Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the effect of providing patients online access to their electronic health record (EHR) and linked transactional services on the provision, quality and safety of healthcare. The objectives are also to identify and understand: barriers and facilitators for providing online access to their records and services for primary care workers; and their association with organisational/IT system issues.

Setting

Primary care.

Participants

A total of 143 studies were included. 17 were experimental in design and subject to risk of bias assessment, which is reported in a separate paper. Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria have also been published elsewhere in the protocol.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Our primary outcome measure was change in quality or safety as a result of implementation or utilisation of online records/transactional services.

Results

No studies reported changes in health outcomes; though eight detected medication errors and seven reported improved uptake of preventative care. Professional concerns over privacy were reported in 14 studies. 18 studies reported concern over potential increased workload; with some showing an increase workload in email or online messaging; telephone contact remaining unchanged, and face-to face contact staying the same or falling. Owing to heterogeneity in reporting overall workload change was hard to predict. 10 studies reported how online access offered convenience, primarily for more advantaged patients, who were largely highly satisfied with the process when clinician responses were prompt.

Conclusions

Patient online access and services offer increased convenience and satisfaction. However, professionals were concerned about impact on workload and risk to privacy. Studies correcting medication errors may improve patient safety. There may need to be a redesign of the business process to engage health professionals in online access and of the EHR to make it friendlier and provide equity of access to a wider group of patients.

A1. Systematic review registration number

PROSPERO CRD42012003091.

Keywords: PRIMARY CARE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

There was a dearth of evidence from high-quality studies about the impact of online access, although the evidence around online services issues was more comprehensive.

Many of the studies in this review originate from the USA, from large health plan-based programmes; a minority of studies originate from Europe.

Owing to the inclusive nature of the review, we recruited a team of expert reviewers from a broad range of professional backgrounds (health, academia and policy) who volunteered to help with the RCGP initiative about online access. This group provided a rich resource in order to extract relevant data and share information, through regular teleconferences. However, this inclusivity may have resulted in some inconsistencies.

Like all systematic reviews, evidence has been gathered from various resources from a specific time period. As such, there may be new papers recently published that have not been included in this review.

Introduction

Online services and applications are increasingly part of normal life. Personal computers are ubiquitous in the workplace, and many people have 24 h access through smartphones and a range of other devices.

Providing patient online record access has been described as fundamental to patient empowerment, but UK progress to date has been limited in part by professional resistance and concerns about security and privacy,1–3 legal constraints4 and low uptake of previous schemes to provide online resources for patients. These medicolegal concerns have been echoed in other international studies.5 The tensions between the growing consumer demand to access data and a healthcare system not yet ready to meet these demands have increased in recent years.6 7 The promise of linking personal records from multiple sources into a readily digestible single online record has not yet been realised.8 9 Plans to provide patients online access10 have been successfully piloted,11 but not widely adopted. Patients were concerned about the relative brevity of the record and that any mistakes, though few, could be clinically significant.12 Hybrid access involving an adult or a carer for children and young people complicates arrangements further.13

There have been some notable international successes in the provision of online services. Kaiser Permanente has had two-thirds of its 3.4 million members sign up for online appointment booking, test result collection and email.14 The USA Veterans Administration has also registered large numbers online with over 600 000 users making over 20 million ‘visits’ over the internet by 2008, the most popular service being online repeat prescription requests.15 The UK government announced in its health strategy that all patients in the English National Health Service (NHS) are to have access to their own health record by 2015.16 However, the guidance developed by pioneers of patient record access and published by the RCGP in 2010 has not been widely adopted17 and has now been superseded by updated guidance.18

Provision of online services for patients can be largely grouped into two areas.

Patient online access to their medical record. The ability to view, and sometimes edit or comment, on their electronic health record (EHR).

There are also other online services linked to EHR provision. These can be grouped into those that involve a human interaction to generate a personal response to a question, largely communication with your practice, doctor or other healthcare worker by email or through a web portal, and those where the transaction is purely digital, for example booking an appointment or receiving notification of a test result.

We carried out this study to inform this important new national policy directive by identifying how access might impact on the provision, quality and safety of healthcare.

Methods

We identified four key research questions developed from an approach used in a recent systematic review (box 1).19 This paper is an evidence synthesis that should be read in conjunction with our systematic review of 17 experimental studies; these studies were reported separately on the basis that we could assess their risk of bias.20 This paper aims to bring together this research and highlights the breadth and detail of evidence emerging from each of our original research questions.

Box 1. Aim, Objectives and Research Questions.

Aim:

To assess the factors which may affect the provision of online patient access to their EHR and transactional services and the impact of such access on the quality and safety of healthcare.

Objectives

Identify and understand the barriers and facilitators to providing online access to records and transactional services in ambulatory care.

Assess the benefits and harms of online access to records and transactional services in ambulatory care and how they affect the quality and safety of healthcare.

Key research questions:

Research Question 1(RQ1): What is the association between online patient access to their EHR and:

Utilisation of healthcare;

Health outcomes including patient safety;

Patient experience and satisfaction;

Adherence,

Equity and

Efficiency;

and wherever possible to identify the impact of online patient access to their EHR.

Research Question 2 (RQ2): What is the association between online patient access to transactional services provided as part of their ambulatory care EHR and:

Utilisation of healthcare;

Health outcomes including patient safety;

Patient experience and satisfaction;

Adherence,

Equity and

Efficiency;

and wherever possible to identify the impact of online patient access to transactional services.

Research Question 3 (RQ3): What is the association between practitioner and healthcare team being provided with:

Education and staff training;

Making workload and workflow changes,

Achieving regulatory compliance and

Business process changes for ambulatory care;

and patient uptake of online access and transactional services as part of their ambulatory care.

Research Question 4 (RQ4): What is the association between:

IT developments which provide records access,

Systems to enhance privacy and security,

Usability and accessibility of transactional services, and

Business process for technical development of EHR systems, including lead time in their development;

and patient uptake of online access and transactional services as part of their ambulatory care.

We used an established methodology, following Cochrane guidance for the review process21 and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta Analysis (PRISMA) framework.22 The protocol for this review has already been published, including details of the key research questions and inclusion and exclusion criteria.23 24 The study aims were structured in a systematic way, using the elements of a clinical research question (population, intervention, comparator and outcome/PICO).20 25

Search strategies were developed and run on 10 bibliographic databases: Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), the Cochrane database, Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group (EPOC), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), Embase, King's Fund, Medline, Nuffield Health and PsycINFO. Search for unpublished material was conducted using the database OpenGrey. Search strings were tailored to each database according to each source using Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) and index terms. The total number of papers identified was 9877. An example Medline search string can be viewed in our previous publication.20

Screening against the inclusion criteria was carried out by SdeL, FM & MC to identify relevant papers using a framework of the types of relevant interventions and a detailed inclusion–exclusion guide.20 Full text papers were sourced at this stage and apportioned to group members for review. The group members were volunteers who had expressed interest in joining Working Group 7 (and evaluation of the evidence) of a larger Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) exercise to define a Road Map for providing patients online access to their medical records. We recruited a purposeful sample of academics, practitioners and patient representatives with the relevant expertise. This group was given autonomy to review the evidence and has reported separately from the Road Map report.18 Evidence was subject to dual data extraction (group member and FM).

