Abstract

In retinas where Müller glia have been stimulated to become progenitor cells, reactive microglia are always present. Thus, we investigated how the activation or ablation of microglia/macrophage influences the formation of Müller glia-derived progenitor cells (MGPCs) in the retina in vivo. Intraocular injections of the Interleukin-6 (IL6) stimulated the reactivity of microglia/macrophage, whereas other types of retinal glia appear largely unaffected. In acutely damaged retinas where all of the retinal microglia/macrophage were ablated, the formation of proliferating MGPCs was greatly diminished. With the microglia ablated in damaged retinas, levels of Notch and related genes were unchanged or increased, whereas levels of ascl1a, TNFα, IL1β, complement component 3 (C3) and C3a receptor were significantly reduced. In the absence of retinal damage, the combination of insulin and Fibroblast Growth Factor 2 (FGF2) failed to stimulate the formation of MGPCs when the microglia/macrophage were ablated. In addition, intraocular injections of IL6 and FGF2 stimulated the formation of MGPCs in the absence of retinal damage, and this generation of MGPCs was blocked when the microglia/macrophage were absent. We conclude that the activation of microglia and/or infiltrating macrophage contributes to the formation of proliferating MGPCs, and these effects may be mediated by components of the complement system and inflammatory cytokines.

Keywords: Müller glia, microglia, retina, cellular proliferation, regeneration

Introduction

The retinas of vertebrates contain different types of glial cells. Across all vertebrate species, retinal glia include Müller glia derived from neuroepithelial stem cells and microglia/macrophage derived from mesenchymal stem cells. With some variability between species, retinal glia can include astrocytes and oligodendrocytes. Although vascular retinas contain significant numbers of astrocytes, that are closely associated with the blood vessels (Dorrell and Friedlander 2006; Friedlander et al. 2007), the avascular retinas of guinea pigs, rabbits and birds do not contain conventional types of astrocytes (Fischer and Bongini 2010; Fischer et al. 2010; Fujita et al. 2001; Won et al. 2000). Additionally, the chick retina contains an atypical glial cell that was termed the Non-astrocytic Inner Retinal Glial (NIRG) cell (Fischer et al. 2010). Rompani and Cepko described optic stalk-derived “diacytes” and astrocyte-like cells in the embryonic chick retina that are likely to be the NIRG cells that we have described (Rompani and Cepko 2010). The interactions between different types of retinal glia remains poorly understood, and the possibility that glial interactions influence the ability of Müller glia to become progenitor cells to regenerate neurons remains unknown.

Müller glia have been identified as a source of neural stem cells that are capable of regenerating retinal neurons (Fischer and Bongini 2010; Gallina et al. 2013; Karl and Reh 2010; Karl and Reh 2012). The Müller glia-derived progenitor cells (MGPCs) in the fish retina effectively regenerate functional neurons, whereas the MGPCs in birds and mammals have a limited capacity for neurogenesis (Gallina et al. 2013; Lamba et al. 2008; Lenkowski and Raymond 2014). In chick retina, the Müller glia that become progenitor-like cells re-enter the cell cycle to proliferate, down-regulate expression of the glial markers, and express elevated levels of the progenitor-markers such as Notch1, Hes5, Rx, Pax6, Egr1, Chx10, Six3, ascl1a and nestin/transitin (Fischer 2005; Fischer and Omar 2005; Gallina et al. 2013; Ghai et al. 2010; Hayes et al. 2007). The signals that stimulate Müller glia to become progenitors are slowly being revealed. Studies have indicated that MAPK-, Notch-, Jak/Stat- and Wnt-signaling influence the formation of MGPCs in the retinas of zebrafish, birds and rodents (reviewed by Fischer and Bongini 2010; Gallina et al. 2013). There are hints in the literature that the formation of MGPCs could be influenced by reactive microglia/macrophage. Studies have indicated coordinated interactions between the Müller glia and retinal microglia/macrophage in response to retinal damage. For example, murine Müller glia exposed to activated microglia/macrophage have altered cell morphology and gene expression compared to Müller glia undergoing gliosis (Wang et al. 2011). Activated microglia influence Müller glia directly and exchange pro-inflammatory and chemotactic cytokines that mediate glial activity in damaged retina (Wang et al. 2011). Negishi and Shinagawa reported that injections of Interleukin 6 (IL6) into the goldfish eye stimulated the accumulation of PCNA-positive “rod progenitors” and possibly microglia (Negishi and Shinagawa 1993). Since recent studies have indicated that Müller glia give rise to rod progenitors in the fish retina (Bernardos et al. 2007), the work from Negishi and Shinagawa implies that IL6-mediated activation of microglia may secondarily enhance neurogenesis from MGPCs. A recent study in salamanders has demonstrated that systemic macrophage depletion results in a failure of limb regeneration, and that the capacity of limb regeneration can be restored by re-amputation once endogenous macrophage are re-populated (Godwin et al. 2013). In this study we examine whether activation or ablation of microglia/macrophage in the retina influences the formation of MGPCs in vivo.

Materials and methods

Animals

The use of animals in these experiments was in accordance with the guidelines established by the National Institutes of Health and the Ohio State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Newly hatched leghorn chickens (Gallus gallus domesticus) were obtained from the Department of Animal Sciences at the Ohio State University and kept on a cycle of 12 hours light, 12 hours dark (lights on at 7:00 am). Chicks were housed in a brooder at about 25°C and received water and Purinatm chick starter ad libitum.

Preparation of clodronate-liposomes

The preparation of clodronate-liposomes was based on previous descriptions (Van Rooijen 1989; van Rooijen 1992; Van Rooijen and Sanders 1994) and has been described in a recent publication (Zelinka et al. 2012). Approximately 1% of the clodronate is encapsulated by the liposomes (Van Rooijen and Sanders 1994), yielding approximately 7.85 mg/ml. Precise quantitation of the clodronate was difficult, because of the stochastic nature of combination of the clodronate and liposomes. Accordingly, we adjusted doses to levels where >99% of the microglia/macrophage were ablated at 1 day after treatment.

Intraocular injections

Chickens were anesthetized and intraocular injections were performed as described previously (Fischer et al. 1998a; Fischer et al. 1998b). Compounds used in these studies included recombinant human Interleukin-6 (IL6; 100 or 200ng/dose; R&D Systems), purified bovine insulin (1μg/dose; Sigma-Aldrich), recombinant human Fibroblast Growth Factor 2 (FGF2; 200ng/dose; R&D Systems), N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA; 38.5 or 154 μg/dose; Sigma-Aldrich), clodronate-liposomes (500 to 2000 ng). One μg of 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) was injected to label proliferating cells. Injection paradigms are included in the figures.

Tissue dissection, fixation, sectioning and immunolabeling

Tissues were fixed, sectioned and immunolabeled as described previously (Fischer et al. 2008; Fischer et al. 1998a; Fischer et al. 2006). Working dilutions and sources of antibodies are included as supplemental information (Table 1). Secondary antibodies included the appropriate species-specific anti-IgG-Alexafluor (Invitrogen) diluted to 1:1000 in phosphate buffed saline (PBS) plus 0.2% Triton X-100. DRAQ5 (Biostatus) was diluted to 5 μM in the secondary antibody solution to fluorescently stain nuclear DNA.

Table 1.

Antibodies, sources and working dilutions.

| Antigen | Working dilution |

Host | Clone or catalog number |

Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sox9 | 1:2500 | rabbit | AB5535 | Millipore Billerica, MA |

| Sox2 | 1:1000 | goat | Y-17 | Santa Cruz Immunochemicals |

| transitin | 1:80 | mouse | EAP3 | Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB) Iowa City, IA |

| TopAP | 1:100 | mouse | 2M6 | Dr. P. Linser University of Florida |

| Nkx2.2 | 1:80 | mouse | 74.5A5 | DSHB |

| Pax6 | 1:50 | mouse | PAX6 | DSHB |

| CD45 | 1:200 | mouse | HIS-C7 | Cedi Diagnostic |

| Lysosom al membrane glycoprotein |

1:100 | mouse | LEP100 | DSHB |

| p38 MAPK |

1:400 | rabbit | 12F8 | Cell Signaling Technologies |

| pERK1/2 | 1:200 | rabbit | 137F5 | Cell Signaling Technologies |

| cFos | 1:400 | rabbit | K-25 | Santa Cruz Immunochemicals |

| Egr1 | 1:1000 | goat | AF2818 | R&D Systems |

| pCREB | 1:500 | rabbit | Cell Signaling Technologies | |

| PCNA | 1:1000 | mouse | M0879 | Dako Immunochemicals Carpinteria, CA |

| BrdU | 1:200 | rat | OBT0003 0S |

AbD Serotec Raleigh, NC |

| BrdU | 1:100 | mouse | G3G4 | DSHB |

Reverse transcriptase PCR and Quantitative PCR

Reverse transcriptase and PCR reactions were performed as described previously (Fischer et al. 2004; Fischer et al. 2010; Ghai et al. 2010). PCR primers were designed by using the Primer-BLAST primer design tool at NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/). Forward and reverse primer sequences (5’ – 3’) and predicted product sizes are included as supplemental information (Table 2). PCR reactions were performed by using standard protocols, Platinumtm Taq (Invitrogen) or TITANIUMtm Taq (Clontech) and an Eppendorf thermal cycler. For qPCR, reactions were performed using SYBRtm Green Master Mix and StepOnePlus Real-Time system (Applied BioSystems). Samples were run in triplicate on at least 3 different samples. Ct values obtained from real-time PCR were normalized to GAPDH for each sample and the fold change between control and treated samples was determined using the 2-ΔΔCt method (=Fold Change 2(−ΔΔCt) ) and represented as a percentage change from the control. Significance of difference for percent change was determined by using a non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test.

