Abstract

Viruses use virions to spread between hosts, and virion composition is therefore the primary determinant of viral transmissibility and immunogenicity. However, the virions of many viruses are complex and pleomorphic, making them difficult to analyse in detail. Here we address this by identifying and quantifying virion proteins with mass spectrometry, producing a complete and quantified model of the hundreds of viral and host-encoded proteins that make up the pleomorphic virions of influenza viruses. We show that a conserved influenza virion architecture is maintained across diverse combinations of virus and host. This ‘core’ architecture, which includes substantial quantities of host proteins as well as the viral protein NS1, is elaborated with abundant host-dependent features. As a result, influenza virions produced by mammalian and avian hosts have distinct protein compositions. Finally we note that influenza virions share an underlying protein composition with exosomes, suggesting that influenza virions form by subverting microvesicle production.

Keywords: influenza virus, mass spectrometry, host factors, tetraspanins, NS1

Introduction

Viruses, unlike other parasitic nucleic acids, can cause infected cells to produce virions. These extracellular structures allow copies of the viral genome to be transferred to new hosts, and their composition is therefore the primary determinant of the stability, transmissibility, tropism and immunogenicity of a virus. Virions are assembled from virally-encoded proteins and may also include proteins encoded by the host, particularly if the virion incorporates an envelope of host membrane. While some virions have a regular architecture whose structure can be clearly determined, many important viral pathogens have pleomorphic virions whose structure can only be determined with difficulty and through the combination of different techniques. In this study we have used mass spectrometry as an alternative approach for the detailed characterisation of pleomorphic virions.

Influenza viruses are serious clinical and veterinary pathogens which cause epithelial cells to produce enveloped, pleomorphic virions1-6. These virions are constructed from a mixture of viral and host proteins7, but we only know the quantities within them of a small number of highly-abundant viral proteins with distinctive biophysical properties or electrophoretic mobilities1-3,6,8-22.

Here, in order to characterise influenza virions in greater detail, we analyse their protein composition using a sensitive liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) approach, and then determine protein abundance by using the intensities of fragment ion spectra to perform label-free absolute quantitation. This allow us to establish a complete and quantified model for the protein composition of influenza virions. We show that the core architecture of spherical influenza virions is maintained across diverse combinations of viruses and hosts, but that it is elaborated with additional architectural features which depend on the host species. Host proteins, including those whose incorporation is species-dependent, make a substantial contribution to influenza virion architecture. Furthermore, the host-encoded proteins in influenza virions are strikingly similar to the protein profile of virion-sized microvesicles shed by uninfected cells, suggesting that the virus subverts cellular pathways normally used for microvesicle formation in order to produce enveloped virions.

Results

Label-free protein ratios determined from mass spectra

Mass spectrometry provides a large amount of information which can be used to estimate protein abundance. This can be conveniently performed by Spectral Index Normalized Quantitation (SINQ)23, a method for label-free absolute protein quantitation of data from LC-MS/MS analysis which is available as part of the Central Proteomics Facilities Pipeline software24, and which is based on the intensities of fragment ion spectra. The method considers the summed intensity of fragment ions assigned to each protein, weighted to correct for ambiguous protein assignments, sample complexity and the tendency of longer proteins to produce more peptides23. By analysing mixtures of proteins of known concentration we determined that SINQ could simultaneously quantify the abundance of a large number of specific proteins in a mixture. As expected, the accuracy with which protein ratios were determined depended on both the proteins’ abundance and the particular proteins being compared. However, we found that SINQ could determine most equimolar and 10-fold protein ratios to within four-fold of the correct value and that even over a 1000-fold difference in abundance it could correctly place ratios within 8-fold (Methods and Supplementary Fig. 1a-c).

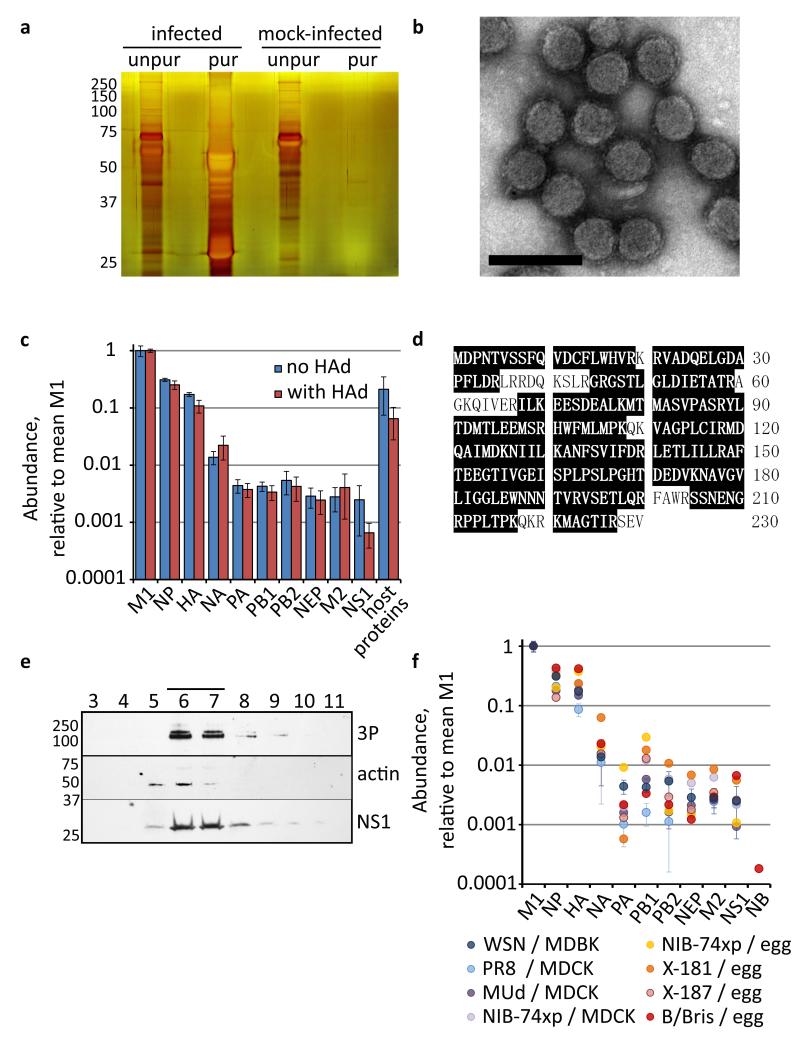

The composition of an influenza virion

We used SINQ to determine the ratio of viral proteins in virions produced by bovine epithelial (MDBK) cells infected with influenza A/WSN/33 virus (WSN). After two days of infection the cells’ growth medium was harvested and subjected to low-speed centrifugation to remove cellular debris. Virions were then purified from the supernatant by ultracentrifugation through a sucrose gradient (Fig. 1a,b). By comparing data collected in three separate biological repeats (Table 1), we obtained reproducible estimates of viral protein abundance that varied over three orders of magnitude (Fig. 1c, Table 2). As in a previous study25, we detected all nine of the recognised viral structural proteins, as well as the NS1 protein. We did not detect peptides unambiguously identifying the truncated proteins PB1-N40, PA-N155 or PA-N182, and we searched for, but did not detect, PB1-F2, PA-X, M3, M4, M42, NS3 and NSP/NEG8, which have been proposed or positively identified as viral gene products but which have not been shown to be structural proteins25. In addition we identified over three hundred host-encoded proteins. No more than eight copies of the viral polymerase are thought to be incorporated per virion2,26,27, and we reasoned that proteins found at less than a tenth of this abundance must be present at less than one copy per virion. We could reproducibly identify proteins even at abundances hundreds of times below this threshold, indicating that we had assessed the complete consistent protein composition of an influenza virion without the need for further fractionation of the sample.

Figure 1. The abundance of viral proteins in influenza virions.

