Abstract

Despite the essential functions of melanin pigments in diverse organisms and their roles in inspiring designed nanomaterials for electron transport and drug delivery, the structural frameworks of the natural materials and their biomimetic analogs remain poorly understood. To overcome the investigative challenges posed by these insoluble heterogeneous pigments, we have used L-tyrosine or dopamine enriched with stable 13C and 15N isotopes to label eumelanins metabolically in cell-free and Cryptococcus neoformans cell systems and to define their molecular structures and supramolecular architectures. Using high-field two-dimensional solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), our study directly evaluates the assumption of structural commonality between synthetic melanin models and the corresponding natural pigments, demonstrating a common indole-based aromatic core in the products from contrasting synthetic protocols for the first time.

Keywords: Melanin, Cryptococcus neoformans, NMR spectroscopy, Structural Biology, Amorphous materials

Introduction

Eumelanins, ubiquitous pigments that play protective roles in animals, plants, and fungi,1 also guide the development of organic nanomaterials with tailored conductive and radical scavenging performance2–5 and have applications to soil bioremediation.6 Moreover, eumelanins are associated with virulence of fungal pathogens in humans and food crops; these pigments have been implicated in human drug resistance and neuronal degeneration.1,7 A related group of bioinspired polydopamine coating materials is emerging as drug delivery vehicles, cell adhesion modulators, and biosensors for drug discovery.8 Despite this versatile range of important functions, the insoluble amorphous physical characteristics of eumelanins have impeded efforts to delineate their molecular structures or to critically evaluate the suitability of related synthetic materials as model systems for intact natural pigments with diverse capabilities.9

Degradative chemical methods have been employed to identify and quantify the relative proportions of 5,6-Dihydoxyindole (DHI) and 5,6-Dihydroxyindole-2-carboxylic acid (DHICA) as the likely indole-based building blocks of eumelanins.9–11 However, diverse linear crosslinked heteropolymers12 or stacked oligomers13,14 can be assembled from just these two monomers in their various tautomeric and redox states to form intractable amorphous melanin pigments; either polymer or oligomer arrangements are expected to produce heterogeneous supramolecular structures that can include chemically similar units.15 For instance, the currently favoured oligomer models are supported by density functional theory (DFT) but fall short of unique fits to the available physical data or satisfactory accounting for the broad UV-Vis absorbance and humidity-dependent conductivity of the biopolymers.15,16 Although synthetic melanins have been implicitly assumed to serve as good models for pigments from natural sources,9,11,17 their structural concordance to natural melanins has never been demonstrated directly. Thus, direct molecular and supramolecular information on intact pigments should be of significant value, particularly if obtained for mature melanins produced from defined small-molecule precursors. Such strategies can substantially advance efforts to delineate the formation mechanisms and structural prerequisites of biomaterials that are versatile enough to absorb UV light, bind metals, tailor surfaces for drug resistance, and alter microbial virulence.

Cryptococcus neoformans (CN) is an unusual human pathogenic fungus that forms eumelanins only in the presence of exogenous catecholamine compounds that are oxidatively polymerized by the action of laccase.18 The requirement of obligatory catecholamine precursors makes CN a natural platform for generating well-defined eumelanins biosynthetically because it ensures that all melanin products are assembled in the fungal cells from known catecholamine substrates.19,20 This requirement also allows us to introduce stable isotope labels that serve as exquisitely sensitive NMR spectroscopic probes of molecular architecture in natural eumelanins.21,22 Importantly, the feasibility of making pigments using structurally related catecholamines and different enzyme catalysts under both cell-free conditions and in fungal cells allows us to test how the outcome of melanin formation depends on these controlling factors.

Both solid-state and swelled-solid NMR have been used primarily to deduce the carbon-based functional moieties present in CN eumelanins20–22 and related melanin pigments.10,23–30 However, nitrogen-based structural information has been sparsely defined for the intact pigments; neither molecular frameworks nor supramolecular organization have been compared systematically for related synthetic and natural eumelanins. Our ability to understand and use eumelanins in bioinspired materials science also remains seriously limited due to the paucity of information about how nitrogenous aromatic compounds build a heterogeneous natural pigment core.

