Abstract

Endocarditis isolates of Enterococcus faecalis produced biofilm significantly more often than nonendocarditis isolates, and 39% of 79 versus 6% of 84 isolates produced strong biofilm (P < 0.0001). esp was not required, but its presence was associated with higher amounts of biofilm (P < 0.001). Mutants disrupted in dltA, efaA, ace, lsa, and six two-component regulatory systems were largely unaltered, while disruptions in epa, atn, gelE, and fsr resulted in fewer attached bacteria, as determined using phase-contrast microscopy, and less biofilm (P < 0.0001).

Bacteria are frequently found as part of a complex of organisms known as biofilm (15). Although biofilm formation by enterococci has been reported (1, 3, 28), there has not been a systematic study of endocarditis isolates and there has been little published relating to the genetics of biofilm formation by Enterococcus faecalis. This previous study found that 93.5% of esp-positive isolates formed biofilm while no esp-lacking isolate produced biofilm; esp disruption in two strains resulted in decreased biofilm formation, while esp disruption had no significant effect on the strong biofilm phenotype of a third strain (28). In the present work, we studied the occurrence of esp and biofilm formation among isolates of E. faecalis and evaluated mutants of an esp-lacking strain in an effort to unravel the role played by, and the genesis of, biofilm formation by this organism.

(Part of this work was presented at the 43rd Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, Chicago, Ill., 14 to 17 September 2003).

Bacterial strains.

A total of 163 E. faecalis isolates (51 from sources outside the United States) were evaluated. Control strains (28) were kindly provided by I. Lasa. OG1RF (esp negative) (12) and mutants of OG1RF that had been previously generated (14, 17, 18, 22-25, 27, 33) were also evaluated.

Genetic methods.

An intragenic fragment of esp was amplified by PCR using previously described primers (19) and used as a probe for colony hybridization, as described elsewhere (23). A disruption mutant (TX5427) of a homologue of Streptococcus agalactiae dltA was generated and confirmed, as described previously (27).

Biofilm formation.

Bacteria that had been grown overnight were diluted 1:100 in 200 μl of tryptic soy broth-0.25% glucose and inoculated onto polystyrene microtiter plates (Falcon, Franklin Lakes, N.J.). After 24 h of static incubation at 37°C, plates were processed (2, 28), fixed with Bouin's fixative for 30 min, stained with 1% crystal violet (CV) for 30 min, and rinsed with distilled water. CV was solubilized in ethanol-acetone (80:20, vol/vol), and optical density at 570 nm (OD570) was determined. Each assay was performed in quadruplicate on at least three occasions. For phase-contrast microscopy, bacteria were grown as described above except in polystyrene petri dishes (Falcon). After removal of planktonic bacteria, biofilm was directly examined by phase-contrast microscopy (magnification, ×600) with an Eclipse TE2000-E (Nikon Corp., Tokyo, Japan).

For primary adherence, 5 ml of a diluted overnight culture (OD600, 0.1) was added to polystyrene petri dishes (Falcon) and incubated for 2 h for mutants, as described previously (28), and 30 min for clinical isolates (5) (greater adherence of clinical isolates made counting difficult at 2 h). Bacteria in five different fields were subjected to light microscopy and counted (magnification, ×1,000) after Gram staining.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed using the Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables and Fisher's exact test (NCSS/PASS 2000 edition; NCSS Statistical Software, Kaysville, Utah) or the chi-square test for categorical variables. Median OD570 and interquartile range (IQR) values were calculated using GraphPad Prism 4 software.

Biofilm formation by clinical isolates.

