Abstract

Background

Increasing evidence indicates that mu- and delta-opioid receptors are decisively involved in the retrieval of memories underlying conditioned effects of ethanol. The precise mechanism by which these receptors participate in such effects remains unclear. Given the important role of the proopiomelanocortin (POMc)-derived opioid peptide beta-endorphin, an endogenous mu- and delta-opioid receptor agonist, in some of the behavioral effects of ethanol, we hypothesized that beta-endorphin would also be involved in ethanol conditioning.

Methods

In the present study we treated female Swiss mice with estradiol valerate (EV), which induces a neurotoxic lesion of the beta-endorphin neurons of the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus (ArcN). These mice were compared to saline-treated controls to investigate the role of beta-endorphin in the acquisition, extinction and reinstatement of ethanol (0 or 2 g/kg; i.p.)-induced conditioned place preference (CPP).

Results

Immunohistochemical analyses confirmed a decreased number of POMc-containing neurons of the ArcN with EV treatment. EV did not affect the acquisition or reinstatement of ethanol-induced CPP, but facilitated its extinction. Behavioral sensitization to ethanol, seen during the conditioning days, was not present in EV-treated animals.

Conclusions

The present data suggest that ArcN beta-endorphins are involved in the retrieval of conditioned memories of ethanol, and are implicated in the processes that underlie extinction of ethanol-cue associations. Results also reveal a dissociated neurobiology supporting behavioral sensitization to ethanol and its conditioning properties, as a beta-endorphin deficit affected sensitization to ethanol, while leaving acquisition and reinstatement of ethanol-induced CPP unaffected.

Keywords: Conditioned Place Preference, Ethanol, Beta-endorphin, Extinction, Naltrexone

Introduction

Accumulating evidence implicates the endogenous opioid system in the retrieval of memories that underlie some conditioned effects of ethanol (Bienkowski et al., 1999; Bormann and Cunningham, 1997; Burattini et al., 2006; Cunningham et al., 1998; Williams and Shimmel, 2008). Pretreatment with the opioid receptor antagonist, naloxone, while not influencing the acquisition of ethanol-induced conditioned place preference (CPP) (Bormann and Cunningham, 1997; Kuzmin et al., 2003), reduced the expression and facilitated the extinction of these conditioned responses in mice (Bormann and Cunningham, 1997; Cunningham et al., 1998; Kuzmin et al., 2003). Similarly, naltrexone, another non-specific opioid receptor antagonist, blocked conditioned cue-induced reinstatement of previously extinguished responding for ethanol self-administration (Burattini et al., 2006; Ciccocioppo et al., 2003).

Apart from the role of the opioid system in ethanol conditioning, this system has been traditionally seen as a mediator of the reinforcing properties of ethanol (Gianoulakis, 2009; Herz, 1997; Méndez and Morales-Mulia, 2008). The mechanism by which opioid receptor activation mediates reinforcing effects is hypothesized to involve the proopiomelanocortin (POMc)-derived opioid peptide, beta-endorphin (Gianoulakis, 2001; Herz, 1997; Sanchis-Segura et al., 2005). Three lines of evidence support this hypothesis. First, ethanol increases gene expression, content and release of beta-endorphin in some rodent brain regions such as the nucleus accumbens (NAcb) (De Waele and Gianoulakis, 1993; Olive et al., 2001; Marinelli et al., 2003). Second, beta-endorphin binds with high affinity to mu- and delta-opioid receptors (Williams et al., 2001), and blockade of these receptors by non-specific or specific antagonists reduces several behavioral effects of ethanol (Heyser et al., 1999; Froehlich et al., 1998; Pastor and Aragon, 2006, 2008; Sharpe and Samson, 2001). Third, genetically correlated differences in sensitivity of the beta-endorphin system to ethanol have been found in animals selected for high versus low ethanol consumption (De Waele et al., 1992; Froehlich, 1995; Gianoulakis et al., 1992) and in individuals that differ in family history of alcoholism (Gianoulakis et al., 1996). It is still unclear, however, whether beta-endorphin is critically involved in the role of the opioid system in the conditioned effects of ethanol.

Beta-endorphin-synthesizing cell bodies are primarily located in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus (ArcN) (Chronwall, 1985) and project to several regions including the NAcb, the amygdala, and the ventral tegmental area (VTA) (Finley et al., 1981). Interestingly, previous studies using CPP procedures have implicated the VTA (Bechtholt and Cunningham, 2005), amygdala, and NAcb (Gremel and Cunningham, 2008) in the expression of ethanol CPP. Both, mu- and delta-opioid receptors are found in these structures, and antagonism of opioid receptors within the VTA decreased the expression of ethanol-induced CPP (Bechtholt and Cunningham, 2005).

A neurotoxic lesion selective to ArcN beta-endorphin cells can be produced with estradiol valerate (EV) treatment (Desjardins et al., 1993; Roth-Deri, Mayan and Yadid, 2006). A single EV injection given to female rodents causes a progressive lesion throughout the ArcN that is specific to these POMc neurons (Desjardins et al., 1993). This lesion is due to prolonged EV-induced supraphysiological levels of estradiol (Brawer et al., 1978; Schulster et al., 1984) that, eight weeks after EV treatment, results in a 60% decrease in the number of beta-endorphin inmunoreactive neurons in the ArcN, and in the content of beta-endorphin in the NAcb (Desjardins et al., 1993; Roth-Deri et al., 2006). However, other hypothalamic neurotransmitters/neuromodulators such as met-enkephalin, neuropeptide-Y, neurotensin, somatostatin, and tyrosine hydroxylase remain unchanged (Desjardins et al., 1993). Previous research showed that this treatment decreased some behavioral effects of ethanol in mice, such as acute ethanol-induced locomotor stimulation (Sanchis-Segura et al., 2000).

In the present study, we used EV-treated mice to assess the role of ArcN beta-endorphin in the acquisition, extinction and reinstatement of ethanol-induced CPP. Given that pharmacological studies have suggested that the opioid system would participate in the retrieval of the memories supporting conditioned effects of ethanol, but not in their initial consolidation (Bormann and Cunningham, 1997; Burattini et al., 2006; Cunningham et al., 1998; Williams and Shimmel, 2008), we hypothesized that ArcN beta-endorphin lesions would facilitate extinction without modulating the acquisition of the response. Additionally, we examined the effects of naltrexone treatment on the expression of ethanol-induced CPP, hypothesizing that as demonstrated before, it would prevent expression of ethanol CPP. This experiment with naltrexone was also designed to respond to the question of whether a beta-endorphin deficit would produce effects parallel to the antagonist of opioid receptors in the expression of ethanol CPP.

Materials and methods

Subjects

Five-week old female Swiss (IOPS Orl) albino mice (a total N of 137) were purchased from CERJ-Janvier (Barcelona, Spain). This strain of mice was chosen in accordance with previous data showing sensitivity of this strain to EV-induced modifications of the behavioral effects of ethanol (Sanchis-Segura et al., 2000). Only females were used in this study as EV-induced effects on ArcN depend on increased levels of estradiol that can only occur in females (Desjardins et al., 1993). Mice were housed four per cage and were maintained in a humidity-(50%) and temperature-controlled (22 ± 1° C) environment on a reversed 12-h light/dark cycle with lights on at 8 a.m. All experiments were performed during the light cycle of the mice. Animals were acclimated to the colony room for at least 2 weeks prior to experimentation. Food (Panlab S.L., Spain) and tap water were available ad libitum. All experimental procedures followed the European Community Council Directive (86/609/ECC) for the use of laboratory animal subjects.

