Abstract

Cell sheet engineering has enabled the production of confluent cell sheets stacked together for use as a cardiac patch to increase cell survival rate and engraftment after transplantation, thereby providing a promising strategy for high density stem cell delivery for cardiac repair. One key challenge in using cell sheet technology is the difficulty of cell sheet handling due to its weak mechanical properties. A single-layer cell sheet is generally very fragile and tends to break or clump during harvest. Effective transfer and stacking methods are needed to move cell sheet technology into widespread clinical applications. In this study, we developed a simple and effective micropipette based method to aid cell sheet transfer and stacking. The cell viability after transfer was tested and multi-layer stem cell sheets were fabricated using the developed method. Furthermore, we examined the interactions between stacked stem cell sheets and fibrin matrix. Our results have shown that the preserved ECM associated with the detached cell sheet greatly facilitates its adherence to fibrin matrix and enhances the cell sheet-matrix interactions. Accelerated fibrin degradation caused by attached cell sheets was also observed.

Keywords: cell sheet, cell-matrix interactions, fibrin, mesenchymal stem cells

Introduction

Myocardial infarction (MI) is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in industrialized nations. It affects more than 10 million people in the United States and hundreds of millions worldwide.1 Various therapeutic strategies exist to treat MI.2,3 However, they do not restore normal heart function that has been lost as a result of dead myocardium. Cardiac cells have low proliferative potential and endogenous cells are unable to replenish dead heart cells. The cardiomyocyte deficit in patients with MI is in the order of one billion myocytes.4 Therefore, true cardiac repair would require restoring approximately one billion cardiomyocytes and ensuring their synchronous contraction via electromechanical junctions with host myocardium. Stem cells, which have the unique capability to differentiate into multiple lineages, could potentially regenerate lost myocardium and restore cardiac function. However, low cell viability and poor engraftment after transplantation has limited the therapeutic effects of stem cell-based cardiac therapy. Currently, only approximately 1–10% of stem cells remain in the heart 1–2 h after injection into the beating heart. More than 90% of injected cells migrate to other organs, and less than 10% of the transplanted cells are identified in the heart 4 wk after transplantation.5,6 In addition, injections of a large number of cells can cause cell clumping, microinfarction, and arrhythmogenic foci formation.7 The recently developed cell sheet engineering approach has enabled the production of confluent cell sheets stacked together for use as a cardiac patch to increase cell survival rate and engraftment after transplantation, providing a promising strategy for high density stem cell delivery.8,9

One key challenge in using cell sheet technology is the difficulty of cell sheet handling due to its weak mechanical properties. A single-layer cell sheet is generally very fragile and tends to break or clump during harvest. Effective transfer and stacking methods are needed to move cell sheet technology into widespread clinical applications. Currently, two main methods have been used to transfer cell sheets: using a sheet of PVDF membrane, or a hydrogel-coated, plunger-like manipulator.10 Most recently, a cell sheet transfer device has been developed, which has a scooping part to transfer cell sheets by a movable belt and a handling part to operate the device.11 However, all of these methods require applying a direct force on the cell sheet, which may affect cell viability, activities, long-term functions and cause variation between users.

In the present study, we developed a simple and effective micropipette based method to aid cell sheet transfer and stacking. The cell viability after transfer was tested and multi-layer stem cell sheets were fabricated using the developed method. Furthermore, we examined the interactions between stacked stem cell sheets and fibrin matrix. Fibrin, as a nature biomaterial, has been widely used in tissue engineering applications.12-14 When applied as a cardiac patch to treat MI, fibrin has been shown to provide temporary physical support of the infarct tissue and prevent negative left ventricular remodeling.15,16 The investigation on cell sheet-fibrin matrix interactions would provide valuable information on the feasibility of combining cell sheets and fibrin as a composite patch for cardiac repair.

