Abstract

Objectives

Suicide is a major global health problem imposing a considerable burden on populations in terms of disability-adjusted life years. There has been an increasing trend in fatal and attempted suicide in Iran over the past few decades. The aim of the current study was to assess overall, gender and social inequalities across Iran’s provinces during 2006–2010.

Design

Ecological study.

Setting

The data on distribution of population at the provinces were obtained from the Statistical Centre of Iran. The data on the annual number of deaths caused by suicide in each province were gathered from the Iranian Forensic Medicine Organization.

Methods

Suicide mortality rate per 100 000 population was calculated. Human Development Index was used as the provinces’ social rank. Gini coefficient, rate ratio and Kunst and Mackenbach relative index of inequality were used to assess overall, gender and social inequalities, respectively. Annual percentage change was calculated using Joinpoint regression.

Results

Suicide mortality has slightly increased in Iran during 2006–2010. There was a substantial and constant overall inequality across the country over the study period. Male-to-female rate ratio was 2.34 (95% CI 1.45 to 3.79) over the same period. There were social inequalities in suicide mortality in favour of people in better-off provinces. In addition, there was an increasing trend in these social disparities over time, although it was not statistically significant.

Conclusions

We found substantial overall, gender and social disparities in the distribution of suicide mortality across the provinces in Iran. The findings showed that men in the provinces with low socioeconomic status are at higher risk of suicide mortality. Further analyses are needed to explain these disparities.

Keywords: Suicide mortality, Social inequality, Pure inequality, Temporal analysis, Iran

Strength and limitations of this study.

This is the first national study to evaluate regional social inequalities in suicide mortality over a 5-year period.

Social inequality in suicide mortality was evaluated using Cuzick’s test for trend and two common inequality measures: rate ratio and Kunst and Mackenbach relative index of inequality.

Age and gender differences between the provinces were naïvely adjusted, which might have not fully captured differences in age distribution across provinces.

Introduction

Suicide is considered as one of the three leading causes of death among the 15–44 years age group and the second cause of death in the 15–19 years age group.1 It imposes a considerable burden on populations in terms of disability-adjusted life years and it has been projected that suicide will compose about 2.4% of the global burden of diseases by 2020.2

Similar to other developing countries, Iran has been experiencing a rapid increase in suicide rates during recent years. A recent study showed that suicide and attempted suicide in Iran have increased from 8.3/100 000 population in 2001 to 16.3 in 2007.3 Moreover, suicide accounts for 4% of injury cases admitted to general hospitals in the country.4

The risk factors of suicide are some demographical characteristics,5 socioeconomic situations6 and medical conditions.7 However, there are also factors related to the area of residence that influence the suicide rate.8 Evidence demonstrates persistent geographical disparities in distribution of suicide between and within countries, which supports area-level correlates of suicide.9

Iran is a Middle Eastern country with 1 628 550 km2 land area10 and consists of 31 provinces11 that are in different levels of development. Ethnic groups tend to reside in neighbouring provinces. Therefore, there are variations in socioeconomic level and ethnicity across provinces as well as geographical and ecological differences that could cause a disparity among suicide mortality rates.

While information on the individual risk factors and outcomes of suicide attempts have been well documented in previous studies in Iran,3 4 12–15 there is little information on the role of socioeconomic factors and suicide incidence. In particular, there is no known study evaluating regional socioeconomic disparities and their impact on suicide rates in Iran.

To fill the gap, this study aimed to describe overall and social inequality in suicide mortality rates across all provinces in Iran from 2006 to 2010. Although this is an ecological study, it will provide a useful starting point for examining the social disparity of suicide and provide valuable information for policymakers in order to prioritise prevention strategies.

Methods

The data on distribution of population at the provinces were obtained from the Statistical Centre of Iran. It should be noted that at the time of conducting the current study, Iran constituted of 30 provinces; it was later that Tehran province was split into two provinces. The data on the annual number of deaths caused by suicide in each province were gathered from the published reports16 of Iranian Forensic Medicine Organization, which is affiliated to the Judicial Authority in Iran. According to Iranian law, all deaths due to external causes should be reported to this organisation for examination and recording and to issue the death certificate. It is considered as the most reliable source of mortality data in Iran.17 Next, annual suicide mortality rates per 100 000 population were calculated for each province. Human Development Index (HDI) was used as the provinces’ social rank and related data were obtained from the President Deputy of Strategic Planning and Control. The HDI is a composite index of three basic dimensions of human development, including life expectancy at birth, educational attainment (based on a combination of adult literacy rate and primary education to tertiary education enrolment rates) and income (based on gross domestic product per head adjusted for purchasing-power parity (US$))18. As a composite index, it is expected that HDI might capture socioeconomic development more comprehensively than single indicators such as average income or expenditures.