Table 2.

Primer sequences and predicted product sizes

| Gene | Forward primer 5’-3’ | Reverse primer 5’-3’ | Product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RT-PCR | |||

| IL6 | CGA GGA GAA ATG CCT GAC GA | TCT GGC TGC TGG ACA TTT TCT |

647 |

| IL6Rα | ATG TGC TCT GCG AGT GGC GG | CCC CCA GGC TGG ATC CCC AT |

1099 |

| C3 | ACG CTC CTG TCA TCC ACA AG | TTT TCT TCA GCG CAG CAC AC |

1177 |

| C3aR1 | TGC CTC CTC GTG ATG AAA CC | CTG TTG GCA TAT GCG AGT GC |

854 |

| GAPDH | CAT CCA AGG AGT GAG CCA AG | TGG AGG AAG AAA TTG GAG GA |

161 |

| quantitative RT- PCR |

|||

| IL6 | TTA GTT CGG GCA CAA TCC TC | GGT TCC TGA AAC GGA ACA AC |

72 |

| IL6Rα | AAA GAT GTG CTC TGC GAG TG | AAC CTG CGC TTC ATC CAT AG |

80 |

| IL1β | GCA TCA AGG GCT ACA AGC TC | CAG GCG GTA GAA GAT GAA GC |

131 |

| TNFα | AGC AGC GTT TGG GAG TGG GC | GCA GAT GGG GCA GGA AAG CCA |

133 |

| ADAM17 | AGC GAG TGC CCT CCT CCT GG | TTG CAG GCA CAC GAG CGG AG |

125 |

| cNotch1 | GGC TGG TTA TCA TGG AGT TA | CAT CCA CAT TGA TCT CAC AG | 154 |

| cDelta1 | CAC TGA CAA CCC TGA TGG TG | TGG CAC TGG CAT ATG TAG GA |

152 |

| cDll4 | GGT CTG CAG CGA GAA CTA CT | TGC AGT ATC CAT TCT GTT CG | 181 |

| cJag1 | TGA TAA GTG CAT TCC ACA CC | CAG GTA CCA CCA TTC AAA CA |

149 |

| cHes1 | CGC TGA AGA AGG ATA GTT CG | GTC ACT TCG TTC ATG CAC TC | 175 |

| cHes5 | GGA GAA GGA GTT CCA GAG AC | AAT TGC AGA GCT TCT TTG AG | 143 |

| C3 | TCC CCC ATG AGG AAT GGG AT | ATA GTC CAT GTC CCC AGG CT |

74 |

| C3aR | CACT CGC ATA TGC CAA CAG C | GCC TTT GCT CTG AAG TCC CT |

73 |

| GAPDH | CAT CCA AGG AGT GAG CCA AG | TGG AGG AAG AAA TTG GAG GA |

161 |

Microscopy, quantitative immunofluorescence, and statistics

Wide-field photomicrographs were obtained by using a Leica DM5000B microscope and Leica DC500 digital camera. Confocal images were obtained by using a Zeiss LSM510. Images were optimized for color, brightness and contrast, multiple-channel images overlaid, and figures constructed by using Adobe Photoshop™6.0. Cell counts were made from at least 5 different animals, and means and standard deviations calculated on data sets. To avoid the possibility of region-specific differences within the retina, cell counts were consistently made from the same region of retina for each data set.

Similar to previous studies (Fischer et al. 2009a; Fischer et al. 2009b; Fischer et al. 2010; Ghai et al. 2009), immunofluorescence was quantified by using ImagePro 6.2 (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD, USA). Measurements were made for regions containing pixels with intensity values of 68 or greater (0 = black and 255 = saturated); a threshold that included labeling in the Müller glia. The density sum was calculated as the total of pixel values for all pixels within threshold regions from ≥5 different retinas for each experimental condition. For measurements of levels of Pax6 in the nuclei of Müller glia, single optical sections of confocal stacks were obtained using microscope identical settings from control and treated retinas. Regions of interest (Müller glial nuclei) were selected base on overlap of Sox2 (red channel) and Sox9 (blue channel) in the INL or ONL. Measurements were made for regions containing pixels with intensity values of 15 or greater (0 = black and 255 = saturated). The mean pixel values in the green channel were calculated for all pixels within threshold regions from 5 different retinas for each experimental condition.

GraphPad Prism 6 was used for statistical analyses. Each data-set represents one occasion and the statistical analyses did not involve repeated measures designs Significance of difference between control and treatment groups was determined using a two-tailed, unpaired t-test. Significance of difference was determined between two treatment groups, accounting for inter-individual variability (tr-cntrl), was determined using a two-tailed, paired t-test. Significance of difference was assessed between multiple experimental groups by using ANOVA and post-hoc t-tests with Sidak-Bonferroni correction. To test for unequal variances we used a Levene’s test. For data sets with unequal variances, we performed a Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric ANOVA.

Results

Reactive glia, IL6 and IL6 receptors are dynamically regulated in damaged retinas

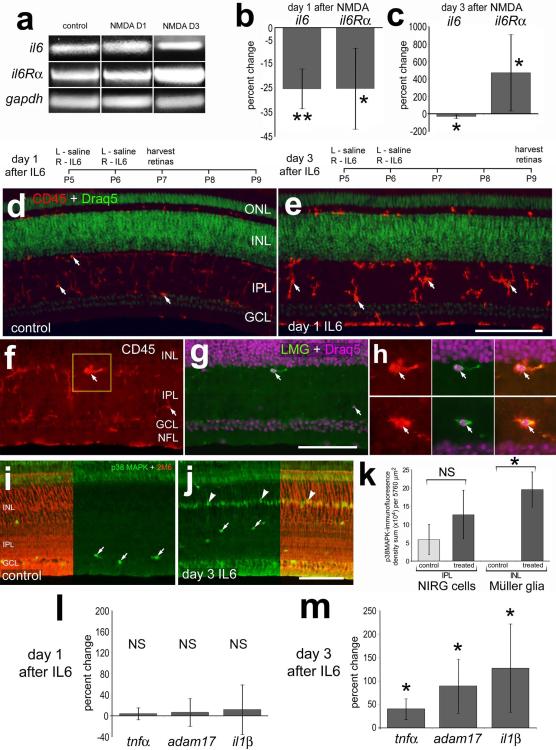

To understand how IL6 might influence glia in the retina, we examined the expression of IL6 and IL6 receptors in normal and NMDA-damaged retinas. In retinas damaged by NMDA, microglia/macrophage are known to transiently become reactive and accumulate (Fischer et al. 1998a; Zelinka et al. 2012), and Müller glia are known to de-differentiate, proliferate and become progenitor-like cells (Fischer and Reh 2001). We detected IL6 and IL6 receptor-alpha (IL6Rα) mRNAs in normal and NMDA-damaged retinas at 1 and 3 days after damage (Fig. 1a). There were small, but significant, decreases in levels of IL6 and IL6Rα at 1 day after NMDA-treatment (Fig. 1b). By comparison, at 3 days after treatment retinal levels of IL6 mRNA remained decreased, whereas levels of IL6Rα were increased by more than 4-fold (Fig. 1c).

Figure 1.

il6 and il6α-receptor are expressed in normal and NMDA-damaged retinas, and IL6 stimulates the reactivity of microglia and increase levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines. RT-PCR (a) and qRT-PCR (b,c,l,m) were used to detect il6 and il6α-receptor. Histograms in b and c illustrate the mean (±SD; n≥4) percentage change of il6 and il6α-receptor at day 1 (b) and day 3 (c) after treatment with 2 μmol NMDA. (d-m) Retinas were obtained from eyes 1 or 3 days after the last of 2 consecutive daily injections of IL6 or saline (control). Retinal sections were labeled with DRAQ5 (green in d and e; magenta in g and h) and antibodies to CD45 (red; d-f and h), LMG (green; g and h), p38 MAPK (green; i and j), or TopAP (2M6; red; i and j). Arrows indicate microglia (d-h) or presumptive NIRG cells (i and j), and arrow-heads indicate the nuclei of Müller glia (j). The scale bar (50 μm) in panel e applies to d and e, the bar in g applies f and g, and the bar in j applies to i and j. The histogram in k illustrates the mean (±SD; n=5) density sum for p38 MAPK-immunofluorescence above threshold in the IPL or INL at 3 days after IL6-treatment. Histograms in l and m illustrate the mean (±SD; n=4) percentage change of il1β, adam17 and tnfα at day 1 and day 3 after treatment with IL6. Significance of difference (**p<0.01, *p<0.05, NS – not significant) was determined by using a Mann-Whitney U test. Abbreviations: ONL – outer nuclear layer, INL – inner nuclear layer, IPL – inner plexiform layer, GCL – ganglion cell layer, NFL – nerve fiber layer, gapdh - Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase, NMDA – N-methyl-D-aspartate.

