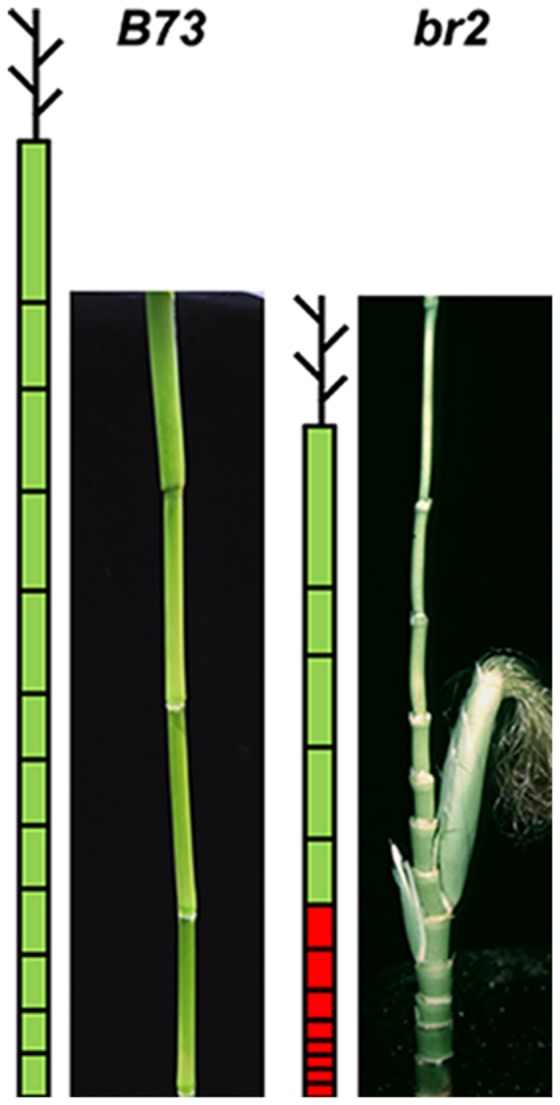

In maize and sorghum, loss-of-function mutations in the AtABCB1 orthologous genes ZmABCB1 and SbABCB1 result in short stature plants designated as brachytic2 (br2) and dwarf3 (dw3), respectively (Multani et al., 2003). br2 and dw3 are characterized by reduced basipetal auxin transport and greatly reduced stalk height (Multani et al., 2003). BR2 is expressed in nodal meristems, and analyses of auxin transport and content indicate that BR2 function in monocot-specific meristems is the same as that of AtABCB1, which is an auxin transporter. Thus ABCB1/BR2 auxin transport ability is conserved between dicots and monocots, but should be considered in the context of distinct architectures of monocot versus dicot plants, which have unsegmented (Arabidopsis) and segmented stems (maize, rice, sorghum, Brachypodium) (Figure 2; Multani et al., 2003; Knöller et al., 2010). The dwarfing phenotype of dw3 is very similar to that of br2 and it is the result of a 882-bp tandem duplication in exon 5 that disrupts protein function and the plant’s ability to establish an auxin flux in the intermediate internodes (Multani et al., 2003). These mutants are of particular interest because of the agronomic importance in terms of their ability to resist to lodging and to dramatically enhance the harvest index of the plant. Thus dwarfing traits are important due to the potential distribution of nutrients and energy to grain production rather than vegetative growth. Given that br2, which has a defect in ZmABCB1, causes the stunting of lower internodes mostly, it raises the possibility that other brachytic mutants may arise from defects in other ABCB transporters. In maize, there are three putative AtABCB19 homologs: ZmABCB10-1 (GRMZM2G125424) and ZmABCB2-1 (GRMZM2G072850), present closest sequence similarity to OsABCB16, while ZmABCB10-2 (GRMZM2G085236), is more similar to the true auxin transporter OsABCB14 (Knöller et al., 2010). ZmABCB10-1 (GRMZM2G125424) is expressed in actively growing tissues, especially in pre-pollination ears at the flowering stage (Pang et al., 2013). In sorghum, SbABCB16 (Sb06g018860) and SbABCB18 (Sb06g030350) present the closest protein sequence similarity to ABCB19 from Arabidopsis. SbABCB16 expression is highest in the roots and is not responsive to IAA and 1-NOA treatments, while SbABCB18 is mostly expressed in leaves and is up-regulated by IAA, 1-NOA, and BR applications (Shen et al., 2010).

FIGURE 2.

The br2 maize mutant shows dramatically impacted stalk architecture. The br2 adult plant shows altered stalk height due to reduction in internode length, which is caused by the disruption of IAA transport mediated by ZmABCB1. The same phenotype is present in the sorghum dw3 mutant, which carries a tandem duplication in the SbABCB1/Dw3 gene.