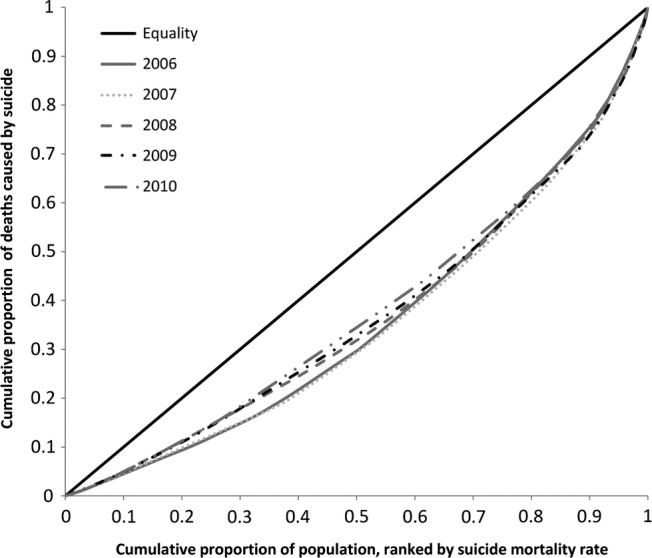

Overall inequality measures inequalities in health, irrespective of the other characteristics of the individual.19 To measure overall inequality we followed the same approach as measuring income inequality and used the Lorenz curve and Gini coefficient. These two measures are commonly used in assessing overall inequality in distribution of healthcare resources and outcomes.20–22 The Lorenz curve is used to compare the distribution of health measure with perfect equality (diagonal line). In the current study, the Lorenz curve was plotted as the cumulative share of population ranked by suicide mortality rate, in an increasing order, against the cumulative share of suicide mortality. The further the distance from the diagonal line the greater the degree of inequality. The Gini coefficient is equal to twice the area between the Lorenz curve and the diagonal line and its value ranges from 0 (perfect equality) to 1 (maximum possible inequality). This measure takes into account the distribution of health variables across the entire population. In the current study, we used fastgini command in STATA to calculate the Gini coefficient and its jackknife 95% CI. In order to examine the gendered nature of suicide mortalities (ie, gender inequality) in Iran, we calculated the male-to-female rate ratio (RR) and its 95% CI using negative binomial regression with a robust variance. As we only had data stratified by sex groups for the whole study period and not for every specific year, an overall RR was calculated.

Social inequality was evaluated using Cuzick’s test for trend and two common inequality measures: RR and Kunst and Mackenbach relative index of inequality (RIIKM).23 Cuzick’s test for trend is an extension of the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and is used as a non-parametric test for trend across ordered groups.24 To calculate RR, the provinces were ranked and divided in five quintiles by HDI (weighted by their population). Then, negative binomial regression with a robust variance was used to calculate RR and its 95% CI to compare the highest versus the lowest quintile. One problem with RR is that it only considers the population in two extreme socioeconomic groups. To take into account the whole population distribution across socioeconomic groups and also to remove differences in the size of socioeconomic groups, as a source of variation in the magnitude of health inequalities, RIIKM was calculated.23 RII is widely used to measure social inequality and is recommended when making comparisons over time or across populations.25 To calculate RII, after determining the relative position of the population in the provinces ranked by HDI, the number of deaths in the provinces was regressed on these relative ranks using negative binomial regression with a robust variance and population as offset variable. With the lowest social rank as reference, an RIIKM value greater (lesser) than 1 shows that the suicide mortality rate was higher among the provinces with higher (lower) social rank (more distance from 1 implies more inequality).21 To account for sex and age differences between the provinces, we also estimated adjusted RIIKM by including the proportion of males in the population, and the mean age of females and mean age of males in our negative binomial regression.

To examine temporal changes of suicide mortality rates across the provinces and also across the quintiles of HDI, we calculated annual percentage change (APC) and its 95% CI for each province and quintile using the Joinpoint Regression Program V.3.5.4. Moreover, this program was used to calculate APC of overall and socioeconomic inequality measures over the study period. APC is estimated using the following regression:

|

where It shows the suicide mortality rate and estimated inequality indices for year t.

