Abstract

Recent experimental and epidemiologic studies have suggested air pollution as a new risk factor for type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). We conducted a systematic review of the epidemiologic studies on the association of air pollution with T2DM and related outcomes published by December 2013. We identified 22 studies: 6 prospective studies on incident T2DM; 2 prospective study on diabetes mortality; 4 cross-sectional studies on prevalent T2DM; 7 ecological studies on mortality or morbidity from diabetes; and 3 studies on glucose or insulin levels. The evidence of the association between long-term exposure to fine particles (PM2.5) and the risk of T2DM is suggestive. The summary hazard ratio of the association between long-term PM2.5 exposure and incident T2DM was 1.11 (95% CI, 1.03–1.19) for a 10 μg/m3 increase. The evidence on the association between long-term traffic-related exposure (measured by nitrogen dioxide or nitrogen oxides) and the risk of T2DM was also suggestive although most studies were conducted in women. For short-term effects of air pollution on diabetes mortality or hospital/emergency admissions, we conclude that the evidence is not sufficient to infer a causal relationship. Because most studies were conducted in North America or in Europe where exposure levels are relatively low, more studies are needed in recently urbanized areas in Asia and Latin America where air pollution levels are much higher and T2DM is an emerging public health concern.

Keywords: Air pollution, meta-analysis, nitrogen dioxide, particulate matters, systematic review, type 2 diabetes

INTRODUCTION

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a metabolic disorder characterized by high glucose levels in the blood caused by insulin resistance and relative insulin deficiency [1]. There are currently 347 million people with diabetes around the world and T2DM consists of approximately 90% of people with diabetes [2]. High fasting blood glucose was ranked as the 7th risk factor for global disease burden and accounted for 3.4 million deaths and 3.6% of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) in 2010 [3]. While recent genome-wide association studies have uncovered genetic variants associated with T2DM risk [4, 5], these variants collectively account for only a small proportion of T2DM risk, suggesting a substantial role of modifiable risk factors in the development of T2DM. Although diet and physical activity are well established risk factors for T2DM [6], there is growing evidence that environmental pollutants also play an important role in the pathogenesis of T2DM [7].

Air pollution has been suggested as a risk factor for T2DM. Recent reviews based on animal studies summarized potential biological mechanisms of air pollution-induced insulin resistance and T2DM [8, 9] including particle-mediated alterations in glucose homeostasis, inflammation in visceral adipose tissue, endoplasmic reticulum stress in liver and lung, mitochondrial dysfunction and brown adipose tissue dysfunction, inflammation mediated through toll-like receptors and nucleotide oligomerization domain receptors, and inflammatory signaling in key regions of the hypothalamus. Epidemiologic studies of air pollution and T2DM have provided mixed results [10–29]. Some studies have reported significant positive associations, but others found no associations. To summarize epidemiologic findings, we conducted a systematic review of the epidemiologic studies on the association between ambient air pollution and T2DM. We searched for studies on incidence and prevalence of T2DM, diabetes mortality and glucose homeostatic measures such as fasting glucose, insulin, homeostatic model assessment-insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), and hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c). Because of small numbers of studies identified in each outcome and heterogeneity in air pollutants, we conducted a meta-analysis only for long-term exposure to fine particles (PM2.5) and incident T2DM to compute a summary measure of association. For other outcomes, we summarized each study findings descriptively.

METHODS

Search Strategy and Data Extraction

We conducted a literature search in PubMed and Web of Science on January 7, 2014 using the following key words: (air pollution OR particulate matter OR PM10 OR PM2.5 OR nitrogen oxides OR nitrogen dioxide OR fine particles OR coarse particles OR ozone OR traffic particle OR traffic exhaust NOT nitric oxide) AND (type 2 diabetes OR diabetes mellitus OR insulin OR glucose). We searched publications between January 1990 and December 2013 given that epidemiologic studies of air pollution and type 2 diabetes received attention just recently. In the Web of Science, we restricted articles from the following categories: Environmental sciences; Pharmacology pharmacy; Toxicology; Endocrinology metabolism; Public environmental occupational health; Cardiac cardiovascular system; Medicine general internal; Multidisciplinary science. A total of 933 articles from PubMed and 481 from Web of Science were identified and the abstracts were reviewed. Only human studies that included original data were considered. We also excluded studies conducted in children or pregnant women (gestational diabetes), studies with no air pollution data, studies with no effect estimate in relation to air pollution exposure, or studies that examined T2DM as an effect modifier. Finally 21 original studies were included in this review. We extracted the following information from each study and summarized by study design: first author, year of publication, study population, sample size, study (follow-up) period, age, percent of female subjects, exposure distribution (median (interquartile range (IQR)), mean±standard deviation (SD), or range), number of cases, covariates adjusted, and measures of association. We only considered exposure measures from ambient concentrations of air pollutants (i.e. studies on indoor air pollution were excluded) and did not include exposure measures from emission inventory.

Statistical Analysis

To make the reported measures of association (e.g., hazard ratio (HR), odds ratio (OR), percent change) across studies comparable, we rescaled the effect estimates for an interquartile range (IQR) increase and for a 10 unit (μg/m3 or ppb) increase. We conducted a meta-analysis of the association between PM2.5 and incident T2DM with the identified 4 cohort studies [13, 15, 26]. We used a random-effects model to compute a summary HR. Two studies reported HRs from a multi-pollutant model [15, 26]. We extracted all reported HRs but considered the HRs from a single pollutant model in the meta-analysis. Because the number of studies for the meta-analysis was small, we did not perform a test for publication bias. R version 3.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, http://www.w-project.org) with the package metafor was used.

RESULTS

We included 6 prospective cohort studies on incident T2DM; 2 prospective cohort study on diabetes mortality; 4 cross-sectional studies on prevalence of T2DM or impaired glucose metabolism (IGM: fasting glucose≥100 mg/dL or physician-diagnosis); 3 studies on continuous measures of glucose homeostasis; 4 ecological studies on mortality from diabetes; and 3 ecological studies on hospital/emergency admissions for diabetes.

