Arabidopsis seeds with a mutation in urate oxidase show a defect in germination, fail to develop the cotyledons, and exhibit partially blocked β-oxidation. These phenotypes result from the accumulation of uric acid and are suppressed by the additional mutation of xanthine dehydrogenase, which prevents uric acid accumulation. The data presented show that peroxisome maintenance is compromised by uric acid.

Abstract

Purine nucleotides can be fully catabolized by plants to recycle nutrients. We have isolated a urate oxidase (uox) mutant of Arabidopsis thaliana that accumulates uric acid in all tissues, especially in the developing embryo. The mutant displays a reduced germination rate and is unable to establish autotrophic growth due to severe inhibition of cotyledon development and nutrient mobilization from the lipid reserves in the cotyledons. The uox mutant phenotype is suppressed in a xanthine dehydrogenase (xdh) uox double mutant, demonstrating that the underlying cause is not the defective purine base catabolism, or the lack of UOX per se, but the elevated uric acid concentration in the embryo. Remarkably, xanthine accumulates to similar levels in the xdh mutant without toxicity. This is paralleled in humans, where hyperuricemia is associated with many diseases whereas xanthinuria is asymptomatic. Searching for the molecular cause of uric acid toxicity, we discovered a local defect of peroxisomes (glyoxysomes) mostly confined to the cotyledons of the mature embryos, which resulted in the accumulation of free fatty acids in dry seeds. The peroxisomal defect explains the developmental phenotypes of the uox mutant, drawing a novel link between uric acid and peroxisome function, which may be relevant beyond plants.

INTRODUCTION

Nitrogen is a scarce resource for plants, often limiting growth in natural ecosystems. Therefore, plants possess efficient means to remobilize nitrogen, for example from the purine nucleobases. The catabolism of the purine ring of AMP and GMP converges on xanthine as the first common intermediate (Figure 1). Xanthine dehydrogenase (XDH) converts xanthine to uric acid in the cytosol (Hesberg et al., 2004; Werner and Witte, 2011). Uric acid is imported into the peroxisomes and oxidized by urate oxidase (UOX) to hydroxyisourate, which is converted to S-allantoin by two further enzymatic reactions (Lamberto et al., 2010). Humans do not possess a functional UOX; therefore, the final product of human purine ring catabolism is uric acid, which is excreted in the urine. In plants, S-allantoin catabolism in the endoplasmic reticulum results in the complete decomposition of the purine ring system, releasing carbon dioxide, glyoxylate, and all ring nitrogen as ammonia (Serventi et al., 2010; Werner et al., 2010, 2013; Figure 1). Genetic disruption of purine nucleobase catabolism in Arabidopsis thaliana, preventing the release of the ring nitrogen as ammonia, does not lead to obvious phenotypic alterations under standard growth conditions (Yang and Han, 2004; Todd and Polacco, 2006; Brychkova et al., 2008; Werner et al., 2008, 2013).

Figure 1.

Overview of Purine Nucleotide Catabolism.

The scheme focuses on the XDH and UOX reactions. HIU, 5-hydroxyisourate; Pi, phosphate.

Peroxisomes not only harbor part of the purine nucleobase catabolic pathway (Figure 1) but also play a central role in the catabolism of fatty acids (β-oxidation; Theodoulou and Eastmond, 2012). During embryo development of Arabidopsis, triacylglycerols (TAGs) are deposited in lipid bodies to serve as carbon and energy sources for seedling establishment. Without β-oxidation, seedling establishment cannot be completed because the fatty acids released from TAG cannot be metabolized (Graham, 2008). Additionally, functional β-oxidation is required for germination, probably to convert auxin and jasmonate precursors into active signal molecules (Dave et al., 2011; Theodoulou and Eastmond, 2012).

Elevated serum uric acid concentration in humans is linked to the development of several diseases, including gout, coronary heart disease, hypertension, and neurodegenerative disorders. Gout, for example, is caused by crystalline deposits of monosodium urate, which triggers an inflammatory response (Rock et al., 2013). However, soluble uric acid is probably involved in several pathologies as well, although it is still unknown how it exerts its effects at the molecular level (Jin et al., 2012). Mice are able to degrade purine bases beyond uric acid to S-allantoin for excretion, but mutant mice lacking UOX display elevated serum uric acid levels and develop a nephropathy leading to less than 40% survival within 4 weeks after birth (Wu et al., 1994).

Although UOX is well known in plants, plant mutants of UOX have not yet been reported. Here, we show that an elevated uric acid concentration in embryos of Arabidopsis resulting from a mutation in UOX leads to a severe defect in germination and seedling establishment. The molecular cause for this phenotype was investigated. Surprisingly, we found that uric acid (but not its precursor xanthine) interferes with the maintenance of functional peroxisomes during late embryogenesis. This novel link between peroxisome functionality and uric acid accumulation provides a rationale for the observed phenotypes.

RESULTS

Isolation and Characterization of Mutants

The UOX gene from Arabidopsis was identified via homology searches with known UOX from legumes (Nguyen et al., 1985). A homozygous uox mutant with a T-DNA insertion in the first protein-coding exon was isolated from the mutant collection of the Salk Institute (Alonso et al., 2003). A homozygous mutant of xdh (locus At4g34890), containing a T-DNA insertion in the fourth protein-coding exon, was obtained from the Gabi-Kat collection (Kleinboelting et al., 2012). An xdh uox double mutant was generated by crossing the respective single mutants. A uox mutant line, in which the coding sequence of UOX under the control of a 35S promoter was reintroduced (35S:UOX), served to test for genetic complementation. The absence of UOX or XDH in the respective mutants was confirmed by probing for these proteins with specific polyclonal antibodies on immunoblots and by measuring the respective enzymatic activities (Figure 2). UOX protein and activity were completely absent in the uox mutant but were restored to higher levels in the uox complementation line. Similarly, XDH protein and activity were absent in the xdh mutant line, while the xdh uox double mutant lacked XDH as well as UOX. The Arabidopsis genome codes for a second copy of XDH, called XDH2 (locus At4g34900). The activity staining showed that XDH2 did not contribute significantly to the total XDH activity, as had been noted earlier (Yesbergenova et al., 2005). However, the in-gel assay may not be sensitive enough to detect weak XDH2 activity.

Figure 2.

UOX and XDH Amount and Activity in the Wild Type and Mutants.

Leaf samples were from 4-week-old plants of the wild type, uox and xdh mutants, the uox xdh double mutant, and the uox mutant transformed with a 35S promoter–driven UOX cDNA construct for complementation (35S:UOX). Panels from top to bottom are as follows: quantification of UOX activity per milligram of total protein (error bars are sd; n = 3); immunoblot developed with anti-UOX antiserum; visualization of XDH activity in gel; and immunoblot developed with anti-XDH antiserum. mU, milliunits.