We next applied intraocular injections of IL6 to examine whether Müller glia, microglia and/or infiltrating macrophage are influenced by a pro-inflammatory cytokine. Studies have demonstrated that IL6 stimulates microglia/macrophage reactivity in the CNS (Maccioni et al. 2009; Ransohoff et al. 2007; Tuttolomondo et al. 2008). We examined the effects of sustained exposure to IL6 on retinal glia. Twenty-four hours after the last of 2 consecutive daily injections of IL6, we found that microglia/macrophage were reactive with an up-regulation of CD45 and amoeboid morphology; fine peripheral processes were retracted and somata appeared to round-up (Fig. 1d and 1e). Hereafter we use the term “reactive microglia” to collectively refer to reactive microglia and/or infiltrating macrophage; these monocytes cannot be distinguished based upon elevated levels of CD45 and amoeboid morphology. Reactive CD45+ microglia were always (n=96 cells) immunoreactive for lysosomal membrane glycoprotein (LMG; Figs. 1f-h). LMG was never observed in Müller glia in any treatment paradigm, consistent with the hypothesis that Müller glia are not phagocytic in the chick retina. At 3 days after IL6-treatment, the microglia appeared to remain reactive (not shown), consistent with a report demonstrating that retinal microglia are transiently reactive for 7 days following an acute injury or treatment with IGF1 (Zelinka et al. 2012). The Müller glia and NIRG cells appeared unaffected 1 day after IL6-treatment. There were no IL6-induced accumulations of pERK1/2, pCREB, p38 MAPK, cFos, Egr1, transitin or GFAP in the Müller glia or NIRG cells (data not shown); markers that are up-regulated by stimulated Müller glia (Fischer et al. 2009a; Fischer et al. 2009b; Fischer et al. 2010; Ghai et al. 2010). At 3 days after treatment with IL6, we observed a significant accumulation of p38 MAPK in TopAP-positive Müller glia in the INL, while the levels of p38 MAPK in NIRG cells in the IPL were unaffected (Figs. 1i-k). TopAP is a member of the sarcolemmal membrane-associated proteins that is known to be expressed by Müller glia (Ochrietor et al. 2010). At 3 days after IL6-treatment there were no detectable changes in glial expression of pERK1/2, pCREB, cFos, Egr1 or GFAP (data not shown). At 24 hours after 2 consecutive daily injections of IL6, levels of IL1β, Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNFα) and the TNFα-processing enzyme ADAM17 were unchanged (Fig. 1l). At 3 days after the last injection of IL6, there were significant increases in levels of TNFα, ADAM17 and IL1β (Fig. 1m).

Clodronate-liposomes do not affect Müller glia in normal or damaged retinas

We investigated whether the ablation of microglia with DiI-labeled clodronate-liposomes effectively ablates the microglia without directly influencing the Müller glia. Application of clodronate-liposomes is a well-established method to selectively ablate phagocytic cells (Van Rooijen 1989; van Rooijen 1992; Van Rooijen and Sanders 1994). In the chick retina, the combination of IL6 and clodronate-liposomes destroys >99% of the RCA1/CD45-positive microglia (Zelinka et al. 2012). The microglia/macrophage do not begin to repopulate the retina until 26 days after treatment, with no detectable effects upon retinal neurons, whereas the NIRG cells perish within 7 days after treatment (Zelinka et al. 2012). Application of clodronate-liposomes alone has been shown to result in the hyper-activation of reactive microglia (Zelinka et al. 2012). Therefore, liposomes were not used as the negative control. At 4 hrs after treatment, the majority of the liposomes where observed as distinct puncta at the vitread surface of the retina, whereas aggregates of liposomes where observed within the IPL associated with or engulfed by CD45-positive microglia (Figs. 2a). At one day after treatment, the majority of the DiI was observed in structures within the IPL, there was a massive depletion of CD45-positive microglia, and no effect upon numbers of Müller glia (Figs. 2b,n). The DiI-labeled, CD45-negative structures in the IPL were likely to be remnants of dying microglia. By 2 days after treatment, there was a complete ablation of microglia across all regions of the retina, including the periphery and the circumferential marginal zone (Figs. 2d-h). This ablation was highly reproducible (n>50) and resulted in a near-complete loss of CD45-immunofluorescence within the retina; the remaining CD45-immunoreactivity appeared to be cell fragments (Fig. 2h). At 5 days after IL6/clodronate-treatment, before the application of NMDA, we found persistent liposomes at the vitread surface of retina, no clusters or aggregates of liposomes within the retina, a complete absence of microglia, and no effect upon numbers of Müller glia (Figs. 2c,l,n). In retinas at 7 days after IL6/clodronate-treatment, 2 days after NMDA-treatment when the MGPCs begin to enter S-phase of the cell cycle (Fischer and Reh 2001), we found persistent liposomes at the vitread surface of retina, no liposomes accumulated with the retina, and no effect upon numbers of Müller glia (Figs. 2i,j,m,n). These data indicate that the clodronate-liposomes are not phagocytized by Müller glia and that the liposomes do not directly influence the Müller glia or MGPCs in normal or damaged retinas.

Figure 2.

Müller glia in normal and damaged retinas are not affected by and do not accumulate DiI-labeled clodronate-liposomes. IL6±clodronate/DiI-liposomes were injected into eyes and retinas harvested at 4hrs, 1, 2, or 5 days later. Alternatively, eyes were injected with NMDA at day 5 and retinas harvested at day 7. Retinal sections were labeled with DRAQ5 (magenta; a), and antibodies to CD45 (green or grayscale; a-i), Sox9 (magenta; j) Sox2 (red; k-m) or transitin (green; j-m). The DiI-labeled liposomes appear as red puncta (a-j). Arrows indicate DiI-liposomes, small double-arrows indicate microglia, and hollow arrow-heads indicate the nuclei of Müller glia. The areas boxed-out (yellow) in panels a-c, i and j are enlarged 2.5-fold in the adjacent panels. The histogram in n illustrated the mean (±SD; n=5) number of Müller glia at 1, 5 and 7 days after treatment. ANOVA indicated no significant difference. The scale bar (50 μm) in panel a applies to a alone, the bar in f applies to e and f, the bar in i applies to b,c,i and j, and the bar in m applies to k-m. Abbreviations: ONL – outer nuclear layer, INL – inner nuclear layer, IPL – inner plexiform layer, GCL – ganglion cell layer, NFL – nerve fiber layer.

Reactive microglia facilitate the formation of proliferating MGPCs in damaged retinas

Within NMDA-damaged retinas pre-treated with IL6 alone, there was a dramatic accumulation of reactive microglia (Figs. 3a). In retinas treated with IL6/clodronate-liposomes and NMDA, there was a complete loss of CD45-positive cells from the retina (Fig. 3b). With the microglia completely ablated and Sox9/Nkx2.2-positive NIRG cells significantly depleted (Figs. 3c-e), we found significant (≥ 70%) decreases in the number of proliferating MGPCs in both central and peripheral regions of the retina (Figs. 3f-j). The Sox2-positive nuclei of Müller glia in the middle of the INL in retinas treated with IL6/clodronate before NMDA remained laminated unlike the Sox2-positive nuclei of Müller glia in the INL of control retinas (Figs. 3f-i), suggesting that progenitors were not generated. The nuclei of proliferating MGPCs are known to delaminate and migrate away from the center of the INL (Fischer 2005; Fischer and Bongini 2010; Fischer and Reh 2001). The NIRG cells that survived treatment with IL6/clodronate failed to proliferate and failed to recover in numbers in damaged retinas in the absence of microglia (Fig. 3k).

Figure 3.

Ablation of the microglia and NIRG cells reduces the number of proliferating MGPCs in NMDA-damaged retinas. Eyes were injected with IL6 alone (control) or IL6 and clodronate-liposomes (treated) at P5, NMDA at P10, BrdU at P12, and retinas harvested at P13. Retinal sections were labeled with DRAQ5 (red; a and b) and antibodies to CD45 (green; a and b), Nkx2.2 (red; c and d), Sox9 (green; c and d), Sox2 (red; f-i) and BrdU (green; f-i). Images of the retina were obtained from central (a-d, f and g) and peripheral (h and i) regions. Arrows indicate Sox9+ Sox2+ Nkx2.2+ NIRG cells (c, d and f-i), arrow-heads indicate Sox2+ Sox9+ Nkx2.2− nuclei of Müller glia (c, d and f-i), and small double-arrows indicate BrdU+/Sox2 negative cells that are proliferating microglia (f and h). The scale bar (50 μm) in panel i applies to a-d and f-i. e, j,k; mean (±SD; n≥9) number of BrdU-positive Müller glia and NIRG cells in central and peripheral regions of control and treated retinas. Significance of difference (*p<0.01, **p<0.0001) was determined by using an unpaired, two-tailed t-test. Abbreviations: ONL – outer nuclear layer, INL – inner nuclear layer, IPL – inner plexiform layer, GCL – ganglion cell layer, RPE – retinal pigmented epithelium.

