Abstract

Background:

Asthma is a common chronic inflammatory disease of the bronchial airways. Well defined treatment options for asthma are very few. The role of vitamin D3 on asthma is still baffling. Aim: We have examined the effect of vitamin D3 supplementation in mild to moderate persistent asthma patients.

Materials and Methods:

We conducted an open labeled, randomized comparative trial in 48 asthma patients. The study duration was about 90 days. The study had a run-in-period of 2 weeks. At the end of run-in-period, patients were divided into two groups: Usual care group (n = 31) patients received budesonide and formoterol and intervention care group (n = 32) patients received vitamin D3 supplementation along with their regular medicine.

Results:

The primary outcome of the study was to measure the improvement in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1). Patients in both groups had a significant improvement in FEV1 at the end of the study. The mean difference in percentage predicted FEV1 in usual care and intervention care group was 4.95 and 7.07 respectively.

Conclusion:

The study concluded that adjunctive therapy of vitamin D3 is effective in asthma patients. The present study will be an evidence based report; however, future studies are warranted in longer duration of time to substantiate the present findings.

Keywords: Asthma, budesonide, forced expiratory volume in 1 s, formoterol, vitamin D3

INTRODUCTION

Asthma is a common chronic lung disease affecting 300 million people and its prevalence increases globally by 50% every decade.[1] In recent days, there are more numbers of reports of the association between vitamin D deficiency and a widespread range of conditions such as cancer, depression, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, multiple sclerosis, osteoporosis, fertility, asthma etc.[2,3] Thus, vitamin D3 has brought an incredible amount of attention towards health care professionals. Since inflammation is a key component in the pathophysiology of asthma, anti-inflammatory drugs especially corticosteroids are typically prescribed. Vitamin D was also found to be anti-inflammatory in many tissues and lung tissue also one among. Vitamin D significantly decreases regulated on activation, normal T cells expressed and secreted (a proinflammatory molecule that attracts monocytes, T cells and eosinophils) and IP-10 (a proinflammatory mediator that recruits activated T cells, mast cells and natural killer cells).[4]

Despite a day-to-day foods are fortified with vitamin D, many studies have shown an absolute deficiency of vitamin D in many people. Vitamin D deficiency leads to increased bronchial hyper responsiveness and reduced pulmonary function.[5] Nearly, 5-15% of patients with asthma symptoms and exacerbation are uncontrolled despite of routine controller medications including corticosteroids. Therefore, they are more prone to have irreversible obstruction of airflow and also associated with airway remodeling.[6,7] If vitamin D plays either preventive or protective role against the development of asthma, then it could be the most effective therapy.

Very few studies[8,9] have considered this point and evaluated the relationship between vitamin D3 and pulmonary function and there is no clinical study report from Indian adult population to explore the role of vitamin D3 in asthma. Thus, the present study was undertaken to study whether or not vitamin D3 can improve pulmonary function in mild to moderate persistent asthma patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study protocol and recruitment

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee (330/IEC/2012) and it was undertaken in Pulmonary Medicine department in SRM Medical College hospital and research center, Kattankulathur, Tamil Nadu, India. The study was conducted according to the International Conference for Harmonization good clinical practice guidelines, 2008 amendment. This is a randomized, open-labeled, pilot study. A total of 63 patients completed the study. Patients were aged between 35 and 65 years, either sex, without co-morbidities and mild to moderate persistent condition were included in the study. Patient with a history of cardiac disorders, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pregnant women and lactating mothers, significant hepatic and renal dysfunction, intolerance to vitamin D supplementation and voluntary withdrawal were excluded from the study. Written consent was obtained from all the patients.

Study design

Patients satisfying above study criteria were enrolled in the study. Enrolled patients were randomized by randomization chart generated by computer assisted random allocation procedure. Patients were divided into two groups namely usual care (n = 31) and intervention care (n = 32) groups. Clinical information relevant for the study was collected from the patients, health-care professionals, necessary records and as well as from patient's bystanders in few cases. Anti-asthmatic drugs prescribed until date were stopped and the patients were asked to take salbutamol inhaler (i.e., rescue medication) whenever necessary for a 7-day (run-in period) prior to the study. Patients were educated and counseled about the proper usage of inhalers. Usual care group patients received budesonide 400 µg with formoterol 24 µg daily. This is the fixed dose combination (FDC). One puff contained 200 µg budesonide and 6 µg formoterol. Patients had taken two puffs morning and two puffs night. Intervention care group patients received the same FDC plus vitamin D3 tablet (1000 IU). All patients could take short acting β-agonist in case of an asthmatic crisis. All the patient's clinical symptoms and pulmonary function (forced expiratory volume in 1 s [FEV1] by spirometry) were measured at baseline and every follow-up days, i.e., day 30, 60 and 90. Each and every follow-up, patient medication adherence and their inhaler usage technique were monitored.

