Abstract

Unlike induced Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Foxp3+ iTreg) that have been shown to play an essential role in the development of protective immunity to the ubiquitous mold Aspergillus fumigatus, type-(1)-regulatory T cells (Tr1) cells have, thus far, not been implicated in this process. Here, we evaluated the role of Tr1 cells specific for an epitope derived from the cell wall glucanase Crf-1 of A. fumigatus (Crf-1/p41) in antifungal immunity. We identified Crf-1/p41-specific latent-associated peptide+ Tr1 cells in healthy humans and mice after vaccination with Crf-1/p41+zymosan. These cells produced high amounts of interleukin (IL)-10 and suppressed the expansion of antigen-specific T cells in vitro and in vivo. In mice, in vivo differentiation of Tr1 cells was dependent on the presence of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor, c-Maf and IL-27. Moreover, in comparison to Tr1 cells, Foxp3+ iTreg that recognize the same epitope were induced in an interferon gamma-type inflammatory environment and more potently suppressed innate immune cell activities. Overall, our data show that Tr1 cells are involved in the maintenance of antifungal immune homeostasis, and most likely play a distinct, yet complementary, role compared with Foxp3+ iTreg.

Regulatory T (Treg) cells have a key role for the maintenance of immune homeostasis, prevention of autoimmunity and protection against infections.1 Besides thymus-derived naturally occurring Foxp3+ nTreg, two major subsets of induced Treg cells have been identified: Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Foxp3+ iTreg) and Foxp3− type-(1)-regulatory T (Tr1) cells that differ in their mode of induction, phenotype and cytokine expression but share the overall feature to suppress immune responses.2 Foxp3+ iTreg differentiate in the presence of sub-immunogenic doses of antigen and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) in vitro and in vivo,3, 4 produce high amounts of interleukin (IL)-10 and TGF-β, and protect from chronic immunopathology in response to pathogens such as Leishmania major, hepatitis C virus or HIV.5, 6, 7 Tr1 cells, on the other hand, are induced through the coordinate activation of the transcription factor c-Maf by IL-27 and the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (Ahr).8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 Tr1 cells express latent-associated peptide (LAP) that binds TGF-β, produce high amounts of IL-10 relative to interferon gamma (IFN-γ) but no IL-410, 14, 15 and are presumed to protect from T-helper type-1(Th1)/Th17-mediated autoimmune disease in mice16 and prevent reactions to common allergens including house dust mites17, 18 and bee venom19 in humans.

Aspergillus fumigatus is an ubiquitous mold that can cause distinct modes of pathology: invasive aspergillosis (IA) and allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) in clinical situations such as neutropenia, immune suppression and chronic obstructive lung disease. In these cases, impaired lung immunity and subsequent fungal infections are accompanied with insufficient Th1 (IA)20, 21 and overwhelming Th2 (ABPA) responses, respectively.22, 23 Foxp3+ nTreg as well as Foxp3+ iTreg have been demonstrated to be essential for the induction of protective tolerance to the fungus in mice24 and humans25 by inhibition of overwhelming effector Th1/Th2 cell responses at late stages of experimental IA24, 26 and in ABPA patients.25

A clinical challenge is the induction of balanced antifungal effector T-cell responses together with Treg-cell responses to reduce the risk for Th1/Th2-mediated immunopathology and to promote the development of a durable protective immunity to A. fumigatus.23 This could be accomplished by an adoptive transfer of antifungal T cells. A. fumigatus-specific recombinant proteins derived from cell wall components are proposed to be the most promising immunogenic targets to induce protective antifungal immunity.27 We27 and others28, 29 have previously shown that epitopes derived from the cell wall glucanase Crf-1 induce protective antifungal Th1 responses, and more specifically, we identified an immunodominant epitope within the cell wall glucanase Crf-1 of A. fumigatus (Crf-1/p41, thereafter referred to p41) that induces protective Th1 responses in humans and Th1/Treg in mice.30 In the present study, we identified p41-specific Tr1 cells in the peripheral blood of healthy humans and in mice after vaccination with p41 and investigated their potential role in antifungal immunity.

Results

Identification of pre-existing p41+ Tr1 clones in healthy human donors

We have recently shown that the p41-peptide induces protective A. fumigatus-specific Th1 cell responses in humans and Th1/iTreg in a mouse model of aspergillosis.27, 30 This observation let us to investigate whether p41 has the potential to induce antifungal Tr1 cells, another Treg-cell subset that can be induced by inhaled antigens and regulates immune responses to these antigens. Due to the low frequency of p41+ memory T cells in the peripheral blood of healthy human donors (Supplementary Figure 1), we generated p41-specific T-cell clones from in vitro expanded p41+CD154+ T cells. To ensure analysis of different T-cell clones, we determined TcR-Vβ signatures of the clones (data not shown) and excluded identical clones from subsequent analyses. Tr1 cells are characterized by their high production of IL-10 with co-production of IFN-γ in the absence of IL-4.31 We therefore determined co-production of IL-10, IFN-γ and IL-4 by p41+ T-cell clones after p41-specific restimulation by cytometric bead array. With respect to this cytokine signature, p41+ T-cell clones were subdivided into a population with high and low IL-10-to-IFN-γ ratio (IL-10high and IL-10low) (Supplementary Table S1, Figure 1a). In contrast, none of the clones produced significant amounts of IL-4.

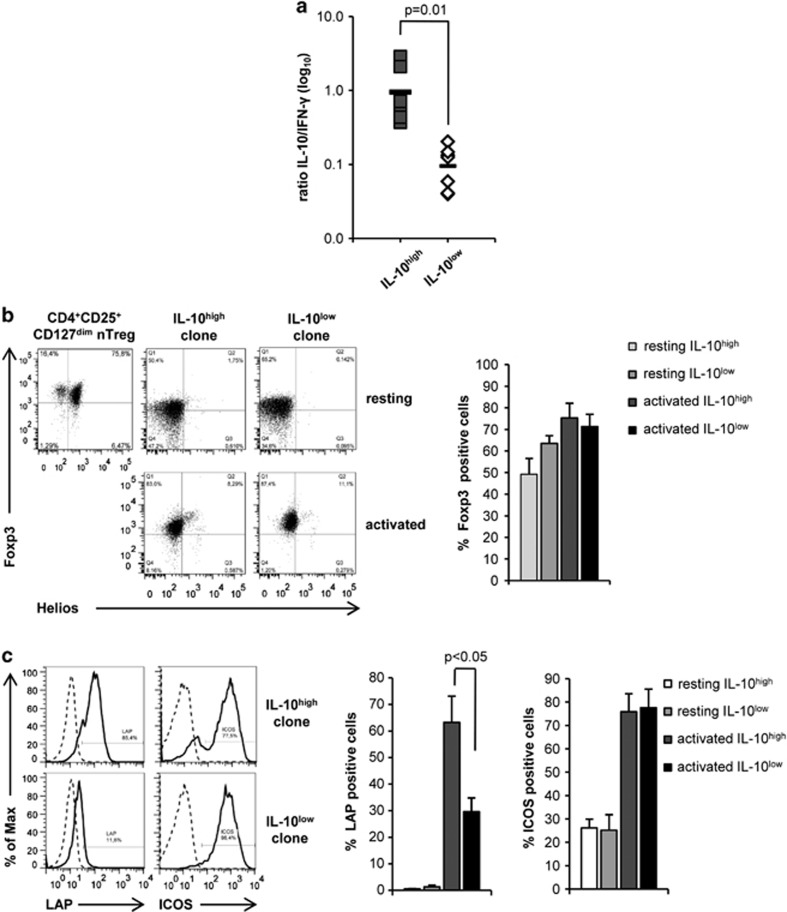

Figure 1.

Identification of human p41+CD4+ Tr1 cell clones in the peripheral blood of healthy human donors. (a) CD4+p41+ T-cell clones were restimulated with p41-pulsed DC for 48 h prior analysis of IL-10 and IFN-γ secretion from culture supernatants by Cytometric Bead Array. The diagram summarizes the ratio of IL-10-to-IFN-γ release±s.d. of p41+CD4+ T-cell clones (n=9 per group; three different donors). (b) Flow cytometric analysis of the Foxp3 and Helios expression in resting CD4+CD25+CD127dim nTreg and in one representative CD4+ T-cell clone with high (IL-10high) and low (IL-10low) IL-10-to-IFN-γ ratio (upper panel) and after stimulation with autologous p41-pulsed DC for 24 h (ratio 10:1, lower panel). The diagram summarizes the percentage of Foxp3+expression in resting and activated IL-10high and IL-10low p41+CD4+ T-cell clones±s.d. (n=7 per group; three different donors). (c) Histograms show expression of LAP and ICOS of one representative activated IL-10high and IL-10low p41+CD4+ T-cell clone (solid lines) compared with isotype controls (dashed lines) and diagram summarizes percentage of LAP and ICOS expression±s.d. on resting and activated p41+CD4+ T-cell clones, respectively (n=7 per group; three different donors).