To better understand why few MGPCs formed in the absence of microglia in damaged retinas, we probed for changes in retinal levels of notch1 and Notch-related genes, bHLH transcription factors and pro-inflammatory cytokines by using qRT-PCR. We confirmed changes in microglia in damaged retina represented by a large up-regulation of CD45 mRNA, which was dramatically reduced in damaged retinas pre-treated with clodronate-liposomes (Fig. 4a). We next examined changes in expression of notch1 and Notch-related genes as read-outs of Notch-signaling. Retinal levels of notch1, delta1, dll4 and hes5 were elevated, whereas levels of jagged and hes1 were unchanged, in NMDA-damaged retinas (Fig. 4a). In NMDA-damaged retinas where the microglia were ablated, levels of notch1, delta1, jagged and hes1 were unaffected, whereas levels of hes5 were significantly decreased, and levels of dll4 were further increased (Fig. 4a). Levels of the proneural bHLH transcription factor ascl1a, which are increased in NMDA-damaged retinas (Fig. 4a), were significantly reduced in damaged retinas with depleted microglia (Fig. 4a). Similarly, there were large, significant reductions in the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNFα and IL1β, whereas levels of IL6 were modestly increased, in damaged retinas where the microglia were depleted (Fig. 4a).

Figure 4.

The ablation of the microglia and NIRG cells influences retinal levels of ascl1a, inflammatory cytokines and component of the complement system. qRT-PCR (a and c) and RT-PCR (b) were used to detect retinal mRNA for cd45, Notch-related genes, bHLH transcription factors, inflammatory cytokines and components of the complement system. cDNA or retinal sections were generated from individual retinas (n≥4) that were treated with IL6 alone (control) or IL6+clodronate-liposomes (treated) at P5, NMDA at P10 and harvested at P13. Significance of difference (*p<0.05) was determined by using a Mann-Whitney U test. Retinal sections were immunolabeled and confocal microscopy was used to detect Pax6 (green), Sox2 (red), and Sox9 (blue) in retinas treated with IL6/NMDA (d and e) or IL6/clodronate/NMDA (f and g). Arrows indicate the nuclei of Müller glia and/or MGPCs. The scale bar (50 μm) in panel g applies to d-g. The histogram in h illustrates the mean (±SD; n=9) pixel value for the green channel (Pax6) within the nuclei of Sox2/Sox9-positive Müller glia in the INL and ONL. Significance of difference (NS, p>0.05) was calculated by using an unpaired, two-tailed t-test. Abbreviations: INL – inner nuclear layer, RT – reverse transcriptase, bHLH – basic helix-loop-helix, gapdh - Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase, NMDA – N-methyl-D-aspartate.

We next examined whether components of the complement system were influenced in NMDA-damaged retinas with or without reactive microglia. The complement system is known to have diverse important functions in addition to regulation of the immune system. These functions include regulation of neurogenesis (Rahpeymai et al. 2006), stem cell maintenance, cell proliferation and cell survival (Molnar et al. 2008; Sacks et al. 2009). A recent study in the embryonic chick demonstrated that the complement peptide C3a and the C3a Receptor (C3aR) stimulate retinal regeneration during early stages of development (Haynes et al. 2013). We found that levels of C3 and C3aR were elevated in NMDA-damaged retinas at 3 days after treatment (Fig. 4b,c). By comparison, levels of C3 and C3aR were significantly reduced in NMDA-damaged retinas when the microglia were depleted (Figs. 4b,c).

We next examined whether the expression of Pax6 in Müller glia and MGPCs was affected by the absence of reactive microglia in NMDA-damaged retinas. Pax6 is not expressed, or is expressed at low levels, in normal Müller glia in the chick retina (see Fig. 9), but is known to be important for normal eye development and the formation of MGPCs in zebrafish retina (Thummel et al. 2010). Pax6 is noticeably up-regulated in proliferating MGPCs in NMDA-damaged retinas (Fig. 4d,e). In NMDA-damaged retinas with depleted microglia, Pax6 was detectable in the nuclei of Müller glia and was not significantly from the levels seen in the nuclei of Müller glia in NMDA-damaged retinas that contained reactive microglia (Figs. 4f-h). Activation of FGF-receptors and MAPK-signaling are needed for the formation of MGPCs (Fischer et al. 2009b). However, there were no detectable changes in pERK1/2, pCREB, cFos or Egr1 in Müller glia at 1 day after NMDA-treatment in retinas with ablated microglia (data not shown)

Figure 9.

MAPK-signaling and Pax6 expression in Müller glia is stimulated by FGF2 with and without the microglia. Eyes were uninjected (a; pERK1/2 control) or injected with IL6 alone (control) or IL6+clodronate (treated) at P9, FGF2 + BrdU at P11, P12, P13 and P14, and retinas were harvested at P15. Retinal sections were immunolabeled for Sox2 (red) and pERK1/2 (green; a-c), cFos (green; d,e), p38 MAPK (green; f.g), Pax6 (green; i-l) and Sox9 (blue; i-l). The retinas in i and j were obtained from eyes that received consecutive daily injections of saline or FGF2 from P6-P9, followed by an additional injection of BrdU in saline at P10, and tissues harvested at P12 (see the treatment paradigm for Fig. 8). Hollow arrow-heads indicate the nuclei of Müller glia. The scale bar (50 μm) in panel g applies to a-g, and the bar in l applies to i-l. The histograms in panel h illustrates the mean (±SD) area sum, intensity mean and density sum for p38 MAPK-immunofluorescence above threshold in the INL. To account for inter-individual variability we calculated the difference (tr-ctrl) between treated (IL6 + clodronate + FGF2) and control (IL6 + FGF2) retinas for each individual (n=5). Significance of difference (*p<0.05, **p<0.001) was determined by using a paired t-test.

Reactive microglia are required for the formation of proliferating MGPCs in retinas treated with insulin and FGF2

Müller glia are known to become proliferating progenitor-like cells in the absence of retinal damage when treated with 3 consecutive daily intraocular injections of insulin and FGF2 (Fischer et al. 2002). Injections of insulin are known to stimulate the reactivity of microglia, whereas FGF2 activates MAPK-signaling in the Müller glia (Fischer et al. 2009a). Accordingly, we tested whether the ablation of microglia/NIRG cells influenced the ability of Müller glia to become MGPCs in retinas treated with insulin and FGF2. We found a complete ablation of microglia, and a near complete ablation of NIRG cells, in retinas treated with IL6/clodronate/insulin/FGF2 (Figs. 5a-d,n,o). In retinas treated with IL6/clodronate/insulin/FGF2 the nuclei of Müller glia remained tightly laminated near the center of the INL, unlike the nuclei of Müller glia in retinas treated with IL6/insulin/FGF2 where these nuclei delaminated (Figs. 5c,d). In retinas where the microglia were ablated the Müller glia failed to form proliferating MGPCs in response to insulin and FGF2 (Figs. 5e-m). Intraocular injections of insulin and FGF2 in clodronate-treated retinas failed to restore numbers of microglia and NIRG cells by stimulating proliferation or infiltration from extra-retinal sources (Figs. 5n,o).

Figure 5.

The ablation of the microglia and NIRG cells prevents the proliferation of MGPCs in retinas treated with insulin and FGF2. Eyes were injected with IL6 alone (control; a, c, e-h) or IL6 and clodronate-liposomes (treated; b, d, i-l) at P17, the combination of BrdU, insulin and FGF2 at P20-P22, BrdU at P23, and retinas harvested at P24. Retinal sections were immunolabeled for CD45 (a,b), Sox9 (red) and transitin (green; c,d), and Sox2, PCNA and BrdU (e-l). Arrows indicate the nuclei of Müller glia and hollow arrow-heads indicate the nuclei of NIRG cells. The scale bar (50 μm) in panel d applies to a-d, and the bar in l applies to e-l. The histograms in m-o illustrate the mean (±SD; n=8) numbers of proliferating Müller glia, NIRG cells and microglia in central or peripheral regions of the retina. Significance of difference (*p<0.001, **p<0.0001) between control and treated samples from different retinal regions was determined by using an unpaired, two-tailed t-test. Abbreviations: ONL – outer nuclear layer, INL – inner nuclear layer, IPL – inner plexiform layer, GCL – ganglion cell layer

