Abstract

Motivation: Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and cancer require personalized therapies owing to their inherent heterogeneous nature. For both diseases, large-scale pharmacogenomic screens of molecularly characterized samples have been generated with the hope of identifying genetic predictors of drug susceptibility. Thus, computational algorithms capable of inferring robust predictors of drug responses from genomic information are of great practical importance. Most of the existing computational studies that consider drug susceptibility prediction against a panel of drugs formulate a separate learning problem for each drug, which cannot make use of commonalities between subsets of drugs.

Results: In this study, we propose to solve the problem of drug susceptibility prediction against a panel of drugs in a multitask learning framework by formulating a novel Bayesian algorithm that combines kernel-based non-linear dimensionality reduction and binary classification (or regression). The main novelty of our method is the joint Bayesian formulation of projecting data points into a shared subspace and learning predictive models for all drugs in this subspace, which helps us to eliminate off-target effects and drug-specific experimental noise. Another novelty of our method is the ability of handling missing phenotype values owing to experimental conditions and quality control reasons. We demonstrate the performance of our algorithm via cross-validation experiments on two benchmark drug susceptibility datasets of HIV and cancer. Our method obtains statistically significantly better predictive performance on most of the drugs compared with baseline single-task algorithms that learn drug-specific models. These results show that predicting drug susceptibility against a panel of drugs simultaneously within a multitask learning framework improves overall predictive performance over single-task learning approaches.

Availability and implementation: Our Matlab implementations for binary classification and regression are available at https://github.com/mehmetgonen/kbmtl.

Contact: mehmet.gonen@sagebase.org

Supplementary Information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and cancer, which are two major human diseases causing millions of deaths yearly, require ‘personalized therapies’ owing to their inherent heterogenous nature. For both diseases, large-scale pharmacogenomic screens have been performed with the hope of discovering associations between genetic subtypes of each disease and drug susceptibility (Barretina et al., 2012; Garnett et al., 2012; Rhee et al., 2003).

HIV is usually treated with antiretroviral therapies, which have demonstrated high efficacy. However, the high mutation rate of HIV helps the virus adapt fast, leading to drug-resistant viral strains. Thus, selecting the optimal therapeutic regimen for a given HIV strain requires the ability to predict drug resistance based on its genomic sequence. To enable this type of discovery, Rhee et al. (2003) characterize the susceptibility of >1000 genomically sequenced HIV strains to subsets of multiple HIV therapeutic agents.

Cancer is a collection of genetically diverse diseases, and many modern cancer therapeutics have demonstrated selective efficacy in specific matched genetic subtypes (Druker et al., 2001). Thus, patient selection strategies for personalized cancer therapeutics require the ability to predict drug sensitivity based on molecular information about a patient’s tumor. For this purpose, Barretina et al. (2012) and Garnett et al. (2012) characterize the sensitivity of >500 molecularly profiled cancer cell lines to 24 and 138 anticancer compounds, respectively.

For both HIV and cancer, researchers have developed genomic predictors of drug susceptibility using modern machine learning techniques for high-dimensional classification or regression. For example, Rhee et al. (2006) use machine learning algorithms such as decision trees, artificial neural networks, support vector machines, least squares regression and least angle regression to predict drug resistance in HIV type 1 (HIV-1) using the sequence of the viral reverse transcriptase. Barretina et al. (2012) and Garnett et al. (2012) use a regularized regression method (elastic net) to predict drug sensitivities based on cancer cell line molecular profiles, and Neto et al. (2014) formulate a Bayesian extension of this approach in a recent study. Menden et al. (2013) combine genomic features of cell lines and chemical features of drugs for sensitivity prediction using a neural network approach. Jang et al. (2014) and Papillon-Cavanagh et al. (2013) compare the performance of various machine learning methods applied to the cancer cell line datasets.

One potential limitation of these approaches is the formulation of a separate learning task for each drug. In particular, because each pharmacogenomic screen profiles multiple drugs with similar mechanisms of action, leveraging information across multiple related drugs may yield improved model robustness by reducing the impact of ‘off-target effects’ and drug-specific experimental noise. Moreover, methods that jointly model sensitivity profiles across multiple drugs may yield insights into groups of drugs effecting similar biological processes or infer mechanisms of action for uncharacterized compounds. For example, Wei et al. (2012) combine elastic net regression with an expectation maximization algorithm to simultaneously cluster groups of similarly behaving compounds and infer a predictive model for each cluster. Heider et al. (2013) formulate predicting drug resistance against a panel of HIV-1 drugs as a ‘multilabel learning’ problem (Tsoumakas et al., 2010), which aims to use all available information by learning models for all drugs simultaneously. They show that this joint modeling approach is better than independent modeling in terms of predictive performance. However, their algorithm has some limitations: (i) It is based on the classifier chains formulation (i.e. training separate predictors for all drugs successively linked along a chain) (Read et al., 2011), which is not sufficient to capture more complex dependencies between drugs. (ii) It assumes that each data point have the corresponding drug resistance score for all of the drugs considered (i.e. no missing output), which limits the applicability of the proposed method because, in large-scale pharmacogenomic assays, there may be many missing values owing to experimental conditions, quality control reasons, etc.