Bovine epithelial (MDBK) cells were infected with influenza A/WSN/33 virus (WSN) or mock-infected, and media harvested after 48 h. (a) Samples of media were separated by SDS-PAGE either before (diluted 1/1000) or after purification by gradient ultracentrifugation, and silver-stained. (b) Purified influenza A/WSN/33 virions, negatively-stained and visualised by EM; the scale bar is 200 nm. (c) Abundance of viral proteins in purified virions, calculated by SINQ and normalized by the mean level of M1. The total abundance of all host proteins detected is also shown. The mean and s.d. is shown of 3 separate experiments, performed either with or without a haemadsorption / elution step (HAd). (d) The NS1 sequence of WSN shaded to show peptides identified by LC-MS/MS (from 3 separate experiments, purified without HAd; 87 % coverage). (e) Virions were layered onto a 30 – 60 % sucrose gradient and subjected to ultracentrifugation. The gradient was then harvested in 15 fractions from the top; the fractions shown were analysed by 14% SDS-PAGE and Western blotting for the indicated proteins. The position of molecular weight markers is indicated in kDa; concentrated virions were visible as a band in the gradient between fractions 6 and 7 (line). (f) Abundance of viral proteins in virions of 6 different influenza A viruses and an influenza B virus, grown in a variety of hosts (bovine epithelial (MDBK) cells, canine epithelial (MDCK) cells, and embryonated chicken eggs; see Table 1 for details). For WSN the mean and s.d. of 3 separate experiments is shown and for PR8 and MUd the mean and range of 2 separate experiments.

Table 1. Viruses and hosts used in the study.

| Name | Virus | Reassortmenta | Host | Experimentsb | Replicatesc |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q Exactive | Orbitrap | |||||

|

| ||||||

| WSN | A/WSN/33 (H1N1) | MDBK cells | 3 (virus; no HAd), 3 (mock; no HAd) 3 (virus; with HAd) 3 (mock; with HAd) |

1 1 1 1 |

||

| PR8 | A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 (H1N1) | MDCK cells | 2 | 1 | ||

| MUd | A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 (H1N1) | M from A/Udorn/307/1972 (H3N2) |

MDCK cells | 2 | 1 | |

| NIB-74xp | NIB-74xp (PR8) | HA and NA from A/Christchurch/16/2010 (pdmH1N1) |

MDCK cells, chicken eggs | 1 (MDCKs), 1 (eggs) |

2 | |

| X-181 | NYMC X-181 (PR8) | HA, NA and PB1 from A/California/7/2009 (pdmH1N1) |

Chicken eggs | 1 | 2 | |

| X-187 | NYMC X-187 (PR8) | HA and NA from A/Victoria/210/2009 (H3N2) |

Chicken eggs | 1 | 2 | |

| B/Bris | B/Brisbane/60/2008 | Chicken eggs | 1 | 2 | ||

Donor segments, named after major gene product;

number of purified samples analysed;

number of replicate analyses of each sample, performed on the instrument indicated.

Table 2. The abundance of viral proteins in influenza A/WSN/33 virions.

| Protein | Relative to M1a | Relative to Pol b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Mean | s.d. | Mean | s.d. | |

|

| ||||

| M1 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 1704 | 360 |

| NP | 0.31 | 0.02 | 530 | 32 |

| HA | 0.172 | 0.013 | 294 | 23 |

| NA | 0.014 | 0.004 | 23 | 6 |

| M2 | 0.0028 | 0.0013 | 4.7 | 2.2 |

| NEP | 0.0029 | 0.0011 | 4.9 | 1.9 |

| PA | 0.0044 | 0.0012 | 7.5 | 2.0 |

| PB1 | 0.0043 | 0.0008 | 7.3 | 1.4 |

| PB2 | 0.0054 | 0.0024 | 9.2 | 4.1 |

| NS1 | 0.0025 | 0.0019 | 4.2 | 3.2 |

Absolute quantification of proteins from virions produced by WSN-infected bovine epithelial (MDBK) cells, purified by gradient ultracentrifugation without HAd. Mean and SD of three experiments:

scaled so that the mean abundance of M1 is 1,

scaled so that the mean abundance of the three polymerase subunits (PA, PB1 and PB2) is 8.

Our estimates of protein abundance were in agreement with the limited data already available on influenza virion composition (Supplementary Data 1). For example, we correctly determined an equimolar ratio for the subunits of the trimeric viral polymerase (PA, PB1 and PB2) despite their low abundance in the virion. Accurate comparisons could also be made between proteins of high and low abundance. The ratio of the polymerase to the highly-abundant nucleoprotein (NP; mean 66, s.d. 14), combined with estimates that each NP binds at least 24 nt of RNA28 and that the complete influenza genome is bound to eight polymerase trimers29, suggests a minimum genome size of 12.7 kb (s.d. 2.6 kb); the actual size is 13.6 kb. Some caution is needed for glycoproteins and transmembrane proteins whose features suppress the efficiency of detection by mass spectrometry. However even for these problematic proteins we were able to make consistent measurements that were comparable to those in the literature (Supplementary Data 1), allowing us for the first time to assess the abundance of all viral structural proteins simultaneously.

We were surprised by our consistent identification of NS1 in purified virions (Fig. 1c), as this protein had previously been thought to be non-structural. The protein was unambiguously identified by LC-MS/MS (Fig. 1d), and could also be detected in purified virions using a panel of specific antibodies (Supplementary Fig. 2a-c). When we examined the behaviour of NS1-bearing material during ultracentrifugation we found that NS1 migrated through density gradients at the position of a visible band of virions. It co-migrated with the viral polymerase and with actin, one of the more abundant host proteins in virions (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 2d). In samples of lysed virions NS1 did not migrate with NP on glycerol gradients, suggesting it does not form stable associations with viral ribonucleoprotein complexes (Supplementary Fig. 2e), but in samples of unlysed virions it was at least as resistant to protease treatment as NP, suggesting that it is an internal component of the virion (Supplementary Fig. 2f-h). We therefore concluded that NS1 is found at low levels within influenza virions.

A conserved architecture of viral proteins

We next compared viral proteins in virions shed by a selection of different hosts (mammalian epithelial tissue cultures and embryonated chicken eggs) infected with a selection of influenza viruses (Table 1). In clinical isolates a mixture of spherical and filamentous influenza virions is typically found, but most influenza viruses adapted to growth in tissue culture or in eggs form only spherical virions30. Filamentous influenza virions are highly diverse in their morphology and presumably have highly variable protein compositions as a result4. As we were analysing the bulk properties of samples of virions, we concentrated on spherical virions which have a more uniform morphology.

Viral proteins were incorporated at consistent levels for a selection of influenza A virions, regardless of the strain or host (Fig. 1f). The same ratio was observed for orthologous proteins in virions of an influenza B virus (B/Bris), despite the differences in protein sequence and regulation of gene expression that have emerged since this genus diverged from the influenza A viruses31. All virions clearly contained NS1; B/Bris also incorporates low levels of the NB protein, for which there is no influenza A virus ortholog (although as this is a glycosylated transmembrane protein we expect its abundance to be somewhat higher than estimated by SINQ32,33). Despite the lack of a fixed virion structure, we show that spherical influenza virions incorporate their viral proteins in a consistent ratio, an optimal architecture that has been maintained throughout the separate evolution of influenza A and B viruses.

Influenza virions contain abundant host proteins

Host proteins have been identified in influenza virions, but their abundance has not previously been assessed. While most of the host proteins we identified were present at very low abundance and could not have been consistently incorporated into virions (Supplementary Data 2), several hundred proteins were abundant enough to be virion components (Supplementary Data 3–5), and together they made a substantial contribution to virion structure (Fig. 1c). More than a dozen of these proteins were more abundant than the viral polymerase, including some proteins whose abundance appeared roughly equal to that of the viral NA protein. These include proteins such as tetraspanins which due to their substantial transmembrane domains are likely to be present in even higher abundance than our measurements suggest. Thus, purified virions contain a large number of host proteins at low abundance and a smaller set of host proteins that are major components of the virion.