IL6 and FGF2 stimulate the reactivity of microglia and the formation of MGPCs

Since insulin is known to stimulate the reactivity of microglia (Fischer et al. 2009a), in a manner similar to that of IL6 (see Fig. 1), and FGF2 directly stimulates Müller glia to become progenitors (Fischer et al. 2002; Fischer et al. 2009a; Ghai et al. 2010), we hypothesized that the combination of IL6 and FGF2 would stimulate the formation of MGPCs in the absence of damage. We found that 3 consecutive daily injections of IL6 and FGF2 had variable effects upon the formation of MGPCs; only 2 out of 5 treated retinas contained proliferating MGPCs. Accordingly, we extended the retinal exposure to IL6 and FGF2 by applying 4 consecutive daily injections. We found that 4 consecutive daily injections of the combination of IL6 and FGF2 stimulated the formation of MGPCs in peripheral, but not central, regions of the retina (Figs. 6a-e,h). Interestingly, the majority (10 out of 12) of FGF2-treated retinas contained significant numbers of MGPCs in peripheral regions of the retina (Fig. 6h). All of the retinas treated with FGF2 (n=12) or treated with FGF2+IL6 (n=12) contained Müller glia with delaminated nuclei in central and peripheral regions of the retina (Figs. 6b,d). In retinas treated with saline or IL6 alone we found relatively few proliferating NIRG cells, whereas increased numbers of proliferating NIRG cells were found in retinas treated with FGF2 alone in central, not peripheral, regions of the retina (Figs. 6a-d,f and i). The FGF2-treated NIRG cells were not reactive; there was no up-regulation of transitin and these cells did not migrate distally into the retina (data not shown). In all retinas treated with the combination IL6 and FGF2 there were increased numbers of Sox9/Nkx2.2-positve NIRG cells that had migrated distally into the INL, and many of these cells were BrdU-positive (Figs. 6b,i). Numbers of proliferating microglia were unaffected by the different treatments, with the exception of the combination of IL6 and FGF2 which significantly increased numbers BrdU+ microglia in peripheral regions of the retina (Figs. 6g, j). We found no evidence of cell death (fragmented DNA) in retinas treated with IL6 alone, FGF2 or the combination of IL6 and FGF2 (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Four consecutive daily injections of FGF2 alone or the combination of IL6 and FGF2 stimulate the formation of proliferating MGPCs. Eyes were injected with BrdU/saline (control), FGF2 alone, IL6 alone or the combination of IL6 and FGF2 at P6, P7, P8 and P9, BrdU in saline at P10, and retinas harvested at P12. Micrographs of peripheral regions of retinas were obtained from eyes injected with IL6 alone (a,c) or the combination of IL6 and FGF2 (b,d). Retinal sections were immunolabeled for Nkx2.2 and Sox9 (a,b) and BrdU and Sox2 (c,d). Arrows indicate NIRG cells (Nkx2.2+ Sox2+ nuclei), small double arrow indicate proliferating microglia (BrdU alone), and hollow arrow-heads indicate proliferating Müller glia (BrdU+ Sox2+ Nkx2.2− nuclei). The calibration bar (50 μm) in d applies to a-d. The histograms in e-j illustrate the mean (+SD; n≥6) number of proliferating Müller glia, NIRG cells and microglia for the different treatment paradigms in central and peripheral regions of the reitna. Significance of difference (p<0.0001) among experimental groups was determined by using ANOVA. Significance of difference (*p<0.02, **p<0.001, ***p<0.0001) between control and the different treatment groups was determined by using post-hoc Sidak-Bonferroni corrected t-tests. Abbreviations: ONL – outer nuclear layer, INL – inner nuclear layer, IPL – inner plexiform layer, GCL – ganglion cell layer.

The reactivity of microglia is stimulated by puncturing the eye and by injection of IL6 and/or FGF2

Since FGF2±IL6 stimulated the formation of MGPCs, we tested how the different injection paradigms and merely puncturing the eye influence the reactivity of the microglia. We hypothesized that intraocular injections alone were sufficient to activate microglial reactivity and provide stimuli to permit FGF2-induced formation of MGPCs. We found that merely puncturing the eye without injection significantly increased the reactivity of the microglia and expression of CD45 (Figs. 7a,b,g). Compared to the retinal microglia from uninjected eyes, the microglia from eyes that were injected with saline/BrdU were more reactive, with significant increases in levels of CD45-immunofluorescence (Figs. 7a-c, g). Similarly, the microglia treated with IL6 alone, FGF2 alone, or the combination of IL6 and FGF2 appeared to be more reactive, and had significant increases in CD45 compared to the microglia treated with saline/BrdU (Figs. 7c-g). Levels of CD45 were significantly less in retinas treated with IL6 and FGF2 compared to retinas treated with IL6 alone (Fig. 7g).

Figure 7.

Microglial reactivity is stimulated by ocular punctures and injections of saline, and reactivity further increased by FGF2 and IL6. Retinal sections (immunolabeled for CD45) were obtained from eyes that were uninjected (a), or from eyes that were punctured but not injected (b), injected with saline/BrdU (c), FGF2 alone (d), IL6 alone (e), or the combination of IL6 and FGF2 (f). The scale bar (50 μm) in panel f applies to a-f. The histogram in g illustrates the mean (±SD; n=6) density sum for CD45-immunofluorescence above threshold. A Levene’s test indicated unequal variances and a Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric ANOVA indicated significant (p<0.0001) differences among groups and significant (*p<0.05) differences between groups. Abbreviations: ONL – outer nuclear layer, INL – inner nuclear layer, IPL – inner plexiform layer, GCL – ganglion cell layer.

Reactive microglia are required for FGF2-mediated formation of MGPCs

Since reactive microglia were prevalent in retinas treated with FGF2 alone, we tested whether the ablation of microglia influences the formation of MGPCs. The IL6/clodronate-treatment effectively ablated all microglia and most NIRG cells, and FGF2 alone provided no protection or recovery of these glial cells (Figs. 8a-d). There were no proliferating MGPCs in FGF2-treated retinas where the microglia were ablated (Figs. 8c-g). Although there was wide-spread delamination of the nuclei of Müller glia and MGPCs in central and peripheral regions of retinas treated with FGF2, this delamination of nuclei was completely absent in FGF2-treated retinas where the microglia were absent (Figs. 8c-f).

Figure 8.

Four consecutive daily injections of FGF2 alone fail to stimulate the proliferation of MGPCs when the microglia have been ablated. Eyes were injected with IL6 alone (control) or IL6+clodronate (treated) at P9, FGF2 + BrdU at P11, P12, P13 and P14, BrdU in saline at P15, and retinas were harvested at P17. Retinal sections were immunolabeled for CD45 (a,b) and BrdU (green) and Sox2 (red; c-f). Sections of the retina were obtained from central (a-d) and peripheral (e,f) regions of the retina. Small double-arrows indicate microglia, and hollow arrow-heads indicate the nuclei of Müller glia. The scale bar (50 μm) in panel f applies to a-f. The histogram in g illustrates the mean (±SD; n=9) number of proliferating Müller glia (Brdu+Sox2+ cells in the INL and ONL). Significance of difference (**p<0.0005) was determined by using an unpaired, two-tailed t-test.

We speculated that reactive microglia permitted or facilitated FGF2/MAPK-mediated signaling in Müller glia to stimulate the formation of MGPCs. Accordingly, we tested whether readouts of FGF2/MAPK-signaling are up-regulated in Müller glia when reactive microglia are absent. In response to intraocular injections of FGF2 Müller glia are known to up-regulate pERK1/2, pCREB, cFos and p38 MAPK (Fischer et al. 2009a). We found that FGF2 stimulated Müller glia to accumulate pERK1/2 (Figs. 9a-c), and pCREB (not shown) when reactive microglia are present or ablated. Compared to levels of cFos observed in control retinas, cFos was weakly induced in FGF2-treated Müller glia when reactive microglia were absent (Figs. 9d,e). By contrast, levels of p38 MAPK were significantly elevated in FGF2-treated Müller glia when reactive microglia and NIRG cells were ablated (Figs. 9f-h).

We next examined whether FGF2 retained the ability to stimulate Pax6 expression in MGPCs when microglia were absent. During eye development FGF2/MAPK-signaling is known to induce Pax6 expression in retinal stem cells and lens placode (Ashery-Padan and Gruss 2001; Shaham et al. 2012). In retinas treated with saline we found little or no expression of Pax6 in Müller glia (Fig. 9i). By comparison, we found significant expression of Pax6 in the nuclei of Müller glia or MGPCs treated with FGF2 or IL6+FGF2 (Figs. 9j,k), where proliferating MGPC were prevalent (Figs. 6d,h and 8e,g). Interestingly, levels of Pax6 were elevated in the nuclei of Müller glia in retinas treated with IL6/clodronate+FGF2 (Fig. 9l), where the microglia were depleted and MGPCs failed to form.