For predicting drug susceptibility against a panel of drugs, we propose a novel Bayesian formulation that combines kernel-based non-linear dimensionality reduction (Schölkopf and Smola, 2002) and binary classification (or regression) in a ‘multitask learning’ framework (Caruana, 1997), which tries to solve distinct but related tasks jointly to improve overall generalization performance. Our proposed method, called ‘kernelized Bayesian multitask learning’ (KBMTL), has two key properties: (i) It maps all data points into a shared subspace and learns predictive models for all drugs simultaneously in this subspace to capture commonalities between the drugs. Joint modeling of drugs enables us to eliminate off-target effects and drug-specific experimental noise, leading to a better predictive performance. (ii) It can handle missing values of drug susceptibility measurements, which enables us not to discard data points with missing outputs, leading to larger data collections. As a result, the obtained predictions become more robust especially for drugs with a large number of missing phenotype values.

To show the performance gain of our method over standard modeling approaches, we perform cross-validation experiments on two benchmark drug susceptibility datasets of HIV and cancer.

2 MATERIALS

In this study, we use two different drug susceptibility datasets, which we extract from the following sources: (i) HIV Drug Resistance Database (HIVDB) (Rhee et al., 2003), (ii) Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC) (Yang et al., 2013). These two data sources are publicly available at http://hivdb.stanford.edu and http://www.cancerrxgene.org, respectively.

2.1 HIV drug resistance database

HIVDB contains phenotype and genotype information about HIV-1 (i.e. viral reverse transcriptase sequences with corresponding susceptibility results and amino acid sequences). We extract all reverse transcriptase sequences originated from subtype B strains, which gives us 970 reverse transcriptase sequences in total. We use drug susceptibility results measured using the PhenoSense method for eight nucleoside analogs, namely, Lamivudine (3TC), Abacavir (ABC), Zidovudine (AZT), Stavudine (d4T), Zalcitabine (ddC), Didanosine (ddI), Tenofovir (TDF) and Emtricitabine (FTC). Drug susceptibility results are given as fold change in susceptibility (i.e. standardized measure of HIV drug resistance), which is defined as

where IC50 of a resistant or wild-type control isolate gives its half maximal inhibitory concentration. We label reverse transcriptase sequences as ‘resistant’ or ‘susceptible’ using drug-specific cutoff values as done similarly in the earlier studies (Heider et al., 2013; Rhee et al., 2006). The cutoff is set to 1.5 for d4T, ddC, ddI and TDF, and to 3.0 for 3TC, ABC, AZT and FTC. Supplementary Figure S1 shows the drug resistance labels and the histogram of available IC50 ratios for 970 reverse transcriptase sequences.

We remove the sequences with no phenotype information (i.e. 48 reverse transcriptase sequences with no IC50 ratios), leading to a final dataset with 922 reverse transcriptase sequences. Table 1 summarizes the final dataset by listing the drug name, the corresponding analog, the number of reverse transcriptase sequences with measured IC50 ratio, the IC50 ratio cutoff and the ratio between resistant and susceptible classes for each drug.

Table 1.

Summary of HIV-1 dataset

| Drug name | Analog | Number of sequences | IC50 ratio cutoff | Class ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3TC | Cytidine | 910 | 3.0 | 2.487 |

| ABC | Guanosine | 743 | 3.0 | 1.444 |

| AZT | Thymidine | 905 | 3.0 | 1.257 |

| d4T | Thymidine | 908 | 1.5 | 1.147 |

| ddC | Pyrimidine | 472 | 1.5 | 1.713 |

| ddI | Guanosine | 908 | 1.5 | 1.253 |

| TDF | Adenosine | 545 | 1.5 | 0.622 |

| FTC | Cytidine | 165 | 3.0 | 2.587 |

Note: Class ratio denotes the ratio between numbers of resistant and susceptible sequences.

For each reverse transcriptase, genotype information is extracted from the amino acid sequence of positions 1–240. Amino acid differences from the subtype B consensus wild-type sequence are considered as mutations. There are 1474 unique mutations for 922 reverse transcriptase sequences in our dataset, which means each reverse transcriptase sequence can be represented as a 1474-dimensional binary vector.

2.2 Genomics of drug sensitivity in cancer

GDSC contains phenotype and genotype information about cancer (i.e. cancer cell lines with corresponding sensitivity results and genomic profiles). We use drug sensitivity results measured against 138 anticancer drugs, which are given in terms of half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) and area under the dose–response curve (AUC) values. We choose to perform our analysis on AUC values because IC50 values are not observed before the maximum screening concentration for a significant proportion of the drug and cell line pairs (i.e. most of the cell lines are resistant to a given drug within the range of experimental screening concentrations). Supplementary Figure S2 shows the AUC values and the histogram of available dose–response curves for 790 cancer cell lines.

