Abstract

Previous studies suggest that circulating 25(OH)D may favorably influence cardiorespiratory fitness and fat oxidation. However, these relationships have not been examined in older adult women of different ethnic groups. The objectives of this study were to determine whether serum 25(OH)D is related to cardiovascular fitness (VO2max) in sedentary women ages ≥60 years and to determine whether these associations differ between African Americans (AA) and European Americans (EA). A secondary aim was to determine whether serum 25(OH)D is correlated with respiratory quotient (RQ) during submaximal exercise. This cross-sectional analysis included 67 AA and EA women ages 60–74 years. VO2max was measured by a modified Bruce graded treadmill protocol, and measurements were adjusted for percent fat and lean body mass assessed by air displacement plethysmography. Indirect calorimetry was used to measure RQ at rest and during four submaximal exercise tests. Fasting blood samples were obtained to quantify serum 25(OH)D. Serum 25(OH)D was associated with VO2max (ml/kg LBM/min) independent of percent body fat (r = 0.316, p = 0.010). However, subgroup analysis revealed that this relationship was specific to AA (r = 0.727, p = 0.005 for AA; r = 0.064, p = 0.643 for EA). In all subjects combined, 25(OH)D was inversely correlated (p < 0.01) with all measures of submaximal RQ. Higher serum 25(OH)D was associated with greater cardiorespiratory fitness in older adult AA women. Among both AA and EA, inverse associations between serum 25(OH)D and RQ suggest that women with higher levels of circulating vitamin D also demonstrated greater fat oxidation during submaximal exercise.

Keywords: Vitamin D, Cardiorespiratory fitness, VO2max, Respiratory quotient, African Americans

Introduction

It is well-known that circulating levels of 25(OH)D, the accepted biomarker for vitamin D status, decline with age [1, 2]. Decreased 25(OH)D with advancing age is concerning in light of numerous studies relating low 25(OH)D with impairments in vascular function [3, 4] and cardiovascular health [5–7]. Although associations between vitamin D status and physical function in older adults have also been reported [8–11], few studies have examined the relationship between circulating 25(OH)D and cardiorespiratory fitness. Maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max) is considered a gold standard for assessment of cardiorespiratory fitness [12]. Previous studies have reported positive associations between VO2max and serum 25(OH)D in younger adults [13, 14] and adolescent boys [15], but whether VO2max is related to vitamin D status in older adult women is unknown. Like serum 25(OH)D, VO2max declines with age [16, 17]. Thus, it is of interest to determine whether the age-associated decrease in cardiorespiratory fitness may be related to concomitant decreases in circulating 25(OH)D.

Both circulating 25(OH)D [18, 19] and VO2max [20–22] are lower among African Americans (AA) compared to European Americans (EA). Although lower circulating 25(OH)D in AA has been associated with a greater prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors [23, 24] and vascular dysfunction [3, 25], no previous studies among AA have examined the possible relationship between 25(OH)D and VO2max.

Aging is also associated with an increased accrual of fat mass [26]. Circulating 25(OH)D levels are lower among obese versus non-obese individuals [27], and limited evidence suggests that vitamin D may affect fat oxidation [28, 29] and consequent weight gain [30, 31]. However, the relationship between serum 25(OH)D and substrate utilization during submaximal exercise has never been examined. Moreover, it is unknown whether ethnic differences exist in substrate oxidation and whether such differences may be related to vitamin D status.

In light of these gaps in the literature, the primary aims of this study were to examine whether serum 25(OH)D is associated with cardiorespiratory fitness in adult women ages 60 and older and to determine, whether these associations differ between AA and EA. A secondary aim was to determine whether serum 25(OH)D is related to respiratory quotient, an indicator of substrate utilization, during submaximal exercise.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 67 healthy women ages 60–74 years. All of the women were sedentary, defined by report of no regular exercise beyond once per week during the previous year. Participants were self-described as either AA or EA with both parents and grandparents of the same ethnic group. Exclusion criteria included smoking, abnormal electrocardiogram measures, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, thyroid dysfunction, or medications known to affect energy expenditure, glucose homeostasis, or heart rate. One hundred four women were originally recruited for this analysis, but inclusion was limited to those who met the criteria for attainment of maximal oxygen uptake as described below. All participants provided written consent, and the protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB).

