Abstract

Background

Prostate cancer (PCa) bone metastasis can be markedly enhanced by increased receptor activator of NF kappa-B ligand (RANKL) expression in PCa cells. Molecular mechanisms that account for the increased predilection of PCa for bone include increased bone turnover, promotion of PCa cell growth and survival in the bone environment, and recruitment of bystander dormant cells to participate in bone metastasis. The current study tests the hypothesis that PCa cells acquire high adhesion to bone matrix proteins, which controls PCa bone colonization, under the RANKL/RANK and AR axes.

Methods

We used a highly bone metastatic RANKL-overexpressing LNCaP PCa cell line, LNCaPRANKL, as a model to pursue the molecular mechanisms underlying the increased adhesion of PCa cells to collagens. A three-dimensional (3-D) suspension PCa organoid model was developed. The functions of integrin α2 in cell adhesion and survival were evaluated by flow cytometry and western blot. AR expression and functionality were compared in 2-D monolayer versus 3-D suspension cultures using AR promoter- and PSA promoter-luciferase activity. AR role in cell adhesion was assessed using an adhesion assay.

Results

LNCaPRANKL cells were shown to adhere tightly to ColI matrix through increased α2 integrin expression. This increased adhesion, concomitant with activation of the FAK and Akt pathways, was further enhanced by culturing LNCaPRANKL cells in 3-D suspension. Under the influence of 3-D suspension culture, AR was restored in LNCaPRANKL cells via downregulation of AP-4 transcription factor, and supported increased α2 integrin expression and adhesion to ColI.

Conclusion

3-D suspension culture and in vivo PCa tumor growth restore AR through downregulation of AP-4, enhancing integrin α2 expression and adhesion to ColI which is rich in bone matrices. The interactions of PCa with ColI, mediated by integrin α2 and AR expression, could be a key molecular event accounting for PCa bone metastasis.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/1476-4598-13-208) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: 3-D culture, Androgen Receptor, AP-4, Cell Adhesion, Collagen Type I, Integrin α2, Prostate cancer

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) has the highest incidence and is the second most common cause of cancer death among men in western countries [1]. The main clinical complication causing morbidity [2, 3] and mortality in PCa patients is bone metastasis, which presents in over 80% of all men who die of PCa [4, 5]. Despite the high occurrence of skeletal metastasis, the underlying molecular mechanisms determining the predilection of PCa cells for homing to bone are not well-understood. Previously, we hypothesized that the osteomimetic properties of PCa cells account for the predilection of PCa to metastasize and grow in the bone microenvironment [6]. We found that β-2 microglobulin (β-2 M), a major histocompatibility co-receptor, mediates the expression of non-collagenous bone matrix proteins such as osteocalcin and bone sialoprotein in metastatic human prostate cancer cell lines [7]. We found that upon the induction of β-2 M, prostate cancer cells overexpress RANKL, a protein intimately related physiologically to bone turnover [8]. RANKL drives PCa cells to undergo epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [9, 10], and when expressed by human cancer cell lines like LNCaPRANKL, produces explosive skeletal and soft tissue metastases upon intracardiac administration in mice [11].

Overexpression of RANKL plays a role in the breast cancer osteolytic phenotype by binding to its RANK receptor on precursor osteoclasts [12]. Recent studies have shown that RANKL positively correlates with higher Gleason score in PCa [13] and predicts the survival of PCa patients [14]. Denosumab, an anti-RANKL antibody approved by the FDA for the management of osteoporosis and breast and prostate cancer bone metastasis, has been shown to improve or delay skeletal metastasis in breast and prostate cancer by 35% [15] and 18% [16], respectively. However, overall patient survival is not affected, indicating the critical roles of other potential factors affected by the RANK-mediated downstream signaling network in PCa bone metastasis.

Another important factor in the development and progression of PCa is androgen receptor (AR) [17]. AR has regulatory roles promoting PCa cell adhesion and survival in bone. PCa cells are initially androgen-sensitive (AS) and respond to androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) [17]. Overtime, while PCa cells remain AR positive, they progress to become androgen-insensitive (AI) and acquire increased invasiveness and metastatic potential [18, 19]. AI tumors in hosts subjected to ADT become hypersensitive to residual intracrine androgen due in part to AR gene amplification, AR gene mutation, and/or higher AR regulating transcription factors (TFs) [20–22]. Recently, AR was found to induce cancer cell adhesion and survival through integrin expression [23–25]. Since AR plays a significant role in PCa metastasis, understanding how AR affects PCa adhesion to collagen matrix in bone could provide potential therapeutic approaches to block PCa bone homing and increase patient survival.

Multivariable tumor and microenvironmental factors are known to engage in tumor development and progression. Current 2-D monolayer culture lacks the relevant cell–cell and cell–matrix interactions that occur physiologically in the in vivo environment. This limitation makes it extremely difficult or potentially impossible to define the key cell signaling networks supporting essential cellular functions in vitro [26, 27]. Extracellular matrix (ECM) mediates biological and physical cues external to the cell that result in altered cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and adhesion. Cell-ECM communication is initiated through the interaction of α- and β-integrin subunits to specific extracellular matrices [28, 29] activating cell signaling pathways such as cell focal adhesion kinase (FAK) [30, 31]. 3-D in vitro models have an invaluable ability to recapitulate some of the in vivo cell-cell and cell-ECM interactions governing tumor cell behavior [32, 33].

In the present investigation, we used 3-D models to test the possibility that increased PCa adhesion to bone-derived ECM could promote PCa homing to bone. The objectives of this study were: 1) To investigate if RANKL overexpression promotes overexpression of integrins that support the adhesion of PCa cells to bone matrix proteins; 2) To determine if the levels of integrin expression are affected by growing PCa cells in 3-D suspension culture; 3) To determine if AR can be restored in RANKL-overexpressing LNCaP cells, and whether this restored AR modulates integrin expression/function to increase the growth, adhesion and survival of PCa cells in bone. To the best of our knowledge, we illustrated for the first time that overexpression of RANKL in human PCa cells induced dramatic upregulation of integrin α2 expression which facilitated the adhesion of PCa cells, specifically to collagen type I (ColI). We assessed and compared the adhesion of PCa cells to ColI in 2-D vs. 3-D culture, and determined the roles of FAK and Akt activation in PCa adhesion and survival. We further assessed the overall effects of AP-4, a newly identified regulator of AR, on cell adhesion to ColI via increased α2 integrin expression.

Results

Comparison of LNCaPNeo and LNCaPRANKL cell adhesion, integrated motility, and migration

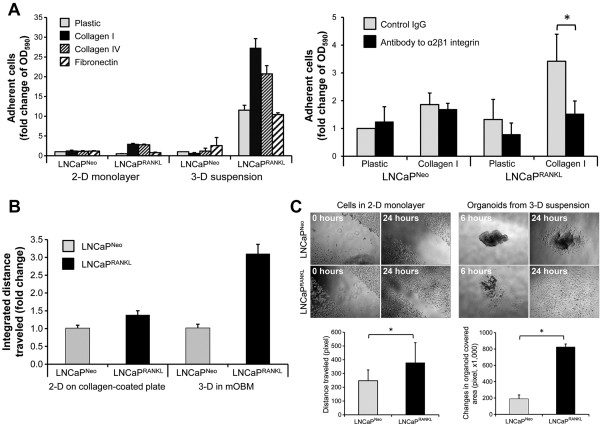

Previous studies established that RANKL-overexpressing LNCaP or ARCaP cells metastasized to bone and soft tissues when inoculated intracardially [11, 34]. We used the RANKL-transfected LNCaP cell line, LNCaPRANKL, to test the possibility that increased PCa cell homing to mouse skeleton could be due to increased cell adhesion and migration through a rise in integrin expression. We determined differential adhesion, integrated motility, and migration between LNCaPNeo and LNCaPRANKL cells under 2-D versus 3-D growth conditions. Prior to the use of 3-D conditions, we extensively compared the pros and cons of culturing PCa cells under 2-D versus 3-D using different substrata consisting of Matrigel, Hydrogel, polymeric PLGA mesh, and suspension culture in the presence or absence of ColI. The morphologic features of PCa cells under 2-D and 3-D growth conditions and their pros and cons are presented in Additional file 1: Figure S1 and Additional file 2: Table S1. Based on these comparative studies, we concluded that 3-D suspension culture has the definitive advantages of simplicity, ease of expanding into large scale culture, low cost, and production of spheroid structures that can be easily handled for histopathologic and immunohistochemical analyses of the cultured cells. After these comparative studies, we compared the adhesion and migration of LNCaPNeo and LNCaPRANKL cells cultured in a 2-D monolayer rather than 3-D suspension. Figure 1A shows that LNCaPRANKL cells attached to the ColI and collagen IV (ColIV) extracellular matrices, better than LNCaPNeo cells. Results indicate that the higher adhesion of LNCaPRANKL cells to ColI-coated plates was further enhanced when they were pre-grown in 3-D suspension culture (Figure 1A; left panel). As expected, the increased adhesion of LNCaPRANKL cells to ColI can be antagonized by an anti-α2β1 antibody, where a 55% reduction of cell adhesion to ColI was observed within 30 min (Figure 1A; right panel). We noted that LNCaPRANKL cells anchored to ColI much more rapidly (within 30 minutes) under 3-D suspension compared to growth in 2-D monolayer or compared to LNCaPNeo cells. The adhesion difference between the two cell lines and among different ECMs was not significant after 3 hours (Additional file 3: Figure S2). As illustrated, LNCaPRANKL cells also exhibited higher adhesive properties to ColIV but not to FN or plastic under suspension culture conditions. In sharp contrast, LNCaPNeo cells had no preferential binding to collagens (I and IV) under any of the culture conditions tested. The higher ColIV binding preference of LNCaPRANKL cells could explain their higher invasiveness through basement membranes compared to their parental control LNCaPNeo cells, as described previously [11]. In support of this observation, LNCaPRANKL cells exhibited greater integrated cell motility in 3-D mOBM containing ColI [35] than on 2-D ColI-coated plates, when compared to LNCaPNeo cells (Figure 1B). We also found that while LNCaPRANKL and its parental cell line have the same growth rate (data not shown), LNCaPRANKL cells migrate farther than LNCaPNeo cells under 3-D suspension conditions and in the presence of ColI (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