In a sensitivity analysis, Tehran was excluded from the analysis to examine the overall, gender and social inequalities across the remaining provinces. The reason for this was that Tehran has special status as the capital of the country and is the centre of economic, social and political activities. Excel office and STATA V.11 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas, USA) were used for statistical analysis.

Results

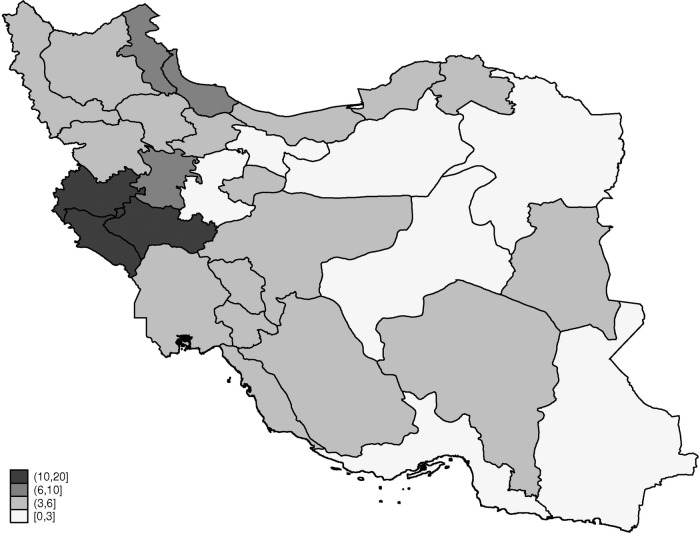

Table 1 shows mean population, HDI, suicide mortality rate and APC (%) across the provinces for years 2006–2010. Ilam and Hormozgan provinces had the highest and the lowest suicide mortality rate during the study period, respectively (8.8-fold difference). Most provinces (56.6%) had a suicide mortality rate of 3–6/100 000 population. In addition, suicide mortality rate was more prevalent among the western provinces of Iran (figure 1).

Table 1.

Mean population, Human Development Index (HDI), suicide mortality rate and annual percentage change (APC) across the provinces in Iran, 2006–2010 (ranked by suicide mortality rate)

| Population | HDI | Suicide mortality rate per 100 000 population | APC (%)* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ilam | 555 929 | 0.729 | 19.53 | 10.11 |