Long-Term Exposure to Air Pollution and Incidence of Type 2 Diabetes

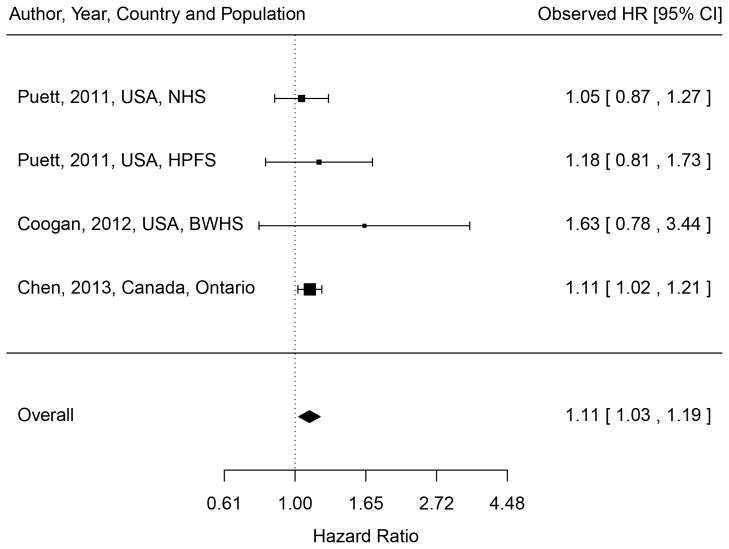

We identified 6 cohort studies of incident T2DM (Table 1) [10, 13, 15, 23, 26]. Two independent cohort studies (the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) and the Health Professional Follow-up Study (HPFS)) were examined in a study by Puett and colleagues [26]. Three studies were performed in the U.S. and one each in Germany, Denmark and Canada. Three cohort studies (SALIA (Study on the Influence of Air Pollution on Lung, Inflammation and Aging), BWHS (Black Women’s Health Study), and NHS) included only women and the HPFS included only men. Incidence rates ranged from 402 per 100,000 subjects in HPFS to 1,302 per 100,000 in the Ontario residents’ study. Four studies examined either PM2.5 (annual mean ranged from 10.6 μg/m3 to 21.1 μg/m3) or PM10 (26.9 μg/m3 to 46.9 μg/m3); three studies examined either NOx (41.6 ppb) or NO2 (15.4 to 34.5 μg/m3). For PM, all four studies found weak positive associations and only the Ontario residents’ study reported a statistically significant association (adjusted hazard ratio (HR)=1.06 (95% confidence interval (CI), 1.01, 1.11) for an IQR increase in PM2.5 (5.4 μg/m3); HR=1.11 (95% CI, 1.02, 1.21) for a 10 μg/m3 increase) [13]. The random-effect summary HR for a 10 μg/m3 increase in PM2.5 was 1.11 (95% CI, 1.03, 1.19), with no evidence of heterogeneity among the three studies with PM2.5 measures available (test for heterogeneity: Qdf=3 = 1.08, p-value=0.78) (Figure 1). For NO2 or NOx (traffic-related particles), two studies conducted in women’s cohorts reported significant positive associations (HR=1.42 (95% CI, 1.16, 1.73) for NO2 (IQR=15 μg/m3) in SALIA; HR=1.25 (95% CI, 1.07, 1.46) for NOx (IQR=12.4 ppb) in BWHS), whereas the Danish Diet, Cancer, and Health (DCH) study found no association when all cases of T2DM were examined but found a weak marginal association when only confirmed T2DM cases were considered (HR=1.04 (95% CI, 1.00, 1.08) for NO2 (IQR=4.9 μg/m3)).

Table 1.

Observational cohort studies of long-term air pollution exposure and diabetes mellitus (DM)

| 1st author, Year [ref] |

Population | Sample size |

Study (follow-up) period |

Age (y) Female (%) |

Outcome Definition | No of cases (IR or %) |

Exposure | Median (IQR) or Mean±SD (IQR)g |

Adjusted RR (95% CI) per IQR increase |

Adjusted RR (95% CI) per 10 unit increase |

Covariate adjusted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prospective Study on Incident DM | |||||||||||

| Kramer, 2010 [23] | SALIA, Germany | 1,775 | 1990–2006 | 54–55 100% |

Self-reported physician diagnosis | 187 (658/105 py) | Monitor PM10 NO2 LUR Soot NO2 |

46.9 (10) 41.7 (25) 1.89 (0.39)×10−5m 34.5 (15) |

1.16 (0.81, 1.65) 1.34 (1.02, 1.76) 1.27 (1.09, 1.48) 1.42 (1.16, 1.73) |

1.16 (0.81, 1.65) 1.12 (1.01, 1.25) 1.26 (1.10, 1.44) |

Age, BMI, education, smoking, heating w/ fossil fuels, workplace exposure w/ dust/fumes, extreme temperature |

| Puett, 2011 [26] | NHS, US | 74,412 | 1989–2002 | 55±7 100% |

↑ plasma glucose on ≥2 different occasionsa, DM symptoms and a single ↑ plasma glucose, or Hypoglycemic medication | 3,784 (448/105 py) | LUR PM2.5 PM10 PM10–2.5 |

17.5±2.7 (4.3) 26.9±4.8 (6.3) 9.4±2.9 (3.7) |

1.02 (0.94, 1.09) 1.03 (0.98, 1.09) 1.04 (0.98, 1.10) |

1.05 (0.87, 1.22) 1.05 (0.97, 1.15) 1.11 (0.95, 1.29) |

Age, BMI, smoking, alcohol, physical activity, diet, hypertension, season, calendar year, residence state |

| Puett, 2011 [26] | HPFS, US | 15,048 | 1989–2002 | 57±10 0% |

688 (402/105 py) | LUR PM2.5 PM10 PM10–2.5 |

18.3±3.1 (4.0) 28.5±5.5 (7.2) 10.3±3.3 (4.2) |

1.07 (0.92, 1.24) 1.06 (0.94, 1.20) 1.04 (0.93, 1.16) |

1.18 (0.81, 1.71) 1.08 (0.92, 1.29) 1.10 (0.84, 1.42) |

Age, BMI, smoking, alcohol, physical activity, diet, hypertension, season, calendar year, residence state | |

| Andersen, 2012 [10] | DCH, Denmark | 51,818 | 1993/97–June 2006 (mean=9.7 yrs) | 56±8 52.6% |

All cases in the National Diabetes Registry (NDR)b Confirmed DM: excluding those included in NDR only because of a blood glucose test |

All cases 4,040 (800/105 py) Confirmed 2877 (570/105 py) |

LUR NO2 (’71-e) NO2 (’91-e) NO2 (1- eyr) |

14.5 (4.9) 15.3 (5.6) 15.4 (5.6) |

All cases 1.00 (0.97, 1.03) 1.00 (0.97, 1.04) 0.98 (0.95, 1.01) Confirmed DM 1.04 (1.00, 1.08) 1.04 (1.01, 1.07) 1.02 (0.98, 1.05) |

All cases 1.00 (0.94, 1.06) 1.00 (0.95, 1.07) 0.96 (0.91, 1.02) Confirmed DM 1.08 (1.00, 1.17) 1.07 (1.02, 1.13) 1.04 (0.96, 1.10) |

Age, sex, BMI, waist-to-hip ratio, education, smoking, SHS, alcohol, physical activity, fruit, fat, calendar year |

| Coogan, 2012 [15] | BWHS, Los Angeles, US | 3,992 | 1995–2005 (mean=10 yrs) | 21–69 100% |

Self-reported physician diagnosis at ≥30 yrs of age (96% confirmed) | 183 (458/105 py) | LUR PM2.5 NOx |

