ABSTRACT

The maintenance of latent Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) genomes is mediated in cis by their terminal repeats (TR). A KSHV genome can have 16 to 50 copies of the 801-bp TR, each of which harbors a 71-bp-long minimal replicator element (MRE). A single MRE can support replication in transient assays, and the presence of as few as two TRs appears to support establishment of KSHV-derived plasmids. Why then does KSHV have such redundancy and heterogeneity in the number of TRs? By determining the abilities of KSHV-derived plasmids containing various numbers of the TRs and MREs to be established and maintained in the long term, we have found that plasmids with fewer than 16 TRs or those with tandem repeats of the MREs are maintained inefficiently, as shown by both their decreased abilities to support formation of colonies and their instability, resulting in frequent rearrangements yielding larger plasmids during and after establishment. These defects often can be overcome by adding the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) partitioning element, FR (i.e., family of repeats), in cis to these plasmids. In addition we have found that the spacing between MREs is important for their functions, too. Thus, two properties of KSHV's origin of latent replication essential for the efficient establishment and maintenance of viral plasmids stably are (i) the presence of approximately 16 copies of the TR, which are needed for efficient partitioning, and (ii) the presence of at least 2 MRE units separated by 801 bp of center-to-center spacing, which are required for efficient synthesis.

IMPORTANCE KSHV is a human tumor virus that maintains its genome as a plasmid in lymphoid tumor cells. Each plasmid DNA molecule encodes many origins of synthesis. Here we show that these many origins provide an essential advantage to KSHV, allowing the DNAs to be maintained without rearrangement. We find also that the correct spacing between KSHV's origins of DNA synthesis is required for them to support synthesis efficiently. The identification of these properties illuminates plasmid replication in mammalian cells and should lead to the development of rational means to inhibit these tumorigenic replicons.

INTRODUCTION

Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) is an oncogenic human herpesvirus causally associated with the endothelial cell-derived tumor, Kaposi's sarcoma (KS), and lymphoproliferative disorders, including primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) and multicentric Castleman's disease (MCD) (1–4). KSHV is present in KS and PELs primarily in the latent phase of its life cycle as a multicopy plasmid (2, 5–7). KSHV belongs to the gammaherpesvirus subfamily and is related to another oncogenic gammaherpesvirus, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). Various latently expressed genes of both EBV and KSHV have been shown to contribute directly to cell survival and proliferation. Forcing the loss of EBV genomes from EBV-positive Burkitt's lymphoma, posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD), and PEL-derived cell lines can induce apoptosis and affect cell growth, indicating that the lymphoma cells depend upon EBV for survival and/or proliferation (8–10). Attempts to isolate PEL cells after eviction of KSHV have not been successful (11), suggesting that the PELs are dependent on latent KSHV genomes for their survival and/or proliferation. Hence, given the importance of the persistence of latent KSHV genomes in the associated tumors, it is desirable to understand the factors that allow their maintenance stably in infected cells.

The maintenance of latent KSHV genomes in proliferating host cells involves synthesis or replication of the viral DNA during the S phase of the cell cycle and subsequent partitioning of the newly synthesized viral DNA into the daughter cells during mitosis. Synthesis is mediated in cis by its origin of latent replication located within its terminal repeat (TR) (12) and in trans by a viral protein, LANA1 (latency-associated nuclear antigen 1) (12–16). The TR is an 801-bp highly GC-rich unit and harbors a 71-bp-long minimal replicator element (MRE). The MRE, consisting of two LANA1-binding sites (LBS 1 and 2) and an upstream GC-rich replication element (RE), is the minimal element that supports synthesis of KSHV plasmids (17). LANA1 mediates licensed synthesis of the viral plasmid by binding to LBS 1 and 2 through its DNA-binding and dimerization domain located in the C terminus and recruiting the cellular origin recognition complex (ORC) (18–22). The partitioning of KSHV plasmids is thought to be mediated by tethering of viral plasmids to cellular chromosomes by LANA1. Binding and localization of LANA1 to the cellular chromatin occur through protein-protein interactions between LANA1's N terminus and core histones H2A/H2B and other chromatin-binding proteins, such as methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MeCP2) and DEK (23–28). By binding to both KSHV and cellular chromatin, LANA1 is thought to mediate the partitioning of latent KSHV genomes, but how these interactions facilitate partitioning and whether the partitioning is nonrandom and faithful as for cellular chromosomes have not been resolved.

The maintenance of latent KSHV genomes over the long term depends not only on the genome's ability to be synthesized and partitioned but also on an additional process called “establishment.” Early after introduction into cells, a majority of the plasmids are lost precipitously within the first 15 to 20 generations, such that only a small fraction of the initially infected cells go on to harbor the plasmids stably in the long term (29, 30). The process of establishment is not fully understood, but it appears to depend on the efficiency with which a plasmid can be synthesized and partitioned (31–34) and may involve epigenetic modifications to the viral genomes (30, 35).

KSHV genomes as measured in tumor biopsy specimens can have 16 to 50 tandem repeats of the TR (36–38), and the presence of as few as two copies of the TR appears to support establishment of KSHV-based plasmids in proliferating cells (12). Why then does KSHV have 16 to 50 copies of the TR? Two findings with EBV have suggested a plausible answer to this question. In EBV, Rep* acts as an auxiliary origin of Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA1)-dependent DNA synthesis (39). A single unit of Rep* can support DNA synthesis only in the short term, but an octamer of Rep* can support both the establishment and maintenance of the EBV DNA stably in the long term (40). Based on these findings with Rep*, we hypothesized that an increasing number of TRs provides KSHV plasmids a selective advantage by increasing the efficiency of their establishment. Further, a single MRE unit, in the absence of rest of the TR, can support the synthesis of the KSHV-based plasmids in transient assays (17). However, based on studies done with EBV, an origin that can support synthesis in transient assays may not support establishment and long-term maintenance of the plasmids (31). Whether the MRE is also sufficient for the establishment and long-term maintenance of the plasmid in addition to synthesis is not known.

To characterize the cis-acting elements involved in KSHV's establishment and long-term maintenance, we generated KSHV-based replicons containing different numbers of the TR or MRE units and assessed their abilities to give rise to drug-resistant colonies and be maintained in cells stably (i.e., without yielding rearrangements). We have found that tandem repeats of the MRE unit can indeed support establishment of KSHV-based plasmids. Additionally, we have identified two properties of the origin of latent replication that are essential for the efficient establishment and maintenance of the KSHV plasmids stably. The first is the requirement of approximately 16 copies of the TR, without which the plasmids are established inefficiently and are unstable, likely reflecting a defect in their ability to be partitioned. The second is the requirement of at least 2 units of the MRE separated by an 801-bp center-to-center spacing between each for optimal synthesis. Our studies show also that only the spacing between each MRE unit and not the actual sequence is important for the function of the TR as a maintenance element.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

Plasmids containing TRs are derived from 3919, a plasmid in which a multiple-cloning site has been introduced between the EcoRI and BamHI sites of pPUR DNA (Clontech Laboratories, Inc.). A plasmid containing 2 TRs was constructed by inserting 2 TRs between BamHI and NheI from Z6-2TR (12) into 3919. The 8-TR plasmid was constructed by inserting 8 TRs between the BsrGI and NheI sites from Z6-BE (12) into 3919. Plasmids containing 16 TRs were generated by multimerizing 8 TRs, flanked by NheI and SpeI sites, in the 8-TR plasmid by a previously described method (41).

Plasmids containing derivatives of MREs are based on plasmid 1782 (pcDNA3.1 from Invitrogen) and encode resistance to G418. Plasmid 4033, containing two copies of the 73-bp (bp 539 to 611) region of the TR encompassing the MRE, was constructed as a pIDTSMART-KAN minigene (IDT). Plasmids 4036 and 4037, containing 8 and 16 copies of the MRE, respectively, were constructed by multimerizing 2 MREs between XbaI and NheI in plasmid 4033. Fragments containing 2, 8, or 16 copies of the MRE between BglII and NheI sites in plasmids 4033, 4036, and 4037, respectively, were inserted into BglII and XbaI sites in 1782 to construct MRE plasmids. To generate the MRE-spacer plasmid, plasmid 4126, which contains two copies of the 73-bp (region from bp 539 to 611 of the TR) MRE separated by a 729-bp spacer sequence, was constructed as a pIDTSMART-KAN minigene (IDT). The 729 bp of spacer sequence consists of one NheI site followed by 723 bp of Enterobacteria phage λ DNA (GenBank accession no. J02459.1 [bp 5716 to 6438]) that cannot support replication in mammalian cells (FR-λ-Luc) (39). A fragment containing the MRE-spacer unit from 4126 was inserted between the EcorV and XbaI sites of 1782 to generate the MRE-spacer plasmid.

Plasmids containing FR are based on plasmid 994, which contains EBV OriP in a G418 resistance backbone. The 8-TR/FR, 2-MRE/FR, 8-MRE/FR, 16-MRE/FR, and MRE-spacer/FR plasmids were constructed by replacing the dyad symmetry (DS) between the SpeI and BamHI sites in plasmid 994 with 8 TRs between SpeI and BglII sites from the 8-TR plasmid, 2 MREs between BglII and NheI sites from plasmid 4033, 8 MREs between BglII and NheI sites from plasmid 4036, 16 MREs between BglII and NheI sites from plasmid 4037, and MRE-spacer between BamHI and XbaI from the MRE-spacer plasmid, respectively. The 2-TR/FR plasmid was constructed on a different vector, pLON-33k (42), which contains EBV OriP and lac operator (lacO) sites in a G418 resistance backbone. DS between SnaBI and SpeI sites in pLON-33k was replaced with 2 TRs between NheI and HpaI from Z6-2TR to generate plasmid 4067. 4067 was digested with XbaI to delete lacO repeats and ligated back to generate the 2-TR/FR plasmid. The 2-TR/FR plasmid is thus larger than the 8-TR/FR plasmid due to a different backbone.