LNCaP RANKL cell adhesion and migration are enhanced in 3-D suspension culture. (A) In the left panel, RANKL expression is shown to enhance the adhesion of PCa cells to ColI. For each condition, 5,000 single cells from 2-D monolayer or 3-D suspension culture were seeded on 96-well plates pre-coated with ColI, ColIV or FN. After 30 minutes of incubation, the number of adherent cells was determined using alamarBlue assay. LNCaPRANKL cells preferentially adhered to ColI, especially when the cells were pre-conditioned in 3-D suspension culture. In the right panel, a similar assay was conducted with cells pre-conditioned in 3-D suspension culture, where antagonizing antibody to α2β1 integrin was introduced to interfere with adhesion. The results are presented along with ratios to the control LNCaPNeo cells for each condition. Each data point is the mean ± SD of 6 measurements from 2 independent experiments. (B) Time lapse fluorescence microscopy was used to determine cell motility. Compared to control, motility of LNCaPRANKL cells was enhanced by 3 fold when the cells were pre-conditioned in 3-D suspension culture. Integrated distance traveled was normalized to LNCaPNeo cells and presented as the mean ± SD of 5 separate experiments. (C) Pre-conditioning in 3-D suspension culture increased the migration potential of LNCaPRANKL cells. In the upper left panels, cells in 2-D monolayer culture on ColI-coated plates were subjected to a wound healing assay. In the upper right panels, migration of cells pre-conditioned in 3-D suspension culture was assessed. In the lower panels, changes in cell migration were quantified based on the results of 3 separate experiments.

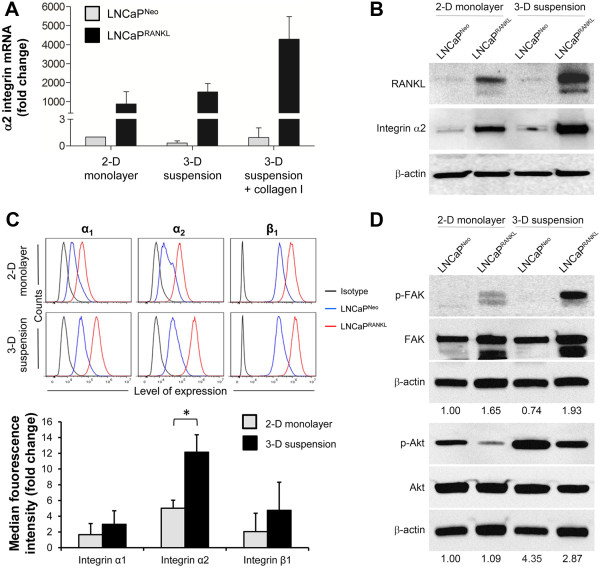

Increased integrin α2 mediates activated phosphorylation of FAK and Akt in LNCaPRANKL cells under 3-D suspension growth

Among the known receptors for ColI, α2β1 subunits are shown to be specific to ColI and play a critical role in PCa [36, 37]. Our preliminary comparative microarray analysis of 2-D monolayer grown LNCaPNeo and LNCaPRANKL cells revealed increased α2 integrin expression (Additional file 4: Figure S3A). Using microarray data, we also found that integrin α2 expression in LNCaPRANKL cells was further enhanced by subjecting LNCaPRANKL cells to 3-D suspension culture (Additional file 4: Figure S3A). mRNA and protein expression of integrin α2 was performed in each condition and confirmed the microarray data (Figure 2A, 2B). qRT-PCR analysis of cell embedded in suspension containing 0.1 mg/ml ColI suggests that higher expression of integrin α2 in cells could be further triggered in the presence of ColI (Figure 2A). These results were confirmed by FACS analysis comparing integrin α2 expression between LNCaPNeo and LNCaPRANKL cells cultured under 2-D monolayer and 3-D suspension conditions (Figure 2C). Quantitative analysis of FACS data revealed that integrin α2expression of LNCaPRANKL/LNCaPNeo cells increased by 2.4 fold when cells were cultured in 3-D suspension as opposed to 2-D monolayer culture. FACS analysis did not show any significant changes in α1 and β1 integrin expression. Increase in integrin α2 expression appeared to be controlled by the RANKL/RANK axis, as the protein expression of RANKL correlates with integrin α2 expression (Figure 2B). This was further confirmed by using LNCaPRANKL cells with RANK knocked down. Disrupting the RANKL/RANK pathway resulted in reduced mRNA and protein expression of integrin α2 (Additional file 4: Figure S3B). Interestingly, the protein expression of RANKL of LNCaPRANKL cells grown in the 3-D suspension culture illustrates expression of the smaller band besides the total RANKL. This band could represent a soluble RANKL. In a parallel study using Elisa assay we have shown that soluble RANKL only increases by 7% in LNCaPNeo cells when compared 3-D suspension with 2-D monolayer. However, this difference increases to 30% in LNCaPRANKL cells. Higher soluble RANKL in 3-D suspension could be explained by potentially higher MMP7 expression in this condition, which is known to be responsible for the cleavage of RANKL [38]. Corresponding with the increased integrin α2, we also observed that LNCaPRANKL cells expressed higher levels of phosphorylated focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and phosphorylated Akt, when compared to 2-D monolayer (Figure 2D). Interestingly, under 3-D suspension conditions, LNCaPNeo parental cells showed slightly lower p-FAK expression, while Akt phosphorylation was significantly higher. These data in aggregate suggest that RANKL-expressing PCa cells grown in 3-D suspension have elevated cell adhesion and survival capability and this is likely mediated by activated α2β1 integrin.

Figure 2.

RANKL overexpression induces integrin α 2 expression, which mediates FAK and Akt phosphorylation. (A) LNCaPRANKL cells expressed increased α2 integrin as determined with qRT-PCR. The expression was the highest when the cells were grown in the 3-D suspension that contained ColI. (B) Increased α2 integrin expression, appearing in a RANKL-dependent manner, was confirmed with western blotting. (C) In the upper panels, cell surface expression of α1, α2 and β1 integrins was detected with FACS. Results indicate significantly higher α2 integrin expression in RANKL-overexpressing cells grown in 3-D suspension. In the lower panel, the histogram represents the ratio of the surface integrin protein level of LNCaPRANKL/LNCaPNeo cells quantified as median fluorescence intensity. Each value is the mean ± SD of two independent experiments. (D) Increased α2 integrin is accompanied by higher p-FAK and p-Akt levels as determined by western blotting. For each group, the ratio of p-FAK/FAk and p-Akt/Akt normalized to LNCaPNeo is shown. Blots were cropped to emphasize the relevant bands.

Other ECM receptors have been shown to play a role in PCa invasion and migration including ColIV receptor, α1β1 [39], laminin receptors, α3β1 [40] and α6β1 [25], and fibronectin receptor, αvβ3 [41]. We compared the microarray expression of α1, α3, α6, αv, β1, and β3 between LNCaPNeo and LNCaPRANKL cells. Other than increased integrin α2 expression, only integrin αvβ3 showed significantly increased expression in 3-D suspension versus 2-D monolayer culture (Additional file 4: Figure S3A). However, we could not confirm the differential expression of this integrin by FACS analysis (data not shown). Additionally, we analyzed the cell surface expression of integrin α2 in the androgen-refractory PCa cancer cell line, ARCaP. Upon malignant progression, ARCaPM cells are known to express high endogenous RANKL [9] and fail to express functional AR [42]. ARCaPM cells were found to express lower levels of integrin α2 than indolent ARCaPE cells (Additional file 4: Figure S3C).

