Abstract

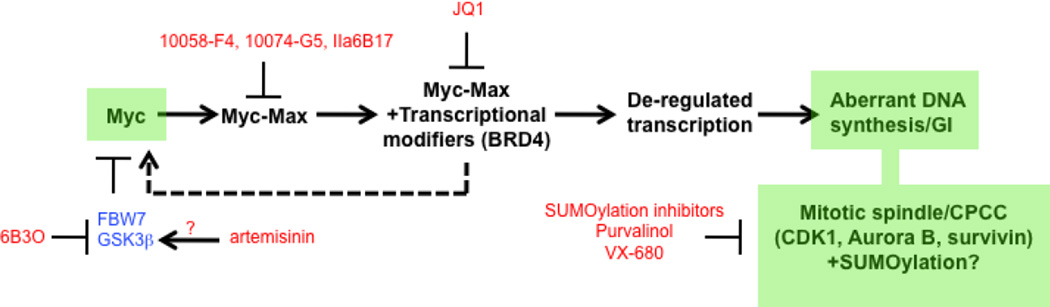

The c-Myc (Myc) oncoprotein is among the most attractive of cancer targets given that is deregulated in the majority of tumors and that its inhibition profoundly affects their growth and/or survival. However, its role as a seldom-mutated transcription factor, its lack of enzymatic activity for which suitable pharmaceutical inhibitors could be crafted and its expression by normal cells have largely been responsible for its being viewed as “undruggable”. Work over the past several years, however, has begun to reverse this idea by allowing us to view Myc within the larger context of global gene regulatory control. Thus, Myc and its obligate heterodimeric partner, Max, are integral to the coordinated recruitment and post-translational modification of components of the core transcriptional machinery. Moreover, Myc over-expression re-programs numerous critical cellular functions and alters the cell’s susceptibility to their inhibition. This new knowledge has therefore served as a framework upon which to develop new pharmaceutical approaches. These include the continuing development of small molecules which act directly to inhibit the critical Myc-Max interaction, those which act indirectly to prevent Myc-directed post-translational modifications necessary to initiate productive transcription and those which inhibit vital pathways upon which the Myc-transformed cell is particularly reliant.

Introduction

A myriad collection of correlative human studies and transgenic animal models has established beyond any reasonable doubt that deregulation of c-Myc (Myc) underlies the pathogenesis of numerous cancers and in many cases contributes to their aggressiveness (1–6). Moreover, the frequency with which this aberrant expression occurs is virtually unmatched, thus placing MYC into contention for the most frequently deregulated oncogene in human tumors. Myc amplification is the most frequent somatic copy number increase seen in tumor cells (7) and the range of neoplasms in which Myc is otherwise deregulated is wide. It includes, but is hardly confined to, many hematopoietic tumors and cancers of the central nervous system, GI track, breast, prostate and lung. Even what appears to be normally regulated Myc has been found to be linked to and critical for executing the transforming programs of upstream oncogenes (8–11). This suggests that human tumorigenesis is much more dependent upon the proper functioning of Myc than would be gleaned simply by noting its level of expression in various tumors. Thus inhibiting Myc, even when it appears to be properly behaved, may significantly impair tumor development and strongly supports the idea that Myc is an important factor upon which many oncogenic signaling pathways converge and upon which tumor growth depends (11–15). The notion that Myc is a linchpin for tumor survival and/or proliferation (14, 6,17) is one major reason why such intense interest in its therapeutic targeting has developed as it suggests that potent pharmacologic agents should have widespread utility irrespective of cancer type (18,19). This contrasts sharply with more conventional forms of targeted therapies, which are typically effective only in tumors driven by oncoproteins with specific mutations. Typical examples include tyrosine kinase inhibitors directed against Bcr-Abl and mutant forms of Jak2 in CML and myelodysplastic syndromes, respectively and serine/threonine (Ser/Thr) kinase inhibitors directed against mutant forms of B-Raf or other members of the BRAF/MEK/ERK pathway in melanoma (20,21).

A second reason that pharmacologic inhibition of Myc is a particularly compelling concept is that, in addition to its role in tumor cells, Myc is now appreciated as being necessary to sustain a healthy tumor matrix. In model systems of Myc-driven neoplasms, expression of the oncoprotein by the tumor has been shown to be required for tumor neo-vascularization and presumably operates by up-regulating the expression of genes encoding proteins such as VEGF and FGF to encourage and sustain this process (22,23). Proliferating cancer cells, presumably Myc-dependent if not necessarily Myc-driven, can also secrete factors such as CSF1 and IL4, which are necessary for the recruitment for macrophages and endothelial precursors from bone marrow sources (23,24–27).

The requirement for Myc to support the extracellular matrix also extends to its expression by these non-neoplastic cellular constituents. For example, the alternative activation pathway through which tumor-associated macrophages produce tumor-promoting and pro-invasive factors such as VEGF, TGF-β and MMP9 is highly dependent on their expression of endogenous Myc (23,25,26). Similarly, the proliferation and expansion of tumor-supporting cellular components including smooth muscle cells, pericytes and fibroblasts are all undoubtedly dependent on their properly controlled regulation of Myc to ensure that they keep apace with the neoplasm’s growth (23,24,28,29). Interestingly, the expression of Myc by normal endothelial cells does not appear to be required for their proliferation and participation in vasculogenesis but is required for the genesis of endothelial precursors from bone marrow-derived progenitors (30–32).

One example of the reliance on tumor cell Myc expression for maintaining the tumor matrix comes from work showing that the genetic silencing of endogenous tumor cell Myc in SV40-large T and small t-antigen-driven pancreatic β-cell tumors is associated with a widespread collapse of the tumor vasculature and loss of infiltrating inflammatory cells, both of which precede any overt tumor apoptosis and regression (13). This suggests that the failure to maintain a proper extratumoral environment is a cause rather than an effect of tumor regression, a claim that was substantiated by microarray analyses demonstrating that inhibiting Myc genetically in the β–cell tumors was associated with a rapid dysregulation of numerous tumor associated cytokines, chemokines and other inflammatory mediators that likely fortify the extratumoral cellular environment. Taken together, these studies suggest that pharmacologic targeting of Myc would directly affect separate yet absolutely essential compartments comprised on the one hand of the tumor itself and on the other by its matrix and associated normal cell populations.

Interaction between Myc, Max and DNA

The monomeric form of Myc’s bHLH-ZIP dimerization domain is largely unstructured in solution and possesses only about 27% α–helical content (33–35). Such regions of intrinsic disorder (ID) are common and occur in approximately one-third of all eukaryotic proteins and as many as 60–80% of those involved in normal signal transduction and neurodegenerative disorders (36–39). ID regions are characterized by extensive backbone flexibility and an absence of anything more than transient tertiary structure (40). The amino acid sequences comprising ID regions are both different from and less complex than those from more ordered regions (40–42). It has been suggested that the extended nature of ID regions, and the consequent solvent-exposed surface area, allows them to participate in coupled folding and binding reactions and to efficiently form large interfaces with diverse targets (36,37,43,44). This results in relatively weak but highly specific interactions such that only the correct partner supplies the required complementary surface to generate sufficient enthalpic gain to offset the entropic loss associated with folding (45). These interactions can occur through two distinct but non-mutually exclusive mechanisms in which a disordered protein can acquire order either prior to or after binding to its target (the so-called “conformational selection” and “induced fit” models, respectively (46). This versatile and highly adaptive behavior is also efficient and economical and is well illustrated in the case of Max whose bHLH domain is also highly disordered and whose interaction with Myc as well as other Myc family members (N-Myc and L-Myc), Mnt, Mga and each of the four members of the Mad/Mxd bHLH-ZIP family could well be determined and facilitated by this ID-dependent structural flexibility to promote distinct tertiary structures (39–41). A more striking ID-mediated interaction between Myc’s bHLH-ZIP domain and even less related proteins such as AP2, Brca1, Miz1, and Nmi (50–52) might also explain the former protein’s highly variable but specific binding preferences. Such structural adaptability toward its binding partners also suggests a means to leverage the anticipated susceptibility of ID regions to small molecule binding. In such a model, it can be envisioned that this interaction would “lock in” one or more structures, thereby exploiting the entropic gain of a disordered system to inhibit the interaction of the protein with one member of its partner repertoire. Protein conformations prone to interacting with a desired target would, upon binding to a small molecule, be removed from the ensemble of potentially reactive structures without affecting those ID conformations capable of interacting with other protein targets and thus providing considerable specificity.

Upon interacting with Max, Myc’s bHLH-ZIP domain undergoes coupled folding and binding that leads to the formation of a parallel, left-handed, four-helix bundle where each monomer forms two -helices separated by a ca. 10 residue loop. The overall Myc α-helical content of this stable and relatively rigid structure is approximately 70% and its thermal stability is considerably greater than that of the Max homodimer (ca. 55°C vs. 38°C) (33). Further increases in heterodimer α–helical content and stability are achieved upon binding to DNA containing the consensus CACGTG E-box motif (70% to 84% and 55°C to 73°C, respectively) in keeping with the behavior of other dimeric transcription factors (33,55–58). Although it seems likely that Myc-Max heterotetramers (54) and the various proteins that associate with Myc in its chromatin-bound, transcriptionally active form provide even further stability, the degree to which this occurs has not been investigated although ample precedent for this type of influence, both positive and negative, has been documented in the case of other proteins (48).

Heterodimers comprised exclusively of the Zip domains of Myc and Max form readily but are much less stable than homodimers and heterodimers formed by the “pure” pZIP proteins Jun, Fos and GCN4 (59–61) and are more in keeping with the weaker homodimers formed by the ZIP domain of TFEB, an E-box-binding transcription factor that, like Myc, also contains an adjacent bHLH domain (62). This suggests that the individual HLH and ZIP domains act cooperatively to facilitate one another’s relatively poor dimerization capabilities into a stable structure whose free energy of association is greater than that of its individual interacting domains. It seems likely that the instability of each of these segments facilitated the discovery of small molecules that could prevent and/or disrupt the dimerization process (62). Moreover, because a minor part of the dimer interface may contribute disproportionately to the affinity between the proteins (63,64), targeting these “hot spots” and restricting their conformational freedom may well be sufficient for inhibiting protein–protein interactions.