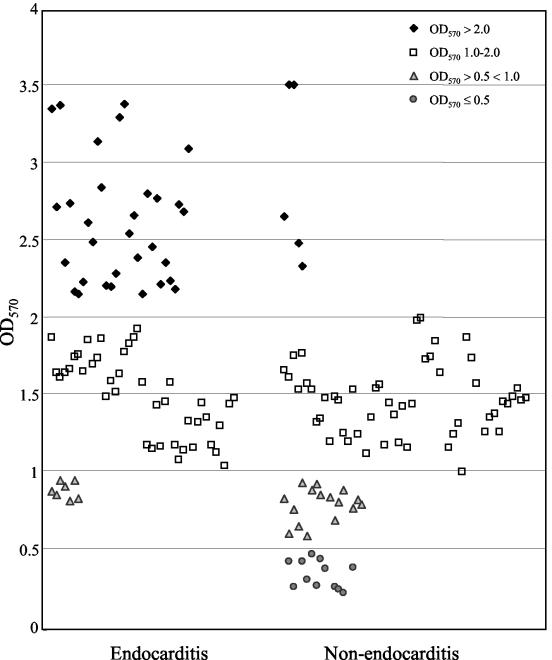

OD570 readings after CV staining ranged from 0.2 to 3.5 (Fig. 1), and isolates were categorized (Table 1) based on the approach of others (1, 10, 28) as strong (OD570, >2; 36 isolates [22%]), medium (OD570, 1 to 2; 92 isolates [56%]), or weak (OD570, greater than 0.5 but less than 1; 23 isolates [14%]) biofilm formers or as non-biofilm formers (OD570, ≤0.5; 12 isolates [7%]). The median OD570 values for controls (28) were 3.5 for E. faecalis strain 54 (categorized as a strong biofilm former in reference 28), 1.72 for strain 11279 (medium [28]), 0.85 for strain 11262 (weak [28]), and 0.61 for strain 23 (categorized as a non-biofilm former in reference 28). The ca. 93% of 163 E. faecalis isolates classified as biofilm producers is lower than the percentage reported in one study (20) that classified any samples with ODs of >0 as positive for biofilm formation and higher than that found by others (with slightly different methodologies) who reported 57% (28) and 80% (1) of E. faecalis isolates as positive for biofilm formation. If we consider only strong and medium production as positive (OD > 1.0), 78.5% of our isolates would be classified as biofilm formers (Table 1).

FIG. 1.

Biofilm formation by E. faecalis isolates derived from different sources. Biofilm formation on a polystyrene surface was assessed after CV staining. Each dot indicates the median OD570 value from 12 determinations (three independent experiments, each performed in quadruplicate). The medians (and IQRs) for endocarditis isolates and those from other sources were 1.74 (IQR, 1.32 to 2.35) and 1.31 (IQR, 0.82 to 1.53), respectively (P < 0.0001).

TABLE 1.

Occurrence of biofilm formation and presence of the esp gene in E. faecalis isolates

| Clinical sourceb (total no. tested) | No. (%) of isolates with indicated biofilm phenotypea/no. (%) of isolates which were also esp positive

|

% of total isolates that were esp positive | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strong | Medium | Strong or medium | Weak | Non-biofilm former | Weak or non- biofilm former | Positive for biofilm formation | ||

| Endocarditis (79) | 31 (39)/23 (74) | 41 (52)/14 (34) | 72 (91)/37 (51) | 7 (9)/1 (14) | 0 (0)/0 (0) | 7 (9)/1 (14) | 79 (100)/38 (48) | 48 |

| Urine (22) | 0 (0)/0 (0) | 17 (77)/12 (71) | 17 (77)/12 (71) | 3 (14)/1 (33) | 2 (9)/0 (0) | 5 (22)/1 (20) | 20 (91)/13 (65) | 59 |

| Otherc (31) | 2 (7)/0 (0) | 17 (55)/12 (71) | 19 (61)/12 (71) | 6 (19)/3 (50) | 6 (19)/0 (0) | 12 (39)/3 (25) | 25 (81)/15 (60) | 48 |

| Hospital fecal specimens (15) | 1 (7)/1 (100) | 7 (47)/2 (29) | 8 (53)/3 (38) | 4 (27)/2 (50) | 3 (20)/0 (0) | 7 (47)/2 (29) | 12 (80)/5 (42) | 33 |

| Community fecal specimens (16) | 2 (13)/1 (50) | 10 (63)/2 (20) | 12 (75)/3 (25) | 3 (19)/0 (0) | 1 (6)/0 (0) | 4 (25)/0 (0) | 15 (94)/3 (20) | 19 |

| Total (163) | 36 (22.1)/25 (69)d | 92 (56.4)/42 (46)d | 128 (78.5)/67 (52) | 23 (14.1)/7 (30)d | 12 (7.4)/0 (0)d | 35 (21.5)/7 (20) | 151 (92.6)/74 (49) | 45 |

Strong, OD570 of >2 (median, 2.57; IQR, 2.25 to 2.81); medium, OD570 of 1 to 2 (median, 1.47; IQR, 1.27 to 1.64); weak, OD570 of greater than 0.5 but less than 1 (median, 0.82; IQR, 0.76 to 0.88); non-biofilm former, OD570 of ≤0.5 (median, 0.33; IQR, 0.25 to 0.41).