21.1 (1.3) 41.6 (12.4) ppb |

Single pollutant 1.07 (0.97, 1.17) 1.25 (1.07, 1.46) Multi-pollutanti 1.02 (0.92, 1.13) 1.24 (1.05, 1.45) |

Single pollutant 1.63 (0.78, 3.44) 1.20 (1.06, 1.36) Multi-pollutanti 1.15 (0.51, 2.58) 1.19 (1.04, 1.36) |

Age, BMI, education, income, No of people/household, neighborhood SES, smoking, alcohol, physical activity, family history |

| Chen, 2013 [13] | Residents in Ontario, Canada | 62,012 | 1996/2005–2010 (mean=8 yrs) | 55±14 55% |

Ontario Diabetes Databasec | 6,310 (1302/105 py) | Satellite PM2.5 |

Mean=10.6 (5.4)h (range: 2.6–19.1) |

1.06 (1.01, 1.11) |

1.11 (1.02, 1.21) |

Age (strata), sex, race, marital status, BMI, education, income, smoking, physical activity, alcohol, diet, hypertension, urban residency |

| Prospective Study on Mortality from DM | |||||||||||

| Raaschou-Nielsen, 2013 [27] | DCH, Denmark | 52,061 | 1993/97–2009 (mean=13 yrs) | 56.1 52.5% |

Danish Register of Causes of Death (ICD-10 E10–E14) | 122 (18/105 py) | LUR NO2 (’71-e) NO2 (’91-e) NO2 (1-yre) |

15.1 14.5 16.6 |

1.14 (0.99, 1.32) 1.10 (0.95, 1.27) 1.08 (0.94, 1.23) |

1.31 (0.98, 1.76) 1.18 (0.92, 1.50) 1.14 (0.90, 1.44) |

Age (time scale), sex, BMI, waist circumference, education, smoking, SHS, physical activity, alcohol, fruit, fat, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, calendar year |

| Brook, 2013 [30] | The 1991 Canadian census mortality follow-up, Canada | 2,145,400 | 1991–2001 | ≥25 51% |

Canadian Mortality Database (ICD-9 250; ICD-10 E10–E14) | 5,200 (2.4/105 py) | Satellite PM2.5 (2001–2006) |

8.7±3.9 (6.2) | 1.28 (1.22, 1.35) | 1.49 (1.37, 1.62) | Age (strata), sex (strata), aboriginal ancestry, visible minority, marital status, education, employment, occupation, income, contextual covariates |

| Cross-sectional study on prevalent DM | |||||||||||

| Brook, 2008 [11] | Respir disease clinic patients from Hamilton and Toronto, Canada | Hamilton M: 2306 F: 2922 Toronto M: 1146 F: 1260 |

1992–1999 | Median M: 61.5 F: 60.4 56% M: 61.2 F: 59.8 52% |

Ontario Health Insurance Plan physician billing database and hospital discharge database (ICD-9 250)d |

M: 395 (17) F: 445 (15) M: 227 (20) F: 185 (15) |

LUR NO2 |

M: 15.2 (3.2) F: 15.3 (3.0) M: 23.0 (4.2) F: 22.9 (3.9) |

1.03 (0.85, 1.20) 1.08 (0.94, 1.26) 0.92 (0.74, 1.09) 1.23 (1.00, 1.50) |

1.10 (0.60, 1.79) 1.33 (0.82, 2.16) 0.82 (0.48, 1.22) 1.71 (0.99, 2.84) |

Age, BMI, neighborhood income |

| Dijkema, 2011 [17] | Residents of Westfriesland, Netherlands | 8,018 | 1998–2000 | Median: 58 (50–75) 51% |

Self-reported physician diagnosis + fasting plasma glucose | 619 (8) | LUR NO2 |

15.2 (2.3) 140 (146) m |

Q1: Reference Q2: 1.03 (0.82, 1.31) Q3: 1.25 (0.99, 1.56) Q4: 0.80 (0.63, 1.02) |

Age, sex, income | |

| Teichert, 2013 [28] | SALIA, Germany | 363 | 2008–2009 | 74±2.6 100% |

Fasting glucose ≥100 mg/dL or physician-diagnosis | 174 (48.3) | LUR NO2 NOx PM2.5(abs)f PM2.5 PM10–2.5 PM10 |

37.8±9.8 69.3±30.0 2.8±0.8 34.0±3.1 18.2±3.3 51.0±4.9 |

1.47 (1.05, 2.05) 1.41 (1.01, 1.97) 1.26 (0.95, 1.67) 1.15 (0.81, 1.63) 1.13 (0.79, 1.60) 1.21 (0.87, 1.68) |

Age, BMI, education, smoking, SHS, indoor mold, season of blood sampling | |

| Ecological study on prevalent DM | |||||||||||

| Pearson, 2010 [25] | All U.S. counties | 2,754 counties | 2004–2005 | ≥20 – |

County-level prevalence of self-reported physician-diagnosis | Range: 3.0–14.8 | Fused model, PM2.5 | County-level, Range: 2.5–17.7 15.1 14.5 16.6 |

2004: 1.15 (1.02, 1.32) 2005: 0.92 (0.75, 1.13) |

Median age, % men, per capita income, % population >25 yrs with a high school diploma, race/ethnicity, health insurance, obesity, physical activity, latitude, population density | |

SALIA, Study on the Influence of Air Pollution on Lung, Inflammation and Aging; NHS, Nurses Health Study; HPFS, Health Professional Follow-up Study; DCH, Danish Diet, Cancer, and Health; BWHS, Black Women’s Health Study; LUR, land-use regression; ICD, International Classification of Disease; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation; M, male; F, female; IR, incident rate; py, person-years; BMI, body mass index; SHS, second-hand smoke; SES, socioeconomic status; RR, relative risk.

An elevated plasma glucose concentration was defined as a fasting plasma glucose > 140 mg/dL for cases diagnosed before or during 1997 or > 126 mg/dL for cases diagnosed after 1997, a random plasma glucose concentration > 200 mg/dL, or a plasma glucose concentration > 200 mg/dL after >2 hr of oral glucose tolerance testing.

The National Diabetes Registry (NDR) included 1) diabetes hospital discharge diagnoses in the National Patient Register defined as ICD-10 (DE10-14, DH36.0, DO24) or ICD-8 (249 and 250); 2) chiropody for diabetes patients, five blood glucose measurements within 1 year, or two blood glucose measurements per year for 5 consecutive years, registered in the National Health Insurance Registry; or 3) second purchase of insulin or oral glucose-lowering drugs within 6 months, registered in the Register of Medicinal Product Statistics. Type 1 and type 2 diabetes are not distinguishable from NDR.

The Ontario Diabetes Database included information on hospital admission with a diagnosis of diabetes (ICD-9 250 or ICD-10 E10–E14) or ≥2 physician claims for diabetes within a 2-year period. Gestational diabetes was excluded. It has been validated (86% sensitivity and 97% specificity).

