Abstract

Background

Individuals with COPD and asthma are an important but poorly characterized group. The genetic determinants of COPD-asthma overlap have not been studied.

Objective

Identify clinical features and genetic risk factors for COPD-asthma overlap.

Methods

Subjects were current or former smoking non-Hispanic whites (NHW) or African-Americans (AA) with COPD. Overlap subjects reported a history of physician-diagnosed asthma before the age of 40. We compared clinical and radiographic features between COPD and overlap subjects. We performed genome-wide association studies (GWAS) in the NHW and AA populations, and combined these results in a meta-analysis.

Results

More women and African Americans reported a history of asthma. Overlap subjects had more severe and more frequent respiratory exacerbations, less emphysema, and greater airway wall thickness compared to subjects with COPD alone. The NHW GWAS identified SNPs in CSMD1 (rs11779254, P=1.57×10−6) and SOX5(rs59569785, P=1.61×10−6) and the meta-analysis identified SNPs in the gene GPR65 (rs6574978, P=1.18×10−7) associated with COPD-asthma overlap.

Conclusions

Overlap subjects have more exacerbations, less emphysema and more airway disease for any degree of lung function impairment compared to COPD alone. We identified novel genetic variants associated with this syndrome. COPD-asthma overlap is an important syndrome and may require distinct clinical management.

Introduction

The presence of asthma among subjects with COPD is well recognized, and up to 24% of patients with COPD will additionally report a history of asthma (1). However, few studies have investigated the clinical features of this overlap syndrome, and none have investigated the genetics of this syndrome. The dual diagnosis of COPD and asthma is often an exclusion criterion in most studies investigating these diseases individually, limiting the large-scale cohorts available for investigation. Despite this, there is growing evidence that subjects with both COPD and asthma represent an important and distinct patient population, with worse clinical features than those with COPD alone (2, 3). In recognition of this important subset of patients, the Spanish, Canadian and Japanese respiratory societies have recently included the identification and management of these subjects in their COPD guidelines (4–6).

Both COPD and asthma are heritable diseases with known genetic risk factors. Recent candidate gene and genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified genetic variants associated with COPD and asthma individually, and several of these variants have been associated with both diseases in candidate gene studies (7, 8). However, no genetic studies have been performed in this overlap group that has both COPD and asthma.

In a previous paper, we investigated the clinical features of the overlap population in the first 2500 subjects enrolled in the COPDGene study (3). In that analysis, we demonstrated that overlap subjects had more respiratory exacerbations despite fewer pack-years of smoking. The COPDGene study has now completed enrollment, with over 10,000 subjects enrolled. We took advantage of this larger data set, which includes quantitative chest CT analysis and genome-wide genotyping, to better characterize the clinical, radiographic, and genetic features of this overlap group. We hypothesized that this larger cohort of subjects with more complete CT phenotyping and genetic data would allow us to expand on the clinical features we had previously identified. Specifically, radiographic features would demonstrate that this is a pathologically distinct clinical group, and our genetic analysis would identify unique genetic risk factors.

Methods

Subjects

The subjects from COPDGene were non-Hispanic white (NHW) or African American (AA) current or former smokers between the age of 45–80 with at least a ten pack-year history of smoking (9). All subjects completed study questionnaires, performed standardized spirometry and had volumetric chest CT scan at full inspiration and relaxed expiration. Study protocols are available at www.copdgene.org. Bronchodilator responsiveness was defined as having a post-bronchodilator improvement in FEV1 of > 200 ml and 12%(10). Quantitative bronchodilator response was measured as the absolute difference between post-bronchodilator FEV1 and pre-bronchodilator FEV1. Maternal and paternal asthma were based on subject self-report. Hay fever history was based on subject self report of physician-diagnosed hay fever. Exacerbations were defined as the number of respiratory exacerbations experienced in the year prior to enrolling in COPDGene, and severe exacerbations were defined as a history of having a respiratory exacerbation that resulted in an emergency room visit or hospital stay. Quantitative emphysema was defined as the percentage of lung area with low attenuation areas less than −950 Hounsfield units (HU), using SLICER software (http://www.slicer.org/) (11). Airway wall thickening was measured as the square root of the wall area of a hypothetical 10 mm internal perimeter airway (pi10) (12). Airway wall thickening, segmental and subsegmental wall area were quantified using VIDA software (VIDA Diagnostics, Coralville, IA, http://www.vidadiagnostics.com/) as previously described (13). Percent gas trapping was defined as the percentage of lung voxels with attenuation less than −856 HU on expiratory CT imaging (9, 14). Subjects provided written informed consent, and the COPDGene Study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Partners Healthcare and all participating centers.

Statistical analysis

This analysis was restricted to COPD subjects with GOLD stage II or greater (FEV1/FVC < 0.7, FEV1 < 80% predicted). Overlap subjects are defined as those with COPD who additionally reported a history of asthma that was diagnosed by a physician before the age of 40. These overlap subjects were compared to subjects with COPD alone. We performed an additional sensitivity analysis comparing subjects with COPD to those with COPD and atopic asthma, defined by a physician diagnosis of hayfever in addition to asthma. Logistic and linear regression models were used to compare binary and quantitative measures of disease respectively, adjusting for age, race, sex, and pack-years of smoking. CT measures of emphysema were additionally adjusted for current smoking status, and along with wall thickness were additionally adjusted for CT scanner model and body-mass index. We performed a parallel analysis excluding the original 915 subjects who participated in the initial study (online supplement), as well as an analysis including all subjects with COPD GOLD stage 1–4.

Genetic analysis

All subjects were genotyped on the Illumina HumanOmniExpress array (Illumina, San Diego, CA). All single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) passed quality control as previously described (15). Additional imputation of over six million SNPs was performed using MaCH and minimac (16, 17), with the 1000 Genomes Phase I v3 European reference panel for the NHW subjects and cosmopolitan reference panels for AA subjects. This resulted in over six million SNPs for analysis. Due to our small sample size and lack of an available replication population, we removed all SNPs with minor allele frequency < 5% and imputed SNPs with Rsq < 0.80, leaving 5,333,124 NHW SNPs and 6,593,020 AA SNPs for analysis. Principal components for genetic ancestry were generated for NHW and AA subjects separately, using the program EIGENSOFT2.0(18).

