Abstract

Datasets from recent large-scale projects can be integrated into one unified puzzle that can provide new insights into how drugs and genetic perturbations applied to human cells are linked to whole organism phenotypes. Data that report how drugs affect the phenotype of human cell-lines, and how drugs induce changes in gene and protein expression in human cell-lines, can be combined with knowledge about human disease, side effects induced by drugs, and mouse phenotypes. Such data integration effort can be achieved through the conversion of data from the various resources into single-node-type networks, gene-set libraries, or multi-partite graphs. This approach can lead us to the identification of more relationships between genes, drugs and phenotypes, as well as benchmark computational and experimental methods. Overall this lean “Big Data” integration strategy will bring us closer toward the goal of realizing personalized medicine.

Keywords: Systems pharmacology, data integration, network analysis, network pharmacology, side-effect prediction, target prediction

Bringing together data from open databases and data collected by large-scale team science projects

Biomedical research is moving toward large-scale team-based projects that bring together interdisciplinary teams, using high-end equipment for measuring in high-throughput the genome-wide molecular composition of human cells and tissues. This is coupled with experiments that record cellular and organismal phenotypes, as well as the development of databases and analysis tools that provide easy and open access to the masses of the accumulating data. The collection, organization, and analysis of this Big Data in the fields of systems biology and systems pharmacology are enabled by the Internet and the rapid development of biotechnologies that can be used to measure more variables faster and more accurately.

There are many large-scale projects and popular databases (Table 1 and Fig. 1) that individually already provide many new insights about how human cells work from a system-level perspective with molecular detail. Data is also collected to explain how drugs affect the phenotype of human cells, and how drugs induce changes in gene and protein expression in human cells on a global scale. Human diseases, side effects induced by drugs, and mouse phenotypes are increasingly linked to individual drugs or genes or their combinations (Fig. 1, Table 1). Putting all this information together in an intelligent way and asking the right questions can lead to the identification of more relationships between genes, drugs and phenotypes, as well as explain new functions for genes and drugs with the ultimate goal of improved personalized medicine and significantly increasing human health-span and life-span. These concepts are central to the direction in which systems biology and systems pharmacology are heading. Data integration of molecular genomic data with clinical data is the focus of the Big Data to Knowledge (BD2K) initiative of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in the USA (1,2). Data abstraction and organization for data integration, together with machine learning strategies that include supervised and unsupervised learning, are fundamental for successful applications in this emerging domain. Big Data thinking also requires a change in attitude; letting go of the obsession with causality and exactitude while embracing correlation analysis and inexactitude. This may seem like a step backward, but it is actually a step forward (3). Furthermore, more fruitful results can come from discovery based approaches that generate hypotheses, rather than ad-hoc hypothesis testing which dominated biomedical research for decades.

Table 1.

Resources that can be processed and integrated for building a global puzzle of systems biology and systems pharmacology.

| Resource | Description | Data Structures |

|---|---|---|

| Mouse Genome Informatics Mammalian Phenotype Ontology (MGI-MPO) (41,42) | Associations between mouse phenotypes and gene knock-outs | BPG, GSL (phenotype: gene knock-outs), Similarity network (gene-gene) |

| Online Mendelian Inheritance In Man (OMIM) (43,44) | Associations between heritable diseases and gene sequence aberrations | BPG, GSL (disease: genes), N (gene-gene, disease-disease) |

| Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) (26,45,46) | Genome map of transcription factor (TF) binding and histone mod. sites | BPG, GSL (TFs: putative target genes), N (TF-TF, gene-gene) |

| Roadmap Epigenomics (47,48) | Genome map of histone modifications (HMs) | BPG, GSL (HMs: putative target genes), N (HM-HM, gene-gene) |

| Cancer Target Discovery and Development (CTD2) (49–52) | Fitness of cell lines screened against pharmacologic and genetic perturbations | BPG, DSL (cell line: lethal drugs), GSL (cell line: lethal gene knockdowns), N (drug-drug, cell-cell, gene-gene) |

| Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) (53); Cancer Genome Project (CGP) Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (8) | Fitness of cell lines screened against pharmacologic perturbations, Profiles of genomic aberrations, Gene expression signatures | BPG (cell line-drug/genomic aberration-diff. expressed genes), DGL (cell line: lethal drugs), GSL (cell line: differentially expressed genes), N (drug-drug, cell-cell, gene-gene) |

| Genotype-Tissue Expression Project (GTEx) (54) | Genomic aberrations and gene expression profiled across tissues and across the population | BPG (tissue/patients-eQTLs), GSL (tissue/patients-genes), N (patients, eQTL, genes, tissues) |

| The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (55–64) | Genomic aberrations, gene expression, DNA methylation, and miRNA expression, proteomics profiled across tumor samples, clinical data | BPG (patients/genomic aberration/genes/clinical outcome), GSL (patients-genes), N (patients, genes, miRNAs) |

| FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) (65–67) | Reports of side effects experienced by patients following drug treatment | BPG (side effects: drugs), DSL (side effects: drugs), N (drug-drug, side-effect-side-effect) |

| Side Effect Resource (SIDER) (68) | Side effects of drugs reported on package label inserts | BPG (side effects: drugs), DSL (side effects: drugs), N (drug-drug, side-effect-side-effect) |

| Pharmacogenomics Knowledgebase (PharmGKB-OFFSIDES) (69,70) | Side effects of drugs derived from FAERS reports after bias correction and filtering | BPG (side effects: drugs), DSL (side effects: drugs), N (drug-drug, side-effect-side-effect) |

| DrugBank (16) | Many drug properties including indications, structure and targets | BPG and N connecting (drug/structures/indications/targets) |

| ChEMBL (71) | Small molecule biological activities | BPG (chemical structures/targets/data) |

| The Gene Ontology (72) | Functional annotations for the roles of genes across species | GSL (terms: genes), N (gene-gene, term-term) |

| WikiPathways (73), BioCarta, KEGG (74,75), Reactome (76) | Collections of curated cell signaling pathways | GSL (pathway: participating molecules), N (genes/proteins) |

| Biological Repository for Interaction Datasets (BioGRID) (77) | Repository for protein-protein interactions | N (protein-protein), GSL (protein: interacting proteins) |

| HPRD (78,79), MINT (80,81), IntAct (82,83), STRING (84) | Manually curated literature-derived protein-protein interactions | N (protein-protein), GSL (protein: interacting proteins) |

| KEA (85), PhosphositePlus (86), Phospho.ELM (87), NetworKIN (88) | Manually curated literature-derived kinase-substrate interactions | Gene-set library (kinase: substrates, kinase: interacting proteins) |

| NURSA (89), CORUM (90) | Protein complexes from IP-MS | GSL (complex: participating proteins), N (protein-protein) |

| Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) (91) | Gene expression signatures including pharmacologic or genetic perturbations in tissues and cells | GSL (perturbation: differentially expressed genes), N (perturbation-perturbation, gene-gene) |

| Connectivity Map (CMAP) and LINCS L1000 (6,92) | Expression signatures including pharmacologic or genetic perturbations applied to cancer cell lines | GSL (perturbation: differentially expressed genes), N (perturbation-perturbation, gene-gene) |