AUX/LAXs

The existence of auxin importers in plants was first demonstrated studying the Arabidopsis auxin insensitive 1 (aux1) mutant, which carries defects in roots gravitropic response. AtAUX1 belongs to a small gene family composed of four highly conserved proteins that share similarities with amino acid transporters: AtAUX1, AtLAX1, -2, and -3 (Péret et al., 2012). AtAUX1 encodes a protein similar to fungal amino acid permeases and is expressed in columella, lateral root cap, epidermis, and stele tissues of the primary root where it acts as an auxin importer (Bennett et al., 1996; Swarup et al., 2001, 2004; Carrier et al., 2008). AtAUX1 is involved in auxin-regulated root gravitropic response together with the auxin exporter AtPIN2. The coordinated action of these two proteins forms a lateral auxin gradient which inhibits the expansion of epidermal cells on the lower side of the root relative to the upper side, eventually causing the downward root curvature (Swarup et al., 2005). aux1, as well as pin2 Arabidopsis mutants are agravitropic and aux1 also presents a decreased number of lateral roots due to defects in lateral root initiation (Marchant et al., 2002). AtAUX1 and AtLAX1, act redundantly in regulating the phyllotactic pattern in Arabidopsis although AtLAX2 is not expressed in the SAM L1 layer. Since AtLAX2 is expressed in the forming primordium vasculature, one hypothesis is that AtLAX2 enhances the strength of the primordium as an auxin sink by pulling IAA from the L1 layer of the SAM (Bainbridge et al., 2008; Kierzkowski et al., 2013). AtLAX2 is involved in vascular development in cotyledons and it is also expressed in young vascular tissues, the quiescent center and columella cells in the primary root (Péret et al., 2012). AtLAX3 is expressed in the columella and stele of the primary root and it is involved in lateral root development, as Arabidopsis lax3 mutants show delayed lateral root emergence (Swarup et al., 2008). No root growth–related defects or lateral root–related defects are observed in either lax1 or lax2 single mutants while aux1lax3 double mutant shows a severe reduction in the number of emerged lateral roots (Swarup et al., 2008). Auxin binding and import activity of AUX/LAX proteins has been demonstrated using an oocyte expression system for AtAUX1 (Yang et al., 2006), AtLAX3, and AtLAX1 or a yeast-based heterologous expression system in the case of AtLAX2 (Yang et al., 2006; Carrier et al., 2008; Péret et al., 2012).

AUX/LAXs IN MONOCOTS

Recently, the expression profile of a putative AUX1 homolog in rice (OsAUX1, Genebank ID AK068536) has been published (Song et al., 2013). The study investigates lateral roots developmental pattern, auxin distribution, PAT and expression of auxin transporter genes in the rice cultivars “Nanguang” and “Elio,” under different nitrogen availability. Expression of OsAUX1 results higher in the lateral root initiation and emergence zone of “Nanguang” roots in response to partial NO3- nutrition rather than to NH4+ alone. OsAUX1 is up-regulated in the lateral root elongation zone in the roots of both cultivars in response to phosphorus–nitrogen–nitrogen (PNN) compared to NH4+ alone (Song et al., 2013).

ZmAUX1, the closest maize homolog of AtAUX1, has 7–10 predicted TMDs and it’s 73% identical to AtAUX1 (Hochholdinger et al., 2000). Northern blot experiments show expression in the tips of primary, lateral, seminal, and crown roots. In situ hybridization shows that ZmAUX1 expression is tissue-specific and confined to the endodermal and pericycle cell layers of the primary root, as well as to the epidermal cell layer (Hochholdinger et al., 2000). ZmAUX1 and AtAUX1 exhibit a preference for IAA and 2,4-D over NAA as substrate and are subject to differential transport inhibition by hexyloxy and benzyloxy derivatives of IAA (Parry et al., 2001; Tsuda et al., 2011). Transcriptome analysis indicates a role for ZmAUX1 in leaf primordia differentiation, although evidence is still not conclusive (Brooks et al., 2009).

Five LAX genes, named SbLAX1-5, have been identified in sorghum. The corresponding proteins present a highly conserved core region with 10 predicted transmembrane helices and their transcript levels are higher in leaves and stems rather than in roots and inflorescence tissues (Shen et al., 2010). Expression analysis of 3-weeks-old sorghum seedlings indicates that IAA treatment induces SbLAX2 and SbLAX3, but it inhibits SbLAX1 and SbLAX4 expression in leaves and roots, as well as it down-regulates SbLAX5 expression in leaves. BR treatment induces the expression of all five SbLAX genes in roots while it down-regulates SbLAX1 and -4 in leaves. ABA, salt, and drought treatments alter the expression profile of all SbLAXs (Shen et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2011).

PILS

PIN-LIKES represent the most recently characterized family of plant auxin transport proteins and include seven members in Arabidopsis. PILS show low (10–18%) sequence identity with PINs and they are all capable of transporting auxin across the PM in heterologous systems (Barbez et al., 2012). PILS regulate intracellular auxin accumulation at the ER and thus reduce the availability for free auxin that can reach the nucleus, possibly exerting a role in auxin signaling that is comparable to that of AtPIN5 (Barbez et al., 2012; Barbez and Kleine-Vehn, 2013). The PILS family is conserved throughout the plant lineage, having representatives in several taxa including unicellular algae, where PINs have not been found yet. This indicates that PILS could be evolutionarily older than PINs (Feraru et al., 2012; Viaene et al., 2013). Six PILS have been identified in rice, 10 in maize, 7 in sorghum, and 8 in Brachypodium (Figure 3; Feraru et al., 2012). Forestan et al. (2012) identified two maize proteins that in sequence comparison analysis do not cluster with Arabidopsis PINs: ZmPINX and ZmPINY. Our sequence comparison verified that the two proteins are more similar to PILS rather than PINs, as previously hypothesized (Figure 3). Expression analysis for these genes shows that they are ubiquitously expressed and differentially up-regulated in maize organs. In detail, ZmPINX is up-regulated in root apex and male and female inflorescences, while ZmPINY is highly expressed during kernel development (Forestan et al., 2012).

FIGURE 3.

Neighbor-joining sequence similarity analysis of the PIN and PILS proteins from Arabidopsis, rice, maize, sorghum, and Brachypodium. The unrooted tree shows the degree of sequence similarity among PIN and PILS proteins from Arabidopsis, rice, maize, sorghum, and Brachypodium. ZmPINX and ZmPINY present higher overall similarity to PILS rather than PIN proteins. Bootstrap values higher than 60 are indicated at each node.

