Abstract

Motivation: Automatic error correction of high-throughput sequencing data can have a dramatic impact on the amount of usable base pairs and their quality. It has been shown that the performance of tasks such as de novo genome assembly and SNP calling can be dramatically improved after read error correction. While a large number of methods specialized for correcting substitution errors as found in Illumina data exist, few methods for the correction of indel errors, common to technologies like 454 or Ion Torrent, have been proposed.

Results: We present Fiona, a new stand-alone read error–correction method. Fiona provides a new statistical approach for sequencing error detection and optimal error correction and estimates its parameters automatically. Fiona is able to correct substitution, insertion and deletion errors and can be applied to any sequencing technology. It uses an efficient implementation of the partial suffix array to detect read overlaps with different seed lengths in parallel. We tested Fiona on several real datasets from a variety of organisms with different read lengths and compared its performance with state-of-the-art methods. Fiona shows a constantly higher correction accuracy over a broad range of datasets from 454 and Ion Torrent sequencers, without compromise in speed.

Conclusion: Fiona is an accurate parameter-free read error–correction method that can be run on inexpensive hardware and can make use of multicore parallelization whenever available. Fiona was implemented using the SeqAn library for sequence analysis and is publicly available for download at http://www.seqan.de/projects/fiona.

Contact: mschulz@mmci.uni-saarland.de or hugues.richard@upmc.fr

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Next-generation DNA sequencing (NGS) technologies have revolutionized genomics and produce billions of base pairs per day in the form of reads of length ≥100 bp. In this article, we focus on NGS reads produced by genome sequencing. Owing to the large range of applications of genome sequencing, the correction of errors introduced by the sequencer, substitution as well as insertion or deletion (indels), has recently attracted attention. Previous studies showed that error correction can improve de novo genome assembly performance (Salmela and Schröder, 2011; Salzberg et al., 2012) and SNP detection (Kao et al., 2011; Kelley et al., 2010).

Depending on the technology, the most prevalent error type differs. Illumina technology produces mostly substitution errors (Minoche et al., 2011), whereas 454 sequencers are prone to produce runs of larger insertions of the same nucleotide. Ion Torrent sequencers were shown to have a large amount of indel errors and a high-sequencing error rate (Quail et al., 2012).

However, current error correction methods suffer a number of limitations as highlighted in a recent review (Yang et al., 2013). (i) Most methods cannot correct indel errors because they are tailored to correct only substitution errors and are therefore only applicable to Illumina reads. (ii) Most approaches need to be parameterized depending on the dataset, otherwise their performance is suboptimal. This either requires in-depth knowledge by the user or parameter optimization using downstream analysis, which often leads to longer running times in practice. (iii) Because the throughput of NGS technologies is growing steadily, many approaches are not applicable to larger datasets because of running time or memory limitations. These caveats make it hard for users to choose the optimal tool for their dataset and NGS technology.

Here we introduce a new approach to read error correction, called Fiona, which addresses all the above mentioned limitations. Fiona provides an accurate and highly parallelized method for correction, with the ability to correct indel errors, while it automatically adjusts its parameters.

All read error–correction methods have to perform essential tasks: (i) computation of read overlaps, (ii) error detection in reads and (iii) error correction. In a recent review by Yang et al. (2013), the methods have been classified into k-spectrum based, suffix tree/array based and multiple sequence alignment (MSA) based. We will briefly explain the differences and weaknesses of these approaches but refer the reader to (Yang et al., 2013):

k-spectrum based. k-spectrum based read error correction was introduced in the Euler assembler (Pevzner et al., 2001). There exist many variations on the k-spectrum based error corrections for NGS reads (Yang et al., 2013), for example, approaches that were designed to select the necessary parameters using mixture models (Chaisson and Pevzner, 2008; Kelley et al., 2010). Popular methods are Quake (Kelley et al., 2010), Reptile (Yang et al., 2010) and the error correction module from the Allpaths-LG assembler (Gnerre et al., 2010), all of which use base quality values. To our knowledge, only Allpaths-LG in this category can correct short indel errors.

The general disadvantage for most of these methods is their inability to correct indel errors, a severe limitation for 454 or Ion Torrent sequencers. In addition, for most of these approaches, parameters need to be optimized by the user to obtain good performance, for example, Reptile.

Suffix tree/array based. Shrec (Schröder et al., 2009) was the first approach that uses a variable seed length for read overlap and error-detection computation. It considers for each erroneous read a set of correcting reads such that all reads share a -mer left of the error and the set of correcting reads share a k-mer that ends with the correct base, which outvotes the erroneous base. To efficiently find erroneous reads and correcting candidates, Shrec traverses a generalized suffix tree of all reads, in which erroneous and correcting reads occur as children of branching nodes with string depth . Building on a suffix tree representation, the HybridShrec algorithm extended the ideas to correct indel errors and sequences in color space (Salmela, 2010). In both methods, potentially correcting reads are compared with erroneous reads using hamming distance, seeded by the shared -mers between reads. Further, both methods are sensitive to the input parameters and therefore show variable performance when compared in other studies (Ilie et al., 2011; Kao et al., 2011; Kelley et al., 2010), and the full suffix tree data structure needs large memory resources.