Drugs and treatments

Ethanol (20% v/v in physiological saline; Panreac S.A., Spain) was used for intraperitoneal injections (i.p.) at doses of 1 g/kg (6.25 ml/kg) and 2 g/kg (12.5 ml/kg). These doses were based on previous literature showing ethanol CPP with Swiss mice (Font et al., 2006; Risinger et al., 1996). For conditioning sessions, a single dose of ethanol (2 g/kg) was used in view of the lack of a dose-dependent response in standard unbiased CPP procedures (Groblewski et al., 2008). Vehicle injections consisted of physiological saline administered at a volume of 12.5 ml/kg. Naltrexone (Sigma-Aldrich Química, Spain) dosage and treatment conditions (2 mg/kg; i.p.) were chosen following previous work showing reduced behavioral effects of ethanol in mice (Pastor and Aragon, 2006; Phillips et al., 1997). Naltrexone was administered at an injection volume of 10 ml/kg. EV (beta-Estradiol 17-valerate; Sigma-Aldrich) was diluted in sesame oil (Sigma-Aldrich) and administered according to methods used in previous literature (Desjardins et al., 1993; Roth-Deri et al., 2006; Sanchis-Segura et al., 2000). Animals were injected intramuscularly (i.m.) with 0.2 ml of a 0, (oil) or 100 mg/10 ml (EV) EV suspension, 8 weeks before experiment initiation (2 mg of EV per animal). All i.m. injections were given under anesthesia to avoid pain associated with the i.m. injections; the anesthesia cocktail used contained ketamine (30 mg/ml) and xylazine (3 mg/ml) and we injected 0.1 ml per 25 g of animal.

Inmunohistochemistry for POMc-positive neurons

Control and EV-treated animals naïve to experimentation, not previously used in CPP studies, (N = 12) received an overdose of sodium pentobarbital (150 mg/kg) and were perfused through the heart with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffer (PB; 0.1 M; ph 7.4). Animals were euthanized eight weeks after vehicle or EV administration. Brains were carefully removed, postfixed overnight (formaldehyde 4%) and transferred to a 20% glycerol solution. Coronal 40 μm sections were cut on a sliding microtome and kept in PB with sodium azide (0.01%) until further processing. Rabbit anti-proopiomelanocortin (POMc) precursor (27-52; porcine) serum was purchased from Phoenix Pharmaceutical, Inc (Belmont, CA, USA). The secondary antibody, biotinylated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G, was purchased from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA, USA). Free-floating sections were collected in PB. After being washed (3 times x 10 min in PB), the sections were incubated for 30 min in PB containing 6% H2O2 for inactivation of endogenous peroxidases. The sections were then washed and incubated for 30 min in 2% normal goat serum in Tris-triton-saline buffer (TTBS; 0.1 M, ph 7.4, 0.3% triton X-100). After washing, sections were incubated overnight at room temperature with primary antiserum (anti-POMc) at a concentration of 1:200. The following day, sections were washed and then incubated for 30 min with a biotinylated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G at a concentration of 1:400. Washed sections were then incubated for 30 min with an avidin/biotin amplification kit (1:400 ABC kit; Vector), washed again and reacted with distilled H2O containing 3,3’-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and H2O2 for 6 min. A final counterstaining with hematoxylin (30 sec) was undertaken. The sections were mounted on gelatin-coated slides, dehydrated in a graded series of alcohols, cleared in xylene- substitute and coverslipped with Permount. Sections were analyzed by light microscopy with a Nikon Eclipse E800 microscope controlled by stereology software (Stereo Investigator, Microbrightfield Europe, Germany). Cell counts were carried out blind to experimental conditions. Known landmarks of the ArcN were carefully outlined at low resolution (10x) and POMc-positive cells (dark brown-colored) were identified and quantified at a higher resolution (40x) by light thresholding.

Behavioral procedures

Acquisition, extinction and reinstatement of ethanol-induced CPP in EV-treated mice

Place conditioning and preference test methodology were adapted from previous work (Cunningham et al., 2003; 2006; Font et al., 2006). CPP was conducted in four black acrylic chambers (30 cm long x 15 wide x 20 cm high) contained in dimly-illuminated and sound-attenuated enclosures (double layered Plexiglas compartments elevated 5 cm over the floor). No divider was used in the place conditioning chambers so animals had access to the entire box during both conditioning and testing for preference. Tactile cues (interchangeable grid and hole floors) were used as the conditioned stimuli. The grid floor consisted of 2.3 mm stainless steel rods mounted 6.4 mm apart on acrylic rails. Perforated stainless steel sheet metal (16 gauge) containing 6.4 mm round holes on 9.5 mm staggered centers was used as the hole floor. This combination of floor textures was selected based on previous studies, as well as our own pilot studies, showing that drug-naïve control mice show no preference for either floor type (Cunningham et al., 2003). The CPP experiment (see table 1) consisted of six phases: habituation (1 session), conditioning (8 sessions), preference test (1 session), extinction pairings (4 sessions), post-extinction preference tests (3 sessions) and reinstatement (1 session). During habituation, all subjects received an i.p. injection of saline and were immediately placed inside the conditioning chamber on a neutral floor for 5 min. The purpose was to familiarize the animals with handling procedures and the general experimental environment. The conditioning phase started the next day and followed an unbiased Pavlovian conditioning procedure in which vehicle and EV-pretreated mice were randomly assigned to one of two conditions, Grid+ or Grid- (N = 44; n = 10-12 per condition per floor). Animals assigned to the Grid+ group always received ethanol paired with grid floor and saline with hole floor. Alternatively, Grid- animals received ethanol in association with hole floor and saline with grid floor. Ethanol administration (CS+ days) occurred on days 2, 4, 8 and 10. Saline injections (CS- days) were given on days 3, 5, 9 and 11. During the conditioning phase, subjects had access to the entire apparatus but only one floor type (grid or hole) was presented for a 5-min period. On CS+ sessions mice received an injection of ethanol (2 g/kg; i.p.) and were immediately placed in the conditioning apparatus in which a single floor type was present across the entire space. On alternate CS- days, animals were injected with saline and placed in the conditioning apparatus with the other floor type present. The preference test (test 1) took place 24 h after the last conditioning trial. For all preference tests, the floor was half grid and half hole, mice were placed in the center of the chamber, and no injections were administered. Preference test duration was 60 min, and floor type position (i.e., left-right side of chamber) was counterbalanced for each subgroup. The primary dependent variable for preference tests was the amount of time spent on the CS+ and CS- floors during the 60-min test session. Movement of the animal during the preference test was monitored by a video-tracking system (SMART Letica S.A., Spain) and translated by SMART software to mean (± SEM) seconds per minute in each compartment. Forty-eight h after the initial preference test, four consecutive extinction pairings were undertaken. These pairings consisted of two sessions per floor (CS+ and CS-) with saline. Twenty-four h after the last extinction pairing session, three consecutive (one per day) preference tests (tests 2-4) were conducted. Five days after the last post- extinction preference test, a reinstatement test was performed. Potential reinstatement of the extinguished ethanol CPP was studied by injecting 1 g/kg of ethanol (i.p.) immediately before placing the animal in the center of the chamber for the preference test. Animals were left undisturbed in their home cages during days 6-7, 13-14 and 22-25.

Table 1.