Control of transcription complex assembly by Myc

The binding of Myc-Max heterodimers to DNA initiates the organized recruitment of well over 20 associated factors into a large, chromatin-associated complex who precise composition and stoichiometry likely depend upon a number of non-mutually exclusive factors including the cell type, its proliferative and metabolic status, the identities and activities of other neighboring chromatin-associated proteins, whether the bound E-boxes are “high affinity” or “low affinity”, the spacing between adjacent sites, and the interaction between Myc-Max dimers and their associated factors bound distally and brought into contact by chromatin looping (65–71). The net result of this multiprotein complex recruitment is a global change in chromatin architecture and function such that at least one-third of actively transcribed genes are bound by Myc within 1 kb of their transcriptional initiation site (71,72). With few exceptions, the precise protein-protein contacts of each of these factors and their temporal order of their associations have not been clearly elucidated. The most abundant and well-characterized factors include TRRAP, GCN5, TIP48, TIP49, TIP60, BAF53, CBP and p300 (66,73–76). Among the functions associated with these proteins are ATPase activities of TIP48 and TIP 49 and histone acetyl transferase activities of GCN5, TIP60, CBP and p300. The latter four enzymes tend to be quite specific for the acetylation of histones H3 and H4 and their respective lysine 4 residues. However, they also acetylate Myc itself and enhance its stability by at least three-fold although the precise acetylation patterns inmparted by each enzyme are distinct (75,76). pTEFb (transcription elongation factor b), an RNA Pol II pause release factor comprised of cyclins T1 and T2 and CDK9 and TFII-H an RNA Pol II promoter clearance factor are also components of this complex with pTEFb binding directly to Myc (56,77,78). Both pTEFb and TFII-H possess intrinsic kinase activities and phosphorylate the C-terminal domain of RNA Pol II (79–82). pTEFb also appears to be responsible for guiding other histone modifications such as histone 2B ubiquitination and histone H3 methylation (83). The pause factors DSIF and NELF also associate with and are phosphorylated and inhibited by pTEFb (68,71). These are then recruited to the complex by BRD4, an acetylated lysine (KAc)-recognizing member of the bromodomain and extra-terminal (BET) family (84–80).

At least part of BRD4’s ability to recruit pTEFb is likely explained by the fact that the cyclin T1 component of pTEFb is acetylated on at least 3 lysine residues, thus promoting its interaction with the BRD4 bromodomain (90). pTEFb suppresses abortive Pol II-mediated negative strand transcriptional initiation while relieving positive strand pausing and facilitating uni-directional read-through of authentic transcripts (71, 91–95). Direct Myc inhibition leads to a loss of Pol II-mediated elongation without affecting the amount of promoter proximal-bound Pol II. It also reduces Ser2-phosphorylated Pol II, which is the form associated with elongation, but has minimal effects on Ser5-phosphorylated Pol II, the form associated with initiation (71). It has been suggested that Myc overexpression or deregulation leads to a more efficient recruitment of pTEFb at bound promoters via their direct interaction (65, 68,71) thus relieving transcriptional block by permitting positive strand Pol II read-through and repressing antisense transcription (71).

Many of the above components, notably DSIF and pTEFb are members of other Myc-independent multiprotein transcriptional complexes, thus attesting to their dynamic nature and versatility (95). Additional histone modification mediated by Myc and its associated factors has been reported to occur at the level of histone H3K9 di- and tri- de-methylation and involves the recruitment of one or more demethylases by members of the JARID1 family of proteins which bind directly to the bHLH-ZIP domain of Myc (96,97). The JARID1 family consists of a single ortholog in Drosophila, where it is known as Lid and four members in mammalian cells, which are expressed in a tissue-specific manner. Myc inhibits the activity of the JARID1-demethylase complex, thus forming a positive feedback loop to ensure high levels of H3K4 methylation during periods of robust Myc-mediated transcription (96,97).

In summary, Myc appears to be a universal but unequal amplifier of gene expression that functions less to regulate the actual amount of RNA Pol II bound to actively transcribed genes than to reduce anti-sense transcription and relieve sense strand pausing. This process is orchestrated by the complex and dynamic interplay amongst a large complex of Myc-associated proteins whose precise constituents may be determined by a variety of both cell- and growth-specific conditions. Post-translational acetylation of histones, primarily H3 and H4, is instrumental in this process as is the phosphorylation of the C-terminal domain of RNA PolII. Loss of Myc is associated with the rapid loss of these modifications and transcriptional attenuation. The transforming function of Myc is likely due to the over-expression of genes containing high affinity binding sites that respond to both physiologic and pathologically elevated levels of Myc as well as to genes with low affinity sites that respond only to the highest levels of the oncoprotein generated by its deregulation.

KAc as a Determinant of Myc Binding and Transcription

In addition to the intrinsic affinity of a binding site for Myc-Max heterodimers, it is known that binding is also facilitated by the level of pre-existing chromatin acetylation, which tends to cluster in so-called euchromatic islands located at the 5’-ends of actively transcribed genes that are also associated with methylated histones (67,98–100). Acetylation but not methylation is further enhanced upon DNA binding by Myc via the mechanisms discussed above and Myc itself appears to be acetylated and stabilized as a result (67,75,76,102). An important question is whether the pre-existing KAc tags are functionally different from those that appear subsequent to Myc-Max binding. It is tempting to speculate that the former tend to be represented by histone H3 acetylation and that they serve as epigenetic landmarks or molecular signposts that guide Myc-Max complexes to their intended binding sites so as to minimize both the need for chromatin scanning and the possibility that transcription will initiate at unintended sites. In contrast, KAc tags appearing after the Myc-Max dimer and its accessory proteins are bound by DNA, would provide the opportunity for BRD4 to engage acetylated pTEFb (and possibly Myc itself) and perhaps allow a more robust acetylation of the surrounding chromatin and the transcriptional complex by virtue of a highly functional assembly of multiple acetylases.

The recognition by BRD4 of acetylated histones and pTEFb is a critical step in the transcriptional control of Myc-regulated genes as siRNA-mediated suppression of BRD4 in acute myeloid leukemia cells leads to terminal myeloid differentiation and the elimination of myeloid stem cells (85) in a manner that was precisely phenocopied by a small molecule inhibitor of KAc recognition by BRD4 (see below).

Inhibition of Myc: Challenges and Opportunities

The foregoing summary reveals the complex and dynamic molecular anatomy underlying Myc-driven transcriptional regulation. In doing so, it provides a framework within which to consider how the function of this machinery can potentially be impaired in highly specific and perhaps complementary ways. It also highlights some of the theoretical and practical barriers to the design and implementation of strategies designed to target Myc. Recent insights suggest that, while some of these barriers will be difficult to overcome, they are not insurmountable. We discuss some of these impediments below and how they have been, or are being, addressed

First, unlike the case for many other oncoproteins which drive transformation as a result of protein mutations, Myc-driven cancers are virtually always caused by the oncoprotein’s overexpression and/or de-regulation. Myc coding region mutations, when they occur at all, are largely confined to a relatively small subgroup of Burkitt’s and AIDS-related lymphomas and generally serve only to stabilize an otherwise normal Myc protein (104–108). In virtually all other cases, no opportunities exist to target a cancer-specific mutant form of the oncoprotein as there are, for example, in melanomas with B-Raf mutations, non-small cell lung cancers with EGFR mutations or CML with Bcr-Abl translocations. Second, unlike these typical examples, all of which are protein kinases and all of which are more susceptible to inhibition by small molecules than their wild-type counterparts, Myc possesses no intrinsic enzymatic activity. Therefore, the design of Myc-specific decoy substrates, based upon principles that have guided targeted therapeutic strategies against other oncoproteins for the better part of two decades (109) is not a viable option for the development of direct Myc inhibitors. Moreover, approaches that target the kinases associated with the Myc transcriptional complex such with pTEFb or TFII-H would likely be associated with unacceptable toxicities given the ubiquity with which these factors regulate normal gene expression. Together, these observations underlie the third concern, namely that because normal and cancer cells express identical forms of Myc, is it possible that Myc inhibitors might simply be too non-specific and toxic to be used effectively? We will address the first and last of these concerns together given that without a satisfactory way to allay these potential problems, Myc inhibitors, no matter how ingeniously designed, would likely have limited appeal.

Many and perhaps all Myc-driven tumors seem to be particularly reliant on or “addicted” to high levels of the oncoprotein (110,111). Evidence for this is provided by studies showing that controlled shutdown of the high-level transgenic Myc expression that drives tumorigenesis in certain mouse models is associated with rapid tumor regression and/or apoptosis (1). Indeed, in some cases, only transient Myc inhibition is necessary for sustained tumor regression whereas in others, re-expression, rather than leading to tumor re-growth, is associated with massive apoptosis (112). Other models in which the expression levels of Myc can be fine-tuned have shown that even slight increases in its level can promote proliferation in otherwise normal tissues (113). Given recent insights into the way that Myc controls metabolism, it seems likely that such sensitivity has a foundation in the high reliance of all rapidly proliferating cells on glycolysis and glutamine as sources of anabolic substrates and oxidatively-generated energy, respectively (110,114,115). Collectively, these findings suggest that Myc inhibition in tumor cells might be more consequential than an equivalent degree of inhibition in normal cells. With regard to this latter point, it is well know that Myc is generally expressed at low to undetectable levels in most organs consistent with the quiescent nature of most of their component cells. This would be expected to provide a relatively large therapeutic window within which to launch an attack on the aberrantly expressed Myc that is reactivated in tumor cells and that, if expressed at all in normal cells, would otherwise be confined to a slowly proliferating sub-population. Of course, the exception to this simplistic model is that highly proliferative cellular compartments do in fact exist in hematopoietic and gastro-intestinal precursor cell populations. Thus, Myc inhibitors might at the very least be expected to have side effects that would manifest themselves as bone marrow aplasia and loss of intestinal villus integrity. These toxicities would be akin to those encountered following treatment with conventional cytotoxic agents that non-specifically target all proliferating cells; in fact, they are actually seen following the organism-wide inhibition of Myc by genetic means in mice (9). Surprising, and as yet unexplained, is that these side effects are not only relatively mild but are transient, even in the face of chronic Myc suppression (9). These experiments support the idea that many tumors are much more sensitive to Myc inhibition than their normal cell counterparts, that their eradication might actually be enhanced by intermittent therapies, and that the anticipated side effects would not only be entirely predictable but well-tolerated as well.

What about the lack of any demonstrable Myc enzymatic activity for which inhibitors could be designed? This arguably presents the greatest challenge as it closes the door on an approach that has led to the greatest advancements in targeted therapy. Unfortunately, there are only a limited number of ways around this obstacle, which are described below in their individual sections. They include disrupting protein-protein interactions (PPIs), either those between Myc and Max (direct inhibitors) or between Myc-Max and other proteins (indirect inhibitors). Alternatively, one might capitalize on unique susceptibilities of tumor cells that arise specifically as a result of Myc deregulation (synthetic lethality).