Refining the data collection forms and training the assessors

Two pilot paper-based exercises were conducted to refine the data collection tools, ensure consistency in the reviews and to inform design of online data capture forms. We also developed a data extraction form (DEF) which was used to extract the salient points from each paper. DEF training was provided to our group members in order to facilitate their review of evidence. The DEF also included a risk of bias (RoB) form for each paper, which aimed to look at limitations in study design.20 The RoB form was included with the intention of applying the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) tool to assess the strength of evidence as a collective for each research question.26–28 The RoB form was grouped into six domains: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting and other bias. Although all papers were subject to a RoB assessment, only a small number (n=17) were experimental in design; and these had a wide variation in their RoB. A detailed summary of these trials and RoB analysis can be seen in our previous publication.20

The review forms were returned via the website (http://www.clininf.eu/projects/patient-access/paper-review-form.html) or directly to individual team members.

Where reviewers disagreed about ratings we reached a final rating by consensus. A meta-analysis could not be undertaken, as included studies were not sufficiently homogeneous in terms of primary outcome measures to provide a meaningful summary. As such, we chose to adopt an established qualitative method to guide this synthesis.29 We extracted data relating to the study setting and context, the experience and attitudes of online users and non-users, clinicians and other healthcare staff, the technologies used and the impact and context of these on the organisation of primary and ambulatory care. Specific data extracted included the study aims/objectives, study design, setting, intervention and key findings. The initial analysis was undertaken by the two principal authors with input and comments from the group members/coauthors. The final synthesis of the data was undertaken at a meeting where data were presented and discussed at a group level.

Applicability

Most of the included studies were undertaken in the USA and Europe; the reviewers included those they considered applicable to countries with comprehensive primary care services.

Results

Excluded papers

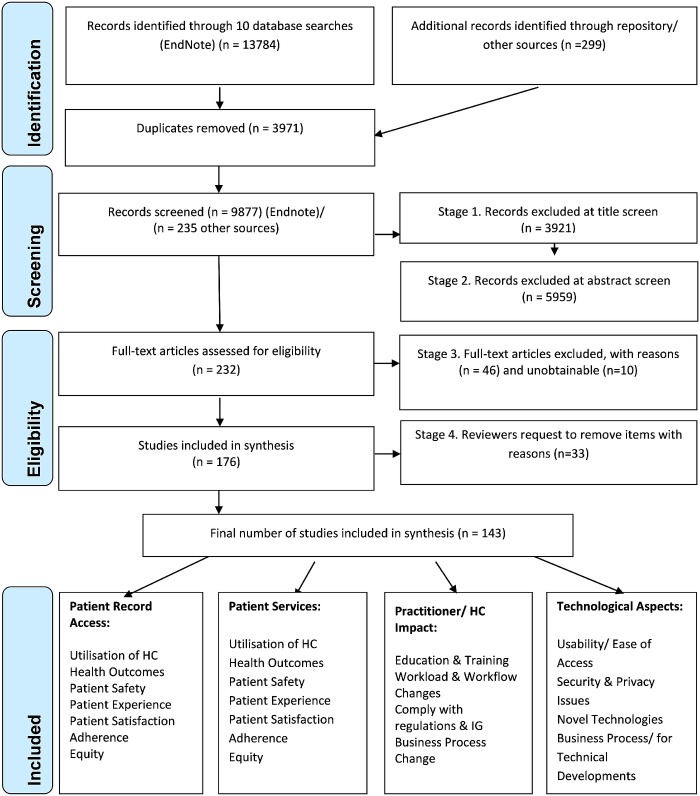

The papers selected by the search process, but rejected by the reviewers largely comprised of studies not considered relevant to the review (see online supplementary table S1—Excluded Studies). Portals, websites, email or other online access for single conditions or diseases, such as diabetes, were excluded. The search and exclusion process is summarised in the PRISMA flowchart (figure 1). Results from these searches were stored using Endnote, and where copyright allowed, in an online repository. There were 3971 duplicate articles. After this initial filter process, 6191 papers remained.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flowchart.

Research Question 1: what is the association between providing patients online access to their own ambulatory care medical record and utilisation of healthcare and outcomes, including patient safety, patient experience and satisfaction, adherence, equity and efficiency?

Patient online access has a low uptake, and the effect on face-to-face utilisation of healthcare was equivocal. Female adults were the largest group of online access and online service users according to 11 papers30–40 (see online supplementary table S2—Research Question 1 Results). Six studies report that some were disadvantaged by lack of access to the internet.41–46 while others reported no such barrier.47 48 Seven papers stated that patients want to be able to appoint a proxy, share records with family or another healthcare professional or be able to print out segments of their records.30 41 49–53

Two papers described the elderly's willingness to accept assistance in accessing their records53 54 and two further studies reported that children's advocates suggest that their guardians should have access to their records up to age 16 years.55 56 However, others have expressed concerns about unauthorised access,57 as misuse or ‘snooping.’58

While online access allows patients to reflect on their records and prepare for the next consultation,59 60 there was no evidence of improved health outcomes.61 62 However, evidence from eight studies indicated that there may be an improvement in patient safety primarily through identifying errors in medication lists and adverse drug reactions.38 49 59 63–67 In one study about the potential to access and identify medication errors, there was significant difference between the number of discrepancies in medication with potential for severe harm in the intervention group compared with controls (0.03 intervention vs 0.08 control per patient, adjusted RR 0.31, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.92, p=0.04).59 There was no evidence of harm to patients from the provision of patient online access, though there were concerns among health professionals that access to unexplained reports may cause anxiety or stress for patients. In eight studies, health professionals were concerned that viewing notes could potentially be offensive to patients or could cause an adverse reactions and this could impact negatively on the doctor–patient relationship.30 41 49 68–72 Patient experience and satisfaction appears to be improved through enabling better self-care (n=13 studies)11 2 30 49 57 60 61 66 72–76 and patients being empowered to communicate more effectively with clinicians (n=13 studies).49 50 51 57 60 68 72 73 77–82

Research Question 2: What is the association between providing patients access to online services as part of their ambulatory care and utilisation of healthcare and outcomes including patient safety, patient experience and satisfaction, adherence, equity and efficiency?