GDSC contains genomic profiles in the forms of copy number variation, gene expression and mutation profiles. We choose to use only gene expression, as it is shown to be the most informative data source in earlier studies (Jang et al., 2014). Gene expression profile is extracted from hybridized RNA in HT-HGU133A Affymetrix whole genome array. There are 12 024 normalized gene expression intensities generated using the MAS5 algorithm (Hubbell et al., 2002), which means each cell line can be represented as a 12 024-dimensional real-valued vector.

We remove the cell lines with no phenotype or genotype information, leading to a final dataset with 664 cell lines and 138 drugs.

3 METHODS

We consider the problem of predicting susceptibility against a panel of drugs simultaneously for each data point, which is a viral reverse transcriptase for the HIV dataset and a cell line for the cancer dataset. Instead of training drug-specific models separately, we choose to solve this problem with a multitask learning formulation by considering each drug as a distinct task and learning a unified model for all tasks conjointly. We first discuss our proposed method for binary classification (i.e. classifying a data point as resistant or susceptible) in detail and then briefly mention how we extend our method to regression (i.e. predicting real-valued sensitivity measures such as IC50 or AUC).

3.1 Problem formulation

We assume that there are T related binary classification tasks defined on the domain . We are given an independent and identically distributed sample

. For each task, we are given a label vector

. For each task, we are given a label vector  , where gives the indices of data points with given class labels in task t. There is a kernel function to define similarities between the data points, i.e.

, where gives the indices of data points with given class labels in task t. There is a kernel function to define similarities between the data points, i.e.  , which is used to calculate the kernel matrix

, which is used to calculate the kernel matrix

.

.

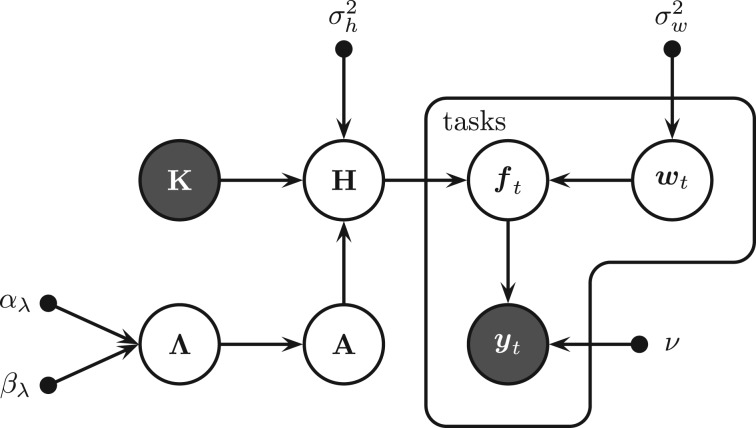

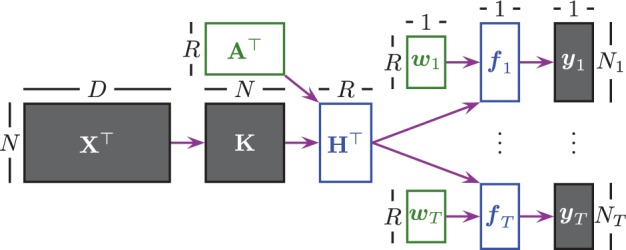

Figure 1 illustrates the method we propose to learn a conjoint model across the tasks; it is composed of two main parts: (i) projecting data points into a shared subspace using a ‘kernel-based dimensionality reduction’ model and (ii) performing ‘binary classification’ in this subspace using the task-specific classification parameters. We first briefly explain these two parts and introduce the notation used.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of KBMTL for binary classification. In the kernel-based dimensionality reduction part, we first calculate the kernel matrix K using the original data matrix X and then find the hidden representation matrix H by projecting the kernel matrix into a subspace using the projection matrix A. In the binary classification part, we first calculate the predicted outputs over the hidden representations using the task-specific classification parameters and then map these outputs into the class labels

We first perform feature extraction using the input kernel matrix and the projection matrix , where N is the number of data points and R is the subspace dimensionality. When we map the data points into a low dimensional latent subspace using the projection matrix A, we obtain their hidden representations in this shared subspace, i.e. . Using a kernel-based formulation has three main implications: (i) We can apply our method to tasks with high dimensional representations such as genomic information and small sample size (i.e. large p, small n). (ii) We can learn better subspaces using non-linear kernels such as the Gaussian kernel (i.e. kernel trick). (iii) We can use domain-specific kernels (e.g. graph and tree kernels for structured objects) to better capture the underlying biological processes (Schölkopf et al., 2004).

The task-specific classification parts calculate the predicted outputs in the shared subspace using the hidden representations and the task-specific parameters , where contains only the data points in . These predicted outputs are mapped to class labels by looking at their signs.