The HiTEC algorithm introduced automatic parameter selection using coverage statistics (Ilie et al., 2011). Seed lengths and coverage threshold are set automatically, given the genome length and the average error rate. HiTEC uses the suffix array instead of a suffix tree to save memory. However, HiTEC can only correct substitution errors and the automatic parameter selection works only for reads of same length as found for Illumina data.

Note that these methods do not define explicitly which correction for an erroneous position is applied when the same error is encountered multiple times through different seed lengths in the tree, and in which order errors in a read are corrected.

MSA based. Among the two existing multiple alignment-based methods ECHO (Kao et al., 2011) and Coral (Salmela and Schröder, 2011), only Coral can correct indel errors. Coral computes initial read overlaps with hash tables for a fixed k-mer length and then uses dynamic programming to form multiple read alignments. This alignment is costly for long reads but has a clear optimization function, as read errors are corrected by the best voting correction in the MSA.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

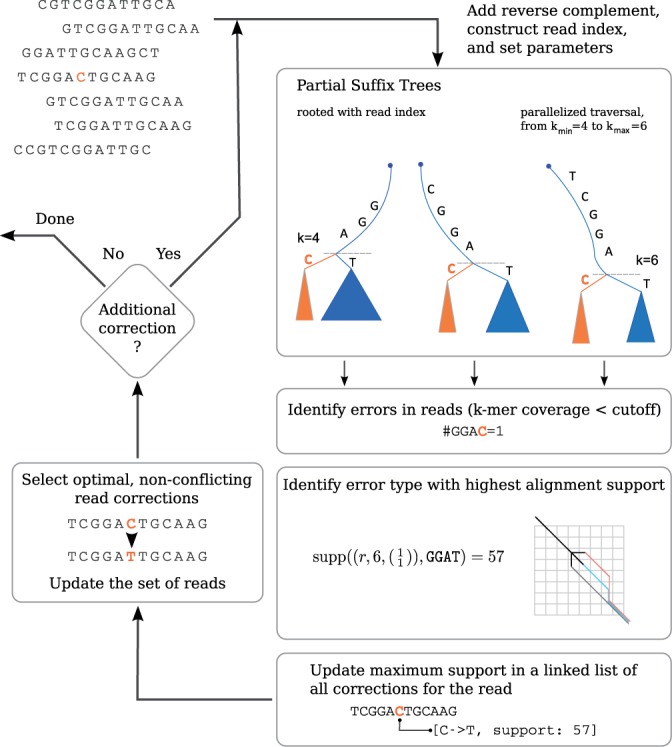

We introduce the Fiona algorithm, which combines the strength of suffix tree-based methods with a clear definition of error correction as in MSA-based methods. The algorithm uses a suffix tree to detect and correct substitution and indel errors following Shrec and HybridShrec, but with enhanced overlap detection of reads with indel errors using edit distance comparisons. In the implementation, the suffix tree traversal is emulated using solely a partial suffix array that is presorted up to a fixed depth to reduce the memory footprint. All steps feature a parallel implementation to scale with larger datasets. Instead of treating discovered errors independently, Fiona collects them and solves a new formulation for optimal error correction inspired by the MSA-based correction methods. Further, it uses new statistical methods to improve error detection at different k values and automatically estimates its parameters for reads of varying lengths as commonly found in 454 or IonTorrent data sets. The Fiona strategy is outlined in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

The Fiona strategy illustrated on a toy example. A set of partial suffix trees are built from the set of reads and their reverse complement (in fact partial suffix arrays are constructed, see Implementation). The trees are traversed in parallel to detect and correct errors. Potential errors in the reads are identified as nodes in the tree according to their coverage (e.g. the substring GGAC, covered by only one read). The correction with the highest support is chosen to correct the read at that position. Owing to the parallel traversal of the tree, all possible corrections on a read are recorded in a linked list, which reports the positions of corrections as well as their current maximal support. After traversal, the reads are updated by applying all non-conflicting corrections in order of decreasing support. Once all reads have been corrected, the algorithm repeats the procedure until the number of corrections have been achieved

Notations. Let [i, j] and (i, j) be closed and open ranges of integers. Further, let Σ be the DNA alphabet (, and N represents an unknown base) and s a string of |s| characters. The concatenation of two strings s and t is denoted by st. A substring of s from position i to j is the sequence . and denote, respectively, the reverse and the reverse complement of a DNA string s. We correct errors on a set of DNA strings of lengths , sampled from a genome of length n, possibly with sequencing errors. denotes the set of reverse-complemented reads. The edit distance ed(s, t) between two strings s and t is the minimal number of operations (substitutions, deletions and insertions) required to transform s into t.

In the following section, we describe how we use a suffix tree and a statistic on read coverage to find erroneous reads and correct them using the sequences they overlap. We then introduce our approach for detecting the type of error and choosing the optimal correction. Instead of immediately correcting errors as they are found, corrections are prioritized according to the support of their overlapping reads.

Searching erroneous reads

One essential ingredient in every sequencing error correction method is the statistic that computes which k-mers are erroneous, i.e. span at least one sequencing error in the read. Because new k-mers are generated when an error is introduced, their abundance or coverage is lower compared with k-mers from the genome. To detect a k-mer with a sequencing error, we compute the expected coverage assuming a uniform sampling of genomic positions. We use a hierarchical statistical model to describe the expected coverage distribution of k-mers resulting from library preparation and sequencing as follows. Let Xk be the random variable for the number of occurrences of a string of length k in the population of sequence fragments before sequencing. Xk is never directly observed, instead the occurrences of k-mers in the reads after sequencing, denoted Yk, are observed with a given number of sequencing errors z.