Using isotopically enriched L-tyrosine or dopamine precursors in conjunction with high-field solid-state 13C and 15N NMR of their melanin products, we report the functional groups and, for the first time, the pairwise proximities that define essential features of the carbon-nitrogen molecular framework in intact solid eumelanins. The pigments made by both enzyme-catalyzed chemical polymerization and cell-mediated fungal biosynthesis are shown to possess a common indole-based aromatic core including several magnetically distinct structural frameworks, allowing critical comparison with prior computational and degradative analyses. The current investigation furthers our understanding of the structural arrangements that are prevalent in intact melanins made from indole- and pyrrole-based aromatic building blocks, shedding fresh light on the supramolecular architecture of this important class of enigmatic biomaterials.

Experimental Section

Chemical synthesis of melanins

Chemical reactions were conducted with [U-13C,15N]-L-tyrosine (Cambridge Isotope Labs, Andover, MA), 15N-L-tyrosine (Cambridge), L-tyrosine (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO), L-dopa (Sigma), dopamine (Sigma), and [U-13C,15N]-dopamine precursors (Medical Isotopes, Inc., Pelham, NH) in separate experiments. Other chemicals were purchased from Sigma, unless otherwise stated.

Tyrosinase-mediated oxidative autopolymerization was carried out to form melanin under cell-free conditions essentially as described previously.31–33 Briefly, 2.5 mmol of precursor in 100 mL of pH 7.4 sodium phosphate buffer containing 4 mL tyrosinase (667 units/mL) and 1 mL catalase (592 units/mL) was covered with punctured aluminum foil to permit aeration at room temperature (~22 °C) and to avoid extensive oxidation of the developing pigment from peroxide ions generated in the active site of the tyrosinase enzyme. After 72 hours of mechanical stirring, the reaction mixture was acidified to ~pH 1 with 6 M HCl and placed in a boiling water bath for 20 min. The solid pigment was separated by centrifugation at 9000 rpm and 25 °C for 15 min, then washed repeatedly by removing the supernatant after centrifugation and adding distilled water until the pH reached ~7. The precipitate was transferred to a Falcon tube covered with punctured parafilm, frozen using liquid nitrogen, and lyophilized. Upon removal of the sample from the lyophilizer, the sample container was sealed immediately and stored at 4 °C.

The tyrosinase-mediated oxidative process was conducted in the absence of catalase to test the effects of the latter enzyme on generation of melanin pigments under cell-free conditions. Melanins were also produced by autopolymerization of natural abundance L-dopa using published methods31–33 as described above but in the absence of the tyrosinase enzyme. The reaction mixtures contained 2.5–5 mmol of L-dopa precursor in 100 mL Tris-HCl (sodium phosphate) buffer at pH 7.4 were covered with punctured aluminum foil to allow for aeration at room temperature (~22 °C). The final products were purified as described above.

CN melanin biosynthesis

Fungal melanins were biosynthesized from the precursors described above using the serotype D 24067 strain of Cryptococcus neoformans (American Type Culture Collection 208821) and isolated for biophysical study using chemical protocols that solubilize other cellular components.20,34–36 Cells were grown in a 1 mM solution of an obligatory melanin precursor in chemically defined media (29.4 mM KH2PO4, 15 mM D-glucose, 13 mM glycine, 10 mM MgSO4, and 3 μM thiamine at 30 °C) for 10 days at 150 rpm in a rotatory shaker. Either unlabeled or [U-13C]-glucose were used in separate experiments. Cell pellets obtained by centrifugation at 2000 rpm were washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS); the isolated fungal cells were suspended in 1.0 M sorbitol/0.1 M pH 5.5 sodium citrate solutions and incubated with 10 mg/mL lysing enzymes (from Trichoderma harzianum) for 24 h at 30 °C to remove cell walls. After centrifugation at 2000 rpm for 10 mins, the pellet (melanized protoplasts) was washed several times with PBS until the supernatant was nearly clear. To denature proteinaceous components, a 20 mL aliquot of 4.0 M guanidine thiocyanate was added to form a suspension that was incubated for 12 h at room temperature in a rocker (Shaker 35, Labnet, Woodbridge, NJ). The cell debris was collected and washed 2–3 times with ~20 mL PBS and incubated for 4 h at 65 °C in 5 mL of buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 5 mM CaCl2, 5% SDS) containing 1 mg/mL proteinase K (Boehringer Mannheim, Germany). The recovered cell debris was washed 2–3 times with ~20 mL PBS, then subjected to Folch lipid extraction37 while maintaining the proportions of chloroform, methanol, and saline solution in the final mixture as 8:4:3. After three delipidations, the final product was suspended in 20 mL of 6 M HCl and boiled for 1 h to hydrolyze cellular contaminants associated with melanin. The black particles of interest that survived HCl treatment were dialyzed against distilled water for 14 d with daily water changes. The resulting melanin particles (‘ghosts’) were lyophilized for further biophysical analysis.

