Abstract

BLM and WRN are members of the RecQ family of DNA helicases that act to suppress genome instability and cancer predisposition. In addition to a RecQ helicase domain, each of these proteins contains an N-terminal domain of approximately 500 amino acids (aa) that is incompletely characterized. Previously, we showed that the N-terminus of Sgs1, the yeast ortholog of BLM, contains a physiologically important 200 aa domain (Sgs1103–322) that displays single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) binding, strand annealing (SA), and apparent strand-exchange (SE) activities in vitro. Here we used a genetic assay to search for heterologous proteins that could functionally replace this domain of Sgs1 in vivo. In contrast to Rad59, the oligomeric Rad52 protein provided in vivo complementation, suggesting that multimerization is functionally important. An N-terminal domain of WRN was also identified that could replace Sgs1103–322 in yeast. This domain, WRN235–526, contains a known coiled coil and displays the same SA and SE activities as Sgs1103–322. The coiled coil domain of WRN235–526 was found to be required for both its in vivo activity and its in vitro SE activity. Based on this result, a potential coiled coil was identified within Sgs1103–322. This 25 amino acid region was similarly essential for wt Sgs1 activity in vivo and was replaceable by a heterologous coiled coil. Taken together, the results indicate that a coiled coil and a closely-linked apparent SE activity are conserved features of the BLM and WRN DNA helicases.

Keywords: DNA helicase, DNA recombination, Genomic instability, DNA strand exchange, Protein nucleic acid interaction, Yeast genetics

1. Introduction

Genome integrity relies on the cell’s ability to correct a wide variety of DNA lesions. Among the most serious of these lesions are DNA double strand breaks (DSBs) that occur during DNA replication. At a minimum, the faithful repair of such DSBs requires homologous recombination (HR) and the RecQ family of DNA helicases [1]. In humans, the RecQ helicase family consists of RecQ1 and RecQ5, in addition to the proteins responsible for Werner’s syndrome (WS; WRN), Bloom’s syndrome (BS; BLM) and Rothmund-Thomson syndrome (RTS; RECQ4). All RecQ helicases share a core helicase sequence motif homologous to the RecQ DNA helicase of E. coli, and all display 3’–5’ DNA helicase activity in vitro. However, WRN, BLM and RECQ4 are further related by the presence of N-terminal domains of approximately 500 amino acids (aa). These N-terminal domains are not fully characterized. Presumably they provide functions that are unique to each protein. However, they may also possess catalytic functions that are conserved within this group of RecQ helicases. The identification of activities associated with the N-terminal domains of these proteins remains an important step in understanding the molecular causes of their respective diseases.

WS is a late-onset progeroid disease in which patients display premature signs of aging, an elevated risk of cancer and cells marked by genomic instability [2–5]. The WRN protein is unique among the RecQ family members in that it contains a 3’–5’ exonuclease domain in its N-terminus [6–10] and the N-terminus contains a coiled-coil domain that is important for proper multimerization in vivo [11] (Fig. 1A). BS is associated with low birthweight, immune deficiency and a predisposition to a diverse group of cancers [12, 13]. BS cells display an increased rate of sister chromatid exchange (SCE) and an overall increase in genomic instability [14, 15]. Thus, loss of these homologous DNA helicases results in some phenotypic similarities. An important difference between WRN and BLM is the role that BLM plays in the “BTR” complex which consists of BLM, Top3α, RMI1, and RMI2 [16–18]. BLM is conserved in most species including the yeast S. cerevisiae where it is known as Sgs1. Like human BLM, Sgs1 forms an “STR” complex with its cognate Top3 and Rmi1 subunits [19–26]. The physical interaction between BLM/Sgs1 and the Top3-Rmi1 complex requires a 100 aa domain (TR) at the extreme N-terminus of the helicases (Fig. 1A). BTR and STR act in HR repair pathways where they catalyze a variety of DNA transactions including 5’-end resection and double Holliday Junction dissolution [18, 27–33].

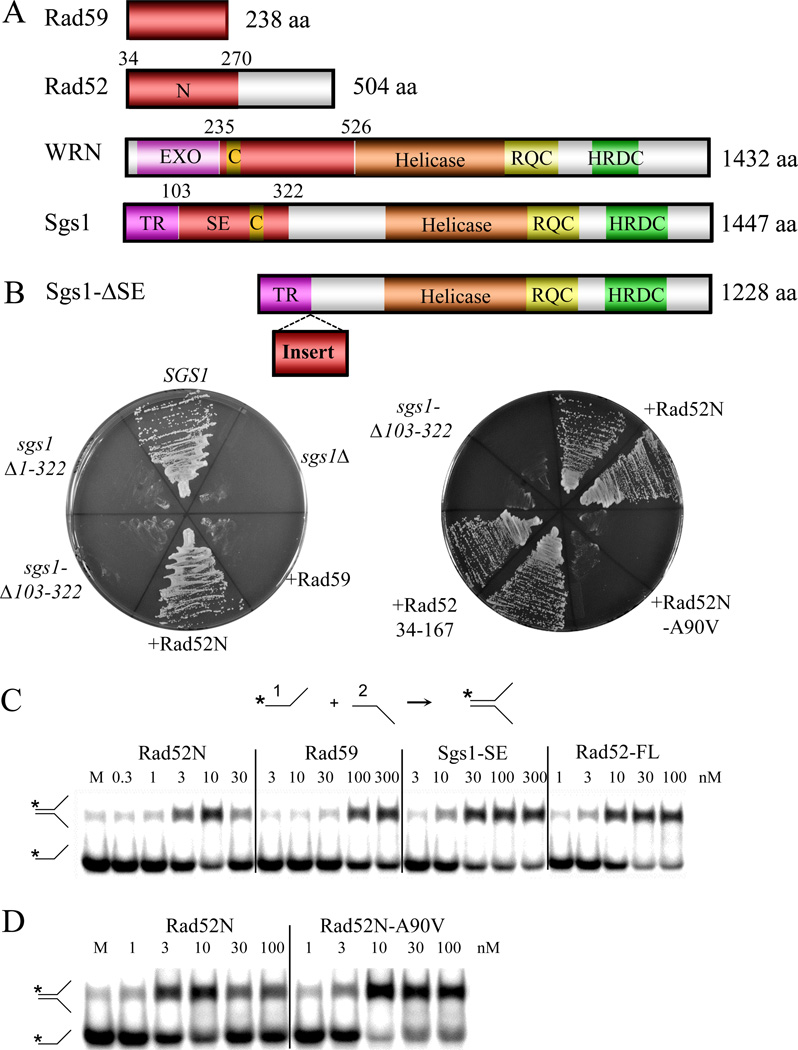

FIGURE 1.

Complementation of yeast sgs1Δ by chimeric Sgs1 fusion proteins. (A) Schematic representations of full-length yeast Rad59, Rad52, Sgs1, and human WRN proteins. Domains: N, N-terminal domain of Rad52; TR, Top3-Rmi1 binding; SE, strand exchange; EXO, 3’–5’ exonuclease domain; C, coiled coil. Note that yeast Rad52 begins at codon 34. (B) Top, The Sgs1-ΔSE protein (Sgs1Δ102–322) was modified by inserting the red domains from panel (A) at the indicated position to create Sgs1 fusion proteins. Bottom, yeast strain NJY2083 [sgs1Δ slx4Δ plus pJM500 (SGS1/URA3/ADE3/CEN)] was individually transformed with centromeric LEU2 plasmids containing the indicated SGS1 genes, or chimeric alleles expressing Sgs1 fused to the indicated foreign domains (+). To test for synthetic lethality, leucine prototrophs were streaked individually (left) or in duplicate (right) onto plates containing 5-FOA which selects against the balancer plasmid pJM500 [48]. (C) SA reactions contained the indicated concentrations of Rad52N (Rad5234–270), Rad59, Sgs1-SE (Sgs1102–322), or full-length Rad52 plus 1 nM each of a 32P-labeled 50 nt oligo (#1) and an unlabeled 50 nt oligo (#2) that share 25 nt of perfect complementarity. Following incubation at 37°C for 5 min, the reactions were stopped as described in the Experimental Procedures and the products were resolved by 10% PAGE and subjected to phosphorimager analysis. (D) SA assays were conducted as above using Rad52N and the A90V mutant protein. Asterisks represent positions of 32P-labelling. M, mock reaction without protein.

In addition to DNA helicase activity, all eukaryotic RecQ family members, regardless of the size of their N-terminal extension, display a ssDNA strand annealing (SA) activity that has not been observed in bacterial RecQ [34–38]. Where it has been mapped, this SA activity localizes to a region C-terminal of the core helicase domain near the less well-conserved RQC and HRDC domains (e.g., BLM residues 1290–1350) [36, 38]. This SA activity is inhibited by ATP and non-hydrolyzable nucleotide analogs [34–36, 38, 39] as well as by the ssDNA binding protein, Replication Protein A (RPA) [34, 36, 38, 40]. RPA is known to functionally interact with and stimulate the DNA helicase activity of BLM and WRN [40–43] where it binds through its 70 kDa subunit to the N-terminus of WRN and BLM [44].