For every k-mer covered by c reads, we classify it as possessing errors based on the sign of the log odds ratio (positive value for erroneous k-mers):

| (1) |

The constant w can be modified to adjust the sensitivity of the detection. To match the setup of a naive Bayes classifier, we use the log-odds ratio of the probability that the k-mer has errors compared with the probability that the k-mer has no error: As we will show in the following the user only needs to supply the genome length n and the average error rate ε to the method. The method can then infer the coverage cutoff and the range of k-mers to explore.

Coverage distribution of k-mers.

The counts Xk are drawn according to binomial sampling along each position in . If we assume the sampling to be uniform, and that any word of length k is unique in , the expected count of a k-mer λk is

| (2) |

As n is usually large, Xk can be approximated by a Poisson distribution of rate λk. Note that the assumption that a word is unique in is vital because repeats in will have a higher λk. We restrict ourselves to this hypothesis in the following, as errors derived from repeats are difficult to infer based exclusively on their coverage. Therefore, we have an additional filter to remove words that originate from repetitive regions (see Implementation).

If we assume a uniform error rate of ε at each base (thus a probability of for each substitution), we can derive the expected count for a given k-mer, given its number of sequencing errors, i.e. the distribution of . The coverage of a k-mer possessing i sequencing errors is distributed according to a Poisson distribution with an expectation of

| (3) |

Note that this formulation does not incorporate cases where errors would accumulate on other reads in the neighborhood of the k-mer. This effect can be neglected given the relatively low error rate of current sequencers (<5%).

The distribution of Yk can be obtained by summing over the possible number of errors, which results in a mixture of Poisson distributions with rates μi. We denote the proportion of reads with exactly i errors as

| (4) |

which we call the mixture coefficients. It follows the formulation for Yk:

| (5) |

Note that without the i = 0 term, this formulation denotes the distribution for reads with at least one error.

Choosing the k-mer range.

In our error correction formulation we seed the alignments with different seed lengths in the interval . The minimal value kmin should neither be too small, to reduce influence from repetitive sequences, nor too large, as many erroneous reads may be missed otherwise. In Fiona, we extend a technique proposed by the authors of HiTEC (Ilie et al., 2011) to determine the best value for kmin, balancing the sensitivity of a seed and its accuracy, and modify it to account for heterogeneous read lengths (Supplementary Section S1). Note that our use of the [kmin, kmax] values differs compared with HiTEC because in Fiona we always choose the best corrections in the interval [kmin, kmax] in each round.

Detecting the type of error

With the statistic described in the previous section we now search the generalized suffix tree of for nodes α at level that branch into an erroneous and a correct k-mer, let the latter be αx with .

For each read r in the erroneous subtree, we search for possible corrections in the correct subtrees. If i is the position of the error, obviously and we can use the set of overlapping correct reads to determine the type of error at i: substitution, insertion or deletion. We use the spectrum of the correct k-mer αx to select possible correcting reads.

The spectrum of a string t is defined as the set of pairs (s, j) such that and (the set of positions in reads ending with the string t). For each read s in the spectrum , we extend the seed α to the right with minimal edit distance using an alignment algorithm until the end of either r or s is reached.

We define the right extension of two strings a and b as a pairwise alignment of one string to a prefix of the other. E(a, b) denotes the number of errors in an optimal right extension of a and b:

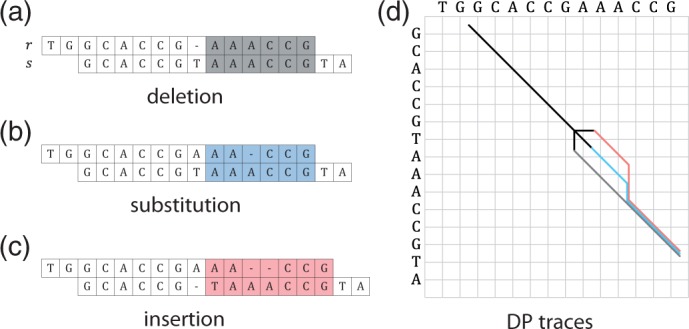

Considering the three possible types of error, we assume that skipping the actual error yields an optimal extension of the remaining suffixes. Hence, for we skip e1 bases from position i in r and e2 bases from position j in s and examine which value of e yields an optimal extension, i.e. a minimal value . Figure 2 gives an example where yields an optimal extension.

Fig. 2.

Example for detecting the type of error. Given an erroneous read r and a correct read s, that share a 3-mer anchor CCG that cannot be extended to the right. For each possible error type, deletion (a), substitution (b) and insertion (c), we skip 0 or 1 bases in r or s and compute DP overlap alignments of the remaining suffixes (shaded). The corresponding DP traces of the three alignments are shown below (d) with colors matching the overlap regions. The error type with the least number of errors in the overlap, here the deletion with 0 errors, is assumed to be the true error

We determine the actual error by a majority vote over all correct reads:

Thus, V(e) is the set of correct reads (or more precisely of correct anchors) that vote for e, i.e. can be optimally extended incorporating error e. We choose the error type that maximizes |V(e)|. In case of ties, we prefer substitutions over indels and deletions over insertions. As an additional criterion to reduce false positives, we consider only correct reads within a given overlap error rate.

