Abstract

The structural consequences of calcium depletion of Photosystem II (PS II) by treatment at pH 3.0 in the presence of citrate has been determined by Mn K-edge X-ray absorption spectroscopy. X-ray absorption edge spectroscopy of Ca-depleted samples in the S1′, S2′, and S3′ oxidation states reveals that there is Mn oxidation on the S1′–S2′ transition, although no evidence of Mn oxidation was found for the S2′–S3′ transition. This result is in keeping with the results from EPR studies where it has been found that the species oxidized to give the S3′ broad radical signal found in Ca-depleted PS II is tyrosine Yz. The S2′ state can be prepared by two methods: illumination followed by dark adaptation and illumination in the presence of DCMU to limit to one turnover. Illumination followed by dark adaptation was found to yield a lower Mn K-edge inflection-point energy than illumination with DCMU, indicating vulnerability to reduction of the Mn complex, even over the relatively short times used for dark adaptation (~15 min). EXAFS measurements of Ca-depleted samples in the three modified S states (referred to here as S′ states) reveals that the Fourier peak due to scatterers at ~3.3 Å from Mn is strongly diminished, consistent with our previous assignment of a Ca-scattering contribution at this distance. Even after Ca depletion, there is still significant amplitude in the third peak, further supporting our conclusions from earlier studies that the third peak in native samples is comprised of both Mn and Ca scattering. The Mn–Mn contributions making up the second Fourier peak at ~2.7 Å are largely undisturbed by Ca-depletion, but there is some evidence that S1′-state samples contain significant amounts of reduced Mn(II), which is then photooxidized in the preparation of higher S′ states.

Introduction

Photosystem II (PS II) is a membrane-bound protein complex found in green plants and cyanobacteria which couples single-electron photooxidations of chlorophyll to the multielectron oxidation of water to form dioxygen (for reviews, see refs 1–3). The site of water oxidation in PS II is thought to be a protein-bound tetranuclear Mn complex, which is driven by four single-electron oxidations through five intermediate states labeled S0–S4. S4 is a transient state which spontaneously decays back to S0 with the release of dioxygen. A redox-active tyrosine residue (Yz) functions as an electron-transfer component between the Mn complex and the photooxidized chlorophyll: first being oxidized by the chlorophyll of the PS II reaction center P680, then in turn oxidizing the Mn complex. Yz has been shown to be close to the Mn complex through pulsed EPR studies4 and may function to abstract protons from water or hydroxide bound to Mn.4,5 In addition to Mn, Ca and Cl ions are required cofactors for oxygen-evolving activity (for reviews, see refs 1,6,7).

PS II preparations can be depleted of calcium via two methods (low pH/citrate or NaCl wash), which result in inhibition of oxygen-evolution activity (for a discussion of Ca-depletion treatments, see ref 6). Activity can be restored by addition of Ca2+ or, to a lesser extent, by addition of Sr2+ or vanadyl ion. The exact characteristics of Ca-depleted preparations (extent of inhibition of oxygen evolution and which S-state transition is blocked) have been the subject of much debate, largely owing to different protocols followed by different groups.6 The view which appears to have gained wide acceptance is that Ca-depleted samples are blocked at a formal S3 state (i.e., Ca-depleted samples can undergo two turnovers from an S1-equivalent state).

Photooxidized forms of Ca-depleted PS II preparations have yielded interesting EPR signals which are distinct from those present in native PS II samples.

The relevance of the S-state label in these inhibited preparations is questionable. Illumination of the samples does advance the donor side of PS II through several oxidation steps, but the preparations do not evolve oxygen and thus do not form an S-state cycle. The S-state notation is useful, however, in specifying the oxidation level of the preparation. In the work presented here, the modified S states in these inhibited PS II samples will be referred to as S1′, S2′, and S3′ states to distinguish them from the S states in native samples.

In samples which have been depleted of calcium in the presence of a chelating agent (citrate, EGTA, EDTA), altered stability of the S2 state is observed. In these samples, the S2′ state can be formed by illumination at 273 K with DCMU present to limit the samples to one turnover or they can be dark-adapted at 273 K after illumination without DCMU. The S2′ state is stable for long periods of time (hours) at room temperature, and an EPR multiline signal is observed, which has a smaller average line spacing of ~55 G vs 88 G in untreated PS II.8,9 Formation of the stable multiline signal has been shown to be dependent on the presence of chelators during the Ca-depletion treatment,10,11 although the line shape and stability of the S2′ state multiline signal does not exhibit variations depending on chelator (citrate, EGTA, EDTA). In the absence of chelators, a normal multiline signal can be observed.

Illumination of Ca-depleted samples at 277 K, with no restriction on the number of turnovers, results in the formation of a broad EPR signal centered at g = 2.8,9 This signal is ~160 G wide in the absence of the extrinsic polypeptides and 130 G with the extrinsic polypeptides bound. A width of <90 G is observed in PS II preparations from Synechocystis 6803 which have been washed with a Ca-free medium containing EDTA.12 Similar signals have also been observed in a number of differently inhibited preparations. The exact width of the signal differs depending on the type of treatment used; the largest widths (~230 G) are found in acetate-treated PS II,13 while smaller splittings (<160 G) are found in F−-treated,14 NH3-treated,15,16 and Cl−-depleted samples.17 These signals have been assigned to modified S3 states in these inhibited preparations.

The identity of the oxidized species giving rise to the S3′ signal has been a subject of great interest. Initially it was proposed to be an organic radical, broadened by a magnetic interaction with the Mn complex.8 On the basis of comparisons of optical difference spectra, this organic radical was proposed to be histidine.18 This assignment was challenged by Hallahan et al.16 who suggested that the radical was YZ, the redox-active tyrosine between the OEC and P680 in the electron-transfer chain in PS II. This proposal was rebutted by Boussac and Ruther-ford19 who contended that the results were distorted by saturation effects, and more recent FTIR results have also been interpreted as favoring the assignment to histidine.20 The most direct evidence has been obtained by pulsed ENDOR spectroscopy on low-pH/citrate-treated PS II and by ESEEM studies on acetate-treated cyanobacterial PS II isotopically labeled at tyrosine, which show that the S3′ EPR signal arises from oxidized YZ.4,21

The significance of the S3′ EPR signal has been questioned in a study using pulsed EPR, where it was concluded that the S3′ signal may arise from less than 25% of centers and that the majority of centers in the S3′ state are EPR silent.4,22 Zimmermann et al.,23 however, report in another pulsed EPR study that the S3′ signal arises from a majority of centers. Further, Zimmermann et al.23 report that the modified multiline signal does not disappear in the S3′ state but is instead broadened beyond detection by conventional EPR while the amplitude remains detectable by pulsed EPR. More recent pulsed EPR quantitation of the two signals supports the view that they are present in the majority of centers.24 A further confirmation of the nature and interconvertability of the signals comes from studies where NO was bound to Yz, quenching the radical signal and resulting in the appearance of an S2 multiline signal.25

The stoichiometry of Ca2+ in PS II has been a matter of some confusion, although most results seem to point to there being Ca2+/PS II reaction center: one high-affinity binding site which requires extreme conditions for removal and a second, lower-affinity site from which Ca2+ can be removed by the NaCl or low-pH treatments discussed above. (For discussions of this point, see refs 1, 6, and 7.) For the low-pH/citrate treatment, it has been specifically reported that one of the two Ca2+/PS II is removed.26

X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) has been used to examine the structural environment of metal ions in many proteins. Element specificity and applicability to noncrystalline samples have made XAS a useful technique for probing the structure of the Mn complex in the complicated environment of PS II, which has many components (non-heme iron, cytochrome, chlorophyll, etc.) that interfere with other techniques. The different regions of the X-ray spectrum provide complementary information; X-ray absorption edges yield information about the oxidation states and site symmetry of the absorbing atom, and extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) is sensitive to distances, numbers, and atomic number of atoms around the absorbing atom (for reviews of XAS in biological systems, see refs 27–29).