Yeast Sgs1 has served as a useful model to study the structure and function of BLM [45–47]. Recently, a sub-domain of the N-terminus (Sgs1103–322) was identified that was required for many, but not all, functions of Sgs1 in vivo [48]. This 200 aa domain displayed ssDNA binding, ssDNA annealing, and apparent DNA strand exchange (SE) activity in vitro. The goal of the present study was to determine which of these biochemical activites are important for in vivo function. To do this, we replaced this domain of Sgs1 with heterologous proteins known to have such activities and tested these Sgs1-fusion proteins for in vivo complementation in yeast. Surprisingly, complementing proteins were found to both exhibit apparent SE activity in vitro and contain a multimerization domain. This led to the identification of a potential coiled-coil domain in the N-terminus of BLM/Sgs1. Both apparent SE and in vivo complementation are dependent on this multimerization domain. We also show for the first time that indistinguishable activities are associated with the N-terminus of WRN and its known coiled coil domain. The results indicate that SA, apparent SE and multimerization are conserved features of the N-termini of BLM and WRN.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protein Purification

All recombinant proteins were expressed in bacteria as C-terminal V5(His6)-tagged fusions and purified essentially as described [48]. E. coli BL21(DE3)-RIL cells were transformed with T7 expression plasmids and freshly-transformed colonies were pooled and grown in 1L LB media containing 0.1 mg/ml ampicillin at 37°C until OD 600 = 0.5. The recombinant protein was induced by the addition of 0.4 mM isopropyl-1-thio-D-galactopyranoside and the cells were grown at 30°C for 6 hours, except for full-length Rad52 which was induced for one hour. Induced cells were pelleted and resuspended in 40 ml Buffer N [25 mM Tris-HCl (pH7.5) 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.01% NP-40, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 10 % glycerol and 500M NaCl] containing 10 mM imidazole and the following protease inhibitors: pepstatin, 10 µg/ml; leupeptin, 5 µg/ml; benzamidine, 10 mM; and bacitracin, 100 µg/ml. The cells were sonicated for 2 min with a Branson sonifier 450 microtip at setting 2 and 25% duty cycle. The lysate was centrifuged at 13,500 rpm in an SS34 rotor at 4°C for 15 min and the supernatant was filtered before loading onto a 1 ml Ni Hi-Trap column (GE Healthcare). The column was washed with 10 CVs of Buffer N plus 10 mM imidazole and eluted with a 8 CV gradient from 10 to 500 mM imidazole in Buffer N. Peak fractions were pooled and dialyzed against buffer A [25 mM Tris-HCl (pH7.5), 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 0.01% NP-40, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 10 % glycerol and 1mM EDTA] containing 50 mM NaCl. The dialyzed pool was loaded onto a 1 ml MonoQ column, washed with Buffer A plus 50 mM NaCl and resolved into 0.5 ml fractions across a 8 CV gradient from 50 to 1000 mM NaCl. Peak fractions were stored at −80°C.

GST-RECQ4 sub-domain proteins were expressed as described above and purified by batch binding the extract from one liter of induced BL21(DE3) cells to 1 ml glutathione sepharose 4B resin for 2 hrs. The resin was poured into a column and washed with three column volumes of Buffer A plus 250 mM NaCl, then half column volume fractions were eluted at room temperature with Buffer A (pH 8.0) plus 150 mM NaCl and 10 mM glutathione. The peak fractions were determined by Bradford assay and SDS-PAGE, pooled and dialyzed to A buffer containing 100 mM NaCl. GST-fusion proteins were used directly in ssDNA binding assays.

Size-exclusion chromatography was performed on 24 ml Superose 6 and Superdex 75 columns at a flow rate of 0.3 ml/min in 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH7.5), 0.1 mM PMSF, 0.01% NP-40, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1mM EDTA and 300 mM NaCl. Superdex 75 samples contained the minimal C-terminal epitope tag LEHHHHHH, and Sgs1157–257ΔCC contained the sequence KLGS (encoded by linker DNA) in place of residues 225 – 250. Peak protein fractions were determined by absorbance at 280 nm or by SDS-PAGE and staining.

2..2 DNA Substrates

Oligodeoxynucleotides (oligos) were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA, USA. The sequences of the oligos used in this study are shown in Supplementary Table S1. The oligos were radiolabeled at their 5’-end with γ-32P-ATP by T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England BioLabs). To make double stranded DNA, 32P-labeled oligo #4 was annealed to a stoichiometric amount of oligo #5 by heating and slow cooling in 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 100 mM sodium chloride, 1 mM EDTA. Following electrophoresis in native 10% PAGE to separate labeled dsDNA from ssDNA, the band corresponding to dsDNA was excised and eluted by electrophoresis.

2.3. Complementation of sgs1Δ slx4Δ synthetic lethality

Complementation of synthetic lethality was performed essentially as described [48]. Yeast strain NJY2083 [sgs1-11::loxP slx4-11::loxP carrying pJM500 (SGS1/URA3/ADE3/CEN)] was transformed with the indicated SGS1 alleles cloned into the centromeric vector pRS415 [49] and selected on synthetic dextrose (SD) plates lacking leucine [50]. Transformants were then streaked onto SD plates containing 5-FOA and the plates were photographed following 2 days growth at 30°C.

2.4. EMSA, strand annealing and apparent DNA strand exchange assays

The EMSA, SA and apparent SE assays were performed as previously described [48] but with the following changes. SA and SE reactions contained the indicated concentrations of oligos in addition to 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM sodium chloride, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DDT and 10 µg/ml bovine serum albumin in a final volume of 20 µl. The reactions were assembled on ice and incubated at 37 °C for 5 min (SA assays) or 30 min (SE assays) unless otherwise indicated. Reactions were stopped by treating with a final concentration of 25 mM EDTA, 1% SDS and 1 mg/ml proteinase K at 37°C for 15 min. The STOP buffer for strand annealing reactions included the unlabeled version of the labeled oligo at a final concentration of 100 nM. After addition of loading dye, the samples were resolved by electrophoresis in 10% polyacrylamide (19:1 acrylamide:bis) gels at room temperature.

3. Results

3.1. Functional complementation of Sgs1-ΔSE with heterologous proteins

We previously used a yeast in vivo complementation assay to demonstrate that a domain of BLM can functionally replace Sgs1103–322 [48]. This assay is based on the fact that SGS1 is essential for viability in yeast cells lacking SLX4 [51] and that the sgs1-ΔSE allele (encoding Sgs1Δ103–322) is lethal in slx4Δ cells. Viability is restored by a chimeric SGS1-BLM95–300 allele in which Sgs1 residues 103–322 are replaced by BLM residues 95–300 [48]. Since both BLM95–300 and Sgs1103–322 displayed SA activity in vitro, we considered the possibility that heterologous SA proteins might function in place of Sgs1-SE.

The yeast Rad52 and Rad59 proteins are well-characterized SA proteins. Full-length Rad52 is a 471 aa oligomeric protein that anneals ssDNA and mediates the loading of Rad51 in the presence of RPA [52–54] (Fig. 1A). The N-terminal residues of Rad52 (34–270) are evolutionarily conserved and are sufficient for strand annealing and oligomerization [55]. The smaller Rad59 protein shares homology with the N-terminal DNA binding domain of Rad52 but lacks the C-terminal Rad51-interacting domain of Rad52 [56, 57]. As shown in Fig. 1B, a chimeric allele of Sgs1 containing Rad52N (Rad5234–270) fully complements the loss of Sgs1-SE in an slx4Δ strain, while Rad59 does not. The fusion of Sgs1 and Rad52 was important because overexpression of Rad52 on its own did not rescue viability (data not shown). Rad52 function was likely required in the chimeric protein since complementation was eliminated by the A90V mutation encoded by the original loss of function allele rad52–1 (Fig. 1B, right). Moreover, complementation was observed with a smaller domain (Rad5234–167) lacking the RPA-interacting region but retaining the DNA binding and Rad52 self-association domains [58, 59]. The ability of Rad52 to complement sgs1-ΔSE was not specific to this assay alone. The chimeric SGS1-RAD52N allele also conferred the prototypical slow-growth phenotype to sgs1Δ top3Δ cells [24] like wt SGS1 (Fig. S1).

