Abstract

The Fli-1 transcription factor, an Ets family member, is implicated in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in human patients and murine models of lupus. Lupus-prone mice with reduced Fli-1 expression have significantly less nephritis, prolonged survival and decreased infiltrating inflammatory cells into the kidney. Inflammatory chemokines, including CCL5, are critical for attracting inflammatory cells. In this study, decreased CCL5 mRNA expression was observed in kidneys of lupus prone NZM2410 mice, with reduced Fli-1 expression. CCL5 protein expression was significantly decreased in endothelial cells transfected with Fli-1 specific siRNA compared to controls. Fli-1 binds to endogenous Ets binding sites in the distal region of the CCL5 promoter. Transient transfection assays demonstrate that Fli-1 drives transcription from the CCL5 promoter in a dose-dependent manner. Both Ets1, another Ets family member, and Fli-1 drive transcription from the CCL5 promoter, although Fli-1 transactivation was significantly stronger. Ets1 acts as a dominant negative transcription factor to Fli-1, indicating that they may have at least one DNA binding site in common. Systematic deletion of DNA binding sites demonstrates the importance of the sites located within a 225bp region of the promoter. Mutation of the Fli-1 DNA binding domain significantly reduces transactivation of the CCL5 promoter by Fli-1. We have identified a novel regulator of transcription for CCL5. These results suggest that Fli-1 is a novel and critical regulator of proinflammatory chemokines and affects the pathogenesis of disease through the regulation of factors that recruit inflammatory cells to sites of inflammation.

Introduction

Inflammatory cytokines and chemokines are important regulators of the immune system and actively recruit inflammatory cells to sites of inflammation. CCL5 also known as RANTES (Regulated upon Activation, Normal T Expressed and Secreted), a member of the C-C chemokine family of inflammatory cytokines (1, 2), was originally thought to be T-cell specific since it was cloned from a cDNA library enriched for T-cell specific sequences and mRNA expression was found only in cytotoxic and helper T cell lines (3). However, the expression of CCL5 has since been observed in a variety of cell types including T cells (1, 3), endothelial (4), renal tubular epithelial (5), and mesangial cells (6), fibroblasts and macrophages (7, 8). The CCL5 gene consists of a 23 amino acid leader peptide followed by 68 residues, 4 of them cysteines, and lacks a transmembrane domain (1, 3). The murine CCL5 gene was first isolated from renal tubular epithelial cells and is 90% homologous to the human gene (5). Analysis of the human CCL5 promoter region, approximately 1kb in length, identified a wide variety of transcription factor binding sites including NFkB, AP-1, C/EBP, and at least one Ets-1 binding site. Deletion studies of the promoter demonstrated that different transcriptional mechanisms may control CCL5 in different tissue and cell types (1). CCL5 gene expression is stimulated by LPS, TNFα, INFγ, and IL-1β (4–11). Within the murine CCL5 promoter, one NFkB and one IRF binding site are responsible for stimulation of the promoter by TNFα and INFγ and activation is regulated by the p65 subunit of NFkB and IRF1 respectively (8, 9). Studies aimed at understanding the transcription factors that regulate the CCL5 promoter have been performed and many transcription factors have been identified. The Ets family member PU.1 has been shown to bind to the CCL5 promoter and may be involved in the recruitment of other transcription factors (11, 12). Increased binding to the CCL5 promoter by NFkB, AP-1, and C/EBP was observed in glomeruli after stimulation with LPS (10). LPS induction of the human CCL5 gene was found to be mediated by the transcription factors ATF and Jun, through a CRE/AP-1 binding site (11). Another transcription factor, KLF13, has been shown to bind to the CCL5 promoter and binding is a requirement for transactivation and synergistic activation with NFkB proteins (13, 14).

CCL5 plays a role in the pathogenesis of a variety of inflammatory mediated diseases including asthma (15, 16), rheumatoid arthritis (7), and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (17, 18) by actively recruiting leukocytes, macrophages and eosinophils (15, 16, 19, 20) to sites of inflammation. A variety of renal diseases have been linked to the CCL5 gene (21) and its’ expression has been documented in the kidney cortex, glomerulus, and renal tubular epithelial cells (5, 6, 10, 20, 22–24). Analysis of microarray data from glomerular gene expression in MRL/lpr mice, a murine model of lupus, with active lupus nephritis demonstrated a profound up-regulation of CCL5 mRNA (24). In MRL/lpr mice, CCL5 gene expression increased with disease progression and promoted renal injury through the recruitment of macrophages, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells to the kidney, particularly the area surrounding the glomeruli (20). A mouse model that exhibits autoimmune nephrotoxic serum nephritis was shown to have increased CCL5 mRNA expression in diseased mice, whereas proteinuria was decreased in CCL5 deficient mice and milder versions of glomerulonephritis observed (22). Increased CCL5 expression has been detected in the serum of patients with SLE, although correlation with patients’ SLEDAI (SLE disease activity index) scores appears to depend on further classification of the disease (17, 18). Additionally, it was found that in patients with primary glomerulonephritis, measurement of the urinary excretion of IL-1ra, TNF-R1 and 2, and CCL5 together, could predict a favorable response of patients to immunosuppressive therapy (25).

The friend leukemia insertion site 1 (Fli-1) gene is a member of the Ets family of transcription factors who regulate a variety of cellular processes including the immune response (26–28). Ets family members recognize the consensus DNA binding motif GGAA/T and bind the DNA through a winged helix turn helix domain (27, 29, 30). Ets transcription factors can be both positive and negative regulators of transcription and interactions with other transcription factors can lead to increased DNA binding ability and synergistic activation or repression (27, 31). Several studies have demonstrated a role for Fli-1 in the pathogenesis of renal injury and the autoimmune disease SLE (32–37). Transgenic mice that overexpressed the Fli-1 gene exhibited an increase in infiltrating B and T lymphocytes and eventually die from tubulointerstitial nephritis and glomerulonephritis (38), whereas, murine models of lupus with heterozygous expression of Fli-1 had a reduction in renal inflammation, necrosis, proteinuria, and autoantibody production and prolonged survival (34, 35, 37). In addition, Fli-1 heterozygous lupus-prone mice displayed a significant decrease in the infiltration of inflammatory cells to the kidney and the expression of another proinflammatory chemokine CCL2/MCP-1 was dramatically reduced (39).

Since Ets DNA binding domains have been identified in the CCL5 promoter (1, 11, 27), CCL5 plays a role in attracting inflammatory cells, and murine models of lupus with reduced expression of Fli-1 have significantly reduced nephritis with markedly decreased inflammatory cell infiltration, the present study was conceived to determine if Fli-1 is involved in the regulation of CCL5 gene expression. We discovered decreased CCL5 mRNA expression in kidneys of Fli-1 heterozygous NZM2410 mice, prior to the onset of disease. CCL5 protein levels were also decreased in MS1 endothelial cells stimulated with LPS after knockdown of Fli-1 with siRNA. ChIP assays demonstrated that Fli-1 binds to Ets binding sites in the distal region of the CCL5 promoter and transient transfection assays showed that Fli-1 drives transcription from the promoter. Taken together, our results indicate that the Fli-1 transcription factor plays a previously undiscovered role in the transcriptional control of the CCL5 gene and a reduction in the expression of Fli-1 leads to a decrease in CCL5 gene expression both in vitro and in vivo. Combined with our previous studies, it appears that Fli-1 plays a critical role in the transactivation of inflammatory chemokines, which affects the development of glomerulonephritis and the pathogenesis of kidney disease in SLE.