Next, we compared the expression of LAP and inducible T-cell costimulator (ICOS) between IL-10high and IL-10low p41+ T-cell clones, two molecules that are expressed on Tr1 cells. LAP was specifically upregulated on p41+ T-cell clones with a high IL-10-to-IFN-γ ratio upon activation (Figure 1c). In contrast, ICOS expression was upregulated on all p41+ T-cell clones after restimulation. In addition, we detected transient upregulation of the Treg lineage-specific transcription factor Foxp3, but not Helios,32, 33 in activated p41+ T-cell clones, irrespective of their cytokine production profile (Figure 1b). However, transient Foxp3 in these clones was significantly lower compared with CD4+CD25+CD127dim nTreg. Thus, these data suggest that pre-existing IL-10-producing LAP+ p41+ Tr1 cells are present in the memory CD4+ T-cell pool of healthy humans.

Human p41+ Tr1 clones exert a suppressive activity against CD4+ T cells

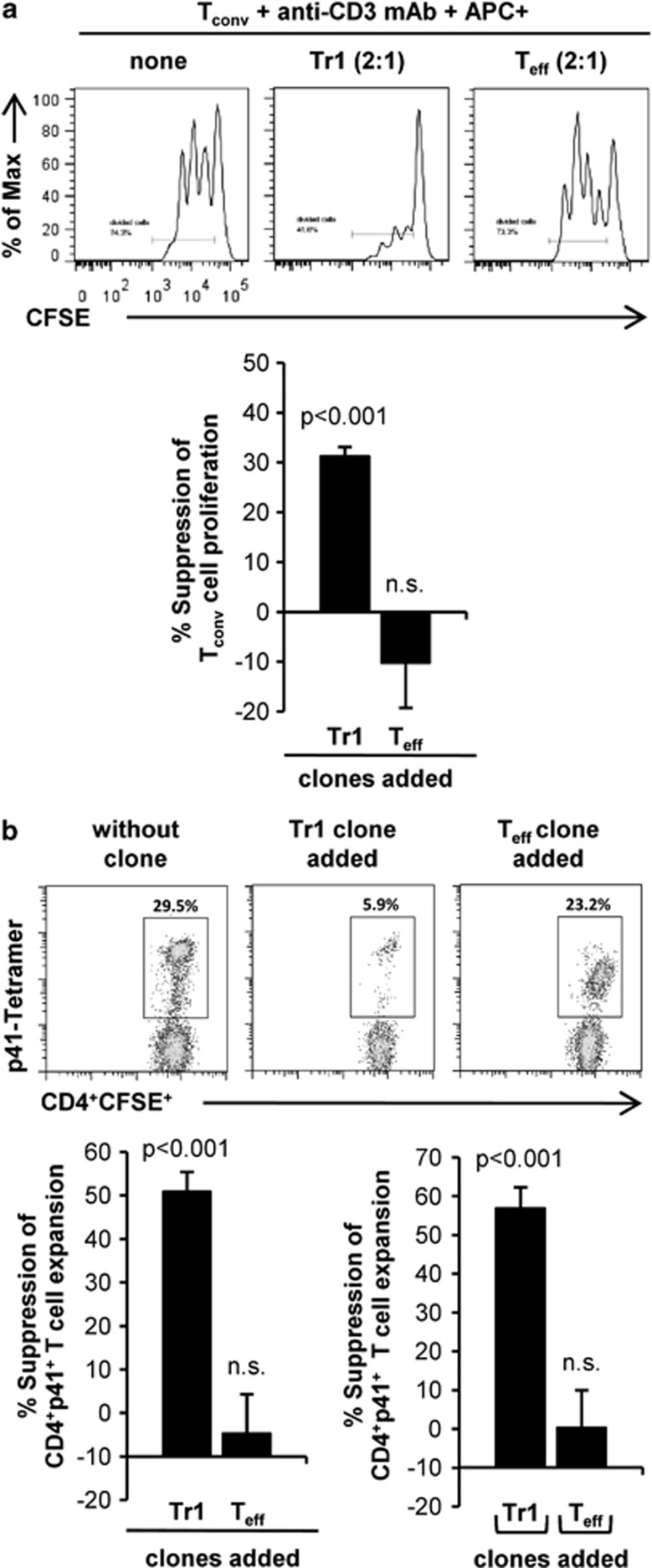

We next addressed the question whether p41+ Tr1 clones are able to suppress proliferation of autologous conventional CD4+ T cells (Tconv) in in vitro coculture assays. p41+ Tr1 clones significantly suppressed proliferation of CD4+CD25− Tconv (31±2% Figure 2a). This effect was specific for p41+ Tr1 clones as Tconv proliferation was not suppressed but rather increased in the presence of p41+ Teff clones, most likely referred to their high IL-2 production (data not shown). Of note, p41+ Tr1 clones also significantly suppressed in vitro expansion of p41-specific CD4+ T cells (51±5% suppression) in an antigen-specific manner (Figure 2b, upper panel and lower left). This suppression was contact-independent, as expansion of p41+ T cell was still reduced by 57±5% after separation from p41+ Tr1 clones by a semi-permeable membrane (Figure 2b lower right). Collectively, these data show that p41+ Tr1 clones are capable of suppressing the proliferation of Tconv and expansion of p41+ T cells in a contact-independent manner.

Figure 2.

Human p41+ Tr1 cell clones suppress expansion of CD4+ T cells. (a) T-cell clones were cocultured together with CFSE-labeled autologous CD4+CD25− T cells (Tconv) (1:2 ratio) and irradiated p41-pulsed CD2-depleted APC (1:2:4 (clone:Tconv:APC)) in round bottom plates, coated with 0.5 μg ml−1 anti-CD3 mAb. After three days, CFSE dilution was determined by flow cytometry. The histograms show CFSE dilution of Tconv in the absence and presence of one representative Teff and Tr1 clone. Diagrams summarize %±s.d. suppression of Tconv proliferation in the presence Tr1 and Teff clones (n=9 per group; three different donors) at a 1:2:4 ratio (clone:Tconv:APC). (b) CFSE-labeled PBMCs were cultured together with CellVue-Claret-labeled p41-specific T-cell clones at 2:1 ratio. After 24 h of culture and every second day, IL-2 were added to the culture. After seven days, the T cells were restimulated with p41-pulsed autologous DC at a ratio of 10:1 and cultured for additional six days in the presence of IL-7 and IL-15. Afterward, expansion of CFSE+CD4+p41+ T cells was analyzed by flow cytometry using a p41-specific PE-labeled tetramer. Dotplot analysis shows one experiment in the absence (left) and presence of a representative Tr1 clone (middle) and Teff clone (right). Diagrams summarize %±s.d. suppression of CD4+CFSE+p41+ T-cell expansion in contact-dependent presence of Tr1 and Teff clones (left) (n=6 per group; three different donors) as well as in contact-independent cocultures in transwell systems (right) (n=5 per group; three different donors).

Human p41+ Tr1 clones are not artificially induced during in vitro expansion

Tr1 cells can be induced under different polarizing conditions in vitro.34 To exclude that CD154+ T-cell pre-selection or addition of IL-7 and IL-15 during in vitro culture affect polarization of p41+ Tr1 cells, we generated p41+ T-cell clones from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) exclusively in the presence of IL-2. Consistent with our previous data, p41+ Tr1 clones generated in the absence of polarizing conditions exhibited a significantly increased IL-10-to-IFN-γ cytokine profile (Supplementary Figure 2A) without producing considerable amounts of IL-4 (data not shown), suppressed proliferation of Tconv by 36±1% (Supplementary Figure 2B) and expansion of p41+ T cells by 46±5% (Supplementary Figure 2C).

