Abstract

Background

Little is known about the effectiveness of strategies to enable people to achieve and maintain recommended levels of physical activity.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of interventions designed to promote physical activity in adults aged 16 years and older, not living in an institution.

Search methods

We searched The Cochrane Library (issue 1 2005), MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycLIT, BIDS ISI, SPORTDISCUS, SIGLE, SCISEARCH (from earliest dates available to December 2004). Reference lists of relevant articles were checked. No language restrictions were applied.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials that compared different interventions to encourage sedentary adults not living in an institution to become physically active. Studies required a minimum of six months follow up from the start of the intervention to the collection of final data and either used an intention‐to‐treat analysis or, failing that, had no more than 20% loss to follow up.

Data collection and analysis

At least two reviewers independently assessed each study quality and extracted data. Study authors were contacted for additional information where necessary. Standardised mean differences and 95% confidence intervals were calculated for continuous measures of self‐reported physical activity and cardio‐respiratory fitness. For studies with dichotomous outcomes, odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated.

Main results

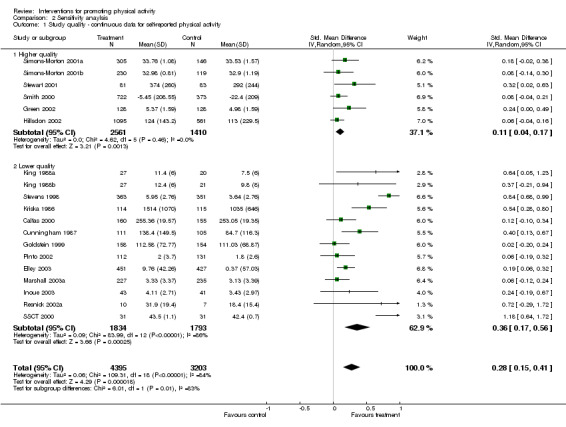

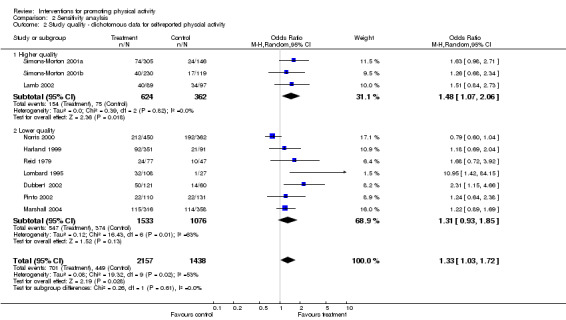

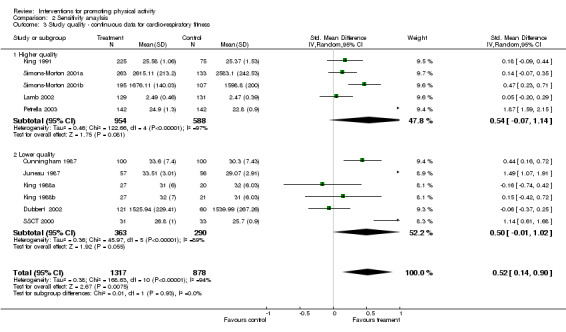

The effect of interventions on self‐reported physical activity (19 studies; 7598 participants) was positive and moderate (pooled SMD random effects model 0.28 95% CI 0.15 to 0.41) as was the effect of interventions (11 studies; 2195 participants) on cardio‐respiratory fitness (pooled SMD random effects model 0.52 95% CI 0.14 to 0.90). There was significant heterogeneity in the reported effects as well as heterogeneity in characteristics of the interventions. The heterogeneity in reported effects was reduced in higher quality studies, when physical activity was self‐directed with some professional guidance and when there was on‐going professional support.

Authors' conclusions

Our review suggests that physical activity interventions have a moderate effect on self‐reported physical activity, on achieving a predetermined level of physical activity and cardio‐respiratory fitness. Due to the clinical and statistical heterogeneity of the studies, only limited conclusions can be drawn about the effectiveness of individual components of the interventions. Future studies should provide greater detail of the components of interventions.

Keywords: Humans, Exercise, Health Promotion, Health Promotion/methods, Physical Fitness, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Interventions for promoting physical activity

Not taking enough physical activity leads to an increased risk of a number of chronic diseases including coronary heart disease. Regular physical activity can reduce this risk and also provide other physical and possibly mental health benefits. The majority of adults are not active at recommended levels. The findings of this review indicate that professional advice and guidance with continued support can encourage people to be more physically active in the short to mid‐term. More research is needed to establish which methods of exercise promotion work best in the long‐term to encourage specific groups of people to be more physically active.

Background

Regular physical activity can play an important role both in the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease (CVD), hypertension, non‐insulin dependent diabetes, diabetes mellitus, obesity, stroke, some cancers, and osteoporosis, as well as improve the lipid profile (DOH 2004; Folsom 1997; FNB 2002; US Dept. Health 1996; WHO 2004). A meta‐analysis of the relationship between physical activity and coronary heart or cardiovascular disease reported a 30% lower risk for the most physically active versus the least physically activity (Williams 2001). In addition, physical inactivity has been estimated to cause, globally, about 22% of ischaemic heart disease (WHO 2002).

The English Chief Medical Officer (CMO) advises that adults should undertake at least 30 minutes of 'moderate intensity' (5.0‐7.5 kcal/min) physical activity on at least 5 days of the week to benefit their health (DOH 2004). The recommendations are similar to those published in the US and by the World Health Organisation (Pate 1995; US Dept. Health 1996; WHO 2004).

In England the prevalence of physical activity at recommended levels is low. The most recent data show that only 37% of men and 25% of women meet the CMO's physical activity recommendation (DOH 2005a). Local government authorities have been set a target to 'increase the number of adults who engage in at least 30 minutes of moderate intensity level sport three times a week, by 3% by 2008' (DOH 2005b; HM Treasury 2002).

There are randomised controlled trials assessing the effects of physical activity in the management of specific diseases, notably hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, obesity and CVD (DOH 2004). These show the effects of exercise on various physiological and biological outcomes and demonstrate the importance of exercise in the management of disease. However, because the main outcome of these trials is not physical activity, they do not help us understand the effectiveness of physical activity promotion strategies in the general population. A number of Cochrane reviews have assessed the relationship of the effects of exercise upon type 2 diabetes and as part of cardiac rehabilitation (Jolliffe 2001; Thomas 2006).

One recent published review examined the evidence for the effectiveness of 'home based' versus 'centre based' physical activity programs on the health of older adults (Ashworth 2005). Study participants had to have either a recognised cardiovascular risk factor, or existing cardiovascular disease, or chronic obstructive airways disease (COPD) or osteoarthritis. The authors found six trials involving 224 participants who received a 'home based' exercise program and 148 who received a 'centre based' exercise program. They concluded there was insufficient evidence to make any conclusions in support of either home or centre based physical activity programs.

Objectives

To compare the effectiveness of interventions for physical activity promotion in adults aged 16 and above, not living in an institution, with no intervention, minimal intervention or attention control. If sufficient trials existed, the following secondary objectives were to be explored:

a) Are more intense interventions more effective in changing physical activity than less intense interventions (e.g. a greater frequency and duration of professional contact and support v single contact)?

b) Are specific components of interventions associated with changes in physical activity behaviour (e.g. prescribed v self determined physical activity, supervised v unsupervised physical activity)?

c) Are short‐term changes in physical activity or fitness (e.g. less than 3 months from intervention, less than 6 months from intervention) maintained at 12 months?

d) Is the promotion of some types of physical activity more likely to lead to change than other types of physical activity (e.g. walking versus exercise classes)?

e) Are home‐based interventions more successful than facility‐based interventions?

f) Are interventions more successful with particular participant groups (e.g. women, older, minority)?

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing different strategies to encourage sedentary, community dwelling adults to become more physically active, with a minimum of 6 months follow‐up from the start of the intervention to the final results using either an intention to treat analysis or no more than 20% loss to follow up.

Types of participants

Community dwelling adults, age 16 years to any age, free from pre‐existing medical condition or with no more than 10% of subjects with pre‐existing medical conditions that may limit participation in physical activity. Interventions on trained athletes or sports students were excluded.

Types of interventions

One only or a combination of:

One‐to‐one counselling/advice or group counselling/advice;

Self‐directed or prescribed physical activity;

Supervised or unsupervised physical activity;

Home‐based or facility‐based physical activity;

Ongoing face‐to‐face support;

Telephone support;

Written education/motivation support material;

Self monitoring.

The interventions were conducted by one or a combination of practitioners including a physician, nurse, health educator, counsellor, exercise leader or peer. Mass media interventions and multiple risk factor interventions were excluded.

The interventions were compared with a no intervention control, attention control (receiving attention matched to length of intervention, e.g. general health check) and/or minimal intervention control group.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcome measures

Change in self‐reported physical activity between baseline and follow‐up.

Cardio‐respiratory fitness.

Adverse events.

Physical activity measures were expressed as an estimate of total energy expenditure (kcal/kg/week, kcal/week), total minutes of physical activity, proportion reporting a pre‐determined threshold level of physical activity (e.g., meeting current public health recommendation), frequency of participation in various types of physical activity e.g. walking, moderate intensity physical activity.

Cardio‐respiratory fitness was either estimated from a sub‐maximal fitness test or recorded directly from a maximal fitness test and was expressed as maximal oxygen consumption (VO2 max) either in ml·kg‐1·min‐1 or ml·min‐1. Aspects of cardio‐respiratory fitness were also included as secondary outcome measures.

Adverse events included job‐related injuries any reported musculoskeletal injury or cardiovascular events (and exercise‐related cardiac events and injuries (fractures, sprains)).

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched The Cochrane Library (Issue 1, 2005) , MEDLINE (January 1966 to December 2004), EMBASE (January 1980 to December 2004), CINAHL (January 1982 to December 2004), PsycLIT (1887 to December 2004), BIDS ISI (January 1973 to December 2004), SPORTDISCUS (January 1980 to December 2004), SIGLE (January 1980 to December 2004) and SCISEARCH (January 1980 to December 2004), and reference lists of articles. Hand searching was conducted on one journal Medicine and Science in Sport and Exercise from 1990 to December 2004. Published systematic reviews of physical activity interventions were used as a source of randomised controlled trials. Reference lists of all relevant articles, books and personal contact with authors were also used. All languages were included.