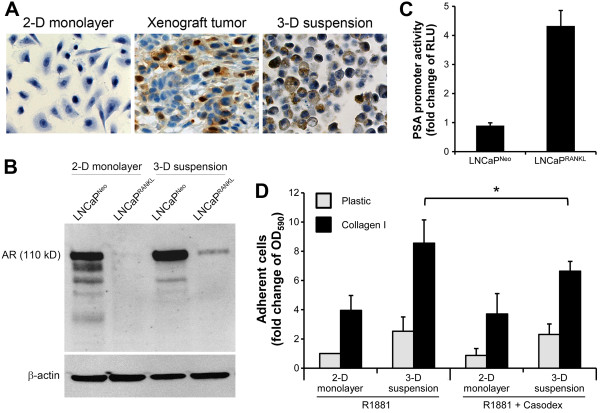

Restoration of AR expression in LNCaPRANKLcells in vivoand in 3-D suspension culture enhances cell adhesion to ColI

Since AR is diminished in metastatic LNCaPRANKL cells compared to their parental LNCaPNeo cells, we tested the possibility of restoring AR activity by growing LNCaPRANKL cells in in vivo as tumor xenografts or 3-D suspension cultures. As shown in Figure 3A, AR protein expression in LNCaPRANKL cells is undetectable when grown as a 2-D monolayer. IHC staining of AR revealed positive staining of LNCaPRANKL cells grown subcutaneously (Figure 3A). Further, AR IHC staining was also observed in 3-D suspension cultures of LNCaPRANKL cells and this was confirmed by Western blot (Figure 3A, 3B). The restored AR in LNCaPRANKL cells was shown to be biologically functional as revealed by increased PSA promoter luciferase activity in LNCaPRANKL cells (Figure 3C). PSA promoter luciferase activity was significantly elevated in LNCaPRANKL cells grown in 3-D suspension culture as opposed to 2-D monolayer culture. Because AR was shown to drive integrin α2 expression in PCa cells [23, 43], we asked if restoration of AR expression in LNCaPRANKL cells, grown in 3-D suspension, enhanced cell adhesion to ColI. LNCaPRANKL cells grown on 2-D monolayer or in 3-D suspension were treated with 10nM R1881, an androgen agonist, or 10 nM R1881 plus an AR antagonist, Casodex (Bicalutamide, 20nM). Cell adhesion to ColI was examined relative to plastic as a control. Under R1881 treatment, in either 2-D monolayer or 3-D suspension culture, LNCaPRANKL cell adhesion to ColI compared to plastic control was significantly higher by 4- and 9-fold, respectively. Casodex was found to block the adhesion of LNCaPRANKL cells to ColI by 1.3-fold in 3-D suspension culture. As expected, AR antagonist did not affect the ColI binding of LNCaPRANKL cells when grown in a 2-D monolayer because of the absence of detectable AR expression under this culture condition (Figure 3D). These results suggest that activated AR, in the presence of R1881 treatment, induces integrin α2 expression and is responsible for the increased adhesion of LNCaPRANKL cells to a ColI substratum.

Figure 3.

Restored AR expression in LNCaP RANKL cells grown in 3-D suspension increases cell adhesion to ColI. (A) IHC analysis indicates that the suppressed AR expression in LNCaPRANKL cells could be restored, when the cells were grown as a xenograft tumor or in 3-D suspension culture. Arrows denote AR nuclear localization. (B) Restored AR in LNCaPRANKL cells grown in 3-D suspension was confirmed with western blotting. While AR expression is high in LNCaPNeo cell grown in 2-D monolayer or 3-D suspension, LNCaPRANKL cells express AR protein only under 3-D suspension conditions. (C) The restored AR is biologically functional since it could promote PSA promoter activity as detected by a PSA promoter-luciferase reporter assay, which showed 4.3-fold increased activity in 3-D suspension culture compared to the LNCaPRANKL cells in 2-D monolayer. Each black bar represents relative light unit (RLU) as a fold difference of 3-D suspension/2-D monolayer for each cell line. (D) The function of the restored AR protein in regulating cell adhesion was indicated by treating LNCaPRANKL cells with the synthetic androgen R1881 (10 nM, 48 hours), which resulted in significantly enhanced cell adhesion to ColI. On the other hand, the antagonistic effect of the anti-androgen casodex (20 nM) was seen mainly under 3-D suspension culture conditions. Each value is the mean ± SD of 2 independent experiments done in triplicate.

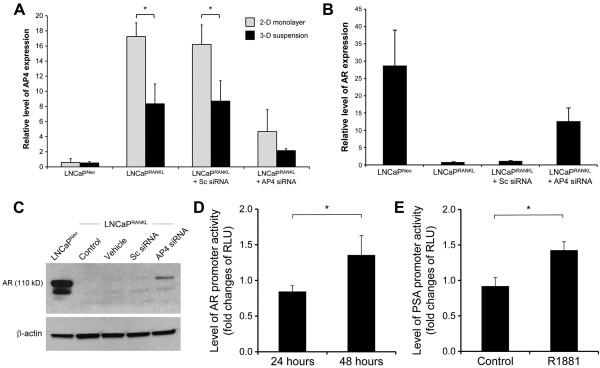

Restoration of AR expression by downregulating transcription factor AP-4

Our previous publication using site-directed mutagenesis and transcription factor deletion/interference assays identified the suppressive action of AP-4 on AR expression [11]. We hypothesized that decreased AP-4 expression could contribute to increased AR expression in LNCaPRANKL cells grown in 3-D suspension. The qRT-PCR study of AP-4 and AR expression, in LNCaPRANKL cells grown in 3-D suspension or in LNCaPRANKL cells after transient transfection with AP-4 siRNA in 2-D monolayer, revealed an inverse relationship between AP-4 and AR expression. Unlike LNCaPNeo cells, LNCaPRANKL cells grown as 2-D monolayer expressed higher AP-4 with corresponding lower AR. Upon AP-4 knockdown or in cells grown in 3-D suspension, AP-4 expression is reduced and this corresponds with increased AR expression (Figure 4A, B). AR restoration was confirmed by both Western blot and increased AR promoter luciferase activities (Figure 4C, D). In support of the above observations, we also showed that the restored AR was functional, capable of driving increased PSA-promoter luciferase activity by 1.6 fold (Figure 4E). In resemblance to AP-4 which induced EMT in colorectal cancer [44], AP-4 siRNA transfected LNCaPRANKL cells exhibited mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET), a reversal of EMT biomarker expression and decreased cell invasion (Additional file 5: Figure S4A, B). Taken together, AP-4 could be the molecular basis of AR restoration in LNCaPRANKL cells cultured in 3-D suspension. Interestingly, however, enhanced AR expression by gene transfer into LNCaPRANKL cells did not affect AP-4 expression (Additional file 5: Figure S4C), suggesting that there is no established feedback loop between AR and AP-4.

Figure 4.

AR restoration was due to the suppression of AP-4 transcription factor upon 3-D suspension culture. (A) 3-D suspension culture provided a suppressing condition for the differential AP-4 expression observed in RANKL-overexpressing cells in 2-D monolayer culture. LNCaPRANKL cells transfected with AP-4 siRNA could further reduce AP-4 expression as shown with qRT-PCR analysis. (B) AR and AP-4 appeared to have an inverse relationship of expression as detected with qRT-PCR analysis. (C) Western blotting analysis was conducted to demonstrate AR restoration upon AP-4 suppression by specific siRNA knockdown. (D) The effect of AP-4 appeared to modulate AR transcription, as determined with transient AR promoter reporter luciferase assay. For each condition, RLU was shown as the fold difference of AP-4 siRNA/SC siRNA transfection. (E) Effect of AP-4 on AR function was assessed by PSA-promoter reporter luciferase assay. In this experiment, AP-4 was first knocked down in LNCaPRANKL cells. AR responsiveness to androgen R1881 was then measured by PSA promoter reporter luciferase assay.