Mn EXAFS studies on PS II preparations (reviewed in ref 3) have indicated that the structure contains Mn–Mn distances of 2.7 Å and bonds to oxygen/nitrogen atoms of 1.8 Å, both of which are characteristic of di-μ-oxo-bridged structures. A longer distance interaction at ~3.3 Å has also been detected, but in this case, interpretations differ. Among them are (1) a single Mn–Mn distance of 3.3 Å;30,31 (2) a Mn–Mn or Mn–Ca at 3.3 Å;32 (3) Mn–Mn and Mn–Ca at ~3.3 Å;31,33 and (4) a single Mn–Ca at 3.7 Å.34 Using Sr-substituted samples, we have found that the best description of the data includes both Mn and Ca interactions at 3.3–3.5 Å.35,36 Recent work employing Sr-EXAFS on similar samples supports the assignment of a Ca contribution to the ~3.3 Å interaction (Cinco et al., this issue; but see also Riggs-Gelasco et al.37 and Booth et al.38).

In the work presented here, the question of the state of the Mn cluster in the modified S states exhibited in Ca-depleted PS II is addressed. XAS edge spectra were obtained for S1′-, S2′-, and S3′-state samples. The results indicate that there is no evidence for Mn oxidation on the S2′ to S3′ transition, which is consistent with the view that a tyrosine Yz is oxidized in this step. EXAFS results indicate that the di-μ-oxo-bridged moieties remain relatively unchanged through all the S′ states but the ~3.3 Å interactions are perturbed. The lower amplitude of the 3.3 Å peak in Ca-depleted PS II supports our earlier results that the peak at 3.3 Å contains both Mn and Ca scattering. Several XAS studies have been reported on Ca-depleted preparations.39–43 The relation of the previous XAS studies to the present work will be discussed.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of Ca2+-Depleted PS II Samples

Triton X-100-extracted PS II particles were prepared from market spinach according to the procedure of Berthold et al.44 and either used immediately for Ca-depletion treatments or frozen (−20 °C) for later use as pellets in a buffer containing 0.4 M sucrose, 25 mM MES, pH 6.5, and 15 mM NaCl. All procedures were carried out at 4 °C.

Depletion of calcium from PS II particles was acheived using the low-pH/citrate procedure of Ono and Inoue26 as described in refs 35 and 36. All steps were performed in the dark or with very dim green light. A 2 mg of Chl/mL solution of PS II particles in a 0.4 M sucrose, 20 mM citrate, pH 3.0, 15 mM NaCl buffer was incubated in the dark for 5 min and then brought to pH 6.5 with buffer A (0.4 M sucrose, 50 mM MES, pH 6.5, 15 mM NaCl, 100 mM EGTA). The preparation was then pelleted by centrifugation (15 min at 40 000 g) and resuspended again in buffer A. At this point, some samples had DCMU (0.5 mM) added from a stock solution in DMSO.

The treated PS II particles were then centrifuged (20 min at 40 000g), and the resulting pellets were transferred to Lucite sample holders, backed by Mylar tape, designed to fit into both the EPR and X-ray cryostats. Samples which were to remain in the dark-adapted S1 state were made by filling the Lucite cavity completely. Samples which were to be illuminated were spread in a thin layer (<0.5 mm) on the Mylar backing. Following placement in sample holders, samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen. All samples were stored and transported in liquid nitrogen.

All glassware and utensils were acid washed, and all buffers were treated with Chelex-100 (Bio-Rad) to remove any Ca contamination.

Oxygen Evolution Measurements

Oxygen evolution activity was measured under continuous illumination using a Clark-type oxygen evolution electrode as described by DeRose.45 2,6-DCBQ (2 mM) was used as an electron acceptor in all assays. The oxygen evolution activity of untreated PS II particles was 500–600 μmol of O2/mg of Chl/h. Oxygen evolution of Ca-depleted preparations was measured in buffer A (see above). Oxygen evolution activity was inhibited in Ca-depleted PS II to 10–15% of the value measured in untreated preparations. Addition of Ca2+ (50 mM CaCl2) reactivated the activity to 80–85% of that in untreated preparations. Chlorophyll assays were performed on acetone extracts.46

EPR Spectroscopy

All samples were characterized by low-temperature EPR using a Varian E-109 EPR spectrometer with an Air Products Helitran liquid helium cryostat. Spectra were collected before and after exposure to X-rays to ensure that no damage (released Mn(II)) had occurred from X-ray exposure or in sample handling. Ca-reactivated samples were poised in the S2 state by illumination for 10 min at 195 K with a 400 W tungsten lamp. A 5 cm aqueous CuSO4 filter (5%, w/v) was used for thermal isolation. The S2′ state was formed in Ca-depleted samples by two methods: illumination for 2 min at 0 °C, followed by incubation in the dark for 15–20 min at 0 °C (S2′-annealed), or illumination of a DCMU-containing sample for 2 min at 0 °C and then immediately freezing in liquid nitrogen (S2′-DCMU).

X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy

Mn X-ray absorption edge spectra were collected at Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (SSRL) on beamlines 4-2, 4-3, and 7-3. EXAFS spectra were collected on beamline X-9A at the National Synchrotron Light Source, Brookhaven National Laboratory, and at SSRL on beamlines 7-3 and 4-2. All spectra were collected using Si(220) double-crystal monochromators and recorded as fluorescence excitation spectra47 using a 13-element solid-state Ge detector.48 Energy calibration49 and measurement of incident flux was carried out as described by Guiles et al.50

The sample temperature was maintained at 10–12 K using an Oxford Instruments CF 1208 liquid helium flow cryostat with exchange gas (He) in the sample space to ensure good thermal control. Many cryostats used in XAS experiments employ a coldfinger in a vacuum and rely completely on thermal contact between the sample and the metal coldfinger to maintain low measurement temperatures. Good thermal contact can be difficult to achieve with biological samples in plastic sample holders, such as those employed here, and may result in a sample temperature which is significantly higher than the temperature of the cold head. Also, if the sample temperature rises high enough and the sample is kept in a vacuum, lyophilization of the samples can occur, which has been reported to set back the S-state cycle in native samples.51 We have encountered problems with PS II sample degradation (photoreduction of Mn) in cryostats which do not employ an exchange gas.

XAS Data Analysis

Data reduction for EXAFS and edge spectra were performed as reported previously.45,50 Second derivatives of Mn K-edge spectra, which accentuate the shape of the edges, were derived by analytical differentiation of a third-order polynomial fit over a ±2.5 eV range around each point.

All EXAFS spectra were converted from energy (eV) to photoelectron wave vector (k-space, Å−1) using the equation

| (1) |

where h is Planck’s constant, me is the mass of the electron, E is the X-ray energy, and E0 is the ionization threshold, which was chosen as 6563.0 eV for all spectra (a point near the peak of the Mn K-edge). All spectra were weighted by k3, and Fourier transforms were calculated from k-space spectra truncated to zero crossings in the data to minimize truncation distortions (~3.6–11.2 Å−1).

For analysis of the data presented here, Fourier peaks were isolated individually and in pairs to help simplify the spectra and to minimize the effects of distortions due to Fourier isolation.52 Ranges of the Fourier transforms were isolated for analysis by application of a Hamming window function (applied to the first and last 15% of the range, the middle 70% left unmodified) to the transform.