Patients’ access to online services offered greater convenience particularly in time-saving when compared with other methods of interaction with their health provider.30 83–90 Both healthcare professionals and patients reported time-saving in terms of avoiding an in-person clinic visit85 86 and better efficiency in managing patient care91 (see online supplementary table S3—Research Question 2 Results).

Many disadvantaged and vulnerable people were non-users, including non-Caucasian ethnicities46 92 and those of lower socioeconomic status,44 93 94 while adult females were the most active adopters of this technology.32 34–40 Several studies also report disadvantages with access to online technology for other groups, such as those in poorer health and vulnerable groups.38 42 45 95 Evidence from four studies reported that patients wanted direct communication with their clinician96–98 while evidence from three studies suggested that clinicians preferred support staff to filter messages.70 90 99 Patients satisfaction also improved if clinicians responded in a timely manner to their requests (10 studies).37 65 71 82 92 96 100–103

The EHR linked services most utilised by patients were: prescriptions, viewing the test results, messaging with their clinician, arranging referrals and rescheduling appointments.14 30 35 52 87 89 90 96 104–109 Generally, email contacts from patients were brief, well structured and about non-urgent minor problems.75 82 87 89 100 110–112 Seven studies reported that patient access to online services facilitated uptake of preventative care services83 95 113–116 and four studies reported small improvements in adherence with medication and clinical attendance.30 36 49 59 Patients also felt more able to express ideas and concerns,82 86 89 95 112 117–119 and 16 studies reported how patient experience and satisfaction was high.37 59 62 75 80 81 85 89 96 97 103 106 112 116 120 121 While patients were positive about online services, a substantial minority (all from studies in the USA) would not be willing to pay for the service, and those that did put a relatively low financial value on the transaction.42 45 92 122 123

Research Question 3: what is the association between patient adoption of online access and online services as part of their ambulatory care and the practitioner and healthcare team being provided with staff training, making workload and workflow changes, achieving regulatory compliance and business process changes?

Most studies identified reported levels of patient adoption of online access and services without clear reference to the impact of training (see online supplementary table S4—Research Question 3 Results). These are reported here to describe the extent of the existing evidence base. There are more reports about the effect on workload and workflow, though largely on the interrelationship between providing online access to records, email (or messaging via a portal), telephone use and face-to-face consulting.

Five studies commented on the clinicians’ use of email to communicate with their patients, with only a small number of clinicians, between 3% and 17%, being regular users.43 109 120 124 125 Four papers described patient requests for clinical advice online37 39 82 110; and many more described other EHR linked services, such as repeat prescribing and administering bookings.65 88 89 100 105 107 115 126 However, some clinicians preferred sharing their mobile phone number to providing their email address.124

Simple self-limiting problems were readily manageable by email36 37 45 82 83 88 100 106 108 110 but more complex problems were not.87 96 Overall use was judged by clinicians to be appropriate with a minority of e-consultations resulting in a subsequent face-to-face encounter (n=3 studies).34 85 110 After an early peak in email volume there is some evidence that the level falls back.127 Only two papers reported that healthcare professionals felt that they lacked the skills to use these technologies121 128 and wanted more training.120 129–133 Some were concerned about the effect of providing online access and services on workload134–136; there seems to be a complex interdependency between face-to-face, online messaging or email and telephone utilisation. Seven studies reported an increase in workload33 43 49 97 108 132 126; two reported a large but temporary increase that plateaued,71 106 and eight reported a decline.57 62 71 72 85 102 108 137

Online access and services has an inconsistent effect on face-to-face consultations across studies, with some reporting a decline62 102 108 111 137 (n=5), an increase33 49 106 (n=3) or no change (n=3).57 101 102 Generally, email and web-messaging created new and increased volumes of contacts,62 81 105 106 108 126 132 137 though four studies reported no change.88 94 120 138 Telephone contact appeared to rise and fall back when new services were offered,71 106 though six studies reported no change in telephone volume,88 94 97 101 102 126 and three reported a rise.33 108 136

Online services were perceived as fundamentally changing the business process. There was a perception that there needed to be a reorganisation of working practices.71 76 90 139 Clinicians felt they needed to change the way that they wrote their medical records as they were now shared with their patients rather than using them as largely private professional aide memoire.72 The nature of communication was felt to change in that email communication was led to a greater extent by the patient than happened in face-to-face contact; possibly, online access facilitates a subtle shift in the balance of power in the clinical consultation.70 98 116 127

Research Question 4: What is the association between IT developments, and the business process for developing modified systems and patient adoption and utilisation of online access and online services provided as part of the patient's ambulatory care computerised medical record?

Eight studies reported formalised systems to ensure governance and compliance with other relevant regulations,53 90 100 106 115 120 124 126 140 but there was a lack of knowledge about what made an appropriate framework76 140–142; and other studies reported a need for future guideline development58 72 90 96 143–145 (see online supplementary table S5—Research Question 4 Results).

Several studies (n=16) also highlighted clinicians’ concerns about privacy and confidentiality.43 51 58 67 77 82–84 98 105 111 121 138 146–148 Patients in one study expressed willingness to trade-off security for ease of access.115 Clinicians reported in three papers that they preferred controlled access via a portal, authenticating users and ensuring privacy.67 130 142 Incorporating a fee for service appears to be highly effective in promoting clinician uptake of online services; some organisations have experimented with incorporating a fee, but this practice is not widespread, especially among large organisations having the most experience (such as Kaiser, VHA and most health systems in the USA and in Europe).86 149

Seven studies outlined a number of novel technologies that had been introduced including providing links to X-ray and scan images34 70 98; automated test result tracking,80 text messaging question and answer service125; portals that use a code number or pictures of medications to avoid medication names being displayed41; and web-based triage.36 Many of the portals were carefully designed to deliver full or partial online access87 96 and some required complex technical development linking different systems, for example to provide access to pathology results and X-ray reports or images.70 98 Despite the level of technical innovation, 10 studies report often lower than anticipated levels of patient uptake.35 36 53 74 99 105 109 114 150 151

Discussion

Statement of principal findings

Patients generally report benefits of greater access; however, there was a lack of evidence of improvement in health outcomes. However, clinicians in several studies (n=8) feared access to records, or reports without a clinician available to interpret them may cause patients worry. Further research is needed to report whether any harm or privacy breaches occur as a consequence of online access.