Discussion

Our findings indicate that activation of microglial reactivity is an important step in stimulating Müller glia to de-differentiate, proliferate and become progenitor-like. Our findings suggest that reactive microglia provide signals to stimulate some aspects progenitor phenotype and re-entry into the cell cycle. Alternatively, the reactive microglia could suppress inhibitory signals that prevent the formation of MGPCs. Reactive microglia are consistently found in retinas, acutely damaged or treated with growth factors, where Müller glia have been stimulated to become progenitor cells. In retinas damaged by NMDA, the microglia transiently accumulate and become reactive (Fischer et al. 1998a; Zelinka et al. 2012). However, in damaged retinas where the microglia and NIRG cells are ablated, the number of proliferating MGPCs is reduced by about 70%. Although this is a significant reduction, this finding suggests that there are signals in addition to those produced by reactive microglia in damaged retinas since many Müller glia become MGPCs in the absence of microglia. It remains uncertain whether suppressed microglia reactivity, instead of ablation, influences the formation of MGPCs in damaged retinas. We find that minocycline-mediated suppression of microglial reactivity in damaged retinas inhibited the formation of MGPCs. Although minocycline inhibited reactivity in undamaged retina, this drug killed the majority of microglia in damaged retinas (unpublished observations).

In undamaged retinas, the combination of insulin/IGF1 and FGF2 stimulates the formation of MGPCs, wherein insulin/IGF1 stimulates the reactivity of microglia and NIRG cells (Fischer et al. 2009a; Fischer et al. 2010) and FGF2 activates MAPK-signaling in the Müller glia (Fischer et al. 2009a; Fischer et al. 2009b). In the absence of microglia and depletion of most NIRG cells, the efficacy of insulin and FGF2, or FGF2 alone, to stimulate the formation of MGPCs is abolished. This finding suggests that reactive microglia and NIRG cells are required for the formation of MGPCs in retinas treated with insulin and FGF2, or FGF2 alone. Intraocular injections of saline or merely puncturing the eye are sufficient to stimulate the reactivity of microglia, and when FGF2 is present proliferating MGPCs are formed. Injections of FGF2 had no detectable effect upon the NIRG cells. This implies that reactive microglia, not the NIRG cells, combined with FGF2/MAPK-signaling stimulates the formation of MGPCs. Consistent with this prediction, we find proliferating MGPCs in 40% of the eyes that received 3 consecutive daily injections of IL6 and FGF2. Collectively, these findings indicate that sustained microglial reactivity is necessary and sufficient for FGF2/MAPK-signaling to stimulate the formation of MGPCs in the absence of retinal damage.

Our findings suggest that elevated expression of notch1 is not sufficient to stimulate the formation of MGPCs in damaged retinas missing reactive microglia. Müller glia maintain Notch-signaling and express notch and related genes in normal healthy retinas (Ghai et al. 2010; Hayes et al. 2007; Nelson et al. 2011; Roesch et al. 2008). In the chick retina, Notch-signaling is required for the formation of MGPCs in damaged retinas (Hayes et al. 2007), and for FGF2/MAPK-mediated formation of MGPCs (Ghai et al. 2010). Further, MAPK-signaling is known to induce notch in glia (Ghai et al. 2010; Puschmann et al. 2014). By comparison, Notch-signaling maintains retinal progenitors in a proliferating, undifferentiated state during early stages of development and promotes the differentiation of Müller glia during the end stages of retinal histogenesis (Kageyama and Ohtsuka 1999; Vetter and Moore 2001). In damaged retinas with ablated microglia and diminished numbers of proliferating MGPCs, we find that notch1 and delta1 remain elevated, dll4 is further elevated, and hes5 is decreased. Similar to levels of notch and related genes, we find that read-outs of FGF2/MAPK-signaling are not affected by the loss of reactive microglia in damaged retinas. Collectively, these findings suggest that reactive microglia/NIRG cells have little impact upon MAPK-signaling and the expression of notch1 and related genes. However, we cannot conclude that diminished proliferation of MGPCs, in damaged retinas missing microglia, occurs independent of elevated Notch-signaling because we are not able to assess the activity of this pathway in individual MGPCs.

In damaged retinas with ablated microglia, depleted NIRG cells and diminished proliferation of MGPCs we found a significant decrease in ascl1a. The bHLH transcription factor Ascl1a is known to be required during the initial stages of Müller glia-mediated retinal regeneration in zebrafish (Fausett et al. 2008). In addition, ascl1a is expressed at elevated levels by MGPCs in damaged chick retina (Fischer and Reh 2001; Hayes et al. 2007) and enhances the neurogenic capacity of MGPCs in rodent retina (Pollak et al. 2013). During neural development, Notch-signaling inhibits the expression of ascl1a in progenitor cells (reviewed by Livesey and Cepko 2001; Vetter and Moore 2001). Given that both notch1 and ascl1a are elevated in MGPCs (Fischer and Reh 2001; Ghai et al. 2010; Hayes et al. 2007), but elevated notch1 is maintained while ascl1a is diminished when microglia are depleted, our findings suggest that notch expression may not influence the expression of ascl1a in chick MGPCs. However, our data cannot exclude the possibility that diminished Notch-signaling underlies decreased ascl1a expression in MGPCs. It is worth noting that in the regenerating fish retina, Notch-signaling inhibits the expression of ascl1a and inhibits the proliferation of MGPCs (Wan et al. 2012), contrary to the roles of Notch during neural development and in the MGPCs in birds and mammals (reviewed by Gallina et al. 2013; Lenkowski and Raymond 2014). Our findings suggest that reactive microglia somehow stimulate ascl1a expression in MGPCs, and that the reduced levels of ascl1a may underlie the reduced numbers of MGPCs in damaged retinas missing reactive microglia.

Elevated Pax6 expression in Müller glia is not sufficient to drive the formation of proliferating MGPCs. Pax6 expression in Müller glia remained up-regulated in the absence of reactive microglia in retinas damaged by NMDA and with FGF2-treatment where the formation of MGPC was diminished or absent, respectively. In retinal progenitors, Notch-signaling maintains the expression of Pax6 (Marquardt 2003; Vetter and Brown 2001), thus it is not surprising that the Müller glia are Pax6-positive in damaged retinas where the microglia were absent and levels of Notch-signaling remain elevated. Our findings are consistent with the hypotheses that (1) FGF2/MAPK-signaling in Müller glia is up-stream of Pax6 expression, (2) signals derived from reactive microglia and/or NIRG cells are required in addition to elevated Pax6 to stimulate the formation of proliferating MGPCs. Our findings are reminiscent of recent findings that Müller glia in mouse retina up-regulate Pax6, but do not proliferate following light-induced injury to photoreceptors (Joly et al. 2011). We cannot exclude the possibility that progenitor-related factors other than Pax6 are not up-regulated by FGF2-treated Müller glia when reactive microglia are absent.

It is possible that inflammatory cytokines stimulate the formation of MGPCs. We find that levels of il1β and il6R were significantly elevated, whereas levels of il6 and tnfα were reduced at 3 days after NMDA-treatment. In addition, we found that il1β and tnfα are dramatically reduced, whereas il6 was increased, in NMDA-damaged retinas when the microglia and NIRG cells are ablated, where numbers of MGPCs are reduced. Thus, IL6 may not be involved in the formation of MGPCs in damaged retina. However, IL6R can be activated by ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) (Schuster et al. 2003), and levels of CNTF are increased in NMDA-damaged retinas (Fischer et al. 2004). Thus, IL6Rα may be involved in glial responses to damage, whereas IL6 likely is not. In regenerating zebrafish retina, damaged neurons have been shown to up-regulate TNFα which, in turn, stimulates the Müller glia to produce TNFα and become proliferating MGPCs (Nelson et al. 2013). In the rodent retina, Müller glia up-regulate TNFα in response to NMDA-treatment via NFκB-signaling, the glial production of TNFα renders neurons more susceptible to excitotoxic damage (Lebrun-Julien et al. 2009). We find that levels of tnfα were rapidly up-regulated following NMDA-treatment (data not shown), but decreased thereafter. In rodent retina, Müller glia express relatively low levels of il6Rα, in addition to numerous other interleukin receptors, relatively high levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as il8, and relatively low levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines including il6 and il1β (Roesch et al. 2008). However, microglia are well-known to be the primary source of IL1β, IL6 and TNFα in damaged nervous tissue (reviewed by Ramesh et al. 2013). Thus, we propose that the decreased levels of il1β likely result from depletion of microglia in NMDA-damaged retinas, whereas decreased levels of tnfα result from a combination of depleted microglia and secondary changes in Müller glial expression. The influences of IL1β and TNFα on MGPCs in the chick retina remain unknown.

In FGF2-treated retinas where the microglia have been ablated, we found that Müller glia fail to significantly up-regulate cFos, whereas p38 MAPK was significantly up-regulated. These findings suggest that signals provided by reactive microglia potentiate cFos expression and suppress p38 MAPK in FGF2-treated Müller glia. p38 MAPK-signaling has been shown to suppress pERK1/2- and Notch-mediated proliferation and self-renewal of stem cells, including hematopoietic (Schraml et al. 2009), angiogenic (Matsumoto et al. 2002) and neural stem cells (Yang et al. 2006). Activation of p38 MAPK in retinal glia is most often associated with ocular inflammation, ischemic stress or infection (Roth et al. 2003; Shamsuddin and Kumar 2011; Takeda et al. 2002). Collectively, these findings suggest that increased signaling through p38 MAPK in Müller glia acts to enhance glial reactivity and inflammatory responses, and may decrease the ability of Müller glia to become progenitor-like cells. Our data suggest that signals derived from reactive microglia suppress the p38-branch of MAPK-signaling in response to FGF.