Results and Discussion

Transfer and stacking of cell sheets using a micropipette method

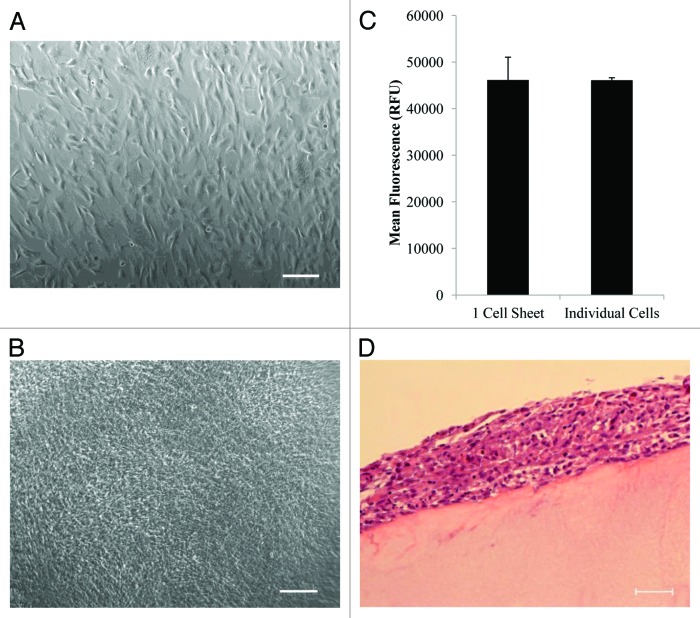

A simple and effective micropipette based method was developed to transfer and stack cell sheets. The mechanism of the developed method was illustrated in Figure 1. Human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) were cultured on a thermo-responsive surface fabricated using our newly developed spin coating technique.17 The detachment of hMSC sheets was achieved by replacing cell culture medium with fresh cold medium (4 °C). No residual cells were detected after cell sheet detachment. The detached floating cell sheet was collected by a modified micropipette tip (Fig. 1A) and transferred to other surfaces easily and rapidly (Fig. 1B). Cell viability testing was conducted and confirmed that no significant cell death was caused during the cell sheet transfer using the described micropipette method (Fig. 2A, B, and C). Moreover, the developed micropipette method allowed stacking of multi-layer cell sheets within the modified micropipette tip and transferring of the stacked cell sheets without any clumps and breakages (Fig. 1C). Confocal microscopy was used to show the successful stacking of triple layer hMSC sheets (Fig. 3) using the developed micropipette method. Multiple layer cell sheets were precisely transferred onto a fibrin gel surface, suggesting the manipulability of the method (Fig. 2D).

Figure 1. Micropipette Transfer Method. (A) The modified micropipette tip is fabricated by cutting the 1ml micropipette tip by the depicted configuration. (B) A cell sheet detached from the thermo-responsive surface is drawn into the modified micropipette tip along with media and dispensed to the desired location. (C) Multiple cell sheets can be transferred and stacked within the tip by drawing them into the tip, allowing them to settle to bottom of tip, and then dispensing on desired substrate.

Figure 2. Cell sheet transfer and cell viability. (A) The morphology of confluent hMSC monolayer growing on the thermoresponsive substrate prior to cell sheet detachment. (B) hMSC sheet morphology after transfer and attachment to the new cell culture substrate using the developed micropipette method. (C) Cell viability of single layer cell sheet after manipulation with a micropipette compared with the same amount of dissociated cells. No significant difference (P = 0.98) is identified between the two groups. (D) H&E staining of multi-layer hMSC sheets on fibrin matrix. Scale bar is 200µm for A and B and 50 µm for D.

Figure 3. Representative confocal images of 3-layer hMSC sheets. (A) Gallery image of sectional view showing the 3 layers of hMSC sheets. Cells at the top and bottom layers are labeled with AlexaFluor Phalloidin Green and cells at the middle layer are labeled with CellTracker Red CMTPX. (B) Cross section view. Scale bar is 100 µm for both A and B.

The developed micropipette method can aid cell sheet transfer and improve the efficiency of cell sheet stacking and transplantation. The modified tip used in our method was made from a universal 1ml micropipette tip and operated by a regular micropipette. They are available in most laboratories allowing the method to be readily adapted by many cell culture and tissue engineering researchers. Compared with other existing methods (e.g., using a PVDF membrane or a plunger-like manipulator), our method minimizes the force placed on the transferred cell sheet. A pipette-based method has been previously reported for transferring cell sheets, where a cell sheet was drawn into a 10-ml pipette and push-released onto another surface. The cell sheet tends to clump together in the pipette and needs to be flattened after transfer.10 When a cell sheet was transferred using our method, the modified micropipette tip collected the floating cell sheet and kept it flat within the tip. No re-spreading was needed after the cell sheet was transplanted onto the intended surface. Furthermore, continuous collecting and stacking of cell sheets is enabled using our method and could significantly increase the efficiency of cell sheet transfer. The method has been designed to collect and stack small sizes of cell sheets. It could be further modified to work with different sizes of cell sheets by using customized tips and modified operating devices.