Germination and Seedling Establishment of the Mutants

The uox mutant displayed a reduced germination rate from 0 to 20% efficiency, which depended on the respective seed batch. Seeds that did germinate failed to develop a root, showed hypocotyl greening, and had a severe impairment of cotyledon development (Figure 3). These seedlings were unable to develop into adult plants unless grown in the presence of Suc, which allowed the eventual generation of a root and leaves for autotrophic growth. Suc also promoted the greening of the cotyledons from the base to the tip in parallel to the emergence of the first leaves (Supplemental Figure 1). At later growth stages, the uox mutant was independent of Suc and could not be distinguished phenotypically from the wild type. Introduction of a UOX cDNA into the uox mutant background (35S:UOX) complemented the phenotype (Figure 3). In the xdh mutant, the uox phenotype was not observed, and the phenotype was fully suppressed in the xdh uox double mutant. The absence of the UOX protein per se or the defective purine ring catabolism, therefore, is not responsible for the developmental defects of the uox mutant. In accordance, a defect in other enzymes of purine ring catabolism does not cause marked phenotypes under standard growth conditions (Yang and Han, 2004; Todd and Polacco, 2006; Brychkova et al., 2008; Werner et al., 2008, 2013). The severity of the uox mutant phenotype varied in intensity depending on the seed batch and to a lesser extent also within the same seed batch, but it was always clearly visible (Supplemental Figure 2).

Figure 3.

Seedling Establishment of the Wild Type, the uox and xdh Mutants, the uox Complementation Line (35S:UOX), and the Double Mutant.

Seeds were sown on half-strength Murashige and Skoog agar medium, stratified in the dark for 2 d, and grown under long-day conditions (16 h of light). The medium contained 2% (w/v) Suc where indicated. Bars = 1 mm.

UOX Expression Profile

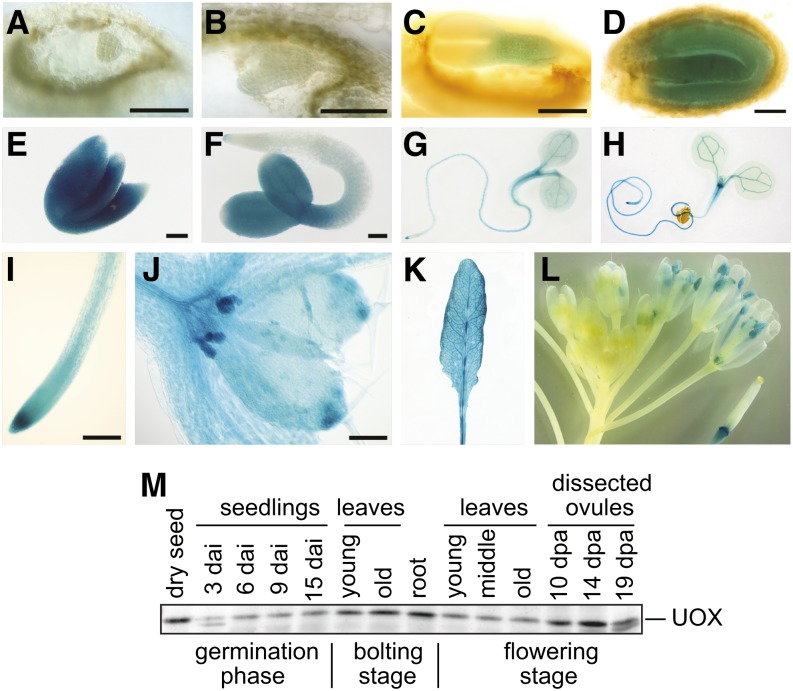

The UOX promoter is activated during embryogenesis (Figure 4). Until the late heart stage of the embryo, no β‑glucuronidase (GUS) staining is observed in lines transformed with a UOX promoter–GUS construct. The UOX promoter activity begins in the hypocotyl at the torpedo stage and expands to the whole embryo at maturity. Three days after imbibition, expression is confined to the root tip and the cotyledons. In young seedlings, the vasculature and meristematic regions are stained. UOX expression is detectable in leaves of a fully developed rosette. UOX is not expressed in young flowers, but later expression initiates in pollen sacs at about the time of pollination and in the abscission zone of the silique. Immunoblot analysis showed that UOX is ubiquitously expressed in shoot and root tissues and highly abundant in developing and mature seeds.

Figure 4.

Promoter Activity and Expression of UOX.

(A) to (E) Promoter-GUS activity during embryonic development.

(A) Globular stage.

(B) Late heart stage.

(C) Torpedo stage.

(D) Bent cotyledon stage.

(E) Mature embryo dissected from the dry seed.

(F) Germinated seedling, 3 DAI.

(G) Young seedling, 5 DAI.

(H) Young seedling, 7 DAI.

(I) Root tip.

(J) Shoot apical tip of seedling, 9 DAI.

(K) Rosette leaf from bolting plant.

(L) Inflorescence.

Bars = 100 μm.

(M) Immunoblot of proteins extracted from different tissues (10 μg of protein per lane), developed with UOX antiserum. dpa, days after anthesis.

Metabolite Analyses

Uric acid was undetectable in leaves, roots, siliques, and seeds of the wild type at any developmental stage, whereas it accumulated in all tissues of the uox mutant. At bolting, uric acid was most abundant in the roots and increased with leaf age (Figure 5A), probably due to elevated nitrogen remobilization activity in older leaves. In siliques, the uric acid content rose strongly with age. At 19 d after anthesis (DAA), separate measurements of developing seeds and silique walls revealed that most uric acid was present in the seeds. Because of their low water content, the seeds contained the highest uric acid concentration of all fresh tissues (Figure 5A, bottom row). At germination, the uric acid content based on dry weight stayed constant, indicating that purine base catabolism was not operative during this developmental phase. However, one needs to bear in mind that cotyledons do not develop in the uox mutant. The UOX promoter is active in cotyledons of young seedlings (Figure 4F), indicating that in the wild type, purine base catabolism is operative in seedlings during germination.

Figure 5.

Uric Acid and Xanthine Metabolite Profiles.

(A) Tissue uric acid content in the uox mutant grown under long-day conditions (16 h of light). Top row, uric acid concentration in reference to the dry weight (dw) of young leaves (yl; leaves 13 to the top leaf), middle-aged leaves (ml; leaves 7 to 12), old leaves (ol; leaves 1 to 6), roots (rt), whole siliques at different DAA (dpa), developing seeds (ds) and silique walls (sw) at 19 DAA, and seedlings during germination at 0 to 15 DAI. Bottom row, as in the top row but with reference to the fresh weight (fw).

(B) Uric acid and xanthine content of seeds of the wild type, the uox and xdh mutants, the xdh uox double mutant, and the complementation line (35S:UOX) grown under long-day conditions (16 h of light).

Mean values ± sd are shown (n = 3 or as indicated).

The uox mutant accumulated around 20 μmol/g uric acid in the seeds (Figure 5B). This accumulation was prevented in the complementation line (35S:UOX) and was completely suppressed in the xdh uox double mutant. Uric acid was undetectable in any tissue of the xdh uox double mutant, providing further evidence that the second XDH gene of Arabidopsis (XDH2; At4g34900) does not contribute at all to xanthine catabolism. Also, seeds of the wild type and the xdh single mutant did not contain uric acid. Instead, the xdh mutant and the xdh uox double mutant accumulated xanthine to ∼20 μmol/g (Figure 5B). Whereas xanthine at this concentration was nontoxic, uric acid at the same concentration caused the observed phenotype (Figure 3). Metabolic profiling of dry seeds employing gas chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (GC-MS) confirmed the presence of uric acid in the uox mutant and its absence in the wild type (Supplemental Figure 3A) and additionally revealed that the uridine and sorbitol concentrations in the uox mutant were strongly elevated (Supplemental Figure 3B). Uridine is catabolized by nucleoside hydrolase1 (Jung et al., 2009). The enzyme might be directly inhibited by uric acid due to a certain structural similarity of uridine and uric acid. However, elevated uridine concentrations do not cause any phenotypes in unstressed plants (Jung et al., 2011; Riegler et al., 2011). Sorbitol accumulates strongly during the desiccation of the Arabidopsis seed (Fait et al., 2006) and probably serves as an osmoprotectant (Locy, 1994). The 10-fold overaccumulation of sorbitol in seeds of the uox mutant indicates that uric acid disturbs the osmotic balance of the seed. Although a few other metabolites were significantly different in concentration between the distinct genotypes, other major (beyond 3-fold) alterations in concentrations were not observed (Supplemental Figure 3).