Materials and Methods

Mice

The NZM2410 mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). The heterozygous (Fli-1+/−) NZM2410 mice and wild-type (WT) littermates (Fli-1+/+ NZM2410 mice) were generated by backcrossing with Fli-1+/− B6 mice for 12 generations as described previously (35). All mice were housed under pathogen-free conditions at the animal facility of the Ralph H. Johnson Veterans Affairs Medical Center, and all animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Genotyping

PCR was used to detect fragments of the WT and Fli-1+/− alleles as previously described (34). Briefly, the following primers were used in the PCR: Fli-1 exon IX forward primer (positions 1156 to 1180), 5′-GACCAACGGGGAGTTCAAAATGACG-3′; Fli-1 exon IX/reverse primer (Positions 1441 to 1465), 5′-GGAGGATGGGTGAGACGGGACAAAG-3′; and a Pol II/reverse primer, 5′-GGAAGTAGCCGTTATTAGTGGAGAGG-3′. The DNA was isolated from tail snips of 4 week-old mice using the QIAamp Tissue kit (Qiagen, Santa Clarita, CA). PCR analyses were performed under the following conditions: 1 cycle at 95°C for 1 min, 60°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min followed by 72°C for 7 min. A 309bp fragment indicates the presence of the WT allele and a 406bp fragment is amplified from the mutated allele.

Real-time PCR

Measurement of CCL5 mRNA expression in kidneys was completed by isolating total RNA using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies/Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) from the kidneys of 18 weeks old Fli-1+/− NZM2410 mice and WT littermates. 2ug of RNA was used to synthesize cDNA with the SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System (Life Technologies/Invitrogen). Real-time PCR was performed in duplicate using the Platinum SYBR Green PCR SuperMix UDG (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with three independent RNA preparations. The primers for the CCL5 gene were purchased from SABiosciences (Qiagen) and the cycling conditions for all genes followed instructions from the company. PCR was carried out using the CFX connect Real-time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad) and relative expression analysis was conducted using the program provided by SABiosciences (Qiagen).

Chemokine measurement

The concentration of the CCL5 protein in the supernatants of MS1 endothelial cells was determined by ELISA using the DuoSet® ELISA Development System for Mouse CCL5/RANTES from R&D Systems Inc. (Minneapolis, MN). The assays were performed following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

The ChIP assay was performed as described previously using an anti-Fli-1 rabbit polyclonal antibody (39–41). Briefly, total MS1 endothelial cells were cross-linked with formaldehyde; chromatin was isolated and immunoprecipitated with specific Fli-1 antibodies or rabbit IgG control. The genomic fragments associated with immunoprecipitated DNA were amplified by RT-PCR. Putative Ets-1 DNA binding sites (EBSs) were identified by examination of the CCL5 promoter sequence and the MatInspector software tool (Genomatix, Ann Arbor, MI). Based on these sites, the primers used for the ChIP assay were designed and are shown in Table I. PCR products were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized using ethidium bromide staining.

Table I.

Primers Used in the ChIP assay of the CCL5 Promoter

| Primer Name | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer | Position from TSS | Amplicon Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChIP1 | 5′ CAC CAT TCA CAC ACA TG 3′ | 5′ GTC AAG GGA TCT GAT AGG 3′ | −983 to −765 | 218bp |

| ChIP2 | 5′ CCT ATC AGA TCC CTT GAC 3′ | 5′ CTT AGT GTG TGA CAT GTG 3′ | −782 to −629 | 153bp |

| ChIP3 | 5′ CAC ATG TCA CAC ACT AAG 3′ | 5′ CCA TAT CAG AAA CAG ACC AC 3′ | −646 to −499 | 147bp |

| ChIP4 | 5′ GTG GTC TGT TTC TGA TAT GG 3′ | 5′ GTT AAG GTC AAG CCA TTG G 3′ | −518 to −392 | 126bp |

| ChIP5 | 5′ GTG AAG ACC AAT GGC TTG 3′ | 5′ CTC TGG CCA AAT ACA GTA GG 3′ | −417 to −271 | 146bp |

| ChIP6 | 5′ CCT ACT GTA TTT GGC CAG AG 3′ | 5′ CCA AAC ACT TGT TGC TGT C 3′ | −288 to −156 | 132bp |

| ChIP7 | 5′ CCT ACT TGC CTT AAG AC 3′ | 5′ GAC TCT GCC TCT AAC TG 3′ | −386 to −228 | 158bp |

| ChIP8 | 5′ CAG TTA GAG GCA GAG TC 3′ | 5′ CAG GAC TTG GGG AGT 3′ | −244 to −127 | 117bp |

| ChIP9 | 5′ ACT CCC CAA GTC CTG 3′ | 5′ GAT GCA TGT GCT GTC TCA G 3′ | −141 to −24 | 117bp |

| ChIP1 | 5′ CAC CAT TCA CAC ACA TG 3′ | 5′ GTC AAG GGA TCT GAT AGG 3′ | −983 to −765 | 218bp |

Primers are listed based on their distance from the TSS (transcription start site). The ChIP 7 primers cover the two EBS included in the ChIP5 and ChIP6 primers.

Reporter and Expression Constructs

A portion of the murine CCL5 promoter (from −1036bp to −52bp upstream of the transcription start site) corresponding to the previously defined promoter region in humans (1) was PCR amplified from genomic DNA isolated from a B6 mouse by modifying previously published primers (9). The forward primer 5′-ATT AAG CTA GCT CCT GTG CCC ACC A-3′ contains the NheI enzyme site (underlined) and the reverse primer 5′-ATT ATA CTC GAG GCA AGG GGT GCT CTG CA -3′ the XhoI enzyme site (underlined). The PCR program used to amplify the full length sequence was as follows: 94°C for 3min.; thirty cycles of 94°C for 30sec, 62°C for 30sec, 72°C for 1min; 72°C for 10min; held at 4°C until the program was stopped. The CCL5 promoter region was then directionally cloned into the pGL3 basic vector upstream of the Luciferase gene (Promega, Madison, WI). Region A of the CCL5 promoter was PCR amplified from the full length clone using the same PCR program detailed above. The forward primer, located −520bp upstream from the transcription start site, 5′ ATT AAG CTA GCG TGG TCT GTT TCT GAT ATG G 3′ contains the NheI enzyme site (underlined) and the reverse primer is identical to the one described above, but contained a HindIII site instead of the XhoI enzyme site. Region A of the CCL5 promoter was directionally cloned into the pGL3 basic vector. The Region B forward primer is located −746bp upstream of the transcription start site and contains an EcoRI site (underlined) 5′ ATT AGA ATT CGA CAG ACA GAC AAT AAA TAG 3′. The reverse primer was designed to the multicloning of the pGL3 basic vector and contains an EcoRI site (underlined) for easy ligation 5′ TAA TGA ATT CGC TAG CAC GCG TAA GA 3′. The linearized plasmid and the reverse primer were added to a PCR reaction and the amplification began as follows: 95°C for 3min; three cycles of 95°C for 30sec, 55°C for 30sec, 68°C for 6mins and then held at 80°C. At which point 1μl of the forward primer was added to the reaction. The PCR reaction proceeded as follows: 18 cycles of 95°C for 30sec, 55°C for 30sec, 68°C for 6mins; then 68°C for 10mins and held at 4°C until the program was stopped. A DpnI digestion was then carried out overnight at 37°C to remove the parent template. The PCR product was then digested with EcoRI and ligated together with T4 DNA ligase. All enzymes were obtained from New England BioLabs Inc. (Ipswitch, MA). All of the promoter constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing (Genewiz, South Plainfield, NJ). The mouse Fli-1 expression vector was obtained from Dr. Dennis Watson (Medical University of South Carolina) and confirmed by DNA sequencing. Briefly, the Fli-1 gene containing a 5′ kozak sequence and Flag tag, was cloned into the pcDNA3.0 expression vector (Life Technologies), which is under the control of a CMV promoter. The mouse Ets-1 cDNA was isolated from pGEM7ZEts1 (from Dr. Dennis Watson) by digestion with BamHI and EcoRI. The BamHI site was subsequently filled in and the isolated fragment was ligated into the EcoRI and EcoRV sites of the pcDNA3.0 vector. Both expression vectors have been described previously (42). The mouse Fli-1 DNA binding mutant construct is in the pSG5 expression vector (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) and contains a single amino acid change (Tryptophan 321 to Arginine) to prevent DNA binding. This construct was provided by Dr. Maria Trojanowska (Boston University, School of Medicine Arthritis Center, Boston, MA) and has been characterized previously (43, 44). For experiments with this construct, a mouse Fli-1 construct with an intact DNA binding domain in the pSG5 expression vector was used.