Interactions between cell sheets and fibrin matrix

A single layer of hMSC sheet (~1.0 × 105 cells) was detached and transferred onto the surface of fibrin matrix to examine the cell-matrix interactions. The transferred cell sheet immediately attached to the fibrin matrix upon contact and formed a uniform cell layer on the matrix without any floating cell pieces. Fibrin matrices with different fibrinogen concentrations (5 mg/ml, 10 mg/ml, and 20 mg/ml) were used to test their effects on cell proliferation of the attached cell sheet. Our results indicated that cells within the cell sheet grew at different rates and proliferated significantly faster (P < 0.05) on the fibrin matrix with the final fibrinogen concentration of 10 mg/ml than on the other two fibrinogen concentrations (Fig. 4A). Much to our surprise, the cell sheet degraded most of the underneath fibrin matrix (10 mg/ml) 24 h after the initial seeding while no noticeable fibrin degradation was observed with the same number of dissociated cells under same culture conditions (Fig. 4B and C). We further tested the cell sheet and fibrin matrix interactions using stacked multi-layer cell sheets and thicker fibrin matrix. Accelerated fibrin degradation caused by the attached cell sheet was consistently observed (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4. Cell sheet and fibrin matrix interactions. (A) The effect of fibrinogen concentration on cell proliferation. Cell proliferation was measured using a PrestoBlue cell proliferation assay on the monolayer hMSC sheet 24 h after transferring to fibrin matrices with different fibrinogen concentrations. RFU is the fluorescent emission intensity of samples at 590nm when excited with 560nm light. Results are the means ± SD of 3 samples. Asterisk (*) indicates significant difference (P < 0.05). (B and C) H&E Staining of 4-layer hMSC sheets cultured on fibrin matrix for 1 d and 7 d, respectively. Scale bar is 50 µm (B) and 200µm (C).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first in vitro study demonstrating the enhanced cell-matrix interactions between hMSC sheets and fibrin matrix. One of the biggest advantages of using cell sheets detached by thermo-responsive surfaces is that it preserves cell-cell contacts and cell secreted extracellular matrix (ECM) during cell sheet transferring. Our results have shown that the preserved ECM associated with the detached cell sheet greatly facilitates its adherence to fibrin matrix. While it usually takes 2–6 h for dissociated hMSCs to fully attach to fibrin matrix, the attachment of cell sheet to fibrin matrix is instantaneous. When we stacked multiple layers of cell sheets within the modified micropipette tip as previously described and placed them on the fibrin matrix, effective bindings were found among the layers of cell sheets as well as between the cell sheets and fibrin matrix. The interactions of cell sheet and fibrin matrix are affected by the fibrinogen concentration of fibrin matrix. It has been extensively reported that the substrate stiffness plays an important role on directing cell behaviors.18,19 The stiffness of fibrin matrix is mostly determined by the fibrinogen concentration. Our previous studies have also elucidated that dissociated hMSCs prefer to grow on fibrin matrix with 10 mg/ml fibrinogen.15,20 As expected, hMSC sheets also showed the greatest proliferation rate on fibrin matrix with 10 mg/ml fibrinogen, indicating that cell culture methods (e.g., as individual cells or cell sheet) may not influence the preference for the culture substrate. The most profound finding of this study is the accelerated fibrin degradation caused by attached cell sheets. Compared with the same amount of dissociated cells, a hMSC sheet degrades fibrin matrix significantly faster. The mechanisms behind the accelerated fibrin degradation caused by cell sheet are still unknown. In future studies, we plan to examine whether the enhanced interactions between cell sheets and fibrin matrix are induced by the improved cell-cell communication enabled by the cell sheet technology.

Materials and Methods

Materials

poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAAm), MW 20–25 kg/mol, 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES), fibrinogen from human plasma, and thrombin from human plasma were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. Glass slides were purchased from Fisher Scientific. All other chemical reagents were purchased from Sigma Aldrich unless otherwise indicated.

Preparation of glass substrates

Glass slides were cut into squares with a surface area of ~1cm2. Slides were immersed in freshly prepared piranha solution (70 vol.% of concentrated H2SO4 and 30 vol.% of 30% H2O2) for 1 h at 100 °C to remove organic contaminants. After decanting the piranha solution, the slides were thoroughly rinsed with deionized (DI) water and dried with nitrogen (N2) gas. Afterwards, the slides were oxidized in a UV/Ozone Cleaner (Jelight Company Inc.) for 10 min for further cleaning.