Solid-State NMR

Either of two instruments was used for 13C and 15N solid-state cross polarization – magic-angle spinning (CPMAS) NMR measurements: a Varian (Agilent) VNMRS NMR spectrometer operating at a 1H frequency of 600 MHz with a 1.6-mm HXY fastMAS probe equipped to hold 2–6 mg of powdered samples and spinning typically at 15 kHz (±20 Hz) (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA); or a Bruker Avance II spectrometer operating at a 1H frequency of 750 MHz with 3.2 mm HCN or 3.2 mm E–free HCN probes containing 6–16 mg of powdered samples and spinning typically at 10–20 kHz (±5 Hz) (Bruker BioSpin Corp., Billerica, MA). All data were collected at spectrometer-set temperatures of 25 °C. Typical 90° pulse lengths for 1H were ~2.5 μs for the Bruker HCN probe and ~3 μs for the E-free HCN probe; 13C and 15N 90° pulse lengths were ~5 μs and ~6 μs, respectively, for the 3.2 mm HCN probes. For the 1.6-mm Varian HXY fastMAS probe, the typical 1H 90° pulse length was ~1.2 μs; 13C and 15N 90° pulse lengths were ~1.3 μs and ~2.65 μs, respectively. Spectral datasets were processed with 50–200 Hz of line broadening; chemical shifts were referenced externally to the methylene (-CH2-) group of adamantane (Sigma) at δC=38.48 ppm38 or calculated from 15N and 13C gyromagnetic ratios by IUPAC-specified procedures.39

For 1D 13C CPMAS NMR using the 3.2-mm Bruker probes, typical 1–2 ms cross polarization times with ~20–50% linearly ramped rf field strengths40 for 1H and a ~50 kHz constant rf field for 13C were used to transfer magnetization from 1H to 13C nuclear spin baths. High-power heteronuclear proton decoupling (80–100 kHz) was achieved using the two-pulse phase modulated (TPPM) composite pulse sequence,41 and recycle delays of 3 s were inserted between successive acquisitions. For the 1.6-mm Varian probe, high-power heteronuclear 1H decoupling (175–185 kHz) was achieved using the small phase incremental alternation (SPINAL) pulse sequence42 and acquisition was done with a 3 s recycle delay.

1D 15N CPMAS spectra were also recorded with ramped cross polarization, using 1–3 ms cross polarization times, recycle delays of 2–3 s, and 80–100 kHz 1H decoupling. Typical experimental parameters on the Bruker spectrometer were as follows: 1H 90° pulse duration, ~3 μs; 15N 90° pulse duration, 4–6 μs; 1H-15N cross polarization time, 1–3 ms; sweep width, 25–50 kHz; acquisition time, 10 ms; data points, 2048; number of transients, 128–10,000 for 15N-enriched pigments. Typical experimental parameters on the Varian spectrometer were as follows: 1H 90° pulse duration, 2.3 μs; 15N 90° pulse duration, 2.65 μs; sweep width, 50 kHz; acquisition time, 50 ms; data points, 2500; number of transients, 1024–4096.

15N-13C spin correlations were obtained using double CP-based (DCP) measurements43,44 with the Bruker 750 MHz spectrometer and HCN probe. The 2D 15N-13C DCP correlation spectra were collected with a 1–3 ms initial 1H → 15N CP step and a 3–4 ms 15N → 13C CP step; MAS rates of 15–23 kHz were used in separate experiments. TPPM 1H decoupling with an rf field strength corresponding to 80–100 kHz was applied during acquisition. For 2D DCP measurements on CN dopamine melanin pigments, typical experimental parameters were as follows: spectral width for 13C, 75 kHz; spectral width for 15N, 25 kHz; number of scans (direct dimension), 1536; number of points (indirect dimension), 32; three identical data sets (each ~24 hr) co-added to produce the final DCP spectra. For 2D DCP measurements on synthetic melanin pigments derived from the [U-13C,15N] L-tyrosine precursor, typical experimental parameters were as follows: spectral width for 13C, 75 kHz; spectral width for 15N, 25 kHz; number of scans (direct dimension), 1024; number of points (indirect dimension), 128; two identical data sets (each ~22 hr) co-added to produce the final DCP spectra.