3.2 Kernelized Bayesian multitask learning

We formulate a probabilistic model, called KBMTL, for the method described earlier. We can derive an efficient inference algorithm using variational approximation because our method combines the kernel-based dimensionality reduction and task-specific classification parts with a fully conjugate probabilistic model.

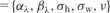

Figure 2 gives the graphical model of KBMTL with hyper-parameters, priors, latent variables and model parameters. As described earlier, the main idea can be summarized as (i) finding hidden representations for the data points by mapping them into a subspace with the help of kernel and projection matrices and (ii) performing binary classification in this shared subspace using the task-specific classification parameters.

Fig. 2.

Graphical model of KBMTL for binary classification. Small filled circles: hyper-parameters; large shaded circles: observed variables; other large circles: random variables

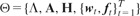

There are some additions to the notation described earlier: the N × R matrix of priors for the entries of the projection matrix A is denoted by Λ. For these priors,  are used as hyper-parameters. The standard deviations for the hidden representations and classification parameters are given as σh and σw, respectively. As short-hand notations, the hyper-parameters of the model are denoted by

are used as hyper-parameters. The standard deviations for the hidden representations and classification parameters are given as σh and σw, respectively. As short-hand notations, the hyper-parameters of the model are denoted by  , the priors, latent variables and model parameters by

, the priors, latent variables and model parameters by  . Dependence on ζ is omitted for clarity throughout the manuscript.

. Dependence on ζ is omitted for clarity throughout the manuscript.

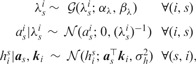

The distributional assumptions of the kernel-based dimensionality reduction part are defined as

|

where the superscript indexes the rows, and the subscript indexes the columns. represents the normal distribution with the mean vector μ and the covariance matrix Σ. denotes the gamma distribution with the shape parameter α and the scale parameter β.

The binary classification part has the following distributional assumptions:

|

where the predicted outputs , similar to the discriminant outputs in support vector machines, are introduced to make the inference procedures efficient (Albert and Chib, 1993). The non-negative margin parameter ν is introduced to resolve the scaling ambiguity and to place a low-density region between two classes, similar to the margin idea in support vector machines, which is generally used for semi-supervised learning (Lawrence and Jordan, 2005). represents the Kronecker delta function that returns 1 if its argument is true and 0 otherwise.

Note that the dimensionality reduction part considers all data points, whereas the binary classification part considers only the data points with given labels in each task, leading to the ability of handling missing values.

3.2.1 Inference using variational Bayes

To obtain an efficient inference mechanism, we formulate a deterministic variational approximation instead of using a Gibbs sampling approach, which is computationally expensive (Gelfand and Smith, 1990). The variational methods use a lower bound on the marginal likelihood using an ensemble of factored posteriors to find the joint parameter distribution (Beal, 2003). We can write the factorable ensemble approximation of the required posterior as

and define each factor in the ensemble just like its full conditional distribution:

|

where and denote the shape parameter, the scale parameter, the mean vector and the covariance matrix for their arguments, respectively. denotes the truncated normal distribution with the mean vector μ, the covariance matrix Σ and the truncation rule such that if is true and otherwise.

We can bound the marginal likelihood using Jensen’s inequality:

and optimize this bound by maximizing with respect to each factor separately until convergence. The approximate posterior distribution of a specific factor τ can be found as

For our proposed model, thanks to the conjugacy, the resulting approximate posterior distribution of each factor follows the same distribution as the corresponding factor. The technical details of our inference mechanism can be found in the Supplementary Material.

3.2.2 Prediction scenario

We can replace with its approximate posterior distribution and obtain the predictive distribution of the latent representation for a new data point as

The predictive distribution of the predicted output can also be found by replacing with its approximate posterior distribution :

and the predictive distribution of the class label can be formulated using the predicted output distribution:

and the predictive distribution of the class label can be formulated using the predicted output distribution:

where is the normalization coefficient calculated for the test data point, and is the standardized normal cumulative distribution function.

3.3 Baseline algorithms

To show the practical importance of multitask learning, we compare our method to two baseline algorithms: (i) Bayesian single-task learning and (ii) kernelized Bayesian single-task learning. The technical details for the baseline algorithms can be found in the Supplementary Material.

3.3.1 Bayesian single-task learning

Instead of learning a unified model for all tasks conjointly, we can train a separate model for each task. For this purpose, we use a Bayesian linear classification algorithm, which is known as ‘probit classifier’ (Albert and Chib, 1993). We call this algorithm ‘Bayesian probit classifier’ (BPROBIT).

3.3.2 Kernelized Bayesian single-task learning

Instead of training a linear model, we can also use a kernelized algorithm to obtain non-linear models. For this purpose, we use a kernelized Bayesian classification algorithm, which is known as ‘relevance vector machine’ (Bishop and Tipping, 2000; Tipping, 2001). We call this algorithm ‘Bayesian relevance vector machine’ (BRVM).