Plasmids used to characterize the Gardella gel contain either OriP or FR from EBV in backbones of various sizes. These plasmids include p4151 (6.7 kb; the MRE-spacer/FR plasmid described above), p994 (7.5 kb), p4147 (20.7 kb), and p4066 (40 kb).

Cell lines.

The cell lines used for the replication assays include two PEL-derived cell lines, BCBL-1 and JSC-1; one epithelial cell line, SLK (43); and one human embryonic kidney-derived cell line, 293. Cell lines were cultured in either Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (SLK and 293) or RPMI 1640 medium (PELs) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 200 U/ml of penicillin, and 200 μg/ml of streptomycin sulfate at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. SLK/LANA cells that stably express LANA1 were generated by transducing SLK cells with a retroviral vector encoding LANA1 driven by a cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter and hygromycin B phosphotransferase. Selection with puromycin was performed at final concentrations of 1 μg/ml (SLK and BCBL-1) or 0.3 μg/ml (JSC-1); selection with G418 was performed at final concentrations of 800 to 1,250 μg/ml (SLK), 600 μg/ml (JSC-1), or 400 μg/ml (BCBL-1); selection with hygromycin was performed at a final concentration of 400 μg/ml (SLK).

Short-term replication assay.

SLK/LANA cells were cotransfected with 20 μg of sample plasmids (2-, 8-, and 16-TR or -MRE plasmids and plasmid 1782) and 3 μg of p2134 (enhanced green fluorescent protein [eGFP] expression vector) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies) as per the supplier's recommended protocol. At 4 days posttransfection, cells were harvested, and the percentage of GFP-positive cells was determined as a measure of the transfection efficiency. Low-molecular-weight DNA was isolated by the method of Hirt (44) with a few modifications and digested with 80 U of HindIII (plasmids with TRs) or XbaI (1782 and plasmids with MREs) overnight to linearize the plasmids. After the digestion was complete, 70% of the sample was digested with 120 U of DpnI overnight to digest bacterially methylated DNAs. Plasmids that have undergone at least one round of replication in the cells are resistant to digestion by DpnI. Complete digestions with both enzymes were ensured by parallel digestions of 1.5 μg test plasmid in 10-μl aliquots of each of the sample digests. Concentrations of 2 × 106 to 2.5 × 106 GFP-positive cell equivalents for positive (+) and negative (−) DpnI fractions of each sample were used for Southern blotting.

Colony formation assay for measurement of establishment efficiency.

Adherent cells (SLK) in 60-mm-diameter dishes were cotransfected using Lipofectamine with equimolar (approximately 3-μg) amounts of sample plasmids and 1 μg of p2134 (eGFP expression vector). A total of 107 PEL cells (JSC-1 and BCBL-1) were cotransfected with equimolar (approximately 10-μg) amounts of sample plasmids and 2 μg of p2134 by electroporation. One or 2 days posttransfection, the percentage of GFP-positive cells was determined as a measure of transfection efficiency, and adherent cells were plated at 104, 103, or 100 GFP-positive cells per 15-cm-diameter dish in triplicate for each dilution. PELs were plated at 103, 100, 10, or 1 GFP-positive cell per well of 96-well plates (48 wells for each dilution). Selection was applied for 3 to 4 weeks using an appropriate antibiotic (puromycin for the TR and pPUR plasmids and G418 for the MRE, TR/FR, MRE/FR, MRE-spacer, MRE-spacer/FR, 1782, and 994 plasmids), and the number of drug-resistant colonies (adherent cells) or the number of wells with drug-resistant cells (PELs) was counted to determine the CFU for each plasmid. For adherent cells, the CFU was measured as CFU = (no. of drug-resistant colonies/no. of GFP-positive cells plated) × 100%.

For PELs, the CFU was calculated using the Poisson distribution as CFU = {[−ln(no. of negative wells/total no. of wells)]/no. of cells per well} × 100%.

Statistical analysis.

Any relationship between the number of TRs or MREs and the CFU was tested using the Jonckheere-Terpstra statistic for trend, a nonparametric test for ordered differences between groups. A two-sided P value of ≤0.05 was assigned as statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using Mstat software, version 5.5 (N. Drinkwater, McArdle Laboratory for Cancer Research, School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Wisconsin) and is available for downloading at http://www.mcardle.wisc.edu/mstat.

Gardella gel.

Gardella gels were performed as described previously (45) with modifications (46). A horizontal 20- by 28-cm (width by length) gel was prepared consisting of (i) resolution gel made of 0.75% agarose in 1× Tris-borate-EDTA (pH 8.2) (TBE) buffer and (ii) lysis gel made of 0.8% agarose, 2% SDS, and 1 mg/ml proteinase K in 1× TBE buffer. The lysis gel occupied the top 5 cm of the horizontal gel and included 10- by 1- by 6-mm (width by depth by height) wells for loading samples. Cells resuspended in 50 μl resuspension buffer (7% Ficoll, 100 μg/ml RNase A, and 0.01% bromophenol blue in phosphate-buffered saline) were loaded into the wells and electrophoresed initially at 0.8 V/cm for 3 to 4 h and then at 4.5 V/cm for approximately 16 h at 4°C. Upon completion, the gel was stained with 0.5 μg/ml ethidium bromide (EtBr) in 1× TBE for 20 min, visualized under UV, and then analyzed by Southern blotting or with a second gel run at 90° to the first gel as described below. A total of 2 × 106 to 3 × 106 cells were used for Gardella gels unless otherwise noted.

2D gel.

The first dimension of the two-dimensional (2D) gel was a Gardella gel, performed as described above. Following the Gardella gel, the lane containing the desired sample was excised with minimal spacing around the lane. The fragment was then embedded into a 1× Tris-acetate-EDTA (TAE) gel with 0.6% agarose and 0.5 μg/ml EtBr on a 20- by 28-cm (width by length) gel tray such that the length of the fragment lies across the top of the gel, perpendicular to the direction of electrophoresis in the Gardella gel. This second gel was electrophoresed at approximately 1.5 V/cm for 20 to 24 h at room temperature. The gel was then analyzed by Southern blotting.

Isolation and digestion of total genomic DNA for Southern blotting.

For Southern blotting of plasmids in cells after long-term replication assays, total genomic DNA was isolated from approximately 3 × 107 cells. Pellets were resuspended in 5 ml of 0.15 M sodium acetate (pH 7.5 to 8.0) and lysed with an equal volume of lysis buffer (50 mM EDTA, 0.4 M sodium acetate, 2% SDS, and 1 mg/ml proteinase K) with minimal vortexing to prevent shearing of high-molecular-weight DNA. The samples were incubated at 45°C overnight and extracted sequentially with phenol and chloroform by rocking the samples for 2 to 4 h on a rotator, centrifuging them at 4,000 rpm for 30 min, and transferring them to new tubes using wide-bore pipette tips. The samples were then ethanol precipitated and resuspended in 2 ml Tris-EDTA (TE) at 4°C overnight. They were incubated with 0.1% SDS and 50 μg RNase A at 37°C for 2 h and then with 100 μg proteinase K at 45°C for 2 h. The samples were extracted with phenol and chloroform as described above, precipitated with ethanol, and resuspended in TE. Twenty-five to thirty percent of the isolated DNA from cells was digested with 120 U of HindIII (TR and pPUR plasmids) or XbaI (MRE plasmids and p1782) to linearize the plasmids, and the completion of digestion was ensured using a test plasmid in parallel digests as described above. Approximately 20 μg of digested DNA was loaded on a 0.8% agarose gel in 1× TAE buffer containing 0.5 μg/ml ethidium bromide and electrophoresed at 1.4 V/cm for 16 to 20 h for analysis by Southern blotting as described below.

Southern blotting.

Southern blotting was performed as described previously (31). DNA was denatured and transferred to Gene Screen Plus hybridization membrane (NEN Life Sciences) using 10× SSC (1.5 M NaCl, 150 mM sodium citrate [pH 7]). A 32P-radiolabeled probe was prepared using the Rediprime II random prime labeling system (GE Healthcare) and hybridized to the membrane in ULTRAhyb hybridization buffer (Ambion). The hybridized membrane was exposed to a storage phosphor screen, and the signals were captured using Storm 860 PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics). TR and pPUR plasmids were detected with pPUR DNA; the MRE, TR/FR, MRE/FR, MRE-spacer, MRE-spacer/FR, and 1782 plasmids were detected with 1782 (pcDNA3.1) DNA, unless otherwise noted. Quantification of signals in Southern blots was done using ImageJ software (NIH). The final intensity for any particular signal was obtained by subtracting the neighboring background intensity within the same lane.

RESULTS

Increasing the numbers of TRs increases the efficiencies of synthesis and establishment supported by KSHV plasmids.

We constructed KSHV-based plasmids containing 2, 8, or 16 copies of the TR and measured their abilities to support synthesis by performing short-term replication assays in SLK cells stably expressing LANA 1 (SLK/LANA). We found a positive correlation between the number of TRs and the efficiency of synthesis (Fig. 1A and B). Additionally, we also observed that plasmids with higher numbers of TRs are preferentially synthesized when a heterogeneous mixture of plasmids containing different numbers of TRs is introduced into cells. Plasmids with multiple copies of TRs from KSHV are unstable in Escherichia coli, likely due to their high GC content and repetitiveness. We have propagated plasmids containing TRs in eight strains of E. coli variously deficient in recombination. Plasmids harvested from all strains displayed heterogeneity in the number of TRs they contained. A single clonal E. coli population obtained after transformation with homogeneous plasmid DNA, containing 16 TRs, for example, harbored a mixture of plasmids with 16 or fewer TRs (Fig. 1A) (data not shown). When this heterogeneous population of plasmids was introduced into SLK/LANA cells, the plasmids with higher numbers of TRs were preferentially synthesized, as shown by an enrichment of the larger plasmids over smaller plasmids in the DpnI (+) lane (Fig. 1A and C). Given that the synthesis of KSHV genomes is licensed (22), these observations likely indicate that a higher number of TRs provides KSHV plasmids with an increased probability that they will undergo synthesis.