Subjects were classified as diabetic if the diagnosis had been made in two or more claim submissions by a general practitioner, one claim submission by a specialist, or in any hospitalization.

Andersen et al [10] and Raaschou-Nielsen et al [27] examined three NO2 variables averaged from 1971 to follow-up (NO2 (’71-)), from 1991 to follow-up (NO2 (’91-)) and a 1-yr before baseline (NO2 (1-yr)).

PM2.5 based on filter absorbance (soot).

Unit is μg/m3 unless otherwise specified.

IQR data for Chen (2013) obtained directly from the authors; IQR data for Raaschou-Nielsen (2013) assumed the same as those in Andersen (2012) given the same DCH cohort.

Multi-pollutant models included two pollutants in models simultaneously.

Figure 1.

Meta-analysis of the association between PM2.5 and incident diabetes. Hazard ratios (HRs) were based on a 10 μg/m3 increase. Random effect model was used to compute the overall (summary) HR.

Two studies examined long-term exposure to air pollution and incident diabetes mortality [30, 27]. In a study conducted in Denmark (the DHC cohort study followed from 1993 to 2009, N=52,061, 122 cases), an IQR increase in NO2 (IQR=4.9 μg/m3) averaged from 1971 to the follow-up period was associated with a HR for diabetes equal to 1.14 (95% CI, 0.99, 1.32) [27]. A large national follow-up study conducted in Canada (The 1991 Canadian census mortality follow-up from 1991 to 2001, N=2,145,400, 5,200 cases) found a significant positive association between average concentrations of PM2.5 for the period from 2001 to 2006 and diabetes mortality (HR=1.28 (95% CI, 1.22, 1.35) for an IQR increase in PM2.5 (6.2 μg/m3) [30].

Long-Term Exposure to Air Pollution and Prevalence of Type 2 Diabetes

Four studies (three observational and one ecological) reported cross-sectional associations between long-term air pollution and prevalence of T2DM or IGM (Table 1). Two observational cross-sectional studies performed in Canada and The Netherlands examined annual NO2 concentrations as the exposure measure, whereas the SALIA study (Germany) examined various air pollution measures including PM2.5, PM10–2.5, PM10, NO2 and NOx. The ecological study conducted in the U.S. was based on county-levels of diabetes prevalence and PM2.5 annual concentrations in 2004 and 2005 (n=2,754 counties). In patients from a respiratory disease clinic from Hamilton (N=5,228, prevalence of T2DM=15%) and Toronto (N=2,406, prevalence of T2DM=17%), Canada, an IQR increase in NO2 was positively associated with T2DM among women (OR=1.08 (95% CI, 0.94, 1.26) in Hamilton; OR=1.23 (95% CI, 1.00, 1.50) in Toronto) but not men (OR=1.03 (95% CI, 0.85, 1.20) in Hamilton; OR=0.92 (95% CI, 0.74, 1.09) in Toronto) [11]. In a study of 8,018 residents (prevalence of T2DM=8%) from Westfriesland, Netherlands, NO2 was not associated with the prevalence of T2DM [17]. A study conducted in the SALIA cohort, Germany (N=363, 100% women, prevalence of IGM=48%) found significant positive associations of IGM with NO2 (OR=1.47 (95% CI, 1.05, 2.05) per IQR increase) and NOx (OR=1.41 (95% CI, 1.01, 1.97)) [28]. Finally, in an ecological study of the association between county-level PM2.5 concentrations and diabetes prevalence in the US [25], a 10 μg/m3 increase in PM2.5 was associated with a 1.15% (95% CI, 1.02, 1.32%) increase in the diabetes prevalence in 2004 and a 0.92% (95% CI, 0.75, 1.13%) increase in 2005.

Air Pollution and Measures of Glucose Homeostasis

Three studies evaluated continuous measures of glucose homeostasis (Table 2) [12, 14, 21]. A study from Taiwan examined the associations with long-term exposures (annual concentrations) to 5 criteria pollutants (PM2.5, PM10, NO2, SO2 and O3), whereas two studies from Korea and Michigan, U.S. examined short-term exposures (up to 7-day lags of PM10, NO2, SO2 and O3 in the Korean study; 5-day long exposure to PM2.5 in the U.S. study). All three examined fasting glucose levels; a study from Taiwan additionally examined hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), a measure of glycated hemoglobin in red blood cells that reflects average glucose level over the previous 3 months [31]; two studies from Korea and Michigan, U.S. examined fasting insulin and an indicator of insulin resistance (homeostatic model assessment-insulin resistance (HOMA-IR)) [12, 21]. In a study of 1,023 participants from the Social Environment and Biomarkers of Aging Study in Taiwan, fasting glucose and HbA1c were associated with all criteria pollutants except SO2 [14]. A study of 560 older people in Korea reported that short-term exposure to PM10, NO2 and O3 but not SO2 were associated with increased fasting glucose, insulin and HOMA-IR, which suggests reduced metabolic insulin sensitivity [21]. A human panel study with 25 healthy non-smoking adults conducted in Michigan, U.S. also found that sub-acute exposure to PM2.5 (5-day-long cumulative exposure) was associated with increased fasting glucose, insulin and HOMA-IR [12].

Table 2.

Observational studies of air pollution exposure and continuous glucose/insulin measures

| 1st author, Year [ref] |

Population | Sample size |

Study year |

Age (y), Female (%) |

Outcomes, mean±SD |

Exposure | Lag or duration |

Median (IQR) or Mean±SDa |

Adjusted change (95% CI) per IQR increase |

Adjusted change (95% CI) per 10 unit increase |

Covariate adjusted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chuang, 2011 [14] | SEBAS, Taiwan | 1,023 | 2000 | 69±8.7 (54–90) 42.3% |

Glucose: 107±37 mg/dl HbA1c: 5.8±1.4% |

Monitor PM10 PM2.5 NO2 SO2 O3 |

1-y 1-y 1-y 1-y 1-y |

67.8±33.5 35.3±15.9 24.5±9.5 ppb 4.9±3.6 ppb 23.0±6.8 ppb |

Glucose: 22.9 (14.9, 30.8) 36.6 (19.2, 53.9) 17.0 (10.4, 23.7) 4.95 (−7.05, 17.0) 21.1 (12.0, 30.2) HbA1c: 1.40 (1.11, 1.69) 2.24 (1.47, 3.00) 1.08 (0.84, 1.33) 0.20 (−0.23, 0.64) 1.30 (0.97, 1.63) |

Glucose: 4.8 (3.1, 6.4) 17.9 (9.4, 26.4) 13.3 (8.1, 18.5) 15.6 (−22.2, 53.3) 23.6 (13.4, 33.7) HbA1c: 0.29 (0.23, 0.35) 1.10 (0.72, 1.47) 0.84 (0.65, 1.03) 0.63 (−0.72, 1.98) 1.45 (1.08, 1.82) |