Further evidence that p41+ Tr1 clones are not artificially induced in vitro comes from analyses of cytomegalovirus (CMV)-specific CD4+ T-cell clones. The analysis of memory CMVpp65-specific CD4+ T-cell clones (donor 1) or, more restricted, CMVpp65283-297-specific CD4+ T-cell clones (donor 2)35 demonstrated that these clones could not be subdivided in terms of their IL-10-to-IFN-γ cytokine profile (Table 1). In fact, all clones produced high amounts of IL-4. Furthermore, these clones did not differentially upregulate LAP but exhibited a Foxp3 expression pattern comparable with p41+ T-cell clones (Supplementary Figure 3A, B). Consequently, CMV-specific T-cell clones failed to suppress in vitro proliferation of autologous Tconv cells (Table 1). Overall, these data demonstrate that p41+ Tr1 cells were not artificially induced as a consequence of pre-selection or cytokine-mediated polarization in vitro but were rather in vitro expanded from in vivo-induced p41+ Tr1 cells.

Table 1. Functional characterization of cytomegalovirus-specific CD4+ T-cell clones.

| Donor # | Clone | CMV epitope |

Cytokine production (pg m−1) |

% Tconv cell proliferation in the presence of the clone (Tconv:clone2:1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-10 | IL-4 | IFN-γ | ||||

| 1 | 6A5 | pp65pool | 43 | 484 | 1309 | 146 |

| 9F9 | 4 | 959 | 755 | 89 | ||

| 1F5 | 18 | 402 | 1259 | 115 | ||

| 9B10 | 25 | 590 | 1164 | 147 | ||

| 2 | 6B6 | pp65283-297 | 222 | 626 | 876 | 88 |

| 2G12 | 212 | 1333 | 1509 | 119 | ||

| 10A6 | 841 | 994 | 974 | 86 | ||

Abbreviations: CMV, cytomegalovirus; IL, interleukin.

CMVpp65+ CD4+ T-cell clones were restimulated with peptide-pulsed DC (Donor 1: CMV peptide pool; Donor 2: CMVpp65283-297) for 48 h. Thereafter, production of the cytokines IL-10, IL-4 and IFN-γ was determined from culture supernatant by CBA. Proliferation of Tconv in response to platebound anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody plus irradiated CD2− stimulator cells was analyzed in the presence of the indicated clone by carboxyfluorescein diacetate, succinimidyl ester (CFSE) dilution (Tconv without clone=100% proliferation).

Intranasal vaccination with p41 and zymosan induces Tr1 cells in mice

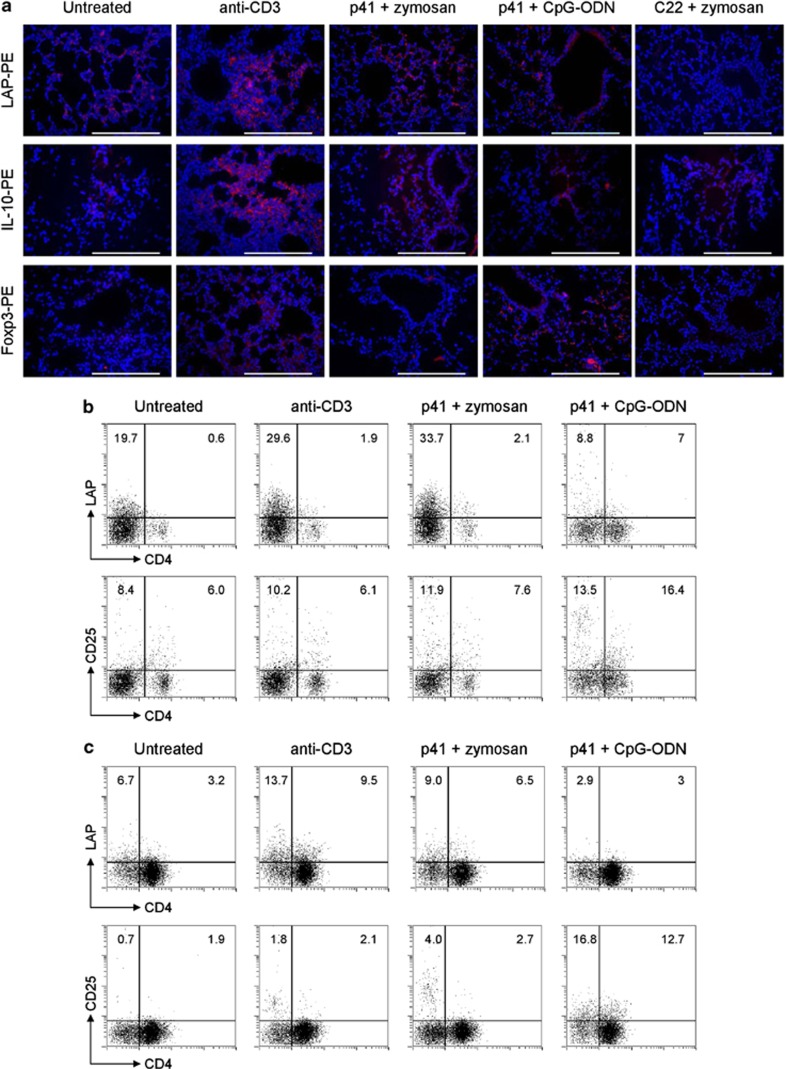

We next asked whether Tr1 cells can be induced in vivo by the p41-peptide. To this end, we vaccinated mice with the p41-peptide and zymosan or CpG-oligodeoxynucleotide (ODN), two adjuvants that have shown to support IL-10 production by murine T cells in vitro (data not shown). Animals that received anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody (mAb) intranasally served as positive control for Tr1 cell induction.36, 37 We comparatively analyzed lungs of control anti-CD3-treated mice and of mice treated with p41+zymosan or p41+CpG-ODN for the presence of LAP+, Foxp3+ and IL-10+ cells by immunofluorescence staining. Similar to mice treated with anti-CD3 mAb, mice that had received p41+zymosan revealed the presence of IL-10+ and LAP+, but not Foxp3+, cells in the lung parenchyma (Figure 3a). In contrast, IL-10+ and Foxp3+, but not LAP+, cells were present in the lungs of mice treated with p41+CpG-ODN. Neither LAP+ nor Foxp3+ cells were induced in the lungs of mice treated with zymosan+ control C22 peptide. We also used flow cytometric analysis to confirm the expansion of LAP+ cells (both CD4+ and CD4−) in the lungs (Figure 3b) and thoracic lymph nodes (TLN) (Figure 3c) of mice treated with p41+zymosan or control anti-CD3 mAb but not p41+CpG-ODN (Figures 4b and c). LAP+ cells also expressed ICOS and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) (data not shown).

Figure 3.

p41 induces murine Tr1/Treg in vivo depending on adjuvant. Immunofluorescence staining of lungs (a) and flow cytometry of lungs (b) and TLN (c) from C57BL/6 mice intranasally treated with anti-CD3, the p41-peptide or the control C22 peptide along with zymosan or CpG-ODN. Lungs were stained with anti-LAP-PE, anti-IL-10-PE or anti-Foxp3 followed by PE secondary antibody and 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole for nuclei for Tr1/Treg-cell assessment at the end of each treatment. Representative images of two independent experiments were acquired with a × 40 objective. Scale bars, 200 μm. Total cells were stimulated in vitro with anti-CD3+CD28 for 24 h before surface staining with anti-CD4-FITC (fluorescein), anti-CD25-PE and anti-LAP-PE. Numbers refer to % positive cells.

