Abstract

Background

The aging gene p66Shc, is an important mediator of oxidative stress-induced vascular dysfunction and disease. In cultured human aortic endothelial cells (HAEC), p66Shc deletion increases endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) expression and nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability via protein kinase B. However, the putative role of the NO pathway on p66Shc activation remains unclear. This study was designed to elucidate the regulatory role of the eNOS/NO pathway on p66Shc activation.

Methods and Results

Incubation of HAEC with oxidized low density lipoprotein (oxLDL) led to phosphorylation of p66Shc at Ser-36, resulting in an enhanced production of superoxide anion (O2 -). In the absence of oxLDL, inhibition of eNOS by small interfering RNA or L-NAME, induced p66Shc phosphorylation, suggesting that basal NO production inhibits O2 - production. oxLDL-induced, p66Shc-mediated O2- was prevented by eNOS inhibition, suggesting that when cells are stimulated with oxLDL eNOS is a source of reactive oxygen species. Endogenous or exogenous NO donors, prevented p66Shc activation and reduced O2- production. Treatment with tetrahydrobiopterin, an eNOS cofactor, restored eNOS uncoupling, prevented p66Shc activation, and reduced O2- generation. However, late treatment with tetrahydropterin did not yield the same result suggesting that eNOS uncoupling is the primary source of reactive oxygen species.

Conclusions

The present study reports that in primary cultured HAEC treated with oxLDL, p66Shc-mediated oxidative stress is derived from eNOS uncoupling. This finding contributes novel information on the mechanisms of p66Shc activation and its dual interaction with eNOS underscoring the importance eNOS uncoupling as a putative antioxidant therapeutical target in endothelial dysfunction as observed in cardiovascular disease.

Introduction

Endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) produces nitric oxide (NO), a key factor involved in maintaining endothelial homeostasis [1]. Further, NO plays a key role in preventing endothelial dysfunction by scavenging O2- [2], reducing adhesion of platelets and leukocytes [3], and inhibiting migration and proliferation of smooth muscle cells [4]. However, under pathological conditions eNOS can become a source of reactive oxygen species [5], [6], [7]. The underlying mechanisms of this switch include oxidization of tetrahydrobiopterin [5], depletion of tetrahydrobiopterin [8], and dephosphorylation of eNOS at Thr495 [9].

The p66Shc adaptor protein is an important mediator of oxidative stress-induced vascular dysfunction [10], acting as a redox enzyme implicated in mitochondrial ROS generation and the translation of oxidative signals into apoptosis [11], [12], [13], [14], [15]. Genetic deletion of p66Shc in the mouse extends lifespan by reducing the production of intracellular oxidants [16] and in ApoE−/− mice treated with high fat diet limits atherosclerotic plaque formation due to decreased lipid peroxidation [17]. Previous studies reported that in human aortic endothelial cells oxidized LDL increases ROS production via phosphorylation of the p66Shc protein at ser36 through the lectin-like oxLDL receptor-1, activation of protein kinase C beta-2, and c-Jun N-terminal kinase [18]; of note, this effect can be prevented by p66Shc silencing. These results underscored the critical role of p66Shc in oxLDL-induced oxidative stress in endothelial cells [18]. Indeed, activation of p66Shc leads to a surge of reactive oxygen species from mitochondria [16], [19] and/or via NADPH oxidase [18], [20].

Further, it has been reported that p66Shc overexpression inhibits eNOS-dependent NO production [21], while deletion of p66Shc leads to increased phosphorylation of eNOS at the activatory phosphorylation site Ser1177 through the protein kinase B pathway [22]. These findings imply an important role of p66Shc adaptor protein in modulating endothelium-derived NO production [22]. On the other hand, the role of endothelium-derived NO in controlling p66Shc activation remained not known. The present study was therefore designed to study the effects of eNOS, as well as NO, on the expression of the p66Shc adaptor protein.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture experiments

Primary human aortic endothelial cells (HAEC; Clonetics, Allschwil, Switzerland), from passage 4 to 6, were used. The cells were cultured and passaged in EBM-2 medium supplied with EGM-2 bulletkit (Clonetics, Walkersville USA). Experiments were performed in EBM medium with 0.5% FBS. Cells were harvested for further measurements (Western blotting, superoxide production measurement) either within 60 minutes or after 24 hours of exposure to oxLDL. NO donors or inhibitors were added to medium 60 minutes before exposure of the cells to oxLDL. Tetrahydrobiopterin was added to the medium 60 minutes prior to (Before, B), 45 minutes (After Early, AE) or 16 hours (After Later, AL) after the oxLDL stimulation.

Materials

Apocynin was purchased from SAFC (Saint. Louis, MO, USA). 8-Bromoguanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate, bradykinin, calcium ionophore (A23187), N (G)-nitro-L- arginine methyl ester (L-NAME), ODQ, tetrahydrobiopterin, siRNA against eNOS and N-TER Nanoparticle siRNA Transfection system, and anti-α-tubulin antibody were obtained from Sigma (Saint Louis, MO, USA). Anti-Shc/p66 (pSer36) antibody was purchased from Calbiochem (Darmstadt, Germany). DETA NONOate, DEA NONOate, and KT5823 were purchased from Cayman (Michigan, USA). Oxidized LDL and LDL are bought from Biomedical Technologies (Stoughton, MA, USA). Anti-Shc antibody was purchased from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA, USA). Anti-eNOS antibody was bought from B&D transduction laboratories (NJ, USA). Anti-rabbit and Anti-mouse second antibodies were bought from GE healthcare (Buckinghamshire, UK).

Measurement of reactive oxygen species

O2 - generation in intact cells was assessed using the spin trap 1-hydroxy-3-methoxycarbonyl-2,2,5,5-tetramethyl-pyrrolidine (CMH). Human aortic endothelial cells were collected in Krebs-HEPES solution containing diethyldithiocarbonic acid sodium salt (DETC 5 uM), deferoxamine (25 uM), and CMH (200 µM). The formation of the stable spin label 3-methoxycarbonyl-proxyl (CM') was determined at room temperature with an EMX ESR spectrometer (Bruker, Bremen Germany).

Western blotting

Protein expression was determined by Western blot analysis. Samples from cell culture were collected in lysis buffer (NaCl 150 mM, EDTA 1 mM, NaF 1 mM, DTT 1 mM, aprotinin 10 µg/µl, leupeptin 10 µg/µl, Na3VO4 0.1 mM, PMSF 1 mM, and NP-40 0.5%). Proteins were loaded on a separating gel (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane by semidry transfer. The membranes were incubated with antibody. Related signals were quantified using a Scion image software (Scion Corporation, Frederick, Maryland, USA).