Virion architecture is shaped by the host

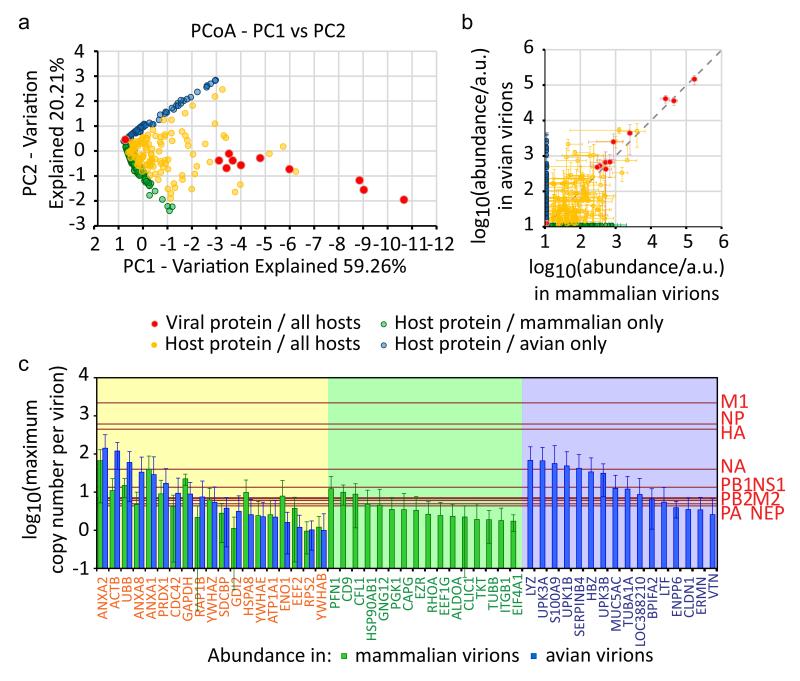

In order to compare proteins between different hosts we matched them to their human orthologs (Supplementary Data 6). Differences in protein abundance were observed between all samples analysed, presumably due to a combination of genuine variation between virions and variations in the efficiency of detection (Supplementary Data 2). However, principal coordinates analysis captured the majority of the differences in log(abundance) in two axes (Fig. 2a). Visual inspection of this plot showed that proteins formed three clusters: proteins present only in virions from mammalian hosts (either bovine or canine epithelial tissue cultures), proteins present only in virions from avian hosts (embryonated chicken eggs), and proteins present in virions from any host. Each category contained proteins abundant enough to be consistent components of virions (Fig. 2b). Thus, influenza virions have a consistent core architecture which includes proteins encoded by the host as well as by the virus, as well as a variable complement of proteins whose incorporation depends on whether the virion was constructed in a mammalian or avian host (Fig. 2c).

Figure 2. The abundance of host proteins in influenza virions.

Protein abundance in purified virions was determined by SINQ. A threshold was set at one tenth the abundance of the least abundant polymerase subunit, and any protein of lower abundance was assigned this value. Proteins were matched to their human orthologs to allow comparisons between virions from different host species. (a) Principal co-ordinates analysis of log10(protein abundance/a.u.) for 548 protein orthologs (goodness of fit = 0.795). (b) Log10(abundance/a.u.) of proteins in virions from mammalian cells and in virions from avian cells; mean and s.d. of four combinations of viruses and mammalian hosts, and four combinations of viruses and avian hosts (Table 1). (c) The core and host-dependent features of influenza virions. The maximum copy number of proteins in virions is shown, calculated by assuming that an average virion incorporates no more than eight viral polymerases. Viral proteins are shown as red lines, and host proteins with a mean copy number greater than one are shown as bars. Host proteins are only shown if detected in all four combinations of virus and host with both mammalian hosts (green bars) and avian hosts (blue bars); the mean and s.d. is indicated. The core architecture of a spherical influenza virion consists of the viral proteins (red lines) and those host proteins found in all hosts (yellow background). Additional host proteins are found only in virions from mammalian hosts (green background) or from avian hosts (blue background).

Consistent with previous studies7, all virions incorporated abundant ubiquitin, annexins, cytoskeletal proteins and glycolytic enzymes, as well as peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase A (also known as cyclophilin A), a restriction factor for influenza replication7,34. We also detected abundant membrane proteins, small GTPases and other regulators of signalling (including several 14-3-3 isoforms) as part of the core architecture. Many of the mammalian-and avian-specific proteins also fell into these categories, suggesting that the same functional niches in the virion are being filled (Supplementary Data 4 and 5). Notably, the tetraspanin CD9 is among the most abundant of the mammalian-specific proteins; in egg-grown virions its place appears to be taken by similar amounts of uroplakin-1B (UPK1B), a member of a separate tetraspanin family. Other proteins are unique to one host type, for example the ubiquitin-like protein ISG15 was only detected virions grown in canine epithelial (MDCK) cells. A full list of ‘core’ and host-dependent proteins is given in Supplementary Data 3–5.

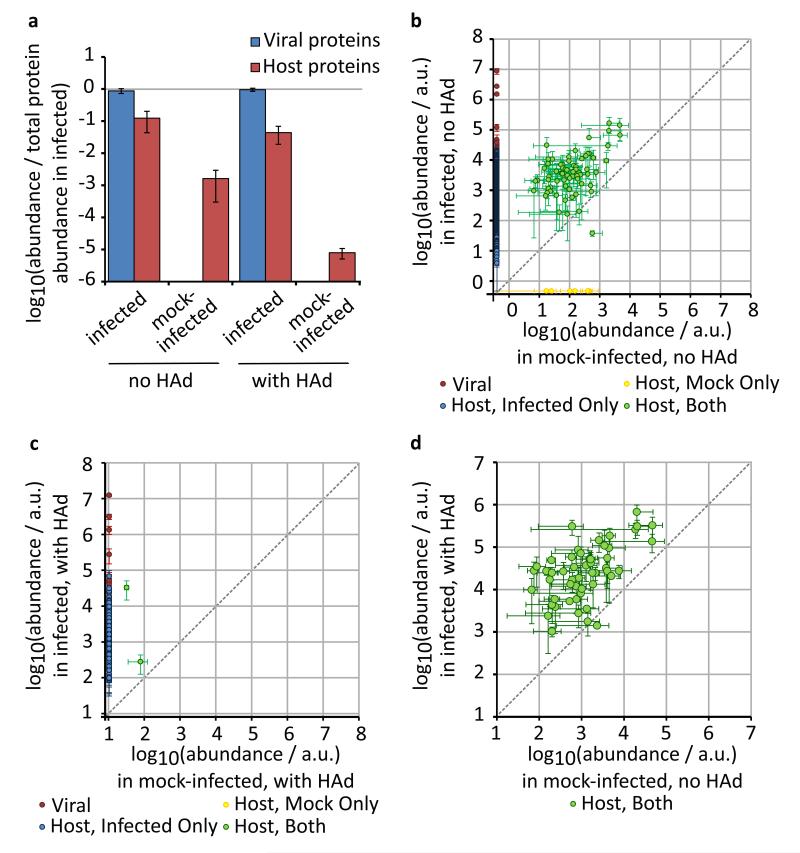

Uninfected cells shed material which resembles virions

We purified virions using standard techniques based on sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation. To examine the stringency of these methods, we purified virions from the media of WSN-infected bovine epithelial (MDBK) cells and performed parallel purifications on the media of mock-infected cells (Table 1). Using SDS-PAGE and silver staining we could detect abundant proteins in samples prepared from the media of infected cells but we could barely detect material purified from the media of mock-infected cells (Fig. 1a). Using LC-MS/MS we could detect proteins in both infected and mock-infected samples, though the diversity and abundance of proteins in the mock-infected samples were much less (Fig. 3a,b). The conditions used to purify influenza virions were designed to exclude large fragments of cellular debris, and are very similar to procedures used to purify small extracellular microvesicles such as exosomes7,35-38. We therefore concluded that uninfected cells shed low levels of microvesicles of a similar size to influenza virions.