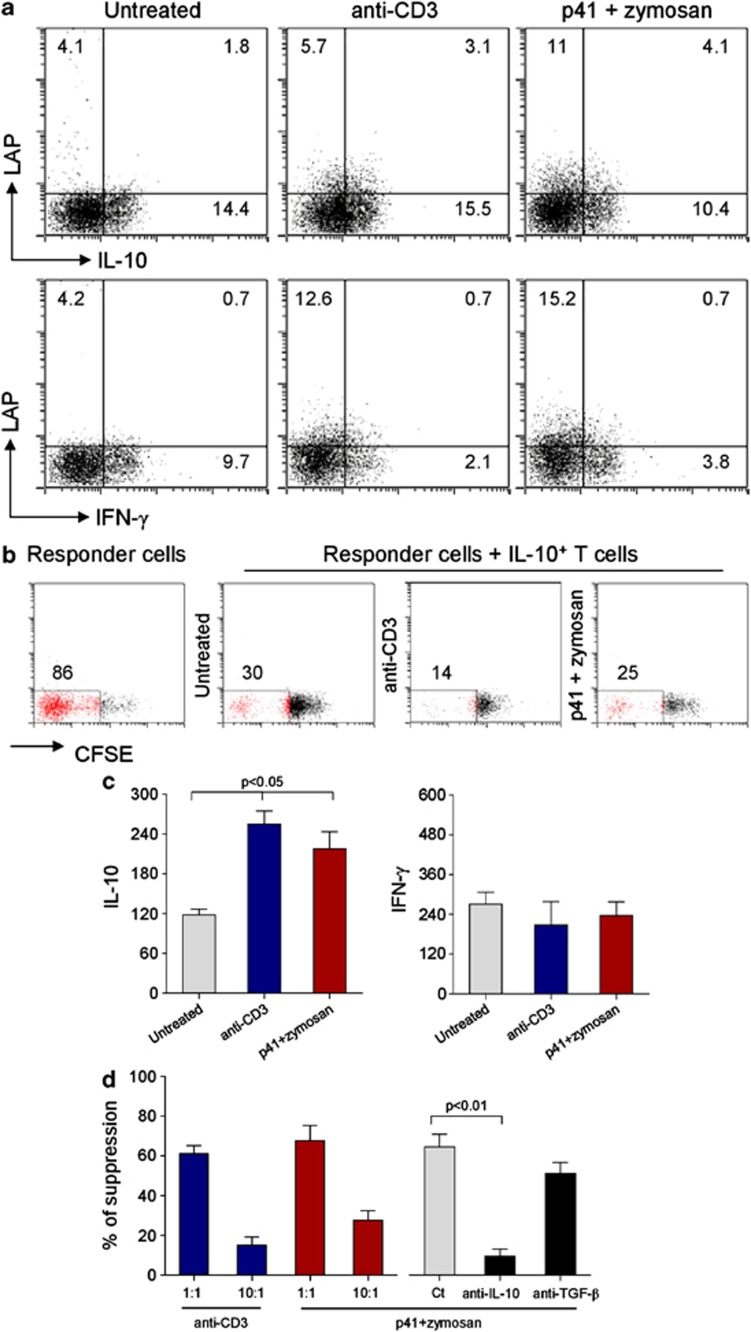

Figure 4.

Mouse Tr1 cells are IL-10+IFN-γ− and suppress T-cell proliferation. Mice were intranasally treated as decribed previously in Figure 3. (a) Total lung cells were stimulated in vitro with anti-CD3+CD28 for 24 h before surface stained with anti-LAP-PE and, once permeabilized, stained for intracellular IL-10 or IFN-γ. Numbers refer to % positive cells. (b) Suppression of proliferation of CD4+CD25–CFSE-labeled responder T cells by IL-10+ T cells (1:1 ratio) from lungs of treated mice. Cells were anti-CD3+CD28 stimulated for 72 h. The CFSE signal was analyzed by flow cytometry. The percentages of proliferating cells (red) are shown. (c) Cytokine levels (pg ml−1, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) in the supernatants of total lung cells from naive mice (untreated) or mice treated as above. Cells were stimulated in vitro with anti-CD3+CD28 for 24 h. Data are mean±s.d. P<0.05, one-way analysis of variance Bonferroni post-test. (d) Suppression of proliferation of CD4+CD25–CFSE-labeled responder T cells by purified T cells from lungs of treated mice. Cells were anti-CD3+CD28 stimulated for 72 h. Anti-IL-10 or anti-TGF-β neutralizing antibodies (50 μg ml−1) were added to cocultures at 1:1 ratio. Suppression (%, as indicated) was expressed as the relative inhibition of the percentage of CFSE cells (100 × (1% CFSElowCD4+CD25− T cells in coculture/% CFSElow CD4+CD25− T cells alone)) for CFSE-based measurement of proliferation. Data are mean values±s.d.. P-value derived from two-way analysis of variance test, P<0.01. Ct, isotype-matched antibody.

To further confirm whether the LAP+IL-10+ phenotype correlates with a Tr1-type function, we next analyzed their cytokine expression pattern and suppressive capacity. LAP+ lung cells isolated from mice treated with p41+zymosan and anti-CD3 mAb stained positive for IL-10 but not IFN-γ (Figure 4a), a finding confirmed by the ability of T cells isolated from the lungs of these animals (and similarly from TLN, data not shown) to secrete increased amounts of IL-10 but not IFN-γ upon anti-CD3 stimulation in vitro (Figure 4c). In addition, IL-10-secreting cells, isolated from lungs of p41+zymosan-treated mice, suppressed proliferation of responder CD4+ T cells in a dose- and IL-10-dependent manner as shown by titration of Tr1 cells and addition of a neutralizing mAb, respectively (Figures 4b and d). Neutralization of TGF-β had a minor effect on this suppressive capacity. Since p41+zymosan administered subcutaneously failed to induce Tr1 cells in the lungs (data not shown), our data show that LAP+ IL-10+ Tr1 cells are induced upon intranasal exposure to fungal antigens in the presence of zymosan, whereas intranasal administration of fungal antigens+CpG-ODN induced Foxp3+ iTreg, as already reported.27, 30

p41-induced Tr1 cells decrease inflammatory T cells in murine aspergillosis

We next asked for the role Tr1 cells might have in the pathogenesis of IA. To this purpose, mice, vaccinated as described above, were subsequently intranasally infected with A. fumigatus conidia and analyzed for their susceptibility to fungal infection in terms of fungal growth and inflammatory pathology. Vaccination of mice with p41+zymosan did not significantly affect fungal growth in the lung (Figure 5a) but decreased cellular infiltrates (Figure 5b) and neutrophils (Figure 5c) in the lung and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) (Figure 5b insets and numbers). Consistent with previous observations,27, 30 under conditions of Foxp3+ iTreg induction by p41+CpG-ODN treatment, both fungal burden and inflammation were decreased.

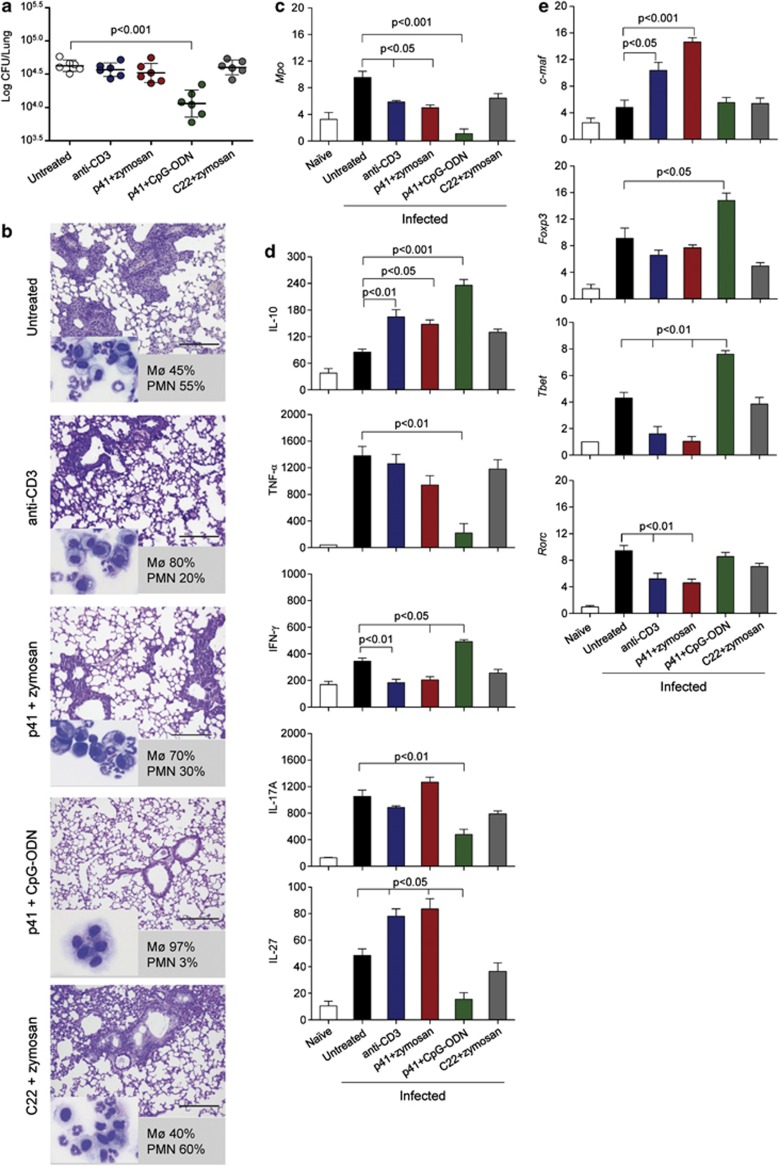

Figure 5.

p41-induced murine Tr1 cells decrease inflammatory T cells in murine aspergillosis. C57BL/6 mice were treated as decribed previously in Figure 3 and infected intranasally with live Aspergillus conidia (six mice per group). Mice were assessed for (a) lung fungal growth (log10 colony-forming unit per organ±s.d.), (b) lung histopathology (periodic acid-Schiff staining) and BAL cellular morphometry (indicated as % of mononuclear (Mø) or polymorphonuclear (PMN) cells in the inset (May–GrünwaldGiemsa staining)). Representative images of two independent experiments were acquired with a × 40 objective. Scale bars, 200 μm. (c) Mpo expression (reverse transcriptase-PCR) on total lung cells. (d) Levels of cytokines (pg ml−1) by specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (mean values±s.d., n=3) in lung homogenates. (e) Relative expression (mRNA-fold increase) of transcription factor genes (by reverse transcriptase-PCR) on purified CD4+ T cells from TLN. Assays were done at three days post-infection. P-value was determined by one-way analysis of variance Bonferroni post-test (n=3).

