Abstract

Objective

Cortical electrical stimulation (CES) has been used extensively in experimental neuroscience to modulate neuronal or behavioral activity, which has led this technique to be considered in neurorehabilitation. Because the cortex and the surrounding anatomy have irregular geometries as well as inhomogeneous and anisotropic electrical properties, the mechanisms by which CES has therapeutic effects is poorly understood. Therapeutic effects of CES can be improved by optimizing the stimulation parameters based on the effects of various stimulation parameters on target brain regions.

Approach

In this study we have compared the effects of CES pulse polarity, frequency, and amplitude on unit activity recorded from rat primary motor cortex with the effects on the corresponding local field potentials (LFP), and electrocorticograms (ECoG). CES was applied at the surface of the cortex and the unit activity and LFPs were recorded using a penetrating electrode array, which was implanted below the stimulation site. ECoGs were recorded from the vicinity of the stimulation site.

Main results

Time-frequency analysis of LFPs following CES showed correlation of gamma frequencies with unit activity response in all layers. More importantly, high gamma power of ECoG signals only correlated with the unit activity in lower layers (V-VI) following CES. Time-frequency correlations, which were found between LFPs, ECoGs and unit activity, were frequency- and amplitude-dependent.

Significance

The signature of the neural activity observed in LFP and ECoG signals provides a better understanding of the effects of stimulation on network activity, representative of large numbers of neurons responding to stimulation. These results demonstrate that the neurorehabilitation and neuroprosthetic applications of CES targeting layered cortex can be further improved by using field potential recordings as surrogates to unit activity aimed at optimizing stimulation efficacy. Likewise, the signatures of unit activity observed as changes in high-gamma power in ECoGs suggest that future cortical stimulation studies could rely on less invasive feedback schemes that incorporate surface stimulation with ECoG reporting of stimulation efficacy.

Keywords: Cortical electrical stimulation, unit activity, local field potentials, electrocorticograms, primary motor cortex

1. Introduction

Although cortical electrical stimulation (CES) has been successfully used for a number of neuroprosthetics and neurorehabilitation applications (Kinoshita et al. 2005; Ativanichayaphong et al., 2008; Lefaucheur 2006; Fitzgerald et al., 2006; Brown et al., 2006), the effects of CES on neuronal activity are still unclear. To be able to understand and interpret the therapeutic effects of CES, it is critical to investigate the effects of CES parameters on neural activity in targeted regions of the brain. In our previous paper, we have shown a significant difference between the effects of pulse polarity (anodic versus cathodic) on unit firing rate recorded from different cortical layers (Yazdan-Shahmorad et al., 2011a). Our results showed an increase in unit activity following anodic stimulation and a decrease in unit activity following cathodic stimulation in lower layers (V-VI) units 500 ms following the offset of stimulation. The opposite effect was seen for the units in upper cortical layers (I-II). In addition, our results indicated that these effects were both frequency- and amplitude-dependent. Although the results presented in our previous work offer an interesting insight to the effects of different CES parameters on the single unit activity recorded from different cortical layers, the activity of a population of cells following stimulation could provide a broader perspective on the effect of CES on local network activity. Neuronal signals such as the local field potential (LFPs) and electrocorticogram (ECoGs) represent the summation of excitatory and inhibitory synaptic activity of a population of cells (Mitzdorf 1987) and are great candidates to be recorded for investigating real-time network activity following CES (Miller et al., 2007).

Numerous studies have described the patterns of ECoG and LFP activity associated with unit activity in different cortical areas (Ray et al, 2008). It has been demonstrated that unit activity and LFPs are coherent at high frequencies (25-90 Hz) but not at lower frequencies in lateral intraparietal cortex (Pesaran et al., 2002). In work by Spinks et al, primary motor cortex unit activity and LFPs showed reverse correlation in the beta range but positive correlation in the 30-50 Hz frequency range (Spinks et al, 2008). Gamma power of both EEG and LFPs were also found to be highly correlated with unit activity in visual cortex (Whittingstall and Logothetis, 2009). Visually-evoked gamma power of EEG, interacting with the falling phase of delta oscillations, could reliably predict unit firing activity in primary visual cortex through frequency-band coupling (Whittingstall and Logothetis, 2009). Therefore, when focusing on narrowband oscillations, the consensus of the literature points towards strong correlation between the power in the gamma band and unit firing rate. These data suggest that an increase in unit activity induced by CES could be observed as an increase in gamma oscillations.

It has also been shown that strong correlation exists between unit activity and LFPs over much broader frequencies (20-300Hz) (Mukamel et al., 2005) and that high frequency components (>30 Hz; Crone et al., 2006) or broadband components (2-150 Hz; Manning et al., 2009) of these signals represent activation of neuronal populations in the cortex. The changes observed in high-frequency power of these field potentials induced by a natural motor task reflect broadband power spectral change across all frequencies and are not necessarily indicative of synchronous, narrowband neural activity (Miller et al., 2009a,b). Miller and colleagues have shown that the low-frequency components of these changes are distorted by coincident changes in low-frequency, rhythmic (synchronous) oscillations, indicating that only high-frequency components of the broadband change in unit activity can be observed. Manning and colleagues demonstrate that both narrowband and broadband oscillations detected in LFPs could be used to predict the firing of nearby neurons however narrowband oscillations variably predicted unit firing whereas increases in broadband oscillations were positively correlated with increased unit activity (Manning et al., 2009). While all CES likely drives neuronal output during the stimulation, it is not clear how it affects populations of neurons after the offset of stimulation or how long these effects last. Based on these data, we hypothesize that CES will have a profound effect on broad, high-frequency power in recorded LFPs and ECoG following the stimulation and that this high-frequency power is correlated with changes in unit activity driven by CES.

To test this hypothesis, we simultaneously recorded unit activity and LFPs from different cortical layers as well as ECoGs from the surface of the brain. We have recorded these signals from rat primary motor cortex following CES applied with different pulse polarities, frequencies, and amplitudes. Our results showed a high temporal correlation between the effects of CES on unit activity change with the change in the gamma power of the simultaneously recorded LFPs in corresponding cortical layers. In addition we observed a high temporal correlation between the effects of CES on unit activity change in lower layers (V- VI) with the change in the high gamma power of the simultaneously recorded ECoGs. These data suggest that electrical stimulation from the cortical surface affects layer V-VI pyramidal cell activity manifest as high gamma oscillations recorded at the cortical surface and gamma oscillations recorded in each layer of cortex. These results show that field potential recordings such as LFPs and ECoGs could be used to monitor the effects of CES on spiking activity. These findings could be specifically useful in the development of closed-loop cortical stimulation. The signatures of stimulation effects on unit activity observed in ECoG show that future cortical stimulation studies could rely on less invasive control systems that incorporate surface stimulation with recording. These results suggest that CES efficacy could be controlled in real-time by observing high-gamma power recorded from the cortical surface, a less invasive and lower bandwidth approach to neurorehabilitation.