15N-13C correlations were confirmed with Proton Assisted Insensitive Nuclear Cross-Polarization (PAIN-CP) experiments, which reduce dipolar truncation and hence favor the observation of long distance contacts.45,46 A Bruker Avance II spectrometer operating at a 1H frequency of 900 MHz and equipped with a 3.2-mm HXY E-free probe spinning at 20 kHz was used for these measurements. 2D PAIN-CP spectra of the isotopically enriched synthetic melanin pigments were recorded with a spectral width of ~103 kHz in the direct dimension (13C) and ~45.6 kHz in the indirect dimension (15N); other parameters included 512 transients (direct dimension), 2048 points in the direct dimension (13C), and 64 points in the indirect dimension (15N).

For 2D 13C–15N spectral data, acquisition times in the indirect dimension were chosen to limit the total experiment times to 1–3 days; additional resolution was not available by acquiring more data points because signal decay was complete and the sweep width exceeded the spectral window with the selected parameters. An exponential apodization function with 200–400 Hz line broadening was used for the direct-detected dimension, and an exponential apodization function with 100–200 Hz line broadening was applied for the indirect dimension. Identical 1D spectra were observed before and after lengthy 2D NMR experiments, verifying the melanin sample stability.

Results and Discussion

13C and 15N NMR Comparisons of Synthetic and Fungal Melanins

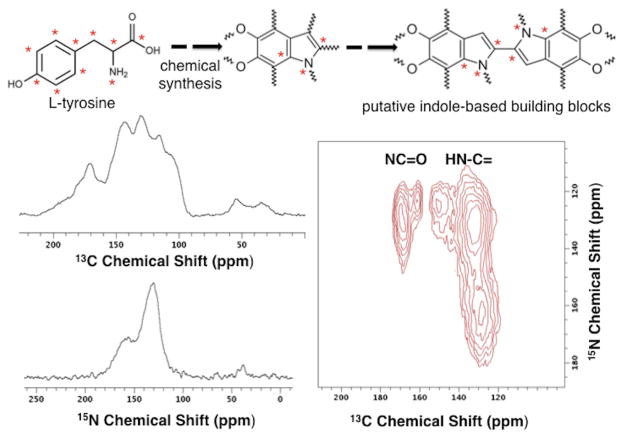

Shown in Figure 1 are the first 13C and 15N CPMAS NMR spectra reported for melanin pigments derived from [U-13C,15N]-L-tyrosine by cell-free enzyme-catalyzed polymerization. Comparable 150 MHz one-dimensional (1D) 13C spectra (Figure S1) and the expected EPR activity20 are obtained whether this pigment is made from L-tyrosine or L-dopa, supporting previously reported tyrosinase-mediated oxidation from L-tyrosine to L-dopa during the polymerization process.7 Both synthetic pigments display aromatic regions (110–160 ppm) similar to CN melanins derived from the obligatory exogenous L-dopa precursor,20–22 providing preliminary indications of a common heterogeneous amorphous aromatic core structure in the (natural-abundance) synthetic and fungal melanin pigments. 13C NMR spectra for the isotopically enriched materials are dominated by partially resolved arene (and/or alkene) resonances consistent with proposed indole-based aromatic ring structures,12,24,26 but additional spectral features are evident from carboxyl groups (168–174 ppm) and open-chain aliphatics (30–60 ppm) as reported for solid fungal melanins20–23,27 and the polydopamines discussed below.30 When compared with the L-tyrosine or natural abundance L-dopa starting materials, these polymerized products show 1D 13C NMR spectra with broad features attributable to superposition of chemically and magnetically similar structural units and also to the presence of stable free radicals.47,48

Figure 1.

Left: One-dimensional solid-state CPMAS 13C (top) and 15N (bottom) NMR spectra of synthetic [U-13C,15N]-L-tyrosine melanin obtained at a 1H operating frequency of 750 MHz and spinning rate of 23 kHz. Provisional 13C resonance assignments appear in the Results section. Right: Two-dimensional 13C-15N double cross polarization (DCP) NMR43 contour diagram of synthetic [U-13C,15N]-L-tyrosine melanin, obtained with a spinning speed of 23 kHz. The cell-free reactions, for which the isotopic labeling scheme and a possible indole-based structural unit are illustrated, were catalyzed by tyrosinase.