Abbreviations: BPG- bi-partite graphs, GSL- gene-set library, DSL- drug-set library, N- networks.

Fig. 1.

Over 40 large-scale projects, databases and other resources can be integrated in a coherent map to link human and mouse phenotypes to drugs, genes, expression signatures, protein-protein interaction networks and gene-gene functional association networks. This map is helpful for assembling the puzzle pieces needed to significantly enhance our understanding of the effects of drugs on the individual human phenotype at the molecular level. This diagram brings various datasets and resources together for the purpose of identifying non-trivial associations and relationship enabling discovery and assisting in converting data to knowledge.

The diagram in Figure 1 displays various relevant data types, their relationships, and the online open access resources for establishing links between those data types. These resources can be integrated into one coherent puzzle. Starting from left to right, cancer cell lines are made from human tumors and are profiled by methods such as RNA-seq, microarrays, or the newly introduced L1000 technology, for measuring gene expression at the genome-wide scale. At the same time, DNA sequence variations are profiled with whole genome DNA sequencing, exome-seq, CNV and SNP arrays and other methods. In addition, the chromatin status of cells is measured by histone modifications and transcription factor binding profiling with ChIP-seq, DNA methylation arrays, or Hi-C and many other methods. Moreover, methods such as proteomics and phosphoproteomics can measure the cell signaling networks activity levels within those cancer cells. These cancer cell-lines are also interrogated for their sensitivity to drugs and to genetic perturbations such as knock-down or over-expression of single genes. Gene expression measurements after drug or single gene perturbation, when done in high throughput, can produce expression signatures. Gene expression signatures are vectors of differential expression, and these signatures can be related to a biological condition, for example, the progression of a disease, or the classification of disease subtypes (4). Such signatures can be considered comparable high dimensional vectors that point to different directions in N-dimensional space. Such directions can be due to drug or single gene genetic perturbations (Figure 2). A collection of signatures produced in high throughput is supported by the NIH Common Fund project Library of Integrated Network-based Cellular Signatures (LINCS) (https://commonfund.nih.gov/LINCS). The gene expression based high-throughput screening concept (5) was elevated with the construction of the first version of the Connectivity Map. The first version of the Connectivity Map over 6000 gene expression microarray experiments where over one thousand drugs, mostly FDA approved, were applied to four human cell lines in different concentrations and changes in gene expression were measured after six hours (6). The next generation of the Connectivity Map (CMAP) is producing many more signatures using the L1000 technology. Members of the CMAP team at the Broad Institute have already conducted over one million experiments using the L1000 technology. They applied over 20,000 small molecules to stimulate many human cancer cell-lines at different concentrations and where gene expression was measured at different time points. Together with the CMAP team we developed methods to visualize a query this huge dataset (7).

Fig. 2.

Eighty eight drugs were applied at four doses: 0.08μm, 0.4μm, 2μm and 10μm to MCF10A breast cancer cell-line and then gene expression changes were measured at two time points: 6 and 24 hours, resulting in 352 experiments in total. The gene expression values of 978 landmark genes responding to these treatment conditions and control experiments were measured using the L1000 platform. Characteristic direction analysis (33) was applied on the normalized gene expression values to calculate a gene expression signature for each experiment. A gene expression signature is a vector made of the 978-genes occupying 978-dimensional-space whose direction represents in which way the experiment deviates from control and whose norm represents strength of the experiment. The strengths were compared to a null distribution so that each gene expression signature was assigned a z-score to quantify the strength of each perturbation. Only those highly significant experiments whose z-scores are greater than 5 were reserved for visualization. The gene expression vectors of these highly significant experiments were transformed into the first three principal components using PCA analysis and then plotted. The directions of the perturbation vectors fall into four groups (I–IV). Examining the labels of these experiments, we observe a time-dependency: experiments of different time points do not fall into the same group. The drug targets of the visualized experiments are also grouped. Drugs in groups I and IV target kinases within the growth factor activated pathways, whereas drugs in group II and III mainly targeting CDKs.

At the same time, high content drug sensitivity assays that measure phenotypic response of cell lines to drugs, when the drugs are applied in different concentrations, are gradually emerging. These assays can be performed in high-throughput to measure cell phenotypes, for example cell viability, as a function of dose for panels of cancer cell-lines in response to panels of relevant drugs (8–10). Such data provide another type of link that connects drugs and cell-lines. Furthermore, clinical documentation of FDA approved drugs, many of which are also used to profile cancer cell-lines in those high content assays mentioned above, connects drugs to the human phenotype. These links can be indications for the drug, or side effects induced by the drug. Knowledge about side-effects can come from several sources including the two primary open resources: Side Effect Resource (SIDER) (11) and the FDA Adverse Events Reporting System (FAERS) (http://www.fda.gov/CDER/aers). SIDER provides a computational format of drug label inserts containing information about side effects, whereas FAERS provides post-marketing reports of side effects. FAERS contains millions of records from spontaneous reports entered by physicians reporting side effects observed by their anonymized patients for the drugs that the patients took.