Curve fitting was done using ab initio calculated phase and amplitude information from the program FEFF 5 (version 5.05)53 as described previously.35,36

The following equation was used in curve-fitting the EXAFS data

| (2) |

where for each shell i, Ni is the number of scatterers at distance Ri, S02 is a many-body amplitude reduction factor, Bi(k) is an amplitude reduction factor caused by inelastic losses in the central atom, feff(π, k, Ri) is the effective backscattering amplitude of the scattering atom, δci(k) and ϕi(k) are phase shifts for the absorber and backscatterer respectively, σι2 is a Debye–Waller term, and λ(k) is the mean-free-path of the photoelectron. Coordination numbers (Ni) are calculated on a per Mn basis and are interpreted here in the context of a total of four Mn atoms/PS II.

The quality of the fits presented here was evaluated as described previously.35,36

Results

EPR Spectroscopy

Ca-depleted PS II preparations can be generated by two protocols. Samples which have been created by treatment with a high NaCl concentration (1.2 M NaCl treatment in the light and in the presence of chelators) are initially in the S2′ state owing to the illumination during the protocol and the enhanced stability of the S2′ state in the presence of chelators, although it has also been reported that a high degree of inhibition can be achieved by exposure to a high salt concentration and chelators in darkness.41 Low-pH-treated preparations (pH 3.0 treatment in the dark with citrate) remain in the S1′ state and must be advanced to S2′ or S3′ by illumination. The low-pH treatment was chosen for the experiments reported here because all three Ca-depleted S states were readily accessible in these preparations.

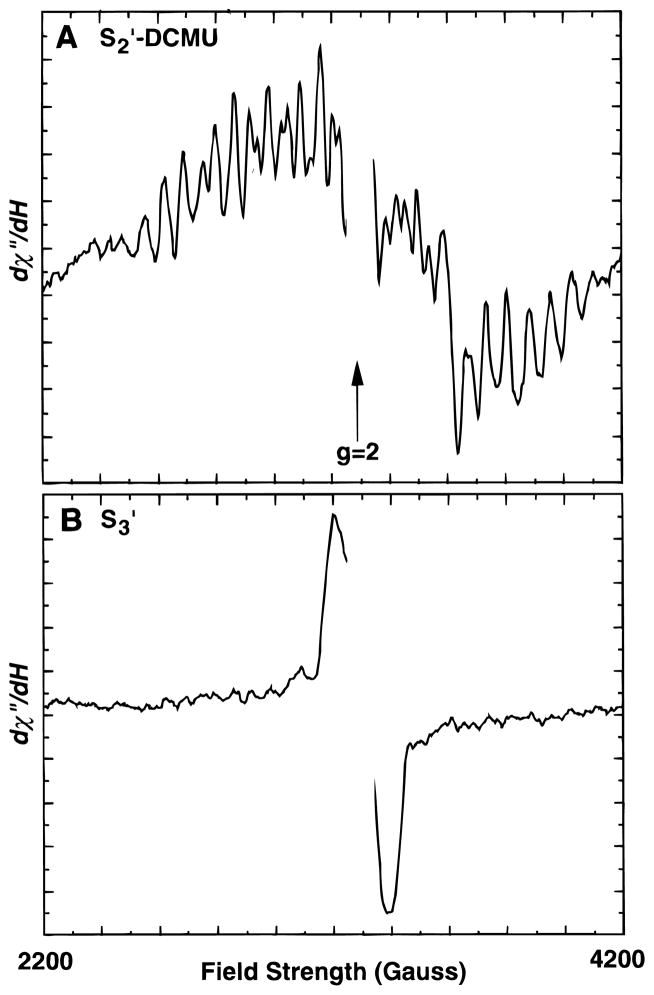

EPR spectra from Ca-depleted samples in the S2′ and S3′ states are shown in Figure 1. The sample used for the S2′-state spectrum contained the herbicide DCMU, which displaces the QB quinone and prevents electron transfer beyond QA. The QA−-signal appears as a sharp downward feature at ~3700 G. The S2′ state can be generated in low-pH/citrate-treated PS II either by illumination at 273 K, where the samples are limited to one turnover (with DCMU), or by dark adaptation of a sample illuminated at 273 K, where photoaccumulation of the S3′ (or higher) state occurs.9 The results from the DCMU-treated sample demonstrate that the state giving rise to the modified multiline signal arises from a single turnover and thus must arise from a formal S2 state (denoted S2′ here). The multiline signals observed in each case are identical except for the underlying signal from QA− in the sample containing DCMU. Illumination at 190 K resulted in no measurable multiline signal formation, which is characteristic for low-pH/citrate-treated preparations54 and is another indication of the completeness of Ca depletion.

Figure 1.

EPR Spectra from Ca-depleted samples in the S2′ (A) and S3′-states (B). The S2′-state sample was a Ca-depleted sample with DCMU added. The S3′-state sample had no DCMU added. Both were advanced from the S1′ state by illumination at 273 K. The multiline spectrum in panel A is displayed on an expanded vertical scale (×4.3) to allow comparison with the higher amplitude S3′-state signal in panel B. Spectrometer conditions: microwave frequency, 9.2 GHz; microwave power, 20 mW; modulation amplitude, 20 G; temperature, 8 K.

In the absence of DCMU, illumination of low-pH/citrate-treated samples at 273 K results in a broad (~160 G peak-to-peak) derivative-shaped signal centered at g = 2 (Figure 1B). The appearance of this signal coincides with the loss of the S2′ multiline signal and has been shown by others18 using single-turnover flashes to result from a state that is one-step oxidized from the S2′ state; a formal S3 state (S3′). The S3′ state is relatively unstable and deactivates quickly to the S2′ state (half-life of 300 ms in the presence of reduced QA18) and can be difficult to trap quantitatively. Initially, samples for XAS experiments were made in the usual manner, where the sample was spread in a thick paste into a Lucite sample holder (thickness ≈ 1.5 mm), but these samples were difficult to saturate during illumination and displayed significant amounts of S2′-state multiline signal in addition to the S3′ signal. It was found that spreading a thin layer (<0.5 mm) onto the Mylar backing of the XAS sample holder resulted in more complete advancement to the S3′ state. Although complete advancement was never achieved, the amplitude of the S2′-state multiline signal could be reduced to a low level.

Reasonable estimates of the S-state composition of these samples were achieved as described. S3′ populations were calculated based on the residual level of the S2′ multiline signal compared to 100% S2′ in S2′-DCMU and S2′-annealed samples. Relative amplitudes of the S3′ EPR signals were also used to cross-check and ensure that the calculated populations were consistent with the observed amplitudes of all signals. S3′-state samples used for X-ray edge experiments ranged from 55% to > 80% S3′, while S3′-state EXAFS samples were all >75% S3′. In practice, however, we find that annealed samples are vulnerable to reduction during the dark incubation and the S2′-DCMU samples must be quickly frozen or the S2′ state will recombine with the negative charge trapped on QA. The S-state compositions reported here, thus, represent conservative estimates; the actual values for S3′ and S2′ percentages may be higher.

X-ray Edge Spectroscopy

Mn K-edge spectra are relatively broad, and structural features on the edges are quite subtle. The edge spectra in this paper are also presented as second derivatives, which accentuate the shape of the edge and allow clear comparisons of edge structure. The region in the spectrum from 6545 to 6555 eV corresponds to the rising part of the edge and has been shown to be sensitive to the oxidation state of the absorbing atom.33 Increased oxidation states create a higher positive charge on a metal ion. A higher energy photon is required to extract an electron from a more positively charged atom, resulting in an edge shift to higher energy. Edge energies can also be affected by ligands (by the degree of electron donation) and by the symmetry around the atom, which can affect the selection rules and relative energy levels of transitions. The inflection-point energy can be determined as the zero crossing of the second derivative, which in the spectra presented here appears at ~6551–6553 eV. The region above ~6555 eV is more sensitive to the ligand environment33 and is affected by the start of the EXAFS scattering. The relatively low energy of the photoelectron also means that multiple scattering interactions can dominate in this region, and the interpretation of the spectra can be quite difficult.