The search strategy below was used to search MEDLINE, with the addition of an RCT filter (Dickersin 1995). This strategy was modified for other databases, using an appropriate RCT filter for EMBASE (Lefebvre 1996). (see Table 1; Table 2;Table 3;Table 4;Table 5; Table 6).

1. Search Strategy for EMBASE.

| Dates 2000 to 2004 |

| 1.((((health‐education) or (health‐education‐research)) or ((patient‐education) or (patient‐education‐and‐counseling)) or ((health‐promotion) or (health‐promotion‐international)) or (primary‐health‐care) or ((workplace) or (workplace‐)) or (promot*) or ((promot*) or ((educat*) or ((program*) and ((((exertion) or (fitness) or (fitness‐) or ((fitness) or (fitness‐)) or (exercise) or ((exercise) or (sport) or (walk*))) 2.((research) or (((((random‐controlled) or (random‐sample) or (randomisation) or (randomised) or (randomised‐controlled) or (randomization) or (randomization‐) or (randomizd) or (randomize) or (randomized) or (randomized‐block) or (randomized‐controlled) or (randomized‐controlled‐trial) or (randomized‐control)) or ((double‐blind) or (double‐blind‐procedure)) or ((single‐blind) or (single‐blind‐procedure))) and (ec=human)) or (clinical) or (clin*) or (trial*) or (((clin* near trial*) in ti) and (ec=human)) or (clin*) or (trial*) or (((clin* near trial*) in ab) and (ec=human)) or (sing*) or (doubl*) or (trebl*) or (tripl*) or (blind*) or (mask*) or (((sing* or doubl* or trebl* or tripl*) near (blind* or mask*)) and (ec=human)) or ((placebos) or (placebo‐controlled)) or ((placebo* in ti) and (ec=human)) or ((placebo* in ab) and (ec=human)) or ((random* in ti) and (ec=human)) or ((random in ab) and (ec=human)) or (research)) ec=human) 3.((((studies) or (prospective‐study) or (follow‐up) or (comparative) or (evaluation)) and (ec=human)) |

2. Search Strategy for CINAHL.

| Dates 2000 to 2004 |

| 1.exact{controlled} 2.exact{randomized} 3.exact{random‐assignment} 4.exact{double‐blind} 5.exact{single‐blind} 6.#1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 7.exact{animal} 8.exact{human} 9.#6 not #7 10.exact{clinical} 11.(clin* near trial*) in ti 12.(clin* near trial*) in ab 13.(singl* or doubl* or trebl* or tripl*) near (blind* or mask*) 14.(#13 in ti) or (#13 in ab) 15.placebos 16.placebo* in ti 17.placebo* in ab 18.random* in ti 19.random* in ab 20.exact{research‐methodology} 21.#10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15 or #16 or #17 22.#18 or #19 or #20 23.#21 or #22 24.animal 25.human 26.#23 not #24 27.#26 or #9 or #8 or #25 28.exact{comparative} 29.study 30.#28 and #29 31.exact{evaluation} 32.studies 33.#31 and #32 34.exact{follow‐up} 35.exact{propsective} 36.#35 and #32 37.control* or prosepctiv* or volunteer* 38.(#37 in ti) or (#37 in ab) 39.#38 or #36 or #33 or #30 40.#39 not #24 41.#39 or #27 or #9 42.explode "exertion/"/ all subheadings 43."physical fitness" 44.explode "physical education and training"/ all subheadings 45.explode "sports"/ all subheadings 46.explode "dancing"/ all subheadings 47.explode "exercise therapy"/ all subheadings 48.(physical$ adj5 (fit$ or train$ or activ$ or endur$)).tw. 49.(exercis$ adj5 (train$ or physical$ or activ$)).tw. 50.sport$.tw. 51.walk$.tw. 52.bicycle$.tw 53.(exercise$ adj aerobic$).tw. 54.(("lifestyle" or life‐style) adj5 activ$).tw. 55.(("lifestyle" or life‐style) adj5 physical$).tw. 56.#42 or #43 or #44 or #45 or #46 or #47 or #48 or #49 or (exercise$) or (aerobic$) or ("lifestyle") or (activ$) or ("lifestyle") or (life‐style) or (physical$) 57.health education 58.patient education 59.primary prevention 60.health promotion 61.behaviour therapy 62.cognitive therapy 63.primary health care 64.workplace 65.promot$.tw. 66.educat$.tw. 67.program$.tw. 68.#57 or #58 or #59 or #60 or #61 or #62 or #63 or #64 or #65 or #66 or #67 69.#68 and #56 70.#69 and #41 |

3. Search Startegy for PsycLIT.

| Dates 2000 to 2004 |

| 1.exertion 2.physical‐fitness 3.exercise 4.explode exercise 5.sport 6.walk* 7.cycle 8.#1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 9.health education 10.patient education 11.primary prevention 12.health promotion 13.behaviour therapy 14.cognitive therapy 15.primary health care 16.workplace 17.promot$.tw. 18.educat$.tw. 19.program$.tw. 20.#9 or #10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15 or #16 or #17 or #18 or #19 21.#8 and #20 22.controlle 23.randomized 24.random‐assignment 25.double‐blind 26.single‐blind 27.#22 or #23 or #24 or #25 or #26 28.animal 29.human 30.#27 not #28 31.clinical 32.(clin* near trial*) in ti 33.clin* near trial*) in ab 34.(singl* or doubl* or trebl* or tripl*) near (blind* or mask*) 35.(#34 in ti) or (#34 in ab) 36.placebos 37.placebo* in ti 38.placebo* in ab 39.random* in ti 40.random* in ab 41.research‐methodology} 42.#31 or #32 or #33 or #34 or #35 or #36 or #37 or #38 43.#39 or #40 or #41 44.#42 or #43 45.animal 46.human 47.#44 not #45 48.#47 or #30 or #29 or #46 49.comparative 50.study 51.#49 and #50 52.evaluation 53.studies 54.#52 and #53 55.follow‐up 56.propsective 57.#56 and #53 58.control* or prosepctiv* or volunteer* 59.(#58 in ti) or (#58 in ab) 60.#59 or #57 or #54 or #51 61.#60 not #45 62.#60 or #48 or #30 63.#62 and #21 |

4. Search Startegy SPORTSDISCUS.

| Dates 2000 to 2004 |

| 1.'physical activity' 2.exercise 3.fitness 4.sedentary 5.housebound 6.aerobics or circuits or swimming or aqua or jogging or running or cycling or fitness or yoga or walking or sport 7.patient education 8.primary prevention 9.health promotion 10.behaviour therapy 11.cognitive therapy 12.primary health care 13.workplace 14.controlled 15.randomized 16.random‐assignment 17.double‐blind 18.single‐blind 19.clinical 20.placebos 21.comparative 22.evaluation 23.study |

5. Search Strategy SIGLE.

| Dates 2000 to 2004 |

| 1.explode "Exertion/"/ all subheadings 2."Physical fitness" 3.explode "Physical education and training"/ all subheadings 4.explode "Sports"/ all subheadings 5.explode "Dancing"/ all subheadings 6.explode "Exercise therapy"/ all subheadings 7.(physical$ adj5 (fit$ or train$ or activ$ or endur$)).tw. 8.(exercis$ adj5 (train$ or physical$ or activ$)).tw. 9.sport$.tw. 10.walk$.tw. 11.bicycle$.tw 12.(exercise$ adj aerobic$).tw. 13.(("lifestyle" or life‐style) adj5 activ$).tw. 14.(("lifestyle" or life‐style) adj5 physical$).tw. 15.#1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 or (exercise$) or (aerobic$) or ("lifestyle") or (activ$) or ("lifestyle") or (life‐style) or (physical$) 16.Health Education 17.Patient education 18.Primary prevention 19.Health promotion 20.Behaviour therapy 21.Cognitive therapy 22.Primary health care 23.Workplace 24.promot$.tw. 25.educat$.tw. 26.program$.tw. 27.#16 or #17 or #18 or #19 or #20 or #21 or #22 or #23 or #24 or #25 or #26 28.#15 and #27 |

6. Search Strategy SCISEARCH.

| Dates 2000 to 2004 |

| 1.((promot$ or uptake or encourag$ or increas$ or start) near (physical adj activity)) 2.(promot$ or uptake or encourag$ or increas$ or start) near exercise 3.(promot$ or uptake or encourag$ or increas$ or start) near (aerobics or circuits or swimming or aqua$) 4.(promot$ or uptake or encourag$ or increas$ or start) near (jogging or running or cycling) 5.(promot$ or uptake or encourag$ or increas$ or start) near ((keep adj fit) or (fitness adj class$) or yoga) 6.(promot$ or uptake or encourag$ or increas$ or start) near walking 7.(promot$ or uptake or encourag$ or increas$ or start) near sport$ |

1 exp Exertion/ 2 Physical fitness/ 3 exp "Physical education and training"/ 4 exp Sports/ 5 exp Dancing/ 6 exp Exercise therapy/ 7 (physical$ adj5 (fit$ or train$ or activ$ or endur$)).tw. 8 (exercis$ adj5 (train$ or physical$ or activ$)).tw. 9 sport$.tw. 10 walk$.tw. 11 bicycle$.tw. 12 (exercise$ adj aerobic$).tw. 13 (("lifestyle" or life‐style) adj5 activ$).tw. 14 (("lifestyle" or life‐style) adj5 physical$).tw. 15 or/1‐14 16 Health education/ 17 Patient education/ 18 Primary prevention/ 19 Health promotion/ 20 Behaviour therapy 21 Cognitive therapy 22 Primary health care 23 Workplace/ 24 promot$.tw. 25 educat$.tw. 26 program$.tw. 27 or/16‐26 28 15 and 27

Data collection and analysis

All abstracts were reviewed independently by two investigators who applied the following criteria to determine if the full paper was needed for further investigation: a) did the study aim to examine the effectiveness of a physical activity promotion strategy to increase physical activity behaviour? b) did the study have a control group (e.g. a no intervention control, attention control and/or minimal intervention control group)? c) did the study allocate participants into intervention or control groups by a method of randomisation? d) did the study include adults of 16 years or older? e) did the study recruit adults not living in institutions and free of chronic disease? f) was the study's main outcome physical activity or physical fitness? g) were the main outcome(s) measured at least 6 months after the start of the intervention? h) did the study analyse the results by intention‐to‐treat or, failing that was there less than 20% loss to follow up?

