Abstract

Metastasis is a major factor responsible for mortality in breast cancer patients. Inhibitor of DNA binding 1 (Id1) has been shown to play an important role in cell differentiation, tumor angiogenesis, cell invasion and metastasis. Despite the data establishing Id1 as a critical factor for lung metastasis in breast cancer, the pathways and molecular mechanisms of Id1 functions in metastasis remains to be defined. Here we show that Id1 interacts with TFAP2A to suppress S100A9 expression. We show that expression of Id1 and S100A9 is inversely correlated in both breast cancer cell lines and clinical samples. We also show that the migratory and invasive phenotypes in vitro and metastasis in vivo induced by Id1 expression is rescued by reestablishment of S100A9 expression. S100A9 also suppresses the expression of known metastasis promoting factor RhoC activated by Id1 expression. Our results suggest that Id1 promotes breast cancer metastasis by the suppression of S100A9 expression.

Implications: Novel pathways by Id1 regulation in metastasis.

Introduction

Metastasis is a major cause of breast cancer patient death (1–9). Id1 (inhibitor of differentiation/DNA binding 1) has been found to play critical roles in breast cancer lung metastasis (10–13). Id1 is a member of Id helix-loop-helix (HLH) transcription factor family (14–24). HLH transcription factors contain a highly conserved HLH domain which mediates homo or hetero-dimerization (14, 20, 24). Most HLH proteins, except for the Id family proteins, also contain a highly basic DNA-binding region adjacent to HLH domain (14, 20, 24). Id transcription factors do not bind DNA but instead regulate gene expression by dimerization with other transcription factors including both HLH and non-HLH proteins (14, 20, 24). Although most HLH proteins positively regulate gene expression, Id family proteins serve as dominant negative regulators of gene expression (14–24) and play important roles in cell development including cell differentiation and cell fate determination (19, 22–24). In addition, Id family proteins have also been found to be involved in tumor development (14–18, 20–22). Id1 has been shown to immortalize rodent fibroblasts with Bcl-2 (25). Down-regulation of Id2 promotes metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma (26) and Id1 and Id3 are required for tumor angiogenesis and vascularization in mouse models (27). Id1 overexpression in mammary epithelial cells and breast cancer cells promotes cell invasion and lung metastasis in breast cancer (10–13, 28) while down-regulation of Id1 expression decreases breast cancer cell invasion and metastasis (29, 30), thus making Id1 also a cancer therapeutic target (18, 29, 31–33). Id1 expression has been shown to be regulated by multiple transcription factors including sex steroid hormones and the NF-1/Rb/HDAC-1 transcription repressor complex in breast cancer cells (13, 34, 35). Despite the important functions of Id1 in cancer development, the gene expression and molecular pathways regulated by Id1 in metastasis has not been determined.

We have previously shown that metastasis suppressor KLF17 suppresses Id1 expression in breast cancer (36). Knockdown of KLF17 activates Id1 expression and cell invasion and metastasis (36). However, the molecules and pathways downstream of Id1 that mediate metastasis function are unknown. Although small molecules and peptides have been found to suppress Id1 functions (37–40), both KLF17 and Id1 are transcription factors and considered difficult to target directly. Thus it is critical to elucidate the genes and pathways that are regulated by Id1 and may mediate its metastasis-promoting functions. In this study, we show Id1 promotes metastasis to the lung by suppression of S100A9 expression.

Materials and Methods

Transwell migration and invasion assay

In vitro cell migration assays were performed as described previously (36, 41) using Trans-well chambers (8μM pore size; Costar). Cells were allowed to grow to subconfluency (~75–80%) and were serum-starved for 24 h. After detachment with trypsin, cells were washed with PBS, resuspended in serum-free medium and 250 μl cell suspensions (2 × 105 cells ml–1) was added to the upper chamber. Complete medium was added to the bottom wells of the chambers. The cells that had not migrated were removed from the upper face of the filters using cotton swabs, and the cells that had migrated to the lower face of the filters were fixed with 5% glutaraldehyde solution and stained with 0.5% solution of Toluidine Blue in 2% sodium carbonate. Images of three random ×10 fields were captured from each membrane and the number of migratory cells was counted. The mean of triplicate assays for each experimental condition was used. Similar inserts coated with Matrigel were used to determine invasive potential in the invasion assay.

Lentivirus transfection and transduction

To generate MCF7 cells stably overexpressing ID1, ID2, and S100A9, respective full length human cDNAs were cloned into lentiviral vector. Lentiviruse was produced by co-transfecting subconfluent human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells with cDNA expression plasmid and packaging plasmids pMDLg/pRRE and RSV-Rev) using Lipifectamine 2000. Infectious lentiviruses were collected 48 h after transfection, centrifuged to remove cell debris and filtered through 0.45 μm filters (Millipore). MCF7 cells were transduced with the lentiviruses. Efficiency of overexpression was determined by realtime PCR. MCF7-ID1 cells stably expressing RhoC shRNA or control nontarget shRNA and MDA-MB-436 cells stably expressing Id1 shRNA or a control shRNA were established using vector based shRNA technique. shRNAs were cloned in pLKO lentiviral vector and purchased from Sigma. The lentiviruses were processed as described above, transduced into respective cell lines and clones were selected. The knockdown efficiency was determined by western blot.

Tumor transplantation in mice

The MCF7 human breast cancer cell line stably expressing Firefly Luciferase gene with ID1 or ID2 or ID1+S100A9 and MDA-MB-436 cells stably expressing Firefly Luciferase gene with Id1 shRNA or a control shRNA were routinely maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). For orthotopic injections, 0.5 X 106 cells/mouse were transplanted into the mammary fat pad of the female NOD/SCID mice (6–8 weeks old). A slow-release pellet of 17β-estradiol (1.7 mg, 90-day release; Innovative Research of America, Sarasota, FL) was implanted subcutaneously in the dorsal interscapular region before the transplantation of MCF7 cells. For IV injections, 1 X 106 cells/mouse were injected into the lateral tail veins of 6–8 weeks old NOD/SCID mice. Mice bearing luciferase positive tumors were imaged by IVIS 200 Imaging system (Xenogen Corporation, Hopkinton, MA). Mice were sacrificed and their lungs were dissected and imaged. Bioluminescent flux (Photons/sec/sr/cm2) was determined for the primary tumors or lung metastasis 4 weeks post-transplantation. Animal experiment protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Wistar Institute. Animal procedures were conducted in compliance with the IACUC.

Immunoblotting

Standard methods were used for western blotting. Cells were lysed with lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM EGTA pH 8.0, 50 mM sodium fluoride, 1 mM sodium vanadate and 10 mM sodium pyrophosphate with complete protease inhibitor (Roche) and total protein contents were determined by the Bradford method. 30 μg of proteins were separated using 4–12% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to PVDF membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Membranes were incubated over night at 4°C with specific primary antibodies. Blots were washed and probed with respective secondary peroxidase-conjugated antibodies for 1h at RT, and the bands visualized by chemoluminescence (Amersham Biosciences). The following antibodies were used: mouse monoclonal S100A9 (R&D Systems), rabbit polyclonal RhoC (Cell Signaling Technology), mouse monoclonal β-actin (Sigma -Aldrich), and secondary mouse peroxidase conjugated (GE healthcare).