Disruption of PPIs: practical considerations

The selective disruption of PPIs by small molecules has long been considered a therapeutic Holy Grail, made even more tantalizing by the importance of PPIs in normal cellular signaling pathways and abnormal PPIs in oncologic, cardiovascular and neurodegenerative disorders (38–46). Yet the attainment of this goal has been tempered by a number of caveats, some of which are quite compelling. First, unlike enzyme inhibitors, which typically compete with natural substrates for binding to naturally engineered pockets that are shielded from their aqueous environment, small molecule inhibitors of PPIs must prevent or disrupt interactions that occur over relatively large surface areas (generally in the range of 1000–3000 Å2) that are associated with high free energies of association and whose interfaces are relatively flat, featureless and devoid of the more geographically prominent regions that tend to accommodate small molecules readily (116–119). The problem is further amplified in the case of Myc specifically because of the inherent disorder of its dimerization domain (120). Additionally, the key interacting residues that initiate the PPIs at such sites are generally not immediately apparent even if crystallographic structures are used as guides. For these reasons, PPIs have long been considered to be “undruggable” (119,121,122). Adding relevancy to these concerns for the purpose of this specific review is the fact that the crystal structure of the Myc-Max heterodimer also fails to reveal any obvious targetable pockets along the contact interface (54). These concerns have been partly tempered by the finding that some if not all PPIs may be initiated by a small (~500 Å2) area within the larger interacting region whose constituent amino acids contribute disproportionately to the free energy of binding of the entire interacting surface. These domains tend to occur near the geometric center of the protein-protein interface and to be comprised of aromatic amino acids. This suggests that small molecules that bind to and distort such regions might exert a disproportionate effect on PPIs (63,123). In fact, small compounds of this nature have now been shown to be relatively potent PPI inhibitors. These include the nutlins, which interfere with the interaction between TP53 and its suppressor HDM2, and ABT-737 (and its derivatives ABT-263 and ABT-199), which serves as a BH3 mimetic to prevent the interaction between the pro-survival members of the Bcl-2 family such as Bcl-2 itself, Bcl-xL and Bcl-w, and the pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 members such as Bax and Bak (124,125). Additional small molecules that inhibit Stat3 PPIs have recently shown considerable promise as well (126,127). Finally, small molecules designed to mimic aspects of protein secondary structure such as α-helices, β–sheets, and β–strands have also been shown promise as PPI inhibitors (127,128).

Direct Inhibitors

Peptidomimetic inhibitors

The first small molecule direct Myc inhibitors were described by Berg et al (129) who monitored the dissociation of purified, recombinant MycCFP and MaxYFP fusion proteins using an elegant FRET-based assay. They screened a small (7000 member) peptidomimetic library and identified five active compounds, four of which were evaluated further by ELISA- and electrophoretic mobility shift (EMSA)-based assays of Myc-Max interaction. Using a single concentration of each compound (25 µM) they were able to consistently obtain low (12–%) but reproducible inhibition of heterodimerization in the FRET assay, and IC50s of 75–250 µM and 50–162 µM in the ELISA and EMSA assays, respectively. Disruption of DNA binding by one of the compounds could not be demonstrated.

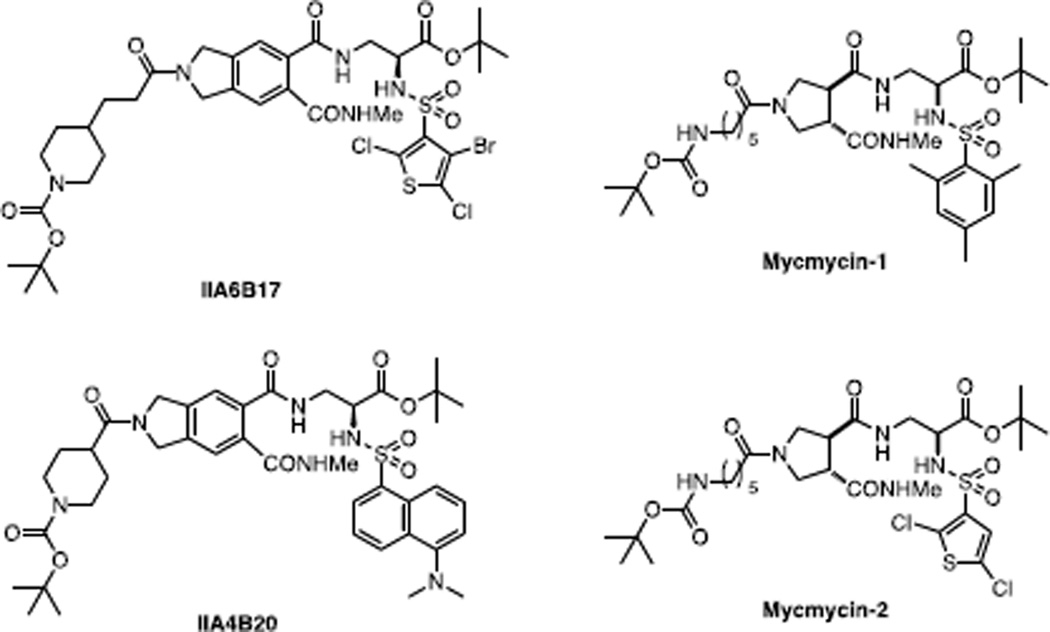

Having identified three compounds that gave consistent results in three independent assays of Myc-Max dimerization, Berg et al (129) then asked if they could selectively abrogate the appearance of transformed foci in chick embryo fibroblasts (CEFS) in response to Myc overexpression versus Src and Jun overexpression. The best of these compounds (IIA6B17 and IIA4B20) showed Myc/Src/Jun IC50s of 18 µM/>35 µM/18 µM and 20 µM/>35 µM/35 µM, respectively) (Fig. 1). At the highest concentrations tested (30–35 µM) both compounds, particularly IIA6B17 also significantly reduced the growth of normal CEFs. Collectively, these findings raise a number of points. First, given the relatively poor performance in FRET, ELISA and EMSA assays, their relative potency in cell-based assay was surprising. However, as described below for other Myc inhibitors (11,130), imperfect correlations among these assays tends to be the norm and likely relate to issues of cellular uptake, distribution and stability that are not accounted for in the former assays.

Fig. 1.

Structures of IIA6B17 and IIA4B20 (129) and their analogs mycmycin-1 and mycmycin-2 (132).

Second, the finding of some selectivity for Myc-mediated transformation can likely be explained by “oncogene” addiction of transformed cells which are more reliant on high levels of Myc to maintain this state than they are to maintain normal functions. In other words, lowering Myc levels in these cells even modestly exerts a disproportionate effect on transformation relative to “normal” cellular functions under its purview. On the other hand, the inhibition of Jun transformation and normal cell proliferation could be explained by a common mechanism, namely the reliance of all cells, transformed or otherwise, on endogenous levels of Myc for rapid growth under any circumstance. Somewhat more surprising was the relative resistance or Src-transformed cells given that transformation by this oncogene is well-known to rely on functional Myc (131). However, it is quite possible that, under the conditions of these experiments, Src-transformed cells utilize alternate and Myc-independent pathways to overcome the effect of these inhibitors.

In a follow up to the study of Berg et al (129), Shi et al (132) derived 120 analogs each of IIA6B17 and IIA4B20 and screened them at a single concentration (20 µM) for their ability to inhibit colony formation by Myc-transformed CEFs. Two of the compounds thus screened by this biological assay, “mycmycin-1” and “mycmycin-2” (Fig. 1) were found to be highly specific (IC95=20 µM) and had no effect on colony formation by either Src- or Jun-transformed CEFs. As had been the case for IIA6B17 and IIA4B20, both mycmycin-1 and mycmycin-2 were able to prevent the association of recombinant Myc and Max proteins.

“Credit card” inhibitors

In a novel, structure-based, rational approach, Xu et al (133) capitalized on the fact that small regions within ID protein-protein interfaces, particularly those enriched for amino acids such as Trp, Tyr, His and other hydrophobic residues, contribute a disproportionate fraction of the free energy of binding (63,64). They viewed these amino acids as slots or “card readers” within an otherwise flat surface and hypothesized that the insertion of a planar or “credit card”-like molecule would be a potentially effective way to block the PPI. Xu et al (133) then designed a library of planar structures with hydrophobic cores that was predicted to make favorable enthalpic contributions from van der Walls interactions, π–stacking and desolvation as well as favorable entropy gains arising from hydrophobic effects. Despite the small size of the library (285 structures), 40 hits were obtained using the same FRET-based assay used by Berg et al (129) and four were evaluated in greater depth. After showing that these functioned to disrupt Myc-Max heterodimer DNA binding in a standard EMSA assay (IC50s =17–36 µM), Xu et al (133) then employed an elegant far UV CD-based assay using synthetic Myc and Max bHLH-ZIP peptides tethered by thioester ligation. Surprisingly, they found the overall α–helical content of the highly structured dimer to be conserved upon addition of the compounds. They speculated that the compounds might disrupt the inter-helix contacts between Myc and Max thereby giving a similar per-residue normalized helicity signal even in the absence of a PPI. Another explanation is that the credit card molecules do not actually cause Myc-Max dissociation but rather perturb the structure of the dimer in a way that preserves it overall α-helical integrity but abrogates DNA binding.