Median ODs were 1.74 (IQR, 1.32 to 2.35) for endocarditis isolates, 1.39 (IQR, 1.01 to 1.55) for isolates from urine, 1.18 (IQR, 0.64 to 1.64) for other clinical isolates, 0.99 (IQR, 0.68 to 1.57) for hospital fecal isolates, and 1.40 (IQR, 1.03 to 1.48) for community fecal isolates (P, ≤ 0.005 for endocarditis isolates versus each of the other groups of isolates).

Other clinical isolates were derived from ascites fluid, blood, catheters, cerebrospinal fluid, cervix, endometrium, penis, placenta, trachea, and wounds.

P, < 0.001 for correlation between percentage of esp-positive isolates and strong, medium, weak, or no biofilm production (median ODs, 1.62 [IQR, 1.25 to 2.29] for esp-positive isolates and 1.37 [IQR, 0.85 to 1.71] for esp-negative isolates; P < 0.001).

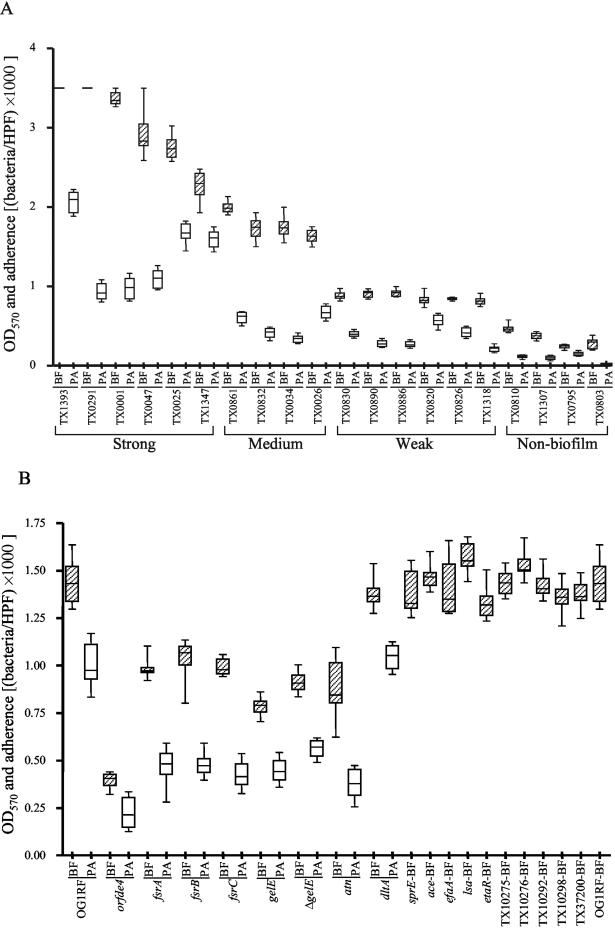

All 79 endocarditis isolates formed biofilm versus 86% of 84 isolates from other sources (P < 0.001), and 31 of 79 (39%) were strong biofilm formers (Table 1 and Fig. 1) versus only 5 (6%) of the isolates from other sources (P < 0.0001; median OD570, 1.74 versus 1.31; P < 0.0001). To our knowledge, this is the first report to show that endocarditis isolates are associated with greater biofilm formation, but it would be premature to speculate whether biofilm contributes to or perhaps results from endocarditis. Results for primary adherence were generally, but not absolutely (e.g., TX0034 and TX0291), correlated with an organism's level of biofilm formation (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

Biofilm formation (BF) and primary adherence (PA) by representative E. faecalis clinical isolates (A) and mutants (B). Median and IQR values are shown. Values for the biofilm assays are from 12 determinations (three independent experiments, each performed in quadruplicate). All readings for TX1393 and TX0291 were 3.5, the maximum OD detectable by our microplate reader. Primary adherence was assessed after incubation on a polystyrene surface for 30 min for clinical isolates and 2 h for mutants. Bacteria in five different fields from two independent plates were subjected to light microscopy (HPF, high-power field; magnification, ×1,000) and counted after Gram staining. TX10275, TX10276, TX10292, TX10298, TX37200, and etaR are two-component regulatory system mutants. The other 10 mutants which showed no change in biofilm were not tested for primary adherence.