Cell proliferation assay

To measure the proliferative activity of cells, each group of cells were seeded in 96 well plates at a density of 4 x 103 cells per well in triplicate. Cell proliferation was quantified at Day 0, Day 1, Day 2 and Day 3 with CellTiter 96 AQeous Non-radioactive Cell Proliferation Assay system (Promega) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, cells were incubated with 20μl of MTS/PMS solution for 4 hours at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cell proliferation was then measured at 490 nm using a multi-well plate reader (Wallac Victor, PerkinElmer). Cell growth curves were plotted with OD value vs. time. Three independent experiments were performed.

Immunoprecipitations

For Immunoprecipitation 200μg of total cell lysate was incubated with TFAP2 antibody and protein G sepharose beads (GE healthcare) over night at 4 °C. The beads with bound protein was pelleted and washed six times with lysis buffer once with ice cold PBS. The beads were boiled with 1X SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Five percent input and fifty percent immunoprecipitated proteins were separated using 4–12% SDS-PAGE gels and Western blotting was performed as described above. The following antibodies were used: Rabbit polyclonal ID1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and ChIP grade rabbit polyclonal TFAP2A (Abcam) and secondary rabbit peroxidase conjugated (GE healthcare).

RNA Isolation, reverse transcription and real-time PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from cell lines, frozen primary and metastasis tissues using Trizol total RNA isolation reagent (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer’s specifications and treated with Turbo DNase (Ambion). cDNA was synthesized from total RNA using random hexamers with TaqMan High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems). Gene primers were designed using Primer Express v3.0 Software and real- time PCR was performed using SYBR Select Master Mix (Applied Biosystem). All reactions were carried out on the 7500 Fast Real Time PCR system (Applied Biosystem). The average of three independent analyses for each gene and sample was calculated using the ΔΔ threshold cycle (Ct) method and was normalized to the endogenous reference control gene GAPDH.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Assay

MCF7 cells or MCF7 cells overexpressing ID1 were fixed in 1% formaldehyde at 37 °C for 10 min. Cells were washed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline containing protease inhibitors (1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, and 1 μg/ml pepstatin A), scraped, and centrifuged at 4 °C. Cell pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer and sonicated to shear DNA. After sonication, the lysate was centrifuged and the supernatant was diluted 10 fold with ChIP dilution buffer (0.01% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, and protease inhibitors). Chromatin-protein complexes were immuno-precipitated using anti-TFAP2A, or normal rabbit IgG for overnight at 4 °C with rotation. The immunocomplex was precipitated with protein A/G-agarose and washed sequentially with low salt buffer, high salt buffer, and lithium chloride wash buffer and eluted with elution buffer (1% SDS, 0.1 M NaHCO3, and 200 mM NaCl). Reversal of cross-linking was done by heating at 65 °C overnight in the presence of NaCl. DNA was purified using PureLink PCR Purification kit (Invitrogen Carlsbad, CA). The amount of immunoprecipitated DNA was analyzed in triplicates using TFAP2A binding primer sequence in human S100A9 promoter by real-time PCR on ABI 7500 detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Data were analyzed using the percent input method.

Microarray Data Analysis

Total RNA was extracted using the TRI Reagent (Ambion) method and treated with DNaseI (Fermentas). For microarray analysis RNA quality was determined using the Bioanalyzer (Agilent) and only samples with RIN numbers > 7.5 were used for further studies. Equal amounts of total RNA for each sample (400 ng) were amplified as recommended by Illumina and hybridized to the Human-HT12 v4 human whole genome bead arrays. Illumina GenomeStudio software was used to export expression levels and detection p-values for each probe of each sample. Signal intensity data was quantile normalized and only genes that showed insignificant detection p-value (p>0.05) in all samples were removed from further analysis. The data was submitted to GEO database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) and is available by accession number GSE53847. Unpaired two-tail t-test was used to compare groups and p-value was corrected for multiple testing according to Storey et al. (42). Only genes that were significant in ID1 vs control comparison (at FDR<15%), but were insignificant in ID2 vs control comparison (nominal p>0.05) were considered.