Discussion

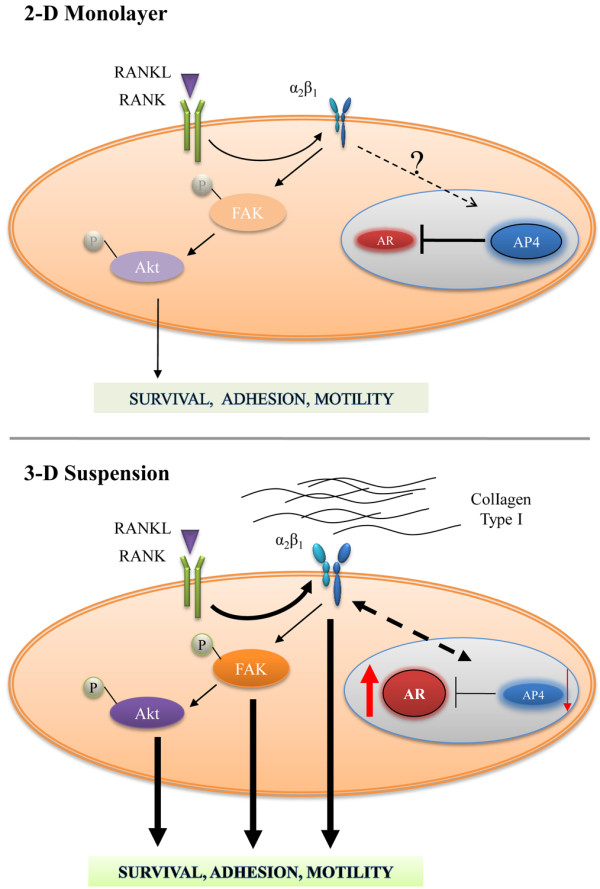

The bone environment is enriched with cytokines, growth factors, progenitor cells, and hematopoietic cells, providing a suitable metastatic microenvironment to promote PCa tumor cell adhesion, proliferation, migration, and survival. Despite this supportive microenvironment, cancer bone metastasis is a highly inefficient process and occurs infrequently in cancer patients [45]. However, 80% of all PCa metastatic lesions exist in the bone [4, 5]. To understand the interactions between the tumor and its microenvironment, we engineered an indolent human PCa cell line, LNCaP, with RANKL. We examined LNCaPRANKL and ARCaPM cells, which endogenously expressed a high level of RANKL, for their metastatic potential to bone and soft tissues. The results consistently showed that RANKL drives these cells to undergo EMT and assume many characteristics considered as metastatic cancer cell phenotypes, including the expression of mesenchymal and stem cell biomarkers, neuroendocrine and osteomimetic properties [46], gaining the propensity for metastasis to bone and soft tissues in mice [11]. Further, Chu et al. [11] showed that RANKL protein administered by the intra-peritoneal route can induce prostate cancer bone colonization in mice, confirming the importance of the pathophysiological role of RANKL as both autocrine and paracrine factor. In this study, we specifically examined the effects of the RANKL-RANK mediated signal network that drives PCa cells to express selected integrin isotypes favoring their adhesion to collagens, known to be rich in the bone microenvironment. Our work reveals the importance of the 3-D culture environment that determines integrin expression via functional AR and ultimately affects the pathophysiology of PCa metastases. The pathophysiologic significance of our findings is depicted in Figure 5. 1) RANKL/RANK signaling augments integrin α2 expression in RANKL-transfected LNCaP cells but not in ARCaP cells overexpressing RANKL intrinsically (Figure 2, Additional file 4: Figure S3). This observation could possibly be due to the nearly undetectable levels of AR expression in the ARCaP cell line [42]. This suggests that other cell surface receptors, such as discoldin domain receptors [47, 48], glycoprotein VI receptor [49], leukocyte-associated Ig-like receptor [50] or mannose receptor [51, 52], could be downstream targets of the RANK-mediated signal network that controls ARCaPM cell progression and metastasis by interacting with collagen matrices. 2) Consistent with the high bone metastatic behavior of LNCaPRANKL cells, we have shown for the first time that integrin α2 expression is significantly enhanced in a 3-D suspension model in a RANKL-dependent manner (Figure 2). Exacerbated integrin α2 expression increases the binding of these cells specifically to ColI, the most abundant bone matrix protein (Figure 1). Their profound cell binding to ColI and migration can clearly discriminate indolent LNCaPNeo and metastatic LNCaPRANKL cell lines when cultured in 3-D suspension. Concurrently, we observed that anti-α2β1 antibody effectively antagonized LNCaPRANKL cell binding to ColI matrix (Figure 1). Enhanced integrin α2 expression was shown to facilitate the adhesion and survival of PCa cells through activated FAK and Akt phosphorylation (Figure 2). High expression of integrin α2 in metastatic PCa and its important role in cell survival and adhesion in the bone microenvironment is supported by recent experimental and clinical publications [53, 54]. 3) Concomitant with enhanced integrin α2 expression, we also observed that LNCaPRANKL cells grown in 3-D suspension exhibited elevated functional AR expression, a result not seen in 2-D monolayer culture (Figure 3). It worth mentioning, while functional assay of AR on LNCaPRANKL cells showed 4.3 fold increases in 3-D suspension/ 2-D monolayer, the fold difference in AR protein level seemed to be higher. However, we would not expect a linear relationship between AR and its responsive promoter-reporter activity due largely to the efficiency of AR and its accessory transcriptional factors binding to the promoters and also the efficiency of the translational machinery of proteins in cells that ultimately determine the promoter reporter activity. Moreover, inhibition of AR nuclear translocation by Casodex treatment reduced LNCaPRANKL cell adhesion to ColI (Figure 3), suggesting that LNCaPRANKL cell adhesion through integrin α2 is potentially AR-dependent. Our data are in agreement with those of Nagakawa et al. [23] who showed that integrin α2 expression and ColI adhesion could be elevated by AR expression in an AR-transfected PCa cell line, DU145. In support of experimental studies, we used the publicly available human prostate cancer genome data listed in TCGA [55], to confirm a direct correlation between mRNA expression of AR and integrin α2 (Spearman’s correlation = 0.60, N = 302). Therefore, the adhesion of PCa cells in the bone microenvironment could be enhanced by modulating AR expression and function. While our study and others suggest that AR could regulate integrin α2, we were unable to find evidence that integrin α2 directly increases AR activity. Our studies of AR promoter did not reveal any binding sites for integrin α2. However, further studies are required to finally conclude whether integrin α2 could directly or indirectly regulate AR expression. 4) We further illustrated that AR restoration in LNCaPRANKL cells under 3-D suspension condition is at the transcriptional level via downregulation of a key TF repressor, AP-4 (Figure 4). AP-4 overexpression concerts the upregulation of c-Myc/Max in RANKL-overexpressing PCa cells [11] and drives EMT in colorectal cancer [44, 56]. Similarly, downregulation of AP-4 with a concomitant increased expression of AR and integrin α2 in PCa cells results in the reversal of EMT and reduced PC invasion (Additional file 5: Figure S4). Because enhanced AR activity was frequently observed in clinically advanced PCa specimens [57, 58], we hypothesize that enhanced AR expression in LNCaPRANKL tumors could enhance the adhesion and survival of LNCaPRANKL cells in mice. In agreement with clinical observations and the role of AP-4 downregulation, our preliminary data showed that LNCaPRANKL cells overexpressing AR did have enhanced growth when inoculated as subcutaneous tumor xenografts in mice (data not shown). Further in vivo studies are warranted to determine if AR expression in LNCaPRANKL cells could confer increased α2 integrin expression and bone colonization through adhesion of PCa cells to collagen matrix in the skeleton.

Figure 5.

Schematic summary of the role of RANKL-overexpression in promoting cancer cell adhesion. In LNCaPRANKL cells, RANKL overexpression induced the expression of α2 integrin and AP-4 transcription factor. The later may account for the suppressed AR expression. In 3-D suspension culture, α2β1 integrin was activated through RANKL expressed by PCa cells or soluble RANKL expressed by stromal cells in the bone microenvironment. This activation would elicit FAK and Akt phosphorylation, resulting in enhanced cell motility, adhesion and survival. α2β1 integrin activation was further enhanced through AP-4 downregulation, resulting in AR accumulation that could play a role in LNCaPRANKL cell adhesion to ColI. We propose a possible positive feedback loop (dotted line) between AR and integrin α2 regulation that is further enhanced under 3-D conditions to support cell anchoring and survival in the bone microenvironment.

Our work reveals the importance of the 3-D culture environment that determines integrin expression via functional AR and ultimately affects the pathophysiology of PCa metastases. Our significant findings are as follows: 1) The ability of PCa cells to adhere, survive and metastasize to bone could be masked by culturing PCa cells as a 2-D monolayer. We observed that RANKL-overexpressing PCa cells have barely detectable AR when cultured on plastic. When these cells were grown as 3-D suspensions or in mice, AR was found to be restored and to activate PSA promoter-luciferase activity. Additionally, we observed higher adhesion of LNCaPRANKL cells to ColI in an AR-dependent manner, most likely through increased expression of α2 integrin. These results are consistent with the high levels of AR expression in clinical PCa bone metastasis specimens. 2) The TF repressor, AP-4, was found to be a negative regulator of AR at the transcriptional level and is modulated in a cell context-dependent manner. We speculate that AP-4 downregulation, epigenetically via promoter methylation or genetically via AP-4 regulators such as c-Myc, could play a decisive role in upregulating the levels of AR. This could profoundly control the responses of prostate tumors to androgen deprivation therapy. 3) Upregulation of integrin α2 may be a common path for human PCa to develop castration resistance and bone metastasis. Balasubramaniam et al. recently studied BAF57, a component of the switching-defective and sucrose nonfermenting (SWI/SNF) chromatin-remodeling complex conglomerate [59]. They found that BAF57 deregulation circumvented androgen-mediated signaling, upregulated α2 integrin expression, altered other SWI/SNF complex components at the α2 integrin locus and conferred a prometastatic migratory advantage on PCa cells that could contribute to castration resistance and bone metastasis in patients [60]. Hall et al. [36] demonstrated experimentally that LNCaP cells selected for ColI binding exhibit higher integrin α2 expression, become more adhesive and migratory in in vitro and acquire the capacity to grow within the bone compared to non-collagen binding parental cells. These results are in agreement with work of Colombel et al. [54] who showed that higher α2β1 protein expression in primary PCa tissues correlates with bone metastasis. Additionally, Sottnik et al. [53] demonstrated elevation of α2β1 protein level in PCa skeleton metastases when compared to primary site or soft tissue metastases. These data along with our observations (Figure 2) suggest that ColI can re-program cell fates by forcing the expression of α2. Ultimately, through a RANKL- and α2-mediated downstream signal network ColI can transdifferentiate or reprogram non-metastatic PCa cells to gain increased adhesion, growth and survival potential in the bone microenvironment. More work is needed to build clinically relevant alternative cell signaling network models that could improve cancer diagnosis and prognosis and offer targets for therapeutic intervention.

Conclusion

The survival of patients with skeletal metastasis is very poor and more efficient prevention therapies are urgently needed. Our understanding of the role of the RANKL/RANK and AR axes in cancer cell adhesion is evolving. Our study supports direct regulation of integrin α2 and adhesion to ColI through RANKL/RANK signaling. Previous experimental and clinical studies in agreement with our data show the direct role of AR in ColI adhesion, possibly through integrin α2 expression. Our findings suggest that increased integrin activity enhances bone adhesion in a RANKL/RANK and AR dependent manner. Since there are studies supporting the regulation of AR through cell-ECM interaction, it is plausible that a positive feedback loop between AR and integrin α2 is induced under 3-D and in vivo conditions to support the growth and survival of PCa cells through activated p-FAK and p-Akt. We anticipate expanding the described 3-D suspension culture into co-culture models where relevant cancer cells and normal cells of different lineages can be constructed, studied and fully characterized. We believe that 3-D suspension culture and the co-culture of cancer cells with relevant cells in the tumor microenvironment could provide important additional insights into cancer plasticity and progression.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Cell lines and 2D culture conditions

LNCaP human prostate cancer progression models were established by our laboratory as previously described [61]. The LNCaPNeo, LNCaPRANKL, and LNCaPRANKL cells with RANK knockdown (LNCaPRANKL-RANK KD) cell lines were established by Chu et al. [11]. LNCaP was maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 5% FBS. LNCaPNeo, LNCaPRANKL, and LNCaPRANKL-RANK KD cells were also maintained in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 5% FBS with 200 ng/ml of Geneticin selector. ARCaPE and ARCaPM cells established by our laboratory [34, 42] were maintained in T-medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% FBS. MC3T3 cells (kindly provided by Dr. Neale Weitzmann, Emory University, Atlanta, GA) were maintained in DMEM supplemented by 10% FBS. All cells were incubated in 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C.