Cell lines and DNA Transfection

The mouse embryonic fibroblast NIH3T3 cell line was grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (Mediatech Inc., Manassas, VA) with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. The NIH3T3 cell line was used for all transient transfection experiments since it is a commonly used cell line for DNA transfection and the expression level of Fli-1 in these cells is not detectable. NIH3T3 cells were seeded at 4x105 cells per well in 6 well plates, one day prior to transfection. Transfections were performed using the Fugene 6 transfection reagent (Promega) following the manufacturer’s instructions. For all of the transfection experiments 2μg of the reporter constructs pGL3/basic, pGL3/CCL5, pGL3/CCL5RegionA and pGL3/CCL5RegionB were used. Equimolar concentrations of the expression constructs (pcDNA3.0, pcDNA/Ets1, and pcDNA/Fli1) were transfected into the cells. The Fli-1 dose response study used increasing amounts (0.025μg, 0.05μg, 0.1μg, 0.2μg, 0.25μg, 0.5μg, and 1μg) of the Fli-1 expression construct transfected into the cells. In the Fli-1 and Ets1 transfection experiment, 0.5μg of all expression constructs was transfected into the cells. For the competition studies, 0.25μg of the Fli-1 expression construct was held constant and increasing amounts of the Ets-1 expression construct (0.25μg, 0.5μg, 1μg, and 2μg) were transfected into the cells. For the deletion studies 0.5μg of the Fli-1 expression construct was used. The pcDNA3.0 construct was added to these studies so that equimolar amounts of total DNA were transfected into the cells. For the DNA binding domain mutant studies, 1μg of the Fli-1 and Fli-1 DNA binding mutant constructs were transfected into the cells and the pSG5 vector construct was used so that equimolar amounts of total DNA were transfected into the cells. In all experiments 200ng of a Renilla luciferase construct pRL/TK (Promega) was used as a transfection control. All of the transfected cells were harvested 48 hours after transfection. The murine endothelial MS1 cell line was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and maintained with DMEM medium with 5% fetal bovine serum. The cells were maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2. The MS1 endothelial cell line was used for the siRNA transfection experiments and the ChIP assay since Fli-1 expression has previously been shown to be detectable only in endothelial cells within the glomerulus (39). Specific Fli-1 siRNA and negative control siRNA was purchased from Invitrogen (Life Technologies) and transfected into MS1 cells using lipofectamine provided by Invitrogen (Life Technologies) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Transfected MS1 cells were cultured for 24hrs with DMEM plus 5% fetal bovine serum. One microgram of LPS (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was added to each well and incubated up to 24 hours. The supernatants were collected at the following time points after stimulation with LPS (0, 4, 6, and 24 hours) and CCL5 chemokine production was analyzed by ELISA.

Reporter Assays

Luciferase activity was measured using the Dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Promega) and the Luminoskan Ascent Microplate Luminometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Transfection activity was normalized to the activity of the co-transfected Renilla luciferase construct. Fold activation was calculated based on the activity over the pGL3/basic vector and the values are reported as mean ± standard error.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using a two tailed Student’s t-test based on calculated variances (unequal or equal) for transient transfection experiments. In most other cases a one tailed Student’s t-test with Welch’s correction was used to determine significance. The linear regression was determined using the statistics software provided in the Microsoft Exel Software.

Results

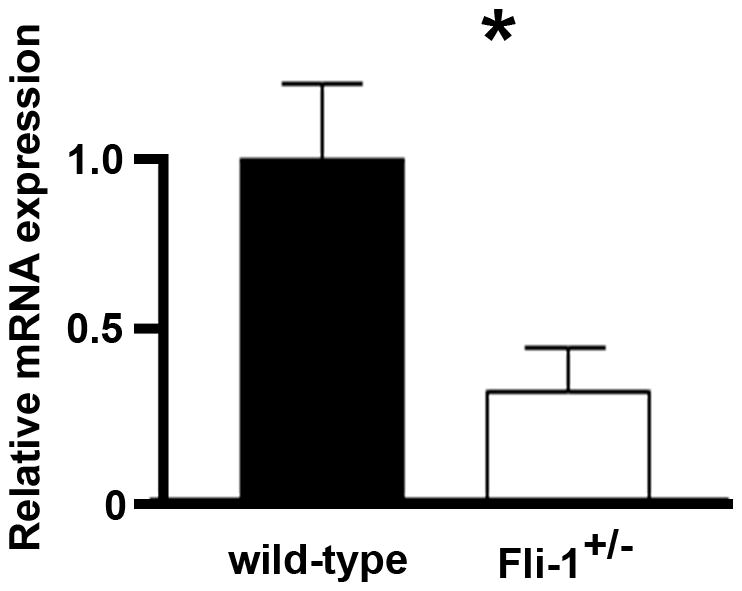

Expression of the inflammatory chemokine CCL5 is significantly reduced in kidneys of Fli-1+/− NZM2410 mice

To determine whether decreased Fli-1 plays a role in the expression of CCL5 mRNA in vivo, we examined the expression of CCL5 in kidneys of Fli-1+/− NZM2410 mice compared to WT littermates. The kidneys were removed from mice at the age of 18 weeks, prior to the onset of disease; to exclude the influence of disease related inflammatory cell infiltration. CCL5 mRNA expression was measured by RT-PCR. Figure 1 shows a greater than 50% significant reduction (p<0.05) of CCL5 mRNA expression was observed in Fli-1+/− NZM2410 mice (n=6 in each group) when compared to WT littermate controls.

Figure 1. Reduced CCL5 mRNA expression in kidneys from Fli-1+/− NZM2410 mice compared to WT littermates.

Total RNA was prepared from kidneys at the age of 18 weeks (n=6, each group). Total RNA was converted to cDNA with the Superscript First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen). Real-time polymerase chain reaction was performed in triplicate with the appropriate primers. The black bar represents WT and the white bar the heterozygous mice. A single asterisk indicates significance at p<0.05.

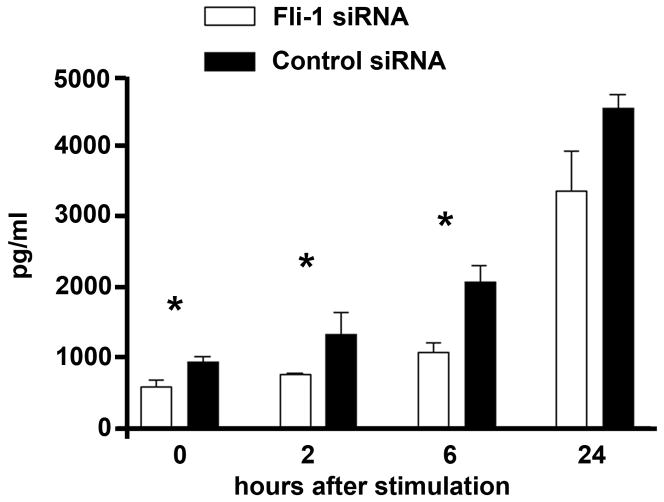

Inhibition of Fli-1 resulted in decreased production of CCL5 protein in endothelial cells

Fli-1 expression within kidneys has been primarily localized to endothelial cells within the glomerulus and co-expression with CCL2/MCP-1, another proinflammatory chemokine, has been observed (39). CCL5 expression in the glomerulus has also been documented previously (6, 10, 22–24). Thus, we chose to investigate if a disruption in Fli-1 expression affects CCL5 production in vitro; we performed transfection studies using Fli-1 specific siRNA and negative control siRNA in murine endothelial MS1 cells. The expression of Fli-1 protein was inhibited after transfection with specific siRNA (data not shown). Twenty four hours after transfection with siRNA, CCL5 protein concentrations were measured in the supernatants of MS1 endothelial cells after stimulation with LPS (1μg/ml) for 0, 4, 6, and 24 hours. As shown Figure 2, endothelial cells transfected with Fli-1 specific siRNA had significantly lower CCL5 concentrations compared to the endothelial cells transfected with control siRNA at 0, 4 and 6 hours after stimulation. Lower CCL5 concentrations 24 hours after LPS stimulation were also detected although the difference was not statistically significant.