Results

Id1 and Id2 have different functions in metastasis

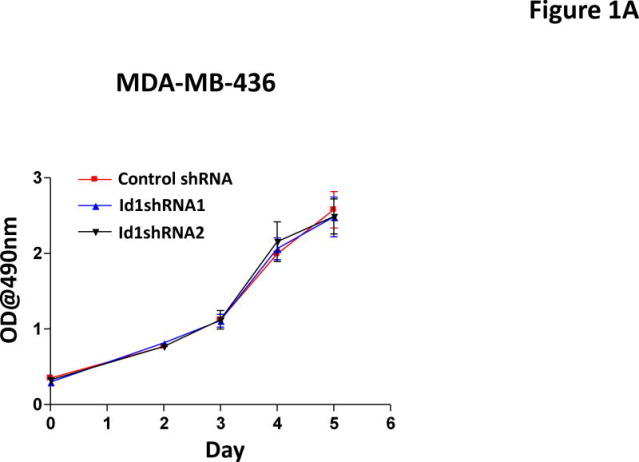

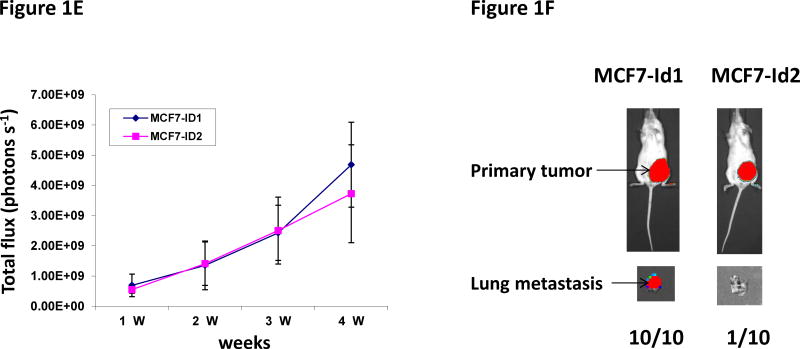

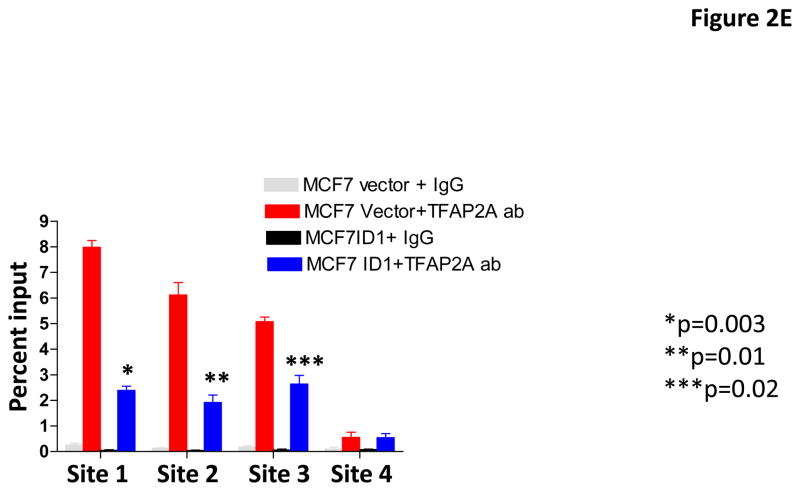

Our previous study has shown that Id1 is directly regulated by metastasis suppressor KLF17 and that knockdown of KLF17 activates Id1 expression and promotes lung metastasis in breast cancer (36). We have also shown that overexpression of Id1 recapitulates the metastasis phenotype induced by KLF17 knockdown (36). Knockdown of Id1 in human breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-436 did not affect cell growth in vitro (Figure 1A), but suppressed cell migration and invasion (Figure 1B–C) in vitro and metastasis in vivo (Figure 1D). In the gene expression profiling analysis of KLF17, we found that the expression of two Id family members, Id1 and Id2, are regulated by KLF17 (36). To test whether Id2 has similar functions as Id1 in metastasis, we generated luciferase-tagged human breast cancer MCF7 cells stably expressing Id2 (Supplementary Figure 1) and transplanted these cells into mice mammary fat pads. The primary tumor growth of cells expressing Id1 or Id2 is similar (Figure 1E). 9 out of 10 mice transplanted with MCF7 cells stably expressing Id2 (Supplementary Figure 1) did not develop any metastasis (Figure 1F) while mice transplanted with Id1-overexpressing cells (Supplementary Figure 1, 2) all (10 out of 10) developed lung metastasis (Figure 1F). These results demonstrated that Id1 and Id2 have different functions in metastasis even though they share sequence similarities in HLH domain and belong to the same family. Thus we hypothesized that genes differentially regulated by Id1 but not by Id2 are potential candidates which functions in breast cancer metastasis.

Figure 1.

Id1 but not Id2 promotes metastasis. (A) Cell growth of MDA-MB-436 cells expressing Id1 shRNAs. Down-regulation of Id1 expression in MDA-MB-436 cells did not affect cell growth. (B–D) Down-regulation of Id1 expression decreased cell migration, invasion and metastasis. MDA-MB-436 cells stably expressing a control shRNA or Id1 shRNA were subjected to migration assay (B) and invasion assay (C). Knockdown of Id1 expression in MDA-MB-436 cells suppressed cell migration and invasion. (D) Transplantation of luciferase-tagged MDA-MB-436 cells stably expressing a control shRNA via tail vein injection led to metastasis (8 out of 10 mice developed lung metastasis), whereas transplantation of MDA-MB-436 cells stably expressing Id1 shRNAs did not (only 1 out of 5 mice in each of the Id1 shRNA group developed metastasis) (Fisher’s exact test p=0.023). Knockdown of Id1 expression in MDA-MB-436 cells suppressed metastasis. (E) Tumor growth in the primary site after the transplantation of human breast cancer MCF7 cells stably expressing Id1 or Id2. There is no significant difference between two groups. (F) Transplantation of MCF7 cells stably expressing Id1 in mammary fat pads leads to metastasis (10 out of 10 mice developed lung metastasis), whereas transplantation of MCF7 cells stably expressing Id2 does not (only 1 out of 10 mice developed lung metastasis) (Fisher’s exact test p<0.001).