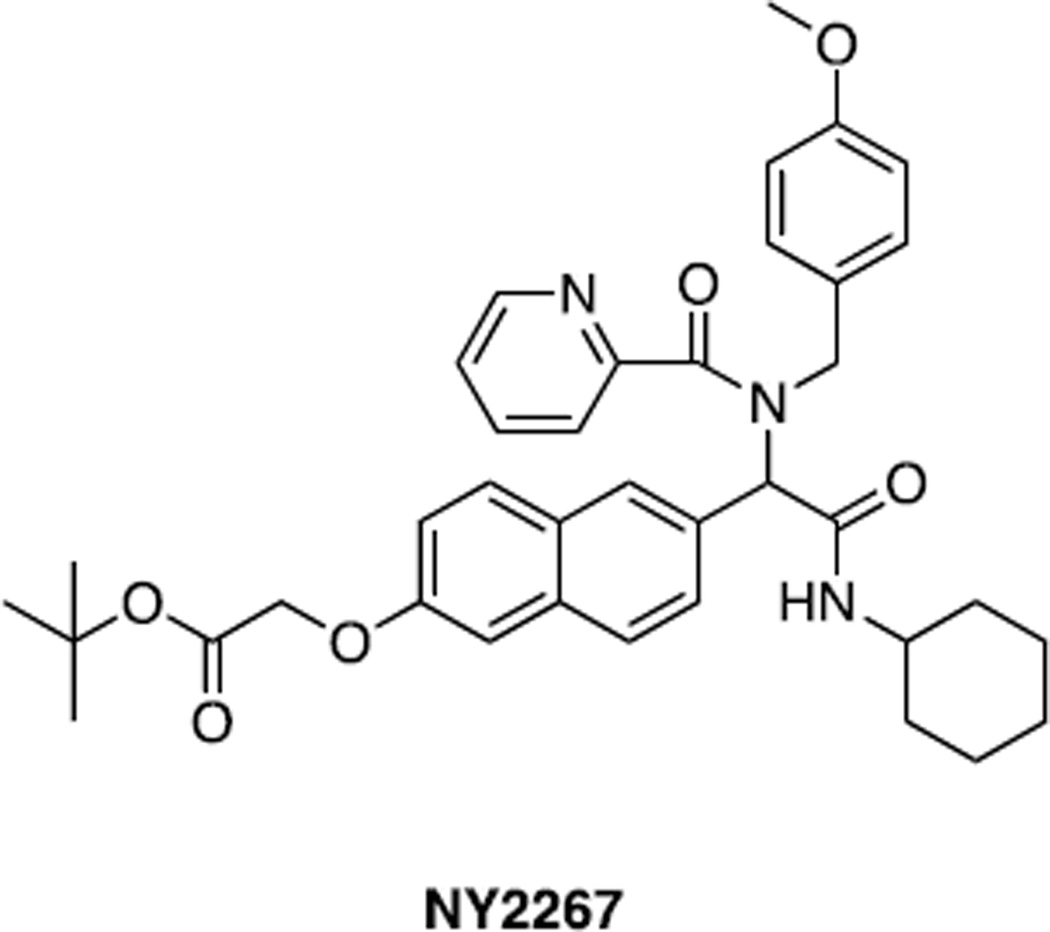

Xu et al (133) also evaluated the above compounds for their ability to inhibit oncogenic transformation. One in particular, NY2267 (Fig. 2) shared significant selectivity for Myc transformed CEFs versus cells transformed by Src, Jun or PI3 kinase. Interestingly, and despite this seemingly selective effect, tests of the compounds with Myc, Jun and NF-κB reporter vectors indicated that NY2267 was unable to discriminate between Myc and Jun luciferase reporters.

Fig. 2.

Structure of NZY2267 (see ref. 133)

Mycro1 and Mycro2

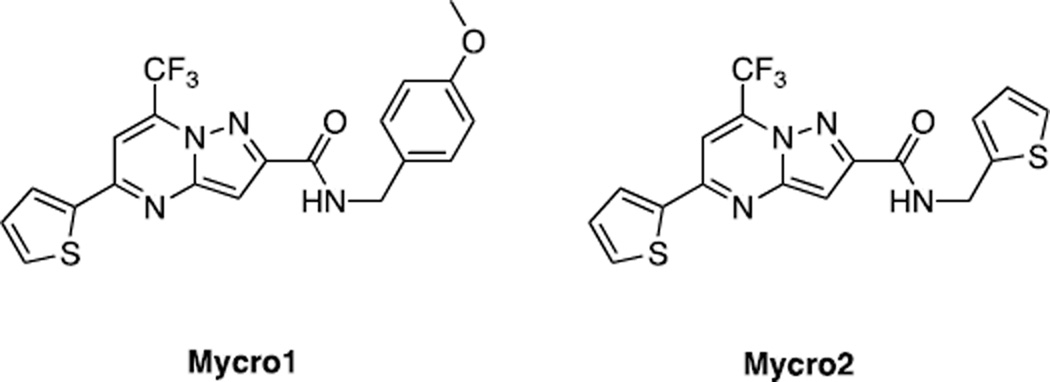

Kiessling et (134) al. developed a fluorescence polarization (FP)-based assay that allowed quantification of Myc-Max bHLH-ZIP heterodimer binding to a fluorophore-tagged, E-box-containing oligonucleotide and the identification of small molecule inhibitors of this interaction. A screen of a 17,298 member library identified a pyrazolo[1,5-α]pyrimidine dubbed “Mycro1” and a subsequent analysis of structure-activity relationships with commercially available derivatives identified an analog, Mycro2, that were subsequently evaluated in more depth. Mycro1 and Mycro2 (Fig. 3) inhibited DNA binding with IC50s of 30 µM and 23 µM, respectively. The IC50s for Max homodimeric binding to the same oligonucleotide were 2–3-fold higher thus indicating reasonably good selectivity for the heterodimer. Further evaluation against CEBPα and jun bZIP homodimers confirmed the compound’s specificity (IC50s >100 µM for each), particularly in the case of Mycro2 and neither compound affected the interactions between two SH2 domains. EMSA assays confirmed these results. Using CFP-Myc and GST-Max fusion proteins in standard pulldown experiments Kiessling et al (134) also provided evidence that the Mycro1- and Mycro2-mediated loss of DNA binding was actually due to the loss of heterodimerization.

Fig. 3.

Structures of Mycro1 and Mycro2.

Testing in a series of cell lines showed that Mycro1 and Mycro2 inhibited proliferation in a dose-dependent manner in Burkitt lymphoma, breast cancer and osteogenic sarcoma and non-transformed NIH3T3 cells. For both cell types, IC50s after 5–7 days of treatment were nearly identical for the two compounds (10–20 µM). Interestingly, they had no effect on the proliferation of PC12 pheochromocytoma cells which contain no Max protein and are therefore thought to be Myc-Max independent (135). As discussed above, the relative inability to discriminate between transformed and non-transformed cells is to be expected for direct inhibitors. Somewhat surprising was that the authors did not report any evidence of apoptosis in their treated cell lines. They attributed this to a lack of non-specific toxicity, although more likely it was due to incomplete intracellular Myc-Max association so as to inhibit proliferation while still allowing sufficient heterodimer association to maintain viability.

In additional studies, Kiessling et al (134) showed that, at the same concentrations used to achieve proliferative arrest, both Mycro1 and Mycro2 selectively inhibited the expression of an E-box-containing reporter vector relative to similar reporters bearing AP1 or serum response elements.

Finally, Mycro1 and Mycro2 inhibited anchorage-independent growth of Myc-transformed fibroblasts by as much as 60% while exerting little effect on Src-transformed cells. Not determined from these studies was whether the inhibition of colony formation was due to a Myc-specific property of transformation or simply to an overall inhibition of proliferation as described earlier for NIH3T3 fibroblasts. Similarly, the resistance of Src-transformed cell growth in soft agar suggested that this oncogene rendered cells relatively Myc-independent.

In a follow-up study, the same group reported the results of a screen of a ~1700 member library of pyrazolo[1,5-α]pyrimidines based upon the structures of Mycro1 and Mycro2 (136). Five compounds-designated 1–5-were identified whose IC50s in the above-described FRET assay ranged from 29–64 µM but whose average selectively for Myc-Max heterodimers versus Max homodomers was only 2-fold for 4 of the compounds (range 1.7–2.6). The fifth compound was more selective with only 24% inhibition of heterodimer binding being observed at the highest tested concentration (100 µM). The assessment of these compounds in a single osteosarcoma cell line indicated an IC50 for compound 1 of approximately 10 µM without noticeably affecting the growth of PC12 cells. All remaining compounds either inhibited PC12 cells or demonstrated evidence of non-specific toxicity. Further assessment of 1’s activity profile showed it to be comparable to Mycro1 and Mycro2 in EMSA, soft-agar colony and luciferase reporter assays without demonstrating any “off target” effects against fos-jun. Based on the apparent high specificity, the authors suggested that 1 could prove to be a promising scaffold for future drug development.

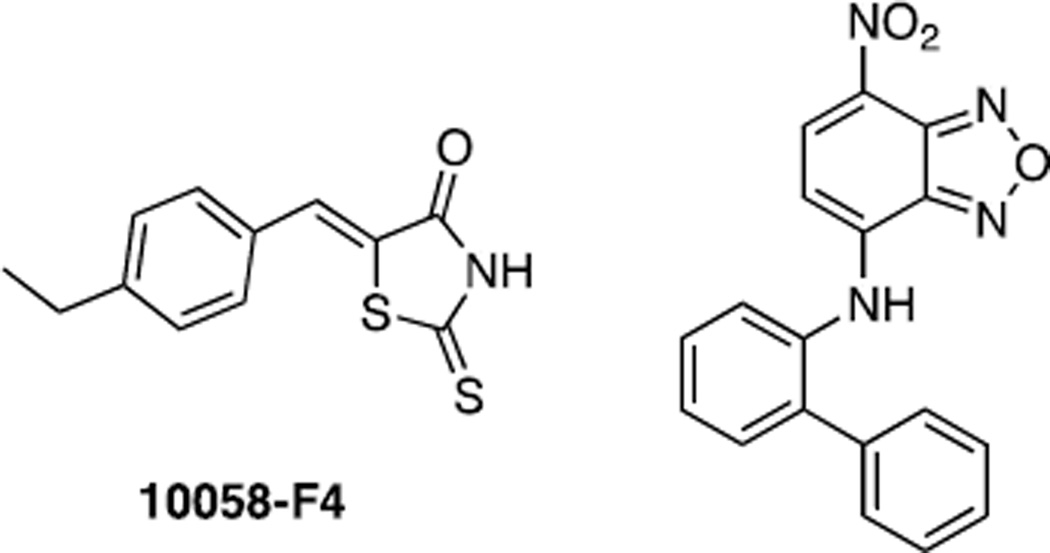

10058-F4 and 10074-G5

Closely following the report by Berg et al (129), Yin et al (130) reported the identification of a distinct set of Myc inhibitors. The approach taken by this group was somewhat different from that used by Berg et al (129) and others and was employed as a way of circumventing the inevitable identification of molecules that, while effective and preventing heterodimerization by purified Myc and Max proteins, would be unlikely chemotherapeutic candidates due to poor cell penetration and/or non-specific toxicity. Yin et (130) al utilized a yeast two-hybrid-based assay in which the bHLH-ZIP domains of Max and Myc were fused to the transcriptional activation domain and the DNA binding domain, respectively, of the yeast Gal4 transcription factor. Functional reconstitution of Myc-Max heterodimers in s. cerevesiae containing a Gal4-responsive β-galactosidase reporter gene strongly induced the expression of the enzyme. This assay also afforded an additional advantage in that any identified hits were likely to be molecules that actually inhibited Myc-Max association and not DNA binding. The yeast strain was then employed in a survey of ~10,000 small molecules that were selected based on 3D pharmacophore analysis to represent a broad spectrum of biologically relevant pharmacophore diversity space. An initial control yeast strain employing similarly constructed expression plasmids for the bHLH-containing partner proteins Id2 and E47 was screened in parallel to identify compounds that were selective for Myc-Max heterodimers. Eventually, seven such compounds were identified, all of which conformed well with Lipinski’s rules (116) and all of which inhibited Myc-Max association by ≥75% and Id2-E47 association by <25% without any significant cellular toxicity. Further specificity was established by testing each of the compounds against 32 additional yeast strains harboring various known bHLH, bZIP and bHLH-ZIP combinatorial protein pairs. Of the 231 possible non-Myc-Max protein pair + drug combinations that were compared in this manner, only 3% showed any significant evidence of “off target” effects. Indeed, three compounds, including two designated 10058-F4 and 10074-G5 (Fig. 4), showed complete specificity for Myc-Max. Interestingly, of the off target effects that were seen with the remaining Myc inhibitors, 42% occurred with combinations of Max and Mad family members whose HLH-ZIP sequences and interactions most closely approximate those between Myc and Max. None of the candidate compounds inhibited Max homodimerization in this assay. Because the initial yeast-based screen also identified compounds that specifically inhibited the control Id2-E47 interaction, but not the Myc-Max interaction, 10 of these compounds were further tested against the entire yeast two-hybrid battery. As was the case for Myc-Max, off target effects were observed in 2.7% of the 330 possible non Id2-E47 interactions with five of the compounds demonstrating absolute specificity against their intended target. These results indicated that yeast two hybrid approaches could be used as simple and robust cell-based assays to identify cell-penetrable and non-toxic compounds capable of disrupting and/or preventing various PPIs with high specificity.