The proteins identified above were tested for the ability to stimulate SA. In this assay two partially complementary oligos, one of which is radiolabled, are incubated together with protein and allowed to form a Y-shaped product upon annealing. Recombinant proteins, fused to C-terminal V5(His6) epitope tags, were expressed in E. coli and purified by Ni-affinity chromatography (Fig. S2A). Titrations of Rad52 and Rad59 led to the appearance of a retarded band that saturated at a concentration of 30–100 nM protein (Fig. 1C). This activity closely mimicked that of Sgs1-SE although Rad52N displayed optimal annealing at a lower concentration (10 nM) than the other proteins. Surprisingly, the mutant Rad52N-A90V protein retained SA activity (Fig. 1D). Taken together, the above results suggest that SA activity alone is insufficient to restore activity to Sgs1-ΔSE protein and that multimerization may be required.

3.2. Genetic and biochemical activities of WRN235–526

Having determined that proteins as divergent as BLM and Rad52 could genetically complement the loss of Sgs1-SE, we asked whether uncharacterized domains from more divergent RecQ proteins could similarly function in yeast. We therefore tested subdomains of the WRN DNA helicase for activity in the sgs1-ΔSE complementation assay by focusing on the region between its exonuclease and RecQ helicase domains (Fig. 1A). Most of this sequence (i.e., R235 - D526) is poorly conserved among WRN orthologs, however this region was recently shown to contain a conserved 53 aa heptad-repeat coiled-coil motif (L247-I299) that promotes WRN multimerization [11]. We therefore created chimeric Sgs1 proteins in which the Sgs1-SE domain was replaced by WRN235–526 or two N-terminal truncations of this domain, WRN255–526 and WRN301–526. As shown in Figure 2A, chimeric SGS1 alleles containing WRN235–526 or WRN255–526 conferred growth to slx4Δ sgs1Δ double mutants similar to that conferred by BLM95–300. However, WRN301–526 was unable to restore viability suggesting that the coiled coil is required for activity in this genetic assay. This analysis identified residue T255 as the N-terminal endpoint of the minimal functional domain. To identify the C-terminal endpoint, we tested another series of chimeric Sgs1-WRN proteins (Fig. 2A, right). In contrast to WRN255–526, fragments containing fewer C-terminal residues were able to provide viability but the cells were slow growing. The largest truncation removed part of the coiled coil and resulted in a fragment, WRN255–286, that was unable to confer viability. A quantitative spotting assay confirmed that residues C-terminal to the coiled coil were required for optimal growth (Fig. 2B). Thus, WRN255–366 defines the minimal essential domain based on viability alone, however larger domains such as WRN255–526 or WRN235–526 are required for optimal activity. Taken together, we conclude that while the coiled coil is necessary for in vivo complementation, it is not sufficient for wt activity.

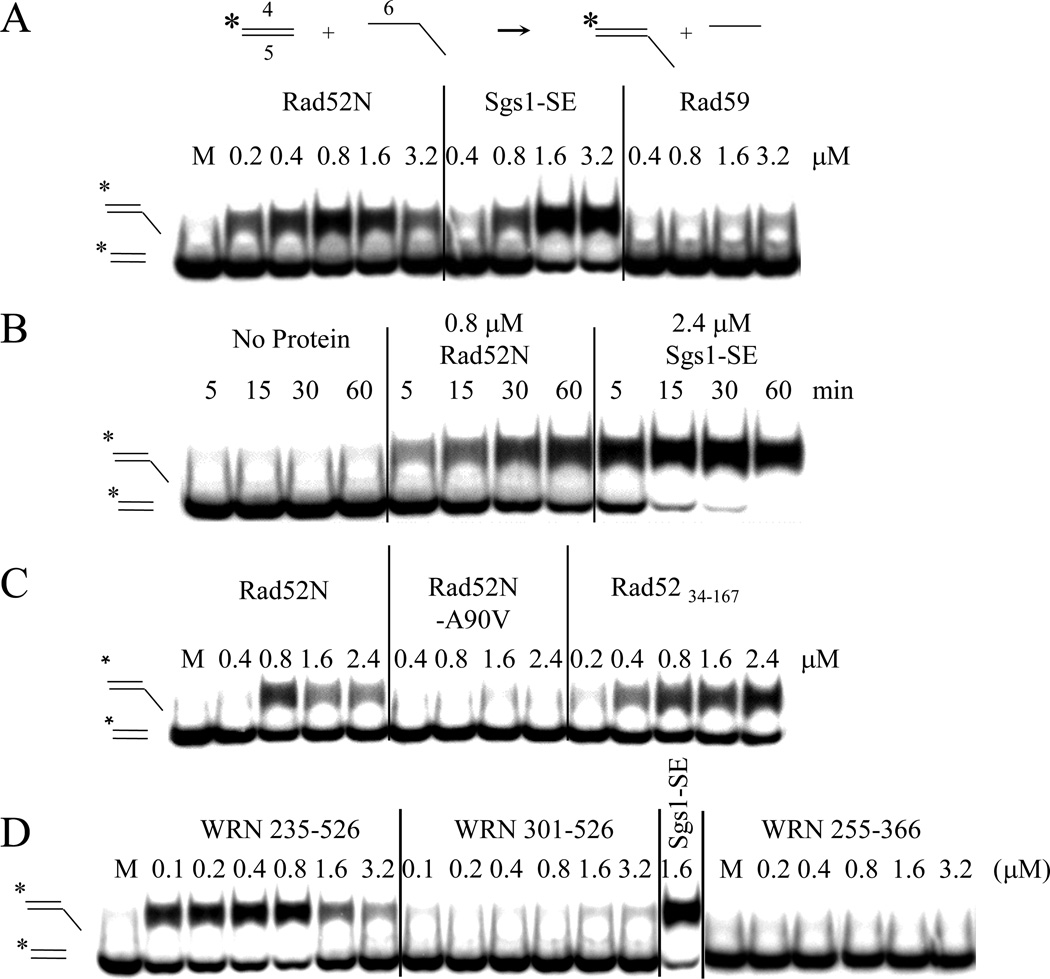

FIGURE 2.

Identification of a SA activity in WRN235–526. (A) Complementation of yeast sgs1Δ by chimeric Sgs1-WRN fusion proteins was performed as in Figure 1A. Structure-function analysis of the WRN235–526 fragment was carried out by truncating its N- (left) and C-termini (right). (B) To quantitatively assess growth rate cells transformed with C-terminal truncation plasmids were streak purified on media lacking leucine, resuspended at an OD600 =3 and subjected to 10-fold serial dilutions. Five µL of each dilution was spotted onto plates that either lack leucine or contain 5-FOA to assay synthetic lethality. Plates were photographed after 2 (-Leu) or 3 (5-FOA) days at 30°C. (C) SA assays were conducted as in Fig. 1C with the indicated concentrations of Sgs1103–322 and WRN235–526 . (D) SA assays were performed as above with Sgs1103–322 (50 nM) and WRN235–526 (50 nM) except that the reactions were stopped at the indicated times prior to analysis. (E) SA assays were conducted as above except that 2 nM each of radiolabled oligo #1 and unlabled oligo #3 were first pre-incubated 2 min at 30°C with the indicated concentrations of either E. coli SSB or human RPA before treatment with 100 nM WRN235–526. Following gel electrophoresis and phosphorimaging, the products were quantitated and the results presented as a function of the concentration of hRPA (closed bar) or SSB (open bar).

To search for biochemical activities associated with WRN235–526, we purified several recombinant proteins from E. coli (Fig. S2B) and subjected them to ssDNA binding and SA assays. As observed with the BLM and Sgs1-SE domains [48], WRN235–526 bound a radiolabled 174 nt poly(dT) oligo using an Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) and was less effective at binding short oligos (Fig. S2C). WRN235–526 catalyzed SA (Fig. 2C), and like Sgs1-SE, annealing by WRN235–526 was essentially complete in one minute (Fig. 2D). SA by WRN235–526 was tested for inhibition by ssDNA binding proteins. Annealing was strongly inhibited by pre-incubation with 10 nM E. coli SSB or 40 nM human RPA (Fig. 2E). Lastly, like Sgs1-SE and unlike the RecQ domain, strand annealing was not markedly affected by nucleotide cofactors or non-homologous competitor oligos (Fig. S3).