Preparation of PNIPAAm/APTES solutions

A 3% wt. pNIPAAm solution and a 5% wt. APTES solution in ethanol (Pharmco-AAPER, Inc.) were prepared separately. Solutions having PNIPAAm to APTES ratios (by mass) of 80:20 were prepared by mixing the proper ratios of the two above solutions and a small amount of ethanol to make a final solution containing ~3 wt.% of total solute. The solutions were subsequently filtered to remove particulates through an Acrodisc® CR 13mm Syringe filter with a 0.45μm PTFE membrane (Pall Life Sciences, Co.).

Preparation of PNIPAAm/APTES films

Polymer blend films were produced by spin coating the PNIPAAm/APTES mixed solution onto pre-cleaned glass substrates for 30 s at 2000 rpm (p-6000 Spin Coater, Specialty Coating Systems, Inc.). The spin-coated samples were cured inside a vacuum (<100 mTorr) oven (VWR International) for 3 d at 160 °C. The glass slides were sterilized by placing under UV light (100–280 nm) for 20 min.

Fibrin Matrix Preparation

Fibrinogen (Sigma Aldrich) was dissolved in TBS at 37 °C to make a final concentration of 40mg/ml. The solution was filtered through a Steriflip 0.2 µm filter (Millipore). Using this solution and TBS, fibrinogen concentrations of 20 mg/ml and 10 mg/ml were also made. Thrombin was dissolved in sterile 40 mM CaCl2 to make a thrombin solution containing 25 units/ml.

Fibrin matrices were prepared by mixing 0.5ml of fibrinogen solution and 0.5 ml of thrombin solution to make fibrin matrices with the final fibrinogen concentrations of 5 mg/ml, 10 mg/ml, and 20 mg/ml. These fibrin matrices were allowed to fully crosslink for 1 h at room temperature. The matrices were washed twice with PBS to remove non-cross-linked solution from the matrix.

Cell seeding, detachment and manipulation from thermoresponsive substrates

Human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) (Lonza) were cultured in serum-containing MSCBM medium (Lonza) supplemented with MSCGM SingleQuots (Lonza) according to manufacturer’s specifications. hMSCs from passages 2–5 were used in the experiments. 1.0 × 105 cells were seeded on pre-warmed substrates for 24 h. After cells reached desired confluence and formed a cell monolayer on the PNIPAAm/APTES film, cell sheet detachment was induced by replacing warm cell culture medium with fresh cold medium (4 °C).

The detached cell sheet was then transferred to the desired location using a modified 1ml micropipette as shown in Figure 1. The floating cell sheet was drawn into the pipette tip and transferred to the desired location.

Cell proliferation

A PrestoBlue cell proliferation assay (Invitrogen) was performed to evaluate the efficiency of using the micropipette method to manipulate cell sheets by comparing 1 cell sheet comprised of 1.0 × 105 cells to 1.0 × 105 cells seeded on to a tissue culture plate. It was also used to compare the proliferative potential of cell sheets on fibrin matrices with fibrinogen concentrations of 5 mg/ml, 10 mg/ml, and 20 mg/ml. The PrestoBlue solution fluorescence was measured at an excitation wavelength of 560 nm and emission wavelength of 590 nm using a Synergy H1 Hybrid microplate reader (BioTek). For each group, 3 samples were tested.

Visualization of cell sheets

hMSC sheets were prepared as previously described and transferred onto fibrin matrices with the final fibrinogen concentration of 10 mg/ml using the developed micropipette method. After cultured for 1–7 d, the samples were fixed in 10% formalin. Fixed samples were dehydrated, paraffin embedded, sagittally sliced in 10µm sections using a microtome (Leica Microsystems), and placed on microscope slides. These slides were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) (Leica). Pictures of the sectioned gels were taken using an Axiovert A1 (Carl Zeiss, Inc.) microscope equipped with an AxioCam MRc camera (Carl Zeiss, Inc.).

Confocal microscopy was used to visualize the success of layering cell sheets on top of each other. hMSCs were labeled with CellTracker Red CMTPX (Invitrogen) prior to forming cell sheets using the thermoresponsive substrate. Non-labeled hMSCs were seeded on a microscope slide. A cell sheet labeled with CellTracker Red CMTPX was placed on top of the confluent cell layer on the microscope slide. After allowing 20 min of attachment, a 2nd cell sheet layer that was not labeled was placed on top of the labeled cell sheet. After allowing 2 h of full attachment of the cell layers the slide was fixed using 4% formaldehyde. Cells were permeabilized using Triton-X100 (Alfa Aesar) and stained with Alexa Fluor 488 Phalloidin (Invitrogen). Cell images were taken using an inverted microscope equipped with a Zeiss 510 META laser scanning module (Carl Zeiss).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.3. Data are reported as means ± standard deviations. All statistical comparisons were made by performing single factor analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Student-Newman-Keuls and Tukey comparisons tests. P values less than 0.05 are considered statistically significant.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Firestone Research Award to G.Z. We are grateful to Jocelyn Richmond at Akron General Hospital for providing help with histology analysis.