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects

Six normal male rats (Charles River Laboratories) were used in this study. All surgical procedures were carried out with University for Laboratory Animal Medicine (ULAM) and University Committee on Use and Care of Animals (UCUCA) approved protocols at the University of Michigan. Anesthesia was initiated and maintained either through inhalational anesthesia with isoflurane or intraperitoneal injections of a mixture of ketamine/ xylazine. In case of isoflurane anesthesia for initial induction the concentration was 5% and animals were maintained between 1.75-2.25 % based on breathing and heart rate recorded by pulse oximetry. In case of intraperitoneal injections, 50 mg/ml ketamine, 5 mg/ml xylazine and 1 mg/ml acepromazine at an injection volume of 0.125 ml/100 g body weight was initially injected. To maintain anesthesia, at every subsequent hour of surgery, 0.1 ml ketamine (50 mg ml–1) was delivered to the animal.

Animals were implanted with six bone screws that allowed recording ECoG signals over three location of primary motor cortex. An additional bone screw was used to deliver cortical electrical stimulation to primary motor cortex (Figure 1a). Finally, a micro-scale penetrating electrode array (NeuroNexus Technologies) consisting of 16-electrodes spaced 100 μm apart (Figure 1a-b) was implanted to span the entirety of 6-layer neocortex (Kipke et al., 2003). This electrode array was implanted to record extracellular action potentials and LFPs from each cortical layer. It was angled toward the cortical stimulation electrode such that extracellular action potentials and LFP recordings had a high probability of being affected by the cortical stimulation (Figure 1b). Animals were given 7–10 days to recover post-surgery before experiments were started. The impedances of the recording sites in the linear array was measured in-vivo and ranged from 200 KΩ to 15 MΩ. High impedance sites (>3 MΩ) were considered damaged and thus were removed from our dataset. Impedance of the stimulation screws were less than what could be reliably measured but had an average resistance of 70 Ω.

Figure 1.

a) Horizontal schematic of the rat skull showing the locations of craniotomy, implanted CES screws, recording ECoGs and penetrating silicon probe. The current sink was shorted to a much larger bone screw (depicted). Rostral is to the right, b) Conceptual cross section in the sagital plane of the implanted probe enlarged from the gray box in (a) (rostral is to the right). The penetrating electrode was angled toward the cortical stimulation electrode such that recorded extracellular action potentials and local field potentials had a high probability of being affected by the cortical stimulation (electrodes are on the side of the silicon shank that faces the current source), c) Pulse shapes: Constant current CES was delivered in two configurations, cathodic or anodic consisting of pulse trains. Pulses consisted of square leading phase (100μsec) followed by an exponentially decaying second phase to balance charge. The pulse width of the leading phase was fixed at 100μsec and the length of the trailing phase varied according to leading phase current in order to balance the charge. This figure is partly reproduced from Yazdan-Shahmorad et al., 2011a.

2.2. Electrophysiological Recordings and Stimulation protocol

Animals were placed in a faraday cage where all signals could be routed through a commutator to a wireless stimulation device (Northstar Neuroscience) and multichannel neural signal amplifier (MNAP, Plexon Inc., Dallas, TX). Animals were allowed to freely explore the cylinder and were not restricted or performing a behavioral task. LFP and spike data were recorded using the penetrating electrode array implanted beneath the stimulating electrode. For spike recordings, the signals were filtered with a four pole hardware passband of 150-8000Hz, further amplified and sampled at 40kHz. To record the spike data, a different threshold was set manually for each channel at the beginning of the experiment that was at least 1 stdev above the noise threshold on each channel and judged based on its stereotypic, tri-phasic waveshape. The spike timing and wave-shapes were stored from 150μs before to 700μs after threshold crossing. Events were sampled at 25μs resolution. Unit activity was sorted offline using principle component “clusters” in Offline Sorter software (Plexon Inc., Dallas, TX) to discriminate multiple units recorded on a single electrode and further isolate noise. Units with low firing rate (<3Hz) were removed from the dataset. LFP data were filtered with a monopole hardware band pass from 1 - 500Hz, and were digitally sampled at 1000 Hz (Plexon Inc, Dallas,TX). As shown in Figure 1, three bone screws were implanted over the right primary motor cortex for ECoG recordings. In our experiments the ECoG data were also recorded, band pass filtered 1 - 500Hz, and were digitally sampled at 1000 Hz (Plexon Inc, Dallas,TX).

Constant current CES was delivered in two configurations, cathodic or anodic consisting of pulse trains at frequencies of 25, 50, 100, 250, or 500Hz. Pulses consisted of square leading phase (100μsec) followed by an exponentially decaying second phase to balance charge of length dependent upon the amplitude of the leading phase (Figure 1c). Prior to starting the stimulation, a Movement Inducing Current (MIC) was determined for each frequency. MICs were determined as the weakest current passed through the cortical electrode that caused a forced movement in 50% of test pulses (Brown et al., 2006; Teskey et al., 2003). The average measured MIC for anodic and cathodic was 2.33±0.21 and 2.44±0.21 mA respectively. Once MICs were determined, 25, 50, and 75% of MIC was calculated. Recording sessions proceeded as follows: An entire session consisted of either cathodic or anodic stimulation pulses. A random combination (without replacement) of stimulation frequency and percentage of MIC current was chosen to be presented to the animal in 25 repetitions of 1 sec of stimulation followed by 4 sec of recording.

2.3. Microlesioning and Histology

Upon completion of the experiment, electrolytic lesions were made followed by histological analysis to determine the electrode site locations within the different cortical layers (Yazdan-Shahmorad et al., 2011a,b, Parikh et al., 2009). In all cases, electrodes extracted from the brain were intact and were kept attached to the skull/headcap (Figure 2b). 100μm coronal slices were stained with a standard cresyl-violet (Nissl) staining method (Figure 2a). Exact stereotaxic positions of lesion marks and probe tracts were identified by co-registering histological images to the estimated probe locations from the images of the intact electrode arrays (Yazdan-Shahmorad et al., 2011a,b, Parikh et al., 2009).

Figure 2.

a) Histology images taken from one rat. Three lesion marks are shown at different depths where the electrode was implanted in this series of serial slide sections. b) Image of explanted skull: The angle and depth of the probe was estimated using these images.

2.4. Point Process Model Analysis

Each unit was modeled with point process likelihood framework to relate the spiking propensity of each unit to factors associated with the stimulation parameters (frequency and amplitude) in the time intervals before the onset and after the offset of stimulation as described in detail in our previous work (Yazdan-Shahmorad et al., 2011a). The point process framework provides a flexible, computationally efficient approach for maximum likelihood estimation, goodness-of fit assessment, model selection, and neural coding (Truccolo et al., 2005). Briefly, a point process is a set of discrete events that occur in continuous time (eg, the number of neuronal spikes in a given time interval) and is characterized entirely by the conditional intensity function (CIF), which is a history-dependent generalization of the rate function for the Poisson process. It provides a canonical representation of the stochastic properties of a neural spike train. To analyze the spiking propensity of the neurons, we define the CIF as a function of stimulation frequency or amplitude in which time was divided into five intervals of 500 ms before the onset and after the offset of stimulation. The model was then fit to the neural spike trains using general linear model (GLM) methods (Amassian et al., 1992). These analyses were performed in Matlab. GLM provides an efficient computational scheme for model parameter estimation and a likelihood framework for conducting statistical inferences based on the estimated model (Brown et al., 2002; 2004).