Databases such as PharmGKB (12) provide processed data extracted from FAERS and other resources for further analysis (13). Side effects and diseases can overlap, be similar and sometimes even indistinguishable. For example, common severe drug side effects such as neuropathy or long QT syndrome are also genetically inheritable diseases (14). At the same time, side effects and diseases often can be observed in knock-out mouse models. The MGI mouse phenotype ontology is a well-organized dataset containing accumulated knowledge about knockout mouse phenotypes (15). By integrating knockout mouse phenotypes with side effect resources and with drug target information, which can be found at open databases such as DrugBank (16), it is possible to match knockout genes to drug targets and ultimately connect disease phenotypes observed in mice to side effects observed in patients. Such links provide a possible molecular explanation for observed side effects. This analysis can be extended to include human disease genes found in databases such as the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) (17) for human inheritable diseases, or the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) (18) for disease genes mutated in cancer. Once genes that cause an analogous human disease phenotype in mice have been identified, human gene-gene and protein-protein interactions networks can be used to identify the disease and side-effect connected modules of gene or proteins within these networks. Such modules potentially mediate the observed diseases and phenotypes. However, our current understanding of the human interactome is still partial and suffers from research biases that skew the connectivity distribution in those networks toward the well-studied proteins. Hence, molecular interaction networks extracted from many publications that present results from low-throughput studies should be used with caution when reused and integrated with other data.

One consideration that should be noted is that cells are part of tissues, and different tissues respond differently to drugs or genetic perturbations because they are wired differently at the intra- and inter-cellular levels, containing different network configurations and concentrations of the drug targets in the various cells that constitute the tissue. Efforts such as the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project (19) are trying to link gene expression signatures in various tissues to mutations within specific human genes. A related issue is the heterogeneity of tumors, in which several cell types at different stages of tumor development can co-exist within a single tumor.

The ultimate goal is to discover how individual patients fit into this complex network of relationships and how this can be leveraged for their personal therapeutic gain. Efforts such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (http://cancergenome.nih.gov/) collect longitudinal clinical data of patient outcome and drugs used together with gene expression, protein expression and mutation status of tumors collected from those patients at time of diagnosis. Understanding similarities and differences among individuals when it comes to drug response and side effects is the ultimate challenge. Such understanding will lead us to better personalized data driven therapeutic strategies which are gradually becoming a reality.

Data Integration with single node type networks, gene-set libraries and bi-partite graphs

To integrate data from the various relevant resources described in Figure 1, there are three relatively simple and related data structures that can be used: single-node-type networks, gene-set libraries, and bi-partite graphs (Figure 3). Single-node-type networks are the most obvious and commonly applied data structure to abstract and integrate gene-gene and protein-protein interaction networks. Furthermore, drug-drug, disease-disease, patient-patient, side-effect/side-effect, phenotype-phenotype, and cell-line/cell-line association networks can also be created based on correlation or some other measure of similarity based on the attributes of the entities in each network. The edges or connections between entities within those single-node-type networks can be weighted and can be of different types. For example, an edge that connects two transcription factors can be based on similar target genes, physical protein-protein interaction between the factors, correlation observed by their co-expression, or a binding site for one factor found at the promoter of the gene that encodes for the other factor. Each of these types of edges may produce a different network, created from one of these various independent or dependent sources. So far most networks created from such data have unweighted edges, throwing away useful information for the purpose of data abstraction, but keeping the weights can be useful for improving accuracy. Cluster identification algorithms can be used to identify modules within each of those networks. Such module identification procedures fall under the umbrella of unsupervised learning. Modules are typically defined as dense regions within the network connectivity which are loosely connected to other modules. Such module identification process and the modular architecture of the networks under investigation can often better explain known functions or discover new functions. The other common use of single-node-type networks is the ability to use these networks to find connections between two entities. For example, lists of genes or proteins identified experimentally can be connected into a subnetwork with seeding algorithms such as the short path algorithm (20,21) or the mean first passage time method (14).

Fig. 3.

Resources from systems biology and systems pharmacology can be integrated by first identifying the various objects, their relations, and their data types, and then converting the data into single entity weighted networks, fuzzy set libraries, or weighted multi-partite graphs.

To integrate two or more data types, bi-partite or multi-partite graphs, or gene-set libraries can be developed from almost all the data resources listed in Figures 1 and 3, and Table 1. A gene-set library is a data structure that contains a family of sets. Each set is associated with a label that describes what is common about the genes within the set. By definition each set can be of different length, i.e., containing different numbers of genes. These sets are semantically related where the labels cover a common resource belonging to a specific knowledge domain. For example, a gene set library created from the KEGG pathways database has labels that are pathway names and the sets contain the genes within each pathway (22). Although initially such gene-set libraries were developed for the purpose of performing gene-set enrichment analyses (GSEA) (23), they can be used to organize entities such as drugs, diseases, patients, side effects, mouse phenotypes, and cell-lines. For developing the web-based software application Enrichr (24) we compiled 36 gene set libraries from many of the resources mentioned above. For another tool called Network2Canvas (25), we developed six different types of drug-set libraries. These drug-set libraries contain FDA approved drugs instead of genes. Such drug-set libraries can be used to perform drug-set enrichment analysis (DSEA).

As stated above, the initial primary use of gene-set libraries was for GSEA (23). Given a list of genes identified experimentally, GSEA uses gene-set libraries to identify and rank prior knowledge gene-sets that overlap with an input list of experimentally identified genes. Such method is a powerful approach to detect the collective functions of newly identified lists of genes. However, gene-set libraries can be used for other types of analyses. For example, comparing and combining two gene-set libraries can be used to detect unexpected relationships between different sources of data types. For instance, measuring the overlap between all sets from a gene-set library created from differentially expressed genes in tumors from patients and a gene-set library created from the ENCODE ChIP-seq dataset that profiled human transcription factors in cancer cell lines (26) can be used to assign putative transcription factors as potential drivers of gene expression changes in the individual patient tumor (27) (Figure 4). Gene-set libraries so far have been unweighted. This means that the membership level of genes within the sets is the same for all genes across the entire library. However, this can be done differently by considering “fuzzy” gene-set libraries. With fuzzy gene-set libraries, genes within the library can have different membership levels which vary between full-membership to no membership, making gene-set libraries weighted. Such addition of information should make gene set enrichment analysis, and other uses of gene-set libraries, more accurate.

Fig. 4.