3D culture conditions

Hydrogel

Hydrogel was prepared using the HyStem Hydrogel kit (Glycosan BioSystem Inc. CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, Hystem and Extralink solutions were prepared by dissolving the lyophilized solids in DG water under aseptic conditions (1% w/v). Extralink was added to the HyStem in 1:4 ratio. The final solution was then incubated for 10 min before encapsulating the cell pellet (10,000 cells/ ml). 200 μl of the final solution was then plated in ultra-low attachment 24-well plates (Sigma) within 20 min of encapsulation for full polymerization in the 37°C incubator for 30 min before adding 1 ml complete medium per well. Collagen type I (BD Biosciences, 100 mg/ml rat tail) was added to the cell pellet at the 0.1 or 0.3 mg/ml final concentration (PH 7.0) before encapsulation, when specified. Medium was changed every 3 days by removing 500 μl/well of the medium and replacing it with 500 μl of fresh complete medium.

Suspension

LNCaPNeo and LNCaPRANKL cells, cultured on plastic, were trypsinized at the log phase, washed and resuspended to a final concentration of 20,000 cells/ml. One ml of the final solution was then plated in ultra-low attachment 24-well plates (Sigma). Cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 5% FBS, incubated in 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C and observed up to 12 days to assess growth and morphology before harvest for additional analysis. For ColI embedded cells, 0.1 or 0.3 mg/ml of ColI was added to the cell pellet before adding the medium. Medium was changed every 3 days by removing 500 μl/well of the medium and replacing it with 500 μl of fresh complete medium.

Mesh

Poly (D,L-lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) fiber sheets (Mesh) were kindly provided by Dr. JurgenGroll, University Hospital, Würzburg, Germany [62]. Sheets 120 μm thick were trimmed to 8 mm circles using a disposable biopsy punch (Kia Medical, Inc) and placed in 48-well plates. Wells were washed with 70% EtOH and twice with 1X PBS. Plates were left under UV light for 30 min before use. LNCaPNeo and LNCaPRANKL cells were trypsinized at the log phase, washed and resuspended to a final concentration of 10,000 cells/ml. 500 μl of the final suspended cells were plated in each well and grown for 7 days before they were fixed or collected for further analysis. To study the ColI interaction with cells, mesh fibers were coated with 50 ng/ul of rat tail ColI (BD Biosciences).

Mouse osteoblast matrix (mOBM)

MC3T3-E14, mouse osteoblast precursor cells were grown on 12-well plates (VWR) for 10 days to beyond confluence. Cells were then treated with osteogenic medium (100 nmol/L dexamethasone, 10 mmol/L beta-glycerophosphate, and 0.05 mmol/L L-ascorbic acid-2-phosphate) for an extra 3 weeks with medium changes every 4 days, and then decellularized using 20nM of sterilized ammonium hydroxide (NH4OH) for 30 min,and washed extensively prior to seeding the cells [35, 63].

In vivoexperiments

All animal procedures were performed according to an approved protocol from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. LNRANKL, LNRANKL-AR cells (2×106 cells/100 μl PBS) were inoculated subcutaneously in 4-week-old male nude mice (Taconic, Oxnard, CA). All mice were followed for total of 45 days. Tumor volume was measured every 3 days.

Microarray data analyses for AR and integrin α2 gene signature

To identify potential correlations between AR and integrin α2 in human samples, we used a dataset that primarily included adenocarcinoma prostate cancer samples, the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) dataset (n = 336). Expression data for the TCGA dataset was downloaded from the TCGA data portal (http://www.cbioportal.org/public-portal/index.do).

Cell morphology

Samples were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 (Sigma) for 30 min and blocked with 5% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) (Sigma) for 1 hour. Samples were then washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4 and incubated with 4′-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (100 ng/ml, Invitrogen) and Alexa Fluor® 488 and 568 Phalloidin (4 μl/ml, Life Technologies) for 1 hr in the dark for nucleus and f-actin cytoskeleton staining, respectively. Phase-contrast images were then captured using Nikon Eclipse Ti (NIKON instruments Inc.). Organoids were placed on coverslip-bottom chambers (Lab-Tek) and fluorescent confocal images were captured using Leica TCS-SP5 Xconfocol microscopy (Leica Microsystems).

Microscopic live cell imaging and analyses

2×104 cells/ml were seeded on 12-well plates coated with 50 ng/μl or decellularized mOBM wells. A Nikon Eclipse Ti inverted microscope equipped with an automotive x-y-z stage was used for multiposition and perfect focus system time-lapse microscopy. An environmental chamber was used to maintain humidity, 5% CO2, and 37°C temperature. FITC and TRITC filters with a shutter control (Lamda SC, Smart Sutter Controller) and a CCD Head camera (Andor Technology) were used for fluorescent imaging. All imaging was performed using a 10× phase contrast (Nikon Plan Fluor Ph1) objective. All the images were also converted to TIF files for analysis of shape and integrated distanced traveled using CellProfiler 2.1.0 (Broad Institute, Boston, MA).

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA from cells was isolated using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentration was quantified using the Nanodrop-2000 (ThermoScientific). Samples with a 260/280 ratio higher than 1.8 were used for subsequent procedures. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was generated from 1 μg of total RNA using M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI), as instructed. 20 ng of cDNA was subjected to PCR analyses using an AB 7500 Fast detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) at 95°C for 10 min and 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 sec, 60°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 30 sec, followed by a dissociation curve. The sequences of all primers used are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primer sequence for qRT-PCR

| AR | Forward: | GACCAGATGGCTGTCATTCA |

| Reverse: | GGAGCCATCCAAACTCTTGA | |

| AP-4 | Forward: | GGAGTATTTCATGGTGCCCACT |

| Reverse: | GTGGAATGTTGGCAAGGCTAC | |

| E-Cad | Forward: | CCACCAAAGTCACGCTGAATA |

| Reverse: | GGAGTTGGGAAATGTGAGCAA | |

| GAPDH | Forward: | AGCCACATCGCTCAGACA |

| Reverse: | GCCCAATACGACCAAATCC | |

| ITGA2 | Forward: | TGGGGTGCAAACAGACAAGG |

| Reverse: | GTAGGTCTGCTGGTTCAG | |

| Vimentin | Forward: | GGAAGAGAACTTTGCCGTTGAA |

| Reverse: | GTGACGAGCCATTTCCTCCTT |

Western blot analysis

LNCaPNeo and LNCaPRANKL cells were cultured in 6-well plates under 2-D monolayer conditions to 70% confluence or in 3-D suspension conditions for 7 days. The cells were then pelletized and washed with PBS before being lysed in RIPA buffer (1% Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris/HCl, 1 mM EDTA and 25 mM NaF) containing 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Samples were then centrifuged and the supernatants collected and quantified using the Bradford Protein Assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). 20 μg of cell lysate were resolved on 4-15% Bis-Tris gradient SDS-PAGE (BioRad, Hercules, CA), followed by transblotting onto nitrocellulose membrane (BioRad, Hercules, CA). The membranes were blocked in 5% non-fat milk in TBST for one hour at room temperature (RT) and incubated with diluted primary antibodies in blocking buffer at 4°C overnight. The primary antibodies used were AR (1:500), integrin α2(1:500), β-actin (1:2000), AP-4 (1:500, Santa Cruz), FAK (1:1000, Abcam), p-FAK (1:1000), Akt (1:1000), p-Akt (1:2000), c-Met (1:1000), and p-c-Met (1:1000, Cell Signaling). The membranes were washed with TBST three times before incubating with peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (1:10000, Santa Cruz) at RT for one hour. After three washes, the membranes were visualized using Kodak Image Station 4000MMProinstrument (AFAB Lab resources, Frederick, MD) and Carestream MI SE Network software. Images were cropped to improve the clarity of the figures. Each image is representative of two separate studies.

Fluorescence Activated Cell Sorter (FACS)

LNCaPNeo and LNCaPRANKL cells were detached from 2-D monolayer using accutase (Millipore) to preserve membrane receptors. Organoids from 3-D suspension culture were made into single cells using a final concentration of 1 mg/10 ml collagenase in accutase and 20 min incubation at 37°C. Cells were then washed and resuspended into single cell suspension in 1 × PBS containing 1% FBS (FACS buffer). After two washes with cold FACS buffer, cells were incubated for 30 min on ice with FITC-tagged anti-human CD49a, CD49b, CD51/61 and PE anti-human CD29 (BioLegend) or isotype control FITC mouse IgG1, k (eBioscience). Antibodies were washed twice with FACS buffer. Cell fluorescence signals were determined immediately after staining using a BD Accuri C6 flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) equipped with an argon laser emission of 488 nm. FITC and PE were identified using a 530 ± 15 nm and 585 ± 20 nm band pass filter, respectively. The analysis was performed using FlowJo software (TreeStar Inc.). A primary gate was set excluding dead cells or debris based on physical parameters (forward and side light scatter, FSC and SSC, respectively).