Figure 2. Decreased CCL5 production in LPS stimulated MS1 endothelial cells transfected with Fli-1 siRNA.

CCL5 protein concentrations over time from supernatants of MS1 cells transfected with negative control siRNA (black bars) or Fli-1 specific siRNA (white bars) after stimulation with 1μg of LPS. Data presented are shown as the mean ± standard deviation where a single asterisk indicates p<0.05.

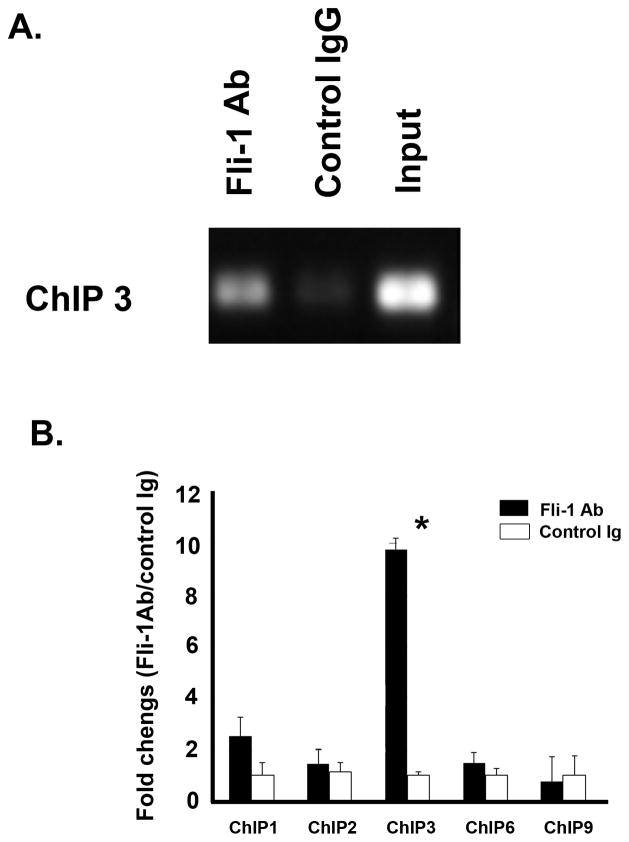

Fli-1 binds to the CCL5 promoter in endothelial cells

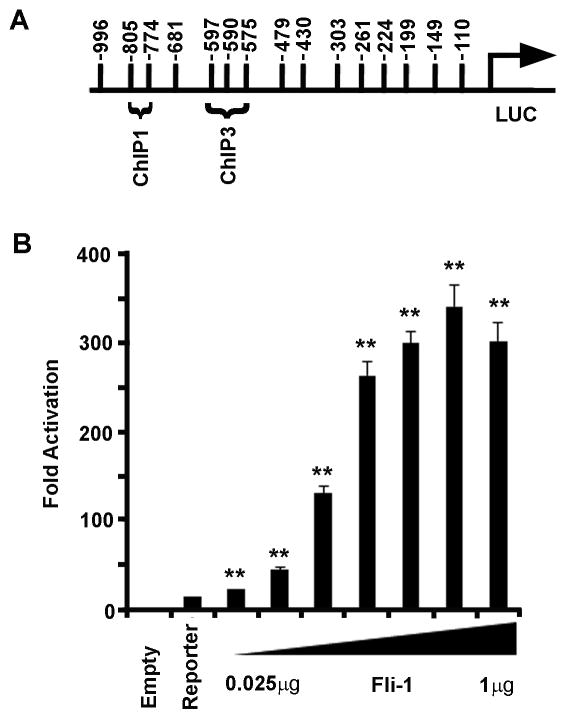

A ChIP assay was carried out to determine whether Fli-1 directly or indirectly regulates the expression of CCL5 in murine endothelial cells. Twelve putative EBSs were identified in the murine promoter region of the CCL5 gene and nine primer pairs were designed to cover these sites (Table 1, Figure 4A). After immunoprecipitation in endothelial cells with a Fli-1 specific antibody, five pairs of primers, ChIP1, ChIP2, ChIP3, ChIP6 and ChIP9 had PCR products and one of these sites, ChIP3, was significantly enriched with specific Fli-1 antibodies (Figure 3A, and 3B). Binding to ChIP1 was also increased, although the results were not statistically significant. These results clearly indicate that Fli-1 binds to the CCL5 promoter in endothelial cells and regulates the expression of CCL5.

Figure 4. Fli-1 drives transcription from the CCL5 promoter in a dose-dependent fashion.

(A.) Schematic diagram of the murine CCL5 promoter (948bp in length) cloned into the pGL3 vector, upstream of the luciferase reporter gene. The numbers indicate potential Ets binding sites as determined by visual inspection of the promoter region and the MatInspector Software (Genomatix). The binding sites determined by ChIP assay are labeled. (B.) Graph depicting the results of the luciferase assay. Transfections were carried out using increasing amounts of Fli-1 (0.025μg, 0.05μg, 0.1μg, 0.2μg, 0.25μg, 0.5μg, to 1μg). Values shown are as fold activation over the empty vector control are the mean + standard error for three replicate experiments (n=9). A two tailed student’s t-test with unequal variance was used to calculate significance, and double asterisks indicate a p-value of < 0.01.

Figure 3. Fli-1 binds to the CCL5 promoter.

Results of the ChIP assay performing indicating that Fli-1 binds to the distal regions of the RANTES promoter. (A.) Agarose gel image illustrating the ChIP 3 region of the promoter that binds Fli-1 after immunopreciptated with specific anti-Fli-1 antibody (Fli-1 Ab), control IgG, and positive control input. Input represents 1% of total cross-linked, reversed chromatin before immunoprecipitation. (B) Fold changes (Fli-1 antibody/control IgG) were calculated by RT-PCR and are shown for each primer pair. Data presented are shown as the mean ± standard deviation where a single asterisk indicates p<0.05.

Fli-1 drives transcription from the CCL5 promoter in a dose-dependent manner

Transient transfection assays were performed in order to demonstrate that Fli-1 regulates the expression of the CCL5 gene. The CCL5 murine promoter was PCR amplified from genomic DNA and cloned into the pGL3 basic reporter construct. The ability of Fli-1 to drive transcription from the CCL5 promoter was assessed by increasing the amount of Fli-1 transfected into the NIH3T3 cell line. A schematic diagram showing the CCL5 promoter including the putative EBSs and those identified to bind Fli-1 by ChIP assay cloned into the pGL3 basic vector can be found in Figure 4A. The transfection results clearly demonstrate that Fli-1 drives transcription from the CCL5 promoter in a dose-dependent manner. As little as 25ng of Fli-1 was needed to drive transcription from the promoter in a statistically significant fashion and all of the concentrations of Fli-1 used increased activation (Figure 4B).