In zebrafish and rodent model systems, intraocular injections and retina-damaging procedures have been used to study retinal regeneration from MGPCs. Therefore, it seems likely that reactive microglia are prevalent in zebrafish and rodents models of retinal regeneration. For example, in zebrafish retina, intraocular injections of HB-EGF and subsequent activation of MAPK-signaling stimulate the formation of MGPCs (Wan et al. 2012). It remains uncertain, but seems likely, that intraocular injections in zebrafish stimulate microglial reactivity, and this reactivity may contribute signals that stimulate the formation of MGPCs. A recent study by Huang and colleagues has demonstrated, in developing zebrafish, that knock-down of macrophage colony stimulating factor-1 receptor (csf-1r) delays the infiltration of microglia/macrophage into the retina, and causes abnormal neurogenesis and retinal growth (Huang et al. 2012). This study suggests that the normal developmental accumulation of retinal microglia influences ocular growth and neurogenesis. Collectively, these findings indicate that microglia/macrophage provide signals that support retinal progenitors and these signals may also increase proliferation or enhance the competence of Müller glia to form MGPCs.

Our findings are consistent with those of recent reports indicating the importance of reactive microglia or macrophage in different models of neurogenesis and regeneration. For example, limb regeneration in salamander requires the presence of reactive macrophage (Godwin et al. 2013). In acutely damaged zebrafish brain, immunosuppression of inflammation impairs neuronal regeneration and induction of inflammation, in the absence of damage, stimulates the proliferation neural progenitors (Kyritsis et al. 2012). Similarly, in the postnatal rat brain, activation of microglia increased, whereas immunosuppression of microglia decreased neurogenesis and oligodendrogenesis from forebrain neural stem cells in the subventrical zone (Shigemoto-Mogami et al. 2014). Reactive microglia and macrophage are known to influence neurogenesis from adult neural stem cells in both the hippocampus and subventricular zone in mammals (reviewed by Kohman and Rhodes 2013; Morrens et al. 2012).

Conclusions

We conclude that reactive microglia provide signals to stimulate the formation of MGPCs. Ablation of the microglia inhibits the formation of MGPCs in acutely damaged retinas and in undamaged retinas treated with growth factors. The combination of reactive microglia and FGF2/MAPK-signaling are sufficient to stimulate the formation of proliferating MGPCs in the absence of retinal damage. The loss of reactive microglia, and consequential fewer MGPCs in damaged retinas, is accompanied by large decreases in retinal levels of ascl1a, il1β, tnfα, c3 and c3aR. The identity of the signals provided by reactive microglia to stimulate the formation of MGPCs remains uncertain, but may include pro-inflammatory cytokines and components of the complement system.

Main Points.

- Reactive microglia stimulate the formation of proliferating Müller glia-derived progenitors in damaged retinas.

- Reactive microglia stimulate the formation of proliferating Müller glia-derived progenitors in FGF2-treated retinas in the absence of damage.

- The loss of microglia diminishes levels of ascl1a, components of the complement system, pro-inflammatory cytokines and enhance levels p38 MAPK coincident with diminished formation of Müller glia-derived progenitors.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Dr. Zachary Weil for kindly provided advice on statistical analyses. Confocal imaging was performed at the Hunt-Curtis Imaging Facility in the Department of Neuroscience. This work was supported by a grant (EY022030-02) from the National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health.