Small interfering RNA (siRNA)

In certain experiments, predesigned small interfering RNA (siRNA) against eNOS (5′-CCUACAUCUGCAACCACAU[dT][dT]-3′; 10 nM) (Sigma, Saint Louis, MO, USA) were applied. HAEC were transfected with siRNA against eNOS at final concentration of 10 nM in a serum-free medium using N-TER Nanoparticle siRNA Transfection System (NFS, Sigma, Saint Louis, MO, USA), according to the manufacture's protocol. Cells were incubated with siRNA in serum-free and antibiotics-free medium for four hours, followed by normal growth medium for another 24 hours prior to the experiments. Nanoparticle Formation Solution (NFS) and scrambled siGAPDH (5′-GGUUUACAUGUUCCAAUAU[dT][dT]-3′; 10 nM) were used as negative controls.

Data analysis

Data are presented as means±SEM, Statistical analysis was performed by one–way ANOVA followed by a post hoc comparison using the Bonferroni test (Prism, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Differences were considered to indicate statistically significant when the P value was less than 0.05.

Results

1. oxLDL induces p66Shc adaptor protein phosphorylation and eNOS uncoupling

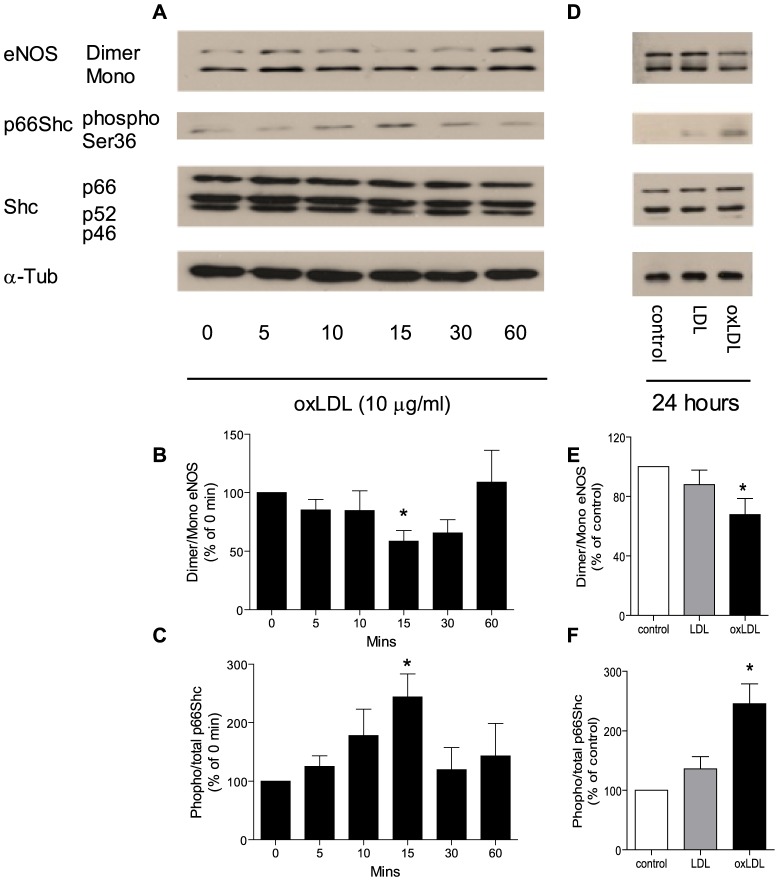

In HAEC, incubation with oxLDL (10 µg/ml) induced a transient phosphorylation of p66Shc at the Ser-36 amino acid residue. Nonetheless, total protein levels of p66Shc, as well as that of the other two isoforms of the Shc adaptor protein family, p52Shc and p46Shc, did not change within 60 minutes. In parallel, oxLDL transiently reduced the dimer/monomor ratio of eNOS within 60 minutes ( Figure 1 A, B, and C ).

Figure 1. Representive Western blot (A, D) and densitometric quantification of eNOS uncoupling (B, E) and phospho-p66Shc protein (C, F) expression in HAEC treated with oxLDL within sixty minutes (A, B, C) or for twenty four hours (D, E, F).

eNOS uncoupling was presented as ratio of dimer/monomer form of eNOS. The phosphorylation of p66Shc was normalized to total p66Shc protein and total p66Shc was normalized to α-tubulin. Results are presented as means±SEM; n = 6. * p<0.05 vs. cells at 0 minutes or cells under control condition.

In line with our previous findings [18], phosphorylation of p66Shc was also detectable after 24 hours of incubation of the cells with oxLDL (10 µg/ml). After 24 hours, eNOS dimer/monomor ratio was once again reduced, while compared to cells under control condition or treated with native LDL (10 µg/ml), denoting a biphasic response ( Figure 1 D, E, and F ).

2. eNOS plays a dual role for p66Shc phosphorylation

2.1 Inhibition of eNOS enhances p66Shc phosphorylation under basal condition, but reduces p66Shc phosphorylation under stimulated condition

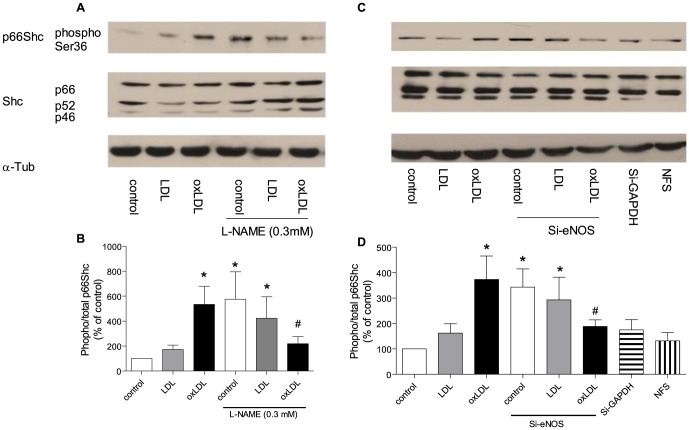

After 24 hours of exposure to oxLDL, p66Shc phosphorylation was increased in cells treated with L-NAME or L-NAME combined with native LDL. However in the presence of L-NAME, oxLDL-induced p66Shc phosphorylation was significantly reduced ( Figure 2 A, B ).