Computing gene set overlap between a gene-set library made of up-regulated genes in individual tumors from breast cancer patients from TCGA with a gene set library created by identifying the putative transcription factor target genes from ChIP-seq experiments conducted by ENCODE. Clusters of gene set that significantly overlap (brown spots) are labeled based on the most common transcription factor/s identified within the cluster. To create the breast cancer patients gene set library, Affymetrix microarray gene expression data from 536 breast cancer patients were downloaded from the TCGA. Average expression was computed for genes with multiple probes. For each gene, a Z score was computed by take the average and standard deviation across all patients. Genes that are highly and significantly expressed in each tumor were retained for constructing the gene set library containing 536 patients as the labels and the genes that passed the threshold (p<0.01) as the gene sets associated with each patient. To create the ENCODE gene set library 920 experiments applied to 44 cell lines profiling 160 transcription factors were processed. We retain the target genes that had significant peaks within +2k bp of their transcription starting site (TSS). Since most experiments have replicates, we only kept genes identified in both replicates. The ENCODE gene-set library contains 434 unique experiments. Gene set overlap was computed using the Fisher exact test. The hierarchical clustering plot was created with MATLAB using the Bioinformatics ToolBox.

The third data structure is bi-partite or multi-partite graphs. This data structure fits very well with the data integration goal. Many of the connections in the plot shown in Figure 1 can be made into bi-partite graphs. For example, drugs and their targets (28), drugs and the cell lines that show highest sensitivity to the drugs, drugs and side effects, genes and diseases, drugs and signatures, and more. Such bi-partite networks can then be connected into tri- and other multi-partite graphs, and this enables the identification of non-trivial relationships. For example, drug/cell-line bipartite networks can be combined with cell-line/patient-tumor networks and this can lead to potential assignment of drugs to patients (29) (Figure 5).

Fig. 5.

Tri-partite network that integrates gene expression data from cancer cell-lines and patient tumors with drug response data for cancer cell lines. The network connects groups of patients, cell-lines, and drugs to suggest drugs for patients. Edges between patient groups and cell-lines are colored based on higher (red) or lower (green) expression correlation. Edges between cell-lines and drugs are colored based on higher (magenta/purple) to lower (cyan) drug sensitivity.

The single-node-type network, gene-set library, and bi-partite graph data structures are related. For example, a single-node-type network can be created from a gene-set library or a bi-partite graph. In the past, we showed how a gene-set library can be converted to a network using the Sets2Networks algorithm (30). In addition, bi-partite graphs can be converted to gene-set libraries and vice versa, and gene-set libraries can be transposed. For example, a kinase-substrate bi-partite network can be converted into a kinase-substrate gene-set library in which the set labels are kinases and the genes within the sets are the kinase substrates. A kinase-kinase network can also be created from such kinase-substrate bi-partite graphs by connecting kinases based on their common substrates. If the kinase-substrate gene-set library is transposed, the substrates can be connected based on the kinases they share. The kinase-substrate example can be a bit confusing since kinases can be substrates of other kinases, but this example is valid, and the principle is universal and can be applied to many other types of data.

Data management and integration projects in systems biology and systems pharmacology best practices have embraced the creation of ontologies (31) and their application using standard protocols such as Extensible Markup Language (XML). Such an approach to data integration separates data from metadata, captures the hierarchical structure of the granularity of objects within a domain, as well as removes the requirement for silo-specific data standards and protocols. Although these concepts have been useful and are now becoming standards, there is still room for leaner data organization and integration strategies that further simplify data integration and exchange. One important consideration for data integration, regardless of whether the data is converted to fit ontologies, networks or gene-sets, is the harmonization of identifiers. Dictionaries that map name spaces and convert IDs are important to establish, share and maintain. Another consideration is the quality of data curation. The extraction of computable data records from the multiple sources mentioned above requires knowledge domain expertise combined with knowledge of data structures, statistics and computer programming. The extraction of data from databases, research publication text, medical records, or supplementary materials of publications is not always trivial. The quality of the resulting extracted data is highly dependent on the quality of the human curator.

Benchmarking methods for data gathering and processing by data integration

The inference of biological meaning from data depends crucially on the applied methods of data processing, normalization, curation and analysis. However, identifying the optimal methods to apply can be difficult because an absence of a gold-standard to which each method can be compared. For example, different computational methods exist for performing gene-set enrichment analyses or for identifying differentially expressed genes but evaluating the performance of each is difficult. For example, until recently, there is no clear and unbiased way to tell which genes should be considered as the right differentially expressed genes. With gene-set enrichment analysis methods, each method may result in different rankings of terms from a gene-set library given differentially expressed genes. However, how can we tell which rankings is more correct? In the case of determining the correct differentially expressed genes, given control and treatment condition samples, different statistical methods and cutoffs result in different lists of up and down genes. How can we tell which computational method is detecting the right differentially expressed gene, reflecting the real biological state change of the cells or tissue under investigation?

Frequently, this issue is sidestepped by comparing methods in the setting of synthetic data. Synthetic data is created by a computer program that generates data, based on few simple rules, with the aim of producing a tunable artificial dataset that mimics general properties of real experimental data. However, synthetic data is unsatisfactory because models of biological data do not contain all the rich structure of real biological data. Others have attempted to compare methods of analysis by considering the degree of agreement of each method with the others to be a proxy for the quality of the computational method (32). In our recent publication which describes a novel method to identify differentially expressed genes (33), we compared our new approach, called the Characteristic Direction, to the other currently most popular methods: SAM (34), limma (35), and DESeq (36,37) as well as other less sophisticated methods such as the t-test of fold change. Using real biological data obtained through lean data integration, we were able to benchmark the various methods that prioritize differentially expressed genes by examining gene expression profiles before and after transcription factor perturbations: knockdowns, knock-outs and over-expressions, and compare the gene lists called by the various methods with data from ChIP-seq studies that profiled the binding location of those same transcription factors to the proximity of transcribed genes. More overlap between the independently collected mRNA expression data and the ChIP-seq data is likely an indicator that the method used to call the differentially expressed genes is likely better (Figure 6).

Fig. 6.

Genes were ranked according to their significance of differential expression after transcription factor perturbation and this was scaled such that the most significant gene received a scaled rank of r=0 and the least significant gene has r=1. The scaled ranks of all genes associated with binding sites of the perturbed transcription factor in ENCODE experiments were identified and this process was repeated over 73 experiments in which transcription factor perturbations were followed by gene expression profiling, and the cumulative distribution D(r) was calculated. After subtracting the expected cumulative distribution in the cases of a random uniform distribution, corresponding to the null hypothesis of no enrichment of the genes associated with the perturbed transcription factor from the ENCODE data, we plot the cumulative distributions for each of the five differential expression approaches. In order to indicate the significance of the deviations form a uniform random distribution we also indicate the values scaled by the expected standard deviation ψ. Note that the greater the peak of the resulting curve, the greater priority the method assigns to genes associated with the perturbed transcription factor in independent ENCODE experiments.