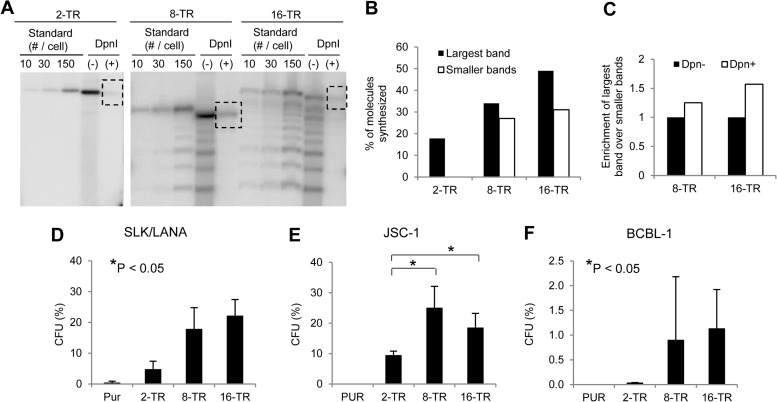

FIG 1.

Efficiencies of short-term replication and establishment of KSHV-based plasmids with various numbers of TRs. (A) Southern blot analysis of a short-term replication assay of 2-, 8-, and 16-TR plasmids in SLK/LANA cells performed 4 days posttransfection. DpnI (−), DNA from ∼2 × 106 GFP-positive cell equivalents digested with HindIII but not with DpnI; DpnI (+), HindIII- and DpnI-digested DNA from ∼2 × 106 GFP-positive cell equivalents. Dotted boxes indicate bands obtained for DpnI-resistant replicated DNA. The standards were free parental plasmids digested with HindIII and loaded at 10, 30, or 150 plasmids per cell calculated for ∼2 × 106 cell equivalents. Multiple bands in the lanes for the 8- and 16-TR DNAs were derived by recombination of the parental plasmids in E. coli. The largest bands in these lanes have 8 or 16 TRs, while the smaller bands have fewer than 8 or 16 TRs, respectively. The probe was pPUR (backbone of TR plasmids). (B) Quantification of signals in panel A. The percentage of synthesized DNA for each TR plasmid was calculated by measuring the intensities of the bands corresponding to total and replicated DNA in the (−) and (+) DpnI lanes, respectively, using the ImageJ program (NIH). White bars represent the synthesis of plasmids with fewer than 8 or 16 TRs in the lanes with 8- and 16-TR plasmids, respectively. (C) Enrichment of the largest plasmids over smaller plasmids in the lanes for 8- and 16-TR plasmids in panel A. Ratios of signal intensities of the largest band to the smaller bands were calculated in the (+) and (−) DpnI lanes, and the ratio in the (−) DpnI lane was set to 1. (D, E, and F) Establishment efficiencies of 2-TR, 8-TR, and 16-TR plasmids expressed as CFU in SLK/LANA (D), JSC-1 (E), and BCBL-1 (F) cells. CFU was determined as the percentage of transfected cells resulting in puromycin-resistant colonies ∼3 weeks posttransfection. Cells transfected with pPUR (Clontech) were used as the negative control. The error bars represent the standard deviations obtained from three independent experiments. Correlation analysis was performed using the Jonckheere-Terpstra test for a trend for increasing CFU, and statistically significant (P ≤ 0.05) trends (D and F) and differences (E) are indicated and marked with asterisks.

We also measured the abilities of these plasmids to support establishment using colony formation assays. In addition to SLK/LANA cells, we performed assays in JSC-1 and BCBL-1 cells, primary effusion lymphoma (PEL)-derived cell lines harboring endogenous KSHV genomes, to simulate the environment in which KSHV plasmids are maintained in vivo. We cotransfected cells with a GFP expression plasmid and equal amounts of 2-, 8-, or 16-TR plasmids. Two days posttransfection, the cells were plated at various dilutions of the GFP-positive cells and cultured for approximately 3 weeks in puromycin-containing media. The CFU (percentage of successfully transfected cells that can give rise to drug-resistant colonies) was used as a measure of efficiency of establishment for each of the plasmids. In SLK/LANA and BCBL-1 cells, we observed a positive correlation (P < 0.05) by Jonckheere Terpstra test between the number of TRs per plasmid and the efficiency of establishment they support (Fig. 1D and F). In JSC-1 cells, plasmids with 8 and 16 copies of the TR were established with significantly higher efficiencies (P < 0.05) than those with 2 copies of the TR (Fig. 1E). It is important to note that the CFU for 2- and 8-TR plasmids observed here likely deviate from their actual establishment efficiencies due to recombination events of unknown frequencies (shown below). Thus, these observed efficiencies for 2- and 8-TR plasmids should be viewed as overestimates of the establishment efficiencies of the unrecombined, parental plasmids. The average efficiencies of establishment of 16-TR plasmids, for which the observed CFU more accurately reflect the actual establishment efficiency, varied between the recipient cell lines with SLK and JSC-1 supporting about 20-fold-higher efficiencies than BCBL-1 cells.

Plasmids with 16 copies of the TR are stable, while those with 2 and 8 copies of the TR are often maintained only as recombinants.

We performed Gardella gels to determine the extrachromosomal status and structure of the TR plasmids in cells after establishment. Gardella gels involve the lysis of live cells in the wells of the gel and allow separation of extrachromosomal and chromosomal DNAs upon electrophoresis (45). We characterized this technique to inform our experiments by analyzing the migration patterns of various forms of plasmids of different sizes from different numbers of cells (Fig. 2). We found that the covalently closed circular (CCC) form of plasmids derived from in situ lysis of cells can migrate as two distinct bands in a Gardella gel (Fig. 2A and B). A faster-migrating band (band a) and a slower-migrating band (band b) observed for a plasmid 4151 from JSC-1 cells (Fig. 2A), were both confirmed to be the CCC form of the plasmid by a 2D analysis following the Gardella gel (Fig. 2B). Both the CCC and nicked forms of plasmids derived from cells migrate more slowly than those of free plasmids, and this difference becomes greater as more cells are used in Gardella gels (Fig. 2C and D). The slower migration is likely a result of delayed exit of the plasmids from cells due to their gradual in situ lysis and increased viscosity from the increased number of cells. The migration of plasmids became aberrant at more than 3 × 106 cells; thus, we have used up to 3 × 106 cells in all of our Gardella gel analyses. We extended this study to 293 cells newly transfected with plasmids of various sizes and found a similar trend (Fig. 2E) (data not shown). Under the conditions of the Gardella gels we used in this study, plasmids of all sizes derived from up to 3 × 106 cells migrate between 77 and 100% as far as the free parental plasmids of the same size. Plasmids that are retarded by more than 23% relative to their free parental plasmids under these conditions therefore represent distinct, larger species.

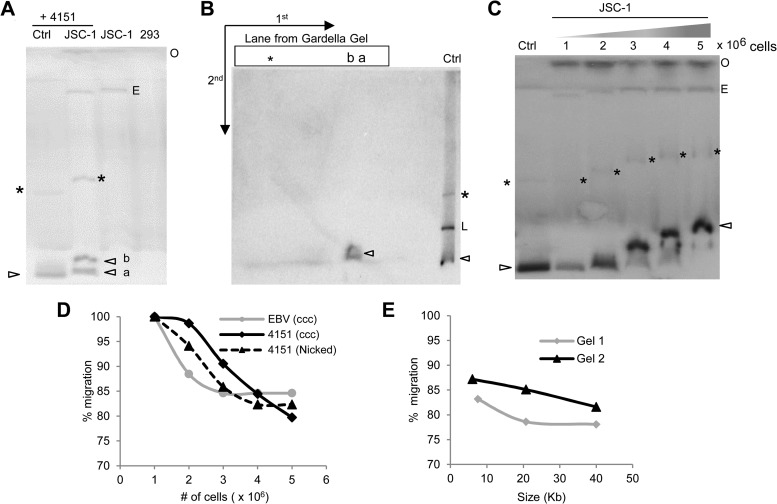

FIG 2.

Characterization of Gardella gels. (A) Gardella gel showing migration of plasmid DNA derived from in situ lysis of JSC-1 cells. Ctrl (control), 0.3 ng of free parental plasmid p4151; JSC-1 + 4151, ∼3 × 106 JSC-1 cells harboring established p4151 (6.7-kb) plasmid; O, position of wells; *, nicked circle form of the plasmid; L, linear DNA; arrowhead, covalently closed circular (CCC) form of the plasmid. CCC DNA from cells migrates as 2 bands: a faster-migrating band (a) and a slower-migrating band (b). E, CCC DNA of ∼ 170-kbp endogenous EBV plasmids. The probe was an ∼1.7-kb OriP fragment. (B) 2D gel of JSC-1 cells harboring p4151 showing that bands a and b in panel A are both derived from the CCC form of the plasmid and are of the same size. In the first dimension (1st), p4151 was run on a Gardella gel as for panel A. In the second dimension (2nd), the corresponding lane from the Gardella gel was embedded in a 1× TAE gel and electrophoresed perpendicular to the first dimension, as shown. Ctrl, mixture of plasmid and linearized forms of p4151 loaded at the beginning of the 2nd gel. (C) Gardella gel of various numbers of JSC-1 cells harboring p4151 showing that plasmids from cells have reduced mobility likely due to viscosity of the cells. Ctrl, 0.3 ng of free parental plasmid p4151. (D) Migration of plasmids in Gardella gels as a function of cell number, measured from panel C. Distances from the wells migrated by different DNAs, including the CCC and nicked forms of p4151 and the CCC form of EBV were measured. The percentage of migration indicates the distance moved by cell-derived plasmids expressed as a percentage of the distance moved by the same DNA/form in the Ctrl lane. (E) The difference in the migrations of cell-derived plasmids and their corresponding free parental plasmids is greater for larger plasmids. Plasmids of various sizes from newly transfected 293 cells were run on Gardella gels, and their migration from ∼3 × 106 cells compared to that for free parental plasmids was measured. Gel 1 was electrophoresed for approximately 2 h longer than gel 2.