3.3. Apparent DNA strand-exchange (SE) activity correlates with in vivo activity

The above proteins were tested for the ability to transfer a radiolabeled strand from a blunt-ended 32 bp duplex onto a 57 nt recipient ssDNA containing a complementary 32 nt sequence. Rad52 and Sgs1-SE are known to display this ATP-independent activity on oligonucleotide substrates [48, 60] in a reaction that is referred to as apparent SE to distinguish it from reactions catalyzed by ATP-dependent recombinases. As shown in Figure 3A, both Rad52N and Sgs1-SE promoted the conversion of radioactive signal from the donor duplex into a slower-migrating form consistent with transfer of the labeled strand to the recipient oligo. This reaction is complete within 15–30 min (Fig. 3B). In contrast, neither Rad59 nor the mutant Rad52N–A90V displayed SE activity (Fig. 3C). This deficiency correlates with the inability of Rad59 and Rad52N–A90V to complement Sgs1-ΔSE function in vivo. In addition, a smaller subdomain (Rad5234–167) containing the DNA binding and self-association domains of Rad52 [52, 58] conferred growth in the Sgs1-ΔSE complementation assay and also displayed apparent SE activity (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

Characterization of apparent DNA strand exchange activity in SA proteins. (A) The reaction illustrated at the top of the panel was performed using a 32 bp radiolabeled dsDNA with flush ends as donor (oligos #4*/#5) and an unlabeled 57 nt oligo (#6) as recipient. Reactions containing 5 nM donor and 20 nM recipient were initiated by addition of the indicated concentrations of Rad52N, Sgs1103–322, or Rad59. Following incubation at 37°C for 30 min, the reactions were terminated and the products analyzed by 10% native PAGE and phosphorimaging. (B) SE reactions were carried out as in (A) except that aliquots of the reactions were removed at the indicated times and treated as above. (C) SE reactions were performed with Rad52 mutants. (D) SE assays were performed with sub-domains of WRN235–526.

The above correlation is supported by analysis of WRN proteins. As shown in Figure 3D, the complementing domain WRN235–526 tested positive in the apparent SE assay. Similar to Rad52N, the apparent SE activity of WRN235–526 peaked at a concentration of 0.8 µM after which exchange was inhibited. However, neither WRN301–526 nor WRN255–366 retained apparent SE activity (Fig. 3D), which correlates with the inability of these constructs to complement Sgs1-ΔSE function in vivo. Taken together, the ability to carry-out apparent SE activity in vitro correlates fully with in vivo complementation using chimeric Sgs1 fusion proteins.

3.4. Similarity of apparent DNA strand exchange by WRN235–526 and BLM95–294

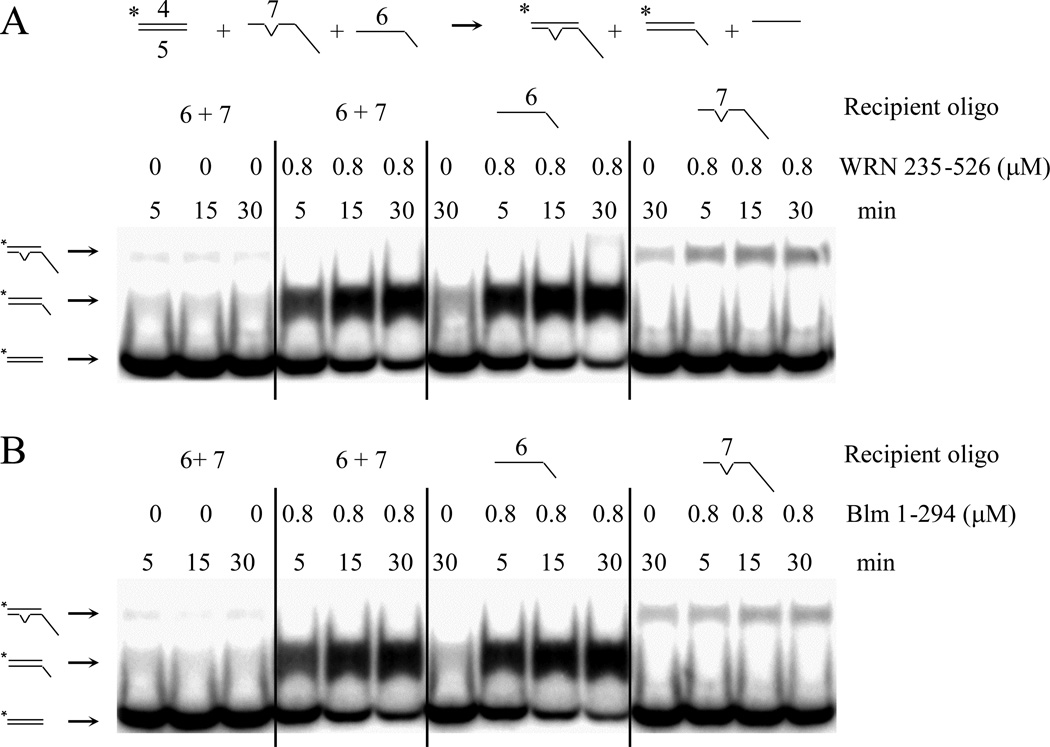

We compared the activities of WRN235–526 to those previously found in BLM95–294 by testing whether its apparent SE activity is sensitive to mismatches in homologous DNA substrates. Thus, we compared SE reactions in which the recipient oligos contained either perfect homology to the 32 bp duplex core sequence or contained a single mismatch at the center of this core. To distinguish the SE products, the oligos containing these core sequences differed in size. As shown in Figure 4A, WRN235–526 promoted the exchange of the labeled oligo from the donor duplex onto a 57 nt recipient oligo containing perfect homology, but it was unable to exchange the strand onto a 94 nt oligo containing one mismatch within its core sequence. Mismatch sensitivity was also observed in a competitive SE reaction in which the donor DNA was allowed to exchange onto either of these two oligos (Fig. 4A). Under these conditions, the labeled oligo exchanged exclusively onto the perfectly homologous recipient ssDNA. This mismatch sensitivity of the SE reaction is essentially identical to that obtained with BLM1–294 (Fig. 4B) providing additional evidence that the WRN235–526 and BLM95–300 domains are functionally equivalent.

Figure 4.

Similarity of apparent SE by WRN235–526 and BLM1–294. The indicated SE reactions were carried out using 1 nM of duplex donor DNA (#4*/#5) and 20 nM of either oligo #7 (94 nt, one mismatch) alone, oligo #6 (57 nt, no mismatch) alone, or both oligos as recipient. SE reactions were carried out as in the presence or absence of 800 nM WRN235–526 (A) or BLM1–294 (B) and stopped after the indicated incubation time. An inverted caret in the schematic indicates a single bp mismatch to the complementary oligo #7.

In verifying our interpretation of the apparent SE reaction, we considered the possibility that the donor DNA duplex was simply melted by WRN235–526 after which the labeled strand passively annealed to the recipient oligo during the protease step prior to electrophoresis. To test this possibility, we performed an experiment in which the reaction was terminated with a high concentration of a second complementary (trap) oligo in the stop buffer. This experiment failed to detect annealing of the labeled strand to the trap oligo (Fig. S4A) indicating that labeled ssDNA was not present following the assay or during protease treatment. Further, the WRN235–526 preparation did not contain detectable single- or double-strand DNA-specific exonuclease activity that might affect the interpretation of the above results (Fig. S4B).