Quantification of the production of important effector cytokines in antifungal immune resistance23 by lung infiltration cells revealed significantly increased IL-10 but decreased IFN-γ levels under conditions of Tr1 cell induction by p41+zymosan (Figure 5d), whereas tumor necrosis factor-alpha and IL-17A production was not affected in these mice. In contrast, significantly increased levels of IFN-γ accompanied by decreased levels of IL-17A and tumor necrosis factor-alpha were observed in mice vaccinated with p41+CpG-ODN. In addition, an increase in IL-27, a dendritic cell (DC)-derived cytokine required for the differentiation of Tr1 cells in vivo,13 was observed in p41+zymosan but not p41+CpG-ODN-treated mice (Figure 5d). These data suggest that the occurrence of Tr1 cells is associated with increased IL-10 and IL-27 levels, but decreased IFN-γ levels in infection, while an induction of Foxp3+ iTreg is associated with high levels of IL-10 and IFN-γ and concomitant inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and IL-17A.

Next, we analyzed Th lineage-specific transcription factors in CD4+ T cells from TLN to receive further insight into T-cell function after vaccination with p41. Expression of c-maf, a Tr1-specific transcript,8, 12 was specifically increased after treatment with p41+zymosan and anti-CD3 mAb (Figure 5e). As expected, Foxp3 transcripts were increased after p41+CpG-ODN treatment. Of note, Th1-related Tbet and Th17-specific Rorc transcripts were decreased after vaccination with p41+zymosan but increased after p41+CpG-ODN treatment. Together, these data demonstrate differential expression of Th1/Th17-related transcription factors under Tr1- or Foxp3+ iTreg-inducing condition, suggesting that these cells differently control inflammatory Th1 and Th17 cell responses in experimental aspergillosis.

Mouse Tr1 cells are activated through Ahr and require IL-10 to exert their suppressive function

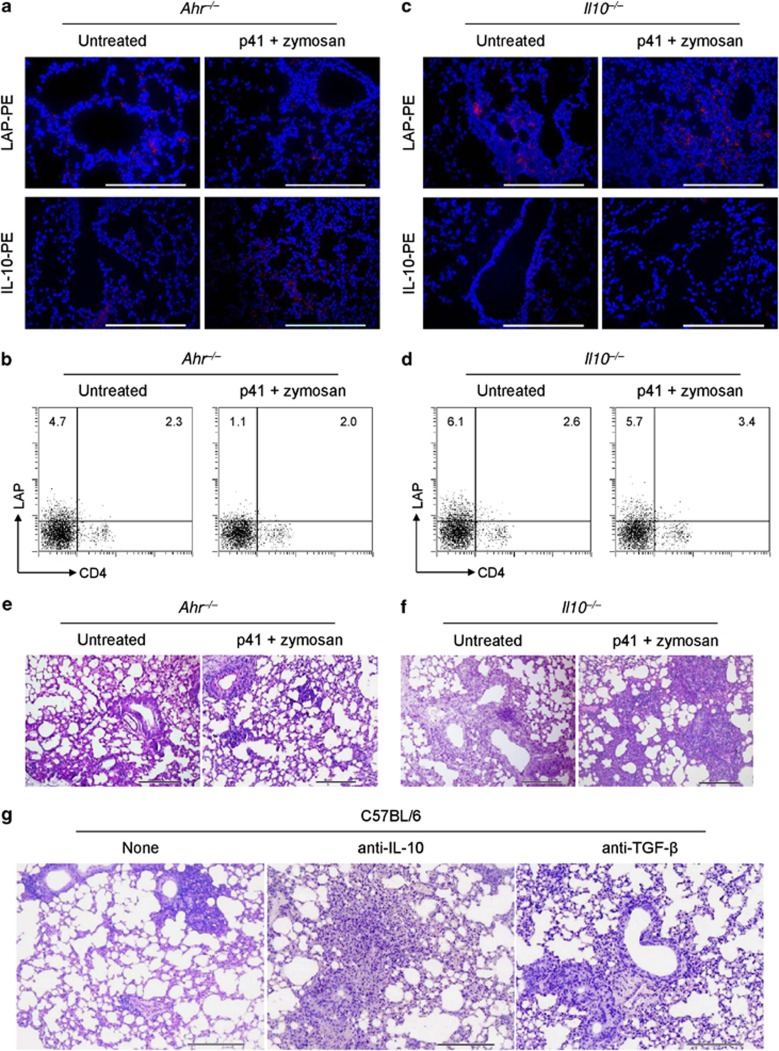

Studies in humans and mice show that differentiation of Tr1 cells in vivo requires AhR11, 36 in addition to IL-2713 but not IL-10.38 We therefore investigated Tr1 cell activation and function in Ahr–/– and Il10–/– mice. Neither LAP+ nor IL-10+ cells could be induced in the lungs of untreated Ahr–/– mice or after treatment with p41+zymosan (Figures 6a and b). In contrast, LAP+ cells were present in Il10–/– mice (Figures 6c and d). In addition, we detected a higher degree of lung inflammation in Ahr–/– and Il10–/– mice (Figures 6e and f) that could not be controlled by treatment with p41+zymosan. The treatment did not modify fungal burden (data not shown). To determine the role of IL-10 in the regulatory activity of Tr1 cells and to define the potential of TGF-β16 to this activity, mice were treated with p41+zymosan together with neutralizing IL-10 or TGF-β mAb at the time of infection. Neutralization of IL-10 and, to a lesser extent, TGF-β increased the lung inflammatory pathology (Figure 6g). These data suggest that AhR rather than IL-10 is involved in the induction of Tr1 cells, whereas the suppressor activity of these cells is mainly mediated by IL-10.

Figure 6.

Mouse Tr1 cells are activated through Ahr and require IL-10 and, partly, TGF-β to suppress. Ahr−/− or Il10−/− mice were treated and infected as decribed previously in Figure 5 and assessed for lung immunofluorescence with anti-LAP-PE or anti-IL-10-PE staining (a, c); numbers of LAP+ CD4+ T cells by flow cytometry on anti-CD3+CD28-stimulated lung cells (b, d), and lung histology (periodic acid-Schiff staining) (e, f). Cell nuclei were stained blue with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole in a and c. Representative images of two independent experiments were acquired with a × 40 objective. Scale bars, 200 μm. In b and d, numbers refer to % positive cells. (g) C57BL/6 mice were treated with p41+zymosan, infected and treated with IL-10 or TGF-β-neutralizing antibody at the time of infection. Scale bars, 200 μm. None, rat IgG1 antibody.

Discussion

There is emerging evidence that Foxp3+ Treg are involved in the regulation of antifungal immune responses. Animal and clinical studies of IA and ABPA had shown that these cells suppress overwhelming inflammatory Th1 and Th2 responses and support the generation of long-term antifungal T-cell memory.24 However, it remains unclear whether Tr1 cells, that control the maintenance of immune homeostasis to inhaled allergens,25, 39 might also be involved in maintenance of a protective antifungal immunity. In the present study, we identified for the first time A. fumigatus-specific Crf-1/p41+ Tr1 cells in mice and humans and demonstrated that these cells possess the overall features of Tr1 cells by the means of high IL-10 production, LAP expression in the absence of Foxp3 and the capacity to suppress T-cell activation in vitro and in vivo.