Figure 3. Comparison of proteins shed by infected and uninfected cells.

To compare shedding from infected and mock-infected cells, gradient ultracentrifugation was used to purify virion-sized material from the growth media of bovine epithelial (MDBK) cells 48 h after either infection with WSN or mock-infection. Purifications were performed with or without a prior haemadsorption / elution step (HAd), and protein standards were added after purification to allow comparison of samples with different total protein concentrations. Purified proteins were quantified by SINQ. (a) Total abundance of purified viral and host proteins, relative to the mean total protein abundance in the infected samples (mean and s.d. of three separate experiments, not including protein standards). (b – d) The abundance of individual proteins shed by infected and mock-infected cells, and detected in at least two of three separate experiments (mean and s.d. if N=3, mean and range if N=2; not including protein standards). Proteins not detected in one condition (infected or mock-infected) were assigned the lowest abundance of any protein detected in that condition. Panels show the abundance of proteins (b) purified without HAd, (c) purified with HAd, and (d) common to the mock-infected sample without HAd and to the infected sample with HAd.

Abundant host proteins are stably associated with virions

To determine whether host proteins were present in virions or in co-purifying microvesicles, we increased the stringency of our purification method by introducing an initial step in which haemadsorption (HAd) to and elution from red blood cells selected for material with both receptor binding and cleaving activities (as provided by the viral haemagglutinin and neuraminidase, HA and NA). This step greatly increased the stringency of purification - other than protein standards and common contaminants only two proteins were consistently found in the mock-infected sample, and these at very low levels (Fig. 3a,c).

In the infected samples HAd also increased stringency and removed a portion of the host proteins, mainly those of low abundance (Fig. 1c). These included common cytoplasmic proteins that are plausible contaminants. For example, 57 of the 61 ribosomal proteins identified in the infected samples were removed by HAd (a full list of the proteins detected is given in Supplementary Data 2 and their correspondence with other experiments is given in Supplementary Data 3 and 4). HAd should not remove components of the virion, and consistent with this it did not affect the abundance of viral proteins (Fig. 1c; the mean abundance of NS1 was slightly reduced but not significantly so: p = 0.2, 2-tailed unpaired t-test). The detection of abundant host proteins after more stringent purification demonstrates that these too are components of the virion (Figs. 1c, 3a,c).

Influenza virions and exosomes share architectural features

Almost all of the proteins found in the uninfected material are known markers of exosomes39,40, suggesting that this material did indeed consist of microvesicles. Although these microvesicles could be removed by HAd (Fig. 3a,c), this did not remove exosomal markers from purified virions. Indeed, the proteins detected in microvesicles are present in the same ratio in stringently-purified virions shed by the same cell type (Fig. 3d), and the greater quantity of material purified in virions allowed the detection of many additional exosomal proteins that we could not detect in the low-abundance mock-infected samples. For all combinations of influenza virus and host, most of the host proteins identified in virions have also been identified in exosomes (Supplementary Data 3–5; the probability of this degree of enrichment occurring by chance, calculated by a hypergeometric test, is less than 0.001)39,40. Influenza virions therefore resemble exosomes both in their hydrodynamic properties and in their protein composition.

Discussion

Influenza viruses, like many other medically important viruses, produce virions with a variable structure which has made it challenging to determine their composition in detail. To address this we used mass spectrometry to gain detailed quantitative information about the protein composition of influenza virions, as well as that of the microvesicles shed by uninfected cells. The same approach could be used to characterise many other pleomorphic virions which, for similar reasons, are not amenable to high-resolution structural analysis. More generally, its ability to determine protein ratios in complex mixtures across a large dynamic range, without the need for labelling, could be used in the study of any protein-containing structure as long as it can be purified and concentrated.

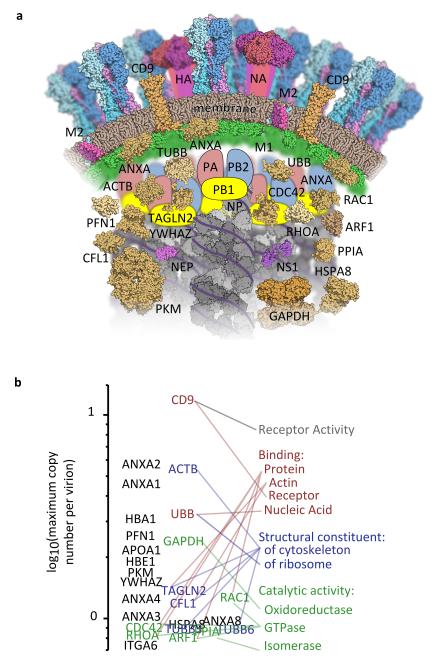

Mass spectrometry allowed us to analyse the protein composition of influenza virions with a sensitivity far exceeding that of other approaches1-3,6,8-22. Furthermore, recent increases in instrument sensitivity meant that we could detect around ten times the number of host proteins previously identified in influenza virions by mass spectrometry7. By measuring protein abundance we found that host proteins make a substantial contribution to the structure of influenza virions (Fig. 4). We could also detect proteins whose abundance was orders of magnitude less than the viral polymerase, indicating that we have obtained the first complete description of the protein composition of influenza virions.

Figure 4. The architecture of an influenza virion.

Proteins in virions produced by WSN-infected bovine epithelial (MDBK) cells, present at more than one tenth the abundance of the viral polymerase and found in material purified both with and without HAd in at least two separate experiments. (a) Schematic cross-section of an influenza virion, showing proteins whose localisation in the virion is known or can be inferred from other studies. Host proteins and membrane are brown and viral proteins are brightly coloured. (b) Host proteins, ranked by maximum copy number in virions (calculated as in Fig. 2) and linked to their Gene Ontology molecular function terms.

We were surprised to identify the viral NS1 protein as a consistent component of influenza virions. Previous reports that NS1 was non-structural are likely due to its low abundance, and possibly also to its position on polyacrylamide gels being obscured by CD9 and the highly abundant M1 protein, which have a similar electrophoretic mobility to the NS1 protein of some influenza strains17,41,42. NS1 was not detected in a previous LC-MS/MS study7 but comparison to our results suggests that previously NS1 was near the lower limit of instrument sensitivity. In the present study we were able to unambiguously detect NS1 even after stringent purification, and we concluded that it is a low-abundance component of influenza virions. As was previously the case for NS2 (now called NEP18,41), NS1 can no longer formally be considered non-structural. NS1 is a multifunctional protein43, and could potentially play a role in virion assembly or enhance infection when introduced into a new host cell. Alternatively, as NS1 is present at high levels in the cytoplasm of infected cells17,42 it is possible that it is incorporated into virions merely as a passive bystander. It is clear that NS1 is not non-structural, but considering what is currently known about the protein we note that its primary role is as a Nucleic-acid-binding Suppressor of Immunity (NSI).

More generally, we identified a consistent underlying architecture for spherical virions of influenza A viruses and an evolutionarily diverged influenza B virus. This evolutionarily conserved architecture includes the viral proteins and a set of host proteins, some of which are highly enriched in virions. Other features of the virion are not fixed, with the greatest variation due to the host. Mammalian tissue cultures and embryonated chicken eggs incorporated distinct sets of proteins into virions, some of them in substantial amounts. In some cases different proteins were recruited from related families (Fig. 2c); for example among the tetraspanin superfamily mammalian cells incorporate large amounts of CD9 and smaller amounts of CD81 into virions, whereas eggs incorporate UPK-1B (normally, but not exclusively, found on urothelial cells44).