Statistical analysis

A sample size of not less than 30 was considered for this pilot study. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation The P < 0.05 was considered for statistical significance. Demographic characteristics such as age and gender, baseline and final visit data were used to assess response rates by comparing usual care and intervention group. Student's t test was used for the comparisons within the groups. One-way analysis of variance Bonferroni multiple comparison test was used for comparisons between groups using Graph Pad Software, Inc., (USA). Per protocol analysis has performed.

RESULTS

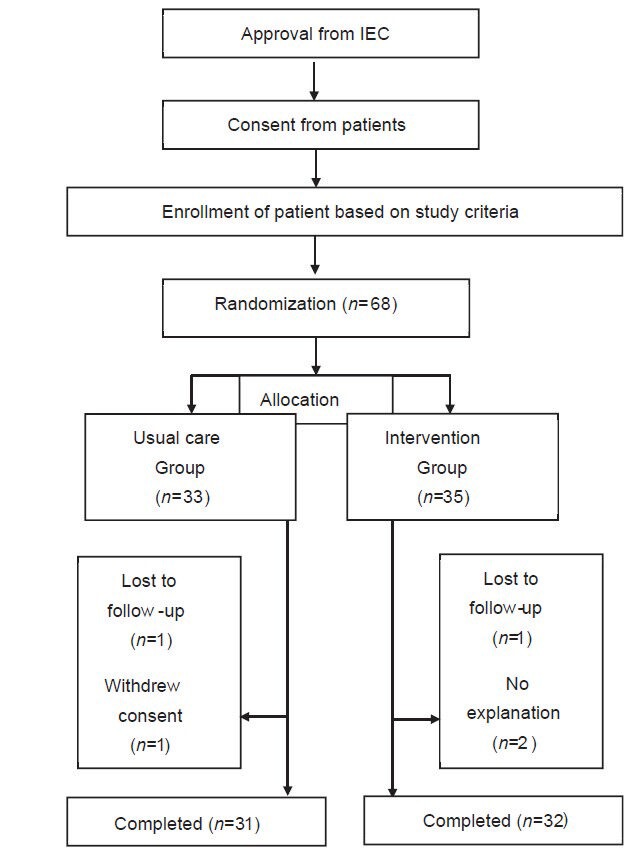

A total of 90 patients attended the screening phase for mild to moderate asthma condition, out of which 68 patients met the study criteria. Patients who got enrolled after giving informed consent were randomized into two groups. In the usual care group, out of 33 patients, 31 patients completed the study and in the intervention care group, out of 35 patients, 32 patients completed the study. Reasons for drop out in both groups were mentioned in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow of patients and CONSORT Diagram

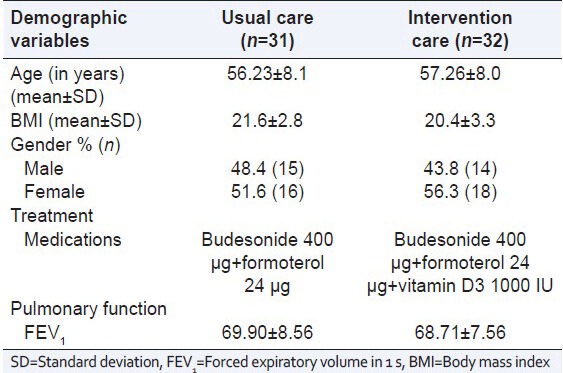

In the usual care group, out of 31 patients, 15 patients were male and 16 patients were female and their mean age was 56.23 ± 8.1 years, mean body mass index (BMI) was 21.6 ± 2.8. Out of 32 patients in intervention care group, 14 patients were male and 18 were female and their mean age was 57.26 ± 8.0 years, mean BMI was 20.4 ± 3.3. No significant difference was observed in age, BMI and gender distribution between the study groups [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic data of the patients

In the usual care group, 22.6% (n = 7) and in the intervention group, 25% (n = 8) patients were found as coolies. In both groups, 16.1% and 12.5% patients were employed and 16.1% and 15.6% were self-employed respectively. There was no patient in both groups were professional workers. Patients in others category included housewives in both groups. The educational status of the patients was also shown in Table 1. 16.1% (n = 5) patient with usual care and 21.9% (n = 7) patients in intervention care group were illiterate. 13 and 14 patients (41.9% and 43.8%) in usual and intervention care group studied between 1st and 10th standard. 38.7% (n = 12) and 34.4% (n = 11) in usual and intervention care group patients had an 11th standard to a degree education. No patient in intervention care and 3.2% (n = 1) in the usual care group had post-graduation qualification.