How Does Uric Acid Disturb Germination and Seedling Establishment?

Uric acid accumulated in seeds of the uox mutant during embryo development to the highest concentration observed in any tissue (Figure 5A, bottom row). It appears that this high dose of uric acid triggers the phenotypes of disturbed germination and seedling establishment, whereas the lower concentrations in other tissues cause no developmental defects. Using several approaches, we sought to elucidate the structural or molecular causes for the observed phenotypes.

Embryo development in the uox mutant compared with the wild type appeared normal when monitored by differential interference contrast microscopy (Supplemental Figure 4). The ultrastructure of embryos dissected from dry seeds of the xdh uox double mutant is similar to that of the wild type (Figures 6A and 6B). Lipid bodies, ranging from 0.5 to 2.0 μm in diameter, represent the largest fraction of cell organelles. Per cell section, three to six large protein bodies (4 to 6 μm) are surrounded by lipid bodies. They are clearly defined by a membrane, a varying electron-dense protein matrix, and electron-dense phytin granules. The uox mutant embryos differ significantly (Figures 6C to 6E). The protein bodies are amorphous and vary in size, number, and position within the cells (Figures 6D and 6E). Often, one large protein body is observed, filled with granular or fibrous substructures of varying electron density (Figure 6C). Frequently, the membrane of the protein bodies cannot be resolved by transmission electron microscopy, indicating that the protein bodies and the cytoplasm may be fused. Protein bodies touching the plasma membrane are often observed, and the densely packed lipid bodies are occasionally fused to a giant lipid reservoir (Figure 6E). The severity of the phenotype varies within the cotyledon tissue and is generally less severe near the vascular bundle and at the periphery toward the hypocotyl. The alteration of protein bodies in the uox mutant led us to investigate whether the deposition of seed storage proteins was affected. A significant reduction of the amount of seed storage proteins of ∼20% was observed in the uox mutant (Supplemental Figure 5). Cytochemical localization of the peroxisomal enzyme catalase revealed a strong decrease of catalase-positive spots in embryo cotyledons of the uox mutant, indicating that the quantity of functional peroxisomes is markedly reduced (Figure 6F; Supplemental Figure 6). Peroxisomal β-oxidation catalyzes the fatty acid breakdown required to mobilize energy and carbon reserves from the lipid stores of the embryo. Without this process, seedling establishment cannot be completed (Graham, 2008). Additionally, β-oxidation is required for germination, probably to metabolize auxin and jasmonate precursors serving as signals in this process (Dave et al., 2011; Theodoulou and Eastmond, 2012). The strong reduction of the peroxisome number in the uox mutant, therefore, explains the perturbation of both developmental processes and the rescue of germinated mutant seedlings by external Suc, serving as carbon and energy sources. Consistent with this, storage lipids are retained in the cotyledons of the uox mutant during seedling establishment (Supplemental Figure 7). To monitor the distribution and developmental onset of the peroxisomal defect in vivo, fluorescently labeled peroxisomes were imaged throughout embryonic development and germination. For this purpose, both the wild type and the uox mutant were transformed with a construct expressing a green fluorescent protein (GFP) variant fused to a peroxisomal targeting signal type 1, roGFP2-SKL (Rosenwasser et al., 2011). The expression of the GFP transgene was monitored by immunoblot analysis (Figure 7A), and it was confirmed that the uox mutant phenotype was maintained in the respective transgenic lines (Figure 7B).

Figure 6.

Ultrastructural Alterations in Mature Embryos of the uox Mutant.

(A) to (E) Transmission electron micrographs of cotyledon parenchyma cells of the wild type (A), the xdh uox double mutant (B), and the uox mutant ([C] to [E]). lb, lipid body; p, protein body. Arrows indicate abnormalities in the uox mutant. Bars = 2 μm.

(F) Quantification of peroxisome numbers by counting DAB-positive spots in cotyledons of the wild type, the uox mutant, and the xdh uox double mutant in light micrographs from semithin sections (Supplemental Figure 6). The horizontal bar is the mean (n = 8, 5, and 6 for the wild type, uox, and xdh uox, respectively). Statistical significance was determined using ANOVA coupled to Dunnett’s posttest. Generally, P values below 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001 are represented by one, two, and three asterisks, respectively, and the numeric values are shown, unless the P value is smaller than 0.001 (indicated by <0.001).

Figure 7.

Comparison of Transgenic Plant Lines Expressing Peroxisomal GFP in the Wild Type and the uox Mutant Background.

(A) Expression of roGFP2-SKL in seeds of three different transformed uox mutant lines and two different transformed wild-type lines monitored by immunoblot probed with anti-GFP antibodies.

(B) Confirmation of the uox phenotype on medium without Suc in the lines transformed with GFP at 7 DAI.

(C) Fluorescence microscopy of embryos with wild-type or uox mutant background from the lines analyzed in (A) and (B). Embryos were excised at different DAA (dpa), from the dry seed, and 6 d after imbibition in the dark. Representative micrographs of the cotyledons (c) and the hypocotyls (h) are shown. Bars = 25 µm.

(D) Quantification of peroxisome numbers in cotyledons and hypocotyls of embryos dissected from dry seed. Each dot resulted from peroxisome quantification in an independent seedling using a stack of images. The horizontal bar is the mean (n = 4 to 10). Statistical significance was determined using ANOVA coupled to Dunnett’s posttest. P values are indicated as described in Figure 6.