Presence of esp and biofilm.

esp was present in 74 (45%) of 163 isolates and 49% of biofilm producers (Table 1). Among endocarditis isolates, 48% were esp positive versus 59% of urine isolates, 48% of other clinical isolates, 33% of nosocomial fecal isolates, and 19% of community fecal isolates. The incidence of esp has been reported by others as 29 to 45% among E. faecalis blood isolates (4, 21, 29, 31), 42% among 33 endocarditis isolates (21), and 3 to 40% among fecal isolates (21, 31).

All 74 esp-positive isolates produced biofilm, and 77 of 89 esp-negative isolates also produced biofilm. This is in contrast to results from one study (28) in which none of the esp-negative isolates formed biofilm, but it is consistent with those of another study (20) reporting no association between esp and biofilm formation. However, we did find that 69% of strong, 46% of medium, and 30% of weak biofilm producers and 0 of 12 non-biofilm producers were esp positive (P < 0.001) and that there was a significant difference in median OD values (P < 0.001) (Table 1), indicating a strong association between the presence of esp and greater levels of biofilm production.

Analysis of E. faecalis OG1RF mutants.

The absence of esp in 51% of biofilm formers motivated us to look for other genes that might influence biofilm formation. Among mutants of E. faecalis OG1RF (an esp-negative medium biofilm former) that were previously generated, seven were defective in biofilm formation (P, <0.0001 for each mutant) compared to OG1RF (Fig. 2B). In particular, our epa (enterococcal polysaccharide antigen) gene cluster mutant, TX5179 (orfde4) (26, 33), showed ∼73% reduction in biofilm formation, suggesting that this gene (encoding a putative glycosyltransferase, often involved in polysaccharide synthesis) (32, 33) and/or the cotranscribed orfde5 is important for biofilm formation. We have no evidence to indicate a surface location for Epa (33) or a direct role of the Epa polysaccharide in attachment or biofilm accumulation, and there may be other effects, such as alteration of the overall cell wall layer, as suggested by others (7).

All three of our fsr mutants (17) also showed decreased biofilm formation, with reduction ranging from ∼28 to 32% relative to that by OG1RF (Fig. 2B); fsr, a homologue of staphylococcal agr loci, positively regulates expression of gelatinase (GelE) and serine protease (SprE) genes and is involved in quorum sensing (13, 16, 17). This decrease was not as great as the 46% decrease seen for TX5128, a gelE insertion mutant (GelE− SprE−) (24) (P < 0.0001) or for TX5264, a nonpolar gelE deletion mutant (GelE− SprE+) (22) (P < 0.01) (Fig. 2B). A recent study also demonstrated that GelE enhances biofilm formation by E. faecalis (9). Since the fsr mutants also have the GelE− SprE− phenotype, it is possible that biofilm reduction is due to loss of protease production. Biofilm formation by an agr mutant of Staphylococcus aureus (30) was enhanced compared to that by the wild type, in contrast to our results with fsr mutants; however, the fsr mutants formed slightly (but significantly) more biofilm than the gelatinase mutants, suggesting an additional effect(s) of fsr which influences biofilm formation in the same direction as agr. Future studies will be needed to address what additional role fsr may have on biofilm production. We also examined a gelE in-frame-deletion mutant and TX5243, a sprE insertion mutant (GelE+ SprE−) (17); the sprE mutant formed as much biofilm as the wild type, while the gelE insertion (Gel− SprE−) and deletion (Gel− SprE+) mutants showed decreased biofilm formation (Fig. 2B), indicating that gelatinase rather than the serine protease is important for biofilm formation.