We identified human p41-specific Tr1 cells within the memory CD4+ T-cell pool of healthy donors after in vitro expansion under distinct culture conditions. These cells showed the characteristics of Tr1 cells in terms of their LAP expression, high IL-10 production in the absence of significant amounts of IL-4,31 and their ability to suppress in vitro proliferation of CD4+ T cells in an antigen-independent as well as p41-dependent manner. On the other hand, human p41+ memory Tr1 cells differed from previously described primary-induced Tr1 cells with respect to their transient upregulation of Foxp3 expression. However, our observation that all analyzed p41+ T-cell clones as well as CMV-specific T-cell clones upregulated Foxp3 upon restimulation, irrespective of their differentiation state and, more strikingly, CD4+CD25+CD127dim nTreg expressed higher amounts of Foxp3, strongly suggests that this expression is related to the memory state of the T-cell clones without affecting their function.40

It has recently been shown that A. fumigatus-specific Foxp3+Helios+ nTreg can be identified in healthy humans after enrichment of CD137+ T cells activated by A. fumigatus lysates.41 Although we cannot exclude that p41-specific Foxp3+Helios+ Treg exist in the peripheral blood of healthy humans, these cells were undetectable under our in vitro culture conditions, indicating that p41-peptide predominantly induces Tr1 cells in healthy humans. Therefore, these data support our notion that p41+ Tr1 cells might have a crucial role in maintenance of A. fumigatus-specific immune homeostasis. However, it would be of interest to determine whether p41-specific can be identified after distinct pre-selection strategies such as CD137+ enrichment.

Besides the characterization of human p41+ Tr1 cells, our study provided the opportunity to analyze the induction and function of p41+ Tr1 in a mouse model of aspergillosis. Analysis of p41+zymosan-vaccinated mice revealed the induction of LAP+ IL-10+ Tr1 cells in vivo, accompanied by an increase in IL-27 production by lung-infiltrating cells and c-Maf expression in CD4+ T cells isolated from TLN. As vaccination of Ahr–/– mice failed to induce LAP+ IL-10+ Tr1 cells, our data suggest that p41+ Tr1 cell differentiation is mediated via the activation of c-Maf by IL-27 in cooperation with AhR, as previously reported.8, 9, 10, 11, 13

In summary, our data show that antifungal IL-10-producing LAP+ Tr1 cells exist in the peripheral blood of healthy humans and can be induced in mice via cooperative activation of c-Maf via IL-27 and AhR. Direct comparison of p41+ Tr1 cells with Foxp3+ iTreg of the same specificity showed that these Treg-cell subsets differ in their mode of induction and, in part, in their suppressive function. Given the ability of the p41-peptide to induce protective antifungal Tr1 cells as well as Th1/Foxp3+ iTreg cells,30 we suggest that this peptide provides a versatile tool to restore protective A. fumigatus-specific immunity in clinical settings of invasive aspergillosis and ABPA.

Methods

Peptides

The A. fumigatus-derived Crf-1/p41-peptide (FHTYTIDWTKDAVTW), Crf-1/p22 peptide (TDFYFFFGKAEVVMK) andCMV-derived peptide CMVpp65283-297 (KPGKISHIMLDVAFT) were purchased from ProImmune (Oxford, UK). The CMVpp65 peptide pool was obtained from JPT (Berlin, Germany).

Ethics statement

Human studies were performed after written informed consent of the study participants, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and were approved by the institutional review board of the University hospital Würzburg (#214/12). Mouse experiments were performed according to the guidelines of the European Convention for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals used for Experimental and other Scientific Purposes (ETS No. 123) and the Italian Approved Animal Welfare Assurance A–3143–01. Legislative decree 157/2008-B regarding the animal license was obtained by the Italian Ministry of Health lasting for 3 years (2011–2014). The protocol was approved by Perugia University Ethics Committee. Infections were performed under avertin anesthesia and all efforts were made to minimize suffering.

Human blood donors and cell isolation

Blood was obtained from healthy HLA-DRB01*04-typed donors after informed consent. PBMCs were isolated by density gradient centrifugation using Ficoll/Hypaque (Biochrom, Berlin, Germany). CD4+ T cells and CD2− antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and monocytes were selected by magnetic microbeads (Miltenyi Biotech, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, CD4+ T cells were enriched by depletion of non-CD4+ T cells, CD2− APC were enriched by depletion of CD2+ cells and monocytes were positive selected by enrichment of CD14+ cells. Monocyte-derived DCs were generated as described previously.42

Generation of human p41-specific T-cell clones

p41-specific T cells were expanded from CD154+ p41-specific T cells as described previously43 or from PBMCs activated by 5 μg ml−1 p41 in the presence of 5 U ml−1 IL-2 (Chiron; Tuttlingen, Germany). At day 7, cultures were restimulated with p41-pulsed monocytes at 5:1 and expanded for additional 7 days. p41+ T cells were purified using a HLA-DRB01*04 Phycoerythrin (PE)-labeled major histocompatibility class II tetramer (Beckman Coulter, Marseille, France) and anti-PE MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotech). T-cell cloning was performed as described before.44

Flow cytometric characterization of T-cell clones

For phenotypic analysis, the following anti-human mAb were used: CD4 (Horizon V500, clone: RPA-T4), Foxp3 (AlexaFluo 647 or PE, 259D/C7; all BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA), ICOS (PE-Cy7, ISA3; eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA), LAP (PE, TW4-2F8), and Helios (Pacific Blue, 22F6, BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA). For analysis of surface markers, cells were incubated with mAbs at 4 °C for 20 min. For staining of intracellular molecules fixation/permeabilization buffers (eBiosciences) were used. Cells were analyzed by FACS-Canto II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Heidelberg, Germany) and FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR, USA). IFN-γ and IL-10 production by T-cell clones was determined from culture supernatants after 48 h of restimulation with p41-pulsed DC by cytometric bead array according to the manufacturer's instructions (CBA, BD Biosciences). Quantification of cytokine production was analyzed using FCAP Array v2.0 Software (SoftFlow, Pécs, Hungary).

Suppression assays with human T-cell clones

Responder CD4+ T cells were labeled with 1 μM carboxyfluorescein diacetate, succinimidyl ester (CFSE) (Invitrogen, Darmstadt, Germany) for 10 min at room temperature prior coculture with T-cell clones and p41-pulsed irradiated CD2− cells (30 Gy) at a 2:1:4 ratio in 96-well round bottom plates coated with 1 μg ml−1 anti-CD3 mAb as described previously.45 After 3 days, CFSE dilution was analyzed by flow cytometry. For antigen-specific suppression, PBMCs were labeled with CFSE and T-cell clones with CellVue-Claret (Polysciences, Eppelheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. CFSE-labeled PBMCs were cocultured with CellVue-Claret-labeled T-cell clones at 3:1 in the presence of 5 μg ml−1 p41-peptide and 5 U ml−1 IL-2. After 7 days, the cultures were restimulated with p41-pulsed DC at 10:1 and expanded for additional 6 days in the presence of 10 ng ml−1 IL-7 and IL-15. For transwell experiments, PBMCs and T-cell clones were separated by 0.4-μm membranes (Costar Corning Life Science, Lowell, MA, USA). Expansion of CFSE+CD4+p41+ T cells was determined by flow cytometry using the p41 tetramer.

Animals

Female C57BL/6 mice, 8–10-week old, were purchased from Charles River (Calco, Italy). Homozygous Ahr–/– and Il10–/– mice on C57BL/6 background were bred under specific pathogen-free conditions at the Animal Facility of Perugia University, Perugia, Italy.

Infection and treatments

Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of 2.5% avertin (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) before the intranasal instillation of a suspension of 2 × 107 viable conidia from the A. fumigatus AF293 strain. Mice were monitored for fungal growth (log10 colony-forming unit per lung, mean±s.d.), histopathology (periodic acid-Schiff) and lung immunofluorescence (see below). BAL fluid was collected by cannulating the trachea and washing the airways with 3 ml of phosphate-buffered saline. Total and differential cell counts were done by staining BAL smears with May-GrünwaldGiemsa reagents (Sigma-Aldrich) before analysis. At least 200 cells per cytospin preparation were counted and the absolute number of each cell type was calculated. Histology sections and cytospin preparations were observed using a BX51 microscope (Olympus, Milan, Italy) and images were captured using a high-resolution DP71 camera (Olympus). Mice were treated with a total of 60 μg of anti-IL-10 (JES5.2A5) or TGF-β (1D11) mAbs (Bioceros BV, Utrecht, The Netherlands) at the time of infection. Control mice received either a rat IgG1 mAb isotype or a murine IgG1 mAb isotype with similar effects. Mice received intranasally 0.5 μg CD3-specific antibody (clone 145-2C11, Bioceros BV, Utrecht, Netherlands) for five consecutive days, 20 μg of p41 or C22 control peptide along with 10 μg CpG ODNODN 1862) (Invitrogen, Srl, Milan, Italy) or zymosan (Sigma-Aldrich) administered at 14, 7, 3 days before the infection. Assays were done three days after the infection or a day after the end of each treatment.