Fig. 4.

Structures of 10058-F4 and 10074-G5

Further analyses of the seven identified Myc compounds provided additional confirmation of their specificity and efficacy. These studies included demonstrating the in vitro disruption of recombinant Myc-Max heterodimers in standard GST-pulldown-type experiments, the specific inhibition of two Myc responsive genes and the lack of inhibition of a gene that is typically responsive to combinations of myogenic HLH proteins. Testing of the Myc-specific compounds in rat fibroblasts showed that cells expressing either endogenous levels of Myc or deregulated levels were highly susceptible to each of the compounds whereas a myc−/− cell line showed a relative lack of response (138). The initial cellular responses consisted of Go/G1 arrest followed by eventual apoptotic death. Transient exposure of the Myc-over-expressing cells to several of the compounds followed by injection into recipient immuno-deficient animals significantly slowed tumor growth.

Subsequent work by this group used computer-assisted searches of >500,00 compounds for molecules with chemical similarity as well as directed synthetic approaches to identify more potent 10058-F4 analogs (139). The approach taken was to search for related compounds whose structures differed from that of 10058-F4 in either the six-member or five-member ring (Fig. 4) and which did not alter the sub-structure by >15%. A total of 63 such compounds were identified which were then prioritized by comparing their IC50s to that of 10058-F4 in a cell-based proliferation assay with HL60 human promyelocytic leukemia cells which over-express Myc due to gene amplification. Of the 48 six-member-substituted analogs, four were found to have IC50s comparable to that of 10058-F4, ranging from 23–51 µM (versus 49 µM for 10058-F4). Of the 15 five-member ring analogs, four were found to be significantly more potent (range 4.6–18 µM). All of the analogs were also able to disrupt Myc-Max heterodimers in HL60 cells as measured by co-IP assays and to promote protein-DNA dissociation in EMSA-based assays. Combining the best attributes of each group so as to generate 17 analogs with both 5- and 6-member “optimized” ring substitutions did not result in any further improvements in cell proliferation assays. In retrospect, these non-additive properties were consistent with the predicted behavior of ID protein regions, which would be capable of binding multiple structures. Thus the conformations best suited to binding a dual five- and six-member ring-substituted analog might be quite different from those which bind either of the singly substituted analogs.

Wang et al (139) next showed that 10058-F4 and all of its most potent analogs bound directly to c-Myc’s bHLH-ZIP domain by employing a fluorescence polarization assay that capitalized on the inherent fluorescent nature of most of these small molecules. They calculated observed affinities for nine of the compounds that ranged from 0.6 to 8.6 times that of 10058-F4 (kobs=2.3 +/− 0.7 µmol/L). The modest correlation between the compounds’ anti-proliferative effects and their binding to Myc and disruption of Myc-Max heterodimers were proposed to be due to factors that affect in cellulo behavior such as uptake, subcellular distribution and intracellular stability.

In a subsequent study by the same group, Follis et al (140) employed a series of deletion and point mutations within the Myc bHLH-ZIP domain to map the precise binding sites for both 10058-F4 and 10074-G5. In the case of 10058-F4, this corresponded to a region spanning the Helix 2-ZIP junction (residues 402–412) whereas for 10074-G5 the binding site mapped to region centered around the N-terminal region of Helix 1 (residues ~363–381). Binding of 10058-F4 was abrogated by several single and double point mutations that included L404P, Q407K and V406A/E409V. Similarly, binding by 10074-G5 was eliminated by point mutations R367G and E369K/L370P. Interestingly, each of these mutations would be predicted to lead to significant charge and/or structure perturbations within their respective binding sites that could easily prevent compound binding.

The above findings were confirmed using synthetic peptides, which encompassed only a single binding site, and by monitoring structural changes using circular dichroism (CD) and 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy. A control, bacterially-expressed peptide corresponding to the entire bHLH-ZIP domain (residues 353–437) was also employed to confirm that any observed changes in the smaller peptides were being recapitulated in the context of the full-length dimerization domain. The CD spectra of this full-length peptide remained essentially unchanged in the presence of 10058-F4 or 10074-G5, demonstrating under both conditions the expected large degree of ID (33) and indicating that any change in structure mediated by small molecule binding must be confined to relatively small regions. In contrast, the CD spectra of both synthetic peptides were markedly altered to more rigid-appearing conformations upon addition of their cognate ligands. In NMR studies, the similar behaviors of the peptides and the full-length bHLH-ZIP domain confirmed that the structural alterations being imposed by the small molecules were geographically localized. A docking simulation performed between the inhibitors and their bound structures showed that in neither case was the peptide conformation representative of that found in the Myc-Max crystal structure (54). Together, these studies indicated that the product of a coupled folding and binding reaction is not necessarily helpful in predicting either potential small molecule binding sites or the conformations these sites will assume. Moreover, the conformations deemed most likely to be occurring in the presence of 10058-F4 and 10074-G5 and their respective binding sites did not appear to be compatible with the formation of the interface needed to associate with Max. Additional analysis of the entire Myc bHLH-ZIP domain with a disorder-predicting program (141) revealed that the two small molecule binding sites each mapped to separate regions associated with abrupt transitions in predicted ID from high to low. It has been proposed that such regions, particularly those that are relatively hydrophobic and non-conserved may be particularly capable of binding small molecules. These properties have also been observed for ID regions involved in partner protein recognition (38).

In follow-up to the above work, Hammoudeh et al (142) examined the remaining compounds originally identified by Yin et al (130) Using the same techniques employed to map the binding sites for 10058-F4 and 10074-G5, they identified a third independent binding site for the compound 10074-A4 immediately C-terminal to and possibly overlapping somewhat with that of the 10074-G5 binding site. The affinity of 10074-A4 for its cognate site in the full-length bHLH-ZIP domain was significantly lower than that for 10058-F4 and 10074-G5 to their sites (21+/−2 µM, vs. 5.3+/−0.7 µM for 10058-F4 and 2.8+/−0.7µM for 10074-G5). All three compounds competing with 10058-F4 bound to the site with at least three-fold less affinity. In contrast, 10050-C10, the only other compound binding to the 10074-G5 site, did so with three-fold higher affinity. CD analysis showed that each compound induced distinctive conformational changes in their respective synthetic peptide binding sites, consistent with the idea that different ligands selected and stabilized distinct structures from the entire ensemble of available ID structures. Although the above-calculated values indicate that the affinities of the small molecules for Myc are rather low, they are nonetheless in the range of the 1 µM Kd reported for Myc-Max heterodimers (121) even before considering the possibility that the binding sites may represent entropically favored points of dimerization initiation.

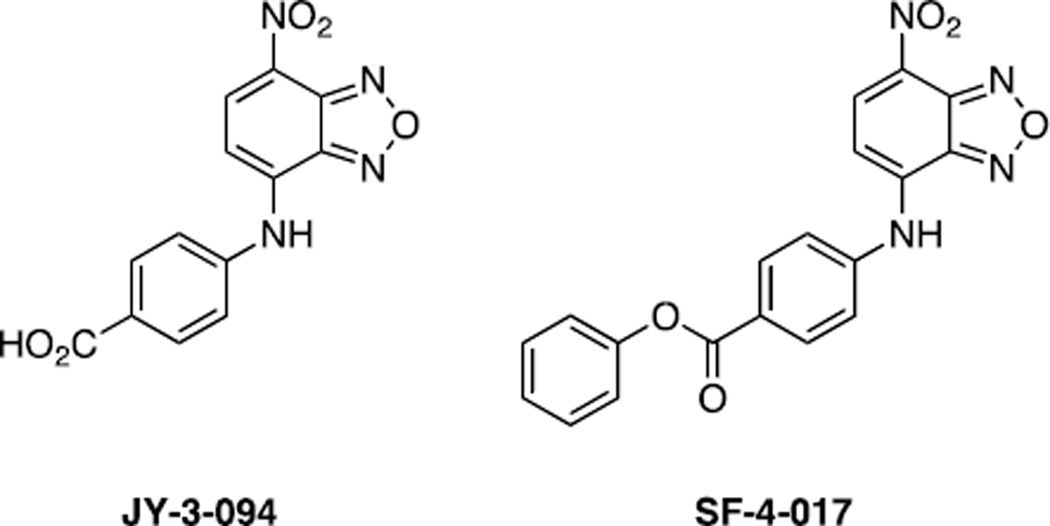

Yap et al (144) conducted a structure–activity relationship analysis of 10074-G5 in which the NMR model of its Myc binding site was used as a guide. The electron-rich nitro group and furazan ring were found to be critical to Myc inhibitory activity, which is consistent with these groups binding the basic residues R366, R367 and R372 as proposed above. In addition, the ortho-biphenyl moiety was also found to be essential and likely due to its occupancy of a hydrophobic domain created by F375 and I381. It was also discovered that the ortho-phenyl ring of the biphenyl could be replaced with a para-carboxylic acid that actually led to enhanced activity relative to the parent compound 10074-G5. This may be due to the resulting compound, JY-3-094 (Fig. 5), engaging in electrostatic interactions with R378. An EMSA assay revealed that JY-3-094 disrupted Myc–Max dimerization with an IC50 value of 33 µM, which is almost five times as potent as 10074-G5 (IC50 = 146 µM). Although JY-3-094 exhibited no cytotoxicity to HL60 and Daudi cells, this was presumably due to its ionizable carboxylic acid. The observed lack of activity of JY-3-094 was remedied by esterification of its carboxylic acid to afford a panel of ester prodrugs that exhibited IC50s in the low micromolar range in both HL60 and Daudi cells (145). LC/MS quantification revealed that the ester pro-drugs were metabolized to the Myc inhibitor JY-3-094 in cells thus confirming that the cytotoxicities, at least in part, stem from JY-3-094. Interestingly, while blockage of the carboxylic acid of JY-3-094 generally led to a loss in Myc inhibitory activity as anticipated through loss of the electrostatic interaction with R378, a phenol ester, SF-4-017 (Fig. 5), proved as potent as JY-3-094 in vitro and a co-IP demonstrated SF-4-017 to be an active inhibitor of Myc–Max dimerization in cells. SF-4-017 represents a new lead Myc inhibitor that should be resistant to both serum and intracellular esterases.