Adhesion assay

The adhesion assay was a modification of a previously published protocol [64]. For each condition, 1×105 cells/ml were placed in 15-ml conical tubes and 10 μg/ml α2β1 blocking antibody (VLA-2 Millipro) or IgG1 isotype control (bioLegend) was added and incubated for 20 minutes at room temperature. Binding assays were performed by seeding 5000 cells in 100 μl of complete medium on plastic or fibronectin-, collagen-IV-, or collagen I-precoated 96-well plates (BD Biosciences). At 30 min, 1-, 3-, 6-, 12- and 24-hr time points, wells were washed twice with PBS, 100 μl of complete medium was replaced, and 10 μlof alamarBlue (Invitrogen) was added, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After 12 hrs incubation at 37°C in the dark, the plates were read using the Spectra max M2 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) at 590 nm with Softmax Pro software. All the readings were normalized to the reading of the well with no cells as a background measurement. The initial activity of the cells was measured by adding 10 μl of alamarBlue directly to the well without washing the cells.

For cells treated with R1881 and/or Casodex, serum-starved medium with 5% dextran-coated charcoal was used instead of complete medium. Plates were washed at 30 min and 1 hr time points and read after 12 hrs of alamaBlue assay. Each condition was performed in triplicate and two independent experiments were carried out per condition.

Immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis

Sample preparation

IHC staining was applied to cells grown as in vitro 2-D monolayers. Cells were grown directly on 8-chamber slides to 80% confluence. In some cases, cells were grown as in vitro 3-D organoids. Organoids harvested from the 3-D suspension culture were carefully collected into 1.5 ml eppendorf tubes and spun down to a pellet. 1% LMP agarose solution was prepared and added to the pellet. After solidification, using a micro spatula, agarose-cell pellets were wrapped in tissue paper, placed in a plastic tissue cassette, and tissue processing was performed overnight using an automated tissue processor. For in vivo tissues, subcutaneous tumors were collected and fixed in 4% formaldehyde immediately for 24 hrs. The next day, tumors were processed for paraffin embedment as described above.

Histology analysis

IHC was followed according a previously published protocol [10]. All reagents from the DAKO system (Carpinteria, CA) were used for immunoperoxidase staining of the sectioned slides. Paraffin-embedded slides were rehydrated and antigenic epitopes were retrieved in citrate buffer using a pressure cooker. After antigen retrieval, slides were blocked with dual endogenous enzyme block (DEEB) at RT for 10 min and incubated with primary antibodies against AR (Santa Cruz) at 4°C overnight. The slides were placed at RT for 1 h, rinsed in Tris-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween (TBST) and incubated with Envision + Labeled Polymer-HRP at RT for 30 min. The slides were incubated with peroxidase substrate buffer with a chromogen, diaminobenzidine (DAB), to detect the staining signal, followed by hematoxylin counterstaining of nuclei. After dehydration and cover-slipping, the slides were examined by light microscopy. For monolayer samples, slides were blocked without the peroxidase step.

Transient transfection and luciferase reporter assays

AR [65] promoter-luciferase plasmid DNA and control CMV-TK plasmid DNA (for transfection efficiency control) were transiently transfected into prostate cancer cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 48 hrs. The cells were then harvested and protein lysate extracted using 1× passive lysis buffer (Promega, Madison, WI). The lysate was centrifuged at 13,200 rpm at 4°C for 10 min, and the supernatant was collected for luciferase assay. Promoter and TK activity was measured using Dual-Glo luciferase assay, as instructed (Promega, Madison, WI). In short, 20 μl of protein lysate was mixed with 100 μl of substrate (luciferin) and luciferase activity was measured using a BD Monolight 3010 luminometer (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). TK activity was measured by immediately adding 100 μl of Stop&Glo buffer with 50× Stop&Glo substrate to the mix and re-measuring the samples. The relative luciferase activity of each sample was calculated by normalizing to the TK activity. To assess PSA [66] promoter-luciferase activity, we followed the same procedure as above. In addition, cells were serum-starved for 24 hrs before treatment with either 10 nM ethanol or R1881 for another 48 hrs before harvest. Each condition was done in quartet and two independent experiments were carried out per assay.

Migration and invasion assays

Cell migration and invasion analysis were performed in a 24-well plates using Transwell™ chambers (BD Biosciences). As described previously, transwells were coated with collagen type I or growth factor reduced Matrigel (BD Biosciences) for migration or invasion assay, respectively. LNCaPNeo, LNCaPRANKL-control and LNCaPRANKL-AP-4 KD were serum-starved in RPMI 1640 overnight. The next day, transwells were placed on 24-well plates with 400 μl of complete medium. 100 μl of serum-free RPMI 1640 containing 5x104 cells were seeded inside the chambers for 24 hr (migration) or 48 hr (invasion) at 37°C. At each time point, cells remaining on the transwell were fixed with 10% formaldehyde and stained with 0.5% crystal violet. Cells inside the chamber were cleared and remaining cells where quantified [67].

In vitrohealing assay and 3D migration assay

24-well plates were coated with 50 ng/μl rat tail ColI and stored at 4°C overnight. Wells were washed twice with PBS before use. For the 2-D wound healing assay, cells were seeded in 24-well plates and cultured to 90% confluence. A straight scratch was made using a 1,000 μl pipette tip to simulate a wound. Wells were washed with 1X PBS to remove unattached cells. Wells were imaged at time zero and after 24 hrs using the 4× objective. Images were analyzed using ImageJ and the distanced traveled was measured. Three images were taken of each triplicate well for two independent experiments. For the 3-D migration assay, organoids were taken from 7-day suspension culture and placed on 24-well ColI-coated plates. Images were captured right after seeding and at 24, 48, and 72 hrs. The area covered by the cells was measured using ImageJ and compared between the two cell lines at each time point. The study was done in triplicate for two independent experiments.

Cell transfection and transduction protocol

LNCaPRANKL cells were grown in 6-well plates to 60% confluence, then transfected with 100 pmol final concentration of AP-4 siRNA or control siRNA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) for 48 hrs, using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Samples were collected for qRT-PCR and western blot analysis or further transfected with AR or PSA promoter for the luciferase promoter assay as described above.

For cell transduction, LNCaPRANKL cells were grown in 48-well plates to 50% confluence 24 hrs before transduction. Next day, the complete medium was replaced with complete medium containing Polybrene at a 5 μg/ml final concentration. Cells were infected with AP-4 or control sh-RNA lentiviral particles (Santa Cruz) for 24 hrs. Cells were cultured for an extra 24 hrs before being split to 1:3 ratio. Cell selection was started after an additional 24 hrs with 2 μg/ml of Puromycin.

Microarray analysis

RNA was isolated as above, hybridized to human U133plus2.0 array, and Affymetrix Gene Chip Expression Analysis was performed (UCLA Clinical Microarray Core). The microarray data was first pre-processed with quantile normalization. Genes were selected based on Students T- tests with P <0.05 and fold changes >2.

Statistical analysis

Differences between groups were analyzed using Student’s t-test. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant (denoted by an asterisk). At least three independent in vitro experiments were conducted in triplicate for all assays and analyses, unless otherwise specified.

Electronic supplementary material

Additional file 1: Figure S1: Morphological features of prostate cancer cells in 2-D monolayer and 3-D suspension cultures. The growth of RANKL-overexpressing LNCaP cells was evaluated in 2-D monolayer or in 3-D embedded in hydrogel, on polymeric meshes, and in suspension cultures, in combination with the addition of ColI. The control LNCaPNeo cells formed massive spheroids with hollow lumens (not shown) and exhibited clear invadopodia in the presence of ColI. In comparison, LNCaPRANKL cells formed only loosely-aggregated organoids in 3-D suspension culture, but were mostly in dispersed growth in other cultures. DAPI staining is shown in blue, and F-actin staining is green in 2-D monolayer but yellow in Mesh or 3-D suspension culture. (TIFF 4 MB)

Additional file 2: Table S1: Assessments of 3-D culture conditions. 2-D monolayer culture on plastic was compared with models of 3-D cultures in matrigel, hydrogel, Mesh, and in suspension. 3-D suspension culture was found to be superior in terms of biological relevance, sample production for further molecular analysis, time and cost efficiency, and ease of operation. (TIFF 388 KB)

Additional file 3: Figure S2: Transient differences in the adhesion of LNCaPNeo and LNCaPRANKL cells to ECM proteins. Cells grown on a 2-D monolayer or in 3-D suspension were harvested in single-cell preparation. For each group, 5,000 cells were seeded on 96-well plates coated with ColI, ColIV, or FN. Adhered cells at different times of incubation were determined by alamarBlue assay. Each value is the mean ± SD of 2 independent experiments done in triplicate. (TIFF 333 KB)