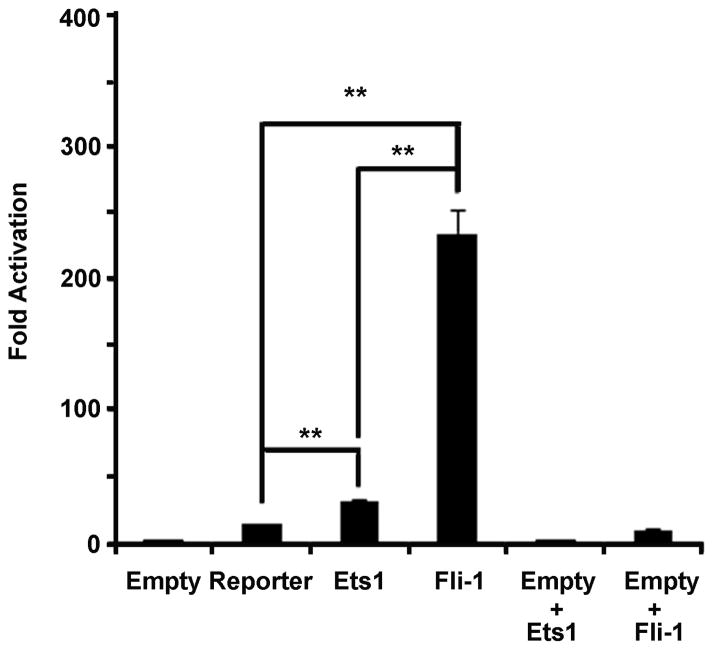

Both Ets1 and Fli-1 drive transcription from the CCL5 promoter, although activation with Fli-1 is stronger

Both Fli-1 and Ets1 are members of the Ets family of transcription factors and bind to the same core consensus motif. Therefore, transfections were completed to determine whether only Fli-1 drives transcription from the CCL5 promoter, or if Ets1 is capable of driving transcription as well. As shown in Figure 5, both Fli-1 and Ets1 drive transcription from the CCL5 promoter, however activation of the promoter is significantly stronger with Fli-1. Very little background activation was observed when Fli-1 or Ets1 were transfected without the CCL5 reporter construct.

Figure 5. Fli-1 drives transcription from the CCL5 promoter more strongly than Ets1.

Graph illustrating the results of transfection assays with Fli-1 or Ets1 and the CCL5 promoter. Equal amounts (0.5μg) of each transcription factor were used. Values shown are as fold activation over the empty vector control are the mean + standard error for three replicate experiments (n=9). A two tailed student’s t-test with unequal variance was used to calculate significance, and double asterisks indicate a p-value of < 0.01.

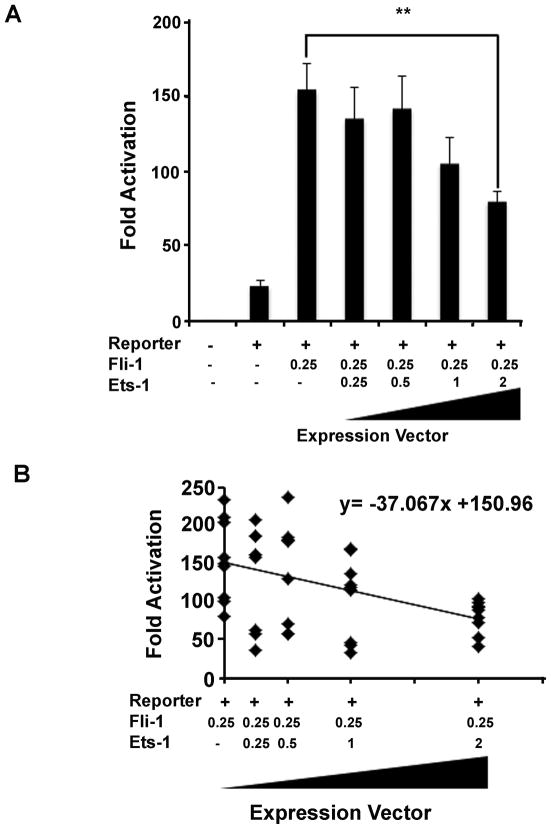

Ets1 acts as a dominant negative transcription factor to the activation of the CCL5 promoter by Fli-1

Since both Ets1 and Fli-1 activate transcription from the CCL5 promoter (Figure 5) and they bind to the same core consensus motif, we decided to see if Ets1 was acting as a dominant negative transcription factor to Fli-1. Increasing amounts of Ets1 were co-transfected into NIH3T3 cells along with a consistent amount of Fli-1 (0.25μg). The results show that as the concentration of the Ets1 transcription factor increased, the Fli-1 related activation from the CCL5 promoter decreased. Only the highest concentration of Ets1 (2μg) exhibited a statistically significant decrease (Figure 6A). A linear regression analysis of the data was also performed. The results depict a decreasing trend as the amount of Ets1 is increased and indicate that a 1μg addition of Ets1 will cause a 37-fold decrease in Fli-1 related expression (Figure 6B), confirming that Ets1 acts as a dominant negative transcription factor to Fli-1.

Figure 6. Ets1 acts as a dominant negative transcription factor to Fli-1 in the context of the CCL5 promoter.

(A.) Results of transfection experiments to determine whether Ets1 acts as a dominant negative transcription factor over Fli-1. The table below the graph indicates the amount of each expression vector used in the transfection. The amount of Fli-1 added was held constant at 0.25μg, while increasing amounts of Ets1 were transfected. Values shown are as fold activation over the empty vector control are the mean + standard error for three replicate experiments (n=9). A two tailed student’s t-test with unequal variance was used to calculate significance, and double asterisks indicate a p-value of < 0.01. (B.) Graph showing the linear regression calculated from the transfection results where Fli-1 and Ets1 were co-transfected. The amount of each expression construct is depicted in the table below and the linear regression equation is located in the upper right corner of the graph.

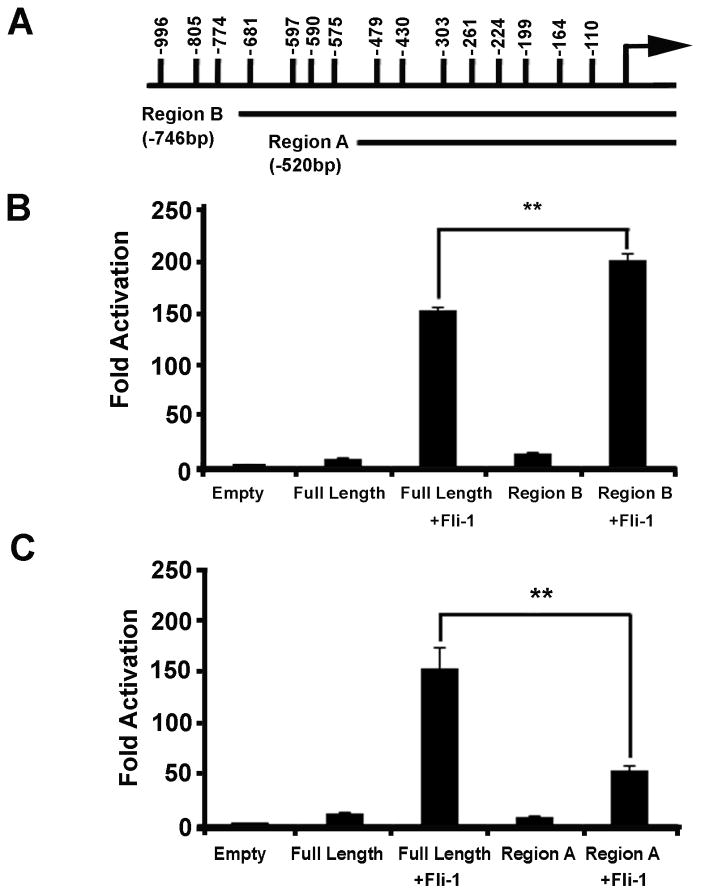

Activation of the CCL5 promoter by Fli-1 occurs primarily between −746bp and −520bp

Deletion constructs were designed in an effort to determine where along the CCL5 promoter Fli-1 binds. The location of the EBSs and the deletion constructs are depicted in Figure 7A. The Region B construct removes the most distal EBSs that cover the primers tested for in ChIP1, while the Region A construct removes the EBSs covered by the ChIP2 and ChIP3 primers (Table 1). Removal of the most distal EBSs (Region B) does not result in loss of activation by Fli-1, rather a statistically significant increase in activation was observed (Figure 7B). Conversely, upon deletion of the ChIP2 and ChIP3 putative EBSs, activation of the CCL5 promoter by Fli-1 is drastically reduced (Figure 7C). Compared to the activation of the full length promoter by Fli-1, 65% of the activity is lost upon removal of the EBSs between −746bp and −520bp.