2.5. Time-Frequency Spectral Analysis

To compare the effects of CES parameters on unit activity described above with the effects on LFPs and ECoGs, we performed time-frequency spectral analysis on these signals recorded before the onset and after the offset of CES. We used multitaper methods of spectral analysis on the recorded ECoG and LFP data. These methods have been successfully applied to neurobiological data in recent work (Pesaran et al., 2002; Mitra et al., 1997; Prechtl et al., 1997; Mitra and Pesaran 1999, Mitra and Bokil 2007, http://chronux.org). Multitaper methods involve the use of multiple data tapers for spectral estimation. A variety of tapers can be used, but an optimal family of orthogonal tapers is given by the prolate spheroidal functions or Slepian functions. These are parameterized by their length in time, T, and their bandwidth in frequency, W. For each choice of T and W, up to K=2TW-1 tapers are concentrated in frequency and suitable for use in spectral estimation (Slepian and Pollack 1961). The spectral analyses were designed to capture the temporal variations in frequency components of the recorded LFPs and ECoGs following the co-variation of CES parameters. The goal of these analyses was to find a signature of unit activity change in temporal variation of frequency components in these signals as the result of stimulation. After calculating the spectrograms they were z-scored to baseline. We defined the 500ms before the onset of stimulation as the baseline and compared the spectrograms in the four 500 ms time intervals (0-500,500-1000,1000-1500,1500-2000ms) after the offset of stimulation with baseline to estimate the effects of CES on different frequency bands. To obtain a z-score spectrogram, the mean of the baseline was subtracted from the spectrograms, and the result divided by the standard deviation of baseline. This process was done separately for each frequency component of the spectrogram to normalize for the power ranges of different frequency components of the signal. For our analyses, we used the z-scores of the LFPs and ECoGs in different frequency bands of beta (15-30Hz), gamma (30-200 Hz) and high gamma (60-200Hz) from the corresponding spectrograms in time intervals after the offset of stimulation.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

To estimate the effect of various parameters in different depths of motor cortex, the neuron populations were divided into three groups. Group 1 is defined as Layers I-II (0-400μm), Group 2 as Layers III-IV (400-750μm) and Group 3 as Layers V-VI (750-1800μm) below the cortical surface (Skoglund et al., 1997). We used these groups to compare the effects of CES on different frequency bands of LFPs and ECoGs with unit activity. ANOVAs were constructed in SPSS Statistics 18 (IBM Company, Chicago, IL) for changes observed in the z-score of each frequency band in LFPs and ECoGs as shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Details of the constructed ANOVAs for changes observed in the z-score of each frequency band in ECoGs and LFPs for amplitude and frequency parameters. The parameters in the table are pulse polarity (anodic vs cathodic), percent movement induced current (MIC; 25,50,75,100%), Frequency (25, 50, 100, 250, 500Hz), Depth (Layers I-II, III-IV, V-VI) and time intervals (0-500,500-1000,1000-1500,1500-2000ms after the offset of the stimulation).

| Stimulation Amplitude | Stimulation Frequency | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Modalities | LFPs | ECoGs | LFPs | ECoGs |

|

| ||||

| ANOVA size | 2×4×3×4 | 2×4×4 | 2×5×3×4 | 2×5×4 |

| 2: Pulse Polarity | 2: Pulse Polarity | 2: Pulse Polarity | 2: Pulse Polarity | |

| 4: % MIC | 4: % MIC | 5: Frequency | 5: Frequency | |

| 3: Depth | 4: Time Intervals | 3: Depth | 4: Time Intervals | |

| 4: Time Intervals | 4: Time Intervals | |||

Based on significant interactions effects (p < 0.05, e.g. pulse polarity × frequency × layer) further ANOVA were constructed given that there were only two pulse polarities (e.g., 5×3×4 of factors frequency × depth × time for each pulse polarity) such that post-hoc tests could be performed to determine the significance of each factor (e.g. anodic pulse polarity in upper layers × frequency). The multi-factorial analysis of variance with repeated measures is designed to first test the effects of each factor (within each factor) prior to testing between factors (interactions). Once a significant interaction was found, further ANOVA were created between factors to determine those parameters driving the significant difference.

To investigate the relationship between the effects of different stimulation parameters on unit activity, LFPs and ECoGs, we performed further statistical analysis. We calculated the correlation between the changes in unit activity following stimulation (reported in Yazdan-Shahmorad et al., 2011a) with the changes in the z-scores of each frequency band in LFPs. In addition, to investigate the relationship between the ECoG recorded from the surface of the brain with the underlying cortical layers, we calculated the correlation between the changes in the z-scores of each frequency band in ECoGs with the changes in unit activity and the corresponding z-scores in the LFP signal for each of the three layer categories separately.

3. Results

The post-stimulus effects of CES pulse polarity, frequency and amplitude on LFPs and ECoGs are reported below and compared with the corresponding post-stimulus effects on unit activity. The results of post-stimulus effects on unit activity are from 110 units recorded from the six rats used in this study (the number of units from each animal respectively: 17, 21, 10, 19, 15, 28). For more details on the unit activity analysis see Yazdan-Shahmorad et al., 2011a.

3.1. CES pulse polarity

The results of time-frequency spectral analysis on LFPs showed that anodic and cathodic stimulation pulses had a significantly different post-stimulus effect on the gamma (30-200Hz) power of LFPs (p<0.01). No significant changes were seen in the other frequency ranges (p>0.2). Additionally, the time-frequency analysis showed high correlation of gamma power change with the change in unit activity following CES in corresponding layers. These results are summarized in Figure 3. An example waveform of a unit, raster plots and post-stimulus time histogram (PSTH) of a represented unit from each layer category is shown before and after both anodic and cathodic stimulation (Figure 3a). Below each unit are the z-scored LFP spectrograms averaged across trials for the represented electrode (Figure 3b). Our results demonstrate that the gamma power of LFPs recorded from lower layers (V-VI) of rat motor cortex significantly increased following anodic stimulation (p<0.01) in the first 500 ms after the offset of stimulation (Figure 3b, right panel). However in this interval, gamma power in LFPs recorded from the upper cortical layers (I-II) decreased significantly (p<0.005) in the first 500 ms after the offset of stimulation (Figure 3b, left panel). The opposite was observed for cathodic stimulation in both upper and lower layer categories, respectively (p<0.05). Both anodic and cathodic stimulation caused an increase (p<0.01) in the gamma power of LFPs in layers III and IV (Figure 3b, middle panel) after the offset of stimulation. These data demonstrate that the effects of CES pulse polarity on unit activity change are highly correlated with the changes in gamma power of corresponding LFPs for all of the layer categories (r>0.85).

Figure 3.