Providing online access generally lowers the threshold for patient–clinician contact and can change the nature of their interaction. The medical record changes from being an aide memoire for clinicians to an opportunity for patients to learn about their condition and reflect on the questions they might wish to ask at their next consultation. This creates opportunities for preventive care and for patients to take the lead in clinical consultations, though this is limited by much of the record being written in a way that is inaccessible to patients.

Technical and contractual developments of business processes are needed to facilitate patient online access; they are important and necessary for success. The technical developments include the development of portals, which provide privacy, and allow monitoring and thereby ensure that messages and responses are recorded and not lost; they also measure workload to facilitate billing or other forms of reimbursement. Contractual processes include ensuring that there is the necessary training and other mechanisms in place to ensure that the service is provided and to a defined standard.

Comparison with the literature

Berwick et al152 described the triple aims of health systems: how to improve the experience of healthcare, reduce per capita cost and improve the health of populations. Online access may improve the experience of healthcare and improve patient satisfaction; it may also be more cost effective if cheap online contacts substituted for more expensive ones, but the change in thresholds of access makes this hard to determine. We do not know the impact on business processes and costs in primary care. Other than correcting medication errors it is yet to be demonstrated how it improves health outcomes and that of the population.

The sociotechnical school describes the implementation of a technology as a journey of mutual transformation of that technology and its users.153 154 The mutual transformation required may has three intertwined themes. First, providing patients with easier online access needs to be done in such a way that it improves convenience, but does not result in multiple interactions about self-limiting conditions (unless getting patients to engage in this way is seen as a goal of the health system). It is plausible that online access might not actually improve health, but reduce efficiency. Second, the nature of the medical record needs to change so that it informs the patient, possibly linked to relevant educational material that might provide greater self-management support. Third, there may be a subtle shift in the balance of authority in the clinical consultation; patients and the technology itself (through reminders and links to information) may increasingly take the lead in the clinical consultation, reinforcing the trend away from clinician-led consultations.155

The chronic care model suggests that a range of components including creating activated patients who improved their self-management support might have better health outcomes156; though there is a suggestion that the most effect is seen in complex cases.157 Implementing self-management support has demonstrated improved health outcomes in specific diseases, for example diabetes158; and computerised self-management support, has also shown benefits.159 Such computerised support might be readily linked to EHRs. However, there is currently no evidence of improved health outcomes from implementing generic self-management support processes160–162; though further trials of self-management support are currently underway.

Implications for research, policy and practice

Quality in healthcare includes improving convenience, satisfaction and patient safety163 164; and online access can contribute to these. However, there is a risk that highly qualified clinicians become less efficient through answering multiple emails and electronic contacts about minor and self-limiting conditions. The business requirements of systems where users pay may be different from the ones where the state or social insurance wants to focus on improved population health outcomes.

There were no reports of harm caused by breaches of privacy; however, there were concerns and calls for further guideline development. The policy of the English NHS to provide online access via computerised medical record systems vendors seems appropriate. However, there may be scope for development of a common specification that might be more usable by patients with more similar functionality provided across the different brands of computer systems.

Call for further research

Research, including well-designed trials, is needed to determine whether and how online services might improve health outcomes. In particular, how the medical record might be redesigned to guide and teach patients in a way that promotes self-management and ultimately improves health. There is also a need for further research concentrating on the impact of online access by patients with specific long-term conditions, such as diabetes, where it is potentially easier to define health outcomes.

Health services need to learn if it is possible to provide ready access without being overwhelmed by requests and questions about potentially self-limiting conditions. Studies are needed to explore whether patient online access to reports and traditional medical records induces anxiety and fosters dependence or reassures, and if so, what needs to be done to mitigate this.

Trials comparing the potential impact of patient online access in more complex cases compared with lower risk cases, possibly including tools to improve self-management support, might provide some insight into where patient access and technology might add most value.

Conclusions

Online access offers patients more convenience, a vehicle for engaging with their healthcare information, and may improve patient safety. These services are currently not widely taken up by patients, nor met with widespread enthusiasm by healthcare professionals, and there is no evidence-base that they improve health outcomes. This review suggests that online access and services are perceived as fundamentally changing the business process of primary care, and with careful development, may be successfully incorporated into clinical workflows. Patient online access is to stay and set to grow, albeit slowly. Health systems may find that, in the short-term, online access reduces efficiency. Record systems may need to change to become more patient-friendly; in the long term this may enable patients to more effectively self-manage and take the lead in consultations about their healthcare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The administration support offered by the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) throughout this study and especially to Richard Haigh for his continuous contribution in co-ordinating the expert reviewers. Georgios Michalakidis for use of the data extraction database and IT/review upload support.

Footnotes

Contributors: http://www.bmj.com/about-bmj/resources-authors/article-submission/authorship-contributorship. SL was the principal investigator, wrote the protocol, involved in the supervision of all aspects of this project and SR milestones and also involved in the supervision of quality assurance processes, contribution to draft versions of this paper, coanalysis with FM, shared writing of all subsequent papers with FM, dissemination and presentation of findings to reviewers. FM was major contributor and wrote the protocol and involved in the development and design of all SR tools/instruments, design of search strings, screening of papers, reviewer/data extraction, writing of evidence tables and all supplementary tables, coanalysis with SL, shared writing of the paper with SL, dissemination and presentation of findings to reviewers, corresponding with all reviewers, and co-ordinating, merging and addressing comments on the draft paper/changes to all drafts. AS involved in the developing the review protocol and critically commenting on drafts of this manuscript. AM involved in the protocol development, reviewer/data extraction, commented on the draft manuscript. JCW involved in the developing the review protocol and critically commenting on drafts of this manuscript. TQ involved in the protocol development, contribution to quality assessment and data extraction, commented on the draft manuscript. MC assisted with search strings/searches, literature screening; paper storing/dissemination to reviewers; editing of paper and evidence tables. TAG reviewed and analysed papers screened for the systematic review and reviewed the draft paper. CF involved in the data extraction and reviewed selected papers, commented on the draft paper. UC reviewer and involved in the data extraction and editing of the manuscript. HB reviewer/involved in the data extraction, revisions and amendment of the protocol, and final approval of the version to be published. NK reviewer/and involved in the data extraction, revisions and amendment of the protocol, and final approval of the version to be published. FB involved in the protocol development, reviewer/data extraction, advised on use of GRADE, commented on the draft manuscript. BE responsible for the planning, conduct, and reporting of the pilot study. PK reviewer/data extraction. TNA participated in the conception and design of the study, participated in the pilot study, conducted reviews, revised critically the article and provided final approval of the version to be published. McC reviewer/data extraction. SJ reviewer/data extraction. IR review of papers. Commissioned the review on behalf of the RCGP.

Funding: This study was supported by the RCGP, and commissioned by the Department of Health.