Figure 7. Activation of the CCL5 promoter by Fli-1 occurs between −746bp and −520bp.

(A.) Schematic diagram of the murine CCL5 promoter region, depicting the location of two deletion constructs (and their size in bp) designed to determine the region responsible for Fli-1 activation. (B.) Results of transfection experiments using Region B of the CCL5 promoter, which removes the three most distal EBSs. (C.) Results of transfection experiments using Region A of the CCL5 promoter, which removes 7 EBSs (including the ChIP2 and ChIP3 regions). Values shown are as fold activation over the empty vector control are the mean + standard error for three replicate experiments (n=9). A two tailed student’s t-test with unequal variance was used to calculate significance, and double asterisks indicate a p-value of < 0.01.

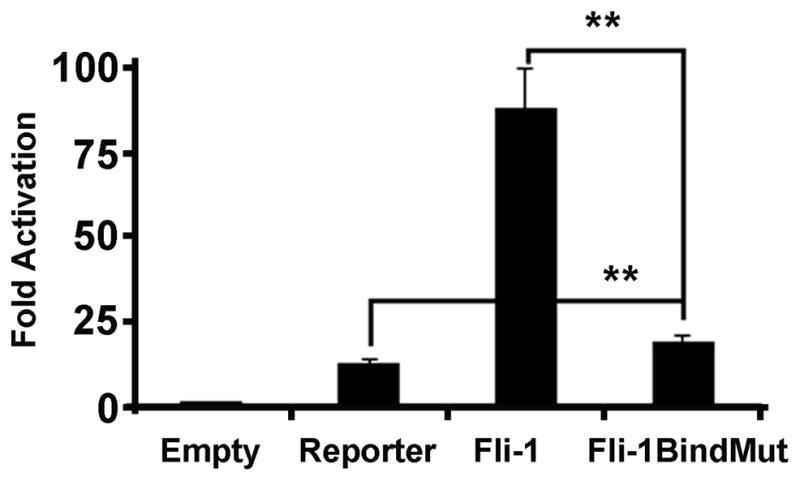

Mutation of the DNA binding domain of Fli-1 impairs transcriptional activation of the CCL5 promoter

To establish whether Fli-1 drives transcription from the CCL5 promoter through direct binding of the promoter, transient transfection assays were performed using a Fli-1 construct in which a single amino acid change (Tryptophan 321 to Arginine) prevents DNA binding (43). Mutation of the Fli-1 DNA binding domain resulted in significantly diminished activation from the CCL5 promoter. Compared to promoter activation with an intact DNA binding domain, activity was reduced by 78% (Figure 8). Some ability to regulate transcription remains as the Fli-1 DNA binding domain mutant was still able to activate transcription when compared to the reporter construct alone.

Figure 8. Fli-1 regulates CCL5 through direct binding of the promoter.

Graph depicting the results of the luciferase assay using the Fli-1 DNA binding domain mutant (Fli-1BindMut) on the full length CCL5 promoter. Values shown are as fold activation over the empty vector control are the mean + standard error for three replicate experiments (n=9). A two tailed student’s t-test with unequal variance was used to calculate significance, and double asterisks indicate a p-value of < 0.01.

Discussion

This study has identified Fli-1 as a previously undiscovered transcriptional regulator of the inflammatory chemokine CCL5. CCL5 mRNA expression was significantly reduced in response to heterozygous expression of the Fli-1 gene in kidneys of NZM2410 mice prior to the onset of disease. Upon complete knockdown of the Fli-1 gene using siRNA, CCL5 protein expression in LPS stimulated endothelial cells was also significantly affected. ChIP assay demonstrated that Fli-1 binds to the murine CCL5 promoter and transient transfection studies further confirmed that Fli-1 directly regulates the expression of the CCL5 gene.

Chemokines, such as CCL5, play a critical role in the inflammatory response, particularly in the recruitment of inflammatory cells to areas of disease or injury (2, 15, 16, 19, 20). CCL5 has been implicated in the pathogenesis of several inflammatory mediated diseases including asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, and SLE (7, 15–18). We have previously demonstrated a significant role for the Fli-1 transcription factor in the development of renal disease, glomerulonephritis and the pathogenesis of SLE (34–39). Fli-1+/− NZM2410 mice had significantly reduced infiltration of inflammatory cells into kidneys, with more than a 50% decrease in CD3+ and CD11b+ cells and more than a 70% decrease in CD19+ cells compared to wild-type littermate controls (39). Additionally, we have found that Fli-1 directly regulates expression of CCL2/MCP-1 (39). Given the profound effects on inflammatory cell infiltration, we hypothesized that Fli-1 regulates chemokines other than CCL2/MCP1. Based on reports that CCL5 plays a role in recruitment of inflammatory cells and the development of glomerulonephritis we sought to determine if Fli-1 regulates the expression of CCL5. To test this relationship in vivo, kidneys were harvested from Fli-1+/− NZM2410 mice before they displayed symptoms of murine lupus nephritis, thus removing the influence of migrating inflammatory cells related to the disease. CCL5 mRNA expression was reduced in vivo by over 50% in kidneys of mice with heterozygous expression of Fli-1 (Figure 1).

The localization of endothelial cells allows them to play a key role in the inflammatory response by homing immune cells through the production of chemokines and cytokines. CCL5 has been shown to be present and its’ expression regulated by Th2 type cytokines in endothelial cells (4). In the MS1 endothelial cell line, stimulation of CCL5 protein concentration by LPS was observed to increase over a 24 hour period (Figure 2). A rapid up-regulation of CCL5 in response to induction by LPS has been observed previously (11). In this study, CCL5 protein concentrations were significantly decreased at 0, 4 and 6 hours after stimulation when Fli-1 was knocked down by siRNA (Figure 2). While CCL5 protein concentrations were decreased after 24 hours, the results were no longer significant. This may be due to the fact that transient CCL5 stimulation by LPS occurs primarily between 3–12 hours after which induction subsides (11), which may impact the ability of Fli-1 to bind to the CCL5 promoter. These results are consistent with previous findings that glomerular CCL5 mRNA expression is induced by LPS 3 to 6 hours after stimulation (10, 23) and has been shown to effect the binding of NFkB, C/EBP, and AP-1 transcription factors to the CCL5 promoter (10). Our results suggest that a reduction in Fli-1, leads to a reduction in LPS induced CCL5 expression, which may ultimately affect the ability of other transcriptional regulators of CCL5 to bind to their cognate DNA binding sites. Previous studies determined that at least 40% of the LPS induced promoter activation in CCL5 is mediated thru the CRE/AP-1 binding motif, which is located near an EBS that binds another Ets family member PU.1 (11). This highlights the complex transcriptional mechanisms involved in the chemokine mediated inflammatory response and may suggest a role for Ets family members in the recruitment of other transcription factors and in the coordinated assembly of the regulatory complex.