Additional file 4: Figure 3: Integrin expression was regulated by RANKL and by the 3-D suspension culture condition. (A) The expression of integrin isoforms was profiled by microarray analysis. Values represented fold changes in LNCaPRANKL cells compared to the LNCaPNeo control. As signified in red, α2, αv and β3 integrins had more than 2 fold increases when grown in 3-D suspension. (B) The expression of α2 integrin appeared to be dependent on the RANKL/RANK pathway, as reduced expression was seen by qRT-PCR and western blot when the pathway was interfered with RANK knockdown (RANK-KD). (C) Top panels, human prostate cancer ARCaPE and ARCaPM cells grown on a monolayer were stained for α1 and α2 integrins for FACS analysis. Bottom Panel, quantification of the FACS detection suggested that α2 integrin expression was lower in the more aggressive cell line ARCaPM compared with ARCaPE cells. (TIFF 651 KB)

Additional file 5: Figure S4: Suppressing AP-4 led to reversal of EMT and a decrease in cell invasion. (A) LNCaPRANKL cells treated with AP-4 siRNA were studied for EMT markers at the mRNA and protein level. Upon AP-4 KD, vimentin expression was reduced while E-cadherin was increased. (B) LNCaPRANKL cells treated with AP-4 shRNA showed significantly decreased invasive potential, while no changes in migration were observed. (C) AR expression vector was used to express AR in LNCaPRANKL cells (LNCaPRANKL-AR). No changes in AP-4 expression were found by qRT-PCR analysis, compared to cells transfected with an empty vector (LNCaPRANKL-EV). (TIFF 2 MB)

Acknowledgment

The authors express their gratitude to Dr. Neil Bhowmick for valuable discussion and data interpretation; Dr. Shirly Sieh (Queensland University of Technology, Australia) for standardization of the 3-D studies and data analysis; Drs. Ruoxiang Wang, Manisha Tripathi and Sandrine Billet for critical reading of the manuscript; and Mr Gary Mawyer for manuscript editing. This work was funded by NCI P01 grant (2P01CA098912) and R01 grant (1R01CA122602).

Abbreviations

- DAPI

4′-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- ADT

Androgen deprivation therapy

- AR

Androgen receptor

- AI

Androgen-insensitive

- AS

Androgen-sensitive

- BSA

Bovine Serum Albumin

- ColI

Collagen type I

- ColIV

Collagen type IV

- EMT

Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

- FN

Fibronectin

- FACS

Fluorescence Activated Cell Sorter

- FAK

Focal adhesion kinase

- IHC

Immunohistochemical

- MET

Mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition

- mOBM

Mouse osteoblast matrix

- PBS

Phosphate-buffered saline

- PLGA

Poly (D,L-lactide-co-glycolide)

- Mesh

PLGA fiber sheets

- PCa

Prostate cancer

- qRT-PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR

- RANKL

Receptor activator of NF kappa-B ligand

- 3-D

Three-dimensional

- TF

Transcription factor.

Footnotes

Competing interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

Authors’ contributions

SZ participated in the design of the study, carried out all the experiments, drafted the manuscript, and performed statistical analysis. LWC contributed to the design of the study and editing of the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Shabnam Ziaee, Email: Shabnam.ziaee@cshs.org.

Leland WK Chung, Email: Leland.chung@cshs.org.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society . Cancer Facts & Figures 2013. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coleman RE. Skeletal complications of malignancy. Cancer. 1997;80:1588–1594. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19971015)80:8+<1588::AID-CNCR9>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coleman RE. Clinical features of metastatic bone disease and risk of skeletal morbidity. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:6243s–6249s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harada M, Iida M, Yamaguchi M, Shida K. Analysis of bone metastasis of prostatic adenocarcinoma in 137 autopsy cases. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1992;324:173–182. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-3398-6_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bubendorf L, Schopfer A, Wagner U, Sauter G, Moch H, Willi N, Gasser TC, Mihatsch MJ. Metastatic patterns of prostate cancer: an autopsy study of 1,589 patients. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:578–583. doi: 10.1053/hp.2000.6698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koeneman KS, Yeung F, Chung LW. Osteomimetic properties of prostate cancer cells: a hypothesis supporting the predilection of prostate cancer metastasis and growth in the bone environment. Prostate. 1999;39:246–261. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0045(19990601)39:4<246::AID-PROS5>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang WC, Wu D, Xie Z, Zhau HE, Nomura T, Zayzafoon M, Pohl J, Hsieh CL, Weitzmann MN, Farach-Carson MC, Chung LW. beta2-microglobulin is a signaling and growth-promoting factor for human prostate cancer bone metastasis. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9108–9116. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Josson S, Nomura T, Lin JT, Huang WC, Wu D, Zhau HE, Zayzafoon M, Weizmann MN, Gururajan M, Chung LW. beta2-microglobulin induces epithelial to mesenchymal transition and confers cancer lethality and bone metastasis in human cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2011;71:2600–2610. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Odero-Marah VA, Wang R, Chu G, Zayzafoon M, Xu J, Shi C, Marshall FF, Zhau HE, Chung LW. Receptor activator of NF-kappaB Ligand (RANKL) expression is associated with epithelial to mesenchymal transition in human prostate cancer cells. Cell Res. 2008;18:858–870. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhau HE, Odero-Marah V, Lue HW, Nomura T, Wang R, Chu G, Liu ZR, Zhou BP, Huang WC, Chung LW. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) in human prostate cancer: lessons learned from ARCaP model. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2008;25:601–610. doi: 10.1007/s10585-008-9183-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chu GC, Zhau HE, Wang R, Rogatko A, Feng X, Zayzafoon M, Liu Y, Farach-Carson MC, You S, Kim J, Freeman MR, Chung LW. RANK- and c-Met-mediated signal network promotes prostate cancer metastatic colonization. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2014;21:311–326. doi: 10.1530/ERC-13-0548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohshiba T, Miyaura C, Inada M, Ito A. Role of RANKL-induced osteoclast formation and MMP-dependent matrix degradation in bone destruction by breast cancer metastasis. Br J Cancer. 2003;88:1318–1326. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen G, Sircar K, Aprikian A, Potti A, Goltzman D, Rabbani SA. Expression of RANKL/RANK/OPG in primary and metastatic human prostate cancer as markers of disease stage and functional regulation. Cancer. 2006;107:289–298. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu P, Chung LW, Berel D, Frierson HF, Yang H, Liu C, Wang R, Li Q, Rogatko A, Zhau HE. Convergent RANK- and c-Met-mediated signaling components predict survival of patients with prostate cancer: an interracial comparative study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e73081. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bergman DA. Endocrine Today. 2009. Denosumab: Fracture risk reduced in high-risk subset in FREEDOM. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fizazi K, Carducci M, Smith M, Damiao R, Brown J, Karsh L, Milecki P, Shore N, Rader M, Wang H, Jiang Q, Tadros S, Dansey R, Goessl C. Denosumab versus zoledronic acid for treatment of bone metastases in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer: a randomised, double-blind study. Lancet. 2011;377:813–822. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62344-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huggins C, Stevens RE, Hodges CV. Studies on prostatic cancer ii. The effects of castration on advanced carcinoma of the prostate gland. Arch Surg. 1941;43:209–223. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1941.01210140043004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feldman BJ, Feldman D. The development of androgen-independent prostate cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2001;1:34–45. doi: 10.1038/35094009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pienta KJ, Bradley D. Mechanisms underlying the development of androgen-independent prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:1665–1671. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gregory CW, He B, Johnson RT, Ford OH, Mohler JL, French FS, Wilson EM. A mechanism for androgen receptor-mediated prostate cancer recurrence after androgen deprivation therapy. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4315–4319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen CD, Welsbie DS, Tran C, Baek SH, Chen R, Vessella R, Rosenfeld MG, Sawyers CL. Molecular determinants of resistance to antiandrogen therapy. Nat Med. 2004;10:33–39. doi: 10.1038/nm972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Waltering KK, Helenius MA, Sahu B, Manni V, Linja MJ, Janne OA, Visakorpi T. Increased expression of androgen receptor sensitizes prostate cancer cells to low levels of androgens. Cancer Res. 2009;69:8141–8149. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagakawa O, Akashi T, Hayakawa Y, Junicho A, Koizumi K, Fujiuchi Y, Furuya Y, Matsuda T, Fuse H, Saiki I. Differential expression of integrin subunits in DU-145/AR prostate cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2004;12:837–841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castoria G, D'Amato L, Ciociola A, Giovannelli P, Giraldi T, Sepe L, Paolella G, Barone MV, Migliaccio A, Auricchio F. Androgen-induced cell migration: role of androgen receptor/filamin A association. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17218. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lamb LE, Zarif JC, Miranti CK. The androgen receptor induces integrin alpha6beta1 to promote prostate tumor cell survival via NF-kappaB and Bcl-xL Independently of PI3K signaling. Cancer Res. 2011;71:2739–2749. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weaver VM, Petersen OW, Wang F, Larabell CA, Briand P, Damsky C, Bissell MJ. Reversion of the malignant phenotype of human breast cells in three-dimensional culture and in vivo by integrin blocking antibodies. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:231–245. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.1.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bissell MJ, Rizki A, Mian IS. Tissue architecture: the ultimate regulator of breast epithelial function. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:753–762. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hynes RO. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell. 2002;110:673–687. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miranti CK, Brugge JS. Sensing the environment: a historical perspective on integrin signal transduction. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:E83–E90. doi: 10.1038/ncb0402-e83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pelletier AJ, Kunicki T, Ruggeri ZM, Quaranta V. The activation state of the integrin alpha IIb beta 3 affects outside-in signals leading to cell spreading and focal adhesion kinase phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:18133–18140. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.30.18133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hungerford JE, Compton MT, Matter ML, Hoffstrom BG, Otey CA. Inhibition of pp125FAK in cultured fibroblasts results in apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:1383–1390. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.5.1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee GY, Kenny PA, Lee EH, Bissell MJ. Three-dimensional culture models of normal and malignant breast epithelial cells. Nat Methods. 2007;4:359–365. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chitcholtan K, Asselin E, Parent S, Sykes PH, Evans JJ. Differences in growth properties of endometrial cancer in three dimensional (3D) culture and 2D cell monolayer. Exp Cell Res. 2013;319:75–87. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu J, Wang R, Xie ZH, Odero-Marah V, Pathak S, Multani A, Chung LW, Zhau HE. Prostate cancer metastasis: role of the host microenvironment in promoting epithelial to mesenchymal transition and increased bone and adrenal gland metastasis. Prostate. 2006;66:1664–1673. doi: 10.1002/pros.20488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reichert JC, Quent VM, Burke LJ, Stansfield SH, Clements JA, Hutmacher DW. Mineralized human primary osteoblast matrices as a model system to analyse interactions of prostate cancer cells with the bone microenvironment. Biomaterials. 2010;31:7928–7936. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hall CL, Dai J, van Golen KL, Keller ET, Long MW. Type I collagen receptor (alpha 2 beta 1) signaling promotes the growth of human prostate cancer cells within the bone. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8648–8654. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grzesiak JJ, Bouvet M. Determination of the ligand-binding specificities of the alpha2beta1 and alpha1beta1 integrins in a novel 3-dimensional in vitro model of pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2007;34:220–228. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000250129.64650.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lynch CC, Hikosaka A, Acuff HB, Martin MD, Kawai N, Singh RK, Vargo-Gogola TC, Begtrup JL, Peterson TE, Fingleton B, Shirai T, Matrisian LM, Futakuchi M. MMP-7 promotes prostate cancer-induced osteolysis via the solubilization of RANKL. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:485–496. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Senger DR, Claffey KP, Benes JE, Perruzzi CA, Sergiou AP, Detmar M. Angiogenesis promoted by vascular endothelial growth factor: regulation through alpha1beta1 and alpha2beta1 integrins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:13612–13617. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mitchell K, Svenson KB, Longmate WM, Gkirtzimanaki K, Sadej R, Wang X, Zhao J, Eliopoulos AG, Berditchevski F, Dipersio CM. Suppression of integrin alpha3beta1 in breast cancer cells reduces cyclooxygenase-2 gene expression and inhibits tumorigenesis, invasion, and cross-talk to endothelial cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70:6359–6367. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van den Hoogen C, van der Horst G, Cheung H, Buijs JT, Pelger RC, van der Pluijm G. Integrin alphav expression is required for the acquisition of a metastatic stem/progenitor cell phenotype in human prostate cancer. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:2559–2568. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhau HY, Chang SM, Chen BQ, Wang Y, Zhang H, Kao C, Sang QA, Pathak SJ, Chung LW. Androgen-repressed phenotype in human prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:15152–15157. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mirtti T, Nylund C, Lehtonen J, Hiekkanen H, Nissinen L, Kallajoki M, Alanen K, Gullberg D, Heino J. Regulation of prostate cell collagen receptors by malignant transformation. Int J Canc Suppl J Int Canc Suppl. 2006;118:889–898. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jackstadt R, Roh S, Neumann J, Jung P, Hoffmann R, Horst D, Berens C, Bornkamm GW, Kirchner T, Menssen A, Hermeking H. AP4 is a mediator of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis in colorectal cancer. J Exp Med. 2013;210:1331–1350. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.〿: Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program. SEER*Stat Database, 1969–2007, National Cancer Institute, Surveillance Research Program, Cancer Statistics Branch 2010.http://www.seer.cancer.gov