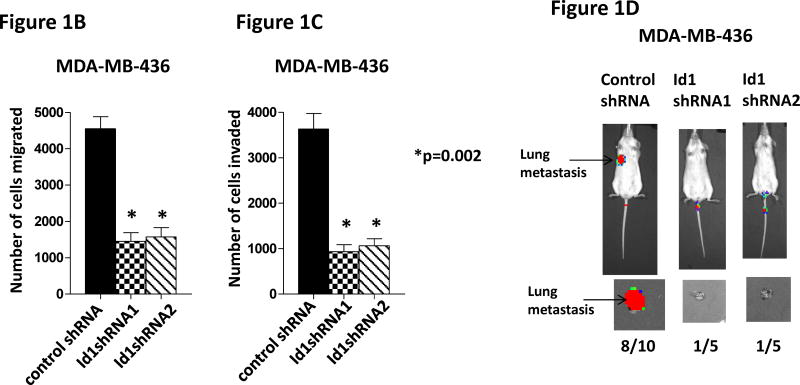

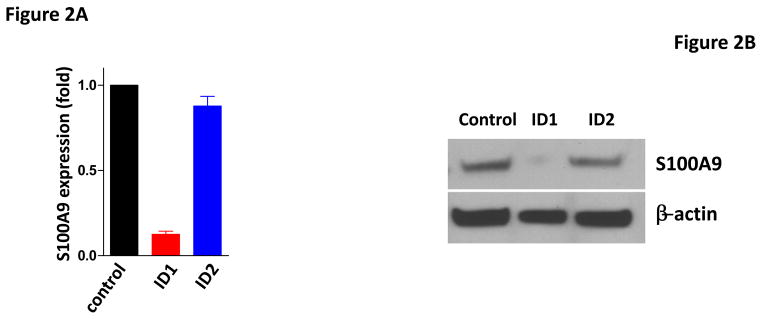

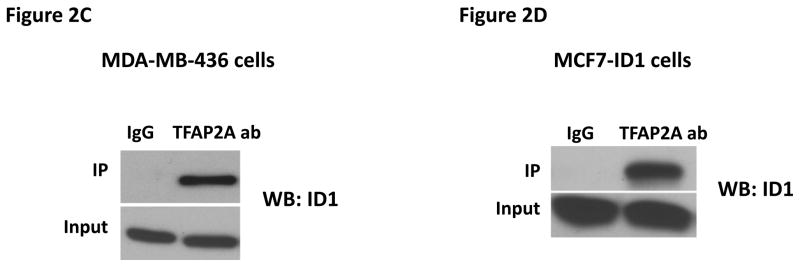

S100A9 expression is regulated by Id1

To identify genes that are regulated by Id1 but not Id2, we performed gene expression profiling analysis in MCF7 cell overexpressing Id1 or Id2 and identified S100A9 as the top gene which expression was suppressed by Id1 but not Id2 (Supplementary Figure 3). S100A9 is a calcium binding protein that plays critical roles in inflammation and cancer development (43, 44). The functions of S100A9 in cancer development are cancer type dependent (45–47). In addition, it has been shown that S100A9 has both tumor-promoting and tumor-suppressive functions in breast cancer (48, 49). To confirm the regulation of S100A9 expression by Id1, we determined the expression level of S100A9 by quantitative RT-PCR and immunoblot in MCF7 cells stably expressing Id1 or Id2. S100A9 expression was suppressed by Id1 at both the transcriptional level and protein level, but not by Id2 (Figure 2A and 2B). Transient transfection of Id1 or Id2 into MCF7 cells also resulted in S100A9 suppression by Id1 but not Id2 (Supplementary Figure 4A–B). Because Id family proteins including Id1 have been shown to serve as negative regulators of gene expression by binding to other transcription factors (14–24), we then scanned the promoter sequence of S100A9 using JASPAR database for potential binding sites for transcription factors that are known to form heterodimers with Id family members bind. We found four potential TFAP2A binding sites (site 1: −351 to −343; site 2: −682 to −674; site 3: −1024 to −863, site 4: −1248 to −1240) in the S100A9 promoter. Co-immunoprecipitation analysis in human breast cancer cell MDA-MB-436 where Id1 is endogenously expressed showed that Id1 interacted with TFAP2A in vivo (Figure 2C). The interaction of Id1 and TFAP2A was further validated in MCF7 cell over-expressing Id1 (Figure 2D). To determine whether TFAP2A directly binds to the S100A9 promoters in vivo, we carried out chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis using control IgG or TFAP2A antibody. Three of the four predicted S100A9 promoter regions with TFAP2A consensus sequences were significantly enriched in TFAP2A antibody as assessed by real time ChIP-PCR as compared with the control IgG (Figure 2E). Overexpression of ID1 decreased the binding of TFAP2A to the S100A9 promoter at site 1, 2 and 3 (Figure 2E). These results demonstrated that Id1 interacts with TFAP2A to suppress S100A9 expression.

Figure 2.

Id1 interacts with TFAP2A to suppress S100A9 expression. (A) Quantitative RT-PCR of S100A9 expression in MCF7 cells expressing a vector control, or Id1, or Id2. (B) Immunoblots of S100A9 expression in MCF7 cells expressing a vector control, or Id1, or Id2. (C) Co-immunoprecipitation of TFAP2A and Id1 in human breast cancer MDA-MB-436 cells expressing Id1 endogenously. Immunoprecipitation using TFAP2A antibody or control IgG was followed by Id1 immunoblotting. (D) Co-immunoprecipitation of TFAP2A and Id1 in MCF7 cells stably expressing Id1. Immunoprecipitation using anti-TFAP2A antibody or control IgG was followed by Id1 immunoblotting. (E) Chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis was performed using an anti-TFAP2A antibody or control IgG in MCF7 cells expressing a vector control or Id1. Three of the four predicted S100A9 promoter regions with TFAP2A consensus sequences showed significant enrichment after immunoprecipitation by an anti-TFAP2A antibody. The enrichment was significantly reduced in site 1, 2 and 3 in MCF7 cells stably expressing Id1.

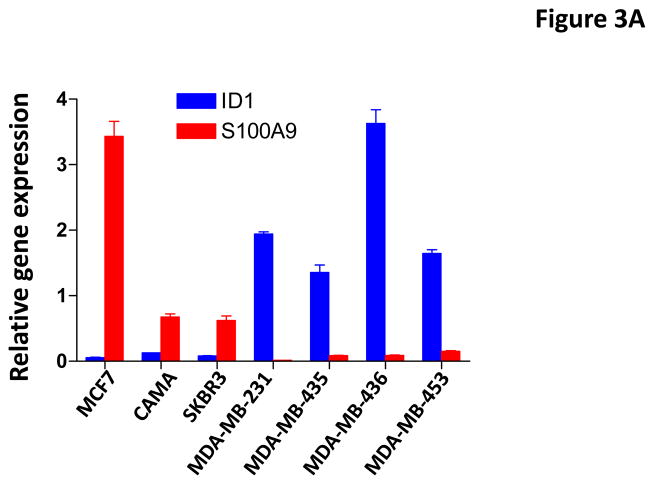

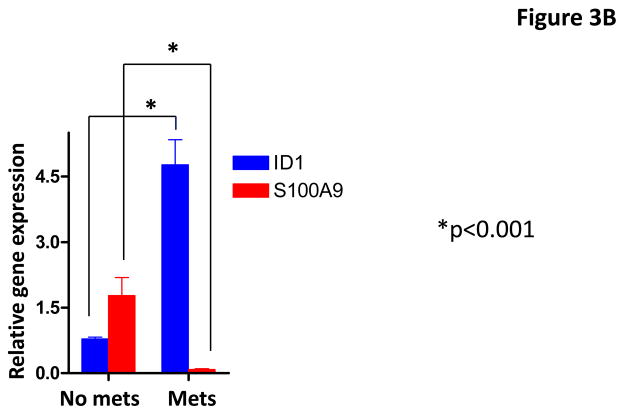

To further validate the regulation of S100A9 by Id1, we examined the expression of S100A9 and Id1 in breast cancer cell lines and primary human breast cancer samples. Spearman’s correlation analysis indicated that the expression of Id1 and S100A9 were inversely correlated in the human breast cancer cell lines (Figure 3A). We then examined the expression of these two genes in primary human breast cancer samples with known lymph node metastasis status. Spearman’s correlation analysis indicated the expression of Id1 and S100A9 were inversely correlated in clinical breast cancer samples (Figure 3B). Wilcoxon rank sum test indicated that the mean Id1 expression was significantly higher in patients with lymph node metastasis than the mean expression in patients without metastases (Figure 3B). In contrast, mean S100A9 expression in patients with lymph node metastasis was significantly lower than the mean expression in patients without metastases (Figure 3B). These results indicated that the expression of Id1 and S100A9 were inversely correlated in both breast cancer cell lines and clinical samples.

Figure 3.

Id1 and S100A9 expression in human breast cancer cell lines and human primary breast cancer samples. (A) Id1 and S100A9 expression in human breast cancer cells were determined by quantitative RT-PCR. Id1 expression is higher in invasive MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-435, MDA-MB-436, MDA-MB-453 cells, but lower in non-invasive MCF7, CAMA and SKBR3 cells. S100A9 expression is higher in non-invasive cells but lower in invasive cells. Pearson correlation analysis indicated that expression of Id1 and S100A9 was inversely correlated (r=−0.78, p=0.038). (B) Id1 and S100A9 expression in 20 human primary breast cancer samples with lymph node metastasis and 21 primary cancer samples with no lymph node metastasis were determined by quantitative RT-PCR. Id1 expression is higher in cancer samples with lymph node metastasis, but lower in cancer samples with no lymph node metastasis. S100A9 expression is higher in cancer samples with no lymph node metastasis, but lower in cancer samples with lymph node metastasis. Pearson correlation analysis indicated that expression of Id1 and S100A9 was inversely correlated (r=−0.79, p<0.001).