Figure 2. Representive Western blot (A, C) and densitometric quantification of phospho-p66Shc protein expression (B, D) in HAEC after twenty-four hours of incubation with oxLDL in the presence of nitric oxide synthase inhibitor (L-NAME 0.3 mM; A and B) and in the presence of eNOS siRNA (10 nM, C and D).

The phosphorylation of p66Shc was normalized to total p66Shc protein and total p66Shc was normalized to α-tubulin. Results are presented as means±SEM; n = 8. * p<0.05 vs. cells under control conditions. # p<0.05 vs. oxLDL alone. (NFS: nanoparticle formation solution).

To further corroborate the findings with L-NAME treatment, small interfering RNA against eNOS (Si-eNOS, Figure S1) were used. In line with the pharmacologic inhibition of eNOS, siRNA induced a significantly higher level of phosphorylated p66Shc under quiescent condition. Furthermore, phosphorylation of p66Shc was reduced when cells were exposed to both oxLDL and Si-eNOS ( Figure 2 C, D ).

2.2 Activation of Nitric oxide pathway prevents p66Shc phosphorylation

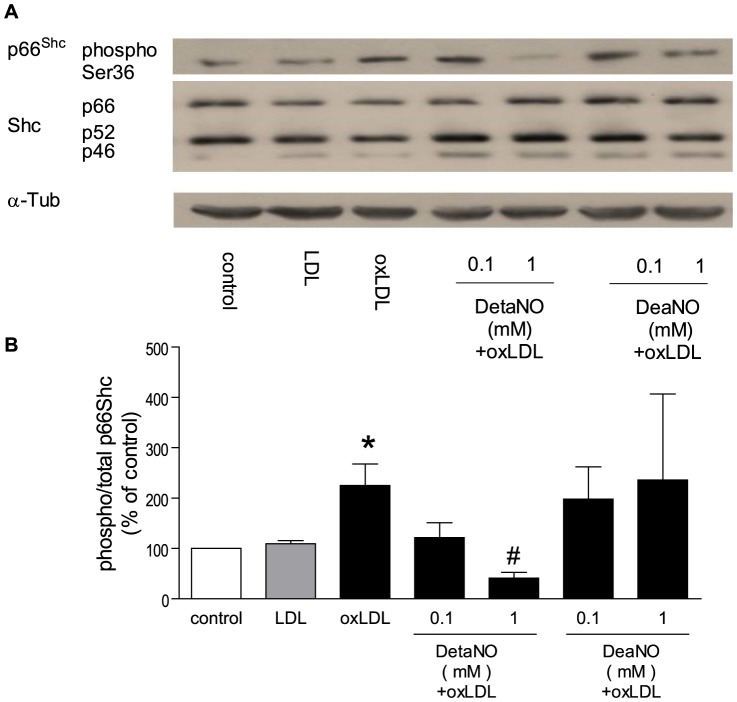

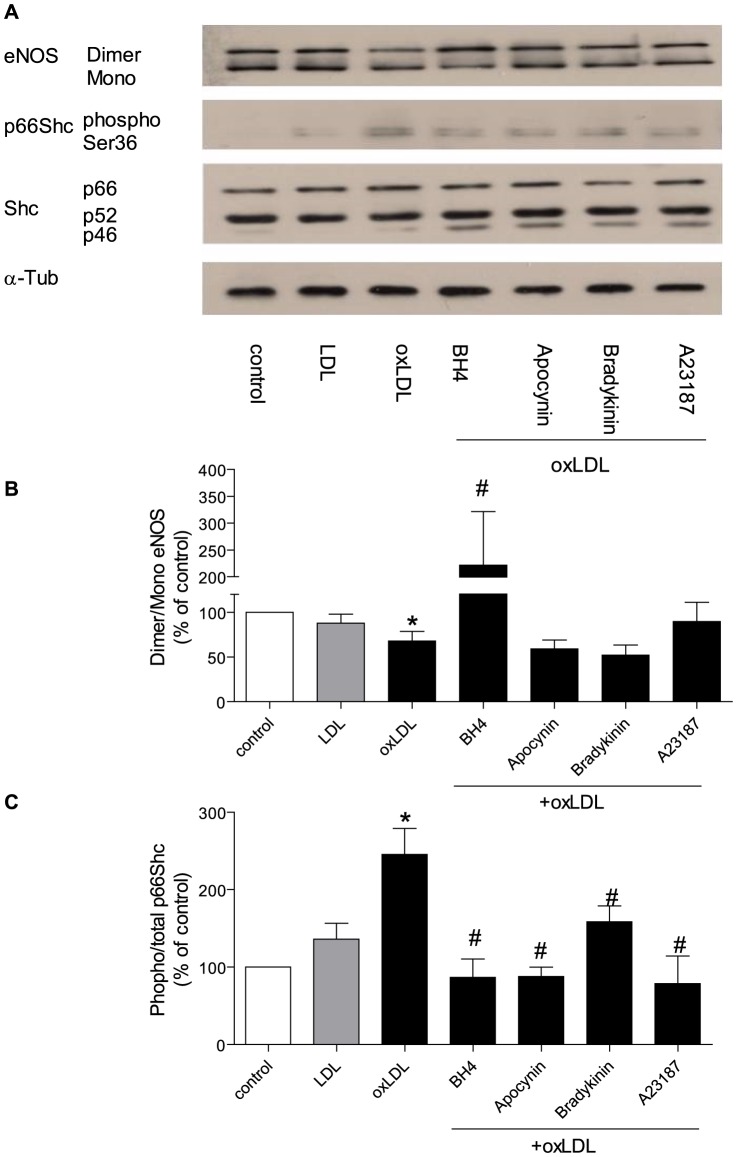

After 24 hours, DetaNO [23], a NO donor with a half life of up to 20 hours, at 1 mM, but not at 0.1 mM, significantly reduced oxLDL-induced p66Shc phosphorylation. DeaNO [24], another NO donor which has a half life of 2 minutes, either at 1 mM or 0.1 mM, did not significantly change the level of p66Shc phosphorylation ( Figure 3 ). After 24 hours, bradykinin (1 µM) [25] or calcium ionphore (1 µM) [26] significantly reduced oxLDL-induced p66Shc phosporylation ( Figure 4 ).

Figure 3. Representative Western blot (A) and densitometric quantification of phospho-p66Shc protein (B) expression in HAEC after twenty-four hours of incubation with oxLDL in the presence of nitric oxide donor (DetaNO 0.1-1 mM or DeaNO 0.1–1 mM).

The phosphorylation of p66Shc was normalized to total p66Shc protein and total p66Shc was normalized to α-tubulin. Results are presented as means±SEM; n = 5. * p<0.05 vs. cells under control conditions. # p<0.05 vs. oxLDL alone.

Figure 4. Representive Western blot (A) and densitometric quantification of eNOS uncoupling (B) and phospho-p66Shc protein (C) expression in HAEC after twenty-four hours incubation with oxLDL in the presence of tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4 10 µM), apocynin (100 µM), bradykinin (1 µM) or calcium ionophore (A23187 1 µM).

eNOS uncoupling was presented as ratio of dimer/monomer form of eNOS. The phosphorylation of p66Shc was normalized to total p66Shc protein and total p66Shc was normalized to α-tubulin. Results are presented as means±SEM; n = 8. * p<0.05 vs. cells under control conditions. # p<0.05 vs. oxLDL alone.

8-Br-cGMP (1 mM) [27], an analogue of cyclic guanosine monophosphate, prevented the oxLDL-induced p66Shc phosphorylation after 24 hours stimulation of oxLDL (Figure S2).

2.3 Inhibition of protein kinase G pathway does not change p66Shc phosphorylation

ODQ (10 µM) [28], an inhibitor of soluble guanylyl cyclase, did not significantly change the phosphorylation level of p66Shc protein, either in the presence or absence of oxLDL. Likewise, KT5823 (1 µM) [29], an inhibitor of protein kinase G, did not significantly alter the phosphorylation level of the p66Shc protein, either in the presence or absence of oxLDL (Figure S3).

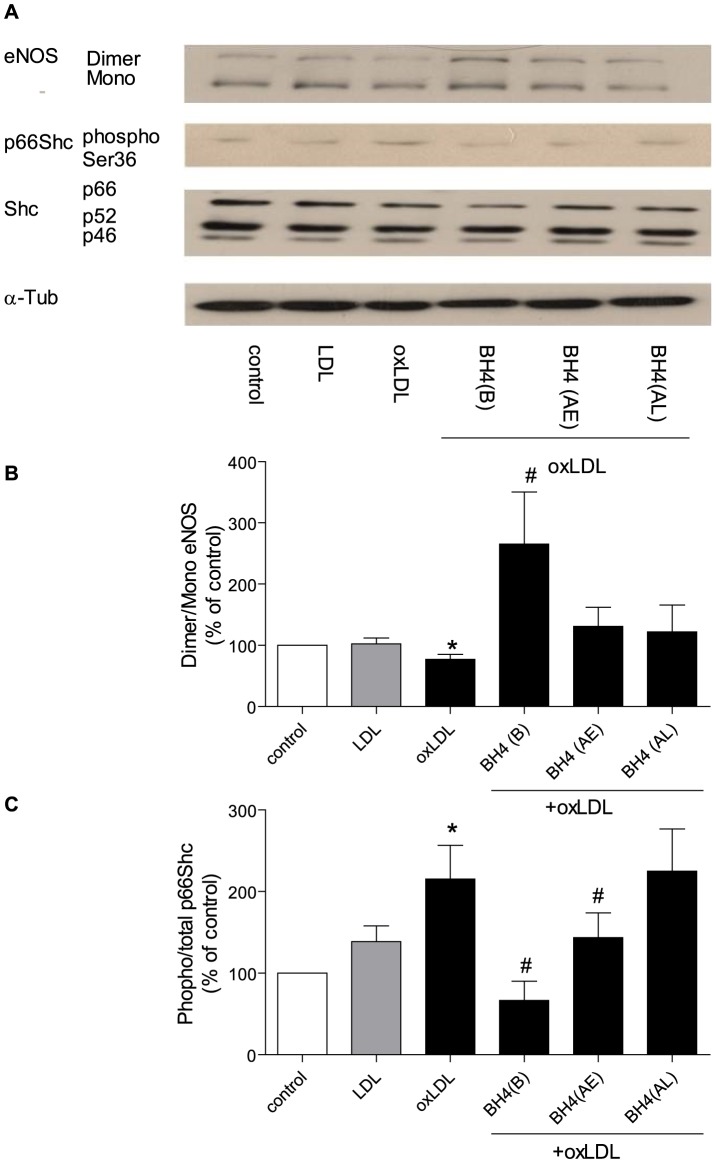

3. Tetrahydrobiopterin prevents p66Shc phosphorylation and restores eNOS uncoupling

After 24 h of exposure to oxLDL, tetrahydrobiopterin (10 µM) [30], a cofactor of eNOS, increased the dimer/monomor ratio of eNOS and prevented p66Shc phosphorylation. Furthermore, apocynin, an antioxidant, significantly reduced the phosphorylation level of p66Shc, but did not change the dimer/monomor ratio of eNOS ( Figure 4 )

Under the same experimental conditions, administration of tetrahydrobiopterin (45 minutes after oxLDL), reduced p66Shc phosphorylation, but did not change the eNOS dimer/monomor ratio. Administration of tetradydrobiopterin (16 hours after oxLDL), did not change the eNOS dimer/monomor ratio nor oxLDL-induced p66Shc phosphorylation ( Figure 5 ).

Figure 5. Representive Western blot (A) and densitometric quantification of eNOS uncoupling (B) and phospho-p66Shc protein (C) in HAEC after twenty-four hours incubation with oxLDL in the presence of tetrahydrobiopterin [BH4 10 µM; before (B), forty five minutes after (After Early, AE), or sixteen hours after (After Later, AL) oxLDL treatment].

eNOS uncoupling was presented as ratio of dimer/monomer form of eNOS. The phosphorylation of p66Shc was normalized to total p66Shc protein and total p66Shc was normalized to α-tubulin. Results are presented as means±SEM; n = 8. * p<0.05 vs. cells treated with oxLDL alone.

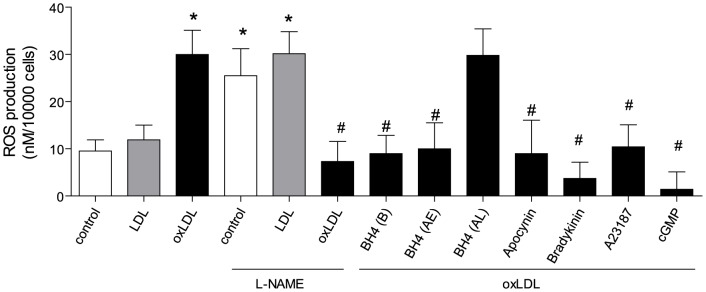

4. oxLDL induces reactive oxygen species

The production of reactive oxygen species was measured in HAEC 24 hours after exposure to oxLDL. In the presence of oxLDL, but not native LDL, endothelial cells exhibited an increased production of O2-. This enhanced production of O2- was inhibited by apocynin (100 µM) [18]. In the absence of oxLDL, L-NAME alone induced a high level of O2- in endothelial cells, whereas in the presence of oxLDL, L-NAME significantly reduced the production of O2 - ( Figure 6 ).

Figure 6. O2- production after twenty-four hours of incubation with oxLDL in the presence or absence of tetrahydrobiopterin [BH4 10 µM, before (B), forty five minutes after (AE), and sixteen hours after (AL) oxLDL treatment], apocynin (100 µM), bradykinin (1 µM), calcium ionophore (1 µM), L-NAME (0.3 mM) and cGMP (1 mM).

Results are presented as means±SEM; n = 8. * p<0.05 vs. cells under control conditions. # p<0.05 vs. oxLDL alone.

Bradykinin or calcium ionophore significantly reduced oxLDL-induced O2 - production. 8-Br-cGMP reduced the level of oxLDL-induced O2 - ( Figure 6 ).

Tetrahydrobiopterin, administrated either 60 minutes before (B) or 45 minutes after oxLDL stimulation (AE), significantly reduced oxLDL-induced O2 - production. However the late administration (AL) failed to decrease O2 - production in endothelial cell ( Figure 6 ).

oxLDL did not change levels of protein peroxynitrition in endothelial cells (Figure S4).

Discussion

This study analyzed the molecular mechanisms underlying the dual role of eNOS and its product NO in controlling the activation of p66Shc adaptor protein – an important mediator of ROS-dependent cardiovascular disease. In primary HAECs, inhibition of eNOS induced p66Shc activation and ROS production, suggesting that under basal condition eNOS provides an inhibitory signal preventing p66Shc activation and p66Shc-dependent ROS production. In contrast, in primary HAECs stimulated by oxLDL, eNOS uncoupled and acted as the primary source of p66Shc-mediated ROS. Accordingly, under these conditions tetrahydrobiopterin restored eNOS coupling and function, prevented p66Shc activation, and reduced superoxide generation.

p66Shc adaptor protein is importantly involved in various forms of cardiovascular disease by providing reactive oxygen species. Of note, genetic deletion of p66Shc protein preserves endothelial function in aging mice and extends life span of these animals. Furthermore, p66Shc deletion preserves endothelial function and reduces plaque formation in ApoE−/− mice by virtue of a reduced production of reactive oxygen species [16], [17]. Similar effects occur in diabetic endothelial dysfunction and in experimental stroke [11], [31].

p66Shc phosphorylation, at serine 36 amino acid residue, mediates ROS production in different settings [16], [18], [32] via activation of NADPH oxidase [18], [20] and/or release of ROS from mitochondria via opening of PTC pores [33].

Interestingly, in unstimulated HAECs, inhibition of eNOS by the pharmacological inhibitor LNAME or by using siRNA preventing translation of the protein, both induced p66Shc phosphorylation and increased generation of O2-, suggesting that under these conditions, basal release of NO inhibits the activation of the adaptor protein and the formation of ROS, thereby playing a so far unrecognized antioxidant role. Importantly, neither cyclic GMP nor protein kinase G is involved in this process since this effect was not observed after treatment with ODQ or KT5823, suggesting a direct interaction between O2 - and NO in the present set up [2].

oxLDL, a key mediator of atherosclerosis, induced p66Shc phosphorylation and in turn stimulated O2 - production in endothelial cells, confirming that the adaptor protein p66Shc is activated by the modified lipoprotein and a crucial regulator of intracellular ROS generation [16], [18]. In the presence of oxLDL, the NO donor (DetaNO) as well as receptor-operated activators of eNOS such as bradykinin or receptor-independent activators such as calcium ionophore, reduced p66Shc activation and decreased O2 - production. These results suggest that NO also provides a protective effect against reactive oxygen species under stimulated condition. Treatment with cyclic GMP prevented p66Shc phosphorylation and superoxide generation after 24 hours, indicating that the protective role of basal NO is mediated through the NO-cGMP pathway [1], [34].

Of note, oxLDL transiently induced eNOS uncoupling and p66Shc phosphorylation within 15 minutes of incubation. After 24 h of stimulation with oxLDL, inhibition of eNOS reduced p66Shc phosphorylation and decreased the O2 - production suggesting that under stimulated conditions eNOS becomes a source of reactive oxygen species [5], [35]. Apocynin reduced oxLDL-induced p66Shc phosphorylation and superoxide production, but did not restore eNOS uncoupling, indicating that eNOS uncoupling is upstream of p66Shc activation. In line with that, tetrahydrobiopterin, a cofactor of eNOS, restored oxLDL-induced eNOS uncoupling and p66Shc-dependent superoxide generation, once again suggesting that eNOS uncoupling is the primary source of oxLDL-induced, p66Shc-mediated reactive oxygen species.

Uncoupling of eNOS is an important mechanism of endothelial dysfunction in atherosclerosis [36], diabetes [37], and hypertension [5]. The underlying mechanisms of eNOS uncoupling include tetrahydrobiopterin deficiency [38], decreased levels of L-arginine [39], enhanced levels of asymmetric dimethylarginine [40] or S-glutathionylation of eNOS [41]. Deficiency of tetrahydrobiopterin seems to be the primary cause for eNOS uncoupling under pathophysiological conditions [42]. Tetrahydrobiopterin facilitates electron transfer from the eNOS reductase domain and maintains the heme prosthetic group in its redox active forms. Further tetrahydrobiopterin promotes and stabilizes eNOS protein monomers into the active homodimeric form of the enzyme [38], [43]. Increased levels of tetrahydrobiopterin enhance eNOS activity in cultured cells [44], [45] and promote vasodilatation in isolated mouse pial arterioles [46]. In animal experiments, tetrahydrobiopterin treatment reduces oxidative stress and preserves endothelial function in streptozotocin-induced type I diabetes [47], insulin-resistant type II diabetes [48], DOCA-salt induced hypertension [49] and ischemia/reperfusion induced injury [50]. However, results in human studies are controversial; it has been reported that tetrahydrobiopterin improves endothelial dysfunction in postmenopausal women [51], subjects with hypercholesterolemia [52], patients with chronic coronary disease [53], smokers [54] and type II diabetic patients [55]. Additionally, it was reported that oral tetrahydrobiopterin does not alter vascular redox state or endothelial function owing to systemic and vascular oxidation of tetrahydrobiopterin [56]. In the present study, tetrahydrobiopterin treatment, prior to oxLDL stimulation, prevented p66Shc-mediated oxidative stress, confirming that tetrahydrobiopterin confers a protective effect on eNOS coupling. Interestingly, this effect was also observed with tetrahydrobiopterin treatment early after oxLDL stimulation, but not in the late treatment, implying that other sources of oxidative stress participate in ROS generation at late stage, which cannot be inhibited by a late tetrahydrobiopterin treatment. p66Shc adaptor protein is reported to translates oxidative damage into cell death by acting as mediator of reactive oxygen species within mitochondria [33]. We reported previously that upon oxLDL stimulation in human aortic endothelial cells, p66Shc protein is activated leading to increased p47phox protein expression and superoxide anion production; this effect is mediated via lectin-like oxLDL receptor-1, activation of protein kinase C beta-2 and c-Jun N-terminal kinase, respectively [18]. Interestingly,, this effect could not be prevented by p66Shc silencing. [18]. Thus the results in the present study provide a possible molecular explanation for those antioxidant treatments in large, long-term clinic trials, which have failed to improve cardiovascular outcome [57], [58], [59].

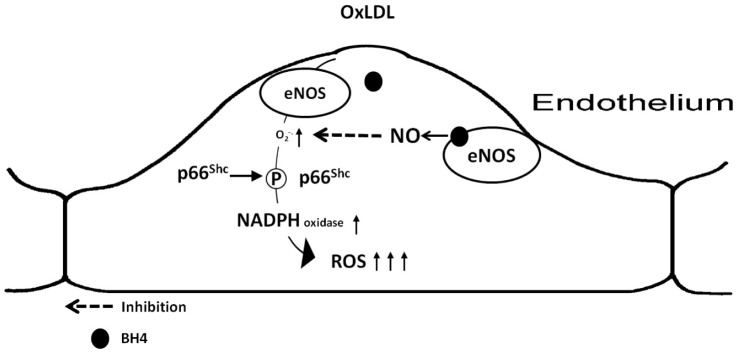

The present experiments performed in cultured human primary endothelial cells describe a dual role of eNOS for p66Shc protein activation and reactive oxygen species generation. It appears that eNOS uncoupling is a crucial player in oxLDL-induced and p66Shc-mediated intracellular reactive oxygen species generation ( Figure 7 ). These findings provide important mechanistic information about endothelial dysfunction, thus eNOS uncoupling represents a potential therapeutic target for early intervention of atherosclerosis.

Figure 7. Putative role of eNOS in oxLDL-induced, p66Shc- mediated oxidative stress in HAEC.

eNOS uncoupling is the primary source of oxLDL-induced oxidative stress in endothelial cells, leading to the p66Shc activation and later surge of ROS production. Supply with nitric oxide or reversal eNOS uncoupling reduces p66Shc activation and ROS production.

Supporting Information

Representative Western blot of eNOS, total Shc protein (p66, p52, and p46), and α-tubulin expression in HAEC treated with small interfering RNA against eNOS. (SiGAPDH: small interfering RNA against GAPDH; NFS: nanoparticle formation solution).

(EPS)

Representative Western blot (A) and densitometric quantification of phospho-p66Shc protein expression (B) in HAEC after twenty-four hours of incubation with oxLDL in the presence of cGMP (1 mM) (A). The phosphorylation of p66Shc was normalized to total p66Shc protein and total p66Shc was normalized to α-tubulin. Results are presented as means±SEM; n = 5. * p<0.05 vs. cells under control conditions. # p<0.05 vs. oxLDL alone.

(EPS)

Densitometric quantification of phospho-p66Shc protein expression in HAEC after twenty-four hours of incubation with oxLDL in the presence or absence of KT 5832 (1 µM). The phosphorylation of p66Shc was normalized to total p66Shc protein and total p66Shc was normalized to α-tubulin. Results are presented as means±SEM; n = 5. * p<0.05 vs. cells under control conditions.

(EPS)

Densitometric quantification of protein peroxynitrition in HAEC after twenty-four hours of incubation with oxLDL. The level of protein peroxynitrition was normalized to α-tubulin. Results are presented as means±SEM; n = 5.

(EPS)

Data Availability

The authors confirm that all data underlying the findings are fully available without restriction. All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The present study was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation grant number 310030_147017 to GGC, the Olga Mayenfish and the Hartmann Müller foundations. This work was also partly supported by grant from the National Nature Science Foundation of China 81373412 to YS. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Furchgott RF, Zawadzki JV (1980) The obligatory role of endothelial cells in the relaxation of arterial smooth muscle by acetylcholine. Nature 288: 373–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rubanyi GM, Vanhoutte PM (1986) Superoxide anions and hyperoxia inactivate endothelium-derived relaxing factor. Am J Physiol 250: H822–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bath PM (1993) The effect of nitric oxide-donating vasodilators on monocyte chemotaxis and intracellular cGMP concentrations in vitro. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 45: 53–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moncada S, Palmer RM, Higgs EA (1991) Nitric oxide: physiology, pathophysiology, and pharmacology. Pharmacol Rev 43: 109–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Landmesser U, Dikalov S, Price SR, McCann L, Fukai T, et al. (2003) Oxidation of tetrahydrobiopterin leads to uncoupling of endothelial cell nitric oxide synthase in hypertension. J Clin Invest 111: 1201–1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zou MH, Shi C, Cohen RA (2002) Oxidation of the zinc-thiolate complex and uncoupling of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by peroxynitrite. J Clin Invest 109: 817–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cosentino F, Lüscher TF (1999) Tetrahydrobiopterin and endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity. Cardiovasc Res 43: 274–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Alp NJ, McAteer MA, Khoo J, Choudhury RP, Channon KM (2004) Increased endothelial tetrahydrobiopterin synthesis by targeted transgenic GTP-cyclohydrolase I overexpression reduces endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis in ApoE-knockout mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 24: 445–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fleming I, Mohamed A, Galle J, Turchanowa L, Brandes RP, et al. (2005) Oxidized low-density lipoprotein increases superoxide production by endothelial nitric oxide synthase by inhibiting PKCalpha. Cardiovasc Res 65: 897–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Franzeck FC, Hof D, Spescha RD, Hasun M, Akhmedov A, et al. Expression of the aging gene p66Shc is increased in peripheral blood monocytes of patients with acute coronary syndrome but not with stable coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis 220: 282–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Spescha RD, Shi Y, Wegener S, Keller S, Weber B, et al. Deletion of the ageing gene p66(Shc) reduces early stroke size following ischaemia/reperfusion brain injury. Eur Heart J 34: 96–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Camici GG, Cosentino F, Tanner FC, Lüscher TF (2008) The role of p66Shc deletion in age-associated arterial dysfunction and disease states. J Appl Physiol 105: 1628–1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bonfini L, Migliaccio E, Pelicci G, Lanfrancone L, Pelicci PG (1996) Not all Shc's roads lead to Ras. Trends Biochem Sci 21: 257–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shi Y, Camici GG, Luscher TF (2010) Cardiovascular determinants of life span. Pflugers Arch 459: 315–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Camici GG, Shi Y, Cosentino F, Francia P, Luscher TF (2010) Anti-Aging Medicine: Molecular Basis for Endothelial Cell-Targeted Strategies - A Mini-Review. Gerontology. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16. Migliaccio E, Giorgio M, Mele S, Pelicci G, Reboldi P, et al. (1999) The p66shc adaptor protein controls oxidative stress response and life span in mammals. Nature 402: 309–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Napoli C, Martin-Padura I, de Nigris F, Giorgio M, Mansueto G, et al. (2003) Deletion of the p66Shc longevity gene reduces systemic and tissue oxidative stress, vascular cell apoptosis, and early atherogenesis in mice fed a high-fat diet. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100: 2112–2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shi Y, Cosentino F, Camici GG, Akhmedov A, Vanhoutte PM, et al. (2011) Oxidized Low-Density Lipoprotein Activates p66Shc via Lectin-Like Oxidized Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor-1, Protein Kinase C-{beta}, and c-Jun N-Terminal Kinase Kinase in Human Endothelial Cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 31: 2090–2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Giorgio M, Migliaccio E, Orsini F, Paolucci D, Moroni M, et al. (2005) Electron transfer between cytochrome c and p66Shc generates reactive oxygen species that trigger mitochondrial apoptosis. Cell 122: 221–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tomilov AA, Bicocca V, Schoenfeld RA, Giorgio M, Migliaccio E, et al. Decreased superoxide production in macrophages of long-lived p66Shc knock-out mice. J Biol Chem 285: 1153–1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kim CS, Jung SB, Naqvi A, Hoffman TA, DeRicco J, et al. (2008) p53 impairs endothelium-dependent vasomotor function through transcriptional upregulation of p66shc. Circ Res 103: 1441–1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yamamori T, White AR, Mattagajasingh I, Khanday FA, Haile A, et al. (2005) P66shc regulates endothelial NO production and endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation: implications for age-associated vascular dysfunction. J Mol Cell Cardiol 39: 992–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mooradian DL, Hutsell TC, Keefer LK (1995) Nitric oxide (NO) donor molecules: effect of NO release rate on vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation in vitro. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 25: 674–678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Morley D, Maragos CM, Zhang XY, Boignon M, Wink DA, et al. (1993) Mechanism of vascular relaxation induced by the nitric oxide (NO)/nucleophile complexes, a new class of NO-based vasodilators. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 21: 670–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mullane KM, Moncada S, Vane JR (1980) Prostacyclin release induced by bradykinin may contribute to the antihypertensive action of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. Adv Prostaglandin Thromboxane Res 7: 1159–1161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vanhoutte PM, Collis MG, Janssens WJ, Verbeuren TJ (1981) Calcium dependence of prejunctional inhibitory effects of adenosine and acetylcholine on adrenergic neurotransmission in canine saphenous veins. Eur J Pharmacol 72: 189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Southgate K, Newby AC (1990) Serum-induced proliferation of rabbit aortic smooth muscle cells from the contractile state is inhibited by 8-Br-cAMP but not 8-Br-cGMP. Atherosclerosis 82: 113–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Garthwaite J, Southam E, Boulton CL, Nielsen EB, Schmidt K, et al. (1995) Potent and selective inhibition of nitric oxide-sensitive guanylyl cyclase by 1H-[1,2,4]oxadiazolo[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one. Mol Pharmacol 48: 184–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wyatt TA, Pryzwansky KB, Lincoln TM (1991) KT5823 activates human neutrophils and fails to inhibit cGMP-dependent protein kinase phosphorylation of vimentin. Res Commun Chem Pathol Pharmacol 74: 3–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tayeh MA, Marletta MA (1989) Macrophage oxidation of L-arginine to nitric oxide, nitrite, and nitrate. Tetrahydrobiopterin is required as a cofactor. J Biol Chem 264: 19654–19658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Camici GG, Schiavoni M, Francia P, Bachschmid M, Martin-Padura I, et al. (2007) Genetic deletion of p66(Shc) adaptor protein prevents hyperglycemia-induced endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104: 5217–5222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Le