Our autolysin (atn) mutant, TX5127, previously shown to display increased chaining and decreased autolysis (18), showed ∼39% reduction in biofilm formation (Fig. 2B). A similar finding was seen in a Lactococcus lactis autolysin (acmA) mutant, which exhibited long chains of cells, adhered less efficiently than the wild type, and was unable to form biofilm (11). A Staphylococcus epidermidis autolysin (atlE) mutant also showed decreased primary attachment to polystyrene (8).

Among the previously described two-component regulatory system mutants (27), five were unaltered in biofilm formation, although the etaR mutant (TX10293) showed a small (∼8%) but significant (P < 0.02) reduction in biofilm (Fig. 2B). Mutants TX5132 (efaA, encoding an E. faecalis antigen A) (23) and TX5256 (ace, encoding a collagen adhesin) (14) were also unchanged relative to OG1RF, while TX5332 (lsa, encoding an ATP-binding cassette transporter required for lincosamide and streptogramin A resistance) (25) showed a small (∼9%) but significant (P < 0.02) increase (Fig. 2B). Biofilm formation by TX5427 (this study) disrupted in a dltA homologue was approximately equal to that by OG1RF, unlike that by an S. aureus dlt mutant (6).

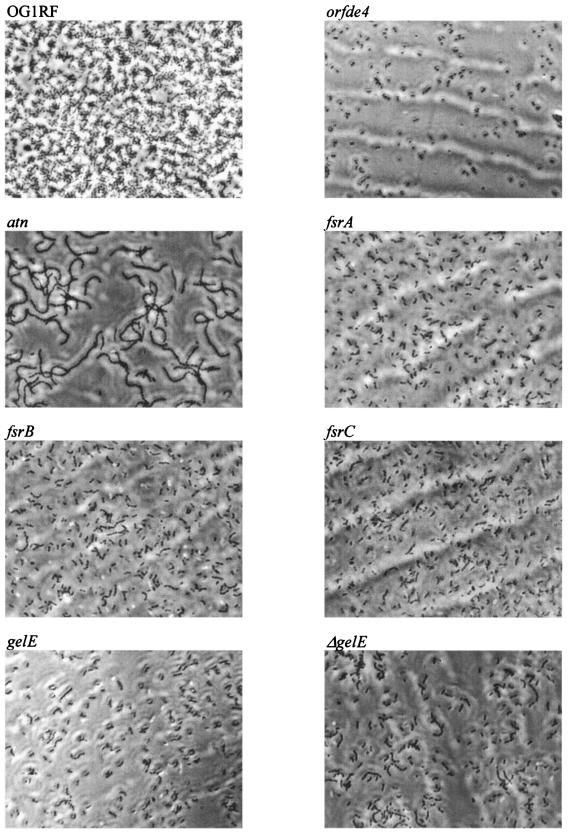

In a primary attachment assay, OG1RF attached to polystyrene more efficiently than the seven mutants with reduced biofilm formation (P, <0.001 for each mutant) (Fig. 2B). As determined by phase-contrast microscopy, OG1RF formed a more confluent layer, with dark clusters of bacteria in microcolonies interspaced with areas of less densely packed bacteria, whereas these seven mutants showed fewer attached bacteria without microcolonies (Fig. 3). This indicates that epa, atn, gelE, and the fsr locus influence primary attachment, although additional effects on biofilm accumulation are also possible. The atn mutant was again (18) noted to exhibit long chains of cells whereas mutants disrupted in gelE, fsrA, fsrB, and fsrC showed short chains and the orfde4 mutant showed no chain formation (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Phase-contrast photomicrographs of biofilms on a polystyrene surface. Images are representative of what was observed in multiple fields (magnification, ×600).

In conclusion, our results agree with other reports that biofilm formation is very common among E. faecalis clinical as well as fecal isolates. We also found that the percent and degree of biofilm formation are significantly greater among endocarditis isolates than among isolates from other sources. Although esp was not required for biofilm formation, its presence showed a significant association with the degree of biofilm production. Our study also identified several other genes that influenced primary attachment and biofilm formation by E. faecalis OG1RF.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R37 AI47923 to B.E.M. from the Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

We thank I. Lasa for sending control strains for biofilm production and Chul W. Ahn for his assistance with statistics.