| Kermanshah | 1 892 100 | 0.748 | 13.74 | 0.46 |

| Lorestan | 1 736 946 | 0.761 | 10.64 | 1.18 |

| Hamedan | 1 700 960 | 0.740 | 9.59 | −1.52 |

| Gilan | 2 428 553 | 0.769 | 6.52 | 9.98 |

| Ardebil | 1 235 234 | 0.735 | 6.22 | −2.32 |

| East Azerbaijan | 3 646 459 | 0.763 | 5.58 | 1.31 |

| Zanjan | 973 739 | 0.752 | 5.53 | 12.14 |

| Kohgyluyeh and Boyerahmad | 651 577 | 0.718 | 5.25 | −4.20 |

| Khuzestan | 4 372 242 | 0.762 | 5.11 | −7.13 |

| West Azerbaijan | 2 944 224 | 0.713 | 4.72 | −2.74 |

| Kordestan | 1 453 503 | 0.713 | 4.69 | 5.25 |

| Golestan | 1 651 708 | 0.737 | 4.49 | 5.67 |

| Overall (Iran) | 72 599 045 | 0.758 | 4.46 | 3.05 |

| Qazvin | 1 177 582 | 0.783 | 4.25 | −1.13 |

| North Khorasan | 824 979 | 0.759 | 4.24 | 10.64 |

| Fars | 4 431 684 | 0.783 | 4.16 | 1.56 |

| Chaharmahal Bakhtiari | 875 207 | 0.749 | 4.00 | −7.72 |

| Qom | 1 087 011 | 0.773 | 3.75 | 7.89 |

| Mazandaran | 2 979 189 | 0.745 | 3.66 | −5.71 |

| Isfahan | 4 680 831 | 0.810 | 3.64 | 4.62 |

| Kerman | 2 799 417 | 0.750 | 3.10 | −5.03 |

| Bushehr | 914 710 | 0.786 | 3.02 | 15.55 |

| South Khorasan | 656 469 | 0.723 | 3.02 | −2.28 |

| Tehran | 14 106 297 | 0.843 | 2.92 | 17.98 |

| Yazd | 1 028 152 | 0.809 | 2.68 | −4.48 |

| Razavi Khorasan | 5 765 706 | 0.777 | 2.66 | −2.64 |

| Semnan | 606 982 | 0.814 | 2.60 | 4.27 |

| Markazi | 1 371 514 | 0.785 | 2.38 | −10.73 |

| Sistan and Baluchestan | 2 569 107 | 0.643 | 2.23 | 6.11 |

| Hormozgan | 1 481 031 | 0.766 | 2.21 | −5.59 |

*Italic figures show statistically significant results (p<0.05).

Figure 1.

Distribution of suicide mortality rates across the provinces in Iran.

The estimated APC values show that only five provinces experienced significant changes in suicide mortality rate over the study period (significant increases in Ilam, Isfahan, North Khorasan and Tehran provinces and significant decrease in Markazi province).

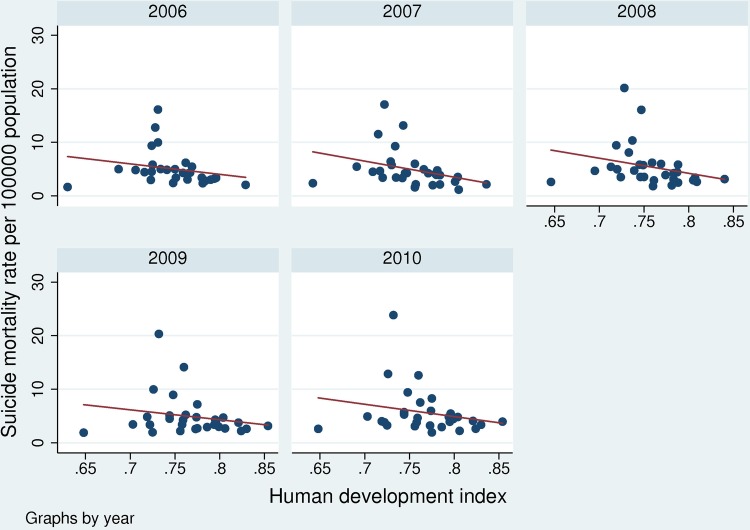

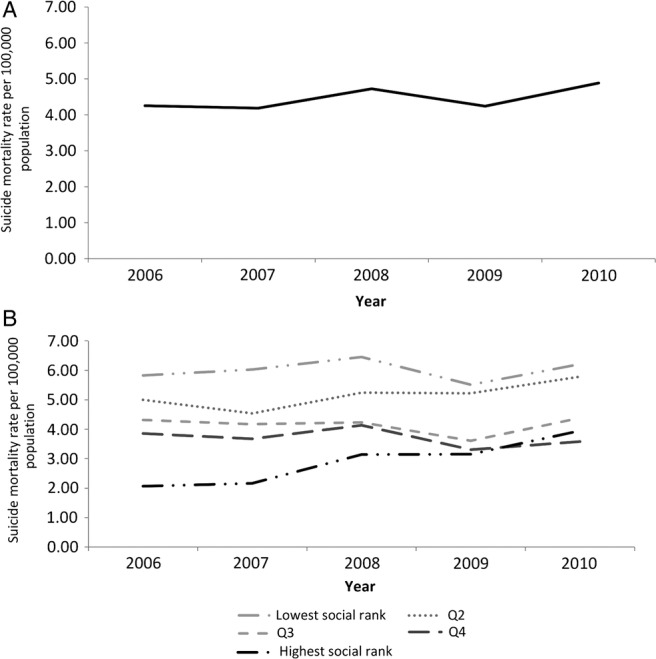

Figure 2A shows temporal changes of suicide mortality rates for the country. While the graph shows a slight increase in suicide mortality rates over the study period (from 4.25 in 2006 to 4.88 in 2010), this was not statistically significant (APC=3.05%, p=0.23). Figure 2B presents suicide mortality rates for five quintiles of HDI and examining the trends showed that APC was significant only in the highest quintile (APC=17.98, p=0.01). Figure 3 shows scatter graphs of HDI and suicide mortality rates. It is evident that the higher HDI was associated with lower suicide mortality rates and Cuzick’s test confirmed this (z=−4.61, p<0.011).