CONCLUSION

Auxin has a fundamental role in plant organs formation and its polar transport across cellular membranes is crucial for the correct development and response to external stimuli. Master regulators of PAT are auxin transport proteins, which have been extensively studied in Arabidopsis but not in other species, mainly due to the difficulty to obtain loss-of-function mutants. In monocots, only a few of these transporters have been characterized, mainly in rice and maize and most of the information available has been obtained by expression analyses without functional characterization. There are substantial divergences in development and plant structure between monocots and dicots. Differences are present in seed, vascular system, and leaf developmental programs (Tsiantis, 1999; Scarpella and Meijer, 2004; Coudert et al., 2010; Sreenivasulu and Wobus, 2013). The monocot root system architecture and cellular organization also differ considerably from those of dicots (Hochholdinger et al., 2004; Smith and De Smet, 2012). In addition, monocots have a segmented stem as opposed to the unsegmented stem of dicots. Auxin transporter families are larger in monocots allowing for the possibility of functional redundancy, but also for neo- and sub-functionalization of specific proteins. Monocot-specific and organ-specific proteins exist and they have a distinct role in regulating auxin driven organ development (PIN9). In some cases, alterations in PAT result in interesting new traits, such as dwarfism in maize and sorghum br2 and dw3 mutants respectively, which can be exploited to generate more productive lines through breeding programs. Moreover, many more short-statured mutants exist in maize that may have defects in auxin transport, although none of these mutants have been characterized in any detail. Interestingly, quite a few of these mutants exhibit dominant inheritance (Johal, unpublished) that makes them interesting in at least two ways. First, they can help side step gene redundancy problems and allow the functional exploration of additional genes. Second, they can be used in MAGIC (mutant-assisted gene identification and characterization)-based enhancer suppressor screens to unveil natural variation in a trait of interest (Johal et al., 2008). Even transgenic reporters for auxin activity can be used in lieu of bona fide dominant mutants for such MAGIC screens. The traditional enhancer/suppressor screens based on mutagenesis can also be employed to identify additional genes that encode auxin transporters. One such resource already exists in sorghum, where a line carrying a dw3 mutation in SbABCB1 was EMS mutagenized to produce and sequence M2 populations for both forward and reverse genetics (Krothapalli et al., 2013). These M2 populations can be screened to identify other genes in the network with the ability to suppress or enhance the dw3 phenotype. Finally, there is the exciting possibility of using new genome editing and reverse genetics tools such as CRISPR/Cas9, which has been shown to work in rice and maize (Miao et al., 2013; Liang et al., 2014). Technologies like this can be used to alter the expression and function of genes encoding auxin transporters in monocots and this may lead to important new breakthroughs in our understanding of their roles in development and response to the environment.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Antje Klempien and Cristian Forestan for helpful comments on the manuscript.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://www.frontiersin.org/journal/10.3389/fpls.2014.00393/abstract