Selecting optimal read corrections

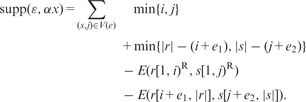

In contrast to other approaches that consider a fixed seed length, we examine potential errors over a whole range of seed lengths and therefore need a way to select the overall most probable error among them. For an error, summarized by the tuple , we define the support as the number of matching base pairs in overlap alignments between r and correct reads voting for e at position i:

|

supp is computed for all reads that vote for error type e, by subtracting from the total overlapping bases (left and right) the number of errors in the overlap [given by ]. During the traversal we maintain a data structure that stores the maximal and its corresponding correction. After tree traversal, we sort for each read r the list of errors by decreasing support, apply the first correction and continue with the next non-conflicting correction (a conflicting correction is a correction which would destroy the seed of one previously applied correction).

Note that this definition of error correction is different from the correction approaches in the other suffix tree based algorithms (Ilie et al., 2011; Salmela, 2010; Schröder et al., 2009) because these do not maximize over a range of seed lengths for one correction and do not maximize the support of corrections for an individual read. Rather, their algorithms can detect errors at different seed lengths, but correct an error in read r for an arbitrary k, solely determined by its first encounter in the suffix tree. This makes Fiona the only approach to use a definition of optimality for different seed lengths.

Implementation

We implemented Fiona in C++ using SeqAn (Döring et al., 2008). We emulate the suffix tree traversal with a suffix array and exploit a one-to-one correspondence of suffix tree nodes at string depth ℓ and ℓ-intervals in the suffix array (Abouelhoda et al., 2004) where (i) the suffixes in the interval are the leaves of the node’s subtree and (ii) the suffix tree path from the root to the node spells out the longest common prefix of the interval suffixes. We parallelized the construction and traversal of the suffix array using OpenMP, exploiting the fact that we do not need to explicitly construct the arrays for suffixes shorter than . Reticulating the tree this way allows to control memory usage and to process suffixes step-wise in chunks. In practice we refine a 10-mer index up to a sorted prefix of length . Seed extension and computation of the values is done with a banded variant of Myers’ bitvector algorithm for fast edit distance computation. For parallel access of the found corrections and their support in each read, we implemented a concurrent linked list data structure. Finally, repeats are accounted for by filtering out suffixes with too high coverage or containing tandem repeats. More implementation details, as well as worst case and expected time and memory complexities, can be found in Supplementary Section S2.

3 RESULTS

We performed a comprehensive experimental evaluation of Fiona and other tools on various real-world read sets. For the evaluation of read correction quality, the metric gain has been established in (Yang et al., 2010, 2013) as a good summary of both sensitivity and precision. The gain can be computed by where a and b are the sums over the number of errors after and before correction over all reads. When more errors are introduced than corrected over all the reads, the gain takes a negative value. For the evaluation, we developed a tool compute_gain, which is included in the Fiona distribution (Supplementary Section S3.2)

To cover most of the use cases nowadays, we evaluated the accuracy on read sets from 454, IonTorrent and Illumina sequencers that show a varying degree of read lengths (mean values from 92 to 544 bp) and depth of coverage (up to 490×). We selected datasets for a diverse set of organisms to explore the impact of genome complexity and repeat content on error correction performance, from short genomes (Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas syringae) to longer and more complex ones (Drosophila melanogaster, Homo sapiens). Further details about all datasets and the evaluation are given in Supplementary Section S3.

The only variable parameter besides the input read set given to Fiona is the estimated genome length (Supplementary Table S1). Fiona was run with default parameters for all datasets, i.e. the sequencing error rate was 5% and the presorting q-gram length was set to 10.

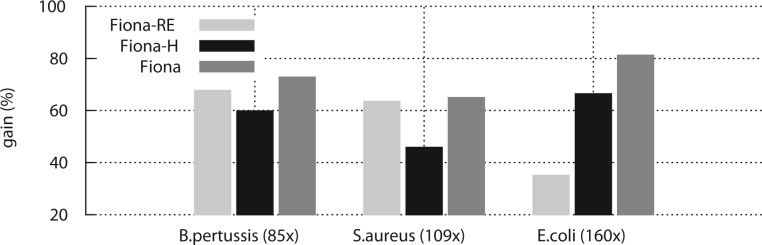

Optimal error formulation improves correction accuracy

As mentioned in the introduction, the previous suffix tree based error correction approaches use the correction for a read that is first encountered during tree traversal and neither store all possible corrections nor choose the optimal one.