Assessment of cardiorespiratory function and respiratory quotient (RQ)

Maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max) was measured using a modified Bruce graded treadmill protocol [32, 33]. Oxygen consumption (VO2) and carbon dioxide production (VCO2) were measured continuously using an open-circuit metabolic cart (Model #2900; SensorMedics, Yorba Linda, CA). Heart rate was measured using a 12 lead electrocardiogram. Attainment of VO2max was defined by standard criteria [12]: heart rate within 90 % of the age-predicted maximum (220 – age), respiratory quotient (RQ) >1.1, and a plateauing of VO2 (<1.0 ml/kg/min) increase in oxygen uptake with an increase in workload). Subjects met at least 2 out of 3 criteria. This protocol is known to produce highly reproducible measures of VO2max and is considered a robust measure of aerobic capacity and cardiorespiratory fitness in older adult women [33].

On three consecutive mornings after an overnight fast, resting RQ was assessed by indirect calorimetry via an open-circuit metabolic cart (Delta Trac II; SensorMedics, Yorba Linda, CA) [34]. Measurements were obtained after a 15 min rest period in a supine position. VO2 and VCO2 were recorded each minute for 30 min. Final analysis excluded the first 10 min of testing. The averages of VO2 and VCO2 were calculated, and resting RQ was recorded as the ratio of VCO2/VO2.

RQ and VO2 were also obtained during minute 4 of submaximal exercise tests. Submaximal tests included stair climbing (7” step, 60 steps/min), walking on a treadmill at 3 mph at a 0 % grade, walking 3 mph at a 2.5 % grade, and walking 2 mph while carrying a box weighing 30 % of the participant's maximum isometric elbow flexion strength.

Measurement of body composition

Body composition was determined by whole-body air displacement plethysmography using the BOD POD Body Composition System (LIFE Measurement Instruments, Concord, CA). This method uses air displacement to determine body volume, and body volume is then used in standardized equations to calculate body density, percent fat, and lean body mass [35].

Measurement of vitamin D

Fasted blood samples were obtained for measurement of 25(OH)D. Laboratory analysis was conducted in the Core Laboratory of UAB's Diabetes and Research Training Center and Nutrition and Obesity Research Center. Serum 25(OH)D was quantified by IDS ELISA plates (Immuno Diagnostic Systems, Fountain Hills, AZ) with a volume size of 25 μl in duplicate. Minimum sensitivity is 6.8 nmol/l, inter-assay coefficient of variation (CV) is 4.94 %, and intra-assay CV is 4.83 %.

Statistical analysis

Serum 25(OH)D was log10 transformed prior to analyses due to non-normal distribution. Differences between ethnic groups were determined by independent t tests. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to identify differences in age as this variable was non-normally distributed after log transformation. Associations between variables of interest were examined by simple Pearson correlations and by partial correlations with adjustments for percent fat and ethnic group. Statistical tests were performed using SPSS software version 21.0 (Chicago, IL 2012). All tests were two-sided with a Type I error rate of 0.05.

Results

Table 1 displays participant characteristics as mean ± standard deviation (SD). AA and EA were similar in age and percent body fat. Consistent with previous studies [36, 37], AA had significantly more lean body mass than EA. VO2max is expressed relative to body weight (ml/kg/min) and lean body mass (ml/kg LBM/min). Both VO2max and serum 25(OH)D were significantly lower in AA compared to EA.