PLINK (19) was used for genome-wide association analysis of autosomal SNPs in a case-control analysis, comparing subjects with COPD and asthma to subjects with COPD alone, adjusted for age, sex, pack-years as well as population-defined principal components for genetic ancestry. GWAS testing incorporated both genotyped and imputed SNPs under an additive genetic model. GWAS was performed separately in the non-Hispanic white and African American subjects, and a fixed-effects meta-analysis was completed to combine these two groups using METAL (20). We used PLINK to test for linkage disequilibrium(LD) and SNAP(21) to present regional association plots of our most significant associations. We additionally investigated previously identified asthma SNPs from the Gabriel and EVE consortia (22, 23) as well as 10 SNPs previously associated with COPD (24) (online supplement).

Results

Clinical characteristics

Subject demographics are presented in table 1. Subjects with COPD and asthma were younger (60.0 years old vs 64.0 years old, P<0.001), had higher BMI (28.2 kg/m2 vs 27.9 kg/m2, P=0.006) and had fewer pack-years of smoking (45.7 pack-years vs 54.2 pack-years, P<0.001). A greater percentage of women (56% vs 43%, P<0.001) and African Americans (37% vs 20%, P=0.006) were in the overlap cases. There was no difference in the percentage of subjects with a positive bronchodilator response or in absolute bronchodilator response between the two groups.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics

| COPD | COPD & Asthma | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 3120 | 450 | |

| Age (years) | 64.0 (8.4) | 60.0 (8.7) | <0.001 |

| Female (%) | 1335 (42.8) | 252 (56) | <0.001 |

| African-American (%) | 627 (20.1) | 167 (37.1) | <0.001 |

| Pack-years smoking | 54.2 (27.8) | 45.7 (25.1) | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.9 (6.1) | 28.8 (6.9) | 0.006 |

| FEV1 (L) | 1.45 (0.63) | 1.40 (0.62) | 0.16 |

| FEV1 Percent Predicted | 50.3 (18.0) | 50.3 (17.9) | 0.95 |

| FEV1/FVC | 0.49 (0.13) | 0.51 (0.13) | 0.02 |

| Emphysema | 13.54 (12.95) | 9.93 (11.5) | <0.001 |

| Bronchodilator responsive (%) | 1120 (36.13) | 177 (39.42) | 0.19 |

| Absolute BDR (L) | 0.09 (0.16) | 0.11 (0.16) | 0.11 |

BDR: bronchodilator response. Values are given as mean (sd) or N (percent) as appropriate.

In multivariate analyses adjusting for age, race, gender and pack-years of smoking, we compared clinical features and risk factors between the overlap subjects and those with COPD alone (Table 2). Subjects with COPD and asthma had worse measures of disease severity including higher BODE score (3.1±2.0 vs 2.9±2.1, P=0.02), and higher St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire Scores (47.4±22.7 vs 39.7±21.5, P < 0.001). Overlap subjects had more exacerbations per year (1.2±1.6 vs 0.7±1.2, P<0.001), and a greater percentage of these subjects had severe exacerbations resulting in emergency room visit or hospital stay in the previous year (34.0% vs 20.7%, P<0.007). These subjects were more likely to have a history of hay fever that was diagnosed by a physician (50.3% vs 17.8%, P<0.001), and were more likely to have a mother (19% vs 7%, P<0.001) and father (17.5% vs 5.9 %, P<0.001) with asthma. Overlap subjects had a significantly greater quantitative increase in FEV1 in response to bronchodilators (0.11±0.16 L/s v 0.09±0.16 L/s, β=0.02 (0.008), P=0.03), however these differences were clinically minimal. These results were similar when comparing subjects with COPD to those with COPD and atopic asthma (supplementary data, Table 1). We performed a parallel analysis including only those subjects who were not included in the first analysis(3), and these findings remained significant (supplementary data, Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical features of subjects with COPD and asthma compared to those with COPD alone.

| COPD | COPD & Asthma | Effect size | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female Sex (%) | 1335 (42.8) | 252 (56.0) | 1.59 [1.29, 1.95] | <0.001 |

| African American race (%) | 627 (20.1) | 167 (37.1) | 1.74[1.39, 2.18] | <0.001 |

| Bronchodilator response (%) | 1120 (36.1) | 177 (39.4) | 1.19 [0.97, 1.47] | 0.10 |

| Absolute BDR (L) | 0.09 (0.16) | 0.11 (0.16) | 0.02 (0.008) | 0.03 |

| BODE score | 2.9 (2.1) | 3.1 (2.0) | 0.25 (0.1) | 0.02 |

| St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire score | 39.7 (21.5) | 47.4 (22.7) | 6.81 (1.1) | <0.001 |

| Exacerbations per year | 0.7 (1.2) | 1.2 (1.6) | 0.56 (0.06) | <0.001 |

| Severe Exacerbations (%) | 646 (20.7) | 153 (34.0) | 1.70 [1.36, 2.12] | <0.001 |

| Hay fever (%) | 442 (17.8) | 186 (50.3) | 4.66 [3.68, 5.90] | <0.001 |

| High school graduates (%) | 1828 (58.6) | 261 (58.0) | 1.10 [−0.19, 0.39] | 0.54 |

| Maternal asthma | 162 (7.0) | 57 (19.0) | 2.22 [1.59, 3.12] | <0.001 |

| Paternal asthma | 123 (5.9) | 47 (17.5) | 2.64 [1.82, 3.83] | <0.001 |

Linear and logistic regression models adjusted for age, race, gender, and pack-years smoking. β (se) or OR [95% confidence interval] for having COPD and asthma compared to COPD alone. BDR: Bronchodilator response defined by ATS/ERS criteria (>200ml and 12% change in FEV1).