Before 21 DAA, no difference between embryos of the wild type and the uox lines was observed. Both showed a dotted pattern of green fluorescence in cotyledons and hypocotyls, indicating efficient GFP import into peroxisomes (Figure 7C, 15 dpa). This pattern was maintained in the wild type throughout embryo development and germination. By contrast, the uox lines are characterized by a loss of punctiform signal beginning at 21 DAA predominantly in the central parts of the cotyledons (Figure 7C). Peroxisomal mosaicism was observed where adjacent cells either displayed a punctiform GFP signal or a diffuse signal indicating cytosolic localization (Figure 7C, 47 dpa). Such mosaicism was also reported from human fibroblasts of patients suffering from milder forms of peroxisomal biogenesis disorders (Gootjes et al., 2004). Mislocalized roGFP2-SKL becomes more prominent in older embryos dissected from dry or imbibed seeds. Here, the peroxisomal defect can extend from the cotyledons into the hypocotyls to varying extents but generally does not affect the base of the hypocotyl and the radicle. The peroxisome number is significantly reduced in embryos of the uox roGFP2-SKL lines, quantified by the analysis of several micrographs from independent dry seeds for each line (Figure 7D). In the wild type, after the imbibition of the seeds for 6 d in the dark, individual peroxisomes grew in size and multiplied, clustering around residual lipid bodies in cotyledon as well as in hypocotyl cells (Figure 7). By contrast, cotyledons of uox lines resembled those of the dry seed, with peroxisomal mosaicism or completely lacking peroxisomal signals but showing diffuse fluorescence instead. The absence of peroxisomes causes a defect of peroxisomal β-oxidation, which can be assessed by probing for the insensitivity of seedling growth to 2,4-dichlorophenoxybutyric acid (2,4-DB). 2,4-DB is converted by β-oxidation to 2,4-D, a toxic auxin analog. Interestingly, the uox mutant was fully susceptible to 2,4-DB (Supplemental Figure 8), because peroxisomes remain functional in the radicle and the roots (Figure 7), which are in direct contact with 2,4-DB. However, an analysis of the lipid composition in dry seeds revealed that the concentration of total free fatty acids was significantly increased in the uox mutant (Figure 8A), which was mainly due to a higher content of unsaturated fatty acids (Supplemental Figure 9). The content of free fatty acids, especially those that are incorporated into TAG (like 20:1), rose sharply in the uox mutant within 6 d after imbibition (DAI) (Figure 8B), whereas the degradation of TAG was markedly reduced in the mutant (residual TAG was 74% ± 7% in the uox mutant versus 3% ± 3% in the wild type). Together, these data demonstrate that β-oxidation is partially defective in the uox mutant.

Figure 8.

Lipid Analysis of Dry Seeds and Changes of Fatty Acid Content after Imbibition.

(A) Relative quantification of free fatty acids (FA), TAGs, glycerophospholipids (GPL), and galactolipids (GL) in dry seeds of the uox mutant (n = 5), the wild type (n = 5), and the xdh uox double mutant (n = 4). Error bars are sd. Statistical significance was determined using ANOVA coupled to Dunnett’s posttest. P values are indicated as described in Figure 6.

(B) Ratio of fatty acid content in seedlings at 6 DAI (including the seed coat) versus dry seeds in the uox mutant, the wild type, and the 35S complementation line for total fatty acids and the TAG-specific 20:1 fatty acid. The total TAG content in these lines was 74% ± 7%, 3% ± 3%, and 24% ± 6% (ratio of seed to seedling), respectively. sd is shown (n = 5), and statistical evaluation was as in (A).

Peroxisomal Defects in Other Tissues and Defects Triggered by Uric Acid Application

In leaves or roots of uox mutant seedlings grown on Suc medium, no peroxisomal defects were observed (Supplemental Figure 10). Quantifying and comparing peroxisome numbers in uox mutant and wild-type leaves of 6-week-old plants indicated that the uox mutant might have a lower number of peroxisomes in leaves than the wild type (Supplemental Figure 11). However, the different expression levels of the roGFP2-SKL transgene in the uox mutant and wild-type lines (Figure 7A) required distinct microscope settings to generate similarly exposed images (see Methods). Therefore, this result has to be treated with caution, because changes in microscope settings can influence the data significantly (Supplemental Figure 11C). Lines with identical roGFP-SKL expression would be required to obtain more robust quantitative data in cases where peroxisomal defects are subtle and not as obvious as in the embryo.

In an attempt to trigger and mimic a peroxisomal defect by the application of external uric acid, wild-type seeds (of a line transformed with roGFP2-SKL) were incubated with uric acid for 4 d at 4°C. The peroxisome number appeared to be negatively influenced, but the effect was not statistically significant (Supplemental Figure 12A). When uox mutant leaves of different ages were infiltrated with a saturated solution of uric acid and incubated for 3 d, the peroxisome number also was not significantly changed by the treatment (Supplemental Figure 12B).

DISCUSSION

In the oil seeds of the Brassicaceae, energy and carbon reserves for seedling establishment are deposited during embryo development in the cotyledons as TAG in lipid bodies. During seedling establishment, these resources are mobilized by lipid hydrolysis and fatty acid catabolism (β-oxidation), which are connected to sugar biosynthesis by the glyoxylate cycle (Theodoulou and Eastmond, 2012). The β-oxidation is located in the peroxisomes, which sometimes are referred to as glyoxysomes when they additionally contain glyoxylate cycle enzymes and lack photorespiratory enzymes (Graham, 2008). Several mutants in lipid degradation, for example those in the gene of the ABC transporter COMATOSE (CTS, PXA1, or PED3) involved in fatty acid import into the peroxisomes (Zolman et al., 2001; Footitt et al., 2002; Hayashi et al., 2002), but also others (Goepfert and Poirier, 2007), show phenotypes similar to the uox mutant: germination is perturbed and they are unable to mobilize the storage lipids, but they grow normally once an autotrophic seedling has been established by the support of externally supplied Suc. However, in contrast with some mutants in β-oxidation, for example cts/pxa1 (Kunz et al., 2009), the adult uox plant is not hypersusceptible to extended darkness (Supplemental Figure 13). This difference is explained by the temporal and local restriction of the peroxisomal defect to the mature uox embryo, while other tissues of the uox mutant contain peroxisomes (Supplemental Figures 10 and 11) and consequently possess operative β-oxidation. The local restriction of the peroxisomal defect also provides a rationale for the 2,4-DB sensitivity of the uox seedlings, because the radicles of uox embryos usually contain peroxisomes (Figure 7), as do the emerging roots (Supplemental Figure 10), which therefore respond to 2,4-DB in the same manner as roots of the wild type.

In the presence of Suc, mutants with defective storage lipid mobilization, defective lipid oxidation, or partially impaired peroxisomal protein import develop green cotyledons with fairly normal appearance (Footitt et al., 2002; Khan and Zolman, 2010), whereas cotyledon development in the uox mutant is severely retarded even in the presence of Suc (Supplemental Figure 1). The constitutive absence of functional peroxisomes is lethal, as indicated by the gametophytic or embryo-lethal phenotype of many peroxisomal biogenesis factor (peroxin) mutants (Hu et al., 2012). The uox cotyledon phenotype likely represents the outcome of a local absence of functional peroxisomes, but it additionally might be a consequence of the other subcellular perturbations observed in this tissue (Figures 6C to 6E).

Young embryos carry out photosynthesis (Fait et al., 2006) and possess peroxisomes, but in late embryos in the desiccation phase, operative glyoxysomes are formed likely by importing glyoxylate cycle enzymes into peroxisomes (Comai et al., 1989). During desiccation, up to 10% of the deposited lipids are already degraded to provide energy (Chia et al., 2005), but also succinate and fumarate accumulate, which presumably are generated via the glyoxylate cycle (Fait et al., 2006; Angelovici et al., 2010). The absence of catalase (diaminobenzidine [DAB] staining) (Figure 6F) and the mislocalization of peroxisomal GFP to the cytosol (Figure 7) at high uric acid concentrations in the uox mutant might result from changes to peroxisomal protein import or degradation (Huybrechts et al., 2009; Lingard et al., 2009) or might be caused by alterations of whole organelle turnover (Farmer et al., 2013; Nordgren et al., 2013). However, fumarate and succinate concentrations in the uox mutant are similar to those in the wild type (Supplemental Figure 3), indicating that the peroxisome-to-glyoxysome transition is still operative in the mutant. Nonetheless, the functionality of the glyoxysomes appears to be partially compromised, because free fatty acids accumulate in the uox embryo (Figure 8; Supplemental Figure 9), which is also observed in embryos of the cts/pxa1 mutant (Footitt et al., 2002) unable to import fatty acids into the peroxisomes. Our confocal images are consistent with a loss of peroxisomal functionality at rather late stages of embryo desiccation (Figure 7C). In summary, embryo development in the uox mutant is fairly normal, even the peroxisome-to-glyoxysome transition seems not disturbed, but glyoxysome maintenance breaks down once the uric acid concentration reaches a critical level in the desiccation phase. Even lower doses of uric acid might have subtle effects on the peroxisome number in leaves (Supplemental Figure 11), but with our experimental tools this cannot be shown conclusively. When uric acid was infiltrated into uox mutant leaves, the peroxisome number was not influenced. It is possible that uric acid is not taken up in sufficient amounts or that the exposure time to uric acid needs to be longer.