S, Connors TJ, Maroney AC (2001) c-Jun N-terminal kinase specifically phosphorylates p66ShcA at serine 36 in response to ultraviolet irradiation. J Biol Chem 276: 48332–48336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pinton P, Rimessi A, Marchi S, Orsini F, Migliaccio E, et al. (2007) Protein kinase C beta and prolyl isomerase 1 regulate mitochondrial effects of the life-span determinant p66Shc. Science 315: 659–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Feletou M, Tang EH, Vanhoutte PM (2008) Nitric oxide the gatekeeper of endothelial vasomotor control. Front Biosci 13: 4198–4217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cosentino F, Patton S, d'Uscio LV, Werner ER, Werner-Felmayer G, et al. (1998) Tetrahydrobiopterin alters superoxide and nitric oxide release in prehypertensive rats. J Clin Invest 101: 1530–1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Li H, Forstermann U (2009) Prevention of atherosclerosis by interference with the vascular nitric oxide system. Curr Pharm Des 15: 3133–3145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hink U, Li H, Mollnau H, Oelze M, Matheis E, et al. (2001) Mechanisms underlying endothelial dysfunction in diabetes mellitus. Circ Res 88: E14–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Channon KM (2004) Tetrahydrobiopterin: regulator of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in vascular disease. Trends Cardiovasc Med 14: 323–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pritchard KA Jr, Ackerman AW, Gross ER, Stepp DW, Shi Y, et al. (2001) Heat shock protein 90 mediates the balance of nitric oxide and superoxide anion from endothelial nitric-oxide synthase. J Biol Chem 276: 17621–17624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sud N, Wells SM, Sharma S, Wiseman DA, Wilham J, et al. (2008) Asymmetric dimethylarginine inhibits HSP90 activity in pulmonary arterial endothelial cells: role of mitochondrial dysfunction. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 294: C1407–1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chen CA, Wang TY, Varadharaj S, Reyes LA, Hemann C, et al. (2010) S-glutathionylation uncouples eNOS and regulates its cellular and vascular function. Nature 468: 1115–1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gao YT, Roman LJ, Martasek P, Panda SP, Ishimura Y, et al. (2007) Oxygen metabolism by endothelial nitric-oxide synthase. J Biol Chem 282: 28557–28565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fukai T (2007) Endothelial GTPCH in eNOS uncoupling and atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 27: 1493–1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rosenkranz-Weiss P, Sessa WC, Milstien S, Kaufman S, Watson CA, et al. (1994) Regulation of nitric oxide synthesis by proinflammatory cytokines in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Elevations in tetrahydrobiopterin levels enhance endothelial nitric oxide synthase specific activity. J Clin Invest 93: 2236–2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Huang A, Vita JA, Venema RC, Keaney JF Jr (2000) Ascorbic acid enhances endothelial nitric-oxide synthase activity by increasing intracellular tetrahydrobiopterin. J Biol Chem 275: 17399–17406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rosenblum WI (1997) Tetrahydrobiopterin, a cofactor for nitric oxide synthase, produces endothelium-dependent dilation of mouse pial arterioles. Stroke 28: 186–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Faria AM, Papadimitriou A, Silva KC, Lopes de Faria JM, Lopes de Faria JB (2012) Uncoupling endothelial nitric oxide synthase is ameliorated by green tea in experimental diabetes by re-establishing tetrahydrobiopterin levels. Diabetes 61: 1838–1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Shinozaki K, Nishio Y, Okamura T, Yoshida Y, Maegawa H, et al. (2000) Oral administration of tetrahydrobiopterin prevents endothelial dysfunction and vascular oxidative stress in the aortas of insulin-resistant rats. Circ Res 87: 566–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Youn JY, Wang T, Blair J, Laude KM, Oak JH, et al. (2012) Endothelium-specific sepiapterin reductase deficiency in DOCA-salt hypertension. Am JPhysiol Heart Circ Physiol 302: H2243–2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Perkins KA, Pershad S, Chen Q, McGraw S, Adams JS, et al. (2012) The effects of modulating eNOS activity and coupling in ischemia/reperfusion (I/R). Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 385: 27–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Moreau KL, Meditz A, Deane KD, Kohrt WM (2012) Tetrahydrobiopterin improves endothelial function and decreases arterial stiffness in estrogen-deficient postmenopausal women. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 302: H1211–1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Holowatz LA, Kenney WL (2011) Acute localized administration of tetrahydrobiopterin and chronic systemic atorvastatin treatment restore cutaneous microvascular function in hypercholesterolaemic humans. J Physiol 589: 4787–4797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Maier W, Cosentino F, Lutolf RB, Fleisch M, Seiler C, et al. (2000) Tetrahydrobiopterin improves endothelial function in patients with coronary artery disease. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 35: 173–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ueda S, Matsuoka H, Miyazaki H, Usui M, Okuda S, et al. (2000) Tetrahydrobiopterin restores endothelial function in long-term smokers. J Am Coll Cardiol 35: 71–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Heitzer T, Krohn K, Albers S, Meinertz T (2000) Tetrahydrobiopterin improves endothelium-dependent vasodilation by increasing nitric oxide activity in patients with Type II diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 43: 1435–1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Cunnington C, Van Assche T, Shirodaria C, Kylintireas I, Lindsay AC, et al. (2012) Systemic and vascular oxidation limits the efficacy of oral tetrahydrobiopterin treatment in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation 125: 1356–1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Liu S, Lee IM, Song Y, Van Denburgh M, Cook NR, et al. (2006) Vitamin E and risk of type 2 diabetes in the women's health study randomized controlled trial. Diabetes 55: 2856–2862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ward NC, Wu JH, Clarke MW, Puddey IB, Burke V, et al. (2007) The effect of vitamin E on blood pressure in individuals with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Hypertens 25: 227–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sesso HD, Buring JE, Christen WG, Kurth T, Belanger C, et al. (2008) Vitamins E and C in the prevention of cardiovascular disease in men: the Physicians' Health Study II randomized controlled trial. JAMA 300: 2123–2133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Representative Western blot of eNOS, total Shc protein (p66, p52, and p46), and α-tubulin expression in HAEC treated with small interfering RNA against eNOS. (SiGAPDH: small interfering RNA against GAPDH; NFS: nanoparticle formation solution).

(EPS)

Representative Western blot (A) and densitometric quantification of phospho-p66Shc protein expression (B) in HAEC after twenty-four hours of incubation with oxLDL in the presence of cGMP (1 mM) (A). The phosphorylation of p66Shc was normalized to total p66Shc protein and total p66Shc was normalized to α-tubulin. Results are presented as means±SEM; n = 5. * p<0.05 vs. cells under control conditions. # p<0.05 vs. oxLDL alone.

(EPS)

Densitometric quantification of phospho-p66Shc protein expression in HAEC after twenty-four hours of incubation with oxLDL in the presence or absence of KT 5832 (1 µM). The phosphorylation of p66Shc was normalized to total p66Shc protein and total p66Shc was normalized to α-tubulin. Results are presented as means±SEM; n = 5. * p<0.05 vs. cells under control conditions.

(EPS)

Densitometric quantification of protein peroxynitrition in HAEC after twenty-four hours of incubation with oxLDL. The level of protein peroxynitrition was normalized to α-tubulin. Results are presented as means±SEM; n = 5.

(EPS)

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that all data underlying the findings are fully available without restriction. All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.