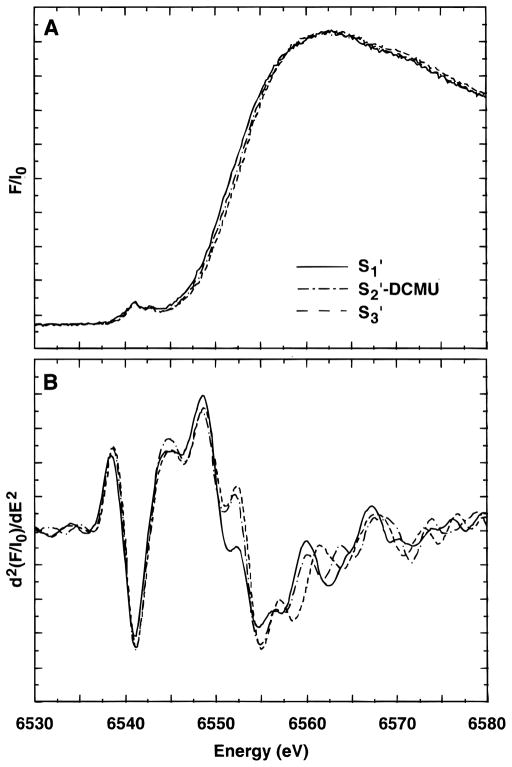

X-ray edge absorption and corresponding second-derivative spectra of samples in predominantly the S1′, S2′, and S3′ states are presented in Figure 2. The spectra are presented of the samples as measured, i.e., there has been no subtraction to attempt to extract “pure” S-state spectra. The S2′-state sample was generated by illumination of a sample containing DCMU (S2′-DCMU). The inflection-point energies (IPE) are reported in Table 1. The IPE for the S1′-state sample (6550.7 eV) is lower than that found in native S1-state samples (6551.7 eV55,56) and indicates that either there has been a reduction of the complex caused by the Ca-depletion procedure or a significant structural change has occurred. This lower edge energy has also been observed by Ono et al.39 where it was shown that the edge could be restored to the native S1-state energy by reconstitution with Ca in the absence of illumination.

Figure 2.

Mn X-ray K-edge spectra (A) and second derivatives (B) from Ca-depleted samples in the S1′, S2′, and S3′ states. The S2′-state sample was prepared by illumination after addition of DCMU.

TABLE 1.

Inflection-Point Energies (IPE) of Ca-Depleted Samples in the S1′, S2′, and S3′ Statesa

| IPE (eV) | |

|---|---|

| S1′ state | 6550.7 (0.2)b |

| S2′ state (DCMU) | 6552.8 (0.4)b |

| S3′ state | 6553.2 (0.3)b |

| S2′ state (annealed) | 6550.1 (0.3)b |

Values are averages over 3–5 samples.

Standard deviations are given in parentheses.

The S2′-DCMU and S3′-state samples have quite similar spectra in the region of the inflection point, with only a small shift in IPE (0.4 eV) between them. The IPE of the S2′- and S3′-state samples (6552.8 and 6553.2 eV, respectively) approach that of the native S2 state (6553.5 eV55,56) and constitute a large shift (2.1–2.5 eV) from the spectrum of the S1′-state sample. As stated above, the S2′- and S3′-state samples are not pure in their S′-state composition. The estimate of the actual S3′-state content of the S3′ samples ranges from 55% to >80%. There was, however, no systematic trend to higher energies for samples with higher S3′ content: the edge energy seems relatively insensitive to the relative amounts of S2′ or S3′ and the scatter of edge energies was relatively small (standard deviation of 0.2 eV). On the basis of the S3′ spectra, there appears to be no discernible difference in the edge energy between samples in the S2′ and S3′ state.

The S2′-DCMU samples were slightly lower in energy (0.4 eV) than the S3′-state samples, but the S2′-DCMU samples are a mixture of pure S1′ and S2′ states, which could account for the lower edge energy.

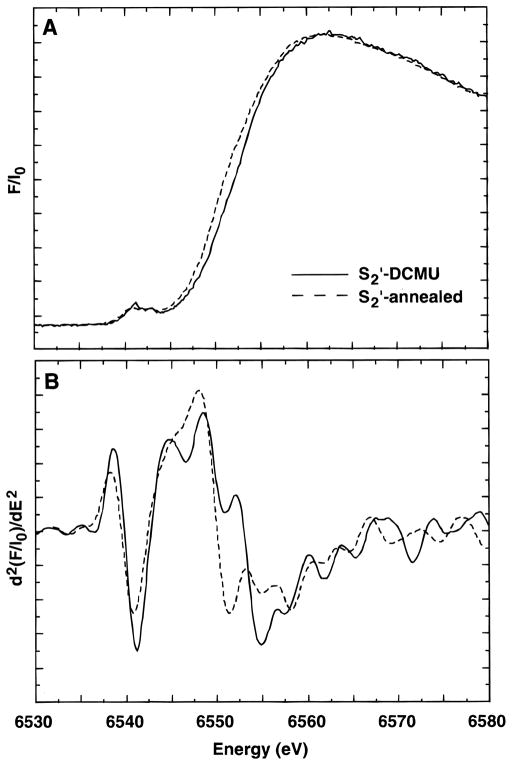

Data were also collected on S2′-state samples made by dark adaptation of S3′-state samples (S2′-annealed) as described above. The Mn K-edge spectra from S2′-DCMU and S2′-annealed samples are compared in Figure 3. Surprisingly, the edge in the S2′-annealed sample is actually at lower energy (6550.1 eV) than the S2′-DCMU sample. In fact, it is lower in energy than the S1′-state samples (see Table 1). The lower edge energy clearly indicates that there is some change occurring in these samples during the dark adaptation period which results in a significant lowering of the edge energy, but we observed no major loss of the multiline signal compared to S2′-DCMU samples. The Mn cluster has been shown to be more vulnerable to exogenous reductants in the absence of Ca,7,57,58 and we find that delays during the treatment process inevitably lead to samples in which the Mn cluster has been partially destroyed, releasing Mn(II) ions which can be often detected as a six-line signal centered at g = 2 in the EPR spectrum. However, our EPR spectra from the S2′-annealed samples do not show a Mn(II) EPR signal, although a small signal would be difficult to observe in the presence of the S2′-state multiline.

Figure 3.

Mn X-ray K-edge spectra (A) and second derivatives (B) from samples in the S2′ state prepared by annealing (S2′-annealed) and by illumination with turnovers limited by DCMU (S2′-DCMU).

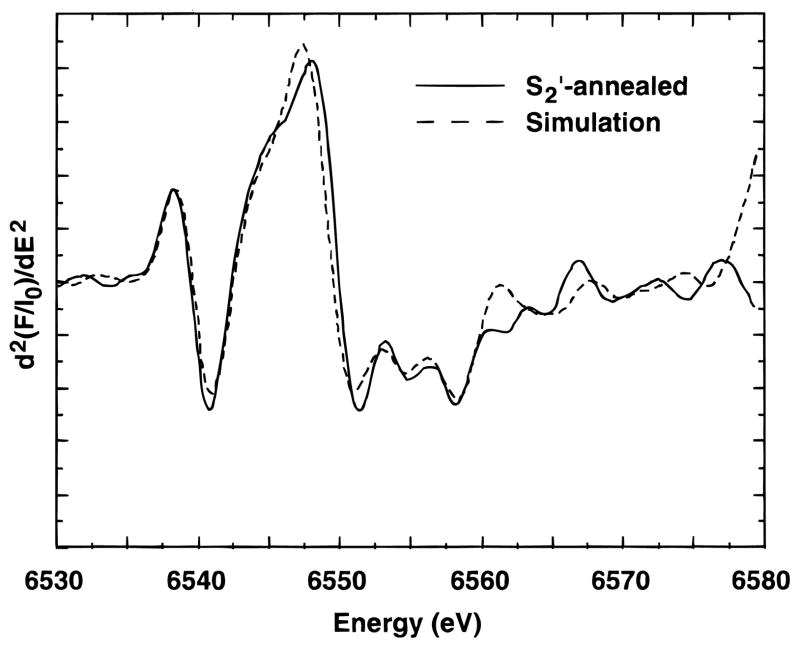

To test the possibility that Mn(II) release by damaged centers is the cause of the lowered edge, we attempted to simulate the edge of the S2′-annealed samples by adding various amounts of Mn(II) hexaquo edge spectra to the spectrum from an S3′- state sample. This technique has been shown to be reasonably accurate for the determination of Mn(II).32,59 The shape of the edge of the S2′-annealed sample in the region of the inflection point was, however, not well-simulated using the hexaquo Mn(II) spectrum.