References

- Ashery-Padan R, Gruss P. Pax6 lights-up the way for eye development. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13(6):706–14. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00274-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardos RL, Barthel LK, Meyers JR, Raymond PA. Late-stage neuronal progenitors in the retina are radial Muller glia that function as retinal stem cells. J Neurosci. 2007;27(26):7028–40. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1624-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorrell MI, Friedlander M. Mechanisms of endothelial cell guidance and vascular patterning in the developing mouse retina. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2006;25(3):277–95. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fausett BV, Gumerson JD, Goldman D. The proneural basic helix-loop-helix gene ascl1a is required for retina regeneration. J Neurosci. 2008;28(5):1109–17. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4853-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer AJ. Neural regeneration in the chick retina. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2005;24(2):161–82. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer AJ, Bongini R. Turning Muller glia into neural progenitors in the retina. Mol Neurobiol. 2010;42(3):199–209. doi: 10.1007/s12035-010-8152-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer AJ, McGuire CR, Dierks BD, Reh TA. Insulin and fibroblast growth factor 2 activate a neurogenic program in Muller glia of the chicken retina. J Neurosci. 2002;22(21):9387–98. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-21-09387.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer AJ, Omar G. Transitin, a nestin-related intermediate filament, is expressed by neural progenitors and can be induced in Muller glia in the chicken retina. J Comp Neurol. 2005;484(1):1–14. doi: 10.1002/cne.20406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer AJ, Omar G, Eubanks J, McGuire CR, Dierks BD, Reh TA. Different aspects of gliosis in retinal Muller glia can be induced by CNTF, insulin and FGF2 in the absence of damage. Molecular Vision. 2004;10:973–986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer AJ, Reh TA. Muller glia are a potential source of neural regeneration in the postnatal chicken retina. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4(3):247–52. doi: 10.1038/85090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer AJ, Ritchey ER, Scott MA, Wynne A. Bullwhip neurons in the retina regulate the size and shape of the eye. Dev Biol. 2008;317(1):196–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer AJ, Scott MA, Ritchey ER, Sherwood P. Mitogen-activated protein kinase-signaling regulates the ability of Müller glia to proliferate and protect retinal neurons against excitotoxicity. Glia. 2009a;57(14):1538–1552. doi: 10.1002/glia.20868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer AJ, Scott MA, Tuten W. Mitogen-activated protein kinase-signaling stimulates Muller glia to proliferate in acutely damaged chicken retina. Glia. 2009b;57(2):166–81. doi: 10.1002/glia.20743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer AJ, Scott MA, Zelinka C, Sherwood P. A novel type of glial cell in the retina is stimulated by insulin-like growth factor 1 and may exacerbate damage to neurons and Muller glia. Glia. 2010;58(6):633–49. doi: 10.1002/glia.20950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer AJ, Seltner RL, Poon J, Stell WK. Immunocytochemical characterization of quisqualic acid- and N-methyl-D-aspartate-induced excitotoxicity in the retina of chicks. J Comp Neurol. 1998a;393(1):1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer AJ, Seltner RL, Stell WK. Opiate and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors in form-deprivation myopia. Vis Neurosci. 1998b;15(6):1089–96. doi: 10.1017/s0952523898156080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer AJ, Skorupa D, Schonberg DL, Walton NA. Characterization of glucagon-expressing neurons in the chicken retina. J Comp Neurol. 2006;496(4):479–94. doi: 10.1002/cne.20937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedlander M, Dorrell MI, Ritter MR, Marchetti V, Moreno SK, El-Kalay M, Bird AC, Banin E, Aguilar E. Progenitor cells and retinal angiogenesis. Angiogenesis. 2007;10(2):89–101. doi: 10.1007/s10456-007-9070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita Y, Imagawa T, Uehara M. Fine structure of the retino-optic nerve junction in the chicken. Tissue Cell. 2001;33(2):129–34. doi: 10.1054/tice.2000.0152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallina D, Todd L, Fischer AJ. A comparative analysis of Muller glia-mediated regeneration in the vertebrate retina. Exp Eye Res. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2013.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghai K, Zelinka C, Fischer AJ. Serotonin released from amacrine neurons is scavenged and degraded in bipolar neurons in the retina. J Neurochem. 2009;111(1):1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06270.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghai K, Zelinka C, Fischer AJ. Notch signaling influences neuroprotective and proliferative properties of mature Muller glia. J Neurosci. 2010;30(8):3101–12. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4919-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godwin JW, Pinto AR, Rosenthal NA. Macrophages are required for adult salamander limb regeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(23):9415–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300290110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S, Nelson BR, Buckingham B, Reh TA. Notch signaling regulates regeneration in the avian retina. Dev Biol. 2007;312(1):300–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.09.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes T, Luz-Madrigal A, Reis ES, Echeverri Ruiz NP, Grajales-Esquivel E, Tzekou A, Tsonis PA, Lambris JD, Del Rio-Tsonis K. Complement anaphylatoxin C3a is a potent inducer of embryonic chick retina regeneration. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2312. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang T, Cui J, Li L, Hitchcock PF, Li Y. The role of microglia in the neurogenesis of zebrafish retina. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;421(2):214–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.03.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joly S, Pernet V, Samardzija M, Grimm C. Pax6-positive Muller glia cells express cell cycle markers but do not proliferate after photoreceptor injury in the mouse retina. Glia. 2011;59(7):1033–46. doi: 10.1002/glia.21174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kageyama R, Ohtsuka T. The Notch-Hes pathway in mammalian neural development. Cell Res. 1999;9(3):179–88. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karl MO, Reh TA. Regenerative medicine for retinal diseases: activating endogenous repair mechanisms. Trends Mol Med. 2010;16(4):193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karl MO, Reh TA. Studying the generation of regenerated retinal neuron from Muller glia in the mouse eye. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;884:213–27. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-848-1_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohman RA, Rhodes JS. Neurogenesis, inflammation and behavior. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;27(1):22–32. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyritsis N, Kizil C, Zocher S, Kroehne V, Kaslin J, Freudenreich D, Iltzsche A, Brand M. Acute inflammation initiates the regenerative response in the adult zebrafish brain. Science. 2012;338(6112):1353–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1228773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamba D, Karl M, Reh T. Neural regeneration and cell replacement: a view from the eye. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2(6):538–49. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebrun-Julien F, Duplan L, Pernet V, Osswald I, Sapieha P, Bourgeois P, Dickson K, Bowie D, Barker PA, Di Polo A. Excitotoxic death of retinal neurons in vivo occurs via a non-cell-autonomous mechanism. J Neurosci. 2009;29(17):5536–45. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0831-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenkowski JR, Raymond PA. Muller glia: Stem cells for generation and regeneration of retinal neurons in teleost fish. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2013.12.007. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livesey FJ, Cepko CL. Vertebrate neural cell-fate determination: lessons from the retina. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2(2):109–18. doi: 10.1038/35053522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccioni RB, Rojo LE, Fernandez JA, Kuljis RO. The role of neuroimmunomodulation in Alzheimer's disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1153:240–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2008.03972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquardt T. Transcriptional control of neuronal diversification in the retina. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2003;22(5):567–77. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(03)00036-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto T, Turesson I, Book M, Gerwins P, Claesson-Welsh L. p38 MAP kinase negatively regulates endothelial cell survival, proliferation, and differentiation in FGF-2-stimulated angiogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2002;156(1):149–60. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200103096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnar E, Prechl J, Erdei A. Novel roles for murine complement receptors type 1 and 2 II. Expression and function of CR1/2 on murine mesenteric lymph node T cells. Immunol Lett. 2008;116(2):163–7. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrens J, Van Den Broeck W, Kempermann G. Glial cells in adult neurogenesis. Glia. 2012;60(2):159–74. doi: 10.1002/glia.21247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negishi K, Shinagawa S. Fibroblast growth factor induces proliferating cell nuclear antigen-immunoreactive cells in goldfish retina. Neurosci Res. 1993;18(2):143–56. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(93)90017-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson BR, Ueki Y, Reardon S, Karl MO, Georgi S, Hartman BH, Lamba DA, Reh TA. Genome-wide analysis of Muller glial differentiation reveals a requirement for Notch signaling in postmitotic cells to maintain the glial fate. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e22817. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CM, Ackerman KM, O'Hayer P, Bailey TJ, Gorsuch RA, Hyde DR. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha is produced by dying retinal neurons and is required for Muller glia proliferation during zebrafish retinal regeneration. J Neurosci. 2013;33(15):6524–39. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3838-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochrietor JD, Moroz TP, Linser PJ. The 2M6 antigen is a Muller cell-specific intracellular membrane-associated protein of the sarcolemmal-membrane-associated protein family and is also TopAP. Mol Vis. 2010;16:961–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak J, Wilken MS, Ueki Y, Cox KE, Sullivan JM, Taylor RJ, Levine EM, Reh TA. Ascl1 reprograms mouse Muller glia into neurogenic retinal progenitors. Development. 2013 doi: 10.1242/dev.091355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puschmann TB, Zanden C, Lebkuechner I, Philippot C, de Pablo Y, Liu J, Pekny M. HB-EGF affects astrocyte morphology, proliferation, differentiation, and the expression of intermediate filament proteins. J Neurochem. 2014;128(6):878–89. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahpeymai Y, Hietala MA, Wilhelmsson U, Fotheringham A, Davies I, Nilsson AK, Zwirner J, Wetsel RA, Gerard C, Pekny M. Complement: a novel factor in basal and ischemia-induced neurogenesis. Embo J. 2006;25(6):1364–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601004. others. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh G, Maclean AG, Philipp MT. Cytokines and chemokines at the crossroads of neuroinflammation, neurodegeneration, and neuropathic pain. Mediators Inflamm. 2013;2013:480739. doi: 10.1155/2013/480739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransohoff RM, Liu L, Cardona AE. Chemokines and chemokine receptors: multipurpose players in neuroinflammation. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2007;82:187–204. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(07)82010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roesch K, Jadhav AP, Trimarchi JM, Stadler MB, Roska B, Sun BB, Cepko CL. The transcriptome of retinal Muller glial cells. J Comp Neurol. 2008;509(2):225–38. doi: 10.1002/cne.21730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rompani SB, Cepko CL. A common progenitor for retinal astrocytes and oligodendrocytes. J Neurosci. 2010;30(14):4970–80. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3456-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth S, Shaikh AR, Hennelly MM, Li Q, Bindokas V, Graham CE. Mitogen-activated protein kinases and retinal ischemia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44(12):5383–95. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacks S, Lee Q, Wong W, Zhou W. The role of complement in regulating the alloresponse. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2009;14(1):10–5. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e32831ec551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schraml E, Fuchs R, Kotzbeck P, Grillari J, Schauenstein K. Acute adrenergic stress inhibits proliferation of murine hematopoietic progenitor cells via p38/MAPK signaling. Stem Cells Dev. 2009;18(2):215–27. doi: 10.1089/scd.2008.0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster B, Kovaleva M, Sun Y, Regenhard P, Matthews V, Grotzinger J, Rose-John S, Kallen KJ. Signaling of human ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) revisited. The interleukin-6 receptor can serve as an alpha-receptor for CTNF. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(11):9528–35. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m210044200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaham O, Menuchin Y, Farhy C, Ashery-Padan R. Pax6: a multi-level regulator of ocular development. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2012;31(5):351–76. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamsuddin N, Kumar A. TLR2 mediates the innate response of retinal Muller glia to Staphylococcus aureus. J Immunol. 2011;186(12):7089–97. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigemoto-Mogami Y, Hoshikawa K, Goldman JE, Sekino Y, Sato K. Microglia enhance neurogenesis and oligodendrogenesis in the early postnatal subventricular zone. J Neurosci. 2014;34(6):2231–43. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1619-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda M, Takamiya A, Yoshida A, Kiyama H. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation predominantly in Muller cells of retina with endotoxin-induced uveitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43(4):907–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thummel R, Enright JM, Kassen SC, Montgomery JE, Bailey TJ, Hyde DR. Pax6a and Pax6b are required at different points in neuronal progenitor cell proliferation during zebrafish photoreceptor regeneration. Exp Eye Res. 2010;90(5):572–82. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuttolomondo A, Di Raimondo D, di Sciacca R, Pinto A, Licata G. Inflammatory cytokines in acute ischemic stroke. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14(33):3574–89. doi: 10.2174/138161208786848739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Rooijen N. The liposome-mediated macrophage 'suicide' technique. J Immunol Methods. 1989;124(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(89)90178-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rooijen N. Liposome-mediated elimination of macrophages. Res Immunol. 1992;143(2):215–9. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2494(92)80169-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Rooijen N, Sanders A. Liposome mediated depletion of macrophages: mechanism of action, preparation of liposomes and applications. J Immunol Methods. 1994;174(1-2):83–93. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)90012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetter ML, Brown NL. The role of basic helix-loop-helix genes in vertebrate retinogenesis. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2001;12(6):491–8. doi: 10.1006/scdb.2001.0273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetter ML, Moore KB. Becoming glial in the neural retina. Dev Dyn. 2001;221(2):146–53. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan J, Ramachandran R, Goldman D. HB-EGF is necessary and sufficient for Muller glia dedifferentiation and retina regeneration. Dev Cell. 2012;22(2):334–47. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Ma W, Zhao L, Fariss RN, Wong WT. Adaptive Muller cell responses to microglial activation mediate neuroprotection and coordinate inflammation in the retina. J Neuroinflammation. 2011;8:173. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Won MH, Kang TC, Cho SS. Glial cells in the bird retina: immunochemical detection. Microsc Res Tech. 2000;50(2):151–60. doi: 10.1002/1097-0029(20000715)50:2<151::AID-JEMT7>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang SR, Kim SJ, Byun KH, Hutchinson B, Lee BH, Michikawa M, Lee YS, Kang KS. NPC1 gene deficiency leads to lack of neural stem cell self-renewal and abnormal differentiation through activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling. Stem Cells. 2006;24(2):292–8. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelinka CP, Scott MA, Volkov L, Fischer AJ. The Reactivity, Distribution and Abundance of Non-Astrocytic Inner Retinal Glial (NIRG) Cells Are Regulated by Microglia, Acute Damage, and IGF1. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e44477. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]