ChIP assay demonstrated that Fli-1 binds to the murine CCL5 promoter (Figure 3). It would appear that Fli-1 binds primarily to the distal region of the CCL5 promoter. The region that showed the strongest Fli-1 binding affinity contains three potential EBSs within a 22bp stretch of DNA (Figure 4A). To further demonstrate that Fli-1 regulates the transcription of the CCL5 gene, transient transfection assays were performed. The results clearly establish that Fli-1 drives transcription from the CCL5 promoter, with as little as 25ng of Fli-1 needed to activate transcription in a statistically significant manner (Figure 4B) and prove that Fli-1 is a direct regulator of the CCL5 gene. Ets1 was also able to drive transcription from the CCL5 promoter, but at a significantly lower level than the Fli-1 (Figure 5). Therefore, we investigated whether Ets1 and Fli-1 were in direct competition with one another. The results confirm that Ets1 acts as a dominant negative transcription factor to Fli-1 (Figure 6). Linear regression analysis reveals that by increasing the amount of Ets1 decreases the activation of the CCL5 promoter achieved by Fli-1 (Figure 6B). These results suggest that Fli-1 and Ets1 are in competition for binding sites on the CCL5 promoter and imply another level of transcriptional regulation. In fibroblasts, Ets1 and Fli-1 have been shown to possess reciprocal function in the regulation of the human α2(I) collagen promoter (43) and maintaining balance in the expression of these two factors is likely key to achieving homeostatis within ECM (29). The binding of multiple Ets family members to the same EBS as a means of gene regulation has also been previously reported (45). Thus it seems likely that a complex mechanism of transcriptional control is responsible for the regulation of the inflammatory chemokine CCL5.

The results of the systematic deletion of the distal EBSs suggest that Fli-1 is binding to the CCL5 promoter between −746bp and −520bp (Figure 7). These results are consistent with the results of the ChIP assay that indicated that Fli-1 had the strongest binding affinity to the ChIP3 region. That Fli-1 may activate transcription from the region between −746bp and −520bp of the promoter is particularly interesting given the fact that most of the known active transcription factor binding sites have been mapped to the proximal promoter. It was originally shown that only the promoter region from −421bp to the transcription start site was required for activation in most cell types (1) and a more recent review paper detailing the role of the regulation of CCL5 in renal disease maps a majority of the transcriptional mechanisms involved in CCL5 gene expression to the region from −195bp to the transcription start site (21). The IRF1 and INFγ response element was mapped from −147 to −143bp within the murine CCL5 promoter (8). The IRF1 binding site and the NFkB binding site between −87 to −79bp work synergistically together and are responsible for stimulation by INFγ and TNFα (9). These two transcription factors also interact with Ets family member PU.1 that binds to the murine promoter immediately upstream of the NFkB binding site (12). Within the rat CCL5 promoter C/EBP binds at −486bp and NFkB binds at −100bp, although distal promoter sites further upstream than the defined murine and human promoter regions also demonstrated transcription factor binding to the AP-1 site at −1149bp and an NFkB site at −1593bp (10). ATF and Jun bind to the CRE/AP-1 site at −197bp and PU.1 binds to the EBS at-205bp of the human promoter (11) and the KLF13 transcription factor binds between −71 and −53bp (14, 21). Thus, for the most part, transcription factor binding and activation have primarily been mapped to proximal regions of the CCL5 promoter. The results of this study indicate that the Fli-1 and to a lesser extent Ets1 transcription factors bind to the distal region of the murine CCL5 promoter and regulate transcription differently from other previously described transcription factors.

Deletion of the most distal region of the CCL5 promoter, enhances transcriptional activation by Fli-1 (Figure 7B), suggesting that there may be elements of this region that repress Fli-1 activation. Further highlighting the complexity involved in the transcriptional control of CCL5. Unlike the modest results obtained with the human α2(I) collagen promoter (43), mutation of the Fli-1 DNA binding domain reduced Fli-1 mediated activation of the CCL5 promoter by 78% (Figure 8). These results strongly suggest that Fli-1 is activating transcription by binding directly to the CCL5 promoter. Some transcriptional activity remains after Fli-1 DNA binding ability has been removed, suggesting that some indirect protein-protein interactions may also contribute to the regulation of this gene.

Both Fli-1 and CCL5 are involved in the progression and pathogenesis of SLE. In this study, we have demonstrated that a reduction in Fli-1 gene expression significantly impacts the expression of CCL5 mRNA in kidneys and CCL5 protein expression in MS1 endothelial cells. This is due to the fact that Fli-1 binds to the distal region of the CCL5 promoter and directly regulates gene transcription. Combined with our previous finding that Fli-1 regulates the expression of another inflammatory chemokine, CCL2/MCP-1 (39), it is evident that one of the ways in which Fli-1 impacts the development of SLE is through the regulation of proinflammatory chemokines that recruit infiltrating inflammatory cells to the kidney. Thus further investigation into the precise transcriptional regulatory mechanisms, of which Fli-1 is a key player, will lead to a better understanding of the pathogenesis of disease and may lead to the development of novel therapies in the prevention of SLE.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Dennis Watson at Medical University of South Carolina for the Fli-1 expression vector and Dr. Maria Trojanowska from the Boston University School of Medicine Arthritis Center for the Fli-1 DNA binding mutant.

Footnotes

This research was funded in part by the National Institute of Health (NIAMS, AR056670 to X.K.Z.) and the South Carolina Clinical & Translational Research Institute (SCTR) Voucher Pilot Program NIH/NCRR Grants UL1 RR029882 and UL1 TR000062.