Although we compare with HybridShrec later, which uses such a strategy, it is not straightforward to analyze the advantage of our new formulation of optimal error correction because HybridShrec further differs in the way errors are detected. Therefore, we implemented two special versions of Fiona to illustrate the improvement of our approaches. In the first, for each read position only the first correction encountered during traversal is stored, after each round the corrections are executed in the order they were found. We term this version Fiona-RE, for random encounter mode. The second, implements a version of Fiona that does all optimizations but compares two reads using hamming distance, instead of pairwise edit distance computation (Fiona-H). Note that Fiona-H does correct indel errors, as found at branching nodes in the tree, but no further indels are considered in the pairwise read alignment. We compare Fiona, Fiona-H and Fiona-RE on data sets with different regimes of coverage and genome complexity in Figure 3. The results show that Fiona-H, without edit distance pairwise comparison, usually shows a drop in gain value of 13–19%. This is due to a loss of sensitivity, where two reads that have several other indel errors downstream or upstream are not judged similar enough to be considered for correction. The optimal error formulation in Fiona, compared with random encounter mode in Fiona-RE, shows a pronounced improvement in error correction for more complex genomes and higher coverages as on the E.coli 163× and Bordetella pertussis 85× datasets.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of gain values after error correction with new optimality criterion introduced in Fiona and corrections without optimization (Fiona-RE), or without edit distance overlap computation (Fiona-H) as performed by other suffix treebased methods. The results are for three different datasets with varying coverage values: B.pertussis (85×), S.aureus (109×), E.coli (160×) (see Supplementary Table S2). Optimal corrections always lead to higher gain values

Robustness

Fiona uses different statistical formulas to infer the optimal correction parameters (see Section 2). We analyzed the robustness of error correction results on two datasets by varying the user-supplied sequencing error rate between 2 and 10%. Fiona produces corrections of similar quality with difference in gain value <15%, despite the large range of error rates tested, which indicates robust automatic parameter selection (see Supplementary Table S3). Note that the gain is generally better when the error rate is overestimated. This can be explained by the variability of read quality observed in the sequencing sample, i.e. an average error rate does not account for the other reads of low quality.

Comparison with other methods

We compared the performance of Fiona with state-of-the-art genome error correction methods for the respective type of sequencing technology. For 454 and Ion Torrent datasets, we compared with Coral 1.4, Hybrid-Shrec 1.0 and the error correction module of Allpaths-LG release 44994, which can correct indel errors. For Illumina, we add the tools HiTEC 1.0.2 and Quake 0.3.4.2, which are designed for substitution errors. We did not include HybridShrec in those evaluations, as it consistently performed worse than HiTEC. In any case, all programs were run with eight threads if possible. The detailed parameterization of the programs is listed in Supplementary Section S5. Except ECHO and HiTEC, which do automatic parameter selection similar to Fiona, no other correction method adapts parameters depending on the data. But whereas Allpaths-LG has a fixed set of parameters, Coral and HybridShrec expect the user to optimize its parameters for indel-prone datasets, which we did to allow for a fair comparison. For Coral, we report the results of two versions, Coral and Coral*, the default version with error rate set to 7% and the optimized version with the best-performing gain and error rate set as high as 25%, respectively (Supplementary Tables S8–S11). Coral* performed better than Coral on all datasets tested, clearly indicating the need for parameter adjustment for indel-prone datasets. HybridShrec has three parameters that have substantial influence on its performance, the strictness parameter for error detection and the minimum and maximum k-value for suffix tree traversal. As HybridShrec often terminates with default strictness value we have varied this parameter between values of 2–7 and took the best result. Consequently, we report the results as HybridShrec*. The same was done for HybridShrecF, which uses the same k value range as determined by Fiona for a dataset. Even with the optimized set of parameters we explored, HybridShrec sometimes yields negative gain values. The optimized parameters for HybridShrec*, HybridShrecF and Coral* are listed in Supplementary, Sections S9 and S8.

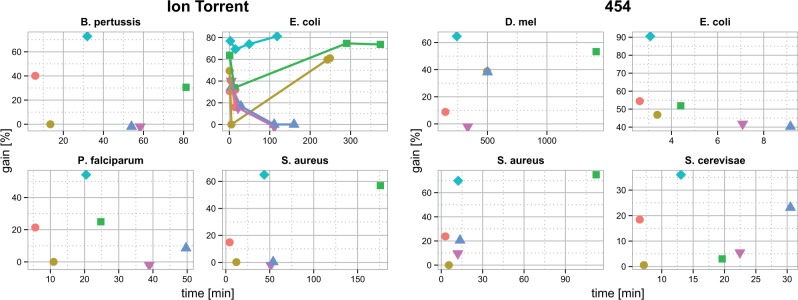

We have evaluated all methods on different datasets and list their relative performance in terms of gain, sensitivity, specificity, base error rate after correction, running time and memory in Tables 1 and 2. and Supplementary Tables S4–S7, respectively. Further, we relate the error correction performance to running time of a method in Figure 4, where the best method appears in the upper left corner.

Table 1.

Performance on 454 (top) and IonTorrent (bottom) datasets

| Original | Allpaths-LG |

Coral |

Coral* |

Fiona |

HybridShrec* |

HybridShrecF |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dataset | e-rate | e-rate | gain | e-rate | gain | e-rate | gain | e-rate | gain | e-rate | gain | e-rate | gain | |

| D.melanogaster | 18× | 1.17 | 1.07 | 8.87 | 0.72 | 38.81 | 0.55 | 53.30 | 0.42 | 64.62 | 4.46 | −279.51 | 0.73 | 38.17 |

| E.coli K-12 | 13× | 1.06 | 0.74 | 30.68 | 0.54 | 49.42 | 0.38 | 63.79 | 0.25 | 76.88 | 0.64 | 40.05 | 0.70 | 34.28 |