In nodules of Vigna aconitifolia (mothbean), the peroxisomes were smaller when UOX was quantitatively reduced by RNA interference, indicating that UOX might have a structural function (Lee et al., 1993). In the uox mutant of Arabidopsis, peroxisomes appear normal in size, demonstrating that in this plant UOX is not structurally important for peroxisomal development. However, tropical legumes require large quantities of UOX in the nodules to convert fixed nitrogen into the ureide nitrogen transport compounds (Schubert, 1986). Therefore, it is conceivable that UOX has a more important role in this case.

Interestingly, excess uric acid is not only toxic to plants (Wu et al., 1994). In humans, uric acid is recognized as a damage-associated molecular pattern. Upon cell damage, uric acid leaks into the sodium-rich surroundings and monosodium urate crystals form, triggering an immune response directing the immune system to the site of cell injury (Shi et al., 2003). Hyperuricaemia leads to the constitutive formation of monosodium urate crystals, triggering a constant inflammatory response that causes the arthritis symptoms observed in individuals suffering from gout (Rock et al., 2013). Hyperuricaemia has been associated with additional diseases, including renal disease, hypertension, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, lipid disorders, respiratory symptoms, and the Lesch-Nyhan syndrome. The molecular mechanisms by which uric acid contributes to the development of these conditions are poorly understood (Jin et al., 2012; Rock et al., 2013). Reduced peroxisomal functionality might be involved. However, hereditary peroxisomal defects in humans with notable effects on peroxisome function lead to more severe phenotypes than observed with hyperuricaemia (Steinberg et al., 2006). Nonetheless, our data for leaves (Supplemental Figure 11) indicate that subtle effects on peroxisomes mediated by uric acid might occur. This needs to be further investigated in plants and animals. Although xanthine in the xdh mutant reached the same concentration as uric acid in the uox mutant, there was no apparent phenotypic consequence, showing that the mere accumulation of oxopurines in plant cells is not toxic. This is paralleled in humans, where a defect in XDH results in high serum xanthine levels and excretion of xanthine in the urine (xanthinuria) but does not lead to any other complication than the formation of xanthine stones (Ichida et al., 2012; http://www.orpha.net). The particular toxicity of uric acid remains mysterious. We have shown that in plants peroxisome dysfunction can be linked to uric acid toxicity. Because many peroxisome biogenesis factors (Hu et al., 2012) and processes of peroxisome quality control and maintenance (Farmer et al., 2013) are conserved in eukaryotes, it seems possible that uric acid accumulation may also affect peroxisome functionality in nonplant organisms.

METHODS

Plant Material and Cultivation

Arabidopsis thaliana Columbia-0 (Col-0) was used as the wild type. Homozygous mutants in UOX (SALK131438) were screened by PCR using primers 1886 + N61 and 1886 + 1233 (Supplemental Table 1) and in XDH1 (GK049D04) using primers 1968 + 1969 and 1968 + 448.

For the generation of a UOX promoter–GUS construct, a 1554-bp promoter fragment was amplified by PCR with primers 1825 and 1826 from genomic DNA to replace the 35S promoter of pI1 (Matschi et al., 2013) excised with AscI and EcoRI. A GUS cDNA amplified with primers 403 and 438 from the phs23 vector (Scholthof, 1999) was inserted via EcoRI and SmaI, generating pI2-pUOX-GUS (construct P83), which was transformed into Col-0 plants. Complementation lines were generated by transforming pXS2-UOX (P93) for the expression of UOX under the transcriptional control of a 35S promoter into the uox mutant. The construct was obtained by cloning UOX cDNA (from leaf RNA using primers 1823 and 1824) into pXS2pat (Cao et al., 2010) via NcoI and XmaI restriction sites. Transgenic lines expressing roGFP2-SKL were generated by transformation of the respective genotypes with per-GRX1-roGFP2 (Rosenwasser et al., 2011).

Seeds were surface-sterilized and sown on plates containing half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium sealed with Parafilm. For growth on soil, the uox mutant was first germinated on plates supplemented with 2% (w/v) Suc and, after seedling establishment (∼10 d), transferred to soil. Plants were cultivated in a growth chamber at 20°C and 60% relative humidity in a 16-h-light/8-h-dark regime at 100 μmol photons m−2 s−1.

Antibodies, Protein Extraction, Immunoblot, and Activity Assays

A UOX cDNA amplified with primers 1823 and 1824 and a partial XDH cDNA (coding for the FAD domain) amplified with primers 2604 and 2626 were cloned into pET30a (constructs P106 and P126, respectively). Both constructs were expressed in Escherichia coli and served to prepare the antisera as described by Dahncke and Witte (2013).

Fresh leaf material (1 g) was macerated in a mortar on ice with 2.5 mL of extraction buffer [0.1 M HEPES, pH 7.7, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 5 mM DTT, and 0.1 mM 4-(2-aminoethyl)-benzensulfonylfluoride]. Protein concentrations in supernatants (20,000g, 15 min, 4°C) were determined using a Bradford assay. For immunoblots developed with anti-UOX antiserum, 50 μg of protein per lane was loaded. For immunoblots developed with anti-XDH antiserum, 500 μL of supernatant was mixed with an equal volume of 40% (v/v) polyethylene glycol 4000, precipitated for 15 min on ice, and centrifuged (20,000g, 15 min, 4°C), and the pellet was resuspended in 100 μL of SDS-PAGE loading buffer (1×). Then, 20 μL was loaded per lane.

For the in-gel detection of XDH activity, polyethylene glycol pellets were resuspended in 100 μL of native PAGE loading buffer (1×) and 20 μL was loaded per lane on 8% (w/v) acrylamide native gels run at 4°C. Staining was performed overnight in 250 mM Tris buffer, pH 8.5, containing 0.05% (w/v) hypoxanthine, 0.005% (w/v) 5-methylphenaziniummethylsulfate, and 0.005% (w/v) 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazoliumbromide.

For the UOX activity assay, proteins from three independent biological replicates for each genotype were transferred by gel filtration (5-mL HiTrap Desalting columns; GE Healthcare) into 10 mM Taurin buffer, pH 9.0, containing 0.25 mM EDTA, 0.01% (v/v) Triton X-100, and 1 mM DTT and quantified. Then, 50 μL of xanthine agarose slurry (Sigma-Aldrich X3128) was added and incubated for 20 min on a rotating wheel at 4°C to bind UOX. The resin was pelleted (1 min at 700g), the supernatant was discarded, and bound UOX was eluted for 3 min at 30°C with 30 mM Taurin buffer containing 250 μM uric acid. The enzymatic activity was quantified photometrically at 292 nm and 30°C.