REFERENCES

- Abas L., Benjamins R., Malenica N., Paciorek T., Wiśniewska J., Wirniewska J., et al. (2006). Intracellular trafficking and proteolysis of the Arabidopsis auxin-efflux facilitator PIN2 are involved in root gravitropism. Nat. Cell Biol. 8 249–256 10.1038/ncb1369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailly A., Yang H., Martinoia E., Geisler M., Murphy A. S. (2011). Plant lessons: exploring ABCB functionality through structural modeling. Front. Plant Sci. 2:108 10.3389/fpls.2011.00108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bainbridge K., Guyomarc’h S., Bayer E., Swarup R., Bennett M., Mandel T., et al. (2008). Auxin influx carriers stabilize phyllotactic patterning. Genes Dev. 22 810–823 10.1101/gad.462608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandyopadhyay A., Blakeslee J. J., Lee O. R., Mravec J., Sauer M., Titapiwatanakun B., et al. (2007). Interactions of PIN and PGP auxin transport mechanisms. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 35 137–141 10.1042/BST0350137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbez E., Kleine-Vehn J. (2013). Divide Et Impera – cellular auxin compartmentalization. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 16 78–84 10.1016/j.pbi.2012.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbez E., Kubeš M., Rolèík J., Béziat C., Pěnčík A., Wang B., et al. (2012). A novel putative auxin carrier family regulates intracellular auxin homeostasis in plants. Nature 485 119–122 10.1038/nature11001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa I. C. R., Zourelidou M., Willige B. C., Weller B., Schwechheimer C. (2014). D6 PROTEIN KINASE activates auxin transport-dependent growth and PIN-FORMED phosphorylation at the plasma membrane. Dev. Cell 29 674–685 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell C. J., Maher E. P. (1990). Mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana with abnormal gravitropic responses. Mol. Gen. Genet. 220 289–293 10.1007/BF00260496 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bender R. L., Fekete M. L., Klinkenberg P. M., Hampton M., Bauer B., Malecha M., et al. (2013). PIN6 is required for nectary auxin response and short stamen development. Plant J. 74 893–904 10.1111/tpj.12184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benková E., Michniewicz M., Sauer M., Teichmann T., Seifertová D., Jürgens G., et al. (2003). Local, efflux-dependent auxin gradients as a common module for plant organ formation. Cell 115 591–602 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00924-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett M. J., Marchant A., Green H. G., May S. T., Ward S. P., Millner P. A., et al. (1996). Arabidopsis AUX1 gene: a permease-like regulator of root gravitropism. Science 273 948–950 10.1126/science.273.5277.948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett T., Brockington S. F., Rothfels C., Graham S., Stevenson D., Kutchan T., et al. (2014). Paralagous radiations of PIN proteins with multiple origins of non-canonical PIN structure. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1–42 10.1093/molbev/msu147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertoni G. (2011). Indolebutyric acid-derived auxin and plant development. Plant Cell 23 845–845 10.1105/tpc.111.230312 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bolduc N., O’Connor D., Moon J., Lewis M., Hake S. (2012). How to pattern a leaf. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 77 47–51 10.1101/sqb.2012.77.014613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks L., Strable J., Zhang X., Ohtsu K., Zhou R., Sarkar A., et al. (2009). Microdissection of shoot meristem functional domains. PLoS Genet. 5:e1000476 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carraro N., Forestan C., Canova S., Traas J., Varotto S. (2006). ZmPIN1a and ZmPIN1b encode two novel putative candidates for polar auxin transport and plant architecture determination of maize. Plant Physiol. 142 254–264 10.1104/pp.106.080119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carraro N., Tisdale-Orr T. E., Clouse R. M., Knöller A. S., Spicer R. (2012). Diversification and expression of the PIN, AUX/LAX, and ABCB families of putative auxin transporters in Populus. Front. Plant Sci. 3:17 10.3389/fpls.2012.00017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrier D. J., Bakar N. T. A., Swarup R., Callaghan R., Napier R. M., Bennett M. J., et al. (2008). The binding of auxin to the Arabidopsis auxin influx transporter AUX1. Plant Physiol. 148 529–535 10.1104/pp.108.122044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazzonelli C. I., Vanstraelen M., Simon S., Yin K., Carron-Arthur A., Nisar N., et al. (2013). Role of the Arabidopsis PIN6 auxin transporter in auxin homeostasis and auxin-mediated development. PLoS ONE 8:e70069 10.1371/journal.pone.0070069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Lausser A., Dresselhaus T. (2014). Hormonal responses during early embryogenesis in maize. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 42 325–331 10.1042/BST20130260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R., Hilson P., Sedbrook J., Rosen E., Caspar T., Masson P. H. (1998). The Arabidopsis thaliana AGRAVITROPIC 1 gene encodes a component of the polar-auxin-transport efflux carrier. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95 15112–15117 10.1073/pnas.95.25.15112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Fan X., Song W., Zhang Y., Xu G. (2012). Over-expression of OsPIN2 leads to increased tiller numbers, angle and shorter plant height through suppression of OsLAZY1. Plant Biotechnol. J. 10 139–149 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2011.00637.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho M., Cho H.-T. (2013). The function of ABCB transporters in auxin transport. Plant Signal. Behav. 8:e22990 10.4161/psb.22990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho M., Lee Z.-W., Cho H.-T. (2012). ATP-binding cassette B4, an auxin-efflux transporter, stably associates with the plasma membrane and shows distinctive intracellular trafficking from that of PIN-FORMED proteins. Plant Physiol. 159 642–654 10.1104/pp.112.196139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie J. M., Murphy A. S. (2013). Shoot phototropism in higher plants: new light through old concepts. Am. J. Bot. 100 35–46 10.3732/ajb.1200340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie J. M., Yang H., Richter G. L., Sullivan S., Thomson C. E., Lin J., et al. (2011). phot1 inhibition of ABCB19 primes lateral auxin fluxes in the shoot apex required for phototropism. PLoS Biol. 9:e1001076 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clouse R. M., Carraro N. (2014). A novel phylogeny and morphological reconstruction of the PIN genes and first phylogeny of the ACC-oxidases (ACOs). Front. Plant Sci. 5:296 10.3389/fpls.2014.00296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coudert Y., Périn C., Courtois B., Khong N. G., Gantet P. (2010). Genetic control of root development in rice, the model cereal. Trends Plant Sci. 15 219–226 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies P. J. (ed.). (2004). Plant Hormones Biosynthesis, Signal Transduction, Action! 3rd Edn. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers [Google Scholar]