| S.aureus | 34× | 1.76 | 1.34 | 23.85 | 1.76 | 0.00 | 0.44 | 74.90 | 0.53 | 69.87 | 1.59 | 9.62 | 1.40 | 20.50 |

| S.cerevisae | 16× | 0.95 | 0.78 | 18.45 | 0.95 | 0.56 | 0.92 | 2.99 | 0.61 | 36.04 | 0.90 | 5.48 | 0.73 | 23.11 |

| B.pertussis | 85× | 3.71 | 2.22 | 40.13 | 3.71 | 0.02 | 2.57 | 30.60 | 1.01 | 72.83 | 12.44 | −235.48 | 4.07 | −9.68 |

| E.coli K-12 | 8× | 0.62 | 0.28 | 54.46 | 0.33 | 46.86 | 0.30 | 51.86 | 0.06 | 90.52 | 0.36 | 41.81 | 0.37 | 40.26 |

| E.coli K-12 | 163× | 1.46 | 1.23 | 15.99 | 0.59 | 59.70 | 0.38 | 73.72 | 0.27 | 81.24 | 1.73 | −18.90 | 1.46 | 0.00 |

| E.coli K-12 | 156× | 1.11 | 0.75 | 31.98 | 0.43 | 61.07 | 0.28 | 74.70 | 0.29 | 74.06 | 1.38 | −24.15 | 1.11 | 0.00 |

| E.coli O104:H4 | 32× | 5.19 | 3.09 | 40.53 | 5.19 | 0.00 | 3.44 | 33.82 | 1.59 | 69.33 | 4.39 | 15.36 | 4.31 | 16.76 |

| H.sapiensa | 11× | 1.62 | 1.44 | 11.52 | —b | —b | 0.87 | 46.68 | —b | —b | ||||

| P.falciparum 3D7 | 13× | 5.06 | 3.97 | 21.39 | 5.05 | 0.03 | 3.80 | 24.94 | 2.33 | 54.12 | 7.67 | −51.29 | 4.63 | 8.50 |

| S.aureus | 109× | 3.32 | 2.83 | 14.89 | 3.32 | 0.24 | 1.44 | 56.91 | 1.17 | 64.94 | 3.77 | −13.44 | 3.31 | 0.32 |

Note: aThe programs were run on machine with 16 physical and 32 virtual cores and 370 GB of RAM. bOut of memory—The table shows the base error rate (e-rate, in percent) before and after correction with the methods as well as the gain statistic. For each dataset, the results with the best gain value are highlighted in bold. The results are separated by sequencing technology, the 454 results are above the IonTorrent results.

Table 2.

Running time and memory consumption for 454 (top) and IonTorrent (bottom) experiments

| Allpaths-LG |

Coral |

Coral* |

Fiona |

HybridShrec* |

HybridShrecF |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dataset | Gbp | time | mem | time | mem | time | mem | time | mem | time | Mem | time | mem | |

| D.melanogaster | 18× | 2.2 | 145.0 | 11 | 496.1 | 59 | 1414.1 | 60 | 240.7 | 18 | 333.2 | 41 | 499.5 | 42 |

| E.coli K-12 | 13× | 0.06 | 1.0 | 0 | 0.8 | 3 | 0.9 | 3 | 2.5 | 1 | 4.8 | 5 | 5.0 | 12 |

| S.aureus | 34× | 0.1 | 3.0 | 1 | 5.5 | 5 | 112.2 | 5 | 12.3 | 1 | 12.0 | 14 | 13.6 | 15 |

| S.cerevisae | 16× | 0.19 | 6.5 | 1 | 7.1 | 5 | 19.6 | 5 | 13.1 | 2 | 22.5 | 15 | 30.5 | 15 |

| B.pertussis | 85× | 0.3 | 6.0 | 2 | 13.5 | 9 | 81.2 | 9 | 32.0 | 3 | 58.3 | 17 | 54.0 | 21 |

| E.coli K-12 | 8× | 0.04 | 2.6 | 0 | 3.4 | 3 | 4.4 | 3 | 3.1 | 1 | 7.1 | 5 | 9.2 | 8 |

| E.coli K-12 | 163× | 0.8 | 14.2 | 4 | 243.0 | 13 | 373.8 | 13 | 118.3 | 9 | 111.3 | 19 | 160.2 | 6 |

| E.coli K-12 | 156× | 0.7 | 15.0 | 7 | 249.1 | 12 | 290.1 | 12 | 49.2 | 8 | 111.4 | 18 | 111.0 | 6 |

| E.coli O104:H4 | 32× | 0.2 | 3.8 | 1 | 5.3 | 8 | 12.6 | 8 | 15.2 | 2 | 21.7 | 15 | 28.7 | 16 |

| H.sapiensa | 11× | 31.5 | 572.8 | 129 | —b | —b | 1187.1 | 244 | —b | —b | ||||

| P.falciparum | 13× | 0.3 | 5.6 | 1 | 11.0 | 11 | 24.8 | 11 | 20.5 | 3 | 38.9 | 16 | 49.7 | 20 |

| S.aureus | 109× | 0.31 | 4.4 | 1 | 12.0 | 13 | 175.8 | 13 | 43.7 | 3 | 51.1 | 18 | 53.8 | 29 |

Note: aThe programs were run on machine with 16 physical and 32 virtual cores and 370 GB of RAM. bOut of memory—Time (in minutes and fractions thereof) and memory (in GB, rounded to the next GB) for the read correction runs from Table 1. For each dataset, the results with the lowest running time and memory are given in bold. The results are separated by sequencing technology; the 454 results are above the IonTorrent results.