To a certain extent, general edge shapes can be simulated by addition of spectra from monomeric Mn(II), Mn(III), and Mn(IV) complexes, and this technique has been used to determine the probable oxidation state composition of native PS II samples in the S1 and S2 states.33 However, the inflection-point regions of mixed-valence Mn(II)Mn(III) compounds are not exactly simulated by the addition of spectra from monomeric complexes, probably owing to the effects of the structural environment, including the proximity of the Mn ions to each other.

To test the possibility that the lower edge energy in the S2′- annealed sample was caused by partial reduction of the Mn cluster during the annealing process, but without release of the reduced Mn from the cluster, simulations were attempted where varying amounts of spectra from mixed-valence Mn(II)Mn(III) complexes were added to the spectrum from an S3′ sample. Both a Mn3(II, III2) trimer, (Mn3O(O2CPh)6(py)2(H2O),60 and a Mn4(II, III3) tetramer, (Mn4O2(benz)7(bipy)2,61 were tried and gave similar results. The best simulation (using the trimer) is presented in Figure 4. In this case, the simulation was created with 35% of the trimer spectrum and 65% S3′-state spectrum. This would correspond to approximately 12% Mn(II) in the sample. The results from the simulation with the tetramer indicated ~8% Mn(II). These simulations should not be taken as a quantitative determination but rather as an indication that the lower edge energy may be caused by a slow reduction of the Mn complex without release of Mn during the annealing process.

Figure 4.

Simulation of the second derivative Mn X-ray K-edge spectrum from a Ca-depleted sample in the S2′ state formed by dark adaptation of an S3′-state sample. The simulated spectrum (- - -) is the sum of the spectrum from a Mn3(II, III2) trinuclear model complex (35%) and a spectrum from a sample in the S3′ state (65%).

Mn EXAFS of Ca-Depleted Preparations

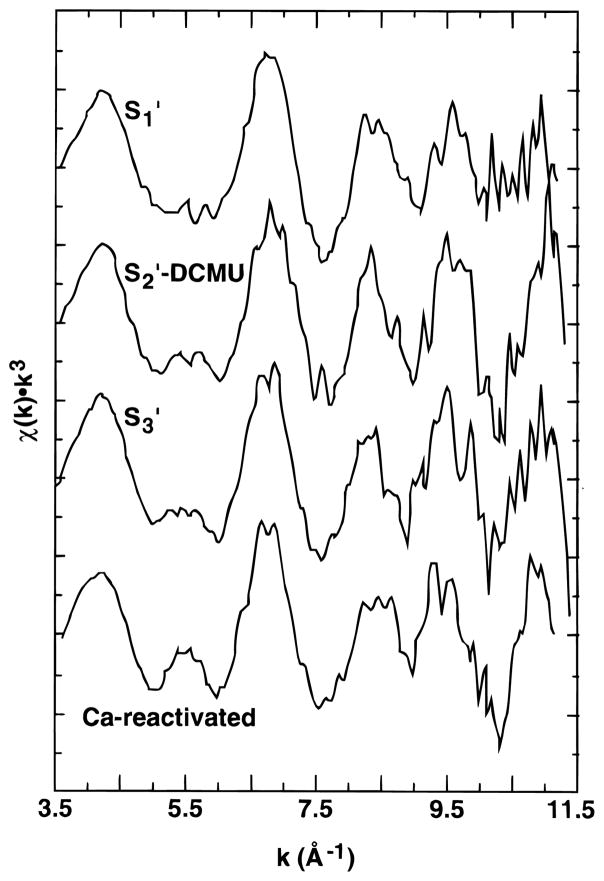

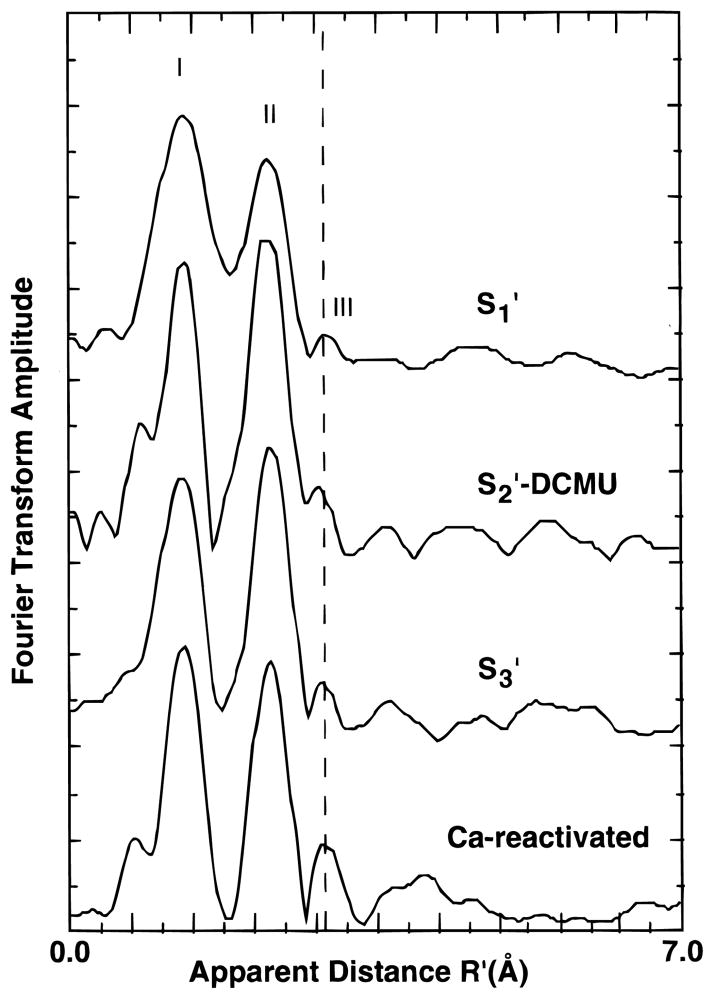

The Mn K-edge EXAFS of Ca-depleted samples in the S1′, S2′, and S3′ states are presented in Figure 5 along with the spectrum of a Ca-depleted sample after reactivation with Ca. Fourier transforms of the EXAFS are presented in Figure 6.

Figure 5.

k3-weighted EXAFS spectra of Ca-depleted PS II samples in the S1′, S2′, and S3′ states. The EXAFS from a Ca-reactivated sample is shown for comparison.

Figure 6.

Fourier transforms of k3-weighted EXAFS from Ca-depleted PS II samples in the S1′, S2′, and S3′ states. The Fourier transform from a Ca-reactivated sample is shown for comparison.

The greatest difference is found between Ca-reactivated PS II in the S1 state and Ca-depleted PS II in the S1′ state. The EXAFS of the S1′-state samples has a lower amplitude (especially at k > 9 Å−1), and in the Fourier transforms, the peaks appear broader and lower in amplitude. Another obvious difference is the substantial decrease in amplitude of the third Fourier peak, which we have previously assigned to Mn–Ca and Mn–Mn interactions. The effects observed on the EXAFS are similar to the effects observed previously on the EXAFS of isostructural model complexes with and without Mn(II).62 Given the reduction of Mn observed in S2′-annealed samples, it is perhaps not surprising that there may be some reduced Mn found in the S1′-state samples which have seen no illumination from the start of the Ca-depletion treatment.