The 75 MHz 15N NMR spectrum of isotopically enriched L-tyrosine melanin shown in Figure 1 offers the highest resolution view to date of the nitrogen-based pigment architecture, surpassing natural-abundance spectra of synthetic L-dopa melanins and natural pigments from fungal sources.24,27 In conformance with these prior reports, our synthetic L-tyrosine melanin displays aromatic resonances at ~130 and ~157 ppm, consistent with a pyrrole within an indole unit and a free pyrrole structure, respectively.30 These results strengthen our 13C-based hypothesis of a common indole-based aromatic core in melanins formed by fungal biosynthesis or derived from cell-free synthesis using alternative L-tyrosine or L-dopa precursors: a common or similar aromatic framework develops by autopolymerization and when the reaction is mediated by tyrosinase or laccase. The observed 15N chemical shifts (Figures 1 and S1) are also in accord with reports for melanin from Sepia officinalis and human hair,28 polydopamines,30 and tryptophan derivatives.49 However, the prominent aliphatic amine resonances reported previously in other pigment samples24,27,30 are absent from our 15N L-tyrosine melanin spectra, suggesting that the open-chain aliphatic 13C NMR features exhibited by our melanins do not arise from uncyclized amino acid or catecholamine products.

Two-Dimensional NMR to Delineate Pairwise 13C-15N Proximities in Synthetic and Fungal Melanins

Both the resolution and structural information content of the 1D spectra are improved substantially by the two-dimensional (2D) NMR contour plot of Figure 1, which discriminates among the carbonaceous functional groups by their chemical shifts and reveals which 13C nuclei are located within ~4.5–5 Å of particular 15N partners. Thus, rather than using a collection of observed 13C and 15N chemical shifts to deduce plausible building blocks, double cross polarization43 (DCP) experiments on [U-13C,15N]-L-tyrosine melanin provide direct spectroscopic verification of nearby dipolar-coupled 13C-15N pairs present in the pigment structure. These results, which are confirmed by Proton Assisted Insensitive Nuclei Cross Polarization (PAIN-CP)45 methods (Figure S2), constitute the first direct assessment of nitrogen-containing molecular architecture in a melanin pigment. Such powerful heteronuclear correlation strategies have been used only rarely in non-crystalline solids,50 which typically display compromised cross polarization efficiency and limited spectral resolution.

For eumelanin derived from L-tyrosine, the overlapped 1D 13C NMR aromatic core spectral pattern (110–160 ppm) is augmented by a 2D contour plot that reveals five 13C-15N spatially proximal spin pairs, including four chemically distinguishable carbons and three nitrogens. The nearby 13C-15N pairs correspond to cross-peaks at (130, 163), (130, 132), (152, 125), (163, 125), and (168, 132) ppm, indicating the covalent and associative architectural possibilities for intact melanin biopolymer assemblies. For instance, the carboxyl carbon (168 ppm) and several types of arene carbons (130, 152, and 163 ppm) are each close in space to one of the two types of indole nitrogens that appear in the 15N spectrum at 125 and 132 ppm, respectively, providing direct support for aromatic building blocks similar to and/or developed from DHICA as well as DHI structural units in the fully formed melanin structure.7,9 Conversely, only the arene carbons at ~130 ppm are proximal to the 163-ppm pyrrole nitrogens, consistent with oxidative cleavage of the DHI-based aromatic units that predominate in synthetic melanins7 and polydopamines.30 Although the observed pairwise 13C-15N interactions could also result from oligomer stacking with interlayer distances of 3.1–3.4 Å deduced from DFT calculations,16 we expected the numerous shorter indole covalent bonds to dominate the observed DCP spectral connectivities. Given the concordance of 1D 13C CPMAS spectra for synthetic L-tyrosine melanin and CN L-dopa melanin, similar structural constraints are expected to characterize the fungal pigment.