Analysis of Seed Proteins

Ten milligrams of seeds was frozen in liquid nitrogen in a 2-mL tube containing a single one-quarter-inch ceramic sphere (MP Biomedicals) and ground to a fine powder using a Retsch MM400 mill for 1 min at 30 Hz. The powder was resuspended in 200 μL of hot buffer containing 2% SDS, 100 mM Tris, pH 6.8, and 100 mM DTT, vortexed, and incubated for 10 min at 95°C. After centrifugation at 10,000g for 1 min, the supernatant was saved and the pellet was extracted two more times with 200 μL of buffer for 1 min. To 400 μL of pooled supernatants, 100 μL of 5-fold concentrated SDS loading buffer was added, and 2 μL was loaded per lane on a 15% SDS-PAGE device prepared with an acrylamide:N,N′-methylenebisacrylamide solution of 29:1.

Uric Acid and Xanthine Quantification

Xanthine and uric acid were extracted by grinding frozen tissues: 10 mg of dry seeds or seedlings in 100 μL or 100 mg of leaves in 500 μL of 0.1 M Tris, pH 7.5, in a 1.5-mL microfuge vial using a rotating pestle for 1 min. Samples were heated (95°C, 10 min) and centrifuged (20,000g, 15 min, room temperature), pellets were reextracted once, and supernatants were pooled. Using UOX (Sigma-Aldrich U0880), uric acid was fully oxidized to hydroxyisourate and H2O2, which served to convert Amplex Ultra Red (Invitrogen) to Resorufin with horseradish peroxidase. The coupled reaction was monitored and Resorufin was quantified at 560 nm. Similarly, xanthine was quantified using xanthine oxidase (XO; Serva 38418). Controls without UOX or XO were performed for each sample. Uric acid and xanthine standards were prepared in wild-type extracts (not containing either substance) to account for interference from the plant extract background. A standard assay setup of 100 μL contained 50 μL of sample, 20 milliunits of UOX (or 2 milliunits of XO), 20 milliunits of horseradish peroxidase, and 50 μM Amplex Ultra Red.

Metabolite Analysis by GC-MS

For metabolite profiling by GC-MS using the DSQII system (Thermo Fisher Scientific), dry seed samples (20 mg; five replicates) were frozen in liquid nitrogen and soluble metabolites were extracted. Seed-producing plants of the analyzed genotypes had been grown next to each other under identical conditions. The extraction method, derivatization, GC-MS measurements, and metabolite identification and quantification were performed as described previously (Fait et al., 2006; Luedemann et al., 2008).

Lipid Analysis

The lipophilic compounds from 10 mg of seeds were extracted using methyl tertiary butyl ether:methanol extraction (Giavalisco et al., 2011). Then, 400 μL of the organic phase of the extraction was removed and dried in a vacuum centrifuge. The dried pellets were resuspended in 400 μL of acetonitrile:isopropanol (7:3). For the comparison of fatty acid content in dry seeds and seedlings after 6 DAI, 30 seeds or seedlings with seed coat were taken per sample and treated as outlined above.

Lipid analysis was performed using ultraperformance liquid chromatography coupled to high-resolution mass spectrometry according to Giavalisco et al. (2011) and Hummel et al. (2011). For the measurements, 3 μL of the resuspended lipid pellets were injected on reverse-phase ultraperformance liquid chromatography columns (Waters Aquity BEHC8) and the lipids were measured in positive and negative ionization mode. Raw chromatograms were further processed using the CoMet2 software package (NonLinear Dynamics). The detected peaks were finally assigned to lipid identities using the curated TargetLipid database (Hummel et al., 2011).

Seed and Leaf Incubation with Saturated Uric Acid Solutions

Uric acid for a 15 mM solution was added to 2.5 mM MOPS and the pH adjusted to 7.0. Uric acid is not fully soluble at this concentration and remains partially precipitated. MOPS buffer without uric acid served as a control. Wild-type seeds expressing roGFP2-SKL were imbibed with either solution for 4 d at 4°C and then inspected for alterations of the peroxisome number using the confocal microscope.

Equally, rosettes of 6-week-old uox mutant plants expressing roGFP2-SKL were vacuum-infiltrated with the solutions containing 0.005% Silwet and kept for 72 h under long-day conditions (16 h of light) on filter paper soaked with the solutions before microscopic inspection.

Microscopy and Stainings

GUS staining was performed as described by Matschi et al. (2013). Staining with Nile red was performed as described by Greenspan et al. (1985) and recorded using a Zeiss Axioplan epifluorescence microscope with filter set 38 HE. For differential interference contrast microscopy, siliques were opened, mounted in Hoyer’s solution (20 mL of glycerol, 200 g of chloral hydrate, and 30 g of gum arabic per 50 mL of water) on glass slides with cover slips, and left to dry for 2 d. Then, the specimens were sealed with nail polish and examined with a Zeiss Axioskop 2 microscope equipped with Nomarski prisms.

Light microscopy (Axiophot; Zeiss) of semithin cuts, catalase staining, and transmission electron microscopy (Zeiss EM 912 with integrated Omega filter operated in the zero loss mode) were performed as described by Wanner et al. (1982). Embryos were dissected from dry seeds after imbibition for 1 h. Catalase-positive spots were counted in digitalized light micrographs of semithin sections using ImageJ (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/).

Confocal images were acquired with a Leica TCS-SP5 confocal laser scanning microscope equipped with an HCX PL APO 63× 1.20 UV water-immersion objective using the Leica Application Suite Advanced Fluorescence Software and a pinhole setting of 1 Airy. Samples of embryos were mounted in 0.1 M Tris buffer, pH 7.5, and leaf discs were mounted in water. Peroxisomal roGFP2-SKL was detected using an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and recording the emission of fluorescence from 500 to 600 nm. To account for differences in the expression level of roGFP2 between wild-type and uox mutant lines, the photomultiplier voltage (smart gain) was adjusted to use the full dynamic range of gray values. Each individual sample was recorded as a z-stack consisting of eight sections covering the whole specimen from top to bottom. Only the false-colored, high-magnification images in Figure 7 were generated from a single section.

For quantification of the peroxisomes, the GFP channel recordings of each z-stack were imported as TIF files into ImageJ and overlaid to a Z-Project (Image → Stacks → Images to Stack and Image → Stacks → Z-Project → Projection Type: Max Intensity). Each overlay image of a given sample was then processed to cut off background signal (Image → Adjust → Auto Threshold → Minimum). Peroxisomes (i.e., signal spots) were defined with the function Analyze → Analyze Particles: Size 0,5–Infinity, Circularity 0–1, Show Outlines and counted, yielding spots per area.

To assess the influence of the photomultiplier voltage on the spots per area count in leaves, several leaf samples were registered at 600, 650, 700, 750, and 800 V for uox line 1 and uox line 3 and at 750, 800, 850, 900, and 950 V for the wild type, and the slope was used to calculate the data in Supplemental Figure 11C.