We make the reasonable assumption that the genes associated with the DNA binding sites identified in the ChIP-seq experiments of the perturbed transcription factor, are more likely to be differentially expressed after perturbation of that transcription factor, regardless of the cell type and even the mammalian organism. This way we are able to use the collective degree of prioritization of these genes as a measure of the quality of the analysis method. The significance of these comparisons increases by application to large number of transcription factor perturbation experiments. In this way we used the apparent degree of consistency of the gene expression data and ChIP-seq data to quantify the quality of the various analysis methods. This example provides a workable solution to determining the optimal methodology for data processing and analysis. This approach has the potential to significantly improve the resolution of biological insight of this type of data but is also relevant beyond this specific example. For example, this same data and setup can also help benchmarking methods that call target genes from ChIP-seq experiments that profile individual transcription factors to tell us how to best process data from ChIP-seq studies.

Combining multiple sources of evidence to make predictions and improve predictions

The example of benchmarking computational methods described above can be viewed from another perspective: We essentially created a transcription-factor/transcription-factor network from the knockdown followed by expression data, and also created another transcription-factor/transcription-factor network from the ChIP-seq data and then examined the consistency between these two networks. The more consistent these two networks are the assumption is that the better the methods used to create such networks, computationally as well as experimentally. In other words, greater similarity between these networks implies a greater apparent consistency between transcription-factor binding data and gene expression data; this may reasonably be taken as a measure of the combined quality of the experimental procedures and analysis methods. Hence, networks created for connecting the same type of objects: genes, drugs, cell, or phenotypes, using different independent methods can be used to validate one another. This is true regarding both the computational and experimental methods used to collect and process the data. For example, drug/side-effect networks can connect drugs to form a drug-drug network where the edges are shared side-effects. At the same time, a drug-drug chemical structure similarity network can be created to connect drugs to other drugs to form a network. These are two independent sources to create drug-drug networks. If there is some overlap within specific regions of those two networks, then we can identify drug chemical structural elements that can predict side effects. Finally, if a third drug-drug similarity network can be established from another independent resource, the combination of evidence from two networks can be used to improve overlap with the third network. This means that combined evidence from two independent sources can potentially improve predictability of novel relationships between entities connected by a third source. Hence, networks created from independent sources can be used as attributes that when combined, can better predict connections for a third, less determined network. Such predictions can then be validated with more data or empirically. As an example, we show how side-effect prediction for FDA-approved drugs can be significantly improved when combining a drug-drug chemical structure similarity network with a drug-drug similarity network created from gene expression profile similarity when these drugs are applied to human cells and gene expression is measured by the L1000 technology after drug treatment. Programs such as ChemmineR (38) can be used to convert drug SMILES strings to a binary vector that can be used to compute drug-drug similarity but also used as a set of attributes for classification. Drugs chemical structure is known to only provide a weak signal when it is attempted to be correlated with human phenotypes. However, when combined with drug induced expression signatures (LINCS L1000 data), which also on their own have weak relationship with side-effects, the two together can predict side-effect profiles much better (Figure 7). This type of classifier can be useful for predicting side-effect profiles for new drugs. The only thing that is needed is the expression signature of the new drug in human cell lines and the molecular structure of the drug, both can be relatively easily obtained. Similarly, desired phenotypes can be predicted for new drugs using the flip side of the coin of this method.

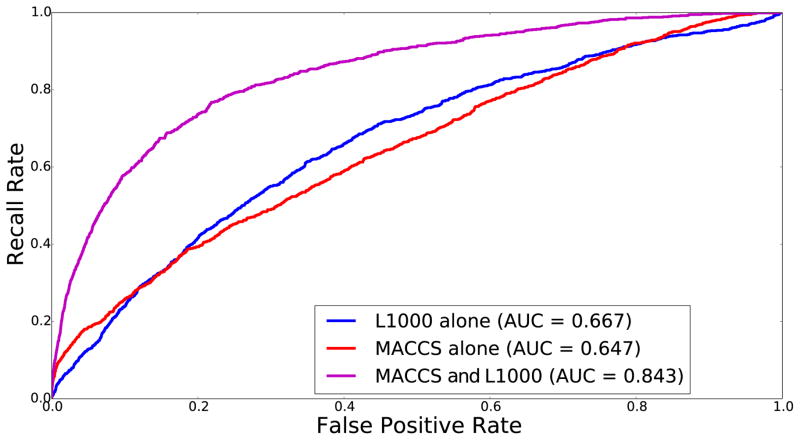

Fig. 7.

Two drug-drug similarity networks, one based on chemical structure and the other based on gene expression signatures, are used to predict a drug-drug similarity network that is based on shared side-effects. The R library ChemmineR was used to create the drug-drug similarity network based on structure (38). The simplified molecular-input line-entry system (SMILES) strings of 1,409 FDA-approved drugs were converted to a binary string representing 166 Molecular ACCess System (MACCS) structural elements of the drugs. Then, to create a drug-drug similarity network, Jaccard index was used to measure the overlap between shared structural elements for each pair of drugs. Gene expression data from the LINCS L1000 project were obtained from the CPC and CPD batches by selecting the most significant perturbation amongst all dosages, time points, and cell types for each compounds treatment based on the signature strength as defined by the documentation on the lincscloud.org web-site (‘distil_ss’ value). To create a drug-drug similarity network, the Pearson’s correlation coefficient was computed between all pairs of drugs applied to the expression values of the 978 landmark genes. The side-effect drug-drug similarity network was created from SIDER by first creating a gene-set library where the drugs are the terms and the side-effects are the set elements. The Sets2Networks algorithm (30) was used to compute similarity between drugs. The interactions between drugs were sorted and ROC curves were plotted based on matched interaction. To combine the L1000 and MACCS scores, the normalized scores were simply added.