3.4 Extension to regression problems

Our method and two baseline algorithms are defined for the binary classification scenario but they can easily be extended to regression problems. The technical details for the regression variant of our method can be found in the Supplementary Material. We explain the regression variant of our method in detail, and the regression variants of baseline algorithms can also be derived similarly.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

To illustrate the effectiveness of our proposed KBMTL method, we report its results on two datasets and compare it with two baseline algorithms, namely, BPROBIT and BRVM. We have three main reasons for these particular choices: (i) Both BPROBIT and BRVM use same type of inference mechanism with our method. (ii) BPROBIT is from the family of linear and regularized algorithms, which are considered as the standard approach for drug susceptibility prediction. (iii) We can see the effect of multitask formulation by comparing our method to BRVM, which can also make use of kernel functions for drug-specific models.

4.1 Experimental setting and performance metrics

For each dataset, data points are split into five subsets of roughly equal size. Each subset is then used in turn as the test set, and training is performed on the remaining four subsets. This procedure is repeated 10 times (i.e. 10 replications of 5-fold cross-validation) to obtain robust results.

We use ‘area under the receiver operating characteristic curve’ (AUROC) to compare classification results. AUROC is used to summarize the receiver operating characteristic curve, which is a curve of true positives as a function of false positives while the threshold to predict labels changes. Larger AUROC values correspond to better performance.

We use ‘normalized root mean square error’ (NRMSE) to compare regression results. NRMSE of drug t can be calculated as

where and denote the measured and predicted output vectors, respectively. Smaller NRMSE values correspond to better performance.

4.2 Performance comparison on HIVDB

On HIVDB, we compare three algorithms, namely, BPROBIT, BRVM and KBMTL, in terms of their classification performances. For BPROBIT, the hyper-parameter values are selected as and ν = 1. For BRVM, the hyper-parameter values are selected as and ν = 1. For KBMTL, the hyper-parameter values are selected as and ν = 1. The shape and scale hyper-parameters of gamma distributed priors are set to non-informative values not to impose sparsity on the model parameters. The number of components in the hidden representation space is selected as R = 10. For all algorithms, we perform 200 iterations during variational inference.

To calculate similarity between reverse transcriptase sequences for BRVM and KBMTL, we use the Gaussian kernel defined as , where the kernel width s is chosen among and  using an internal 5-fold cross-validation scheme on the training set. We decide to make a selection from these particular values because the mean of pairwise Euclidean distances between data points, which is frequently used as the default value for s, is approximately

using an internal 5-fold cross-validation scheme on the training set. We decide to make a selection from these particular values because the mean of pairwise Euclidean distances between data points, which is frequently used as the default value for s, is approximately  .

.

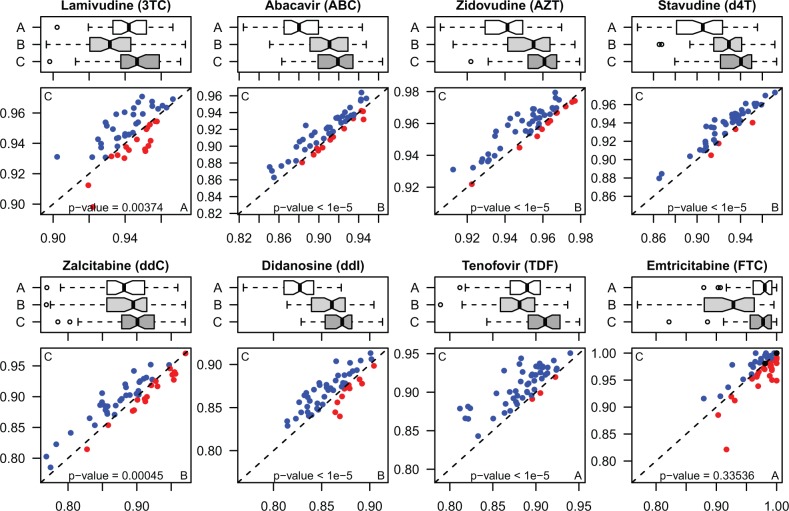

Table 2 gives the mean and standard deviation of AUROC values obtained by BPROBIT, BRVM and KBMTL for each drug over 50 replications as their performance measures. We see that KBMTL obtains the highest mean AUROC values for seven of eight HIV-1 drugs by improving the results from 0.5 (3TC) to 2.3% (TDF) compared with the second highest. For FTC, BPROBIT obtains the highest mean AUROC value, whereas KBMTL falls behind by 0.3%. We also report the average AUROC values over drugs in the last row of Table 2. We see that KBMTL outperforms BPROBIT and BRVM by 2.1 and 1.7%, respectively. Figure 3 compares the performance of BPROBIT, BRVM and KBMTL for each drug using box-and-whisker plots. It also compares KBMTL and the best baseline algorithm for each drug using scatterplots. We clearly see that KBMTL is superior to BPROBIT and BRVM on all drugs except FTC. The performance differences obtained by KBMTL over BPROBIT and BRVM on these seven drugs are statistically significant according to the paired t-test with P < 0.01. The increased performance of KBMTL cannot be explained by the non-linearity introduced owing to the Gaussian kernel alone because BRVM also uses the Gaussian kernel and is able to outperform BPROBIT by only 0.4%. The main reason of this increased performance is the joint modeling of drugs with multitask learning.