Editor: F. C. Fang

REFERENCES

- 1.Baldassarri, L., R. Cecchini, L. Bertuccini, M. G. Ammendolia, F. Iosi, C. R. Arciola, L. Montanaro, R. Di Rosa, G. Gherardi, G. Dicuonzo, G. Orefici, and R. Creti. 2001. Enterococcus sp. produces slime and survives in rat peritoneal macrophages. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. (Berlin) 190:113-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christensen, G. D., W. A. Simpson, J. J. Younger, L. M. Baddour, F. F. Barrett, D. M. Melton, and E. H. Beachey. 1985. Adherence of coagulase-negative staphylococci to plastic tissue culture plates: a quantitative model for the adherence of staphylococci to medical devices. J. Clin. Microbiol. 22:996-1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Distel, J. W., J. F. Hatton, and M. J. Gillespie. 2002. Biofilm formation in medicated root canals. J. Endod. 28:689-693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eaton, T. J., and M. J. Gasson. 2001. Molecular screening of Enterococcus virulence determinants and potential for genetic exchange between food and medical isolates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:1628-1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fournier, B., and D. C. Hooper. 2000. A new two-component regulatory system involved in adhesion, autolysis, and extracellular proteolytic activity of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 182:3955-3964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gross, M., S. E. Cramton, F. Gotz, and A. Peschel. 2001. Key role of teichoic acid net charge in Staphylococcus aureus colonization of artificial surfaces. Infect. Immun. 69:3423-3426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hancock, L. E., and M. S. Gilmore. 2002. The capsular polysaccharide of Enterococcus faecalis and its relationship to other polysaccharides in the cell wall. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:1574-1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heilmann, C., M. Hussain, G. Peters, and F. Gotz. 1997. Evidence for autolysin-mediated primary attachment of Staphylococcus epidermidis to a polystyrene surface. Mol. Microbiol. 24:1013-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kristich, C. J., Y. H. Li, D. G. Cvitkovitch, and G. M. Dunny. 2004. Esp-independent biofilm formation by Enterococcus faecalis. J. Bacteriol. 186:154-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loo, C. Y., D. A. Corliss, and N. Ganeshkumar. 2000. Streptococcus gordonii biofilm formation: identification of genes that code for biofilm phenotypes. J. Bacteriol. 182:1374-1382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mercier, C., C. Durrieu, R. Briandet, E. Domakova, J. Tremblay, G. Buist, and S. Kulakauskas. 2002. Positive role of peptidoglycan breaks in lactococcal biofilm formation. Mol. Microbiol. 46:235-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murray, B. E., K. V. Singh, R. P. Ross, J. D. Heath, G. M. Dunny, and G. M. Weinstock. 1993. Generation of restriction map of Enterococcus faecalis OG1 and investigation of growth requirements and regions encoding biosynthetic function. J. Bacteriol. 175:5216-5223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakayama, J., Y. Cao, T. Horii, S. Sakuda, A. D. Akkermans, W. M. de Vos, and H. Nagasawa. 2001. Gelatinase biosynthesis-activating pheromone: a peptide lactone that mediates a quorum sensing in Enterococcus faecalis. Mol. Microbiol. 41:145-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nallapareddy, S. R., X. Qin, G. M. Weinstock, M. Hook, and B. E. Murray. 2000. Enterococcus faecalis adhesin, Ace, mediates attachment to extracellular matrix proteins collagen type IV and laminin as well as collagen type I. Infect. Immun. 68:5218-5224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O'Toole, G., H. B. Kaplan, and R. Kolter. 2000. Biofilm formation as microbial development. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:49-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qin, X., K. V. Singh, G. M. Weinstock, and B. E. Murray. 2001. Characterization of fsr, a regulator controlling expression of gelatinase and serine protease in Enterococcus faecalis OG1RF. J. Bacteriol. 183:3372-3382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qin, X., K. V. Singh, G. M. Weinstock, and B. E. Murray. 2000. Effects of Enterococcus faecalis fsr genes on production of gelatinase and a serine protease and virulence. Infect. Immun. 68:2579-2586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qin, X., K. V. Singh, Y. Xu, G. M. Weinstock, and B. E. Murray. 