Immunofluorescence of mouse sections

Lung sections were deparaffinized and stained with PE-LAP (TGF-β1, BioLegend, Campoverde Srl, Milan, Italy), PE-IL-10 (eBioscience) and polyclonal Foxp3 (abcam, Cambridge, UK) followed by goat anti-rabbit PE secondary antibody (BioLegend).

Preparation of mouse lung and thoracic lymph node cells

For isolation of lung and TLN cells, lungs and TLN were aseptically removed and cut into small pieces in cold medium. The dissected tissue was then incubated in Hank's balances salt solution without Ca and Mg (Lonza Verviers Belgium) medium containing collagenase XI (0.7 mg ml−1; Sigma-Aldrich) and type IV bovine pancreatic DNase (30 μg ml−1; Sigma-Aldrich) for 30–45 min at 37 °C. The action of the enzymes was stopped by adding 10 ml of medium, and digested lungs and TLNs were further disrupted by gently pushing the tissue through a nylon screen. The single cell suspension was then washed, centrifuged at 200 g and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.5% fetal bovine serum. CD4+ T cells (both CD25+ and CD25−) were isolated with the CD4 MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotech). Naïve CD4+CD25− T cells were isolated from lung by magnetic sorting with the CD4+CD25+ Regulatory T Cell Isolation Kit, (Miltenyi Biotech). IL-10+ cells were isolated with the Mouse IL-10 Secretion Assay Cell Enrichment and Detection Kit (Miltenyi Biotech) from non-adherent lung cells cultured on anti-CD3-coated plates (clone 145-2C11; BD PharMingen) in the presence of 2 μg ml−1 soluble anti-CD28 mAb (clone 37.51; BD PharMingen) overnight at 37 °C.

Coculture experiments with mouse Tr1 and CFSE labeling

Naïve CD4+CD25− cells were labeled with CFSE (10 mM in dimethylsulfoxide; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) and stimulated in 96-well flat bottom plates (Corning Incorporated, New York, NY, USA) with anti-CD3+/CD28+ at 1 × 105 cells per well in the presence of IL-10+ cells, at 1:1 responder:Tr1 ratio or in the presence of purified T cells at 1:1 or 10:1 ratios. Anti-IL-10 or anti-TGF-β neutralizing antibodies (50 μg ml−1) were added to cocultures at 1:1 ratio. After 72 h, CFSE signal was analyzed by flow cytometry. Suppression (%) was expressed as the relative inhibition of the percentage of CFSE cells (100 × (1-% CFSElow CD4+CD25− T cells in coculture/% CFSElow CD4+CD25− T cells alone)) for CFSE-based measurement of proliferation.

Flow cytometry and intracellular staining of mouse cells

Cells were sequentially reacted with anti-CD4 (Fluorescein, clone: GK1.5), anti-CD25 (Phycoerythrin, clone: 7D4) (Miltenyi Biotech) or anti-LAP (TGF-β1) (Phycoerythrin, clone: TW7-16B4, Biolegend, Campoverde Srl, Milan, Italy). For intracellular cytokine detection purified cells were stimulated with 200 ng ml–1 of phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1 μg ml−1of ionomycin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 h at 37 °C. Cells were cultured for four additional hours with brefeldin and then permeabilized with the CytoFix/CytoPerm kit (BD Pharmingen) for intra-cytoplasmic detection of IFN-γ (Alexa Fluor488, clone: XMG1.2, eBioscience) and IL-10 (Fluorescein, clone: JES5-16E3, Biolegend). Cells are analyzed with a FACScan flow cytofluorometer (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA, USA) equipped with CELLQuestTM software.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and real-time PCR analysis of mouse cells

The level of cytokines in lung homogenates and culture supernatants was determined by Kit enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (R&D Systems, Milan, Italy). Real-time Reverse Transcriptase-PCR was performed using the iCycleriQdetection system (Bio-Rad, Segrate (MI), Italy) and SYBR Green chemistry (Finnzymes Oy, Espoo, Finland). Cells were lysed and total RNA was extracted using RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Milan, Italy) and was reverse transcribed with Sensiscript Reverse Transcriptase (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer's directions. PCR primers for transcription factors were used as described.30 The following c-maf primers were used: sense 5′-GTAGACCACCTCAAGCAGGA-3′ antisense 3′-GAAAAATTCGGGAGAGGAAG-5′. Amplification efficiencies were validated and normalized against Gapdh. The thermal profile for SYBR Green real-time PCR was at 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation for 30 s at 95 °C and an annealing/extension step of 30 s at 60 °C. Each data point was examined for integrity by analysis of the amplification plot. The mRNA-normalized data were expressed as relative cytokine mRNA expression in treated cells compared with that of unstimulated cells.

Statistical analysis

Paired student's t-tests were used for statistical analysis of data obtained from human studies. For the analysis of murine studies, Student's t-test or analysis of variance with Bonferroni's adjustment were used to determine statistical significance (P<0.05). The data reported are either from one representative experiment out of 3–5 independent experiments (histology and FACS analysis) or pooled from 3–5 experiments. The in vivo groups consisted of 6–8 mice per group. Data were analyzed by GraphPad Prism 4.03 program (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

Acknowledgments

Human studies were supported by BayImmunNet and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft CRC/TR 124-A4 (MST). Murine studies were supported by the Specific Targeted Research Project ‘ALLFUN' (FP7−HEALTH−2009 Contract number 260338 to LR) and the Italian Grant funded by Italian Cystic Fibrosis Research Foundation, (Research Project number FFC#16/2012 to LR.). We thank Dr Cristina Massi Benedetti for digital art and editing, Sarah Zehnter for technical help on experiments with human Tr1 cells and Dr Michael Hudecek for critically reading the manuscript.

Footnotes

The Supplementary Information that accompanies this paper is available on the Immunology and Cell Biology website (http://www.nature.com/icb)