Figure 2.

Suicide mortality rates per 100 000 populations in (A) total sample; (B) quintiles (Q) of Human Development Index, 2006–2010.

Figure 3.

Scatter plots of Human Development Index and suicide mortality rates, stratified by year of study.

Male-to-female RR was 2.34 (95% CI 1.45 to 3.79), implying a significant higher suicide mortality rate among males than females over the study period. Examining this ratio in the provinces showed that in all provinces but Kordestan men had a higher suicide mortality rate than women. Excluding Tehran from the sample did not change this finding (2.33; 95% CI 1.43 to 3.79).

Table 2 presents the overall and social inequality measures in distribution of suicide mortality rates across the country through 2006–2010. The Gini coefficient ranged from 0.248 to 0.302, implying substantial overall inequality across the provinces. The Lorenz curves corresponding to this Gini coefficient is shown in figure 4. There was a 14.5% decrease in the Gini coefficient between the first year and the last year of study, implying decreasing overall inequality between these two points of time. Over the study period, the APC of the Gini coefficient was −4.28 and statistically non-significant. Excluding Tehran resulted in a 6.9% increase in the Gini coefficient between the first and the last year of the study period and a statistically non-significant APC of 1.42 was estimated.

Table 2.

Overall and social inequality measures of suicide mortality in Iran, 2006–2010

| 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | Overall | APC (p value) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample (n=30) | |||||||

| Gini index | 0.290 (0.193–0.386) | 0.302 (0.212–0.392) | 0.271 (0.182–0.361) | 0.268 (0.165–0.371) | 0.248 (0.151–0.345) | 0.281 (0.240–0.322) | −4.28 (0.050) |

| Rate ratio* | 0.359 (0.256–0.503) | 0.325 (0.225–0.469) | 0.428 (0.284–0.646) | 0.496 (0.296–0.830) | 0.535 (0.316–0.906) | 0.426 (0.275–0.659) | 12.20 (0.049) |

| RIIKM | 0.345 (0.174–0.686) | 0.257 (0.127–0.521) | 0.289 (0.142–0.588) | 0.337 (0.147–0.776) | 0.341 (0.148–0.784) | 0.339 (0.166–0.671) | 1.75 (0.745) |

| Adjusted RIIKM† | 0.279 (0.129–0.600) | 0.205 (0.098–0.431) | 0.224 (0.102–0.489) | 0.133 (0.039–0.455) | 0.160 (0.051–0.507) | 0.171 (0.054–0.548) | −13.75 (0.073) |

| Sample excluding Tehran (n=29) | |||||||

| Gini index | 0.259 (0.168–0.350) | 0.285 (0.187–0.382) | 0.282 (0.187–0.378) | 0.292 (0.192–0.392) | 0.277 (0.191–0.363) | 0.282 (0.243–0.322) | 1.42 (0.38) |

| Rate ratio* | 0.646 (0.444–0.938) | 0.397 (0.226–0.695) | 0.415 (0.247–0.696) | 0.520 (0.277–0.974) | 0.492 (0.262–0.924) | 0.584 (0.380–0.896) | −6.59 (0.403) |

| RIIKM | 0.460 (0.257–0.823) | 0.339 (0.179–0.644) | 0.352 (0.185–0.672) | 0.397 (0.187–0.839) | 0.389 (0.185–0.819) | 0.411 (0.215–0.785) | −2.76 (0.575) |

| Adjusted RIIKM† | 0.402 (0.224–0.722) | 0.301 (0.168–0.541) | 0.310 (0.165–0.580) | 0.211 (0.077–0.577) | 0.241 (0.093–0.623) | 0.241 (0.090–0.649) | −12.95 (0.045) |

*The highest versus the lowest quintile of Human Development Index.

†Adjusted for proportion of males and mean age of males and females in the provinces.

APC, annual percentage change; RIIKM, Kunst and Mackenbach relative index of inequality.

Figure 4.

Lorenz curves of the distribution of suicide mortality in Iran, 2006–2010.

RR was significantly lower than 1 in overall and for all years of the study period, implying a higher suicide mortality rate among people in the lowest quintile of HDI compared with the highest. Over the study period, RR was approaching 1 and the APC of RR was 12.2 and statistically significant, implying a decrease in the gap between the highest and the lowest social ranks. Although excluding Tehran from the sample did not change the overall picture of social inequality, an inverse trend (increasing social inequality) was observed.