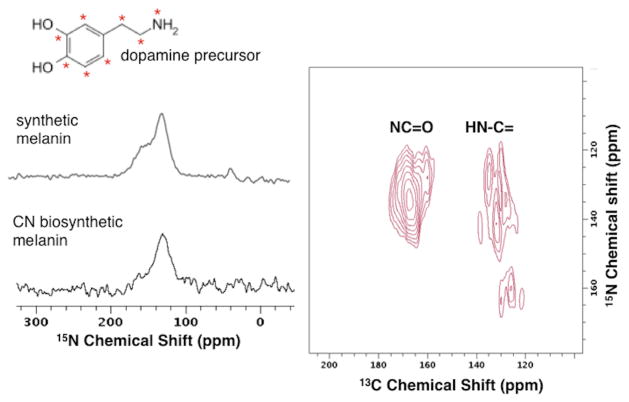

1D and 2D NMR for Structures of Synthetic and Fungal Polydopamine Melanins

Finally, the potential of solid-state NMR for investigations of melanin molecular architecture is aptly illustrated for a series of EPR-active pigments derived from a dopamine precursor by laccase-mediated catalysis in the CN fungal cells. Figures 2 and S3 illustrate the similarity of 1D 15N CPMAS NMR signatures for synthetic and CN [U-13C,15N]-dopamine melanins, again supporting a common aromatic core and reinforced by 1D 13C CPMAS spectra with similar aromatic features (but distinctive aliphatic resonances in the 0–50 ppm region)5,51 (Figure S3). In addition to the major resonances at ~130 and ~157 ppm observed for other melanins,24,27,28 the 15N NMR spectra of our dopamine pigments confirm a modest 30-ppm peak assigned previously to amines.30 The similarity of aromatic core structures in fungal and synthetic pigments is underscored by comparison with the 2D DCP spectrum of [U-13C,15N]-dopamine CN melanin shown in Figure 2, which replicates the cross-peak pattern and major pairwise nuclear spin proximities of the synthetic [U-13C,15N]-tyrosine pigment (Figure 1). No nearby 13C-15N pairs involving the [U-13C]-glucose taken up by the cellular medium are evident in the current DCP spectrum. Thus, though this latter 2D NMR result extends the finding of common indole-based core architectures from L-tyrosine and natural-abundance L-dopa precursors to the dopamine neurotransmitter, distinctive spectral features consistent with uncyclized amine-terminated sidechains30 are also revealed for polydopamine.

Figure 2.

Left: One-dimensional solid-state CPMAS 15N NMR spectra of [U-13C,15N]-dopamine synthetic and CN melanins obtained at 1H operating frequencies of 600 MHz and 750 MHz, respectively, and a spinning rate of 15 kHz. Right: Two-dimensional 13C-15N double cross polarization (DCP) NMR43 contour diagram of [U-13C,15N]-dopamine CN melanin produced in [U-13C]-glucose media, obtained at a 1H operating frequency of 750 MHz with a spinning speed of 10 kHz. The cell-free reaction was catalyzed by tyrosinase in the presence of catalase.

Conclusions

Our 13C and 15N solid-state NMR results demonstrate for the first time that cell-free polymerization of L-tyrosine or L-dopa produces melanins with a common indole-based aromatic core structure in the intact melanin pigments. The indole-related spectral signature is also evident for intact synthetic dopamine and natural-abundance L-dopa CN melanins, thus supporting the development of a similar aromatic pigment core from these three precursors – regardless of whether tyrosinase or laccase catalysts are used and whether the reactions are mediated by fungal cells. Whereas these NMR studies indicate the suitability of the synthetic models for aromatic structural units of the natural pigments, they also reveal distinctive aliphatic moieties depending on how the pigments are formed.