These differences demonstrate that influenza virions derived from different hosts cannot be assumed to be the same. As virions produced by different hosts have typically been treated as equivalent when studying influenza infections, the phenotypic effects of these differences have not yet been explored in detail. The influence of the host on virion formation has been observed in influenza viruses with mutations interfering with correct genome packaging, which suppress virion budding in canine epithelial (MDCK) cells but do not have the same effect in chicken eggs45. Additionally, a tetraspanin whose incorporation we show here to be specific to mammalian hosts has recently been shown to be involved in virion entry and budding46. Host-dependent features of virions are of clinical interest as egg-grown virions are used in the preparation of influenza vaccines, and although allergies to egg proteins are not in themselves a contraindication to the administration of influenza vaccines they do increase the need for precautions47. Finally, host-specific differences suggest that virion composition may adapt when moving from avian to mammalian hosts, and hence that the structure of influenza virions may adapt during pandemic emergence.

Spherical influenza virions are a similar size to exosomes, membrane-bound structures which also transfer protein and RNA between cells35,36. By comparing separately-purified exosomes and virions we show here that they also have a strikingly similar protein profile – by many measures, an influenza virion is simply an exosome that has been enriched with additional components. Similarities have been noted between exosomes and a number of other enveloped viruses35,38, most notably HIV, for which the ‘Trojan exosome hypothesis’ was proposed to explain virion budding as a subversion of cellular pathways for exosome biogenesis48. The correspondence between exosomes and influenza virions is not absolute: influenza uses its M2 protein for budding rather than the ESCRT machinery used by many, though not all, microvesicles35,38,49,50, and while exosomes bud into multivesicular bodies influenza virions bud from the apical plasma membrane35. On the other hand, influenza is capable of redirecting membrane traffic, for example by translocating markers of autophagosomes to the plasma membrane51, and segments of the viral genome accumulate on unidentified structures adjacent to the plasma membrane prior to virion assembly52. The exosome-like features of influenza virions therefore cast light on the viral assembly process, suggesting that the virus commandeers elements of cellular pathways in order to construct the virions it needs to infect new hosts.

Methods

Cells, antisera and viruses

Mammalian epithelial tissue cultures were maintained in a humidified indicator at 37 °C and 5 % CO2. Bovine epithelial (MDBK) cells were obtained from the European Collection of Cell Cultures and grown in MEM (Sigma) supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine and 10 % fetal calf serum (FCS); canine epithelial (MDCK) cells were obtained from ATCC and grown in DMEM (Sigma) supplemented with 10 % FCS.

Western blotting was performed using rabbit anti-NS1 at 1/1000 (a kind gift of Juan Ortín, Centro Nacional de Biotecnología53), rabbit anti-actin at 1/200 (A2066; Sigma) and an antibody against the viral polymerase produced by immunising rabbits with an influenza A/NT/60/68 virus polymerase, purified as previously described and used at 1/50054. Additional Western blotting in Supplementary Fig. 2 used a sheep anti-NS1 at 1/500 (a kind gift of Richard Randall, University of St Andrews55), a second rabbit anti-NS1 at 1/500 (a kind gift of Adolfo García-Sastre, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai) and a rabbit anti-NP at 1/3000 (a kind gift of Paul Digard, University of Edinburgh56). Uncropped images of Western blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. 3.

A list of the viruses used is given in Table 1. WSN was grown in bovine epithelial (MDBK) cells in MEM supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine and 0.5 % FCS. PR8 and MUd (a kind gift of Paul Digard, University of Edinburgh) were grown in canine epithelial (MDCK) cells in DMEM supplemented with 0.14 % BSA and 1 μg/ml bovine pancreatic trypsin (Sigma). Candidate Vaccine Viruses (CVVs) were a kind gift of Othmar Engelhardt (National Institute of Biological Standards and Controls, UK). NIB-74xp, X-181, X-187 and B/Bris were grown in embryonated chicken eggs; in addition, NIB-74xp was grown in canine epithelial (MDCK) cells in MEM supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 0.14 % bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma) and 0.75 μg/ml bovine pancreatic trypsin (Sigma). Infections were carried out at a low multiplicity and virions harvested around 48 h p.i.; for tissue culture studies between 3 and 8 near-confluent T175 flasks of cells were infected for each experiment.

WSN and PR8 have undergone extensive laboratory passage and only produce spherical virions (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1d). We assumed that the CVVs NIB-74xp, X-181, X-187 and B/Bris would also produce spherical virions as they had been adapted to egg culture30, as the influenza A CVVs are reassortants with PR8 and carry key determinants of spherical morphology on segment 757,58, and as a recent structural study of another egg-grown influenza B virus, B/Lee/40, showed this to be spherical59. We also considered influenza PR8 with segment 7 from the A/Udorn/307/1972 H3N2 strain (MUd). MUd is capable of producing filamentous virions, but electron microscopy showed that although our samples contained a small proportion of filamentous virions the great majority of purified virions were spherical (Supplementary Fig. 1e). Consistent with this, when we compared purified PR8 and MUd virions the ratios of protein abundance were similar for the majority of proteins (Supplementary Fig. 1f; when ratios of abundance were calculated for the 446 host proteins detected in both PR8 and MUd virions, normalized by the abundance of viral polymerase, the median value was 3.8). Our data therefore describe virions with a spherical morphology.

Purification of virions

Some of the samples analysed here have been described previously25 and new material was purified using the same procedures. Briefly, the media of infected cells was clarified (2000 g/30 min then 18 000 g/30 min, at 4 °C), and material in the supernatant was then concentrated through a cushion of 30 % sucrose in NTC (100 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 5 mM CaCl2; at 112 000 g/90 min/4 °C in an SW 28 rotor (Beckman Coulter)). The pellets were resuspended in NTC and sedimented through a 30–60 % sucrose gradient in NTC (209 000 g/150 min/4°C in an SW 41 Ti rotor (Beckman Coulter)) to produce a visible band of virions which was harvested with a needle (except where the entire gradient was harvested in fractions from the top). Mock-infected samples were purified in parallel with infected samples, and an equivalent region of the gradient was harvested. Purified material was pelleted through NTC (154 000 g/60 min/4 °C in an SW 41 Ti rotor) and resuspended in a small volume of NTC. For purification using OptiPrep™ (Sigma) essentially the same procedure was used, but with a cushion of 10 % OptiPrep™ and a gradient of 10–40 % OptiPrep™. Material was harvested from infected eggs using a similar method which emulates that used to purify starting material for vaccine production25, though without the additional processing steps that vaccine formulations require. Briefly, allantoic fluid was harvested, filtered and mixed with sodium azide. Virions were concentrated by ultracentrifugation, resuspended and sedimented on a 10–40 % sucrose gradient to produce a visible band of virions which was harvested and pelleted by ultracentrifugation. For more stringent purification by HAd, cell media were clarified by low-speed centrifugation at 4 °C and then mixed with adult chicken blood (TCS Biosciences) at a final packed cell volume of approximately 0.2 %. The suspensions were kept at 4 °C for 30 min, inverting regularly, after which the blood was pelleted (1370 g/5 min/4 °C) and washed twice in 10 ml chilled phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The cell pellet was then resuspended in 37 °C PBS and incubated at 37 °C for 15 min, inverting regularly. Finally, the cells were pelleted (1370 g/5 min/10 °C) and the supernatant layered onto a 30 % sucrose cushion, after which purification proceeded as above.

Digests of virions were performed in NTC supplemented, when bovine pancreatic trypsin was used, with 5 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM TCEP. To analyse viral contents, virions were purified using essentially the same procedures as above, though with solutions buffered in NTE (100 mM NaCl, 10 mM TrisHCl pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA) rather than NTC. Purified virions were lysed at room temperature for 30 min in 100 mM TrisHCl pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 3% Triton X-100, 5% glycerol, 10 mg/ml lysolecithin and 1.5 mM DTT, and then layered onto a step gradient of 33, 40, 50 and 70 % glycerol in 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM TrisHCl pH7.5. The gradient was centrifuged at 245 000 g/240 min/4 °C in an SW55 Ti rotor (Beckman Coulter) and then harvested from the bottom of the tube.