RIIKM was also lower than 1 in overall and for all years of the study, showing a persistent inequality in favour of people living in the provinces with higher social rank. Temporal analysis showed that RIIKM did not significantly change over the study period. Adjusting for age and sex did not change this observation. When we excluded Tehran province, the APC value for adjusted RIIKM was statistically significant, showing an increase in social disparity across the remaining provinces in Iran.

Discussion

In this study, for the first time, we assessed overall and social disparities in the distribution of suicide mortality across the provinces of Iran over a period of 5 years (2006–2010). The findings showed that suicide mortality has slightly increased over the study period. The findings also indicated that there were substantial overall, gender and social disparities in the distribution of suicide mortality across the country and it was higher in the provinces with lower social rank. These disparities were generally stable and persistent over the study period.

The findings from the current study showed an inverse association between the provinces’ social rank and suicide mortality in Iran. Although the studies on association between area social rank and suicide mortality reported mixed results,9 26 the results of this study are in line with previous ecological studies investigating the relationship between socioeconomic characteristics and suicide rates, in particular those studies focused on high-income settings.9 27–33 Rehkopf and Buka,9 in their systematic review of suicide and socioeconomic characteristics of geographical areas found that, among studies with statistically significant results, 50% and 73% of studies reported an inverse relation between area income and education characteristics and completed suicide, respectively. They also found that the probability of reporting an inverse relationship between area social rank and suicide mortality was higher among the studies conducted in Asia (94% of studies with statistically significant results).9 Similar findings were reported by another study34 focusing on countries in the Eastern Mediterranean region (where Iran is located), indicating that high-income countries had lower suicide mortality rates than their low-income and middle-income counterparts. It is argued that people in the provinces with lower social rank generally have more adverse experiences, poorer mental health, lower access to psychiatric services and lower access to health facilities. These factors might partly explain higher suicide mortality rate in the provinces with lower social rank in Iran.

The four Western provinces of Iran (ie, Ilam, Kermanshah, Lorestan and Hamedan) had the highest suicide mortality rate in the country. One potential explanation for this observation can be the low socioeconomic status of these provinces. These provinces are among the provinces with the highest unemployment rate and lowest HDI in the country. High divorce rates in these provinces (except for Ilam) can be another potential explanation, as divorce is considered as a risk factor for suicide mortality.35 36 In addition, cultural issues such as the tribal structure of communities and the extreme fanaticism prevailing in these provinces have been considered as another potential explanation for this finding.37

The high gender gap in suicide mortality rates observed in the current study is in line with the previous epidemiological studies in Iran3 4 14 and is comparable to the studies conducted in other settings, in particular high-income countries.6 9 38 39 Although many studies, including the previous studies in Iran,3 4 14 have shown higher suicide attempt rates among females, completed (fatal) suicides are higher among males. One potential explanation can be the difference in methods of attempting suicide among males and females. For example, the most common methods of attempting suicide used by males in Iran are by hanging and using firearms, which have higher fatality rates compared with the self-burning method commonly used by females.3 14 39 40 Greater psychosocial impact of problems, such as unemployment or retirement, on males compared with females39 41 42 and adopting coping strategies such as emotional inexpressiveness, lack of help-seeking, risk-taking behaviour, violence, alcohol abuse and drug misuse by males (which are triggered by norms of traditional masculinity)43 44 are other potential factors that have been discussed in the literature. The findings of the gender analysis are important for designing and implementing suicide prevention strategies as the factors, patterns and behaviours associated with suicide are affected by gender.

Temporal analysis of suicide mortality showed interesting results, indicating that among five quintiles of HDI it was only the highest quintile that experienced a significant change in suicide mortality over the study period. This finding can potentially be explained by the increasing prevalence of mental disorders, rising unemployment rates13 45 and an increasing trend in divorce rates13 in the provinces with higher HDI, such as Tehran, the capital city of Iran.