Competing interests: SdeL: Professor Lusignan has nothing to disclose, though feels it should be noted that this review was partly funded by the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP). They funded this as a component of a larger piece of work developing a Road Map to Online access to medical records. SdeL and IR are among the authors of the Road Map which is available online at http://www.rcgp.org.uk/patientonline The systematic review was Working Group 7 of this larger review, details are available online at: http://www.clininf.eu/projects/patient-access.html The Road Map is cited as reference No. 17. The source of funding to the RCGP was Department of Health. BE: Dr Ellis reports other funding from Royal College of General Practitioners during the conduct of the study; and BCS CITP Member of Primary Health Care Specialist Group. BE also contributed to the RCGP Road Map (reference 17). SdeL and IR are co-authors of the RCGP Road Map (ref. 17).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Online supplementary table S1, detailing excluded studies, is available on request by emailing Freda.mold@surrey.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Carman D, Britten N. Confidentiality of medical records the patients's perspective. Br J Gen Pract 1995;45:485–8 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mandl KD, Szolovits P, Kohane IS. Public standards and patients’ control: how to keep electronic medical records accessible but private. BMJ 2001;322:283–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wiljer D, Urowitz S, Apatu E, et al. Canadian committee for patient accessible health records. Patient accessible EHR: exploring recommendations for successful implementation strategies. J Med Internet Res 2008;10:e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tiik M. Rules and access rights of the Estonian integrated e-Health system. Stud Health Technol Inform 2010;156:245–56 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pearce C, Bainbridge M. A personally controlled electronic health record for Australia. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2014;21:707–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beard L, Schein R, Morra D, et al. The challenges in making EHR accessible to patients. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2012;19:116–20 http://jamia.bmj.com/content/early/2011/11/25/amiajnl-2011–000261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cross M. BMA warns against letting patients have access to their electronic records. BMJ 2011;342:d206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quantin C, Fassa M, Coatrieux G, et al. Giving patients secure <<Google-like>> access to their medical record. Stud Health Technol Inform 2008;137:61–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gardiner R. The transition from ‘informed patient’ care to ‘patient informed’ care. Stud Health Technol Inform 2008;137:241–56 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rutland CM, Brynhi H, Andersen R, et al. Developing a shared electronic health record for patients and clinicians. Stud Health Technol Inform 2008;136:57–62 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hannan A. Providing patients online access to their primary care computerised medical records: a case study of sharing and caring. Inform Prim Care 2010;18:41–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pyper C, Amery J, Watson M, et al. Patients’ experiences when accessing their on-line electronic patient records in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 2004a;54:38–43 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bourgeois FC, Taylor PL, Emans SJ, et al. Whose personal control? Creating private, personally controlled health records for pediatric and adolescent patients. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2008;15:737–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silvestre AL, Sue VM, Allen JY. If you build it, will they come? The Kaiser Permanente model of online health care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:334–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nazi KM, Woods SS. MyHealtheVet PHR: a description of users and patient portal use. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2008:1182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The Department of Health. The power of information: Putting all of us in control of the health and care information we need p.91. 2012. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/213689/dh_134205.pdf (accessed 19 Sep 2013).

- 17.Morris L, Milne B. Enabling patients to access EHR guidance for health professionals. London: Royal College of General Practitioners, Record Access Collaborative. Version 1.0, September 2010. http://www.rcgp.org.uk/pdf/Health_Informatics_Enabling_Patient_Access.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rafi I, Morris L, Short P, et al. The road map. London: Royal College of General Practitioners (Clinical Innovation and Research Centre), 2013. http://www.rcgp.org.uk/~/media/Files/CIRC/POA/RCGP-Road-Map.ashx (accessed 29 Dec 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldzweig CL, Towfigh AA, Paige NM, et al. Systematic review: secure messaging between providers and patients, and patients’ access to their own medical record. Evidence on Health Outcomes, Satisfaction, Efficiency and Attitudes, VA-ESP Project #05–226, 2012 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mold F, de Lusignan S, Sheikh A, et al. Patients’ online access to their electronic health records and linked online services: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. In press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins JPT, Deeks JJ, eds. Chapter 7: selecting studies and collecting data. In: Higgins JPT, Green S. eds. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.0.1 [updated September 2008]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2008. http://www.cochrane-handbook.org [Google Scholar]

- 22.EQUATOR Network. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta Analyses (PRISMA). http://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/preferred-reporting-items-for-systematic-reviews-and-meta-analyses-the-prisma-statement/

- 23.Mold F, Ellis B, de Lusignan S, et al. The provision and impact of online patient access to their electronic health records (EHR) and transactional services on the quality and safety of health care: systematic review protocol. Inform Prim Care 2012;20:271–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews) Registration Number: CRD42012003091.

- 25.Stillwell SB, Fineout-Overholt E, Melnyk BM, et al. Evidence based practice step by step: Asking the clinical question, a key step in evidence based practice. Am J Nurs 2010;110:58–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schünemann H, Broz.ek J, Oxman A, eds. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendation. Version 3.2 [updated March 2009]. The GRADE Working Group, 2009. http://www.cc-ims.net/gradepro [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:924–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE). GRADE Working Group. http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/