- Delbarre A., Muller P., Imhoff V., Guern J. (1996). Comparison of mechanisms controlling uptake and accumulation of 2,4-dichlorophenoxy acetic acid, naphthalene-l-acetic acid, and indole-3-acetic acid in suspension-cultured tobacco cells. Planta 198 532–541 10.1007/BF00262639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhonukshe P., Huang F., Galvan-Ampudia C. S., Mähönen A. P., Kleine-Vehn J., Xu J., et al. (2010). Plasma membrane-bound AGC3 kinases phosphorylate PIN auxin carriers at TPRXS(N/S) motifs to direct apical PIN recycling. Development 137 3245–3255 10.1242/dev.052456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Z., Wang B., Moreno I., Dupláková N., Simon S., Carraro N., et al. (2012). ER-localized auxin transporter PIN8 regulates auxin homeostasis and male gametophyte development in Arabidopsis. Nat. Commun. 3 941 10.1038/ncomms1941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudlers R., Hertig C. (1992). Structure of an mdr-like Gene from Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Biol. Chem. 267 5882–5888 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan A. N., Schlueter J., Spooner D. M. (2012). Applications of next-generation sequencing in plant biology. Am. J. Bot. 99 175–185 10.3732/ajb.1200020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estelle M. (1998). Polar auxin transport. New support for an old model. Plant Cell 10 1775–1778 10.1105/tpc.10.11.1775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X.-L., Ni W.-M., Elge S., Mueller-Roeber B., Xu Z.-H., Xue H.-W. (2006). Auxin flow in anther filaments is critical for pollen grain development through regulating pollen mitosis. Plant Mol. Biol. 61 215–226 10.1007/s11103-006-0005-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feraru E., Vosolsobě S., Feraru M. I., Petrášek J., Kleine-Vehn J. (2012). Evolution and structural diversification of PILS putative auxin carriers in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 3:227 10.3389/fpls.2012.00227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forestan C., Farinati S., Varotto S. (2012). The maize PIN gene family of auxin transporters. Front. Plant Sci. 3:16 10.3389/fpls.2012.00016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forestan C., Meda S., Varotto S. (2010). ZmPIN1-mediated auxin transport is related to cellular differentiation during maize embryogenesis and endosperm development. Plant Physiol. 152 1373–1390 10.1104/pp.109.150193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fozard J. A, King J. R., Bennett M. J. (2013). Modelling auxin efflux carrier phosphorylation and localization. J. Theor. Biol. 319 34–49 10.1016/j.jtbi.2012.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friml J., Benková E., Blilou I., Wisniewska J., Hamann T., Ljung K., et al. (2002a). AtPIN4 mediates sink-driven auxin gradients and root patterning in Arabidopsiss. Cell 108 661–673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friml J., Wiśniewska J., Benková E., Mendgen K., Palme K. (2002b). Lateral relocation of auxin efflux regulator PIN3 mediates tropism in Arabidopsis. Nature 415 806–809 10.1038/415806a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friml J., Vieten A., Sauer M., Weijers D., Schwarz H., Hamann T., et al. (2003). Efflux-dependent auxin gradients establish the apical-basal axis of Arabidopsis. Nature 426 147–153 10.1038/nature02085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friml J., Yang X., Michniewicz M., Weijers D., Quint A., Tietz O., et al. (2004). A PINOID-dependent binary switch in apical-basal PIN polar targeting directs auxin efflux. Science 306 862–865 10.1126/science.1100618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallavotti A. (2013). The role of auxin in shaping shoot architecture. J. Exp. Bot. 64 2593–2608 10.1093/jxb/ert141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallavotti A., Yang Y., Schmidt R. J., Jackson D. (2008). The relationship between auxin transport and maize branching. Plant Physiol. 147 1913–1923 10.1104/pp.108.121541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gälweiler L., Guan C., Müller A., Wisman E., Mendgen K., Yephremov A., et al. (1998). Regulation of polar auxin transport by AtPIN1 in Arabidopsis vascular tissue. Science 282 2226–2230 10.1126/science.282.5397.2226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly A., Lee S.-H., Cho H.-T. (2012). Functional identification of the phosphorylation sites of Arabidopsis PIN-FORMED3 for its subcellular localization and biological role. Plant J. 71 810–823 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.05030.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly A., Lee S. H., Cho M., Lee O. R., Yoo H., Cho H.-T. (2010). Differential auxin-transporting activities of PIN-FORMED proteins in Arabidopsis root hair cells. Plant Physiol. 153 1046–1061 10.1104/pp.110.156505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly A., Park M., Kesawat M. S., Cho H.-T. (2014). Functional analysis of the hydrophilic loop in intracellular trafficking of Arabidopsis PIN-FORMED proteins. Plant Cell 1–17 10.1105/tpc.113.118422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia O., Bouige P., Forestier C., Dassa E. (2004). Inventory and comparative analysis of rice and Arabidopsis ATP-binding cassette (ABC) systems. J. Mol. Biol. 343 249–265 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.07.093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler M., Blakeslee J. J., Bouchard R., Lee O. R., Vincenzetti V., Bandyopadhyay A., et al. (2005). Cellular efflux of auxin catalyzed by the Arabidopsis MDR/PGP transporter AtPGP1. Plant J. 44 179–194 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02519.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler M., Murphy A. S. (2006). The ABC of auxin transport: the role of p-glycoproteins in plant development. FEBS Lett. 580 1094–1102 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.11.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler M., Wang B., Zhu J. (2014). Auxin transport during root gravitropism: transporters and techniques. Plant Biol. (Stuttg.) 16(Suppl. 1) 50–57 10.1111/plb.12030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habets M. E. J., Offringa R. (2014). Tansley review PIN-driven polar auxin transport in plant developmental plasticity: a key target for environmental and endogenous signals. New Phytol. 203 362–377 10.1111/nph.12831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins C. F., Linton K. J. (2004). The ATP switch model for ABC transporters. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11 918–926 10.1038/nsmb836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochholdinger F., Park W. J., Sauer M., Woll K. (2004). From weeds to crops: genetic analysis of root development in cereals. Trends Plant Sci. 9 42–48 10.1016/j.tplants.2003.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochholdinger F., Wulff D., Reuter K., Park W. J., Feix G. (2000). Tissue-specific expression of AUX1 in maize roots. J. Plant Physiol. 