To our knowledge, this is the first national study evaluating social inequalities across different regions over time. Although this study was conducted in the context of Iran, the findings may also be applicable to other middle-income countries, in particular countries in the Middle East region, which share a similar culture. Moreover, we believe that, in terms of methodology, our analysis presents a good example for employing a triangulation of different methods for evaluating inequalities in suicide mortalities. However, the current study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting its findings. First, age and gender differences between the provinces were naïvely adjusted, which might not have fully captured differences in age distribution across provinces. Second, there is the issue of availability and quality of data on suicides, which is common in developing country settings26 46 and leads to underestimation and misclassification of suicide. This might be an issue in this study because of the social stigma of suicide and religious sanctions and some legal issues in the Iranian context.4 34 Moreover, the underestimation and misclassification of suicide mortality might be more common in the provinces with lower social rank; therefore, we expect the social disparity to be more profound than what has been reported here. Third, the current study is an ecological study using province as unit of analysis, which embraces substantial heterogeneity within provinces. This implies that the observed disparities in suicide mortality are between provinces and they are not necessarily applicable to smaller geographic units or individuals. No causal inference can be drawn due to the ecological nature of the study and, furthermore, there was no control for confounders in this study.

Conclusion

The present study indicated that there were substantial overall, gender and social disparities in the distribution of suicide mortalities across the provinces in Iran. Moreover, the study showed an inverse association between the provinces’ social rank and suicide mortality. The findings imply that prevention resources should be targeted in high-risk groups, in particular men in the provinces with low socioeconomic status. Further investigations are needed to explain these disparities in suicide mortality across the provinces. Moreover, more studies are needed to explore the association of socioeconomic factors and suicide (attempted and fatal), focusing on smaller geographical units and at the individual level, in order to design better prevention strategies.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: AAK was involved in the study conception and design, data collection and analysis, interpretation of the data and writing the manuscript. HH-B and SS were involved in the study design, results interpretation and writing the manuscript. HS was involved in the study design, data collection and finalisation of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Patton GC, Coffey C, Sawyer SM, et al. Global patterns of mortality in young people: a systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet 2009;374:881–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertolote JM, Fleischmann A. A global perspective on the magnitude of suicide mortality. In Wasserman D, Wasserman C, Eds. Oxford textbook of suicidology and suicide prevention: a global perspective. Oxford University Press, 2009:91– 8 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saberi-Zafaghandi MB, Hajebi A, Eskandarieh S, et al. Epidemiology of suicide and attempted suicide derived from the health system database in the Islamic Republic of Iran: 2001–2007. East Mediterr Health J 2012;18:836–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharif-Alhoseini M, Rasouli MR, Saadat S, et al. Suicide attempts and suicide in Iran: results of national hospital surveillance data. Public Health 2012;126:990–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO. Public health action for the prevention of suicide: a framework. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pompili M, Innamorati M, Vichi M, et al. Inequalities and impact of socioeconomic-cultural factors in suicide rates across Italy. Crisis 2011;32:178–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ikeda RM, Kresnow MJ, Mercy JA, et al. Medical conditions and nearly lethal suicide attempts. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2001;32:60–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirsch JK. A review of the literature on rural suicide: risk and protective factors, incidence, and prevention. Crisis 2006;27:189–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rehkopf DH, Buka SL. The association between suicide and the socio-economic characteristics of geographical areas: a systematic review. Psychol Med 2006;36:145–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Bank. Islamic Republic of Iran. 2013. http://data.worldbank.org/country/iran-islamic-republic (accessed 15 Sep 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Statistical Center of Iran. Iran at a glance. 2013. http://www.amar.org.ir/Default.aspx?tabid=1321 (accessed 15 Sep 2013).