- 29.Sheikh A, McLean S, Cresswell K, et al. The impact of eHealth on the quality and safety of healthcare. An updated systematic overview & synthesis of the literature. NHS Connecting for Health Evaluation Programme, 2011. http://www.birmingham.ac.uk/Documents/collegemds/haps/projects/cfhep/projects/001Extension/CFHEP001FinalReport-March2011.pdf [accessed 3 Dec 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhavnani V, Fisher B, Winfield M, et al. How patients use access to their electronic GP record: a quantitative study. Fam Pract 2010;28:188–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goel MS, Brown TL, Williams A, et al. Patient reported barriers to enrolling in a patient portal. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2011; 18(Suppl 1):i8–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hassol A, Walker JM, Kidder D, et al. Patient experiences and attitudes about access to a patient electronic health care record and linked web messaging. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2004;11:505–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palen TE, Colleen Ross J, Powers D, et al. Association of online patient access to clinicians and medical records with use of clinical services. JAMA 2012;308:2012–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adamson SC, Bachman JW. Pilot study of providing online care in a primary care setting. Mayo Clin Proc 2010;85:704–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fung V, Ortiz E, Huang J, et al. Early experiences with e-health services (1999–2002): promise, reality, and implications. Med Care 2006;44:491–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nijland N, Cranen K, Boer H, et al. Patient use and compliance with medical advice delivered by a web-based triage system in primary care. J Telemed Telecare 2010;16:8–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Padman R, Shevchik G, Paone S, et al. eVisit: a pilot study of a new kind of healthcare delivery. Stud Health Technol Inform 2010;160(Pt 1):262–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ralston JD, Rutter CM, Carrell D, et al. Patient use of secure electronic messaging within a shared medical record: a cross-sectional study. J Gen Intern Med 2009;24:349–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Umefjord G, Sandstrom H, Malker H, et al. Medical text-based consultations on the Internet: a 4-year study. Int J Med Inform 2008;77:114–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wakefield DS, Kruse RL, Wakefield BJ, et al. Consistency of patient preferences about a secure internet-based patient communications portal: contemplating, enrolling, and using. Am J Med Qual 2012;27:494–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haggstrom DA, Saleem JJ, Russ AL, et al. Lessons learned from usability testing of the VA's personal health record. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2011;18(Suppl 1):i13–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Adler KG. Web portals in primary care: an evaluation of patient readiness and willingness to pay for online services. J Med Internet Res 2006;8:e26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hobbs J, Wald J, Jagannath YS, et al. Opportunities to enhance patient and physician e-mail contact. Int J Med Inform 2003;70:1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kruse RL, Koopman RJ, Wakefield BJ, et al. Internet use by primary care patients: where is the digital divide? Fam Med 2012;44:342–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.LaVela SL, Schectman G, Gering J, et al. Understanding health care communication preferences of veteran primary care users. Patient Educ Couns 2012;88:420–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Virji A, Yarnall KS, Krause KM, et al. Use of email in a family practice setting: opportunities and challenges in patient- and physician-initiated communication. BMC Med 2006;4:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fashner J, Drye ST. Internet availability and interest in patients at a family medicine residency clinic. Fam Med 2011;43:117–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goel MS, Brown TL, Williams A, et al. Disparities in enrollment and use of an electronic patient portal. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26:1112–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Delbanco T, Walker J, Bell SK, et al. Inviting patients to read their doctors’ notes: a quasi-experimental study and a look ahead. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:461–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pyper C, Amery J, Watson M, et al. Access to electronic health records in primary care—a survey of patients’ views. Med Sci Monit 2004b;10:SR17–22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Walker J, Leveille SG, Ngo L, et al. Inviting patients to read their doctors’ notes: patients and doctors look ahead: patient and physician surveys. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:811–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zulman DM, Nazi KM, Turvey CL, et al. Patient interest in sharing personal health record information. A Web-based survey. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:805–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Collins SA, Vawdrey DK, Kukafka R, et al. Policies for patient access to clinical data via PHRs: current state and recommendations. JAMIA 2011;18(Suppl 1):i2–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lober WB, Zierler B, Herbaugh A, et al. Barriers to the use of a personal health record by an elderly population. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2006;514–8 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.National Children's Bureau. Information technology, feedback and health. NCB, Voluntary Sector Support, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 56.National Children's Bureau. Children and young people's views on the ‘NHS: an information revolution’ and local health watch. NCB, Voluntary Sector Support, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pagliari C, Shand T, Fisher B. Embedding online patient record access in UK primary care: a survey of stakeholder experiences. JRSM Short Rep 2012;3:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weitzman ER, Kaci L, Mandl KD. Acceptability of a personally controlled health record in a community-based setting: implications for policy and design. J Med Internet Res 2009;11:e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schnipper JL, Gandhi TK, Wald JS, et al. Design and implementation of a web-based patient portal linked to an electronic health record designed to improve medication safety: the patient gateway medications module. Inform Prim Care 2008;16:147–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fisher B, Bhavnani V, Winfield M. How patients use access to their full health records: a qualitative study of patients in general practice. J R Soc Med 2009;102:539–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Saparova D. Motivating, influencing, and persuading patients through personal health records: a scoping review. Perspect Health Info Manag 2012;9:1f. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Baer D. Patient-physician e-mail communication: the kaiser permanente experience. J Oncol Pract 2011;7:230–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Staroselsky M, Volk LA, Tsurikova R, et al. An effort to improve electronic health record medication list accuracy between visits: patients’ and physicians’ response. Int J Med Inform 2008;77:153–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schnipper JL, Gandhi TK, Wald JS, et al. Effects of an online personal health record on medication accuracy and safety: a cluster-randomized trial. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2012;19:728–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Weingart SN, Hamrick HE, Tutkus S, et al. Medication safety messages for patients via the web portal: the MedCheck intervention. Int J Med Inform 2008;77:161–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Honeyman A, Cox B, Fisher B. Potential impacts of patient access to their electronic care records. Inform Prim Care 2005;13:55–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lehnbom EC, McLachlan A, Brien JA. Qualitative study of Australians’ opinions about personally controlled electronic health records. Stud Health Technol Inform 2012;178:105–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ross SE, Todd J, Moore LA, et al. Expectations of patients and physicians regarding patient-accessible medical records. J Med Internet Res 2005;7:e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Steinschaden T, Petersson G, Astrand B. Physicians’ attitudes towards eprescribing: a comparative web survey in Austria and Sweden. Inform Prim Care 2009;17:241–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Johnson AJ, Frankel RM, Williams LS, et al. Patient access to radiology reports: what do physicians think? J Am Coll Radiol 2010;7:281–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liederman EM, Lee JC, Baquero VH, et al. Patient-physician web messaging: the impact on message volume and satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med 2005;20:52–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Delbanco T, Walker J, Darer JD, et al. Open notes: doctors and patients signing on. Ann Intern Med 2010;153:121–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wagner PJ, Howard SM, Bentley DR, et al. Incorporating patient perspectives into the personal health record: implications for care and caring. Perspect Health Inf Manag 2010;7:1e. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Greenhalgh T, Hinder S, Stramer K, et al. Adoption, non-adoption, and abandonment of a personal electronic health record: case study of HealthSpace. BMJ 2010;340:c3111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Umefjord G, Hamberg K, Malker H, et al. The use of an Internet-based Ask the Doctor service involving family physicians: evaluation by a web survey. Fam Pract 2006;23:159–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hanna L, May C, Fairhurst K. Non-face-to-face consultations and communications in primary care: the role and perspective of general practice managers in Scotland. Inform Prim Care 2011;19:17–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.London Connect. What do people think about accessing their records online? Online survey for London Connect: January 2013. London Connect