Purified virions were analysed by SDS-PAGE and silver-staining or Western blotting, using standard techniques. In some cases virions were also visualised by transmission electron microscopy at the Bioimaging Facility of the Sir William Dunn School of Pathology. Virions were fixed in NTC with 2.5 % glutaraldehyde and 2 % paraformaldehyde, or 0.05 % glutaraldehyde and 4 % paraformaldehyde, adsorbed onto glow discharged carbon pioloform or carbon formvar grids, negatively stained with 2 % aqueous uranyl acetate and imaged in a Tecnai 12 transmission electron microscope (FEI, Eindhoven) operated at 120 kV.

Mass Spectrometry

Purified virions were analysed by mass spectrometry as described previously25. Briefly, samples were boiled in Laemmli buffer, purified by running a short distance into polyacrylamide, cut out, reduced, alkylated and digested with trypsin. Peptides were extracted, desalted on a C18 tip and then dissolved in 0.1% formic acid. LC-MS/MS was performed using an Ultimate 3000 RSLCnano HPLC system (Dionex, Camberley, UK) run in direct injection mode and typically coupled to a Q Exactive mass spectrometer (Thermo Electron, Hemel Hempstead, UK) in “Top 10” data-dependent acquisition mode; an LTQ XL Orbitrap (Thermo Electron, Hemel Hempstead, UK) in “Top 5” mode was also used for some samples (Table 1). Charge state +1 ions were rejected from selection and fragmentation and dynamic exclusion with 40 s was enabled; fragmentation was by HCD (Q Exactive) or CID (Orbitrap).

Mass spectra were analysed as previously described25 using the Central Proteomic Facilities Pipeline (CPFP), which uses iProphet to combine searches made with Mascot, OMSSA and X!TANDEM; peptide identifications are validated within CPFP using PeptideProphet. Protein identifications were inferred using ProteinProphet and protein identifications were filtered to a 1% false discovery rate by counting target and decoy sequences24. Peptide spectral matches were made to custom databases that concatenated the predicted proteome of the virus with that of the host as well as to the proteins of the Universal Protein Standards 2 (UPS2) protein dynamic range standard set (Sigma), common contaminants and decoy sequences. The contaminants list was from www.maxquant.org and the host proteomes were the UniProt Reference Proteomes for Bos taurus, Canis familiaris and Gallus gallus; all were downloaded on 12/12/2013. When Bos taurus was the host species, bovine proteins were manually removed from the contaminants list. Tryptic peptides with up to two missed cleavages were searched for using a precursor mass tolerance of 20 ppm and a fragment ion tolerance of 0.1 Da (0.5 Da for the LTQ XL Orbitrap), with carbamidomethylation of cysteine as a fixed modification and oxidation of methionine and deamidation of asparagine and glutamine as variable modifications; proteins were identified with a 1% false discovery rate. NSAF and SINQ were performed in CPFP, and iBAQ in MaxQuant, as previously described23; for SINQ at least two peptide sequences were required for quantitation. Before comparing datasets, decoy sequences and common contaminants (keratins, trypsin, serum albumin, serum albumin precursor, filaggrins, hornerin, PRSS1 Trypsin-1 precursor and dermokine) were manually removed. Human orthologs of proteins were searched for using the Panther classification system (www.pantherdb.org60,61) and by searching for sequence identity using UniProt Knowledgebase and BLAST (www.uniprot.org62); a list of assigned orthologs is given in Supplementary Data 6. Gene Ontology terms were assigned by the Panther Classification system60,61.

Testing Ratio Determination by SINQ

SINQ has previously been tested using LC-MS/MS data obtained with instruments including an LTQ XL Orbitrap23. We expected that a QExactive mass spectrometer would provide more accurate quantitation due its increased sensitivity and scan speed; to test the ability of SINQ to determine protein ratios when using this instrument we analysed UPS2 dynamic protein standards (Sigma), digested with trypsin (Supplementary Fig. 1a). UPS2 is a mixture of 48 proteins spanning 6 orders of magnitude of abundance; at the concentrations used we were able to detect 24 proteins over four orders of magnitude of abundance. Pairwise comparisons were made of protein abundances determined by SINQ (based on the intensity of fragment ion spectra), intensity-Based Absolute Quantitation (iBAQ; a computationally demanding method based on the intensity of peptide spectra, reported to provide relatively accurate estimates of abundance23,63), and Normalized Spectral Abundance Factor (NSAF; a less accurate but computationally less demanding method based on spectral counts64). All three methods were effective when comparing proteins in relatively high equimolar amounts, with SINQ determining most ratios within two-fold of the correct value, and the other methods determining most ratios within four-fold. Accuracy of all methods diminished for proteins of lower abundance or when comparing proteins whose amounts differed by orders of magnitude, but SINQ and iBAQ were able to place most ratios with 8-fold of the correct value over a 1000-fold difference in abundance (Supplementary Fig. 1a). We decided to use SINQ for further studies.

To test the effectiveness of SINQ in complex mixtures we mixed digested protein standards with either a digest of purified virions or of a mock sample purified from the media of uninfected cells (Supplementary Fig. 1b). The additional material was purified using HAd, resulting in a complex mixture of proteins in the virion-containing sample and very few detectable proteins in the mock sample (Fig. 3c). The most abundant protein standards were introduced at levels comparable to the viral polymerase subunits, which are low-abundance components of the virion. 10 standards were detected in the high-complexity (virion-containing) sample and 17 in the low-complexity (mock) sample, over three orders of magnitude of abundance. In both the high-complexity (infected) and low-complexity (uninfected) samples most equimolar and 10-fold ratios were determined within four-fold of the correct value.

Finally, to compare SINQ to an existing method of protein quantification we measured the relative abundance of the two most highly-expressed proteins in purified virions, NP and M1, by SINQ and by densitometry of protein bands separated by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue (Supplementary Fig. 1c). The NP/M1 ratios determined by the two methods are within 15% of each other. We also compared ratios of viral proteins determined by SINQ to previously published estimates made using a variety of methods1,6,8-22. In general our estimates were consistent with previously published values (Supplementary Data 1). The largest discrepancies between SINQ and other methods could be seen when comparing proteins of high and low abundance, which we attribute to the limited dynamic range of the gel electrophoresis and autoradiography methods used in these studies compared to LCMS/MS. Consistent with this, when the ratio of polymerase to NP was used to predict viral genome size (see Results for details) SINQ gave a much more accurate estimate than previous methods. We would expect glycosylation and transmembrane domains to reduce the efficiency of protein detection by LC-MS/MS. Consistent with this, SINQ appears to underestimate glycoprotein numbers by around 4-fold compared to other methods (Supplementary Data 1). There is less data available on the abundance of the M2 ion channel, but estimates of M2 levels by SINQ were around 9-fold less than in a previous study. Allowing for these caveats we determined that SINQ was, within reasonable limits, an effective method for simultaneously quantifying a large number of specific proteins in purified virions across a wide range of abundance.

Estimates of abundance by SINQ are affected by the overall protein concentration of the sample. To control for this when comparing infected and uninfected samples, equal amounts of digested UPS2 dynamic protein standards were mixed with the digested samples immediately prior to LC-MS/MS. This was done for all HAd samples and for a replicate analysis of one of the non-HAd WSN samples. The protein standards included ubiquitin and peroxiredoxin 1, both of which were already present in virions and could not be used for calibration. The remaining protein standards were used to normalize total protein levels and were then excluded from further analysis.