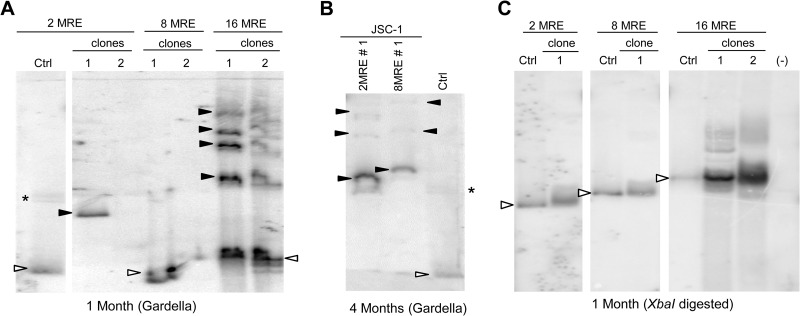

Gardella gels of some selected clones of JSC-1 cells harboring TR plasmids showed that these plasmids were present as extrachromosomal DNAs (Fig. 3A). Clones of JSC-1 cells transfected with 2- and 8-TR plasmids often harbored plasmid DNAs that were larger than the size of the plasmids that were initially introduced into them (Fig. 3A, clones 2-TR 4 and 8-TR 3). These larger species are not aggregates of smaller plasmids produced as artifacts of the Gardella gel technique, as confirmed by probing for mitochondrial DNA in the same cells, which migrated as DNAs of approximately 16 kbp (data not shown). This observation indicates that these larger, recombined species have a selective advantage in the recipient cells. In contrast to 2- and 8-TR plasmids, 16-TR plasmids were stable in that they were the same size as the parental DNA in all clones tested and lacked detectable rearranged products (Fig. 3A and Table 1). Similar results were obtained when we examined bulk populations of SLK/LANA and BCBL-1 cells harboring the TR plasmids (Table 1) (data not shown). To gain insights into the structures of the recombined plasmids, we isolated total genomic DNA from the cells 1 month posttransfection and performed Southern blot analyses after digesting them with an enzyme (HindIII) having a unique site in the plasmids (Fig. 3B). Some of the recombined plasmids had gained an additional HindIII site (Fig. 3B, clone 2-TR 4), while some did not (Fig. 3B, clone 8-TR 3). In both of these cases, digestion with HindIII did not yield unit-length DNAs of the expected sizes. In contrast, plasmids from cells transfected with 16-TR plasmids gave the expected unit-length DNAs (Fig. 3B, 16-TR clones).

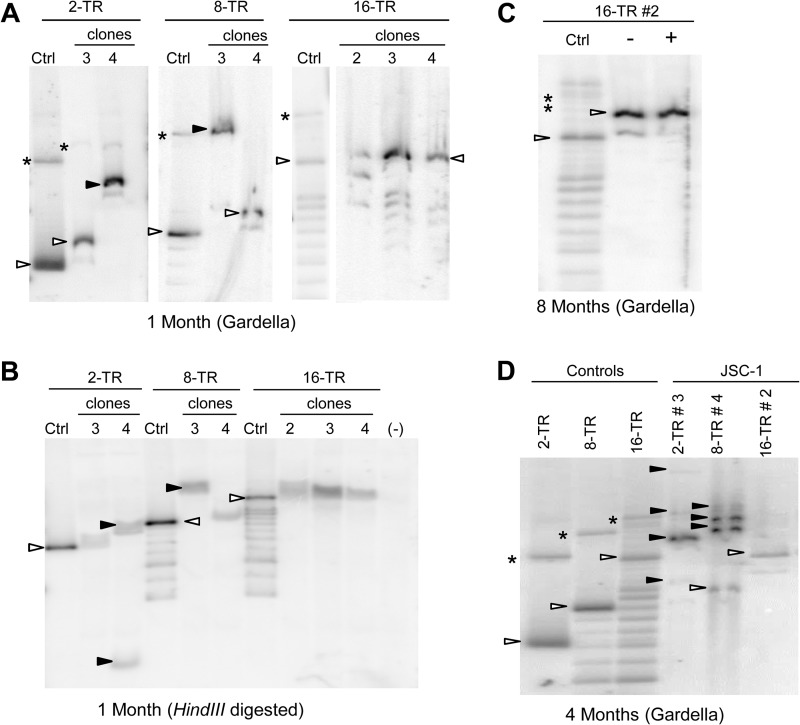

FIG 3.

Larger plasmids produced by recombination of 2- and 8-TR plasmids are selected during establishment in JSC-1 cells. (A) Gardella gels of representative clones of puromycin-resistant JSC-1 cells 1 month after transfection with 2-, 8-, or 16-TR plasmids. (Control and sample lanes for the 16-TR plasmid are from the same gel.) Ctrl, 0.3 to 1.5 ng of free parental plasmids corresponding to each TR plasmid; open arrowheads, bands obtained from CCC DNA of the free parental plasmid or from plasmids from cells that are the same size as the parental plasmid; closed arrowheads, bands obtained for CCC DNA of demonstrably larger, recombined plasmids from cells; *, nicked form of plasmids in control and sample lanes when distinctly detected. Multiple bands in the control lanes for 8- and 16-TR DNAs below the open arrowheads are derived by recombination of the parental plasmids in E. coli. (B) Southern blot analysis of the total genomic DNA from cells in panel A isolated 1 month posttransfection and digested with a single cutter enzyme (HindIII) of the plasmids. Control (Ctrl) lanes, 0.3 to 1.5 ng of free parental plasmids digested with HindIII; open arrowheads, bands in the ctrl lane that represent the expected migration of HindIII-digested parental TR plasmids; closed arrowheads, fragments of recombined plasmids from cells generated by HindIII digestion; (−), nontransfected parental cells. (C) Gardella gel of JSC-1 cells, clone 16-TR 2, 8 months posttransfection grown with or without G418. In the – lane, cells were grown in the absence of G418 for 2 months and then grown in limited dilution for a month after reintroduction of G418. In the + lane, cells were grown continuously in the presence of G418. (D) Gardella gel of cells in panel A 4 months posttransfection. Clones 2-TR 3 and 8-TR 4 have recombined, producing larger species at this time. The probe was pPUR (backbone of TR plasmids).

TABLE 1.

Replicons with MREs and 2 or 8 copies of the TRs are often rearranged and/or integrated

| Type of plasmid | No. of clones: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Testeda | With rearranged plasmidsb | With integrantsc | |

| 2-TR | 8 | 5 | 3 |

| 8-TR | 10 | 8 | 2 |

| 16-TR | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| 2-MRE | 5 | 3 | 2 |

| 8-MRE | 4 | 3 | 1 |

| 16-MRE | 6 | 3 | 3 |

Clones from SLK, JSC-1, and BCBL-1 cells.

Results from Gardella gels and/or Southern blot analyses of DNAs isolated from cells at 1 to 8 months posttransfection.

Clones that continue growing in the presence of antibiotic selection provided by the plasmids, yet have no detectable presence of extrachromosomal DNAs by Gardella gel analyses when probed for the plasmid backbone of each plasmid.

In order to test further the finding that 16-TR plasmids are structurally stable, we subjected clone 16-TR 2 of JSC-1 cells to further selective pressure by removing antibiotic selection from the culture media for 2 months and then subcloning the cells in the presence of selection. If this clone contained minor, recombined species below the level of detection at earlier time points, the absence and then subsequent reintroduction of selection could provide such minor species an opportunity to expand in the cell population above the detection limit. A Gardella gel performed on the subcloned cells a month after reintroduction of selection (8 months posttransfection) showed no evidence of recombination or change in the composition of plasmids (Fig. 3C). Consistent with our observation from short-term replication assays, we observed a preferential establishment of plasmids with higher numbers of the TRs when a heterogeneous population of plasmids containing various numbers of the TR was introduced into cells. This effect was most apparent for samples containing 16-TR plasmids (Fig. 3A, B, and C).

2- and 8-TR plasmids continue to recombine and yield larger molecules after establishment.

It has been shown that introduction of DNA into mammalian cells through transfection promotes recombination (47, 48). We therefore asked if the recombined, larger plasmids derived from those initially having 2 or 8 copies of TRs formed during transfection or continued to be formed and selected over time. One month after transfection is sufficient for the detectable presence of recombined plasmids with selective advantages; therefore, any species that is detectable only at time points beyond 1 month should represent recombinants that were formed subsequent to transfection. Clones of cells with apparently homogeneous 2-TR and 8-TR plasmids at 1 month posttransfection yielded cells with larger, recombined plasmids at 4 months posttransfection, while those with 16-TR plasmids carried similarly didn't harbor any recombined species (Fig. 3D). The clones with recombined plasmids contained multiple species, the majority of which were larger than the parental plasmids. Clone 8-TR 4 also contained nonrecombined 8-TR plasmid, albeit as a minor species. Similar changes were observed in SLK/LANA and BCBL-1 cell populations harboring 2- and 8-TR plasmids (data not shown). Some of the cells with 2- or 8-TR plasmids evolved to harbor these plasmids as integrants at a later time point (Table 1), as evidenced by their continued growth in the presence of antibiotic but lack of detectable presence of extrachromosomal DNAs by Gardella gel analyses (data not shown). This observation suggests that integration occurs and maintains these KSHV plasmids more efficiently than extrachromosomal replication even after establishment. These findings indicate not only that the recombined, larger plasmids continue to be formed over time but also that the cell populations harboring them evolve in a dynamic process favoring recombined species that are selected for.

Based on our observations that (i) the recombined species selected over time are larger than the input parental plasmids, (ii) the plasmids with higher numbers of TRs are preferentially synthesized and established when a mixture of plasmids with various numbers of the TR is introduced into cells, and (iii) plasmids with 16 copies of the TR are structurally stable, we favor the notion that the recombined species derived from parental plasmids with 2 or 8 TRs have an increased number of TRs, potentially approaching 16 per molecule.

Efficiency of transient replication of KSHV genomes is independent of the number of MRE units.