Table 1. Participant Characteristics (n = 67) (mean ± SD).

| Total cohort (n = 67) |

European American (n = 54) |

African American (n = 13) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 64.76 ± 3.68 | 65.10 ± 3.88 | 63.33 ± 2.30 | 0.188 |

| Weight (kg) | 73.73 ± 10.82 | 72.82 ± 11.23 | 77.51 ± 8.21 | 0.162 |

| Height (cm) | 165.29 ± 5.05 | 166.05 ± 4.93 | 162.11 ± 4.37 | 0.010 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.01 ± 3.87 | 26.40 ± 3.79 | 29.53 ± 3.23 | 0.008 |

| Lean body mass (kg) | 41.32 ± 4.10 | 40.73 ± 3.88 | 43.79 ± 4.21 | 0.015 |

| Total body fat (kg) | 31.75 ± 7.82 | 31.43 ± 8.08 | 33.09 ± 6.71 | 0.496 |

| Percent body fat | 42.87 ± 5.63 | 42.90 ± 5.68 | 42.72 ± 5.64 | 0.920 |

| Serum 25(OH)D (ng/ml) | 30.87 ± 11.85 | 32.77 ± 12.06 | 22.94 ± 6.76 | 0.003 |

| VO2max (ml/kg/min) | 22.84 ± 4.77 | 23.56 ± 3.91 | 19.86 ± 6.79 | 0.011 |

| VO2max (ml/kg LBM/min) | 40.02 ± 7.56 | 41.44 ± 6.76 | 34.09 ± 8.09 | 0.001 |

Bold values indicate significant differences between groups (p < 0.05)

BMI body mass index, LBM lean body mass

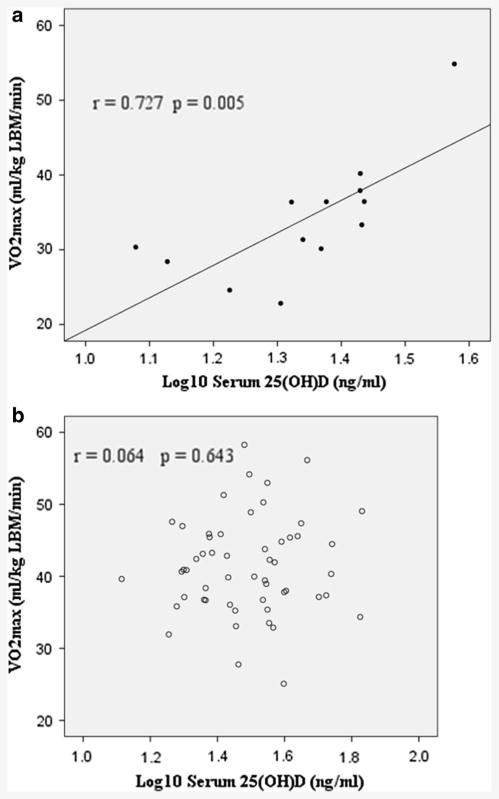

VO2max was positively associated with serum 25(OH)D even after adjustment for percent fat (Table 2). After adjustment for ethnic group, however, correlations between VO2max and 25(OH)D were not significant (data not shown). Subgroup analysis revealed that the correlation between VO2max and 25(OH)D was specific to AA, i.e. significant (both unadjusted and adjusted for percent fat) for AA (Fig. 1a) but not EA (Fig. 1b).

Table 2. Correlations between serum 25(OH)D and VO2 [r (p value)] (n = 67).

| Measure | Pearson correlation | Partial correlation adjusted for percent fat |

|---|---|---|

| VO2max (ml/kg/min) | 0.344 (0.004) | 0.303 (0.014) |

| VO2max (ml/kg LBM/min) | 0.304 (0.012) | 0.316 (0.010) |

| Step submax VO2 | 0.078 (0.532) | 0.093 (0.459) |

| 2 mph walk submax VO2 | −0.019 (0.876) | −0.009 (0.944) |

| Graded walk submax VO2 | −0.027 (0.828) | −0.021 (0.866) |

| Carry walk submax VO2 | 0.125 (0.316) | 0.090 (0.477) |

Bold values indicate statistically significant correlations (p < 0.05)

Fig. 1.

a Association between serum 25(OH)D and VO2max among African American women. b Association between serum 25(OH)D and VO2max among European American women

Although serum 25(OH)D was not significantly correlated with resting RQ, inverse associations were observed between 25(OH)D and all measures of submaximal RQ. The associations remained significant after adjustment for VO2max, percent fat, and ethnic group (Table 3).