Fig. 5.

Structures of JY-3-094 and SF-4-017.

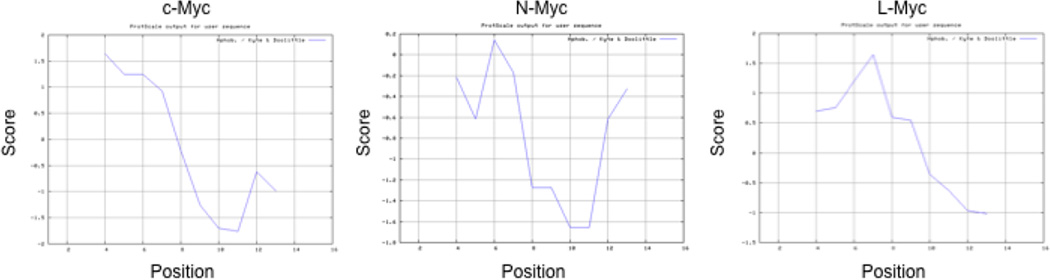

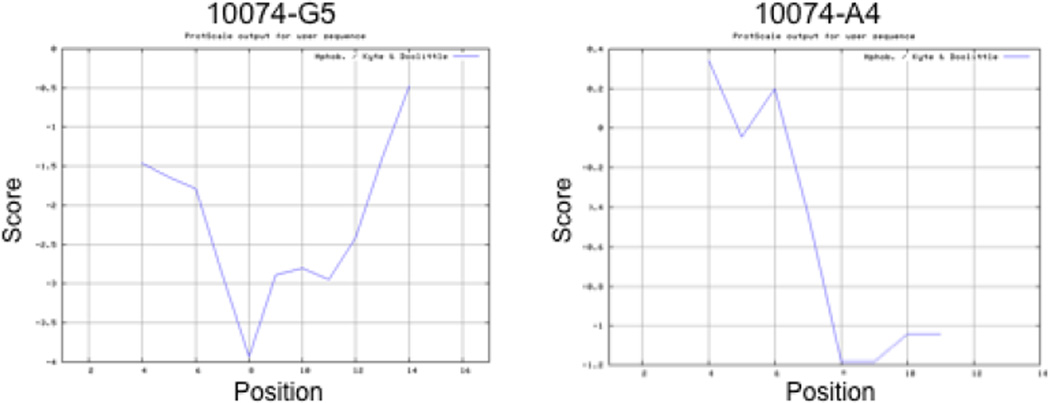

In order to gain more insight into how the Myc402–412 domain interacts 10058-F4, Cuchillo and Michel (146) computed the structures of the binding subset from within the entire conformational ensemble using classical force fields and explicit solvent metadynamics molecular simulations (125,126). Their study revealed a large amount of conformational heterogeneity in both the apo and holo strucures of the peptide. Most importantly, it suggested that rather than there being any single peptide conformation that best represents the interaction with 10058-F4, the small molecule interacts relatively weakly with and stabilizes a large number of conformations. Cuchillo and Michel (146) also found that 10058-F4 made preferential contact with Tyr402, Ile402 and Leu404, which lie within the most hydrophobic segment of the entire bHLH-ZIP domain and define a point of abrupt transition to greater hydrophilicity. In contrast, no such segment was identified in Max. Thus, a simple model would suggest that 10058-F4’s specificity lies in its ability to recognize these points of sharp hydrophobic-hydrophilic transition. This model is consistent with the overall hydrophobicity profiles of the presumptive sites of 10058-F4 binding on N-Myc and L-Myc (Fig. 6) and with recent findings that N-Myc-Max and L-Myc-Max heterodimerization is also susceptible to disruption by 10058-F4 (149 and H. Wang & EVP, unpublished). In fact, this model would also seem to apply in the cases of 10074-G5 and 10074-A4 whose minimal binding sites share the same sharp hydrophobic-hydrophilic transition (Fig. 7). On the other hand, the specificity of 10058-F4 for Myc-Max bHLH-ZIP dimers (130), coupled with its highly Myc-specific gene knockdown profiles (71,149), suggests that this model is over-simplified. This is supported by the finding that the affinity of 10058-F4 for its cognate binding site more than doubles when the minimal peptide binding site (residues 402–412) is extended to include the entire bHLH-ZIP domain (Kd=5.3 µM vs 13 µM) (140). A similar increase in affinity also occurs in the case of 10074-G5 as well (Kd=2.8 µM vs. 4.4 µM) (140). This suggests that the “fine tuning” of site recognition by small molecules, as well as a reinforcement of binding affinity, arises from residues that extend somewhat beyond the minimal binding sites previously defined by synthetic peptides.

Fig. 6.

Kyte-Doolittle hydrophobicity plots for residues 400–415 of Myc and the corresponding residues of N-Myc and L-Myc that are the presumptive sites for 10058-F4 binding. A window setting of 7 was used for all three plots (http://web.expasy.org/protscale/). Note that proteins have regions of comparable hydropbobicity that lie at the N-terminus of the core 10058-F4 binding site and that are associated with abrupt hydrophilic transitions.

Fig. 7.

Kyte-Doolittle plots for Myc binding sites for 10074-G5 (residues 359–375) and 10074-A4 (residues 373–386) (140,142). All settings were identical to those described in Fig. 6. Note the abrupt transitions from relatively hydrophobic sites to hydrophilic sites in both cases.

Two studies to date have confirmed the specificity of 10058-F4 on Myc or N-Myc target genes or their products. In the first, exposure of non-transformed embryonal stem cells to 10058-F4 for a short time (6 hr) was associated with the loss of expression of Myc target genes but not of non-Myc target genes (71). On a more global level, this was also associated with a loss of Pol II Ser2 phosphorylation, which is necessary for transcriptional elongation. In contrast minimal or no effect was seen on Ser5 phosphorylation, which is associated with initiation. Accompanying this finding was the additional observation that 10058-F4 treatment led to a loss of occupancy of Pol II in the actively transcribed bodies of Myc-regulated genes but not at initiation sites. In contrast, non-Myc-transcribed genes show no evidence for Pol II loss at either group of sites. Lending conviction to these results was the finding of similar effects when Myc inhibition was mediated by shRNA knockdown (71). These findings were consistent with the model described above that Myc functions to control transcriptional pausing and release and the read-through of its target genes whose relative sensitivities to Myc are nonetheless varied and complex.

In a related study, Zirath et al (149), compared the proteomic profiles of a human N-Myc-amplified neuroblastoma cell line exposed to 10058-F4 or shN-Myc RNA. Gene ontology analysis showed a common core group of biological processes to be affected by both manipulations most notably those involving mitochondrial structure and function (i.e TCA cycle enzymes and electron transport chain proteins), glycolysis and fatty acid β–oxidation. Roughly half the total genes knocked down as a result of exposure to 10058-F4 an snN-Myc shRNA had been previously reported as being Myc target genes. These findings were particularly notable given the well-documented relationship between both Myc expression, glycolysois and mitochondrial structure and function (150,151). Finally, Zirath et al (149) examined microarry data from 251 primary human neuroblastomas. Expression profiles for 20 transcripts corresponding to the metabolic proteins knocked down by 10058-F4 were available for this data set and 70% correlated positively with N-Myc expression by the tumors and negatively with event-free survival and overall survival.

Holien et al (152) have studied the effect of the compound in multiple myeloma, which typically shows high-level deregulation of Myc for a variety of reasons (152–155). The authors tested 10058-F4 against 6 human myeloma cell lines and 12 patient-derived primary samples, and found that, irrespective of their origin, their responses could be classified as showing either relative sensitivity to the inhibitor (IC50 < 50 µM) or relative resistance (IC50s 50->100 µM). Although the correlation was imperfect, there was a tendency for those lines and primary cells expressing the highest Myc levels to fall within the latter group and, indeed the cells that were the least sensitive to 10058-F4 expressed the highest Myc levels. Holien et al (152) also demonstrated that culturing the cells on a monolayer of bone marrow stromal cells did not alter their sensitivity to 10058-F4 in contrast to IL-6 where such co-cultivation increased IL-6 resistance by 8-fold.

Similarities among direct Myc Inhibitors

Is it possible to say anything about the relationships amongst the direct Myc inhibitors? Other than those reported by Follis et al (140) and Hammoudeh et al (142), no studies have been performed to identify sites on Myc to which these compounds bind or, for that matter, whether they even bind to Myc (although this seems highly likely). However, the study of Hammoudeh et al (142) does suggest some similarities among Myc inhibitors. In addition to identifying the above-described three sites for Myc inhibitors, the investigator also showed that a dual-specific compound, 10019-D3, that disrupted both Myc-Max and Id2-E47 heterodimers (130) also bound to the 10058-F4 site (Myc402–412) with a Kd=11+/=4 µM. Interestingly 10019-D3 contains the same core pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine- 2-carboxamide core structure as Mycro1 and Mycro2, (134). Thus it is likely that Mycro1 and Mycro2 share 10058-F4’s binding site and, quite possibly, may also disrupt the Id2-E47 heterodimer. Taken together, these results suggest that there are only a limited number of binding sites on the Myc bHLH-ZIP domain capable of binding small molecules and preventing is association with Max.