A single unit of the 71-bp MRE within the TR can support synthesis of KSHV plasmids in transient assays (17). We therefore asked whether the ability of MREs to support synthesis also increases with the number of MREs per replicon. We constructed plasmids containing 2, 8, or 16 tandem repeats of the MREs (Fig. 4A) and measured their abilities to support synthesis by performing short-term replication assays in SLK/LANA cells (Fig. 4B). Unlike the plasmids with intact TRs, the efficiency of synthesis of MRE-containing plasmids did not correlate with the number of MREs per plasmid. This observation suggests that even though the MRE is the minimal element that can support synthesis, the additive effect of additional MREs on synthesis can only be obtained when the MREs are present in the context of intact TRs.

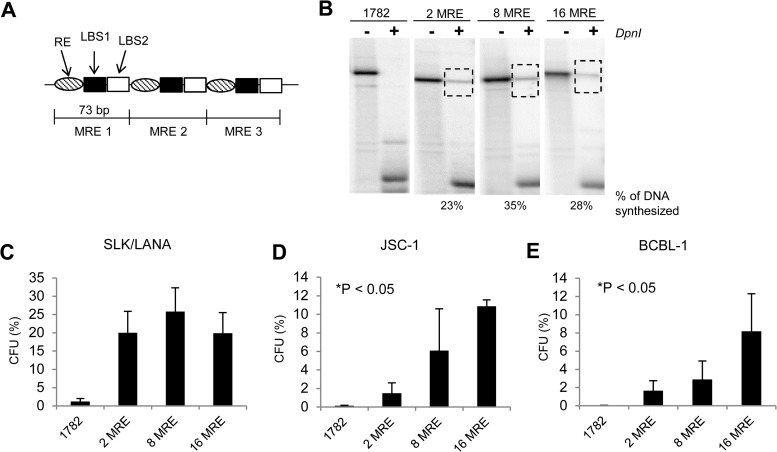

FIG 4.

Efficiencies of short-term replication and establishment of KSHV-based plasmids with various numbers of MREs. (A) Schematic representation of the plasmids with MREs. The 73-bp units of the TR (bp 539 to 611) containing MRE are repeated in a head-to-tail fashion without any spacing between each unit. (B) Southern blot analysis of a short-term replication assay of 2-, 8-, and 16-MRE plasmids in SLK/LANA cells performed 4 days posttransfection. –DpnI, DNA from ∼2 × 106 GFP-positive cell equivalents digested with XbaI but not with DpnI; +DpnI, XbaI- and DpnI-digested DNA from ∼2 × 106 GFP-positive cell equivalents. The dotted boxes indicate bands obtained for DpnI-resistant replicated DNA. The numbers below the Southern blot represent the percentage of synthesized DNA for each MRE plasmid, calculated by measuring the intensities of the bands corresponding to total and replicated DNA in the − and + DpnI lanes, respectively, using the ImageJ program (NIH). The probe was p1782 (backbone of MRE plasmids). (C, D, and E) Establishment efficiencies of 2-MRE, 8-MRE, and 16-MRE plasmids expressed as CFU in SLK/LANA (C), JSC-1 (D), and BCBL-1 (E) cells. CFU was determined as a percentage of transfected cells resulting in G418-resistant colonies 1 month posttransfection. Cells transfected with p1782 (pcDNA3.1 from Invitrogen) were used as a negative control. The error bars represent standard deviations obtained from three independent experiments. Correlation analysis was performed using the Jonckheere-Terpstra test for a trend for increasing CFU, and statistically significant (P ≤ 0.05) trends are indicated and marked with asterisks.

Increasing numbers of MREs support increasing efficiencies of establishment.

Studies from EBV show that an origin that can support synthesis in the short term may not support establishment. Raji ori, a second viral origin of replication of EBV that is used predominantly for its maintenance in Raji cells, is unable to support the establishment of EBV genomes even though it can support maintenance of EBV genomes once established (31). We therefore determined whether the MRE of KSHV, in addition to supporting synthesis in the short term, also supports the establishment and long-term maintenance of KSHV genomes. We performed colony formation assays of plasmids containing 2, 8, and 16 tandem repeats of MREs in JSC-1, BCBL-1, and SLK/LANA cells and found that all three MRE-plasmids can be established in all three cell lines (Fig. 4C, D, and E). The efficiency of establishment was positively correlated with the number of MREs in the two PEL cell lines (P < 0.05) but not in SLK/LANA cells. It is important to note, however, that all three MRE plasmids underwent recombination of unknown frequencies (shown below); hence the CFU observed here are likely overestimates of the efficiencies of establishment of the unrecombined parental plasmids.

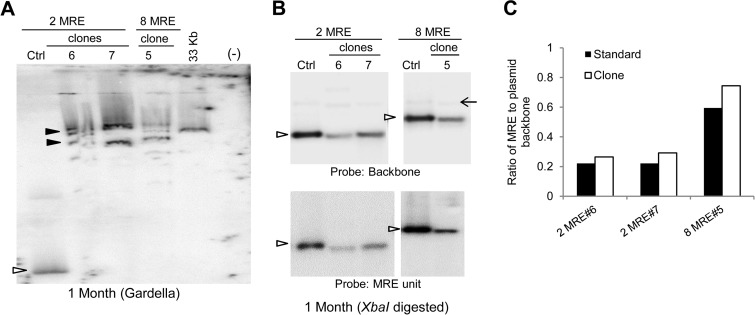

Tandem repeats of 16 MREs are not sufficient for the stable maintenance of KSHV-derived plasmids.

Representative clones of cells obtained 1 month after transfection with MRE plasmids were analyzed by Gardella gels, which showed not only that the MRE plasmids were maintained extrachromosomally but also that they frequently recombined, producing larger species that became established (Fig. 5A and 6A). Similar to plasmids with 2 and 8 copies of the TR, plasmids with MREs also continued to recombine postestablishment, producing larger and heterogeneous species (Fig. 5B). In some instances, cells harboring MRE plasmids evolved to maintain them as integrants (Fig. 5A, clone 2 for the 2- and 8-MRE lanes; Table 1).

FIG 5.

MRE plasmids are maintained in the long-term extrachromosomally, but larger recombinants are often selected. (A) Gardella gel of representative clones of G418-resistant JSC-1 cells 1 month posttransfection with 2-, 8-, or 16-MRE plasmids. All lanes are from the same gel. Ctrl (control), 0.3 to 0.5 ng of free parental plasmids. The sizes of the 2-, 8-, and 16-MRE plasmids vary by only ∼500 bp; hence, only one of these plasmids is used as the parental plasmid in the control lane. Open arrowheads, bands obtained from CCC DNA of the free parental plasmid or from plasmids from cells that are the same size as the parental plasmid; closed arrowheads, bands obtained for CCC DNA of larger, recombined plasmids from cells; *, nicked form of the control plasmids. No signals can be detected in the 2- and 8-MRE clones 2 even after multiple Gardella gel analyses. (B) Gardella gel of cells in panel A 4 months posttransfection. Clone 2MRE1 has become heterogeneous, and clone 8MRE1 has recombined, producing larger species at this time. (C) Southern blot analyses of the total genomic DNA from cells in panel A isolated 1 month posttransfection and digested with a single cutter enzyme (XbaI) of the plasmids. All lanes are from the same gel. Ctrl, 0.3 to 0.5 ng of parental plasmids digested with XbaI; open arrowheads, bands in the Ctrl lane that represent the expected migration of the XbaI-digested parental MRE DNA; (−), nontransfected parental cells. The probe was p1782 (backbone of MRE plasmids).

We analyzed the structures of the larger plasmids at 1 month posttransfection by Southern blotting of the total genomic DNA after linearization of the plasmid DNAs with XbaI (Fig. 5C and 6B). A majority of recombined plasmids when digested with XbaI yielded unit-length DNAs of the expected size, similar to the parental plasmids, indicating that the recombined plasmids were head-to-tail concatemers of the input MRE plasmids. We measured the ratio of MRE units to the plasmid backbone in recombined plasmids from SLK/LANA cells by quantifying the signals obtained by probing for either the MRE unit or the plasmid backbone (Fig. 6B and C). We found that the ratio of MRE to backbone DNA in recombined plasmids is similar to that in unit-length parental plasmids (Fig. 6C), thus confirming that the recombined plasmids are concatemers of the input MRE plasmids and have more MREs per plasmid molecule relative to the input plasmids. Hence, as is the case with 2- and 8-TR plasmids, the establishment efficiencies obtained for the MRE plasmids are overestimates of their actual efficiencies as a result of concatemerization and other recombination events of unknown efficiencies.

FIG 6.

MRE plasmids are present as concatemers in cells. (A) Gardella gel of representative clones of G418-resistant SLK/LANA cells 1 month posttransfection with 2- and 8-MRE plasmids. Ctrl, 0.3 to 0.5 ng of free parental plasmids; open arrowhead, bands obtained from CCC DNA of the free parental plasmid; closed arrowheads, bands obtained for CCC DNA of demonstrably larger recombined plasmids from cells; (−), nontransfected parental cells; 33 Kb, 33-kb plasmid (pLON-33K, see Materials and Methods) used as a size marker. The probe was p1782. (B) Southern blot analyses of the total genomic DNA from cells in panel A isolated 1 month posttransfection and digested with a single cutter enzyme (XbaI) of the plasmids. Ctrl, 0.3 to 0.5 ng of parental plasmids digested with XbaI; open arrowheads, bands in the Ctrl lane that represent the expected migration of the XbaI-digested parental MRE DNA. The upper panel was probed with p1782 (backbone of MRE plasmids), and the lower panel was probed with approximately 150 bp of 2 MRE units obtained by NheI/BglII digestion of the 2-MRE plasmid. The same amounts of DNA were loaded onto both panels. Arrow, unspecific band. (C) Ratio of MRE to backbone sequence in MRE plasmids measured from panel B. Band intensities of MRE units (lower panel) and backbone DNA (upper panel) in panel B were measured using the ImageJ program (NIH), and the ratios of MRE to backbone DNA were obtained for control DNA (Standard) and DNAs from cells (Clone). The ratios of MRE to backbone sequence for all plasmids from cells are similar to those for control plasmids, showing that the larger plasmids are recombined head-to-tail concatemers.