Table 3. Correlations between serum 25(OH)D and respiratory quotient (RQ) [r (p value)] (n = 67).

| Pearson correlations | Partial correlations adjusted for VO2max (ml/kg LBM/min) and percent fat | Partial correlations adjusted VO2max (ml/kg LBM/min)and ethnic group | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resting RQ | −0.147 (0.234) | −0.234 (0.063) | −0.199 (0.115) |

| Step submax RQ | −0.546 (<0.001) | −0.479 (<0.001) | −0.517 (<0.001) |

| 2mph walk submax RQ | −0.316 (0.009) | −0.346 (0.005) | −0.315 (0.011) |

| Graded walk submax RQ | −0.430 (<0.001) | −0.388 (0.002) | −0.386 (0.002) |

| Carry walk submax RQa | −0.396 (0.001) | −0.404 (0.001) | −0.343 (0.005) |

Bold values indicate statistically significant correlations (p < 0.05)

n = 66

Discussion

Few studies have investigated the relationship between serum 25(OH)D and cardiorespiratory fitness. However, this relationship is particularly relevant to older adult women as cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in this population [38], and both circulating 25(OH)D [1, 2] and cardiovascular fitness [16, 17] tend to decline with age. A novel observation of this study was the association between serum 25(OH)D and VO2max in AA specifically, independent of body composition. Vitamin D status also appeared to influence substrate oxidation, such that serum 25(OH)D was inversely correlated with all measures of RQ during submaximal exercise. These inverse associations were independent of ethnic group, body composition, and VO2max.

The first major finding of this study was the observation that AA women with higher serum 25(OH)D demonstrated greater cardiovascular fitness as measured by VO2max. Maximum oxygen consumption (VO2max) is considered a gold standard measure of cardiovascular endurance, signifying the body's ability to utilize oxygen at the tissue level [12]. Previous studies have reported associations between circulating 25(OH)D and VO2max in younger men and women [13, 14] and adolescent boys [15]. Similarly, positive associations have been reported between vitamin D status and other measures of cardiovascular fitness among a cohort of 1,320 women of average age 46 years [39] and patients with chronic kidney disease [40]. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine ethnic differences in this relationship among older adult women specifically. By expressing VO2max as ml/kg LBM/min and adjusting for percent fat, we were able to account for differences in body composition among the women. Because all of the women were sedentary, it is also unlikely that habitual physical activity influenced the results. Consistent with previous reports [18–22], AA women in this cohort had both lower circulating 25(OH)D and lower VO2max compared to EA, and the present results are suggestive that these two measures are interrelated.

Vitamin D insufficiency has repeatedly been associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular disease [5, 6, 41, 42]. Vitamin D receptors are widespread throughout the body and are present on vascular smooth muscle cells, endothelium, and cardiomyocytes [3, 6]. Accordingly, low levels of 25(OH)D have been correlated with arterial stiffness and worsened vascular endothelial function [3]. In a study of 45 EA and AA, men and women ages 18–50 years, serum 25(OH)D was correlated with multiple measures of vascular function, and the correlations were stronger among AA. AA in the study had more vascular dysfunction than EA, but ethnic differences were attenuated after adjustment for serum 25(OH)D [25]. Although speculative, it is plausible that the mechanism underlying the association between 25(OH)D and cardiorespiratory fitness may involve effects of vitamin D on endothelial function. Vitamin D receptors have also been identified in skeletal muscle cells [42, 43]. By binding to its intracellular receptor and acting as a transcription factor, vitamin D may regulate a variety of genes within muscle. It also appears to elicit more rapid non-genomic effects on skeletal muscle through cell-signaling cascades [42–44]. Although the exact effects of vitamin D on skeletal muscle have not been elucidated, vitamin D insufficiency has been associated with impaired skeletal muscle function [43, 45, 46]. Thus, vitamin D's effects on skeletal muscle function may in turn relate to its effects on VO2max. As observed in this study, population means for serum 25(OH)D are lower among AA compared to EA [47]. Perhaps improving vitamin D status, particularly among older AA women, could help to alleviate health disparities in cardiovascular disease risk [47, 48].