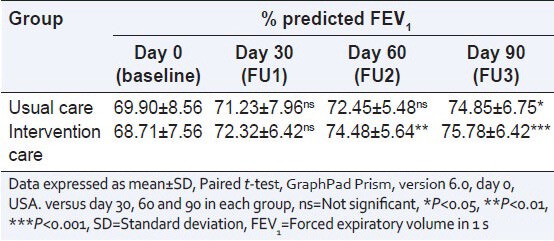

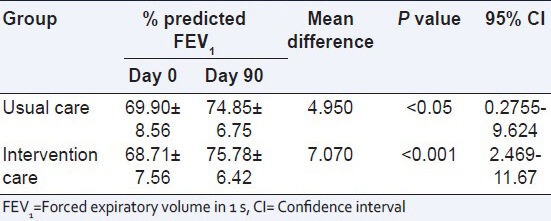

The changes in the percentage FEV1 values from baseline (day 0) to end of the study (day 90) in both groups are shown in Table 2. It is evident from the table that FEV1 values are improved at every follow-up in both groups. The percentage improvement in FEV1 from baseline to end visit between the groups were shown in Table 3. For the usual care group patients, the mean difference was 4.95 with the confidence interval (CI) of 0.2755-9.624. There was significant (P < 0.05) improvement in percentage predicted FEV1. Intervention group patients, the mean difference were 7.07 with the CI of 2.469-11.67. Significant (P < 0.001) improvement in percentage predicted FEV1 after 90 days treatment was observed in the intervention groups. There is no statistically significance were observed between the groups.

Table 2.

Visit wise changes in % predicted FEV1 between the groups

Table 3.

Comparison of % FEV1 between day 0 and 90 among the study groups

Physical examination including oropharyngeal inspection, heart rate and blood pressure were monitored for study patients. There were no significant changes in such assessments recorded in all the clinical visits compared with baseline values (data are not shown). Asthma exacerbations, which required hospitalization, were considered as serious adverse events. There was no such critical situation faced by study patients of both groups.

DISCUSSION

Pharmacotherapy is essential for asthma management and is based on stepwise treatment for different levels of asthma severity: Intermittent, mild persistent, moderate persistent and severe persistent. Antiasthma drugs are classified into the controller and preventive medications. Among the controller medications, an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) is the mainstay and the use of ICS is considered as one of the best treatment options for patients with mild to moderate asthma condition.[10] However, not all the patients achieve the asthma treatment goal with corticosteroid, because, asthma is a multi-factorial disease where inflammation alone is not playing the role. The pathophysiology of asthma is complicated. Recent data indicate that current pharmacotherapy for asthma is inadequate to control asthma.[11] Therefore, there is a need to identify the cause of asthma and treatment should be aimed at the identified risk.

Studies carried out in an animal model reported that vitamin D3 pre-treated groups enhanced the efficacy of allergen immunotherapy in a mouse allergic asthma model.[12] Bergman et al.,[13] 2012 studied the effect of vitamin D3 supplementation to reduce the disease burden in patients with frequent respiratory tract infection. They evidenced their report from both per protocol analysis and intention-to-treat models.

Gergen et al., 2013[9] examined the relationship between serum vitamin D3 levels and allergic diseases. They found that higher the serum vitamin D3 concentration, lower in total IgE levels and peripheral eosinophil counts. Black and Scragg[14] also revealed a strong relationship between serum concentration of vitamin D3 and pulmonary function parameters like FEV1 and forced vital capacity.

Iqbal and Freishtat 2011[15] analyzed the various factors and the role of vitamin D3 in asthma. They concluded that vitamin D3 acts on lung tissue and to improve immune function and reduce inflammation. However, they did not give any ample evidence that vitamin D3 has the potential to improve pulmonary function. Studies carried out in pediatric population[16] also not reported any definitive proof of improved clinical symptoms of asthma with the adjunctive therapy of vitamin D3. Recently Gergen et al., 2013[9] studied the relationship between serum vitamin D3 concentration and prevalence of asthma with severity and response of asthma treatment. The study concluded that overall vitamin D3 concentrations were low in two samples of adolescents and they were not reliably linked with the presence of asthma or asthma morbidity.