Design for CPP experiments with EV: acquisition, extinction and reinstatement.

| Habituation | Conditioning CS+ | Conditioning CS− | Test 1 | Extinction | Test 2-4 | Reinstatement | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | D1 | D2, 4, 8 and 10 | D3, 5, 9 and 11 | D12 | D15-18 | D19-21 | D26 |

| V, G+ | Saline (N) | Ethanol (G) | Saline (H) | - | Saline | - | Ethanol |

| V, G− | Saline (N) | Ethanol (H) | Saline (G) | - | Saline | - | Ethanol |

| EV, G+ | Saline (N) | Ethanol (G) | Saline (H) | - | Saline | - | Ethanol |

| EV, G- | Saline (N) | Ethanol (H) | Saline (G) | - | Saline | - | Ethanol |

Shown are all groups included in CPP experiments with vehicle (V) or estradiol valerate (EV)-pretreated animals. After a habituation session, in which all animals were exposed to the one-compartment apparatus on a neutral floor, V and EV-pretreated mice were assigned to one of the following two groups: Grid (G)+, or G−. CS+ sessions, in which animals received ethanol, were conducted on days (D) 2, 4, 8 and 10. Saline injections, on CS− sessions, were given on days 3, 5, 9 and 11. Animals were left undisturbed in their home cages during days 6-7, 13-14 and 22-25. Mice did not receive any treatment before preference tests (Test 1 and Tests 1-4), but did receive ethanol immediately before the reinstatement test. Ethanol was injected at a dose of 2 g/kg, except for the reinstatement test, where an ethanol dose of 1 g/kg was used. Five-min sessions were used for the habituation, conditioning and extinction phases, whereas the preference and the reinstatement tests were 60-min long.

Expression of ethanol-induced CPP in naltrexone-treated mice

In this experiment, mice naïve to any experimentation (total N = 48; 12 mice per condition per floor), underwent the phases of habituation and conditioning described above (these animals were not treated with EV). Twenty-four h after the last day of conditioning, animals were injected with saline or naltrexone (2 mg/kg) 30 min before the 60-min preference test. As described in the first experiment, during the CPP test, mice were placed in the center of the conditioning chamber and could choose to spend time in contact with either the grid or hole floor.

Locomotor activity measurement

Total horizontal distance traveled (in cm) during the eight, 5-min conditioning sessions of the CPP experiment was monitored by the video-tracking system (S.M.A.R.T. Letica S.A., Spain). Acute activation to ethanol was determined by comparing activity level during the first CS- trial to that during the first CS+ trial. Sensitization to ethanol was detected by comparing locomotor activity levels during CS+ (ethanol) pairing sessions 2, 3 and 4 to the level during the first session.

Plasma corticosterone determination

This experiment was conducted to determine whether EV had any effect on spontaneous and/or ethanol-induced HPA axis function. Previous interactions between HPA axis and opioid systems have been described; naltrexone increases baseline and ethanol-increased corticosterone levels (Pastor et al., 2004). Mice that were not part of any other study (n = 10 per group) were used for this experiment. Oil and EV-treated animals were injected with ethanol (0 or 2 g/kg; i.p.) and trunk blood samples were obtained 60 min after this administration. Sample collection was performed 8 weeks after vehicle or EV administration. According to our previous data with Swiss mice, a significant increase in corticosterone was seen 60 min after ethanol administration (Pastor et al., 2004). As previously described (Pastor et al., 2004), samples were collected in heparinized (15 units/ml of blood) Eppendorf tubes and centrifuged at 4000 r.p.m. for 10 minutes. The supernatant was removed and stored at −20° C until corticosterone determination. Plasma corticosterone levels were measured using a commercially available enzymatic immunoassay (Rodents Corticosterone Enzyme Immunoassay System, OCTEIA Corticosterone, Immunodiagnostic Systems LTD, Boldon, England, UK). Blood corticosterone concentration (ng/ml) was determined using a non-linear (logarithmic) adjustment from the standard curve.

Data analysis

The primary dependent variable for the CPP experiments was the amount of time spent on the grid floor during each preference test converted to mean seconds per minute. To create this dependent variable, the number of seconds spent on the grid floor was divided by total duration of the test in minutes (60 min). Preference test data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA (EV dose x conditioning group). Significant preference would be indicated by grid (G)+ animals spending more time on the grid floor, compared to G- animals (mice that received ethanol on the hole floor during conditioning). The three consecutive post-extinction tests were analyzed by three way ANOVA with repeated measures (EV dose x conditioning group x test day). Behavioral stimulation and sensitization was analyzed by a three way ANOVA with repeated measures (EV dose x conditioning group x CPP pairing session). Plasma corticosterone levels (ng/ml) were analyzed by two-way ANOVA (EV dose x ethanol dose) and the number of POMc ArcN beta-endorphin cells was compared with an unpaired Student's t test for independent samples. When significant interactions in ANOVA analyses were obtained, Newman-Keuls post-hoc tests were used to determine specific differences between groups. Simple main effects were studied when appropriate. All statistical analyses were conduced with the Statistica 6.1 software package (StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA).

Results

Inmunohistochemistry of POMc-positive neurons of the ArcN in EV-treated animals

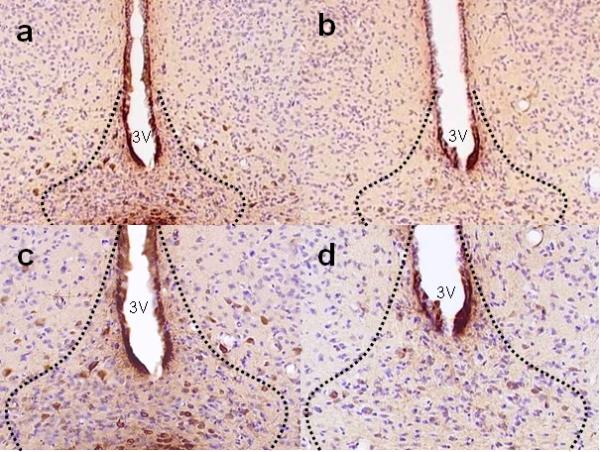

EV treatment produced a significant decrease in the number of ArcN neurons positive for POMc and thus, beta-endorphin synthesizing (see representative image in Fig. 1). Counts of POMc-positive neurons within ArcN boundaries were 39.5 ± 5.7 and 16 ± 4.3 for the control and EV treated groups, respectively. An independent Student's t test confirmed a significant difference between the two groups [t10 = 7.9; p < 0.01].

Figure 1.

Representative image of inmunocytochemically labeled proopiomelanocortin (POMc) neurons in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus (ArcN; which boundaries are delimited) and peri-ArcN region of vehicle (a,c) and estradiol valerate (EV)-treated (b,d) mice. Images are 10x (a,b) or 20x (c,d). Vehicle and EV groups (n = 6 per group) are animals treated with 0.2 ml of oil, or 2 mg of EV in 0.2 ml of oil (i.m.) per animal respectively. Cell counts revealed a 60% (approx.) decrease in the number of POMc-positve cells in EV-treated animals. 3V; third ventricle. Sections are Bregma -1.46 to -1.70 mm (approx.) according to Paxinos and Franklin (2003).

Acquisition, extinction and reinstatement of ethanol-induced CPP in EV-treated mice