157 315–319 10.1016/S0176-1617(00)80053-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jasinski M., Ducos E., Martinoia E., Boutry M. (2003). The ATP-binding cassette transporters?: structure, function, and gene family comparison between. Plant Physiol. 131 1169–1177 10.1104/pp.102.014720.ABC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johal G. S., Balint-Kurti P., Weil C. F. (2008). Mining and harnessing natural variation: a little MAGIC. Crop Sci. 48:2066 10.2135/cropsci2008.03.0150 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kamimoto Y., Terasaka K., Hamamoto M., Takanashi K., Fukuda S., Shitan N., et al. (2012). Arabidopsis ABCB21 is a facultative auxin importer/exporter regulated by cytoplasmic auxin concentration. Plant Cell Physiol. 53 2090–2100 10.1093/pcp/pcs149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneda M., Schuetz M., Lin B. S. P., Chanis C., Hamberger B., Western T. L., et al. (2011). ABC transporters coordinately expressed during lignification of Arabidopsis stems include a set of ABCBs associated with auxin transport. J. Exp. Bot. 62 2063–2077 10.1093/jxb/erq416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J., Park J., Choi H., Burla B., Kretzschmar T., Lee Y., et al. (2011). Plant ABC transporters. Arabidopsis Book 9:e0153 10.1199/tab.0153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kende H., Zeevaart J. A. D. (1997). The five “Classical” plant hormones. Plant Cell 9 1197–1210 10.1105/tpc.9.7.1197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kierzkowski D., Lenhard M., Smith R., Kuhlemeier C. (2013). Interaction between meristem tissue layers controls phyllotaxis. Dev. Cell 26 616–628 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleine-vehn J., Ding Z., Jones A. R., Tasaka M., Morita M. T. (2010). Gravity-induced PIN transcytosis for polarization of auxin fl uxes in gravity-sensing root cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 22344–22349 10.1073/pnas.101314510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleine-Vehn J., Wabnik K., Martinière A., Łangowski Ł., Willig K., Naramoto S., et al. (2011). Recycling, clustering, and endocytosis jointly maintain PIN auxin carrier polarity at the plasma membrane. Mol. Syst. Biol. 7:540 10.1038/msb.2011.72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knöller A. S., Blakeslee J. J., Richards E. L., Peer W. A., Murphy A. S. (2010). Brachytic2/ZmABCB1 functions in IAA export from intercalary meristems. J. Exp. Bot. 61 3689–3696 10.1093/jxb/erq180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer E. M., Bennett M. J. (2006). Auxin transport: a field in flux. Trends Plant Sci. 11 382–386 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Křeček P., Skůpa P., Libus J., Naramoto S., Tejos R., Friml J., et al. (2009). Protein family review The PIN-FORMED ( PIN ) protein family of auxin transporters. Genome Biol. 10 1–11 10.1186/gb-2009-10-12-249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krothapalli K., Buescher E. M., Li X., Brown E., Chapple C., Dilkes B. P., et al. (2013). Forward genetics by genome sequencing reveals that rapid cyanide release deters insect herbivory of Sorghum bicolor. Genetics 195 309–318 10.1534/genetics.113.149567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubeš M., Yang H., Richter G. L., Cheng Y., Młodzińska E., Wang X., et al. (2011). The Arabidopsis concentration-dependent influx/efflux transporter ABCB4 regulates cellular auxin levels in the root epidermis. Plant J. 69 640–654 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04818.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampugnani E. R., Kilinc A., Smyth D. R. (2013). Auxin controls petal initiation in Arabidopsis. Development 140 185–194 10.1242/dev.084582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin M. A, Blackshields G., Brown N. P., Chenna R., McGettigan P. A, McWilliam H., et al. (2007). Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23 2947–2948 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M., Choi Y., Burla B., Kim Y.-Y., Jeon B., Maeshima M., et al. (2008). The ABC transporter AtABCB14 is a malate importer and modulates stomatal response to CO2. Nat. Cell Biol. 10 1217–1223 10.1038/ncb1782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis D. R., Wu G., Ljung K., Spalding E. P. (2009). Auxin transport into cotyledons and cotyledon growth depend similarly on the ABCB19 Multidrug Resistance-like transporter. Plant J. 60 91–101 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03941.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyser O. (2010). The power of auxin in plants. Plant Physiol. 154 501–505 10.1104/pp.110.161323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Z., Zhang K., Chen K., Gao C. (2014). Targeted mutagenesis in Zea mays using TALENs and the CRISPR/Cas System. J. Genet. Genomics 41 63–68 10.1016/j.jgg.2013.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin R., Wang H. (2005). Two homologous ATP-binding cassette transporter proteins, AtMDR1 and AtPGP1, regulate Arabidopsis photomorphogenesis and root development by mediating polar auxin transport. Plant Physiol. 138 949–964 10.1104/pp.105.061572.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löfke C., Luschnig C., Kleine-Vehn J. (2013). Posttranslational modification and trafficking of PIN auxin efflux carriers. Mech. Dev. 130 82–94 10.1016/j.mod.2012.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luschnig C., Gaxiola R. A., Grisafi P., Fink G. R. (1998). EIR1, a root-specific protein involved in auxin transport, is required for gravitropism in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genes Dev. 12 2175–2187 10.1101/gad.12.14.2175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchant A., Bhalerao R., Casimiro I., Eklöf J., Casero P. J., Bennett M., et al. (2002). AUX1 promotes lateral root formation by facilitating indole-3-acetic acid distribution between sink and source tissues in the Arabidopsis seedling. Plant Cell 14 589–597 10.1105/tpc.010354.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLamore E. S., Diggs A., Calvo Marzal P., Shi J., Blakeslee J. J., Peer W. A., et al. (2010). Non-invasive quantification of endogenous root auxin transport using an integrated flux microsensor technique. Plant J. 63 1004–1016 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04300.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McSteen P. (2010). Auxin and monocot development. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2:a001479 10.1101/cshperspect.a001479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao J., Guo D., Zhang J., Huang Q., Qin G., Zhang X., et al. (2013). Targeted mutagenesis in rice using CRISPR-cas system. Cell Res. 23 1233–1236 10.1038/cr.2013.123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyashita Y., Takasugi T., Ito Y. (2010). Identification and expression analysis of PIN genes in rice. Plant Sci. 178 424–428 10.1016/j.plantsci.2010.02.