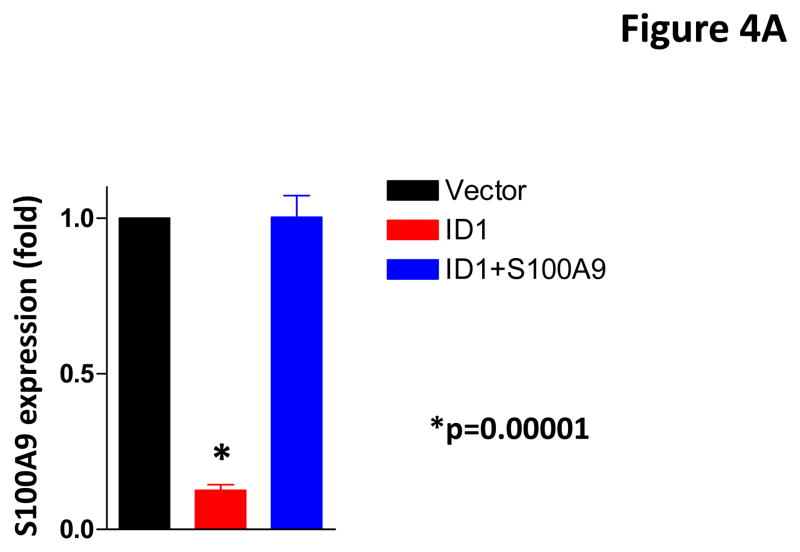

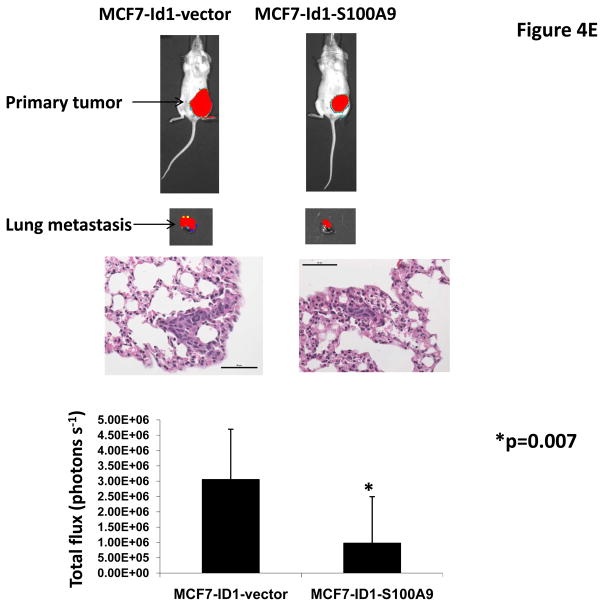

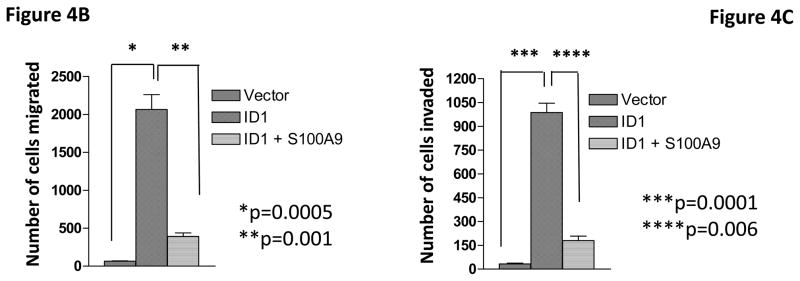

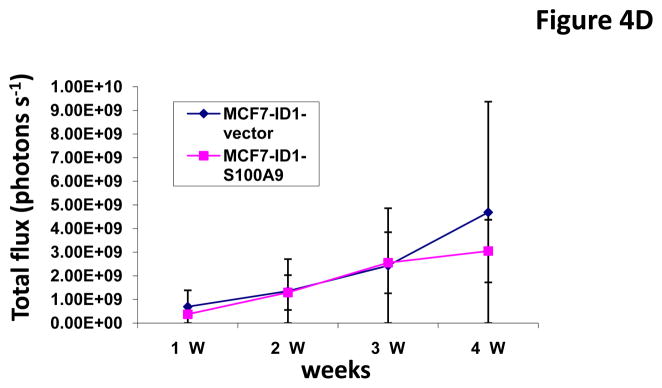

Id1 promotes metastasis by the regulation of S100A9

To determine whether Id1 promotes metastasis by suppressingS100A9 expression, we over-expressed an S100A9 cDNA in MCF7 cells stably expressing Id1. The expression of S100A9 was confirmed by qRT-PCR (Figure 4A). S100A9 abrogated the migratory and invasive phenotypes induced by Id1 in the migration and invasion assays in vitro (Figure 4B and 4C). Transient transfection of Id1 and S100A9 in MCF7 cells led to similar results (Supplementary Figure 5A–C). This was not due to changes in cell growth as S100A9 expression did not affect cell growth in vitro (Supplementary Figure 6). MCF7 cells stably expressing both S100A9 and Id1 were also transplanted into mammary fat pads in mice. The primary tumor growth of S100A9 and Id1 cells was similar, only slightly lower at the 4th week when compared with the growth of cells expressing Id1 alone (Figure 4D). The lung metastasis signals were significantly suppressed in mice with the Id1 and S100A9 double-expressing cells as compared to mice with cells only expressing Id1 (Figure 4E). Taken together, these results indicated that suppression of S100A9 by Id1 is responsible, at least in part, for the observed role of Id1 in promoting metastasis.

Figure 4.

S100A9 mediates the Id1 functions in migration, invasion and metastasis. (A) S100A9 expression in MCF7 cells expressing a vector control, or Id1, or Id1 and S100A9. (B–C) MCF7 cells stably expressing a vector control, or Id1, or Id1 and S100A9 were subjected to migration assay (B) and invasion assay (C). Id1 expression in MCF7 cells increased cell migration and invasion. Expression of S100A9 cDNA reversed migratory and invasive phenotypes induced by Id1 expression (B and C). MCF7 cells stably expressing Id1 and a vector control or Id1 and S100A9 were transplanted into mouse mammary fat pads. The primary tumor growth of these two groups is similar (D). Id1 expression in MCF7 cells promoted lung metastasis. Expression of S100A9 cDNA significantly suppressed the lung metastasis signal induced by Id1 expression (E).