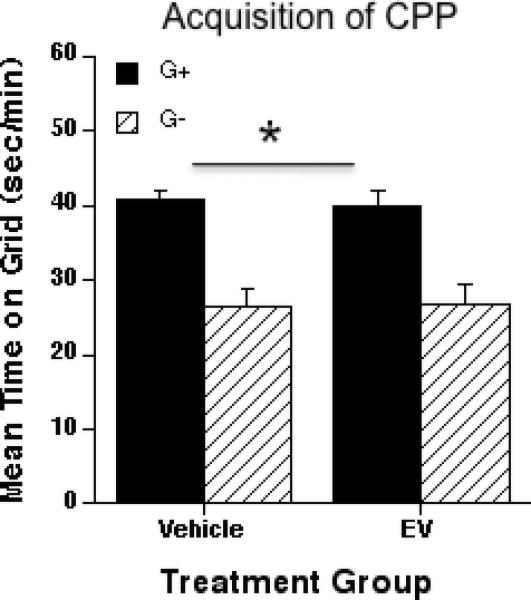

Mice for which ethanol (2 g/kg) was paired with the grid floor (G+ group), spent significantly more time in contact with the grid floor during the first preference test than did mice that were conditioned with ethanol on the hole floor (G- group) (Fig. 2). Supporting this conclusion, a two way ANOVA (EV dose x conditioning subgroup) revealed an effect of conditioning group [F1, 41 = 39.09; p < 0.01]. However, no effect of treatment (vehicle vs. EV), nor an interaction between EV treatment and conditioning subgroup, was found. Locomotor scores for the 60 min choice test were not different between the two groups (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Effect of estradiol valerate (EV) treatment on the acquisition of ethanol-induced CPP. Mean ± SEM seconds per minute spent on grid during a floor choice testing of 60 minutes. Grid+ and Grid- conditioning subgroups: N values: Vehicle, n = 12, and EV, n = 10. Grid+; ethanol paired to grid floor, saline paired to hole floor. Grid-; ethanol paired to hole floor, saline paired to grid floor. Vehicle and EV groups refer to animals treated with a single i.m. injection of 0.2 ml of sesame oil, or 2 mg of EV in 0.2 ml of sesame oil per animal respectively (injection administered 8 weeks before initiation of ethanol (2 g/kg)-induced CPP). All animals were treated on alternate days with 2 g/kg of ethanol i.p. (CS+ floor) or saline (CS- floor). Preference for the ethanol-paired floor was obtained in both, vehicle- and EV-treated groups, as a main effect of conditioning group (* p < 0.01) was obtained regardless of previous treatment.

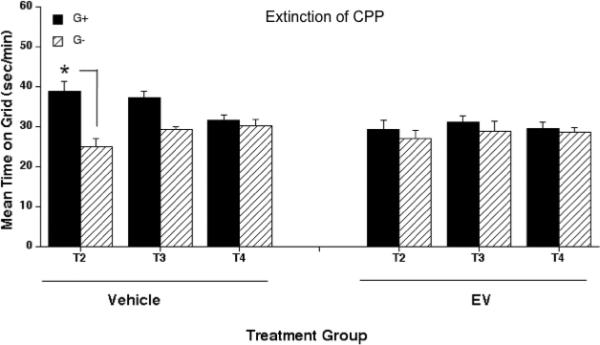

EV treatment did have an effect on rate of extinction. After four extinction sessions, control, but not EV animals, continued to show a preference for the ethanol paired floor (Fig. 3). However, when tested for preference on two additional days, preference for the ethanol-paired floor was absent in both control and EV-treated groups. Three way ANOVA with repeated measures (preference tests 2, 3 and 4) identified a significant three-way interaction of EV dose, conditioning group, and test day [F2,82 = 3.38; p < 0.05]. Two-way ANOVA within the EV group identified no significant main or interaction effects. However, within the control saline-treated group, there was a significant interaction of conditioning group and test day (F2,44 = 7.9; p < 0.01). Simple effect analyses indicated a difference in time spent on the grid floor between the conditioning groups only on test day 2 as shown (p < 0.01) in Fig. 3. This indicates that preference for the ethanol-paired floor waned across the three sessions in control animals and was absent during all three tests in the EV-treated mice. As mentioned before for choice test 1, locomotor scores (data not shown) for tests 2-4 were not different between the EV and vehicle groups.

Figure 3.

Effect of estradiol valerate (EV) treatment on the extinction of ethanol-induced CPP. Mean ± SEM seconds per minute spent on grid during a floor choice testing of 60 minutes (same animals as those shown in Fig. 2). After exhibiting ethanol-induced CPP, saline injections were paired with both, the CS+ and CS- floors (four sessions; two per floor). The day after the last extinction session, three consecutive (one per day) preference tests (tests 2, 3 and 4) were undertaken. Vehicle (V) and EV refer to animals treated with 0.2 ml of vehicle, or 2 mg of EV in 0.2 ml of vehicle (i.m.) per animal respectively. Preference for the ethanol-paired floor was only seen in control animals (*p < 0.01) on test 2. G+; Grid+, G-; Grid-.

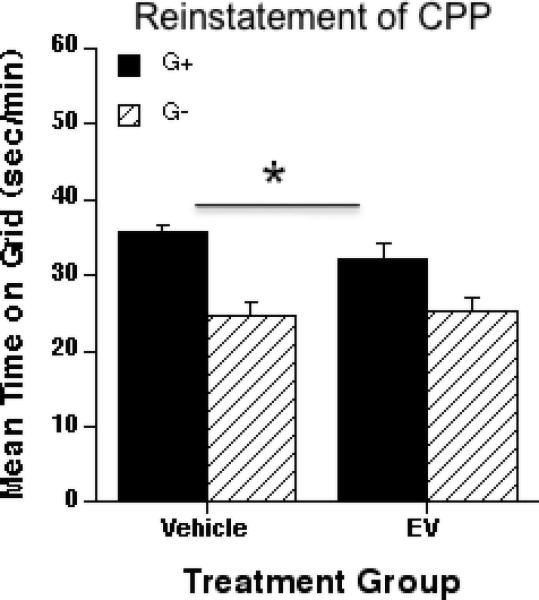

Figure 4 shows results for the reinstatement test after extinction of ethanol-induced CPP. A 1 g/kg ethanol injection was able to reinstate preference in control and EV-treated animals. A two-way ANOVA (EV treatment x conditioning subgroup) showed a main effect of conditioning group [F1, 41 = 28.00; p < 0.01], but no effect of treatment (vehicle vs. EV) or interaction effect. Thus, EV treatment did not prevent the ethanol-induced reinstatement of ethanol CPP. Locomotor activity after EtOH priming (data not shown) did not differ between the two groups.

Figure 4.

Effect of a priming injection of ethanol (1 g/kg) on the reinstatement of ethanol-induced CPP in control and estradiol valerate (EV)-treated mice. Mean ± SEM seconds per minute spent on grid during a floor choice testing of 60 minutes. Vehicle and EV-treated animals (same animals shown in Fig. 2 and 3) showed a previously extinguished ethanol induced CPP. Five days after the last preference test (test 4), all animals received an i.p. injection of 1 g/kg ethanol immediately before being tested for preference. Preference for the ethanol-paired floor was obtained in both, vehicle and EV-treated groups (*a significant main effect of conditioning subgroup was found, but no effect of treatment with EV, p < 0.01). G+; Grid+, G-; Grid-.

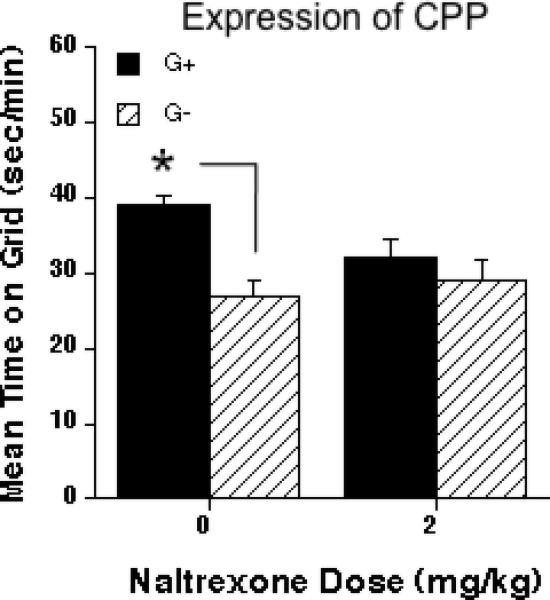

Expression of ethanol-induced CPP in naltrexone-treated mice

Consistent with the previous experiment, mice showed CPP after four 2 g/kg ethanol conditioning trials. However, animals treated with 2 mg/kg naltrexone, 30 min before the expression test, did not show significant CPP (Fig. 5). These conclusions were confirmed by a two-way ANOVA (naltrexone treatment x conditioning subgroup) that revealed a significant Follow-up simple effect analyses indicated significant CPP in the saline-treated (p < 0.01), but not naltrexone-treated mice. Locomotor activity during the conditioning sessions or the test was not different between groups; that is, naltrexone did not reduce locomotor activity (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Effect of naltrexone (0 or 2 mg/kg; i.p.) on the expression of ethanol-induced CPP. Mean ± SEM seconds per minute spent on grid during a floor choice testing of 60 minutes. Grid+ (G+) and Grid- (G-) conditioning subgroups, n = 12 per group. Grid+; ethanol paired to grid floor, saline paired to hole floor. Grid-; ethanol paired to hole floor, saline paired to grid floor. On the test day, naltrexone was injected 30 min prior to the choice test (*p < 0.01, difference between saline-treated G+ and Grid- groups.