Concluding remarks

Data management in biological and biomedical research in the past three decades has been messy. This is particularly true for low throughput molecular and cell biology studies, of which it was recently suggested that only a small fraction of published results are reproducible (39), and research focus is biased towards the well-studied genes and proteins (40). Low-throughput biology is driven by research biases to study specific molecular components, and where community level quality control remains largely the burden of journal editors and ad-hoc peer-reviewers. As biological and biomedical research moves towards Big-Data, data rich science, and high-throughput methods that can measure the levels of molecular species in cells all at once in a single experiment, we have the opportunity and challenge to fix the messy, biased, non-reproducible problems that have plagued the field for decades. To achieve this goal, we need to develop methods to evaluate new data in the context of existing data and fit new data in the puzzle of cells, assays, phenotypes, drugs, genes, proteins, and signatures. Here we provided only few examples how this can be achieved, but in addition we set the stage for many potential projects that can explore different aspects of the entire puzzle. In addition, the framework discussed provides a template for inclusion of new data that will be gathered in the coming years.

Highlights.

Many relevant resources from systems biology and pharmacology can be combined into a general map

Data from the resources can be converted to networks, gene-set libraries, and bi-partite graphs

Indirect relationships, e.g. matching drugs to patients, can be identified by data integration

Combining independent sources can be used to validate computational and experimental methods

Predictions can be improved when two independent networks are used to predict a third network