- 46.Chu GC, Chung LW. RANK-mediated signaling network and cancer metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2014;33:497–509. doi: 10.1007/s10555-013-9488-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vogel W, Gish GD, Alves F, Pawson T. The discoidin domain receptor tyrosine kinases are activated by collagen. Mol Cell. 1997;1:13–23. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Valiathan RR, Marco M, Leitinger B, Kleer CG, Fridman R. Discoidin domain receptor tyrosine kinases: new players in cancer progression. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2012;31:295–321. doi: 10.1007/s10555-012-9346-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Samaha FF, Hibbard C, Sacks J, Chen H, Varello MA, George T, Kahn ML. Density of platelet collagen receptors glycoprotein VI and alpha2beta1 and prior myocardial infarction in human subjects, a pilot study. Med Sci Monit. 2005;11:CR224–CR229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang Y, Ding Y, Huang Y, Zhang C, Boquan J, Ran Z. Expression of leukocyte-associated immunoglobulin-like receptor-1 (LAIR-1) on osteoclasts and its potential role in rheumatoid arthritis. Clinics (Sao Paulo, Brazil) 2013;68:475–481. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2013(04)07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sheikh H, Yarwood H, Ashworth A, Isacke CM. Endo180, an endocytic recycling glycoprotein related to the macrophage mannose receptor is expressed on fibroblasts, endothelial cells and macrophages and functions as a lectin receptor. J Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 6):1021–1032. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.6.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.East L, Isacke CM. The mannose receptor family. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1572:364–386. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4165(02)00319-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sottnik JL, Daignault-Newton S, Zhang X, Morrissey C, Hussain MH, Keller ET, Hall CL. Integrin alpha(2)beta (1) (alpha (2)beta (1)) promotes prostate cancer skeletal metastasis. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2012;30:569–578. doi: 10.1007/s10585-012-9561-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Colombel M, Eaton CL, Hamdy F, Ricci E, van der Pluijm G, Cecchini M, Mege-Lechevallier F, Clezardin P, Thalmann G. Increased expression of putative cancer stem cell markers in primary prostate cancer is associated with progression of bone metastases. Prostate. 2012;72:713–720. doi: 10.1002/pros.21473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, Jacobsen A, Byrne CJ, Heuer ML, Larsson E, Antipin Y, Reva B, Goldberg AP, Sander C, Schultz N. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Canc Discov. 2012;2:401–404. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jung P, Menssen A, Mayr D, Hermeking H. AP4 encodes a c-MYC-inducible repressor of p21. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:15046–15051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801773105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schatzl G, Madersbacher S, Gsur A, Preyer M, Haidinger G, Haitel A, Vutuc C, Micksche M, Marberger M. Association of polymorphisms within androgen receptor, 5alpha-reductase, and PSA genes with prostate volume, clinical parameters, and endocrine status in elderly men. Prostate. 2002;52:130–138. doi: 10.1002/pros.10101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Holzbeierlein J, Lal P, LaTulippe E, Smith A, Satagopan J, Zhang L, Ryan C, Smith S, Scher H, Scardino P, Reuter V, Gerald WL. Gene expression analysis of human prostate carcinoma during hormonal therapy identifies androgen-responsive genes and mechanisms of therapy resistance. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:217–227. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63112-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Link KA, Balasubramaniam S, Sharma A, Comstock CE, Godoy-Tundidor S, Powers N, Cao KH, Haelens A, Claessens F, Revelo MP, Knudsen KE. Targeting the BAF57 SWI/SNF subunit in prostate cancer: a novel platform to control androgen receptor activity. Cancer Res. 2008;68:4551–4558. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Balasubramaniam S, Comstock CE, Ertel A, Jeong KW, Stallcup MR, Addya S, McCue PA, Ostrander WF, Jr, Augello MA, Knudsen KE. Aberrant BAF57 signaling facilitates prometastatic phenotypes. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:2657–2667. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thalmann GN, Anezinis PE, Chang SM, Zhau HE, Kim EE, Hopwood VL, Pathak S, von Eschenbach AC, Chung LW. Androgen-independent cancer progression and bone metastasis in the LNCaP model of human prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 1994;54:2577–2581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Grafahrend D, Heffels KH, Beer MV, Gasteier P, Moller M, Boehm G, Dalton PD, Groll J. Degradable polyester scaffolds with controlled surface chemistry combining minimal protein adsorption with specific bioactivation. Nat Mater. 2011;10:67–73. doi: 10.1038/nmat2904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hutmacher DW, Loessner D, Rizzi S, Kaplan DL, Mooney DJ, Clements JA. Can tissue engineering concepts advance tumor biology research? Trends Biotechnol. 2010;28:125–133. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hall CL, Dubyk CW, Riesenberger TA, Shein D, Keller ET, van Golen KL. Type I collagen receptor (alpha2beta1) signaling promotes prostate cancer invasion through RhoC GTPase. Neoplasia. 2008;10:797–803. doi: 10.1593/neo.08380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Huang WC, Zhau HE, Chung LW. Androgen receptor survival signaling is blocked by anti-beta2-microglobulin monoclonal antibody via a MAPK/lipogenic pathway in human prostate cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:7947–7956. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.092759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jia L, Kim J, Shen H, Clark PE, Tilley WD, Coetzee GA. Androgen receptor activity at the prostate specific antigen locus: steroidal and non-steroidal mechanisms. Mol Cancer Res. 2003;1:385–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nomura T, Huang WC, Zhau HE, Wu D, Xie Z, Mimata H, Zayzafoon M, Young AN, Marshall FF, Weitzmann MN, Chung LW. Beta2-microglobulin promotes the growth of human renal cell carcinoma through the activation of the protein kinase A, cyclic AMP-responsive element-binding protein, and vascular endothelial growth factor axis. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:7294–7305. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials