Abstract

Lon protease is conserved from bacteria to humans and regulates cellular processes by degrading different classes of proteins including antitoxins, transcriptional activators, unfolded proteins, and free ribosomal proteins. Since we found that Lon has several putative cyclic diguanylate (c-di-GMP) binding sites and since Lon binds polyphosphate (polyP) and lipid polysaccharide, we hypothesized that Lon has an affinity for phosphate-based molecules that might regulate its activity. Hence we tested the effect of polyP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), guanosine tetraphosphate (ppGpp), c-di-GMP, and GMP on the ability of Lon to degrade α-casein. Inhibition of in vitro Lon activity occurred for polyP, cAMP, ppGpp, and c-di-GMP. We also demonstrated by HPLC that Lon is able to bind c-di-GMP. Therefore, four cell signals were found to regulate the activity of Lon protease.

Keywords: polyphosphate, cAMP, ppGpp, c-di-GMP, Lon protease

Introduction

Lon is an 87 kDa ATP-dependent protease1 that was first purified in Escherichia coli,2 and it belongs to the AAA+ superfamily of ATPases that are associated with diverse cellular activities.3 Lon is divided into two subfamilies, Lon A and Lon B, and this division is based primarily on the characteristics of their catalytic sites.4 The catalytic domain of Lon assembles into hexameric rings, suggesting that Lon has a hexameric structure.5 In each subunit of this homooligomeric enzyme, there are three functional domains: the N-terminal domain which is involved in substrate recognition and binding, the central ATPase domain, and the C-terminal domain which contains the proteolytic active site.6 Lon degradation generates few free residues as it functions as an endo-protease, cleaving substrates into peptides of 5–20 amino acids.7

Lon is a global regulator which controls several regulatory proteins including HU, a major DNA binding protein;8 SulA, a cell division inhibitor;9 RcsA, a positive regulator for capsule synthesis;10 and several antitoxins (reviewed in Gerdes and Maisonneuve11). Lon also functions as a negative regulator of the type III protein secretion in Pseudomonas syringae12 and degrades naturally unstable proteins as well as misfolded proteins.13

In order to ensure normal cellular processes, Lon must be maintained at appropriate levels. In E. coli as well as Streptomyces lividans, production of Lon from a heterologous promoter results in toxicity.14 Protein substrates stimulate the intrinsic ATPase activity of Lon, and this stimulation is unaffected by mutational inactivation of the proteolytic site (reviewed in Suzuki, et al.7). Protein sequences rich in aromatic residues are recognized by Lon; these sequences are likely hidden in the hydrophobic cores of proteins but accessible in unfolded polypeptides.15 The recognition of these signals results in nanomolar binding, leading to subsequent protein degradation.15 Although Lon is ATP-dependent, Lon has also been shown to respond to other nucleoside triphosphates including GTP, UTP, and CTP, in the hydrolysis of casein, though with less activity than observed with ATP.16

Several compounds such as chloromethyl ketones, fluorophosphates, and sulfonyl fluorides inhibit Lon activity (reviewed in Rotanova, et al.17); however, for several of these inhibitors, 50% inhibition of Lon activity generally requires millimolar concentrations of inhibitor.1 The bacteriophage T4 proteolysis inhibition protein also inhibits Lon protease.18 Recently, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was demonstrated to inhibit the peptidase, protease and ATPase activities of Lon.19 Similar levels of inhibition were observed with mono-phosphoryl and di-phosphoryl lipid, as well as with detoxified LPS and LPS from Salmonella minnesota R595; hence, the phosphate groups in the lipid A domain may be responsible for this inhibitory effect, rather than the O-acyl chain or O antigen polysaccharide. Lon also co-precipitated with LPS using an anti-Lon antibody, thus demonstrating direct binding.19 Furthermore, the evaluation of a series of commercially available peptide-based inhibitors identified the peptidyl boronate MG262 as most potent for inhibiting Lon activity and required binding, but not hydrolysis, of ATP.20

Lon protease forms a complex with polyP.21 Proteins degraded by this polyP-Lon complex include free ribosomal proteins; hence, it has been speculated that adaptation to nutritional downshift is mediated in part by action of polyP in directing the degradation of ribosomal proteins.22 The polyP binding site of Lon is localized in the ATPase domain, and therefore competes with DNA for binding to Lon, completely inhibiting the Lon-DNA complex in the presence of equimolar amount of polyP, suggesting that the proteolytic and DNA-binding activities of Lon are likely controlled by polyP.23 It has been reported that casein hydrolysis by Lon protease is not however affected by polyP.22 Also, both polyP-Lon and DNA-Lon complexes still demonstrate ATPase activity, which has led to the hypothesis that DNA and polyP binding to the DNA-binding domain are dynamic rather than static.23 Lon also binds double-stranded and single-stranded DNA, and the rate of protein degradation is increased by different DNA species, although this effect was not dependent on any sequence specificity.24 DNA also stimulates the ATPase activity of Lon, and can occur in the absence of a proteolytic substrate.25

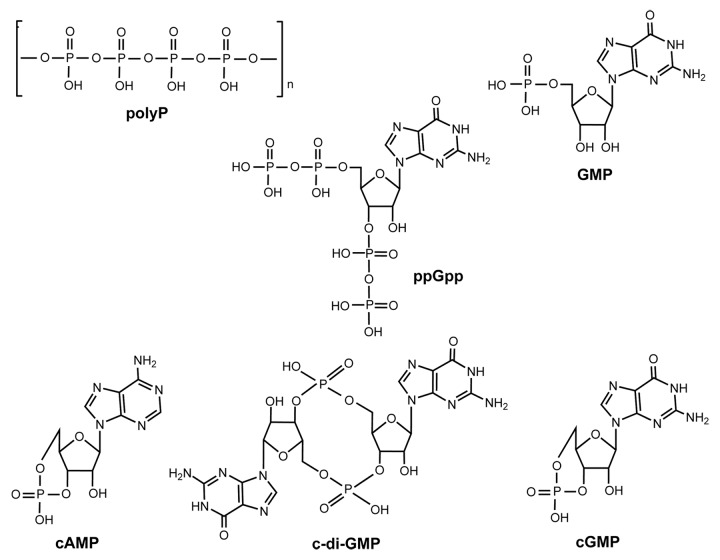

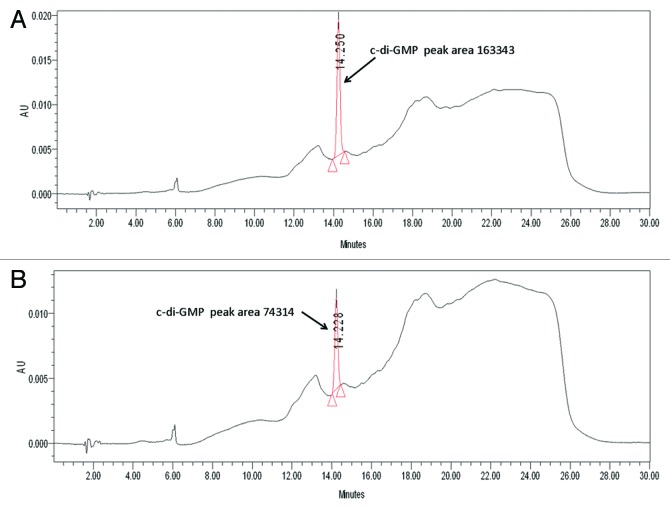

Unexpectedly, we found that the sequence of Lon contains several c-di-GMP putative binding motifs (Fig. 1); there are four RxxxR motifs and one IGSxxG motif (Fig. 1). c-di-GMP is an ubiquitous signal that controls many biological processes including motility, biofilm formation, virulence, and cellular morphology.26 The IGSxxG motif is found in the c-di-GMP binding protein BdcA,27 and in PilZ proteins, the c-di-GMP motifs are RxxxR and (D/N)xSxxG.28 These PilZ-domain-containing proteins bind c-di-GMP with variable affinities (sub-µM to µM), and it has been speculated that receptors with different or degenerate c-di-GMP binding motifs may exist other than the canonical PilZ domain.29 Furthermore, high affinity binding of c-di-GMP by diguanylate cyclases requires an RXXD motif positioned in close proximity to the active site30; this motif is also conserved in PelD, a degenerate diguanylate cyclase receptor that regulates exopolysaccharide production and binds c-di-GMP31 in P. aeruginosa. There is additional evidence suggesting that Lon may bind c-di-GMP in that P. aeruginosa Lon, which is 84% similar to E. coli Lon,32 binds a c-di-GMP analog.33 Therefore, we explored the possibility that E. coli Lon may bind several cell signals that include phosphate (Fig. 2) and that they may affect its activity.

Figure 1. Lon contains c-di-GMP binding motifs. The four RXXXR c-di-GMP-binding motifs which are highly conserved in PilZ-domain containing proteins are shown in yellow. The IGSxxG c-di-GMP-binding motif of BdcA is shown in gray.

Figure 2. Structures of the compounds tested (polyP, ppGpp, GMP, cAMP, c-di-GMP, and cGMP).

Results and Discussion

cGMP, cAMP, ppGpp, and polyP inhibit Lon degradation of α-casein

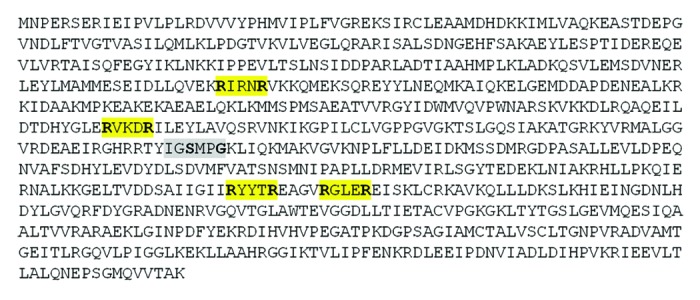

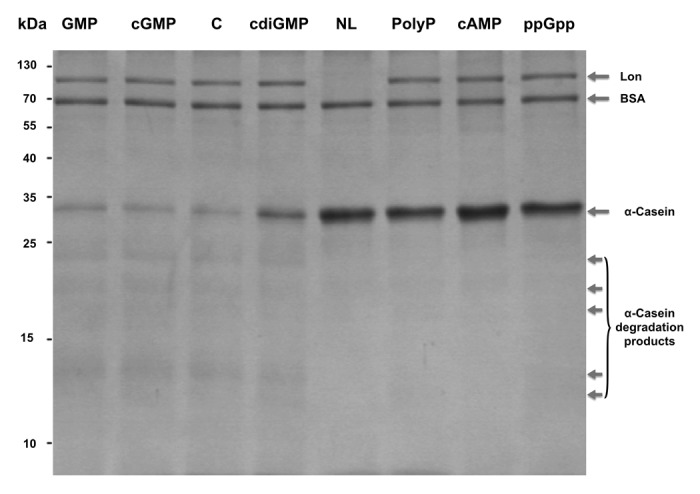

We used α-casein as the reference substrate for Lon due to its high activity on this substrate. Without the addition of the nucleotides or polyP, about 90% of the α-casein was degraded by Lon under these conditions (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Phosphate molecules inhibit Lon’s activity. Casein (6.68 µM) was incubated with Lon (0.19 µM) with 850 µM of GMP, cGMP, c-di-GMP, polyP, cAMP, or ppGpp. Lane C: no phosphate molecule with casein and Lon. Lane NL: no Lon with casein. Samples were incubated for 3 h at 37 °C. BSA (0.68 µM) was added to each reaction.

Given that Lon contains five putative c-di-GMP binding sites, we investigated the impact of c-di-GMP binding on Lon activity along with the impact of the similar phosphate-containing cell signals: polyP, cAMP, cGMP, and ppGpp. GMP was also tested as a control. Degradation of α-casein by Lon was nearly completely inhibited by polyP, cAMP, and ppGpp at 850 µM (Fig. 3). c-di-GMP inhibited Lon activity less (by about 50%). As expected, the Lon degradation products were substantially reduced with polyP, cAMP, and ppGpp (Fig. 3). Similar Lon inhibition was seen at 50 µM and 450 µM for polyP, and 450 µM for c-di-GMP. Since cGMP and GMP did not inhibit the degradation of α-casein, inhibition was not based solely on the presence of a phosphate or guanosine.

The ability of polyP, ppGpp, cAMP, and c-di-GMP to inhibit Lon activity has several physiological implications. PolyP accumulation frequently occurs in response to amino acid starvation; its concentration increases from 700 to 11 000 µM in response to amino acid starvation36 and can reach 20 000 µM in the stationary phase.37 This accumulation is frequently accompanied by increased levels of stringent factors including ppGpp and guanosine pentaphosphate (pppGpp). The steady-state concentration of ppGpp in Escherichia coli is 25 µM, although the minimum concentration required to observe penicillin tolerance by amino acid-deprived E. coli is 621 µM.38 Since nutrition stress increases both polyP and ppGpp, we would expect reduced Lon activity under physiological conditions. However, since polyP promotes the degradation of ribosomal proteins,22 the effect of polyP on Lon activity is probably substrate specific.

The secondary messenger cAMP is used by bacteria to control a variety of processes including motility, virulence, and the utilization of a variety of sugars as well as to control sensor proteins such as the cAMP receptor protein and fumarate nitrate reductase.39 The levels of cAMP under starvation conditions are 20 µM in E. coli40; hence, cAMP likely has no effect on Lon activity under physiological conditions.

The concentration of the secondary message c-di-GMP is 0.10 µM in E. coli41 and 50 µM in P. aeruginosa.42 Hence, it is unlikely that c-di-GMP should affect Lon activity under physiological conditions unless another factor is involved.

c-di-GMP binds Lon

Since Lon has several putative binding sites, we used HPLC to determine if Lon binds c-di-GMP. We found that Lon binds c-di-GMP since after incubation with c-di-GMP; the peak area was decreased by 50% (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Lon binds c-di-GMP. (A) HPLC chromatogram and spectral index of buffer with 30 μM of c-di-GMP. (B) HPLC chromatogram and spectral index of Lon incubated with 30 μM of c-di-GMP.

Increasingly, it is becoming evident that Lon regulation occurs through multiple factors. It is also clear that the phosphate groups of different cofactors can interact with Lon and inhibit its activity, as has been demonstrated with Lipid A.19 The phosphate-rich molecule cardiolipin (phospholipid) selectively binds Lon and inhibits its ATPase and protease functions,43 further highlighting a central role for phosphate-containing molecules in the regulation of Lon activity. Since cGMP and GMP had no effect on the activity of Lon, we can infer that the presence of phosphates is not in itself sufficient for the regulation of Lon. It has been shown that the polyP and DNA-binding sites of Lon are localized in the ATPase domain; hence, polyP competes with DNA for binding to Lon.23 We speculate that the orientation of phosphates on the small molecules and their ability to interact with the ATPase domain is most critical to the regulation of Lon. This ability to interact with the ATPase domain likely explains why despite the similar orientation of the phosphates on cGMP and cAMP, inhibition is not observed with cGMP but is seen with cAMP. The presence of the carbonyl group of cGMP, likely prevents the orientation necessary for interaction with the ATPase domain. It is noteworthy that with the exception of cAMP, phosphate-based inhibitory small molecules (ppGpp, polyP, and c-di-GMP) contain multiple phosphate groups (Fig. 2). Cardiolipin and Lipid A also contain multiple phosphate groups. Taken together, our findings demonstrate that Lon can be inhibited with phosphate-containing small molecules. Since the levels of ppGpp, polyP, cAMP, and c-di-GMP can fluctuate based on environmental factors, we speculate that the inhibitory effect of these nucleotides and polyP might afford the bacteria a way to quickly affect many cellular processes, thus allowing for increased survival and adaptation.

Materials and Methods

In vitro proteolysis assay

The proteolysis reaction was performed based on the method of Kubik et al (2012).34 In brief, 20 µL reaction volumes contained 0.19 µM Lon and 6.68 µM α-casein (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in reaction buffer (40mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.6, 25mM Tris-HCl pH 7.6, 4% w/v sucrose, 4 mM dithiothreitol, 80 μg/ml BSA, 11 mM magnesium acetate, and 4 mM ATP). cGMP (CalBioChem), GMP (Acros Organics), c-di-GMP (BioLog), ppGpp (TriLink BioTechnologies), cAMP (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis), and polyP (Kerafast) were added at 850 μM. Samples were incubated for 3h at 37 °C, the reaction was stopped by the addition of 4× Laemmli buffer, and the reaction products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (gel 15%) with Coomasie Brilliant Blue staining.

HPLC c-di-GMP binding assays

Binding studies were done according to the method of Ma et al.27 In brief, purified His-tagged Lon (30 µM) was incubated with 30 µM c-di-GMP for 0.5 h. Since His-tagged Lon is 89 kDa while c-di-GMP is 0.69 kDa, we used a 10-kDa protein filter unit (EMD Millipore) to separate free and bound c-di-GMP. Samples were run on an HPLC (Waters 2996 Photodiode with 717 plus autosampler) with running buffer A (100 mM KH2PO4, 4 mM tetrabutyl ammonium hydrogen sulfate) and B (75% buffer A, 25% methanol). Peaks were spiked with 5 µM c-di-GMP in order to verify the correct peak.

Expression and purification of Lon protease

Lon was produced from E. coli BW25113/pCA24N-lon by diluting overnight cultures to a turbidity at 600 nm of 0.05 in LB medium and growing to a turbidity of 1.0 at 37 °C. Cultures were induced with 1 mM IPTG for 12 h at 25 °C to induce expression of 6× His-tagged protein.35 Cell lysates were centrifuged and the supernatant was loaded on a His Trap FF Column (GE Healthcare) and the protein purified by AKTA Explorer FPLC (Amersham Biosciences). The activity of Lon produced using this method was found to be the same as that produced at 25 °C.

Supplementary Material

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was disclosed.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH (R01 GM089999). T.K.W. is the Biotechnology Endowed Professor at the Pennsylvania State University.