3.5. Identification of a coiled-coil domain in Sgs1-SE

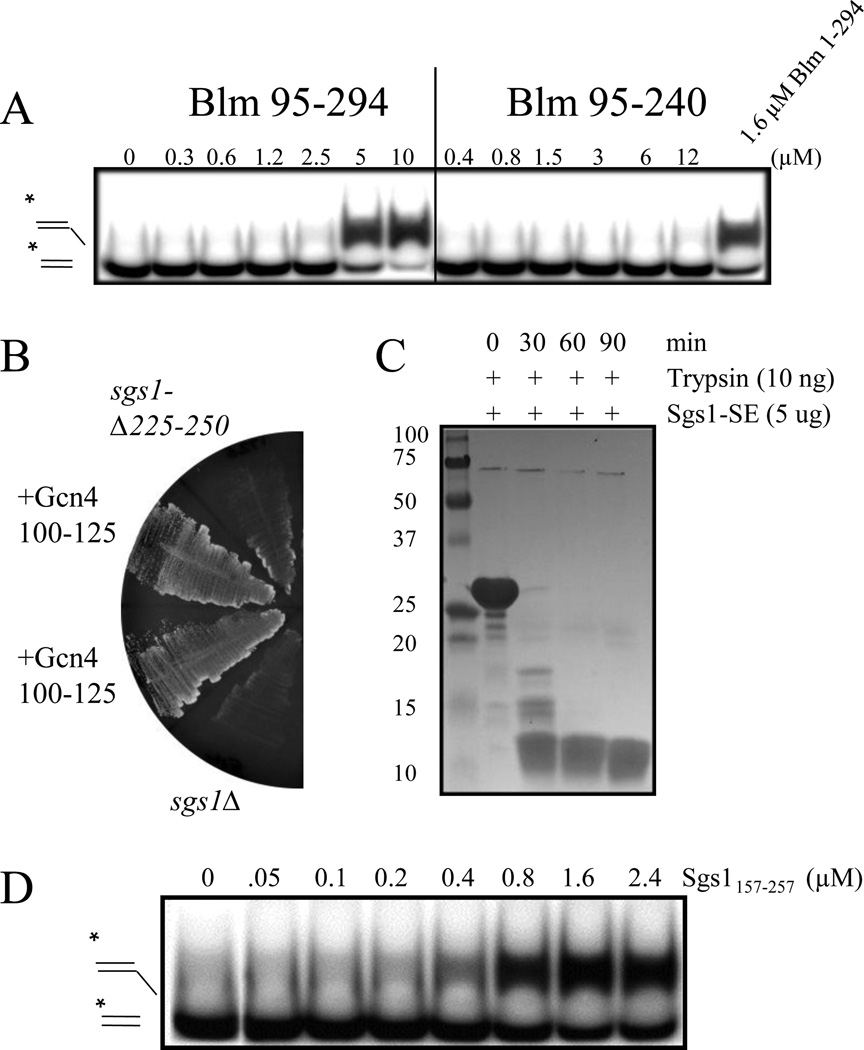

The coiled-coil domain of WRN247–299 was present in all constructs that both complemented Sgs1-ΔSE in vivo function and displayed apparent SE activity. The requirement for this element motivated us to search for similar domains in Sgs1 and BLM. Amino acid sequence analysis of the N-termini of Sgs1 and BLM by the COILS program [61] revealed predicted coiled-coil motifs (Sgs1225–250 and BLM245–295) (Fig. S5). Previous structure-function analysis of Sgs1-SE indicated that residues 225–250 were among those required for Sgs1-SE activity in vitro [48]. We therefore tested the requirement of the predicted coiled coil in BLM and found that BLM95–240, lacking the predicted coiled coil, no longer displayed apparent SE activity (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5.

A putative coiled-coil domain in Sgs1/BLM is required for in vivo function and in vitro SE activity. (A) SE assays were carried out as in Fig. 4A using the indicated concentrations of BLM95–294 and BLM95–240 which lacks the putative coiled coil. (B) Complementation of sgs1Δ was performed as in Fig. 1A using SGS1 alleles lacking the putative coiled coil (sgs1-Δ225–250) or containing the Gcn4 coiled coil (Gcn4100–125) in its place. (C) Sgs1102–322 was treated with trypsin and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining. (D) Sgs1157–257 was assayed for SE activity as above.

To test the in vivo requirement for a functional coiled-coil in Sgs1, we first constructed an allele of SGS1 (sgs1-Δ225–250) that specifically lacked this domain. This allele was unable to confer growth to sgs1Δ slx4Δ cells indicating that these 25 aa are essential for in vivo activity (Fig. 5B). We next inserted into this construct a heterologous coiled-coil from the well-studied Gcn4 protein [62] (Gcn4100–125) such that they replaced Sgs1225–250. This heterologous domain restored biological activity in a chimeric Sgs1-Gcn4 protein (Fig. 5B). Thus, we conclude that a functional coiled coil is required for wt Sgs1 activity.

To determine how closely associated the coiled coil of Sgs1-SE (Sgs1103–322) is to the in vitro activities we have observed, we attempted to define a smaller core domain within this fragment. To do this, we subjected Sgs1103–322 to limited proteolysis by trypsin. This resulted in a protease-resistant 12 kD product that most likely represents a stably folded core domain (Fig. 5C). Mass spectrometry of the digestion product identified it as Sgs1157–257 indicating that the core domain contains the predicted coiled coil. Interestingly, recombinant Sgs1157–257 displayed apparent SE activity (Fig. 5D). We conclude that apparent SE activity is inherent to this core domain and is closely associated with the coiled coil.

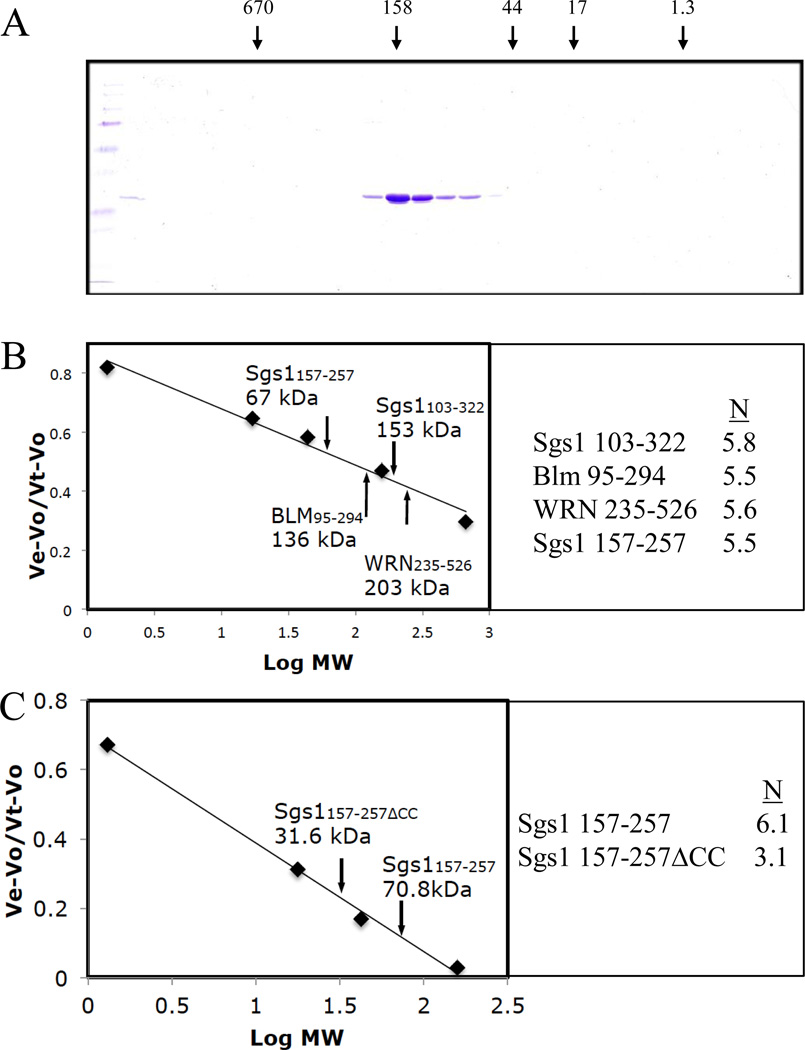

Given the presence of a coiled coil in Sgs1-SE, we tested whether this domain exists as an oligomer in solution. Size-exclusion chromatography of the 26 kDa Sgs1103–322 confirmed that the protein was multimeric as it migrated as a single peak with a native MWr of 153 kDa (Fig. 6A). We then subjected Sgs1157–257, BLM95–294, and WRN235–526 to gel-filtration chromatography and estimated the multimeric state of all four proteins from their native MWr. As shown in Figure 6B, the multimeric state of all four proteins was calculated to be in the range of 5.5 – 5.8 suggesting that all of these isolated domains exist as hexamers in solution.

Figure 6.

Size exclusion chromatography of N-terminal fragments of Sgs1, BLM, and WRN. (A) 50 µg Sgs1103–322 was subjected to Superose 6 chromatography and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining. MW standards are thyroglobulin (670 kDa), aldolase (158 kDa), ovalbumin (44 kDa), myoglobin (17 kDa), and vitamin B12 (1.4 kDa). (B) The four indicated proteins were analyzed by Superose 6 chromatography as above. The peak elution point for each protein is presented on the standard curve along with its native MW as determined chromatographically. On the right is the calculated oligomeric state (N) for each protein. (C) Sgs1157–257 and Sgs1157–257ΔCC lacking coiled-coil residues 225–250 were analyzed by Superdex 75 chromatography using IgG (158 kDa), ovalbumin, myoglobin and vitamin B12 as standards.

3.6. Conservation of SE activity in human RECQ4

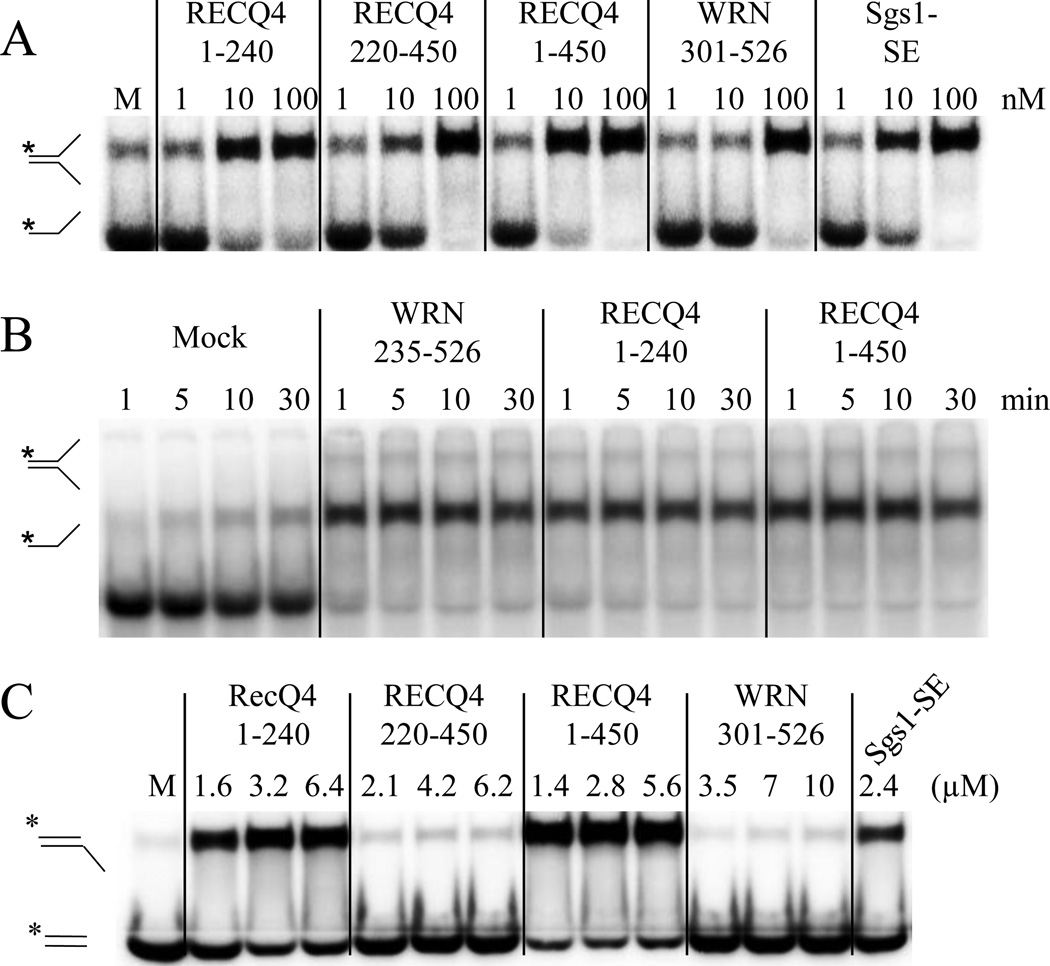

To test the possibility that these features are conserved in all three large human RecQ homologs, we examined the 450 aa N-terminal domain of RECQ4. In contrast to BLM and WRN, a coiled coil was predicted to form not in the middle of the N-terminal domain, but at the extreme N-terminus of the protein (RECQ4 residues 1 – 25), in a region that was previously noted for bearing homology to the yeast Sld2 protein (Fig. S6A and B). GST-fusion proteins were made to RECQ41–450, as well as the two halves of the N-terminus. Assays with these proteins indicated that the N-terminus contains at least two ssDNA binding domains (Fig. S6C). Like RECQ41–450, both RECQ41–240 and RECQ4220–450 bound ssDNA and displayed robust SA activity (Figs. 7A and B) with nearly identical properties to those found in Sgs1, BLM and WRN (Figs. S6D and E). However, whereas RECQ41–450 and RECQ41–240 displayed apparent SE activity, RECQ4220–450 did not (Fig. 7C). This result is in agreement with the earlier observation, that the presence of a multimerization domain is associated with apparent SE activity in vitro. Moreover, it confirms that these biochemical activities are conserved across multiple RecQ homologs. It is likely that the conserved SE activity observed here is related to the ATP-dependent DNA unwinding activity reported for the Sld2-like domain of RECQ4 [37]. Reminiscent of the SE reaction, DNA unwinding by the Sld2-like domain is dependent on an unlabeled oligonucleotide to trap the displaced strand [37].

Figure 7.

Strand annealing and apparent strand-exchange activities are conserved in the N-terminus of RECQ4. (A) The indicated N-terminal ssDNA binding domains of RECQ4 were purified as C-terminal His6-tagged proteins and assayed for SA activity as described in Fig. 1C. (B) Reactions were carried out as in (A) except that aliquots of the reactions were removed at the indicated times and treated as above. (C) The indicated His6-tagged proteins were assayed for apparent SE activity as described in Figure 3A.

4. Discussion

The eukaryotic RecQ DNA helicase family appears to have resulted from the elaboration of a conserved RecQ helicase core by the addition of divergent N- and C-terminal domains. We have used yeast Sgs1 as a model to interrogate the function of the N-terminus of BLM. Here, we set out to elucidate the function of Sgs1-SE (Sgs1103–322), a recently-identified domain conserved in BLM orthologs that is important in vivo and displays SA and apparent SE activity in vitro. Using heterologous domains in place of Sgs1-SE, we observed that in vivo function strictly correlated with the presence of both apparent SE activity and a closely-associated multimerization domain. This observation allowed us to identify a potential coiled-coil domain in BLM orthologs. This 25 aa region was required for Sgs1 activity in vivo and could be functionally replaced by a heterologous coiled-coil. Interestingly, a domain with nearly identical activities lies between the exonuclease and RecQ helicase domains of WRN, as well as in the N-terminus of RECQ4. The fact that the WRN domain contains a known coiled-coil and displays apparent SE activity in vitro, suggests that these two RecQ family members share more than a RecQ helicase core.

Although some members of the RecQ family are known to form multimers in solution, the mechanism of multimerization and its consequences are not well understood. Whereas bacterial RecQ protein is monomeric in solution [63], a variety of multimeric forms have been reported for WRN. WRN helicase has been reported to form a trimer in solution while electron microscopy (EM) indicates that it is dimeric and oligomerizes when bound to DNA substrates [64, 65]. Multimerization of WRN most likely requires the heptad-repeat coiled-coil domain in its N-terminus, which was previously shown to promote the trimerization of WRN1–333 [11]. Our finding that WRN235–526 is hexameric may be due to residues C-terminal to the coiled coil in our construct. For example, WRN235–526 may assemble into a dimer of trimers which is a possibility that has previously been suggested [11].

In the case of BLM, gel filtration and EM data indicate that the full-length protein forms tetramers and hexamers in solution [66]. Interestingly, the core RecQ helicase domain of BLM is a monomer in solution [67] suggesting that the N-terminus confers this multimerization function. Consistent with this interpretation, recombinant fragments of the BLM N-terminus form hexamers and dodecamers indicating that a multimerization domain is localized to the first 431 aa of BLM [68]. Thus, it is very likely that the potential coiled-coil domains defined by Sgs1225–250, and BLM245–295 play a role in the multimerization of full-length BLM orthologs. Future experiments will focus on testing this prediction and the role of multimerization within the context of the full-length proteins. Although the specific role of multimerization is unknown, genetic studies presented here clearly reveal an in vivo function for the Sgs1 coiled coil. It should be pointed out however, that the coiled coil cannot be required for all Sgs1 functions since internal deletions eliminating this domain do not generate null phenotypes such as sensitivity to DNA damaging agents [26]. On the other hand, structure-function studies suggest that it is required for complementation of top3Δ slow-growth suppression (Fig. S1) as well as for suppression of certain types of hyper-recombination and hetero-duplex rejection [48]. These non-trivial phenotypes indicate that the N-terminal domain of Sgs1 has an important function. An obvious remaining question is whether this function is relevant to Sgs1 DNA helicase activity.

Our experiments with SA proteins revealed that proteins that were active in vivo as chimeric Sgs1 fusions (Rad52N, BLM95–294, WRN235–526) both contained a multimerization domain and exhibited apparent SE activity in vitro. This suggests that apparent SE in vitro is dependent on multimerization. If so, one explanation for the inability of Rad52N–A90V to carry out apparent SE it that it is unable to multimerize. Although this has not been tested experimentally, yeast Rad52-A90 is conserved as human Rad52-A75 which maps within its self-association domain (hsRad5265–165) [69]. Further, based on its SA activity, Rad52N–A90V does not appear to have a defect in DNA binding. Thus, the simplest explanation for the in vitro results is that oligomerization of SA proteins endows them with the ability to carry out apparent SE.

We observed multiple cases in which a multimerization domain was required for in vivo complementation. For example, the WRN255–526 fragment, containing nearly all of the coiled coil, provides robust growth as an Sgs1-fusion whereas WRN301–526, lacking all of the coiled coil does not. Although the coiled coil is necessary, it is not sufficient for wt complementation. In contrast to WRN255–526, structure-function analysis indicated that WRN255–366, containing just the coiled coil, displayed slow growth (Figs. 3 and S3). These results indicate that residues C-terminal to the coiled coil are important although their function is not known. It is expected that these residues contact ssDNA to promote SA. Their close association with a multimerization domain might be required to amplify the affinity of adjacent weak ssDNA binding domains, enhance dsDNA melting, or allow ssDNA and dsDNA substrates to be tethered so that apparent SE can be propelled by their SA activity. Alternatively, the multimerization of DNA binding domains may be required to search for homology between different DNA sequences. Such a mechanism would be consistent with the behavior of RecQ1 in which higher-order oligomers are associated with a SA activity that is not observed in dimers [39].