Supplementary Material

References

- Vignali DA, Collison LW, Workman CJ. How regulatory T cells work. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:523–532. doi: 10.1038/nri2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pot C, Apetoh L, Kuchroo VK. Type 1 regulatory T cells (Tr1) in autoimmunity. Semin Immunol. 2011;23:202–208. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretschmer K, Apostolou I, Hawiger D, Khazaie K, Nussenzweig MC, von Boehmer H. Inducing and expanding regulatory T cell populations by foreign antigen. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1219–1227. doi: 10.1038/ni1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun CM, Hall JA, Blank RB, Bouladoux N, Oukka M, Mora JR, et al. Small intestine lamina propria dendritic cells promote de novo generation of Foxp3 T reg cells via retinoic acid. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1775–1785. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belkaid Y, Piccirillo CA, Mendez S, Shevach EM, Sacks DL. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells control Leishmania major persistence and immunity. Nature. 2002;420:502–507. doi: 10.1038/nature01152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolacchi F, Sinistro A, Ciaprini C, Demin F, Capozzi M, Carducci FC, et al. Increased hepatitis C virus (HCV)-specific CD4+CD25+ regulatory T lymphocytes and reduced HCV-specific CD4+ T cell response in HCV-infected patients with normal versus abnormal alanine aminotransferase levels. Clin Exp Immunol. 2006;144:188–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03048.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinter AL, Hennessey M, Bell A, Kern S, Lin Y, Daucher M, et al. CD25(+)CD4(+) regulatory T cells from the peripheral blood of asymptomatic HIV-infected individuals regulate CD4(+) and CD8(+) HIV-specific T cell immune responses in vitro and are associated with favorable clinical markers of disease status. J Exp Med. 2004;200:331–343. doi: 10.1084/jem.20032069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apetoh L, Quintana FJ, Pot C, Joller N, Xiao S, Kumar D, et al. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor interacts with c-Maf to promote the differentiation of type 1 regulatory T cells induced by IL-27. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:854–861. doi: 10.1038/ni.1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awasthi A, Carrier Y, Peron JP, Bettelli E, Kamanaka M, Flavell RA, et al. A dominant function for interleukin 27 in generating interleukin 10-producing anti-inflammatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1380–1389. doi: 10.1038/ni1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi R, Farez MF, Wang Y, Kozoriz D, Quintana FJ, Weiner HL. Cutting edge: human latency-associated peptide+ T cells: a novel regulatory T cell subset. J Immunol. 2010;184:4620–4624. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi R, Kumar D, Burns EJ, Nadeau M, Dake B, Laroni A, et al. Activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor induces human type 1 regulatory T cell-like and Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:846–853. doi: 10.1038/ni.1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pot C, Jin H, Awasthi A, Liu SM, Lai CY, Madan R, et al. Cutting edge: IL-27 induces the transcription factor c-Maf, cytokine IL-21, and the costimulatory receptor ICOS that coordinately act together to promote differentiation of IL-10-producing Tr1 cells. J Immunol. 2009;183:797–801. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stumhofer JS, Silver JS, Laurence A, Porrett PM, Harris TH, Turka LA, et al. Interleukins 27 and 6 induce STAT3-mediated T cell production of interleukin 10. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1363–1371. doi: 10.1038/ni1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochi H, Abraham M, Ishikawa H, Frenkel D, Yang K, Basso AS, et al. Oral CD3-specific antibody suppresses autoimmune encephalomyelitis by inducing CD4+ CD25- LAP+ T cells. Nat Med. 2006;12:627–635. doi: 10.1038/nm1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu HY, Quintana FJ, Weiner HL. Nasal anti-CD3 antibody ameliorates lupus by inducing an IL-10-secreting CD4+ CD25- LAP+ regulatory T cell and is associated with down-regulation of IL-17+ CD4+ ICOS+ CXCR5+ follicular helper T cells. J Immunol. 2008;181:6038–6050. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.6038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pot C, Apetoh L, Awasthi A, Kuchroo VK. Induction of regulatory Tr1 cells and inhibition of T(H)17 cells by IL-27. Semin Immunol. 2011;23:438–445. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacciani V, Gregori S, Chini L, Corrente S, Chianca M, Moschese V, et al. Induction of anergic allergen-specific suppressor T cells using tolerogenic dendritic cells derived from children with allergies to house dust mites. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:727–736. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan W, So T, Mehta AK, Choi H, Croft M. Inducible CD4+LAP+Foxp3- regulatory T cells suppress allergic inflammation. J Immunol. 2011;187:6499–6507. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meiler F, Zumkehr J, Klunker S, Rückert B, Akdis CA, Akdis M. In vivo switch to IL-10-secreting T regulatory cells in high dose allergen exposure. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2887–2898. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebart H, Bollinger C, Fisch P, Sarfati J, Meisner C, Baur M, et al. Analysis of T-cell responses to Aspergillus fumigatus antigens in healthy individuals and patients with hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2002;100:4521–4528. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perruccio K, Tosti A, Burchielli E, Topini F, Ruggeri L, Carotti A, et al. Transferring functional immune responses to pathogens after haploidentical hematopoietic transplantation. Blood. 2005;106:4397–4406. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal BH. Aspergillosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1870–1884. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0808853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romani L. Immunity to fungal infections. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:275–288. doi: 10.1038/nri2939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montagnoli C, Fallarino F, Gaziano R, Bozza S, Bellocchio S, Zelante T, et al. Immunity and tolerance to Aspergillus involve functionally distinct regulatory T cells and tryptophan catabolism. J Immunol. 2006;176:1712–1723. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreindler JL, Steele C, Nguyen N, Chan YR, Pilewski JM, Alcorn JF, et al. Vitamin D3 attenuates Th2 responses to Aspergillus fumigatus mounted by CD4+ T cells from cystic fibrosis patients with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:3242–3254. doi: 10.1172/JCI42388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montagnoli C, Bozza S, Gaziano R, Zelante T, Bonifazi P, Moretti S, et al. Immunity and tolerance to Aspergillus fumigatus. Novartis Found Symp. 2006;279:66–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozza S, Clavaud C, Giovannini G, Fontaine T, Beauvais A, Sarfati J, et al. Immune sensing of Aspergillus fumigatus proteins, glycolipids, and polysaccharides and the impact on Th immunity and vaccination. J Immunol. 2009;183:2407–2414. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary N, Staab JF, Marr KA. Healthy human T-Cell Responses to Aspergillus fumigatus antigens. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9036. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolink H, Meijssen IC, Hagedoorn RS, Arentshorst M, Drijfhout JW, Mulder A, et al. Characterization of the T-cell-mediated immune response against the Aspergillus fumigatus proteins Crf1 and catalase 1 in healthy individuals. J Infect Dis. 2013;208:847–856. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuehler C, Khanna N, Bozza S, Zelante T, Moretti S, Kruhm M, et al. Cross-protective TH1 immunity against Aspergillus fumigatus and Candida albicans. Blood. 2011;117:5881–5891. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-325084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roncarolo MG, Gregori S, Battaglia M, Bacchetta R, Fleischhauer K, Levings MK. Interleukin-10-secreting type 1 regulatory T cells in rodents and humans. Immunol Rev. 2006;32:2237–2245. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton AM, Korty PE, Tran DQ, Wohlfert EA, Murray PE, Belkaid Y, et al. Expression of Helios, an Ikaros transcription factor family member, differentiates thymic-derived from peripherally induced Foxp3+ T regulatory cells. J Immunol. 2010;184:3433–3441. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0904028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getnet D, Grosso JF, Goldberg MV, Harris TJ, Yen HR, Bruno TC, et al. A role for the transcription factor Helios in human CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells. Mol Immunol. 2010;47:1595–1600. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacchetta R, Sartirana C, Levings MK, Bordignon C, Narula S, Roncarolo MG. Growth and expansion of human T regulatory type 1 cells are independent from TCR activation but require exogenous cytokines. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:2237–2245. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200208)32:8<2237::AID-IMMU2237>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern F, Bunde T, Faulhaber N, Kiecker F, Khatamzas E, Rudawski IM, et al. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) phosphoprotein 65 makes a large contribution to shaping the T cell repertoire in CMV-exposed individuals. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:1709–1716. doi: 10.1086/340637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu HY, Quintana FJ, da Cunha AP, Dake BT, Koeglsperger T, Starossom SC, et al. In vivo induction of Tr1 cells via mucosal dendritic cells and AHR signaling. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23618. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresson D, Togher L, Rodrigo E, Chen Y, Bluestone JA, Herold KC, et al. Anti-CD3 and nasal proinsulin combination therapy enhances remission from recent-onset autoimmune diabetes by inducing Tregs. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1371–1381. doi: 10.1172/JCI27191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murugaiyan G, Mittal A, Lopez-Diego R, Maier LM, Anderson DE, Weiner HL. IL-27 is a key regulator of IL-10 and IL-17 production by human CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2009;183:2435–2443. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akkoc T, Akdis M, Akdis CA. Update in the mechanisms of allergen-specific immunotheraphy. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2011;3:11–20. doi: 10.4168/aair.2011.3.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi S, Miyara M, Costantino CM, Hafler DA. FOXP3+ regulatory T cells in the human immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:490–500. doi: 10.1038/nri2785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacher P, Kniemeyer O, Schönbrunn A, Sawitzki B, Assenmacher M, Rietschel E, et al. Antigen-specific expansion of human regulatory T cells as a major tolerance mechanism against mucosal fungi Mucosal Immunol(e-pub ahead of print 4 December 2014; doi: 10.1038/mi.2013.107). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rauser G, Einsele H, Sinzger C, Wernet D, Kuntz G, Assenmacher M, et al. Rapid generation of combined CMV-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell lines for adoptive transfer into recipients of allogeneic stem cell transplants. Blood. 2004;103:3565–3572. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna N, Stuehler C, Conrad B, Lurati S, Krappmann S, Einsele H, et al. Generation of a multipathogen-specific T-cell product for adoptive immunotherapy based on activation-dependent expression of CD154. Blood. 2011;118:1121–1131. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-322610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck O, Topp MS, Koehl U, Roilides E, Simitsopoulou M, Hanisch M, et al. Generation of highly purified and functionally active human TH1 cells against Aspergillus fumigatus. Blood. 2006;107:2562–2569. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez-Villar M, Baecher-Allan CM, Hafler DA. Identification of T helper type 1-like, Foxp3+ regulatory T cells in human autoimmune disease. Nat Med. 2011;17:673–675. doi: 10.1038/nm.2389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.