Table 2.

Mean and standard deviations of AUROC values for BPROBIT, BRVM and KBMTL on HIV-1 drug resistance dataset together with ranks in parentheses

| Drug | BPROBIT | BRVM | KBMTL |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3TC | 0.942 ± 0.013 (2) | 0.933 ± 0.018 (3) | 0.947 ± 0.014 (1) |

| ABC | 0.881 ± 0.027 (3) | 0.908 ± 0.026 (2) | 0.917 ± 0.024 (1) |

| AZT | 0.940 ± 0.015 (3) | 0.952 ± 0.015 (2) | 0.958 ± 0.013 (1) |

| d4T | 0.904 ± 0.026 (3) | 0.927 ± 0.021 (2) | 0.936 ± 0.020 (1) |

| ddC | 0.880 ± 0.038 (3) | 0.886 ± 0.047 (2) | 0.897 ± 0.039 (1) |

| ddI | 0.827 ± 0.025 (3) | 0.859 ± 0.023 (2) | 0.869 ± 0.021 (1) |

| TDF | 0.884 ± 0.030 (2) | 0.876 ± 0.031 (3) | 0.907 ± 0.025 (1) |

| FTC | 0.971 ± 0.030 (1) | 0.920 ± 0.053 (3) | 0.968 ± 0.034 (2) |

| Average | 0.904 ± 0.011 (3) | 0.908 ± 0.013 (2) | 0.925 ± 0.012 (1) |

Note: The best result for each row is marked in bold face if it is statistically significantly better than the others according to the paired t-test with P < 0.01.

Fig. 3.

Performance comparison between (A) BPROBIT, (B) BRVM and (C) KBMTL in terms of AUROC values on HIV-1 drug resistance dataset for each drug. The box-and-whisker plots compare the AUROC values of the algorithms over 50 replications. The scatterplots give the AUROC values of the best baseline algorithm and KBMTL for 50 replications on the x- and y-axes, respectively. For comparison, blue: KBMTL is better; red: KBMTL is worse

To illustrate the biological relevance of our method, we analyze the ability to identify drugs with similar mechanisms of action based on hierarchical clustering of drugs based on the task-specific classification parameters inferred by KBMTL. Supplementary Figure S3 compares the clustering results obtained using KBMTL parameters versus clustering based on similarity of IC50 ratios. We see that the analogs of Cytidine (3FC and FTC) are clustered together at the bottom level of the dendogram using both IC50 ratios and KBMTL parameters for correlation calculation. However, the other drugs with the same analog are not clustered together at the bottom level based on IC50 ratios. If we use the task-specific classification parameters found by KBMTL for correlation calculation, hierarchical clustering is able to find three clusters: (i) analogs of Cytidine (3TC and FTC), (ii) analogs of Guanosine (ABC and ddI) and (iii) analogs of Thymidine (AZT and d4T). These results show that KBMTL is able to reveal underlying biological similarities between drugs and to make use of this information to improve predictive performance.

4.3 Performance comparison on GDSC

On GDSC, we compare four algorithms, namely, BRVM with the linear kernel (BRVM[L]), BRVM with the Gaussian kernel (BRVM[G]), KBMTL with the linear kernel (KBMTL[L]) and KBMTL with the Gaussian kernel (KBMTL[G]), in terms of their regression performances. For BRVM, the hyper-parameter values are selected as and . For KBMTL, the hyper-parameter values are selected as and . The number of components in the hidden representation space is selected as R = 100. For all algorithms, we perform 200 iterations during variational inference.

The training set is normalized to have zero mean and unit standard deviation, and the test set is then normalized using the mean and the standard deviation of the original training set. To calculate similarity between cell lines for BRVM and KBMTL, we use (i) the linear kernel defined as , where we normalize the kernel matrix to unit maximum value (i.e. dividing the kernel matrix by its maximum value) to eliminate scaling issues and (ii) the Gaussian kernel whose width parameter s is chosen among and  using an internal 5-fold cross-validation scheme on the training set. We decide to make a selection from these particular values because the mean of pairwise Euclidean distances between data points is

using an internal 5-fold cross-validation scheme on the training set. We decide to make a selection from these particular values because the mean of pairwise Euclidean distances between data points is  .

.