Each reaction pathway produces a heterogeneous, amorphous pigment, and the CN melanins can also bind to cell-wall components.20,22 The 13C-15N dipolar interaction patterns are strikingly similar for the synthetic L-tyrosine melanins and CN dopamine pigments. Both DCP and PAIN-CP NMR spectra of the intact pigments (Figures 1 and S2) implicate structural moieties consistent with previously reported DHICA and DHI degradation products.7,9,11 Additional open-chain aliphatic carbons that could arise from unreacted L-dopa are evident in both synthetic and CN melanins; aliphatic amine structural elements proposed to arise from coupling of dopamine and/or quinone structural units30 are found uniquely in the dopamine melanins. Our observation of four distinct indole-like/indole-based 13C-15N pairs supports multiple modes of polymeric assembly for this pigment class. In the context of prior computational and experimental evidence arguing in favor of stacked oligomers,13,14 the distinct proximal pairwise interactions revealed by our 2D NMR measurements independently demonstrate spatial connectivities that likely result from multiple polymerization pathways contributing to the formation of amorphous, heterogeneous natural and synthetic eumelanins. These atomic-level structural comparisons of intact melanins produced from well-defined precursors set the stage for controlling the development of natural protective pigments and engineering biomaterials for human therapeutics, photoprotection, and environmental remediation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH R01-AI052733). The 600 MHz NMR facilities used in this work are operated by The City College and the CUNY Institute for Macromolecular Assemblies, with additional infrastructural support provided by NIH 2G12 RR03060 from the National Center for Research Resources and 8G12 MD007603 from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health. R.E.S. is a member of the New York Structural Biology Center (NYSBC). The 750 MHz NMR experiments conducted at the NYSBC are made possible by a grant from the New York State Office of Science, Technology, and Academic Research.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Authors’ contributions

S.C. and B.I. designed, conducted, and analyzed the NMR experiments; R.P.R. prepared the fungal melanins; S.T. and S.C. prepared the synthetic melanins; all authors discussed the results and contributed to manuscript preparation; A.C., R.E.S., and S.C exercised project oversight and wrote the manuscript.

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Solid-state NMR spectra including 1D CPMAS 13C NMR of melanins from L-tyrosine and L-dopa, 2D 13C-15N PAIN-CP NMR of synthetic [U-13C, 15N]-L-tyrosine melanin, and CPMAS 13C NMR spectra of synthetic and CN dopamine melanins. See DOI: 10.1039/b000000x/

Notes and references

- 1.Eisenman HC, Casadevall A. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;93:931–940. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3777-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meredith P, Bettinger CJ, Irimia-Vladu M, Mostert AB, Schwenn PE. Rep Prog Phys. 2013;76:034501. doi: 10.1088/0034-4885/76/3/034501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Panzella L, Gentile G, D’Errico G, Della Vecchia NF, Errico ME, Napolitano A, Carfagna C, D’Ischia M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:12684–12687. doi: 10.1002/anie.201305747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simon JD, Peles DN. Accts Chem Res. 2010;43:1452–1460. doi: 10.1021/ar100079y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ju KY, Lee Y, Lee S, Park SB, Lee JK. Biomacromolecules. 2011;12:625–632. doi: 10.1021/bm101281b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buszman E, Pilawa B, Witoszy T. Appl Magn Reson. 2003;24:401–407. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ito S. Pig Cell Res. 2003;16:230–236. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0749.2003.00037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lynge ME, van der Westen R, Postma A, Städler B. Nanoscale. 2011;3:4916–4928. doi: 10.1039/c1nr10969c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.d’Ischia M, Napolitano A, Pezzella A, Meredith P, Sarna T. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:3914–3921. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crescenzi O, Kroesche C, Hoffbauer W, Jansen M, Napolitano A, Prota G, Peter MG. Liebigs Ann Chem. 1994:563–567. [Google Scholar]