Samples subjected to illumination (S2′-DCMU and S3′), by contrast, have well-resolved Fourier peaks and are more similar to Ca-reactivated or native samples except for the reduced amplitude of the third Fourier peak.

Results of fits to the first two Fourier peaks are presented in Table 2. For each sample, two shells were fit to the data; a short distance 1.8–1.9 Å O scatterer and a longer distance ~2.7 Å Mn–Mn interaction. In each case it was found, on the whole, that the short distance Mn–O interaction was at a slightly longer distance and more disordered in the S1′-state samples than in the S2′- or S3′-state samples. Addition of more scattering shells did not yield better fits for the S1′-state samples, the most appropriate adjustment being a higher Debye–Waller factor rather than another well-defined distance. Fits to the S2′- and S3′-state samples were overall similar to Ca-reactivated PS II in the S1 state.

TABLE 2.

Two-Shell Simulations of Fourier Peaks I and IIa

| sampleb | Mn–O interaction

|

σ 21c | Mn–Mn interaction

|

σ 22c | ΔE0 | Φ × 103 d | ε2 × 105 d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1(Å) | N1 | R2(Å) | N2 | ||||||

| CDS1A | 1.85 | 3.67 | 0.0096 | 2.71 | 1.04 | 0.0040 | −17 | 0.81 | 1.57 |

| CDS1B | 1.85 | 4.34 | 0.0101 | 2.72 | 0.91 | 0.0020 | −18 | 0.68 | 1.35 |

| CDS2 | 1.82 | 2.30 | 0.0060 | 2.70 | 1.09 | 0.0020 | −21 | 0.60 | 1.16 |

| CDS3A | 1.83 | 3.71 | 0.0100 | 2.71 | 0.92 | 0.0016 | −21 | 0.41 | 0.79 |

| CDS3B | 1.83 | 2.49 | 0.0080 | 2.71 | 0.91 | 0.0030 | −20 | 0.70 | 1.38 |

| CDS3C | 1.87 | 2.57 | 0.0080 | 2.75 | 0.89 | 0.0030 | −12 | 0.85 | 1.69 |

Fit parameters are as defined in the text. S02 = 0.85 in all fits. Data were fit k = 3.7–11.2 Å−1. The width of the Fourier isolation window employed was 2 Å.

CDS1A and CDS1B are S1′-state samples; CDS2 is an S2′-state sample; CDS3A, B, C are S3′-state samples.

Units are Å2.

Goodness-of-fit parameters Φ and ε2 are defined in refs 35 and 36. Φ is the fit error function normalized to the amplitude of the EXAFS oscillations. ε2 is Φ with the number of floating parameters taken into account. N1 and N2 correspond to the average number of O and Mn scatterers at distances R1 and R2 around an absorbing Mn atom.

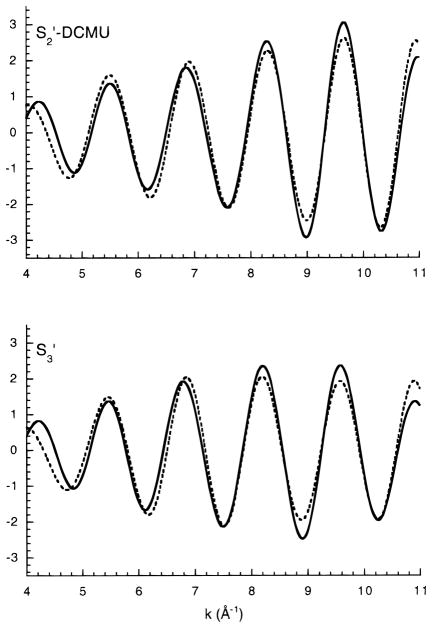

Results of fits to Fourier peaks II and III are presented in Table 3; Fourier isolates and fit curves are presented in Figure 7. No fits are presented for S1′-state samples because the third Fourier peak was so small and the second peak could not be reliably separated from the first Fourier peak. Fits including all three Fourier peaks for the S1′-state samples were completely insensitive to the contribution of the third Fourier peak. The S2′- and S3′-state EXAFS were, again, similar to those reported for Ca-sufficient samples with respect to the 2.7 Å Mn–Mn interactions but displayed a reduced amplitude for the interaction at ~3.3 Å. Fits were also tried for a carbon shell at ~3.5 Å, but the distance had a tendency to drop to ~2.5 Å if allowed to vary. This is a problem with fitting such a small contribution in the presence of a strong Fourier peak. Unfortunately, the third Fourier peak cannot be realistically fit alone due to the proximity to the strong 2.7 Å Mn–Mn peak and the fact that the limited R range limits the number of allowable fit parameters to fewer than necessary to determine the variables of one shell.

TABLE 3.

Two-Shell Simulations of Fourier Peaks II and IIIa

| sampleb | Mn–Mn Interaction

|

σ 21c | Mn–Mn Interaction

|

σ 22c | ΔE0 | Φ × 103 d | ε2 × 105 d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1(Å) | N1 | R2(Å) | N2 | ||||||

| CDS2 | 2.73 | 1.11 | 0.0020 | 3.32 | 0.28 | 0.0040 | −13 | 0.42 | 1.44 |

| CDS3A | 2.73 | 0.99 | 0.0020 | 3.23 | 0.15 | 0.0040 | −15 | 0.52 | 1.66 |

| CDS3B | 2.75 | 0.77 | 0.0020 | 3.28 | 0.18 | 0.0040 | −12 | 0.36 | 1.18 |

| CDS3C | 2.75 | 0.81 | 0.0020 | 3.30 | 0.20 | 0.0040 | −12 | 0.49 | 1.61 |

Fit parameters are as defined in the text. S02 = 0.85 in all fits. Data were fit k = 3.7–11.2 Å−1. The width of the Fourier isolation window employed was 1.5 Å.

CDS2 is an S2′-state sample; CDS3A, B, C are S3′-state samples.

Units are Å2.

Goodness-of-fit parameters Φ and ε2 are defined in refs 35 and 36. Φ is the fit error function normalized to the amplitude of the EXAFS oscillations. ε2 is Φ with the number of floating parameters taken into account. N1 and N2 correspond to the average number of Mn scatterers at distances R1 and R2 around an absorbing Mn atom.

Figure 7.

Fits to Fourier isolates of peaks II and III in S2′-DCMU and S3′-state samples. Data are presented as solid lines, fits as dashed lines. These curves correspond to fit results for samples CDS2 and CDS3A in Table 3.

In the fits in Table 3, the Debye–Waller factors were fixed at reasonable values based on fits to Ca-reactivated PS II. The spread of values for Debye–Waller factors was quite large when they were allowed to vary, which is probably another indication of the susceptibility to noise level of a contribution at this low amplitude. It is significant, however, that the fits are improved by the addition of a Mn–Mn scattering shell at 3.3 Å. Although the coordination numbers of the fits are somewhat low for a Mn–Mn interaction at this fixed Debye–Waller value, the interaction is clearly present and may represent a more disordered Mn–Mn interaction than is accounted for in the fit. The most reasonable conclusion based on these data is that Ca depletion removes a Mn–Ca contribution from the third Fourier peak but a disordered Mn–Mn contribution remains present.