Two reviewers examined a hard copy of every paper that met the inclusion criteria on the basis of the abstract alone (or title and keywords if no abstract was available). When a final group of papers was identified all papers were reviewed again by two reviewers independently. Any disagreement at this stage was discussed between the three reviewers and resolved by consensus.

From the final set of studies that met the inclusion criteria, study details were extracted independently by two reviewers onto a standard form. Again any disagreements were discussed between three reviewers and resolved by consensus. Extracted data included date and location of study, study design variables, methodological quality, characteristics of participants (age, gender, ethnicity), intervention strategies, frequency and type of intervention and follow‐up contacts, degree of physical activity supervision, study outcome measure, effectiveness of intervention and adverse events.

We wrote to and received clarification from 11 authors of the studies selected for the review. Our requests focused on data missing or unclear from the published papers and included data on study numbers at final analysis, means and standard deviations for intervention and control arms. For incomplete responses, we wrote again to authors asking for further data.

We found different types of outcome results published in two included papers for the Sendai Silver Centre Trial (SSCT 2000). Tsuji 2000 reported changes in cardiovascular fitness and Fujita 2003 reported increases in self‐reported physical activity.

Outcomes were analysed both as continuous outcomes and as dichotomous outcomes (active/sedentary) wherever possible. Standard statistical approaches were adopted:

(a) For each study with continuous outcomes; a standardised mean difference (SMD) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated. If the study had more than two arms then the overall effects of the intervention versus control (means and standard deviations) were examined by pooling the individual effect of each intervention arm (means and standard deviations). These pooled groups means and standard deviations were weighted for overall numbers within each arm (Higgins 2005). Pooled effect sizes were calculated as standardised mean differences with 95% CI using a random‐effects model.

(b) For each study with dichotomous outcomes; an odds ratio (OR) and 95% CI were calculated. Pooled effect sizes were calculated as ORs and with 95% CI using a random‐effects model.

We examined five thematic characteristics of each intervention to try to assess if they modified the main effects of the interventions. These five characteristics were the nature of direction at first contact, degree of programme supervision, frequency of intervention occasions, frequency of follow‐up contacts and type of follow‐up contacts.

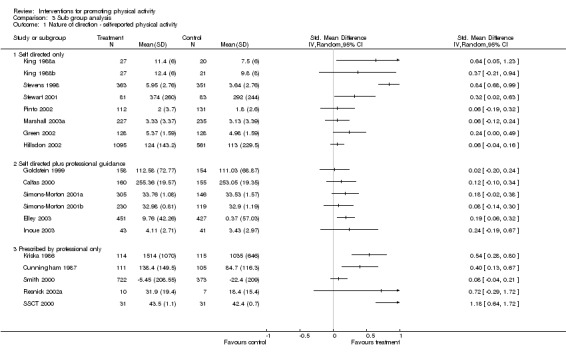

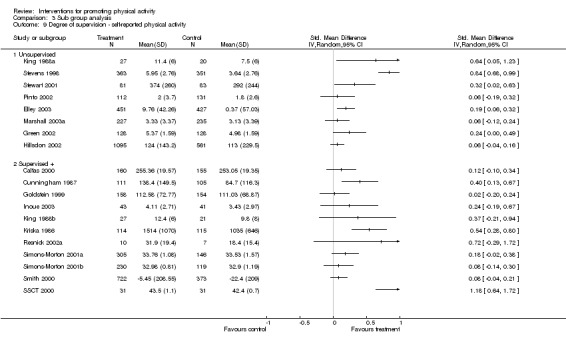

We described the nature of the initial contact between the participant and professional/researcher as "the nature of direction". We found three types of intervention: (i) self‐directed only ‐ where the participant is not directed in their choices and thinking about which physical activities to start by the professional; (ii) self‐directed plus professional guidance ‐ where the participant can make a decision about their physical activity using a mixture of both self direction and professional advice and guidance; and (iii) prescribed by professional only ‐ the participant receives the advice and prescription of physical activity from the professional.

We wanted to evaluate the type and supervision of physical activity adopted within studies. We developed three categories of programme supervision: (i) structured and supervised ‐ the physical activity programme was structured and supervised by professional; (ii) unsupervised and independent ‐ the physical activity programme was unstructured and performed independently by the participant; and (iii) mixed ‐ the physical activity programme was both structured and supervised and unstructured and independent.

Results

Description of studies

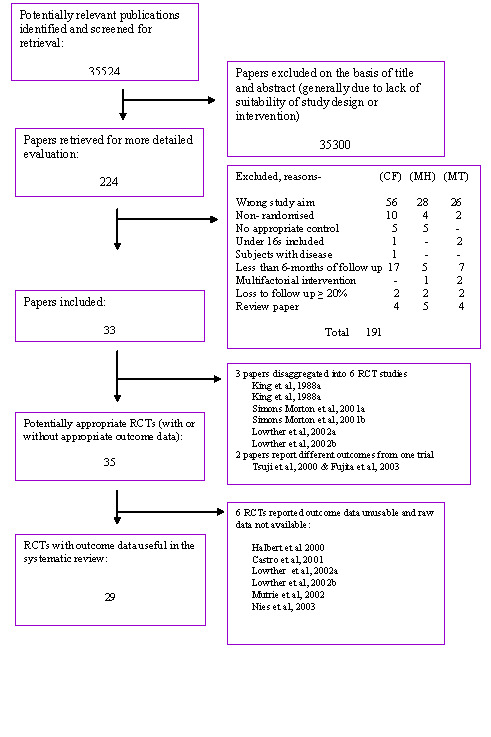

From 35,524 hits, 287 papers were retrieved for examination against the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Thirty three papers describing 35 studies met the inclusion criteria. We were unable to secure the requested information from five studies. Halbert 2000 was not contactable and so this study is not presented in the final results. Four studies sent data but the data was incomplete or inappropriate for meta‐analysis (Castro 2001; Lowther 2002a; Lowther 2002b; Mutrie 2002; Nies 2003). After excluding these studies with incomplete data, 29 studies remained (Calfas 2000; Cunningham 1987; Dubbert 2002; Elley 2003; Goldstein 1999; Green 2002; Harland 1999; Hillsdon 2002; Inoue 2003; Juneau 1987; King 1988a; King 1988b; King 1991; Kriska 1986; Lamb 2002; Lombard 1995; Marshall 2003a; Marshall 2004; Norris 2000; Petrella 2003; Pinto 2002; Reid 1979; Resnick 2002a; Simons‐Morton 2001a; Simons‐Morton 2001b; Smith 2000; Stevens 1998; Stewart 2001; SSCT 2000). All 29 studies were randomised controlled trials. Two papers each reported the results of two separate trials (King 1988a; King 1988b; Simons‐Morton 2001a; Simons‐Morton 2001b). Two papers reported different outcomes for one study (SSCT 2000).

1.

QUOROM statement

Participants of included studies 11,513 apparently healthy adults participated in the 29 included studies. The majority of studies recruited both genders with three studies recruiting men only (Cunningham 1987; Reid 1979; Simons‐Morton 2001a) and four studies recruiting women only (Inoue 2003; Kriska 1986; Resnick 2002a; Simons‐Morton 2001b). The stated age range of participants was from 18 to 95 years. Details on ethnic group of participants were reported in 13 studies, with proportions of participants in ethnic minorities ranging from 3% to 55%. Participants were recruited from four settings; primary healthcare, workplaces, university and the community (see Table 7).

7. Descriptive data for review studies.

| Author | Publication year | Setting | No. randomised | % Male | Age range | Authors' description |

| Reid 1979 | 1979 | Workplace | 124 | 100 | 24 to 56 | Endurance activities |

| Kriska 1986 | 1986 | Community | 229 | 0 | 50 to 65 | Walking |

| Cunningham 1987 | 1987 | Workplace / community | 224 | 100 | 54 to 68 | Walking, jogging or running |

| Juneau 1987 | 1987 | Workplace | 120 | 50 | 40 to 60 | Walking or slow jogging |

| King 1988a | 1988 | Workplace | 52 | 50 | 40 to 60 | Walking and jogging |

| King 1988b | 1988 | Workplace | 51 | 51 | 40 to 60 | Walking and jogging |

| King 1991 | 1991 | Community | 357 | 55 | 50 to 65 | Group or home based walking/jogging activities |

| Lombard 1995 | 1995 | University | 135 | 2.2 | 21 to 63 | Walking |

| Stevens1998 | 1998 | Primary Health Care | 714 | 42 | 45 to 74 | Build on present physical activities |

| Goldstein 1999 | 1999 | Primary Health Care | 355 | 35 | 50+ | Choice of moderate or vigorous physical activity |

| Harland 1999 | 1999 | Primary Health Care | 520 | 41.5 | 40 to 64 | Choice of safe and effective physical activity |

| Calfas 2000 | 2000 | University | 338 | 45.8 | 18 to 29 | Moderate or vigorous physical activity plus strength and flexibility activities |

| Norris 2000 | 2000 | Primary Health Care | 847 | 47.9 | 30+ | Moderate physical activity |

| Smith 2000 | 2000 | Primary Health Care | 1142 | 39.5 | 25 to 65 | Physical activity prescribed by medical practitioner |

| Simons‐Morton 2001a | 2001 | Primary Health Care | 479 | 100 | 35 to 75 | Choice of moderate or vigorous physical activity |

| Simons‐Morton2001b | 2001 | Primary Health Care | 395 | 0 | 35 to 75 | Choice of moderate or vigorous physical activity |

| Stewart 2001 | 2001 | Primary Health Care | 173 | 34 | 65 to 95 | Moderate physical activity |

| SSCT 2000* | 2000/2003 | Community | 65 | 46.1 | 60 to 81 | Group based endurance and resistance training |

| Dubbert 2002 | 2002 | Primary Health Care | 212 | 99 | 60 to 80 | Walking |

| Green 2002 | 2002 | Primary Health Care | 316 | 47.5 | 20 to 64 | Moderate physical activity |

| Hillsdon 2002 | 2002 | Primary Health Care | 1658 | 48.9 | 45 to 64 | Choice of physical activity or walking |

| Lamb 2002 | 2002 | Primary Health Care | 260 | 48.8 | 40 to 70 | Moderate intensity physical activity and walking |

| Pinto 2002 | 2002 | Primary Health Care | 298 | 28 | 25+ | Moderate physical activity |

| Resnick 2002 | 2002 | Community | 20 | 0 | 84 to 92 | Group based or home based walking |

| Elley 2003 | 2003 | Primary Health Care | 878 | 33.5 | 40 to 79 | Moderate physical activity or walking |

| Inoue 2003 | 2003 | Community | 86 | 0 | 47 to 68 | Moderate physical activity after group programme |

| Marshall 2003 | 2003 | Community | 462 | 42.5 | 40 to 60 | Moderate physical activity |

| Petrella 2003 | 2003 | Primary Health Care | 284 | 52 | 65+ | Moderate physical activity |

| Marshall 2004 | 2004 | Community | 719 | 36 | Mean 43 | Moderate physical activity |

| *Same study with different outcome data (Tsuji ‐ VO2: Fujita ‐ self reported physical activity) |

Interventions in included studies We found a marked heterogeneity in the interventions used in each study. Studies used one, or combination of, one‐to‐one counselling/advice or group counselling/advice; self‐directed or prescribed physical activity; supervised or unsupervised physical activity; home‐based or facility‐based physical activity; ongoing face‐to‐face support; telephone support; written education/motivation material; self monitoring. The intervention was delivered by one or a number of practitioners with various professional backgrounds including physicians, nurses, health educators, counsellors, exercise leaders and peers.