In vivo studies of direct Myc inhibitors

Studies by Guo et al (156) and Claussen et al (157) have described the pharmacokinetics of 10058-F4 and 10074-G5 in mice while also determining their efficacies against human DU145 and PC3 prostate cancer and Burkitt’s lymphoma xenografts, respectively. In the first case, 10058-F4 was found to achieve peak plasma concentrations of ~300 µM following a single i.v. dose of 20 mg/Kg with a terminal half-life of approximately 60 min. Peak tumor concentrations were approximately 10-fold lower and at least eight distinct metabolites were identified. No significant effects on tumor growth were observed. Similarly, 20 mg/Kg of 10074-G5 administered as a single i.v. dose to mice bearing Daudi Burkitt’s lymphoma xenografts showed the compound to reach a peak plasma concentration of 58 µM and to have a plasma half-life of approximately 37 min. As in the case with 10058-F4, peak tumor concentrations were about 10-fold lower than obtained in the serum. As many as 20 metabolites were observed with a number of these appearing to be glucuronide derivatives of hydroxylated or nitro-reduced 10074-G5, thus suggesting that this parental compound is rapidly metabolized by hepatic phase I and phase II enzymes. Taken together, these studies indicated that, while both 10058-F4 and 10074-G5 are well-tolerated, their in vivo efficacy, at least against the tumors tested, were limited due to their rapid metabolism. Continued testing of selected analogs of 10058-F4 and 10074-G5 described above are currently underway

Despite these initial disappointing results, there is some cause for renewed optimism, particularly in the case of 10058-F4. This is based on the recent report of Zirath et al (149) who have shown that this compound, when administered at 20 mg/Kg as a daily ip dose, can double the survival of mice genetically engineered to develop neuroblastoma due to neuroectodermal targeting of N-Myc (158). These results were compatible with the group’s finding that 10058-F4 promotes a dose-dependent dissociation of N-Myc-Max heterodimers that mimics that obtained with Myc-Max. It is also entirely consistent with our own studies indicating that 10058-F4 can disrupt the association between L-Myc and Max and is therefore capable of targeting all Myc family members (H. Wang and EVP, unpublished). Preliminary in vitro studies performed in human neuroblastoma cell lines have indicated that several 10058-F4 analogs are 3–4-fold more potent than 10058-F4 as would have been predicted from the previous findings of Wang et al (139) (M. A. Henriksson and EVP, unpublished). Although we are currently unable to account for these different responses of neuroblastoma and prostate cancer to 10058-F4 (149,156), possible non-mutually exclusive explanations include differential sensitivities of Myc and N-Myc over-expressing cells, strain-specific differential metabolism of the compound or differences in the model systems (i.e. tumor xenografts versus transgenically-driven tumors). Arguing in favor of this latter possibility was the finding that 10058-F4 administration to mice bearing human neuroblastoma xenografts did not significantly affect tumor growth (149). Regardless of the basis, these experiments have revealed for the first time the in vivo efficacy of direct Myc inhibitors. Moreover, the effects appear comparable or even superior to those seen in other model systems with the indirect inhibitor JQ1 (see below).

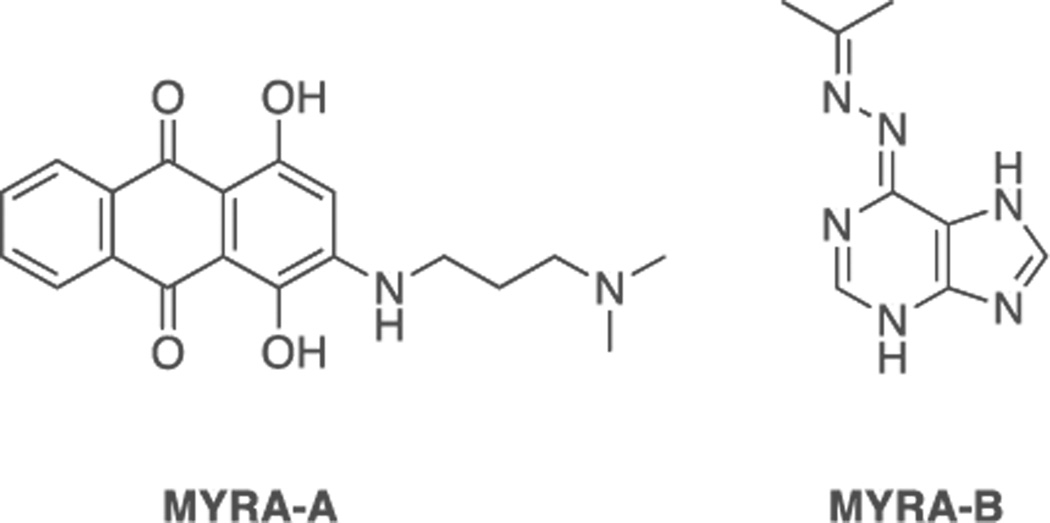

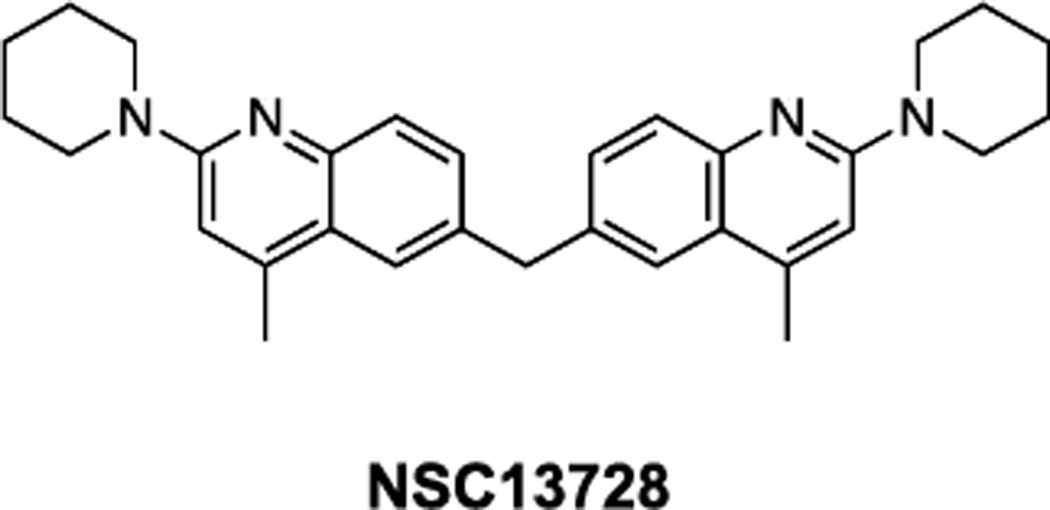

Indirect Myc Inhibitors

Inhibitors of KAc recognition

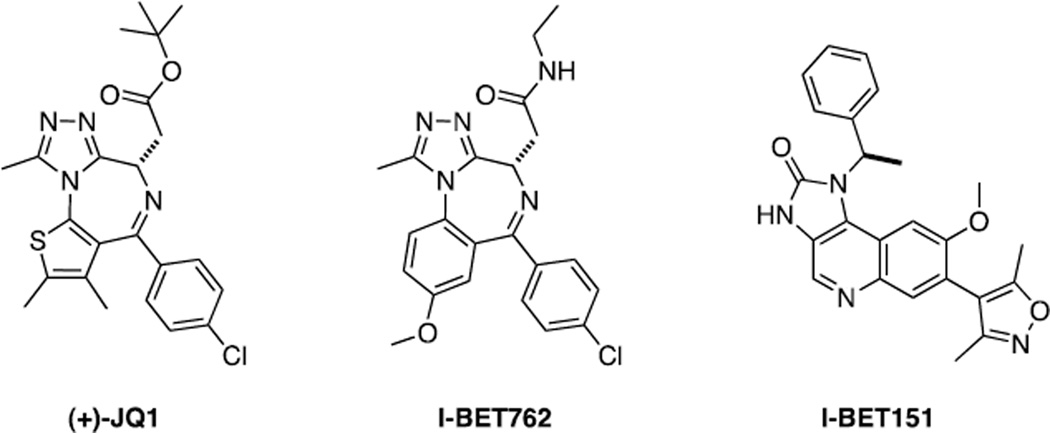

The finding that DNA-bound Myc-Max heterodimers associate with pTEFb and relieve promoter proximal pausing, that this is associated with changes in the histone acetylation profile of bound genes and that KAc side chains are recognized by BET subfamily members (BRD2, BRD3, BRD4 and BRDT) provided reason to suspect that targeting the association between BET proteins and KAc might be a rational way of inhibiting Myc-driven transcription (65,68,71,102,159,160). Indeed a direct role for BRD4 in oncogenic signaling had been previously established by demonstrating its involvement in a highly aggressive and incurable form of squamous cancer known as NUT midline carcinoma in which a t(15;19) chromosomal translocation results in an in-frame fusion between both N-terminal BRD4 bromodomains and the NUT protein (nuclear protein in testis) (102,161,162). Modeling ligand binding within the first bromodomain of BRD4, Filippakopoulos et al (163) and Miyoshi et al (164) developed (+)-JQ1, a thieno-triazolobenzo-1,4-diazepine that binds to the KAc-binding domain of all bromodomains of the BET family but not to the bromodomains of non-BET family members. A key feature of (+)-JQ1 is the 9-methyltriazole ring that functions as a bioisostere of KAc. Importantly, the tert-butyl ester group at C6 was deliberately incorporated to limit the interaction of (+)-JQ1 with other known benzodiazepine-binding proteins. Although (+)-JQ1 is arguably the most studied bromodomain inhibitor, there are now a large number of such compounds in the literature that can be classified based on their KAc mimetics (165). In particular, there are two main KAc mimetic chemotypes: the triazolobenzodiazepines, such as (+)-JQ1 and I-BET762, and the 3,5-dimethylisoxazoles, such as IBET-151 (Fig. 8). It was recently demonstrated that JQ1 displaced BRD4 from acetylated chromatin in cells and that it induced squamous differentiation and cell cycle arrest in a NUT cell line. Moreover, it also dramatically reduced the growth of three NUT xenografts in vivo as well as the growth of a xenograft obtained from newly derived patient material (163). Calculated in vitro IC50s were as low as 4 nM. Moreover, the compound was found to be 49% orally bioavailable.

Fig. 8.

Structures of BET domain inhibitors

Zuber et al (103) extended the above findings in a study that initially set out to identify epigenetic susceptibilities in AML. They used a relatively small (1094 member) doxycline-regulatable shRNA library directed against 243 known chromatin regulators and transduced this as a single pool into a AML cell line driven by MLL-AF9 and NrasG12D. Deep sequencing of the surviving cell population indicated shRNAs directed against BRD4 to be among the most consistently depleted. Zuber et al (103) then asked whether JQ1 might have the same effect and, indeed, found that 13 of 14 AML cell lines were highly susceptible to JQ1 (IC50s ≤500 nM) as were 15 of 18 primary AML samples, including three infant leukemias with MLL gene rearrangements. In all cases, JQ1 treatment led to apoptosis and/or monocytic maturation. Consistent with these findings, gene set enrichment analysis showed that JQ1-treated AML cells markedly up-regulated macrophage-specific genes and down-regulated those for leukemic stem cell marker genes. They also observed a down-regulation of Myc transcripts and protein that in some cases occurred within 60 min of JQ1’s addition, thus suggesting a direct effect. Both BRD4 shRNA expression and JQ1 treatment further down-regulated sets of genes that contained a broadly overlapping subset of known Myc targets. JQ1’s effect on Myc correlated with the loss of a BDR4-enriched chromosomal domain located approximately 2 kb upstream of the Myc transcriptional start site. Interestingly, the expression of ectopic Myc in JQ1-treated AML cells prevented many of the above-described phenotypic changes except for apoptosis. This suggests that even though the primary effect of JQ1 is to block KAc recognition by BRD4, the phenotypes that ensue are largely due to Myc down-regulation. Thus, the various phenotypic consequences of JQ1 treatment appear to require both BRD4 inhibition and Myc down-regulation. As long as Myc expression can be maintained in the face of JQ1 exposure, cells may utilize alternative means of recognizing KAc-tagged chromatin. A prediction of this model is that JQ1 and related agents should be ineffective against tumors driven by N-Myc (i.e neuroblastomas) unless the MYCN locus, like that of MYCC, contains BRD4 binding sites that positively regulates its expression. JQ1 should also be a much less efficient Myc inhibitor when Myc is subject to the control of exogenous promoters that do not harbor BRD4 binding sites such as those associated with some Ig enhancers or papilloma virus sequences. Parenteral JQ1 administration also prolonged the life span of mice bearing MLL-AF9 and NrasG12D AML xenografts although the increase in survival was <50% (103).