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohanty A., Luo A., DeBlasio S., Ling X., Yang Y., Tuthill D. E., et al. (2009). Advancing cell biology and functional genomics in maize using fluorescent protein-tagged lines. Plant Physiol. 149 601–605 10.1104/pp.108.130146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Möller B., Weijers D. (2009). Auxin control of embryo patterning. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 1:a001545 10.1101/cshperspect.a001545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mravec J., Skůpa P., Bailly A., Hoyerová K., Krecek P., Bielach A., et al. (2009). Subcellular homeostasis of phytohormone auxin is mediated by the ER-localized PIN5 transporter. Nature 459 1136–1140 10.1038/nature08066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller A., Guan C., Gälweiler L., Tänzler P., Huijser P., Marchant A., et al. (1998). AtPIN2 defines a locus of Arabidopsis for root gravitropism control. EMBO J. 17 6903–6911 10.1093/emboj/17.23.6903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller D., Leyser O. (2011). Auxin, cytokinin and the control of shoot branching. Ann. Bot. 107 1203–1212 10.1093/aob/mcr069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Multani D. S., Briggs S. P., Chamberlin M. A, Blakeslee J. J., Murphy A. S., Johal G. S. (2003). Loss of an MDR transporter in compact stalks of maize br2 and sorghum dw3 mutants. Science 302 81–84 10.1126/science.1086072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagashima A., Uehara Y., Sakai T. (2008). The ABC subfamily B auxin transporter AtABCB19 is involved in the inhibitory effects of N-1-naphthyphthalamic acid on the phototropic and gravitropic responses of Arabidopsis hypocotyls. Plant Cell Physiol. 49 1250–1255 10.1093/pcp/pcn092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noh B., Murphy A. S., Spalding E. P. (2001). Multidrug resistance-like genes of Arabidopsis required for auxin transport and auxin-mediated development. Plant cell 13 2441–2454 10.1105/tpc.010350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor D. L., Runions A., Sluis A., Bragg J., Vogel J. P., Prusinkiewicz P., et al. (2014). A division in PIN-mediated auxin patterning during organ initiation in grasses. PLoS Comput. Biol. 10:e1003447 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada K., Ueda J., Komaki M. K., Bell C. J., Shimura Y. (1991). Requirement of the auxin polar transport system in early stages of Arabidopsis floral bud formation. Plant Cell 3 677 10.2307/3869249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang K., Li Y., Liu M., Meng Z., Yu Y. (2013). Inventory and general analysis of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) gene superfamily in maize (Zea mays L.). Gene 526 411–428 10.1016/j.gene.2013.05.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry G., Delbarre A., Marchant A., Swarup R., Napier R., Perrot-Rechenmann C., et al. (2001). Novel auxin transport inhibitors phenocopy the auxin influx carrier mutation aux1. Plant J. 25 399–406 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.00970.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Péret B., Swarup K., Ferguson A., Seth M., Yang Y., Dhondt S., et al. (2012). AUX/LAX genes encode a family of auxin influx transporters that perform distinct functions during Arabidopsis development. Plant Cell 24 2874–2885 10.1105/tpc.112.097766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhardt D., Pesce E.-R., Stieger P., Mandel T., Baltensperger K., Bennett M., et al. (2003). Regulation of phyllotaxis by polar auxin transport. Nature 426 255–260 10.1038/nature02081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert S., Kleine-Vehn J., Barbez E., Sauer M., Paciorek T., Baster P., et al. (2010). ABP1 mediates auxin inhibition of clathrin-dependent endocytosis in Arabidopsis. Cell 143 111–121 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas-Pierce M., Titapiwatanakun B., Sohn E. J., Fang F., Larive C. K., Blakeslee J., et al. (2007). Arabidopsis P-glycoprotein19 participates in the inhibition of gravitropism by gravacin. Chem. Biol. 14 1366–1376 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosquete M. R., von Wangenheim D., Marhavý P., Barbez E., Stelzer E. H. K., Benková E., et al. (2013). An auxin transport mechanism restricts positive orthogravitropism in lateral roots. Curr. Biol. 23 817–822 10.1016/j.cub.2013.03.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santelia D., Vincenzetti V., Azzarello E., Bovet L., Fukao Y., Düchtig P., et al. (2005). MDR-like ABC transporter AtPGP4 is involved in auxin-mediated lateral root and root hair development. FEBS Lett. 579 5399–5406 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.08.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawchuk M. G., Edgar A., Scarpella E. (2013). Patterning of leaf vein networks by convergent auxin transport pathways. PLoS Genet. 9:e1003294 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarpella E., Marcos D., Berleth T. (2006). Control of leaf vascular patterning by polar auxin transport. Genes Dev. 20 1015–1027 10.1101/gad.1402406.gree [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarpella E., Meijer A. H. (2004). Pattern formation in the vascular system of monocot and dicot plant species. New Phytol. Tansley Rev. 164 209–242 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01191.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen C., Bai Y., Wang S., Zhang S., Wu Y., Chen M., et al. (2010). Expression profile of PIN, AUX/LAX and PGP auxin transporter gene families in Sorghum bicolor under phytohormone and abiotic stress. FEBS J. 277 2954–2969 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07706.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidler M., Hassa P., Hasan S., Ringli C., Dudler R. (1998). Involvement of an ABC transporter in a developmental pathway regulating hypocotyl cell elongation in the light. Plant Cell 10 1623–1636 10.1105/tpc.10.10.1623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon S., Petrášek J. (2011). Why plants need more than one type of auxin. Plant Sci. 180 454–460 10.1016/j.plantsci.2010.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S., De Smet I. (2012). Root system architecture: insights from Arabidopsis and cereal crops. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 367 1441–1452 10.1098/rstb.2011.0234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song W., Sun H., Li J., Gong X., Huang S., Zhu X., et al. (2013). Auxin distribution is differentially affected by nitrate in roots of two rice cultivars differing in responsiveness to nitrogen. Ann. Bot. 112 1383–1393 10.1093/aob/mct212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sreenivasulu N., Wobus U. (2013). Seed-development programs: a systems biology-based comparison between dicots and monocots. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 64 189–217 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050312-120215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun F., Zhang W., Hu H., Li B., Wang Y., Zhao Y., et al. (2008). Salt modulates gravity signaling pathway to regulate growth direction of primary roots in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 146 178–188 10.1104/pp.107.109413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swarup K., Benková E., Swarup R., Casimiro I., Péret B., Yang Y., et al. (2008). The auxin influx carrier LAX3 promotes lateral root emergence. Nat. Cell Biol. 10 946–954 10.1038/ncb1754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swarup R., Kargul J., Marchant A., Zadnik D., Rahman A., Mills R., et al. (2004). Structure-function analysis of the presumptive Arabidopsis auxin permease AUX1. Plant Cell 16 3069–3083 10.1105/tpc.104.024737.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swarup R., Kramer E. M., Perry P., Knox K., Leyser H. M. O., Haseloff J., et al. (2005). Root gravitropism requires lateral root cap and epidermal cells for transport and response to a mobile auxin signal. Nat. Cell Biol. 7 1057–1065 10.1038/ncb1316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swarup R., Marchant A., Ljung K., Sandberg G., Palme K., Bennett M., et al. (2001). Localization of the auxin permease AUX1 suggests two functionally distinct hormone transport pathways operate in the Arabidopsis root apex. Genes Dev. 15 2648–2653 10.1101/gad.210501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Stecher G., Peterson D., Filipski A., Kumar S. (2013). MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30 2725–2729 10.1093/molbev/mst197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H., Dhonukshe P., Brewer P. B., Friml J. (2006). Spatiotemporal asymmetric auxin distribution: a means to coordinate plant development. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 63 2738–2754 10.1007/s00018-006-6116-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarkowská D., Novák O., Floková K., Tarkowski P., Tureèková V., Grúz J., et al. (2014). Quo vadis plant hormone analysis? Planta 240 55–76 10.1007/s00425-014-2063-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terasaka K., Blakeslee J. J., Titapiwatanakun B., Peer W. A., Bandyopadhyay A., Makam S. N., et al. (2005). PGP4, an ATP binding cassette P-glycoprotein, catalyzes auxin transport in Arabidopsis thaliana roots. Plant Cell 17 2922–2939 10.1105/tpc.105.035816.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titapiwatanakun B., Murphy A. S. (2009). Post-transcriptional regulation of auxin transport proteins: cellular trafficking, protein phosphorylation, protein maturation, ubiquitination, and membrane composition. J. Exp. Bot. 60 1093–10107 10.1093/jxb/ern240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsiantis M. (1999). The maize rough sheath2 gene and leaf development programs in monocot and dicot plants. Science 284 154–156 10.1126/science.284.5411.154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda E., Yang H., Nishimura T., Uehara Y., Sakai T., Furutani M., et al. (2011). Alkoxy-auxins are selective inhibitors of auxin transport mediated by PIN, ABCB, and AUX1 transporters. J. Biol. Chem. 286 2354–2364 10.1074/jbc.M110.171165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utsuno K., Shikanai T., Yamada Y., Hashimoto T. (1998). Agr, an agravitropic locus of Arabidopsis thaliana, encodes a novel membrane-protein family member. Plant Cell Physiol. 39 1111–1118 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a029310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viaene T., Delwiche C. F., Rensing S. A., Friml J. (2013). Origin and evolution of PIN auxin transporters in the green lineage. Trends Plant Sci. 18 5–10 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieten A., Vanneste S., Wisniewska J., Benková E., Benjamins R., Beeckman T., et al. (2005). Functional redundancy of PIN proteins is accompanied by auxin-dependent cross-regulation of PIN expression. Development 132 4521–4531 10.1242/dev.02027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.-R., Hu H., Wang G.-H., Li J., Chen J.-Y., Wu P. (2009). Expression of PIN genes in rice (Oryza sativa L.): tissue specificity and regulation by hormones. Mol. Plant 2 823–831 10.1093/mp/ssp023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P., Cheng T., Wu S., Zhao F., Wang G., Yang L., et al. (2014a). Phylogeny and molecular evolution analysis of PIN-FORMED 1 in angiosperm. PLoS ONE 9:e89289 10.1371/journal.pone.0089289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Xu Y., Li Z., Zhang S., Lim J. -M., Lee K. O., et al. (2014b). OsMOGS is required for N-glycan formation and auxin-mediated root development in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant J. 78 632–645 10.1111/tpj.12497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Shen C., Zhang S., Xu Y., Jiang D., Qi Y. (2011). Analysis of subcellular localization of auxin carriers PIN, AUX/LAX and PGP in Sorghum bicolor. Plant Signal. Behav. 6 2023–2025 10.4161/psb.6.12.17968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weijers D., Sauer M., Meurette O., Friml J., Ljung K., Sandberg G., et al. (2005). Maintenance of embryonic auxin distribution for apical-basal patterning by PIN-FORMED-dependent auxin transport in Arabidopsis. 17 2517–2526 10.1105/tpc.105.034637.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Went F. (1926). On growth-accelerating substances in the coleoptile of Avena sativa. Proc. K. Ned. Akad. van Wet. 30 10–19 [Google Scholar]

- Willige B. C., Ahlers S., Zourelidou M., Barbosa I. C. R., Demarsy E., Trevisan M., et al. (2013). D6PK AGCVIII kinases are required for auxin transport and phototropic hypocotyl bending in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25 1674–1688 10.1105/tpc.113.111484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward A. W., Bartel B. (2005). Auxin: regulation, action, and interaction. Ann. Bot. 95 707–735 10.1093/aob/mci083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G., Otegui M. S., Spalding E. P. (2010). The ER-localized TWD1 immunophilin is necessary for localization of multidrug resistance-like proteins required for polar auxin transport in Arabidopsis roots. Plant Cell 22 3295–3304 10.1105/tpc.110.078360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M., Zhu L., Shou H., Wu P. (2005). A PIN1 family gene, OsPIN1, involved in auxin-dependent adventitious root emergence and tillering in rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 46 1674–1681 10.1093/pcp/pci183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Zhang S., Guo H., Wang S., Xu L., Li C., et al. (2014). OsABCB14 functions in auxin transport and iron homeostasis in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant J. 79 106–117 10.1111/tpj.12544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]