The effects of anodic versus cathodic stimulation on LFPs regardless of stimulation frequency and amplitude. a) In each layer category an example waveform of a unit, raster plots and post-stimulus time histogram (PSTH) of the represented unit for both anodic and cathodic stimulation are shown. Each dot in the raster represents a single spike event. Each row of the raster represents a separate trial. Vertical shaded bars represent the 1 second stimulus pulse train in which no unit activity was recorded. The PSTH is the average firing rate of the unit in spike events per second in 10msec bins. Shaded area is standard error. These examples demonstrate the varying effects of stimulation polarity on unit activity in a range of cortical layers. b) In each layer category, the z-scored LFP spectrograms of the corresponding recording site of the unit shown in (a) across trials is shown. Time is the abscissa; frequency is the ordinate. c) These plots show the mean of the normalized change of unit activity (increase, positive deviation; decrease, negative deviation) from baseline in 500ms intervals after the offset of stimulation color-coded for each layer category for all units. Black lines show the mean of the normalized change of gamma power from baseline in 500ms intervals after the offset of stimulation for LFPs recorded from each layer category. Error bars are standard error. The data in this figure demonstrate a correlation between the effects of stimulation polarity on unit activity with gamma power in LFPs. The unit activity results presented in this figure is reproduced with permission from Yazdan-Shahmorad et al., 2011a.

ECoG spectra showed that anodic and cathodic stimulation pulses had a significantly different post-stimulus effect on the high gamma (60-200 Hz) power of ECoGs (p<0.05). No significant changes were seen in the other frequency ranges (p>0.3). These results are summarized in Figure 4. After the offset of stimulation, an increase in high gamma power of ECoGs is observed following anodic stimulation whereas a decrease following cathodic stimulation was seen (p<0.01). The effects of CES pulse polarity on the high gamma power of ECoGs were highly correlated with unit activity of lower layers (V-VI) (r>0.95). Likewise, there was high correlation between the effects of CES pulse polarity on high gamma power of ECoGs with the gamma power of LFPs recorded from lower layers (r>0.95). These data suggest that the effects of stimulation on unit activity are reflected in the gamma power of LFPs in corresponding layers. More importantly it shows that high gamma power of ECoG signals are representative of the stimulation effects on unit activity in lower layers.

Figure 4.

The effects of anodic versus cathodic stimulation on ECoG regardless of stimulation frequency and amplitude. Formatting is conserved from Figure 3. a) The top plot shows the z-scored ECoG spectrograms of the corresponding LFPs and units shown in Figure 3 across trials. b) The mean of the normalized change of high gamma power in all ECoG recorded signals after the offset of stimulation (shown in black) in comparison with unit activity (UA) for each layer category, for all units. c) The mean of the normalized change of high gamma power in all ECoG recorded signals after the offset of stimulation (shown in black) in comparison with gamma power change in LFP. The data in this figure demonstrate a correlation between the effects of stimulation polarity on units and LFPs located in layers V and VI with high gamma power in ECoG. The unit activity results presented in this figure is reproduced with permission from Yazdan-Shahmorad et al., 2011a.

3.2. CES frequency

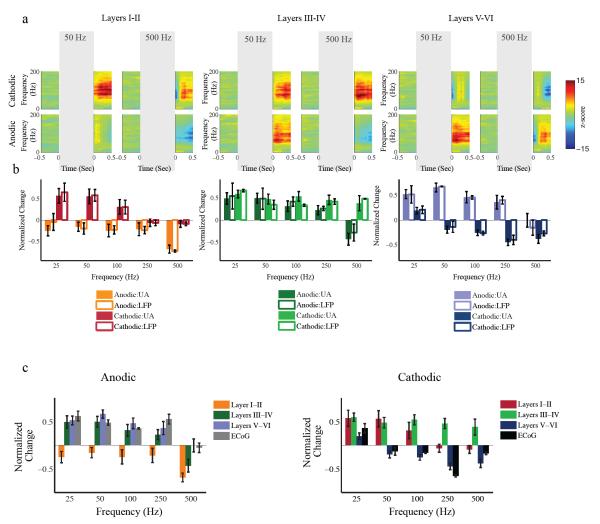

When varying the frequency of stimulation, our results showed that the opposing post-stimulus effects on gamma power observed in LFPs after stimulation were frequency-dependent in both upper and lower layers only (p<0.01, Figure 5). The change in the gamma power of the LFPs was highly correlated with the change in unit activity following all frequencies for all of the layer categories (r>0.9) except for cathodic stimulation in layers III-IV (r=0.36).

Figure 5.

Effects of the frequency of stimulation on LFP and ECoG in layered cortex regardless of stimulation amplitude. a) In each layer category, the top plot shows the z-scored LFP spectrograms of a recording site located in the corresponding layer category across trials before and after cathodic stimulation and for frequencies of 50Hz (left column) and 500Hz (right column). The bottom plot shows the z-scored LFP spectrograms before and after anodic stimulation. Color-coding is the same as Figure 3. b) The mean of the normalized change of unit activity (solid-colored bars) across all units and LFP gamma power (30-120 Hz) change (white bars) across all LFPs as the function of stimulation frequency and polarity. The error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. c) The mean of the normalized change from baseline of high gamma power in all ECoG is shown for the first 500ms interval after the offset of stimulation in comparison with unit activity as a function of stimulation frequency and polarity. These data demonstrate that the polarity- and frequency-dependent change in unit activity is highly correlated with gamma power in the LFP and high-gamma power in the ECoG. The unit activity results presented in this figure is reproduced with permission from Yazdan-Shahmorad et al., 2011a.

Similarly, post-stimulus effects on ECoGs were frequency-dependent. When varying the frequency of stimulation, our results showed opposing anodic vs. cathodic effects observed in high gamma power of ECoGs (60-200 Hz) (p<0.05, Figure 5c). The change in the high gamma power of ECoG was highly correlated with the change in unit activity of the lower layers (V-VI) following all frequencies of stimulation (r>0.85).

3.3. CES amplitude

Post-stimulus effects on gamma power of LFPs observed in upper and lower layers and high gamma power of ECoGs were also amplitude-dependent (p<0.01, Figure 6). The change in the gamma power of LFPs was highly correlated with the change in unit activity following all amplitudes of stimulation in each of the layer categories (r>0.85). Likewise, the change in the high gamma power of ECoGs was correlated with the change in unit activity of the lower layers (V-VI) following all amplitudes of stimulation (Figure 6b).

Figure 6.

Effects of the amplitude of stimulation on LFP and ECoG regardless of stimulation frequency. a) The mean of the normalized change of unit activity (solid-colored bars) across all units and LFP gamma power (30-120 Hz) change (white bars) across all LFPs as the function of stimulation amplitudes for anodic (light shading) and cathodic (dark shading) stimulation consistent with the color coding in previous figures. b) The mean of the normalized change of high gamma power in all ECoG recorded signals (increase, positive deviation; decrease, negative deviation) is shown compared to unit activity as a function of stimulation amplitude. The unit activity results presented in this figure is reproduced with permission from Yazdan-Shahmorad et al., 2011a.