Among participants of both ethnic groups, serum 25(OH)D was inversely related to various measures of submaximal RQ. RQ is the ratio of VCO2/VO2, and the measure of RQ can provide a rudimentary estimate of substrate oxidation [49]. In a fasted steady state, the normal physiological range of RQ is 0.7–1.0. An RQ at the lower end of the range represents greater fat oxidation while an RQ of 1.0 would signify greater carbohydrate oxidation [50]. Thus, the consistent inverse associations observed between serum 25(OH)D and RQ in this study is indicative of greater fat oxidation during submaximal steady state exertion with higher levels of circulating vitamin D. Although studies relating vitamin D to substrate oxidation in humans are few, one crossover study demonstrated significantly higher rates of fat oxidation following a breakfast meal high in calcium and vitamin D compared to a meal low in calcium and vitamin D [29]. In another weight loss intervention among 24 overweight women ages 18–31, serum 25(OH)D at baseline was predictive of increased postprandial energy expenditure over 12 weeks (p = 0.004), and baseline 25(OH)D showed a trend toward increased postprandial fat oxidation (p = 0.06) [28]. Collectively, these studies suggest that circulating 25(OH)D may favorably influence fat oxidation.

The present study demonstrates for the first time that the relationship between vitamin D status and fat oxidation may be most pronounced during periods of submaximal exercise. It is well-established that 25(OH)D levels are lower with obesity, and this is thought to be due to sequestering of vitamin D by adipocytes [27]. However, it is also possible that vitamin D may favorably influence fat metabolism. Several weight loss interventions have reported enhanced weight loss with higher intakes of dairy foods [30], and evidence suggests that increases in circulating 25(OH)D from increased dairy consumption may be partially responsible. Among 126 overweight men and women ages 40–65, increased dairy intake and consequent increases in serum 25(OH)D from baseline to month 6 were associated with greater weight loss [31]. In another cohort of 4,659 women ages 65 and older, higher blood levels of 25(OH)D at baseline were predictive of less weight gain over a 4.5 year follow-up [51]. Previous studies in mice also provide evidence for a role of vitamin D in fat oxidation [52, 53].

This study was limited by its cross-sectional design and modest sample size, particularly among the AA group. In addition, because the dietary supplements were not considered, serum 25(OH)D is reflective of vitamin D from all sources. However, the study was strengthened by robust measures of body composition and cardiovascular fitness. Although the results may not be extrapolated to other groups as the cohort included only older adult women, this is a group highly likely to be affected by lower cardiovascular fitness and vitamin D insufficiency.

In conclusion, this cross-sectional analysis demonstrated that higher serum 25(OH)D was associated with greater cardiorespiratory fitness in healthy AA women ages 60 and older. Although these results suggest that greater cardiovascular fitness among EA compared to AA may be mediated in part by higher levels of 25(OH)D, future studies are needed to confirm underlying mechanisms and to determine whether improvement in vitamin D status may lead to improved cardiovascular fitness and decreased cardiovascular disease risk among AA. The observation that older adult women with higher serum 25(OH)D appear to experience greater fat oxidation during submaximal exercise also warrants further investigation to determine whether ensuring adequate vitamin D status along with exercise interventions may be a practical method to combat age-related weight gain.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by 5 UL1 RR025777. DK 056336, UL1 TR000165, R01 AG27084. The authors are grateful to Paul Zuckerman for study coordination, David Bryan for exercise testing, Robert Petri for body composition testing, and Maryellen Williams and Cindy Zeng for laboratory analysis.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Amy C. Ellis, Email: aellis@ches.ua.edu, Department of Human Nutrition, University of Alabama, 405 Russell Hall, Tuscaloosa, AL 35487, USA.