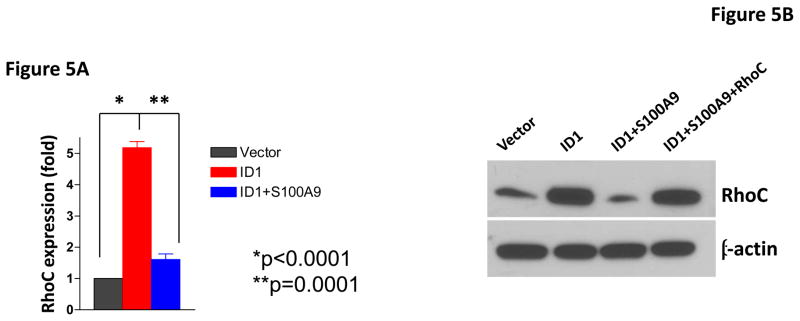

S100A9 mediates the regulation of RhoC by Id1

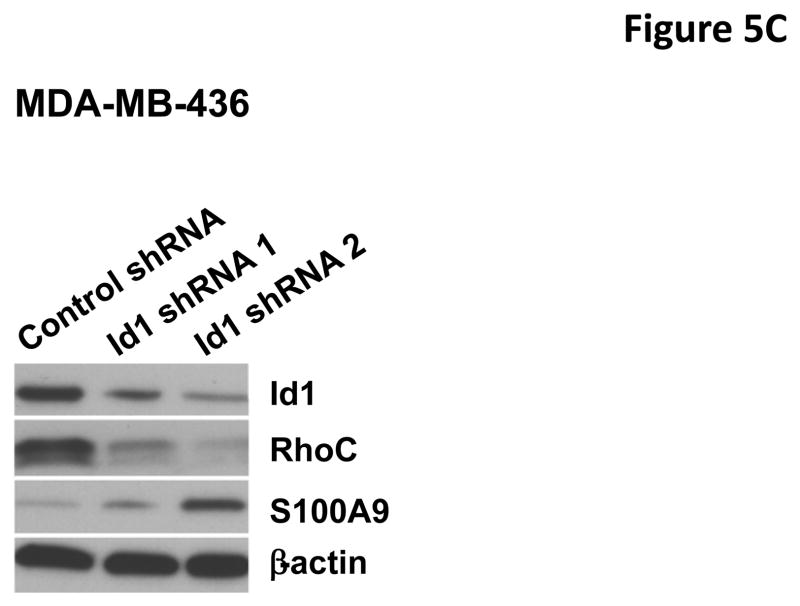

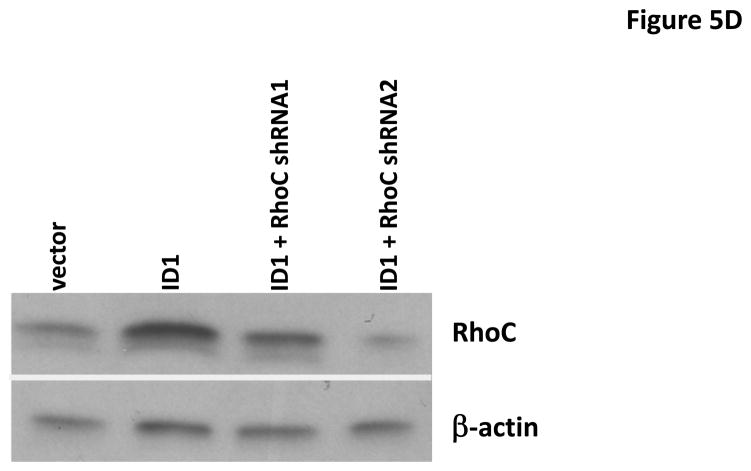

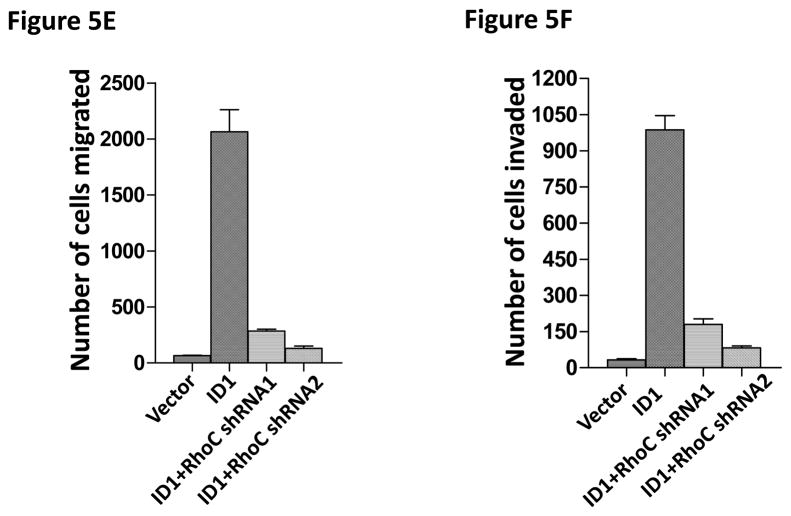

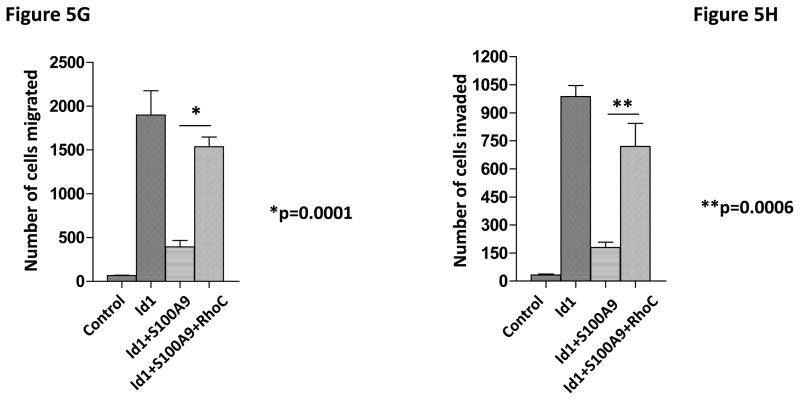

To identify the molecules and pathways downstream of S100A9 in metastasis, we searched the gene expression profiles of MCF7 cells stably expressing Id1 or Id2 and found that known metastasis-promoting gene RhoC was up-regulated only in the Id1 expressing cells. We further analyzed RhoC expression in MCF7 cells stably expressing S100A9 and Id1 or Id1 alone by quantitative RT-PCR. Expression of RhoC was increased in the cell expressing only Id1 but was significantly suppressed in cells stably expressing both Id1 and S100A9 (Figure 5A). These results were further confirmed by the immunoblotting (Figure 5B). Knockdown of Id1 in MDA-MB-436 cells which express high level of Id1 but low level of S100A9 resulted in the up-regulation of S100A9 expression and the down-regulation of RhoC expression (Figure 5C). To determine the effects of RhoC down-regulation in migration and invasion, we knocked down RhoC expression using two different short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) in MCF7 cells stably expressing Id1. The down-regulation of RhoC expression by shRNAs was confirmed by immunoblot (Figure 5D). Down-regulation of RhoC abrogated the migratory and invasive phenotypes induced by Id1 expression in MCF7 cells (Figure 5E, 5F). Conversely, overexpression of RhoC in MCF7 cells expressing Id1 and S100A9 partially rescued the migratory and invasive phenotypes that were suppressed by S100A9 (Figure 5G and 5H). These results indicated that RhoC expression is regulated by S100A9 and RhoC suppression reduced the migratory and invasive phenotypes induced by Id1 expression.

Figure 5.