Interestingly, unlike plasmids with 16 TRs, which were maintained stably (Fig. 3), plasmids with 16 MREs were unstable and recombined to yield larger plasmids, often heterogeneous in size. This finding indicates that tandem repeats of 16 MREs cannot support maintenance stably, suggesting that they are deficient in some aspect of maintenance compared to the TRs.

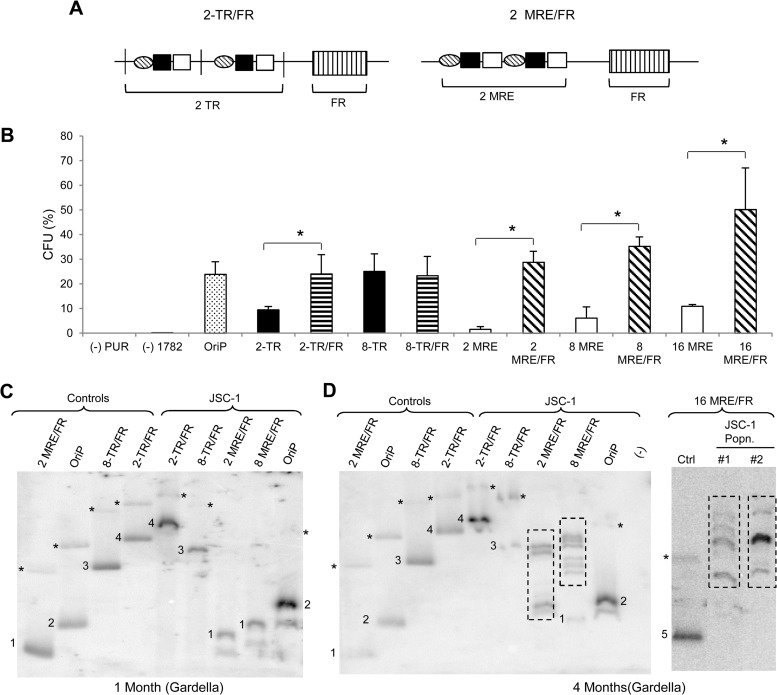

Addition of FR limits the instability of plasmids containing 2 and 8 copies of TRs but not of those containing MREs.

Plasmids with MREs and lower numbers of TRs support synthesis less efficiently than those with 16 TRs (Fig. 1 and 4). Hence, the inability of plasmids with MREs and lower numbers of TRs to be maintained stably could be due to defects in their synthesis. Additionally, these plasmids might also have defects in their partitioning abilities. Maintenance of latent EBV genomes is mediated by two distinct elements in its OriP: the dyad symmetry (DS) and the family of repeats (FR). Four specifically positioned EBNA1-binding sites in the DS mediate synthesis of the EBV genomes, while 20 EBNA1-binding sites in the FR mediate tethering to chromosomal DNAs, which is thought to be required for partitioning of EBV genomes (32, 33, 49–52). It is plausible that similar to 20 EBNA1-binding sites in the FR of EBV, approximately 16 pairs of LANA-1 binding sites in the TRs of KSHV are required for efficient partitioning of KSHV genomes. We thus asked whether the instability of plasmids with MREs and 2 or 8 TRs resulted from defects in their partitioning abilities.

Elements supporting synthesis and partitioning of KSHV are not distinct as those in EBV. To uncouple these processes in KSHV-derived plasmids, we generated hybrid plasmids by introducing FR from EBV into plasmids with 2 or 8 copies of TRs or MREs (Fig. 7A). FR on binding EBNA1 mediates the partitioning of plasmids but not their synthesis, potentially complementing any partitioning defects that plasmids with low numbers of TRs or MREs might have. Colony formation assays performed in JSC-1 cells (dually positive for KSHV and EBV) revealed that the presence of FR in cis increased the efficiency with which 2 TRs supported establishment (P < 0.05) (Fig. 7B). In addition, the presence of FR also rendered plasmids with both 2 and 8 TRs stable: that is, they did not yield larger, recombined plasmids over time (Fig. 7C and D). This finding indicates that plasmids with few copies of TRs are established with low efficiencies and are structurally unstable because they have defects in partitioning. Hybrid plasmids with 2, 8, or 16 copies of the MRE, on the other hand, were not completely rescued by the presence of FR. The MRE plasmids were established approximately 5-fold more efficiently in the presence of FR than in its absence (Fig. 7B) but recombined to yield larger species over time (Fig. 7C and D). This finding indicates that although MREs have defects in partitioning similar to plasmids with few copies of TRs, they also have some defect in replication not shared with the TRs.

FIG 7.

Addition of FR in cis to plasmids with TR or MRE. (A) Schematic representation of 2-TR and 2-MRE plasmids with FR. (B) Establishment efficiencies of TR and MRE plasmids in the presence or absence of FR in JSC-1 cells expressed as CFU. CFU was determined as a percentage of transfected cells resulting in drug-resistant colonies. OriP, plasmid containing EBV's origin of latent replication, used as a positive control. pPUR (empty vector expressing puromycin resistance from Clontech) and 1782 (pcDNA3.1 from Invitrogen expressing G418 resistance) DNAs were used as negative controls. The error bars represent standard deviations obtained from three independent experiments. Statistically significant (P ≤ 0.05) differences as determined by the Jonckheere-Terpstra test are indicated and marked with asterisks. (C and D) Gardella gels from populations of drug-resistant JSC-1 cells 1 month (C) and 4 months (D) after transfection with TR/FR or MRE/FR plasmids. We have numbered signals from CCC DNA corresponding to the same size in control and sample lanes for clarity. (−), nontransfected parental cells; Ctrl (control), 0.3 to 0.5 ng of free parental plasmids. The 2- and 8-MRE/FR plasmids vary by ∼500 bp; hence, only one is used as the input parental plasmid in the control lane. *, nicked forms of the plasmids in the sample and control lanes when detected. Dotted boxes indicate bands obtained for recombined plasmids from cells. The parental 2-TR/FR plasmid is bigger than the 8-TR/FR plasmid due to the different sizes of the backbones of these plasmids (see Materials and Methods). The probe was p1782 (backbone of the plasmids).

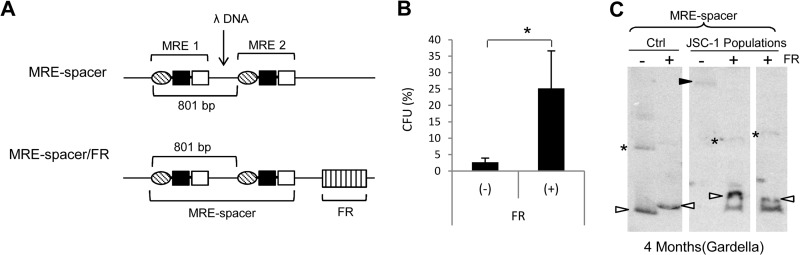

The 801-bp spacing between each MRE unit is essential for the stable maintenance of KSHV plasmids.

MRE plasmids differ from TR plasmids in that they lack the DNA sequence between each unit of the MRE. The defect in replication exhibited by the MRE plasmids even when complemented with FR could be due to the absence of an unidentified element in the region of the TR outside the MRE. Alternatively, the defect could be due to the absence of an 801-bp center-to-center spacing between each MRE unit. We explored the latter possibility by generating the MRE-spacer plasmid containing a spacer sequence derived from DNA of phage λ between 2 MRE units such that the center-to-to center spacing between each MRE unit becomes 801 bp (Fig. 8A). We performed colony formation assays with the MRE-spacer plasmid in the presence or absence of FR in cis. While the MRE-spacer plasmid supported a low level of establishment and exhibited instability similar to those of the 2-TR and 2-MRE plasmids, the addition of FR increased its establishment efficiency and also rendered the plasmid stable (Fig. 8B and C). This observation not only indicates that the 801-bp spacing between each MRE unit is essential for the stable maintenance of KSHV plasmids but also suggests that the actual sequence between the MRE units does not play an active role in the maintenance of KSHV genomes.

FIG 8.

MRE plasmids with a spacer sequence between 2 MRE units are stable in the presence of FR. (A) Schematic representation of MRE-spacer and MRE-spacer/FR plasmids. DNA from Enterobacteria phage λ was inserted between 2 MREs such that the center-to-center spacing between them becomes 801 bp. (B) Establishment efficiencies of the MRE-spacer plasmid in the presence or absence of FR in JSC-1 cells expressed as CFU. CFU was determined as a percentage of transfected cells resulting in drug-resistant colonies. The error bars represent standard deviations obtained from three independent experiments. A statistically significant (P ≤ 0.05) difference as determined by the Jonckheere-Terpstra test is indicated and marked with an asterisk. (C) Gardella gel from populations of G418-resistant JSC-1 cells 4 months after transfection with MRE-spacer plasmid with or without FR. All lanes are from the same gel. The two sample lanes for the +FR group represent separate populations of JSC-1 cells from two independent transfections. Ctrl (control), 0.3 to 0.5 ng of free parental plasmids; open arrowheads, bands obtained from CCC DNA of the free parental plasmid or plasmids from cells that are the same size as the parental plasmid; closed arrowhead, band obtained for CCC DNA of larger, recombined plasmids from cells; *, nicked forms of the plasmids in control and sample lanes when detected. The probe was p1782 (backbone of the plasmids).

DISCUSSION

We have generated plasmid derivatives of KSHV varying in both the number and the structure of its latent origin of replication to define elements required for the efficient establishment and stable long-term maintenance of KSHV genomes. We measured each plasmid's ability to support establishment and maintenance efficiently and stably as (i) its ability to give rise to drug-resistant colonies in colony-forming assays and (ii) its ability to be maintained in cells without yielding rearrangements displaying selective advantages.