We additionally performed a sensitivity analysis in subjects with GOLD stage 1–4 COPD comparing the overlap subjects to those with COPD alone. In this analysis, overlap subjects demonstrated no difference in radiographic emphysema (COPD-asthma: 1.36±1.54 % vs COPD: 1.74±1.45 %, β=−0.07±0.07, P=0.33). The remainder of the analysis was similar to the primary analysis in GOLD 2–4 subjects (data not shown).

As the COPD-asthma subjects demonstrated higher BMI, we performed an analysis additionally adjusting for BMI. Adjusting for BMI strengthened the association between the overlap syndrome and higher BODE score (β=0.28+/−0.11, P=0.008) and had minimal impact on the number of exacerbations per year (β=0.55+/−0.06, P<0.001) or the odds ratio for severe exacerbations (OR 1.70 [1.36,2.13], P<0.001) and did not significantly impact the associations from the remainder of the analysis (data not shown).

We compared the imaging features between the subjects with COPD and asthma and those with COPD alone, adjusting for age, gender, race, BMI and CT scanner type (Table 3). Overlap subjects had less emphysema (9.9±13.5% vs 13.5±13.0, P=0.01), and more airway disease, measured by wall area of segmental airways (63.64±3.28 mm vs 62.75±3.03mm, P=0.001) and subsegmental airways (66.36±2.66 mm vs 65.61±2.33 mm, P=0.001) as well as square root wall area of 10 mm airways (3.8±0.2 mm vs 3.7±0.1 mm, P<0.001). There was no significant difference in gas trapping between the two groups.

Table 3.

Chest CT scan features of the COPD-asthma population compared to COPD alone.

| COPD | COPD & Asthma | Beta (se)* | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log Emphysema (%) | 1.91 (1.4) | 1.44 (1.6) | −0.23 (0.07) | <0.001 |

| Pi10 (mm) | 3.71 (0.14) | 3.78 (0.16) | 0.06 (0.01) | <0.001 |

| Segmental airway wall area percent | 62.8 (3.0) | 63.6 (3.3) | 0.61 (0.16) | <0.001 |

| Subsegmental airway wall area percent | 65.6 (2.3) | 66.4 (2.7) | 0.66 (0.20) | 0.001 |

| Gas trapping (%) | 39.7 (20.7) | 35.6 (21.5) | 0.88 (1.5) | 0.55 |

Regression models are adjusted for age, gender, pack-years, BMI, and CT scanner type. Emphysema analysis additionally adjusted for current smoking status. Gas trapping additionally adjusted for clinical center. Beta refers to effect size for COPD and asthma group.

Genetic analysis

In a genome-wide analysis of COPD and asthma compared to COPD alone, there were no SNPs that exceeded a genome-wide significance threshold of 5×10−8 among NHW or AA subjects. Tables 4 and 5 present the most significant variants within each group. The most significant variant among NHW cases was located within the CSMD1 gene on chromosome 8 (rs11779254, P=1.57×10−6) (supplementary figure 1). A variant located within an intronic region in the SOX5(SRY (sex determining region Y)-box5) gene on chromosome 12 (rs59569785, P=1.61 × 10−6) was the second most highly ranked SNP (supplementary figure 2).

Table 4.

Most significant genome-wide association results for the overlap of COPD and asthma among non-Hispanic whites.

| Chr | SNP | Gene/nearest gene | Allele | MAF | Beta | SE | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | rs11779254 | CSMD1 | G | 0.42 | −0.47 | 0.10 | 1.57×10−6 |

| 12 | rs59569785 | SOX5 | C | 0.17 | −0.54 | 0.11 | 1.61×10−6 |

| 12 | rs10860172 | RMST | C | 0.33 | 0.50 | 0.11 | 2.55×10−6 |

| 12 | rs16926459 | SOX5 | G | 0.84 | 0.52 | 0.11 | 3.39×10−6 |

| 5 | rs72812713 | SEMA6A | T | 0.16 | −0.52 | 0.11 | 4.48×10−6 |

| 8 | rs6997939 | CSMD1 | C | 0.33 | −0.44 | 0.10 | 4.53×10−6 |

| 9 | rs4298581 | ZDHHC21 | C | 0.07 | −0.69 | 0.15 | 5.65×10−6 |

| 12 | rs11108963 | RMST | C | 0.31 | 0.51 | 0.11 | 5.66×10−6 |

| 9 | rs10810196 | ZDHHC21 | T | 0.07 | −0.71 | 0.16 | 5.75×10−6 |

| 9 | rs112457842 | ZDHHC21 | G | 0.07 | −0.69 | 0.15 | 5.79×10−6 |

Genes shown either contain the variant or are located within 500kb from the variant. Allele refers to minor allele. MAF: minor allele frequency.

Table 5.

Most significant genome-wide association results for the overlap of COPD and asthma among African Americans.

| Chr | SNP | Gene/nearest gene | Minor Allele | MAF | OR | CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | rs2686829 | PKD1L1 | T | 0.14 | 2.41 | 2.07,2.75 | 4.03×10−7 |

| 13 | rs9577395 | ATP11A | G | 0.08 | 0.35 | −0.09,0.78 | 1.90×10−6 |

| 10 | rs3864801 | REEP3 | C | 0.29 | 2.23 | 1.90,2.56 | 1.94×10−6 |

| 8 | rs12681559 | NRG1 | G | 0.07 | 0.36 | −0.06,0.78 | 2.25×10−6 |

| 4 | rs28895885 | AGA | T | 0.05 | 0.28 | −0.26,0.81 | 2.72×10−6 |

| 10 | rs6479918 | REEP3 | G | 0.32 | 2.06 | 1.75,2.36 | 3.63×10−6 |

| 1 | rs115905118 | KCNK1 | C | 0.06 | 0.33 | −0.14,0.80 | 3.79×10−6 |

| 13 | rs12585036 | ATP11A | T | 0.09 | 0.40 | 0.0,0.79 | 3.84×10−6 |

| 4 | rs10213448 | AGA | T | 0.05 | 0.28 | −0.25,0.82 | 3.90×10−6 |

| 1 | rs16859141 | KCNK1 | A | 0.06 | 0.33 | −0.14,0.80 | 4.51×10−6 |

Genes shown either contain the variant or are located within 500kb from the variant. Allele refers to minor allele. MAF: minor allele frequency.