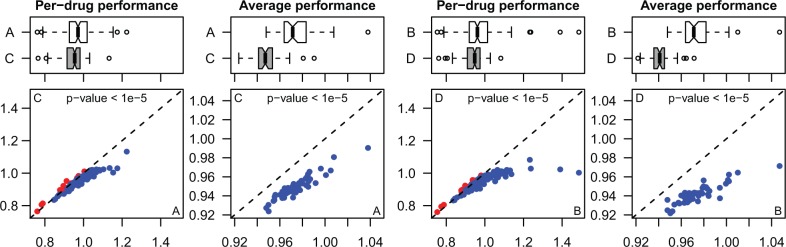

Figure 4 compares the performance of BRVM and KBMTL with the same kernel in terms of per-drug performance (i.e. 138 mean NRMSE values calculated over 50 replications) and average performance (i.e. 50 mean NRMSE values calculated over 138 drugs) using box-and-whisker and scatterplots. We see that KBMTL[L] obtains statistically significantly better results than BRVM[L] in terms of both per-drug and average performances according to the paired t-test with P < 0.01. This result is also valid when we compare KBMTL[G] and BRVM[G]. Table 3 gives the pairwise comparison results between the four algorithms over 138 per-drug performance values. For example, KBMTL[L] obtains better predictive performance than BRVM[L] on 126 of 138 drugs. On 102 of these 126 drugs, KBMTL[L] is statistically significantly better than BRVM[L] according to the paired t-test with P < 0.01. If we sort the algorithms in terms of their predictive performances, we find the following ordering: KBMTL[G] > KBMTL[L] > BRVM[G] > BRVM[L]. These results show that predicting drug sensitivities with a joint model obtains superior predictive performance than using drug-specific models irrespective of the kernel function used.

Fig. 4.

Performance comparison between (A) BRVM with the linear kernel, (B) BRVM with the Gaussian kernel, (C) KBMTL with the linear kernel and (D) KBMTL with the Gaussian kernel in terms of NRMSE values on cancer drug sensitivity dataset. The per-drug and average performance results compare the algorithms using 138 mean NRMSE values calculated over 50 replications and 50 mean NRMSE values calculated over 138 drugs, respectively. The box-and-whisker and scatterplots compare the NRMSE values of BRVM (on the x-axis of the scatterplots) and KBMTL (on the y-axis of the scatterplots) with the same kernel. For comparison, blue: KBMTL is better; red: KBMTL is worse

Table 3.

Pairwise comparison of four algorithms in terms of per-drug performances on cancer drug sensitivity dataset

| Algorithm | BRVM[L] | BRVM[G] | KBMTL[L] | KBMTL[G] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRVM[L] | 25/45 | 5/12 | 2/11 | |

| BRVM[G] | 70/93 | 26/43 | 5/17 | |

| KBMTL[L] | 102/126 | 64/95 | 4/25 | |

| KBMTL[G] | 114/127 | 98/121 | 84/113 |

Note: The numbers in each comparison give statistically significant wins according to the paired t-test with P < 0.01 and wins according to the direct comparison, respectively, for the method of the corresponding row.

5 CONCLUSION

In this study, we consider the problem of drug susceptibility prediction based on pharmacogenomic screens against a panel of drugs. In contrast to earlier studies, we choose to solve this problem with a multitask learning formulation by considering each drug as a distinct task and learning a unified model for all tasks conjointly. For this purpose, we propose a novel Bayesian multitask learning algorithm that combines kernel-based non-linear dimensionality reduction and binary classification to classify data points as resistant or susceptible. We formulate a deterministic variational approximation inference scheme, which is more efficient than using a Gibbs sampling approach in terms of computation time. We then extend our algorithm to regression to predict real-valued outputs such as half maximal inhibitory concentration and AUC.

The main novelty of our approach comes from the joint Bayesian formulation of projecting data points into a shared subspace and learning predictive models for all drugs in this subspace, which enables us to capture commonalities between subsets of drugs to improve predictive performance. The increased performance is due to elimination of off-target effects and drug-specific experimental noise that may be present in drug susceptibility values. Another novelty of our approach comes from the ability to handle missing drug susceptibility values owing to experimental conditions and quality control reasons, which increases the effective sample size, leading to more robust predictions especially for drugs with a large number of missing phenotype values.

To demonstrate the performance of our algorithm, called KBMTL, we perform cross-validation experiments on drug susceptibility datasets of two major human diseases, namely, HIV and cancer. For the HIV dataset, we classify viral reverse transcriptase sequences as resistant or susceptible against eight nucleoside analogs using mutation profiles extracted from sequence information of the viral genotype. Our multitask learning method obtains statistically significantly better results on seven of eight drugs compared with two baseline single-task learning methods that consider each drug separately. For the cancer dataset, we predict AUC within the range of experimental screening concentrations for each cell line against 138 anticancer drugs using gene expression profiles. Our method with the linear or Gaussian kernel obtains statistically significantly better results on 102 or 98 of 138 drugs, respectively, compared to a single-task learning method with the same kernel function. These results show that predicting drug susceptibility against a panel of drugs simultaneously within a multitask learning framework improves overall predictive performance over single-task learning approaches that learn drug-specific models.