Only one study (SSCT 2000) adopted a structured and supervised approach to their intervention, encouraging participants to cycle on a static bike for 10 to 25 minutes at a pre‐determined intensity, as part of a 2‐hour exercise session. The majority of studies adopted an unstructured and independently performed physical activity regime.

We found the majority of studies contacted participants on at least three or more occasions in the first 4 weeks of the intervention to support and encourage any adoption of physical activity. Studies offered a range of support and follow up to participants between week 5 and final outcome measure (a minimum of 6 months post baseline intervention). The types of follow‐up offered to participants at any point ranged from postal only, telephone only, face‐to‐face meetings, or a mixture of postal, telephone or face‐to‐face.

We found an even distribution of studies using all three approaches as described in our explanation of 'nature of direction' with the more recently published studies preferring self direction or self direction with professional guidance.

Design of included studies Nine studies had a no‐contact control group. Five studies had attention control groups with control participants receiving non‐exercise related health advice. The remaining studies had comparison control groups, where participants received advice or written information about physical activity. In Petrella 2003 the control participants received exercise counselling and advice and were asked to keep a diary.

Eight studies had more than one intervention arm (Dubbert 2002; Harland 1999; Hillsdon 2002; King 1991; Norris 2000; Simons‐Morton 2001a; Simons‐Morton 2001b; Smith 2000). Four studies conducted an analysis of any intervention vs control by combining intervention arms (Harland 1999; Hillsdon 2002; Norris 2000; Smith 2000). We calculated pooled results for intervention arms for three further studies (King 1991; Simons‐Morton 2001a; Simons‐Morton 2001b). Our analysis of effectiveness when combining intervention arms, differed from the original results presented by two studies (King 1991; Simons‐Morton 2001b). We also combined the results of two studies as the final results for control and intervention groups were reported separately by gender and there was no a priori hypothesis that the effect of the intervention would be different for men and women (Calfas 2000; Juneau 1987).

Outcome measures A number of secondary outcome measures, which were not the focus of this review, were also measured and included body mass index (King 1991; Kriska 1986; Petrella 2003; Stewart 2001), health status, smoking status (King 1991; Kriska 1986; Norris 2000), socio‐behavioural constructs (e.g. self efficacy, reduction in barriers to physical activity), social support and 'stage of change' (Calfas 2000; Goldstein 1999; Norris 2000), time spent in flexibility and strength training (Calfas 2000), weight, height, lean body mass, body fat, plasma lipids (Cunningham 1987; Juneau 1987; Kriska 1986), minute ventilation, maximal heart rate, respiratory exchange ratio, blood cholesterol, flexibility, grip strength, health conditions, systolic and diastolic blood pressure (Cunningham 1987; King 1991; Kriska 1986; Petrella 2003), and alcohol consumption (Kriska 1986).

Risk of bias in included studies

Two of the three reviewers independently assessed the quality of each study that met the inclusion criteria. We did not rate studies on whether participants were blind to their allocation to intervention or control groups. This would not be appropriate for studies of this type, as it would be impossible to blind participants to a physical activity intervention. Generation of a formal quality score for each study was completed on a four point scale assigning a value of 0 or 1 to each of the factors described below.

a) Was the randomisation method described? All studies reported using randomisation to allocate participants to intervention and control groups, but only 16 described the method of randomisation. Of these, four studies used cluster‐randomisation, where the unit of randomisation was participating practices (Norris 2000; Elley 2003), matched pairs of participating practices (Goldstein 1999), or workplace shifts (Reid 1979). One study used quasi‐randomisation ‐ days of the week (Smith 2000). All other studies randomised individuals.

b) Was the outcome assessment independent and blind? Twelve studies reported independent and blind outcome assessments (Dubbert 2002; Goldstein 1999; Green 2002; Harland 1999; Hillsdon 2002; King 1991; Marshall 2004; Petrella 2003; Pinto 2002; Simons‐Morton 2001a; Simons‐Morton 2001b; Smith 2000).

c) Was the final outcome measure controlled for baseline physical activity? Sixteen studies reported adjusting their final results for baseline values of physical activity (Calfas 2000; Green 2002; Hillsdon 2002; Inoue 2003; King 1988a; King 1988b; King 1991; Lamb 2002; Marshall 2003a; Norris 2000; Petrella 2003; Pinto 2002; Simons‐Morton 2001a; Simons‐Morton 2001b; Smith 2000; Stewart 2001).

d) Was the analysis an intention‐to‐treat analysis? Fourteen studies reported using an intention‐to‐treat analysis (Elley 2003; Hillsdon 2002; Kriska 1986; Lamb 2002; Lombard 1995; Marshall 2003a; Marshall 2004; Pinto 2002; Reid 1979; Simons‐Morton 2001a; Simons‐Morton 2001bSmith 2000; Stewart 2001; Stevens 1998). The remaining nine studies did not use an intention‐to‐treat analysis but had less than 20% loss to follow up. The proportion of participants in studies that did not perform an intention‐to‐treat analysis who were lost to follow up ranged from 0% to 18.9% (see Table 8).

8. Participation numbers in study recruitment, randomisation and follow up.

| Study ID | Potentially eligible | Eligible (b) | Randomised (c) | Complete (d) | % complete/eligible | % lost to follow up |

| Reid 1979 | Not stated | 146 | 124 | 34 | 23.2 | 72.5 |

| Kriska 1986 | Not stated | 229 | 229 | 229 | 100 | 8.7 |

| Cunningham 1987 | Not stated | 224 | 224 | 200 | 89.2 | 10.7 |

| Juneau 1987 | Not stated | 126 | 120 | 113 | 89.6 | 5.8 |

| King 1988a | Not stated | Not stated | 52 | 47 | Not available | 9.6 |

| King 1988b | Not stated | Not stated | 51 | 48 | Not available | 5.8 |

| King 1991 | 3117 | 1755 | 357 | 300 | 17.1 | 15.9 |

| Lombard 1995 | Approximately 5000 | 135 | 135 | 135 | 100 | 0 |

| Stevens 1998 | 2253 | 827 | 714 | 415 | 50.1 | 41.8 |

| Goldstein 1999 | 2145 | 444 | 355 | 312 | 70.2 | 12.1 |

| Harland 1999 | 2974 | 734 | 520 | 442 | 60.2 | 15.0 |

| Calfas 2000 | Not stated | Not stated | 338 | 315 (data provided by study authors) | Not available | 6.8 |

| Norris 2000 | 1920 | 985 | 847 | 812 | 82.4 | 4.1 |

| Smith 2000 | 2097 | 1214 | 1142 | 1101 | 90.6 | 17.1 |

| Simons‐Morton 2001a | 3910 | NS | 479 | 451 ‐ Self‐reported physical activity, 396 ‐ Cardio‐vascular fitness (data provided by study authors) | Not available | 5.8 ‐ Self‐reported physical activity, 17.3 ‐ Cardio‐vascular fitness |

| Simons‐Morton2001b | 3910 | NS | 395 | 349 ‐ Self‐reported physical activity, 302 ‐ Cardio‐vascular fitness (data provided by study authors) | Not available | 11.6 ‐ Self‐reported physical activity, 23.5 ‐ Cardio‐vascular fitness |

| Stewart 2001 | 1381 | 1053 | 173 | 164 | 15.5 | 5.0 |

| SSCT 2000 | 322 | 209 | 65 | 64 | 30.6 | 1.5 |

| Dubbert 2002 | 576 | 475 | 212 | 181 | 38.1 | 14.6 |

| Green 2002 | 1330 | 361 | 316 | 256 | 70.9 | 18.9 |

| Hillsdon 2002 | 5797 | 1658 | 1658 | 674 | 40.6 | 0.1 |

| Lamb 2002 | ˜2000 | 438 | 260 | 260 | 59.3 | 0 |

| Pinto 2002 | 1738 | 609 | 298 | 238 | 39.0 | 18.4 |

| Resnick 2002 | 120 | Not stated | 20 | 17 | Not stated | 15 |

| Elley 2003 | 2984 | 1364 | 878 | 878 | 64.3 | 0 |

| Inoue 2003 | 376 | 156 | 86 | 84 | 53.8 | 2.3 |

| Marshall 2003 | 927 | 738 | 462 | 462 | 62.6 | 0 |

| Petrella 2003 | 320 | 284 | 284 | 284 | 100 | 0 |

| Marshall 2004 | 1185 | 719 | 719 | 622 | 86.5 | 0 |

| (a) Number of people contacted to determine potential eligibility | (b) Number identified as eligible for study ‐ the number of participants who were assessed as eligible for randomisation into study | (c) Number of people randomised ‐ Number eligible minus refusals, excluded on medical grounds or failed to attend for randomisation | (d) Number with complete data set at final outcome measure | (e) % Number of participants with final outcome measure / Numbers identified as eligible for study |

Twenty‐three studies reported data for the number of those participants who completed their study and the number of participants eligible for the study before randomisation. We calculated the proportion of the eligible participants who completed the study and this percentage ranged from 15.5% to 100%. Table 8 presents the numbers of participants at different stages of each study. This data included the number of participants contacted to determine potential eligibility, number identified as eligible for study, number randomised, number with complete data at final outcome measure, number of participants with complete data at final outcome measure as a proportion of number identified as eligible for study and proportion of participants who were lost to follow‐up.