Among the African-American subjects, there were also several variants that approached genome-wide significance. The most significant SNP (rs2686829, P=4.03×10−7) is located in the PKD1L1 gene on chromosome 7. The two top SNPs in the NHW population (rs11779254 and rs59569785) that were associated with the overlap status in the NHW were not significant in the AA population, although the effect size was in the same direction.

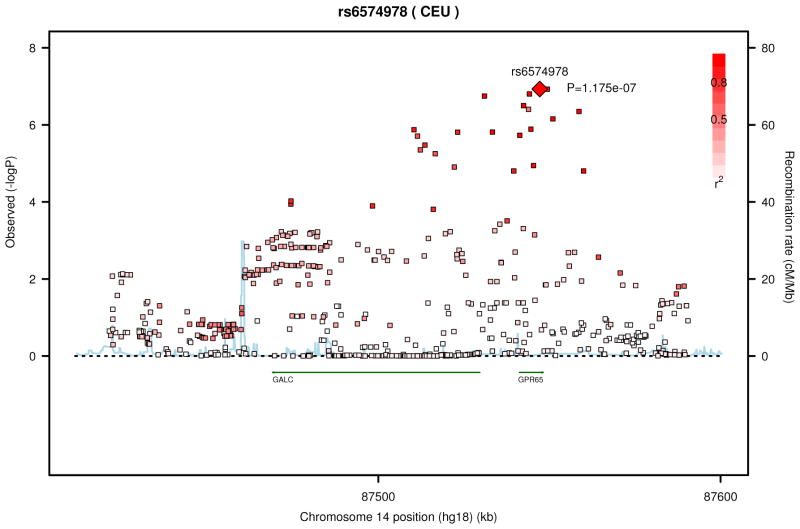

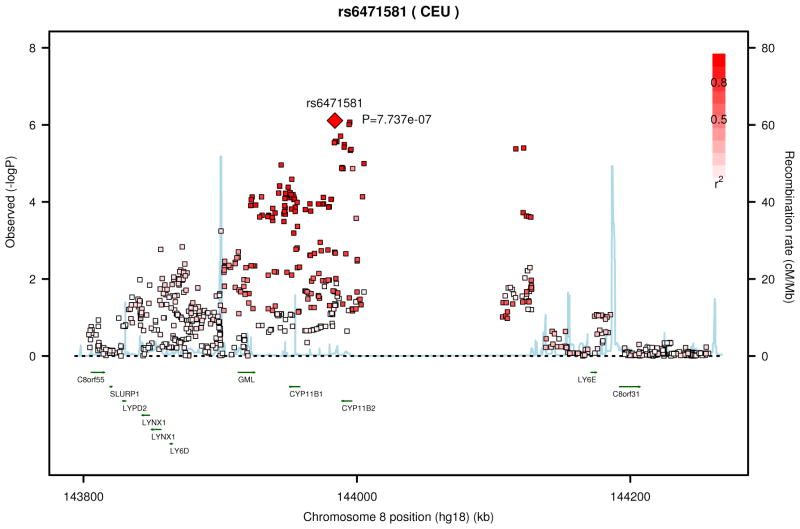

We performed a meta-analysis between the results from the NHW and AA subjects (Table 6, supplementary figures 3 and 4). The most significant SNPs were in or near the gene GPR65 (G protein coupled receptor 65) on chromosome 14 (Figure 1). These SNPs were located in coding (rs6574987, P=1.18 × 10−7), upstream (rs8004567, P=1.18×10−7), and intronic (rs14418089, P=1.58×10−7) regions, and demonstrated linkage disequilibrium (R2 = 0.8–1.0).

Table 6.

Most significant genome-wide association results for the overlap of COPD and asthma in the meta-analysis of NHW and AA.

| CHR | SNP | Gene/nearest gene | Reference Allele | OR | CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 | rs6574978 | GPR65 | T | 1.59 | 0.29,1.76 | 1.18×10−7 |

| 14 | rs8004567 | GPR65 | A | 0.61 | −0.68,0.79 | 1.18×10−7 |

| 14 | rs1441809 | GPR65 | A | 1.58 | 0.29,1.76 | 1.58×10−7 |

| 14 | rs3759712 | GALC | C | 0.63 | −0.63,0.80 | 1.80×10−7 |

| 14 | rs6574977 | GPR65 | A | 0.64 | −0.62,0.81 | 3.16×10−7 |

| 14 | rs2165570 | GPR65 | T | 0.67 | −0.56,0.82 | 3.95×10−7 |

| 14 | rs6574980 | LOC283587 | T | 1.60 | 0.29,1.78 | 4.48×10−7 |

| 14 | rs7157094 | GPR65 | T | 0.63 | −0.64,0.81 | 7.00×10−7 |

| 8 | rs6471581 | CYP11B2 | T | 0.66 | −0.57.0.83 | 7.74×10−7 |

| 8 | rs4736359 | CYP11B2 | T | 1.51 | 0.25,1.67 | 7.79×10−7 |

Figure 1.

Regional association plot from the top meta-analysis results for SNPs in or near GPR65 (A) and CYP11B2 (B).