Age, sex, BMI, smoking, alcohol, smooth functions of visit date, yearly temperature |

| Kim, 2012 [21] | KEEP, Korea | 560 | 2008–2010 | 70.7 (60–87) 73.9% |

Glucose: 96±21 mg/dl Insulin: 6.9±6.0 μU/ml HOMA-IR: 1.7±1.7 |

Monitor PM10 NO2 O3 |

Lag 4-d 7-d 5-d |

39.9 (20.8) 35.2 (10.8) ppb 19.3 (15.1) ppb |

Glucose: 1.98 (0.90, 3.06) 1.98 (0.90, 3.06) 3.42 (1.62, 5.04) Insulin: 0.21 (−0.22, 0.64) 0.72 (0.29, 1.14) 0.71 (0.02, 1.39) HOMA-IR: 0.14 (−0.003, 0.29) 0.28 (0.13, 0.42) 0.30 (0.06, 0.53) |

Glucose: 0.95 (0.43, 1.47) 1.83 (0.83, 2.83) 2.26 (1.07, 3.34) Insulin: 0.10 (−0.11, 0.31) 0.67 (0.27, 1.06) 0.47 (0.01, 0.92) HOMA-IR: 0.07 (−0.001, 0.14) 0.26 (0.12, 0.39) 0.20 (0.04, 0.35) |

Age, sex, BMI, cotinine, outdoor temperature, dew point temperature |

| Brook, 2013 [12] | Healthy adults living in rural Michigan | 25 | 2009–2010 | 38±12 68% G: 84±8 mg/dl I: 15±6 μU/ml H: 3.3±1.5 Exposure G: 74±6 mg/dl I: 13±5 μU/ml H: 2.4±1.0 Post-exposure G: 79±7 mg/dl I: 15±6 μU/ml H: 2.8±1.2 |

Pre-exposure | Monitor PM2.5 |

5-d long exposure |

11.5±4.8 |

G: 5.4 (0.5, 10.3) I: 2.9 (0.2, 5.6) H: 0.7 (0.1, 1.3) |

Age, BMI |

SEBAS, Social Environment and Biomarkers of Aging Study; KEEP, Korean Elderly Environmental Panel Study; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; HOMA-IR, homeostatic model assessment-insulin resistance; exp, exposure; G, glucose; I, insulin; H, HOMA-IR; BMI, body mass index..

Unit is μg/m3 unless otherwise specified.

Short-Term Exposure to Air Pollution and Mortality from Diabetes

We identified four ecological studies (Poisson time-series or case-crossover design studies) of short-term exposure to air pollution and mortality from diabetes (Table 3) [18–20, 24]. These studies included both type-1 and type 2 diabetes. In a study conducted in Montreal, Canada between 1984 and 1993, the estimated percent change in daily diabetes mortality for an IQR increase in air pollution was 13.2% (95% CI, 2.69%, 24.8%) for PM10, 12.0% (95% CI, 3.01%, 21.8%) for PM2.5, and 3.79%, (95% CI, 0.69%, 6.98%) for sulfate (predicted from PM2.5). In a latter study conducted between 1990 and 2003 the corresponding percent changes were 3.45% (95% CI, 1.29%, 5.66%) for NO2, 2.74% (95% CI, 0.75%, 4.77%) for CO and 1.89%, (95% CI, 0.05%, 3.76%) for SO2 [19]. In a time-series study using daily mortality from diabetes between 2001 and 2002 conducted in Shanghai, China observed marginal associations with PM10 (4.18% (95% CI, 0.00%, 8.54%) per IQR increase) and SO2 (3.82%, (95% CI, 0.00%, 7.78%)) [20]. In Massachusetts, U.S., black carbon (5.7%, (95% CI, −1.7%, 13.7%)) and sulfate (2.9%, (95% CI, −3.1%, 9.5%)) were positively but non-significantly associated with the deaths from diabetes for the years 1995–2002 [24].

Table 3.

Ecological studies of short-term air pollution exposure and diabetes mortality and morbidity

| 1st author, Year [ref] |

Population | Study period |

Age (y) Female (%) |

Outcome | Total cases (/day) |

Exposureb | Lag | Median (IQR) or Mean±SDc |

Adjusted percent change (95% CI) per IQR increase |

Adjusted percent change (95% CI) per 10 unit increase |

Covariate adjusted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ecological Study on Mortality from Diabetes | |||||||||||

| Goldberg, 2001 [18] | Montreal, Canada | 1984–1993 | – | ICD-9: 250 | 3677 | PM10 PM2.5 PM2.5 (pred)a Sulfate Sulfate(pred)a |

1-d | 28.5 (21.3) 14.7 (12.5) 15.4 (9.5) 2.2 (2.5) 3.1 (2.9) |

13.2 (2.69, 24.8) 12.0 (3.01, 21.8) 5.94 (1.69, 10.4) 2.39 (−0.28, 5.13) 3.79 (0.69, 6.98) |

5.99 (1.25, 11.0) 9.49 (2.40, 17.1) 6.26 (1.78, 10.9) 9.91 (−1.12, 22.2) 13.7 (2.40, 26.2) |

Long-term trend, weather |

| Kan, 2004 [20] | Shanghai, China | 2001–2002 | – | ICD-9: 250 | 434 (0.59/day) | PM10 NO2 SO2 |

1-d | 73 (68.5) 64 (29) 40 (31) |

4.2 (0.0, 8.5) 3.8 (0.0, 7.8) 3.5 (−3.1, 10.4) |

0.6 (0.0, 1.2) 1.3 (0.0, 2.6) 1.1 (−1.0, 3.2) |

Long-term trend, weather, day of week |

| Maynard, 2007 [24] | Massachusetts, US | 1995–2002 | 76.6 57% |

ICD-9: 250, ICD-10: E10–E14 | 2,694 | BC Sulfate |

1-d | 0.218 (0.203) 2.378 (2.259) |

5.7 (−1.7, 13.7) 2.9 (−3.1, 9.5) |

Apparent temperature, day of week | |

| Goldberg, 2013 [19] | Montreal, Canada | 1990–2003 | 65 and older – |

ICD-10: E10–E14 | 38,883 (7.6/day) | PM2.5 NO2 CO SO2 O3 |

2-d distributed lags | 6.9 (6.9) 36.0 (17.6) 5.4 (3.3) 11.5 (8.9) 29.8 (22.4) |

1.83 (−0.53, 4.25) 3.45 (1.29, 5.66) 2.74 (0.75, 4.77) 1.89 (0.05, 3.76) −0.84 (−3.48, 1.88) |

2.66 (−0.77, 6.21) 1.95 (0.73, 3.18) 8.54 (2.29, 15.2) 2.13 (0.06, 4.24) −0.38 (−1.57, 0.83) |