Details of the intensity of the interventions studied, control interventions used and length of follow‐up are in Table 9 and Table 10.

9. Characteristics of study type and intensity of intervention and follow up.

| Study ID & Author | Programme direction | Supervision | Rate of intervention | Rate of Follow Up | Contact at Follow up |

| Reid 1979 | P ‐ prescribed by professional only | US ‐ physical activity programme was unstructured and performed independently by the participant | High ‐ 3+ occasions | High 3+ occasions between week five and outcome measure. | Mixture of postal, telephone or face‐to‐face |

| Kriska 1986 | P ‐ prescribed by professional only | Mixed ‐ physical activity programme was structured (S) and unstructured (US) | High ‐ 3+ occasions | High 3+ occasions between week five and outcome measure. | Mixture of postal, telephone or face‐to‐face |

| Cunningham 1987 | P ‐ prescribed by professional only | Mixed ‐ physical activity programme was structured (S) and unstructured (US) | High ‐ 3+ occasions | High 3+ occasions between week five and outcome measure. | Face‐to‐face |

| Juneau 1987 | P ‐ prescribed by professional only | US ‐ physical activity programme was unstructured and performed independently by the participant | Low ‐ 0‐1 occasions | Low ‐ 0‐1 occasions between week five and outcome measure. | None |

| King 1988 a | SD self directed only | US ‐ physical activity programme was unstructured and performed independently by the participant | Med ‐ 2 occasions | Low ‐ 0‐1 occasions between week five and outcome measure. | None |

| King 1988 b | SD self directed only | US ‐ physical activity programme was unstructured and performed independently by the participant | High ‐ 3+ occasions | High 3+ occasions between week five and outcome measure. | Telephone only |

| King 1991 | P ‐ prescribed by professional only | Mixed ‐ physical activity programme was structured (S) and unstructured (US) | High ‐ 3+ occasions | High 3+ occasions between week five and outcome measure. | Mixture of postal, telephone or face‐to‐face |

| Lombard 1995 | P ‐ prescribed by professional only | US ‐ physical activity programme was unstructured and performed independently by the participant | Low ‐ 0‐1 occasions | High 3+ occasions between week five and outcome measure. | Telephone only |

| Stevens 1998 | SD self directed only | US ‐ physical activity programme was unstructured and performed independently by the participant | Low ‐ 0‐1 occasions | Low ‐ 0‐1 occasions between week five and outcome measure. | Face‐to‐face |

| Goldstein 1999 | SD+ self directed plus professional guidance | US ‐ physical activity programme was unstructured and performed independently by the participant | Med ‐ 2 occasions | High 3+ occasions between week five and outcome measure. | Mixture of postal, telephone or face‐to‐face |

| Harland 1999 | SD+ self directed plus professional guidance | US ‐ physical activity programme was unstructured and performed independently by the participant | High ‐ 3+ occasions | High 3+ occasions between week five and outcome measure. | Face‐to‐face |

| Calfas 2000 | SD+ self directed plus professional guidance | US ‐ physical activity programme was unstructured and performed independently by the participant | High ‐ 3+ occasions | High 3+ occasions between week five and outcome measure. | Mixture of postal, telephone or face‐to‐face |

| Norris 2000 | SD+ self directed plus professional guidance | US ‐ physical activity programme was unstructured and performed independently by the participant | High ‐ 3+ occasions | High 3+ occasions between week five and outcome measure. | Mixture of postal, telephone or face‐to‐face |

| Smith 2000 | P ‐ prescribed by professional only | US ‐ physical activity programme was unstructured and performed independently by the participant | Med ‐ 2 occasions | Low ‐ 0‐1 occasions between week five and outcome measure. | Mixture of postal, telephone or face‐to‐face |

| Simons‐Morton 2001a | SD+ self directed plus professional guidance | US ‐ physical activity programme was unstructured and performed independently by the participant | High ‐ 3+ occasions | High 3+ occasions between week five and outcome measure. | Mixture of postal, telephone or face‐to‐face |

| Simons‐Morton 2001b | SD+ self directed plus professional guidance | US ‐ physical activity programme was unstructured and performed independently by the participant | High ‐ 3+ occasions | High 3+ occasions between week five and outcome measure. | Mixture of postal, telephone or face‐to‐face |

| Stewart 2001 | SD+ self directed plus professional guidance | US ‐ physical activity programme was unstructured and performed independently by the participant | High ‐ 3+ occasions | High 3+ occasions between week five and outcome measure. | Mixture of postal, telephone or face‐to‐face |

| SSCT 2000 | P ‐ prescribed by professional only | S ‐ physical activity programme was structured and supervised by professional | High ‐ 3+ occasions | High 3+ occasions between week five and outcome measure. | Mixture of postal, telephone or face‐to‐face |

| Dubbert 2002 | SD ‐ self directed only | US ‐ physical activity programme was unstructured and performed independently by the participant | High ‐ 3+ occasions | High 3+ occasions between week five and outcome measure. | Mixture of postal, telephone or face‐to‐face |

| Green 2002 | SD ‐ self directed only | US ‐ physical activity programme was unstructured and performed independently by the participant | High ‐ 3+ occasions | High 3+ occasions between week five and outcome measure. | Telephone only |

| Hillsdon 2002 | SD ‐ self directed only | US ‐ physical activity programme was unstructured and performed independently by the participant | Low ‐ 0‐1 occasions | High 3+ occasions between week five and outcome measure. | Telephone only |

| Lamb 2002 | SD+ self directed plus professional guidance | Mixed ‐ physical activity programme was structured (S) and unstructured (US) | Low ‐ 0‐1 occasions | Low ‐ 0‐1 occasions between week five and outcome measure. | Mixture of postal, telephone or face‐to‐face |

| Pinto 2002 | SD ‐ self directed only | US ‐ physical activity programme was unstructured and performed independently by the participant | High ‐ 3+ occasions | High 3+ occasions between week five and outcome measure. | Mixture of postal, telephone or face‐to‐face |

| Resnick 2002 | P ‐ prescribed by professional only | Mixed ‐ physical activity programme was structured (S) and unstructured (US) | High ‐ 3+ occasions | High 3+ occasions between week five and outcome measure. | Mixture of postal, telephone or face‐to‐face |

| Elley 2003 | SD+ self directed plus professional guidance | US ‐ physical activity programme was unstructured and performed independently by the participant | Low ‐ 0‐1 occasions | Low ‐ 0‐1 occasions between week five and outcome measure. | Mixture of postal, telephone or face‐to‐face |

| Inoue 2003 | SD+ self directed plus professional guidance | Mixed ‐ physical activity programme was structured (S) and unstructured (US) | High ‐ 3+ occasions | Low ‐ 0‐1 occasions between week five and outcome measure. | Postal only |

| Marshall 2003 | SD ‐ self directed only | US ‐ physical activity programme was unstructured and performed independently by the participant | Low ‐ 0‐1 occasions | Low ‐ 0‐1 occasions between week five and outcome measure. | None |

| Petrella 2003 | SD ‐ self directed only | US ‐ physical activity programme was unstructured and performed independently by the participant | Low ‐ 0‐1 occasions | Low ‐ 0‐1 occasions between week five and outcome measure. | Face‐to‐face |

| Marshall 2004 | SD ‐ self directed only | US ‐ physical activity programme was unstructured and performed independently by the participant | Low ‐ 0‐1 occasions | Low ‐ 0‐1 occasions between week five and outcome measure. | None |

| (a) Nature of direction of the intervention | (b) Degree of programme supervision ‐ S ‐ physical activity programme was structured and supervised by professional, US ‐ physical activity programme was unstructured and performed independently by the participant | (c) Frequency of intervention occasions in first four weeks post baseline. | (d) Frequency of follow up contacts. | (e) Type of follow up contacts |

10. Characteristics of study control groups and number of study arms.

| Study ID | No. study arms (a) | Description (b) | Type of control (c) |

| Reid 1979 | 2 | Written advice | Comparison control |

| Kriska 1986 | 2 | Baseline assessment only | No contact |

| Cunningham 1987 | 2 | Continue usual physical activity | No contact |

| Juneau 1987 | 2 | Daily physical activity logs | Comparison control |

| King 1988a | 2 | Weekly exercise monitoring | Comparison control |

| King 1988b | 2 | Self monitoring materials and pulse monitor | Comparison control |

| King 1991 | 4 | Asked not to change physical activity | No contact |

| Lombard 1995 | 2 | Written information | Comparison control |

| Stevens 1998 | 2 | Written information | Comparison control |

| Goldstein 1999 | 2 | Usual care | Attention control |

| Harland 1999 | 5 | Health check | Attention control |

| Calfas 2000 | 2 | General health lectures | Attention control |

| Norris 2000 | 3 | Usual care | No contact |

| Smith 2000 | 3 | Usual care | No contact |

| Simons‐Morton 2001a | 3 | Advice to exercise from physician & health educator | Comparison control |

| Simons‐Morton 2001b | 3 | Advice to exercise from physician & health educator | Comparison control |

| Stewart 2001 | 2 | Wait list | No contact |

| SSCT 2000 | 2 | Attend weekly lecture and indoor games | Attention control |

| Dubbert 2002 | 3 | Wait list | Comparison control |

| Green 2002 | 2 | Self help materials only | Comparison control |

| Hillsdon 2002 | 3 | Wait list | Attention control |

| Lamb 2002 | 2 | Group seminar and advice to exercise | Comparison control |

| Pinto 2002 | 2 | Computer‐based phone calls | Attention control |

| Resnick 2002 | 2 | Routine care | Attention control |

| Elley 2003 | 2 | Usual care and wait list | Attention control |

| Inoue 2003 | 2 | Baseline assessments only | No contact |

| Marshall 2003 | 2 | Assessments only | Attention control |

| Petrella 2003 | 2 | Exercise counselling, advice and record their exercise weekly in a diary | Comparison control |

| Marshall 2004 | 2 | Assessments only | Attention control |

| (a) Number of study arms ‐ This figure is a sum of the number of intervention arms plus control | (b) Description of control group | (c) Type of control group ‐ No contact ‐ Wait list, baseline assessment only, Attention control ‐ Usual care, health check, health advice not physical activity specific, Comparison control ‐ Written information, advice about physical activity, self monitoring materials |