We examined known asthma SNPs for their association with the overlap syndrome (supplementary data, table 5). SNPs in the gene HLA-DQ were nominally significantly associated with COPD-asthma overlap (rs2647012, P=0.0056) and several additional SNPs were also nominally significant with P < 0.05 (rs12150298, PERLD1; rs130065, CCHCR1), however these associations do not meet strict multiple testing correction. We additionally tested known COPD SNPs from the genes HHIP(rs13118928), FAM13a(rs7671167, rs2869967), CHRNA3/5/IREB2(rs1051730, rs8034191, rs2568494), RIN3(rs754388 and rs17184313), and MMP12(rs626750 and rs17368814) for their association with the COPD-asthma overlap, and none of these SNPs were significantly associated.

Discussion

In a large study of non-Hispanic white and African American subjects with COPD, we demonstrate that subjects with both COPD and asthma have more frequent and severe respiratory exacerbations despite similar lung function and fewer pack years of smoking exposure compared to subjects with COPD alone. Women and African Americans were more likely to have both COPD and asthma. We identified imaging differences between these two groups. Subjects with both COPD and asthma demonstrate greater airway wall thickness and less emphysema than subjects with COPD alone. In the genetic analyses, we identified several variants associated with the overlap of COPD and asthma that approach genome-wide significance. The two most significant associations among NHW overlap subjects include variants from the CSMD1 gene, which has been associated with emphysema(25), and within the SOX5 gene, which has previously been associated with COPD and may play a role in lung development (26). In a meta-analysis across the NHW and AA groups, we identified several variants in the GPR65 gene that are associated with the overlap syndrome. To our knowledge, our study is the largest study of smokers with COPD and asthma with such comprehensive imaging and genetic data, and the only study to include genetic information on African-American subjects with COPD and asthma.

In a previous analysis, we investigated the clinical features of this overlap syndrome in the first 2500 subjects enrolled in the COPDGene study, which included 915 subjects with COPD of whom 119 had an additional history of asthma(3). We demonstrated that subjects with COPD and asthma have more respiratory exacerbations, and more severe exacerbations than those with COPD alone, despite similar smoking exposure and lung function. These findings remained significant in our current study, even after removing the initial 915 subjects from analysis (Supplementary Table 1). Our present study adds comprehensive chest CT data to investigate differences in airways and parenchyma between these subjects, and allows us to explore shared genetic origins between these two groups (8).

Our current analysis is consistent with prior data suggesting that subjects with both COPD and asthma are at greater risk for respiratory exacerbations. Asthmatic subjects with fixed airway obstruction have demonstrated greater lung function decline and respiratory exacerbations (27). The presence of more frequent respiratory exacerbations among the overlap group supports the concept that this is a distinct clinical group with greater morbidity (28). In contrast to our results, a recent study from Spain using the same definitions for COPD/asthma did not demonstrate an increase in exacerbation frequency in the overlap group compared to COPD subjects with either an emphysematous or chronic bronchitic phenotype(29). However, the sample size was smaller, with fewer female and no African American subjects.

We demonstrate that both women and African Americans are more likely to be present in the overlap population. Women and African Americans have a greater incidence of asthma than non-Hispanic whites and women are often more likely to be diagnosed with asthma than COPD(30). There is evidence that both women and African Americans have different COPD susceptibility and clinical presentations than non-Hispanic whites, including greater susceptibility to cigarette smoke and worse symptom-related quality of life(31, 32). This current study is unique in our ability to characterize features of the overlap syndrome among African Americans.

Our analysis is one of the first to describe the imaging features of the overlap of COPD and asthma. We demonstrate that subjects with COPD and asthma have less emphysema, but thicker airways than subjects with COPD alone. This data extends that of prior studies demonstrating distinct pathologic and radiographic features among asthmatics with fixed airway disease. Asthmatics who smoke have thicker airway epithelium by biopsy than those who do not smoke, and this thickened epithelium is correlated to respiratory symptoms including increased phlegm production and shortness of breath(33). When compared to subjects with COPD, asthmatics with fixed airflow obstruction demonstrate less emphysema by CT scan and thicker reticular basement membrane on bronchial biopsy(34). The radiographic features of thickened airways correlate with histologic changes in the small airways(12), and our findings suggest that the airflow limitation in the overlap subjects may result from different pathologic changes in the small airways than among subjects with COPD alone.

We performed a genome-wide association study for genetic variants that could be associated with the COPD/asthma overlap. The “Dutch hypothesis” proposes that COPD and asthma share common genetic risk factors, modified by environmental exposures to produce different clinical phenotypes(8, 35). The goal of this GWAS was to identify genetic risk factors that are present in the overlap population, compared to COPD alone. Although our study is likely underpowered and no markers achieved conventional levels of genome-wide significance (p<5×10−8), several of the top SNPs are of interest. Variants located within the CSMD1 gene were among the most significant associations identified in a recent GWAS examining radiographic features of emphysema(25). Our group has previously demonstrated several variants 3′ to the SOX5 gene were located within a region of genetic linkage and associated with COPD in multiple cohorts. Additionally, the SOX5 knockout mouse has been shown to have abnormal lung development(26). It is possible that abnormalities in lung development could predispose to fixed airway disease among subjects with asthma, suggesting a common genetic origin of asthma and COPD. Among the African American subjects, we did not identify any significant associations with the overlap of COPD and asthma, likely related to the smaller sample size of this population.

In a meta-analysis of NHW and AA, we identified several coding and noncoding SNPs in the GPR65 gene as associated with the overlap syndrome. The SNP with the lowest P value approached genome-wide significance. The protein product of GPR65, G protein coupled receptor 65, is a member of the G2A G protein-coupled receptor family and plays an important role in eosinophil activation during asthma and extracellular inhibition of proinflammatory cytokines(36). This protein is expressed in eosinophils and plays a role in acid-mediated eosinophil viability. Gpr65 knock-out mice have demonstrated attenuated airway eosinophilia in murine asthma models(37). Future studies with larger samples of genotyped subjects with COPD and asthma may reveal a significant role for this gene in COPD-asthma overlap.

