Abstract

Summary: MoDPepInt (Modular Domain Peptide Interaction) is a new easy-to-use web server for the prediction of binding partners for modular protein domains. Currently, we offer models for SH2, SH3 and PDZ domains via the tools SH2PepInt, SH3PepInt and PDZPepInt, respectively. More specifically, our server offers predictions for 51 SH2 human domains and 69 SH3 human domains via single domain models, and predictions for 226 PDZ domains across several species, via 43 multidomain models. All models are based on support vector machines with different kernel functions ranging from polynomial, to Gaussian, to advanced graph kernels. In this way, we model non-linear interactions between amino acid residues. Results were validated on manually curated datasets achieving competitive performance against various state-of-the-art approaches.

Availability and implementation: The MoDPepInt server is available under the URL http://modpepint.informatik.uni-freiburg.de/

Contact: backofen@informatik.uni-freiburg.de

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Protein–protein interactions are often mediated by modular protein domains in eukaryotes and play an essential role in diverse biological processes such as signal transduction, cellular growth and cell polarity (Pawson and Nash, 2003). Modular domains that specifically bind with short linear peptides are known as peptide recognition modules. Each domain family recognizes peptides with specific characteristics. For example, phosphotyrosine (pY)-containing peptides, proline-rich peptides and C-terminus peptides are recognized by SH2, SH3 and PDZ domains, respectively. However, individual domains from the same family show different binding specificity. Accurate models that can help understand the mechanisms responsible for the highly selective binding affinity are therefore of interest. Recently, several high-throughput techniques, such as protein microarray, phage display and SPOT synthesis, have been developed, which can detect the binding specificity of various modular domains. However, efficient bioinformatics tools are needed to extract meaningful knowledge from the enormous amount of data produced.

To this end, we used state-of-the-art machine learning approaches to build support vector machine models that can accurately predict binding specificity. We have collected into a unified web-based system called MoDPepInt (Modular Domain Peptide Interaction), three different tools: SH2PepInt, SH3PepInt and PDZPepInt for three different modular domains, namely, SH2, SH3 and PDZ (Kundu et al., 2013a,b; Kundu and Backofen, 2014). Currently, we offer single domain models for 51 SH2 human and 69 SH3 human domains, and multidomain models for 226 PDZ domains across human, mouse, fly and worm. To assess the quality of our models, we have used manually curated interaction data achieving competitive performance against various state-of-the-art approaches.

In summary, MoDPepInt unique features include (i) a domain-peptide prediction system for SH2, SH3 and PDZ in a single platform and (ii) the largest number of modeled domains (see Supplementary Table S1).

2 APPLICATION AND FUNCTIONALITY

2.1 Input

All tools have a unified input format. Query sequences (up to a maximum number of 500) can be supplied either in a FASTA format or using UniProt database accession numbers. PDZPepInt offers predictions also for domains that are newly developed and/or not comprised in the original 226 PDZ domains: the unknown query domain should be supplied in FASTA format. Multiple query domain sequences can also be provided.

2.2 Filters

Several filters are available to increase predictive accuracy. SH2 domains generally recognize phosphotyrosine (pY) residues of binding proteins. For this reason, in SH2PepInt, we offer a phosphotyrosine filter that only considers those peptides whose tyrosine phosphorylation has already been experimentally verified and reported in PhosphoSitePlus database (Hornbeck et al., 2012).

As SH3 domains mainly bind with proline-rich peptides, in SH3PepInt, we offer a proline-rich filter that uses 31 regular expressions to select proline-rich peptides (Carducci et al., 2012).

PDZ domains have the tendency to bind the unstructured C-terminal regions of binding proteins; hence, in PDZPepInt, we offer a filter to select for intrinsically unstructured/disordered regions based on the IUPred algorithm (Dosztanyi et al., 2005), which selects five C-terminal residues with IUPred scores >0.4 (Akiva et al., 2012).

Finally, a cellular localization filter is available for all tools. This filter considers only those interactions where both the protein containing the peptide and the protein containing the modular domain have the same cellular localization according to the Gene Ontology Database (Ashburner et al., 2000).

2.3 Processing and output

An internal queuing system (which currently uses 40 computation nodes) balances the submitted jobs in parallel. MoDPepInt is implemented in C++, perl and shell scripting, with runtimes typically ranging in the order of few minutes.