3.4. Short-term temporal effects of CES

To capture the full dynamic of the post-stimulation effects of CES, we performed a t-test of the null hypothesis that data in 1500-2000 ms time interval after the offset of stimulation are a random sample from a normal distribution with mean 0 and unknown variance, against the alternative that the mean is not 0. The null hypothesis was rejected for Cathodic-first stimulation (p<0.01) and was accepted for Anodic-first stimulation (p=0.48, 0.36, 0.45 for unit activity, LFP and ECoG respectively). This indicates that the effects of Cathodic-first CES on neural activity lasts at least 2 sec following the offset of stimulation while the effects of Anodic-first CES lasts up to 1.5 sec after the offset of stimulation. To investigate the post-stimulus effects of CES for cathodic stimulation after 2 seconds following the offset of stimulation, we have done further analysis.

We have calculated the model parameters for the unit activity 2000-2500 ms time interval after the offset of stimulation and performed the null hypothesis (see Yazdan-Shahmorad et. al, 2011a). In addition we calculated the z-scored spectrograms for the ECoGs and LFPs at this time interval in the corresponding frequency bands. The null hypothesis was accepted for this time interval for Cathodic-first stimulation (p=0.16, 0.34, 0.24 for unit activity, LFP and ECoG respectively). Considering that the null hypothesis was rejected for the 1500-2000 ms time interval after the offset of stimulation, we conclude that the effects of Cathodic-first CES on unit activity, LFP and ECoG lasts 2 sec following the offset of stimulation.

4. Discussion

In this study, we have focused on investigating the post-stimulus effects of CES pulse polarity of various frequencies and amplitudes on field potentials recorded intracortically (LFPs) as well as surface recordings (ECoGs) and compared the results with the corresponding effects on spiking activity in all cortical layers (Yazdan-Shahmorad et al., 2011a).

It is well known that the lowest threshold for initiating an action potential through electrical stimulation can be achieved by placing the stimulating electrode near the base of the axon (Gustafsson and Jankowska, 1976) and that there exists a strength (current) – duration (pulse width) – distance relationship (Yeomans et al., 1988) and charge – charge density relationship (McCreery et al, 1990; McIntyre and Grill, 2001) that further govern direct activation of cell bodies vs. fibers (McIntyre and Grill, 2000; for a review see Merrill et al., 2005). Locating the stimulating electrode away from the base of the axon to the surface of layered cortex greatly increases threshold for activation. Selective activation of layered cortex through CES is further complicated by cellular organization within the layers. The polarity of CES, as demonstrated in unit activity (Yazdan-Shahmorad et al., 2011a) and in LFPs and ECoGs (shown in this study), can have a profound and varied effect on action potential generation due to the dominant layer V dipole orientation of underlying cortex. While in these studies we did not change the pulse width of stimulation or alter charge-charge density relationships, we demonstrate that polarity effects are also dependent upon the co-variation of frequency and amplitude of stimulation. It is clear that selective activation of underlying cortex with CES is dependent upon stimulation parameters: electrode configuration and shape, polarity, amplitude, pulse width (and resulting charge density), and frequency, as well as the dipole organization of underlying layered cortex. While this is a highly complex parameter space, our results begin to identify the CES parameters that selectively drive post-stimulation activation/inactivation of layered cortex. The data presented here demonstrate that the post-stimulation effect of CES on unit activity is most directly correlated with changes in the broad gamma frequencies recorded in each cortical layer as LFPs and as relatively narrower high-gamma activity recorded at the cortical surface as ECoGs representative of the deep cortical layers.

4.1. Effects of CES parameters on LFPs

The results of time-frequency spectral analysis on LFPs showed that anodic and cathodic stimulation pulses had a significantly different post-stimulus effect on the gamma power (30-200Hz) of LFPs recorded from upper and lower cortical layers. The changes observed in the gamma power of LFPs as the result of stimulation were highly correlated with the effects of stimulation on unit activity recorded on the same electrodes. These results were frequency- and amplitude-dependent.

LFPs are defined as low-frequency component (<200Hz) of the recorded neural activity and reflect the spatial and temporal superposition of the synaptic input to a local population surrounding the electrode (Mitzdorf 1985). These signals are thought to represent the synaptic activity of a few thousand neurons, depending on the tip diameter of the recording electrode (Nunez 1981, 1995). While lower-frequency activity in the LFPs are thought to be due to the activity of a larger population of neurons, higher frequencies typically reflect a smaller population (Nunez 1981). Frequencies higher than 300 Hz are likely dominated by action potential currents (Logothetis 2002). Therefore, it is expected to see a high correlation between the high-frequency activity in LFPs with the firing of a few neurons located close to the recording electrode (Ray et al., 2008). Our results agree to a degree with this hypothesis as we see a high correlation between the high gamma power of LFPs with the unit activity in each of the cortical layers, as previous studies have shown that power in the high gamma range (60–200 Hz) is tightly coupled to the firing rates of a small population of neurons (Ray et al., 2008; Belitski et al., 2008). The high correlation that we see in the low gamma range (30-60Hz) as well as the high gamma range with unit activity in our results could be due to synchronization induced in layer V pyramidal cells by the stimulation. While an increase in high-gamma could be attributable to an increase in spike synchronization within the neural population, an increase in low gamma power could be attributable to an increase in synchronization in synaptic inputs, as synaptic activity is correlated with the low-gamma frequency range (Ray et al., 2008). Regardless of any synchronization that may occur during stimulation, it is clear from our results that following the offset of stimulation, there is a lack of tightly-coupled oscillations manifest as increases or decreases in broad-band synaptic activity that lasts for seconds.

The seconds-long, frequency-dependent nature of the change in activity following CES has been shown to be a result of short-term changes in synaptic strength and release. High-frequency stimulation can cause synaptic fatigue resulting in a reduction of synaptic drive and release (Lee et al, 2004). Stimulation-induced, sustained γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) release, an inhibitory neurotransmitter, has been shown to effect continuous inhibition on post-synaptic neurons that lasts for seconds (Liu et al., 2012). While we do not understand the networks of neurons that are being affected by CES, it is clear that the frequency of stimulation can have lasting effects on these networks at a synaptic level.

Electrical stimulation at the cortical surface could be driving unit activity synaptically in lockstep during the stimulation (both cathodic and anodic) that does not result in a tightly-driven oscillation after the offset of stimulation but a broad-band increase or decrease in high-frequency activity of a network of units. The higher frequency components of LFPs (>120Hz) probably have a greater relative contribution from the generation of action potentials, whereas the size of the neural population (that generates the activity at that frequency) decreases with increasing LFP frequency (Nunez 1981). Therefore, based on our results, the broad gamma frequency range (30-200Hz) appears to be well suited for studying the spiking activity of a relatively small population of neurons in each cortical layer through LFP recordings following cortical electrical stimulation.