Temporal variability, maximum temperature |

| Ecological Study on Hospital/Emergency Admissions for Diabetes | |||||||||||

| Zanobetti, 2009 [29] | 26 US communities | 2000–2003 | 65 and older – |

ICD-9: 250 | 46,192 (1.2/day) | PM2.5 All Winter Spring Summer Autumn |

2-d moving average | 15.3±8.2 (range: 6.1–24) |

2.74 (1.30, 4.20) −0.52 (−3.20, 2.24) 5.43 (1.97, 9.02) 1.85 (−1.02, 4.80) 4.78 (2.16, 7.46) |

Long-term trend, season, temperature, dew-point temperature day of week, | |

| Kloog, 2012 [22] | New England, US | 2000–2006 | 77 (65 and older) 57% | ICD-9: 250 | 398,596 | PM2.5 PM2.5 |

0-d 1-y average |

8.55 (5.32) 9.65 (0.98) |

0.51 (0.33, 0.69) 0.60 (0.31, 0.90) |

0.96 (0.62, 1.30) 6.33 (3.22, 9.53) |

Temperature, day of week, socioeconomic factors |

| Dales, 2012 [16] | Santiago, Chile | 2001–2008 | – | ICD-10: E10–E11 |

(1.79/day) |

PM10 PM2.5 NO2 CO SO2 O3 |

6-d distributed lags | 67.6 (27.7) 31.5 (16.7) 43.6 (25.0) ppb 0.96 (0.85)ppm 9.0 (4.7) ppb 64.4 (38.1) ppb |

11.0 (6.9, 15.2) 10.8 (6.3, 15.5) 12.1 (5.0, 19.7) 14.6 (9.8, 19.7) 13.9 (6.4, 22.0) 6.9 (−1.8, 16.3) |

3.8 (2.4, 5.3) 6.3 (3.7, 9.0) 4.7 (2.0, 7.5) –d 31.9 (14.1, 52.5) 1.8 (−0.48, 4.1) |

Long-term trend, day of week, humidex |

IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation; ICD, International Classification of Disease.

All air pollution data used in ecological studies of short-term exposure were based on data from monitoring stations except PM2.5(pred) and sulfate(pred).

Predicted PM2.5 and sulfate concentrations from PM2.5 when measurements were not taken, based on coefficient of haze, the extinction coefficient and measured sulfate as predictors.

All exposure measures in ecological studies of short-term air pollution were based on monitoring data.

Unit is μg/m3 unless otherwise specified.

Percent change not reported because a 10-unit is too big compared to IQR (0.85).

Short-Term Exposure to Air Pollution and Hospital/Emergency Admissions for Diabetes

Three studies examined hospital/emergency admissions for diabetes using the time-series Poisson model analysis or the case-crossover design (Table 3) [16, 22, 29]. These studies also included both type-1 and type 2 diabetes. Two studies by Zanobetti et al. [29] and Dales et al. [16] examined short-term exposures to air pollution and one study by Kloog et al. [22] examined both short-term and long-term effects of PM2.5. Zanobetti et al. found that a 10 μg/m3 increase in 2-day averaged PM2.5 was associated with a 2.74% (95% CI, 1.30, 4.20%) increase in emergency admissions for diabetes in 26 U.S. communities between 2000 and 2003 [29]. In a study from Santiago, Chile between 2001 and 2008, Dales et al. found that IQR increases in criteria pollutants except ozone were associated with an 11% to a 15% increase in the risk for hospitalization for diabetes [16]. In a study conducted in New England, U.S., a 10 μg/m3 increase in short-term and long-term PM2.5 was associated with a 0.96% (95% CI, 0.62%, 1.30%) and a 6.33% (95% CI, 3.22%, 9.53%) increase in the risk for diabetes hospitalization, respectively [22].

DISCUSSION

In general, two different study designs were used to examine the association between air pollution and T2DM: observational studies of incidence, prevalence or mortality from T2DM or continuous measures of insulin resistance in relation to long-term exposure to air pollution; and ecological studies of daily mortality or hospital/emergency admissions in relation to short-term exposure. For the incidence and prevalence studies and observational diabetes mortality studies, either annual concentrations of particulate matters (mostly PM2.5 or PM10 and PM10–2.5 (coarse particles)) or nitrogen oxides (NOx or NO2) which were estimated using land-use regression [10, 11, 15, 17, 26–28, 30] or satellite-based approach [13] were used as exposure metrics, whereas ecological studies of DM mortality or hospital/emergency admissions (except the study by Kloog et al. [22]) used daily concentrations of criteria pollutants (PM2.5, PM10, NO2, CO, SO2, and O3) based on central monitoring or the nearest monitors. Given the differences in study design and disease etiology between long-term air pollution effects on the development of T2DM vs. short-term air pollution effects on daily diabetes mortality or morbidity, we discussed causal relationships based on epidemiologic findings by these two study designs separately.

Observational Studies in Relation to Long-Term Exposure

Consistency

For PM2.5, all studies showed positive associations with either incident T2DM [13, 15, 23, 26], diabetes mortality [30] or prevalent IGM [28]. Our meta-analysis suggests an association between PM2.5 and incident T2DM with a small summary HR of 1.11 (95% CI, 1.03, 1.19). One large national-level study examined more than 2 millions of Canadians showed a strong positive association between PM2.5 and diabetes mortality. For NO2 or NOx, a measure of traffic particle exposure, three studies from two women’s cohorts (SALIA and BWHS) reported a significant association with incident T2DM [15, 23] or prevalent IGM [28], and one relatively large study from Denmark (approximately 52,000 participants) also reported a significant association with confirmed T2DM (but not with all cases of T2DM) [10] or diabetes mortality [27]. Two other cross-sectional studies also found a suggestive association with prevalent T2DM only among women [11, 17].

Strength

One Canadian census mortality study and two women’s cohort studies (SALIA and BWHS) reported relatively strong associations (HRs from 1.25 to 1.42 for an IQR increase in PM2.5, NOx or NO2), whereas other studies reported modest associations (i.e., HRs or ORs <1.1). Although most studies used land-use regression models to generate improved exposure estimates, the use of stationary monitoring data rather than personal monitoring may lead to exposure measurement error. Another potential source of exposure measurement error is that one year average concentrations prior to baseline or at any given year are used as proxies for the long-term exposure. Exposure measurement error may occur if individual exposure levels have changed over time before baseline, for example, if individuals have moved often before baseline. These errors generally bias the observed association towards the null.

Temporality

Eight prospective studies have examined incident T2DM or diabetes mortality which supports the temporality issue that the cause precedes the effect in time. Reverse causation is unlikely given that onset of T2DM may not lead to an increase in air pollution exposure.