- 78.Hannan A, Webber F. Towards a partnership of trust. Stud Health Technol Inform 2007;127:108–16 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Herbert I; Clinical Computing Special Interest Group (CLICSIG) of the Primary Health Care Specialist Group of the British Computer Society. CLICSIG report: patients’ access to medical records. Report of the meeting of the Clinical Computing Special Interest Group (CLICSIG) of the Primary Health Care Specialist Group of the British Computer Society, Cranage, Cheshire, 9 December 2006. Inform Prim Care 2007;15:57–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Matheny ME, Gandhi TK, Orav EJ, et al. Impact of an automated test results management system on patients’ satisfaction about test result communication. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:2233–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tufano JT, Ralston JD, Martin DP. Providers’ experience with an organizational redesign initiative to promote patient-centered access: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23:1778–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ye J, Rust G, Fry-Johnson Y, et al. E-mail in patient-provider communication: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns 2010;80:266–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Neinstein L. Utilization of electronic communication (E-mail) with patients at university and college health centers. J Adolesc Health 2000;27:6–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fairhurst K, Sheikh A. Texting appointment reminders to repeated non-attenders in primary care: randomised controlled study. Qual Saf Health Care 2008;17:373–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wallwiener M, Wallwiener CW, Kansy JK, et al. Impact of electronic messaging on the patient-physician interaction. J Telemed Telecare 2009;15:243–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kummervold PE, Trondsen M, Andreassen H, et al. Patient-physician interaction over the internet. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2004;124:2633–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tang PC, Black W, Young CY. Proposed criteria for reimbursing eVisits: content analysis of secure patient messages in a personal health record system. Annual Symposium proceedings/AMIA Symposium. AMIA Symposium 2006:764–8 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Houston TK, Sands DZ, Nash BR, et al. Experiences of physicians who frequently use e-mail with patients. Health Commun 2003;15:515–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Anand SG, Feldman MJ, Geller DS, et al. A content analysis of e-mail communication between primary care providers and parents. Pediatrics 2005;115:1283–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Conference Board of Canada. Valuing time saved: assessing the impact of patient time saved from the adoption of consumer health solutions. Ottawa, Canada, 2012. http://www.troymedia.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/ValuingTimeSaved.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 91.Walters B, Barnard D, Paris S. Patient portals and E-Visits. J Ambul Care Manage 2006;29:222–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wald JS. Variations in patient portal adoption in four primary care practices. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2010;2010:837–41 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Swartz SH, Cowan TM, Batista IA. Using claims data to examine patients using practice-based Internet communication: is there a clinical digital divide? J Med Internet Res 2004;6:e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Couchman GR, Forjuoh SN, Rascoe TG, et al. E-mail communications in primary care: what are patients’ expectations for specific test results? Int J Med Inform 2005;74:21–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Miller EA, West DM. Where's the revolution? Digital technology and health care in the internet age. J Health Polit Policy Law 2009;34:261–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lin CT, Wittevrongel L, Moore L, et al. An Internet-based patient-provider communication system: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2005;7:e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Smith KD, Merchen E, Turner CD, et al. Patient-physician e-mail communication revisited a decade later: an OKPRN study. J Okla State Med Assoc 2009;102:291–3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Moyer CA, Stern DT, Dobias KS, et al. Bridging the electronic divide: patient and provider perspectives on e-mail communication in primary care. Am J Manag Care 2002;8:427–33 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Katz SJ, Nissan N, Moyer CA. Crossing the digital divide: evaluating online communication between patients and their providers. Am J Manag Care 2004;10:593–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Caffery LJ, Smith AC. A literature review of email-based telemedicine. Stud Health Technol Inform 2010;161:20–34 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Couchman GR, Forjuoh SN, Rascoe TG. E-mail communications in family practice: what do patients expect? J Fam Pract 2001;50:414–18 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.White CB, Moyer CA, Stern DT, et al. A content analysis of e-mail communication between patients and their providers: patients get the message. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2004;11:260–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Liederman EM, Morefield CS. Web messaging: a new tool for patient-physician communication. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2003;10:260–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bergmo TS, Kummervold PE, Gammon D, et al. Electronic patient-provider communication: will it offset office visits and telephone consultations in primary care? Int J Med Inform 2005;74:705–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Flynn D, Gregory P, Makki H, et al. Expectations and experiences of eHealth in primary care: a qualitative practice-based investigation. Int J Med Inform 2009;78:588–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Grover F, Jr, Wu HD, Blanford C, et al. Computer-using patients want Internet services from family physicians. J Fam Pract 2002;51:570–2 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Patt MR, Houston TK, Jenckes MW, et al. Doctors who are using e-mail with their patients: a qualitative exploration. J Med Internet Res 2003;5:e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Byrne JM, Elliott S, Firek A. Initial experience with patient-clinician secure messaging at a VA medical center. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2009;16:267–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Gaster B, Knight CL, DeWitt DE, et al. Physicians’ use of and attitudes toward electronic mail for patient communication. J Gen Intern Med 2003;18:385–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zhou YY, Garrido T, Chin HL, et al. Patient access to an electronic health record with secure messaging: impact on primary care utilization. Am J Manag Care 2007;13:418–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Goodyear-Smith F, Wearn A, Everts H, et al. Pandora's electronic box: GPs reflect upon email communication with their patients. Inform Prim Care 2005;13:195–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Albert SM, Shevchik GJ, Paone S, et al. Internet-based medical visit and diagnosis for common medical problems: experience of first user cohort. Telemed J E Health 2011;17:304–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Nagykaldi Z, Aspy CB, Chou A, et al. Impact of a Wellness Portal on the delivery of patient-centered preventive care. JABFM 2012;25:158–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Szilagyi PG, Adams WG. Text messaging: a new tool for improving preventive services. JAMA 2012;307:1748–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wright A, Poon EG, Wald J, et al. Randomized controlled trial of health maintenance reminders provided directly to patients through an electronic PHR. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27:85–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Car J, Sheikh A. Email consultations in health care: 1–scope and effectiveness. BMJ 2004a;329:435–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Tjora A, Tran T, Faxvaag A. Privacy vs usability: a qualitative exploration of patients’ experiences with secure internet communication with their general practitioner. J Med Internet Res 2005;7:e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Roter DL, Larson S, Sands DZ, et al. Can e-mail messages between patients and physicians be patient-centered? Health Commun 2008;23:80–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Andreassen HK, Trondsen M, Kummervold PE, et al. Patients who use e-mediated communication with their doctor: new constructions of trust in the patient-doctor relationship. Qual Health Res 2006;16:238–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Neville RG, Marsden W, McCowan C, et al. Email consultations in general practice. Inform Prim Care 2004a;12:207–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Car J, Sheikh A. Email consultations in health care: 2–acceptability and safe application. BMJ 2004b;329:439–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Rutland J, Marie C, Rutland B. A system for telephone and secure email consultations, with automatic billing. J Telemed Telecare 2004;10(Suppl 1):88–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Bergmo TS, Wangberg SC. Patients’ willingness to pay for electronic communication with their general practitioner. Eur J Health Econ 2007;8:105–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Brooks RG, Menachemi N. Physicians’ use of email with patients: factors influencing electronic communication and adherence to best practices. J Med Internet Res 2006;8:e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Peleg R, Avdalimov A, Freud T. Providing cell phone numbers and email addresses to patients: the physician's perspective. BMC Res Notes 2011;4:76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Neville RG, Reed C, Boswell B, et al. Early experience of the use of short message service (SMS) technology in routine clinical care. Inform Prim Care 2008;16:203–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Katz SJ, Moyer CA, Cox DT, et al. Effect of a triage-based e-mail system on clinic resource use and patient and physician satisfaction in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med 2003;18:736–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Hart A, Henwood F, Wyatt S. The role of the internet in patient-practitioner relationships: findings from a qualitative research study. J Med Internet Res 2004;6:e36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Umefjord G, Malker H, Olofsson N, et al. Primary care physicians’ experiences of carrying out consultations on the internet. Inform Prim Care 2004;12:85–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Nijland N, van Gemert-Pijnen JE, Boer H, et al. Increasing the use of e-consultation in primary care: results of an online survey among non-users of e-consultation. Int J Med Inform 2009;78:688–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Allaert FA, Le Teuff G, Quantin C, et al. The legal acknowledgement of the electronic signature: a key for a secure direct access of patients to their computerised medical record. Int J Med Inform 2004;73:239–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Wakefield DS, Mehr D, Keplinger L, et al. Issues and questions to consider in implementing secure electronic patient-provider web portal communications systems. Int J Med Inform 2010;79:469–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Chew-Graham CA, Alexander H, Rogers A. The exceptional potential of the Internet?: perceptions about the management of another set of communications: a qualitative study. Primary Health Care Research and Development 2005;6:311–19 [Google Scholar]