As it is described in the methods there is overlap between the frequency ranges of the hardware filters when separating spikes from LFPs in our recording system. This raises concern that the correlations observed between spikes and LFPs could be due to this overlap. It has been shown that even in cases where there is no overlap between the frequency bands of the spikes and LFPs in hardware filtering, there are still low frequency components of the spikes that will remain in the LFPs (Zanos et al 2010). Although Zanos et al 2010 propose a more efficient method to minimize the residual spectral content of spikes in LFPs, we were unable to apply that technique to our data as the filter specifications were hard-wired in our recording hardware (see methods section). However we have estimated the degree of spike data contamination in our filtered LFP (see supplementary material), and show that this contamination can be seen in these spectrograms up to z-scores of 1.42, which is significantly smaller than the z-scores observed in our LFP data (significant increases in our data are observed in z-scores higher than 8.34, p<0.05). This suggests that although z-scores of about 1.4 in our LFP time-frequency analysis could be due to the spike contamination in the LFP data, the remaining is due to the effects of stimulation in the affected neural network. However, given the mentioned limitations of our experimental hardware, further experiments will need to be performed to investigate the precise effects of these stimulation parameters on the LFP data.

4.2. Effects of CES parameters on ECoGs

The ECoG recordings in this study are limited in that they are spatially located some distance (mm) away from the stimulating electrode. Therefore we are unable to directly measure the post-stimulus response directly beneath the stimulating electrode, but are recording changes in synaptic activity of spatially disparate networks of neurons. This caveat is important in that modeling of CES has shown that the activation function directly below the electrode opposes the activation function of the periphery of the electrode (not to mention charge density effects associated with the shape of the electrode). That is, dipoles oriented perpendicular to and directly below the stimulating electrode are highly activated during anodic stimulation whereas dipoles oriented perpendicular to and outside the boundary of the stimulating electrode have a negative activation function (Wongsarnpigoon and Grill. 2008). The opposite holds for dipoles oriented parallel to the CES electrode for the same polarity. Therefore, the results in this study may be more representative of the edge effects of CES – the post-stimulus activation of populations of neurons on the periphery of the stimulation. Further analysis with a micro-ECoG grid and the ability to record through the stimulating electrode should address these issues.

Considering the spatial arrangement of the ECoG electrode relative to the stimulating electrode, the results of time-frequency spectral analysis showed a significantly different post-stimulus effect on the high gamma (60-200Hz) power. The changes observed in the high gamma power of ECoGs were highly correlated with the effects of stimulation on unit activity of the lower layers (V-VI) only. These results were also polarity, frequency, and amplitude-dependent. While LFP high-gamma activity may only reflect the firing rate of the neural population near the microelectrode, the ECoG can provide an index of neural synchrony at a larger level of integration. It has been shown that the change in high-gamma power in the ECoG signal is due to changes in firing rate or synchronization in the underlying neural population (Ray et al., 2008; Crone et al., 2006) or as a broad-frequency, asynchronous increase in unit activity (Miller et al., 2009a,b). Most of the power recorded by the ECoG electrode is due to synaptic activity (Nunez 1981, 1995), so it is hypothesized that the contribution of the action potentials is small and spatially limited. Our results agree with this hypothesis, however the surprising result is that we only see correlation between the high gamma power of ECoGs with the unit activity of the lower cortical layers and that this increase or decrease in activity is limited to a much narrower gamma range than seen in the LFPs.

As high frequency activity does not travel far spatially, we were expecting to see a high correlation between the high gamma power of ECoGs with the unit activity of the upper cortical layers. It is important to keep in mind that the dipoles in upper layers are much less organized than the dominant pyramidal cells in lower layers oriented perpendicular to the CES electrode (Humphrey et al., 1970). Indeed, the dipole orientation is profoundly affected by the polarity of CES (Wongsarnpigoon and Grill. 2008). As the high gamma activity in ECoG represents synaptic integration in the underlying cortical neurons, these highly organized pyramidal cells play a more dominant role in this frequency band. Another possibility is that the ECoGs are representative of electrical activity from the apical dendrites of the pyramidal cells. This however, raises the question as to why we don’t see this signature in the LFP recordings in the upper cortical layers. There are two possible explanations for these results. One is that ECoG electrodes are placed in a different orientation than the LFP electrodes with respect to the neural population and their resultant dipoles. Modeling CES demonstrates that neurons perpendicular to the orientation of the CES electrode (such as pyramidal cells) are activated by anodic stimulation and cells oriented parallel are activated with cathodic stimulation (Wongsarnpigoon and Grill. 2008), suggesting that stimulation polarity selectively potentiates current influx and efflux at different laminar layers. Another explanation is that the surface area of the ECoGs are ~20,000x larger than the LFP recording sites. This means that we are “listening” to the neural activity of a much larger, spatially distributed population of neurons in which the relatively highly-organized pyramidal cell layer dipole dominates the ECoG signal compared to LFP recordings.

Our results suggest that broad high-gamma activity in ECoG recordings of a large population is a useful indicator of the firing dynamics of the neural population whose activity is being altered by stimulation. This key finding could potentially be used to characterize the spatially distributed, relatively long-lasting “after effects” of stimulation in the underlying neural activity, particularly layers V-VI. We propose ECoG as a less-invasive indicator of CES effects on unit activity of layers V-VI in underlying and surrounding cortex manifest as broad activation/inactivation of gamma frequencies.

4.3. Clinical applications

LFPs and ECoGs show potential for monitoring the signatures of neural population activity before, during, and after CES to modify subsequent stimulus pulses in real time. ECoG and LFP offers a better estimation of long-term recording stability in comparison to unit spike data and require lower sampling rates for data acquisition, eliminate the need for spike detection and sorting algorithms, and reduce the computational costs associated with single-unit recordings.

The ECoG is a relatively low-bandwidth, minimally invasive recording method for monitoring the activity of a population of the primary output neurons of the cortex. Our data suggests that changes observed in high-gamma activity in the ECoG is a direct surrogate for the output of layer V pyramidal neurons following CES. These data could then be used in real-time to indirectly determine stimulation effect. The high-gamma ECoG signature presented here could be used as a starting point for selecting CES parameters that generally increase or decrease output of layer V, post stimulus. For example, these results suggest that it is possible to affect an overall increase in the output of layer V motor cortical neurons by stimulating the cortex with anodic pulses that are 25% of movement-inducing current at 50 Hz alternating 1 s on, 500 ms off. Alternatively, it is possible to affect an overall decrease in the output of layer V by stimulating the cortex with cathodic pulses that are 25% of movement-inducting current at 250 Hz alternating 1 s on 500 ms off. These examples are by no means exhaustive and require further investigation, however highlight the ability to determine the ongoing effect of CES on layered cortex through relatively simple ECoG recordings. The result of CES on long-term changes in cortical excitability however, remains a question. In interpreting and comparing the results of this study for human applications, it is important to keep in mind that these experiments were done in rat cortex, which does not have gyri/sulci. In human cortex, on the other hand, the orientation of dipoles changes with the surface of cortex at the fold of the gyrus. This needs to be taken into consideration for such applications.