Our study has several limitations. The COPDGene Study enrolled adult smokers with and without COPD, and is one of the few large COPD studies that did not exclude subjects with asthma. We based our analysis of asthma on self-reported history of asthma, which could be subject to recall bias or physician misdiagnosis. We used an age limit of 40 for diagnosis in an attempt to better capture early-onset asthma. Using this definition, we are able to identify a distinct population that demonstrates both clinical and imaging features that are different than those of subjects with COPD alone. These subjects additionally have more hay fever, and are more likely to have a parental history of asthma, lending validity to the distinct nature of this group. Of note, there was no significant difference in the number of subjects exhibiting a response to bronchodilator between the two groups, highlighting the limited ability of this trait to identify asthma in COPD. This is a cross-sectional analysis, and we are therefore limited in our ability to examine the long-term outcomes. However, as a surrogate, the higher BODE score suggests that the COPD-asthma overlap subjects may have greater risk of mortality. Future longitudinal studies in this population may better demonstrate differential clinical outcomes between these populations.

The GWAS found interesting associations with biologically plausible genes, but did not identify any genome-wide significant results. This is likely a result of our relatively small sample size compared to GWAS of other chronic diseases. The genetic architecture of the overlap group is likely similar to other complex traits, with multiple markers of small effect size being involved. Unfortunately, as COPDGene is unique in its inclusion of a large proportion of COPD subjects with a history of asthma, there is not an adequately sized cohort to enable us to replicate our genetic findings.

Our study has potential clinical implications. Although the subjects in our study were primarily identified on the basis of their spirometry, spirometry is less common in outpatient clinics and is often underutilitzed. Our study identified a group of subjects with asthma and fixed airway obstruction. It is important for physicians to consider the presence of fixed airway disease, especially among asthmatic patients who smoke. Additionally, the presence of distinct radiographic features in this group, with features that are more consistent with asthma, suggests that treatment plans for these patients that incorporate aspects of asthma management such as earlier use of inhaled corticosteroids could potentially be beneficial. Finally, we identify that more women and African Americans have COPD-asthma overlap Clinicians should be alert to the possible coexistence of both disorders in all patients, but especially these populations.

In summary, we defined a subgroup of subjects who have COPD and asthma. These subjects demonstrate distinct clinical features compared to those with COPD alone. Subjects with COPD and asthma are an important clinical population that may have distinct genetic risk factors. Longitudinal follow-up in COPDGene will characterize disease progression. Future therapeutic studies are needed to identify optimal treatment approaches for patients with concurrent asthma and COPD.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1: Regional association plots for top NHW GWAS results

Supplementary Figure 2: Regional association plots for top AA GWAS results

Supplementary Figure 3: Quantile-quantile plot for P values from meta-analysis

Supplementary Figure 4: Manhattan plot representing −log10 P values for meta-analysis results

Acknowledgments

Funding: T32 HL007427-31 (MH), R01HL089856 (EKS), R01HL089897 (JDC), R01NR013377 (CPH), R01HL094635 (CPH), P01HL083069

The COPDGene project is supported by grant awards from the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute. The COPDGene® project is also supported by the COPD Foundation through contributions made to an Industry Advisory Board comprised of AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Pfizer, Siemens and Sunovion.

We acknowledge and thank the COPDGene Core Teams:

Administrative Core: James Crapo, MD (PI), Edwin Silverman, MD, PhD (PI), Barry Make, MD, Elizabeth Regan, MD, PhD, Rochelle Lantz, Lori Stepp, Sandra Melanson,

Genetic Analysis Core: Terri Beaty, PhD, Barbara Klanderman, PhD, Nan Laird, PhD, Christoph Lange, PhD, Michael Cho, MD, Stephanie Santorico, PhD, John Hokanson, MPH, PhD, Dawn DeMeo, MD, MPH, Nadia Hansel, MD, MPH, Craig Hersh, MD, MPH, Peter Castaldi, MD, MSc, Merry-Lynn McDonald, PhD, Jing Zhou, MD, PhD, Manuel Mattheissen, MD, PhD, Emily Wan, MD, Megan Hardin, MD, Jacqueline Hetmanski, MS, Margaret Parker, MS, Tanda Murray, MS

Imaging Core: David Lynch, MB, Joyce Schroeder, MD, John Newell, Jr., MD, John Reilly, MD, Harvey Coxson, PhD, Philip Judy, PhD, Eric Hoffman, PhD, George Washko, MD, Raul San Jose Estepar, PhD, James Ross, MSc, Mustafa Al Qaisi, MD, Jordan Zach, Alex Kluiber, Jered Sieren, Tanya Mann, Deanna Richert, Alexander McKenzie, Jaleh Akhavan, Douglas Stinson

PFT QA Core, LDS Hospital, Salt Lake City, UT: Robert Jensen, PhD

Biological Repository, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD: Homayoon Farzadegan, PhD, Stacey Meyerer, Shivam Chandan, Samantha Bragan

Data Coordinating Center and Biostatistics, National Jewish Health, Denver, CO: Douglas Everett, PhD, Andre Williams, PhD, Carla Wilson, MS, Anna Forssen, MS, Amber Powell, Joe Piccoli

Epidemiology Core, University of Colorado School of Public Health, Denver, CO: John Hokanson, MPH, PhD, Marci Sontag, PhD, Jennifer Black-Shinn, MPH, Gregory Kinney, MPH, PhDc, Sharon Lutz, MPH, PhD.