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by NIH grants R01GM098316-01A1, U54HG006097-S1 to AM. We thank Drs. Mario Medvedovic and Stephan Schurer for useful discussions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jenkins SL, Ma’ayan A. Systems pharmacology meets predictive, preventive, personalized and participatory medicine. Pharmacogenomics. 2013;14:119–122. doi: 10.2217/pgs.12.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berger SI, Iyengar R. Network analyses in systems pharmacology. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2466–2472. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mayer-Schönberger V, Cukier K. Big data: A revolution that will transform how we live, work, and think. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chibon F. Cancer gene expression signatures–The rise and fall? European Journal of Cancer. 2013;49:2000–2009. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stegmaier K, Ross KN, Colavito SA, O’Malley S, Stockwell BR, Golub TR. Gene expression–based high-throughput screening (GE-HTS) and application to leukemia differentiation. Nature genetics. 2004;36:257–263. doi: 10.1038/ng1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lamb J, Crawford ED, Peck D, Modell JW, Blat IC, Wrobel MJ, Lerner J, Brunet JP, Subramanian A, Ross KN, et al. The Connectivity Map: using gene-expression signatures to connect small molecules, genes, and disease. Science (New York, NY) 2006;313:1929–1935. doi: 10.1126/science.1132939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duan Q, Flynn C, Niepel M, Hafner M, Muhlich JL, Fernandez NF, Rouillard AD, Tan CM, Chen EY, Golub TR. LINCS Canvas Browser: interactive web app to query, browse and interrogate LINCS L1000 gene expression signatures. Nucleic acids research. 2014:gku476. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garnett MJ, Edelman EJ, Heidorn SJ, Greenman CD, Dastur A, Lau KW, Greninger P, Thompson IR, Luo X, Soares J, et al. Systematic identification of genomic markers of drug sensitivity in cancer cells. Nature. 2012;483:570–575. doi: 10.1038/nature11005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barretina J, Caponigro G, Stransky N, Venkatesan K, Margolin AA, Kim S, Wilson CJ, Lehar J, Kryukov GV, Sonkin D. The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia enables predictive modelling of anticancer drug sensitivity. Nature. 2012;483:603–607. doi: 10.1038/nature11003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heiser LM, Sadanandam A, Kuo W-L, Benz SC, Goldstein TC, Ng S, Gibb WJ, Wang NJ, Ziyad S, Tong F, et al. Subtype and pathway specific responses to anticancer compounds in breast cancer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018854108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuhn M, Campillos M, Letunic I, Jensen LJ, Bork P. A side effect resource to capture phenotypic effects of drugs. Molecular Systems Biology. 2010;6 doi: 10.1038/msb.2009.98. n/a-n/a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hewett M, Oliver DE, Rubin DL, Easton KL, Stuart JM, Altman RB, Klein TE. PharmGKB: the pharmacogenetics knowledge base. Nucleic acids research. 2002;30:163–165. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tatonetti NP, Patrick PY, Daneshjou R, Altman RB. Data-driven prediction of drug effects and interactions. Science translational medicine. 2012;4:125ra131–125ra131. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berger SI, Ma’ayan A, Iyengar R. Systems pharmacology of arrhythmias. Science signaling. 2010;3:ra30. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith CL, Goldsmith CAW, Eppig JT. The Mammalian Phenotype Ontology as a tool for annotating, analyzing and comparing phenotypic information. Genome biology. 2004;6:R7. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-6-1-r7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knox C, Law V, Jewison T, Liu P, Ly S, Frolkis A, Pon A, Banco K, Mak C, Neveu V, et al. DrugBank 3.0: a comprehensive resource for ‘omics’ research on drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D1035–1041. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamosh A, Scott AF, Amberger JS, Bocchini CA, McKusick VA. Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), a knowledgebase of human genes and genetic disorders. Nucleic acids research. 2005;33:D514–D517. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bamford S, Dawson E, Forbes S, Clements J, Pettett R, Dogan A, Flanagan A, Teague J, Futreal PA, Stratton M. The COSMIC (Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer) database and website. British journal of cancer. 2004;91:355–358. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lonsdale J, Thomas J, Salvatore M, Phillips R, Lo E, Shad S, Hasz R, Walters G, Garcia F, Young N. The genotype-tissue expression (GTEx) project. Nature genetics. 2013;45:580–585. doi: 10.1038/ng.2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berger SI, Posner JM, Ma’ayan A. Genes2Networks: connecting lists of gene symbols using mammalian protein interactions databases. BMC bioinformatics. 2007;8:372. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dannenfelser R, Clark NR, Ma’ayan A. Genes2FANs: connecting genes through functional association networks. BMC bioinformatics. 2012;13:156. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic acids research. 2000;28:27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen EY, Tan CM, Kou Y, Duan Q, Wang Z, Meirelles GV, Clark NR, Ma’ayan A. Enrichr: interactive and collaborative HTML5 gene list enrichment analysis tool. BMC bioinformatics. 2013;14:128. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tan CM, Chen EY, Dannenfelser R, Clark NR, Ma’ayan A. Network2Canvas: network visualization on a canvas with enrichment analysis. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:1872–1878. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Consortium TEP. A User’s Guide to the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) PLoS Biology. 2011;9:e1001046. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duan Q, Kou Y, Clark NR, Gordonov S, Ma’ayan A. Meta-Signatures Identify Two Major Subtypes of Breast Cancer. CPT: PSP. 2013 doi: 10.1038/psp.2013.11. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma’ayan A, Jenkins SL, Goldfarb J, Iyengar R. Network analysis of FDA approved drugs and their targets. Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine: A Journal of Translational and Personalized Medicine. 2007;74:27–32. doi: 10.1002/msj.20002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duan Q, Kou Y, Clark N, Gordonov S, Ma’ayan A. Metasignatures identify two major subtypes of breast cancer. CPT: Pharmacometrics & Systems Pharmacology. 2013;2:e35. doi: 10.1038/psp.2013.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clark NR, Dannenfelser R, Tan CM, Komosinski ME, Ma’ayan A. Sets2Networks: network inference from repeated observations of sets. BMC systems biology. 2012;6:89. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-6-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith B, Ashburner M, Rosse C, Bard J, Bug W, Ceusters W, Goldberg LJ, Eilbeck K, Ireland A, Mungall CJ. The OBO Foundry: coordinated evolution of ontologies to support biomedical data integration. Nature biotechnology. 2007;25:1251–1255. doi: 10.1038/nbt1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hung JH, Yang TH, Hu Z, Weng Z, DeLisi C. Gene set enrichment analysis: performance evaluation and usage guidelines. Briefings in bioinformatics. 2012;13:281–291. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbr049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clark NR, Hu K, Feldmann AS, Kou Y, Chen EY, Duan Q, Ma’ayan A. The Characteristic Direction: A Geometrical Approach to Identify Differentially Expressed Genes. BMC bioinformatics. 2014 doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-15-79. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tusher VG, Tibshirani R, Chu G. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2001;98:5116–5121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091062498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smyth GK. Bioinformatics and computational biology solutions using R and Bioconductor. Springer; 2005. pp. 397–420. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anders S. Analysing RNA-Seq data with the DESeq package. Molecular biology. 2010:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome biol. 2010;11:R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cao Y, Charisi A, Cheng LC, Jiang T, Girke T. ChemmineR: a compound mining framework for R. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:1733–1734. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Begley CG, Ellis LM. Drug development: Raise standards for preclinical cancer research. Nature. 2012;483:531–533. doi: 10.1038/483531a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Isserlin R, Bader GD, Edwards A, Frye S, Willson T, Yu FH. The human genome and drug discovery after a decade. Roads (still) not taken. 2011 arXiv preprint arXiv:1102.0448. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith CL, Goldsmith CW, Eppig JT. The Mammalian Phenotype Ontology as a tool for annotating, analyzing and comparing phenotypic information. Genome Biol. 2004;6:R7. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-6-1-r7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blake JA, Bult CJ, Eppig JT, Kadin JA, Richardson JE Mouse Genome Database G. The Mouse Genome Database: integration of and access to knowledge about the laboratory mouse. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D810–817. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Amberger J, Bocchini C, Hamosh A. A new face and new challenges for Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM(R)) Human mutation. 2011;32:564–567. doi: 10.1002/humu.21466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Amberger J, Bocchini CA, Scott AF, Hamosh A. McKusick’s Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D793–796. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.The EPC. The ENCODE (ENCyclopedia Of DNA Elements) Project. Science. 2004;306:636–640. doi: 10.1126/science.1105136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rosenbloom KR, Sloan CA, Malladi VS, Dreszer TR, Learned K, Kirkup VM, Wong MC, Maddren M, Fang R, Heitner SG, et al. ENCODE data in the UCSC Genome Browser: year 5 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D56–63. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bernstein BE, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Costello JF, Ren B, Milosavljevic A, Meissner A, Kellis M, Marra MA, Beaudet AL, Ecker JR. The NIH roadmap epigenomics mapping consortium. Nature biotechnology. 2010;28:1045–1048. doi: 10.1038/nbt1010-1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chadwick LH. The NIH roadmap epigenomics program data resource. Epigenomics. 