Discussion

The Mn X-ray K-edge data presented here on the modified S states in Ca-depleted samples indicate that there is a large edge shift on the S1′–S2′ transition but little or no significant change in the edge position/inflection point for the S2′–S3′ transition. As discussed above, edge positions are determined by the oxidation state and ligand/structural environment. In the absence of large structural changes, an edge shift can be ascribed to changes in the oxidation state of the absorbing atom. Assuming that no major structural changes occur in the S-state transitions the results indicate that there is Mn oxidation on the S1′–S2′ transition, but not on the S2′–S3′ transition. This result is in agreement with the recent pulsed EPR observations of Boussac24 and with the effects of NO quenching on the S3′-state EPR signal.25

Ono and co-workers40 have also performed XAS experiments on Ca-depleted PS II using the low-pH/citrate treatment employed here. These samples were advanced through the S′ states by single laser flashes. They did not perform EPR on the samples used for XAS but compared the pattern of increasing edge energy on successive flashes with EPR results obtained by other groups on similar laser-flash-prepared samples. On the basis of these comparisons, they have proposed that there is a Mn oxidation-state change on both the S1′–S2′ and S2′–S3′ transitions. The total S1′–S3′ edge shift reported by Ono et al. (1.9 eV) is comparable to the shift observed in the spectra presented here for the S1′–S2′ transition (2.1 eV), where the composition of the samples was confirmed by EPR. It seems probable that the differences between our results and those of Ono et al. are due to incomplete advancement of the Ca-depleted samples by the laser flashes in their study.

In another study, MacLachlan et al.41 report edge spectra from Ca-depleted as well as ammonia- and acetate-inhibited preparations which also exhibit a form of the S3′ EPR signal. EPR spectroscopy was performed on parallel samples but not on XAS samples, and a simultaneous energy reference was not used. This group has subsequently repeated the experiment with a simultaneous energy reference and report results which are much more similar to what is reported here, although they do report a small shift of 0.4 eV on the S2′ to S3′ transition.43 In the work we have presented here, our S2′-DCMU samples were also found to be ~0.4 eV lower than S3′-state samples, but careful examination of the EPR signal amplitudes and edge positions has led us to the conclusion that considering the mix of states present in the prepared samples, there is no descernible shift in edge position between the S2′ to S3′ states. We find that samples are difficult to prepare in the S2′ state owing to incomplete advancement in DCMU-treated samples and the vulnerability to reduction of samples prepared by dark adaptation. MacLachlan et al.41 and Turconi et al.43 poised samples in the S2′ state by dark adaptation for a short period of time (5–10 min). It is possible that the relatively shorter dark adaptation time used by MacLachlan et al. and Turconi et al. (5–10 vs 15–20 min here) resulted in a smaller shift to lower energy for their S2′-state samples.

Our observation of an edge shift to lower energy in S2′-state samples prepared by illumination followed by dark adaptation has important implications for other groups working with Ca-depleted preparations. We have shown that the lower edge energy is probably due to the presence of Mn(II) formed by reduction of the complex during dark adaptation and that this reduction is not readily discernible in the EPR spectra of these samples. Our results show clearly that S2′-state samples prepared by the two methods are not equivalent and, further, that neither method should be assumed to yield 100% S2′.

EXAFS of S1′-State Samples

The EXAFS of the S1′-state samples is markedly different from the spectra observed in Ca-reactivated or native PS II samples. The decreased amplitude of the Fourier peaks may be indicative of a small percentage of reduced centers which can be photooxidized. Mn(II)-containing clusters exhibit significantly different bond lengths relative to higher-valent Mn clusters, and mixtures of the two can result in the “washed out” EXAFS amplitudes that we observe here relative to Ca-reactivated PS II. A second feature is the very small amplitude of the third Fourier peak in these samples. This could also be partially due to the effect of reduced centers, but third-peak amplitudes are affected in all the modified S states relative to Ca-reactivated PS II.

EXAFS of S2′ and S3′ State Samples

The differences between the S2′- and S3′-state samples and Ca-reactivated PS II are more subtle and are most apparent in the decreased amplitude of the third Fourier peak. The reduced amplitude of the third peak is consistent with a Ca contribution at this distance, as discussed in our previous work.35,36 The remaining third peak is difficult to fit unambiguously but is consistent with the presence of a disordered Mn–Mn interaction at 3.3 Å. The reduction of peak amplitude relative to Ca-reactivated or native PS II cannot be accounted for by the presence of residual Ca, because our activity measurements show that more than 80% of the centers are inhibited, i.e., are depleted of Ca. One possible contributing factor to the increased disorder in the third-peak Mn–Mn interaction could be the presence of a chelator (citrate), which is thought to bind to the Mn cluster in Ca-depleted chelator-treated preparations.

The retention of the two ~2.7 Å units in a relatively undisturbed state indicates that the Mn complex remains otherwise largely intact. This is perhaps not surprising given that activity can be restored quite readily by supplying Ca ions. The di-μ-oxo ~2.7 Å Mn–Mn units appear to be quite hardy in the face of a great number of inhibitory treatments, at most changing the Mn–Mn distance slightly in one of the pairs.

In another XAS study of Ca-depleted preparations, MacLachlan et al.42 found that the 2.7 Å Mn–Mn interactions were split into two contributions (they observed a shoulder Fourier peak II) and a small decrease in amplitude of the third Fourier peak. The split second Fourier peak was observed in all three S′ states in their study. One possible difference between their work and the experiments reported here is the technique of Ca depletion: NaCl treatment for them vs low-pH/citrate treatment. We see absolutely no evidence of such a split second peak in the spectra from our samples.

One important question remaining is whether what is learned from the Ca-depleted preparations is relevant to the native system. Recent Mn K-edge results from the Klein/Sauer group indicate that in native samples there is also very little edge shift on the S2–S3 transition.55,56 This result has been interpreted as indicating that there is no Mn oxidation in this transition. There are possible parallels between native and Ca-depleted samples in that perhaps an organic radical is also formed in the native S3 state which interacts with the Mn cluster, rendering both the multiline and radical signals unobservable by conventional EPR. Recent EXAFS results on native samples in the S3 state indicate that there is a strong perturbation of the ~2.7 Å Mn–Mn di-μ-oxo units.63 This result raises the possibility that in the native samples, in contrast to what we observe with Ca-depleted samples, the lack of an edge shift on the S2–S3 transition could be a consequence of the onset of water oxidation chemistry and structural rearrangements which do not occur in the inhibited samples.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Director, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Division of Energy Biosciences of the U.S. Department of Energy, under Contract No. DE-AC03-76SF00098, and by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (GM55302 to V.K.Y.). We thank Dr. Britton Chance for the use of his Ge detector. We are also grateful to Dr. B. Hedman and Dr. S. Khalid for assistance at the beamlines. We thank Dr. Joy Andrews, Roehl Cinco, Dr. Holger Dau, Dr. Melissa Grush, Dr. Wenchuan Liang, Dr. Ishita Mukerji, and Dr. Theo Roelofs for help with data collection. We also thank Dr. Jean-Luc Zimmermann for helpful discussions and for assistance with data collection. Synchrotron radiation facilities were provided by the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory and the National Synchrotron Light Source, both supported by DOE. The Biotechnology Laboratory at SSRL and Beam Line X9-A at NSLS are supported by the National Center for Research Resources of the National Institutes of Health.