- 11.d’Ischia M, Wakamatsu K, Napolitano A, Briganti S, Garcia-Borron J-C, Kovacs D, Meredith P, Pezzella A, Picardo M, Sarna T, Simon JD, Ito S. Pig Cell Melan Res. 2013;26:616–633. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prota G. Melanins and Melanogenesis. Academic Press; San Diego: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zajac G, Gallas J, Cheng J, Eisner M, Moss S, Alvarado-Swaisgood A. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1199:271–278. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(94)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng J, Moss S, Eisner M. Pig Cell Res. 1994;7:255–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.1994.tb00060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meredith P, Sarna T. Pig Cell Res. 2006;19:572–594. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.2006.00345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meng S, Kaxiras E. Biophys J. 2008;94:2095–2105. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.121087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simon JD, Peles D, Wakamatsu K, Ito S. Pig Cell Melan Res. 2009;22:563–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2009.00610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williamson PR. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:656–664. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.3.656-664.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williamson PR, Wakamatsu K, Ito S. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1570–1572. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.6.1570-1572.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chatterjee S, Prados-Rosales R, Frases S, Itin B, Casadevall A, Stark RE. Biochemistry. 2012;51:6080–6088. doi: 10.1021/bi300325m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tian S, Garcia-Rivera J, Yan B, Casadevall A, Stark RE. Biochemistry. 2003;42:8105–8109. doi: 10.1021/bi0341859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhong J, Frases S, Wang H, Casadevall A, Stark RE. Biochemistry. 2008;47:4701–4710. doi: 10.1021/bi702093r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schnitzer M, Chan YK. Soil Sci Soc Am J. 1986;50:67–71. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duff GA, Roberts JE, Foster N. Biochemistry. 1988;27:7112–7116. doi: 10.1021/bi00418a067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peter MG, Forster H. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1989;28:741–743. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herve M, Hirschinger J, Granger P, Gilard P, Deflandre A, Goetz N. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1204:19–27. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(94)90027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knicker H, Almendros G, Gonzalez-Vila FJ, Luedemann HD, Martin F. Org Geochem. 1995;23:1023–1028. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adhyaru BB, Akhmedov NG, Katritzky AR, Bowers CR. Magn Res Chem. 2003;41:466–474. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thureau P, Ziarelli F, Thévand A, Martin RW, Farmer PJ, Viel S, Mollica G. Chem Eur J. 2012;18:10689–10700. doi: 10.1002/chem.201200277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Della Vecchia NF, Avolio R, Alfè M, Errico ME, Napolitano A, d’Ischia M. Adv Funct Mater. 2013;23:1331–1340. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aime S, Fasano M, Bergamasco B, Lopiano L, Quattrocolo G. Adv Neurol. 1996;69:263–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jastrzebska M, Kocot A, Tajber L. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2002;66:201–206. doi: 10.1016/s1011-1344(02)00268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ghiani S, Baroni S, Burgio D, Digilio G, Fukuhara M, Martino P, Monda K, Nervi C, Kiyomine A, Aime S. Magn Reson Chem. 2008;46:471–479. doi: 10.1002/mrc.2202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garcia-Rivera J, Eisenman HC, Nosanchuk JD, Aisen P, Zaragoza O, Moadel T, Dadachova E, Casadevall A. Fung Gen Biol. 2005;42:989–998. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosas ÁL, Nosanchuk JD, Feldmesser M, Cox GM, Mcdade HC, Casadevall A, Rosas NL, McDade HC, Casadevall A. Infect Immun. 2000;68:2845–2853. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.5.2845-2853.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Y, Aisen P, Casadevall A. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2420–2424. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.7.2420-2424.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Folch J, Lees M, Stanley G. J Biol Chem. 1957;226:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morcombe CR, Zilm KW. J Magn Res. 2003;162:479–486. doi: 10.1016/s1090-7807(03)00082-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harris RK, Becker ED, Menezes SMCDE, Goodfellow R, Granger P. Pure Appl Chem. 2001;73:1795–1818. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Metz G, Wu X, Smith SO. J Magn Reson A. 1994;110:219–227. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bennett AE, Rienstra CM, Auger M, Lakshmi KV, Griffin RG. J Chem Phys. 1995;103:6951–6958. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fung BM, Khitrin AK, Ermolaev K. J Magn Res. 2000;142:97–101. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1999.1896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schaefer J, McKay RA, Stejskal EO. J Magn Res. 1979;34:443–447. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schaefer J, Stejskal EO, Garbow JR, McKay RA. J Magn Res. 1984;59:150–156. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lewandowski JR, De Paëpe G, Griffin RG. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:728–729. doi: 10.1021/ja0650394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.De Paëpe G, Lewandowski JR, Loquet A, Eddy M, Megy S, Böckmann A, Griffin RG. J Chem Phys. 2011;134:095101. doi: 10.1063/1.3541251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Felix CC, Hyde JS, Sarna T, Sealy RC. J Am Chem Soc. 1978;100:3922–3926. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sealy R, Hyde J, Felix C, Menon I, Prota G. Science (80- ) 1982;217:545–547. doi: 10.1126/science.6283638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Petkova AT, Hatanaka M, Jaroniec CP, Hu JG, Belenky M, Verhoeven M, Lugtenburg J, Griffin RG, Herzfeld J. Biochemistry. 2002;41:2429–2437. doi: 10.1021/bi012127m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lewandowski JR, van der Wel PC, Rigney M, Grigorieff N, Griffin RG. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:14686–14698. doi: 10.1021/ja203736z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dreyer DR, Miller DJ, Freeman BD, Paul DR, Bielawski CW. Langmuir. 2012;28:6428–6435. doi: 10.1021/la204831b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.