Data analysis

Principal co-ordinates analysis was performed using the cmdscale function in R65. A list of proteins identified in exosomes was downloaded from www.exocarta.org on 12/3/201439,40. A hypergeometric test was used to calculate the probability that our samples were enriched with these exosomal markers by chance: after removing redundancies, the number of occurrences of markers in the data in Supplementary Data 3 – 5 (705/907 proteins) was compared to the total number of markers (3442) and the number of proteins annotated by EBI on 12/06/2014 in the genomes of humans, cows and chickens (20649, 19634 and 15621, respectively). Protein structures were visualised using QuteMol66 and Python Molecular Viewer67 and composited using Inkscape (www.inkscape.org). Membrane co-ordinates were from Tieleman et al.(1996)68, the RNP structure was adapted from Hutchinson et al. (2013)69 and the structure of NEP was modelled using Quark70; other protein co-ordinates used were from the Protein Data Bank, with accession codes 1RU7 (HA), 3BEQ (NA), 3LBW (M2), 1EA3 (M1), 2GX9 and 2ZKO (NS1), 1J6Z (ACTB), 1UBI (UBB), 4HNA (TUBB), 2BTF (PFN1), 1Q8G (CFL1), 4HKC (YWHAZ), 1ZJH (PKM), 1WYM (TAGLN2), 3TH5 (RAC1), 4HMY (ARF1), 3T06 (RHOA), 2KB0 (CDC42), 3KOM (PPIA), 4H5N (HSPA8) and 3GPD (GAPDH). 1AIN (ANXA1) and 1W7B (ANXA2) were used to represent all annexins, and the modelled structure of CD81 (2AVZ) was used to represent CD9.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank David Brown, George Brownlee, Daniel Lunn and Omer Dushek for helpful discussions, Narin Hengrung for providing reagents and Errin Johnson for technical assistance. The work was supported by the MRC (programme grant MR/K000241/1 to EF).

Footnotes

Competing Financial Interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Accession codes: Raw files for all mass spectra used in this analysis have been deposited at the Mass spectrometry Interactive Virtual Environment (MassIVE; Center for Computational Mass Spectrometry at University of California, San Diego) and can be accessed at http://massive.ucsd.edu/ProteoSAFe/datasets.jsp using the MassIVE ID MSV000078740.

A full description of the influenza virion purification protocol can be found in the accompanying article Purification of influenza virions by haemadsorption and ultracentrifugation at Protocol Exchange (http://www.nature.com/protocolexchange doi: 10.1038/protex.2014.027).