Biological Plausibility

As introduced early, several animal studies support potential biological mechanisms, for example, cumulative exposure to air pollution can lead to a reduction in Akt phosphorylation in the liver, skeletal muscle and white adipose tissue which influences insulin signaling pathway and apoptosis [32, 33]. Fine particulate matter exposure can induce inflammation in visceral adipose tissue by increasing adipose tissue macrophages [34]. PM2.5 exposure may also induce endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress not only in the lung but in the liver which induces hepatic insulin resistance [35]. These mechanisms eventually affect insulin resistance and cause T2DM [8, 9].

Causal Inference

Based on consistency of the observed findings, the evidence of the association between long-term exposure to PM2.5 and the risk of T2DM is suggestive. The vast majority of studies were conducted in North America or Europe and little evidence was reported from other areas. The evidence on the association between long-term traffic-related exposure (measured by nitrogen dioxide or nitrogen oxides) and the risk of T2DM is also suggestive although most studies were conducted in women. The fact that two primary studies showing significant associations between traffic exposure and incident T2DM were conducted in women’s cohorts and most other studies have reported a significant association only among women suggests that women may be more susceptible to air pollution-related response to T2DM. It is unclear that the stronger associations in women are consequences of sex-related biological differences or gender-related behavioral or social differences [36] which needs further investigation.

Ecological Studies in Relation to Short-Term Exposure

Consistency and Strength

For mortality from T2DM, three studies examined either PM10 or PM2.5: a time-series study from Shanghai, China found a marginal association [20]. In studies done in Montreal, Canada, the earlier study that examined mortality between 1984 and 1993 in which the median concentrations of PM2.5 and PM10 were 28.5 and 14.7 μg/m3 reported a significant association (12% and 13% increases in DM mortality per IQR increase in PM2.5 and PM10, respectively) [18], whereas a more recent study that examined mortality between 1990 and 2003 in which the median PM2.5 concentration was 6.9 μg/m3 found no association [19]. For hospital/emergency admissions, all three studies reported significant associations with PM2.5. Two U.S. studies where PM2.5 concentrations were 9 to 15 μg/m3 reported weak positive associations (0.96% and 2.74% per 10 μg/m3 increase in PM2.5), whereas a time-series study done in Santiago, Chile where PM2.5 concentrations were two-fold higher (the median PM2.5 =31.5 μg/m3) found a 6% increased risk per 10 μg/m3 increase in PM2.5.

Biological Plausibility

For short-term exposure, it is unclear if mortality from diabetes or hospital/emergency admissions to diabetes was due to diabetes-related complications by dysfunctions of serum glucose control or due to acute exacerbation of other pre-existing diseases [16]. Short-term exposure to particulate matters or ozone is known to induce oxidative stress, systemic inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and cardiac autonomic nervous system dysfunction [37], which may lead to insulin dysregulation [38, 39]. A human panel study conducted in Michigan, U.S. found that sub-acute exposure to PM2.5 was associated with reduced metabolic insulin sensitivity as measured by increased HOMA-IR and reduced heart rate variability [12], which supports the plausibility that air pollution, not only long-term but relatively short-term exposure, could influence insulin and glucose homeostasis.

Temporality

The temporality issue in ecological time-series studies has been assured by examining the lagged effects [40]. Nonetheless, most studies explored only short lagged-exposure periods, such as 0 or 1-day lag or a 2-day distributed lag because many previous studies of total and cardiovascular mortality and morbidity reported larger associations with particle exposures at 0 to 2-day lags. Whether short-term air pollution exposure has immediate effects on glucose and insulin functions or more delayed effects remains to be explored in the future.

Causal Inference

We conclude that the evidence is not sufficient to infer a causal relationship of short-term exposure to air pollution and mortality or hospital/emergency admissions to diabetes. Although a few studies suggest potential mechanisms, those are not specific to glucose and insulin actions and direct mechanisms are unknown. Most previous studies examined diabetes mortality and morbidity along with cardiovascular and respiratory outcomes.

CONCLUSION

Our systematic review suggests that the evidence is suggestive to infer causal relationship between fine particle exposure and the risk of T2DM and there is suggestive evidence of the association between traffic-related exposure and incident T2DM especially in women. Because most studies were conducted in North America or in Europe where exposure levels are relatively low, more studies are needed in recently urbanized areas in Asia and Latin America where air pollution levels are much higher and T2DM is an emerging public health concern [41, 42] to increase the power and to determine the dose-response relationships.

Acknowledgments

Sung Kyun Park was supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) K01-ES016587. Additional support was provided by NIEHS Grant P30-ES017885 entitled “Lifestage Exposure and Adult Disease.”

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Sung Kyun Park and Weiye Wang declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

(▪ Of importance)