References and Notes

- 1.Debus RJ. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1102:269–352. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(92)90133-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Britt RD. In: Oxygenic Photosynthesis: The Light Reactions. Ort DR, Yocum CF, editors. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Dordrecht: 1996. pp. 137–164. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yachandra VK, Sauer K, Klein MP. Chem Rev. 1996;96:2927–2950. doi: 10.1021/cr950052k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilchrist ML, Ball JA, Randall DW, Britt RD. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9545–9549. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoganson CW, Babcock GT. Science. 1997;277:1953–1956. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5334.1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rutherford AW, Zimmermann J-L, Boussac A. In: The Photosystems: Structure, Function, and Molecular Biology. Barber J, editor. Elsevier B. V; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 1992. pp. 179–229. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yocum CF. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1059:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boussac A, Zimmermann JL, Rutherford AW. Biochemistry. 1989;28:8984–8989. doi: 10.1021/bi00449a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sivaraja M, Tso J, Dismukes GC. Biochemistry. 1989;28:9459–9464. doi: 10.1021/bi00450a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boussac A, Zimmermann JL, Rutherford AW. FEBS Lett. 1990;277:69–74. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80811-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ono TA, Inoue Y. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1020:269–277. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirilovsky DL, Boussac AGP, van Mieghem FJE, Ducruet JMRC, Sétif PR, Yu J, Vermass WFJ, Rutherford AW. Biochemistry. 1992;31:2099–2107. doi: 10.1021/bi00122a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacLachlan DJ, Nugent JHA. Biochemistry. 1993;32:9772–9780. doi: 10.1021/bi00088a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baumgarten M, Philo JS, Dismukes GC. Biochemistry. 1990;29:10814–10822. doi: 10.1021/bi00500a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andréasson LE, Lindberg K. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1100:177–183. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hallahan BJ, Nugent JHA, Warden JT, Evans MCW. Biochemistry. 1992;31:4562–4573. doi: 10.1021/bi00134a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boussac A, Rutherford AW. J Biol Chem. 1994;267:12462–12467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boussac A, Zimmermann JL, Rutherford AW, Lavergne J. Nature. 1990;347:303–306. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boussac A, Rutherford AW. Biochemistry. 1992;31:7441–7445. doi: 10.1021/bi00148a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berthomieu C, Boussac A. Biochemistry. 1995;34:1541–1548. doi: 10.1021/bi00005a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang XS, Randall DW, Force DA, Diner BA, Britt RD. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:7638–7639. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilchrist ML, Lorigan GA, Britt RD. In: Research in Photosynthesis. Murata N, editor. II. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Dordrecht, The Netherlands: 1992. pp. 317–320. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zimmermann JL, Boussac A, Rutherford AW. Biochemistry. 1993;32:4831–4841. doi: 10.1021/bi00069a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boussac A. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1277:253–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szalai VA, Brudvig GW. Biochemistry. 1996;35:15080–15087. doi: 10.1021/bi961117w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ono TA, Inoue Y. FEBS Lett. 1988;227:147–152. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scott RA. Methods Enzymol. 1985;117:414–459. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(85)17026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cramer SP. In: X-ray Absorption: Principles, Applications, and Techniques of EXAFS, SEXAFS, and XANES. Koningsberger DC, Prins R, editors. Wiley-Interscience; New York: 1988. pp. 257–320. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yachandra VK. Methods Enzymol. 1995;246:638–675. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)46028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.George GN, Prince RC, Cramer SP. Science. 1989;243:789–791. doi: 10.1126/science.2916124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DeRose VJ. PhD Dissertation. University of California; Berkeley, CA: 1990. Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory Report No. LBL-30077. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Penner-Hahn JE, Fronko RM, Pecoraro VL, Yocum CF, Betts SD, Bowlby NR. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:2549–2557. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yachandra VK, DeRose VJ, Latimer MJ, Mukerji I, Sauer K, Klein MP. Science. 1993;260:675–679. doi: 10.1126/science.8480177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.MacLachlan DJ, Hallahan BJ, Ruffle SV, Nugent JHA, Evans MCW, Strange RW, Hasnain SS. Biochem J. 1992;285:569–576. doi: 10.1042/bj2850569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Latimer MJ, DeRose VJ, Mukerji I, Yachandra VK, Sauer K, Klein MP. Biochemistry. 1995;34:10898–10909. doi: 10.1021/bi00034a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Latimer MJ. PhD Dissertation. University of California; Berkeley, CA: 1994. Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory Report No. LBL-37897. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Riggs-Gelasco PJ, Mei R, Ghanotakis DF, Yocum CF, Penner-Hahn JE. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:2400–2410. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Booth PJ, Rutherford AW, Boussac A. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1277:127–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ono TA, Kusunoki M, Matsushita T, Oyonagi H, Inoue Y. Biochemistry. 1991;30:6836–6841. doi: 10.1021/bi00242a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ono TA, Noguchi T, Inoue Y, Kusunoki M, Yamaguchi H, Oyonagi H. FEBS Lett. 1993;330:28–30. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80912-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.MacLachlan DJ, Nugent JHA, Evans MCW. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1185:103–111. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(94)90052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.MacLachlan DJ, Nugent JHA, Bratt PJ, Evans MCW. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1186:186–200. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Turconi S, Horwitz CP, Weintraub ST, Warden JT, Nugent JHA, Evans MCW. In: Photosynthesis: from Light to Biosphere. Mathis P, editor. Vol. 2. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Dordrecht, The Netherlands: 1995. pp. 301–304. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Berthold DA, Babcock GT, Yocum CF. FEBS Lett. 1981;134:231–234. [Google Scholar]

- 45.DeRose VJ, Mukerji I, Latimer MJ, Yachandra VK, Sauer K, Klein MP. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:5239–5249. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arnon DI. Plant Physiol. 1949;24:1–15. doi: 10.1104/pp.24.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jaklevic J, Kirby JA, Klein MP, Robertson AS, Brown G, Eisenberger P. Solid State Commun. 1977;23:679–682. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cramer SP, Tench O, Yocum M, George GN. Nuclear Instr Methods Phys Res. 1988;A266:586–591. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goodin DB, Falk K-E, Wydrzynski T, Klein MP. SSRL Report No 79/05; 6th Annual Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory Users Group Meeting; Stanford, CA: Stanford University; 1979. pp. 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guiles RD, Zimmerman JL, McDermott AE, Yachandra VK, Cole JL, Dexheimer SL, Britt RD, Wieghardt K, Bossek U, Sauer K, Klein MP. Biochemistry. 1990;29:471–485. doi: 10.1021/bi00454a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kawamoto K, Asada K. In: Current Research in Photosynthesis. Baltscheffsky M, editor. Vol. 1. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Dordrecht, The Netherlands: 1990. pp. 889–892. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang K, Stern EA, Ellis F, Sanders-Loehr J, Shiemke AK. Biochemistry. 1988;27:7470–7479. doi: 10.1021/bi00419a045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rehr JJ, Albers RC, Zabinsky SI. Phys Rev Lett. 1992;69:3397–3400. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.69.3397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ono TA, Inoue Y. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1989;275:440–448. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(89)90390-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liang W. PhD Dissertation. University of California; Berkeley, CA: 1994. Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory Report No. LBL-36632. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Roelofs TA, Liang W, Latimer MJ, Cinco RM, Rompel A, Andrews JC, Sauer K, Yachandra VK, Klein MP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3335–3340. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mei R, Yocum CF. Biochemistry. 1991;30:7836–7842. doi: 10.1021/bi00245a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tso J, Sivaraja M, Dismukes GC. Biochemistry. 1991;30:4734–4739. doi: 10.1021/bi00233a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sauer K, Yachandra VK, Britt RD, Klein MP. In: Manganese Redox Enzymes. Pecoraro VL, editor. VCH Publishers; New York: 1992. pp. 141–175. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vincent JB, Chang HR, Folting K, Huffman JC, Christou G, Hendrickson DN. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:5703–5711. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vincent JB, Christmas C, Folting K, Huffman JC, Christou G, Chang H-R, Hendrickson DN. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1987:236–238. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Guiles RD, Yachandra VK, McDermott AE, Cole JL, Dexheimer SL, Britt RD, Sauer K, Klein MP. Biochemistry. 1990;29:486–496. doi: 10.1021/bi00454a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liang W, Roelofs TA, Olsen GT, Latimer MJ, Cinco RM, Rompel A, Sauer K, Yachandra VK, Klein MP. In: Photosynthesis: from Light to Biosphere. Mathis P, editor. Vol. 2. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Dordrecht, The Netherlands: 1995. pp. 413–416. [Google Scholar]