We implement both single-task and multitask learning methods using efficient variational approximation schemes, where covariance calculations are the most time-consuming steps because of matrix inversions. BRVM has complexity per iteration, but we need to train a separate model for each drug, leading to overall complexity. KBMTL learns a unified model for all drugs conjointly and has complexity per iteration, which shows that our algorithm has comparable computational complexity with single-task learning methods up to moderate values of R.

We envision several possible extensions of our work in future pharmacogenomic applications. Based on an analysis over KBMTL model parameters, we are able to identify groups of compounds with similar mechanisms of action. As functional screens are being performed on increasingly large numbers of compounds or genetic perturbations, often with poorly characterized mechanisms or strong off-target effects, jointly modeling each compound in the context of the full screening collection should yield novel insights into compound mechanisms. Moreover, the ability to identify groups of related compounds with a shared robust molecular predictor should aid drug discovery efforts by improving the interpretability of large screens and providing multiple lead compounds effecting similar biological processes. From an algorithmic perspective, the kernelized Bayesian framework provides an extensible template for incorporating prior knowledge. For example, prior information may be incorporated to encourage similar predictors to be inferred for compounds known to target proteins in the same pathway. Importantly, extensions of more complex prior information are computationally tractable owing to the highly efficient inference performed by the variational Bayes algorithm. In summary, we believe that the method presented in this work contributes to the field of pharmacogenomic analysis by improving the robustness of drug susceptibility predictions by leveraging information shared across multiple compounds in a screen, and it provides an efficient Bayesian inference framework that may be applied and extended by the community in future applications.

Funding: The Integrative Cancer Biology Program (ICBP) of the National Cancer Institute (1U54CA149237). Cancer Target Discovery and Development (CTDD) Network of the National Cancer Institute (1U01CA176303).

Conflicts of interest: none declared.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- Albert JH, Chib S. Bayesian analysis of binary and polychotomous response data. J. Amer. Statist. Assoc. 1993;88:669–679. [Google Scholar]

- Barretina J, et al. The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia enables predictive modelling of anticancer drug sensitivity. Nature. 2012;483:603–607. doi: 10.1038/nature11003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beal MJ. Variational algorithms for approximate Bayesian inference. 2003 PhD Thesis, The Gatsby Computational Neuroscience Unit, University College London. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop CM, Tipping ME. Proceedings of the 16th Conference on Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence. Stanford, CA, USA: 2000. Variational relevance vector machines; pp. 46–53. [Google Scholar]

- Caruana R. Multitask learning. Mach. Learn. 1997;28:41–75. [Google Scholar]

- Druker BJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of a specific inhibitor of the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase in chronic myeloid leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;344:1031–1037. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104053441401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnett MJ, et al. Systematic identification of genomic markers of drug sensitivity in cancer cells. Nature. 2012;483:570–577. doi: 10.1038/nature11005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand AE, Smith AFM. Sampling-based approaches to calculating marginal densities. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1990;85:398–409. [Google Scholar]

- Heider D, et al. Multilabel classification for exploiting cross-resistance information in HIV-1 drug resistance prediction. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:1946–1952. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbell E, et al. Robust estimators for expression analysis. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:1585–1592. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.12.1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang IS, et al. Systematic assessment of analytical methods for drug sensitivity prediction from cancer cell line data. Pac. Symp. Biocomput. 2014;19:63–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence ND, Jordan MI. Semi-supervised learning via Gaussian processes. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2005;17:753–760. [Google Scholar]

- Menden MP, et al. Machine learning prediction of cancer cell sensitivity to drugs based on genomic and chemical properties. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61318. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neto EC, et al. The stream algorithm: computationally efficient ridge-regression via Bayesian model averaging, and applications to pharmacogenomic prediction of cancer cell line sensitivity. Pac. Symp. Biocomput. 2014;19:27–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papillon-Cavanagh S, et al. Comparison and validation of genomic predictors for anticancer drug sensitivity. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2013;20:597–602. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read J, et al. Classifier chains for multi-label classification. Mach. Learn. 2011;85:333–359. [Google Scholar]

- Rhee SY, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase and protease sequence database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:298–303. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee SY, et al. Genotypic predictors of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 drug resistance. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:17355–17360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607274103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schölkopf,B. and Smola,A.J. (2002) Learning with Kernels: Support Vector Machines, Regularization, Optimization, and Beyond. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Schölkopf,B. et al., eds (2004) Kernel Methods in Computational Biology. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Tipping ME. Sparse Bayesian learning and the relevance vector machine. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2001;1:211–244. [Google Scholar]

- Tsoumakas G, et al. Mining multi-label data. In: Maimon O, Rokach L, editors. Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery Handbook. New York, NY, USA: Springer; 2010. pp. 667–685. [Google Scholar]

- Wei G, et al. Chemical genomics identifies small-molecule MCL1 repressors and BCL-xL as a predictor of MCL1 dependency. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:547–562. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, et al. Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC): a resource for therapeutic biomarker discovery in cancer cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D955–D961. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.