A subsequent study by Mertz et al (166) confirmed the sensitivity of most AML cell lines to JQ1 and extended the efficacy profile to multiple myeloma, which tends to be quite dependent on deregulated Myc over-expression (4,153,155). 14 of 15 myeloma cell lines were growth inhibited at JQ1 concentrations ranging from 100–500 nM. Gene expression arrays were performed in a Burkitt lymphoma and myeloma line after only several hours of exposure to JQ1 in order to demonstrate the earliest and most direct targets. Importantly, in control studies the transcriptional response to the inactive enantiomer of JQ1 was minimal, thus emphasizing the importance of KAc-binding by the active molecule. In contrast, treatment with the latter molecule was associated with the down regulation of a large number of genes that had been previously demonstrated to be E-box-containing Myc targets. The authors confirmed the findings of Zuber et al (103) that Myc down-regulation is a primary mediator of JQ1’s effects. Administration of JQ1 to animals bearing Burkitt lyphoma xenografts significantly slowed tumor growth rates and survival although, as had been previously seen by Zuber et al (103), the latter was extended by only about 50%. Somewhat more encouraging were the results of a tumor xenograft study using an AML cell line that had proven to be the most sensitive to JQ1 in in vitro experiments. Here, and at the optimal dose and timing employed, tumor xenografts essentially remained quiescent during the JQ1 treatment period. Although survival studies were not provided, it appears that the inhibition of tumor growth was of sufficient magnitude so as to profoundly affect animal longevity. These studies suggest that a minority of AML cells lines (and perhaps primary tumors as well) may be disproportionately susceptible to BET inhibitors. Finally, these authors also examined the response of N-Myc to JQ1 in a single MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma cell line. Consistent with the idea posited above that the N-Myc promoter may not contain BRD4-enriched sites, N-Myc transcript levels were reduced by only 50–60% versus the more typical >90% down-regulation observed in Myc-dependent tumors.

In parallel with the studies reported by Mertz et al. (166), Delmore et al (167) also examined the effects of JQ1 on multiple myeloma and provided additional evidence to potentially explain the disproportionate sensitivity to BRD4 inhibition in this disease. First, they found that BRD4 expression positively correlated with disease progression and that the BRD4 locus is frequently amplified. In at least one cell line, up-regulation of BRD4 was seen upon co-culturing the cells with bone marrow stromal cells suggesting that this higher level expression might be involved in imparting the characteristic osteotrophic behavior of multiple myeloma in the context of the bone marrow microenvironment. They then used global transcriptional profiling and unbiased gene set enrichment analysis to define the consequences of JQ1-mediated BET inhibition in three cell lines in which Myc was dysregulated by different mechanisms. In all cases, JQ1 mediated a selective effect on Myc-regulated gene expression as well a down-regulation of Myc itself. Known Myc-dependent biological modules such as ribosomal biogenesis and glycolysis, were also significantly down-regulated by JQ1. Moreover, and in a variation on the theme described Zuber et al (103), JQ1 treatment led to a loss of BRD4 concentrated on Ig enhancers in close proximity to translocated MYCC target genes as well as at transcriptional start sites. Additionally, 23 of 25 myeloma cell lines demonstrated high sensitivities to JQ1, (IC50s 68–500 nM) that was little changed when the cells were propagated in bone marrow stromal cells, which is known to confer resistance to diverse chemotherapeutic agent. (154,168). Three of five primary patient-acquired MM samples also underwent apoptosis with IC50s ranging from 400–800 nM. Finally, JQ1 was tested in several myeloma xenografts where, in addition to slowing tumor growth (based on bioluminescent imaging), it also reduced the abundance of serum M protein. However, the mean prolongation of survival between untreated and treated groups, while statistically significant, was only about 60% (ca. 22 days vs. 36 days).

Ott et al (169) extended the above findings to examples of pre-B ALL, the most common hematologic malignancy of childhood. An examination of 9 pre-B ALL cell lines with diverse chromosomal aberration showed all to be quite sensitive to JQ1 with some exquisitely so (ranges of IC50s=31–263 nM. In contrast to AML where JQ1 treatment led to a cell cycle arrest followed by eventual apoptosis, treated ALL cells experienced a more rapid onset of apoptosis and a more delayed and attenuated cell cycle arrest. As previously seen in AML cases, JQ1 treatment produced a rapid displacement of BRD4 from the MYCC promoter and the down-regulation of Myc RNA and protein. An examination of 32 validated Myc target genes showed most to be significantly down-regulated after as little as 4 hr of exposure to JQ1.

Two of most sensitive cell lines in the study by Ott et al (169) harbored translocations between the CRLF4 gene and the IgH region. CRLF4-IL7R heterodimers normally respond to thymic stromal lymphopoietin via activation of the JAK-Stat pathway and mutations along this entire pathway are not only relatively frequent in pediatric ALL but in some cases identify a particularly high-risk group (170). By analogy to multiple myeloma, where Myc down-regulation in response to JQ1 treatment can be traced to a loss of BRD4 binding to the IgH enhancer (167), Ott et al (169) failed to find similar sites in the translocated CRLF4 gene. However, they did find the IL7R gene promoter to be bound by BRD4, which was displaced after a relatively short period of exposure to JQ1 leading to a marked decline in IL7R cell surface protein. As expected, this effect was entirely unrelated to the status of the CRLF4 gene as it was seen in several cell lines with CRL4 rearrangements. These findings have important implications for future JQ1-directed therapies as they suggest that the responses of tumors (or lack thereof) may be highly contextual in nature and significantly determined by BRD4-dependent genes other than MYCC.

The full molecular consequences of IL7R role as a JQ1 target were more fully appreciated upon genome-wide expression profiling. This revealed that a series of genes containing Myc binding sites as well as a second set containing Stat5 binding sites were down-regulated in response to JQ1. In contrast, genes harboring NF-κB sites remained largely unaffected, thus attesting to JQ1’s specificity. Finally, in an elegant xenograft model that involved primary pre-B ALL cells with a P2RY5-IL7R translocation and no other mutations along the CRLF4-IL7R pathway, treatment with JQ1 for five days resulted in a marked reduction in phospho-Stat5 and decreases in both MYC and IL7R transcripts, with no significant changes in CRLF2 expression. Unfortunately, while JQ1 treatment normalized peripheral blood counts, it did not lead to a remission and treated mice experienced only a ca. 30% prolongation in survival. A likely explanation for this sub-optimal response was provided by an examination of splenic tissues from the JQ1-treated animals, which showed high level expression of both Myc and phospho-Stat5. Because only this single in vivo example was reported, it is not clear whether it represents the ultimate fate of other treated cases of ALL. Very clearly however, it provided the first evidence for the development of JQ1 resistance occurring via a “predictable” mechanism.

Very recently, Segura et (171) al have studied the effect of BRD4 inhibition in melanoma, a disease in which approximately 50% of advanced stage tumors are associated with B-Raf point mutations (typically V300E) that portend a highly unfavorable prognosis (172). A microarray analysis of 22 melanoma cell lines and 44 primary tumors showed a significantly elevated expression of Brd4 in tumors relative to that detected in either immortalized melanocytes or benign nevi. Moreover, although there was considerable overlap between transformed and benign samples, none of the latter showed levels of BRD4 expression higher than the mean of the former. A similar pattern was observed for BRD2. Approximately half the cell lines examined also showed evidence for BRD4 or BRD2 gene amplification (typically 2.5–4-fold). Two JQ1-related BRD4 inhibitors, MS417 and MS436, were next tested against 2 melanoma cells lines in which they promoted G0/G1 arrest and differentiation without apparent regard for B-Raf status. These results were confirmed by studies demonstrating that siRNA or shRNA-mediated suppression of BRD4, but not BRD2 or BRD3, were associated with significant cytostatic effect and loss of colony-forming ability in vitro and that the xenografts from the latter cells were smaller and had reduced Ki67 staining. Consistent with these findings, MS417 treatment of animals bearing melanoma xenografts led to a ca. 4-fold reduction in total tumor burden and reduced metastatic dissemination, although survival results were not presented. Transcriptional profiling performed on 3 melanoma cell lines prior to and after treatment with MS436 showed the expected downregulation of Myc RNA and protein and up-regulation of the negative cell cycle regulators and negative Myc targets p21CIP1 and p27KIP. Although gene ontology analysis indicated the most frequently affected genes were those involving cell cycle regulation, vascular development and chromatin assembly, it was not clear whether these were actual Myc targets.

Interestingly, the results in melanoma cells reported by Segura et al (171) showed wide variations in their sensitivities to MS417 and MS436. Moreover, MS417, which was the more potent, demonstrated the submicromolar IC50s typical for JQ1 (103,166,167) in only 3 of 7 tested cell lines and the IC50s for MS436 ranged from approximately 7–62 µM. Whether these disparities reflect a relative resistance of melanomas to BRD4 inhibitors in general or simply to these particular compounds remains to be determined.

Lack of response to JQ1

Despite their impressive effects against certain tumor types, there appear to be numerous cancer cell lines that are unaffected by or only partially responsive to BRD4 inhibitors. These include numerous ALLs, breast cancer, melanomas, osteosarcomas, and cervical adenocarcinomas (103,166). Although the reasons for such resistance have not been thoroughly explored, several explanations are possible. First, given the important role played by Myc down-regulation in response to JQ1, it is possible that that BRD4 binding locus in the MYCC gene promoter may simply not be as important in regulating gene transcription as it is more susceptible cells. It is also possible that some tumors are less reliant on BRD4 for the “reading” of epigenetic tags or on Myc itself for providing the scaffolding that supports transcriptional regulation.

Despite the initial excitement surrounding the initial identification of BET domain inhibitors as a potential treatment for Myc-driven cancers, considerable work remains. First, the tumor responses to these agents, while significant, have tended to be relatively minor (generally a <50% prolongation in survival and/or disease progression in experimental xenografts). To a large extent, this may reflect the current lack of in vivo optimization of these compounds. For example, the serum half-life of JQ1 is only about one hr, i.e comparable to that of 10058-F4 (103,156) and it remains unknown how well the compound penetrates tumors. It seems likely that medicinal chemistry-based approaches will be successful in increasing both the in vivo potencies and half-lives of new analogs.

Synthetic lethal Myc inhibitors

The basis of synthetic lethal interactions