1998. Effect of disruption of a gene encoding an autolysin of Enterococcus faecalis OG1RF. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2883-2888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rice, L. B., L. Carias, S. Rudin, C. Vael, H. Goossens, C. Konstabel, I. Klare, S. R. Nallapareddy, W. Huang, and B. E. Murray. 2003. A potential virulence gene, hylEfm, predominates in Enterococcus faecium of clinical origin. J. Infect. Dis. 187:508-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sandoe, J. A., I. R. Witherden, J. H. Cove, J. Heritage, and M. H. Wilcox. 2003. Correlation between enterococcal biofilm formation in vitro and medical-device-related infection potential in vivo. J. Med. Microbiol. 52:547-550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shankar, V., A. S. Baghdayan, M. M. Huycke, G. Lindahl, and M. S. Gilmore. 1999. Infection-derived Enterococcus faecalis strains are enriched in esp, a gene encoding a novel surface protein. Infect. Immun. 67:193-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sifri, C. D., E. Mylonakis, K. V. Singh, X. Qin, D. A. Garsin, B. E. Murray, F. M. Ausubel, and S. B. Calderwood. 2002. Virulence effect of Enterococcus faecalis protease genes and the quorum-sensing locus fsr in Caenorhabditis elegans and mice. Infect. Immun. 70:5647-5650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh, K. V., T. M. Coque, G. M. Weinstock, and B. E. Murray. 1998. In vivo testing of an Enterococcus faecalis efaA mutant and use of efaA homologs for species identification. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 21:323-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singh, K. V., X. Qin, G. M. Weinstock, and B. E. Murray. 1998. Generation and testing of mutants of Enterococcus faecalis in a mouse peritonitis model. J. Infect. Dis. 178:1416-1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh, K. V., G. M. Weinstock, and B. E. Murray. 2002. An Enterococcus faecalis ABC homologue (Lsa) is required for the resistance of this species to clindamycin and quinupristin-dalfopristin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1845-1850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teng, F., K. D. Jacques-Palaz, G. M. Weinstock, and B. E. Murray. 2002. Evidence that the enterococcal polysaccharide antigen gene (epa) cluster is widespread in Enterococcus faecalis and influences resistance to phagocytic killing of E. faecalis. Infect. Immun. 70:2010-2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teng, F., L. Wang, K. V. Singh, B. E. Murray, and G. M. Weinstock. 2002. Involvement of PhoP-PhoS homologs in Enterococcus faecalis virulence. Infect. Immun. 70:1991-1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Toledo-Arana, A., J. Valle, C. Solano, M. J. Arrizubieta, C. Cucarella, M. Lamata, B. Amorena, J. Leiva, J. R. Penades, and I. Lasa. 2001. The enterococcal surface protein, Esp, is involved in Enterococcus faecalis biofilm formation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4538-4545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vergis, E. N., N. Shankar, J. W. Chow, M. K. Hayden, D. R. Snydman, M. J. Zervos, P. K. Linden, M. M. Wagener, and R. R. Muder. 2002. Association between the presence of enterococcal virulence factors gelatinase, hemolysin, and enterococcal surface protein and mortality among patients with bacteremia due to Enterococcus faecalis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 35:570-575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vuong, C., H. L. Saenz, F. Gotz, and M. Otto. 2000. Impact of the agr quorum-sensing system on adherence to polystyrene in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Infect. Dis. 182:1688-1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Waar, K., A. B. Muscholl-Silberhorn, R. J. Willems, M. J. Slooff, H. J. Harmsen, and J. E. Degener. 2002. Genogrouping and incidence of virulence factors of Enterococcus faecalis in liver transplant patients differ from blood culture and fecal isolates. J. Infect. Dis. 185:1121-1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu, Y., B. E. Murray, and G. M. Weinstock. 1998. A cluster of genes involved in polysaccharide biosynthesis from Enterococcus faecalis OG1RF. Infect. Immun. 66:4313-4323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu, Y., K. V. Singh, X. Qin, B. E. Murray, and G. M. Weinstock. 2000. Analysis of a gene cluster of Enterococcus faecalis involved in polysaccharide biosynthesis. Infect. Immun. 68:815-823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]