References

- 1.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, Bravata DM, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, et al. American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee Executive summary: heart disease and stroke statistics--2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:188–97. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182456d46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dominguez-Rodriguez A, Abreu-Gonzalez P, Reiter RJ. Cardioprotection and pharmacological therapies in acute myocardial infarction: Challenges in the current era. World J Cardiol. 2014;6:100–6. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v6.i3.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Topol EJ. Current status and future prospects for acute myocardial infarction therapy. Circulation. 2003;108(Suppl 1):III6–13. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000086950.37612.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caulfield JB, Leinbach R, Gold H. The relationship of myocardial infarct size and prognosis. Circulation. 1976;53(Suppl):I141–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hofmann M, Wollert KC, Meyer GP, Menke A, Arseniev L, Hertenstein B, Ganser A, Knapp WH, Drexler H. Monitoring of bone marrow cell homing into the infarcted human myocardium. Circulation. 2005;111:2198–202. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000163546.27639.AA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zeng L, Hu Q, Wang X, Mansoor A, Lee J, Feygin J, Zhang G, Suntharalingam P, Boozer S, Mhashilkar A, et al. Bioenergetic and functional consequences of bone marrow-derived multipotent progenitor cell transplantation in hearts with postinfarction left ventricular remodeling. Circulation. 2007;115:1866–75. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.659730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henning RJ. Stem cells in cardiac repair. Future Cardiol. 2011;7:99–117. doi: 10.2217/fca.10.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shimizu T, Sekine H, Yamato M, Okano T. Cell sheet-based myocardial tissue engineering: new hope for damaged heart rescue. Curr Pharm Des. 2009;15:2807–14. doi: 10.2174/138161209788923822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fedak PW. Cardiac progenitor cell sheet regenerates myocardium and renews hope for translation. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;87:8–9. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haraguchi Y, Shimizu T, Sasagawa T, Sekine H, Sakaguchi K, Kikuchi T, Sekine W, Sekiya S, Yamato M, Umezu M, et al. Fabrication of functional three-dimensional tissues by stacking cell sheets in vitro. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:850–8. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tadakuma K, Tanaka N, Haraguchi Y, Higashimori M, Kaneko M, Shimizu T, Yamato M, Okano T. A device for the rapid transfer/transplantation of living cell sheets with the absence of cell damage. Biomaterials. 2013;34:9018–25. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karp JM, Sarraf F, Shoichet MS, Davies JE. Fibrin-filled scaffolds for bone-tissue engineering: An in vivo study. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2004;71:162–71. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eyrich D, Göpferich A, Blunk T. Fibrin in tissue engineering. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2006;585:379–92. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-34133-0_24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shaikh FM, Callanan A, Kavanagh EG, Burke PE, Grace PA, McGloughlin TM. Fibrin: a natural biodegradable scaffold in vascular tissue engineering. Cells Tissues Organs. 2008;188:333–46. doi: 10.1159/000139772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang G, Wang X, Wang Z, Zhang J, Suggs L. A PEGylated fibrin patch for mesenchymal stem cell delivery. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:9–19. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiong Q, Hill KL, Li Q, Suntharalingam P, Mansoor A, Wang X, Jameel MN, Zhang P, Swingen C, Kaufman DS, et al. A fibrin patch-based enhanced delivery of human embryonic stem cell-derived vascular cell transplantation in a porcine model of postinfarction left ventricular remodeling. Stem Cells. 2011;29:367–75. doi: 10.1002/stem.580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel NG, Cavicchia JP, Zhang G, Zhang Newby BM. Rapid cell sheet detachment using spin-coated pNIPAAm films retained on surfaces by an aminopropyltriethoxysilane network. Acta Biomater. 2012;8:2559–67. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Discher DE, Janmey P, Wang YL. Tissue cells feel and respond to the stiffness of their substrate. Science. 2005;310:1139–43. doi: 10.1126/science.1116995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wells RG. The role of matrix stiffness in regulating cell behavior. Hepatology. 2008;47:1394–400. doi: 10.1002/hep.22193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang G, Drinnan CT, Geuss LR, Suggs LJ. Vascular differentiation of bone marrow stem cells is directed by a tunable three-dimensional matrix. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:3395–403. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]