We have found that increasing the number of TRs per replicon provides a selective advantage to the replicon by increasing its abilities to support synthesis, establishment, and structurally stable maintenance over the long term. This conclusion is supported by four lines of evidence. First, increasing numbers of TRs support increasing efficiencies of synthesis (Fig. 1A to C). Second, the number of drug-resistant colonies that grew out in colony formation assays generally increased with an increasing number of TRs (Fig. 1D to F). Third, plasmids with higher numbers of TRs were both selectively synthesized and established when a heterogeneous mix of plasmids with various numbers of TRs was introduced into human cells (Fig. 1 and 3). Fourth, plasmids with initially 16 copies of the TR were stable and maintained their size during and after establishment, while those with initially 2 or 8 copies of the TR were unstable (i.e., they often recombined, producing larger molecules that were selected for over time) (Fig. 3). We think it likely that the larger molecules derived from those initially having 2 or 8 copies of the TR have more copies of the TR per molecule than their parents, providing them with a replicative advantage. We could test this notion with plasmids having MREs. Larger, recombined species of plasmids containing MREs, which were selected for over time, proved to be head-to-tail concatemers (Fig. 6) and thus conclusively did have increased numbers of MREs per molecule compared to their parents.

Our findings and interpretations are consistent with a previously reported finding that plasmids containing 3 and 8 copies of the TR recombine to yield larger plasmids, which are selected in an EBV-negative Burkitt's lymphoma cell line, BJAB (12), suggesting that this phenomenon cannot be attributed to the particular cell lines or the plasmid backbones used but rather to the low number of TRs present in these plasmids. A similar phenomenon was also observed for EBV in some cell lines. EBV OriP deletion mutants containing 6 or few EBNA1-binding sites in the FR region support establishment with low efficiencies, and the established plasmids are maintained as rearranged plasmids containing head-to-tail multimers of the initial plasmids (32). The presence of at least 7 copies of EBNA1-binding sites in the FR, however, completely rescues the plasmids from their inability to be established by supporting efficient partitioning (32–34).

Our observations with TR/FR hybrid plasmids indicate that the instability and defect in establishment shown by plasmids with low numbers of TRs reflect their inability to support efficient partitioning. The addition of FR in cis, along with EBNA1 in trans, increased the ability of 2 TRs to support establishment and also limited the instability of plasmids containing both 2 and 8 TRs, rescuing them from their defective phenotype (Fig. 7). This finding suggests that the level of synthesis with two copies of the TR is sufficient for structurally stable maintenance despite more than 2 TRs supporting an increased level of synthesis. These observations also provide key evidence in support of the model in which a sufficiently long multimer of LBS 1/2 in the TRs functions as a cis-partitioning element of KSHV, analogous to a multimer of EBNA1-binding sites in the FR of EBV. A recent study has shown that the efficient synthesis of EBV also requires tethering of EBV genomes to chromosomal DNAs through FR (53). Hence, it is possible that the addition of FR to 2- and 8-TR plasmids indirectly increases their efficiencies of synthesis by tethering these plasmids more efficiently to chromosomal DNAs. This possibility warrants further testing.

Approximately 16 copies of the TR seems to be sufficient for KSHV-based plasmids to be established and maintained efficiently and stably. However, that KSHV genomes can have up to 50 copies of the TRs (36–38) indicates that the number of TRs per KSHV genome is modulated by factors in addition to establishment and maintenance. One such factor could be headful packaging of the viral DNA during lytic replication. EBV packages its DNA as a function of the length of DNA that allows efficient packaging. The length of DNA that is generated by the cleavage of lytically replicated concatemeric DNA at EBV's TR is optimized for its packaging (54–56). Lytic replication of KSHV is in many ways similar to that of EBV. It is possible that the wide range of TRs per KSHV genome results from a similar need to package an optimal length of DNA. This explanation is strengthened by findings that the clonality of KSHV genomes with respect to the number of TRs varies with the level of lytic reactivation supported by the host cells. For instance, in cells from MCD that exhibit a high level of lytic reactivation, KSHV genomes are polyclonal with respect to the number of TRs, while in cells from KS or PEL that exhibit a lower level of lytic reactivation, KSHV genomes are monoclonal or oligoclonal with respect to the number of TRs (57, 58). We favor a model in which a dual selection imposed by stable maintenance and headful packaging is responsible for the range in the number of TRs per KSHV genome.

Interestingly, our findings indicate that the ability of KSHV-derived replicons to support maintenance also depends on the cell type. Of the three cell lines we have used, BCBL-1 cells support establishment of introduced 16-TR plasmids with approximately 5% the efficiency in SLK and JSC-1 cells (Fig. 1). The level of LANA1 is not likely to be the reason for these differences as we found no significant differences in its level in the three cell lines (data not shown). The levels of chromatin binding proteins MeCP2 and DEK have been shown to affect the localization of LANA1 to cellular chromosomes, thereby affecting the maintenance function of LANA1 (28). Genomes of herpesvirus saimiri (HVS), a close relative of KSHV, are established inefficiently in low-MeCP2-expressing NIH 3T3 cells, but this inefficiency is rescued upon ectopic expression of MeCP2 (59). Based on these reports, it is plausible that the differential abilities of cell types to support the maintenance of KSHV are due to their differential levels of MeCP2, DEK, or yet to be identified factors.

We also provide evidence that repeats of the 71-bp MRE unit within the TR are sufficient for the establishment of KSHV genomes. As with the plasmids containing intact TRs, plasmids with increasing numbers of tandem repeats of the MRE supported increasing efficiencies of establishment (Fig. 4). Plasmids containing MREs were often present in recipient cells after establishment as integrants or as large molecules, most of which were composed of head-to-tail concatemers (Fig. 5 and 6) with an increased number of MREs per plasmid relative to the input plasmid. Similar results were obtained for MRE plasmids that express LANA1 in cis (data not shown), indicating that the instability—that is, the propensity of the plasmids containing MREs and 2 or 8 copies of TRs to be recombined and selected—is not limited to those occasions in which LANA1 is expressed in trans.

Although the MRE was sufficient for establishment, plasmids containing tandem repeats of the MRE behaved differently than those containing repeats of the TR. First, the efficiency of synthesis of MRE plasmids did not depend on the number of MREs per plasmid (Fig. 4). Second, plasmids with 16 copies of the MRE, unlike those with 16 copies of the TR, were also unstable, with recombination producing larger species that were selected for over time (Fig. 5A). Third, the MRE plasmids weren't completely rescued by the addition of FR in cis (Fig. 7). MRE/FR hybrid plasmids were established more efficiently than the MRE plasmids, but unlike TR/FR hybrid plasmids, they did recombine to yield larger species that were selected after establishment. These observations indicate that in addition to being defective for partitioning, plasmids containing tandem repeats of MREs are also defective in synthesis.

We found that the defect in synthesis shown by the MRE plasmids can be attributed to the absence of 801-bp center-to-center spacing between each unit of the MRE. Plasmids with a non-KSHV spacer sequence between 2 units of MRE behaved similarly to plasmids with 2 copies of the TR in that their inefficient establishment and instability were both rescued by the addition of FR in cis (Fig. 8). Thus, the actual sequence in the TR outside the MRE region does not play a detectable role in the synthesis of KSHV genomes, while an 801-bp center-to-center spacing between each MRE does.

The spacing between each MRE could be important for the preservation of the chromatin architecture of the TR. EBNA1- and LANA1-dependent replication of EBV- and KSHV-derived plasmids, respectively, is affected by nucleosome positioning and remodeling at the vicinity of their replication origins. For yeast autonomous replicating sequences (ARS), nucleosomes are excluded from sites in the ARS bound by its replicators (60). Forcing the assembly of ARS into a nucleosome by deleting sequences flanking the ARS reduces its ability to initiate replication (60, 61), highlighting the importance of both the native structure and the chromatin organization of the origin. The TR of KSHV is also organized into nucleosomes that are excluded from the LBS1/2 region in the context of an intact TR (20). Hence, it is plausible that the 801-bp center-to-center spacing between 2 units of MREs is required for proper chromatin structure and nucleosome positioning in the TR, which in turn might be required for efficient synthesis through the TRs. Additionally, the process of establishment is thought to include, as yet unknown, epigenetic changes in cis to the introduced plasmids (16, 35). It is possible that the plasmids containing MRE repeats without proper spacing between them fail to undergo epigenetic stabilization during establishment and thus support long-term synthesis less efficiently than intact TRs after establishment.