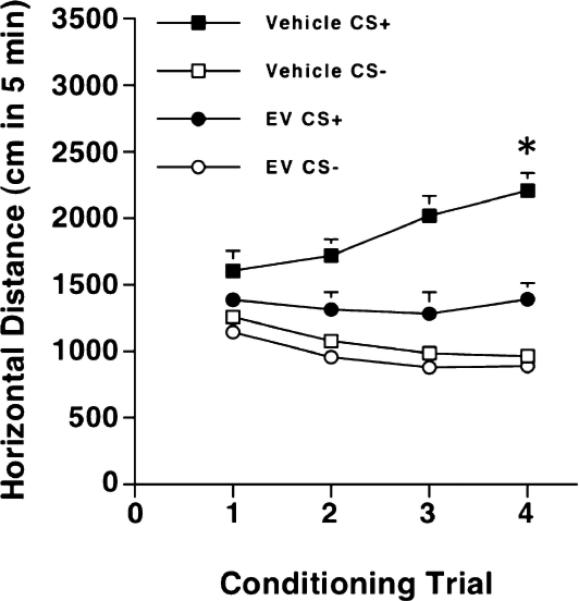

Consequences of EV treatment on the acute stimulant and locomotor sensitizing effects of ethanol

The analysis of locomotor activity data from the EV pretreatment study (both CS+ and CS- days) revealed an increased response to ethanol across the four CS+ pairing sessions in control but not in EV-treated animals (Fig. 6). A Three-way ANOVA with repeated measures identified a significant effect of conditioning group (indicating an effect of ethanol; F1, 86 = 83.3; p < 0.01) and an interaction of EV treatment x conditioning group x conditioning day [F3, 258 = 2.8; p < 0.05]. Simple effect analyses for the acute response to ethanol indicated a modest but significant (p = 0.048) effect of ethanol that was not significantly reduced by EV. Analyses also indicated significant differences across sessions in control, but not EV mice. Post hoc Newman-Keuls analyses indicated that ethanol-induced locomotor activity was greater in the fourth compared to the first CS+ conditioning session (p < 0.05). Analysis of the CS- days indicated a decreasing pattern of locomotor activity across sessions (p < 0.05), but no effect of EV treatment on locomotor behavior after saline injections.

Figure 6.

Effect of estradiol valerate (EV) on behavioral sensitization to ethanol. Group means (± SEM) of locomotor activity performed during the CS+ and CS- pairing sessions (5 min) are presented (n = 20-24 per group, same animals shown in Figs. 2-4). Following the CPP procedure, animals received four i.p. saline/ethanol (2 g/kg) injections on alternate days, with a 2 day-break separating the first and second blocks of four pairing sessions. Vehicle and EV groups refer to animals treated with sesame oil or with 2 mg of EV in 0.2 ml of oil (i.m.) per animal respectively. CS+ data for vehicle, but not EV-treated mice showed a sensitized response to ethanol (*p < 0.05, comparing locomotor scores of the fourth session with ethanol in the control group to those of the first session).

Effects of EV on ethanol-induced changes in plasma corticosterone levels

Basal and ethanol-induced rises in plasma corticosterone levels were not affected by prior EV treatment. Control animals showed basal levels of 44.4 ± 6 ng/ml (n = 9) of corticosterone, which increased to 87.6 ± 5.4 ng/ml when measured 60 min after ethanol administration (n = 9). Corticosterone levels for the EV group were 39.7 ± 6.7 ng/ml when treated with saline (n = 6) and 71.3 ± 4.9 ng/ml after ethanol (n = 9). A two-way ANOVA showed an effect of ethanol dose [F1,29 = 29.9; p < 0.01], but no effect of EV dose, or a significant interaction between ethanol dose and EV dose.

Discussion

The present experiments demonstrated that EV-treated female mice, lacking approximately 60% of their ArcN beta-endorphin cell population, showed a facilitated extinction of ethanol-induced CPP, although this cell loss did not prevent acquisition or reinstatement of ethanol-induced CPP. Pharmacological opioid antagonism with naltrexone, given before the memory retrieval, or expression test, prevented the expression of ethanol CPP. Although it did not block the acquisition of ethanol-induced CPP, EV treatment prevented the development of behavioral sensitization to ethanol. Overall, the present data complement contemporary theories proposing a role for the opioid system in the conditioned effects of ethanol and highlight significant dissociations between the neurobiology that underlies ethanol-induced CPP and locomotor sensitization to ethanol.

Facilitation of memory consolidation (i.e., of learning about the effect of a drug and its association with contextual stimuli) has been considered to be an attribute of reinforcers (Everitt and Robbins, 2005; White and Milner, 1992). Interestingly, CPP can be used to study conditioned memories suggested to indicate positive affective properties of reinforcers, such as drugs of abuse (Bardo and Bevins, 2000; Font et al., 2006). Consistent with previous literature (e.g. Cunningham et al., 1998, Font et al., 2006), we found that mice acquired significant ethanol-induced CPP. EV pre-treatment, which resulted in an approximately 60% loss of POMc-positive ArcN neurons, however, did not prevent this effect of ethanol. These results indicate that ethanol-induced place preference can be acquired despite a beta-endorphin deficit. Also, several studies have demonstrated that nonspecific opioid receptor antagonists (which would block the actions of endorphin, but also enkephalin and endomorphin) failed to prevent the acquisition of ethanol-induced CPP (Bormann and Cunningham, 1997; Kuzmin et al., 2003), and ethanol-induced CPP was unaffected in mu-opioid receptor knockout mice (Becker et al., 2002; Hall et al., 2001). Acquisition of ethanol-conditioned memories underlying CPP, therefore, does not appear to require participation of the opioid system. Thus far, we have been discussing the positively reinforcing effects of ethanol in the CPP procedure. However, it is also possible that conditioned negative reinforcement effects occurring 24 h after EtOH exposure (during the saline conditioning trials) could play a role in facilitating ethanol CPP. Higher doses of ethanol (around 4 g/kg; i.p.) are generally required to find measurable ethanol-induced withdrawal symptoms (Strong et al., 2009). However, subtle anxiety-like symptoms induced by repeated ethanol could produce aversion to the CS-, promoting greater preference for the CS+. In any case, those processes underlying acquisition of ethanol CPP do not seem to critically involve endorphin mechanisms.

There may, however, be a role for ArcN beta-endorphin neurons in mediating extinction of ethanol-induced CPP. After four forced extinction sessions, memory was assessed by measuring retrieval in animals presented with the CS+ (an ethanol-conditioned tactile floor stimulus) in the absence of the unconditioned stimulus (US), ethanol. Under these conditions, control mice were more resistant to extinction of ethanol-induced CPP than were EV-treated mice. They required at least one additional test (see Fig. 2), which also served as an extinction session, to extinguish their preference for the ethanol-paired floor. EV-treated mice showed extinction of ethanol-induced CPP in the first preference test after the forced extinction sessions. This result is consistent with previous literature that showed a facilitated extinction of ethanol-induced CPP with the opioid receptor antagonist, naloxone (Bormann and Cunningham, 1997; Cunningham et al., 1998). Cunningham and colleagues (1998) proposed that, at least in the case of ethanol, the recovery of drug memories is mediated by the endogenous opioid system. Following this rationale, the current data suggest that the relevant opioid system might be the ArcN endorphin system. Beta-endorphins have been known to enhance memory retrieval at low to moderate doses (Barros et al., 2003; Izquierdo et al., 2002). Perhaps, in the current case, the ability to retrieve ethanol-conditioned memories was at least partially impaired in animals with a beta-endorphin deficit. EV-treated animals were able to show CPP on the first choice test. Therefore, initial memory retrieval was possible in the presence of reduced beta-endorphin signaling, but resistance to extinction upon further memory retrievals was impaired. It has been proposed that a failure to release beta-endorphins might decrease the persistence of previous learning and could also produce apparent good learning of only short duration, which might lead to facilitated extinction (Rose and Orlowski, 1983). The ArcN beta-endorphin lesion may have resulted in labile excitatory associations that are more susceptible to disruption, thereby facilitating extinction.