Still to be determined is the biological role of the conserved SE activity. At present, we only know that the coiled-coil domain is important for biological activity. Additional experiments are needed to map and eliminate the residues required for ssDNA binding so that these alleles can be assayed for in vivo function. Until this is accomplished, we cannot rule out the possibility that exchange of DNA fragments is a non-specific feature of ssDNA binding proteins, such as RPA, that have the ability to both unwind dsDNA and anneal ssDNA [70]. However, the presence of SE activity in the very different sequences of Sgs1, BLM, and WRN suggests that this conservation is more than coincidence and that SE activity is important for RecQ DNA helicase function within the context of the full-length proteins.

An alternative possibility is that the biologically important activity of the SE domain is its SA activity. Authentic SA activities, such as by yeast Rad52, are resistant to inhibition by RPA [71]. Although we found that the SA activity of the isolated SE domain is inhibited by RPA, it is possible that adjacent RPA-interacting domains might act within the context of the full-length protein to relieve this inhibition. Interestingly, protein interaction studies have mapped RPA interaction domains within BLM1–447 and WRN239–499 [44]. Further, it is known that RPA interacts positively with BLM and WRN as they unwind DNA or branch migrate HJs [41, 72]. How then might the SE domain cooperate with the RecQ helicase? An intriguing possibility is that the SE domain assists the helicase in branch migrating HJs, separating and annealing homologous strands. Some support for such an idea is suggested by single-molecule studies of the BLM-RPA interaction [73]. These studies indicate that BLM repetitively unwinds short stretches of a forked substrate after which the strands reanneal even in the presence of RPA. In a later step, BLM undergoes a strand switch and binds ssDNA in the presence of RPA. This reaction specifically requires the N-terminal domain of BLM [73] and may explain the need for ssDNA binding and SA activities in the N-termini of BLM and WRN.

In conclusion, the N-terminus of Sgs1 contains a coiled-coil multimerization domain that is required for biological function in the absence of the Slx4 nuclease scaffold. A similar coiled-coil domain is conserved in WRN, and appears to be conserved in BLM and RECQ4. The fact that all four of these domains are associated with ssDNA binding and strand-annealing activities suggests they serve a common biological function that has yet to be identified. Moreover, the SE activity displayed by each of these proteins suggests a general mechanism by which oligomerized ssDNA binding domains are sufficient to carry-out ATP-independent strand exchange in vitro.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

The yeast RecQ DNA helicase Sgs1 contains a coiled-coil in its N-terminal domain.

Multimerization is required for Sgs1 function in the absence of SLX4.

The coiled coil is required for ATP-independent DNA strand-exchange in vitro.

The N-terminal domains of BLM, WRN and RECQ4 display identical in vitro activities.