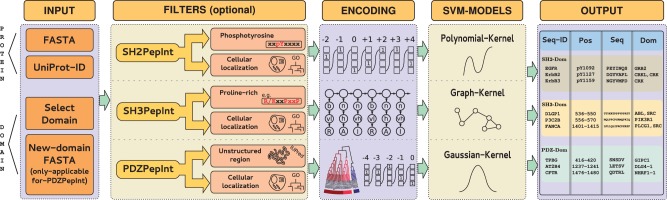

The output for all three tools is formatted as a downloadable table. We report for each domain–ligand protein interaction pair (i) the sequence ID, (ii) the ligand binding position, (iii) the ligand binding sequence and (iv) the ligand binding domains. See Figure 1 for the schematic representation of the MoDPepInt pipeline.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the MoDPepInt pipeline

3 DISCUSSION

MoDPepInt collects three protein–protein interaction predictive models that can be efficiently tuned using data derived from various high-throughput experimental techniques and thus do not require structural information as in Brannetti et al., 2000 and Hou et al., 2008, 2012. The resulting models exhibit significant performance improvement in comparison with other existing tools. The main sources of performance improvement are due to the following: (i) non-linear modeling and advantage over linear PWM models (Obenauer et al., 2003), (ii) balanced discriminative training and (iii) datasets pooling.

SH2PepInt uses polynomial kernels, and it is trained on additional high-confidence negatives obtained via semisupervised techniques.

SH3PepInt uses graph kernels on a complex representation of both the peptide sequence and the aligned domains. The adoption of a graph-type representation allows the inclusion of the physico-chemical properties of amino acids, which increases the generalization capacity of the models. Furthermore, the method does not need any prior alignment of the peptides. This is a big advantage because poly-proline-rich peptides are hard to align.

PDZPepInt uses Gaussian kernels, and it is trained on interaction data from additional highly related domains. Using pooling from closely related domains allows to leverage the limited information available for some domains and to extrapolate to unseen, but alignable, novel domains.

Once trained, all models can be used to efficiently scan entire proteomes to identify novel interactions with typical runtimes of few minutes.

In addition, we offer a meta-web server to be used in non-expert mode that submits the input simultaneously to all tools and displays a summary of the main results. For performance comparisons, details on the novelty of the methods and description of the meta-web server, see Supplementary Information.

Funding: This work was funded by the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (e-bio; FKZ 0316174A to R.B.) and the Excellent Initiative of the German Federal and State Governments (EXC 294 to R.B.).

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- Akiva E, et al. A dynamic view of domain-motif interactions. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2012;8:e1002341. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brannetti B, et al. SH3-SPOT: an algorithm to predict preferred ligands to different members of the SH3 gene family. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;298:313–328. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carducci M, et al. The protein interaction network mediated by human SH3 domains. Biotechnol. Adv. 2012;30:4–15. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosztanyi Z, et al. IUPred: web server for the prediction of intrinsically unstructured regions of proteins based on estimated energy content. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3433–3434. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornbeck PV, et al. PhosphoSitePlus: a comprehensive resource for investigating the structure and function of experimentally determined post-translational modifications in man and mouse. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D261–D270. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou T, et al. Characterization of domain-peptide interaction interface: a case study on the amphiphysin-1 SH3 domain. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;376:1201–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.12.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou T, et al. Characterization of domain-peptide interaction interface: prediction of SH3 domain-mediated protein-protein interaction network in yeast by generic structure-based models. J. Proteome Res. 2012;11:2982–2995. doi: 10.1021/pr3000688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundu K, et al. A graph kernel approach for alignment-free domain-peptide interaction prediction with an application to human SH3 domains. Bioinformatics. 2013a;29:i335–i343. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundu K, et al. Semi-supervised prediction of SH2-peptide interactions from imbalanced high-throughput data. PLoS One. 2013b;8:e62732. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundu K, Backofen R. Cluster based prediction of PDZ-peptide interactions. BMC Genomics. 2014;15(Suppl. 1):S5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-S1-S5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obenauer JC, et al. Scansite 2.0: proteome-wide prediction of cell signaling interactions using short sequence motifs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3635–3641. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson T, Nash P. Assembly of cell regulatory systems through protein interaction domains. Science. 2003;300:445–452. doi: 10.1126/science.1083653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.