References

- 1.Goldberg AL, Moerschell RP, Chung CH, Maurizi MR. ATP-dependent protease La (Lon) from Escherichia coli. Methods Enzymol. 1994;244:350–75. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)44027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swamy KH, Goldberg AL. E. coli contains eight soluble proteolytic activities, one being ATP dependent. Nature. 1981;292:652–4. doi: 10.1038/292652a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neuwald AF, Aravind L, Spouge JL, Koonin EV. AAA+: A class of chaperone-like ATPases associated with the assembly, operation, and disassembly of protein complexes. Genome Res. 1999;9:27–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rotanova TV, Melnikov EE, Khalatova AG, Makhovskaya OV, Botos I, Wlodawer A, Gustchina A. Classification of ATP-dependent proteases Lon and comparison of the active sites of their proteolytic domains. Eur J Biochem. 2004;271:4865–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Botos I, Melnikov EE, Cherry S, Tropea JE, Khalatova AG, Rasulova F, Dauter Z, Maurizi MR, Rotanova TV, Wlodawer A, et al. The catalytic domain of Escherichia coli Lon protease has a unique fold and a Ser-Lys dyad in the active site. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:8140–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312243200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsilibaris V, Maenhaut-Michel G, Van Melderen L. Biological roles of the Lon ATP-dependent protease. Res Microbiol. 2006;157:701–13. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suzuki CK, Rep M, van Dijl JM, Suda K, Grivell LA, Schatz G. ATP-dependent proteases that also chaperone protein biogenesis. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:118–23. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(97)01020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonnefoy E, Almeida A, Rouviere-Yaniv J. Lon-dependent regulation of the DNA binding protein HU in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:7691–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.20.7691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ishii Y, Amano F. Regulation of SulA cleavage by Lon protease by the C-terminal amino acid of SulA, histidine. Biochem J. 2001;358:473–80. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3580473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Torres-Cabassa AS, Gottesman S. Capsule synthesis in Escherichia coli K-12 is regulated by proteolysis. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:981–9. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.3.981-989.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerdes K, Maisonneuve E. Bacterial persistence and toxin-antitoxin loci. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2012;66:103–23. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092611-150159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bretz J, Losada L, Lisboa K, Hutcheson SW. Lon protease functions as a negative regulator of type III protein secretion in Pseudomonas syringae. Mol Microbiol. 2002;45:397–409. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosen R, Biran D, Gur E, Becher D, Hecker M, Ron EZ. Protein aggregation in Escherichia coli: role of proteases. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2002;207:9–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goff SA, Goldberg AL. An increased content of protease La, the lon gene product, increases protein degradation and blocks growth in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:4508–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gur E, Sauer RT. Recognition of misfolded proteins by Lon, a AAA+ protease. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2267–77. doi: 10.1101/gad.1670908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chung CH, Goldberg AL. The product of the lon (capR) gene in Escherichia coli is the ATP-dependent protease, protease La. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78:4931–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.8.4931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rotanova TV, Botos I, Melnikov EE, Rasulova F, Gustchina A, Maurizi MR, Wlodawer A. Slicing a protease: structural features of the ATP-dependent Lon proteases gleaned from investigations of isolated domains. Protein Sci. 2006;15:1815–28. doi: 10.1110/ps.052069306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skorupski K, Tomaschewski J, Rüger W, Simon LD. A bacteriophage T4 gene which functions to inhibit Escherichia coli Lon protease. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:3016–24. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.7.3016-3024.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sugiyama N, Minami N, Ishii Y, Amano F. Inhibition of Lon protease by bacterial lipopolisaccharide (LPS) though inhibition of ATPase. Adv. Biosci. Biotechnol. 2013;4:590–8. doi: 10.4236/abb.2013.44077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frase H, Hudak J, Lee I. Identification of the proteasome inhibitor MG262 as a potent ATP-dependent inhibitor of the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium Lon protease. Biochemistry. 2006;45:8264–74. doi: 10.1021/bi060542e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuroda A. A polyphosphate-lon protease complex in the adaptation of Escherichia coli to amino acid starvation. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2006;70:325–31. doi: 10.1271/bbb.70.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuroda A, Nomura K, Ohtomo R, Kato J, Ikeda T, Takiguchi N, Ohtake H, Kornberg A. Role of inorganic polyphosphate in promoting ribosomal protein degradation by the Lon protease in E. coli. Science. 