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL databases under the following accession numbers: At2g26230, UOX; At4g34890, XDH; At4g34900, XDH2; and At4g39850, CTS/PXA1.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure 1. Development of the uox Mutant in Comparison with the Wild Type in the Presence of Sucrose.

Supplemental Figure 2. Variation of the uox Mutant Phenotype Depending on the Seed Batch and the Individual.

Supplemental Figure 3. Metabolite Analysis of Dry Seeds of the Wild Type, the uox Mutant, and the xdh uox Double Mutant by GC-MS.

Supplemental Figure 4. Embryonic Development of the uox Mutant Compared with the Wild Type Monitored by Differential Interference Contrast Microscopy.

Supplemental Figure 5. Seed Proteins Extracted from Wild-Type, uox Mutant, and xdh uox Double Mutant Seeds.

Supplemental Figure 6. Representative DAB-Stained Micrographs from Cotyledons for the Quantification of Peroxisome Numbers.

Supplemental Figure 7. Lipid Staining of Seedlings from the Wild Type and the uox Mutant.

Supplemental Figure 8. Assessment of 2,4-Dichlorophenoxybutyric Acid Sensitivity.

Supplemental Figure 9. Lipid Analysis of Dry Seeds by UPLC-MS.

Supplemental Figure 10. Quantification of Peroxisomes in the First True Leaves, and Qualitative Inspection of Peroxisomes in the Seedling Root.

Supplemental Figure 11. Quantification of Peroxisomes in Leaves of the uox Mutant and the Wild Type.

Supplemental Figure 12. Influence of External Uric Acid on Peroxisome Number in Seeds and Leaves.

Supplemental Figure 13. Impact of Dark Stress on the uox Mutant, the Wild Type, and the pxa1 Mutant.

Supplemental Table 1. Primers Used in This Study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Florian Bittner for supplying the xdh mutant, Frederica L. Theodoulou for the pxa1-1 mutant, and Andreas Meyer for the vector per-GRX1-roGFP2 and for seeds of Col-0 transformed with this vector. We also thank Britta Ehlert for assistance with GC-MS analyses and Silvia Dobler and Jennifer Grünert of the Wanner laboratory for their excellent technical assistance. This research was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Grant DFG WI3411/1-2) and the German Academic Exchange Service from funds of the German Federal Ministry for Education and Research, program German-Chinese Research Groups.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

O.K.H., J.S., and N.M.E. performed most of the research. G.W. performed the electron microscopy. P.G. carried out the lipid analysis. C.-P.W. designed the research and wrote the article with the contribution of O.K.H.

Glossary

- TAG

triacylglycerol

- DAA

days after anthesis

- GC-MS

gas chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry

- 2,4-DB

2,4-dichlorophenoxybutyric acid

- DAI

days after imbibition

- DAB

diaminobenzidine

- Col-0

Columbia-0

Footnotes

Online version contains Web-only data.

References

- Alonso J.M., et al. (2003). Genome-wide insertional mutagenesis of Arabidopsis thaliana. Science 301: 653–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelovici R., Galili G., Fernie A.R., Fait A. (2010). Seed desiccation: A bridge between maturation and germination. Trends Plant Sci. 15: 211–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brychkova G., Alikulov Z., Fluhr R., Sagi M. (2008). A critical role for ureides in dark and senescence-induced purine remobilization is unmasked in the Atxdh1 Arabidopsis mutant. Plant J. 54: 496–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao F.Q., Werner A.K., Dahncke K., Romeis T., Liu L.H., Witte C.P. (2010). Identification and characterization of proteins involved in rice urea and arginine catabolism. Plant Physiol. 154: 98–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chia T.Y.P., Pike M.J., Rawsthorne S. (2005). Storage oil breakdown during embryo development of Brassica napus (L.). J. Exp. Bot. 56: 1285–1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comai L., Dietrich R.A., Maslyar D.J., Baden C.S., Harada J.J. (1989). Coordinate expression of transcriptionally regulated isocitrate lyase and malate synthase genes in Brassica napus L. Plant Cell 1: 293–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahncke K., Witte C.P. (2013). Plant purine nucleoside catabolism employs a guanosine deaminase required for the generation of xanthosine in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25: 4101–4109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dave A., Hernández M.L., He Z., Andriotis V.M.E., Vaistij F.E., Larson T.R., Graham I.A. (2011). 12-Oxo-phytodienoic acid accumulation during seed development represses seed germination in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 23: 583–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fait A., Angelovici R., Less H., Ohad I., Urbanczyk-Wochniak E., Fernie A.R., Galili G. (2006). Arabidopsis seed development and germination is associated with temporally distinct metabolic switches. Plant Physiol. 142: 839–854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer L.M., Rinaldi M.A., Young P.G., Danan C.H., Burkhart S.E., Bartel B. (2013). Disrupting autophagy restores peroxisome function to an Arabidopsis lon2 mutant and reveals a role for the LON2 protease in peroxisomal matrix protein degradation. Plant Cell 25: 4085–4100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Footitt S., Slocombe S.P., Larner V., Kurup S., Wu Y., Larson T., Graham I., Baker A., Holdsworth M. (2002). Control of germination and lipid mobilization by COMATOSE, the Arabidopsis homologue of human ALDP. EMBO J. 21: 2912–2922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giavalisco P., Li Y., Matthes A., Eckhardt A., Hubberten H.M., Hesse H., Segu S., Hummel J., Köhl K., Willmitzer L. (2011). Elemental formula annotation of polar and lipophilic metabolites using 13C, 15N and 34S isotope labelling, in combination with high-resolution mass spectrometry. Plant J. 68: 364–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goepfert S., Poirier Y. (2007). Beta-oxidation in fatty acid degradation and beyond. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 10: 245–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gootjes J., Schmohl F., Mooijer P.A.W., Dekker C., Mandel H., Topcu M., Huemer M., Von Schütz M., Marquardt T., Smeitink J.A., Waterham H.R., Wanders R.J.A. (2004). Identification of the molecular defect in patients with peroxisomal mosaicism using a novel method involving culturing of cells at 40 degrees C: Implications for other inborn errors of metabolism. Hum. Mutat. 24: 130–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham I.A. (2008). Seed storage oil mobilization. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 59: 115–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenspan P., Mayer E.P., Fowler S.D. (1985). Nile red: A selective fluorescent stain for intracellular lipid droplets. J. Cell Biol. 100: 965–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi M., Nito K., Takei-Hoshi R., Yagi M., Kondo M., Suenaga A., Yamaya T., Nishimura M. (2002). Ped3p is a peroxisomal ATP-binding cassette transporter that might supply substrates for fatty acid beta-oxidation. Plant Cell Physiol. 43: 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesberg C., Hänsch R., Mendel R.R., Bittner F. (2004). Tandem orientation of duplicated xanthine dehydrogenase genes from Arabidopsis thaliana: Differential gene expression and enzyme activities. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 13547–13554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J., Baker A., Bartel B., Linka N., Mullen R.T., Reumann S., Zolman B.K. (2012). Plant peroxisomes: Biogenesis and function. Plant Cell 24: 2279–2303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummel J., Segu S., Li Y., Irgang S., Jueppner J., Giavalisco P. (2011). Ultra performance liquid chromatography and high resolution mass spectrometry for the analysis of plant lipids. Front. Plant Sci. 2: 54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huybrechts S.J., Van Veldhoven P.P., Brees C., Mannaerts G.P., Los G.V., Fransen M. (2009). Peroxisome dynamics in cultured mammalian cells. Traffic 10: 1722–1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichida K., Amaya Y., Okamoto K., Nishino T. (2012). Mutations associated with functional disorder of xanthine oxidoreductase and hereditary xanthinuria in humans. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 13: 15475–15495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin M., Yang F., Yang I., Yin Y., Luo J.J., Wang H., Yang X.F. (2012). Uric acid, hyperuricemia and vascular diseases. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed.) 17: 656–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung B., Flörchinger M., Kunz H.H., Traub M., Wartenberg R., Jeblick W., Neuhaus H.E., Möhlmann T. (2009). Uridine-ribohydrolase is a key regulator in the uridine degradation pathway of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 21: 876–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung B., Hoffmann C., Möhlmann T. (2011). Arabidopsis nucleoside hydrolases involved in intracellular and extracellular degradation of purines. Plant J. 65: 703–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan B.R., Zolman B.K. (2010). pex5 mutants that differentially disrupt PTS1 and PTS2 peroxisomal matrix protein import in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 154: 1602–1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinboelting N., Huep G., Kloetgen A., Viehoever P., Weisshaar B. (2012). GABI-Kat SimpleSearch: New features of the Arabidopsis thaliana T-DNA mutant database. Nucleic Acids Res. 40: D1211–D1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunz H.H., Scharnewski M., Feussner K., Feussner I., Flügge U.I., Fulda M., Gierth M. (2009). The ABC transporter PXA1 and peroxisomal β-oxidation are vital for metabolism in mature leaves of Arabidopsis during extended darkness. Plant Cell 21: 2733–2749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamberto I., Percudani R., Gatti R., Folli C., Petrucco S. (2010). Conserved alternative splicing of Arabidopsis transthyretin-like determines protein localization and S-allantoin synthesis in peroxisomes. Plant Cell 22: 1564–1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee N.G., Stein B., Suzuki H., Verma D.P.S. (1993). Expression of antisense nodulin-35 RNA in Vigna aconitifolia transgenic root nodules retards peroxisome development and affects nitrogen availability to the plant. Plant J. 3: 599–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingard M.J., Monroe-Augustus M., Bartel B. (2009). Peroxisome-associated matrix protein degradation in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106: 4561–4566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locy, R.D. (1994). A role for sorbitol in desiccation tolerance of developing maize kernels: Inference from the properties of maize sorbitol dehydrogenase. In Biochemical and Cellular Mechanisms of Stress Tolerance in Plants, J.H. Cherry, ed (Berlin: Springer), pp. 345–368. [Google Scholar]