That animals expressed CPP, despite a beta-endorphin deficit, contrasts with the disrupted expression of CPP seen in naltrexone-treated mice. This result is consistent with previous literature showing a similar effect in DBA/2J and NMRI mice treated with naloxone (Cunningham et al., 1998; Kuzmin et al., 2003). This effect has also been studied using a neuropharmacological approach; intra-VTA opioid receptor antagonism decreased the expression of ethanol-induced CPP (Bechtholt and Cunningham, 2005). Mu- and/or delta-opioid receptors are expressed in regions innervated by ArcN beta-endorphin neurons, such as the VTA, NAcb and amygdala. All of these regions have been proposed to be involved in extinction and retrieval of emotional memories (Dayas et al., 2007; Myers and Davis, 2002; Bahar et al., 2003). In addition to a reduction of endorphin-positive cells in the ArcN, EV lesions have been found to produce decreases in the content of beta-endorphin in the NAcb (Desjardins et al., 1993; Roth-Deri et al., 2006). One might then predict that under normal circumstances, conditioning could enhance ArcN beta-endorphin-induced activation of opioid receptors in the VTA, and potentially other brain regions. This represents a putative mechanism explaining the blocking effect of opioid antagonists on the expression of ethanol CPP. However, although it is possible that the 60% reduction in ArcN neurons that we obtained with EV was not enough to impact CPP expression, it is also likely that other endogenous opioid agonists of mu and/or delta receptors are involved in the processes underlying the expression of ethanol-induced CPP. Pilot data with naltrexone (data not shown) indicated that doses lower than 2 mg/kg (0.5 and 1 mg/kg) were not able to disrupt the expression of ethanol CPP. Given that low doses of naloxone and naltrexone (e.g. 1 mg/kg and less) are suggested to be specific for the mu opioid receptor, whereas higher doses may additionally recruit delta opioid receptors (Mhatre and Holloway, 2003; Takemori and Portoghese, 1984), our data support the hypothesis that different components of the opioid system, and not only beta-endorphin and mu-opioid receptors, might be involved in the expression of ethanol CPP.

In studies examining the reactivation of extinguished drug-conditioned memories, after the extinction of the CS-US association, the memory can again be retrieved by non-reinforced exposure to the CS (e.g., floor texture). In addition, the memory trace can be recovered by presentation of the US (e.g., priming ethanol injection) in association with conditioned cues. We found that animals given a priming injection of 1 g/kg ethanol exhibited state-dependent reinstatement of ethanol-induced CPP regardless of prior EV treatment. Thus, although EV-treated animals were not able to retrieve memories underlying CPP after extinction, an ethanol treatment given in the presence of the CS+, facilitated recuperation of the memory trace. The priming injection reinstatement effect cannot be explained by the stressful effects of the injection itself, because a pilot study (data not shown) indicated that a saline i.p. injection did not reinstate ethanol CPP under these procedural circumstances. However, our data showing no effect of EV treatment on priming-induced reinstatement of ethanol-induced CPP are inconsistent with data showing an effect of naloxone treatment (Kuzmin et al., 2003). The discrepancies in results might be explained by differences in experimental procedures; Kuzmin et al. (2003) used a biased CPP procedure, whereas we used an unbiased procedure. Different CPP apparatus, cues, test and trial duration, and mouse strain could also have contributed. Also, as mentioned, other components of the opioid system that are not affected by EV treatment may contribute.

We found that endorphin-deficient mice, unlike control mice, did not sensitize to the motor-stimulating effects of ethanol. This suggests that key neuroadaptations responsible for psychomotor sensitization were absent in beta-endorphin deficient animals that were repeatedly exposed to ethanol. This conclusion is supported by data showing absent ethanol-induced sensitization in mice with genetically-derived decreases in beta-endorphin (Allen and Grisel, 2005). In addition, an indiscriminate lesion of this structure blocked the development of behavioral sensitization to ethanol (Miquel et al., 2003), and antagonist studies have suggested the involvement of opioid receptors (Camarini et al., 2000; Pastor and Aragon, 2006), particularly mu-, but not delta-, opioid receptors (Pastor and Aragon, 2006). The present results suggest that the mechanism by which mu-opioid receptors participate in sensitization to ethanol may be mediated by ArcN beta-endorphin.

The neural changes underlying behavioral sensitization to abused drugs have been proposed to promote states of uncontrolled drug craving and seeking (Robinson and Berridge, 1993; Stewart and Badiani, 1993). Chronic ethanol sensitizes VTA DAergic neurons (Brodie, 2002) and enhances the responsiveness of NAcb DA terminals to depolarization (Nestby et al., 1997). Increases in DA D2 receptor binding have been found in mice sensitized to ethanol (Souza-Formigoni et al., 1999). Moreover, it is known that the DAceptive regions, such as the NAcb and the prefrontal cortex, are key contributors to drug-induced behavioral sensitization (Pierce and Kalivas, 1997; Vanderschuren and Kalivas, 2000). ArcN beta-endorphin neurons project to the VTA and the NAcb (Chronwall, 1985) and may modulate the release of DA in the NAcb (Spanagel et al., 1992) via activation of opioid receptors on VTA GABAergic interneurons (Leone et al., 1991; Longoni et al., 1991; Spanagel et al., 1992). It is reasonable to suggest that this DAergic link is a mechanism underlying behavioral sensitization to ethanol. However, antagonism of DA receptors with haloperidol or the deletion of DA D2 receptors did not prevent ethanol-induced sensitization (Broadbent et al., 1995; Palmer et al., 2003). Also, behavioral sensitization to ethanol can be found in the absence of a sensitized NAcb DA response in mice (Zapata et al., 2006). Thus, further research is needed to address whether opioid receptors play a DA-independent role in ethanol-induced sensitization, as previously suggested (Pastor and Aragon, 2006).

Animals treated with EV and not exposed to ethanol did not show any signs of toxicity and, in accordance with this, it was previously reported that there was no effect of EV on body weight or motor function (Sanchis-Segura et al., 2000). Previous work also demonstrated that caffeineor propanol-induced locomotor stimulation was not affected by EV (Sanchis-Segura et al., 2000). In our study, 2 of the 22 animals originally treated with EV died after the last CPP pairing session with ethanol; none of the control group mice died. Whether this was due to toxic effects of EV in combination with ethanol is unknown. However, body weight of control vs. EV-treated mice across the 8 conditioning trials was comparable. We assessed whether EV was altering the effects of ethanol on the HPA axis/stress response by measuring spontaneous and ethanol-enhanced plasma corticosterone levels, and, as demonstrated in rats (Roth-Deri et al., 2006), found no effect. These data suggest that the effects of EV found on ethanol-induced behaviors and putative toxicity were not produced via actions of EV on the HPA axis. Additionally, it is important to point out that beta-endorphin is also synthesized by the pituitary (van Den Burg et al., 2001). Since pituitary opioid mechanisms can influence basal and ethanol-induced corticosterone levels (Angelogianni and Gianoulakis, 1989; Pastor et al., 2004), we understand that unaltered levels of corticosterone after EV treatment might indicate normal functioning of this system.