2012;4:317–324. doi: 10.2217/epi.12.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Network TCTDaD. Towards patient-based cancer therapeutics. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:904–906. doi: 10.1038/nbt0910-904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Basu A, Bodycombe NE, Cheah JH, Price EV, Liu K, Schaefer GI, Ebright RY, Stewart ML, Ito D, Wang S, et al. An interactive resource to identify cancer genetic and lineage dependencies targeted by small molecules. Cell. 2013;154:1151–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cheung HW, Cowley GS, Weir BA, Boehm JS, Rusin S, Scott JA, East A, Ali LD, Lizotte PH, Wong TC, et al. Systematic investigation of genetic vulnerabilities across cancer cell lines reveals lineage-specific dependencies in ovarian cancer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:12372–12377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109363108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim HS, Mendiratta S, Kim J, Pecot CV, Larsen JE, Zubovych I, Seo BY, Kim J, Eskiocak B, Chung H, et al. Systematic identification of molecular subtype-selective vulnerabilities in non-small-cell lung cancer. Cell. 2013;155:552–566. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Barretina J, Caponigro G, Stransky N, Venkatesan K, Margolin AA, Kim S, Wilson CJ, Lehar J, Kryukov GV, Sonkin D, et al. The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia enables predictive modelling of anticancer drug sensitivity. Nature. 2012;483:603–607. doi: 10.1038/nature11003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Consortium GT. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. Nat Genet. 2013;45:580–585. doi: 10.1038/ng.2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cancer Genome Atlas N. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012;487:330–337. doi: 10.1038/nature11252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cancer Genome Atlas N. Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2012;490:61–70. doi: 10.1038/nature11412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature. 2008;455:1061–1068. doi: 10.1038/nature07385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature. 2011;474:609–615. doi: 10.1038/nature10166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Comprehensive genomic characterization of squamous cell lung cancers. Nature. 2012;489:519–525. doi: 10.1038/nature11404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Comprehensive molecular characterization of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Nature. 2013;499:43–49. doi: 10.1038/nature12222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Genomic and epigenomic landscapes of adult de novo acute myeloid leukemia. The New England journal of medicine. 2013;368:2059–2074. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Kandoth C, Schultz N, Cherniack AD, Akbani R, Liu Y, Shen H, Robertson AG, Pashtan I, Shen R, et al. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature. 2013;497:67–73. doi: 10.1038/nature12113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Weinstein JN, Collisson EA, Mills GB, Shaw KR, Ozenberger BA, Ellrott K, Shmulevich I, Sander C, Stuart JM. The Cancer Genome Atlas Pan-Cancer analysis project. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1113–1120. doi: 10.1038/ng.2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.The Cancer Genome Atlas Research, N. Comprehensive molecular characterization of urothelial bladder carcinoma. Nature. 2014 doi: 10.1038/nature12965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Moore TJ, Cohen MR, Furberg CD. Serious Adverse Drug Events Reported to the Food and Drug Administration, 1998–2005. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1752–1759. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.16.1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sakaeda T, Tamon A, Kadoyama K, Okuno Y. Data mining of the public version of the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System. International journal of medical sciences. 2013;10:796–803. doi: 10.7150/ijms.6048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Weiss-Smith S, Deshpande G, Chung S, Gogolak V. The FDA Drug Safety Surveillance Program: Adverse Event Reporting Trends. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171 doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kuhn M, Campillos M, Letunic I, Jensen LJ, Bork P. A side effect resource to capture phenotypic effects of drugs. Molecular systems biology. 2010;6:343. doi: 10.1038/msb.2009.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tatonetti NP, Ye PP, Daneshjou R, Altman RB. Data-driven prediction of drug effects and interactions. Science translational medicine. 2012;4:125ra131. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hewett M, Oliver DE, Rubin DL, Easton KL, Stuart JM, Altman RB, Klein TE. PharmGKB: the pharmacogenetics knowledge base. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:163–165. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bento AP, Gaulton A, Hersey A, Bellis LJ, Chambers J, Davies M, Kruger FA, Light Y, Mak L, McGlinchey S, et al. The ChEMBL bioactivity database: an update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D1083–1090. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT. Gene Ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nature genetics. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kelder T, van Iersel MP, Hanspers K, Kutmon M, Conklin BR, Evelo CT, Pico AR. WikiPathways: building research communities on biological pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D1301–1307. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kanehisa M, Goto S, Sato Y, Kawashima M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M. Data, information, knowledge and principle: back to metabolism in KEGG. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D199–205. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ogata H, Goto S, Sato K, Fujibuchi W, Bono H, Kanehisa M. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic acids research. 1999;27:29–34. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Croft D, Mundo AF, Haw R, Milacic M, Weiser J, Wu G, Caudy M, Garapati P, Gillespie M, Kamdar MR, et al. The Reactome pathway knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D472–477. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chatr-Aryamontri A, Breitkreutz BJ, Heinicke S, Boucher L, Winter A, Stark C, Nixon J, Ramage L, Kolas N, O’Donnell L, et al. The BioGRID interaction database: 2013 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D816–823. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Peri S, Navarro JD, Amanchy R, Kristiansen TZ, Jonnalagadda CK, Surendranath V, Niranjan V, Muthusamy B, Gandhi TK, Gronborg M, et al. Development of human protein reference database as an initial platform for approaching systems biology in humans. Genome Res. 2003;13:2363–2371. doi: 10.1101/gr.1680803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Keshava Prasad TS, Goel R, Kandasamy K, Keerthikumar S, Kumar S, Mathivanan S, Telikicherla D, Raju R, Shafreen B, Venugopal A, et al. Human Protein Reference Database--2009 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D767–772. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Licata L, Briganti L, Peluso D, Perfetto L, Iannuccelli M, Galeota E, Sacco F, Palma A, Nardozza AP, Santonico E, et al. MINT, the molecular interaction database: 2012 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D857–861. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zanzoni A, Montecchi-Palazzi L, Quondam M, Ausiello G, Helmer-Citterich M, Cesareni G. MINT: a molecular interaction database. FEBS letters. 2002;513:135–140. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03293-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hermjakob H, Montecchi-Palazzi L, Lewington C, Mudali S, Kerrien S, Orchard S, Vingron M, Roechert B, Roepstorff P, Valencia A, et al. IntAct: an open source molecular interaction database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D452–D455. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kerrien S, Aranda B, Breuza L, Bridge A, Broackes-Carter F, Chen C, Duesbury M, Dumousseau M, Feuermann M, Hinz U, et al. The IntAct molecular interaction database in 2012. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D841–846. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Franceschini A, Szklarczyk D, Frankild S, Kuhn M, Simonovic M, Roth A, Lin J, Minguez P, Bork P, von Mering C, et al. STRING v9.1: protein-protein interaction networks, with increased coverage and integration. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D808–815. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lachmann A, Ma’ayan A. KEA: kinase enrichment analysis. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:684–686. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hornbeck PV, Kornhauser JM, Tkachev S, Zhang B, Skrzypek E, Murray B, Latham V, Sullivan M. PhosphoSitePlus: a comprehensive resource for investigating the structure and function of experimentally determined post-translational modifications in man and mouse. Nucleic acids research. 2012;40:D261–D270. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Diella F, Cameron S, Gemünd C, Linding R, Via A, Kuster B, Sicheritz-Ponten T, Blom N, Gibson TJ. Phospho. ELM: a database of experimentally verified phosphorylation sites in eukaryotic proteins. BMC bioinformatics. 2004;5:79. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Linding R, Jensen LJ, Pasculescu A, Olhovsky M, Colwill K, Bork P, Yaffe MB, Pawson T. NetworKIN: a resource for exploring cellular phosphorylation networks. Nucleic acids research. 2008;36:D695–D699. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Malovannaya A, Lanz RB, Jung SY, Bulynko Y, Le NT, Chan DW, Ding C, Shi Y, Yucer N, Krenciute G, et al. Analysis of the human endogenous coregulator complexome. Cell. 2011;145:787–799. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ruepp A, Brauner B, Dunger-Kaltenbach I, Frishman G, Montrone C, Stransky M, Waegele B, Schmidt T, Doudieu ON, Stümpflen V. CORUM: the comprehensive resource of mammalian protein complexes. Nucleic acids research. 2008;36:D646–D650. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Barrett T, Wilhite SE, Ledoux P, Evangelista C, Kim IF, Tomashevsky M, Marshall KA, Phillippy KH, Sherman PM, Holko M, et al. NCBI GEO: archive for functional genomics data sets--update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D991–995. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lamb J. The connectivity map: a new tool for biomedical research. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2007;7 doi: 10.1038/nrc2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]