We further wish to acknowledge the COPDGene Investigators from the participating Clinical Centers:

Ann Arbor VA: Jeffrey Curtis, MD, Ella Kazerooni, MD

Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX: Nicola Hanania, MD, MS, Philip Alapat, MD, Venkata Bandi, MD, Kalpalatha Guntupalli, MD, Elizabeth Guy, MD, Antara Mallampalli, MD, Charles Trinh, MD, Mustafa Atik, MD, Hasan Al-Azzawi, MD, Marc Willis, DO, Susan Pinero, MD, Linda Fahr, MD, Arun Nachiappan, MD, Collin Bray, MD, L. Alexander Frigini, MD, Carlos Farinas, MD, David Katz, MD, Jose Freytes, MD, Anne Marie Marciel, MD

Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA: Dawn DeMeo, MD, MPH, Craig Hersh, MD, MPH, George Washko, MD, Francine Jacobson, MD, MPH, Hiroto Hatabu, MD, PhD, Peter Clarke, MD, Ritu Gill, MD, Andetta Hunsaker, MD, Beatrice Trotman-Dickenson, MBBS, Rachna Madan, MD

Columbia University, New York, NY: R. Graham Barr, MD, DrPH, Byron Thomashow, MD, John Austin, MD, Belinda D’Souza, MD

Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC: Neil MacIntyre, Jr., MD, Lacey Washington, MD, H Page McAdams, MD

Fallon Clinic, Worcester, MA: Richard Rosiello, MD, Timothy Bresnahan, MD, Joseph Bradley, MD, Sharon Kuong, MD, Steven Meller, MD, Suzanne Roland, MD

Health Partners Research Foundation, Minneapolis, MN: Charlene McEvoy, MD, MPH, Joseph Tashjian, MD

Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD: Robert Wise, MD, Nadia Hansel, MD, MPH, Robert Brown, MD, Gregory Diette, MD, Karen Horton, MD

Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA: Richard Casaburi, MD, Janos Porszasz, MD, PhD, Hans Fischer, MD, PhD, Matt Budoff, MD, Mehdi Rambod, MD

Michael E. DeBakey VAMC, Houston, TX: Amir Sharafkhaneh, MD, Charles Trinh, MD, Hirani Kamal, MD, Roham Darvishi, MD, Marc Willis, DO, Susan Pinero, MD, Linda Fahr, MD, Arun Nachiappan, MD, Collin Bray, MD, L. Alexander Frigini, MD, Carlos Farinas, MD, David Katz, MD, Jose Freytes, MD, Anne Marie Marciel, MD

Minneapolis VA: Dennis Niewoehner, MD, Quentin Anderson, MD, Kathryn Rice, MD, Audrey Caine, MD

Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA: Marilyn Foreman, MD, MS, Gloria Westney, MD, MS, Eugene Berkowitz, MD, PhD

National Jewish Health, Denver, CO: Russell Bowler, MD, PhD, David Lynch, MB, Joyce Schroeder, MD, Valerie Hale, MD, John Armstrong, II, MD, Debra Dyer, MD, Jonathan Chung, MD, Christian Cox, MD

Temple University, Philadelphia, PA: Gerard Criner, MD, Victor Kim, MD, Nathaniel Marchetti, DO, Aditi Satti, MD, A. James Mamary, MD, Robert Steiner, MD, Chandra Dass, MD, Libby Cone, MD

University of Alabama, Birmingham, AL: William Bailey, MD, Mark Dransfield, MD, Michael Wells, MD, Surya Bhatt, MD, Hrudaya Nath, MD, Satinder Singh, MD

University of California, San Diego, CA: Joe Ramsdell, MD, Paul Friedman, MD

University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA: Alejandro Cornellas, MD, John Newell, Jr., MD, Edwin JR van Beek, MD, PhD

University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI: Fernando Martinez, MD, MeiLan Han, MD, Ella Kazerooni, MD

University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN: Christine Wendt, MD, Tadashi Allen, MD

University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA: Frank Sciurba, MD, Joel Weissfeld, MD, MPH, Carl Fuhrman, MD, Jessica Bon, MD, Danielle Hooper, MD

University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX: Antonio Anzueto, MD, Sandra Adams, MD, Carlos Orozco, MD, Mario Ruiz, MD, Amy Mumbower, MD, Ariel Kruger, MD, Carlos Restrepo, MD, Michael Lane, MD

Footnotes

The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors; none of the above named entities participated in the design or conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or the preparation, review, approval, or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