Effects of interventions

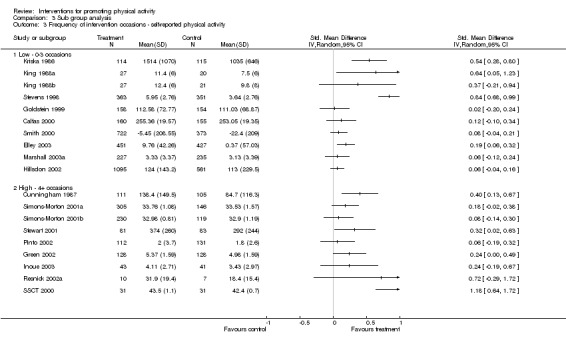

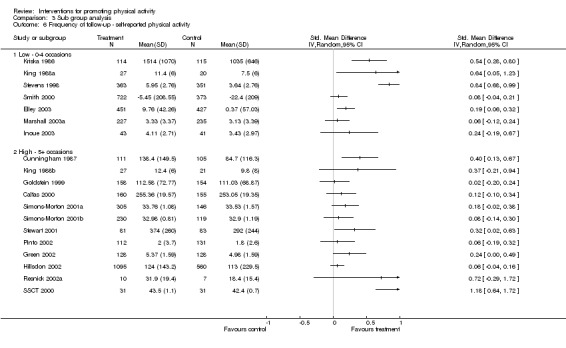

Self‐reported physical activity

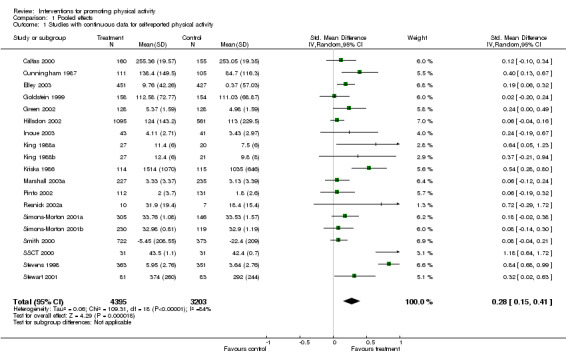

Reported as a continuous measure Nineteen studies (7,598 participants) reported their main outcome as one of several continuous measures of physical activity (Calfas 2000; Cunningham 1987; Elley 2003; Goldstein 1999; Green 2002; Hillsdon 2002; Inoue 2003; King 1988a; King 1988b; Kriska 1986; Marshall 2003a; Pinto 2002; Resnick 2002a; Simons‐Morton 2001a; Simons‐Morton 2001b; Smith 2000; SSCT 2000; Stevens 1998; Stewart 2001). Measures included estimated energy expenditure (kcals/day, kcals/week of moderate physical activity), total time of physical activity (mean mins/week of moderate physical activity) and mean number of occasions of physical activity in past four weeks. The pooled effect of these studies was positive but moderate (SMD 0.28, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.41) with significant heterogeneity in observed effects (I2 = 83.5%). Seven studies reported positive effects (Cunningham 1987; Elley 2003; King 1988a; Kriska 1986; Stevens 1998; SSCT 2000; Stewart 2001) (see Table 11).

11. Outcome measure, SMD, 95% CI for studies with continuous self‐reported PA.

| Study ID | Outcome measure | SMD | 95% CI | Outcome direction | Study quality score |

| Kriska 1986 | Kcal/week | 0.54 | 0.28 to 0.80 | + favours intervention | 1 |

| Cunningham 1987 | Mins/day vigorous physical activity (>4.9 METS) | 0.40 | 0.13 to 0.67 | + favours intervention | 0 |

| King 1998a | Exercise occasions per month (30 Mins. per session) | 0.64 | 0.05 to 1.23 | + favours intervention | 2 |

| King 1988b | Exercise occasions per month (30 Mins. per session) | 0.37 | ‐0.21 to 0.94 | 0 no effect | 2 |

| Stevens 1998 | Exercise occasions per month (greater than 20 Mins per session) | 0.84 | 0.68 to 0.99 | + favours intervention | 2 |

| Goldstein 1999 | Physical Activity Scale for Elderly (PASE Scale) | 0.02 | ‐0.20 to 0.24 | 0 no effect | 0 |

| Calfas 2000 | Kcal/kg/week | 0.12 | ‐0.10 to 0.34 | 0 no effect | 1 |

| Smith 2000 | Mins/week | 0.08 | ‐0.04 to 0.21 | 0 no effect | 3 |

| Simons‐Morton 2001a | Kcal/kg/day | 0.18 | ‐0.02 to 0.38 | 0 no effect | 4 |

| Simons‐Morton 2001a | Kcal/kg/day | 0.08 | ‐0.14 to 0.30 | 0 no effect | 4 |

| Stewart 2001 | Kcal/day | 0.32 | 0.02 to 0.63 | + favours intervention | 3 |

| SSCT 2000 | Total daily energy expenditure (kcal/kg/day) | 1.18 | 0.64 to 1.72 | + favours intervention | 1 |

| Green 2002 | Self reported physical activity PACE score | 0.24 | 0.00 to 0.49 | 0 no effect | 3 |

| Hillsdon 2002 | Energy expenditure (kcal/kg/week) | 0.06 | ‐0.04 to 0.16 | 0 no effect | 3 |

| Pinto 2002 | Moderate intensity physical activity (kcal/week) | 0.06 | ‐0.19 to 0.32 | 0 no effect | 2 |

| Resnick 2002 | Energy expenditure | 0.72 | ‐0.29 to 1.72 | 0 no effect | 0 |

| Elley 2003 | Energy expenditure (kcal/kg/week) | 0.19 | 0.06 to 0.32 | + favours intervention | 1 |

| Inoue 2003 | Moderate intensity physical activity (kcal/week) | 0.24 | ‐0.19 to 0.67 | 0 no effect | 1 |

| Marshall 2003 | Total physical activity (hrs/week) | 0.06 | ‐0.12 to 0.24 | 0 no effect | 2 |

| METS = Energy cost of physical activity measured at cost of basal metabolic rate. |

Studies with positive SMDs used a range of different intervention approaches with varying effect sizes. Kriska 1986 found that encouraging walking via an 8‐week training programme, followed by a choice of group or independent walking, plus follow‐up phone calls and incentives resulted in a mean increase of 479 kcal/week (95% CI 249 to 708) of physical activity of all intensities. Cunningham 1987 found that encouragement to attend three group exercise sessions per week and perform an additional weekly exercise session at home resulted in an additional mean 53.7 minutes of vigorous physical activity per day (95% CI 18.09 to 89.31).

King 1988a found a mean increase of 3.90 exercise sessions per month (95% CI 0.43 to 7.37), at 6 months, following 30 minutes of baseline instruction (15 minutes of advice and a 15 minute video about exercise training), and daily self monitoring of physical activity using exercise logs returned to staff every month. These additional sessions were approximately equivalent to 101 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity per week. Stevens 1998 saw a net difference between intervention and control groups of 2.31 'sessions' (one session was at least 20 minutes of continuous physical activity) of moderate or vigorous exercise per month (95% CI 1.91 to 2.71). At an initial meeting with a community exercise development officer intervention participants were encouraged to extend a physical activity that they already did rather than start a new activity. A further meeting was offered ten weeks later to support and encourage any changes. Stewart 2001 reported a significant net difference of 82 kcal per day between the intervention and control arms (95% CI 73.9 to 90.1). The intervention group received face‐to‐face counselling based on social cognitive theory (Bandura 1986). In addition they were offered further individual follow up appointments, educational materials, phone calls and monthly workshops about physical activity.

Elley 2003 reported a between group mean difference of 2.67 kcal/kg/wk (95% CI 0.48 to 4.86). The authors estimate this was equivalent to a net difference of 247 kcals/week between groups. The intervention group received motivational counselling from their general practitioner, followed by three follow up phone calls from a local exercise specialist, plus written materials. Participants were asked to choose their own physical activity.

SSCT 2000 reported a large increase in mean self‐reported physical activity in their intervention group. However the physical activity regime was very prescriptive. Participants were encouraged to attend at least two from three 2‐hour exercise classes per week, held at a local community centre. The class contained endurance and resistance training typically involving 10‐25 minutes of static cycling at prescribed heart rate reserve, with intensity monitored by heart monitors. In addition to attending classes participants were asked to monitor their walking behaviour using pedometers.

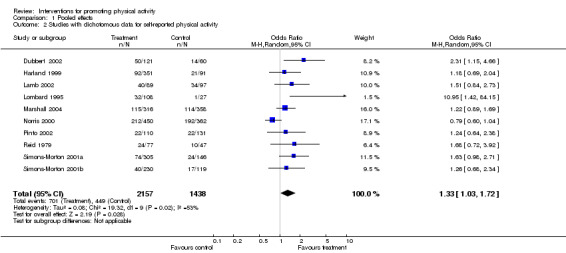

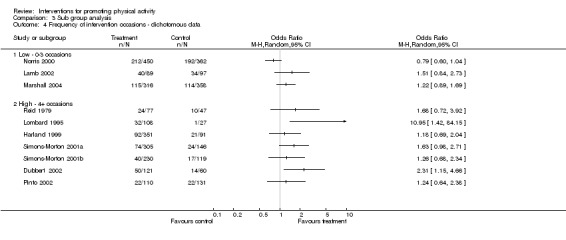

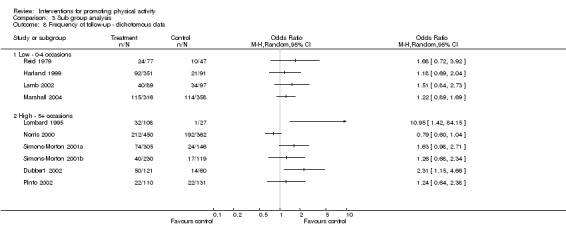

No statistically significant effects were observed for the other 12 studies (Calfas 2000; Goldstein 1999; Green 2002; Hillsdon 2002; Inoue 2003; King 1988b; Marshall 2003a; Pinto 2002; Resnick 2002a; Simons‐Morton 2001a; Simons‐Morton 2001b; Smith 2000). No studies had effects that favoured controls. Reported as a dichotomous measure Ten studies (3595 participants) reported physical activity as a dichotomous measure which represented achievement or not of a predetermined level of physical activity (Dubbert 2002; Harland 1999; Lamb 2002; Lombard 1995; Marshall 2004; Norris 2000; Pinto 2002; Reid 1979; Simons‐Morton 2001a; Simons‐Morton 2001b). The pooled odds ratio of these studies was positive but modest (OR 1.33, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.72) with significant heterogeneity in observed effects (I2 = 53.4%). Only two studies reported a significantly positive effect (Dubbert 2002; Lombard 1995). Lombard 1995 found that participants who received a high frequency of follow up telephone calls (10 calls over 12 weeks) were more successful at changing their walking behaviour than participants who did not receive telephone calls (OR 10.95, 95% CI 1.42 to 84.15). Dubbert 2002 found that adult participants who received a video, walking plan, weekly walking diary, financial incentive for completing diary, plus follow up phone calls were more successful at adhering to a 3 walks per week programme that participants who did not receive any phone calls (OR 2.31, 95% CI 1.15 to 4.66) (see Table 12).