5. Conclusion

In this study, we have focused on investigating the poststimulus effects of CES on field potentials recorded intracortically (LFPs) as well as surface recordings (ECoGs) and compared the results with the corresponding effects on spiking activity in each cortical layer. These signals were recorded from rat primary motor cortex following the application of CES with different pulse polarities, frequencies, and amplitudes. Our results showed a high temporal correlation between the effects of CES on unit activity change with the change in the gamma power of the simultaneously recorded LFPs in corresponding cortical layers. In addition we observed a high temporal correlation between the effects of CES on unit activity change in only the lower layers (V- VI) with the change in the high gamma power of the simultaneously recorded ECoGs. These data suggest that electrical stimulation from the cortical surface affects layer V-VI pyramidal cell activity manifest as high gamma oscillations recorded at the cortical surface and gamma oscillations recorded in each layer of cortex.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This work was supported in part by grants from Northstar Neuroscience, Inc. (all authors), NIBIB P41 EB002030 (AY and DRK), and NIDCD F32 DC7797 (MJL). We give special thanks to G.Gage and T.Marzullo for their helpful discussions. We also thank Paras Patel for providing us with the wideband data for the simulations shown in supplementary material.

References

- Amassian VE, Eberle L, Maccabee PJ, Cracco RQ. Modeling magnetic coil excitation of human cerebral-cortex with a peripheralnerve immersed in a brain-shaped volume conductordthe significance of fiber bending in excitation. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1992;85:291–301. doi: 10.1016/0168-5597(92)90105-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arieli A, Shoham D, Hildesheim R, Grinvald A. Coherent Spatiotemporal Patterns of Ongoing Activity Revealed by Real-Time Optical Imaging Coupled With Single-Unit Recording in the Cat Visual Cortex. Journal of neurophysiology. 1995;73(5):2072. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.5.2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ativanichayaphong T, He JW, Hagains CE, Peng YB, Chiao JC. A combined wireless neural stimulating and recording system for study of pain processing. Journal of neuroscience methods. 2008;170(1):25. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belitski A, Gretton A, Magri C, Murayama Y, Montemurro MA, Logothetis NK, et al. Low-Frequency Local Field Potentials and Spikes in Primary Visual Cortex Convey Independent Visual Information. The journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2008;28(22):5696. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0009-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EN, Barbieri R, Eden UT, Frank LM. Likelihood methods for neural spike train data analysis. Chapman & Hall/CRC Math. Biol. Med. Ser. 2004:253–286. [Google Scholar]

- Brown EN, Barbieri R, Ventura V, Kass RE, Frank LM. The Time-Rescaling Theorem and Its Application to Neural Spike Train Data Analysis. Neural Computation [Neural Comput.] 2002;14(2):325–346. doi: 10.1162/08997660252741149. Vol. 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JA, Lutsep HL, Weinand M, Cramer SC. CLINICAL STUDIES - Motor Cortex Stimulation for the Enhancement of Recovery from Stroke: A Prospective, Multicenter Safety Study. Neurosurgery. 2006;58(3):464. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000197100.63931.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canolty RT, Soltani M, Dalal SS, Edwards E, Dronkers NF, Nagarajan SS, et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics of word processing in the human brain. Front Neurosci. 2007;1(1):185–196. doi: 10.3389/neuro.01.1.1.014.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaday C, Lavoie BA, Barbeau H, Schneider C, Bonnard M. Studies on the corticospinal control of human walking. I. Responses to focal transcranial magnetic stimulation of the motor cortex. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81(1):129–139. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crone NE, Sinai A, Korzeniewska A. High-frequency gamma oscillations and human brain mapping with electrocorticography. EVENT-RELATED DYNAMICS OF BRAIN OSCILLATIONS. 2006;159:275–295. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(06)59019-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald PB, Huntsman S, Gunewardene R, Kulkarni J, Daskalakis ZJ. A randomized trial of low-frequency right-prefrontal-cortex transcranial magnetic stimulation as augmentation in treatment-resistant major depression. The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;9(6):655–66. doi: 10.1017/S1461145706007176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fregni F, Boggio PS, Silva MT, Marcolin MA, Pascual-Leone A, Barbosa ER. Rapid-rate repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation and cognitive function in Parkinson’s disease patients: A safety study. MOVEMENT DISORDERS. 2004;19:S240–S241. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson B, Jankowska E. Direct and indirect activation of nerve cells by electrical pulses applied extracellularly. J Physiol. 1976;258(1):33–61. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1976.sp011405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey DR, Schmidt EM, Thompson WD. Predicting measures of motor performance from multiple cortical spike trains. Science. 1970;170(NN395):758. doi: 10.1126/science.170.3959.758. &. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahanshahi M, Ridding MC, Limousin P, Profice P. Rapid rate transcranial magnetic stimulation - a safety study. Electroencephalography and clinical neurophysiology. 1997;105(6):422. doi: 10.1016/s0924-980x(97)00057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita M, Ikeda A, Matsuhashi M, Matsumoto R, Hitomi T, Begum T, et al. Electric cortical stimulation suppresses epileptic and background activities in neocortical epilepsy and mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Clinical neurophysiology : official journal of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology. 2005;116(6):1291. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kipke DR, Vetter RJ, Williams JC, Hetke JF. COMMUNICATIONS - Silicon-Substrate Intracortical Microelectrode Arrays for Long-Term Recording of Neuronal Spike Activity in Cerebral Cortex. IEEE transactions on neural systems and rehabilitation engineering : a publication of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. 2003;11(2):151. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2003.814443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauss G, Fisher R. Cerebellar and Thalamic Stimulation for Epilepsy. Advances in neurology. 1994;63:231–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KH, Chang SY, Roberts DW, Kim U. Neurotransmitter release from high-frequency stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus. J Neurosurg. 2004;101(3):511–517. doi: 10.3171/jns.2004.101.3.0511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefaucheur JP. Principles of therapeutic use of transcranial and epidural cortical stimulation. 2008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Leuthardt EC, Gaona C, Sharma M, Szrama N, Roland J, Freudenberg Z, et al. Using the electrocorticographic speech network to control a brain-computer interface in humans. J Neural Eng. 8(3):036004. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/8/3/036004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Mogul D. Electrical Control of Epileptic Seizures. Journal of clinical neurophysiology : official publication of the American Electroencephalographic Society. 2007;24(2):197. doi: 10.1097/WNP.0b013e31803991c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu LD, Prescott IA, Dostrovsky JO, Hodaie M, Lozano AM, Hutchison WD. Frequency-dependent effects of electrical stimulation in the globus pallidus of dystonia patients. J Neurophysiol. 2012;108(1):5–17. doi: 10.1152/jn.00527.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logothetis N. The neural basis of the blood-oxygen-level-dependent functional magnetic resonance imaging signal. Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences. 2002;357(1424):1003–1037. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logothetis NK, Kayser C, Oeltermann A. In Vivo Measurement of Cortical Impedance Spectrum in Monkeys: Implications for Signal Propagation. Neuron. 2007;55(5):809. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning JR, Jacobs J, Fried I, Kahana MJ. Broadband shifts in local field potential power spectra are correlated with single-neuron spiking in humans. J Neurosci. 2009;29(43):13613–13620. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2041-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCreery DB, Agnew WF, Yuen TG, Bullara L. Charge density and charge per phase as cofactors in neural injury induced by electrical stimulation. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1990;37(10):996–1001. doi: 10.1109/10.102812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre CC, Grill WM. Selective microstimulation of central nervous system neurons. Ann Biomed Eng. 2000;28(3):219–233. doi: 10.1114/1.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre CC, Grill WM. Finite element analysis of the current-density and electric field generated by metal microelectrodes. Ann Biomed Eng. 2001;29(3):227–235. doi: 10.1114/1.1352640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill DR, Bikson M, Jefferys JG. Electrical stimulation of excitable tissue: design of efficacious and safe protocols. J Neurosci Methods. 2005;141(2):171–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelucci R, Valzania F, Passarelli D, Santangelo M. Rapid-rate transcranial magnetic stimulation and hemispheric language dominance: Usefulness and safety in epilepsy. Neurology. 1994;44(9):1697. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.9.1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KJ. Broadband spectral change: evidence for a macroscale correlate of population firing rate? J Neurosci. 2010;30(19):6477–6479. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6401-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KJ, Sorensen LB, Ojemann JG, den Nijs M. Power-law scaling in the brain surface electric potential. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009a;5(12):e1000609. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KJ, Zanos S, Fetz EE, den Nijs M, Ojemann JG. Decoupling the cortical power spectrum reveals real-time representation of individual finger movements in humans. J Neurosci. 2009b;29(10):3132–3137. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5506-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra PP, Ogawa S, Hu X, Ugurbil K. The Nature of Spatiotemporal Changes in Cerebral Hemodynamics As Manifested in Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1997;37(4):511. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910370407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra P, Bokli H. Observed Brain Dynamics. Oxford: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mitzdorf U. Current source-density method and application in cat cerebral cortex: investigation of evoked potentials and EEG phenomena. Physiol Rev. 1985;65(1):37–100. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1985.65.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitzdorf U. Properties of the evoked-potential generators- current source-density analysis of visually evoked-potentials in the cat cortex. International Journal of Neuroscience. 1987;33(1-2):33–59. doi: 10.3109/00207458708985928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Luna K, Buitrago MM, Hertler B, Schubring M, Haiss F, Nisch W, et al. Cortical stimulation mapping using epidurally implanted thin-film microelectrode arrays. Journal of neuroscience methods. 2007;161(1):118. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukamel R, Gelbard H, Arieli A, Hasson U, Fried I, Malach R. Coupling Between Neuronal Firing, Field Potentials, and fMRI in Human Auditory Cortex. Science. 2005;309(5736):951. doi: 10.1126/science.1110913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa M, Durand D. Suppression of spontaneous epileptiform activity with applied currents. Brain research. 1991;567(2):241–247. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90801-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunez PL. A study of origins of the time dependencies of scalp EEG: ii--experimental support of theory. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1981;28(3):281–288. doi: 10.1109/TBME.1981.324701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikh H, Marzullo TC, Kipke DR. Lower layers in the motor cortex are more effective targets for penetrating microelectrodes in cortical prostheses. Institute of Physics Publishing; 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesaran B, Pezaris JS, Sahani M, Mitra PP, Andersen RA. Temporal structure in neuronal activity during working memory in macaque parietal cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5(8):805–811. doi: 10.1038/nn890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pistohl T, Ball T, Schulze-Bonhage A, Aertsen A, Mehring C. Prediction of arm movement trajectories from ECoG-recordings in humans. Journal of neuroscience methods. 2008;167(1):105. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prechtl JC, Cohen LB, Pesaran B, Mitra PP, Kleinfeld D. Visual stimuli induce waves of electrical activity in turtle cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94(14):7621. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray S, Crone NE, Niebur E, Franaszczuk PJ, Hsiao SS. Neural Correlates of High-Gamma Oscillations (60-200 Hz) in Macaque Local Field Potentials and Their Potential Implications in Electrocorticography. The journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2008;28(45):11526. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2848-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouse AG, Moran DW. Neural adaptation of epidural electrocorticographic (EECoG) signals during closed-loop brain computer interface (BCI) tasks. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2009;2009:5514–5517. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2009.5333180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schalk G, Miller KJ, Anderson NR, Wilson JA, Smyth MD, Ojemann JG, et al. Twodimensional movement control using electrocorticographic signals in humans. J Neural Eng. 2008;5(1):75–84. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/5/1/008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shkolnisky Y. Prolate spheroidal wave functions on a disc-Integration and approximation of two-dimensional bandlimited functions. Applied and Computational Harmonic Analysis. 2007;22(2):235–256. [Google Scholar]