References

- 1.Soriano JB, Davis KJ, Coleman B, Visick G, Mannino D, Pride NB. The proportional Venn diagram of obstructive lung disease: two approximations from the United States and the United Kingdom. Chest. 2003 Aug;124(2):474–81. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.2.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Marco R, Pesce G, Marcon A, Accordini S, Antonicelli L, Bugiani M, et al. The Coexistence of Asthma and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD): Prevalence and Risk Factors in Young, Middle-aged and Elderly People from the General Population. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e62985. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hardin M, Silverman EK, Barr RG, Hansel NN, Schroeder JD, Make BJ, et al. The clinical features of the overlap between COPD and asthma. Respir Res. 2011;12:127. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-12-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miravitlles M, Soler-Cataluna JJ, Calle M, Molina J, Almagro P, Quintano JA, et al. A new approach to grading and treating COPD based on clinical phenotypes: summary of the Spanish COPD guidelines (GesEPOC) Prim Care Respir J. 2013 Mar;22(1):117–21. doi: 10.4104/pcrj.2013.00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Donnell DE, Aaron S, Bourbeau J, Hernandez P, Marciniuk DD, Balter M, et al. Canadian Thoracic Society recommendations for management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease - 2007 update. Can Respir J. 2007 Sep;14( Suppl B):5B–32B. doi: 10.1155/2007/830570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nagai A. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: 3rd edition. Nihon Rinsho. 2011 Oct;69(10):1729–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyers DA, Larj MJ, Lange L. Genetics of asthma and COPD. Similar results for different phenotypes. Chest. 2004 Aug;126(2 Suppl):105S–10S. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.2_suppl_1.105S. discussion 59S–61S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Postma DS, Kerkhof M, Boezen HM, Koppelman GH. Asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: common genes, common environments? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011 Jun 15;183(12):1588–94. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201011-1796PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Regan EA, Hokanson JE, Murphy JR, Make B, Lynch DA, Beaty TH, et al. Genetic epidemiology of COPD (COPDGene) study design. COPD. 2010 Feb;7(1):32–43. doi: 10.3109/15412550903499522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005 Aug;26(2):319–38. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fedorov A, Beichel R, Kalpathy-Cramer J, Finet J, Fillion-Robin JC, Pujol S, et al. 3D Slicer as an image computing platform for the Quantitative Imaging Network. Magn Reson Imaging. 2012 Nov;30(9):1323–41. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakano Y, Wong JC, de Jong PA, Buzatu L, Nagao T, Coxson HO, et al. The prediction of small airway dimensions using computed tomography. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005 Jan 15;171(2):142–6. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200407-874OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim YI, Schroeder J, Lynch D, Newell J, Make B, Friedlander A, et al. Gender differences of airway dimensions in anatomically matched sites on CT in smokers. COPD. 2011 Aug;8(4):285–92. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2011.586658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Busacker A, Newell JD, Jr, Keefe T, Hoffman EA, Granroth JC, Castro M, et al. A multivariate analysis of risk factors for the air-trapping asthmatic phenotype as measured by quantitative CT analysis. Chest. 2009 Jan;135(1):48–56. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou X, Baron RM, Hardin M, Cho MH, Zielinski J, Hawrylkiewicz I, et al. Identification of a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease genetic determinant that regulates HHIP. Hum Mol Genet. 2012 Mar 15;21(6):1325–35. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howie B, Fuchsberger C, Stephens M, Marchini J, Abecasis GR. Fast and accurate genotype imputation in genome-wide association studies through pre-phasing. Nat Genet. 2012 Aug;44(8):955–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Y, Willer CJ, Ding J, Scheet P, Abecasis GR. MaCH: using sequence and genotype data to estimate haplotypes and unobserved genotypes. Genet Epidemiol. 2010 Dec;34(8):816–34. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Price AL, Patterson NJ, Plenge RM, Weinblatt ME, Shadick NA, Reich D. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2006 Aug;38(8):904–9. doi: 10.1038/ng1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007 Sep;81(3):559–75. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Willer CJ, Li Y, Abecasis GR. METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinformatics. 2010 Sep 1;26(17):2190–1. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson AD, Handsaker RE, Pulit SL, Nizzari MM, O’Donnell CJ, de Bakker PI. SNAP: a web-based tool for identification and annotation of proxy SNPs using HapMap. Bioinformatics. 2008 Dec 15;24(24):2938–9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moffatt MF, Gut IG, Demenais F, Strachan DP, Bouzigon E, Heath S, et al. A large-scale, consortium-based genomewide association study of asthma. N Engl J Med. 2010 Sep 23;363(13):1211–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Torgerson DG, Ampleford EJ, Chiu GY, Gauderman WJ, Gignoux CR, Graves PE, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies of asthma in ethnically diverse North American populations. Nat Genet. 2011 Sep;43(9):887–92. doi: 10.1038/ng.888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foreman MG, Campos M, Celedon JC. Genes and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Med Clin North Am. 2012 Jul;96(4):699–711. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kong X, Cho MH, Anderson W, Coxson HO, Muller N, Washko G, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies BICD1 as a susceptibility gene for emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011 Jan 1;183(1):43–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201004-0541OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hersh CP, Silverman EK, Gascon J, Bhattacharya S, Klanderman BJ, Litonjua AA, et al. SOX5 is a candidate gene for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease susceptibility and is necessary for lung development. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011 Jun 1;183(11):1482–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201010-1751OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Contoli M, Baraldo S, Marku B, Casolari P, Marwick JA, Turato G, et al. Fixed airflow obstruction due to asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: 5-year follow-up. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010 Apr;125(4):830–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hurst JR, Vestbo J, Anzueto A, Locantore N, Mullerova H, Tal-Singer R, et al. Susceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2010 Sep 16;363(12):1128–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Izquierdo-Alonso JL, Rodriguez-Gonzalezmoro JM, de Lucas-Ramos P, Unzueta I, Ribera X, Anton E, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of three clinical phenotypes of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) Respir Med. 2013 May;107(5):724–31. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chapman KR, Tashkin DP, Pye DJ. Gender bias in the diagnosis of COPD. Chest. 2001 Jun;119(6):1691–5. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.6.1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dransfield MT, Davis JJ, Gerald LB, Bailey WC. Racial and gender differences in susceptibility to tobacco smoke among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2006 Jun;100(6):1110–6. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2005.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chatila WM, Hoffman EA, Gaughan J, Robinswood GB, Criner GJ. Advanced emphysema in African-American and white patients: do differences exist? Chest. 2006 Jul;130(1):108–18. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Broekema M, ten Hacken NH, Volbeda F, Lodewijk ME, Hylkema MN, Postma DS, et al. Airway epithelial changes in smokers but not in ex-smokers with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009 Dec 15;180(12):1170–8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200906-0828OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fabbri LM, Romagnoli M, Corbetta L, Casoni G, Busljetic K, Turato G, et al. Differences in airway inflammation in patients with fixed airflow obstruction due to asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003 Feb 1;167(3):418–24. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200203-183OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Postma DS, Boezen HM. Rationale for the Dutch hypothesis. Allergy and airway hyperresponsiveness as genetic factors and their interaction with environment in the development of asthma and COPD. Chest. 2004 Aug;126(2 Suppl):96S–104S. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.2_suppl_1.96S. discussion 59S–61S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mogi C, Tobo M, Tomura H, Murata N, He XD, Sato K, et al. Involvement of proton-sensing TDAG8 in extracellular acidification-induced inhibition of proinflammatory cytokine production in peritoneal macrophages. J Immunol. 2009 Mar 1;182(5):3243–51. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kottyan LC, Collier AR, Cao KH, Niese KA, Hedgebeth M, Radu CG, et al. Eosinophil viability is increased by acidic pH in a cAMP- and GPR65-dependent manner. Blood. 2009 Sep 24;114(13):2774–82. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-220681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1: Regional association plots for top NHW GWAS results

Supplementary Figure 2: Regional association plots for top AA GWAS results

Supplementary Figure 3: Quantile-quantile plot for P values from meta-analysis

Supplementary Figure 4: Manhattan plot representing −log10 P values for meta-analysis results