12. Outcome measure, OR, 95% CI for studies with dichotomous physical activity.

| Study ID | Outcome measure | OR | 95% CI | Outcome direction | Study quality score |

| Reid 1979 | Improving physical activity compliance and fitness increase (OR for a participant achieving "prescribed compliance" if they reported exercising at least twice a week and increased their VO2 by +9.5% over baseline level) | 1.68 | 0.72 to 3.92 | 0 no effect | 1 |

| Lombard 1995 | Achieving at least 3 occasions of walking for at least 20 minutes per week (OR for a participant walking on least 3 occasions per week for at least 20 minutes per occasion) | 10.95 | 1.42 to 84.15 | + favours treatment | 1 |

| Harland 1999 | Improving physical activity index score by at least one level (OR for a participant increasing their number of sessions of moderate and vigorous physical activity lasting a minimum of 20 minutes in the previous four weeks, used in a physical activity index score) | 1.18 | 0.69 to 2.04 | 0 no effect | 2 |

| Norris 2000 | Increasing physical activity by at least 30 minutes per week (OR for a participant increasing their level of any type of physical activity by at least 30 minutes per week compared to their baseline level) | 0.79 | 0.60 to 1.04 | 0 no effect | 2 |

| Simons‐Morton 2001a | Meeting CDC recommendation for physical activity (Odds ratio for a participant meeting 30 minutes of moderate to vigorous intensity physical activity (at least 3 METS) at least 5 days a week, 30 minutes of vigorous physical activity (at least 5 METS) at least 3 days a week, or at least 2 kcal·kg‐1·day‐1 in moderate to vigorous physical activity) | 1.63 | 0.98 to 2.71 | 0 no effect | 4 |

| Simons‐Morton 2001b | Meeting CDC recommendation for physical activity (Odds ratio for a participant meeting 30 minutes of moderate to vigorous intensity physical activity (at least 3 METS) at least 5 days a week, 30 minutes of vigorous physical activity (at least 5 METS) at least 3 days a week, or at least 2 kcal·kg‐1·day‐1 in moderate to vigorous physical activity) | 1.26 | 0.68 to 2.34 | 0 no effect | 4 |

| Dubbert 2002 | Achieving exercise adherence goal of walking 20 min 3 days/week | 2.31 | 1.15 to 4.66 | + favours treatment | 1 |

| Lamb 2002 | Achieving more than 120 minutes per week moderate physical activity | 1.51 | 0.84 to 2.74 | 0 no effect | 3 |

| Pinto 2002 | Meeting CDC/ACSM recommendation for moderate physical activity | 1.24 | 0.64 to 2.38 | 0 no effect | 2 |

| Marshall 2004 | Achieving a sufficient level of physical activity | 1.22 | 0.89 to 1.69 | 0 no effect | 1 |

| CDC = Centre for disease control |

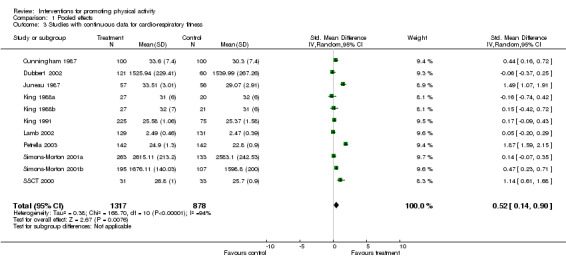

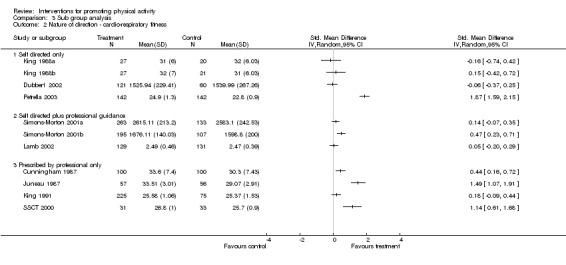

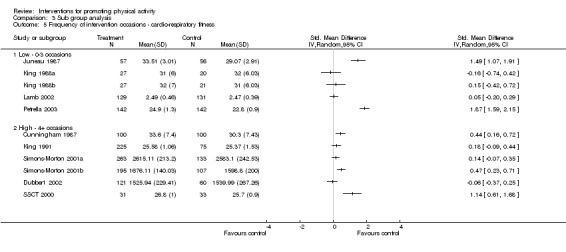

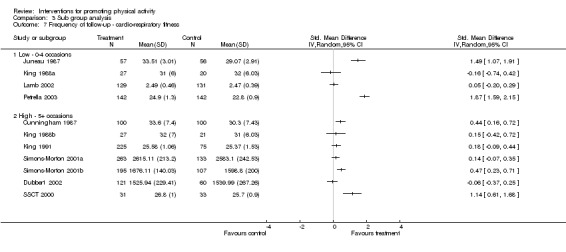

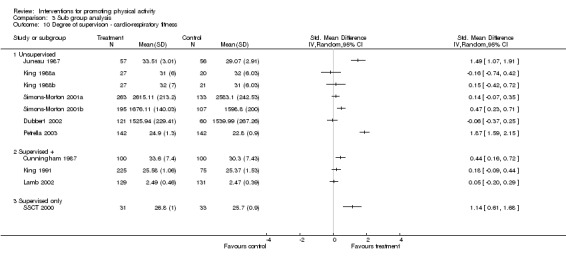

No effect was found in eight studies (Harland 1999; Lamb 2002; Marshall 2004; Norris 2000; Pinto 2002; Reid 1979; Simons‐Morton 2001a; Simons‐Morton 2001b). No studies had effects that favoured controls. Cardio‐respiratory fitness In addition to self‐reported physical activity, 11 studies (2195 participants) examined the effect of their intervention on cardio‐respiratory fitness (Cunningham 1987; Dubbert 2002; Juneau 1987; King 1988a; King 1988b; King 1991; Lamb 2002; Petrella 2003; Simons‐Morton 2001a; Simons‐Morton 2001b; SSCT 2000) (see Table 13). The pooled effect was again positive and moderate with significant heterogeneity in the observed effects (SMD 0.52 95% CI 0.14 to 0.90). Five studies (1359 participants) had significant positive effects that favoured treatment (Cunningham 1987; Juneau 1987; Petrella 2003; Simons‐Morton 2001b; SSCT 2000). Cunningham 1987 reported that recently retired men who were offered supervised exercise sessions increased their fitness by a greater amount than controls who continued with their usual physical activity programmes (SMD 0.44 95% CI 0.16 to 0.72). Juneau 1987 found a mean increase in fitness (SMD 1.49 95% CI 1.07 to 1.91) for participants who received a combination of a 30‐minute consultation, an educational video, information on using a heart rate monitor and a daily physical activity log, compared to controls. Simons‐Morton 2001b found that women who received an intensive mixture of behavioural counselling, support materials and telephone calls (assistance + counselling arms) were more likely to increase their fitness (SMD 0.47, 95% CI 0.23 to 0.71) than women who received a less intensive intervention (advice arm only). Petrella 2003 evaluated the effects of a fitness assessment using a step test and counselling from physician, plus a simple target heart rate goal and recording their physical activity in a diary on cardio‐respiratory fitness. Controls received the same intervention without the heart rate goal setting. The standardised mean difference was 1.87 (95% CI 1.59 to 2.15).

13. Outcome measure, SMD, 95% CI for studies with continuous cardio‐respir fitness.

| Study ID | Outcome measure | SMD | 95% CI | Outcome direction | Study quality score |

| Cunningham 1987 | VO2 | 0.44 | 0.16 to 0.72 | + favours treatment | 0 |

| Juneau 1987 | VO2 | 1.49 | 1.07 to 1.91 | + favours treatment | 0 |

| King 1988a | VO2 | ‐0.16 | ‐0.74 to 0.42 | 0 no effect | 2 |

| King 1988b | VO2 | 0.15 | ‐0.42 to 0.72 | 0 no effect | 2 |

| King 1991 | VO2 | 0.17 | ‐0.09 to 0.43 | 0 no effect | 3 |

| Simons‐Morton 2001a | VO2 | 0.14 | ‐0.07 to 0.35 | 0 no effect | 4 |

| Simons‐Morton 2001b | VO2 | 0.47 | 0.23 to 0.71 | + favours treatment | 4 |

| SSCT 2000 | VO2 | 1.14 | 0.61 to 1.68 | + favours treatment | 1 |

| Dubbert 2002 | VO2 | ‐0.06 | ‐0.37 to 0.25 | 0 no effect | 1 |

| Lamb 2002 | VO2 | 0.05 | ‐0.20 to 0.29 | 0 no effect | 3 |

| Petrella 2003 | VO2 | 1.87 | 1.59 to 2.15 | + favours treatment | 3 |

Although King 1991 reported a significant difference in VO2 max between intervention and control group at 12‐months follow‐up this difference did not remain when based on the standardised mean difference of the pooled intervention arms (SMD 0.17, 95% CI ‐0.09 to 0.43). In one other study (King 1988b), the author reported a significant difference in the change in fitness between groups, which did not remain significant when based on standardised mean differences at 12 month follow up using their published data. This may be an effect of pooling study arms.