Jessica A. Alvarez, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, USA

Barbara A. Gower, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, USA

Gary R. Hunter, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, USA

References

- 1.Bischoff-Ferrari H, Stähelin HB, Walter P. Vitamin D effects on bone and muscle. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 2011;81:264–272. doi: 10.1024/0300-9831/a000072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morley J. Vitamin D redux. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2009;10:591–592. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2009.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al Mheid I, Patel R, Murrow J, et al. Vitamin D status is associated with arterial stiffness and vascular dysfunction in healthy humans. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:186–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.02.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giallauria F, Milaneschi Y, Tanaka T, et al. Arterial stiffness and vitamin D levels: the Baltimore longitudinal study of aging. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:3717–3723. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang L, Song Y, Manson JE, et al. Circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D and risk of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5:819–829. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.112.967604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang TJ, Pencina MJ, Booth SL, et al. Vitamin D deficiency and risk of cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2008;117:503–511. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.706127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scragg RK, Camargo CA, Simpson R. Relation of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D to heart rate and cardiac work (from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys) Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.08.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Houston DK, Tooze JA, Davis CC, et al. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and physical function in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study All Stars. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1793–1801. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03601.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Houston D, Cesari M, Ferrucci L, et al. Association between vitamin D status and physical performance: the InCHIANTI study. J Gerontol A. 2007;62:440–446. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.4.440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scott D, Blizzard L, Fell J, Ding C, Winzenberg T, Jones G. A prospective study of the associations between 25-hydroxyvitamin D, sarcopenia progression, and physical activity in older adults. Clin Endocrinol. 2010;73:581–587. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2010.03858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mowe' M, Haug E, Bøhmer T. Low serum calcidiol concentration in older adults with reduced muscular function. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:220–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb04581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noonan V, Dean E. Submaximal exercise testing: clinical application and interpretation. Phys Ther. 2000;80:782–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ardestani A, Parker B, Mathur S, et al. Relation of vitamin D level to maximal oxygen uptake in adults. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:1246–1249. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mowry DA, Costello MM, Heelan KA. Association among cardiorespiratory fitness, body fat, and bone marker measurements in healthy young females. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2009;109:534–539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valtueña J, Gracia-Marco L, Huybrechts I, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness in males, and upper limbs muscular strength in females, are positively related with 25-hydroxyvitamin D plasma concentrations in European adolescents: the HELENA study. QJM. 2013 doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hct089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ogawa T, Spina RJ, Martin WH, et al. Effects of aging, sex, and physical training on cardiovascular responses to exercise. Circulation. 1992;86:494–503. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.2.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siconolfi SF, Lasater TM, McKinlay S, Boggia P, Carleton RA. Physical fitness and blood pressure: the role of age. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;122:452–457. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wright NC, Chen L, Niu J, et al. Defining physiologically “normal” vitamin D in African Americans. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23:2283–2291. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1877-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freedman BI, Register TC. Effect of race and genetics on vitamin D metabolism, bone and vascular health. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2012;8:459–466. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2012.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang CY, Haskell WL, Farrell SW, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness levels among US adults 20–49 years of age: findings from the 1999–2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171:426–435. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arena R, Fei DY, Arrowood JA, Kraft KA. Influence on aerobic fitness on aortic stiffness in apparently healthy Caucasian and African–American subjects. Int J Cardiol. 2007;122:202–206. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.11.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pivarnik JM, Bray MS, Hergenroeder AC, Hill RB, Wong WW. Ethnicity affects aerobic fitness in US adolescent girls. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995;27:1635–1638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scragg R, Sowers M, Bell C. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D, ethnicity, and blood pressure in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Hypertens. 2007;20:713–719. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fiscella K, Winters P, Tancredi D, Franks P. Racial disparity in blood pressure: is vitamin D a factor? J Gen Intern Med. 2011;27:1105–1111. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1707-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alvarez JA, Gower BA, Calhoun DA, et al. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and ethnic differences in arterial stiffness and endothelial function. J Clin Med Res. 2012;4:197–205. doi: 10.4021/jocmr965w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Villareal DT, Apovian CM, Kushner RF, Klein S. Obesity in older adults: technical review and position statement of the American Society for Nutrition and NAASO, The Obesity Society. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:923–934. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.5.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moreno LA, Valtueña J, Pérez-López F, González-Gross M. Health effects related to low vitamin D concentrations: beyond bone metabolism. Ann Nutr Metab. 2011;59:22–27. doi: 10.1159/000332070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Teegarden D, White KM, Lyle RM, et al. Calcium and dairy product modulation of lipid utilization and energy expenditure. Obesity. 2008;16:1566–1572. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ping-Delfos WC, Soares M. Diet induced thermogenesis, fat oxidation and food intake following sequential meals: influence of calcium and vitamin D. Clin Nutr. 2011;30:376–383. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soares MJ, Murhadi LL, Kurpad AV, Chan She Ping-Delfos WL, Piers LS. Mechanistic roles for calcium and vitamin D in the regulation of body weight. Obes Rev. 2012;13:592–605. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2012.00986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shahar DR, Schwarzfuchs D, Fraser D, et al. Dairy calcium intake, serum vitamin D, and successful weight loss. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92:1017–1022. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bruce RA. Methods of exercise testing. Step test, bicycle, treadmill, isometrics. Am J Cardiol. 1974;33:715–720. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(74)90211-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fielding RA, Frontera WR, Hughes VA, Fisher EC, Evans WJ. The reproducibility of the Bruce protocol exercise test for the determination of aerobic capacity in older women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1997;29:1109–1113. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199708000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Compher C, Frankenfield D, Keim N, Roth-Yousey L. Best practice methods to apply to measurement of resting metabolic rate in adults: a systematic review. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106:881–903. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fields DA, Hunter GR. Monitoring body fat in the elderly: application of air-displacement plethysmography. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2004;7:11–14. doi: 10.1097/00075197-200401000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wagner DR, Heyward VH. Measures of body composition in blacks and whites: a comparative review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71:1392–1402. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.6.1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gasperino J. Ethnic differences in body composition and their relation to health and disease in women. Ethn Health. 1996;1:337–347. doi: 10.1080/13557858.1996.9961803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bybee KA, Stevens TL. Matters of the heart: cardiovascular disease in U.S. women. Mo Med. 2013;110:65–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Farrell SW, Willis BL. Cardiorespiratory fitness, adiposity, and serum 25-dihydroxyvitamin D levels in women: the Cooper Center Longitudinal Study. J Womens Health. 2012;21:80–86. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Petchey WG, Howden EJ, Johnson DW, Hawley CM, Marwick T, Isbel NM. Cardiorespiratory fitness is independently associated with 25-hydroxyvitamin D in chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:512–518. doi: 10.2215/CJN.06880810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Skaaby T, Husemoen LL, Pisinger C, et al. Vitamin D status and incident cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality: a general population study. Endocrine. 2013;43:618–625. doi: 10.1007/s12020-012-9805-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wacker M, Holick MF. Vitamin D: effects on skeletal and extraskeletal health and the need for supplementation. Nutrients. 2013;5:111–148. doi: 10.3390/nu5010111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hamilton B. Vitamin D and human skeletal muscle. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2010;20:182–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.01016.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ceglia L. Vitamin D and its role in skeletal muscle. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2009;12:628–633. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328331c707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cianferotti L, Brandi ML. Muscle–bone interactions: basic and clinical aspects. Endocrine. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s12020-013-0026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shuler FD, Wingate MK, Moore GH, Giangarra C. Sports health benefits of vitamin D. Sports Health. 2012;4:496–501. doi: 10.1177/1941738112461621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grant WB, Peiris AN. Possible role of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D in black–white health disparities in the United States. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2010;11:617–628. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weishaar T, Vergili JM. Vitamin D status is a biological determinant of health disparities. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113:643–651. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Severi S, Malavolti M, Battistini N, Bedogni G. Some applications of indirect calorimetry to sports medicine. Acta Diabetol. 2001;38:23–26. doi: 10.1007/s005920170024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Da Rocha EE, Alves VG, Da Fonseca RB. Indirect calorimetry: methodology, instruments and clinical application. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2006;9:247–256. doi: 10.1097/01.mco.0000222107.15548.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Leblanc ES, Rizzo JH, Pedula KL, et al. Associations between 25-hydroxyvitamin D and weight gain in elderly women. J Womens Health. 2012;10:1066–1073. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.3506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wong KE, Szeto FL, Zhang W, et al. Involvement of the vitamin D receptor in energy metabolism: regulation of uncoupling proteins. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;296:E820–E828. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90763.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wong KE, Kong J, Zhang W, et al. Targeted expression of human vitamin D receptor in adipocytes decreases energy expenditure and induces obesity in mice. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:33804–33810. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.257568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]