Our findings support a model wherein approximately 16 copies of the TRs is essential for efficient partitioning and stable maintenance of KSHV genomes, while at least 2 copies of the MRE units separated by an 801-bp center-to-center spacing are required for efficient synthesis of the KSHV genomes over the long term. Additionally, our study has revealed that KSHV-derived plasmids with inefficient maintenance elements recombine in a variety of host cells and that the larger, recombined molecules often selectively persist in the cells. Cells derived from KSHV-associated tumors occasionally harbor recombined KSHV genomes (6, 37, 62, 63). Based on our findings, the persistence of these recombined endogenous KSHV genomes indicates that they likely have a selective advantage in terms of their genome maintenance in the host cells harboring them.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Kenneth M. Kaye for kindly providing plasmids Z6-2TR and Z6-BE and Norman Drinkwater and members of the Sugden laboratory for helpful comments and critical readings of the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (grants P01 CA022443, R01 CA133027, and R01 CA070723). Bill Sugden is an American Cancer Society Research Professor.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 14 May 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Cesarman E, Moore PS, Rao PH, Inghirami G, Knowles DM, Chang Y. 1995. In vitro establishment and characterization of two acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related lymphoma cell lines (BC-1 and BC-2) containing Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like (KSHV) DNA sequences. Blood 86:2708–2714 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cesarman E, Chang Y, Moore PS, Said JW, Knowles DM. 1995. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-related body-cavity-based lymphomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 332:1186–1191. 10.1056/NEJM199505043321802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soulier J, Grollet L, Oksenhendler E, Cacoub P, Cazals-Hatem D, Babinet P, d'Agay MF, Clauvel JP, Raphael M, Degos L. 1995. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in multicentric Castleman's disease. Blood 86:1276–1280 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang Y, Cesarman E, Pessin MS, Lee F, Culpepper J, Knowles DM, Moore PS. 1994. Identification of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-associated Kaposi's sarcoma. Science 266:1865–1869. 10.1126/science.7997879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhong W, Wang H, Herndier B, Ganem D. 1996. Restricted expression of Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) genes in Kaposi sarcoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:6641–6646. 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Renne R, Lagunoff M, Zhong W, Ganem D. 1996. The size and conformation of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) DNA in infected cells and virions. J. Virol. 70:8151–8154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dictor M, Rambech E, Way D, Witte M, Bendsöe N. 1996. Human herpesvirus 8 (Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus) DNA in Kaposi's sarcoma lesions, AIDS Kaposi's sarcoma cell lines, endothelial Kaposi's sarcoma simulators, and the skin of immunosuppressed patients. Am. J. Pathol. 148:2009–2016 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kennedy G, Komano J, Sugden B. 2003. Epstein-Barr virus provides a survival factor to Burkitt's lymphomas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:14269–14274. 10.1073/pnas.2336099100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mack AA, Sugden B. 2008. EBV is necessary for proliferation of dually infected primary effusion lymphoma cells. Cancer Res. 68:6963–6968. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vereide D, Sugden B. 2009. Proof for EBV's sustaining role in Burkitt's lymphomas. Semin. Cancer Biol. 19:389–393. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2009.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nishimura K, Ueda K, Sakakibara S, Ishikawa K, Chen J, Okuno T, Yamanishi K. 2001. Functional analysis of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus RTA in an RTA-depressed cell line. J. Hum. Virol. 4:296–305 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ballestas ME, Kaye KM. 2001. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency-associated nuclear antigen 1 mediates episome persistence through cis-acting terminal repeat (TR) sequence and specifically binds TR DNA. J. Virol. 75:3250–3258. 10.1128/JVI.75.7.3250-3258.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lim C, Seo T, Jung J, Choe J. 2004. Identification of a virus trans-acting regulatory element on the latent DNA replication of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J. Gen. Virol. 85:843–855. 10.1099/vir.0.19510-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ye FC, Zhou FC, Yoo SM, Xie JP, Browning PJ, Gao SJ. 2004. Disruption of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latent nuclear antigen leads to abortive episome persistence. J. Virol. 78:11121–11129. 10.1128/JVI.78.20.11121-11129.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ballestas ME, Chatis PA, Kaye KM. 1999. Efficient persistence of extrachromosomal KSHV DNA mediated by latency-associated nuclear antigen. Science 284:641–644. 10.1126/science.284.5414.641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grundhoff A, Ganem D. 2003. The latency-associated nuclear antigen of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus permits replication of terminal repeat-containing plasmids. J. Virol. 77:2779–2783. 10.1128/JVI.77.4.2779-2783.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu J, Renne R. 2005. Characterization of the minimal replicator of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latent origin. J. Virol. 79:2637–2642. 10.1128/JVI.79.4.2637-2642.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu J, Garber AC, Renne R. 2002. The latency-associated nuclear antigen of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus supports latent DNA replication in dividing cells. J. Virol. 76:11677–11687. 10.1128/JVI.76.22.11677-11687.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lim C, Sohn H, Lee D, Gwack Y, Choe J. 2002. Functional dissection of latency-associated nuclear antigen 1 of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus involved in latent DNA replication and transcription of terminal repeats of the viral genome. J. Virol. 76:10320–10331. 10.1128/JVI.76.20.10320-10331.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stedman W, Deng Z, Lu F, Lieberman PM. 2004. ORC, MCM, and histone hyperacetylation at the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latent replication origin. J. Virol. 78:12566–12575. 10.1128/JVI.78.22.12566-12575.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verma SC, Choudhuri T, Kaul R, Robertson ES. 2006. Latency-associated nuclear antigen (LANA) of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus interacts with origin recognition complexes at the LANA binding sequence within the terminal repeats. J. Virol. 80:2243–2256. 10.1128/JVI.80.5.2243-2256.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verma SC, Choudhuri T, Robertson ES. 2007. The minimal replicator element of the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus terminal repeat supports replication in a semiconservative and cell-cycle-dependent manner. J. Virol. 81:3402–3413. 10.1128/JVI.01607-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Piolot T, Tramier M, Coppey M, Nicolas JC, Marechal V. 2001. Close but distinct regions of human herpesvirus 8 latency-associated nuclear antigen 1 are responsible for nuclear targeting and binding to human mitotic chromosomes. J. Virol. 75:3948–3959. 10.1128/JVI.75.8.3948-3959.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shinohara H, Fukushi M, Higuchi M, Oie M, Hoshi O, Ushiki T, Hayashi J, Fujii M. 2002. Chromosome binding site of latency-associated nuclear antigen of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus is essential for persistent episome maintenance and is functionally replaced by histone H1. J. Virol. 76:12917–12924. 10.1128/JVI.76.24.12917-12924.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barbera AJ, Chodaparambil JV, Kelley-Clarke B, Luger K, Kaye KM. 2006. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus LANA hitches a ride on the chromosome. Cell Cycle 5:1048–1052. 10.4161/cc.5.10.2768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barbera AJ, Chodaparambil JV, Kelley-Clarke B, Joukov V, Walter JC, Luger K, Kaye KM. 2006. The nucleosomal surface as a docking station for Kaposi's sarcoma herpesvirus LANA. Science 311:856–861. 10.1126/science.1120541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsumura S, Persson LM, Wong L, Wilson AC. 2010. The latency-associated nuclear antigen interacts with MeCP2 and nucleosomes through separate domains. J. Virol. 84:2318–2330. 10.1128/JVI.01097-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krithivas A, Fujimuro M, Weidner M, Young DB, Hayward SD. 2002. Protein interactions targeting the latency-associated nuclear antigen of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus to cell chromosomes. J. Virol. 76:11596–11604. 10.1128/JVI.76.22.11596-11604.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lagunoff M, Bechtel J, Venetsanakos E, Roy AM, Abbey N, Herndier B, McMahon M, Ganem D. 2002. De novo infection and serial transmission of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus in cultured endothelial cells. J. Virol. 76:2440–2448. 10.1128/jvi.76.5.2440-2448.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grundhoff A, Ganem D. 2004. Inefficient establishment of KSHV latency suggests an additional role for continued lytic replication in Kaposi sarcoma pathogenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 113:124–136. 10.1172/JCI17803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang CY, Sugden B. 2008. Identifying a property of origins of DNA synthesis required to support plasmids stably in human cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:9639–9644. 10.1073/pnas.0801378105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chittenden T, Lupton S, Levine AJ. 1989. Functional limits of oriP, the Epstein-Barr virus plasmid origin of replication. J. Virol. 63:3016–3025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wysokenski DA, Yates JL. 1989. Multiple EBNA1-binding sites are required to form an EBNA1-dependent enhancer and to activate a minimal replicative origin within oriP of Epstein-Barr virus. J. Virol. 63:2657–2666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hebner C, Lasanen J, Battle S, Aiyar A. 2003. The spacing between adjacent binding sites in the family of repeats affects the functions of Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen 1 in transcription activation and stable plasmid maintenance. Virology 311:263–274. 10.1016/S0042-6822(03)00122-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leight ER, Sugden B. 2001. Establishment of an oriP replicon is dependent upon an infrequent, epigenetic event. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:4149–4161. 10.1128/MCB.21.13.4149-4161.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duprez R, Lacoste V, Brière J, Couppié P, Frances C, Sainte-Marie D, Kassa-Kelembho E, Lando MJ, Essame Oyono JL, Nkegoum B, Hbid O, Mahé A, Lebbé C, Tortevoye P, Huerre M, Gessain A. 2007. Evidence for a multiclonal origin of multicentric advanced lesions of Kaposi sarcoma. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 99:1086–1094. 10.1093/jnci/djm045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Russo JJ, Bohenzky RA, Chien MC, Chen J, Yan M, Maddalena D, Parry JP, Peruzzi D, Edelman IS, Chang Y, Moore PS. 1996. Nucleotide sequence of the Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (HHV8). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:14862–14867. 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Judde JG, Lacoste V, Brière J, Kassa-Kelembho E, Clyti E, Couppié P, Buchrieser C, Tulliez M, Morvan J, Gessain A. 2000. Monoclonality or oligoclonality of human herpesvirus 8 terminal repeat sequences in Kaposi's sarcoma and other diseases. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 92:729–736. 10.1093/jnci/92.9.729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kirchmaier AL, Sugden B. 1998. Rep*: a viral element that can partially replace the origin of plasmid DNA synthesis of Epstein-Barr virus. J. Virol. 72:4657–4666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang J, Lindner SE, Leight ER, Sugden B. 2006. Essential elements of a licensed, mammalian plasmid origin of DNA synthesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26:1124–1134. 10.1128/MCB.26.3.1124-1134.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prince JT, McGrath KP, DiGirolamo CM, Kaplan DL. 1995. Construction, cloning, and expression of synthetic genes encoding spider dragline silk. Biochemistry 34:10879–10885. 10.1021/bi00034a022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nanbo A, Sugden A, Sugden B. 2007. The coupling of synthesis and partitioning of EBV's plasmid replicon is revealed in live cells. EMBO J. 26:4252–4262. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stürzl M, Gaus D, Dirks WG, Ganem D, Jochmann R. 2013. Kaposi's sarcoma-derived cell line SLK is not of endothelial origin, but is a contaminant from a known renal carcinoma cell line. Int. J. Cancer 132:1954–1958. 10.1002/ijc.27849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hirt B. 1967. Selective extraction of polyoma DNA from infected mouse cell cultures. J. Mol. Biol. 26:365–369. 10.1016/0022-2836(67)90307-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gardella T, Medveczky P, Sairenji T, Mulder C. 1984. Detection of circular and linear herpesvirus DNA molecules in mammalian cells by gel electrophoresis. J. Virol. 50:248–254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Delecluse HJ, Hammerschmidt W. 1993. Status of Marek's disease virus in established lymphoma cell lines: herpesvirus integration is common. J. Virol. 67:82–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Calos MP, Lebkowski JS, Botchan MR. 1983. High mutation frequency in DNA transfected into mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 80:3015–3019. 10.1073/pnas.80.10.3015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]