Acknowledgments

We thank Haiyan Zheng for mass spectrometry, Anupama Sureschandra for technical assistance, and Patrick Sung and Robert Brosh for plasmids. We also thank Jan Mullen and Sam Bunting for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH grants R01 GM071268 and R01 GM101613, and by a grant from the Busch Biomedical Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ouyang KJ, Woo LL, Ellis NA. Homologous recombination and maintenance of genome integrity: cancer and aging through the prism of human RecQ helicases. Mech Ageing Dev. 2008;129:425–440. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rossi ML, Ghosh AK, Bohr VA. Roles of Werner syndrome protein in protection of genome integrity. DNA Repair (Amst) 2010;9:331–344. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Epstein CJ, Martin GM, Schultz AL, Motulsky AG. Werner's syndrome a review of its symptomatology, natural history, pathologic features, genetics and relationship to the natural aging process. Medicine. 1966;45:177–221. doi: 10.1097/00005792-196605000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goto M, Miller RW, Ishikawa Y, Sugano H. Excess of rare cancers in Werner syndrome (adult progeria) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1996;5:239–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoehn H, Bryant EM, Au K, Norwood TH, Boman H, Martin GM. Variegated translocation mosaicism in human skin fibroblast cultures. Cytogenet. Cell Genet. 1975;15:282–298. doi: 10.1159/000130526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moser MJ, Holley WR, Chatterjee A, Mian IS. The proofreading domain of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I and other DNA and/or RNA exonuclease domains. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:5110–5118. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.5110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mushegian AR, Bassett DE, Jr, Boguski MS, Bork P, Koonin EV. Positionally cloned human disease genes: patterns of evolutionary conservation and functional motifs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:5831–5836. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shen JC, Gray MD, Oshima J, Kamath-Loeb AS, Fry M, Loeb LA. Werner syndrome protein. I. DNA helicase and DNA exonuclease reside on the same polypeptide. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:34139–34144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.51.34139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamath-Loeb AS, Shen JC, Loeb LA, Fry M. Werner syndrome protein. II. Characterization of the integral 3' --> 5' DNA exonuclease. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:34145–34150. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.51.34145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang S, Li B, Gray MD, Oshima J, Mian IS, Campisi J. The premature ageing syndrome protein, WRN, is a 3'-->5' exonuclease. Nat. Genet. 1998;20:114–116. doi: 10.1038/2410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perry JJ, Asaithamby A, Barnebey A, Kiamanesch F, Chen DJ, Han S, Tainer JA, Yannone SM. Identification of a coiled-coil in WRN that facilitates multimerization and promotes exonuclease processivity. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:25699–25707. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.124941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bloom D. Congenital telangiectatic erythema resembling lupus erythematosus in dwarfs. Am. J. Dis. Child. 1954;88:754–758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.German J. Bloom Syndrome: A mendelian prototype of somatic mutational disease. Medicine. 1993;72:393–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.German J. Cytological evidence for crossing-over in vitro in human lymphoid cells. Science. 1964;144:298–301. doi: 10.1126/science.144.3616.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vijayalaxmi , Evans HJ, Ray JH, German J. Bloom's syndrome: evidence for an increased mutation frequency in vivo. Science. 1983;221:851–853. doi: 10.1126/science.6879180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu D, Guo R, Sobeck A, Bachrati CZ, Yang J, Enomoto T, Brown GW, Hoatlin ME, Hickson ID, Wang W. RMI, a new OB-fold complex essential for Bloom syndrome protein to maintain genome stability. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2843–2855. doi: 10.1101/gad.1708608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh TR, Ali AM, Busygina V, Raynard S, Fan Q, Du CH, Andreassen PR, Sung P, Meetei AR. BLAP18/RMI2, a novel OB-fold-containing protein, is an essential component of the Bloom helicase-double Holliday junction dissolvasome. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2856–2868. doi: 10.1101/gad.1725108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu L, Bachrati CZ, Ou J, Xu C, Yin J, Chang M, Wang W, Li L, Brown GW, Hickson ID. BLAP75/RMI1 promotes the BLM-dependent dissolution of homologous recombination intermediates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:4068–4073. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508295103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen CF, Brill SJ. Binding and activation of DNA topoisomerase III by the Rmi1 subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:28971–28979. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705427200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang M, Bellaoui M, Zhang C, Desai R, Morozov P, Delgado-Cruzata L, Rothstein R, Freyer GA, Boone C, Brown GW. RMI1/NCE4, a suppressor of genome instability, encodes a member of the RecQ helicase/Topo III complex. EMBO J. 2005;24:2024–2033. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bennett RJ, Noirot-Gros MF, Wang JC. Interaction between yeast Sgs1 helicase and DNA topoisomerase III. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:26898–26905. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003137200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fricke WM, Kaliraman V, Brill SJ. Mapping the DNA topoisomerase III binding domain of the Sgs1 DNA helicase. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:8848–8855. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009719200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu L, Davies SL, North PS, Goulaouic H, Riou JF, Turley H, Gatter KC, Hickson ID. The Bloom's syndrome gene product interacts with topoisomerase III. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:9636–9644. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gangloff S, McDonald JP, Bendixen C, Arthur L, Rothstein R. The yeast type I topoisomerase Top3 interacts with Sgs1, a DNA helicase homolog: a potential eukaryotic reverse gyrase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994;14:8391–8398. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.12.8391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mullen JR, Nallaseth FS, Lan YQ, Slagle CE, Brill SJ. Yeast Rmi1/Nce4 controls genome stability as a subunit of the Sgs1-Top3 complex. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;25:4476–4487. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.11.4476-4487.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ui A, Satoh Y, Onoda F, Miyajima A, Seki M, Enomoto T. The N-terminal region of Sgs1, which interacts with Top3, is required for complementation of MMS sensitivity and suppression of hyper-recombination in sgs1 disruptants. Mol Genet Genomics. 2001;265:837–850. doi: 10.1007/s004380100479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raynard S, Bussen W, Sung P. A double Holliday junction dissolvasome comprising BLM, topoisomerase IIIalpha, and BLAP75. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:13861–13864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600051200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu L, Hickson ID. The Bloom's syndrome helicase suppresses crossing over during homologous recombination. Nature. 2003;426:870–874. doi: 10.1038/nature02253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ira G, Malkova A, Liberi G, Foiani M, Haber JE. Srs2 and Sgs1-Top3 suppress crossovers during double-strand break repair in yeast. Cell. 2003;115:401–411. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00886-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adams MD, McVey M, Sekelsky JJ. Drosophila BLM in double-strand break repair by synthesis-dependent strand annealing. Science. 2003;299:265–267. doi: 10.1126/science.1077198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nimonkar AV, Ozsoy AZ, Genschel J, Modrich P, Kowalczykowski SC. Human exonuclease 1 and BLM helicase interact to resect DNA and initiate DNA repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:16906–16911. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809380105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhu Z, Chung WH, Shim EY, Lee SE, Ira G. Sgs1 helicase and two nucleases Dna2 and Exo1 resect DNA double-strand break ends. Cell. 2008;134:981–994. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mimitou EP, Symington LS. Sae2, Exo1 and Sgs1 collaborate in DNA double-strand break processing. Nature. 2008;455:770–774. doi: 10.1038/nature07312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharma S, Sommers JA, Choudhary S, Faulkner JK, Cui S, Andreoli L, Muzzolini L, Vindigni A, Brosh RM., Jr Biochemical analysis of the DNA unwinding and strand annealing activities catalyzed by human RECQ1. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:28072–28084. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500264200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Machwe A, Xiao L, Groden J, Matson SW, Orren DK. RecQ family members combine strand pairing and unwinding activities to catalyze strand exchange. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:23397–23407. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414130200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garcia PL, Liu Y, Jiricny J, West SC, Janscak P. Human RECQ5beta, a protein with DNA helicase and strand-annealing activities in a single polypeptide. EMBO J. 2004;23:2882–2891. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu X, Liu Y. Dual DNA unwinding activities of the Rothmund-Thomson syndrome protein, RECQ4. EMBO J. 2009;28:568–577. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cheok CF, Wu L, Garcia PL, Janscak P, Hickson ID. The Bloom's syndrome helicase promotes the annealing of complementary single-stranded DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:3932–3941. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muzzolini L, Beuron F, Patwardhan A, Popuri V, Cui S, Niccolini B, Rappas M, Freemont PS, Vindigni A. Different quaternary structures of human RECQ1 are associated with its dual enzymatic activity. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e20. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Machwe A, Lozada EM, Xiao L, Orren DK. Competition between the DNA unwinding and strand pairing activities of the Werner and Bloom syndrome proteins. BMC Mol Biol. 2006;7:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-7-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brosh RM, Jr, Li JL, Kenny MK, Karow JK, Cooper MP, Kureekattil RP, Hickson ID, Bohr VA. Replication protein A physically interacts with the Bloom's syndrome protein and stimulates its helicase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:23500–23508. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001557200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brosh RM, Jr, Orren DK, Nehlin JO, Ravn PH, Kenny MK, Machwe A, Bohr VA. Functional and physical interaction between WRN helicase and human replication protein A. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:18341–18350. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shen JC, Lao Y, Kamath-Loeb A, Wold MS, Loeb LA. The N-terminal domain of the large subunit of human replication protein A binds to Werner syndrome protein and stimulates helicase activity. Mech Ageing Dev. 2003;124:921–930. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(03)00164-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Doherty KM, Sommers JA, Gray MD, Lee JW, von Kobbe C, Thoma NH, Kureekattil RP, Kenny MK, Brosh RM., Jr Physical and functional mapping of the replication protein a interaction domain of the werner and bloom syndrome helicases. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:29494–29505. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500653200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mullen JR, Kaliraman V, Brill SJ. Bipartite structure of the SGS1 DNA helicase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Genetics. 2000;154:1101–1114. doi: 10.1093/genetics/154.3.1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bernstein KA, Shor E, Sunjevaric I, Fumasoni M, Burgess RC, Foiani M, Branzei D, Rothstein R. Sgs1 function in the repair of DNA replication intermediates is separable from its role in homologous recombinational repair. EMBO J. 2009;28:915–925. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rockmill B, Fung JC, Branda SS, Roeder GS. The Sgs1 helicase regulates chromosome synapsis and meiotic crossing over. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1954–1962. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.10.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen CF, Brill SJ. An essential DNA strand exchange activity is conserved in the divergent N-termini of BLM orthologs. EMBO J. 2010;29:1713–1725. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sikorski RS, Hieter P. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Genetics. 1989;12:19–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Adams A, Gottschling DE, Kaiser CA, Stearns T. Methods in Yeast Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mullen JR, Kaliraman V, Ibrahim SS, Brill SJ. Requirement for three novel protein complexes in the absence of the Sgs1 DNA helicase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Genetics. 2001;157:103–118. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mortensen UH, Bendixen C, Sunjevaric I, Rothstein R. DNA strand annealing is promoted by the yeast Rad52 protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:10729–10734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.10729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sugiyama T, Kantake N, Wu Y, Kowalczykowski SC. Rad52-mediated DNA annealing after Rad51-mediated DNA strand exchange promotes second ssDNA capture. EMBO J. 2006;25:5539–5548. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shinohara A, Ogawa T. Stimulation by Rad52 of yeast Rad51-mediated recombination. Nature. 1998;391:404–407. doi: 10.1038/34943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kagawa W, Kurumizaka H, Ikawa S, Yokoyama S, Shibata T. Homologous pairing promoted by the human Rad52 protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:35201–35208. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104938200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bai Y, Symington LS. A Rad52 homolog is required for RAD51-independent mitotic recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2025–2037. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.16.2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Petukhova G, Stratton SA, Sung P. Single strand DNA binding and annealing activities in the yeast recombination factor Rad59. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:33839–33842. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.48.33839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Park MS, Ludwig DL, Stigger E, Lee SH. Physical interaction between human RAD52 and RPA is required for homologous recombination in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:18996–19000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.31.18996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ranatunga W, Jackson D, Lloyd JA, Forget AL, Knight KL, Borgstahl GE. Human RAD52 exhibits two modes of self-association. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:15876–15880. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011747200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bi B, Rybalchenko N, Golub EI, Radding CM. Human and yeast Rad52 proteins promote DNA strand exchange. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:9568–9572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403205101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lupas A, Van Dyke M, Stock J. Predicting coiled coils from protein sequences. Science. 1991;252:1162–1164. doi: 10.1126/science.252.5009.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.O'Shea EK, Klemm JD, Kim PS, Alber T. X-ray structure of the GCN4 leucine zipper, a two-stranded, parallel coiled coil. Science. 1991;254:539–544. doi: 10.1126/science.1948029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Harmon FG, Kowalczykowski SC. Biochemical characterization of the DNA helicase activity of the escherichia coli RecQ helicase. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:232–243. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006555200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Huang S, Beresten S, Li B, Oshima J, Ellis NA, Campisi J. Characterization of the human and mouse WRN3'-->5' exonuclease. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:2396–2405. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.12.2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Compton SA, Tolun G, Kamath-Loeb AS, Loeb LA, Griffith JD. The Werner syndrome protein binds replication fork and holliday junction DNAs as an oligomer. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:24478–24483. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803370200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Karow JK, Chakraverty RK, Hickson ID. The Bloom's syndrome gene product is a 3'–5' DNA helicase. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:30611–30614. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.49.30611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Janscak P, Garcia PL, Hamburger F, Makuta Y, Shiraishi K, Imai Y, Ikeda H, Bickle TA. Characterization and mutational analysis of the RecQ core of the bloom syndrome protein. J Mol. Biol. 2003;330:29–42. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00534-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Beresten SF, Stan R, van Brabant AJ, Ye T, Naureckiene S, Ellis NA. Purification of overexpressed hexahistidine-tagged BLM N431 as oligomeric complexes. Protein expression and purification. 1999;17:239–248. doi: 10.1006/prep.1999.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shen Z, Peterson SR, Comeaux JC, Zastrow D, Moyzis RK, Bradbury EM, Chen DJ. Self-association of human RAD52 protein. Mutat Res. 1996;364:81–89. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(96)00025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Georgaki A, Hubscher U. DNA unwinding by replication protein A is a property of the 70 kDa subunit and is facilitated by phosphorylation of the 32 kDa subunit. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:3659–3665. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.16.3659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wu Y, Sugiyama T, Kowalczykowski SC. DNA annealing mediated by Rad52 and Rad59 proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:15441–15449. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601827200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sowd G, Wang H, Pretto D, Chazin WJ, Opresko PL. Replication protein A stimulates the Werner syndrome protein branch migration activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:34682–34691. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.049031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yodh JG, Stevens BC, Kanagaraj R, Janscak P, Ha T. BLM helicase measures DNA unwound before switching strands and hRPA promotes unwinding reinitiation. EMBO J. 2009;28:405–416. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.