2001;293:705–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1061315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nomura K, Kato J, Takiguchi N, Ohtake H, Kuroda A. Effects of inorganic polyphosphate on the proteolytic and DNA-binding activities of Lon in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:34406–10. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404725200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chung CH, Goldberg AL. DNA stimulates ATP-dependent proteolysis and protein-dependent ATPase activity of protease La from Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79:795–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.3.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Charette MF, Henderson GW, Doane LL, Markovitz A. DNA-stimulated ATPase activity on the lon (CapR) protein. J Bacteriol. 1984;158:195–201. doi: 10.1128/jb.158.1.195-201.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Römling U, Galperin MY, Gomelsky M. Cyclic di-GMP: the first 25 years of a universal bacterial second messenger. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2013;77:1–52. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00043-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma Q, Yang Z, Pu M, Peti W, Wood TK. Engineering a novel c-di-GMP-binding protein for biofilm dispersal. Environ Microbiol. 2011;13:631–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02368.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benach J, Swaminathan SS, Tamayo R, Handelman SK, Folta-Stogniew E, Ramos JE, Forouhar F, Neely H, Seetharaman J, Camilli A, et al. The structural basis of cyclic diguanylate signal transduction by PilZ domains. EMBO J. 2007;26:5153–66. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li T-N, Chin K-H, Fung K-M, Yang M-T, Wang A-H, Chou S-H. A novel tetrameric PilZ domain structure from xanthomonads. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22036. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Christen B, Christen M, Paul R, Schmid F, Folcher M, Jenoe P, Meuwly M, Jenal U. Allosteric control of cyclic di-GMP signaling. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:32015–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603589200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whitney JC, Colvin KM, Marmont LS, Robinson H, Parsek MR, Howell PL. Structure of the cytoplasmic region of PelD, a degenerate diguanylate cyclase receptor that regulates exopolysaccharide production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:23582–93. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.375378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Breidenstein EBM, Janot L, Strehmel J, Fernandez L, Taylor PK, Kukavica-Ibrulj I, Gellatly SL, Levesque RC, Overhage J, Hancock REW. The Lon protease is essential for full virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS One. 2012;7:e49123. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Düvel J, Bertinetti D, Möller S, Schwede F, Morr M, Wissing J, Radamm L, Zimmermann B, Genieser H-G, Jänsch L, et al. A chemical proteomics approach to identify c-di-GMP binding proteins in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Microbiol Methods. 2012;88:229–36. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2011.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kubik S, Wegrzyn K, Pierechod M, Konieczny I. Opposing effects of DNA on proteolysis of a replication initiator. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:1148–59. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ueda A, Wood TK. Connecting quorum sensing, c-di-GMP, pel polysaccharide, and biofilm formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa through tyrosine phosphatase TpbA (PA3885) PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000483. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuroda A, Ohtake H. Molecular analysis of polyphosphate accumulation in bacteria. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2000;65:304–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuroda A, Kornberg A. Polyphosphate kinase as a nucleoside diphosphate kinase in Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:439–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodionov DG, Ishiguro EE. Direct correlation between overproduction of guanosine 3′,5′-bispyrophosphate (ppGpp) and penicillin tolerance in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4224–9. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.15.4224-4229.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gomelsky M. cAMP, c-di-GMP, c-di-AMP and now cGMP: bacteria use them all! Mol Microbiol. 2011;79:562–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07514.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cotta MA, Wheeler MB, Whitehead TR. Cyclic AMP in ruminal and other anaerobic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;124:355–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Simm R, Morr M, Remminghorst U, Andersson M, Römling U. Quantitative determination of cyclic diguanosine monophosphate concentrations in nucleotide extracts of bacteria by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Anal Biochem. 2009;386:53–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2008.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barraud N, Schleheck D, Klebensberger J, Webb JS, Hassett DJ, Rice SA, Kjelleberg S. Nitric oxide signaling in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms mediates phosphodiesterase activity, decreased cyclic di-GMP levels, and enhanced dispersal. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:7333–42. doi: 10.1128/JB.00975-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Minami N, Yasuda T, Ishii Y, Fujimori K, Amano F. Regulatory role of cardiolipin in the activity of an ATP-dependent protease, Lon, from Escherichia coli. J Biochem. 2011;149:519–27. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvr036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.