- 134.Leveille SG, Walker J, Ralston JD, et al. Evaluating the impact of patients’ online access to doctors’ visit notes: designing and executing the OpenNotes project. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2012;12:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Wald JS, Middleton B, Bloom A, et al. A patient-controlled journal for an electronic medical record: issues and challenges. Stud Health Technol Inform 2004;107(Pt 2):1166–70 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Wald JS, Pedraza LA, Reilly CA, et al. Requirements development for a patient computing system. Proc AMIA Symp 2001:731–5 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Chen C, Garrido T, Chock D, et al. The Kaiser Permanente electronic health record: transforming and streamlining modalities of care. Health Affairs 2009;28:323–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Neville RG, Marsden W, McCowan C, et al. A survey of GP attitudes to and experiences of email consultations. Inform Prim Care 2004b;12:201–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Hayes G. The NHS information technology (IT) and social care review 2009: a synopsis. Inform Prim Care 2010;18:81–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Williams PAH. When trust defies common security sense. Health Informatics J 2008;14:211–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Nijland N, van Gemert-Pijnen J, Boer H, et al. Evaluation of internet-based technology for supporting self-care: problems encountered by patients and caregivers when using self-care applications. J Med Internet Res 2008;10:e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Chhanabhai P, Holt A, Hunter I. Health care consumers, security and electronic health records. Health Care and Informatics Review Online (formerly Healthcare Review Online) 2006;10 [Google Scholar]

- 143.Huba N, Zhang Y. Designing patient-centered personal health records (PHRs): health care professionals’ perspective on patient-generated data. J Med Syst 2012;36:3893–905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Mynors G, Newsom-Davis E. Patient information forum, guide to health records access. London: Patient Information Forum, 2012. http://www.pifonline.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/pif-phr-guide-web_final_Oct12.pdf (accessed 28 Nov 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 145.Hwang HG, Han HE, Kuo KM, et al. The differing privacy concerns regarding exchanging electronic medical records of internet users in Taiwan. J Med Syst 2012;36:3783–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Medical Protection Society. Online medical records and the doctor-patient partnership MPS research report. London, MPS, 2013. Ref:MPS1545:04/13. http://www.medicalprotection.org/Default.aspx?DN=df8411aa-6063-4a5d-b81c-1038d6e824ae. [Google Scholar]

- 147.Kittler AF, Wald JS, Volk LA, et al. The role of primary care non-physician clinic staff in e-mail communication with patients. Int J Med Inform 2004;73:333–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.London Connect. Patients’ and commissioners’ views of personalised health information. Rapid review of key research: September 2012. London Connect

- 149.Komives EM. Clinician-patient E-mail communication: challenges for reimbursement. N C Med J 2005;66:238–40 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.North F, Hanna BK, Crane SJ, et al. Patient portal doldrums: does an exam room promotional video during an office visit increase patient portal registrations and portal use? J Am Med Inform Assoc 2011;18(Suppl 1):i24–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Sciamanna CN, Rogers ML, Shenassa ED, et al. Patient access to U.S. physicians who conduct internet or e-mail consults. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:378–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27:759–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Berg M. Implementing information systems in health care organizations: myths and challenges. Int J Med Inform 2001;64:143–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.de Lusignan S, Morris L, Hassey A, et al. Giving patients online access to their records: opportunities, challenges, and scope for service transformation. Br J Gen Pract 2013;63:286–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Pearce C, Kumarpeli P, de Lusignan S. Getting seamless care right from the beginning—integrating computers into the human interaction. Stud Health Technol Inform 2010;155:196–202 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA 2002;288:1775–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Miller CJ, Grogan-Kaylor A, Perron BE, et al. Collaborative chronic care models for mental health conditions: cumulative meta-analysis and metaregression to guide future research and implementation. Med Care 2013;51:922–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Siminerio L, Ruppert KM, Gabbay RA. Who can provide diabetes self-management support in primary care? Findings from a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Educ 2013;39:705–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.van Gaalen JL, Beerthuizen T, van der Meer V, et al. ; SMASHING Study Group. Long-term outcomes of internet-based self-management support in adults with asthma: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2013;15:e188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Franek J. Self-management support interventions for persons with chronic disease: an evidence-based analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser 2013;13:1–60 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Crowley MJ, Powers BJ, Olsen MK, et al. The Cholesterol, Hypertension, And Glucose Education (CHANGE) study: results from a randomized controlled trial in African Americans with diabetes. Am Heart J 2013;166:179–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Kennedy A, Bower P, Reeves D, et al. Salford National Institute for Health Research Gastrointestinal programme Grant Research Group. Implementation of self management support for long term conditions in routine primary care settings: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2013;346:f2882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Department of Health High Quality Care for All. NHS Next Stage Review Final Report. London, June 2008;47. http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_085828.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 164.Department of Health. The NHS outcomes framework 2012/13. London: Department of Health, 2011:5 http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/documents/digitalasset/dh_131723.pdf [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.