References

- 1.Harris A, et al. Influenza virus pleiomorphy characterized by cryoelectron tomography. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:19123–19127. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607614103. doi:10.1073/pnas.0607614103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noda T, et al. Architecture of ribonucleoprotein complexes in influenza A virus particles. Nature. 2006;439:490–492. doi: 10.1038/nature04378. doi:10.1038/nature04378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wasilewski S, Calder LJ, Grant T, Rosenthal PB. Distribution of surface glycoproteins on influenza A virus determined by electron cryotomography. Vaccine. 2012;30:7368–7373. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.09.082. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.09.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vijayakrishnan S, et al. Cryotomography of budding influenza A virus reveals filaments with diverse morphologies that mostly do not bear a genome at their distal end. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003413. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003413. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nermut MV. Further investigation on the fine structure of influenza virus. J Gen Virol. 1972;17:317–331. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-17-3-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Booy FP, Ruigrok RW, van Bruggen EF. Electron microscopy of influenza virus. A comparison of negatively stained and ice-embedded particles. J Mol Biol. 1985;184:667–676. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90312-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaw ML, Stone KL, Colangelo CM, Gulcicek EE, Palese P. Cellular proteins in influenza virus particles. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000085. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000085. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Compans RW, Klenk HD, Caliguiri LA, Choppin PW. Influenza virus proteins. I. Analysis of polypeptides of the virion and identification of spike glycoproteins. Virology. 1970;42:880–889. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(70)90337-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skehel JJ, Schild GC. The polypeptide composition of influenza A viruses. Virology. 1971;44:396–408. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(71)90270-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haslam EA, Hampson AW, Radiskevics I, White DO. The polypeptides of influenza virus. 3. Identification of the hemagglutinin, neuraminidase and nucleocapsid proteins. Virology. 1970;42:566–575. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(70)90303-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujiyoshi Y, Kume NP, Sakata K, Sato SB. Fine structure of influenza A virus observed by electron cryo-microscopy. EMBO J. 1994;13:318–326. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06264.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruigrok RW, Calder LJ, Wharton SA. Electron microscopy of the influenza virus submembranal structure. Virology. 1989;173:311–316. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90248-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schulze IT. The structure of influenza virus. I. The polypeptides of the virion. Virology. 1970;42:890–904. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(70)90338-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schulze IT. The structure of influenza virus. II. A model based on the morphology and composition of subviral particles. Virology. 1972;47:181–196. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(72)90251-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tiffany JM, Blough HA. Estimation of the number of surface projections on myxo- and paramyxoviruses. Virology. 1970;41:392–394. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(70)90096-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zebedee SL, Lamb RA. Influenza A virus M2 protein: monoclonal antibody restriction of virus growth and detection of M2 in virions. J Virol. 1988;62:2762–2772. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.8.2762-2772.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inglis SC, Carroll AR, Lamb RA, Mahy BW. Polypeptides specified by the influenza virus genome I. Evidence for eight distinct gene products specified by fowl plague virus. Virology. 1976;74:489–503. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(76)90355-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yasuda J, Nakada S, Kato A, Toyoda T, Ishihama A. Molecular assembly of influenza virus: association of the NS2 protein with virion matrix. Virology. 1993;196:249–255. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1473. doi:10.1006/viro.1993.1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruigrok RW, Andree PJ, Hooft van Huysduynen RA, Mellema JE. Characterization of three highly purified influenza virus strains by electron microscopy. J Gen Virol. 1984;65(Pt 4):799–802. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-65-4-799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cusack S, Ruigrok RW, Krygsman PC, Mellema JE. Structure and composition of influenza virus. A small-angle neutron scattering study. J Mol Biol. 1985;186:565–582. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90131-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oxford JS, Corcoran T, Hugentobler AL. Quantitative analysis of the protein composition of influenza A and B viruses using high resolution SDS polyacrylamide gels. J Biol Stand. 1981;9:483–491. doi: 10.1016/s0092-1157(81)80041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mellema JE, et al. Structural investigations of influenza B virus. J Mol Biol. 1981;151:329–336. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90521-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trudgian DC, et al. Comparative evaluation of label-free SINQ normalized spectral index quantitation in the central proteomics facilities pipeline. Proteomics. 2011;11:2790–2797. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201000800. doi:10.1002/pmic.201000800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trudgian DC, et al. CPFP: a central proteomics facilities pipeline. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:1131–1132. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq081. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btq081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hutchinson EC, et al. Mapping the phosphoproteome of influenza A and B viruses by mass spectrometry. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002993. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002993. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hutchinson EC, von Kirchbach JC, Gog JR, Digard P. Genome packaging in influenza A virus. J Gen Virol. 2010;91:313–328. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.017608-0. pii:vir.0.017608-0 ; doi:10.1099/vir.0.017608-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chou YY, et al. One influenza virus particle packages eight unique viral RNAs as shown by FISH analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:9101–9106. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206069109. doi:10.1073/pnas.1206069109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ortega J, et al. Ultrastructural and functional analyses of recombinant influenza virus ribonucleoproteins suggest dimerization of nucleoprotein during virus amplification. J Virol. 2000;74:156–163. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.1.156-163.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sugita Y, Sagara H, Noda T, Kawaoka Y. Configuration of viral ribonucleoprotein complexes within the influenza A virion. J Virol. 2013;87:12879–12884. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02096-13. doi:10.1128/JVI.02096-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seladi-Schulman J, Steel J, Lowen AC. Spherical influenza viruses have a fitness advantage in embryonated eggs, while filament-producing strains are selected in vivo. J Virol. 2013;87:13343–13353. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02004-13. doi:10.1128/JVI.02004-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Powell ML, Napthine S, Jackson RJ, Brierley I, Brown TD. Characterization of the termination-reinitiation strategy employed in the expression of influenza B virus BM2 protein. Rna. 2008;14:2394–2406. doi: 10.1261/rna.1231008. doi:10.1261/rna.1231008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Betakova T, Nermut MV, Hay AJ. The NB protein is an integral component of the membrane of influenza B virus. J Gen Virol. 1996;77(Pt 11):2689–2694. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-11-2689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brassard DL, Leser GP, Lamb RA. Influenza B virus NB glycoprotein is a component of the virion. Virology. 1996;220:350–360. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0323. doi:10.1006/viro.1996.0323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu X, et al. Cyclophilin A interacts with influenza A virus M1 protein and impairs the early stage of the viral replication. Cell Microbiol. 2009;11:730–741. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01286.x. doi:10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meckes DG, Jr., Raab-Traub N. Microvesicles and viral infection. J Virol. 2011;85:12844–12854. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05853-11. doi:10.1128/JVI.05853-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raposo G, Stoorvogel W. Extracellular vesicles: exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. The Journal of cell biology. 2013;200:373–383. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201211138. doi:10.1083/jcb.201211138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vlassov AV, Magdaleno S, Setterquist R, Conrad R. Exosomes: current knowledge of their composition, biological functions, and diagnostic and therapeutic potentials. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1820:940–948. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.03.017. doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wurdinger T, et al. Extracellular vesicles and their convergence with viral pathways. Advances in virology. 2012:767694. doi: 10.1155/2012/767694. doi:10.1155/2012/767694 (2012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mathivanan S, Fahner CJ, Reid GE, Simpson RJ. ExoCarta 2012: database of exosomal proteins, RNA and lipids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D1241–1244. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr828. doi:10.1093/nar/gkr828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simpson RJ, Kalra H, Mathivanan S. ExoCarta as a resource for exosomal research. Journal of extracellular vesicles. 2012;1 doi: 10.3402/jev.v1i0.18374. doi:10.3402/jev.v1i0.18374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Richardson JC, Akkina RK. NS2 protein of influenza virus is found in purified virus and phosphorylated in infected cells. Arch Virol. 1991;116:69–80. doi: 10.1007/BF01319232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lamb RA, Choppin PW. Synthesis of influenza virus proteins in infected cells: translation of viral polypeptides, including three P polypeptides, from RNA produced by primary transcription. Virology. 1976;74:504–519. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(76)90356-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hale BG, Randall RE, Ortin J, Jackson D. The multifunctional NS1 protein of influenza A viruses. J Gen Virol. 2008;89:2359–2376. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.2008/004606-0. doi:10.1099/vir.0.2008/004606-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sun T-T, Kreibich G, Pellicer A, Kong X-P, Wu X-R. In: Tetraspanins Proteins and Cell Regulation. Berditchevski F, Rubinstein E, editors. Springer; 2013. pp. 299–320. Ch. 12. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hutchinson EC, Curran MD, Read EK, Gog JR, Digard P. Mutational analysis of cis-acting RNA signals in segment 7 of influenza A virus. J Virol. 2008;82:11869–11879. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01634-08. pii:JVI.01634-08 ; doi:10.1128/JVI.01634-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.He J, et al. Dual function of CD81 in influenza virus uncoating and budding. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003701. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003701. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chung EH. Vaccine allergies. Clinical and experimental vaccine research. 2014;3:50–57. doi: 10.7774/cevr.2014.3.1.50. doi:10.7774/cevr.2014.3.1.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gould SJ, Booth AM, Hildreth JE. The Trojan exosome hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:10592–10597. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1831413100. doi:10.1073/pnas.1831413100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Babst M. MVB vesicle formation: ESCRT-dependent, ESCRT-independent and everything in between. Current opinion in cell biology. 2011;23:452–457. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.04.008. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rossman JS, Jing X, Leser GP, Lamb RA. Influenza virus M2 protein mediates ESCRT-independent membrane scission. Cell. 2010;142:902–913. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.08.029. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2010.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Beale R, et al. A LC3-Interacting Motif in the Influenza A Virus M2 Protein Is Required to Subvert Autophagy and Maintain Virion Stability. Cell host and microbe. 2014;15:239–247. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.01.006. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eisfeld AJ, Kawakami E, Watanabe T, Neumann G, Kawaoka Y. RAB11A is essential for transport of the influenza virus genome to the plasma membrane. J Virol. 2011;85:6117–6126. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00378-11. doi:10.1128/JVI.00378-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marion RM, Aragon T, Beloso A, Nieto A, Ortin J. The N-terminal half of the influenza virus NS1 protein is sufficient for nuclear retention of mRNA and enhancement of viral mRNA translation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4271–4277. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.21.4271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.York A, Hengrung N, Vreede FT, Huiskonen JT, Fodor E. Isolation and characterization of the positive-sense replicative intermediate of a negative-strand RNA virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E4238–4245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315068110. doi:10.1073/pnas.1315068110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hale BG, et al. Structural insights into phosphoinositide 3-kinase activation by the influenza A virus NS1 protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:1954–1959. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910715107. doi:10.1073/pnas.0910715107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Noton SL, et al. Identification of the domains of the influenza A virus M1 matrix protein required for NP binding, oligomerization and incorporation into virions. J Gen Virol. 2007;88:2280–2290. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82809-0. doi:10.1099/vir.0.82809-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Campbell PJ, et al. The M segment of the 2009 pandemic influenza virus confers increased NA activity, filamentous morphology and efficient contact transmissibility to A/Puerto Rico/8/1934-based reassortant viruses. J Virol. 2014;88:3802–3814. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03607-13. doi:10.1128/JVI.03607-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Elleman CJ, Barclay WS. The M1 matrix protein controls the filamentous phenotype of influenza A virus. Virology. 2004;321:144–153. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2003.12.009. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Katz G, et al. Morphology of influenza b/lee/40 determined by cryo-electron microscopy. PLoS One. 2014;9:e88288. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088288. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0088288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mi H, Muruganujan A, Thomas PD. PANTHER in 2013: modeling the evolution of gene function, and other gene attributes, in the context of phylogenetic trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D377–386. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1118. doi:10.1093/nar/gks1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mi H, Muruganujan A, Casagrande JT, Thomas PD. Large-scale gene function analysis with the PANTHER classification system. Nature protocols. 2013;8:1551–1566. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.092. doi:10.1038/nprot.2013.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.UniProt Consortium Activities at the Universal Protein Resource (UniProt) Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D191–198. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1140. doi:10.1093/nar/gkt1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schwanhausser B, et al. Global quantification of mammalian gene expression control. Nature. 2011;473:337–342. doi: 10.1038/nature10098. doi:10.1038/nature10098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zybailov B, et al. Statistical analysis of membrane proteome expression changes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Proteome Res. 2006;5:2339–2347. doi: 10.1021/pr060161n. doi:10.1021/pr060161n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.R Core Team . R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tarini M, Cignoni P, Montani C. Ambient occlusion and edge cueing to enhance real time molecular visualization. IEEE transactions on visualization and computer graphics. 2006;12:1237–1244. doi: 10.1109/TVCG.2006.115. doi:10.1109/TVCG.2006.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sanner MF. Python: a programming language for software integration and development. Journal of molecular graphics and modelling. 1999;17:57–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tieleman D, Berendsen J. Molecular dynamics simulations of fully hydrated DPPC with different macroscopic boundary conditions and parameters. J Chem Phys. 1996;105:4871–4880. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hutchinson EC, Fodor E. Transport of the influenza virus genome from nucleus to nucleus. Viruses. 2013;5:2424–2446. doi: 10.3390/v5102424. doi:10.3390/v5102424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Xu D, Zhang Y. Ab initio protein structure assembly using continuous structure fragments and optimized knowledge-based force field. Proteins. 2012;80:1715–1735. doi: 10.1002/prot.24065. doi:10.1002/prot.24065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.