References

- 1.Nelson PJ, Kim HT, Manning WC, Goralski TJ, Krensky AM. Genomic organization and transcriptional regulation of the RANTES chemokine gene. J Immunol. 1993;151:2601–2612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oppenheim JJ, Zachariae CO, Mukaida N, Matsushima K. Properties of the novel proinflammatory supergene “intercrine” cytokine family. Annu Rev Immunol. 1991;9:617–648. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.003153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schall TJ, Jongstra J, Dyer BJ, Jorgensen J, Clayberger C, Davis MM, Krensky AM. A human T cell-specific molecule is a member of a new gene family. J Immunol. 1988;141:1018–1025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marfaing-Koka A, Devergne O, Gorgone G, Portier A, Schall TJ, Galanaud P, Emilie D. Regulation of the production of the RANTES chemokine by endothelial cells. Synergistic induction by IFN-gamma plus TNF-alpha and inhibition by IL-4 and IL-13. J Immunol. 1995;154:1870–1878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heeger P, Wolf G, Meyers C, Sun MJ, O’Farrell SC, Krensky AM, Neilson EG. Isolation and characterization of cDNA from renal tubular epithelium encoding murine Rantes. Kidney Int. 1992;41:220–225. doi: 10.1038/ki.1992.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolf G, Aberle S, Thaiss F, Nelson PJ, Krensky AM, Neilson EG, Stahl RA. TNF alpha induces expression of the chemoattractant cytokine RANTES in cultured mouse mesangial cells. Kidney Int. 1993;44:795–804. doi: 10.1038/ki.1993.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rathanaswami P, Hachicha M, Sadick M, Schall TJ, McColl SR. Expression of the cytokine RANTES in human rheumatoid synovial fibroblasts. Differential regulation of RANTES and interleukin-8 genes by inflammatory cytokines. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:5834–5839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu J, Guan X, Ma X. Interferon regulatory factor 1 is an essential and direct transcriptional activator for interferon {gamma}-induced RANTES/CCl5 expression in macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:24347–24355. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500973200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee AH, Hong JH, Seo YS. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha and interferon-gamma synergistically activate the RANTES promoter through nuclear factor kappaB and interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF-1) transcription factors. Biochem J. 2000;350(Pt 1):131–138. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pocock J, Gomez-Guerrero C, Harendza S, Ayoub M, Hernandez-Vargas P, Zahner G, Stahl RA, Thaiss F. Differential activation of NF-kappa B, AP-1, and C/EBP in endotoxin-tolerant rats: mechanisms for in vivo regulation of glomerular RANTES/CCL5 expression. J Immunol. 2003;170:6280–6291. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.12.6280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boehlk S, Fessele S, Mojaat A, Miyamoto NG, Werner T, Nelson EL, Schlondorff D, Nelson PJ. ATF and Jun transcription factors, acting through an Ets/CRE promoter module, mediate lipopolysaccharide inducibility of the chemokine RANTES in monocytic Mono Mac 6 cells. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:1102–1112. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(200004)30:4<1102::AID-IMMU1102>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu J, Ma X. Interferon regulatory factor 8 regulates RANTES gene transcription in cooperation with interferon regulatory factor-1, NF-kappaB, and PU.1. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:19188–19195. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602059200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Song A, Chen YF, Thamatrakoln K, Storm TA, Krensky AM. RFLAT-1: a new zinc finger transcription factor that activates RANTES gene expression in T lymphocytes. Immunity. 1999;10:93–103. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Song A, Patel A, Thamatrakoln K, Liu C, Feng D, Clayberger C, Krensky AM. Functional domains and DNA-binding sequences of RFLAT-1/KLF13, a Kruppel-like transcription factor of activated T lymphocytes. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:30055–30065. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204278200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Powell N, Humbert M, Durham SR, Assoufi B, Kay AB, Corrigan CJ. Increased expression of mRNA encoding RANTES and MCP-3 in the bronchial mucosa in atopic asthma. Eur Respir J. 1996;9:2454–2460. doi: 10.1183/09031936.96.09122454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ying S, Meng Q, Taborda-Barata L, Corrigan CJ, Barkans J, Assoufi B, Moqbel R, Durham SR, Kay AB. Human eosinophils express messenger RNA encoding RANTES and store and release biologically active RANTES protein. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:70–76. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu MM, Wang J, Pan HF, Chen GM, Li J, Cen H, Feng CC, Ye DQ. Increased serum RANTES in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:1231–1233. doi: 10.1007/s00296-010-1761-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lit LC, Wong CK, Tam LS, Li EK, Lam CW. Raised plasma concentration and ex vivo production of inflammatory chemokines in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:209–215. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.038315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schall TJ, Bacon K, Toy KJ, Goeddel DV. Selective attraction of monocytes and T lymphocytes of the memory phenotype by cytokine RANTES. Nature. 1990;347:669–671. doi: 10.1038/347669a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moore KJ, Wada T, Barbee SD, Kelley VR. Gene transfer of RANTES elicits autoimmune renal injury in MRL-Fas(1pr) mice. Kidney Int. 1998;53:1631–1641. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krensky AM, Ahn YT. Mechanisms of disease: regulation of RANTES (CCL5) in renal disease. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2007;3:164–170. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph0418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xie C, Liu K, Fu Y, Qin X, Jonnala G, Wang T, Wang HW, Maldonado M, Zhou XJ, Mohan C. RANTES deficiency attenuates autoantibody-induced glomerulonephritis. J Clin Immunol. 2011;31:128–135. doi: 10.1007/s10875-010-9470-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haberstroh U, Pocock J, Gomez-Guerrero C, Helmchen U, Hamann A, Gutierrez-Ramos JC, Stahl RA, Thaiss F. Expression of the chemokines MCP-1/CCL2 and RANTES/CCL5 is differentially regulated by infiltrating inflammatory cells. Kidney Int. 2002;62:1264–1276. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2002.kid572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Teramoto K, Negoro N, Kitamoto K, Iwai T, Iwao H, Okamura M, Miura K. Microarray analysis of glomerular gene expression in murine lupus nephritis. J Pharmacol Sci. 2008;106:56–67. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fp0071337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zwiech R. Predictive value of conjointly examined IL-1ra, TNF-R I, TNF-R II, and RANTES in patients with primary glomerulonephritis. J Korean Med Sci. 2013;28:261–267. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2013.28.2.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dittmer J. The biology of the Ets1 proto-oncogene. Mol Cancer. 2003;2:29. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-2-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sementchenko VI, Watson DK. Ets target genes: past, present and future. Oncogene. 2000;19:6533–6548. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watson DK, Smyth FE, Thompson DM, Cheng JQ, Testa JR, Papas TS, Seth A. The ERGB/Fli-1 gene: isolation and characterization of a new member of the family of human ETS transcription factors. Cell Growth Differ. 1992;3:705–713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hsu T, Trojanowska M, Watson DK. Ets proteins in biological control and cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2004;91:896–903. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karim FD, Urness LD, Thummel CS, Klemsz MJ, McKercher SR, Celada A, Van Beveren C, Maki RA, Gunther CV, Nye JA, et al. The ETS-domain: a new DNA-binding motif that recognizes a purine-rich core DNA sequence. Genes Dev. 1990;4:1451–1453. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.9.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li R, Pei H, Watson DK. Regulation of Ets function by protein - protein interactions. Oncogene. 2000;19:6514–6523. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Georgiou P, Maroulakou I, Green J, Dantis P, Romanospica V, Kottaridis S, Lautenberger J, Watson D, Papas T, Fischinger P, Bhat N. Expression of ets family of genes in systemic lupus erythematosus and Sjogren’s syndrome. Int J Oncol. 1996;9:9–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang XK, Papas TS, Bhat NK, Watson DK. Generation and characterization of monoclonal antibodies against the ERGB/FLI-1 transcription factor. Hybridoma. 1995;14:563–569. doi: 10.1089/hyb.1995.14.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang XK, Gallant S, Molano I, Moussa OM, Ruiz P, Spyropoulos DD, Watson DK, Gilkeson G. Decreased expression of the Ets family transcription factor Fli-1 markedly prolongs survival and significantly reduces renal disease in MRL/lpr mice. J Immunol. 2004;173:6481–6489. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.10.6481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mathenia J, Reyes-Cortes E, Williams S, Molano I, Ruiz P, Watson DK, Gilkeson GS, Zhang XK. Impact of Fli-1 transcription factor on autoantibody and lupus nephritis in NZM2410 mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;162:362–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04245.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bradshaw S, Zheng WJ, Tsoi LC, Gilkeson G, Zhang XK. A role for Fli-1 in B cell proliferation: implications for SLE pathogenesis. Clin Immunol. 2008;129:19–30. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Molano I, Mathenia J, Ruiz P, Gilkeson GS, Zhang XK. Decreased expression of Fli-1 in bone marrow-derived haematopoietic cells significantly affects disease development in Murphy Roths Large/lymphoproliferation (MRL/lpr) mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;160:275–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.04080.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang L, Eddy A, Teng YT, Fritzler M, Kluppel M, Melet F, Bernstein A. An immunological renal disease in transgenic mice that overexpress Fli-1, a member of the ets family of transcription factor genes. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6961–6970. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.12.6961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suzuki E, Karam E, Williams S, Watson DK, Gilkeson G, Zhang XK. Fli-1 transcription factor affects glomerulonephritis development by regulating expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in endothelial cells in the kidney. Clin Immunol. 2012;145:201–208. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang XK, Moussa O, LaRue A, Bradshaw S, Molano I, Spyropoulos DD, Gilkeson GS, Watson DK. The transcription factor Fli-1 modulates marginal zone and follicular B cell development in mice. J Immunol. 2008;181:1644–1654. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.3.1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jackers P, Szalai G, Moussa O, Watson DK. Ets-dependent regulation of target gene expression during megakaryopoiesis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:52183–52190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407489200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Svenson JL, Chike-Harris K, Amria MY, Nowling TK. The mouse and human Fli1 genes are similarly regulated by Ets factors in T cells. Genes Immun. 2010;11:161–172. doi: 10.1038/gene.2009.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Czuwara-Ladykowska J, Shirasaki F, Jackers P, Watson DK, Trojanowska M. Fli-1 inhibits collagen type I production in dermal fibroblasts via an Sp1-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:20839–20848. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010133200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bailly RA, Bosselut R, Zucman J, Cormier F, Delattre O, Roussel M, Thomas G, Ghysdael J. DNA-binding and transcriptional activation properties of the EWS-FLI-1 fusion protein resulting from the t(11;22) translocation in Ewing sarcoma. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:3230–3241. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.5.3230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Klappacher GW, V, Lunyak V, Sykes DB, Sawka-Verhelle D, Sage J, Brard G, Ngo SD, Gangadharan D, Jacks T, Kamps MP, Rose DW, Rosenfeld MG, Glass CK. An induced Ets repressor complex regulates growth arrest during terminal macrophage differentiation. Cell. 2002;109:169–180. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00714-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]