From the above contradictory statement, we could not come to a conclusion whether vitamin D3 has a role on asthma condition or not. Thus, the present study was undertaken and the study was designed as open-labeled, randomized trial.

Dupont et al. 2005[17] observed an improvement in pulmonary function and asthma symptoms with add-on leukotriene receptor antagonist therapy, for a period of 2 months in an open- labeled study with insufficiently controlled asthma patients with ICS and long-acting β2 agonists as FDC. Shah et al., 2006; Korn et al., 2009; Keith et al., 2009[18,19,20] studied the effectiveness of controller medications as add on therapy to ICS, in improving lung functions and asthma symptoms. All these studies were carried out for a period of 8 weeks. With this background, a period of 90 days study duration in the present study was relatively considered to be sufficient to identify the effectiveness of study medications along with vitamin D3 supplementation. However, this may be the limitation of this study, since the present study could not measure the asthma exacerbations in the long-term control. The study is designed as an open-label study. This may be another weakness of the study, but in routine clinical practice, blinding of the drug is not appropriate and the data obtained are suitable to real life setting.

The present study did not measure the level of vitamin D3 in the blood. This is the major limitation of the study. Future studies can be directed towards this direction. Nevertheless, our study has some special features. For instance, we gave 1000 IU vitamin D3 as a daily dose. Other studies used lower doses of vitamin D3[21,22,23,24] and importantly, there are no clinical data on mild to moderate persistent asthma patients especially from the south Indian population. Thus, supplementation of vitamin D3 in asthma is an innovative tactic in improving pulmonary function.

The finding of this suggests that the addition of vitamin D3 to the regular treatment regimen improves pulmonary function. In recent days, an important talk and task among the researchers is to find the exact mechanism through which vitamin D3 exerts its pharmacological action on bronchial airways. However it is very complicated to retort the above. Vitamin D3 acts on numerous ways to control asthma[25,26,27,28] and the important ways are: It inhibits bronchial smooth muscle cell proliferation and remodeling and thereby, inhibits the synthesis and release of cytokines. Vitamin D3 acts on mast cells and inhibits the differentiation and maturation of mast cells and down-regulate the expression of CD4+ and CD8+ cells to allergic airways. Vitamin D3 enhances interleukin-10 and transforming growth factor-β synthesis by acting on dentric and regulatory cells respectively.