S100A9 suppresses RhoC expression. RhoC expression in MCF7 cells stably expressing a vector control, or Id1, or Id1 and S100A9 was determined by quantitative RT-PCR (A) and immunoblot (B). Id1 expression in MCF7 cells increased RhoC expression (A and B). Expression of S100A9 cDNA reversed the increase of RhoC expression induced by Id1 expression (A and B). (C) Immunoblots of Id1, S100A9 and RhoC in MDA-MB-436 cells expressing a control shRNA or Id1 shRNA. Knockdown of Id1 expression in MDA-MB-436 cells increased S100A9 expression and decreased RhoC expression. (D) RhoC expression in MCF7 cells expressing a vector control, or Id1, or Id1 and RhoC shRNA 1, or Id1 and RhoC shRNA 2. (E–H) RhoC mediated the Id1 functions in migration and invasion. MCF7 cells stably expressing a vector control, or Id1, or Id1 and RhoC shRNA 1, or Id1 and RhoC shRNA 2 were subjected to migration (E) and invasion (F) assays. Id1 expression in MCF7 cells increased cell migration and invasion (E and F). Knockdown of RhoC expression reversed the migratory and invasive phenotypes induced by Id1 (E and F). MCF7 cells stably expressing a vector control, or Id1, or Id1 and S100A9, or Id1 plus S100A9 and RhoC were subjected to migration (G) and invasion (H) assays. S100A9 expression decreased the cell migratory and invasive phenotypes induced by Id1 (G and H). Expression of RhoC rescued the suppressive phenotype of S100A9 in migration and invasion (G and H).

Discussion

We have previously reported that knockdown of metastasis suppressor KLF17 activates Id1 expression and promote lung metastasis in breast cancer. However, the molecular pathways downstream of Id1 were not known. In this study, we show that Id1 promotes metastasis by the suppression of S100A9 expression in breast cancer cells. We also found that RhoC mediates Id1 functions and is downstream of S100A9. Based on these results, we propose a molecular pathway model for the function of KLF17: Knockdown of KLF17 activates Id1 expression which interacts with TFAP2A to suppress S100A9 expression. The suppression of S100A9 leads to the activation of RhoC, cell migration, invasion and metastasis phenotypes. S100A9 expression partially rescued the metastasis phenotype induced by Id1, thus it is likely that there are other molecules regulated by Id1 also participate in the Id1 metastasis function. The identification and characterization of these molecules are currently underway.

Id family members share similar sequences and form heterodimers with other transcription factors to regulate gene expression. Although it is well established that Id1 is a major promoting factor for lung metastasis in breast cancer, downstream target genes and molecular pathways have been elusive. This is at least partly due to the factor that Id family members interact with other transcription factor to regulate gene expression instead of directly binding to the promoters of the genes they regulate. They regulate a large number of genes and overlap in the target gene regulation. Our results indicated that different Id family members have different functions and the downstream target genes that mediate these functions are also differentially regulated. Our findings that Id1 but not Id2 promotes lung metastasis in breast cancer also led us to identify S100A9, an important player in the regulation of metastasis functions of Id1. Id family members have diverse functions in development and tumorigenesis. The genes and molecule pathways regulated by Id family members in these processes are largely unknown. Our approach can be used to identify these additional genes and pathways that mediate the functions of Id family members.

S100A9 functions in a variety of physiological process including inflammation and myeloid cell maturation. It binds to cell surface receptors including TLR4/RAGE and initiates signaling pathways that affects multiple cellular functions including the activation of reactive oxygen species pathway. It has also been shown that S100A9 can promote or suppress breast cancer development (48, 49). The dichotomy of S100A9 functions in breast cancer possibly depends on cellular context, local concentration, its expression level and post-translational modification. It has been shown to promote metastasis in melanoma (50), but suppress metastasis in human cervical cancer (51). Our results indicated that S100A9 is regulated by Id1 and serves as a negative regulator of RhoC, a critical factor in cell motility and metastasis. The molecular mechanisms of RhoC regulation by S100A9 in breast cancer remain to be determined. The other aspect that is important in the understanding of S100A9 regulation of metastasis is whether the expression of S100A9 in cancer cells also affects tumor microenvironment in breast cancer. The characterization of S100A9 in both cancer cells and tumor microenvironment will further improve our knowledge of S100A9 in cancer development.

S100 family members have diverse functions in cancer development. Some of the family members have overlapping functions and mechanisms in gene regulation. We found that S100A7 and S100P are also differentially regulated by Id1 but not Id2. However these two genes do not mediate the metastasis functions of Id1 (data not shown). Understanding the differential functions of S100 family members in the different steps of cancer development is critical to our understanding of the roles of this protein family. Both KLF17 and Id1 are transcription factors which are difficult to target by small molecules. The discovery of the downstream targets of Id1 that mediate its functions may provide potential therapeutic targets for the suppression of tumor metastasis in this pathway.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by R01CA148759, Breast Cancer Alliance, W. W. Smith Foundation, Edward Mallinckrodt Jr. Foundation, National Natural Science Foundation of China (81372328), R01-CA142776 (LZ), P50-CA83638-7951 (LZ). Support for Shared Resources utilized in this study was provided by Cancer Center Support Grant (CCSG) CA010815 to The Wistar Institute.

Footnotes

Conflict of interests:

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Valastyan S, Weinberg RA. Tumor metastasis: molecular insights and evolving paradigms. Cell. 2011;147:275–292. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nguyen DX, Bos PD, Massague J. Metastasis: from dissemination to organ-specific colonization. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:274–284. doi: 10.1038/nrc2622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steeg PS. Tumor metastasis: mechanistic insights and clinical challenges. Nat Rev Med. 2006;12:895–904. doi: 10.1038/nm1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eccles SA, Welch DR. Metastasis: recent discoveries and novel treatment strategies. Lancet. 2007;369:1742–1757. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60781-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sethi N, Kang Y. Unravelling the complexity of metastasis-molecular understanding and targeted therapies. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:735–748. doi: 10.1038/nrc3125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsai JH, Yang J. Epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity in carcinoma metastasis. Genes & Dev. 2013;27:2192–2206. doi: 10.1101/gad.225334.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang J, Ma L. MicroRNA control of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2012;31:653–662. doi: 10.1007/s10555-012-9368-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta GP, Massague J. Cancer Metastasis: Building a framework. Cell. 2006;127:679–695. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fidler IJ. The pathogenesis of cancer metastasis: the “seed and soil” hypothesis revisited. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:1–6. doi: 10.1038/nrc1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupta GP, Perk J, Acharyya S, de Candia P, Mittal V, Todorova-Manova K, et al. ID genes mediate tumor reinitiation during breast cancer lung metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19506–19511. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709185104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schoppmann SF, Schindl M, Bayer G, Aumary K, Dienes J, Horvat R, et al. Overexpression of Id-1 is associated with poor clinical outcome in node negative breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2003;104:677–682. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Minn AJ, Gupta GP, Siegel PM, Bos PD, Shu W, Giri DD, et al. Genes that mediate breast cancer metastasis to lung. Nature. 2005;436:518–524. doi: 10.1038/nature03799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin CQ, Singh J, Murata K, Itahana Y, Parrinello S, Liang S, et al. A role for Id-1 in the aggressive phenotype and steroid hormone response of human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1332–1340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perk J, Iavarone A, Benezra R. Id family of helix-loop-helix proteins in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:603–614. doi: 10.1038/nrc1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sikder HA, Devin MK, Dunlap S, Ryu B, Alani R. Id proteins in cell growth and tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:525–530. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00141-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ling MT, Wang X, Zhang X, Wong YC. The multiple roles of Id-1 in cancer progression. Differentiation. 2006;74:481–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2006.00083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Candia P, Benera R, Solit DB. A role for Id proteins in mammary gland physiology and tumorigenesis. Adv Cancer Res. 2004;92:81–94. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(04)92004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fong S, Debs RJ, Desprez PY. Id genes and proteins as promising targets in cancer therapy. Trends Mol Med. 2004;10:387–392. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruzinova MB, Benezra R. Id proteins in development, cell cycle and cancer. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:410–418. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(03)00147-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hasskarl J, Munger K. Id proteins-tumor markers or oncogenes? Cancer Biol Ther. 2002;1:91–96. doi: 10.4161/cbt.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benezra R, Rafii S, Lyden D. The Id proteins and angiogenesis. Oncogene. 2001;20:8334–8341. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lasorella A, Uo T, Iavarone A. Id proteins at the cross-road of development and cancer. Oncogene. 2001;20:8326–8333. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zebedee Z, Hara E. Id proteins in cell cycle control and cellular senescence. Oncogene. 2001;20:8317–8325. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Norton JD. Id helix-loop-helix proteins in cell growth, differentiation and tumorigenesis. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:3897–3905. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.22.3897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Norton JD, Atherton GT. Coupling of cell growth control and apoptosis functions of Id proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2371–2381. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.4.2371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsunedomi R, Lizuka N, Tamesa T, Sakamoto K, Hamaguchi T, Somura H, et al. Decresed ID2 promotes metastatic potentials of hepatocellular carcinoma by altering secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:1025–1031. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lyden D, Young AZ, Zagzag D, Yan W, Geraldk W, O’Reilly R, et al. Id1 and Id2 are required for neurogenesis, angiogenesis and vascularization of tumor xenografts. Nature. 1999;401:670–677. doi: 10.1038/44334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Desprez P, Lin CQ, Thomasset N, Sympson CJ, Bissell MJ, Campisi J. A novel pathway of mammary epithelial cell invasion induced by the helix-loop-helix protein Id-1. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4577–4588. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.8.4577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fong S, Itahana Y, Sumida T, Singh J, Coppe J, Liu Y, et al. Id-1 as a molecular target in therapy for breast cancer cell invasion and metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:13543–13548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2230238100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McAllister SD, Murase R, Christian RT, Lau D, Zielinsk AJ, Allison J, et al. Pathways mediating the effects of cannabidiol on the reduction of breast cancer cell proliferation, invasion, and metastasis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;129:37–47. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1177-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soroceanu L, Murase R, Limbad C, Singer E, Allison J, Adrados I, et al. Id-1 is a key transcriptional regulator of glioblastoma aggressiveness and a novel therapeutic target. Cancer Res. 2013;73:1559–1569. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsuchiya T, Okaji Y, Tsuno NH, Sakurai D, Tsuchiya N, Kawai K, et al. Targeting Id1 and Id3 inhibits peritoneal metastasis of gastric cancer. Cancer Sci. 2005;96:784–790. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2005.00113.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benezra R. The Id proteins: targets for inhibiting tumor cells and their blood supply. Biochim et Biophys Acta. 2001:F39–F47. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(01)00028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh J, Murata K, Itahana Y, Desprez PY. Constitutive expression of the Id-1 promoter in human metastatic breast cancer cells is linked with the loss of NF-1/Rb/HDAC-1 transcription repressor complex. Oncogene. 2002;21:1812–1822. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coppe JP, Smith AP, Desprez PY. Id proteins in epithelial cells. Exp Cell Res. 2003;285:131–145. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gumireddy K, Li A, Gimotty PA, Klein-Szanto AJ, Showe LC, Katsaros D, et al. KLF17 is a negative regulator of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis in breast cancer. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:1297–1304. doi: 10.1038/ncb1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McAllister SD, Christian RT, Horowitz MP, Garcia A, Desprez P. Cannabidiol as a novel inhibitor of Id-1 gene expression in aggressive breast cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:2921–2927. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mistry H, Hsieh G, Buhrlage SJ, Huang M, Park E, Cuny GD, et al. Small-molecule inhibitors of USP1 target ID1 degradation in leukemic cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2013;12:2651–2662. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0103-T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Henke E, Perk J, Vider J, de Candia P, Chin Y, Solit DB, et al. Peptide-conjugated antisense oligonucleotides for targeted inhibition of a transcriptional regulator in vivo. Nat Biotech. 2008;26:91–100. doi: 10.1038/nbt1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen C, Kuo S, Huang L, Hsu M. Affinity of synthetic peptide fragments of MyoD for Id1 protein and their biological effects in several cancers. J Pept Sci. 2010;16:231–241. doi: 10.1002/psc.1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gumireddy K, Li A, Yan J, Setoyama T, Johannes GJ, Orom UA, et al. Identification of a long non-coding RNA-associated RNP complex regulating metastasis at the translational step. EMBO J. 2013;32:2672–2684. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Storey JD, Tibshirani R. Statistical significance for genome-wide studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:9440–9445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1530509100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Markowitz J, Carson WE., III Review of S100A9 biology and its role in cancer. Biochim et Biophys Acta. 2013;1835:100–109. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Srikrishna G. S100A8 and S100A9: new insights into their roles in malignancy. J Innate Immun. 2012;4:31–40. doi: 10.1159/000330095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Choi JH, Shin NR, Moon HJ, Kwon CH, Kim GH, Song GA, et al. Identification of S100A8 and S100A9 as negative regulators for lymph node metastasis of gastric adenocarcinoma. Histol Histopathol. 2012;27:1439–1448. doi: 10.14670/HH-27.1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Qin F, Song Y, Li Z, Zhao L, Zhang Y, Geng L. S100A8/A9 induces apoptosis and inhibits metastasis of CasKi human cervical cancer cells. Pathol Onco Res. 2010;16:353–360. doi: 10.1007/s12253-009-9225-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hibino T, Sakaguchi M, Miyamoto S, Yamamoto M, Motoyama A, Hosoi J, et al. S100A9 is a novel ligand of EMMPRIN that promotes melanoma metastasis. Cancer Res. 2013;73:172–183. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li C, Zhang F, Lin M, Liu J. Induction of S100A9 gene expression by cytokine oncostatin M in breast cancer cells through the STAT3 signaling cascade. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2004;87:123–134. doi: 10.1023/B:BREA.0000041594.36418.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moon HY, Yong JI, Song D, Cukovic S, Salagrama D, Kaplan D, et al. Global gene expression profiling unveils S100A8/A9 as candidate markers in H-ras-mediated human breast epithelial cell invasion. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6:1544–1553. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hibino T, Sakaguchi M, Miyamoto S, Yamamoto M, Motoyama A, Hosoi J, et al. S100A9 is a novel ligand of EMMPRIN that promotes melanoma metastasis. Cancer Res. 2013;73:172–183. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qin F, Song Y, Li Z, Zhao L, Zhang Y, Geng L. S100S8/A9 induces apoptosis and inhibits metastasis of CasKi human cervical cancer cells. Pathol Onco Res. 2010;16:353–360. doi: 10.1007/s12253-009-9225-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.