Fig. 4.

Scatterplots that show achieved gain and running time for Allpaths-LG (orange filled circles), Coral (dark yellow filled circles), Coral* (green filled squares), Fiona (turquoise filled dimonds), H-Shrec (blue filled triangles), and H-Shrec* (green filled triangles) on the various datasets for Ion Torrent (left) and 454 (right) technologies. The best-performing method appears in the upper left corner of a plot. Gain values below zero were arbitrarily reassigned a value of −1. In the case of E.coli, values for the four datasets for each tool are connected by a line

Comparison on 454 data.

We have collected four different 454 dataset with different coverage values for D.melanogaster 18×, E.coli 13×, Staphylococcus aureus 34× and Saccharomyces cerevisae 16×. These datasets vary in the per-base error rate between 0.6 and 1.76%. Errors are often found in sequence regions with homopolymer runs, which are hard to correct (Quail et al., 2012). We observe that the optimized version of Coral* always outperforms the default parameters (Coral) on 454 data sets. Similarly, HybridShrecF mostly outperforms the optimized HybridShrec*, owing to adapted k-mer levels for each dataset. Similar to Yang et al. (2013), we observe that HybridShrec sometimes yields negative gain values, i.e. that more errors are introduced than corrected. As Figure 4 (right) shows Fiona has the highest gain among all methods except for the S.aureus dataset, where Coral* performs best. However, Coral* runs ∼10 times longer than Fiona on this dataset. Allpaths-LG generally is the fastest or among the fastest methods, but with a loss in gain performance between 90 and 50% compared with Fiona. Fiona shows a fast running time for all datasets, and is also memory efficient compared with the Coral and HybridShrec versions.

Comparison on Ion Torrent data.

We next compared the performance of the different methods on the eight Ion Torrent datasets. On seven of eight datasets, Fiona significantly outperforms the other methods in terms of gain. Fiona shows an increase in gain to the second best method ranging from 10 (E.coli 163×) to 56% (Plasmodium falciparum). For the human dataset, only Allpaths-LG and Fiona could be run with the available memory, with a gain improvement of 35% for Fiona. Only for the E.coli (156×) dataset Fiona and Coral* have comparable gain values, although Fiona runs approximately six times faster. Except for Fiona, all methods show a large variation in their ability to correct errors as shown in fluctuations of their gain values. For example, all datasets with an error rate >3.3% are poorly corrected when using Coral default parameters.

In these evaluations, Allpaths-LG uses the lowest amount of memory. Fiona’s memory usage scales linearly with the dataset size (Supplementary Table S2), which is in line with the expected memory consumption (Supplementary Section S2.6).

Comparison on Illumina data.

To show that Fiona is on par with methods that are optimized for Illumina data, we made comparisons on seven datasets. We compared Fiona-H, the version that corrects indels but only considers hamming pairwise read distance (Fiona-H) to Coral, Allpaths-LG, HiTEC and ECHO. On all datasets, Fiona-H and Allpaths-LG are the best two methods in terms of gain, with Fiona always being among the two first-ranked methods (Table 3). Fiona-H outperforms Allpaths-LG with a significant increase in gain of 17% on the D.melanogaster 5× and P.syringae 41× datasets. Conversely, Allpaths-LG ranks first, with a gain increase of 1–3.5% over Fiona-H on D.melanogaster 28×, E.coli 30× and the Caenorhabditis elegans dataset. Of the remaining methods, Quake ranks second two times and third five times. In Supplementary Table S5, we list the runtime and memory consumption for these comparisons. Fiona-H scales well with dataset size and has lower memory consumption than HiTEC and Coral. Allpaths-LG and Quake were the fastest methods in our comparisons, with Fiona-H ranking third most of the time. Of the remaining methods, Quake ranks second two times and third five times. This can be explained by the fact that Fiona examines an error at various seed lengths, whereas fixed-length seed methods examine it at most once.

Table 3.

Performance on Illumina datasets

| Original | Allpaths-LG |

Coral |

ECHO |

Fiona-H |

HiTEC |

Quake |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dataset | e-rate | e-rate | gain | e-rate | gain | e-rate | gain | e-rate | gain | e-rate | gain | e-rate | gain | |

| C.elegans | 30× | 0.4404 | 0.3152 | 28.42 | 0.5173 | −17.45 | —a | 0.3292 | 25.24 | —b | 0.3881 | 14.02 | ||

| D.melanogaster | 5× | 1.3244 | 0.8900 | 32.80 | 0.7187 | 45.73 | 0.7652 | 42.22 | 0.6587 | 50.26 | 1.0080 | 23.89 | 0.7342 | 46.95 |

| D.melanogaster | 28× | 1.1065 | 0.7509 | 32.13 | 0.7727 | 30.16 | —a | 0.7592 | 31.39 | —b | 0.8005 | 29.09 | ||

| E.coli K-12 | 30× | 0.2070 | 0.0015 | 99.29 | 0.0178 | 91.40 | 0.0184 | 91.12 | 0.0043 | 97.91 | 0.0141 | 93.18 | 0.0094 | 95.55 |