- Skoglund T, Pascher R, Berthold C. The existence of a layer IV in the rat motor cortex. Cerebral Cortex. 1997;7(2):178–180. doi: 10.1093/cercor/7.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinks RL, Kraskov A, Brochier T, Umilta MA, Lemon RN. Selectivity for Grasp in Local Field Potential and Single Neuron Activity Recorded Simultaneously from M1 and F5 in the Awake Macaque Monkey. The journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2008;28(43):10961. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1956-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun FT, Morrell MJ, Wharen RE. Responsive cortical stimulation for the treatment of epilepsy. NEUROTHERAPEUTICS. 2008;5(1):68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2007.10.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teskey GC, Flynn C, Goertzen CD, Monfils MH, Young NA. Cortical stimulation improves skilled forelimb use following a focal ischemic infarct in the rat. Neurological research. 2003;25(8):794. doi: 10.1179/016164103771953871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truccolo W, Eden UT, Fellows MR, Donoghue JP, Brown EN. A point process framework for relating neural spiking activity to spiking history, neural ensemble, and extrinsic covariate effects. Journal of Neurophysiology (Bethesda) 2005;93(2):1074–1089. doi: 10.1152/jn.00697.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren RJ, Durand DM. Effects of applied currents on spontaneous epileptiform activity induced by low calcium in the rat hippocampus. Brain research. 1998;806(2):186. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00723-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittingstall K, Logothetis NK. Frequency-band coupling in surface EEG reflects spiking activity in monkey visual cortex. Neuron. 2009;64(2):281–289. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wongsarnpigoon A, Grill WM. Computational modeling of epidural cortical stimulation. J Neural Eng. 2008;5(4):443–454. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/5/4/009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazdan-Shahmorad A, Kipke DR, Lehmkuhle MJ. Polarity of cortical electrical stimulation differentially affects neuronal activity of deep and superficial layers of rat motor cortex. Brain Stimul. 2011a;4(4):228–241. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazdan-Shahmorad A, Lehmkuhle MJ, Gage GJ, Marzullo TC, Parikh H, Miriam RM, et al. Estimation of electrode location in a rat motor cortex by laminar analysis of electrophysiology and intracortical electrical stimulation. J Neural Eng. 2011b;8(4):046018. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/8/4/046018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeomans JS, Maidment NT, Bunney BS. Excitability properties of medial forebrain bundle axons of A9 and A10 dopamine cells. Brain Res. 1988;450(1-2):86–93. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91547-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanos S. Neural correlates of high-frequency intracortical and epicortical field potentials. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29(12):3673–3675. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0009-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanos TP, Mineault PJ, Pack CC. Removal of Spurious Correlations Between Spikes and Local Field Potentials. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2010;105:474–486. doi: 10.1152/jn.00642.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.