- 1.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes--2013. Diabetes Care. 2013;36 (Suppl 1):S11–66. doi: 10.2337/dc13-S011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Danaei G, Finucane MM, Lu Y, Singh GM, Cowan MJ, Paciorek CJ, et al. National, regional, and global trends in fasting plasma glucose and diabetes prevalence since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 370 country-years and 2.7 million participants. Lancet. 2011;378(9785):31–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60679-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2224–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61766-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morris AP, Voight BF, Teslovich TM, Ferreira T, Segre AV, Steinthorsdottir V, et al. Large-scale association analysis provides insights into the genetic architecture and pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2012;44(9):981–90. doi: 10.1038/ng.2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Voight BF, Scott LJ, Steinthorsdottir V, Morris AP, Dina C, Welch RP, et al. Twelve type 2 diabetes susceptibility loci identified through large-scale association analysis. Nat Genet. 2010;42(7):579–89. doi: 10.1038/ng.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Willett WC. Balancing life-style and genomics research for disease prevention. Science. 2002;296(5568):695–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1071055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thayer KA, Heindel JJ, Bucher JR, Gallo MA. Role of environmental chemicals in diabetes and obesity: a National Toxicology Program workshop review. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(6):779–89. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu C, Ying Z, Harkema J, Sun Q, Rajagopalan S. Epidemiological and Experimental Links between Air Pollution and Type 2 Diabetes. Toxicol Pathol. 2012;41(2):361–73. doi: 10.1177/0192623312464531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9▪.Rajagopalan S, Brook RD. Air pollution and type 2 diabetes: mechanistic insights. Diabetes. 2012;61(12):3037–45. doi: 10.2337/db12-0190. This review article demonstrates potential biological mechanisms based on previous experimenal studies. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andersen ZJ, Raaschou-Nielsen O, Ketzel M, Jensen SS, Hvidberg M, Loft S, et al. Diabetes incidence and long-term exposure to air pollution: a cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(1):92–8. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brook RD, Jerrett M, Brook JR, Bard RL, Finkelstein MM. The relationship between diabetes mellitus and traffic-related air pollution. J Occup Environ Med. 2008;50(1):32–8. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31815dba70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brook RD, Xu X, Bard RL, Dvonch JT, Morishita M, Kaciroti N, et al. Reduced metabolic insulin sensitivity following sub-acute exposures to low levels of ambient fine particulate matter air pollution. Sci Total Environ. 2013;448:66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen H, Burnett RT, Kwong JC, Villeneuve PJ, Goldberg MS, Brook RD, et al. Risk of incident diabetes in relation to long-term exposure to fine particulate matter in Ontario, Canada. Environ Health Perspect. 2013;121(7):804–10. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1205958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chuang KJ, Yan YH, Chiu SY, Cheng TJ. Long-term air pollution exposure and risk factors for cardiovascular diseases among the elderly in Taiwan. Occup Environ Med. 2011;68(1):64–8. doi: 10.1136/oem.2009.052704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coogan PF, White LF, Jerrett M, Brook RD, Su JG, Seto E, et al. Air pollution and incidence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus in black women living in Los Angeles. Circulation. 2012;125(6):767–72. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.052753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dales RE, Cakmak S, Vidal CB, Rubio MA. Air pollution and hospitalization for acute complications of diabetes in Chile. Environ Int. 2012;46:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dijkema MB, Mallant SF, Gehring U, van den Hurk K, Alssema M, van Strien RT, et al. Long-term exposure to traffic-related air pollution and type 2 diabetes prevalence in a cross-sectional screening-study in the Netherlands. Environ Health. 2011;10:76. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-10-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldberg MS, Burnett RT, Bailar JC, 3rd, Brook J, Bonvalot Y, Tamblyn R, et al. The association between daily mortality and ambient air particle pollution in Montreal, Quebec. 2. Cause-specific mortality. Environ Res. 2001;86(1):26–36. doi: 10.1006/enrs.2001.4243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldberg MS, Burnett RT, Stieb DM, Brophy JM, Daskalopoulou SS, Valois MF, et al. Associations between ambient air pollution and daily mortality among elderly persons in Montreal, Quebec. Sci Total Environ. 2013;463–464:931–42. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.06.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kan H, Jia J, Chen B. The association of daily diabetes mortality and outdoor air pollution in Shanghai, China. J Environ Health. 2004;67(3):21–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim JH, Hong YC. GSTM1, GSTT1, and GSTP1 polymorphisms and associations between air pollutants and markers of insulin resistance in elderly Koreans. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(10):1378–84. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kloog I, Coull BA, Zanobetti A, Koutrakis P, Schwartz JD. Acute and chronic effects of particles on hospital admissions in New-England. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e34664. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23▪.Kramer U, Herder C, Sugiri D, Strassburger K, Schikowski T, Ranft U, et al. Traffic-related air pollution and incident type 2 diabetes: results from the SALIA cohort study. Environmental health perspectives. 2010;118(9):1273–9. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901689. This is the first epidemiologic study that examined long-term air polluiton exposure and incident type 2 diabetes and reported a significant association. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maynard D, Coull BA, Gryparis A, Schwartz J. Mortality risk associated with short-term exposure to traffic particles and sulfates. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115(5):751–5. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pearson JF, Bachireddy C, Shyamprasad S, Goldfine AB, Brownstein JS. Association between fine particulate matter and diabetes prevalence in the U.S. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(10):2196–201. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26▪.Puett RC, Hart JE, Schwartz J, Hu FB, Liese AD, Laden F. Are particulate matter exposures associated with risk of type 2 diabetes? Environmental health perspectives. 2011;119(3):384–9. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002344. This study was conducted in two large prospective cohort studies, the Nurses' Health Study and the Health Professional Follow-up Study, with a long-term follow-up. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raaschou-Nielsen O, Sorensen M, Ketzel M, Hertel O, Loft S, Tjonneland A, et al. Long-term exposure to traffic-related air pollution and diabetes-associated mortality: a cohort study. Diabetologia. 2013;56(1):36–46. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2698-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Teichert T, Vossoughi M, Vierkotter A, Sugiri D, Schikowski T, Schulte T, et al. Association between Traffic-Related Air Pollution, Subclinical Inflammation and Impaired Glucose Metabolism: Results from the SALIA Study. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e83042. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zanobetti A, Franklin M, Koutrakis P, Schwartz J. Fine particulate air pollution and its components in association with cause-specific emergency admissions. Environ Health. 2009;8:58. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-8-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30▪.Brook RD, Cakmak S, Turner MC, Brook JR, Crouse DL, Peters PA, et al. Long-term fine particulate matter exposure and mortality from diabetes in Canada. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(10):3313–20. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2189. This is the largest study (more than 2 millions) conducted using the Canadian census mortality follow-up data and reported a significant association. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Committee IE. International Expert Committee report on the role of the A1C assay in the diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(7):1327–34. doi: 10.2337/dc09-9033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu X, Liu C, Xu Z, Tzan K, Zhong M, Wang A, et al. Long-term exposure to ambient fine particulate pollution induces insulin resistance and mitochondrial alteration in adipose tissue. Toxicol Sci. 2011;124(1):88–98. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu Z, Xu X, Zhong M, Hotchkiss IP, Lewandowski RP, Wagner JG, et al. Ambient particulate air pollution induces oxidative stress and alterations of mitochondria and gene expression in brown and white adipose tissues. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2011;8:20. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-8-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun Q, Yue P, Deiuliis JA, Lumeng CN, Kampfrath T, Mikolaj MB, et al. Ambient air pollution exaggerates adipose inflammation and insulin resistance in a mouse model of diet-induced obesity. Circulation. 2009;119(4):538–46. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.799015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laing S, Wang G, Briazova T, Zhang C, Wang A, Zheng Z, et al. Airborne particulate matter selectively activates endoplasmic reticulum stress response in the lung and liver tissues. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;299(4):C736–49. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00529.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clougherty JE. A growing role for gender analysis in air pollution epidemiology. Environmental health perspectives. 2010;118(2):167–76. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0900994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brook RD, Rajagopalan S, Pope CA, 3rd, Brook JR, Bhatnagar A, Diez-Roux AV, et al. Particulate matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease: An update to the scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121(21):2331–78. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181dbece1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carnethon MR, Golden SH, Folsom AR, Haskell W, Liao D. Prospective investigation of autonomic nervous system function and the development of type 2 diabetes: the Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities study, 1987–1998. Circulation. 2003;107(17):2190–5. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000066324.74807.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meigs JB, Hu FB, Rifai N, Manson JE. Biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 2004;291(16):1978–86. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.16.1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Campbell MJ, Tobias A. Causality and temporality in the study of short-term effects of air pollution on health. International journal of epidemiology. 2000;29(2):271–3. doi: 10.1093/ije/29.2.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Green J, Sanchez S. Air Quality in Latin American: An Overview. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raquel AS, West JJ, Yuqiang Z, Susan CA, Jean-François L, Drew TS, et al. Global premature mortality due to anthropogenic outdoor air pollution and the contribution of past climate change. Environmental Research Letters. 2013;8(3):034005. [Google Scholar]