| E.coli K-12 | 490× | 0.2070 | 0.0036 | 98.24 | 0.0084 | 95.69 | —b | 0.0028 | 98.66 | 0.0128 | 93.81 | 0.0077 | 96.35 | |

| P.syringae | 42× | 0.5984 | 0.1531 | 74.41 | 0.1491 | 75.08 | 0.0533 | 91.09 | 0.0517 | 91.36 | 0.1351 | 77.42 | 0.1219 | 79.65 |

| S.cerevisae | 22× | 0.4101 | 0.1803 | 56.04 | 0.2713 | 33.86 | 0.2777 | 32.30 | 0.1686 | 58.89 | 0.5045 | −23.00 | 0.1963 | 52.15 |

Note: This table shows the same metrics as Table 1. aThe program ran too long—The problems were Coral and HiTEC produced a segfault, requiring more than 72 GB of memory. bThe program crashed. ECHO was killed after running more than 4 days in the case of C.elegans and D.melanogaster datasets and the subprogram NeighborJoin crashed on the full E.coli dataset;

4 DISCUSSION

In this study, we introduced Fiona, a new algorithm for the correction of sequencing errors without the need for a reference sequence. Fiona builds over existing strategies to accurately correct errors, accounting for indels with automatic parameter selection. One of the main advantages of Fiona is the use of variable seed lengths, combined with a global optimization criterion to choose the best correction for a read. Our experiments show that Fiona outperforms other methods on datasets from different sequencing technologies.

For the evaluation of the different error correction methods we chose to use the gain statistic that is commonly used for this task. However, evaluating the accuracy of nucleotide corrections based on the available reference sequence can be misleading, as haplotype variants may be penalized and therefore the number of false-positive/negative corrections inflated. Despite this disadvantage, the comparison should not favor any method because all compared methods work exclusively on the read set without alignment to the reference sequence.

We introduced a new statistic for error detection that uses a hierarchical model for the stepwise process of first selecting a subset of reads from a genome and then introducing errors during sequencing. This formulation provides an easily extendible framework and can be extended to accommodate more general scenarios, like the presence of heterozygous positions in diploid genomes, coverage overdispersion or the distribution of repeat elements, as well as base quality values.

For our experiments, we fixed the error rate estimate to 5% for indel-prone datasets and show that reasonable variations to this value lead to minor performance differences. In principle, the error rate could be estimated from the base-calling procedure of the sequencer. Alternatively, it could be estimated from the raw sequencing data in a preprocessing step as was recently shown by Wang et al. (2012) for Illumina data. Further research on how to determine sequencing error rates in the context of de novo assemblies, where no reference sequence is available, is necessary.

In conclusion, Fiona is a reliable method that automatically determines parameters, corrects indels and scales well to large datasets. We believe that users will improve their downstream analysis by using Fiona in their pipelines and made it publicly available at http://www.seqan.de/projects/fiona.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank Enrico Siragusa for his partial suffix array implementation.

Funding: The initial part of the project for M.H.S. was funded by the IMPRS-CBSC Berlin. M.H. and D.W. were supported by the BMBF [16V0080]. H.R. was partly funded by a JSPS [PE11014] fellowship.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Abouelhoda M, et al. Replacing suffix trees with enhanced suffix arrays. J. Discrete Alg. 2004;2:53–86. [Google Scholar]

- Chaisson MJ, Pevzner PA. Short read fragment assembly of bacterial genomes. Genome Res. 2008;18:324–330. doi: 10.1101/gr.7088808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Döring A, et al. SeqAn an efficient, generic C++ library for sequence analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnerre S, et al. High-quality draft assemblies of mammalian genomes from massively parallel sequence data. PNAS. 2010;108:1513–1518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017351108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilie L, et al. HiTEC: accurate error correction in high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:295–302. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao W, et al. ECHO: a reference-free short-read error correction algorithm. Genome Res. 2011;21:1181–1192. doi: 10.1101/gr.111351.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley DR, et al. Quake: quality-aware detection and correction of sequencing errors. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R116. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-11-r116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minoche A, et al. Evaluation of genomic high-throughput sequencing data generated on Illumina HiSeq and Genome Analyzer systems. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R112. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-11-r112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pevzner PA, et al. An eulerian path approach to dna fragment assembly. PNAS. 2001;98:9748–9753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171285098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quail M, et al. A tale of three next generation sequencing platforms: comparison of Ion Torrent, Pacific Biosciences and Illumina MiSeq sequencers. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:341. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmela L. Correction of sequencing errors in a mixed set of reads. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:1284–1290. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmela L, Schröder J. Correcting errors in short reads by multiple alignments. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:1455–1461. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzberg SL, et al. GAGE: a critical evaluation of genome assemblies and assembly algorithms. Genome Res. 2012;22:557–567. doi: 10.1101/gr.131383.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder J, et al. SHREC: a short-read error correction method. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2157–2163. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XV, et al. Estimation of sequencing error rates in short reads. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012;13:185. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, et al. Reptile: representative tiling for short read error correction. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2526–2533. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, et al. A survey of error-correction methods for next-generation sequencing. Brief. Bioinform. 2013;14:56–66. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbs015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.