- 12.Farzaneh E, Mehrpour O, Alfred S, et al. Self-poisoning suicide attempts among students in Tehran, Iran. Psychiatr Danub 2010;22:34–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nazarzadeh M, Bidel Z, Ayubi E, et al. Determination of the social related factors of suicide in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2013;13:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shirazi HR, Hosseini M, Zoladl M, et al. Suicide in the Islamic Republic of Iran: an integrated analysis from 1981 to 2007. East Mediterr Health 2012;18:607–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taghaddosinejad F, Sheikhazadi A, Behnoush B, et al. A survey of suicide by burning in Tehran, Iran. Acta Med Iran 2010;48:266–72 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khademi A, Moradi S. Statistical investigation of unnatural deaths in Iran (2001–2010). Tehran, Iran: Forensic Medicine Organization; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montazeri A. Road-traffic-related mortality in Iran: a descriptive study. Public Health 2004;118:110–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.United Nations Development Program. Human Development Index (HDI). http://hdr.undp.org/en/statistics/hdi/ (accessed 1 Dec 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wagstaff A, van Doorslaer E. Overall versus socioeconomic health inequality: a measurement framework and two empirical illustrations. Health Econ 2004;13:297–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahmad Kiadaliri A, Najafi B, Haghparast-Bidgoli H, et al. Geographic distribution of need and access to health care in rural population: an ecological study in Iran. Int J Equity Health 2011;10:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiadaliri AA, Hosseinpour R, Haghparast-Bidgoli H, et al. Pure and social disparities in distribution of dentists: a cross-sectional province-based study in Iran. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2013;10:1882–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shen J, Wildman J, Steele J. Measuring and decomposing oral health inequalities in an UK population. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2013;41:481–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mackenbach JP, Kunst AE. Measuring the magnitude of socio-economic inequalities in health: an overview of available measures illustrated with two examples from Europe. Soc Sci Med 1997;44:757–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cuzick J. A Wilcoxon-type test for trend. Stat Med 1985;4:87–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cavelaars AE, Kunst AE, Geurts JJ, et al. Educational differences in smoking: international comparison. BMJ 2000;320:1102–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bando DH, Brunoni AR, Bensenor IM, et al. Suicide rates and income in Sao Paulo and Brazil: a temporal and spatial epidemiologic analysis from 1996 to 2008. BMC Psychiatry 2012;12:127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang SS, Sterne JA, Wheeler BW, et al. Geography of suicide in Taiwan: spatial patterning and socioeconomic correlates. Health Place 2011;17:641–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fukuda Y, Nakamura K, Takano T. Cause-specific mortality differences across socioeconomic position of municipalities in Japan; 1973–1977 and 1993–1998: increased importance of injury and suicide in inequality for ages under 75. Int J Epidemiol 2005;34:100–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martiello MA, Giacchi MV. Ecological study of isolation and suicide in Tuscany (Italy). Psychiatry Res 2012;198:68–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rezaeian M, Dunn G, St Leger S, et al. Ecological association between suicide rates and indices of deprivation in the north west region of England: the importance of the size of the administrative unit. J Epidemiol Community Health 2006;60:956–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taylor R, Page A, Morrell S, et al. Mental health and socio-economic variations in Australian suicide. Soc Sci Med 2005;61:1551–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tondo L, Albert MJ, Baldessarini RJ. Suicide rates in relation to health care access in the United States: an ecological study. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67:517–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ying YH, Chang K. A study of suicide and socioeconomic factors. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2009;39:214–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rezaeian M. Age and sex suicide rates in the Eastern Mediterranean Region based on global burden of disease estimates for 2000. East Mediterr Health J 2007;13:953–60 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kposowa AJ. Marital status and suicide in the National Longitudinal Mortality Study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2000; 54:254–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Corcoran P, Nagar A. Suicide and marital status in Northern Ireland. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2010;45:795–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aliverdinia A, Pridemore WA. Women's fatalistic suicide in Iran: a partial test of Durkheim in an Islamic Republic. Violence Against Women 2009;15:307–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cleary A. Suicidal action, emotional expression, and the performance of masculinities. Soc Sci Med 2012;74:498–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheong KS, Choi MH, Cho BM, et al. Suicide rate differences by sex, age, and urbanicity, and related regional factors in Korea. J Prev Med Public Health 2012;45:70–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shojaei A, Moradi S, Alaeddini F, et al. Association between suicide method, and gender, age, and education level in Iran over 2006–2010. Asia Pac Psychiatry 2014;6:18–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qin P, Agerbo E, Mortensen PB. Suicide risk in relation to socioeconomic, demographic, psychiatric, and familial factors: a national register-based study of all suicides in Denmark, 1981–1997. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160:765–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qin P, Agerbo E, Westergard-Nielsen N, et al. Gender differences in risk factors for suicide in Denmark. Br J Psychiatry 2000;177:546–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hawton K. Sex and suicide—gender differences in suicidal behaviour. Br J Psychiatry 2000;177:484–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moller-Leimkuhler AM. The gender gap in suicide and premature death or: why are men so vulnerable? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2003;253:1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sheikholeslami H, Kani C, Ziaee A. Attempted suicide among Iranian population. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2008;38:456–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vijayakumar L, Nagaraj K, Pirkis J, et al. Suicide in developing countries: (1) frequency, distribution, and association with socioeconomic indicators. Crisis 2005;26:104–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.