Adverse events Eight studies reported data on adverse events. Only one study found a difference in the rate of adverse events between the intervention and control groups. Reid 1979 reported the rate of job‐related injuries was four times higher in the control group compared to the intervention group. The other seven studies reported no significant difference in rates of musculoskeletal injury (fractures and sprains), falls, illness and potential cardiovascular events between groups (Dubbert 2002; Elley 2003; King 1991; Resnick 2002a; Simons‐Morton 2001a; Simons‐Morton 2001b; SSCT 2000).

Sensitivity analysis by study quality We examined the pooled effects for the three types of outcome data (self‐reported physical activity, dichotomous and cardio‐respiratory fitness outcomes) by an assessment of study quality. High quality studies scored more than 2 on the quality scale. A score of 2 or less was categorised as low quality. For the 19 studies that reported continuous outcomes for physical activity six were classified as high quality (comparison 02 01). The pooled effect of these interventions was again positive with no significant heterogeneity in the observed effects; the standardised mean difference was 0.11 (95% CI 0.04 to 0.17). Lower quality studies also had a positive pooled effect but with significant heterogeneity in the observed effects; the standardised mean difference was 0.36 (95% CI 0.17 to 0.56).

We found three high quality scoring studies from the 10 studies that reported dichotomous outcome data for self‐reported physical activity (comparison 02 02). The pooled odds ratio of these three studies was positive but modest (OR 1.48, 95% CI 1.07 to 2.06) with no significant heterogeneity in observed effects.

We found five high quality studies from the 11 studies that reported continuous outcome data for cardio‐respiratory fitness (comparison 02 03). The pooled effects of these studies was not significant and there was significant heterogeneity (SMD 0.54, 95% CI ‐0.07 to 1.14). We noted two studies had a string effect on the pooled analysis (Juneau 1987; Petrella 2003).

Secondary objectives

a) Are more intense interventions more effective in changing physical activity than less intense interventions? Two studies attempted to investigate the effect of increasing intervention intensity. In Simons‐Morton 2001a and Simons‐Morton 2001b the three groups received different levels of intervention. The control group (advice) received physician advice to achieve the recommended level for exercise, then referral to an on‐site health educator. At this appointment the health educator provided educational materials and repeated the physician advice to exercise with further follow‐up appointments repeating this advice. No other follow‐up activities were offered. The assistance group received the same advice from a physician and also received a 30‐40 minute counselling session the health educator conducted, including a videotape and action planning. Participants then received follow‐up phone calls, interactive mail, an electronic step counter, and monthly monitoring cards, which were returned to the health educator. Follow‐up mail and incentives were sent to all participants. The counselling group received all of the components of the advice and assistance group with additional bi‐weekly telephone calls for 6 weeks and then monthly telephone calls up to 12 months. Frequency of telephone calls for the final 12 months of the study was negotiated between the participant and their health educator. Weekly behavioural classes on skills for adopting and maintaining physical activity were also offered to this group. In women, the addition of behavioural counselling, follow up support and materials produced a significant difference in fitness compared to the control groups. In men addition of these components did not lead to greater change (Simons‐Morton 2001a and Simons‐Morton 2001b).

b) Are specific components of interventions associated with changes in physical activity behaviour? We stratified the behavioural components of the interventions, according to a number of characteristics. These characteristics were the degree of nature of direction (the extent to which physical activity was prescribed or self‐directed) and the level of on‐going professional support (frequency of follow up after week five of the study). Although there were insufficient studies to statistically test the difference in observed effects between these various study characteristics, the significant heterogeneity in reported effects was reduced when physical activity was self‐directed with some professional guidance and when there was on‐going professional support (in studies with continuous outcome measures for self‐reported physical activity).

c) Are short term changes in physical activity or fitness maintained at 12 months? Six studies reported outcomes more than 6 months after the initial intervention (e.g. at least a measure of the primary outcome at 6 months and 12 months post intervention). In King 1991 improvements in physical activity and cardio‐respiratory fitness at 6 months were maintained at 12 months for cardio‐respiratory fitness only. Simons‐Morton 2001a and Simons‐Morton 2001b presented data for cardio‐respiratory fitness and self‐reported physical activity at 6 and 24 months. All three study arms increased their cardio respiratory fitness and self reported levels of physical activity between baseline and 6 months. However there were no significant differences between groups. At 24 months there was a significant difference in VO2 max between participants who received assistance and counselling compared to the advice group for women only (Simons‐Morton 2001b). Calfas 2000 reported outcomes at 12 and 24 months with no significant effect observed at either time points. Lamb 2002 reported no significant effect in the likelihood of increasing walking at 6 and 12 months. Petrella 2003 reported a significant increase in cardio‐respiratory fitness at 6 months and this effect was further increased at 12 months.

d) Is the promotion of some types of physical activity more likely to lead to change than other types of physical activity? We were unable to determine if any type of physical activity is more likely to be adopted than any other type of physical activity, (e.g. walking, jogging or running) as the studies were not designed to examine this question and as such generally did not report exactly what type of physical activity was performed. e) Are home‐based interventions more successful than facility‐based interventions? No study specifically examined this question. However King 1991 compared the difference in adherence to prescribed physical activity sessions between participants who were prescribed home‐based versus facility‐based exercise. A greater number of participants completed at least 75% of prescribed exercise sessions in both home‐based arms compared to the facility‐based arms (P < 0.05). This improved adherence to the home‐based exercise sessions was not reflected in greater improvements in fitness. f) Are interventions more successful with particular participant groups? Nine studies examined the differential effects of the interventions within various sub‐groups.

Eight studies looked at the effect of gender (Calfas 2000; Elley 2003; Juneau 1987; King 1991; Petrella 2003; Simons‐Morton 2001a; Simons‐Morton 2001b; Stewart 2001). Greater effects were seen for improvements in cardio‐respiratory fitness for women as compared to men in King 1991 and Simons‐Morton 2001a and Simons‐Morton 2001b, while Juneau 1987 reported a greater increase in VO2 max in men than women. Elley 2003 reported greater increases in men compared to women in the intervention group in reported physical activity.

Two studies found no differential effects between high and low levels of baseline self‐reported physical activity (Petrella 2003; Stewart 2001). No effects were seen for age (above or below 75 years) in Stewart 2001. The same study found a greater increase in physical activity for overweight participants (BMI more than 27.0), compared with participants who were not overweight (Stewart 2001). Petrella 2003 examined differential effects of their intervention in four sub groups (i) gender, (ii) age (above versus below 70 years), (iii) chronic health conditions (less than two reported health conditions versus more two or more health conditions) and (iv) BMI (<27, 27‐31, >32 BMI). The intervention group showed a greater improvement in cardio‐respiratory fitness compared to the control group, in a between group analysis regardless of gender, age, having more than 2 chronic health conditions and BMI >32.

Discussion

Our updated review suggests that physical activity interventions have a positive moderate sized effect on increasing self‐reported physical activity and measured cardio‐respiratory fitness, at least in the short to mid‐term. Any conclusions drawn from this review require some caution given the significant heterogeneity in the observed effects. Despite the heterogeneity between the studies, there is some indication that a mixture of professional guidance and self direction plus on‐going professional support leads to more consistent effect estimates. The long‐term effectiveness of these interventions is not established as the majority of studies stopped after 12 months.

These conclusions differ from the findings of previous systematic reviews (Hillsdon 1996; Hillsdon 1999). Earlier reviews concluded that interventions that encouraged home‐based activity were more effective than facility‐based activity interventions. This review used more rigid inclusion criteria (for example outcome measures with at least 6 months follow‐up) and subsequently excluded some studies included in these previous reviews. We were also able to collect unpublished data from study authors and this allowed us to perform a quantitative analysis using standardised mean differences for effects as opposed to just descriptions alone. The conclusions are similar to another published review (Hillsdon 2004). However this review was not a synthesis of primary studies but rather a synthesis of high‐quality systematic reviews and meta‐analyses of studies to increase physical activity among adults. It assessed studies in particular settings and found strong evidence of effectiveness of interventions within healthcare and community settings, particularly brief advice from a health professional, supported by written materials, which is likely to be effective in producing a modest, short‐term (6‐12 weeks) effect on physical activity (Hillsdon 2004).

The findings of this review are in contrast to the conclusions of a review produced by the Center for Disease Control (Kahn 2002). Kahn 2002 examined the effectiveness of individual‐based behavioural interventions for the promotion of physical activity. The review calculated effects as the net percent change from baseline ‐ the median change scores. In 10 studies (using continuous outcome measures of self‐reported physical activity), the authors found a median net increase of 35.4% (interquartile range, 16.7% to 83.3%). Ten studies measured change in the time spent in physical activity, with a net median increase of 64.3% (interquartile range, 1.2% to 85.5%). Four studies measured change in VO2max with a median increase of 6.3% (interquartile range, 5.1% to 9.8%). Overall the authors concluded that there was "good" evidence to suggest that this type of intervention was effective in increasing physical activity. However the authors included studies with shorter periods of follow up, non randomised studies (including uncontrolled before and after studies), and did not take account of loss to follow up. Only one study, King 1991, was shared by both reviews.

Quality of the evidence The quality of the studies in this current review was limited by a lack of intention‐to‐treat analysis and failure to examine the interaction between baseline levels of physical activity and exposure to the intervention. Only six studies (Green 2002; Hillsdon 2002; Lamb 2002; Petrella 2003; Simons‐Morton 2001a; Simons‐Morton 2001b) achieved all of the quality criteria. The observed effects were smaller but more consistent in studies with higher quality scores.

Internal validity We found three main weaknesses to the studies in terms of their internal validity. First, none of the studies were able to blind participants to their allocation to intervention at baseline. However this criterion is not appropriate to such studies. It is very difficult to blind a participant to their study group if exercise is the intervention. This element of quality is more appropriate to pharmaceutical interventions where blinding for both researchers and participants reduces the risk of selection bias. Second, studies failed to state their randomisation methods. And third, the studies did not use personnel to collect main outcome measures that were independent and blinded to group allocation.

Misclassification of physical activity also threatens internal validity of studies. The insensitivity of self‐reported physical activity measures leads to less precision in its measurement and increases the variance in measures of behaviour. As intervention and control group participants completed the same self‐report measure, any misclassification is likely to be non‐differential leading to an attenuation of the effect of the intervention. This problem would not apply to measures of cardio‐respiratory fitness. External validity Limitations in the external validity of the studies relate to recruitment and screening of participants and the generalisability of the interventions into everyday practice.