In conclusion, the results of the present experiments suggest that a ArcN beta-endorphin deficit facilitates the extinction of an ethanol-induced CPP and prevents neuroplastic changes responsible for motor sensitization to ethanol. Separate neural mechanisms appear to mediate the acquisition and expression of memories underlying ethanol CPP, the later involving participation of mu and/or delta opioid receptors. Those receptors, via signaling of ArcN beta-endorphin, seem to be also involved in processes supporting memory retrieval and extinction of drug-associated memories.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from CICYT (SAF2005-07873) and from Red de Trastornos Adictivos, Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo (03I044.01/4) Spain. TJP supported by a grant from the Department of Veterans Affairs and by NIAAA grant P60 AA010760. Authors acknowledge gratefully the comments provided by Dr. C. Sanchis-Segura and Dr. C. L. Cunningham and the technical assistance provided by Alicia Dosda and Gemma Caballer.

References

- Allen SA, Grisel JE. Absence of EtOH-induced sensitization in b-endorphin deficient mice. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29:P824. [Google Scholar]

- Angelogianni P, Gianoulakis C. Prenatal exposure to ethanol alters the ontogeny of the beta-endorphin response to stress. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1989;13:564–571. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1989.tb00379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahar A, Samuel A, Hazvi S, Dudai Y. The amygdalar circuit that acquires taste aversion memory differs from the circuit that extinguishes it. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;17:1527–1530. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardo MT, Bevins RA. Conditioned place preference: what does it add to our preclinical understanding of drug reward? Psychopharmacology. 2000;153:31–43. doi: 10.1007/s002130000569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros DM, Izquierdo LA, Medina JH, Izquierdo I. Pharmacological findings contribute to the understanding of the main physiological mechanisms of memory retrieval. Current Drug Targets CNS and Neurological Disorders. 2003;2:81–94. doi: 10.2174/1568007033482931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechtholt AJ, Cunningham CL. Ethanol-induced conditioned place preference is expressed through a ventral tegmental area dependent mechanism. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2005;119:213–223. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.119.1.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker A, Grecksch G, Kraus J, Loh HH, Schroeder H, Hollt V. Rewarding effects of ethanol and cocaine in mu opioid receptor-deficient mice. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 2002;365:296–302. doi: 10.1007/s00210-002-0533-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienkowski P, Kostowski W, Koros E. Ethanol-reinforced behaviour in the rat: effects of naltrexone. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;374:321–327. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00245-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bormann NM, Cunningham CL. The effects of naloxone on expression and acquisition of ethanol place conditioning in rats. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1997;58:975–982. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(97)00304-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brawer JR, Naftolin F, Martin J, Sonnenschein C. Effects of a single injection of estradiol valerate on the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus and on reproductive function in the female rat. Endocrinology. 1978;103:501–512. doi: 10.1210/endo-103-2-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadbent J, Grahame NJ, Cunningham CL. Haloperidol prevents ethanol-stimulated locomotor activity but fails to block sensitization. Psychopharmacology. 1995;120:475–482. doi: 10.1007/BF02245821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodie MS. Increased ethanol excitation of dopaminergic neurons of the ventral tegmental area after chronic ethanol treatment. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2002;26:1024–1030. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000021336.33310.6B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burattini C, Gill TM, Aicardi G, Janak PH. The ethanol self-administration context as a reinstatement cue: acute effects of naltrexone. Neuroscience. 2006;139:877–887. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camarini R, Nogueira-Pires ML, Calil HM. Involvement of the opioid system in the development and expression of sensitization to the locomotor-activating effect of ethanol. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;3:303–309. doi: 10.1017/S146114570000211X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronwall BM. Anatomy and physiology of the neuroendocrine arcuate nucleus. Peptides. 1985;6:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(85)90128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccocioppo R, Lin D, Martin-Fardon R, Weiss F. Reinstatement of ethanol-seeking behavior by drug cues following single versus multiple ethanol intoxication in the rat: effects of naltrexone. Psychopharmacology. 2003;168:208–215. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1380-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CL, Henderson CM, Bormann NM. Extinction of ethanol-induced conditioned place preference and conditioned place aversion: effects of naloxone. Psychopharmacology. 1998;139:62–70. doi: 10.1007/s002130050690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CL, Ferree NK, Howard MA. Apparatus bias and place conditioning with ethanol in mice. Psychopharmacology. 2003;70:409–422. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1559-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CL, Gremel CM, Groblewski PA. Drug-induced conditioned place preference and aversion in mice. Nature Protocols. 2006;1:1662–1670. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayas CV, Liu X, Simms JA, Weiss F. Distinct patterns of neural activation associated with ethanol seeking: effects of naltrexone. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;61:979–989. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desjardins GC, Brawer JR, Beaudet A. Estradiol is selectively neurotoxic to hypothalamic beta-endorphin neurons. Endocrinology. 1993;132:86–93. doi: 10.1210/endo.132.1.8093438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Waele JP, Gianoulakis C. Effects of single and repeated exposures to ethanol on hypothalamic beta-endorphin and CRH release by the C57BL/6 and DBA/2 strains of mice. Neuroendocrinology. 1993;57:700–709. doi: 10.1159/000126428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Waele JP, Papachristou DN, Gianoulakis C. The alcohol-preferring C57BL/6 mice present an enhanced sensitivity of the hypothalamic beta-endorphin system to ethanol than the alcohol-avoiding DBA/2 mice. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1992;261:788–794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. Neural systems of reinforcement for drug addiction: from actions to habits to compulsion. Nature Neuroscience. 2005;8:1481–1489. doi: 10.1038/nn1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finley JC, Lindstrom P, Petrusz P. Immunocytochemical localization of beta-endorphin-containing neurons in the rat brain. Neuroendocrinology. 1981;33:28–42. doi: 10.1159/000123197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Font L, Aragon CMG, Miquel M. Ethanol-induced conditioned place preference, but not aversion, is blocked by treatment with D-penicillamine, an inactivation agent for acetaldehyde. Psychopharmacology. 2006;184:56–64. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0224-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froehlich JC. Genetic factors in alcohol self-administration. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1995;56:15–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froehlich JC, Badia-Elder NE, Zink RW, McCullough DE, Portoghese PS. Contributions of the opioid system to alcohol aversion and alcohol drinking. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1998;287:284–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianoulakis C. Influence of the endogenous opioid system on high alcohol consumption and genetic predisposition to alcoholism. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience. 2001;26:304–318. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianoulakis C. Endogenous opioids and addiction to alcohol and other drugs of abuse. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry. 2009;11:999–1015. doi: 10.2174/156802609789630956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianoulakis C, De Waele JP, Kiianmaa K. Differences in the brain and pituitary beta-endorphin system between the alcohol-preferring AA and alcohol-avoiding ANA rats. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1992;16:453–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1992.tb01399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianoulakis C, Krishnan B, Thavundayil J. Enhanced sensitivity of pituitary b-endorphin to ethanol in subjects at high risk of alcoholism. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;53:250–257. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830030072011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gremel CM, Cunningham CL. Roles of the nucleus accumbens and amygdala in the acquisition and expression of ethanol-conditioned behavior in mice. Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28:1076–1084. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4520-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groblewski PA, Bax LS, Cunningham CL. Reference-dose place conditioning with ethanol in mice: empirical and theoretical analysis. Psychopharmacology. 2008;201:97–106. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1251-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall FS, Sora I, Uhl GR. Ethanol consumption and reward are decreased in mu-opiate receptor knockout mice. Psychopharmacology. 2001;154:43–49. doi: 10.1007/s002130000622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herz A. Endogenous opioid systems and alcohol addiction. Psychopharmacology. 1997;129:99–111. doi: 10.1007/s002130050169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyser CJ, Roberts AJ, Schulteis G, Koob GF. Central administration of an opiate antagonist decreases oral ethanol self-administration in rats. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1999;23:1468–1476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo LA, Barros DM, Medina JH, Izquierdo I. Stress hormones enhance retrieval of fear conditioning acquired either one day or many months before. Behavioral Pharmacology. 2002;13:203–213. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200205000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzmin A, Sandin J, Terenius L, Ogren SO. Acquisition, expression, and reinstatement of ethanol-induced conditioned place preference in mice: effects of opioid receptor-like 1 receptor agonists and naloxone. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2003;304:310–318. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.041350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone P, Pocock D, Wise RA. Morphine-dopamine interaction: ventral tegmental morphine increases nucleus accumbens dopamine release. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1991;39:469–472. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(91)90210-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longoni R, Spina L, Mulas A, Carboni E, Garau L, Melchiorri P, Di Chiara G. (D-Ala2) deltorphin II: D1-dependent stereotypies and stimulation of dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens. Journal of Neuroscience. 1991;11:1565–1576. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-06-01565.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinelli PW, Quirino R, Gianoulakis C. A microdialysis profile of beta-endorphin and catecholamines in the rat nucleus accumbens following alcohol administration. Psychopharmacology. 2003;169:60–67. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1490-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mhatre M, Holloway F. μ1-opioid antagonist naloxonazine alters ethanol discrimination and consumption. Alcohol. 2003;29:109–116. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(03)00021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miquel M, Font L, Sanchis-Segura C, Aragon CMG. Neonatal administration of monosodium glutamate prevents the development of ethanol-but not psychostimulant-induced sensitization: a putative role of the arcuate nucleus. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;17:2163–2170. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Méndez M, Morales-Mulia M. Role of mu and delta opioid receptors in alcohol drinking behaviour. Current Drug Abuse Reviews. 2008;2:239–252. doi: 10.2174/1874473710801020239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers KM, Davis M. Behavioral and neural analysis of extinction. Neuron. 2002;36:567–584. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01064-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestby P, Vanderschuren LJ, De Vries TJ, Hogenboom F, Wardeh G, Mulder AH, Schoffelmeer AN. Ethanol, like psychostimulants and morphine, causes long-lasting hyperreactivity of dopamine and acetylcholine neurons of rat nucleus accumbens: possible role in behavioural sensitization. Psychopharmacology. 1997;133:69–76. doi: 10.1007/s002130050373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olive MF, Koenig HN, Nannini MA, Hodge CW. Stimulation of endorphin neurotransmission in the nucleus accumbens by ethanol, cocaine, and amphetamine. Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;21:RC184. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-23-j0002.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer AA, Low MJ, Grandy DK, Phillips TJ. Effects of a Drd2 deletion mutation on ethanol-induced locomotor stimulation and sensitization suggest a role for epistasis. Behavioral Genetics. 2003;33:311–324. doi: 10.1023/a:1023450625826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastor R, Aragon CMG. The role of opioid receptor subtypes in the development of behavioral sensitization to ethanol. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:1489–1499. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastor R, Aragon CMG. Ethanol injected into the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus induces behavioral stimulation in rats: an effect prevented by catalase inhibition and naltrexone. Behavioral Pharmacology. 2008;19:698–705. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e328315ecd7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastor R, Sanchis-Segura C, Aragon CMG. Brain catalase activity inhibition as well as opioid receptor antagonism increases ethanol-induced HPA axis activation. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2004;28:1898–1906. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000148107.64739.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Franklin KBJ. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Compact Second Edition. Elsevier; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips TJ, Wenger CD, Dorow JD. Naltrexone effects on ethanol drinking acquisition and on established ethanol consumption in C57BL/6J mice. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1997;21:691–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce RC, Kalivas PW. A circuitry model of the expression of behavioral sensitization to amphetamine-like psychostimulants. Brain Research Reviews. 1997;25:192–216. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(97)00021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risinger FO, Oakes RA. Dose- and conditioning trial-dependent ethanol-induced conditioned place preference in Swiss-Webster mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1996;55:117–123. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(96)00069-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Berridge KC. The neural basis of drug craving: an incentive sensitization theory of addiction. Brain Research Reviews. 1993;18:247–291. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(93)90013-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose SR, Orlowski J. Review of research on endorphins and learning. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. 1983;4:131–135. doi: 10.1097/00004703-198306000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth-Deri I, Mayan R, Yadid G. A hypothalamic endorphinic lesion attenuates acquisition of cocaine self-administration in the rat. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;16:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchis-Segura C, Correa M, Aragon CMG. Lesion on the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus by estradiol valerate results in a blockade of ethanol-induced locomotion. Behavioural Brain Research. 2000;114:57–63. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00183-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchis-Segura C, Grisel JE, Olive MF, Ghozland S, Koob GF, Roberts AJ, Cowen MS. Role of the endogenous opioid system on the neuropsychopharmacological effects of ethanol: new insights about an old question. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29:1522–1527. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000174913.60384.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulster A, Farookhi R, Brawer JR. Polycystic ovarian condition in estradiol valerate-treated rats: spontaneous changes in characteristic endocrine features. Biology of Reproduction. 1984;31:587–93. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod31.3.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe AL, Samson HH. Effect of naloxone on appetitive and consummatory phases of ethanol self-administration. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2001;25:1006–1011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza-Formigoni ML, De Lucca EM, Hipolide DC, Enns SC, Oliveira MG, Nobrega JN. Sensitization to ethanol's stimulant effect is associated with region-specific increases in brain D2 receptor binding. Psychopharmacology. 1999;146:262–267. doi: 10.1007/s002130051115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanagel R, Herz A, Shippenberg TS. Opposing tonically active endogenous opioid systems modulate the mesolimbic dopaminergic pathway. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 1992;89:2046–2050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart J, Badiani A. Tolerance and sensitization to the behavioral effects of drugs. Behavioral Pharmacology. 1993;4:289–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strong MN, Kaufman KR, Crabbe JC, Finn DA. Sex differences in acute ethanol withdrawal severity after adrenalectomy and gonadectomy in Withdrawal Seizure-Prone and Withdrawal Seizure-Resistant mice. Alcohol. 2009;43:367–77. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takemori AE, Portoghese PS. Comparative antagonism by naltrexone and naloxone of mu, kappa, and delta agonists. Eur J Pharmacol. 1984;104:101–104. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(84)90374-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Den Burg EH, Metz JR, Arends RJ, Devreese B, Vandenberghe I, Van Beeumen J, Wendelaar Bonga SE, Flik G. Identification of beta-endorphins in the pituitary gland and blood plasma of the common carp (Cyprinus carpio). J Endocrinol. 2001;169:271–280. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1690271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderschuren LJ, Kalivas PW. Alterations in dopaminergic and glutamatergic transmission in the induction and expression of behavioral sensitization: a critical review of preclinical studies. Psychopharmacology. 2000;51:99–120. doi: 10.1007/s002130000493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White NM, Milner PM. The psychobiology of reinforcers. Annual Reviews in Psychology. 1992;43:443–471. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.43.020192.002303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KL, Schimmel JS. Effect of naltrexone during extinction of alcohol-reinforced responding and during repeated cue-conditioned reinstatement sessions in a cue exposure style treatment. Alcohol. 2008;42:553–563. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JT, Christie MJ, Manzoni O. Cellular and synaptic adaptations mediating opioid dependence. Physiological Reviews. 2001;81:299–343. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.1.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapata A, Gonzales RA, Shippenberg TS. Repeated ethanol intoxication induces behavioral sensitization in the absence of a sensitized accumbens dopamine response in c57bl/6j and dba/2j mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:396–405. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]