In the present randomized, open-labeled study there is an evidence for improvement in pulmonary function clinically as well as statistically on supplementation of vitamin D3. If the dietary intake of vitamin D fails to meet the recommended daily allowance, health-care professionals may encourage the asthma people to increase their intake of vitamin D, preferably through the consumption of healthy food sources rich in vitamin D or otherwise through the use of appropriate vitamin supplements. However, considering an open-label design, future studies may be directed toward longer duration followed by serum estimation of serum 25-hydroxy vitamin D to substantiate the current findings.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rajanandh MG, Nageswari AD, Ilango K. Influence of demographic status on pulmonary function, quality of life and symptom scores in patients with mild to moderate persistent asthma. J Exp Clin Med. 2014;6:102–4. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pauwels RA, Pedersen S, Busse WW, Tan WC, Chen YZ, Ohlsson SV, et al. Early intervention with budesonide in mild persistent asthma: A randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet. 2003;361:1071–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12891-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holgate ST, Polosa R. The mechanisms, diagnosis, and management of severe asthma in adults. Lancet. 2006;368:780–93. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69288-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alyasin S, Momen T, Kashef S, Alipour A, Amin R. The relationship between serum 25 hydroxy vitamin d levels and asthma in children. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2011;3:251–5. doi: 10.4168/aair.2011.3.4.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Viswanathan R, Prasad M, Thakur AK, Sinha SP, Prakash N, Mody RK, et al. Epidemiology of asthma in an urban population. A random morbidity survey. J Indian Med Assoc. 1966;46:480–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banerjee A, Damera G, Bhandare R, Gu S, Lopez-Boado Y, Panettieri R, Jr, et al. Vitamin D and glucocorticoids differentially modulate chemokine expression in human airway smooth muscle cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;155:84–92. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clifford RL, Knox AJ. Vitamin D-A new treatment for airway remodelling in asthma? Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158:1426–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00429.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Urry Z, Chambers ES, Xystrakis E, Dimeloe S, Richards DF, Gabryšová L, et al. The role of 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and cytokines in the promotion of distinct Foxp3+ and IL-10+ CD4+ T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42:2697–708. doi: 10.1002/eji.201242370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gergen PJ, Teach SJ, Mitchell HE, Freishtat RF, Calatroni A, Matsui E, et al. Lack of a relation between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations and asthma in adolescents. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97:1228–34. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.046961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jenkins CR, Thien FC, Wheatley JR, Reddel HK. Traditional and patient-centred outcomes with three classes of asthma medication. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:36–44. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00144704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel YA, Patel P, Bavadia H, Dave J, Tripathi CB. A randomized, open labeled, comparative study to assess the efficacy and safety of controller medications as add on to inhaled corticosteroid and long-acting β2 agonist in the treatment of moderate-to-severe persistent asthma. J Postgrad Med. 2010;56:270–4. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.70937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma JX, Xia JB, Cheng XM, Wang CZ. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 pretreatment enhances the efficacy of allergen immunotherapy in a mouse allergic asthma model. Chin Med J (Engl) 2010;123:3591–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bergman P, Norlin AC, Hansen S, Rekha RS, Agerberth B, Björkhem-Bergman L, et al. Vitamin D 3 supplementation in patients with frequent respiratory tract infections: A randomised and double-blind intervention study. BMJ Open. 2012;2:1–10. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Black PN, Scragg R. Relationship between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin d and pulmonary function in the third national health and nutrition examination survey. Chest. 2005;128:3792–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.6.3792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iqbal SF, Freishtat RJ. Mechanism of action of vitamin D in the asthmatic lung. J Investig Med. 2011;59:1200–2. doi: 10.231/JIM.0b013e31823279f0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanson C, Armas L, Lyden E, Anderson-Berry A. Vitamin D status and associations in newborn formula-fed infants during initial hospitalization. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111:1836–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dupont L, Potvin E, Korn D, Lachman A, Dramaix M, Gusman J, et al. Improving `asthma control in patients suboptimally controlled on inhaled steroids and long-acting beta2-agonists: Addition of montelukast in an open-label pilot study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21:863–9. doi: 10.1185/030079905X46304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shah AR, Sharples LD, Solanki RN, Shah KV. Double-blind, randomised, controlled trial assessing controller medications in asthma. Respiration. 2006;73:449–56. doi: 10.1159/000090898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Korn D, Van den Brande P, Potvin E, Dramaix M, Herbots E, Peché R. Efficacy of add-on montelukast in patients with non-controlled asthma: A Belgian open-label study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25:489–97. doi: 10.1185/03007990802667937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keith PK, Koch C, Djandji M, Bouchard J, Psaradellis E, Sampalis JS, et al. Montelukast as add-on therapy with inhaled corticosteroids alone or inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting beta-2-agonists in the management of patients diagnosed with asthma and concurrent allergic rhinitis (the RADAR trial) Can Respir J. 2009;16(Suppl A):17A–31. doi: 10.1155/2009/145071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luong Kv, Nguyen LT. The role of vitamin D in asthma. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2012;25:137–43. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song Y, Qi H, Wu C. Effect of 1,25-(OH) 2D3 (a vitamin D analogue) on passively sensitized human airway smooth muscle cells. Respirology. 2007;12:486–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2007.01099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taher YA, van Esch BC, Hofman GA, Henricks PA, van Oosterhout AJ. 1alpha, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 potentiates the beneficial effects of allergen immunotherapy in a mouse model of allergic asthma: Role for IL-10 and TGF-beta. J Immunol. 2008;180:5211–21. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wjst M, Altmüller J, Faus-Kessler T, Braig C, Bahnweg M, André E. Asthma families show transmission disequilibrium of gene variants in the vitamin D metabolism and signalling pathway. Respir Res. 2006;7:60. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xia JB, Wang CZ, Ma JX, An XJ. Immunoregulatory role of 1, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3)-treated dendritic cells in allergic airway inflammation. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2009;89:514–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hansdottir S, Monick MM. Vitamin D effects on lung immunity and respiratory diseases. Vitam Horm. 2011;86:217–37. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-386960-9.00009-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pfeffer PE, Hawrylowicz CM. Vitamin D and lung disease. Thorax. 2012;67:1018–20. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandhu MS, Casale TB. The role of vitamin D in asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;105:191–9. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]