- Luedemann A., Strassburg K., Erban A., Kopka J. (2008). TagFinder for the quantitative analysis of gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS)-based metabolite profiling experiments. Bioinformatics 24: 732–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matschi S., Werner S., Schulze W.X., Legen J., Hilger H.H., Romeis T. (2013). Function of calcium-dependent protein kinase CPK28 of Arabidopsis thaliana in plant stem elongation and vascular development. Plant J. 73: 883–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T., Zelechowska M., Foster V., Bergmann H., Verma D.P. (1985). Primary structure of the soybean nodulin-35 gene encoding uricase II localized in the peroxisomes of uninfected cells of nodules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82: 5040–5044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordgren M., Wang B., Apanasets O., Fransen M. (2013). Peroxisome degradation in mammals: Mechanisms of action, recent advances, and perspectives. Front. Physiol. 4: 145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riegler H., Geserick C., Zrenner R. (2011). Arabidopsis thaliana nucleosidase mutants provide new insights into nucleoside degradation. New Phytol. 191: 349–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock K.L., Kataoka H., Lai J.J. (2013). Uric acid as a danger signal in gout and its comorbidities. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 9: 13–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenwasser S., Rot I., Sollner E., Meyer A.J., Smith Y., Leviatan N., Fluhr R., Friedman H. (2011). Organelles contribute differentially to reactive oxygen species-related events during extended darkness. Plant Physiol. 156: 185–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholthof H.B. (1999). Rapid delivery of foreign genes into plants by direct rub-inoculation with intact plasmid DNA of a tomato bushy stunt virus gene vector. J. Virol. 73: 7823–7829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert K.R. (1986). Products of biological nitrogen-fixation in higher plants: Synthesis, transport, and metabolism. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. 37: 539–574. [Google Scholar]

- Serventi F., Ramazzina I., Lamberto I., Puggioni V., Gatti R., Percudani R. (2010). Chemical basis of nitrogen recovery through the ureide pathway: Formation and hydrolysis of S-ureidoglycine in plants and bacteria. ACS Chem. Biol. 5: 203–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y., Evans J.E., Rock K.L. (2003). Molecular identification of a danger signal that alerts the immune system to dying cells. Nature 425: 516–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg S.J., Dodt G., Raymond G.V., Braverman N.E., Moser A.B., Moser H.W. (2006). Peroxisome biogenesis disorders. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1763: 1733–1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theodoulou F.L., Eastmond P.J. (2012). Seed storage oil catabolism: A story of give and take. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 15: 322–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd C.D., Polacco J.C. (2006). AtAAH encodes a protein with allantoate amidohydrolase activity from Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta 223: 1108–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanner G., Vigil E.L., Theimer R.R. (1982). Ontogeny of microbodies (glyoxysomes) in cotyledons of dark-grown watermelon (Citrullus vulgaris Schrad.) seedlings: Ultrastructural evidence. Planta 156: 314–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner A.K., Witte C.P. (2011). The biochemistry of nitrogen mobilization: Purine ring catabolism. Trends Plant Sci. 16: 381–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner A.K., Medina-Escobar N., Zulawski M., Sparkes I.A., Cao F.Q., Witte C.P. (2013). The ureide-degrading reactions of purine ring catabolism employ three amidohydrolases and one aminohydrolase in Arabidopsis, soybean, and rice. Plant Physiol. 163: 672–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner A.K., Romeis T., Witte C.P. (2010). Ureide catabolism in Arabidopsis thaliana and Escherichia coli. Nat. Chem. Biol. 6: 19–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner A.K., Sparkes I.A., Romeis T., Witte C.P. (2008). Identification, biochemical characterization, and subcellular localization of allantoate amidohydrolases from Arabidopsis and soybean. Plant Physiol. 146: 418–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X., Wakamiya M., Vaishnav S., Geske R., Montgomery C., Jr, Jones P., Bradley A., Caskey C.T. (1994). Hyperuricemia and urate nephropathy in urate oxidase-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91: 742–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Han K.H. (2004). Functional characterization of allantoinase genes from Arabidopsis and a nonureide-type legume black locust. Plant Physiol. 134: 1039–1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yesbergenova Z., Yang G., Oron E., Soffer D., Fluhr R., Sagi M. (2005). The plant Mo-hydroxylases aldehyde oxidase and xanthine dehydrogenase have distinct reactive oxygen species signatures and are induced by drought and abscisic acid. Plant J. 42: 862–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolman B.K., Silva I.D., Bartel B. (2001). The Arabidopsis pxa1 mutant is defective in an ATP-binding cassette transporter-like protein required for peroxisomal fatty acid β-oxidation. Plant Physiol. 127: 1266–1278. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.